the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Influence of temperature on the molecular composition of ions and charged clusters during pure biogenic nucleation

Carla Frege

Ismael K. Ortega

Matti P. Rissanen

Arnaud P. Praplan

Gerhard Steiner

Martin Heinritzi

Lauri Ahonen

António Amorim

Anne-Kathrin Bernhammer

Federico Bianchi

Sophia Brilke

Martin Breitenlechner

Lubna Dada

António Dias

Jonathan Duplissy

Sebastian Ehrhart

Imad El-Haddad

Lukas Fischer

Claudia Fuchs

Olga Garmash

Marc Gonin

Armin Hansel

Christopher R. Hoyle

Tuija Jokinen

Heikki Junninen

Jasper Kirkby

Andreas Kürten

Katrianne Lehtipalo

Markus Leiminger

Roy Lee Mauldin

Ugo Molteni

Leonid Nichman

Tuukka Petäjä

Nina Sarnela

Siegfried Schobesberger

Mario Simon

Mikko Sipilä

Dominik Stolzenburg

António Tomé

Alexander L. Vogel

Andrea C. Wagner

Robert Wagner

Mao Xiao

Penglin Ye

Joachim Curtius

Neil M. Donahue

Richard C. Flagan

Markku Kulmala

Douglas R. Worsnop

Paul M. Winkler

Urs Baltensperger

It was recently shown by the CERN CLOUD experiment that biogenic highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs) form particles under atmospheric conditions in the absence of sulfuric acid, where ions enhance the nucleation rate by 1–2 orders of magnitude. The biogenic HOMs were produced from ozonolysis of α-pinene at 5 ∘C. Here we extend this study to compare the molecular composition of positive and negative HOM clusters measured with atmospheric pressure interface time-of-flight mass spectrometers (APi-TOFs), at three different temperatures (25, 5 and −25 ∘C). Most negative HOM clusters include a nitrate (NO) ion, and the spectra are similar to those seen in the nighttime boreal forest. On the other hand, most positive HOM clusters include an ammonium (NH) ion, and the spectra are characterized by mass bands that differ in their molecular weight by ∼ 20 C atoms, corresponding to HOM dimers. At lower temperatures the average oxygen to carbon (O : C) ratio of the HOM clusters decreases for both polarities, reflecting an overall reduction of HOM formation with decreasing temperature. This indicates a decrease in the rate of autoxidation with temperature due to a rather high activation energy as has previously been determined by quantum chemical calculations. Furthermore, at the lowest temperature (−25 ∘C), the presence of C30 clusters shows that HOM monomers start to contribute to the nucleation of positive clusters. These experimental findings are supported by quantum chemical calculations of the binding energies of representative neutral and charged clusters.

- Article

(2527 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Atmospheric aerosol particles directly affect climate by influencing the transfer of radiant energy through the atmosphere (Boucher et al., 2013). In addition, aerosol particles can indirectly affect climate, by serving as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and ice nuclei (IN). They are of natural or anthropogenic origin, and result from direct emissions (primary particles) or from oxidation of gaseous precursors (secondary particles). Understanding particle formation processes in the atmosphere is important since more than half of the atmospheric aerosol particles may originate from nucleation (Dunne et al., 2016; Merikanto et al., 2009).

Due to its widespread presence and low saturation vapor pressure, sulfuric acid is believed to be the main vapor responsible for new particle formation (NPF) in the atmosphere. Indeed, particle nucleation is dependent on its concentration, albeit with large variability (Kulmala et al., 2004). The combination of sulfuric acid with ammonia and amines increases nucleation rates due to a higher stability of the initial clusters (Almeida et al., 2013; Kirkby et al., 2011; Kürten et al., 2016). However, these clusters alone cannot explain the particle formation rates observed in the atmosphere. Nucleation rates are greatly enhanced when oxidized organics are present together with sulfuric acid, resulting in NPF rates that closely match those observed in the atmosphere (Metzger et al., 2010; Riccobono et al., 2014). An important characteristic of the organic molecules participating in nucleation is their high oxygen content and consequently low vapor pressure. The formation of these highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs) has been described by Ehn et al. (2014), who found that, following the well-known initial steps of α-pinene ozonolysis through a Criegee intermediate leading to the formation of an RO2⋅ radical, several repeated cycles of intramolecular hydrogen abstractions and O2 additions produce progressively more oxygenated RO2 radicals, a mechanism called autoxidation (Crounse et al., 2013). The (extremely) low volatility of the HOMs results in efficient NPF and growth, even in the absence of sulfuric acid (Kirkby et al., 2016; Tröstl et al., 2016). The chemical composition of HOMs during NPF has been identified from α-pinene and pinanediol oxidation by Praplan et al. (2015) and Schobesberger et al. (2013), respectively.

Charge has also been shown to enhance nucleation (Kirkby et al., 2011). Ions are produced in the atmosphere mainly by galactic cosmic rays and radon. The primary ions are N+, N, O+, O, H3O+, O− and O (Shuman et al., 2015). These generally form clusters with water (e.g., (H2O)H3O+); after further collisions the positive and negative charges are transferred to trace species with highest and lowest proton affinities, respectively (Ehn et al., 2010). Ions are expected to promote NPF by increasing the cluster binding energy and reducing evaporation rates (Hirsikko et al., 2011). Recent laboratory experiments showed that ions increase the nucleation rates of HOMs from the oxidation of α-pinene by 1–2 orders of magnitude compared to neutral conditions (Kirkby et al., 2016). This is due to two effects, of which the first is more important: (1) an increase in cluster binding energy, which decreases evaporation, and (2) an enhanced collision probability, which increases the condensation of polar vapors on the charged clusters (Lehtipalo et al., 2016; Nadykto, 2003).

Temperature plays an important role in nucleation, resulting in strong variations of NPF at different altitudes. Kürten et al. (2016) studied the effect of temperature on nucleation for the sulfuric-acid–ammonia system, finding that low temperatures decrease the needed concentration of H2SO4 to maintain a certain nucleation rate. Similar results have been found for sulfuric-acid–water binary nucleation (Duplissy et al., 2016; Merikanto et al., 2016), where temperatures below 0 ∘C were needed for NPF to occur at atmospheric concentrations. Up to now, no studies have addressed the temperature effect on NPF driven by HOMs from biogenic precursors such as α-pinene.

In this study we focus on the chemical characterization of the ions and the influence of temperature on their chemical composition during organic nucleation in the absence of sulfuric acid. The importance of such sulfuric-acid-free clusters for NPF has been shown in the laboratory (Kirkby et al., 2016; Tröstl et al., 2016) as well as in the field (Bianchi et al., 2016). We present measurements of the NPF process from the detection of primary ions (e.g., N, O, NO+) to the formation of clusters in the size range of small particles, all under atmospherically relevant conditions. The experiments were conducted at three different temperatures (−25, 5 and 25 ∘C) enabling the simulation of pure biogenic NPF representative of different tropospheric conditions. This spans the temperature range where NPF might occur in tropical or sub-tropical latitudes (25 ∘C), high-latitude boreal regions (5 ∘C) and the free troposphere (−25 ∘C). For example, NPF events were reported to occur in an Australian Eucalypt forest (Suni et al., 2008) and at the boreal station in Hyytiälä (Kulmala et al., 2013). Nucleation by organic vapors was also observed at a high mountain station (Bianchi et al, 2016). High aerosol particle concentrations were measured in the upper troposphere over the Amazon Basin and tentatively attributed to the oxidation of biogenic volatile organic compounds (Andreae et al., 2017).

2.1 The CLOUD chamber

We conducted experiments at the CERN CLOUD chamber (Cosmics Leaving Outdoor Droplets). With a volume of 26.1 m3, the chamber is built of electropolished stainless steel and equipped with a precisely controlled gas system. The temperature inside the chamber is measured with a string of six thermocouples (TC, type K), which were mounted horizontally between the chamber wall and the center of the chamber at distances of 100, 170, 270, 400, 650 and 950 mm from the chamber wall (Hoyle et al., 2016). The temperature is controlled accurately (with a precision of ±0.1 ∘C) at any tropospheric temperature between −65 and 30 ∘C (in addition, the temperature can be raised to 100 ∘C for cleaning). The chamber enables atmospheric simulations under highly stable experimental conditions with low particle wall loss and low contamination levels (more details of the CLOUD chamber can be found in Kirkby et al., 2011 and Duplissy et al., 2016). At the beginning of the campaign the CLOUD chamber was cleaned by rinsing the walls with ultra-pure water, followed by heating to 100 ∘C and flushing at a high rate with humidified synthetic air and elevated ozone (several ppmv) (Kirkby et al., 2016). This resulted in SO2 and H2SO4 concentrations that were below the detection limit (< 15 pptv and < 5 × 104 cm−3, respectively), and total organics (largely comprising high volatility C1–C3 compounds) that were below 150 pptv.

