the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The positive effect of formaldehyde on the photocatalytic renoxification of nitrate on TiO2 particles

Yuhan Liu

Xuejiao Wang

Jing Shang

Weiwei Xu

Mengshuang Sheng

Chunxiang Ye

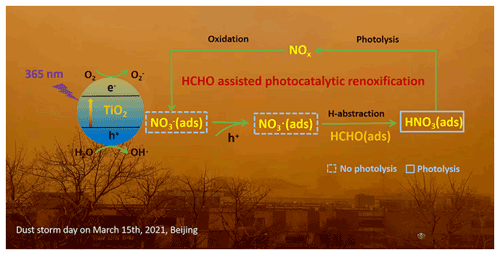

Renoxification is the process of recycling NO HNO3 into NOx under illumination and is mostly ascribed to the photolysis of nitrate. TiO2, a typical mineral dust component, is able to play a photocatalytic role in the renoxification process due to the formation of NO3 radicals; we define this process as “photocatalytic renoxification”. Formaldehyde (HCHO), the most abundant carbonyl compound in the atmosphere, may participate in the renoxification of nitrate-doped TiO2 particles. In this study, we established a 400 L environmental chamber reaction system capable of controlling 0.8 %–70 % relative humidity at 293 K with the presence of 1 or 9 ppm HCHO and 4 wt % nitrate-doped TiO2. The direct photolyses of both nitrate and NO3 radicals were excluded by adjusting the illumination wavelength so as to explore the effect of HCHO on the “photocatalytic renoxification”. It was found that NOx concentrations can reach up to more than 100 ppb for nitrate-doped TiO2 particles, while almost no NOx was generated in the absence of HCHO. Nitrate type, relative humidity and HCHO concentration were found to influence NOx release. It was suggested that substantial amounts of NOx were produced via the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway, where TiO2 worked for converting “NO” to “NO3• ”, that HCHO participated in the transformation of “NO3• ” to “HNO3” through hydrogen abstraction, and that “HNO3” photolysis answered for mass NOx release. So, HCHO played a significant role in this “photocatalytic renoxification” process. These results were found based on simplified mimics for atmospheric mineral dust under specific experimental conditions, which might deviate from the real situation but illustrated the potential of HCHO to influence nitrate renoxification in the atmosphere. Our proposed reaction mechanism by which HCHO promotes photocatalytic renoxification is helpful for deeply understanding atmospheric photochemical processes and nitrogen cycling and could be considered for better fitting atmospheric model simulations with field observations in some specific scenarios.

- Article

(1456 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1777 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The levels of ozone (O3) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in the troposphere can be promoted by nitrogen oxides (NOx= NO + NO2), such that NOx plays an important role in the formation of secondary aerosols and atmospheric oxidants (Platt et al., 1980; Stemmler et al., 2006; Harris et al., 1982; Finlayson-Pitts and Pitts, 1999). NOx can be converted into nitric acid (HNO3) and nitrate (NO) through a series of oxidation and hydrolysis reactions and is eventually removed from the atmosphere through subsequent wet or dry deposition (Dentener and Crutzen, 1993; Goodman et al., 2001; Monge et al., 2010; Bedjanian and El Zein, 2012). However, comparisons of observations and modeling results for the marine boundary layer, land, and free troposphere (Read et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2009; Seltzer et al., 2015) have shown an underestimation of HNO3 or NO content, NOx abundance, and NOx HNO3 ratios, indicating the presence of a new, rapid NOx circulation pathway (Ye et al., 2016b; Reed et al., 2017). Some researchers have suggested that deposited NO and HNO3 can be recycled back to gas-phase NOx under illumination via the renoxification process (Schuttlefield et al., 2008; Romer et al., 2018; Bao et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2021). Photolytic renoxification occurs under light with a wavelength of < 350 nm through the photolysis of NO HNO3 adsorbed on the solid surface to generate NOx. Notably, the photolysis of NO HNO3 is reported to occur at least 2 orders of magnitude faster on different solid surfaces (natural or artificial) or on aerosols than in the gas phase (Ye et al., 2016a; Zhou et al., 2003; Baergen and Donaldson, 2013). Several recent studies have shown that renoxification has important atmospheric significance (Deng et al., 2010; Kasibhatla et al., 2018; Romer et al., 2018; Alexander et al., 2020), providing the atmosphere with a new source of photochemically reactive nitrogen species, i.e., HONO or NOx, resulting in the production of more photooxidants such as O3 or •OH (Ye et al., 2017), which further oxidize volatile organic compounds (VOCs), leading to the formation of more chromophores and thereby affecting the photochemical process (Bao et al., 2020).

Renoxification processes have recently been observed on different types of atmospheric particles, such as urban grime and mineral dust (Ninneman et al., 2020; Bao et al., 2018; Baergen and Donaldson, 2013; Ndour et al., 2009). Atmospheric titanium dioxide (TiO2) is mainly derived from windblown mineral dust, with mass mixing ratios ranging from 0.1 % to 10 % (Chen et al., 2012). TiO2 is widely used in industrial processes and building exteriors for its favorable physical and chemical properties. Titanium and nitrate ions have been found to coexist in atmospheric particulates in different regions worldwide (Sun et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012), and the NO (NO TiO2) mass percentage of total suspended particulate matter (TSP) during dust storms can be lower than 20 % (Sun et al., 2005). In this case, nitrate-coated TiO2 (NO–TiO2) aerosols containing TiO2 as the main body can, to some extent, be used to represent the real situation under sandstorms. TiO2 is a semiconductor metal oxide that can facilitate the photolysis of nitrate and the release of NOx due to its photocatalytic activity (Ndour et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2012; Verbruggen, 2015; Schwartz-Narbonne et al., 2019). Under UV light, TiO2 generates electron-hole pairs in the conduction and valence bands, respectively (Linsebigler et al., 1995). Nitrate ions adsorbed at the oxide surface react with the photogenerated holes (h+) to form nitrate radicals (NO3•), which are subsequently photolyzed to NOx, mainly under visible illumination (Schuttlefield et al., 2008; George et al., 2015; Schwartz-Narbonne et al., 2019). Thus, the renoxification of NO is faster on TiO2 than on other oxides in mineral dust aerosols such as SiO2 or Al2O3 (Lesko et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2021). In this study, we refer to renoxification involving h+ and NO as photocatalytic renoxification based on the photocatalytic properties of TiO2.

