the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Formation of organic sulfur compounds through SO2-initiated photochemistry of PAHs and dimethylsulfoxide at the air-water interface

Haoyu Jiang

Yingyao He

Yiqun Wang

Sheng Li

Bin Jiang

Luca Carena

Xue Li

Lihua Yang

Tiangang Luan

Davide Vione

The presence of organic sulfur compounds (OS) at the water surface acting as organic surfactants, may influence the air-water interaction and contribute to new particle formation in the atmosphere. However, the impact of ubiquitous anthropogenic pollutant emissions, such as SO2 and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) on the formation of OS at the air-water interface still remains unknown. Here, we observe large amounts of OS formation in the presence of SO2, upon irradiation of aqueous solutions containing typical PAHs, such as pyrene (PYR), fluoranthene (FLA), and phenanthrene (PHE) as well as dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). We observe rapid formation of several gaseous OSs from light-induced heterogeneous reactions of SO2 with either DMSO or a mixture of PAHs and DMSO (PAHs/DMSO), and some of these OSs (e.g. methanesulfonic acid) are well established secondary organic aerosol (SOA) precursors. A myriad of OSs and unsaturated compounds are produced and detected in the aqueous phase. The tentative reaction pathways are supported by theoretical calculations of the Gibbs energy of reactions. Our findings provide new insights into potential sources and formation pathways of OSs occurring at the water (sea, lake, river) surface, that should be considered in future model studies for a better representation of the air-water interaction and SOA formation processes.

- Article

(1897 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1917 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Organic sulfur compounds (OSs) are ubiquitous in atmospheric aerosols, and organosulfates are considered as important tracers of secondary organic aerosols (SOA). Based on the occurrence of hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties in the same molecule, OSs are surface-active compounds that cause reduction of surface tension and enhance the formation potential of cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) in aerosol particles (Bruggemann et al., 2020).

Both biogenic and anthropogenic sources, such as biomass and fossil fuel burning release OSs into the atmosphere (Bruggemann et al., 2020). The contribution of aromatic organosulfates could be up to two thirds of the sum of the identified OSs (Riva et al., 2015, 2016), and their input is highest during winter (Ma et al., 2014). Although some aromatic organosulfates have similar chemical structures as those of potential aromatic precursors of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as toluene and xylene (Kundu et al., 2013), monocyclic aromatics were not regarded as aromatic organosulfate precursors because they are more inclined to oxidize into ring opening products (Staudt et al., 2014; Kamens et al., 2011). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), such as naphthalene (NAP) and 2-methylnaphthalene (2-MeNAP) have rather been postulated as the precursors of aromatic OSs (Riva et al., 2015; Staudt et al., 2014).

Among all aromatic compounds, PAHs are ubiquitous organic compounds enriched at both the sea and freshwater (lakes, river) surface (Cincinelli et al., 2001; Vácha et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2006; Lohmann et al., 2009; Seidel et al., 2017), where they can reach even 200–400 times higher concentrations compared to the water bulk (Cincinelli et al., 2001; Vácha et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2006; Lohmann et al., 2009; Seidel et al., 2017; Hardy et al., 1990). The origin of PAHs accumulated at the water surface stems from combustion processes, such as biomass burning, coal-based and petroleum-based combustion (Lammel, 2015). At the surface of freshwater and seawater, the PAHs concentrations vary from 11.84 to 393.12 ng L−1 (J. Li et al., 2017), and from 5 to ∼ 1900 ng L−1, respectively (Valavanidis et al., 2008; Otto et al., 2015; González-Gaya et al., 2019; Pérez-Carrera et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2013). Phenanthrene (PHE), fluoranthene (FLA) and pyrene (PYR) are the most commonly detected PAHs in the coastal surface microlayer (SML) (Guitart et al., 2007; Stortini et al., 2009), and they accounted for 92 %–96 % of the total amount of PAHs in the coastal surface waters of Nigeria (Benson et al., 2014).

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) is an ubiquitous OS compound at the sea surface (Lee et al., 1999), which derives from degradation of phytoplankton (Andreae, 1980), photodegradation of dimethylsulfide (DMS) (Barnes et al., 2006; Brimblecombe and Shooter, 1986), and microbial oxidation of DMS (Zhang et al., 1991). Because of a high Henry's Law coefficient (≈ 107 M atm−1) and mass accommodation coefficient (0.10), gaseous DMSO can be deposited on the seawater and freshwater surface where one finds enhanced DMSO concentrations (Legrand et al., 2001; Davidovits et al., 2006; González-Gaya et al., 2016). The highest levels of DMSO are detected in the ocean (1.5–532 nmol L−1) (Hatton et al., 1996; Lee and De Mora, 1996; Andreae, 1980; Asher et al., 2017), followed by rivers (< 2.5–210 nmol L−1) (Andreae, 1980), lakes (up to 180 nmol L−1) (Richards et al., 1994), rainwater (2–4 nmol L−1) (Ridgeway et al., 1992), and aerosols (69–125 pmol m−3) (Harvey and Lang, 1986). One of the main degradation pathways of DMSO is the reaction with hydroxyl radicals (OH) (Barnes et al., 2006), yielding methanesulfinic and methanesulfonic acids (Librando et al., 2004). Because the concentrations of DMSO are 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than those of DMS, the photochemical oxidation of DMSO may be a relatively more important process than the photo-oxidation of DMS (Lee et al., 1999).

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is directly emitted into the atmosphere by anthropogenic sources, such as fossil fuel combustion, coal, oil, and industrial processes (Smith et al., 2001). In addition, it can also be formed during the oxidation of DMS (Hoffmann et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2018). As a key contributor to aerosol nucleation, the role of SO2 at the air-water interface is also recognized as an efficient precursor of HOSO and OH radicals, following light absorption below 340 nm and its excitation to a very reactive triplet state (3SO) (Martins-Costa et al., 2018; Kroll et al., 2018). The majority of studies employed sulfate-containing seed particles to explore the formation pathway of OSs, while only a few were focused on the organosulfur formation pathway that is unique to SO2 chemistry (Blair et al., 2017; Shang et al., 2016; Passananti et al., 2016). Some previous studies have found that the heterogeneous reaction of SO2 with unsaturated acids can lead to the formation of OSs in the atmosphere (Shang et al., 2016; Passananti et al., 2016). However, it has also been found that monocyclic compounds such as terephthalic acid are not reactive via direct SO2 addition (Passananti et al., 2016), and there is still a knowledge gap concerning other OSs formation pathways involving heterogeneous SO2 oxidation. Indeed, air quality models cannot explain the quick increase of sulfate amounts in going from clean air to hazy events, when applying only the gas phase and aqueous phase chemistry of SO2 (Wang et al., 2014; G. Li et al., 2017).

Several studies have assessed the heterogeneous chemistry of atmospherically relevant oxidants with PAHs (Donaldson et al., 2009; Monge et al., 2010; Styler et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2019). Recently, Mekic et al. (2020a) and Jiang et al. (2021) have shown that the photosensitized degradation of DMSO by the excited triplet state of typical PAH compounds (fluorene (3FL∗), 3PHE∗, 3FLA∗ and 3PYR∗) leads to the formation of OSs, among others, in both the gas and aqueous phases.

In this study we investigated the formation of OSs from aqueous DMSO and/or PAHs/DMSO, initiated by gaseous SO2 in the dark and in the presence of simulated sunlight irradiation (300 nm < λ < 700 nm). The gaseous OS products were assessed by membrane inlet single photon ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (MI-SPI-TOFMS) (Zhang et al., 2019; Mekic et al., 2020a). The formed aqueous phase products were evaluated by means of ultrahigh-resolution electrospray ionization Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR-MS) (Jiang et al., 2016). The tentative reaction pathways of the formed OSs during the heterogeneous SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO under actinic illumination are supported by theoretical calculations of the Gibbs energy of the reaction. We show that oxidation by SO2 of PAHs/DMSO can release gaseous OSs, such as methanesulfonic acid (MSA), which are known precursors of secondary organic aerosols (SOA) in the atmosphere. The formation of an important number of OSs and unsaturated compounds, among others, was observed in the aqueous phase. We highlight the large amounts of generated linear and aromatic OSs, with potential to greatly influence the air-water exchange of organic compounds.

2.1 Photoreactor

A double-wall rectangular (5 × 5 × 2 cm) photoreactor was used to assess the reaction of gaseous SO2 with a water/organic film containing DMSO or DMSO/PAHs (Mekic et al., 2020a, b) The photoreactor was thermostated at ambient temperature (T = 293 K) in a thermostat bath (LAUDA ECO RE 630 GECO, Germany).

A SO2 flow of 150 mL min−1 mixed with an air flow of 750 mL min−1 (0–1 L min−1 HORIBA METRON mass flow controller; accuracy, ±1 %) allowed dilution of SO2 from a standard gas cylinder with 5 ppm concentration to a mixing ratio of ∼ 800 ppb that was flowing through the photoreactor. The applied mixing ratio of 800 ppb is higher compared to the atmospheric background mixing ratio that ranges from 1 to 70 ppb, but it is smaller than the SO2 mixing ratio in dilute volcanic plumes (for instance, a mixing ratio of ca. 10 ppm is observed about 10 km away from volcanic sources) (Oppenheimer et al., 1998), and it is also smaller compared to some previous laboratory studies that used 7.7–500 ppm of SO2 (Librando et al., 2014). The applied mixing ratio of 800 ppb would probably amplify the intensity of the detected product compounds but the formation profiles would still remain the same as in the case of smaller SO2 mixing ratios.