The air in the chamber is ionized by galactic cosmic rays (GCRs); higher ion generation rates can be induced by a pion beam (π+) from the CERN Proton Synchrotron enabling controlled simulation of galactic cosmic rays throughout the troposphere. Therefore, the total ion-pair production rate in the chamber is between 2 (no beam) and 100 cm−3 s−1 (maximum available beam intensity, Franchin et al., 2015).

2.2 Instrumentation

The main instruments employed for this study were atmospheric pressure interface time-of-flight (APi-TOF, Aerodyne Research Inc. & Tofwerk AG) mass spectrometers. The instrument has two main parts. The first is the atmospheric pressure interface (APi), where ions are transferred from atmospheric pressure to low pressures via three differentially pumped vacuum stages. Ions are focused and guided by two quadrupoles and ion lenses. The second is the time-of-flight mass analyzer (TOF), where the pressure is approximately 10−6 mbar. The sample flow from the chamber was 10 L min−1, and the core-sampled flow into the APi was 0.8 L min−1, with the remaining flow being discarded.

There is no direct chemical ionization in front of the instrument. The APi-TOF measures the positive or negative ions and cluster ions as they are present in the ambient atmosphere. As described above, in the CLOUD chamber ions are formed by GCRs or deliberately by the π+ beam, leading to ion concentrations of a few hundred to thousands per cm3, respectively. In our chamber the dominant ionizing species are NH and NO (see below). These ions mainly form clusters with the organic molecules, which is driven by the cluster energies. Therefore, the signals obtained do not provide a quantitative measure of the concentrations of the compounds. The higher the cluster energy with certain compounds, the higher the ion cluster concentration will be.

We calibrated the APi-TOF using trioctylammonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (MTOA-B3FI, C27H54F6N2O4S2) to facilitate exact ion mass determination in both positive and negative ion modes. We employed two calibration methods, the first one by nebulizing MTOA-B3FI and separating cluster ions with a high-resolution ultra-fine differential mobility analyzer (UDMA) (see Steiner et al., 2014 for more information); the second one by using electrospray ionization of a MTOA-B3FI solution. The calibration with the electrospray ionization was performed three times, one for each temperature. These calibrations enabled mass/charge (m∕z) measurements with high accuracy up to 1500 Th in the positive ion mode and 900 Th in the negative ion mode.

Additionally, two peaks in the positive ion mode were identified as contaminants and also used for calibration purposes at the three different temperatures: C10H14OH+ and C20H28O2H+. These peaks were present before the addition of ozone in the chamber (therefore being most likely not products of α-pinene ozonolysis) and were also detected by a proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTR-TOF-MS). Both peaks appeared at the same m∕z at all three temperatures. Therefore, based on the calibrations with the UDMA, the electrospray and the two organic calibration peaks, we expect an accurate mass calibration at the three temperatures.

2.3 Experimental conditions

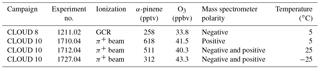

All ambient ion composition data reported here were obtained during nucleation experiments from pure α-pinene ozonolysis. The experiments were conducted under dark conditions, at a relative humidity (RH) of 38 % with an O3 mixing ratio between 33 and 43 ppbv (Table 1). The APi-TOF measurements were made under both galactic cosmic ray (GCR) and π+ beam conditions, with ion-pair concentrations around 700 and 4000 cm−3, respectively.

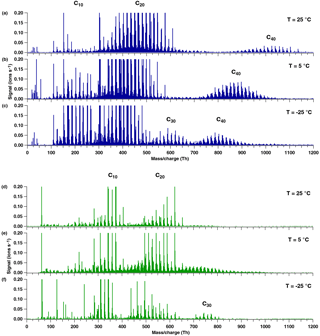

Figure 1Positive spectra at 5 ∘C. (a) Low mass region, where primary ions from galactic cosmic rays are observed, as well as secondary ions such as NH, which are formed by charge transfer to contaminants. (b) Higher mass region during pure biogenic nucleation, which shows broad bands in steps of C20. Most of the peaks represent clusters with NH.

2.4 Quantum chemical calculations

Quantum chemical calculations were performed on the cluster ion formation from the oxidation products of α-pinene. The Gibbs free energies of formation of representative HOM clusters were calculated using the MO62X functional (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008), and the 6-31+G(d) basis set (Ditchfield, 1971) using the Gaussian09 program (Frisch et al., 2009). This method has been previously applied for clusters containing large organic molecules (Kirkby et al., 2016).

3.1 Ion composition

Under dry conditions (RH = 0 %) and GCR ionization, the main detected positive ions were N2H+ and O. With increasing RH up to ∼ 30 % we observed the water clusters H3O+, (H2O) ⋅ H3O+ and (H2O)2 ⋅ H3O+ as well as NH, C5H5NH+ (protonated pyridine), Na+ and K+ (Fig. 1a). The concentrations of the precursors of some of the latter ions are expected to be very low; for example, NH3 mixing ratios were previously found to be in the range of 0.3 pptv (at −25 ∘C), 2 pptv (at 5 ∘C) and 4.3 pptv (at 25 ∘C) (Kürten et al., 2016). However, in a freshly cleaned chamber we expect ammonia levels below 1 pptv even at the higher temperatures. For the negative ions, NO was the main detected background signal. Before adding any trace gas to the chamber the signal of HSO was at a level of 1 % of the NO signal (corresponding to < 5 × 10−4 molecules cm−3, Kirkby et al., 2016), excluding any contribution of sulfuric acid to nucleation in our experiments.

After initiating α-pinene ozonolysis, more than 460 different peaks from organic ions were identified in the positive spectrum. The majority of peaks were clustered with NH, while only 10.2 % of the identified peaks were composed of protonated organic molecules. In both cases the organic core was of the type C7−10H10−16O1−10 for the monomer region and C17−20H24−32O5−19 for the dimer region.

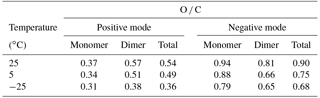

In the negative spectrum we identified more than 530 HOMs, of which ∼ 62 % corresponded to organic clusters with NO or, to a lesser degree, HNO3 ⋅ NO. The rest of the peaks were negatively charged organic molecules. In general, the organic core of the molecules was of the type C7−10H9−16O3−12 in the monomer region and C17−20H19−32O10−20 in the dimer region. For brevity we refer to the monomer, dimer (and n-mer) as C10, C20 (and C10n), respectively. Here, the subscript indicates the maximum number of carbon atoms in these molecules, even though the bands include species with slightly fewer carbon atoms.

Figure 2Comparison of the negative ion composition during α-pinene ozonolysis in CLOUD and during nighttime in the boreal forest at Hyytiälä (Finland). (a) CLOUD spectrum on a logarithmic scale. (b) CLOUD spectrum on a linear scale. (c) Typical nighttime spectrum from the boreal forest at Hyytiälä (Finland), adapted from Ehn et al. (2010).

3.1.1 Positive spectrum

The positive spectrum is characterized by bands of high intensity at C20 intervals, as shown in Fig. 1b. Although we detected the monomer band (C10), its integrated intensity was much lower than the C20 band; furthermore, the trimer and pentamer bands were almost completely absent. Based on chemical ionization mass spectrometry measurements, Kirkby et al. (2016) calculated that the HOM molar yield at 5 ∘C was 3.2 % for the ozonolysis of α-pinene, with a fractional yield of 10 to 20 % for dimers. A combination reaction of two oxidized peroxy radicals has been previously reported to explain the rapid formation of dimers resulting in covalently bound molecules (see Sect. 3.3). The pronounced dimer signal with NH indicates that (low-volatility) dimers are necessary for positive ion nucleation and initial growth. We observed growth by dimer steps up to C80 and possibly even C100. A cluster of two dimers, C40, with a mass/charge in the range of ∼ 700–1100 Th, has a mobility diameter around 1.5 nm (based on Ehn et al., 2011).