Many previous studies have focused mainly on particulate nitrate–NOx photochemical cycling reactions despite the potential impact of other reactant gases in the atmosphere. Formaldehyde (HCHO), the most abundant carbonyl compound in the atmosphere, can reach as high as 0.4 ppm in some specific situations (particularly in some indoor air or in cities with high traffic density) (Wilbourn et al., 1995; Salthammer, 2019). HCHO can react with NO3• at night via hydrogen abstraction reactions to form HNO3 (Atkinson, 1991). Our previous study showed that the degradation rate of HCHO was faster on NO–TiO2 aerosols than on TiO2 particles, perhaps as a result of HCHO oxidation by NO3• (Shang et al., 2017). To date, no studies have reported the effect of HCHO on photocatalytic renoxification. Adsorbed HCHO would react with NO3• generated on the NO–TiO2 aerosol surface, thus altering the surface nitrogenous species and renoxification process. The present study is the first to explore the combined effect of HCHO and photocatalytic TiO2 particles on the renoxification of nitrate. The wavelengths of the light sources were adjusted to exclude photolytic renoxification while making photocatalytic renoxification available for better elucidating the reaction mechanism. We investigated the effects of various influential factors – including nitrate type, nitrate content, RH, and initial HCHO concentration – to understand the atmospheric renoxification of nitrate in greater detail.

2.1 Environmental chamber setup

Details of the experimental apparatus and protocol used in the current study have been previously described (Shang et al., 2017). Briefly, the main body of the environmental chamber is a 400 L polyvinyl fluoride (PVF) bag filled with synthetic air (high purity N2 (99.999 %) mixed with high purity O2 (99.999 %) with a ratio of 79:21 by volume; Beijing Huatong Jingke Gas Chemical Co.). The chamber is capable of temperature (∼293 K) and relative humidity (0.8 %–70 %) control using a water bubbler and air conditioners, respectively. The chamber is equipped with two light sources, both with a central wavelength of 365 nm. One is a set of 36 W tube lamps with a main spectrum of 320–400 nm and a small amount of 480–600 nm visible light (Fig. S1a). The other is a set of 12 W LED lamps with a narrow main spectrum of 350–390 nm (Fig. S1b). The light intensities for the tube and LED lamp at 365 nm were 300 and 200 µW cm−2, respectively, as measured in the middle of the chamber. NOx concentrations at the outlet of the chamber were monitored by a chemiluminescence NOx analyzer (ECOTECH, EC9841B). HCHO was generated by thermolysis of paraformaldehyde at 70 ∘C and detected via an acetyl acetone spectrophotometric method using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (PERSEE, T6) or a fluorescence spectrophotometer (THERMO, Lumina), depending on different initial HCHO concentrations. The particle size distribution was measured by a scanning nanoparticle spectrometer (HCT, SNPS-20). Electron spin resonance (Nuohai Life Science, MiniScope MS 5000) was used to measure •OH on the surface of the particles. A 5,5-dimethl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DPMO, Enzo) was used as the capture agent. Fifty µL particle-containing suspension mixed with 50 µL DMPO (concentration of 200 µM) was loaded in a 1 mm capillary. Four 365 nm LED lamps were placed side by side, vertically, at a distance of about 1 cm from the capillary, and the measurement was carried out after 1 min of irradiation. The modulation frequency was 100 kHz; the modulation amplitude was 0.2 mT; the microwave power was 10 mW; and the sweep time was 60 s.

2.2 Nitrate–TiO2 composite samples

In our experiments, two nitrate salts – potassium nitrate (AR, Beijing Chemical Works Co., Ltd) or ammonium nitrate (AR, Beijing Chemical Works Co., Ltd) – were composited with pure TiO2 (≥ 99.5 %, Degussa AG) powder or TiO2 (1 wt %) SiO2 mixed powder to prepare NO–TiO2 or NO–TiO2 (1 wt %) SiO2 samples; 250 mg TiO2 was simply mixed in the nitrate solutions at the desired mass mixing ratio (with nitrate content of 4 wt %) to obtain a mash. The mash was dried at 90 ∘C and then ground carefully for 30 min. A series of samples with different amounts of nitrate were prepared, and diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements were made to test their homogeneity. Figure S2 shows the DRIFTS spectra of these KNO3–TiO2 composites, of which the 1760 cm−1 peak is one of the typical vibrating peaks of nitrate (Aghazadeh, 2016; Maeda et al., 2011). The ratio value of the peak area from 1730–1790 cm−1 for 1 wt %, 4 wt %, 32 wt %, 80 wt % composited samples is , which is very close to that of theoretical value, proving that the samples were uniformly mixed. SiO2 (AR, Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd.) with no optical activity was also chosen for comparison, and samples of KNO3-SiO2 and KNO3–TiO2 (1 wt %) SiO2 samples with a potassium nitrate content of 4 wt % were prepared. The blank 250 mg TiO2 sample was solved in pure water, using the same procedure as mentioned above. Four wt % HNO3–TiO2 composite particles were prepared for comparison. Concentrated nitric acid (AR, Beijing Chemical Works Co., Ltd) was diluted to 1 M, and 250 mg TiO2 was added to the nitric acid solution and stirred evenly. A layer of aluminum foil was used to cover the surface of the HNO3–TiO2 homogenate, which was then dried naturally in the room and then ground for use. We also selected Arizona Test Dust (ATD, Powder Technology Inc.), whose chemical composition and weight percentage were shown in Table S1, as a substitute of NO TiO2 to investigate the “photocatalytic renoxification” process of nitrate and the positive effect of HCHO.

2.3 Environmental chamber experiments

For the chamber operation, we completely evacuated the chamber after every experiment; we then cleaned the chamber walls with deionized water and dried them by flushing the chamber with ultra-zero air to remove any particles or gases that had collected on the chamber walls. The experiments carried out in the environmental chamber can be divided into two categories according to whether HCHO was involved or not. (1) No HCHO involvement in the reaction. The PVF bag was inflated by 260 L synthetic air, and then 75 mg particles were instantly sprayed into the chamber by a transient high-pressure airflow. As shown in Fig. S3, the particle number concentration of the KNO3–TiO2 or TiO2 samples decreased rapidly owing to the wall effect, including the possible electrostatic adsorption of the particles by the environmental chamber. The size distributions of the KNO3–TiO2 and TiO2 samples were similar, with both becoming stable after about 60 min. The peak number concentration was averaged between 3991 and 3886 particle cm−3 during the illumination period for the KNO3–TiO2 and TiO2 samples, respectively, indicating that the repeatability of the introduction of particles into the chamber is good. This can be attributed to the strict cleaning of the chamber and the same operation of each batch experiment. (2) With the participation of HCHO. The PVF bag was inflated by 125 L synthetic air followed by the introduction of HCHO, and then the chamber was filled up with zero air to about 250 L. In order to know the HCHO adsorption before and after the particles' introduction, we conducted a conditional experiment in the dark. It can be seen from Fig. S4 that it took about 90 min for the concentration of HCHO to reach stability and be sustained. Then, 75 mg TiO2 or NO TiO2 powders were introduced instantly, and the concentration of HCHO decreased upon the introduction. It took about 60 min for HCHO to reach its second adsorption equilibrium and for the concentration of HCHO to remain stable for several hours in the dark. Therefore, for the irradiation experiments, the particles were injected at 90 min after HCHO's introduction, and the lamps were turned on at 60 min after the particle's introduction.

