the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Himawari-8-derived diurnal variations in ground-level PM2.5 pollution across China using the fast space-time Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)

Rachel T. Pinker

Lin Sun

Wenhao Xue

Maureen Cribb

Fine particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 µm (PM2.5) has been used as an important atmospheric environmental parameter mainly because of its impact on human health. PM2.5 is affected by both natural and anthropogenic factors that usually have strong diurnal variations. Such information helps toward understanding the causes of air pollution, as well as our adaptation to it. Most existing PM2.5 products have been derived from polar-orbiting satellites. This study exploits the use of the next-generation geostationary meteorological satellite Himawari-8/AHI (Advanced Himawari Imager) to document the diurnal variation in PM2.5. Given the huge volume of satellite data, based on the idea of gradient boosting, a highly efficient tree-based Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) method by involving the spatiotemporal characteristics of air pollution, namely the space-time LightGBM (STLG) model, is developed. An hourly PM2.5 dataset for China (i.e., ChinaHighPM2.5) at a 5 km spatial resolution is derived based on Himawari-8/AHI aerosol products with additional environmental variables. Hourly PM2.5 estimates (number of data samples = 1 415 188) are well correlated with ground measurements in China (cross-validation coefficient of determination, CV-R2 = 0.85), with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) of 13.62 and 8.49 µg m−3, respectively. Our model captures well the PM2.5 diurnal variations showing that pollution increases gradually in the morning, reaching a peak at about 10:00 LT (GMT+8), then decreases steadily until sunset. The proposed approach outperforms most traditional statistical regression and tree-based machine-learning models with a much lower computational burden in terms of speed and memory, making it most suitable for routine pollution monitoring.

- Article

(12917 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

China has faced severe environmental problems during the last 2 decades, especially air pollution (An et al., 2019; Chan and Yao, 2008; Z. Li et al., 2017; Q. Zhang et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2021a). The sources of air pollution are numerous, coming from both natural changes (e.g., forest fires, biomass burning) and human activities (e.g., industrial production, transportation) (Huang et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2004; Wei et al., 2019a, b, 2021b). Particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 µm (PM2.5) has a greater impact on the atmospheric environment and climate change than other air pollutants (e.g., PM10, nitrogen dioxide, NO2, and sulfur dioxide, SO2) (Jacob and Winner, 2009; Z. Li et al., 2017, 2019; Ramanathan and Feng, 2009). Moreover, they can cause great harm to human health due to their smaller particle size (Delfino et al., 2005; Kampa and Castanas, 2008; Kim et al., 2015; Lelieveld et al., 2015). China has established and operates multiple ground-based observation networks to monitor air pollution in real time across mainland China, including information about PM2.5 pollution.

For near-surface concentrations, the networks provide high-quality PM2.5 measurements every hour (even every few minutes) but with non-uniform coverage. In recent years, an increased effort has been made in estimating PM2.5 with products generated from multiple instruments on sun-synchronous satellites, e.g., the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) (Liu et al., 2005; van Donkelaar et al., 2006), the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) (Liu et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2019a, 2020, 2021a), and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) (Wei et al., 2021c; Wu et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2019). However, due to their low revisit cycles (one or two overpasses per day), they are unable to monitor the diurnal variation in pollution. Currently, most available PM2.5 datasets are at low temporal resolutions that cannot meet the requirements of air pollution real-time monitoring (Lennartson et al., 2018). For example, knowing when heavy pollution might occur during the day, people may adjust their time outdoors doing activities accordingly. Following the launch of the Himawari-8 Advanced Himawari Imager (Himawari-8/AHI) on 7 October 2014 (Bessho et al., 2016; Letu et al., 2020), near-surface PM2.5 concentrations in the Eastern Hemisphere can now be estimated and used to examine their diurnal cycle.

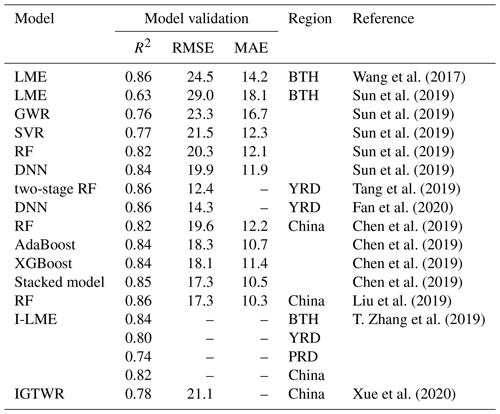

Wang et al. (2017) used the linear mixed-effect (LME) model, and Sun et al. (2019) applied the geographically weighted regression (GWR) and support vector regression (SVR) models to estimate hourly PM2.5 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region from the Himawari-8 aerosol optical depth (AOD) product. T. Zhang et al. (2019) developed an improved LME model, and Xue et al. (2020) proposed an improved geographically and temporally weighted regression (IGTWR) model to derive hourly PM2.5 maps based on the Himawari-8 AOD product over central and eastern China. In addition to traditional statistical regression models, several artificial intelligence models, including the random forest (RF), the gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT), the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and the deep neural network (DNN), have been recently successfully adopted to obtain ground-level PM2.5 concentrations in local regions and in the whole of China (Chen et al., 2019; Gui et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). Nevertheless, due to their poor data-mining ability, traditional statistical regression methods usually suffer from large uncertainties. While artificial intelligence methods can achieve high accuracies, they are often highly demanding on computational power and are thus often slow. Therefore, spatiotemporal variations in PM2.5 have often been neglected in the models developed in previous studies (Chen et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017; T. Zhang et al., 2019), resulting in relatively low accuracies.