Our observation of HOM–NH clusters implies strong hydrogen bonding between the two species. This is confirmed by quantum chemical calculations which shall be discussed in Sect. 3.3. Although hydrogen bonding could also be expected between HOMs and H3O+, we do not observe such clusters. This probably arises from the higher proton affinity of NH3, 203.6 kcal mol−1, compared with H2O, 164.8 kcal mol−1 (Hunter and Lias, 1998). Thus, most H3O+ ions in CLOUD will transfer their proton to NH3 to form NH.

3.1.2 Negative spectrum

In the negative spectra, the monomer, dimer, and trimer bands are observed during nucleation (Fig. 2). Monomers and dimers have similar signal intensities, whereas the trimer intensity is at least 10 times lower (Fig. 2a and b). The trimer signal is reduced since it is a cluster of two gas phase species (C10 + C20). Additionally, a lower transmission in the APi-TOF may also be a reason for the reduced signal.

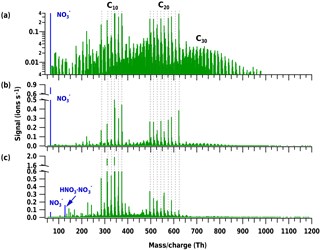

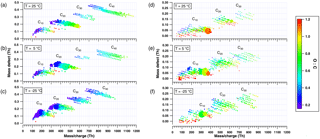

Figure 3Positive (a–c) and negative (d–f) mass spectra during pure biogenic nucleation induced by ozonolysis of α-pinene at three temperatures: 25 ∘C (a, d), 5 ∘C (b, e) and −25 ∘C (c, f). A progressive shift towards a lower oxygen content and lower masses is observed in all bands as the temperature decreases. Moreover, the appearance of C30 species can be seen in the positive spectrum at the lowest temperature (c).

In Fig. 2, we compare the CLOUD negative-ion spectrum with the one from nocturnal atmospheric measurements from the boreal forest at Hyytiälä as reported by Ehn et al. (2010). Figure 2a and b show the negative spectrum of α-pinene ozonolysis in the CLOUD chamber on logarithmic and linear scales, respectively. Figure 2c shows the Hyytiälä spectrum for comparison. Although the figure shows unit mass resolution, the high-resolution analysis confirms the identical composition for the main peaks: C8H12O7 ⋅ NO, C10H14O7 ⋅ NO, C10H14O8 ⋅ NO, C10H14O9 ⋅ NO, C10H16O10 ⋅ NO and C10H14O11 ⋅ NO (marked in the monomer region), and C19H28O11 ⋅ NO3, C19H28O12 ⋅ NO3, C20H30O12 ⋅ NO, C19H28O14 ⋅ NO, C20H30O14 ⋅ NO, C20H32O15 ⋅ NO, C20H30O16 ⋅ NO, C20H30O17 ⋅ NO and C20H30O18 ⋅ NO (marked in the dimer region). The close correspondence in terms of composition of the main HOMs from the lab and the field both in the monomer and dimer region indicates a close reproduction of the atmospheric nighttime conditions at Hyytiälä by the CLOUD experiment. In both cases the ion composition was dominated by HOMs clustered with NO. However, Ehn et al. (2010) did not report nocturnal nucleation, possibly because of a higher ambient condensation sink than in the CLOUD chamber.

3.2 Temperature dependence

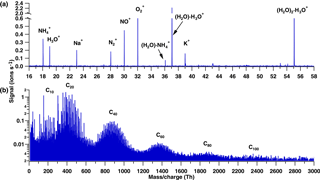

Experiments at three different temperatures (25, 5 and −25 ∘C) were conducted at similar relative humidity and ozone mixing ratios (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Mass defect plots are shown for the same data in Fig. 4. The mass defect is the difference between the exact and the integer mass and is shown on the y axis versus the mass/charge on the x axis. Each point represents a distinct atomic composition of a molecule or cluster. Although the observations described in the following are valid for both polarities, the trends at the three temperatures are better seen in the positive mass spectra due to a higher sensitivity at high m∕z.

The first point to note is the change in the distribution of the signal intensity seen in Fig. 3 (height of the peaks) and in Fig. 4 (size of the dots) with temperature. In the positive ion mode, the dimer band has the highest intensity at 25 and 5 ∘C (see also Fig. 1b), while at −25 ∘C the intensity of the monomer becomes comparable to that of the dimer. This indicates a reduced rate of dimer formation at −25 ∘C, or that the intensity of the ion signal depends on both the concentration of the neutral compound and on the stability of the ion cluster. Although the monomer concentration is higher than that of the dimers (Tröstl et al., 2016), the C20 ions are the more stable ion clusters as they can form more easily two hydrogen bonds with NH (see Sect. 3.3). Thus, positive clusters formed from monomers may not be stable enough at higher temperatures. Moreover, charge transfer to dimers is also favored.

The data also show a “shift” in all band distributions towards higher masses with increasing temperature, denoting a higher concentration of the more highly oxygenated molecules and the appearance of progressively more oxygenated compounds at higher temperatures. The shift is even more pronounced in the higher mass bands, as clearly seen in the C40 band of the positive ion mode in Fig. 3a–c. In this case the combination of two HOM dimers to a C40 cluster essentially doubles the shift of the band towards higher mass/charge at higher temperatures compared to the C20 band. Moreover, the width of each band increases with temperature, as clearly seen in the positive ion mode in Fig. 4, especially for the C40 band. At high temperatures, the production of more highly oxygenated HOMs seems to increase the possible combinations of clusters, resulting in a wider band distribution.

Figure 4Mass defect plots with the color code denoting the O : C ratio (of the organic core) at 25, 5 and −25 ∘C for positive (a–c) and negative ion mode (d–f). A lower O : C ratio is observed in the positive ion mode than in the negative ion mode. The intensity of the main peaks (linearly proportional to the size of the dots) changes with temperature for both polarities due to a lower degree of oxygenation at lower temperature.

This trend in the spectra indicates that the unimolecular autoxidation reaction accelerates at higher temperatures in competition to the bimolecular termination reactions with HO2 and RO2. This is expected. If unimolecular and bimolecular reactions are competitive, the unimolecular process will have a much higher barrier because the pre-exponential term for a unimolecular process is a vibrational frequency while the pre-exponential term for the bimolecular process is at most the bimolecular collision frequency, which is 4 orders of magnitude lower. Quantum chemical calculations determine activation energies between 22.56 and 29.46 kcal mol−1 for the autoxidation of different RO2 radicals from α-pinene (Rissanen et al., 2015). Thus, such a high barrier will strongly reduce the autoxidation rate at the low temperatures.

The change in the rate of autoxidation is also reflected in the O : C ratio, both in the positive ion mode (Fig. 4a–c), and the negative ion mode (Fig. 4d–f), showing a clear increase with increasing temperature. The average O : C ratios (weighted by the peak intensities) are presented in Table 2 for both polarities and the three temperatures, for all the identified peaks (total) and separately for the monomer and dimer bands. For a temperature change from 25 to −25 ∘C the O : C ratio decreases for monomers, dimers and total number of peaks. At high masses (e.g., for the C30 and C40 bands), the O : C ratio may be slightly biased since accurate identification of the molecules is less straightforward: as an example, C39H56O25 ⋅ NH has an exact mass-to-charge ratio of 942.34 Th (O ∕ C = 0.64), which is very similar to C40H60O24 ⋅ NH at 942.38 Th (O ∕ C = 0.60). However, such possible misidentification would not influence the calculated total O ∕ C by more than 0.05, and the main conclusions presented here remain robust.

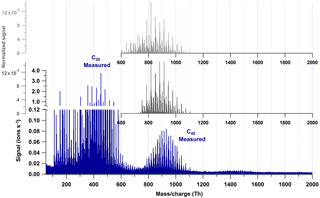

Figure 5Comparison of the positive ion mode spectrum measured (blue), the C40 band obtained by the combination of all C20 molecules (light gray), and the C40 band obtained by combination of only the C20 molecules with O ∕ C ≥ 0.4 (dark gray). The low or absent signals at the lower masses obtained by permutation suggest that only the highly oxygenated dimers are able to cluster and form C40.