To determine the background value of NOx in the reaction system, four blank experiments were carried out under illumination without nitrate: “synthetic air”, “synthetic air + TiO2”, “synthetic air + HCHO”, and “synthetic air + HCHO + TiO2”. In the blank experiments of “synthetic air” and “synthetic air + TiO2”, the NOx concentration remained stable during 180 min illumination, and the concentration change was no more than 0.5 ppb (Fig. S5a). Therefore, the environmental chamber, the synthetic air, and the surface of TiO2 particles were thought to be relatively clean, and there was no generation and accumulation of NOx under illumination. When HCHO was introduced into the environmental chamber, NOx accumulated ∼2 ppb in 120 min with or without TiO2 particles (Fig. S5b). Compared with the blank experiment results when there was no HCHO, NOx might come from the generation process of HCHO (impurities in paraformaldehyde). However, considering the high concentration level of NOx produced in the NO–TiO2 system containing HCHO under the same conditions in this study (see later in Fig. 2), the NOx generated in this blank experiment can be negligible.

3.1 The positive effect of TiO2 on the renoxification process

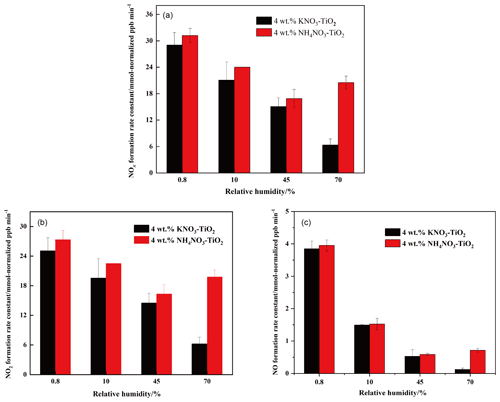

We investigated the photocatalytic role of TiO2 on renoxification. The light source was two 365 nm tube lamps containing small amounts of 400–600 nm visible light; this setup was suitable for exciting TiO2 and the photolysis of available nitrate radicals. Raw NOx data measured in the chamber under dark and illuminated conditions for 4 wt % KNO3-SiO2 and 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2 (1 wt %) SiO2 are shown in Fig. 1. The ratio of 1 wt % TiO2 to SiO2 corresponds to their ratio in sand and dust particles. We observed no NOx in the KNO3-SiO2 sample under darkness or illumination, indicating very weak direct photolysis of nitrate under our 365 nm tube-lamp illumination conditions. However, when the sample containing TiO2 SiO2 was illuminated, NOx continually accumulated in the chamber. This finding confirms that NOx production arising from photodissociation of NO on TiO2 ,SiO2 was caused by the photocatalytic property of TiO2 (i.e., photocatalytic renoxification) and was not due to the direct photolysis of NO (photolytic renoxification).

Figure 1Effect of illumination on the release of NOx from 4 wt % KNO3-SiO2 and 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2(1 wt %) SiO2 at 293 K and 0.8 % of relative humidity. 365 nm tube lamps were used during the illumination experiments.

TiO2 can be excited by UV illumination to generate electron-hole pairs, and the h+ can react with adsorbed NO to produce NO3• (Ndour et al., 2009). Thus, in the present study, NO3• mainly absorbed visible light emitted from the tube lamps, which was subsequently photolyzed to NOxthrough Eqs. (3) and (4) (Wayne et al., 1991), which explains why NOx was observed in this study. Thus, we demonstrated that TiO2 can be excited at illumination wavelengths of ∼365 nm, even when then content was very low, and that NOx accumulated due to the production and further photolysis of NO3•. However, the production rate of NOx was very slow, reaching only 1.3 ppb during 90 min of illumination. This result may have been caused by the blocking effect of K+ on NO. K+ forms ion pairs with NO, and electrostatic repulsion between K+ and h+ prevents NO from combining with h+ to generate NO3• to a certain extent, thereby weakening the positive effect of TiO2 on the renoxification of KNO3 (Rosseler et al., 2013).

3.2 The synergistic positive effect of TiO2 and HCHO on the renoxification process

LED lamps with a wavelength range of 350–390 nm and no visible light were used to irradiate 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2 without generating NOx (NO2 and NO concentrations fluctuate within the error range of the instrument) (Fig. S5). TiO2 can be excited under this range of irradiation, producing NO3 radicals as discussed above. The lack of NOx generation indicates that neither nitrate photolysis nor NO3• photolysis occurred under 365 nm LED lamp illumination conditions. In addition, it has been shown that NO3• photolysis only occurs in visible light (Aldener et al., 2006). Therefore, the LED lamp setup was used in subsequent experiments to exclude the direct photolysis of both KNO3 and NO3• but to allow the excitation of TiO2. This approach allowed us to investigate the process of photocatalytic renoxification caused by HCHO in the presence of photogenerated NO3•.

Atmospheric trace gases can undergo photocatalytic reactions on the surface of TiO2 (Chen et al., 2012). As the illumination time increased, the concentration of HCHO showed a linear downward trend, which was found to fit zero-order reaction kinetics (Fig. S7). The zero-order reaction rate constants of HCHO on TiO2 and 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2 particles were and ppm min−1, respectively, which were much higher than that for gaseous HCHO photolysis (Shang et al., 2017). We suggested that the produced NO3• contributed to the enhanced uptake of HCHO. In the following study, the effect of HCHO on the photocatalytic renoxification of NO–TiO2 was explored.