Focusing on the above issues, we have developed a new, highly efficient, and precise method for improving ground-level PM2.5 estimates by incorporating spatial and temporal information into the tree-based Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) model. This new model is called the space-time LightGBM (STLG) model, and it has been used to generate a high-quality, high-temporal-resolution (hourly) PM2.5 dataset over eastern China (at a spatial resolution of 5 km) from the Himawari-8/AHI hourly AOD product. Section 2 provides details about the data used and introduces the development of the STLG model. Section 3 validates the hourly PM2.5 estimates and shows the diurnal PM2.5 variations across China. Comparisons with results from traditional models and from previous studies are also presented. Section 4 summarizes the study.

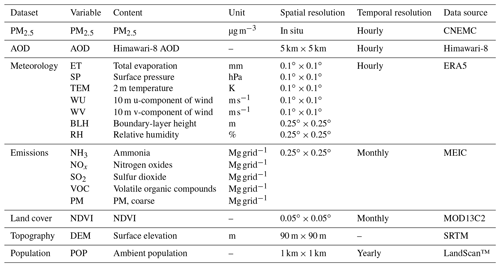

2.1 Data sources

2.1.1 PM2.5 and AOD data

PM2.5 hourly measurements from 1583 monitoring stations across China for the year 2018 were collected (Fig. 1 in Wei et al., 2020). The latest Himawari-8 version 2 hourly 5 km AODs at 500 nm across mainland China for that year were also collected. This AOD product is synthesized from level 2 10 min AODs generated by a newly developed Lambertian-surface-assumed aerosol retrieval algorithm (Letu et al., 2020; Yoshida et al., 2018). Himawari-8 AOD retrievals have been preliminarily evaluated against in situ AOD retrievals provided by the Aerosol Robotic Network (Giles et al., 2019) and the Sun–Sky Radiometer Observation Network (Li et al., 2018), showing that they are consistent (R = 0.75), with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.39 and 0.21, respectively (Wei et al., 2019c). Here, only low-uncertainty AOD retrievals (500 nm) were selected for estimating PM2.5 concentrations.

2.1.2 Meteorological conditions

PM2.5 can be significantly affected by meteorological conditions (Su et al., 2018). However, most currently available reanalysis meteorological products have low temporal resolutions (∼ 3–6 h). Recently (14 June 2018), the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) global atmospheric reanalysis (ERA5) at a horizontal resolution of 0.25∘ × 0.25∘ has been released, as well as the land version (12 July 2019) at a horizontal resolution of 0.1∘ × 0.1∘, both at an hourly timescale (1979 to the present). Here, we use seven ERA5 hourly meteorological parameters, i.e., the 2 m temperature (TEM), total evaporation (ET), relative humidity (RH), 10 m u- and v-components of wind, surface pressure (SP), and boundary-layer height (BLH).

2.1.3 Human influences

Human activity is a key factor affecting PM2.5 pollution. The global annual LandScan™ product at a 1 km spatial resolution for the year 2018 was selected to obtain the population distribution (POP) (Dobson et al., 2000). Monthly anthropogenic source emission data from the Multi-resolution Emission Inventory for China (MEIC) (M. Li et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2018) were also employed. This dataset is generated from agricultural, industrial, power, residential, and transportation information obtained at more than 700 anthropogenic sources, including a total of 10 atmospheric pollutants and greenhouse gases. Here, four main precursors were selected, i.e., ammonia (NH3), nitrogen oxides (NOx), SO2, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and direct emissions to PM.

2.1.4 Ancillary data

Two additional ancillary datasets, namely, the MODIS monthly normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) at a horizontal resolution of 0.05∘ × 0.05∘ and the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 90 m digital elevation model (DEM) products, were selected to characterize land cover, its change, and topographical conditions in China. All selected variables (Table 1) with potential impacts on PM2.5 concentrations were resampled to the same spatial resolution as the Himawari-8 aerosol product, namely, 0.05∘ × 0.05∘.

2.2 Space-time LightGBM model

2.2.1 LightGBM model

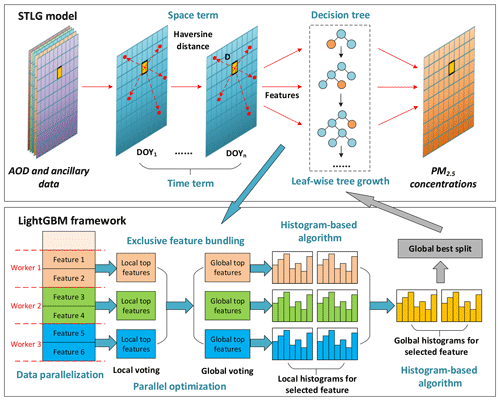

The LightGBM model, a newly developed tree-based machine-learning approach, was introduced in 2017 (Ke et al., 2017). Using the gradient boosting framework to construct the decision tree, this approach can tackle both regression and classification tasks and as such can be expanded for PM applications. It can also tackle the main challenge faced in traditional machine-learning approaches, namely, computational complexities, which are very time-consuming. LightGBM is a fast, distributed, and highly efficient method that reduces the number of data samples (M) and features (N). The LightGBM model includes three main steps when constructing the decision tree.

-

Histogram-based algorithm. Continuous features are first converted to different bins which are used to construct feature index histograms without the need to sort during training. It goes through all the data bins to find the best split point from the feature histograms, which can significantly reduce the computation cost of the split gain. The overall complexity is O (M × N).

-

Gradient-based one-side sampling. Data samples are first sorted in descending order according to their absolute gradients, and the top a % of them are selected as a subset sample with large gradients. The b % samples are then randomly chosen from the remaining data as a subset sample with small gradients. The sampled data with small gradients are multiplied by a weight coefficient . Consequently, a new classifier is learned and established using the above-sampled data until convergence.

-

Exclusive feature bundling. A graph with weighted edges is first constructed, and each weight corresponds to the total number of conflicts between two features. The features are then sorted in descending order according to the degree of each feature (the greater the degree, the greater the conflict with other points). Last, each feature is checked in the sorted sequence, and it is assigned to a combination with small conflicts or a new combination is created.