The concentration of PHE, FLA, and PYR (Sigma-Aldrich) used separately was 1 × 10−4 mol L−1. The three compounds were dissolved individually in a mixture of DMSO and ultrapure water with a proportion of 10 : 90 (Mekic et al., 2020b). Such a high DMSO concentration was necessary to dissolve the poorly water soluble PHE, FLA, and PYR (Mekic et al., 2020a, b). Several previous studies also used high concentrations of the organic co-solvent to assess the co-solvent effect on PAHs photolysis (Donaldson et al., 2009; Librando et al., 2014; Grossman et al., 2016). The reactor was filled with 10 mL freshly prepared DMSO/PAHs solution and irradiated with a xenon lamp (Xe, 500 W, 300 nm < λ < 700 nm) during the SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO. The spectral irradiance of the Xe lamp was measured with a calibrated spectroradiometer (Ocean Optics, USA) equipped with a linear-array CCD detector, and compared to the sunlight radiation (Mekic et al., 2020a, b). The irradiation time of the aqueous solution was 2 h.

Blank experiments of SO2 reaction were carried out with aqueous DMSO in all experimental conditions and with ultrapure water in the dark. All experiments were performed at least twice.

2.2 Single photon ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (SPI-ToF-MS)

A SPI-ToF-MS instrument (SPIMS 3000, Guangzhou Hexin Instrument Co., China) was used to detect the gas phase compounds formed during the light-induced heterogeneous reaction of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO. The SPI-ToF-MS instrument was explained in details in our previous studies (Deng et al., 2021; Mekic et al., 2020a), so here only a brief description is given in the Supplement.

2.3 Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR-MS)

As FT-ICR-MS was described in our previous paper, a brief description only is given in the Supplement. An in-house software was used to calculate all mathematically possible formulae for all ions with a signal-to-noise ratio above 10, using a mass tolerance of ±0.2 ppm. Data of blank samples were subtracted from those of all samples according to the same possible formulae.

The double bond equivalent (DBE) of the chemical formula CcHhOoNnSs is calculated using the following equation (Yassine et al., 2014):

The aromaticity equivalent (Xc) is calculated using the following equation:

where Xc is introduced to improve the identification and characterization of aromatic and condensed aromatic compounds, while m and n are the respective fractions of oxygen and sulfur atoms that are involved in the π-bonds of the molecular structure (Yassine et al., 2014). According to the model structural classes, the values of m and n were all set to 0. Threshold values of Xc between 2.5 and 2.7 (2.5 ≤ Xc < 2.7) and equal or greater than 2.7 (Xc≥2.7) were set as minimum criteria for the presence of aromatics or condensed aromatic compounds in an identified molecule (Blair et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2016). It should be highlighted that electron spray ionization (ESI) and desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) of OSs is especially favourable in the negative-ion mode, making the observed fraction of OSs further amplified (Blair et al., 2017).

2.4 Theoretical calculations

The proposed structures of all identified tentative OSs are based on the reasonable inferred elemental compositions for a single mass, following speculation through the NIST Chemistry WebBook (https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/mw-ser/, last access: 18 December 2020) and database of MI-SPI-ToF-MS or FT-ICR-MS. Considering that PHE, PYR, FLA and SO2 can all absorb Xe lamp radiation, theoretical calculations were carried out to obtain some insights into the degradation pathways of DMSO initiated by the excited triplet states 3PHE∗, 3PYR∗, 3FLA∗ and 3SO in the aqueous and gaseous phases as well as the interaction between light-excited PAHs and SO2.

All calculations shown here were assessed by the Gaussian 16W package (Frisch et al., 2016). The level of theory B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) was applied for geometry optimizations and frequency calculations for all molecules depicted in the reaction scheme (Mclean and Chandler, 1980; Binning and Curtiss, 1990). There were no imaginary frequencies for all molecules optimized. Single-point energy calculations were performed at a more expensive level, i.e. M06-2X/Def2-TZVP level (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008; Weigend and Ahlrichs, 2005; Weigend, 2006). The existence of possible geometric isomers and conformers for each species was considered and investigated and those with the lowest calculated Gibbs free energy were selected. Molecular oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2) and water molecules (H2O) were placed as reactants or products (if needed) to balance atoms in the schemes. Detailed Gibbs free energies for all molecules are presented in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplement, and the corresponding Gibbs energies of the reaction are shown in Scheme 1.

3.1 Gaseous OSs detected by MI-SPI-ToF-MS

To detect the gas phase compounds formed by heterogeneous SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO in the dark and under light irradiation, we applied MI-SPI-ToF-MS as a novel promising technology for the real-time monitoring of VOCs (Zhang et al., 2019; Mekic et al., 2020a).

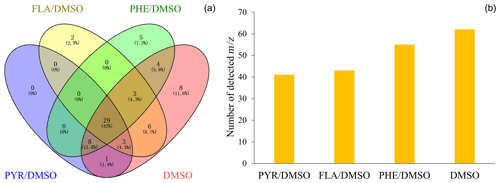

Figure 1Venn diagram of the detected signals in the gas phase for the heterogeneous reaction of SO2 with DMSO and PAHs/DMSO under light irradiation (300 nm < λ < 700nm) (a). The total number of identified signals between the heterogeneous reactions of SO2 with DMSO and PAHs/DMSO, under light irradiation (b).

Figure 1a shows the Venn diagram of the observed number of signals corresponding to the gas phase products of the light-induced heterogeneous SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO. The Venn diagram showing the comparison of the gaseous products formed under different conditions is presented in Fig. S1. The biggest contributor to the total number of secondarily formed products is the light-induced SO2 oxidation of DMSO (Fig. 1b). Among all detected signals (Table S4), we tentatively identified a number of unsaturated multifunctional molecules and OSs released in the gas phase from the reaction of SO2 with either DMSO or PAHs/DMSO, which are summarized in Table S5. The possibility for the existence of isomers and of different molecular formulae for the compounds with the same molecular weight should be noted (Nizkorodov et al., 2011). We emphasize the formation of gaseous OSs, and especially of those that are known to be SOA precursors. For example, the signals of 80, 94, 96, 112, 124, 126 were inferred as methanesulfinic acid (CH3SO2H, MSIA), methylsulfonylmethane ((CH3)2SO2, MSM), methanesulfonic acid (CH3SO3H, MSA), hydroxymethanesulfonic acid (CH4O4S, MSAOH), ethyl methanesulfonate (CH3SO3C2H5, EMS) and 2-hydroxyethenesulfonic acid (C2H5O4SH, ESAOH) (Berresheim et al., 1993; Berresheim and Eisele, 1998; Karl et al., 2007; Hopkins et al., 2008; Gaston et al., 2010; Ning et al., 2020; Dawson et al., 2012).

3.2 Formation profiles of gaseous OSs

In this study, we observed rapid formation of MSA, MSIA, MSM, EMS, MSAOH, and ESAOH (Figs. 2 and S2). Figure 2 shows typical time evolution profiles of MSA formed by the reaction of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO under light irradiation (300 nm < λ < 700 nm). The formation profiles of MSM, EMS, MSIA, MSAOH and ESAOH are shown in Fig. S2.

Figure 2Formation profiles of (methanesulfonic acid, MSA) upon light-induced heterogeneous reactions of SO2 with DMSO and PAHs/DMSO.

The SO2 oxidation of FLA/DMSO leads to MSA formation, the signal of which increases during the first 1 h and then slowly decreases (Fig. 2). The intensities of the product compounds (Figs. 2 and S2) decrease after 1 h most probably due to their reaction with SO2 and/or their photodegradation. The signal profile of MSA due to reaction of SO2 with PHE/DMSO is shorter than the others due to a technical problem of the instrument.

Intriguingly, the light-induced heterogeneous reaction of SO2 with DMSO, PYR/DMSO, and PHE/DMSO produces MSA that remains approximately stable over the course of the reaction. These results indicate that the suggested reaction between SO2 and DMSO or DMSO/PAHs under sunlight irradiation can produce MSA, which can be persistent enough to affect the new particle formation (NPF) process in the atmosphere. In Sect. 3.4 we suggest a tentative reaction pathway for the production of MSA and other OSs that is supported by theoretical calculations of Gibbs free energies.