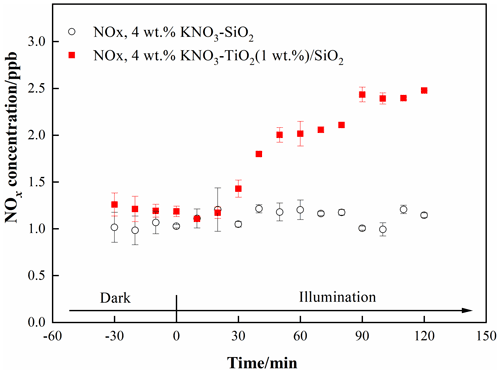

The variation in NOx concentrations within the chamber containing nitrate–TiO2 particles with or without HCHO is shown in Fig. 2. For 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2 particles, the NOx concentration began to increase upon irradiation in the presence of HCHO, reaching ∼ 3861 mmol normalized ppb (equivalent to 110 ppb) within 120 min. This result indicates that HCHO greatly promoted photocatalytic renoxification of KNO3 on the surfaces of TiO2 particles. This reaction process can be divided into two stages: a rapid increase within the first 60 min and a slower increase within the following 60 min, each consistent with zero-orde reaction kinetics. The slow stage is due to the photodegradation of HCHO on KNO3–TiO2 aerosols, which led to a decrease in its concentration, gradually weakening the positive effect. NOx is the sum of NO2 and NO, both of which showed a two-stage concentration increase (Fig. S8). The NO2 generation rate was nearly 6 times that of NO as compared to using the zero-order rate constant within 60 min (1.18 ppb min−1 NO2, R2= 0.96; 0.19 ppb min−1 NO, R2= 0.91). This burst-like generation of NOx can be ascribed to the reaction between generated NO3• and HCHO via hydrogen abstraction to form adsorbed nitric acid (HNO3(ads)) on TiO2 particles. We measured the pH of water extracts in NO–TiO2 systems with and without HCHO. It was found that the pH decreased by 1.7 % for KNO3–TiO2, suggesting the formation of acidic species such as HNO3(ads) in this study. Based on the analysis of the absorption cross section of HNO3 adsorbed on the fused silica surface, the HNO3(ads) absorption spectrum has been reported to be red-shifted compared to HNO3(g), extending from 350 to 365 nm, with a simultaneous cross-sectional increase (Du and Zhu, 2011). Therefore, HNO3(ads) was subjected to photolysis to produce NO2 and HONO (Eqs. 6–8) under the LED lamp used in this study. A previous study of HNO3 photolysis on the surface of Pyrex glass showed that the ratio of the formation rates of photolysis products was > 97 % at RH = 0 % (Zhou et al., 2003), suggesting that NOx is the main gaseous product under dry conditions. Thus, the effect of HONO on product distribution and NOx concentration was negligible in this study. Together, these results suggest that NO3• and HCHO generate HNO3(ads) on particle surfaces through hydrogen abstraction, which contributes to the substantial release of NOx via photolysis. This photocatalytic renoxification via the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway is important considering the high abundance of hydrogen donor organics in the atmosphere.

Figure 2Effect of formaldehyde on the renoxification processes of different nitrate-doped particles at 293 K and 0.8 % of relative humidity; 365 nm LED lamps were used during the illumination experiment. The initial concentration of HCHO was about 9 ppm.

To demonstrate the proposed HCHO mechanism and the photolysis contribution of HNO3 to NOx, we prepared an HNO3–TiO2 sample by directly dissolving TiO2 into dilute nitric acid. The formation of NOx on HNO3–TiO2 without HCHO under illumination was obvious and at a rate comparable with that on KNO3–TiO2 with HCHO (Fig. 2). The renoxification of HNO3–TiO2 particles was further enhanced following the introduction of HCHO. This is because HNO3 dissociates on particle surfaces to generate NO, such that HNO3 exists on TiO2 as both HNO3(ads) and NO(ads). Similarly, NO(ads) completed the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway, as described above, through the reaction process shown in Eqs. (2) to (8). The rates of NOx production from HNO3–TiO2 particles with and without HCHO were similar for the first 60 min (Fig. 2), mainly due to the direct photolysis of partial HNO3(ads). However, after 60 min, NOx was generated rapidly in the presence of HCHO, perhaps due to the dominant photocatalytic renoxification of NO(ads). These findings indicate that HCHO converts NO on particle surfaces into HNO3(ads) by reacting with NO3•, and then HNO3(ads) photolyzes at a faster rate to generate NOx, allowing HCHO to enhance the formation of NOx. Overall, the photocatalytic renoxification of NO–TiO2 particles affects atmospheric oxidation and the nitrogen cycle, and the presence of HCHO further enhances this impact.

Photocatalytic renoxification reactions occur on the surfaces of mineral dust due to the presence of semiconductor oxides with photocatalytic activity such as TiO2 (Ndour et al., 2009). In order to confirm this, we synthesized nitrate with inert SiO2 as a comparison. It can be seen from Fig. S9 that no NO2 formation was observed regardless of whether or not HCHO was present, indicating that photocatalytically active particle TiO2 is critical to the photocatalytic renoxification process. Furthermore, a kind of commercial mineral dust ATD was selected to study the effects of HCHO on this process. We detected •OH in irradiated pure TiO2 and ATD samples using the electron spin resonance (ESR) technique and found that, for ATD samples, the peak intensity of •OH generation was 40 % that of TiO2 samples (Fig. S10). •OH originates in the reaction of h+ with surface-adsorbed water (Ahmed et al., 2014). ATD contains semiconductor oxides such as TiO2 and Fe2O3 and is thought to exhibit photocatalytic properties affecting the renoxification of nitrate. The NO content of ATD is 4×1017 molecules m−2, which is ∼ 0.25 wt % of the total mass (Huang et al., 2015; Park et al., 2017). The NOx concentration changes observed in the environmental chamber demonstrated that HCHO promoted the renoxification of ATD particles (Fig. S11). This result suggests that mineral dust containing photocatalytic semiconductor oxides such as TiO2, Fe2O3, and ZnO can greatly promote the conversion of granular nitrate to NOx in the presence of HCHO.

3.3 Influential factors on the photocatalytic renoxification process

3.3.1 The influence of nitrate type

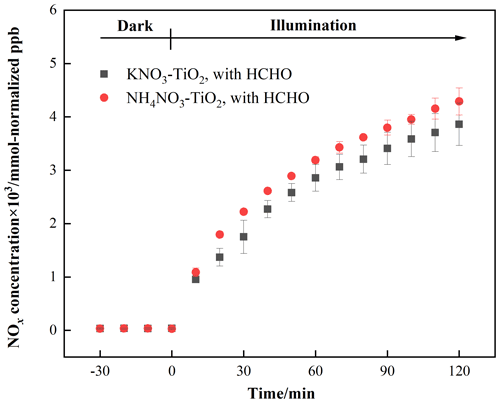

As discussed above, HNO3 and KNO3 undergo different renoxification processes on the surface of TiO2 under the same illumination conditions, suggesting that cations bound to NO significantly affect NOx production. Different types of cations coexist with nitrate ions in atmospheric particulate matter, among which ammonium ions (NH) are important water-soluble ions that can be higher in content than K+ in urban fine particulate matter (Zhou et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), especially in heavily polluted cities (Tian et al., 2020). Equal amounts of 4 wt % NH4NO3–TiO2 particles were introduced into the chamber and illuminated under the same conditions. Similar to Fig. 2, millimole normalized ppb was used in order to compare the amount of NOx released for different kinds of nitrate with the same percentage weight. It can be seen that HCHO had a much stronger positive effect on the release of NOx over NH4NO3–TiO2 particles (Fig. 3), which may be ascribed to NH. Combined with the results of NH4NO3–TiO2 and KNO3–TiO2 particles, it seems that the affinity rather than electrostatic repulsion should be the primary effect of cations on the production of NOx. On substrates without photocatalytic activity, such as SiO2 and Al2O3, NH4NO3 cannot generate NOx, such that NOx production depends on the effect of TiO2 (Ma et al., 2021). The h+ generated by TiO2 excitation reacts with adsorbed H2O to produce •OH (Eq. 9), which gradually oxidizes NH to NO (Eq. 10). In our previous study, we demonstrated that irradiated (NH4)2SO4–TiO2 samples had lower NH and NO peaks (Shang et al., 2017). Therefore, more NO participated in the photocatalytic renoxification process via the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway to generate NOx. Moreover, the results without HCHO are shown in Fig. S12. Both NH4NO3–TiO2 particles and KNO3–TiO2 particles produced almost no NOx, indicating the importance of HCHO for renoxification to occur. Due to the high content of NH4NO3 in atmospheric particulate matter, the positive effect of HCHO on the photocatalytic renoxification process may have some impact on the concentrations of NOx and other atmospheric oxidants.