In addition to the main technologies mentioned above, there are other features of the optimization, such as the leaf-wise tree growth strategy with depth restriction (Shi, 2007), histogram difference acceleration, sequential access gradient, and the support of category feature and parallel learning. These advanced methodologies make it possible to reach a high accuracy and efficiency (Ke et al., 2017).

2.2.2 Model development

It is well known that air pollution has spatiotemporal heterogeneity leading to large differences in PM2.5 concentrations in both time and space. Such characteristics have always been ignored in most traditional statistical regression and artificial intelligence methods. Studies have shown that including spatiotemporal information has led to improved PM2.5 estimates using remote sensing techniques (Z. Li et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2019a, 2020). Therefore, we have introduced a new approach to integrating spatiotemporal information into the LightGBM model. The new model developed here is called the STLG model. The spatial feature is represented by the geographical distances of one pixel to other points in the circumscribed rectangle of the study region (Baez-Villanueva et al., 2020; Behrens et al., 2018). The distance is calculated using the haversine method (Eq. 1) to reflect the spherical distance between two points in the sphere space (Wei et al., 2021a). The temporal feature is represented by the day of the year (DOY), which is used to distinguish each data record on different days of the year during the model training.

where φ and γ represent the latitude and longitude of a point on the sphere, respectively, and r denotes Earth's mean radius (≈ 6371 km). Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the new STLG model.

Figure 1Schematics of the space-time LightGBM (STLG) model developed in this study (upper panel) and the framework of the original LightGBM model (bottom panel).

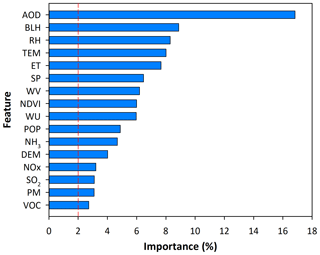

In addition to Himawari-8 AODs, other auxiliary variables were considered and employed to improve PM2.5–AOD relationships. However, to avoid redundant information, we first calculated the normalized importance (%) of each feature to the PM2.5 estimation during the model training (Fig. 2). It represents the total gains of splits that use the feature during the decision-tree construction but not the physical contribution. AOD is found to be the most important feature, accounting for about 17 %. All meteorological factors have an important impact on the PM2.5 estimation, especially BLH, RH, and TEM (importance > 8 %), followed by two surface-related variables (i.e., NDVI and DEM) and POP. The influence of aerosol precursors and emissions (i.e., NH3, NOx, SO2, PM, and VOC) on the PM2.5 estimation cannot be ignored (importance > 2 %). Therefore, all 16 selected variables are included to establish the final model in this study.

Figure 2Sorted normalized importance (%) of each feature in the PM2.5 estimation during the model construction.

Here, two independent 10-fold cross-validation methods (10-CV) (Rodriguez et al., 2010) based on all the data samples (i.e., out-of-sample) and PM2.5 monitoring stations (i.e., out-of-station) were selected to validate the model performance and the spatial prediction ability, respectively.

3.1 Model fitting and validation

3.1.1 Spatial-scale performance

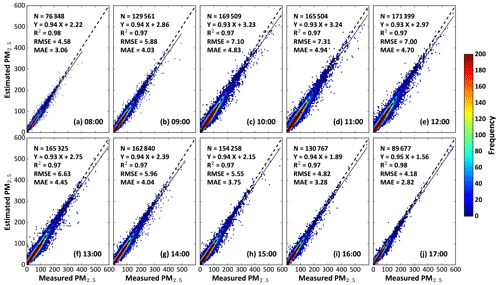

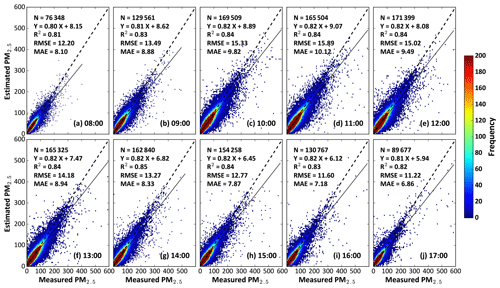

The STLG model can largely minimize overfitting, showing a strong data-mining ability (Fig. 3) which can more accurately establish the relationships between hourly PM2.5 observations and influential variables (i.e., coefficient of determination, R2 = 0.97–0.98, RMSE = 4.18–7.31 µg m−3). Figure 4 illustrates the out-of-sample evaluation results of estimated hourly PM2.5 values over China from 08:00 to 17:00 LT in 2018. The STLG model is highly accurate in estimating hourly PM2.5 concentrations, with high sample-based CV-R2 values ranging from 0.81 to 0.85, strong slopes of ∼ 0.81–0.84, and small y-intercepts of ∼ 5.52–7.84 µg m−3. The uncertainties are overall small, with RMSEs (MAEs) ranging from 11.24 (6.82) µg m−3 to 15.56 (9.79) µg m−3. However, the STLG performs slightly differently with small differences in main evaluation indicators throughout the day. The main reason being that the number of training samples is reduced during sunrise (Fig. 4a and b) and sunset (Fig. 4i and j) in optical remote sensing, affecting the model training. Air pollution also has clear diurnal variations at different PM2.5 pollution levels due to the different intensities of human activities and natural conditions. In general, our model is stable and robust, with an equal out-of-sample CV-R2 of 0.85 and an equal regression slope of 0.81 at most hours during the day in China (Fig. 4c–h).

Figure 3Density scatterplots of model-fitted PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) at (a) 08:00 LT, (b) 09:00 LT, (c) 10:00 LT, (d) 11:00 LT, (e) 12:00 LT, (f) 13:00 LT, (g) 14:00 LT, (h) 15:00 LT, (i) 16:00 LT, and (j) 17:00 LT in 2018 in China. Dashed lines denote 1:1 lines, and solid lines denote best-fit lines from linear regression.