3.3 Aqueous OSs detected by FT-ICR-MS

Numerous unsaturated multifunctional molecules and OSs were identified in the liquid phase during the reaction of SO2 with either DMSO or PAHs/DMSO by using FT-ICR-MS. The number of detected product compounds in the aqueous phase was significantly higher compared to those detected in the gas phase, due to very high sensitivity of FT-ICR-MS. Figure S3 shows all the formulae detected upon the reaction of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO under light irradiation. The shared formulae of the compounds detected upon reactions of SO2 with PYR/DMSO and FLA/DMSO or PHE/DMSO were more abundant than those individually formed by the reaction of SO2 with FLA/DMSO or PHE/DMSO. The number of detected compounds formed by reaction of SO2 with PYR/DMSO was dominant among all the products of SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO, both in the dark and under light irradiation (Figs. S3b and S4). Interestingly, the light-induced heterogeneous reaction of SO2 with PYR/DMSO released a small number of gaseous products but the highest number of aqueous phase products among all the studied PAHs/DMSO. In general, more CcHhOo (CHO) than CcHhOoSs (CHOS) products were formed in the aqueous phase with SO2 + PAHs/DMSO under irradiation (Fig. S5), with the only exception of PHE/DMSO. Even when subtracting the formulae detected upon SO2 oxidation of DMSO in the dark from those detected in the corresponding light-induced heterogeneous reaction, more compounds were produced under irradiation than in the dark.

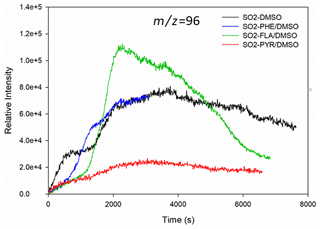

The analysis of iso-abundance plots of DBE vs. carbon numbers for the detected CHO and CHOS formulae is shown in text Sect. S3 and Figs. S6–S7. The two-dimensional van Krevelen (VK) plots for all CHOs and CHOSs formed during light-induced SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3The van Krevelen (VK) graph and aromaticity equivalent (grey with Xc < 2.5, black with 2.5 ≤ Xc < 2.7, and silver withXc ≥ 2.7) for the detected CHO and CHOS compounds in ESI− mode, formed upon light-induced heterogeneous reaction of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO. The Xc value is illustrated by the colour bar of each VK diagram, while the pie chart shows the number in different Xc intervals during these reactions.

The CHO and CHOS compounds formed during the reaction of SO2 with DMSO in the dark and under irradiation are shown in the VK plot depicted in Fig. S8. The same classes of compounds, detected upon heterogeneous reactions of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO under irradiation are illustrated in the VK plots depicted in Figs. S9 and S10, respectively. Most of the CHO and CHOS products identified with DMSO had high H C ratios (1.5–2.1) but O C ratios lower than 0.4, suggesting the formation of aliphatic compounds (Mekic et al., 2020a). However, the presence of aromatics could be additionally highlighted according to the analysis of a mathematical parameter, the aromaticity equivalent (Xc) (Yassine et al., 2014). About one half of the observed product compounds and especially CHOSs exhibited Xc ≥ 2.5, further indicating the formation of unsaturated compounds during the oxidation of DMSO by SO2 in the presence of light (Fig. S8).

The CHO and CHOS products displayed in the VK diagrams of Fig. 3 could be all separated into two different clusters. The O C ratios of CHOs were smaller than 0.7 for SO2 reaction with PYR/DMSO, and smaller than 0.4 for SO2 reactions with FLA/DMSO and PHE/DMSO. Nonetheless, a cluster with relatively few observed products was located in the upper part of the VK diagrams with high H C ratios (1.2–2.0), suggesting the formation of saturated aliphatic CHO compounds.

The other cluster that includes most of the detected products is located in the lower part of the VK diagrams, exhibiting low H C ratios (0.4–0.8) and indicating a degree of unsaturation (Mekic et al., 2020a; Lin et al., 2012). Most of the CHO compounds are probably condensed aromatic compounds as suggested by their Xc values higher than 2.5, especially in the case of products observed upon reaction of SO2 with FLA/DMSO.

The observed CHOS products emerging from the reaction of SO2 with PHE/DMSO, also depicted in Fig. 3 could be divided into two groups based on their distribution of H C and O C ratios. Generally, the formed CHOS products that are located in the upper part of the VK diagrams (Fig. 3) have a broad range of O C ratios spanning from 0.2 to 0.8, H C ratios in a range of 1.4–2.0, and low DBE (1–4). This observation implies the formation of long-chain aliphatic-like CHOSs during the light-assisted oxidation of PHE/DMSO by SO2. In addition, a large fraction of compounds detected during the reaction of SO2 with PHE/DMSO exhibits Xc < 2.5, and is thus consistent with the formation of long-chain aliphatic-like CHOSs (Wang et al., 2021). The CHOS products located in the lower part of the VK diagrams have H C ratios of 0.4–1.0, which are similar to those of the observed CHO products. However, the CHOS compounds exhibit higher O C ratios that range between 0.2 and 0.8 for the reaction of SO2 with PYR/DMSO, and 0.2–0.6 for the reaction of SO2 with FLA/DMSO and PHE/DMSO. A possible reason is the occurrence of sulfates with R-OSO groups, sulfonates with R-SO groups and sulfones with R-SO2-R′ groups (Bruggemann et al., 2020). These CHOS products partly overlap with the oxidized aromatic hydrocarbons (Kourtchev et al., 2014). Moreover, the majority of the CHOS products exhibit a condensed aromatic structure as indicated by their Xc values higher than 2.7.

Based on the VK plots, here we used the different spacing patterns for Kendrick mass defect (KMD) analysis (Lin et al., 2012). The subunits including CH2, C2H2, CH3, C4H2, C6H2 for the same CHO homologous series, and CH2, C2H2 for CHOS homologues were identified during the light-induced SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO. More subunits were found for CHOS homologues during the SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO under all experimental conditions (Fig. S11). The literature suggests that subunits of CH2 and C2H2 were the most repeating mass building increments for either CHO or CHOS oxidized aromatic compounds (Lin et al., 2012). These identified subunits were responsible for the increase in the molecular mass of the detected compounds (Altieri et al., 2006), presumably leading to straight-chain alkanes and olefins.

3.4 Tentative reaction mechanisms and the production of OSs

The proposed general pathway suggested in the literature is the direct addition of SO2 to a double bond or the separate addition of SO2 to the cleavage of a double bond. This may also apply to PAHs/DMSO, because of the chromophoric nature of the SO2 adduct with C=C bonds (Passananti et al., 2016). Herein, we show that this reaction pathway of SO2 may indeed proceed on PAHs and is supported by theoretical calculations of the Gibbs energy of the reaction, based on the information obtained from the detected tentative products.

The reaction pathway suggests that photoexcitation of PAHs and SO2 proceeds through the electronic transition, followed by intersystem crossing to produce the corresponding excited triplet states (3PAHs∗ and 3SO) (Mekic et al., 2020a), which most likely play an important role during the oxidation of PAHs/DMSO. Previous work has shown that the photochemical reaction of 3PAHs∗ with DMSO in water would lead to the formation of singlet oxygen (1O2) via energy transfer reaction with ground triplet-state oxygen (3O2) (Wilkinson et al., 1995), the formation of hydroxyl radical upon water oxidation by other triplets states (Brigante et al., 2010) and the formation of more radicals through electron transfer. Many triplet states work in the presence of oxygen as O2 quenches most but not all of them. The excited triplet state of SO2 (3SO) formed upon light irradiation reacts with water molecules yielding OH radicals as follows (Martins-Costa et al., 2018; Kroll et al., 2018):

Alternatively, SO2 can form π complexes with C=C bonds of PAHs upon ring opening, which may undergo transformation to diradical organosulfur intermediates, which in turn can react with dissolved O2 leading to production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as OH radicals. (Shang et al., 2016) The formation of diradical organosulfur intermediates and ROS have been suggested for reactions of SO2 with alkenes and fatty acids (Shang et al., 2016; Passananti et al., 2016) but here we suggest that the same pathway may occur for the reaction of SO2 with PAHs. While the SO2 addition to the C=C bond would be responsible for the OSs, the CHO oxidation products could be explained by radical chain reactions triggered by ROS (Shang et al., 2016; Passananti et al., 2016). The OH radical attack on PAHs/DMSO could also yield carbon-centred radicals or alkyl radicals which further react with O2 yielding peroxyl (RO2) and hydroxyperoxyl radicals (HO2) (Von Sonntag et al., 1997).

Although RO2 could directly transform into organic sulfates by SO2, it has been shown that SO2 could accelerate heterogeneous OH oxidation rates by 10–20 times, originating from the radical chain reactions propagated by alkoxy radicals formed by the reaction of peroxyl radicals with SO2 (Richards-Henderson et al., 2016). Peroxyl radicals undergo self-reactions leading to the formation of stable products (ketone or alcohol) or alkoxy radicals (Richards-Henderson et al., 2016) In the presence of 3SO, the OH production rate increases by several orders of magnitude at the air-water interface, thus resulting in the increase of radical chain length by alkoxy radicals (Martins-Costa et al., 2018).

Although it is difficult to distinguish which mechanism is prevalent in the environment, in this study, the comprehensive reaction schemes explain the detected sulfur-containing unsaturated multifunctional compounds emerging from light-induced SO2 oxidation of PAHs and DMSO at the air-water interface. The tentative reaction pathways describing the formation of aqueous phase products including their description are given in the text Sect. S4 and Scheme S1. The suggested reaction mechanism for the formation of gas phase product compounds is shown in Scheme 1 in the following section.