Figure 3Effect of formaldehyde on the renoxification processes of 4 wt % NH4NO3–TiO2 and 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2 particles at 293 K and 0.8 % of relative humidity; 365 nm LED lamps were used during the irradiation experiment. The initial concentration of HCHO was about 9 ppm.

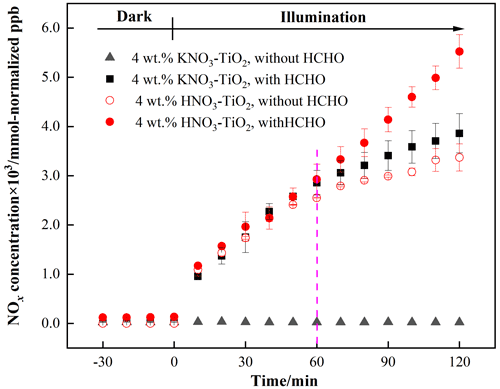

3.3.2 The influence of relative humidity

Water on particle surfaces can participate directly in the heterogeneous reaction process. As shown in Eq. (9), H2O can be captured by h+ to generate •OH with strong oxidizability in photocatalytic reactions. The first-order photolysis rate constant of NO on TiO2 particles decreases by an order of magnitude from (5.7±0.1) × 10−4 s−1 on dry surfaces to (7.1±0.8) × 10−5 s−1 when nitrate is coadsorbed with water above monolayer coverage (Ostaszewski et al., 2018). We explored the positive effect of HCHO on the NO–TiO2 particle photocatalytic renoxification at different RH levels; the results are shown in Fig. 4a. For KNO3–TiO2 particles, the rate of NOx production decreased as the RH of the environmental chamber increased, indicating that increased water content in the gas phase hindered photocatalytic renoxification for two reasons: H2O competes with NO for h+ on the surface of TiO2 to generate •OH, reducing the generation of NO3•, and competitive adsorption between H2O and HCHO causes the generated •OH to compete with NO3• for HCHO, hindering the formation of HNO3(ads) on particle surfaces. Moreover, it is also possible that the loss of NOx on the wall increases under high humidity conditions, resulting in a decrease in its concentration. This competitive process also occurs on the surface of NH4NO3–TiO2 particles, but at RH = 70 %, the NOx generation rate constant is slightly higher. The deliquescent humidity of NH4NO3 at 298 K is ∼ 62 %, such that NH4NO3 had already deliquesced at RH = 70 %, forming an NH NH3-NO liquid system on the particle surfaces. This quasi-liquid phase improved the dispersion of TiO2 in NH4NO3, resulting in greater NOx release. The deliquescent humidity of KNO3–TiO2 was > 90 % (2009), such that no phase change occurred at RH = 70 %, and the renoxification reaction rate retained a downward trend. In the presence of H2O, in addition to the NO-NO3•-HNO3 pathway observed in this study, there are a variety of HNO3 generation paths, such as the hydrolysis of N2O5 via the NO2-N2O5-HNO3 pathway (Brown et al., 2005), the oxidation of NO2 by •OH (Burkholder et al., 1993), and the reaction of NO3• with H2O (Schutze and Herrmann, 2005), all of which require further consideration and study.

Figure 5Positive role of HCHO on the photocatalytic renoxification of nitrate–TiO2 composite particles via the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway.

The formation rates of NO and NO2 are shown in Fig. 4b and c, respectively. NO2 was the main product of surface HNO3 photolysis. Under humid conditions, generated NO2(ads) continued to react with H2O adsorbed on the surface to form HONO(ads). HONO was desorbed from the surface and released into the gas phase (Zhou et al., 2003; Bao et al., 2018; Pandit et al., 2021), providing gaseous HONO to the reaction system. Because the NOx concentration remained high, the effect of HONO on NOx analyzer results was negligible (Shi et al., 2021). As NO2 can form NO with e−, a reverse reaction also occurred between NO and HONO in the presence of H2O (Ma et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2021). Therefore, the increase in H2O increased the proportion of HONO in the nitrogen-containing products, such that the NOx generation rate decreased as RH increased. Comparing Fig. 4b and c shows that, as RH increased, the NO production rate constant decreased more than that of NO2. HONO and NO2 generated by the photolysis of HNO3(ads) decreased accordingly, i.e., the NO source decreased. However, generated NO2 and NO underwent photocatalytic oxidation on the surface of TiO2, and NO photodegradation was more significant under the same conditions (Hot et al., 2017). Generally, a certain amount of HONO will be generated during the reaction between HCHO and NO–TiO2 particles when RH is high, which affects the concentrations of atmospheric •OH, NOx, and O3. This process is more likely to occur in summer due to high RH and light intensity affecting atmospheric oxidation. In drier winters or dusty weather, when TiO2 content is high, HCHO greatly promotes the photocatalytic renoxification of NO–TiO2 particles, thereby releasing more NOx into the atmosphere, affecting the global atmospheric nitrogen budget. Thus, regardless of the seasonal and regional changes, renoxification has significant practical importance.

3.3.3 The influence of initial HCHO concentrations

To explore whether HCHO promotes nitrate renoxification at natural concentration levels, we reduced the initial concentration of HCHO in the environmental chamber by a factor of 10 to ∼ 1.0 ppm. The positive effect of HCHO on the photocatalytic renoxification of KNO3–TiO2 particles was clearly weakened, with the NO2 concentration first increasing and then decreasing, and the NO concentration remaining stable (Fig. S13). The HCHO concentration decreased due to its consumption during the reaction, making its positive effect decline quickly. The photocatalytic oxidation reaction between NOx and photogenerated reactive oxygen species (ROS) on the TiO2 surface further decreased the NOx concentration. Photocatalytic oxidation of NOx by ROS on TiO2 particles occurred at an HCHO concentration of 9 ppm, but the positive effect of HCHO remained dominant. Thus, no decrease in NOx concentration was observed within 120 min in our experiments.

The concentration of HCHO in the atmosphere is relatively low, with a balance between the photocatalytic oxidation decay of NOx and the release of NOx via photocatalytic renoxification. The mutual transformation between particulate NO and gaseous NOx is more complex. The effect of low-concentration HCHO on the renoxification of NO–TiO2 particles requires further investigation. However, many types of organics provide hydrogen atoms in the atmosphere, including alkanes (e.g., methane and n-hexane), aldehydes (e.g., acetaldehyde), alcohols (e.g., methanol and ethanol), and aromatic compounds (e.g., phenol) that react with NO3• to produce nitric acid (Atkinson, 1991). These organics, together with HCHO, play similar positive roles in photocatalytic renoxification and, therefore, influence NOx concentrations.

