the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Transported African Dust in the Lower Marine Atmospheric Boundary Layer is Internally Mixed with Sea Salt Contributing to Increased Hygroscopicity and a Lower Lidar Depolarization Ratio

Sujan Shrestha

Robert E. Holz

Willem J. Marais

Zachary Buckholtz

Ilya Razenkov

Edwin Eloranta

Jeffrey S. Reid

Hope E. Elliott

Nurun Nahar Lata

Zezhen Cheng

Swarup China

Edmund Blades

Albert D. Ortiz

Rebecca Chewitt-Lucas

Alyson Allen

Devon Blades

Ria Agrawal

Elizabeth A. Reid

Jesus Ruiz-Plancarte

Anthony Bucholtz

Ryan Yamaguchi

Qing Wang

Thomas Eck

Elena Lind

Mira L. Pöhlker

Andrew P. Ault

Saharan dust is frequently transported across the Atlantic, yet the chemical, physical, and morphological transformations dust undergoes within the marine atmospheric boundary layer (MABL) remain poorly understood. These transformations are critical for understanding dust's radiative and geochemical impacts, it's representation in atmospheric models, and detection via remote sensing. Here, we present coordinated observations from the Office of Naval Research's Moisture and Aerosol Gradients/Physics of Inversion Evolution (MAGPIE) August 2023 campaign at Ragged Point, Barbados. These include vertically resolved single-particle analyses, mass concentrations of dust and sea spray, and High Spectral Resolution Lidar (HSRL) retrievals. Single-particle data show that dust within the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) remains externally mixed, with a corresponding high HSRL-derived linear depolarization ratio (LDR) at 532 nm of ∼ 0.3. However, at lower altitudes, dust becomes internally mixed with sea spray, and under the high humidity (>80 %) of the MABL undergoes hygroscopic growth, yielding more spherical particles, suppressing the LDR to <0.1; even in the presence of high dust loadings (e.g., ∼ 120 µg m−3). This low depolarization in the MABL is likely due to a combination of the differences between the single scattering properties of dust and spherical particles, and the potential modification of the dust optical properties from an increased hygroscopicity of dust caused by the mixing with sea salt in the humid MABL. These results highlight the importance of the aerosol particle mixing state when interpreting LDR-derived dust retrievals and estimating surface dust concentrations in satellite products and atmospheric models.

- Article

(5882 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(940 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The transport of Saharan dust across the North Atlantic Basin throughout the year is one of the largest aerosol phenomena observable from space. The most intensive events often occur during the boreal summer when large quantities of dust are lofted and advected westward by trade winds within the Saharan Air Layer (SAL), a well-defined elevated layer extending from ∼ 2 to 5 km above mean sea level (a.m.s.l.) (e.g., Carlson and Prospero, 1972; Karyampudi et al., 1999; Adams et al., 2012; Tsamalis et al., 2013; Mehra et al., 2023). This conceptual model of African dust transport is frequently reinforced by satellite and ground-based remote sensing, particularly lidar (Burton et al., 2012, 2015), multi-angle imager (Kalashnikova et al., 2013), polarimetric (Huang et al., 2015) or combination of these observations (Moustaka et al., 2025) that rely on dust's asphericity to differentiate coarse mode dust from other aerosol sources such as hydrated sea spray. These techniques often detect little dust within the lower marine atmospheric boundary layer (MABL). However, it is well known that exceptionally high dust concentrations are often directly measured in the MABL (e.g., Reid et al., 2003b; Zuidema et al., 2019; Elliott et al., 2024; Mayol-Bracero et al., 2025) and these layers are regularly forecast by operational dust transport models (Xian et al., 2019). This contradiction between the common conceptual model fueled by remote sensing of elevated dust layers versus evidence of significant near-surface dust mass concentrations by in situ observations raises a critical question, is there an observational gap in the detection and characterization of dust within the MABL?

Among the methods to speciate airborne dust from other aerosol particle types, the most common benchmark is to rely on dust's asphericity, and its impact on lidar's linear depolarization ratio (LDR). The LDR is based on a lidar's range-resolved measurement of the fraction of backscattered light by aerosol particles that become depolarized from the original polarized laser pulse. Backscattered light from homogeneous spherical particles, such as hydrated sea salt, has low depolarization (e.g., LDR remains minimal) whereas particles with asymmetry such as dry, irregular dust will return a partially depolarized signal, typically ∼ 0.25–0.40 (Murayama et al., 1999; Ansmann et al., 2012; Burton et al., 2012; Freudenthaler et al., 2009; Sakai et al., 2010; Groß et al., 2016).

The assertion that dust can be isolated from other aerosol types such as in the references above is well supported by both theoretical foundations and numerous observations of elevated dust plumes. An important assumption in the detection of dust via the LDR is that the dust is not hygroscopic. In situ observations of dust hygroscopicity in the MABL, typically using the standard technique of drying and subsequently rehydrating particles ahead of nephelometer measurements (Orozco et al., 2016), have suggested MABL dust is not significantly hygroscopic (Li-Jones et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2014). Thus, it is often assumed that dust in the humid MABL will retain its aspherical shape and remain tracible via the LDR. However, even freshly emitted dust or that which is sampled well within a dust plume can contain soluble minerals that should be inherently hygroscopic and could affect detection of dust via the LDR (Koehler et al., 2007; Reid et al., 2003a).

Contradictory observations have introduced uncertainty in the interpretation of lidar observations for dust detection in the MABL. For example, during the SALTRACE campaign in Barbados, lidar-derived LDR measurements within the lower MABL were 0.15 ± 0.02, suggesting approximately equal parts spherical and non-spherical particles, despite in-situ observations indicating surface dust mass concentrations as high as 40 µg m−3 (Groß et al., 2016; Weinzierl et al., 2017). Groß et al. (2016) also reported that dust mass concentrations exceeding 40 µg m−3 could be underestimated by up to 50 % by lidar-derived depolarization measurements, in part due to the dominant influence of sea spray in the MABL that introduces large concentrations of hydrated, spherical particles that reduce the overall depolarization signal. Tsamalis et al. (2013) emphasized that the polluted dust aerosol type is often misclassified or detected less often in spaceborne CALIOP observations due to low depolarization signals resulting from dust mixing with other aerosol types such as biomass burning, marine or anthropogenic aerosols (Yang et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2022). The relationship between dust mass and depolarization has important implications for how the depolarization ratio is used to infer surface-level dust concentrations in air quality forecasts and climate models. Since satellite retrievals and column-integrated techniques lack vertical resolution, they may fail to capture such near-surface morphological changes in dust (Li et al., 2020). If depolarization-based methods underestimate dust presence near the surface under marine conditions, it could introduce systematic errors in dust-related radiative forcing and deposition estimates. A similar concern exists for multi-angle imagers and polarimetric retrievals that depend on assumptions of particle asymmetry to detect and quantify dust.

During August 2023, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) initiated the Moisture and Aerosol Gradients/Physics of Inversion Evolution (MAGPIE) field campaign at the University of Miami's Barbados Atmospheric Chemistry Observatory (BACO) at Ragged Point, Barbados to map the inhomogeneity of the MABL. Central to MAGPIE are studies to identify information lost when one conceptualizes the MABL as a series of uniform layers (e.g., surface layer, mixed layer, entrainment or detrainment zones, etc.). While MAGPIE's core objectives focus on atmospheric flows and fluxes with an emphasis on active remote sensing, aerosol particles and their optical closure were implicitly a core mission element because light scattering by these particles can be used to track atmospheric motion. MAGPIE collaborated across U.S. federal agencies, academic institutions, and the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology (CIMH) and included observations from ground-based aerosol particle samplers and instruments at BACO along with local flights from the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) CIRPAS Twin Otter (CTO) aircraft. Central to the mission was the University of Wisconsin Space Sciences and Engineering Center's (SSEC) High Spectral Resolution Lidar (HSRL; Eloranta et al., 2008). Here, single particle and bulk analyses are used to evaluate how measured dust and sea salt mass concentrations relate to HSRL-derived particulate LDR. In Sect. 2, we provide a brief overview of measurements, and in Sect. 3.1 a timeseries analysis of particle and lidar data, demonstrating nonlinearity between dust and sea salt mass ratios to lidar LDR. In Sect. 3.2 and 3.3, we provide vertically resolved single particle data from the CTO aircraft and ground-based samples, respectively, to help explain the anomalies. In Sect. 4, we provide a discussion and study conclusions.

2.1 Sampling Site and Campaign Overview

Ground-based aerosol particle and lidar measurements were conducted at the BACO site on Ragged Point (13°6′ N, 59°37′ W) for August 2023. Situated at the easternmost point of the Caribbean, BACO offers an optimal location for intercepting long-range transported Saharan dust with minimal interference from local, anthropogenic emissions due to the prevalent Easterly trade winds (Prospero et al., 2021; Gaston et al., 2024; Zuidema et al., 2019). Continuous aerosol particle measurements have been conducted there for over 50 years, providing a unique long-term observational record. The site is equipped with a tower that is 17 m high and is placed atop a 30 m high bluff giving an altitude of ∼ 50 m above sea level. While the measurements are not taken directly at ground level, they are representative of the near surface MABL and are routinely referred to as surface observations in prior Barbados studies (e.g., Zuidema et al., 2019).

MAGPIE leveraged multi-platform measurements including aerosol particles collected at the top of the BACO sampling tower and aboard the CTO aircraft to investigate vertical gradients in aerosol particle chemical and morphological properties. For the 2023 campaign, the focus is centered around the largest dust events of the year observed between 11–18 August 2023. A total of five research flights were conducted during this period, with two samples collected per flight, resulting in ten samples covering a range of altitudes from 30 m to 3 km a.m.s.l.