3.5 Reaction mechanism of the gaseous compounds

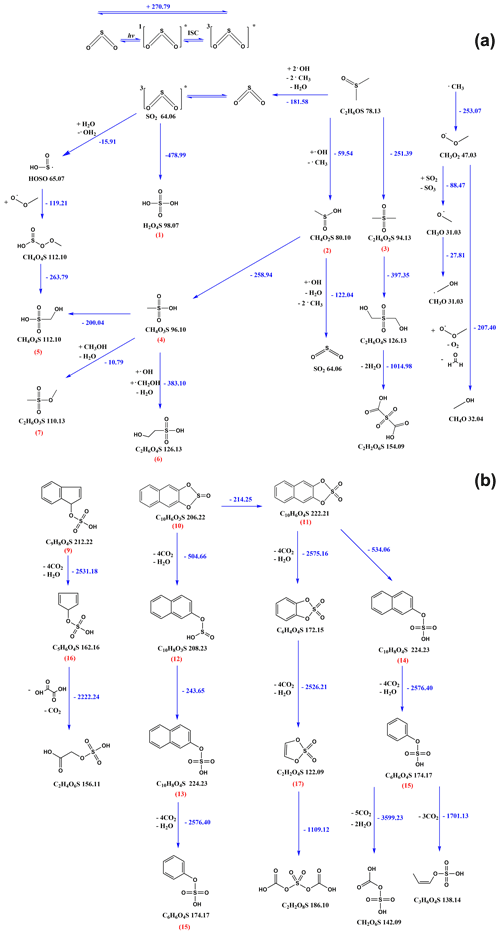

A detailed mechanism for the 3SO oxidation of PAHs/DMSO is presented in Scheme 1, which could be divided into two proposed general pathways including (1) self-oxidation of 3SO and oxidation of DMSO initiated by 3SO and 3PAHs∗, and (2) photodegradation of sulfur-containing PAH compounds that were initially formed from PAHs by 3SO.

-

Pathway A: in this pathway we emphasize the formation and transformation of MSA that plays a key role during the formation of the detected OSs (Scheme 1a).

The self-oxidation of 3SO could yield sulfuric acid (H2SO4) (1). Meanwhile, DMSO can be oxidized by oxygen and the OH radicals formed by 3SO and 3PAHs∗, yielding MSIA (CH4O2S) (2) and MSM (C2H6O2S) (3). Dehydration of MSIA (2) (Urbanski et al., 1998; Kukui et al., 2003; Allen et al., 1999; Arsene et al., 2002) and sulfuric acid (1) would lead to the production of MSA (CH4SO3) (4). More radical species such as the methyl radical (CH3), would be formed during the OH-addition route in the gas phase atmospheric oxidation of DMSO, resulting in the formation of SO2 that would participate in the subsequent oxidation reactions (Falbe-Hansen et al., 2000; González-García et al., 2006; Arsene et al., 2002; Urbanski et al., 1998).

Further transformation would occur upon oxidation of MSA (4) or self-oxidation of 3SO to yield MSAOH (CH4O4S) (5) via the OH2 radical. The OH and CH2OH radicals could oxidize MSA (4) into ESAOH (C2H6O4S) (6) and C2H6O3S (7).

-

Pathway B: although linear OS products would also be generated upon addition of 3SO to double bonds, formed after ring opening of the PAH molecules, we stress that the occurrence of gaseous OSs mostly emerges from the photodegradation of aromatic OS products. Under our experimental conditions, 3SO oxidation of PAHs would prevail over PAHs photodegradation and would lead to sulfur-containing PAHs. Here we only present the general degradation process and one proposed pathway for the given species. The details of intermediate products are not shown in this scheme.

For example, C9H8O4S (9), C10H6O3S (10), and C10H6O4S (11) (Scheme 1b) appear as the photodegradation products of C16H10O3S or C16H12O3S, C14H10O3S and C14H10O4S (Scheme S1). These compounds were further transformed upon oxygen attack, then followed by cleavage of the phenyl ring through a highly exoergonic process. The S(IV) in sulfite group of C10H6O3S (10) would first undergo oxidation by the strong oxidizing agents in the system to result in more stable S(VI) in C10H8O3S (12). Cleavage of the 5-member ring would yield C10H8O4S (13) and C10H8O4S (14), followed by the yield of phenyl hydrogen sulfate (C6H6O4S) (15) via phenyl ring cleavage. Meanwhile, phenyl ring cleavage of condensed aromatics would also yield C5H6O4S (16) and 1,3,2-dioxathiole 2,2-dioxide (C2H2O4S) (17). Subsequently, the attack of oxygen or radicals initiates the exoergonic opening of a 5-member ring or a phenyl ring, resulting in linear OSs under rapid oxidative scission.

3.6 Comparison with OSs identified within atmospheric aerosols

Table S6 shows the intercomparison of the OSs detected here, mainly formed upon light-induced reactions of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO, with OSs identified during various field campaigns. It should be stressed that the agreement between the chemical formulae of the OSs detected in this study and those from field campaigns does not necessarily imply the same molecular structure, because multiple structural isomers are plausible for each formula (Mekic et al., 2020a; Nizkorodov et al., 2011). A total of 81 tentative OSs from this study overlapped with those identified in ambient aerosol samples, of which 33 OS formulae were detected in the aqueous phase. Only 4 liquid phase OS formulae were detected following the reactions of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO in the dark. The blue-shaded OSs are generated exclusively by the reaction of SO2 with DMSO. The group of compounds with yellow-shaded area are produced by the reaction of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO. Finally, the green-shaded area summarizes the OSs detected with both SO2 + DMSO and SO2 + PAHs/DMSO. Most of the liquid phase OS formulae (chemical formulae in bold) were formed individually upon SO2 oxidation of PYR/DMSO and DMSO. The product compounds individually formed by the reaction of SO2 with PHE/DMSO and the shared formulae generated by the reaction of SO2 with DMSO and PAHs/DMSO make the biggest contribution to the gas phase OSs. These observations highlight the importance of the SO2 oxidation reactions of DMSO and/or PAHs/DMSO at the freshwater and seawater surfaces or in the liquid films of the aerosol particles, which would represent an important source of OSs.

Tentatively identified VOC precursors are also highlighted in Table S6. The tentative precursors of more than half of the identified OSs in the atmosphere still remain unexplained and unknown. Most of the identified overlapping OSs are probably long alkyl chain OSs, thus their tentative precursors were designated as alkyl-containing OSs from anthropogenic sources (Tao et al., 2014). There are three overlapping compounds which were assumed to be aromatic OSs, thus their precursors were considered as 2-MeNAP and methylbenzyl sulfate (Staudt et al., 2014; Riva et al., 2015).

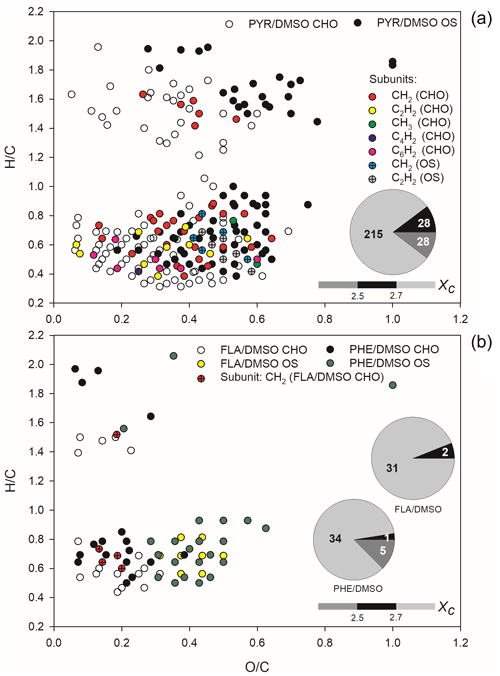

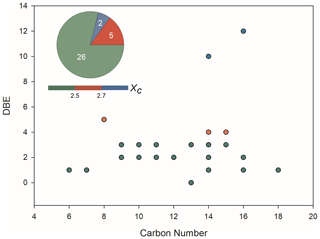

Figure 4 shows the iso-abundance plot of DBE vs. carbon numbers according to the corresponding Xc of liquid-phase OS formulae, intuitively indicating that most of the identified OS formulae with low DBE are presumably long chain aliphatic-like compounds. Moreover, there were seven detected OSs with aromatic structure that were consistent with those identified in aerosol samples from field studies. Among those aromatic OSs, only C8H8O5S has a tentatively identified VOC precursor, 2-MeNAP (Riva et al., 2015). It has been shown that aromatic OSs are produced from the interaction of aromatics with sulfur-containing species. For example, the gas-phase photo-oxidation of PAHs in the presence of sulfate aerosol, and the aqueous phase reactions of several monocyclic aromatics with sulfite in the presence of Fe3+ mediated by sulfoxy radical anions can generate aromatic OSs (Riva et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2020). The reaction of SOA particles formed from photo-oxidation of biodiesel and diesel fuel with SO2 was demonstrated to yield a large number of aromatic OS species (Blair et al., 2017).