The O : C ratios are higher for the negative ions than for the positive ions at any of the three temperatures. Although some of the organic cores are the same in the positive and negative ion mode, the intensity of the peaks of the most oxygenated species is higher in the negative spectra. While the measured O : C ratio ranges between 0.4 and 1.2 in the negative ion mode, it is between 0.1 and 1.2 in the positive ion mode. An O : C ratio of 0.1, which was detected only in the positive ion mode, corresponds to monomers and dimers with two oxygen atoms. The presence of molecules with such low oxygen content was also confirmed with a proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTR-TOF-MS), at least in the monomer region. Ions with O : C ratio less than 0.3 are probably from the main known oxidation products like pinonaldehyde, pinonic acid, etc., but also from minor products like pinene oxide and other not yet identified compounds. It is likely that these molecules, which were detected only in the positive mode, contribute only to the growth of the newly formed particles (if at all) rather than to nucleation, owing to their high volatility (Tröstl et al., 2016). In this sense, the positive spectrum could reveal both the molecules that participate in the new particle formation and those that contribute to growth. The differences in the O : C ratios between the two polarities are a result of the affinities of the organic molecules to form clusters either with NO or NH, which, in turn, depends on the molecular structure and the functional groups. Hyttinen et al. (2015) reported the binding energies of selected highly oxygenated products of cyclohexene detected by a nitrate CIMS, finding that the addition of OOH groups to the HOM strengthens the binding of the organic core with NO. Even when the number of H-bonds between NO and HOM remains the same, the addition of more oxygen atoms to the organic compound could strengthen the binding with the NO ion. Thus, the less oxygenated HOMs were not detected in those experiments, neither in ours, in the negative mode. The binding energies were calculated for the positive mode HOMs–NH and are discussed in Sect. 3.3.

We also tested to which extent the formation of the C40 band could be reproduced by permutation of the potential C20 molecules weighted by the dimer signal intensity. Figure 5 shows the measured spectrum (blue) and two types of modeled tetramers: one combining all peaks from the C20 band (light gray) and one combining only those peaks with an organic core with O ∕ C ≥ 0.4 – i.e., likely representing non-volatile C20 molecules (dark gray). The better agreement of the latter modeled mass spectrum of the tetramer band with the measured one suggests that only the molecules with O ∕ C ≥ 0.4 are able to form the tetramer cluster. This would mean that C20 molecules with 2–7 oxygen atoms are likely not to contribute to the nucleation, but only to the growth of the newly formed particles. One has to note that the comparison of modeled and measured spectra relies on the assumption that the charge distribution of dimers is also reflected in the tetramers.

These two observations (change in signal distribution and band “shift”) are not only valid for positive and negative ions, but also for the neutral molecules as observed by two nitrate chemical-ionization atmospheric-pressure-interface time-of-flight mass spectrometers (CI-APi-TOF; Aerodyne Research Inc. and Tofwerk AG). This confirms that there is indeed a change in the HOM composition with different temperature rather than a charge redistribution effect, which would only be observed for the ions (APi-TOF). The detailed analysis of the neutral molecules detected by these CI-APi-TOFs will be the subject of another paper and is not discussed here.

A third distinctive trend in the positive mode spectra at the three temperatures is the increase in signal intensity of the C30 band at −25 ∘C. The increase in the signal of the trimer also seems to occur in the negative ion mode when comparing Fig. 3d and f. For this polarity, data from two campaigns were combined (Table 1). To avoid a bias by possible differences in the APi-TOF settings, we only compare the temperatures from the same campaign, CLOUD 10, therefore experiments at 25 and −25 ∘C. The increase in the trimer signal may be due to greater stability of the monomer–dimer clusters or even of three C10 molecules at low temperatures, as further discussed below.

3.3 Quantum chemical calculations

Three points were addressed in the quantum chemical calculations to elucidate the most likely formation pathway for the first clusters, and its temperature dependence. These included (i) the stability of the organic cores with NO and NH depending on the binding functional group, (ii) the difference between charged and neutral clusters in terms of clustering energies, and finally (iii) the possible nature of clusters in the dimer and trimer region.

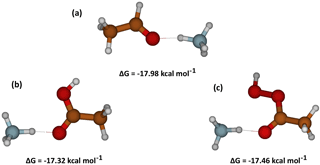

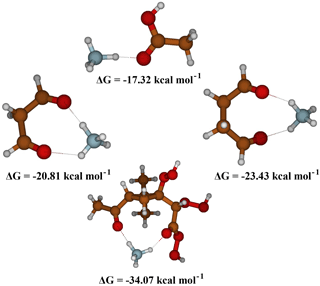

Figure 6Quantum chemical calculations of the free energy related to the cluster formation between NH and three structurally similar molecules with different functional groups: (a) acetaldehyde, (b) acetic acid and (c) peracetic acid.

The calculations showed that among the different functional groups the best interacting groups with NO are in order of importance carboxylic acids (R–C(= O)–OH), hydroxyls (R–OH), peroxy acids (R–C(= O)–O–OH), hydroperoxides (R–O–OH) and carbonyls (R–(R′–) C = O). On the other hand, NH preferably forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group independent of which functional group the carbonyl group is linked to; Fig. 6 shows examples of NH clusters with corresponding free energies of formation for carbonyls (ΔG = −17.98 kcal mol−1), carboxylic acid (ΔG = −17.32 kcal mol−1) and peroxy acid (ΔG = −17.46 kcal mol−1). For the three examples shown, the interaction of one hydrogen from NH with a C = O group is already very stable with a free energy of cluster ion formation close to −18 kcal mol−1.

To evaluate the effect of the presence of a second C = O on the binding of the organic compound with NH, we performed a series of calculations with a set of surrogates containing two C = O groups separated by different numbers of atoms, as shown in Fig. 7. The addition of a second functional group allows the formation of an additional hydrogen bond, increasing the stability of the cluster considerably (almost 2-fold) from about −18 to −34.07 kcal mol−1, whereby the position of the second functional group to form an optimal hydrogen bond (with a 180∘ angle for N–H–O) strongly influences the stability of the cluster, as can be seen in Fig. 7. Thus, optimal separation and conformational flexibility of functional groups is needed to enable effective formation of two hydrogen bonds with NH. This could be an explanation for the observation that the signal intensity is higher for dimers than for monomers, as dimers can more easily form two optimal hydrogen bonds with NH.

Figure 7Quantum chemical calculations for different organic molecules with a carbonyl as the interacting functional group with NH. Increasing the interacting groups from one to two increases the stability of the cluster. The distance between the interacting groups also influences the cluster stability.

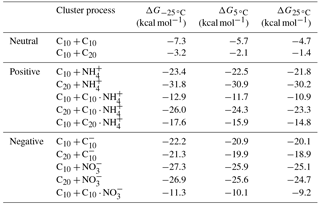

Table 3Gibbs free energies of cluster formation ΔG at three different temperatures. ΔG for the molecules C10H14O7 (C10) and C20H30O14 (C20) forming neutral, as well as negative and positive ion clusters.

As shown by Kirkby et al. (2016), ions increase the nucleation rates by 1–2 orders of magnitudes compared to neutral nucleation. This is expected due to the strong electrostatic interaction between charged clusters. To understand how the stability difference relates to the increase in the nucleation rate, the ΔG of charged and neutral clusters were compared. For this, C10H14O7 and C20H30O14 were selected as representative molecules of the monomer and dimer region, respectively (Kirkby et al., 2016). Table 3 shows the calculated free energies of formation (ΔG) of neutral, positive and negative clusters from these C10 and C20 molecules at the three temperatures of the experiment. Results show that at 5 ∘C, for example, ΔG of the neutral dimer (C10 + C10) is −5.76 kcal mol−1 while it decreases to −20.9 kcal mol−1 when a neutral and a negative ion form a cluster (C10 + C). Similarly, trimers show a substantial increase in stability when they are charged – i.e., from −2.1 to −19.9 kcal mol−1, for the neutral and negative cases, respectively. The reduced values of ΔG for the charged clusters (positive and negative) indicate a substantial decrease in the evaporation rate compared to that for neutral clusters, and, therefore, higher stability. Comparing the NH and NO clusters, the energies of formation for the monomer are −22.5 and −25.9 kcal mol−1, respectively, showing slightly higher stability for the negative cluster. Inversely, the covalently bound dimer showed greater stability for the positive ion (−30.9 kcal mol−1) compared to the negative ion (−25.6 kcal mol−1).