2.2 Dust Mass Concentration Measurement

Aerosol particles were collected on top of the BACO tower using high-volume samplers with Total Suspended Particulate (TSP) inlets and fitted with cellulose filters (Whatman-41, 20 µm pore size) with a particle size cutoff at 80–100 µm in diameter due to the geometry of the rainhat as described in Royer et al. (2023). Procedural filter blanks were collected every five days and processed alongside the daily filter samples. A quarter of each filter was sequentially extracted three times using a total of 20 mL of Milli-Q water to remove soluble components. Following extraction, the filters were combusted at 500 °C overnight in a muffle furnace. The residual ash mass was weighed and corrected for background contributions by subtracting the ash mass obtained from the procedural blank. The net ash mass was multiplied by a correction factor of 1.3 to account for the loss of any soluble or volatile components during the extraction and combustion process (Prospero, 1999; Zuidema et al., 2019). While some soluble components such as halite may be lost during the extraction process, the applied correction factor of 1.3 is intended to conservatively account for these potential losses, supporting more robust dust mass estimates. Moreover, halite is not a major constituent of Saharan dust, as previous studies report its contribution rarely exceeds 3 % by weight (Scheuvens et al., 2013), making any bias from its loss during the extraction process unlikely to be significant.

2.3 Sea Salt Concentration Measurement

The filtrate collected after dust extraction on the daily filter samples and procedural blanks was then analyzed using ion chromatography (IC; Dionex Integrion HPIC System; Thermo Scientific). The samples were analyzed in triplicate for cations and anions and corrected for procedural blanks. Details of our IC analysis procedure can be found in Royer et al. (2025). Sodium (Na+) is commonly used as a conservative tracer for sea spray particles, therefore, the Na+ concentrations measured by IC analysis were converted to equivalent sea salt concentrations by applying a multiplication factor of 3.252 (Eq. 1) (Gaston et al., 2024; Prospero, 1979).

2.4 In-situ Ground-based Aerosol Optical Measurement

BACO is part of NASA's AErosol RObotic NETwork (AERONET). We used AERONET level 2 aerosol optical depth (AOD at 500 nm) and fine mode AOD (at 500 nm) from the AERONET spectral deconvolution retrieval (O'Neill et al., 2003) to identify the times of dust intrusion during the sampling campaign (Giles et al., 2019; Holben et al., 1998).

2.5 Single-Particle Analysis and Mixing State

Aerosol particle mixing state describes how chemical species are distributed across the particle population (Winkler, 1973; Riemer et al., 2019). Single-particle analysis offers a powerful approach for analyzing this complexity, providing direct insight into the internal composition and variability of individual particles (Reid et al., 2003a; Ault et al., 2014, 2012; Royer et al., 2023; Casuccio et al., 1983; Kim et al., 1987; Andreae et al., 1986; Zhang et al., 2003; Levin et al., 2005; Kandler et al., 2018). We used computer-controlled scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Quanta from Thermo Fisher Scientific, equipped with a FEI Quanta digital field emission gun at 20 kV and 480 pA electron current) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Oxford UltimMax100) (CCSEM/EDX) at the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL) located at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) to characterize single particles. EDX spectra are collected for semi-quantitative analysis of the particle elemental composition, and our analysis focused on 16 elements commonly found in atmospheric aerosol particles: carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), phosphorous (P), sulfur (S), chlorine (Cl), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), vanadium (V), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), and nickel (Ni). This analysis was conducted for particles collected on the BACO tower and aboard the CTO aircraft.

2.5.1 Ground-based Particulate Samples for Single Particle Analysis

Ambient aerosol particles were sampled on top of BACO's 17 m tower using a three-stage cascade impactor (Microanalysis Particle Sampler, MPS-3; California Measurements, Inc.), that separates particles into aerodynamic diameter ranges of 2.5–5.0 µm (stage 1), 0.7–2.5 µm (stage 2), and 0.05–0.7 µm (stage 3). Samples were collected for 30 min at 2 L min−1 each day. Particles were deposited onto carbon-coated copper grids (Ted Pella, Inc.) and analyzed using CCSEM/EDX. No conductive coating (e.g., gold or carbon) was applied to the samples collected on the ground as the conductivity of the copper grid bars minimized possible impacts from charging effects. However, Cu signals from CCSEM/EDX were excluded due to interference from the substrate. In contrast, C films are thin and highly transparent to electrons. Although C signals are present in all spectra due to the support film, the C layer is fine-grained and minimally interferes with particle morphology. Moreover, C together with O, serves as a useful qualitative indicator for identifying organic particles, defined by a combined C + O contribution exceeding 95 %. In this study, N was not used for quantification, nor did we label it in the EDX spectra of particles. Elemental signals were considered valid for further analysis only when exceeding a 2 % threshold composition detected by EDX spectra. Over 1000 individual particles were analyzed per sample. Post-processing of CCSEM/EDX data was conducted using a k-means clustering algorithm (Ault et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2016; Royer et al., 2023) to group particles by similarity in composition and morphology. Clusters were classified into particle types primarily based on semiquantitative elemental composition obtained from EDX analysis, supported by particle size, morphology, and comparison with prior studies. Mineral dust particles were identified by the presence of aluminosilicate elements (Si, Al, and Fe) characteristic of crustal minerals (Hand et al., 2010; Krueger et al., 2004; Levin et al., 2005; Krejci et al., 2005; Denjean et al., 2015). Fe was detected in ∼ 80 % of mineral dust particles at relative area abundances of 10 %–15 %. Sea spray particles were characterized by strong Na and Cl peaks, indicative of halite (NaCl) and confirming their marine origin (Bondy et al., 2018). Aged sea spray particles were identified by Cl depletion accompanied by enrichment in S, consistent with heterogeneous reactions that replace Cl with sulfate or nitrate (Ault et al., 2014; Royer et al., 2023, 2025). Mineral dust particles were observed to be both internally mixed with sea spray and externally mixed (Royer et al., 2023, 2025; Kandler et al., 2018; Harrison et al., 2022; Aryasree et al., 2024). These internally mixed dust and sea spray particles exhibited heterogeneous compositions containing both dust-derived (Si, Al, Fe, Mg) and marine-derived (Na, Cl, Mg) components, with Mg potentially originating from both sources. Organic particles were dominated by C and O (>95 %), with minor inorganic elements, and typically appeared as spherical or gel-like structures. Some displayed Mg-rich shells with sea salt cores, consistent with primary marine organics formed via bubble-bursting at the ocean surface (Ault et al., 2013; Gaston et al., 2011; Chin et al., 1998). Sulfate-rich particles exhibited strong sulfur peaks with accompanying C and O signals, indicative of marine secondary aerosols (e.g., ammonium sulfate or bisulfate) and frequently contained an organic fraction (O'Dowd and de Leeuw, 2007; Royer et al., 2023).

2.5.2 Airborne Particulate Samples for Single Particle Analysis

Aerosol samples were also collected onboard the CTO using an isokinetic inlet and deposited onto isopore membrane filters (47 mm filter, 0.8 µm pore size). An overview of the airborne sampling technique can be found in Sect. S1 in the Supplement. The CTO's primary inlet has an intrinsic 50 % cutpoint of ∼ 3.5 µm in aerodynamic diameter. Due to limitations associated with Teflon filter material, automated computer-controlled SEM was not feasible, and these airborne samples were analyzed manually using SEM/EDX. To prevent particle charging during imaging, filters were sputtered with a gold-coating of 10 nm thickness prior to analysis. A total of 40, 21, and 52 particles from 250 nm to 25 µm diameter were manually analyzed from samples collected within the SAL, above, and below cloud base heights (CBH), respectively, providing a primarily qualitative assessment. The CBH was identified for each flight as the first maximum in profile relative humidity, typically near saturation. Details of airborne sample collection date and times, durations, altitudes, and corresponding CBH are provided in Table S1. Particles were selected randomly across the filter area without targeting specific particle types or sizes to reduce selection bias. All filter handling was performed in a laminar flow hood, and filters were stored individually in sealed Teflon-taped Petri dishes to avoid any contamination. The number of particles analyzed is reported in Table S2 of the Supplement. To quantify statistical uncertainty, we calculated 95 % confidence intervals for the number fraction of each particle class assuming binomial sampling. The major particle types show varying levels of statistical precision. For example, mineral dust is clearly dominant in the SAL (90 ± 9 %) and statistically distinct from mixed dust and sea spray particles, whereas above cloud top and below cloud base, mineral dust and internally mixed dust and sea spray fractions have overlapping confidence intervals, indicating comparable abundance within uncertainty. Thus, while the data robustly supports dust dominance in the SAL, compositional differences among dust and dust mixed with sea spray particle types in the above cloud top and below cloud base should be interpreted qualitatively. Whenever possible, ground-based measurements were coordinated to coincide with periods when the CTO aircraft intercepted the BACO location or its vicinity. Single particle analysis from aircraft sampling, presented in Sect. 3.2, serves as a comparative reference to the more comprehensive in-situ ground-based dataset, which includes ∼ 24 000 analyzed particles. The sulfate and organic particle types were absent in the airborne samples. This is likely due, in part, to the use of isopore filters with a relatively large pore size (0.8 µm), that may have limited the collection efficiency of finer sulfate and organic rich particles.