Figure 4Iso-abundance plot of DBE vs. carbon numbers according to the corresponding aromaticity equivalent (green with Xc < 2.5, red with 2.5 ≤ Xc < 2.7, and blue withXc ≥ 2.7) for the detected organic sulfur species in the liquid phase, which had also been identified in ambient aerosol samples.

In our previous study we have identified the OSs formed in the absence of SO2 as a precursor, during the photodegradation of DMSO initiated by the excited triplet state of fluorene in both liquid and gas phases (Mekic et al., 2020a, b). It is evident that the inclusion of SO2 as a precursor in the reaction system enhances the formation of OSs, including those having similar structures as those detected in field studies. It can be considered that the light-induced reaction of SO2 with DMSO or a mixture of DMSO and PAHs is a previously unknown, additional atmospheric source of OSs (Berresheim et al., 1993; Berresheim and Eisele, 1998; Karl et al., 2007; Hopkins et al., 2008; Gaston et al., 2010; Ning et al., 2020; Dawson et al., 2012).

The reaction of DMSO with OH leads to formation of MSIA (Barnes et al., 2006), which in turn may react again with OH radicals to form MSA (Librando et al., 2004; Barnes et al., 2006; Rosati et al., 2021). Gaseous MSA is a particularly important compound that can participate in the initial nucleation and growth step of particles, known as the NPF process (Schobesberger et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017; Perraud et al., 2015). Declining gaseous MSA concentrations were actually reported during marine NPF events, thereby suggesting that MSA may enter the aerosol particles at the earliest possible stage and significantly assist in cluster formation (Dall'osto et al., 2012; Bork et al., 2014). MSA is the simplest organosulfate compound, which can be mainly formed during the OH oxidation of DMS (Barnes et al., 2006; Rosati et al., 2021). Gas-phase MSA above the oceans and in coastal areas represents about 10 %–100 % of the gas phase sulfuric acid (SA) concentration (Berresheim et al., 2002). It has been suggested that MSA can enhance particle formation from SA by 15 %–300 %, if equal quantities of SA and MSA are present (Bork et al., 2014). There is a discrepancy between the modelled and measured concentration profiles of MSA, which indicates a missing MSA source. This source seems to be much stronger than the estimated production stemming from OH oxidation of DMS (S. H. Zhang et al., 2014). Y. Zhang et al. (2014) suggested a strong daytime source of MSA, the precursor of which may be DMSO (Y. Zhang et al., 2014). The model estimations indicated that higher DMSO concentrations would lead to enhanced chemical production of MSA to reach 4.9 × 107 molecules cm−2 s−1, which is similar to the strength of the missing source of MSA.

Here, we show that during daytime the reactions of light-excited SO2 and aqueous DMSO or DMSO/PAHs could represent an important source of gaseous MSA in the atmosphere near the water (ocean, lake and river) surface. In particular, the reaction of SO2 with DMSO leads to enhanced formation of organic sulfur compounds compared to the photosensitized degradation of DMSO initiated by the excited triplet states of PAH compounds (Fig. S13). The results of this research point to the complexity of the chemical processes responsible for the formation of organic sulfur compounds. Considering the abundance of SO2 in the atmosphere and the omnipresence of water-adsorbed PAHs and DMSO compounds, the future modelling studies should consider both pathways, i.e. (1) photosensitized degradation of DMSO initiated by the excited triplet states of PAHs (Zhang et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2021), and (2) heterogeneous chemistry of SO2 with PAHs/DMSO and DMSO, as alternative formation pathways of organic sulfur compounds in the atmosphere. In this study, many detected aromatic and linear OSs formed during the light-induced SO2 oxidation of PAHs/DMSO are reported for the first time. An important number of detected compounds overlapped with those of ambient OSs identified during field measurements. We suggest that a plausible mechanism for OSs formation via direct addition of SO2 to the C=C double bond is not only limited to alkenes and unsaturated fatty acids (Passananti et al., 2016; Shang et al., 2016) but is also valid for anthropogenic precursors such as PAHs. A large amount of organosulfates and especially aromatic organosulfates could be formed through this pathway and released into water and the ambient atmosphere. These OSs can form surfactant films on aerosol particles in the boundary layer, by which means they influence the surface tension and hygroscopicity of particles (Decesari et al., 2011; Tao et al., 2014). Indeed, the OSs formation pathway in the heterogeneous reaction between SO2 and PAHs/DMSO is of great significance because OSs generated at the water surface would influence the air-water exchange and enhanced gaseous OSs would result in the formation of SOA. Moreover, the OS products formation from PAHs initiated by SO2 is also of importance in urban areas where PAHs concentrations are usually high in ambient air (Zhu et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2020). Finally, aromatic OSs occurring in urban aerosols represent a still unrecognized source of toxic products (Riva et al., 2015).

Based on the observed emission rates of OSs in this study, we estimate emission fluxes of MSA, and MSIA, among others, considering realistic environmental conditions, SO2 mixing ratios ranging between 2 and 50 ppb, surface UV irradiation (Brüggemann et al., 2018), surface microlayer coverage with PAHs/DMSO, to account for the potential impact of the heterogeneous SO2 (photo)chemistry with PAHs/DMSO, on the aerosol production in marine boundary layer, the results of which will be published elsewhere.

All data in this manuscript are freely available upon request through the corresponding author (gligorovski@gig.ac.cn).

Additional information includes 16 figures, 6 tables, 1 reaction scheme, short description of MI-SPI-TOF-MS and FT-ICR-MS, analysis of FT-ICR-MS aqueous phase products based on DBE vs carbon number iso-abundance plot, reaction mechanism of the aqueous phase product compounds. The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-4237-2022-supplement.

HJ and SG wrote the paper; SG designed the research; HJ and YW performed the laboratory experiments; HJ interpreted the MI-SPI-TOF-MS and FT-ICR-MS data and contributed to relevant discussion; HJ, YH and SL speculated reaction pathways; YH carried out the Gibbs energies theoretical calculation of the reaction initiated by 3PAHs∗ and 3SO; BJ contributed to the FT-ICR-MS data analysis; XL contributed to the MI-SPI-TOF-MS data analysis; LY and TL contributed to the relevant discussion of reaction mechanisms; LC and DV contributed to the discussion of the results and implications. All the authors contributed to revise the manuscript and approve the final version.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 42007200, 41773131, 41977187, and 42177087), Guangdong Foundation for Program of Science and Technology Research (no. 2021A1515011555), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. 2019M653105). This study was funded by Institute Director Foundation of GIG (no. 2019SZJJ-10), International Cooperation Grant of Chinese Academy of Science (no. 132744KYSB20190007), State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry (SKLOG2020-5, and KTZ_17101).

The authors thank Jiangping Liu, Huifan Deng, Wentao Zhou and Gwendal Loisel for their assistance in the laboratory analyses. This is a contribution of the GIGCAS (Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42007200, 41773131, 41977187, and 42177087), Guangdong Foundation for Program of Science and Technology Research (grant no. 2021A1515011555), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2019M653105), International Cooperation Grant of Chinese Academy of Science (grant no. 132744KYSB20190007), and State Key Laboratory of Organic Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry (grant nos. SKLOG2020-5 and KTZ_17101).

This paper was edited by Markus Ammann and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Allen, H. C., Gragson, D., and Richmond, G.: Molecular structure and adsorption of dimethyl sulfoxide at the surface of aqueous solutions, J. Phys. Chem. B, 103, 660–666, 1999.

Altieri, K. E., Carlton, A. G., Lim, H.-J., Turpin, B. J., and Seitzinger, S. P.: Evidence for oligomer formation in clouds: Reactions of isoprene oxidation products, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 4956–4960, https://doi.org/10.1021/es052170n, 2006.

Andreae, M. O. J. L.: Dimethylsulfoxide in marine and freshwaters, Limnol. Oceanogr., 25, 1054–1063, 1980.

Arsene, C., Barnes, I., Becker, K. H., Schneider, W. F., Wallington, T. T., Mihalopoulos, N., and Patroescu-Klotz, I. V. J. E. S.: Formation of methane sulfinic acid in the gas-phase OH-radical initiated oxidation of dimethyl sulfoxide, Environ. Sci. Technol., 36, 5155–5163, 2002.

Asher, E., Dacey, J. W., Ianson, D., Peña, A., and Tortell, P. D.: Concentrations and cycling of DMS, DMSP, and DMSO in coastal and offshore waters of the Subarctic Pacific during summer, 2010–2011, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 122, 3269–3286, 2017.

Barnes, I., Hjorth, J., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl sulfoxide and their oxidation in the atmosphere, Chem. Rev., 106, 940–975, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020529+, 2006.

Benson, N. U., Essien, J. P., Asuquo, F. E., and Eritobor, A. L.: Occurrence and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface microlayer and subsurface seawater of Lagos Lagoon, Nigeria, Environ. Monit. Assess., 186, 5519–5529, 2014.

Berresheim, H. and Eisele, F.: Sulfur chemistry in the Antarctic Troposphere Experiment: An overview of project SCATE, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 103, 1619–1627, 1998.

Berresheim, H., Eisele, F., Tanner, D., McInnes, L., Ramsey-Bell, D., and Covert, D.: Atmospheric sulfur chemistry and cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) concentrations over the northeastern Pacific coast, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 98, 12701–12711, 1993.