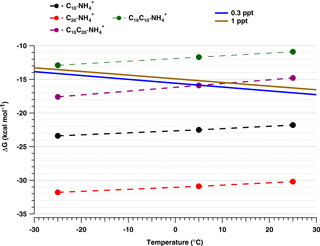

The temperature dependence of cluster formation is shown in Fig. 8 for the positive ion clusters. The blue and brown solid lines represent the needed ΔG for evaporation–collision equilibrium at 0.3 and 1 pptv HOM mixing ratio, respectively, calculated as described by Ortega et al. (2012). The markers show the calculated formation enthalpies ΔG for each of the possible clusters. For all cases, the trend shows an evident decrease in ΔG with decreasing temperature, with a correspondingly reduced evaporation rate.

Figure 8Quantum chemical calculations of Gibbs free energies for cluster formation at −25, 5 and 25 ∘C. Solid lines represent the required ΔG for equilibrium between evaporation and collision rates at 0.3 and 1 pptv of the HOM mixing ratio, respectively. Markers show the ΔG for each cluster (organic core clustered with NH) at the three temperatures. C10 ⋅ NH (black circles) represent the monomer, C20 ⋅ NH (red circles) represent the covalently bound dimer, C10C10 ⋅ NH (green circles) represent the dimer formed by the clustering of two monomers and C10C20 ⋅ NH (purple circles) denote the preferential pathway for the trimer cluster (see Table 3).

At all three temperatures, the monomer cluster C10 ⋅ NH falls well below the equilibrium lines, indicating high stability. Even though the difference between −25 and 25 ∘C is just −1.6 kcal mol−1 in free energy, it is enough to produce a substantial difference in the intensity of the band, increasing the signal at least 8-fold at −25 ∘C (as discussed in Sect. 3.2). In the case of the dimers, we consider the possibility of their formation by collision of a monomer C10 ⋅ NH with another C10 (resulting in a C10C10 ⋅ NH cluster) or the dimer as C20 ⋅ NH cluster. The calculations show clearly that the cluster C10C10 ⋅ NH is not stable at any of the three temperatures (green line). In contrast, the covalently bound C20 forms very stable positive and negative ion clusters (see Table 3). Trimers are mainly observed at lower temperatures. Since the C10C10 ⋅ NH cluster is not very stable, we discard the possibility of a trimer formation of the type C10C10C10 ⋅ NH. Thus, the trimer is likely the combination of a monomer and a covalently bound dimer (C20C10 ⋅ NH). According to our calculations (Table 3) the preferred evaporation path for this cluster is the loss of C10 rather than the evaporation of C20. Therefore, we have chosen to represent only this path in Fig. 8. The ΔG of this cluster crosses the evaporation–condensation equilibrium around 5 and 14 ∘C for a HOM mixing ratio of 0.3 and 1 pptv, respectively, in good agreement with the observed signal increase of the trimer at −25 ∘C (Fig. 3a–c). It is important to note that, due to the uncertainty in the calculations, estimated to be ≤ 2 kcal mol−1, we do not consider the crossing as an exact reference.

The ΔG of the negative ion clusters, which are also presented in Table 3, decrease similarly to the positive ion clusters by around 2 kcal mol−1 between 25 and −25 ∘C. The cluster formation energies of the monomer and the dimer with NO are in agreement with the observed comparable signal intensity in the spectrum (Fig. 2) in a similar way as the positive ion clusters. The covalently bonded dimer ion C20 ⋅ NO is also more stable compared to the dimer cluster C10C10 ⋅ NO, suggesting that the observed composition results from covalently bonded dimers clustering with NO rather than two individual C10 clustering to form a dimer.

The formation of a covalently bonded trimer seems unlikely, so the formation of highly oxygenated molecules is restricted to the monomer and dimer region. The trimer could result from the clustering of C10 and C20 species. Similarly, and based on the C20 pattern observed in Fig. 1b, we believe that the formation of the tetramer corresponds to the collision of two dimers. No calculations were done for this case due to the complexity related to the sizes of the molecules, which prevents feasible high-level quantum chemical calculations.

Finally, a comparison of the ΔG values as presented in Table 3 confirms the expected higher stability of charged clusters compared to neutral clusters, decreasing the evaporation rate of the nucleating clusters and enhancing new particle formation.

Ions observed during pure biogenic ion-induced nucleation were comprised of mainly organics clustered with NO and NH and to a lesser extent charged organic molecules only or organics clustered with HNO3NO. We found good correspondence between the negative ions measured in CLOUD and those observed in the boreal forest of Hyytiälä. The observed similarity in the composition of the HOMs in the monomer and dimer region during new-particle formation experiments at CLOUD suggests that pure biogenic nucleation might be possible during nighttime if the condensation sink is sufficiently low – i.e., comparable to that in the CLOUD chamber, where the wall loss rate for H2SO4 is 1.8 × 10−3 s−1 (Kirkby et al., 2016). The positive mass spectrum showed a distinctive pattern corresponding to progressive addition of dimers (C20), up to cluster sizes in the range of stable small particles.

Temperature strongly influenced the composition of the detected molecules in several ways. With increasing temperature, a higher oxygen content (O : C ratio) in the molecules was observed in both the positive and the negative mode. This indicates an increase in the autoxidation rate of peroxy radicals, which is in competition with their bimolecular termination reactions with HO2 and RO2.

A broader range of organic molecules was found to form clusters with NH than with NO. Quantum chemical calculations using simplified molecules show that NH preferably forms a hydrogen bond with a carbonyl group independently of other functional groups nearby. The addition of a second hydrogen bond was found to increase the cluster stability substantially. Thus, the C20 ions are the more stable ion clusters as they can form more easily two hydrogen bonds with NH. Although molecules with low oxygen content were measured in the C20 band (1–4 oxygen atoms), only the molecules with O ∕ C ≥ 0.4 seem to be able to combine to form larger clusters.

The quantum chemical calculations showed that the covalently bonded dimer C20 ⋅ NO is also more stable than the dimer cluster C10C10 ⋅ NO, suggesting that the observed composition results from covalently bonded molecules clustering with NO rather than C10 clusters.

Temperature affected cluster formation by decreasing evaporation rates at lower temperatures, despite the lower O : C ratio. In the positive mode a pronounced growth of clusters by addition of C20–HOMs was observed. The formation of a C30 cluster only appeared at the lowest temperature, which was supported by quantum chemical calculations. In the negative mode it appeared as well that the signal of the C30 clusters became stronger with lower temperature. The C40 and higher clusters were probably not seen because of too low sensitivity in this mass range due to the applied instrumental settings. More measurements are needed to determine if the cluster growth of positive and negative ions proceeds in a similar or different way.

Nucleation and early growth is driven by the extremely low volatility compounds – i.e., dimers and monomers of high O : C ratios (Tröstl et al., 2016). Here, we observe a reduction of the autoxidation rate leading to oxidation products with lower O : C ratios with decreasing temperature. We expect that this is accompanied by a reduction of nucleation rates. However, a lower temperature reduces evaporation rates of clusters and thereby supports nucleation. The relative magnitude of these compensating effects will be subject of further investigations.