2.6 High Spectral Resolution Lidar (HSRL)

The SSEC HSRL was deployed during the summer 2023 MAGPIE campaign to characterize the vertical distribution of aerosol particle scattering properties over Ragged Point. The HSRL system used in this study can provide range-resolved profiles of particulate backscatter and depolarization at high spatial and temporal resolution. Details on the SSEC HSRL can be found elsewhere (Razenkov, 2010; Eloranta et al., 2008; Reid et al., 2025). Briefly, the SSEC HSRL operates at a wavelength of 532 nm and separates molecular and particulate backscatter signals using a narrowband iodine absorption filter. This configuration enables accurate, independent retrievals of particulate backscatter (m−1 sr−1) within close proximity to the ocean surface, as well as calibrated extinction (m−1) and extinction-to-backscatter ratio (i.e., the lidar ratio) measurements. The HSRL also contains an elastic backscatter channel of 1064 nm. Long term Raman lidar measurements from the Max Planck Institute (MPI) in Barbados (Weinzierl et al., 2017; Groß et al., 2015; Stevens et al., 2016) provides historical context for aerosol backscatter and depolarization over the island and show structures consistent with the HSRL observations presented here.

For MAGPIE, the SSEC-HSRL was configured to operate in periods of vertical stare, horizontal stare, and vertical scanning from −0.05 to 18°. For the purposes of this paper, we only utilize vertical data. Extraction of light extinction and the lidar ratio within the MABL are performed using the HSRL in one of its side or vertically scanning modes. While a manuscript is under preparation (Fu et al., 2026), for the purpose of this paper we can report from its authors that lidar ratios in the MABL's mixed layer ranged from 15 to 25 sr, and in the SAL was on the order of 35 to 40 sr. Lidar ratios of 15 to 20 sr are consistent with ambient sea salt (RH = 70 % to 85 % near the surface) and 35 to 40 sr above the MABL for “dry” dust in the less humid SAL (RH = 30 % to 50 %).

3.1 Temporal variability in surface-level aerosol particle chemistry, AOD and lidar depolarization ratios (LDR) during a major dust event

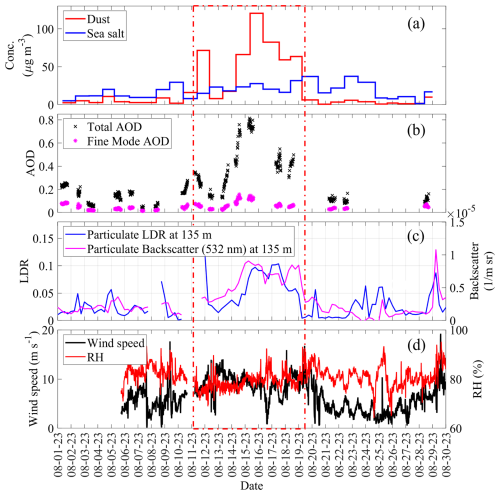

Figure 1 presents a time series of key aerosol properties observed during the August 2023 MAGPIE intensive operations period, including surface-level dust and sea salt mass concentrations, aerosol optical depth (AOD), and HSRL-derived particulate linear depolarization ratio (LDR) and particulate backscatter. Over the month, median dust and sea salt concentrations were 6 ± 32 and 17 ± 9 µg m−3, respectively; the median columnar AOD was 0.15 ± 0.19; and the median LDR at 135 m a.m.s.l. was 0.02 ± 0.03. Notably, a distinct deviation from these baseline values was observed during a period of Saharan dust intrusion occurring between 11 and 18 August 2023. The dust event led to pronounced changes in the chemical composition and physical properties of aerosol particles observed in Barbados, yet the LDR showed little increase. During this period, the dust mass concentration peaked at 120 µg m−3 on 15 August, comparable to the concentration measured during the major “Godzilla” dust event of 2020 (Elliott et al., 2024; Mayol-Bracero et al., 2025), while inferred sea salt concentrations based on sodium were 27 µg m−3, representing an upper-limit estimate given the possible contribution of Na from mineral dust. The average dust-to-sea salt mass ratio was ∼ 3.4 on dusty days (peaking at 4.8), compared to ∼ 0.40 on non-dusty days, indicating a clear dominance of dust in the lower MABL during the dust intrusion event. Total column AOD (500 nm) closely tracked the trend in surface dust mass concentration and peaked at ∼ 0.75 on 15 August, whereas fine mode AOD remained substantially lower (0.12 ± 0.01; Fig. 1b) indicating that the total AOD was predominantly influenced by coarse-mode particles during the dust period. Notably, this event produced one of the highest AOD recorded in Barbados during the month of August over the past decade (Fig. S1).

Figure 1Time series plots for (a) dust and sea salt mass concentrations measured from the top of the BACO tower, (b) AERONET total column and fine mode fraction AODs (at 500 nm), (c) HSRL- particulate linear depolarization ratio (LDR) and particulate backscatter at 532 nm, averaged over six hours, and (d) meteorological measurements (RH and wind speed) during the MAGPIE 2023 campaign. The red dashed box represents the major dust intrusion periods observed during the campaign.

Figure 1c presents the time series of the particulate backscatter and LDR at 135 m a.m.s.l., representing conditions near the surface within the lower MABL for comparison with other ground-based measurements. Although an increase in LDR was observed in the lower MABL during the period of pronounced dust loading, the enhancement was surprisingly small, with values of 0.10 or less (Fig. 1c). The finding can be partially explained through scattering physics (e.g., the lidar equation) governing the lidar signals (Hayman and Spuler, 2017). For MAGPIE, the HSRL lidar ratio (LR), the ratio of aerosol extinction (m−1) to backscatter (m−1 sr−1), was approximately 40 sr for dust and 20 sr for marine aerosols. Because LR is inversely related to the particulate 180° backscatter phase function, a lower LR indicates that marine aerosol particles scatter back approximately twice the amount of energy compared to dust if the marine and dust extinctions are the same. This difference in backscatter directly affects the measured LDR. In a mixed aerosol layer with comparable extinction from dust and marine particles, the backscattered signal, on which the LDR is based, is weighed more strongly toward the marine aerosol contribution (that has a lower LDR).

Given that dust concentrations were approximately four times greater than those of sea salt during the peak of the event, we applied a multiple regression approach to estimate the LDR, using Eq. (2), that incorporated the measured lidar ratio and dust and sea salt concentrations.

where, and represent the parallel components, and and represent the perpendicular components of the particulate backscatter from dust (“d”) and marine aerosol (“m”) particles, respectively.

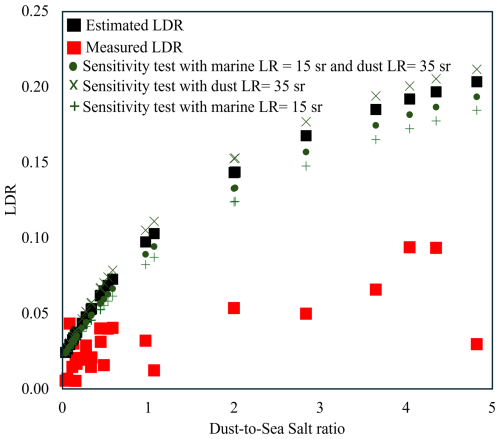

This analysis yielded an estimated LDR of 0.17 ± 0.03 during the dust peak, ∼ 2 times higher than the values observed in Fig. 1c in the lower MABL. Details about this calculation and approximations used to derive this estimate are in Sect. S3 in the Supplement. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the dust-to-sea salt mass concentration ratio versus the measured HSRL-derived LDR and estimated LDR from the multiple regression approach. We note several caveats to our calculation of the estimated LDR. First, the uncertainty associated with our estimated LDR prediction may be larger than the standard deviation reported, as we did not explicitly account for the full-size distribution of sea salt and dust aerosols. In particular, large particles beyond the upper cut point (>80–100 µm) of our bulk dust sampler were not captured. While previous studies have shown that some particles of this size can survive trans-Atlantic transport (e.g., Betzer et al., 1988; Reid et al., 2003a; Barkley et al., 2021), their number concentrations are expected to be substantially lower than those of the particle sizes efficiently collected by the filter sampling used in this study. These coarse particles, which are more efficient at depolarizing incident light due to their irregular shape and size, could contribute significantly to the lidar signal. Their absence from the analysis may lead to an underestimation of the true depolarization potential, especially during intense dust events. Nevertheless, we recognize that other factors may also influence the observed reduction in depolarization. Vertical heterogeneity within the MABL, including overlapping layers of marine and dust aerosols, could further convolute the dust depolarization signal. In addition, inherent limitations in HSRL retrievals, such as signal averaging in optically thin layers or reduced sensitivity near the ocean surface may contribute to the apparent underestimation of LDR.

Figure 2Relationship between the dust-to-sea salt concentration ratio and HSRL-derived particulate LDR at 135 m above ground level during the MAGPIE campaign. Red squares indicate measured LDR values for the full campaign, while black squares represent LDR values estimated from mass concentrations and lidar ratio weighting during the peak dust event. The calculated LDR was approximately a factor of two higher than what was observed during the peak dust event. A sensitivity test was conducted using more conservative lidar ratio values for dust and marine aerosols (shown as green plus, cross and circle symbols), and in all such cases the estimated LDR values remained consistently higher than the measured values.