Berresheim, H., Elste, T., Tremmel, H. G., Allen, A. G., Hansson, H. C., Rosman, K., Dal Maso, M., Makela, J. M., Kulmala, M., and O'Dowd, C. D.: Gas-aerosol relationships of H2SO4, MSA, and OH: Observations in the coastal marine boundary layer at Mace Head, Ireland, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, PAR 5-1–PAR 5-12,, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000jd000229, 2002.

Binning Jr., R. and Curtiss, L.: Compact contracted basis sets for third-row atoms: Ga–Kr, J. Comput. Chem., 11, 1206–1216, 1990.

Blair, S. L., MacMillan, A. C., Drozd, G. T., Goldstein, A. H., Chu, R. K., Paša-Tolić, L., Shaw, J. B., Tolić, N., Lin, P., and Laskin, J.: Molecular characterization of organosulfur compounds in biodiesel and diesel fuel secondary organic aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 119–127, 2017.

Bork, N., Elm, J., Olenius, T., and Vehkamäki, H.: Methane sulfonic acid-enhanced formation of molecular clusters of sulfuric acid and dimethyl amine, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 12023–12030, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-12023-2014, 2014.

Brigante, M., Charbouillot, T., Vione, D., and Mailhot, G.: Photochemistry of 1-nitronaphthalene: A potential source of singlet oxygen and radical species in atmospheric waters, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 2830–2836, 2010.

Brimblecombe, P. and Shooter, D.: Photo-oxidation of dimethylsulphide in aqueous solution, Mar. Chem., 19, 343–353, 1986.

Brüggemann, M., Hayeck, N., and George, C.: Interfacial photochemistry at the ocean surface is a global source of organic vapors and aerosols, Nat. Commun., 9, 2101, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04528-7, 2018.

Bruggemann, M., Xu, R., Tilgner, A., Kwong, K. C., Mutzel, A., Poon, H. Y., Otto, T., Schaefer, T., Poulain, L., Chan, M. N., and Herrmann, H.: Organosulfates in Ambient Aerosol: State of Knowledge and Future Research Directions on Formation, Abundance, Fate, and Importance, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 3767–3782, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b06751, 2020.

Cai, D., Wang, X., Chen, J., and Li, X.: Molecular Characterization of Organosulfates in Highly Polluted Atmosphere Using Ultra-High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, e2019JD032253, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jd032253, 2020.

Chen, H., Varner, M. E., Gerber, R. B., and Finlayson-Pitts, B. J.: Reactions of Methanesulfonic Acid with Amines and Ammonia as a Source of New Particles in Air, J. Phys. Chem. B, 120, 1526–1536, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b07433, 2016.

Chen, J., Ehrenhauser, F. S., Valsaraj, K. T., and Wornat, M. J.: Uptake and UV-photooxidation of gas-phase PAHs on the surface of atmospheric water films. 1. Naphthalene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 110, 9161–9168, 2006.

Chen, Q., Sherwen, T., Evans, M., and Alexander, B.: DMS oxidation and sulfur aerosol formation in the marine troposphere: a focus on reactive halogen and multiphase chemistry, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 13617–13637, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-13617-2018, 2018.

Cincinelli, A., Stortini, A. M., Perugini, M., Checchini, L., and Lepri, L.: Organic pollutants in sea-surface microlayer and aerosol in the coastal environment of Leghorn – (Tyrrhenian Sea), Mar. Chem., 76, 77–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4203(01)00049-4, 2001.

Dall'Osto, M., Ceburnis, D., Monahan, C., Worsnop, D. R., Bialek, J., Kulmala, M., Kurten, T., Ehn, M., Wenger, J., Sodeau, J., Healy, R., and O'Dowd, C.: Nitrogenated and aliphatic organic vapors as possible drivers for marine secondary organic aerosol growth, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 117, D12311, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012jd017522, 2012.

Davidovits, P., Kolb, C. E., Williams, L. R., Jayne, J. T., and Worsnop, D. R.: Mass accommodation and chemical reactions at gas-liquid interfaces, Chem. Rev., 106, 1323–1354, 2006.

Dawson, M. L., Varner, M. E., Perraud, V., Ezell, M. J., Gerber, R. B., and Finlayson-Pitts, B. J.: Simplified mechanism for new particle formation from methanesulfonic acid, amines, and water via experiments and ab initio calculations, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 18719–18724, 2012.

Decesari, S., Finessi, E., Rinaldi, M., Paglione, M., Fuzzi, S., Stephanou, E., Tziaras, T., Spyros, A., Ceburnis, D., and O'Dowd, C.: Primary and secondary marine organic aerosols over the North Atlantic Ocean during the MAP experiment, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 116, D22210, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016204, 2011.

Deng, H., Liu, J., Wang, Y., Song, W., Wang, X., Li, X., Vione, D., and Gligorovski, S.: Effect of Inorganic Salts on N-Containing Organic Compounds Formed by Heterogeneous Reaction of NO2 with Oleic Acid, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 7831–7840, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c01043, 2021.

Donaldson, D., Kahan, T., Kwamena, N., Handley, S., and Barbier, C.: Atmospheric chemistry of urban surface films, in: Atmospheric Aerosols Characterization, Chemistry, Modeling, and Climate, ACS Publications, 79–89, https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2009-1005.ch006, 2009.

Falbe-Hansen, H., Sørensen, S., Jensen, N., Pedersen, T., and Hjorth, J.: Atmospheric gas-phase reactions of dimethylsulphoxide and dimethylsulphone with OH and NO3 radicals, Cl atoms and ozone, Atmos. Environ., 34, 1543–1551, 2000.

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Li, X., Caricato, M., Marenich, A. V., Bloino, J., Janesko, B. G., Gomperts, R., Mennucci, B., Hratchian, H. P., Ortiz, J. V., Izmaylov, A. F., Sonnenberg, J. L., Williams, Ding, F., Lipparini, F., Egidi, F., Goings, J., Peng, B., Petrone, A., Henderson, T., Ranasinghe, D., Zakrzewski, V. G., Gao, J., Rega, N., Zheng, G., Liang, W., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Throssell, K., Montgomery Jr., J. A., Peralta, J. E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M. J., Heyd, J. J., Brothers, E. N., Kudin, K. N., Staroverov, V. N., Keith, T. A., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A. P., Burant, J. C., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Millam, J. M., Klene, M., Adamo, C., Cammi, R., Ochterski, J. W., Martin, R. L., Morokuma, K., Farkas, O., Foresman, J. B., and Fox, D. J.: Gaussian 16, Revision. C.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016.

Gaston, C. J., Pratt, K. A., Qin, X., and Prather, K. A.: Real-time detection and mixing state of methanesulfonate in single particles at an inland urban location during a phytoplankton bloom, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 1566–1572, 2010.

González-García, N., González-Lafont, À., and Lluch, J. M.: Variational transition-state theory study of the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and OH reaction, J. Phys. Chem. A, 110, 798–808, 2006.

González-Gaya, B., Fernández-Pinos, M.-C., Morales, L., Méjanelle, L., Abad, E., Piña, B., Duarte, C. M., Jiménez, B., and Dachs, J.: High atmosphere–ocean exchange of semivolatile aromatic hydrocarbons, Nat. Geosci., 9, 438–442, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2714, 2016.

González-Gaya, B., Martínez-Varela, A., Vila-Costa, M., Casal, P., Cerro-Gálvez, E., Berrojalbiz, N., Lundin, D., Vidal, M., Mompeán, C., and Bode, A.: Biodegradation as an important sink of aromatic hydrocarbons in the oceans, Nat. Geosci., 12, 119–125, 2019.

Grossman, J. N., Stern, A. P., Kirich, M. L., and Kahan, T. F.: Anthracene and pyrene photolysis kinetics in aqueous, organic, and mixed aqueous-organic phases, Atmos. Environ., 128, 158–164, 2016.

Guitart, C., Garcia-Flor, N., Bayona, J. M., and Albaiges, J.: Occurrence and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the coastal surface microlayer, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 54, 186–194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.10.008, 2007.

Hardy, J. T., Crecelius, E. A., Antrim, L. D., Kiesser, S. L., Broadhurst, V. L., Boehm, P. D., Steinhauer, W. G., and Coogan, T. H.: Aquatic surface microlayer contamination in chesapeake bay, Mar. Chem., 28, 333–351, 1990.

Harvey, G. R. and Lang, R. F.: Dimethylsulfoxide and dimethylsulfone in the marine atmosphere, Geophys. Res. Lett., 13, 49–51, 1986.

Hatton, A., Malin, G., Turner, S., and Liss, P.: DMSO, A Significant Compound in the Biogeochemical Cycle of DMS., in: Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds, Springer, 405–412, ISBN 978-1-4613-8024-5, 1996.

Hoffmann, E. H., Tilgner, A., Schrodner, R., Brauer, P., Wolke, R., and Herrmann, H.: An advanced modeling study on the impacts and atmospheric implications of multiphase dimethyl sulfide chemistry, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 11776–11781, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606320113, 2016.