Data related to this article are available online at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1133985.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank CERN for supporting CLOUD with important technical and

financial resources, and for providing a particle beam from the CERN Proton

Synchrotron. We also thank P. Carrie, L.-P. De Menezes, J. Dumollard, K. Ivanova,

F. Josa, I. Krasin, R. Kristic, A. Laassiri, O. S. Maksumov, B. Marichy,

H. Martinati, S. V. Mizin, R. Sitals, A. Wasem and M. Wilhelmsson

for their important contributions to the experiment. This research has

received funding from the EC Seventh Framework Programme (Marie Curie Initial

Training Network CLOUD-ITN no. 215072, MC-ITN CLOUD-TRAIN no. 316662,

the ERC-Starting grant MOCAPAF no. 57360, the ERC-Consolidator grant

NANODYNAMITE no. 616075 and ERC-Advanced grant ATMNUCLE no. 227463),

European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the

Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 656994, the PEGASOS project funded

by the European Commission under the Framework Programme 7

(FP7-ENV-2010-265148), the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research

(project nos. 01LK0902A and 01LK1222A), the Swiss National Science Foundation

(project nos. 200020_152907, 206021_144947 and

20FI20_159851), the Academy of Finland (Center of Excellence

project no. 1118615), the Academy of Finland (135054, 133872, 251427, 139656,

139995, 137749, 141217, 141451, 299574), the Finnish Funding Agency for

Technology and Innovation, the Väisälä Foundation, the Nessling

Foundation, the University of Innsbruck research grant for young scientists

(Cluster Calibration Unit), the Portuguese Foundation for Science and

Technology (project no. CERN/FP/116387/2010), the Swedish Research Council,

Vetenskapsrådet (grant 2011-5120), the Presidium of the Russian Academy

of Sciences and Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grants 08-02-91006-CERN

and 12-02-91522-CERN), the US National Science Foundation

(grants AGS1447056, and AGS1439551), and the Davidow Foundation. We thank the

tofTools team for providing tools for mass spectrometry analysis.

Edited by: Sergey A. Nizkorodov

Reviewed by: two anonymous referees

Almeida, J., Schobesberger, S., Kürten, A., Ortega, I. K., Kupiainen-Määttä, O., Praplan, A. P., Adamov, A., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., David, A., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Downard, A., Dunne, E., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Henschel, H., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kajos, M., Kangasluoma, J., Keskinen, H., Kupc, A., Kurtén, T., Kvashin, A. N., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Leiminger, M., Leppä, J., Loukonen, V., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., McGrath, M. J., Nieminen, T., Olenius, T., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Riccobono, F., Riipinen, I., Rissanen, M., Rondo, L., Ruuskanen, T., Santos, F. D., Sarnela, N., Schallhart, S., Schnitzhofer, R., Seinfeld, J. H., Simon, M., Sipilä, M., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tomé, A., Tröstl, J., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Vaattovaara, P., Viisanen, Y., Virtanen, A., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Weingartner, E., Wex, H., Williamson, C., Wimmer, D., Ye, P., Yli-Juuti, T., Carslaw, K. S., Kulmala, M., Curtius, J., Baltensperger, U., Worsnop, D. R., Vehkamäki, H., and Kirkby, J.: Molecular understanding of sulphuric acid-amine particle nucleation in the atmosphere, Nature, 502, 359–363, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12663, 2013.

Andreae, M. O., Afchine, A., Albrecht, R., Holanda, B. A., Artaxo, P., Barbosa, H. M. J., Bormann, S., Cecchini, M. A., Costa, A., Dollner, M., Fütterer, D., Järvinen, E., Jurkat, T., Klimach, T., Konemann, T., Knote, C., Krämer, M., Krisna, T., Machado, L. A. T., Mertes, S., Minikin, A., Pöhlker, C., Pöhlker, M. L., Pöschl, U., Rosenfeld, D., Sauer, D., Schlager, H., Schnaiter, M., Schneider, J., Schulz, C., Spanu, A., Sperling, V. B., Voigt, C., Walser, A., Wang, J., Weinzierl, B., Wendisch, M., and Ziereis, H.: Aerosol characteristics and particle production in the upper troposphere over the Amazon Basin, Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2017-694, in review, 2017.

Bianchi, F., Tröstl, J., Junninen, H., Frege, C., Henne, S., Hoyle, C. R., Molteni, U., Herrmann, E., Adamov, A., Bukowiecki, N., Chen, X., Duplissy, J., Gysel, M., Hutterli, M., Kangasluoma, J., Kontkanen, J., Kürten, A., Manninen, H. E., Münch, S., Peräkylä, O., Petäjä, T., Rondo, L., Williamson, C., Weingartner, E., Curtius, J., Worsnop, D. R., Kulmala, M., Dommen, J., and Baltensperger, U.: New particle formation in the free troposphere: A question of chemistry and timing, Science, 352, 1109–1112, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5456, 2016.

Boucher, O., Randall, D., Artaxo, P., Bretherton, C., Feingold, G., Forster, P., Kerminen, V.-M. V.-M., Kondo, Y., Liao, H., Lohmann, U., Rasch, P., Satheesh, S. K., Sherwood, S., Stevens, B., Zhang, X. Y., and Zhan, X. Y.: Clouds and Aerosols, in: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Clim. Chang. 2013 Phys. Sci. Basis. Contrib. Work. Gr. I to Fifth Assess. Rep. Intergov. Panel Clim. Chang., 571–657, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.016, 2013.

Crounse, J. D., Nielsen, L. B., Jørgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Autoxidation of organic compounds in the atmosphere, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 4, 3513–3520, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz4019207, 2013.

Ditchfield, R.: Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. IX. An extended gaussian-type basis for molecular-orbital studies of organic molecules, J. Chem. Phys., 54, 724–728, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1674902, 1971.

Dunne, E. M., Gordon, H., Kürten, A., Almeida, J., Duplissy, J., Williamson, C., Ortega, I. K., Pringle, K. J., Adamov, A., Baltensperger, U., Barmet, P., Benduhn, F., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Clarke, A., Curtius, J., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Jokinen, T., Kangasluoma, J., Kirkby, J., Kulmala, M., Kupc, A., Lawler, M. J., Lehtipalo, K., Makhmutov, V., Mann, G., Mathot, S., Merikanto, J., Miettinen, P., Nenes, A., Onnela, A., Rap, A., Reddington, C. L. S., Riccobono, F., Richards, N. A. D., Rissanen, M. P., Rondo, L., Sarnela, N., Schobesberger, S., Sengupta, K., Simon, M., Sipilä, M., Smith, J. N., Stozkhov, Y., Tomé, A., Tröstl, J., Wagner, P. E., Wimmer, D., Winkler, P. M., Worsnop, D. R., and Carslaw, K. S.: Global atmospheric particle formation from CERN CLOUD measurements, Science, 354, 1119–1124, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2649, 2016.

Duplissy, J., Merikanto, J., Franchin, A., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Kangasluoma, J., Wimmer, D., Vuollekoski, H., Schobesberger, S., Lehtipalo, K., Flagan, R. C., Brus, D., Donahue, N. M., Vehkamäki, H., Almeida, J., Amorim, A., Barmet, P., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Dunne, E. M., Guida, R., Henschel, H., Junninen, H., Kirkby, J., Kürten, A., Kupc, A., Määttänen, A., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Nieminen, T., Onnela, A., Praplan, A. P., Riccobono, F., Rondo, L., Steiner, G., Tomé, A., Walther, H., Baltensperger, U., Carslaw, K. S., Dommen, J., Hansel, A., Petäjä, T., Sipilä, M., Stratmann, F., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Worsnop, D. R., Curtius, J., and Kulmala, M.: Effect of ions on sulfuric acid-water binary particle formation: 2. Experimental data and comparison with QC-normalized classical nucleation theory, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023538, 2016.

Ehn, M., Junninen, H., Petäjä, T., Kurtén, T., Kerminen, V.-M., Schobesberger, S., Manninen, H. E., Ortega, I. K., Vehkamäki, H., Kulmala, M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Composition and temporal behavior of ambient ions in the boreal forest, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 8513–8530, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-8513-2010, 2010.

Ehn, M., Junninen, H., Schobesberger, S., Manninen, H. E., Franchin, A., Sipilä, M., Petäjä, T., Kerminen, V.-M., Tammet, H., Mirme, A., Mirme, S., Hõrrak, U., Kulmala, M., and Worsnop, D. R.: An instrumental comparison of mobility and mass measurements of atmospheric small ions, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 45, 522–532, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2010.547890, 2011.

Ehn, M., Thornton, J. a., Kleist, E., Sipilä, M., Junninen, H., Pullinen, I., Springer, M., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Lee, B., Lopez-Hilfiker, F., Andres, S., Acir, I.-H., Rissanen, M., Jokinen, T., Schobesberger, S., Kangasluoma, J., Kontkanen, J., Nieminen, T., Kurtén, T., Nielsen, L. B., Jørgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., Canagaratna, M., Maso, M. D., Berndt, T., Petäjä, T., Wahner, A., Kerminen, V.-M., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Wildt, J., and Mentel, T. F.: A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol, Nature, 506, 476–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13032, 2014.