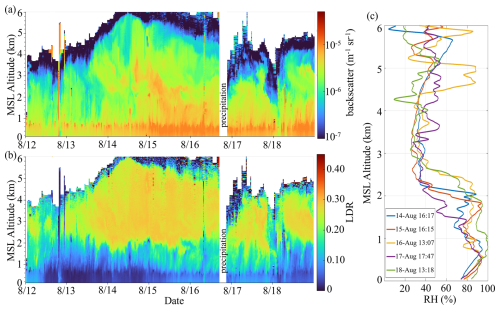

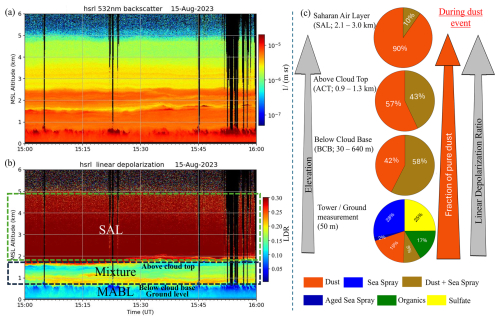

Extending our findings in Fig. 1c vertically, Fig. 3a and b shows the time series of particulate backscatter and LDR measurements from 12–18 August 2023, at altitude up to 6 km a.m.s.l. At ∼ 2–6 km a.m.s.l. above Ragged Point, measurements of increased particulate backscatter (shown in Fig. 3a) are primarily attributable to increased dust loading within the SAL, as indicated by the concurrent elevated LDR of 0.30 (shown in Fig. 3b). This altitude range is consistent with previous studies that have reported the SAL to typically extend from approximately 1.5 to 5.5 km a.m.s.l. (Carlson and Prospero, 1972; Groß et al., 2015; Karyampudi and Carlson, 1988; Reid et al., 2003b; Weinzierl et al., 2017). The particulate backscatter measurement shown in Fig. 3a highlights high aerosol loading near the surface, consistent with the large concentration of marine particles in the lower MABL. Notably, periods of enhanced backscatter between 14–16 August extending downward from the SAL into the MABL suggest episodes of dust downmixing toward the surface, which are also supported by a concurrent increase in surface dust mass concentrations (Fig. 1).

Figure 3HSRL-measurements for (a) particulate backscatter (m−1 sr−1) and (b) particulate linear depolarization ratio (LDR) within 6 km a.m.s.l. for 12–18 August 2023. (c) Vertical profiles of relative humidity (RH, %) up to 6 km a.m.s.l. from radiosonde launches at Ragged Point on representative days between 14 and 18 August 2023. In panels (a) and (b), periods with particulate backscatter <10−7 (m−1 sr−1) are masked out. The uncertainty associated with the particulate LDR measurements shown in panel (b) is provided in Fig. S2.

Figure 3c shows the representative vertical distribution of RH during the dusty period of the study, revealing a distinctly moist MABL characterized by RH values exceeding 80 %. Such elevated humidity levels are conducive to the hygroscopic growth of aerosol particles, which can increase both particle size and sphericity (Titos et al., 2016). These changes in particle properties caused by hygroscopic growth can further enhance particle backscatter while decreasing the LDR which is visible in the particulate backscatter (Fig. 3a) and LDR (Fig. 3b) measurements below cloud base (∼ 700 m). Thus, under humid MABL conditions, both the LR contrast between dust and marine aerosols and hygroscopicity-driven growth can act together to suppress the observed LDR. However, a key consideration is aerosol mixing state as previous observations have shown limited hygroscopic growth of African dust particles, even at high RH, but substantial growth of dust particles that are internally mixed with other aerosol components including sea spray (Denjean et al., 2015).

3.2 Vertical Gradients in the LDR and aerosol mixing state

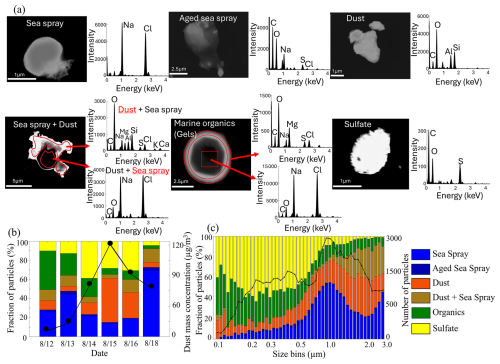

A vertical gradient in aerosol particle mixing state was observed during the Saharan dust intrusion, wherein dust is internally mixed with sea spray at the surface and externally mixed aloft. Single-particle chemical composition and morphology analysis revealed a diverse set of particle types with distinct chemistries and morphologies, including mineral dust, sea spray, aged sea spray, internally mixed mineral dust and sea spray, sulfates, and organics (Royer et al., 2023; Ault et al., 2012, 2014). The Methods section describes the particle classification approach and the particle types identified in this study. Detailed chemical composition of the particle types is presented in Sect. S2 in the Supplement, representative elemental digital color stack plots used for particle classification are shown in Fig. S3, and representative SEM images and corresponding EDX spectra for each particle class are shown in Fig. 4a.

Figure 4(a) Representative aerosol particle types observed in surface samples by SEM images (left) and EDX spectra (right) in samples collected during the MAGPIE campaign. (b) Temporal variations in the number fraction of different particle types during the dust event. (c) Number fractions of different particle types plotted as a function of the particle projected area diameter. The black colored line graph in panels (b) and (c) represents dust mass concentration and number of particles, respectively. These plots are generated from the single particle CCSEM/EDX analysis of the in-situ samples collected at the top of the 17 m tower at BACO.

Our single particle results from ground-based samples share several similarities with, but also important differences from, previous studies of Saharan dust transported to the Caribbean. Consistent with Harrison et al. (2022); Krejci et al. (2005); Denjean et al. (2015) and Reid et al. (2003a) for the Caribbean, the vast majority of dust particles observed at Barbados during MAGPIE were aluminosilicates, confirming the dominance of this mineralogical class in trans-Atlantic Saharan dust. A prominent feature of the MAGPIE observations was the frequent presence of internally mixed dust and sea spray particles, a phenomenon also documented in earlier Caribbean studies (e.g., Reid et al., 2003a; Aryasree et al., 2024; Royer et al., 2025). Kandler et al. (2018) suggested that such mixing likely occurs locally through turbulent interactions between dust and marine aerosol in the MABL. Our observations are consistent with this mechanism and further suggest that cloud processing may enhance this internal mixing. Similar internally mixed dust and sea spray particles have been reported in other coastal regions, particularly during Asian dust outbreaks (Zhang and Iwasaka, 2004; Zhang et al., 2006; Zhang and Iwasaka, 2001; Zhang et al., 2003), indicating that this mixing process is not unique to the Caribbean but may be characteristic of dust outflows across humid marine environments.

Figures 4c and S4 present the average size-resolved chemical composition of ground-level aerosol samples collected during the dust event. A clear compositional shift is observed between submicron and super-micron particles. In the submicron range (particle diameter <1 µm), organic and sulfate aerosol particles were dominant, with median diameters of 0.45 and 0.36 µm, respectively. In contrast, the super-micron size range was dominated by sea spray, mineral dust, and internally mixed dust and sea spray particles. Externally mixed mineral dust collected through our impactor had a number median diameter of ∼ 1.2 µm, while internally mixed dust and sea spray particles exhibited larger median diameters of ∼ 2.0 µm, likely resulting from coagulation and condensation processes occurring during dust descent into the MABL (Kandler et al., 2018). Further, these particles likely become even larger under the high relative humidity (>80 %) conditions of the MABL consistent with hygroscopic growth (Zieger et al., 2017). This morphological evolution in internally mixed dust and sea salt particles would explain, in part, the suppressed LDR during the major dust intrusion event (Bi et al., 2022).

To extend this analysis vertically and examine how particle composition varies with altitude, Fig. 5 presents the vertical profile of the number fractions of aerosol particle types, averaged over the samples taken during dusty days, and HSRL data from 15 August (15:00 UTC), the day when Barbados experienced the highest ground-level dust concentration (∼ 120 µg m−3). The SAL was predominantly composed of mineral dust particles (90 % of the analyzed particles) transported from Northern Africa, and the LDR observed within the SAL (0.30) is attributable to the large fraction of mineral dust present in this layer. Additionally, a transition layer between the SAL and the MABL (labeled as “Mixture” in Fig. 5b) is shown where both sea salt and mineral dust are concurrently present. In the SAL, a fraction of the dust is internally mixed with sea spray particles (10 % of the analyzed particles). Below the SAL, between 0.7 and 1.8 km, LDR values were much smaller and ranged from 0.10 to 0.20, typical for aerosol regimes within the humid MABL where mineral dust particles are mixed with sea spray particles (Gasteiger et al., 2017; Tesche et al., 2011). A comparison of particle composition across altitudes reveals that samples collected above the cloud top contained a slightly higher number fraction of mineral dust (57 %) compared to internally mixed dust and sea spray particles (43 %). In contrast, below the cloud base, this ratio was reversed, with internally mixed dust and sea spray particles making up 58 % of the dust and externally mixed dust 42 % of the dust particles suggesting a dynamic, vertical exchange of particles within the MABL. The MABL circulation pattern through clouds is well documented by lidar observations (e.g., from early studies (Kunkel et al., 1977) to more recent work (Reid et al., 2025)). Such cloud processing mechanisms likely enhance coagulation while turbulent updrafts promote collisions between sea spray and dust particles (Matsuki et al., 2010). The presence of a substantial fraction of internally mixed dust and sea spray particles above and below cloud base is expected, given that sea salt is a dominant contributor to cloud droplets (Crosbie et al., 2022). The number fraction of mineral dust particles increased substantially in the MABL during periods of intense dust intrusion, with a distinct peak observed on 15 August (Fig. 4b). However, particle composition was more variable at the surface compared to aloft, consistent with the proximity to the ocean increasing the presence of marine aerosol particles including sea salts, organics, and sulfates (Fig. 5c). Further, at altitudes below 0.7 km, LDR values were consistently at or below 0.10, commonly taken as being indicative of the dominance of sea spray particles with reduced dust influence (e.g., “Dusty Marine” in the CALIPSO retrievals; Kim et al., 2018).