Figure 4Density scatterplots of out-of-sample cross-validation results of PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) at (a) 08:00 LT, (b) 09:00 LT, (c) 10:00 LT, (d) 11:00 LT, (e) 12:00 LT, (f) 13:00 LT, (g) 14:00 LT, (h) 15:00 LT, (i) 16:00 LT, and (j) 17:00 LT in 2018 in China. Dashed lines denote 1:1 lines, and solid lines denote best-fit lines from linear regression.

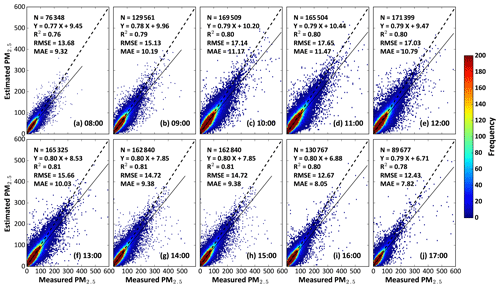

Figure 5Density scatterplots of out-of-station cross-validation results of PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) at (a) 08:00 LT, (b) 09:00 LT, (c) 10:00 LT, (d) 11:00 LT, (e) 12:00 LT, (f) 13:00 LT, (g) 14:00 LT, (h) 15:00 LT, (i) 16:00 LT, and (j) 17:00 LT in 2018 in China. Dashed and solid lines denote 1:1 and best-fit lines from linear regression, respectively.

Furthermore, out-of-station CV-R2 values range from 0.76 to 0.81, and RMSE (MAE) values range from 12.49 (7.85) µg m−3 to 17.61 (11.33) µg m−3 (Fig. 5), indicating that our model has a strong spatial prediction ability and can predict PM2.5 values well in those areas without surface observations.. The station-based accuracy is also slightly decreased with reference to the sample-based accuracy, further illustrating the robustness of our model. However, two cross-validation results (e.g., slopes = 0.78–0.84) indicate that hourly PM2.5 concentrations are overall underestimated (Figs. 4–5), a common issue in fine-particle remote sensing (Wei et al., 2020). This can be explained by the large aerosol retrieval uncertainty, as well as the small number of data samples under highly polluted conditions (Wei et al., 2019c, d).

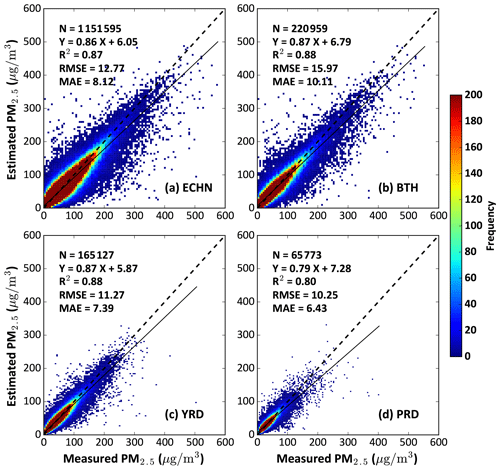

The regional performance of the STLG model for hourly PM2.5 estimates (Fig. 6) was also evaluated. Hourly PM2.5 estimates (number of data samples, N = 1 151 595) are highly consistent with ground measurements, with a high sample-based CV-R2 of 0.87 and a strong regression slope of 0.86, showing small estimation uncertainties (i.e., RMSE = 12.77 µg m−3, MAE = 8.12 µg m−3) over eastern China. The STLG model performs well (e.g., CV-R2 = 0.88, slope = 0.87) in two typical urban agglomerations of public concern in China, i.e., the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) (Fig. 6b) and Yangtze River Delta (YRD) (Fig. 6c) regions. By contrast, our model performs relatively poorly in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region (Fig. 6d) possibly due to the significant reduction in the number of data samples caused by frequent, long-term cloud cover in southern China. Note that there are some differences in the uncertainty of hourly PM2.5 estimates mainly because of varying levels of air pollution. The pollution level in the BTH region is about 3 times higher than that in the PRD region.

Figure 6Density scatterplots of out-of-sample cross-validation results of hourly PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) in 2018 for (a) eastern China, (b) the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region, (c) the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), and (d) the Pearl River Delta (PRD) in China.

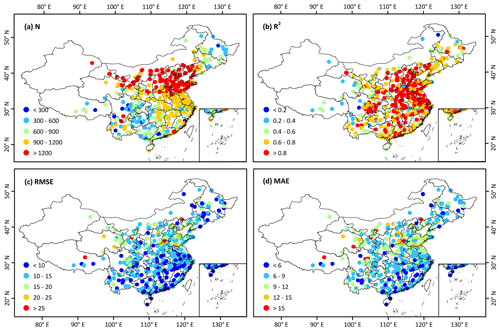

Figure 7Individual-site-scale validation of hourly PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) in 2018 in China in terms of (a) the sample size (N), (b) CV-R2, (c) RMSE, and (d) MAE.

Figure 7 shows the accuracy of the STLG model at each monitoring station across China. At the individual site scale, the number of data samples gradually decreases from northern China to southern China mainly due to increasing cloud contamination with a site average of 997 data samples in China. Except for several scattered monitoring stations in western China, the STLG model has a high performance and adaptability and can estimate well hourly PM2.5 concentrations at most monitoring stations (e.g., average CV-R2 = 0.78, RMSE = 12.21 µg m−3, and MAE = 8.17 µg m−3). In general, approximately 76 %, 79 %, and 82 % of monitoring stations show high accuracy, with out-of-sample CV-R2 values > 0.7, RMSE values < 15 µg m−3, and MAE values < 10 µg m−3 in hourly PM2.5 estimates, especially for those located in central and northern China.