Franchin, A., Ehrhart, S., Leppä, J., Nieminen, T., Gagné, S., Schobesberger, S., Wimmer, D., Duplissy, J., Riccobono, F., Dunne, E. M., Rondo, L., Downard, A., Bianchi, F., Kupc, A., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Lehtipalo, K., Manninen, H. E., Almeida, J., Amorim, A., Wagner, P. E., Hansel, A., Kirkby, J., Kürrten, A., Donahue, N. M., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Metzger, A., Petäjä, T., Schnitzhofer, R., Sipilä, M., Stozhkov, Y., Tomé, A., Kerminen, V. M., Carslaw, K., Curtius, J., Baltensperger, U., and Kulmala, M.: Experimental investigation of ion-ion recombination under atmospheric conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 7203–7216, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-7203-2015, 2015.

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Caricato, M., Li, X., Hratchian, H. P., Izmaylov, A. F., Bloino, J., Zheng, G., Sonnenberg, J. L., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Montgomery Jr., J. A., Peralta, J. E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M., Heyd, J. J., Brothers, E., Kudin, K. N., Staroverov, V. N., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A., Burant, J. C., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Rega, N., Millam, J. M., Klene, M., Knox, J. E., Cross, J. B., Bakken, V., Adamo, C., Jaramillo, J.,Gomperts, R., Stratmann, R. E., Yazyev, O., Austin, A. J., Cammi, R., Pomelli, C., Ochterski, J. W., Martin, R. L., Morokuma, K., Zakrzewski, V. G., Voth, G. A., Salvador, P., Dannenberg, J. J., Dapprich, S., Daniels, A. D., Farkas, O., Foresman, J. B., Ortiz, J. V.,Cioslowski, J., and Fox, D. J.: Gaussian 09, Revision B01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.

Hirsikko, A., Nieminen, T., Gagné, S., Lehtipalo, K., Manninen, H. E., Ehn, M., Hõrrak, U., Kerminen, V.-M., Laakso, L., McMurry, P. H., Mirme, A., Mirme, S., Petäjä, T., Tammet, H., Vakkari, V., Vana, M., and Kulmala, M.: Atmospheric ions and nucleation: a review of observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 767–798, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-767-2011, 2011.

Hoyle, C. R., Fuchs, C., Jarvinen, E., Saathoff, H., Dias, A., El Haddad, I., Gysel, M., Coburn, S. C., Trostl, J., Hansel, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Corbin, J. C., Craven, J., Donahue, N. M., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Frege, C., Gordon, H., Hoppel, N., Heinritzi, M., Kristensen, T. B., Molteni, U., Nichman, L., Pinterich, T., Prevôt, A. S. H., Simon, M., Slowik, J. G., Steiner, G., Tome, A., Vogel, A. L., Volkamer, R., Wagner, A. C., Wagner, R., Wexler, A. S., Williamson, C., Winkler, P. M., Yan, C., Amorim, A., Dommen, J., Curtius, J., Gallagher, M. W., Flagan, R. C., Hansel, A., Kirkby, J., Kulmala, M., Mohler, O., Stratmann, F., Worsnop, D. R., and Baltensperger, U.: Aqueous phase oxidation of sulphur dioxide by ozone in cloud droplets, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 1693–1712, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-1693-2016, 2016.

Hunter, E. P. and Lias, S. G.: Evaluate gas phase basicities and proton affinity of molecules: an update, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 27, 413–656, 1998.

Hyttinen, N., Kupiainen-Määttä, O., Rissanen, M. P., Muuronen, M., Ehn, M., and Kurtén, T.: Modeling the charging of highly oxidized cyclohexene ozonolysis products using nitrate-based chemical ionization, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 6339–6345, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b01818, 2015.

Kirkby, J., Curtius, J., Almeida, J., Dunne, E., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Franchin, A., Gagné, S., Ickes, L., Kürten, A., Kupc, A., Metzger, A., Riccobono, F., Rondo, L., Schobesberger, S., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Wimmer, D., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., David, A., Dommen, J., Downard, A., Ehn, M., Flagan, R. C., Haider, S., Hansel, A., Hauser, D., Jud, W., Junninen, H., Kreissl, F., Kvashin, A., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Lima, J., Lovejoy, E. R., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Mikkilä, J., Minginette, P., Mogo, S., Nieminen, T., Onnela, A., Pereira, P., Petäjä, T., Schnitzhofer, R., Seinfeld, J. H., Sipilä, M., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tomé, A., Vanhanen, J., Viisanen, Y., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Walther, H., Weingartner, E., Wex, H., Winkler, P. M., Carslaw, K. S., Worsnop, D. R., Baltensperger, U., and Kulmala, M.: Role of sulphuric acid, ammonia and galactic cosmic rays in atmospheric aerosol nucleation, Nature, 476, 429–433, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10343, 2011.

Kirkby, J., Duplissy, J., Sengupta, K., Frege, C., Gordon, H., Williamson, C., Heinritzi, M., Simon, M., Yan, C., Almeida, J., Tröstl, J., Nieminen, T., Ortega, I. K., Wagner, R., Adamov, A., Amorim, A., Bernhammer, A.-K., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Brilke, S., Chen, X., Craven, J., Dias, A., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Fuchs, C., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hoyle, C. R., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kangasluoma, J., Kim, J., Krapf, M., Kürten, A., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Molteni, U., Onnela, A., Peräkylä, O., Piel, F., Petäjä, T., Praplan, A. P., Pringle, K., Rap, A., Richards, N. A. D., Riipinen, I., Rissanen, M. P., Rondo, L., Sarnela, N., Schobesberger, S., Scott, C. E., Seinfeld, J. H., Sipilä, M., Steiner, G., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tomé, A., Virtanen, A., Vogel, A. L., Wagner, A. C., Wagner, P. E., Weingartner, E., Wimmer, D., Winkler, P. M., Ye, P., Zhang, X., Hansel, A., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Worsnop, D. R., Baltensperger, U., Kulmala, M., Carslaw, K. S., and Curtius, J.: Ion-induced nucleation of pure biogenic particles, Nature, 533, 521–526, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17953, 2016.

Kulmala, M., Vehkamäki, H., Petäjä, T., Dal Maso, M., Lauri, A., Kerminen, V. M., Birmili, W., and McMurry, P. H.: Formation and growth rates of ultrafine atmospheric particles: A review of observations, J. Aerosol Sci., 35, 143–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2003.10.003, 2004.

Kulmala, M., Kontkanen, J., Junninen, H., Lehtipalo, K., Manninen, H. E., Nieminen, T., Petäjä, T., Sipilä, M., Schobesberger, S., Rantala, P., Franchin, A., Jokinen, T., Järvinen, E., Äijälä, M., Kangasluoma, J., Hakala, J., Aalto, P. P., Paasonen, P., Mikkilä, J., Vanhanen, J., Aalto, J., Hakola, H., Makkonen, U., Ruuskanen, T., Mauldin, R. L., Duplissy, J., Vehkamäki, H., Bäck, J., Kortelainen, A., Riipinen, I., Kurtén, T., Johnston, M. V, Smith, J. N., Ehn, M., Mentel, T. F., Lehtinen, K. E. J., Laaksonen, A., Kerminen, V.-M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Direct observations of atmospheric aerosol nucleation, Science, 339, 943–946, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1227385, 2013.

Kürten, A., Bianchi, F., Almeida, J., Kupiainen-Määttä, O., Dunne, E. M., Duplissy, J., Williamson, C., Barmet, P., Breitenlechner, M., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Gordon, H., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Ickes, L., Jokinen, T., Kangasluoma, J., Kim, J., Kirkby, J., Kupc, A., Lehtipalo, K., Leiminger, M., Makhmutov, V., Onnela, A., Ortega, I. K., Petäjä, T., Praplan, A. P., Riccobono, F., Rissanen, M. P., Rondo, L., Schnitzhofer, R., Schobesberger, S., Smith, J. N., Steiner, G., Stozkhov, Y., Tomé, A., Tröstl, J., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Wagner, P. E., Wimmer, D., Ye, P., Baltensperger, U., Carslaw, K. S., Kulmala, M., and Curtius, J.: Experimental particle formation rates spanning tropospheric sulfuric acid and ammonia abundances, ion production rates, and temperatures, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 12377–12400, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023908, 2016.