Hopkins, R. J., Desyaterik, Y., Tivanski, A. V., Zaveri, R. A., Berkowitz, C. M., Tyliszczak, T., Gilles, M. K., and Laskin, A.: Chemical speciation of sulfur in marine cloud droplets and particles: Analysis of individual particles from the marine boundary layer over the California current, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 113, D04209, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008954, 2008.

Huang, L., Liu, T., and Grassian, V. H.: Radical-Initiated Formation of Aromatic Organosulfates and Sulfonates in the Aqueous Phase, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 11857–11864, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c05644, 2020.

Jiang, B., Kuang, B. Y., Liang, Y., Zhang, J., Huang, X. H. H., Xu, C., Yu, J. Z., and Shi, Q.: Molecular composition of urban organic aerosols on clear and hazy days in Beijing: a comparative study using FT-ICR MS, Environ. Chem., 13, 888–901, https://doi.org/10.1071/en15230, 2016.

Jiang, H., Carena, L., He, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, W., Yang, L., Luan, T., Li, X., Brigante, M., Vione, D., and Gligorovski, S.: Photosensitized Degradation of DMSO Initiated by PAHs at the Air-Water Interface, as an Alternative Source of Organic Sulfur Compounds to the Atmosphere, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2021JD035346, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035346, 2021.

Kamens, R. M., Zhang, H., Chen, E. H., Zhou, Y., Parikh, H. M., Wilson, R. L., Galloway, K. E., and Rosen, E. P.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from toluene in an atmospheric hydrocarbon mixture: Water and particle seed effects, Atmos. Environ., 45, 2324–2334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.007, 2011.

Karl, M., Gross, A., Leck, C., and Pirjola, L.: Intercomparison of dimethylsulfide oxidation mechanisms for the marine boundary layer: Gaseous and particulate sulfur constituents, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 112, D15304, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007914, 2007.

Kourtchev, I., O'Connor, I. P., Giorio, C., Fuller, S. J., Kristensen, K., Maenhaut, W., Wenger, J. C., Sodeau, J. R., Glasius, M., and Kalberer, M.: Effects of anthropogenic emissions on the molecular composition of urban organic aerosols: An ultrahigh resolution mass spectrometry study, Atmos. Environ., 89, 525–532, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.02.051, 2014.

Kroll, J. A., Frandsen, B. N., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Vaida, V.: Atmospheric hydroxyl radical source: Reaction of triplet SO2 and water, J. Phys. Chem. A, 122, 4465–4469, 2018.

Kukui, A., Borissenko, D., Laverdet, G., and Le Bras, G.: Gas-phase reactions of OH radicals with dimethyl sulfoxide and methane sulfinic acid using turbulent flow reactor and chemical ionization mass spectrometry, J. Phys. Chem. A, 107, 5732–5742, 2003.

Kundu, S., Quraishi, T. A., Yu, G., Suarez, C., Keutsch, F. N., and Stone, E. A.: Evidence and quantitation of aromatic organosulfates in ambient aerosols in Lahore, Pakistan, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 4865–4875, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-4865-2013, 2013.

Lammel, G.: Polycyclic aromatic compounds in the atmosphere – a review identifying research needs, Polycycl. Aromat. Comp., 35, 316–329, 2015.

Lee, P. and De Mora, S.: DMSP, DMS and DMSO concentrations and temporal trends in marine surface waters at Leigh, New Zealand, in: Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds, Springer, 391–404, ISBN 978-0-306-45306-9, 1996.

Lee, P. A., de Mora, S. J., and Levasseur, M.: A review of dimethylsulfoxide in aquatic environments, Atmos.-Ocean, 37, 439–456, https://doi.org/10.1080/07055900.1999.9649635, 1999.

Legrand, M., Sciare, J., Jourdain, B., and Genthon, C.: Subdaily variations of atmospheric dimethylsulfide, dimethylsulfoxide, methanesulfonate, and non-sea-salt sulfate aerosols in the atmospheric boundary layer at Dumont d'Urville (coastal Antarctica) during summer, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 106, 14409–14422, 2001.

Li, G., Bei, N., Cao, J., Huang, R., Wu, J., Feng, T., Wang, Y., Liu, S., Zhang, Q., Tie, X., and Molina, L. T.: A possible pathway for rapid growth of sulfate during haze days in China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 3301–3316, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-3301-2017, 2017.

Li, J., Li, F., and Liu, Q.: PAHs behavior in surface water and groundwater of the Yellow River estuary: evidence from isotopes and hydrochemistry, Chemosphere, 178, 143–153, 2017.

Librando, V., Tringali, G., Hjorth, J., and Coluccia, S.: OH-initiated oxidation of DMS/DMSO: reaction products at high NOx levels, Environ. Pollut., 127, 403–410, 2004.

Librando, V., Bracchitta, G., de Guidi, G., Minniti, Z., Perrini, G., and Catalfo, A.: Photodegradation of anthracene and benzo [a] anthracene in polar and apolar media: new pathways of photodegradation, Polycycl. Aromat. Comp., 34, 263–279, 2014.

Lin, P., Rincon, A. G., Kalberer, M., and Yu, J. Z.: Elemental composition of HULIS in the Pearl River Delta Region, China: results inferred from positive and negative electrospray high resolution mass spectrometric data, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 7454–7462, https://doi.org/10.1021/es300285d, 2012.

Lohmann, R., Gioia, R., Jones, K. C., Nizzetto, L., Temme, C., Xie, Z., Schulz-Bull, D., Hand, I., Morgan, E., and Jantunen, L. J. E. S.: Organochlorine pesticides and PAHs in the surface water and atmosphere of the North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 5633–5639, 2009.

Ma, Y., Xie, Z., Yang, H., Möller, A., Halsall, C., Cai, M., Sturm, R., and Ebinghaus, R.: Deposition of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the North Pacific and the Arctic, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 5822–5829, 2013.

Ma, Y., Xu, X., Song, W., Geng, F., and Wang, L.: Seasonal and diurnal variations of particulate organosulfates in urban Shanghai, China, Atmos. Environ., 85, 152–160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.12.017, 2014.

Martins-Costa, M. T., Anglada, J. M., Francisco, J. S., and Ruiz-Loìpez, M. F.: Photochemistry of SO2 at the air–water interface: a source of OH and HOSO radicals, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 140, 12341–12344, 2018.

McLean, A. and Chandler, G.: Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z=11–18, J. Chem. Phys., 72, 5639–5648, 1980.

Mekic, M., Zeng, J., Jiang, B., Li, X., Lazarou, Y. G., Brigante, M., Herrmann, H., and Gligorovski, S.: Formation of Toxic Unsaturated Multifunctional and Organosulfur Compounds From the Photosensitized Processing of Fluorene and DMSO at the Air-Water Interface, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019jd031839, 2020a.

Mekic, M., Zeng, J., Zhou, W., Loisel, G., Jin, B., Li, X., Vione, D., and Gligorovski, S.: Ionic Strength Effect on Photochemistry of Fluorene and Dimethylsulfoxide at the Air–Sea Interface: Alternative Formation Pathway of Organic Sulfur Compounds in a Marine Atmosphere ACS Earth Space Chem., 4, 1029–1038, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00059, 2020b.

Monge, M. E., George, C., D'Anna, B., Doussin, J.-F., Jammoul, A., Wang, J., Eyglunent, G., Solignac, G., Daele, V., and Mellouki, A.: Ozone formation from illuminated titanium dioxide surfaces, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 132, 8234–8235, 2010.

Ning, A., Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Li, Z., Zhang, Y., Xu, Y., and Ge, M.: A molecular-scale study on the role of methanesulfinic acid in marine new particle formation, Atmos. Environ., 227, 117378, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117378, 2020.

Nizkorodov, S. A., Laskin, J., and Laskin, A.: Molecular chemistry of organic aerosols through the application of high resolution mass spectrometry, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 13, 3612–3629, 2011.

Oppenheimer, C., Francis, P., Burton, M., Maciejewski, A., and Boardman, L.: Remote measurement of volcanic gases by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Appl. Phys. B-Lasers O., 67, 505–515, https://doi.org/10.1007/s003400050536, 1998.

Otto, S., Streibel, T., Erdmann, S., Klingbeil, S., Schulz-Bull, D., and Zimmermann, R.: Pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry with electron-ionization or resonance-enhanced-multi-photon-ionization for characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Baltic Sea, Mar. Pollut. Bull., 99, 35–42, 2015.

Passananti, M., Kong, L., Shang, J., Dupart, Y., Perrier, S., Chen, J., Donaldson, D. J., and George, C.: Organosulfate Formation through the Heterogeneous Reaction of Sulfur Dioxide with Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Long-Chain Alkenes, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 55, 10336–10339, 2016.

Pérez-Carrera, E., León, V. M. L., Parra, A. G., and González-Mazo, E.: Simultaneous determination of pesticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls in seawater and interstitial marine water samples, using stir bar sorptive extraction–thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, J. Chromatogr. A, 1170, 82–90, 2007.

Perraud, V., Horne, J. R., Martinez, A. S., Kalinowski, J., Meinardi, S., Dawson, M. L., Wingen, L. M., Dabdub, D., Blake, D. R., Gerber, R. B., and Finlayson-Pitts, B. J.: The future of airborne sulfur-containing particles in the absence of fossil fuel sulfur dioxide emissions, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, 13514–13519, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510743112, 2015.