3.1.2 Temporal-scale performance

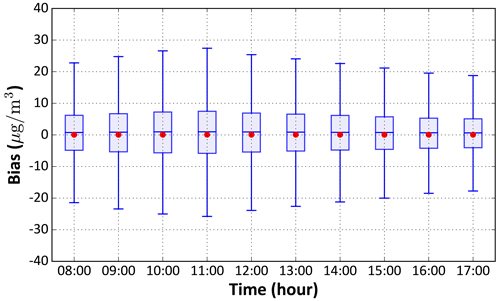

We first quantified the time series of the bias in hourly PM2.5 estimates during the day in China (Fig. 8). There is a slight temporal dependence in that the PM2.5 bias increases gradually with increasing standard deviation, reaching a maximum around 11:00 LT and subsequently decreasing. This seems to be closely related to the diurnal variation in PM2.5 concentrations. The PM2.5 estimates are less affected by the time-dependent bias in the Himawari-8 AOD product (Wei et al., 2019c) because machine learning is not sensitive to the systematic bias of aerosol retrievals (Wei et al., 2021c). Nevertheless, our model is generally robust and can accurately estimate PM2.5 concentrations with small mean (median) biases of 0.05–0.08 (0.63–0.99) µg m−3 during different hours throughout the day.

Figure 8Boxplots of the temporal dependence of the bias in hourly PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) in 2018 in China. In each box, the red dot represents the mean bias, and the middle, lower, and upper horizontal blue lines represent the median bias, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile, respectively.

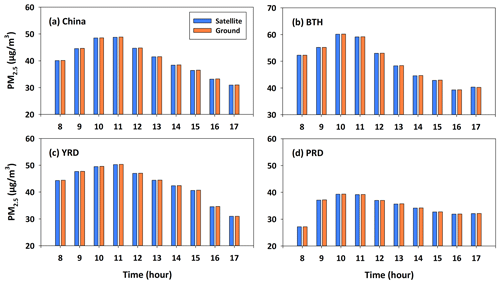

Figure 9Time series of Himawari-8-derived (blue bars) and ground-based (orange bars) PM2.5 diurnal variations (µg m−3) in (a) China, (b) the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region, (c) the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), and (d) the Pearl River Delta (PRD).

We also compared Himawari-8-derived and ground-based PM2.5 diurnal variations from all available monitoring stations in China and three typical urban clusters (Fig. 9). Hourly PM2.5 concentrations observed by satellite are highly consistent with ground-based measurements, with a small difference within ± 0.10, 0.11, 0.13, and 0.11 µg m−3 in China and in each region. Moreover, the same diurnal variations in PM2.5 pollution are seen during the day; i.e., they reach their maximum values at 10:00 or 11:00 LT and are lower at sunrise and sunset. These results illustrate that the diurnal PM2.5 variations derived from Himawari-8 are reasonable compared to ground-based measurements.

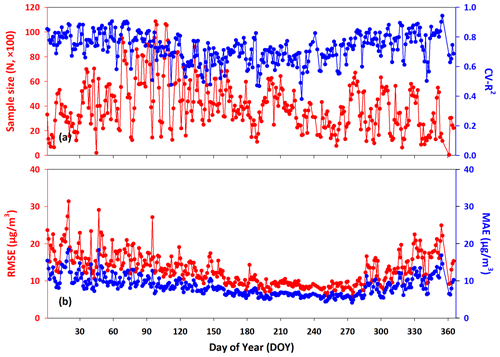

Figure 10Time series of out-of-sample cross validation of hourly PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) in terms of (a) the sample size (N, red) and CV-R2 (blue) and (b) RMSE (red) and MAE (blue) in 2018 in China.

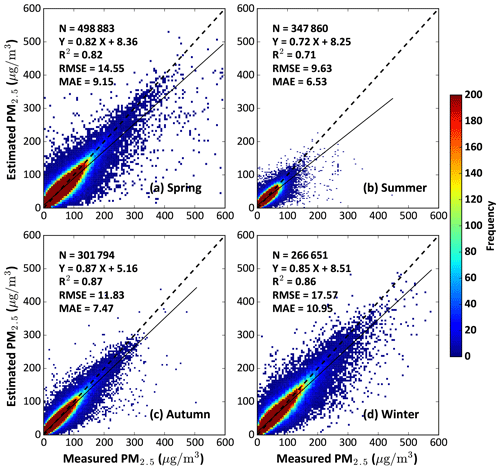

We investigated the time series of the daily performance of the STLG model in estimating hourly PM2.5 concentrations in China. The number of data samples varies on a daily basis, with an average of 3975 d−1 and with more than 83 % of all days having more than 2000 (Fig. 10). The large gap in the number of data samples is mainly caused by different degrees of cloud contamination in the satellite aerosol products for different days. The STLG model captures well the hourly PM2.5 values on most days, with an average out-of-sample R2 of 0.73 and average RMSE and MAE values of 13.06 and 8.53 µg m−3, respectively. In general, hourly PM2.5 estimates are more reliable on approximately 79 % (CV-R2 > 0.7), 70 % (RMSE < 15 µg m−3), and 74 % (MAE < 10 µg m−3) of the days in the year. The model performance also varies greatly at the seasonal level, with average CV-R2 values of 0.82, 0.71, 0.87, and 0.86 and average RMSE values of 14.55, 9.63, 11.83, and 17.57 µg m−3 in spring, summer, autumn, and winter, respectively (Fig. 11). In general, the overall uncertainty of PM2.5 estimates increases at the beginning and at the end of the year likely due to the harsher environmental conditions (e.g., low humidity and less precipitation) and more intense human activities (e.g., coal heating and straw burning) in winter and spring.