Figure 5HSRL scan for (a) particulate backscatter at 532 nm and (b) particulate linear depolarization ratio within 6 km a.m.s.l. for 15 August 2023 (15:00 h UTC). (c) Pie charts showing the number concentration (as a percent) of particle types detected from single particle analysis at different altitudes: SAL, above cloud top, below cloud top, and ground-based samples collected atop the BACO tower during the dust event. The altitude range where samples collected for single particle analysis were taken are indicated in parentheses next to each corresponding pie chart. Pie charts show that with increased elevation, the fraction of externally mixed dust increased and the linear depolarization ratio (LDR) from the HSRL measurement increased during the dust event. The RH vertical profile from a radiosonde launched during this HSRL observation period shown in panels (a) and (b) is shown as the orange line in Fig. 3c.

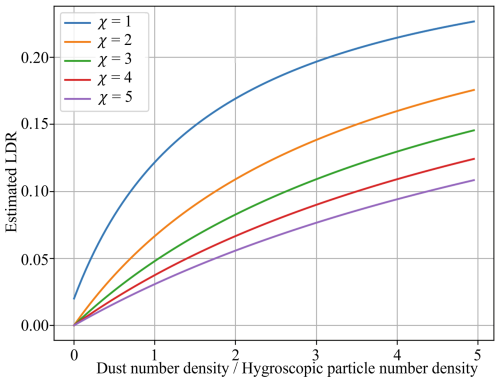

3.3 Accounting for Dust Mixing State and Hygroscopic Growth in Predicting the LDR

Prior work by Denjean et al. (2015) showed that externally mixed African dust did not exhibit hygroscopic growth even at high RH (up to 95 %), whereas appreciable water uptake occurs primarily when dust is internally mixed with sea spray, a particle type that was prominently observed in our single-particle analysis. Thus, we evaluated how the expected LDR changes when RH-dependent optical weighting is explicitly accounted for by applying a hygroscopic extinction enhancement factor to internally mixed dust and sea spray particles. The detailed discussion of this hygroscopicity dependent calculation is provided in Sect. S4 in the Supplement, and the resulting LDR predictions are shown in Fig. 6. The enhancement factor (χ) represents the marine aerosol extinction enhancement due to the increase in the marine particle cross-sectional area with increasing RH (i.e., hygroscopic growth) (Hänel, 1972, 1976). When this enhancement factor is included, the estimated LDR is further suppressed, consistent with our observations that dust in the moist MABL becomes internally mixed and more spherical when hydrated. This refined estimate improves closure between the measured and predicted depolarization ratios suggesting that hygroscopic growth of internally mixed dust and sea spray particles play a central role in reducing the lidar depolarization signal. Further, simulations of light scattering by nonspherical particles and coated particle systems by Bi et al. (2022) showed that mineral dust particles coated by a hydrated, low refractive index shell (e.g., water, sulfate, or sea salt) can exhibit a strongly suppressed depolarization signal, often approaching values characteristic of spherical particles. This occurs because at high RH the hygroscopic shell grows substantially and dominates the optical response, effectively masking the non-sphericity of the underlying dust core. This coated particle behavior could provide a physical basis for our observations in the humid MABL, where internally mixed dust and sea spray particles observed at RH consistently exceeding 80 % produce low LDR values (<0.1) despite high dust mass concentrations and highlights the need to investigate the role of particle composition and mixing state in modulating depolarization signals. Overall, these observations suggest that the reduced LDR values in the MABL are likely explained, in part, by internally mixed dust and hydrated sea spray particles in the presence of high humidity, resulting in hydrated, more spherical and hence less depolarizing particles.

Figure 6Relationship between estimated LDR and dust-to-hygroscopic particle number density ratio as a function of marine aerosol extinction enhancement factor (χ) due to hygroscopic growth. The estimates are based on the observed HSRL-LDR for dry dust particles as 0.3 and LR for dry dust particles as 35 sr and the observed average ratio of cross-sectional area of internally mixed dust and sea spray particles to that of externally mixed dust particles as 2.7, derived from CCSEM/EDX single-particle analysis of surface samples collected at BACO. Cross-sectional areas were calculated using the respective median diameters measured for each particle type.

Single-particle analysis conducted during the MAGPIE campaign revealed that Saharan dust particles in the MABL are physically and chemically distinct from dust within the SAL aloft. Our results show that in the lower, humid MABL, dust becomes internally mixed with sea spray resulting in potentially enhanced hygroscopicity compared to externally mixed dust in agreement with prior studies investigating the hygroscopicity of transported African dust (Denjean et al., 2015). These changes, in part, suppress the dust's depolarization (being more spherical) signal and complicate its identification by lidar. Despite peak dust loading at BACO (AOD ∼ 0.75; surface dust ∼ 120 µg m−3), HSRL observations showed that LDR values in the lower MABL remained mostly below 0.10, a range typically associated with spherical marine aerosols, even though dust concentrations were ∼ 4.8 times higher than sea salt. This discrepancy is further explained by differences in the scattering (lidar ratio) of dust and marine aerosols, where dust backscatters half the energy per extinction cross-section (lidar ratio) compared to marine aerosols which lowers the depolarization measurement. These combined effects of morphological transformation and different lidar ratios reduce the dust signature in depolarization-based retrievals, complicating its detection and quantification near the surface. The resulting underestimation of surface-level dust by lidar-based depolarization retrievals is of particular concern especially during high-dust events like the one observed during this study, where surface particulate matter (PM) exceeded WHO guidelines for PM10 of 45 µg m−3 (World Health Organization, 2021) by a factor of nearly three. Moreover, it may help explain similar discrepancies between lidar observations and in-situ measurements in other regions where dust is modified through interactions with marine aerosols.

More broadly, these results highlight the importance of integrating vertically resolved lidar data with in-situ single-particle analysis and surface aerosol mass concentrations to improve the interpretation of lidar observations in dust-affected regions. Such integrated approaches are essential because LDR is widely used in satellite retrieval algorithms and atmospheric models to estimate dust volume and mass fractions, calculate dust-related radiative forcing, estimate dust contribution to cloud condensation and ice nucleation profiles, estimate dust deposition to receptor ecosystems, and predict surface air quality (Meloni et al., 2018; Haarig et al., 2017; Müller et al., 2010, 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Marinou et al., 2017; Proestakis et al., 2018; Adebiyi et al., 2023; Mahowald et al., 2005). Without such integrated observations, satellite retrievals and forecasting systems may significantly underestimate dust impacts near the surface, where they matter most for air quality and biogeochemical feedback.

While our results demonstrate that single wavelength depolarization can underestimate near surface dust under humid, mixed aerosol conditions, we emphasize that more advanced remote sensing approaches can mitigate these limitations. Multi-wavelength HSRL observations, including backscatter at 532, and 1064 nm and corresponding color ratio and depolarization metrics, provide additional degrees of freedom for discriminating dust from hydrated marine aerosol particles. In fact, recent upgrades by the SSEC HSRL team have produced the first calibrated 1064 nm HSRL system, that is aimed at being deployed in future studies. These multi-spectral measurements would enable color ratio signatures characteristic of dust to be detected even when LDR is low, thereby providing a remote sensing pathway to constrain surface dust loading. Validating these multi-spectral retrievals requires independent constraints on aerosol composition and morphology. The vertically resolved single particle measurements presented here provide validation of how dust properties change as they mix with sea spray. Thus, rather than diminishing the utility of lidar, our results highlight the importance of integrating advanced multi-wavelength lidar products with targeted in-situ observations to improve the accuracy of surface dust estimates in marine environments.

Dust and sea salt mass concentration data and number counts of particle types detected by CCSEM/EDX is publicly available in the University of Miami data repository (https://doi.org/10.17604/1427-0558, Shrestha et al., 2025).

The HSRL data can be accessed through the University of Wisconsin-Madison SSEC repository at https://hsrl.ssec.wisc.edu/by_site/37/bscat/2025/04/ (last access: 8 January 2026).

The NASA AERONET data can be accessed through https://aeronet.gsfc.nasa.gov (last access: 8 January 2026).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-983-2026-supplement.

Conceptualization of this work was done by SS, RJH, JSR, and CJG. JSR posed the initial hypothesis and designed the data collection strategy. Collection of samples was conducted by SS, WJM, ZB, IR, EE, JSR, EB, ADO, RCL, AA, DB, EAR, JRP, AB, RY, QW, TE, EL, MLP, and CJG, while analysis was done by SS, HEE, NNL, ZC, SC, and RA. The development of method used in this work was done by SS, REH, WJM, EE, JSR, and CJG. Instrumentation used to conduct this work was provided by REH, SC, MLP, and CJG. Formal analysis of data was performed by SS, WJM, and JSR. EE performed the optical calculations of expected LDR. Validation of data products was performed by SS, RJH, WJM, JSR, AA, and CJG. Data visualization was performed by SS. Supervision and project administration duties were done by RJH, JSR, and CJG. SS wrote the original draft for publication, and all the co-authors reviewed and edited this work.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank the family of HC Manning and the Herbert C Manning Trust for providing access to their land at Ragged Point in Barbados. We thank Jeremy Bougoure at EMSL for his help with the Au sputter coating of our filter samples. We thank Dr. Konrad Kandler and the other reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments, which substantially improved the clarity and rigor of this manuscript.