Nitric acid and nitrate are not only the final sink of NOx in the atmosphere but are also among its important sources. NOx generated from nitrate through renoxification is easily overlooked. The renoxification of nitrate on the surface of TiO2 particles can be divided into photolytic renoxification and photocatalytic renoxification. The photocatalytic performance of TiO2 promotes the renoxification process, which explains the influence of semiconducting metal oxide components on atmospheric mineral particles during the renoxification of nitrate. Although most previous studies have focused on solid-phase nitrate renoxification, our exploration of the roles of HCHO in this study will allow us to examine complex real-world pollution scenarios, in which multiple atmospheric pollutants coexist, as well as the effects of organic pollutants on the renoxification process. Atmospheric HCHO is taken up at the surface of particulate matter, accounting for up to ∼ 50 % of its absorption (Li et al., 2014), such that the heterogeneous participation of HCHO during renoxification is important. This study is the first to report that HCHO has a positive effect on the photocatalytic renoxification of nitrate on TiO2 particles via the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway (Fig. 5), further increasing the release of NOx and other nitrogen-containing active species, which in turn affects the photochemical cycle of HOx radicals in the atmosphere and the formation of important atmospheric oxidants such as O3. Although the response to the real situation will be biased in the case of high concentrations of HCHO, as in our experiment, the results of this study illustrate a possible way in which HCHO influences nitrate renoxification in the atmosphere. Factors such as particulate matter composition, RH, and initial HCHO concentration all influence the positive effect of HCHO; notably, H2O competes with NO for photogenerated holes. Based on these findings, two balance systems should be explored in depth: the influence of RH on the generation rates of HONO and NOx, as water increases the proportion of HONO in nitrogen-containing products; and the balance between the photocatalytic degradation of generated NOx on TiO2 particles and the positive effect of HCHO on NOx generation at low HCHO concentrations.

Based on our results, we conclude that, in photochemical processes on the surfaces of particles containing semiconductor oxides, with the participation of hydrogen donor organics, a significant synergistic photocatalytic renoxification enhancement effect could alter the composition of surface nitrogenous species via the NO–NO3•–HNO3–NOx pathway, thereby affecting atmospheric oxidation and nitrogen cycling. The positive effect of HCHO can be extended from TiO2 in this study to other components of mineral dust, such as Fe2O3 and ZnO with photocatalytic activity, which may have practical applications. Our proposed reaction mechanism by which HCHO promotes photocatalytic renoxification could improve existing atmospheric chemistry models and reduce discrepancies between model simulations and field observations.

All data are available upon request from the corresponding authors: shangjing@pku.edu.cn.

Detailed information of Figs. S1–S13 (which include the spectra of the lamps, size distribution of 4 wt % KNO3–TiO2 and TiO2 particles, changes in HCHO concentrations in the environmental chamber, changes in NOx concentrations under different reaction conditions, photodegradation curve of HCHO, and ESR spectra of TiO2 and ATD particles) and Table S1 (which demonstrates ATD chemical composition). The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-11347-2022-supplement.

YL and JS prepared the paper with contributions from other co-authors. JS and XW designed the experiments and carried them out. YL, XW and WX prepared the supplement. YL, JS, MS and CY discussed the results. JS and YL revised the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 21876003, 41961134034 and 21277004), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (no. 2019QZKK0607).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 21876003, 41961134034, and 21277004) and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (grant no. 2019QZKK0607).

This paper was edited by Ryan Sullivan and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Aghazadeh, M.: Preparation of Gd2O3 Ultrafine Nanoparticles by Pulse Electrodeposition Followed by Heat-treatment Method, Journal of Ultrafine Grained and Nanostructured Materials, 49, 80–86, https://doi.org/10.7508/jufgnsm.2016.02.04, 2016.

Ahmed, A. Y., Kandiel, T. A., Ivanova, I., and Bahnemann, D.: Photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical oxidation mechanisms of methanol on TiO2 in aqueous solution, Appl. Surf. Sci., 319, 44–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.07.134, 2014.

Aldener, M., Brown, S. S., Stark, H., Williams, E. J., Lerner, B. M., Kuster, W. C., Goldan, P. D., Quinn, P. K., Bates, T. S., Fehsenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Reactivity and loss mechanisms of NO3 and N2O5 in a polluted marine environment: Results from in situ measurements during New England Air Quality Study 2002, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 111, D23S73, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007252, 2006.

Alexander, B., Sherwen, T., Holmes, C. D., Fisher, J. A., Chen, Q., Evans, M. J., and Kasibhatla, P.: Global inorganic nitrate production mechanisms: comparison of a global model with nitrate isotope observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 3859–3877, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-3859-2020, 2020.

Atkinson, R.: Kinetics and mechanisms of the gas-phase reactions of the NO3 radical with organic-comounds, J. Phys Chem. Ref. Data, 20, 459–507, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555887, 1991.

Baergen, A. M. and Donaldson, D. J.: Photochemical Renoxification of Nitric Acid on Real Urban Grime, Environ. Sci. Technol., 47, 815–820, https://doi.org/10.1021/es3037862, 2013.

Bao, F., Li, M., Zhang, Y., Chen, C., and Zhao, J.: Photochemical Aging of Beijing Urban PM2.5: HONO Production, Environ. Sci. Technol., 52, 6309–6316, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b00538, 2018.

Bao, F., Jiang, H., Zhang, Y., Li, M., Ye, C., Wang, W., Ge, M., Chen, C., and Zhao, J.: The Key Role of Sulfate in the Photochemical Renoxification on Real PM2.5, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 3121–3128, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b06764, 2020.

Bedjanian, Y. and El Zein, A.: Interaction of NO2 with TiO2 Surface Under UV Irradiation: Products Study, J. Phys. Chem. A, 116, 1758–1764, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp210078b, 2012.

Brown, S. S., Osthoff, H. D., Stark, H., Dube, W. P., Ryerson, T. B., Warneke, C., de Gouw, J. A., Wollny, A. G., Parrish, D. D., Fehsenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Aircraft observations of daytime NO3 and N2O5 and their implications for tropospheric chemistry, J. Photoch. Photobio. A, 176, 270–278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.10.004, 2005.

Burkholder, J. B., Talukdar, R. K., Ravishankara, A. R., and Solomon, S.: Temperature-dependence of the HNO3 UV absorption cross-sections, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 98, 22937–22948, https://doi.org/10.1029/93jd02178, 1993.

Chen, H., Nanayakkara, C. E., and Grassian, V. H.: Titanium Dioxide Photocatalysis in Atmospheric Chemistry, Chem. Rev., 112, 5919–5948, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr3002092, 2012.

Deng, J. J., Wang, T. J., Liu, L., and Jiang, F.: Modeling heterogeneous chemical processes on aerosol surface, Particuology, 8, 308–318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2009.12.003, 2010.

Dentener, F. J. and Crutzen, P. J.: Reaction of N2O5 on tropospheric aerosols-impact on the global distributions od NOx, O3, and OH, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 98, 7149–7163, https://doi.org/10.1029/92jd02979, 1993.

Du, J. and Zhu, L.: Quantification of the absorption cross sections of surface-adsorbed nitric acid in the 335-365 nm region by Brewster angle cavity ring-down spectroscopy, Chem. Phys. Lett., 511, 213–218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2011.06.062, 2011.