Lehtipalo, K., Rondo, L., Kontkanen, J., Schobesberger, S., Jokinen, T., Sarnela, N., Kürten, A., Ehrhart, S., Franchin, A., Nieminen, T., Riccobono, F., Sipilä, M., Yli-Juuti, T., Duplissy, J., Adamov, A., Ahlm, L., Almeida, J., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Dommen, J., Downard, A. J., Dunne, E. M., Flagan, R. C., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Jud, W., Kangasluoma, J., Kerminen, V.-M., Keskinen, H., Kim, J., Kirkby, J., Kupc, A., Kupiainen-Määttä, O., Laaksonen, A., Lawler, M. J., Leiminger, M., Mathot, S., Olenius, T., Ortega, I. K., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Praplan, A. P., Rissanen, M. P., Ruuskanen, T. M., Santos, F. D., Schallhart, S., Schnitzhofer, R., Simon, M., Smith, J. N., Tröstl, J., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Tomé, A., Vaattovaara, P., Vehkämäki, H., Vrtala, A. E., Wagner, P. E., Williamson, C., Wimmer, D., Winkler, P. M., Virtanen, A., Donahue, N. M., Carslaw, K. S., Baltensperger, U., Riipinen, I., Curtius, J., Worsnop, D. R., and Kulmala, M.: The effect of acid-base clustering and ions on the growth of atmospheric nano-particles, Nat. Commun., 7, 11594, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11594, 2016.

Merikanto, J., Spracklen, D. V., Mann, G. W., Pickering, S. J., and Carslaw, K. S.: Impact of nucleation on global CCN, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 8601–8616, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-8601-2009, 2009.

Merikanto, J., Duplissy, J., Määttänen, A., Henschel, H., Donahue, N. M., Brus, D., Schobesberger, S., Kulmala, M., and Vehkamäki, H.: Effect of ions on sulfuric acid-water binary particle formation I: Theory for kinetic and nucleation-type particle formation and atmospheric implications, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 1736–1751, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023538, 2016.

Metzger, A., Verheggen, B., Dommen, J., Duplissy, J., Prevot, A. S. H., Weingartner, E., Riipinen, I., Kulmala, M., Spracklen, D. V, Carslaw, K. S., and Baltensperger, U.: Evidence for the role of organics in aerosol particle formation under atmospheric conditions, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 6646–6651, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911330107, 2010.

Nadykto, A. B.: Uptake of neutral polar vapor molecules by charged clusters/particles: Enhancement due to dipole-charge interaction, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 108, 4717, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JD003664, 2003.

Ortega, I. K., Kupiainen, O., Kurtén, T., Olenius, T., Wilkman, O., McGrath, M. J., Loukonen, V., and Vehkamäki, H.: From quantum chemical formation free energies to evaporation rates, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 225–235, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-225-2012, 2012.

Praplan, A. P., Schobesberger, S., Bianchi, F., Rissanen, M. P., Ehn, M., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Adamov, A., Amorim, A., Dommen, J., Duplissy, J., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Kangasluoma, J., Kirkby, J., Krapf, M., Kürten, A., Lehtipalo, K., Riccobono, F., Rondo, L., Sarnela, N., Simon, M., Tomé, A., Tröstl, J., Winkler, P. M., Williamson, C., Ye, P., Curtius, J., Baltensperger, U., Donahue, N. M., Kulmala, M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Elemental composition and clustering behaviour of α-pinene oxidation products for different oxidation conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 4145–4159, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-4145-2015, 2015.

Riccobono, F., Schobesberger, S., Scott, C. E., Dommen, J., Ortega, I. K., Rondo, L., Almeida, J., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., David, A., Downard, A., Dunne, E. M., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Hansel, A., Junninen, H., Kajos, M., Keskinen, H., Kupc, A., Kürten, A., Kvashin, A. N., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Nieminen, T., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Praplan, A. P., Santos, F. D., Schallhart, S., Seinfeld, J. H., Sipilä, M., Spracklen, D. V., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tomé, A., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Vaattovaara, P., Viisanen, Y., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Donahue, N. M., Kirkby, J., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., and Baltensperger, U.: Oxidation products of biogenic emissions contribute to nucleation of atmospheric particles, Science, 344, 717–721, 2014.

Rissanen, M. P., Kurtén, T., Sipilä, M., Thornton, J. A., Kausiala, O., Garmash, O., Kjaergaard, H. G., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D. R., Ehn, M., and Kulmala, M.: Effects of chemical complexity on the autoxidation mechanisms of endocyclic alkene ozonolysis products: From methylcyclohexenes toward understanding α-pinene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 4633–4650, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp510966g, 2015.

Schobesberger, S., Junninen, H., Bianchi, F., Lönn, G., Ehn, M., Lehtipalo, K., Dommen, J., Ehrhart, S., Ortega, I. K., Franchin, A., Nieminen, T., Riccobono, F., Hutterli, M., Duplissy, J., Almeida, J., Amorim, A., Breitenlechner, M., Downard, A. J., Dunne, E. M., Flagan, R. C., Kajos, M., Keskinen, H., Kirkby, J., Kupc, A., Kürten, A., Kurtén, T., Laaksonen, A., Mathot, S., Onnela, A., Praplan, A. P., Rondo, L., Santos, F. D., Schallhart, S., Schnitzhofer, R., Sipilä, M., Tomé, A., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Vehkamäki, H., Wimmer, D., Baltensperger, U., Carslaw, K. S., Curtius, J., Hansel, A., Petäjä, T., Kulmala, M., Donahue, N. M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Molecular understanding of atmospheric particle formation from sulfuric acid and large oxidized organic molecules, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 17223–17228, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1306973110, 2013.

Shuman, N. S., Hunton, D. E., and Viggiano, A. A.: Ambient and modified atmospheric ion chemistry: from top to bottom, Chem. Rev., 115, 4542–4570, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr5003479, 2015.

Steiner, G., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Sipilä, M., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D., Reischl, G. P., and Kulmala, M.: High-resolution mobility and mass spectrometry of negative ions produced in a 241 Am aerosol charger, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 48, 261–270, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2013.870327, 2014.

Suni, T., Kulmala, M., Hirsikko, A., Bergman, T., Laakso, L., Aalto, P. P., Leuning, R., Cleugh, H., Zegelin, S., Hughes, D., van Gorsel, E., Kitchen, M., Vana, M., Hõrrak, U., Mirme, S., Mirme, A., Sevanto, S., Twining, J., and Tadros, C.: Formation and characteristics of ions and charged aerosol particles in a native Australian Eucalypt forest, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 129–139, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-129-2008, 2008.

Tröstl, J., Chuang, W. K., Gordon, H., Heinritzi, M., Yan, C., Molteni, U., Ahlm, L., Frege, C., Bianchi, F., Wagner, R., Simon, M., Lehtipalo, K., Williamson, C., Craven, J. S., Duplissy, J., Adamov, A., Almeida, J., Bernhammer, A.-K., Breitenlechner, M., Brilke, S., Dias, A., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Fuchs, C., Guida, R., Gysel, M., Hansel, A., Hoyle, C. R., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kangasluoma, J., Keskinen, H., Kim, J., Krapf, M., Kürten, A., Laaksonen, A., Lawler, M. J., Leiminger, M., Mathot, S., Möhler, O., Nieminen, T., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Piel, F., Miettinen, P., Rissanen, M. P., Rondo, L., Sarnela, N., Schobesberger, S., Sengupta, K., Sipilä, M., Smith, J. N., Steiner, G., Tomé, A., Virtanen, A., Wagner, A. C., Weingartner, E., Wimmer, D., Winkler, P. M., Ye, P., Carslaw, K. S., Curtius, J., Dommen, J., Kirkby, J., Kulmala, M., Riipinen, I., Worsnop, D. R., Donahue, N. M., and Baltensperger, U.: The role of low-volatility organic compounds for initial particle growth in the atmosphere, Nature, 533, 527–531, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18271, 2016.

Zhao, Y. and Truhlar, D. G.: The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other function, Theor. Chem. Acc., 120, 215–241, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x, 2008.