CJG and SS acknowledge the Office of Naval Research (ONR) grants N00014-23-1-2861 and N000142512003 and NSF MRI grant 2215875. A portion of this research was performed on project awards (https://doi.org/10.46936/lser.proj.2021.51900/60000361 and https://doi.org/10.46936/ltds.proj.2023.61072/60012372) from the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Biological and Environmental Research program. REH, WJM, ZB, IR and EE were supported under ONR grant N000142412736 and N00014-21-1-2130. JSR and EAR were supported under ONR grant O2507-017-017-112205. AB was supported under ONR grant N0001423WX01787. QW, JRP and RY were supported under ONR grant N0001424WX02429. APA acknowledges support from ONR grant N000142512003 and DOE grant DE-SC0025196.

This paper was edited by Mingjin Tang and reviewed by Konrad Kandler, Wenshuai Li, Yang Zhou, and three anonymous referees.

Adams, A. M., Prospero, J. M., and Zhang, C.: CALIPSO-Derived Three-Dimensional Structure of Aerosol over the Atlantic Basin and Adjacent Continents, J. Clim., 25, 6862–6879, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00672.1, 2012.

Adebiyi, A., Kok, J. F., Murray, B. J., Ryder, C. L., Stuut, J.-B. W., Kahn, R. A., Knippertz, P., Formenti, P., Mahowald, N. M., Pérez García-Pando, C., Klose, M., Ansmann, A., Samset, B. H., Ito, A., Balkanski, Y., Di Biagio, C., Romanias, M. N., Huang, Y., and Meng, J.: A review of coarse mineral dust in the Earth system, Aeolian Res., 60, 100849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2022.100849, 2023.

Andreae, M. O., Charlson, R. J., Bruynseels, F., Storms, H., Van Grieken, R., and Maenhaut, W.: Internal Mixture of Sea Salt, Silicates, and Excess Sulfate in Marine Aerosols, Science, 232, 1620–1623, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.232.4758.1620, 1986.

Ansmann, A., Seifert, P., Tesche, M., and Wandinger, U.: Profiling of fine and coarse particle mass: case studies of Saharan dust and Eyjafjallajökull/Grimsvötn volcanic plumes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 9399–9415, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-9399-2012, 2012.

Aryasree, S., Kandler, K., Benker, N., Walser, A., Tipka, A., Dollner, M., Seibert, P., and Weinzierl, B.: Vertical Variability in morphology, chemistry and optical properties of the transported Saharan air layer measured from Cape Verde and the Caribbean, R. Soc. Open Sci., 11, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.231433, 2024.

Ault, A. P., Peters, T. M., Sawvel, E. J., Casuccio, G. S., Willis, R. D., Norris, G. A., and Grassian, V. H.: Single-Particle SEM-EDX Analysis of Iron-Containing Coarse Particulate Matter in an Urban Environment: Sources and Distribution of Iron within Cleveland, Ohio, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 4331–4339, https://doi.org/10.1021/es204006k, 2012.

Ault, A. P., Guasco, T. L., Ryder, O. S., Baltrusaitis, J., Cuadra-Rodriguez, L. A., Collins, D. B., Ruppel, M. J., Bertram, T. H., Prather, K. A., and Grassian, V. H.: Inside versus Outside: Ion Redistribution in Nitric Acid Reacted Sea Spray Aerosol Particles as Determined by Single Particle Analysis, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 135, 14528–14531, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja407117x, 2013.

Ault, A. P., Guasco, T. L., Baltrusaitis, J., Ryder, O. S., Trueblood, J. V., Collins, D. B., Ruppel, M. J., Cuadra-Rodriguez, L. A., Prather, K. A., and Grassian, V. H.: Heterogeneous Reactivity of Nitric Acid with Nascent Sea Spray Aerosol: Large Differences Observed between and within Individual Particles, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 5, 2493–2500, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz5008802, 2014.

Barkley, A. E., Olson, N. E., Prospero, J. M., Gatineau, A., Panechou, K., Maynard, N. G., Blackwelder, P., China, S., Ault, A. P., and Gaston, C. J.: Atmospheric Transport of North African Dust-Bearing Supermicron Freshwater Diatoms to South America: Implications for Iron Transport to the Equatorial North Atlantic Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL090476, 2021.

Betzer, P. R., Carder, K. L., Duce, R. A., Merrill, J. T., Tindale, N. W., Uematsu, M., Costello, D. K., Young, R. W., Feely, R. A., Breland, J. A., Bernstein, R. E., and Greco, A. M.: Long–range transport of giant mineral aerosol particles, Nature, 336, 568–571, https://doi.org/10.1038/336568a0, 1988.

Bi, L., Wang, Z., Han, W., Li, W., and Zhang, X.: Computation of Optical Properties of Core-Shell Super-Spheroids Using a GPU Implementation of the Invariant Imbedding T-Matrix Method, Front. Remote Sens., 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/frsen.2022.903312, 2022.

Bondy, A. L., Bonanno, D., Moffet, R. C., Wang, B., Laskin, A., and Ault, A. P.: The diverse chemical mixing state of aerosol particles in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 12595–12612, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-12595-2018, 2018.

Burton, S. P., Ferrare, R. A., Hostetler, C. A., Hair, J. W., Rogers, R. R., Obland, M. D., Butler, C. F., Cook, A. L., Harper, D. B., and Froyd, K. D.: Aerosol classification using airborne High Spectral Resolution Lidar measurements – methodology and examples, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 5, 73–98, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-5-73-2012, 2012.

Burton, S. P., Hair, J. W., Kahnert, M., Ferrare, R. A., Hostetler, C. A., Cook, A. L., Harper, D. B., Berkoff, T. A., Seaman, S. T., Collins, J. E., Fenn, M. A., and Rogers, R. R.: Observations of the spectral dependence of linear particle depolarization ratio of aerosols using NASA Langley airborne High Spectral Resolution Lidar, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 13453–13473, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-13453-2015, 2015.

Carlson, T. N. and Prospero, J. M.: The Large-Scale Movement of Saharan Air Outbreaks over the Northern Equatorial Atlantic, J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim., 11, 283–297, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1972)011<0283:TLSMOS>2.0.CO;2, 1972.

Casuccio, G. S., Janocko, P. B., Lee, R. J., Kelly, J. F., Dattner, S. L., and Mgebroff, J. S.: The Use of Computer Controlled Scanning Electron Microscopy in Environmental Studies, J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc., 33, 937–943, https://doi.org/10.1080/00022470.1983.10465674, 1983.

Chin, W.-C., Orellana, M. V., and Verdugo, P.: Spontaneous assembly of marine dissolved organic matter into polymer gels, Nature, 391, 568–572, https://doi.org/10.1038/35345, 1998.

Crosbie, E., Ziemba, L. D., Shook, M. A., Robinson, C. E., Winstead, E. L., Thornhill, K. L., Braun, R. A., MacDonald, A. B., Stahl, C., Sorooshian, A., van den Heever, S. C., DiGangi, J. P., Diskin, G. S., Woods, S., Bañaga, P., Brown, M. D., Gallo, F., Hilario, M. R. A., Jordan, C. E., Leung, G. R., Moore, R. H., Sanchez, K. J., Shingler, T. J., and Wiggins, E. B.: Measurement report: Closure analysis of aerosol–cloud composition in tropical maritime warm convection, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 13269–13302, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-13269-2022, 2022.

Denjean, C., Caquineau, S., Desboeufs, K., Laurent, B., Maille, M., Quiñones Rosado, M., Vallejo, P., Mayol-Bracero, O. L., and Formenti, P.: Long-range transport across the Atlantic in summertime does not enhance the hygroscopicity of African mineral dust, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 7835–7843, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL065693, 2015.

Elliott, H. E., Popendorf, K. J., Blades, E., Royer, H. M., Pollier, C. G. L., Oehlert, A. M., Kukkadapu, R., Ault, A., and Gaston, C. J.: Godzilla mineral dust and La Soufrière volcanic ash fallout immediately stimulate marine microbial phosphate uptake, Front. Mar. Sci., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1308689, 2024.

Eloranta, E. W., Razenkov, I. A., Hedrick, J., and Garcia, J. P.: The design and construction of an airborne high spectral resolution lidar, in: IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings, https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO.2008.4526390, 2008.

Freudenthaler, V., Esselborn, M., Wiegner, M., Heese, B., Tesche, M., Ansmann, A., Müller, D., Althausen, D., Wirth, M., Fix, A., Ehret, G., Knippertz, P., Toledano, C., Gasteiger, J., Garhammer, M., and Seefeldner, M.: Depolarization ratio profiling at several wavelengths in pure Saharan dust during SAMUM 2006, Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol., 61, 165, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2008.00396.x, 2009.

Fu, D., Marais, W. J., Razenkov, I., Buckholtz, Z., Gaston, C. J., Eloranta, E. W., Reid, J. S., and Holz, R. E.: Retrieving Multi-Year Dust and Marine Boundary Layer Vertically Resolved Lidar Ratio and Extinction Measurements over Barbados Using Scanning High Spectral Resolution Lidar, in preparation, 2026.

Gasteiger, J., Groß, S., Sauer, D., Haarig, M., Ansmann, A., and Weinzierl, B.: Particle settling and vertical mixing in the Saharan Air Layer as seen from an integrated model, lidar, and in situ perspective, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 297–311, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-297-2017, 2017.

Gaston, C. J., Furutani, H., Guazzotti, S. A., Coffee, K. R., Bates, T. S., Quinn, P. K., Aluwihare, L. I., Mitchell, B. G., and Prather, K. A.: Unique ocean-derived particles serve as a proxy for changes in ocean chemistry, J. Geophys. Res., 116, D18310, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD015289, 2011.