Figure 11Density scatterplots of out-of-sample cross-validation results of hourly PM2.5 estimates (µg m−3) for (a) spring, (b) summer, (c) autumn, and (d) winter of 2018 in China. Dashed and solid lines denote 1:1 and best-fit lines from linear regression, respectively.

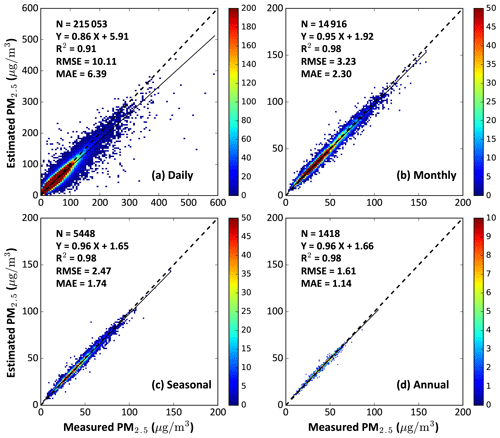

We have evaluated temporally synthesized PM2.5 data from the hourly data samples at each monitoring station for the year 2018 (Fig. 12). Daily mean PM2.5 estimates are highly correlated to those calculated from surface observations (R2 = 0.91), and the average RMSE (MAE) value is 10.11 (6.39) µg m−3. This suggests that the STLG model can capture daily PM2.5 variations more accurately. Note that daily synthetic PM2.5 data derived from geostationary satellites have a higher temporal frequency than data derived from sun-synchronous satellites. In general, PM2.5 synthetic values also have high accuracies and low estimation uncertainties (e.g., R2 = 0.98, RMSE = 1.6–3.3 µg m−3, MAE = 1.1–2.3 µg m−3) from monthly to annual scales, allowing for a better description of spatiotemporal distributions and variations in PM2.5 pollution across China.

3.2 Spatiotemporal characteristics

3.2.1 Diurnal variations

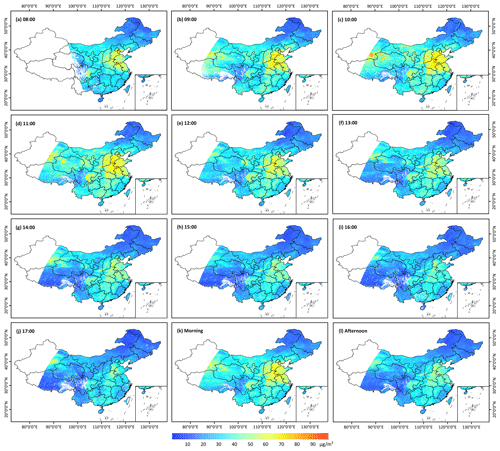

Figure 13 shows Himawari-8-derived hourly mean near-surface PM2.5 concentrations from 08:00 to 17:00 LT in 2018 across mainland China. They do not cover western Xinjiang and Tibet due to the limitation of satellite scanning. PM2.5 pollution varies diurnally across China, being at an overall low level at sunrise (∼ 29.94 ± 10.91 µg m−3). With the increase in human activities, air pollution becomes more severe over time, reaching a peak at around 10:00–11:00 LT in China (∼ 36 ± 13 µg m−3). These high levels of pollution can last several hours. As the day progresses, human activities subside, and atmospheric fine particles settle on surfaces. PM2.5 concentrations thus decrease towards sunset in most areas in China (∼ 23.21 ± 9.73 µg m−3). In general, air pollution in the morning (i.e., 08:00–12:00 LT) is much more severe than in the afternoon (i.e., 13:00–17:00 LT) in China, with morning PM2.5 concentrations about 1.3 times higher than afternoon levels. This is related to the influence of varying BLHs (Z. Li et al., 2017; Su et al., 2018).

Figure 13Himawari-8-derived hourly mean PM2.5 maps (5 km) for different times of the day: (a) 08:00 LT, (b) 09:00 LT, (c) 10:00 LT, (d) 11:00 LT, (e) 12:00 LT, (f) 13:00 LT, (g) 14:00 LT, (h) 15:00 LT, (i) 16:00 LT, (j) 17:00 LT, (k) morning (08:00–12:00 LT), and (l) afternoon (13:00–17:00 LT) in 2018 across China.

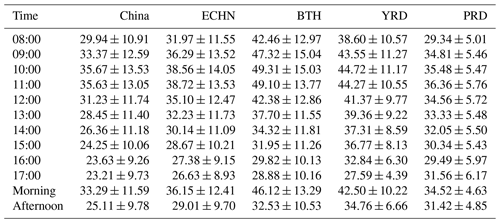

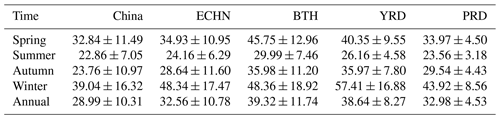

Table 2Hourly mean PM2.5 concentrations (µg m−3) in 2018 in China, eastern China (ECHN), the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region, the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), and the Pearl River Delta (PRD).

Table 2 summarizes the diurnal PM2.5 variations in eastern China and three typical urban agglomerations. PM2.5 pollution levels in eastern China are generally higher than the national level at each hour of the day due to the dense human population and intensive human activities. In the BTH region, PM2.5 pollution varies greatly, with hourly PM2.5 concentrations ranging from 28.88 ± 10.16 µg m−3 (10:00 LT) to 49.31 ± 15.03 µg m−3 (16:00 LT) and with differences exceeding 20 µg m−3. PM2.5 pollution remained at a high level (> 42 µg m−3) before 12:00 LT and dropped to a lower level (< 29 µg m−3) after 16:00 LT. This is closely related to people's daily activities and the production and life cycle of PM2.5 during the day, as well as the change in boundary mixing as a function of the day (Lennartson et al., 2018; Wang and Christopher, 2003). Similar patterns and PM2.5 pollution levels are seen in the YRD region. In general, the PRD region is less polluted in the morning but more severely polluted in the afternoon than the BTH region. Compared with the BTH and PRD regions, PM2.5 pollution in the PRD region is much lower and shows a smaller diurnal difference, with hourly PM2.5 values ranging from 29.49 ± 5.97 µg m−3 (11:00 LT) to 36.36 ± 5.76 µg m−3 (08:00 LT). Better natural conditions and fewer pollutant emissions mainly explain this (Su et al., 2018).