Finlayson-Pitts, B. J. and Pitts, J. J. N.: Chemistry of the Upper and Lower Atmosphere: Theory, Experiments and Applications, Academic Press, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012257060-5/50000-9, 1999.

Garcia, S. L. M., Pandit, S., Navea, J. G., and Grassian, V. H.: Nitrous Acid (HONO) Formation from the Irradiation of Aqueous Nitrate Solutions in the Presence of Marine Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter: Comparison to Other Organic Photosensitizers, Acs Earth and Space Chemistry, 5, 3056–3064, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00292, 2021.

George, C., Ammann, M., D'Anna, B., Donaldson, D. J., and Nizkorodov, S. A.: Heterogeneous Photochemistry in the Atmosphere, Chem. Rev., 115, 4218–4258, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr500648z, 2015.

Goodman, A. L., Bernard, E. T., and Grassian, V. H.: Spectroscopic study of nitric acid and water adsorption on oxide particles: Enhanced nitric acid uptake kinetics in the presence of adsorbed water, J. Phys. Chem. A, 105, 6443–6457, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp003722l, 2001.

Harris, G. W., Carter, W. P. L., Winer, A. M., Pitts, J. N., Platt, U., and Perner, D.: Observations of nitrous-acid in the los-angeles atmosphere and implications for predictions of ozone precursor relationships, Environ. Sci. Technol., 16, 414–419, https://doi.org/10.1021/es00101a009, 1982.

Hot, J., Martinez, T., Wayser, B., Ringot, E., and Bertron, A.: Photocatalytic degradation of NO NO2 gas injected into a 10 m3 experimental chamber, Environ. Sci. Poll. R., 24, 12562–12570, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7701-2, 2017.

Huang, L., Zhao, Y., Li, H., and Chen, Z.: Kinetics of Heterogeneous Reaction of Sulfur Dioxide on Authentic Mineral Dust: Effects of Relative Humidity and Hydrogen Peroxide, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 10797–10805, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b03930, 2015.

Kasibhatla, P., Sherwen, T., Evans, M. J., Carpenter, L. J., Reed, C., Alexander, B., Chen, Q., Sulprizio, M. P., Lee, J. D., Read, K. A., Bloss, W., Crilley, L. R., Keene, W. C., Pszenny, A. A. P., and Hodzic, A.: Global impact of nitrate photolysis in sea-salt aerosol on NOx, OH, and O3 in the marine boundary layer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 11185–11203, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-11185-2018, 2018.

Kim, W.-H., Song, J.-M., Ko, H.-J., Kim, J. S., Lee, J. H., and Kang, C.-H.: Comparison of Chemical Compositions of Size-segregated Atmospheric Aerosols between Asian Dust and Non-Asian Dust Periods at Background Area of Korea, B. Kor. Chem. Soc., 33, 3651–3656, https://doi.org/10.5012/bkcs.2012.33.11.3651, 2012.

Lee, J. D., Moller, S. J., Read, K. A., Lewis, A. C., Mendes, L., and Carpenter, L. J.: Year-round measurements of nitrogen oxides and ozone in the tropical North Atlantic marine boundary layer, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 114, D21302, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd011878, 2009.

Lesko, D. M. B., Coddens, E. M., Swomley, H. D., Welch, R. M., Borgatta, J., and Navea, J. G.: Photochemistry of nitrate chemisorbed on various metal oxide surfaces, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 17, 20775–20785, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cp02903a, 2015.

Li, X., Rohrer, F., Brauers, T., Hofzumahaus, A., Lu, K., Shao, M., Zhang, Y. H., and Wahner, A.: Modeling of HCHO and CHOCHO at a semi-rural site in southern China during the PRIDE-PRD2006 campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 12291–12305, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-12291-2014, 2014.

Linsebigler, A. L., Lu, G. Q., and Yates, J. T.: Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces-principles, mechanisms, and selected results, Chem. Rev., 95, 735–758, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr00035a013, 1995.

Liu, W., Wang, Y. H., Russell, A., and Edgerton, E. S.: Atmospheric aerosol over two urban-rural pairs in the southeastern United States: Chemical composition and possible sources, Atmos. Environ., 39, 4453–4470, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.03.048, 2005.

Ma, Q., Zhong, C., Ma, J., Ye, C., Zhao, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, P., Chen, T., Liu, C., Chu, B., and He, H.: Comprehensive Study about the Photolysis of Nitrates on Mineral Oxides, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 8604–8612, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c02182, 2021.

Maeda, N., Urakawa, A., Sharma, R., and Baiker, A.: Influence of Ba precursor on structural and catalytic properties of Pt-Ba alumina NOx storage-reduction catalyst, Appl. Catal. B-Environ., 103, 154–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.01.022, 2011.

Monge, M. E., D”Anna, B., and George, C.: Nitrogen dioxide removal and nitrous acid formation on titanium oxide surfaces–an air quality remediation process?, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 12, 8991–8998, https://doi.org/10.1039/b925785c, 2010.

Ndour, M., Conchon, P., D'Anna, B., Ka, O., and George, C.: Photochemistry of mineral dust surface as a potential atmospheric renoxification process, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L05816, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008gl036662, 2009.

Ninneman, M., Lu, S., Zhou, X. L., and Schwab, J.: On the Importance of Surface-Enhanced Renoxification as an Oxides of Nitrogen Source in Rural and Urban New York State, Acs Earth and Space Chemistry, 4, 1985–1992, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00185, 2020.

Ostaszewski, C. J., Stuart, N. M., Lesko, D. M. B., Kim, D., Lueckheide, M. J., and Navea, J. G.: Effects of Coadsorbed Water on the Heterogeneous Photochemistry of Nitrates Adsorbed on TiO2, J. Phys. Chem. A, 122, 6360–6371, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.8b04979, 2018.

Pandit, S., Garcia, S. L. M., and Grassian, V. H.: HONO Production from Gypsum Surfaces Following Exposure to NO2 and HNO3: Roles of Relative Humidity and Light Source, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 9761–9772, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c01359, 2021.

Park, J., Jang, M., and Yu, Z. C.: Heterogeneous Photo-oxidation of SO2 in the Presence of Two Different Mineral Dust Particles: Gobi and Arizona Dust, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 9605–9613, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00588, 2017.

Platt, U., Perner, D., Harris, G. W., Winer, A. M., and Pitts, J. N.: Observations of nitrous-acid in an urban atmosphere by differential optical-absorption, Nature, 285, 312–314, https://doi.org/10.1038/285312a0, 1980.

Read, K. A., Mahajan, A. S., Carpenter, L. J., Evans, M. J., Faria, B. V. E., Heard, D. E., Hopkins, J. R., Lee, J. D., Moller, S. J., Lewis, A. C., Mendes, L., McQuaid, J. B., Oetjen, H., Saiz-Lopez, A., Pilling, M. J., and Plane, J. M. C.: Extensive halogen-mediated ozone destruction over the tropical Atlantic Ocean, Nature, 453, 1232–1235, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07035, 2008.