Gaston, C. J., Prospero, J. M., Foley, K., Pye, H. O. T., Custals, L., Blades, E., Sealy, P., and Christie, J. A.: Diverging trends in aerosol sulfate and nitrate measured in the remote North Atlantic in Barbados are attributed to clean air policies, African smoke, and anthropogenic emissions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 8049–8066, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-8049-2024, 2024.

Giles, D. M., Sinyuk, A., Sorokin, M. G., Schafer, J. S., Smirnov, A., Slutsker, I., Eck, T. F., Holben, B. N., Lewis, J. R., Campbell, J. R., Welton, E. J., Korkin, S. V., and Lyapustin, A. I.: Advancements in the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) Version 3 database – automated near-real-time quality control algorithm with improved cloud screening for Sun photometer aerosol optical depth (AOD) measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 169–209, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-169-2019, 2019.

Groß, S., Freudenthaler, V., Schepanski, K., Toledano, C., Schäfler, A., Ansmann, A., and Weinzierl, B.: Optical properties of long-range transported Saharan dust over Barbados as measured by dual-wavelength depolarization Raman lidar measurements, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 11067–11080, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-11067-2015, 2015.

Groß, S., Gasteiger, J., Freudenthaler, V., Müller, T., Sauer, D., Toledano, C., and Ansmann, A.: Saharan dust contribution to the Caribbean summertime boundary layer – a lidar study during SALTRACE, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11535–11546, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11535-2016, 2016.

Haarig, M., Ansmann, A., Althausen, D., Klepel, A., Groß, S., Freudenthaler, V., Toledano, C., Mamouri, R.-E., Farrell, D. A., Prescod, D. A., Marinou, E., Burton, S. P., Gasteiger, J., Engelmann, R., and Baars, H.: Triple-wavelength depolarization-ratio profiling of Saharan dust over Barbados during SALTRACE in 2013 and 2014, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 10767–10794, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-10767-2017, 2017.

Hand, V. L., Capes, G., Vaughan, D. J., Formenti, P., Haywood, J. M., and Coe, H.: Evidence of internal mixing of African dust and biomass burning particles by individual particle analysis using electron beam techniques, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012938, 2010.

Hänel, G.: Computation of the extinction of visible radiation by atmospheric aerosol particles as a function of the relative humidity, based upon measured properties, J. Aerosol Sci., 3, 377–386, https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-8502(72)90092-4, 1972.

Hänel, G.: The Single-Scattering Albedo of Atmospheric Aerosol Particles as a Function of Relative Humidity, J. Atmos. Sci., 33, 1120–1124, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1976)033<1120:TSSAOA>2.0.CO;2, 1976.

Harrison, A. D., O'Sullivan, D., Adams, M. P., Porter, G. C. E., Blades, E., Brathwaite, C., Chewitt-Lucas, R., Gaston, C., Hawker, R., Krüger, O. O., Neve, L., Pöhlker, M. L., Pöhlker, C., Pöschl, U., Sanchez-Marroquin, A., Sealy, A., Sealy, P., Tarn, M. D., Whitehall, S., McQuaid, J. B., Carslaw, K. S., Prospero, J. M., and Murray, B. J.: The ice-nucleating activity of African mineral dust in the Caribbean boundary layer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 9663–9680, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-9663-2022, 2022.

Hayman, M. and Spuler, S.: Demonstration of a diode-laser-based high spectral resolution lidar (HSRL) for quantitative profiling of clouds and aerosols, Opt. Express, 25, A1096, https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.0A1096, 2017.

Holben, B. N., Eck, T. F., Slutsker, I., Tanré, D., Buis, J. P., Setzer, A., Vermote, E., Reagan, J. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Nakajima, T., Lavenu, F., Jankowiak, I., and Smirnov, A.: AERONET – A Federated Instrument Network and Data Archive for Aerosol Characterization, Remote Sens. Environ., 66, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(98)00031-5, 1998.

Huang, X., Yang, P., Kattawar, G., and Liou, K.-N.: Effect of mineral dust aerosol aspect ratio on polarized reflectance, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 151, 97–109, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2014.09.014, 2015.

Kalashnikova, O. V., Garay, M. J., Martonchik, J. V., and Diner, D. J.: MISR Dark Water aerosol retrievals: operational algorithm sensitivity to particle non-sphericity, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 6, 2131–2154, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-6-2131-2013, 2013.

Kandler, K., Schneiders, K., Ebert, M., Hartmann, M., Weinbruch, S., Prass, M., and Pöhlker, C.: Composition and mixing state of atmospheric aerosols determined by electron microscopy: method development and application to aged Saharan dust deposition in the Caribbean boundary layer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 13429–13455, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-13429-2018, 2018.

Karyampudi, V. M. and Carlson, T. N.: Analysis and Numerical Simulations of the Saharan Air Layer and Its Effect on Easterly Wave Disturbances, J. Atmos. Sci., 45, 3102–3136, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1988)045<3102:AANSOT>2.0.CO;2, 1988.

Karyampudi, V. M., Palm, S. P., Reagen, J. A., Fang, H., Grant, W. B., Hoff, R. M., Moulin, C., Pierce, H. F., Torres, O., Browell, E. V., and Melfi, S. H.: Validation of the Saharan Dust Plume Conceptual Model Using Lidar, Meteosat, and ECMWF Data, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 80, 1045–1075, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1999)080<1045:VOTSDP>2.0.CO;2, 1999.

Kim, D. S., Hopke, P. K., Massart, D. L., Kaufman, L., and Casuccio, G. S.: Multivariate analysis of CCSEM auto emission data, Sci. Total Environ., 59, 141–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(87)90438-4, 1987.

Kim, M.-H., Omar, A. H., Tackett, J. L., Vaughan, M. A., Winker, D. M., Trepte, C. R., Hu, Y., Liu, Z., Poole, L. R., Pitts, M. C., Kar, J., and Magill, B. E.: The CALIPSO version 4 automated aerosol classification and lidar ratio selection algorithm, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 6107–6135, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-6107-2018, 2018.

Koehler, K. A., Kreidenweis, S. M., DeMott, P. J., Prenni, A. J., and Petters, M. D.: Potential impact of Owens (dry) Lake dust on warm and cold cloud formation, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 112, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008413, 2007.

Kong, S., Sato, K., and Bi, L.: Lidar Ratio–Depolarization Ratio Relations of Atmospheric Dust Aerosols: The Super-Spheroid Model and High Spectral Resolution Lidar Observations, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 127, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035629, 2022.

Krejci, R., Ström, J., de Reus, M., and Sahle, W.: Single particle analysis of the accumulation mode aerosol over the northeast Amazonian tropical rain forest, Surinam, South America, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 3331–3344, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-3331-2005, 2005.

Krueger, B. J., Grassian, V. H., Cowin, J. P., and Laskin, A.: Heterogeneous chemistry of individual mineral dust particles from different dust source regions: the importance of particle mineralogy, Atmos. Environ., 38, 6253–6261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.07.010, 2004.

Kunkel, K. E., Eloranta, E. W., and Shipley, S. T.: Lidar Observations of the Convective Boundary Layer, J. Appl. Meteorol., 16, 1306–1311, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1977)016<1306:LOOTCB>2.0.CO;2, 1977.

Levin, Z., Teller, A., Ganor, E., and Yin, Y.: On the interactions of mineral dust, sea-salt particles, and clouds: A measurement and modeling study from the Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment campaign, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 110, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD005810, 2005.

Li, C., Li, J., Dubovik, O., Zeng, Z.-C., and Yung, Y. L.: Impact of Aerosol Vertical Distribution on Aerosol Optical Depth Retrieval from Passive Satellite Sensors, Remote Sens., 12, 1524, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12091524, 2020.

Li-Jones, X., Maring, H. B., and Prospero, J. M.: Effect of relative humidity on light scattering by mineral dust aerosol as measured in the marine boundary layer over the tropical Atlantic Ocean, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 103, 31113–31121, https://doi.org/10.1029/98JD01800, 1998.

Mahowald, N. M., Baker, A. R., Bergametti, G., Brooks, N., Duce, R. A., Jickells, T. D., Kubilay, N., Prospero, J. M., and Tegen, I.: Atmospheric global dust cycle and iron inputs to the ocean, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 19, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GB002402, 2005.

Marinou, E., Amiridis, V., Binietoglou, I., Tsikerdekis, A., Solomos, S., Proestakis, E., Konsta, D., Papagiannopoulos, N., Tsekeri, A., Vlastou, G., Zanis, P., Balis, D., Wandinger, U., and Ansmann, A.: Three-dimensional evolution of Saharan dust transport towards Europe based on a 9-year EARLINET-optimized CALIPSO dataset, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 5893–5919, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-5893-2017, 2017.

Matsuki, A., Schwarzenboeck, A., Venzac, H., Laj, P., Crumeyrolle, S., and Gomes, L.: Cloud processing of mineral dust: direct comparison of cloud residual and clear sky particles during AMMA aircraft campaign in summer 2006, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 1057–1069, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-1057-2010, 2010.

Mayol-Bracero, O. L., Prospero, J. M., Sarangi, B., Andrews, E., Colarco, P. R., Cuevas, E., Di Girolamo, L., Garcia, R. D., Gaston, C., Holben, B., Ladino, L. A., León, P., Losno, R., Martínez, O., Martínez-Huertas, B. L., Méndez-Lázaro, P., Molinie, J., Muller-Karger, F., Otis, D., Raga, G., Reyes, A., Rosas Nava, J., Rosas, D., Sealy, A., Serikov, I., Tong, D., Torres-Delgado, E., Yu, H., and Zuidema, P.: “Godzilla,” the Extreme African Dust Event of June 2020: Origins, Transport, and Impact on Air Quality in the Greater Caribbean Basin, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 106, E1620–E1648, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-24-0045.1, 2025.