In general, our satellite-derived diurnal variations in PM2.5 pollution agree well with ground-based observations at both national and regional levels but with generally lower PM2.5 concentrations (Fig. 9). The reason is that the PM2.5 monitoring stations are unevenly distributed and vary greatly in the number of stations at the regional scale. Also, most sites are distributed in urban areas, leading to inevitable overestimations due to urban–rural differences. However, satellite remote sensing can cope with this deficiency by generating spatially continuous PM2.5 maps, providing more accurate information about the distribution of and variations in PM2.5 pollution.

3.2.2 Seasonal and annual variations

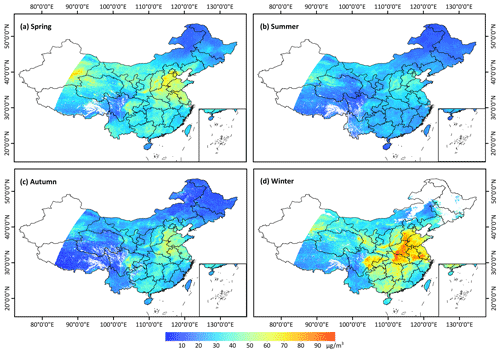

Seasonal PM2.5 maps are synthesized from daily PM2.5 maps from 2018 across China according to our previous approach (Wei et al., 2019a). Our results illustrate that PM2.5 pollution varies greatly on a seasonal scale (Fig. 14). Pollution levels are generally low and show similar spatial patterns in summer (∼ 22.86 ± 7.05 µg m−3) and autumn (∼ 23.76 ± 10.97 µg m−3) across China (Table 3). By contrast, it is much more severe in spring (∼ 32.84 ± 11.49 µg m−3) and winter (∼ 39.04 ± 16.32 µg m−3) across China, especially in the BTH and YRD regions in winter. The main reasons are the frequent sandstorms and the long-distance transmission of sand and dust in spring and the burning of coal and fossil fuels for heating in winter leading to more pollutant emissions in northern China.

Figure 14Himawari-8-derived seasonal mean PM2.5 maps (5 km) for (a) spring, (b) summer, (c) autumn, and (d) winter of 2018 across China.

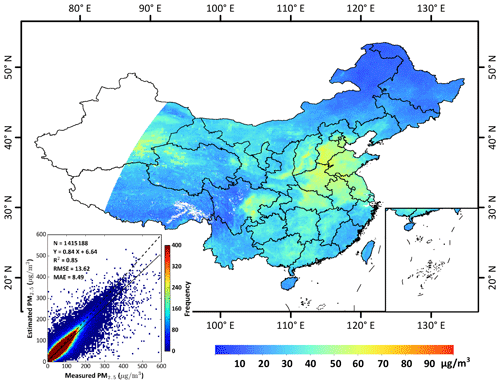

Figure 15Himawari-8-derived annual mean PM2.5 map (5 km) for the year 2018 across China. The lower-left-inserted density scatterplot represents out-of-sample cross-validation results for all hourly PM2.5 estimates in China.

Table 3Annual and seasonal mean PM2.5 concentrations (µg m−3) in 2018 in China, eastern China (ECHN), the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region, the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), and the Pearl River Delta (PRD).

PM2.5 pollution also shows significant spatial heterogeneities across China (Fig. 15), with an annual mean PM2.5 concentration of 28.99 ± 10.31 µg m−3 in 2018 (Table 3). High pollution levels are always observed in the Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Anhui, Henan, Hubei, and Sichuan provinces. Interactions between intensive human activities, adverse stagnant weather (e.g., low BLHs and low winds), and special terrain (e.g., basin) can increase anthropogenic aerosols (Chen et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2018). By contrast, PM2.5 pollution is relatively light in the northeast (e.g., Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces), the southwest (e.g., Tibet and Yunnan provinces), and the eastern coastal areas of China (e.g., Zhejiang and Fujian provinces). These provinces are sparsely populated or experience meteorological conditions favorable for dispersing pollution (Su et al., 2018).

3.3 Discussion

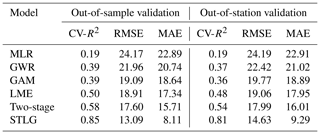

3.3.1 Comparison with traditional models

We first compared results from the STLG model with results from five widely used statistical regression models employed for estimating PM2.5 in China using the same input dataset (Table 4). The multivariate linear regression (MLR) model performs the worst due to the complex nonlinear PM2.5–AOD relationship. The GWR model performs better because it takes into account the spatial characteristics of PM2.5 pollution. The generalized additive model (GAM) and the LME model show overall improved performances with decreasing estimation uncertainties because of their nonlinear characteristics and stronger data regression abilities. The two-stage model outperforms the GAM and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) models with higher CV-R2 values and smaller estimation uncertainties by combining the advantages of the GWR and LME models. Our model performs better than all of the traditional statistical regression models considered mainly due to its stronger data-mining ability.

Table 4Comparison of the model performances of widely used models and the STLG model in estimating PM2.5 from Himawari-8 data at 14:00 LT in 2018 in China (N = 162 840).