Richards, S., Rudd, J., and Kelly, C.: Organic volatile sulfur in lakes ranging in sulfate and dissolved salt concentration over five orders of magnitude, Limnol. Oceanogr., 39, 562–572, 1994.

Richards-Henderson, N. K., Goldstein, A. H., and Wilson, K. R.: Sulfur dioxide accelerates the heterogeneous oxidation rate of organic aerosol by hydroxyl radicals, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 50, 3554–3561, 2016.

Ridgeway, R. G., Thornton, D. C., and Bandy, A. R.: Determination of trace aqueous dimethylsulfoxide concentrations by isotope dilution gas chromatography/mass spectrometry: Application to rain and sea water, J. Atmos. Chem., 14, 53–60, 1992.

Riva, M., Tomaz, S., Cui, T., Lin, Y. H., Perraudin, E., Gold, A., Stone, E. A., Villenave, E., and Surratt, J. D.: Evidence for an unrecognized secondary anthropogenic source of organosulfates and sulfonates: gas-phase oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the presence of sulfate aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 6654–6664, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b00836, 2015.

Riva, M., Da Silva Barbosa, T., Lin, Y.-H., Stone, E. A., Gold, A., and Surratt, J. D.: Chemical characterization of organosulfates in secondary organic aerosol derived from the photooxidation of alkanes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11001–11018, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11001-2016, 2016.

Rosati, B., Christiansen, S., de Jonge, R. W., Roldin, P., Jensen, M. M., Wang, K., Moosakutty, S. P., Thomsen, D., Salomonsen, C., Hyttinen, N., Elm, J., Feilberg, A., Glasius, M., and Bilde, M.: New Particle Formation and Growth from Dimethyl Sulfide Oxidation by Hydroxyl Radicals, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 801–811, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00333, 2021.

Schobesberger, S., Junninen, H., Bianchi, F., Lonn, G., Ehn, M., Lehtipalo, K., Dommen, J., Ehrhart, S., Ortega, I. K., Franchin, A., Nieminen, T., Riccobono, F., Hutterli, M., Duplissy, J., Almeida, J., Amorim, A., Breitenlechner, M., Downard, A. J., Dunne, E. M., Flagan, R. C., Kajos, M., Keskinen, H., Kirkby, J., Kupc, A., Kurten, A., Kurten, T., Laaksonen, A., Mathot, S., Onnela, A., Praplan, A. P., Rondo, L., Santos, F. D., Schallhart, S., Schnitzhofer, R., Sipila, M., Tome, A., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Vehkamaki, H., Wimmer, D., Baltensperger, U., Carslaw, K. S., Curtius, J., Hansel, A., Petaja, T., Kulmala, M., Donahue, N. M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Molecular understanding of atmospheric particle formation from sulfuric acid and large oxidized organic molecules, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 17223–17228, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1306973110, 2013.

Seidel, M., Manecki, M., Herlemann, D. P., Deutsch, B., Schulz-Bull, D., Jürgens, K., and Dittmar, T.: Composition and transformation of dissolved organic matter in the Baltic Sea, Front. Earth Sci., 5, 31, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2017.00031, 2017.

Shang, J., Passananti, M., Dupart, Y., Ciuraru, R., Tinel, L., Rossignol, S. p., Perrier, S. B., Zhu, T., and George, C.: SO2 Uptake on oleic acid: A new formation pathway of organosulfur compounds in the atmosphere, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 3, 67–72, 2016.

Smith, S. J., Pitcher, H., and Wigley, T. M. L.: Global and regional anthropogenic sulfur dioxide emissions, Global Planet. Change, 29, 99–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0921-8181(00)00057-6, 2001.

Staudt, S., Kundu, S., Lehmler, H.-J., He, X., Cui, T., Lin, Y.-H., Kristensen, K., Glasius, M., Zhang, X., Weber, R. J., Surratt, J. D., and Stone, E. A.: Aromatic organosulfates in atmospheric aerosols: Synthesis, characterization, and abundance, Atmos. Environ., 94, 366–373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.05.049, 2014.

Stortini, A., Martellini, T., Del Bubba, M., Lepri, L., Capodaglio, G., and Cincinelli, A.: n-Alkanes, PAHs and surfactants in the sea surface microlayer and sea water samples of the Gerlache Inlet sea (Antarctica), Microchem. J., 92, 37–43, 2009.

Styler, S. A., Loiseaux, M.-E., and Donaldson, D. J.: Substrate effects in the photoenhanced ozonation of pyrene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 1243–1253, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-1243-2011, 2011.

Tao, S., Lu, X., Levac, N., Bateman, A. P., Nguyen, T. B., Bones, D. L., Nizkorodov, S. A., Laskin, J., Laskin, A., and Yang, X.: Molecular characterization of organosulfates in organic aerosols from Shanghai and Los Angeles urban areas by nanospray-desorption electrospray ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 10993–11001, 2014.

Urbanski, S., Stickel, R., and Wine, P.: Mechanistic and kinetic study of the gas-phase reaction of hydroxyl radical with dimethyl sulfoxide, J. Phys. Chem. A, 102, 10522–10529, 1998.

Vácha, R., Jungwirth, P., Chen, J., and Valsaraj, K.: Adsorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at the air–water interface: Molecular dynamics simulations and experimental atmospheric observations, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 8, 4461–4467, 2006.

Valavanidis, A., Vlachogianni, T., Triantafillaki, S., Dassenakis, M., Androutsos, F., and Scoullos, M.: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface seawater and in indigenous mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) from coastal areas of the Saronikos Gulf (Greece), Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci., 79, 733–739, 2008.

von Sonntag, C., Dowideit, P., Fang, X., Mertens, R., Pan, X., Schuchmann, M. N., and Schuchmann, H.-P.: The fate of peroxyl radicals in aqueous solution, Water Sci. Technol., 35, 9–15, 1997.

Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Jiang, J., Zhou, W., Wang, B., He, K., Duan, F., Zhang, Q., Philip, S., and Xie, Y.: Enhanced sulfate formation during China's severe winter haze episode in January 2013 missing from current models, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 119, 10425–10440, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jd021426, 2014.

Wang, Y., Mekic, M., Li, P., Deng, H., Liu, S., Jiang, B., Jin, B., Vione, D., and Gligorovski, S.: Ionic Strength Effect Triggers Brown Carbon Formation through Heterogeneous Ozone Processing of Ortho-Vanillin, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 4553–4564, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c00874, 2021.

Weigend, F.: Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 8, 1057–1065, 2006.

Weigend, F. and Ahlrichs, R.: Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 7, 3297–3305, 2005.

Wilkinson, F., Helman, W. P., and Ross, A. B.: Rate constants for the decay and reactions of the lowest electronically excited singlet state of molecular oxygen in solution. An expanded and revised compilation, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 24, 663–677, 1995.

Yassine, M. M., Harir, M., Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E., and Schmitt-Kopplin, P.: Structural characterization of organic aerosol using Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: aromaticity equivalent approach, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom., 28, 2445–2454, 2014.

Zhang, L., Kuniyoshi, I., Hirai, M., and Shoda, M.: Oxidation of dimethyl sulfide byPseudomonas acidovorans DMR-11 isolated from peat biofilter, Biotechnol. Lett, 13, 223–228, 1991.

Zhang, M., Gao, W., Yan, J., Wu, Y., Marandino, C. A., Park, K., Chen, L., Lin, Q., Tan, G., and Pan, M.: An integrated sampler for shipboard underway measurement of dimethyl sulfide in surface seawater and air, Atmos. Environ., 209, 86–91, 2019.

Zhang, S. H., Yang, G. P., Zhang, H. H., and Yang, J.: Spatial variation of biogenic sulfur in the south Yellow Sea and the East China Sea during summer and its contribution to atmospheric sulfate aerosol, Sci. Total Environ., 488–489, 157–167, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.074, 2014.

Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Gray, B. A., Gu, D., Mauldin, L., Cantrell, C., and Bandy, A.: Surface and free tropospheric sources of methanesulfonic acid over the tropical Pacific Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 5239–5245, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014gl060934, 2014.

Zhao, H., Jiang, X., and Du, L.: Contribution of methane sulfonic acid to new particle formation in the atmosphere, Chemosphere, 174, 689–699, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.02.040, 2017.

Zhao, Y. and Truhlar, D. G.: The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals, Theor. Chem. Acc., 120, 215–241, 2008.

Zhou, S., Hwang, B. C. H., Lakey, P. S. J., Zuend, A., Abbatt, J. P. D., and Shiraiwa, M.: Multiphase reactivity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is driven by phase separation and diffusion limitations, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 11658–11663, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902517116, 2019.

Zhu, M., Jiang, B., Li, S., Yu, Q., Yu, X., Zhang, Y., Bi, X., Yu, J., George, C., and Yu, Z.: Organosulfur Compounds Formed from Heterogeneous Reaction between SO2 and Particulate-Bound Unsaturated Fatty Acids in Ambient Air, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 6, 318–322, 2019.