Mehra, M., Shrestha, S., AP, K., Guagenti, M., Moffett, C. E., VerPloeg, S. G., Coogan, M. A., Rai, M., Kumar, R., Andrews, E., Sherman, J. P., Flynn III, J. H., Usenko, S., and Sheesley, R. J.: Atmospheric heating in the US from saharan dust: Tracking the June 2020 event with surface and satellite observations, Atmos. Environ., 310, 119988, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119988, 2023.

Meloni, D., di Sarra, A., Brogniez, G., Denjean, C., De Silvestri, L., Di Iorio, T., Formenti, P., Gómez-Amo, J. L., Gröbner, J., Kouremeti, N., Liuzzi, G., Mallet, M., Pace, G., and Sferlazzo, D. M.: Determining the infrared radiative effects of Saharan dust: a radiative transfer modelling study based on vertically resolved measurements at Lampedusa, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 4377–4401, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-4377-2018, 2018.

Moustaka, A., Kazadzis, S., Proestakis, E., Lopatin, A., Dubovik, O., Tourpali, K., Zerefos, C., Amiridis, V., and Gkikas, A.: Enhancing dust aerosols monitoring capabilities across North Africa and the Middle East using the A-Train satellite constellation, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-888, 2025.

Müller, D., Weinzierl, B., Petzold, A., Kandler, K., Ansmann, A., Müller, T., Tesche, M., Freudenthaler, V., Esselborn, M., Heese, B., Althausen, D., Schladitz, A., Otto, S., and Knippertz, P.: Mineral dust observed with AERONET Sun photometer, Raman lidar, and in situ instruments during SAMUM 2006: Shape-independent particle properties, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 115, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012520, 2010.

Müller, D., Lee, K. -H., Gasteiger, J., Tesche, M., Weinzierl, B., Kandler, K., Müller, T., Toledano, C., Otto, S., Althausen, D., and Ansmann, A.: Comparison of optical and microphysical properties of pure Saharan mineral dust observed with AERONET Sun photometer, Raman lidar, and in situ instruments during SAMUM 2006, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016825, 2012.

Murayama, T., Okamoto, H., Kaneyasu, N., Kamataki, H., and Miura, K.: Application of Lidar Depolarization Measurement in the Atmospheric Boundary Layer: Effects of Dust and Sea‐salt Particles, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 104, 31781–31792, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900503, 1999.

O'Dowd, C. D. and de Leeuw, G.: Marine aerosol production: a review of the current knowledge, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 365, 1753–1774, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2007.2043, 2007.

O'Neill, N. T., Eck, T. F., Smirnov, A., Holben, B. N., and Thulasiraman, S.: Spectral discrimination of coarse and fine mode optical depth, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002975, 2003.

Orozco, D., Beyersdorf, A. J., Ziemba, L. D., Berkoff, T., Zhang, Q., Delgado, R., Hennigan, C. J., Thornhill, K. L., Young, D. E., Parworth, C., Kim, H., and Hoff, R. M.: Hygrosopicity measurements of aerosol particles in the San Joaquin Valley, CA, Baltimore, MD, and Golden, CO, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 121, 7344–7359, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023971, 2016.

Proestakis, E., Amiridis, V., Marinou, E., Georgoulias, A. K., Solomos, S., Kazadzis, S., Chimot, J., Che, H., Alexandri, G., Binietoglou, I., Daskalopoulou, V., Kourtidis, K. A., de Leeuw, G., and van der A, R. J.: Nine-year spatial and temporal evolution of desert dust aerosols over South and East Asia as revealed by CALIOP, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 1337–1362, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-1337-2018, 2018.

Prospero, J. M.: Mineral and sea salt aerosol concentrations in various ocean regions, J. Geophys. Res. Ocean., 84, 725–731, https://doi.org/10.1029/JC084iC02p00725, 1979.

Prospero, J. M.: Long-term measurements of the transport of African mineral dust to the southeastern United States: Implications for regional air quality, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 104, 15917–15927, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900072, 1999.

Prospero, J. M., Delany, A. C., Delany, A. C., and Carlson, T. N.: The Discovery of African Dust Transport to the Western Hemisphere and the Saharan Air Layer: A History, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102, E1239–E1260, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0309.1, 2021.

Razenkov, I.: Characterization of a Geiger-Mode Avalanche Photodiode Detector for High Special Resolution Lidar, University of Wisconsin – Madison, https://radiance.ssec.wisc.edu/papers/ilya_thes/Ilya_Razenkov_Master_thesis_231209.pdf (last access: 8 January 2026), 2010.

Reid, E. A., Reid, J. S., Meier, M. M., Dunlap, M. R., Cliff, S. S., Broumas, A., Perry, K., and Maring, H.: Characterization of African dust transported to Puerto Rico by individual particle and size segregated bulk analysis, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002935, 2003a.

Reid, J. S., Jonsson, H. H., Maring, H. B., Smirnov, A., Savoie, D. L., Cliff, S. S., Reid, E. A., Livingston, J. M., Meier, M. M., Dubovik, O., and Tsay, S.: Comparison of size and morphological measurements of coarse mode dust particles from Africa, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 108, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002485, 2003b.

Reid, J. S., Holz, R. E., Hostetler, C. A., Ferrare, R. A., Rubin, J. I., Thompson, E. J., van den Heever, S. C., Amiot, C. G., Burton, S. P., DiGangi, J. P., Diskin, G. S., Cossuth, J. H., Eleuterio, D. P., Eloranta, E. W., Kuehn, R., Marais, W. J., Maring, H. B., Sorooshian, A., Thornhill, K. L., Trepte, C. R., Wang, J., Xian, P., and Ziemba, L. D.: PISTON and CAMP2Ex observations of the fundamental modes of aerosol vertical variability in the Northwest Tropical Pacific and Maritime Continent's Monsoon, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 18639–18673, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-18639-2025, 2025.

Riemer, N., Ault, A. P., West, M., Craig, R. L., and Curtis, J. H.: Aerosol Mixing State: Measurements, Modeling, and Impacts, Rev. Geophys., 57, 187–249, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018RG000615, 2019.

Royer, H. M., Pöhlker, M. L., Krüger, O., Blades, E., Sealy, P., Lata, N. N., Cheng, Z., China, S., Ault, A. P., Quinn, P. K., Zuidema, P., Pöhlker, C., Pöschl, U., Andreae, M., and Gaston, C. J.: African smoke particles act as cloud condensation nuclei in the wintertime tropical North Atlantic boundary layer over Barbados, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 981–998, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-981-2023, 2023.

Royer, H. M., Sheridan, M. T., Elliott, H. E., Blades, E., Lata, N. N., Cheng, Z., China, S., Zhu, Z., Ault, A. P., and Gaston, C. J.: African dust transported to Barbados in the wintertime lacks indicators of chemical aging, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 5743–5759, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-5743-2025, 2025.

Sakai, T., Nagai, T., Zaizen, Y., and Mano, Y.: Backscattering Linear Depolarization Ratio Measurements of Mineral, Sea-Salt, and Ammonium Sulfate Particles Simulated in a Laboratory Chamber, Appl. Opt., 49, 4441, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.49.004441, 2010.

Scheuvens, D., Schütz, L., Kandler, K., Ebert, M., and Weinbruch, S.: Bulk composition of northern African dust and its source sediments – A compilation, Earth-Science Rev., 116, 170–194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2012.08.005, 2013.

Shen, H., Peters, T. M., Casuccio, G. S., Lersch, T. L., West, R. R., Kumar, A., Kumar, N., and Ault, A. P.: Elevated Concentrations of Lead in Particulate Matter on the Neighborhood-Scale in Delhi, India As Determined by Single Particle Analysis, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 4961–4970, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b06202, 2016.

Shrestha, S., Holz, R. E., Marais, W. J., Buckholtz, Z., Razenkov, I., Eloranta, E., Reid, J. S., Elliott, H. E., Lata, N. N., Cheng, Z., China, S., Blades, E., Ortiz, A., Chewitt-Lucas, R., Allen, A., Blades, D., Agrawal, R., Reid, E. A., Ruiz-Plancarte, J., Bucholtz, A., Yamaguchi, R., Wang, Q., Eck, T., Lind, E., Pöhlker, M. L., Ault, A., and Gaston, C. J.: Bulk Dust and Sea Salt mass concentration, and CCSEM/EDX Particle Types Data from Barbados during MAGPIE 2023, University of Miami Libraries [data set], https://doi.org/10.17604/1427-0558, 2025.

Stevens, B., Farrell, D., Hirsch, L., Jansen, F., Nuijens, L., Serikov, I., Brügmann, B., Forde, M., Linne, H., Lonitz, K., and Prospero, J. M.: The Barbados Cloud Observatory: Anchoring Investigations of Clouds and Circulation on the Edge of the ITCZ, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 97, 787–801, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00247.1, 2016.

Tesche, M., Müller, D., Gross, S., Ansmann, A., Althausen, D., Freudenthaler, V., Weinzierl, B., Veira, A., and Petzold, A.: Optical and microphysical properties of smoke over Cape Verde inferred from multiwavelength lidar measurements, Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol., 63, 677, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2011.00549.x, 2011.

Titos, G., Cazorla, A., Zieger, P., Andrews, E., Lyamani, H., Granados-Muñoz, M. J., Olmo, F. J., and Alados-Arboledas, L.: Effect of hygroscopic growth on the aerosol light-scattering coefficient: A review of measurements, techniques and error sources, Atmos. Environ., 141, 494–507, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.07.021, 2016.