Reed, C., Evans, M. J., Crilley, L. R., Bloss, W. J., Sherwen, T., Read, K. A., Lee, J. D., and Carpenter, L. J.: Evidence for renoxification in the tropical marine boundary layer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 4081–4092, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-4081-2017, 2017.

Romer, P. S., Wooldridge, P. J., Crounse, J. D., Kim, M. J., Wennberg, P. O., Dibb, J. E., Scheuer, E., Blake, D. R., Meinardi, S., Brosius, A. L., Thames, A. B., Miller, D. O., Brune, W. H., Hall, S. R., Ryerson, T. B., and Cohen, R. C.: Constraints on Aerosol Nitrate Photolysis as a Potential Source of HONO and NOx, Environ. Sci. Technol., 52, 13738–13746, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b03861, 2018.

Rosseler, O., Sleiman, M., Nahuel Montesinos, V., Shavorskiy, A., Keller, V., Keller, N., Litter, M. I., Bluhm, H., Salmeron, M., and Destaillats, H.: Chemistry of NOx on TiO2 Surfaces Studied by Ambient Pressure XPS: Products, Effect of UV Irradiation, Water, and Coadsorbed K+, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 4, 536–541, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz302119g, 2013.

Salthammer, T.: Formaldehyde sources, formaldehyde concentrations and air exchange rates in European housings, Build. Environ., 150, 219–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.12.042, 2019.

Schuttlefield, J., Rubasinghege, G., El-Maazawi, M., Bone, J., and Grassian, V. H.: Photochemistry of adsorbed nitrate, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 130, 12210–12211, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja802342m, 2008.

Schutze, M. and Herrmann, H.: Uptake of the NO3 radical on aqueous surfaces, J. Atmos. Chem., 52, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10874-005-6153-8, 2005.

Schwartz-Narbonne, H., Jones, S. H., and Donaldson, D. J.: Indoor Lighting Releases Gas Phase Nitrogen Oxides from Indoor Painted Surfaces, Environ. Sci. Tech. Let., 6, 92–97, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00685, 2019.

Seltzer, K. M., Vizuete, W., and Henderson, B. H.: Evaluation of updated nitric acid chemistry on ozone precursors and radiative effects, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5973–5986, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5973-2015, 2015.

Shang, J., Xu, W. W., Ye, C. X., George, C., and Zhu, T.: Synergistic effect of nitrate-doped TiO2 aerosols on the fast photochemical oxidation of formaldehyde, Sci. Rep.-UK, 7, 1161, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01396-x, 2017.

Shi, Q., Tao, Y., Krechmer, J. E., Heald, C. L., Murphy, J. G., Kroll, J. H., and Ye, Q.: Laboratory Investigation of Renoxification from the Photolysis of Inorganic Particulate Nitrate, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 854–861, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c06049, 2021.

Stemmler, K., Ammann, M., Donders, C., Kleffmann, J., and George, C.: Photosensitized reduction of nitrogen dioxide on humic acid as a source of nitrous acid, Nature, 440, 195–198, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04603, 2006.

Sun, Y. L., Zhuang, G. S., Wang, Y., Zhao, X. J., Li, J., Wang, Z. F., and An, Z. S.: Chemical composition of dust storms in Beijing and implications for the mixing of mineral aerosol with pollution aerosol on the pathway, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 110, D24209, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006054, 2005.

Tang, M., Liu, Y., He, J., Wang, Z., Wu, Z., and Ji, D.: In situ continuous hourly observations of wintertime nitrate, sulfate and ammonium in a megacity in the North China plain from 2014 to 2019: Temporal variation, chemical formation and regional transport, Chemosphere, 262, 127745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127745, 2021.

Tian, S. S., Liu, Y. Y., Wang, J., Wang, J., Hou, L. J., Lv, B., Wang, X. H., Zhao, X. Y., Yang, W., Geng, C. M., Han, B., and Bai, Z. P.: Chemical Compositions and Source Analysis of PM2.5 during Autumn and Winter in a Heavily Polluted City in China, Atmosphere, 11, 336, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11040336, 2020.

Verbruggen, S. W.: TiO2 photocatalysis for the degradation of pollutants in gas phase: From morphological design to plasmonic enhancement, J. Photoch. Photobio. C, 24, 64–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2015.07.001, 2015.

Wang, H., Miao, Q., Shen, L., Yang, Q., Wu, Y., Wei, H., Yin, Y., Zhao, T., Zhu, B., and Lu, W.: Characterization of the aerosol chemical composition during the COVID-19 lockdown period in Suzhou in the Yangtze River Delta, China, J. Environ. Sci.-China, 102, 110–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2020.09.019, 2021.

Wayne, R. P., Barnes, I., Biggs, P., Burrows, J. P., Canosamas, C. E., Hjorth, J., Lebras, G., Moortgat, G. K., Perner, D., Poulet, G., Restelli, G., and Sidebottom, H.: The nitrate radical-physics, chemistry, and the atmosphere, Atmos. Environ. A-Gen., 25, 1–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-1686(91)90192-a, 1991.

Wilbourn, J., Heseltine, E., and Moller, H.: IARC Evaluates Wood dust and formaldehyde, Scand. J. Work Env. Hea., 21, 229–232, https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1368, 1995.

Yang, F., Tan, J., Zhao, Q., Du, Z., He, K., Ma, Y., Duan, F., Chen, G., and Zhao, Q.: Characteristics of PM2.5 speciation in representative megacities and across China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 5207–5219, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-5207-2011, 2011.

Ye, C., Gao, H., Zhang, N., and Zhou, X.: Photolysis of Nitric Acid and Nitrate on Natural and Artificial Surfaces, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 3530–3536, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05032, 2016a.

Ye, C., Zhou, X., Pu, D., Stutz, J., Festa, J., Spolaor, M., Tsai, C., Cantrell, C., Mauldin, R. L., III, Campos, T., Weinheimer, A., Hornbrook, R. S., Apel, E. C., Guenther, A., Kaser, L., Yuan, B., Karl, T., Haggerty, J., Hall, S., Ullmann, K., Smith, J. N., Ortega, J., and Knote, C.: Rapid cycling of reactive nitrogen in the marine boundary layer, Nature, 532, 489–491, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17195, 2016b.

Ye, C., Zhang, N., Gao, H., and Zhou, X.: Photolysis of Particulate Nitrate as a Source of HONO and NOx, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 6849–6856, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00387, 2017.

Zhou, J. B., Xing, Z. Y., Deng, J. J., and Du, K.: Characterizing and sourcing ambient PM2.5 over key emission regions in China I: Water-soluble ions and carbonaceous fractions, Atmos. Environ., 135, 20–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.03.054, 2016.

Zhou, X. L., Gao, H. L., He, Y., Huang, G., Bertman, S. B., Civerolo, K., and Schwab, J.: Nitric acid photolysis on surfaces in low-NOx environments: Significant atmospheric implications, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 2217, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003gl018620, 2003.