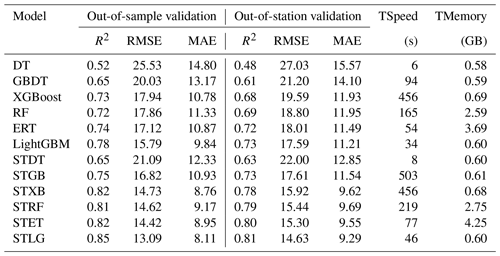

Table 5Comparison of the model performances of different tree-based machine-learning models and the STLG model using the same input data. Data are from 14:00 LT in 2018 in China (N = 162 840). TSpeed and TMemory refer to the speed and memory consumption during the model training.

The first six rows of Table 5 show the accuracies and efficiencies of six tree-based machine-learning models when estimating PM2.5 in China using the same input dataset. The decision tree (DT; Quinlan, 1986) is a traditional, frequently used, supervised learning classification method. Although the training speed is the fastest and the memory consumption is the least, it has the worst performance because of the simple single classifier. The model performances of ensemble-learning approaches, i.e., GBDT (Friedman, 2001), RF (Breiman, 2001), extremely randomized trees (ERTs; Geurts et al., 2006), and XGBoost (Chen and Guestrin, 2016), can be significantly improved by combining several weak classifiers into a strong classifier. Among them, the ERT model yields a higher estimation accuracy and a stronger spatial prediction ability than other ensemble-learning models. The LightGBM model (Ke et al., 2017) performs the best with the highest accuracy and smallest uncertainty among all tree-based machine-learning approaches considered.

The model efficiency differs among these models due to the large differences in the algorithm design frameworks. These tree-based machine-learning models can be divided into two categories. The DT, RF, and ERT models fall into the “bagging” category, which synthesizes multiple independent and unrelated weak classifiers into a strong classifier. It allows for work in parallel, which can save much time but may need more computer memory. The GBDT, XGBoost, and LightGBM models fall into the “boosting” category, which synthesizes multiple interdependent and related weak classifiers into a strong classifier. They can only work in serial, which may take much time but not too much memory. In general, the STGB model is the most time-consuming, while the STET model is the most memory-consuming. By contrast, the LightGBM model runs very fast and consumes very little computer memory, benefiting from a series of algorithm optimizations (Ke et al., 2017).

After considering spatiotemporal variations, all the newly defined space-time DT, GBDT, XGBoost, RF, ERT, and LightGBM models (i.e., STDT, STGB, STXB, STRF, STET, and STLG) show significant improvements in both overall estimation accuracy and spatial prediction ability in estimating hourly PM2.5 concentrations with reference to their original models. This further illustrates the importance of including spatiotemporal information when constructing PM2.5–AOD relationships. More importantly, the training speed of these models did not decrease much, and the memory consumption did not increase much either. In general, the STLG model shows the best performance with a high efficiency (i.e., training speed = 46 s, memory usage = 0.60 GB) among all the space-time tree-based machine-learning models. Therefore, our new STLG model is highly valuable for accurate and fast air pollution monitoring, in particular for our future study extended to the global scale.

3.3.2 Comparison with related studies

We compared Himawari-8-based hourly PM2.5 estimates at regional and national scales in China with previous related studies (Table 6). Local hourly PM2.5 concentrations retrieved from our national-scale model are more accurate than those derived from the models developed separately in local areas, e.g., the LME model (Wang et al., 2017), the GWR, SVR, RF, and DNN models in the BTH region (Sun et al., 2019) and the two-stage RF and DNN models in the YRD region (Fan et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2019). Our model also outperforms most of the statistical regression models and machine-learning models focused on the entirety of China, e.g., the I-LME, IGTWR, RF, AdaBoost, XGBoost, and their stacked models in China (Chen et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2020; T. Zhang et al., 2019). This is due to the stronger data-mining ability, considering key spatial and temporal information about air pollution (ignored in previous studies), which introduces more comprehensive factors that affect PM2.5 pollution (e.g., emission inventories).

PM2.5 has a great impact on the atmospheric environment and is also used as a key indicator in environmental health studies. It varies diurnally, affected by both natural and human factors. Previous studies have been based on data from sun-synchronous satellites which can monitor air pollution at coarse temporal scales (i.e., daily), while high-temporal-resolution and accurate information on PM2.5 is needed. In this study, the Himawari-8/AHI hourly AOD product is employed to address this issue. Moreover, considering the large volume of input data and the large errors in PM2.5 estimation using traditional methods, an efficient and accurate space-time Light Gradient Boosting Machine (i.e., STLG) model has been developed. It utilizes meteorological, human, land use, and topographical parameters and is implemented at 5 km resolution and hourly timescale to generate PM2.5 information over China. The hourly PM2.5 estimates are evaluated against surface observations, and PM2.5 spatiotemporal variations are also investigated.

The STLG model predicts hourly PM2.5 values accurately, with high out-of-sample (out-of-station) CV-R2 values of ∼ 0.81–0.85 (∼ 0.76–0.81) and low RMSE values of ∼ 11.24–15.56 (∼ 12.49–17.61) µg m−3 throughout the day. The model can also produce daily (e.g., R2 = 0.91, RMSE = 10.11 µg m−3), monthly, seasonal, and annual mean PM2.5 values (e.g., R2 = 0.98, RMSE = 1.6–3.3 µg m−3). PM2.5 varies diurnally in most areas of mainland China, where PM2.5 concentrations reach a maximum at 10:00 LT and are generally low at sunrise and sunset on a given day. PM2.5 also varies greatly on a seasonal basis, in which winter and summer experience the highest and lowest air pollution levels, respectively. Comparison results suggest that the proposed model is more accurate than traditional statistical regression models, other tree-based machine-learning models, and various models developed in previous studies. Overall, the STLG model is more efficient, having faster training speed and less memory consumption. These results illustrate that this algorithm can be useful for real-time monitoring of PM2.5 pollution in China.

PM2.5 measurements are available at http://www.cnemc.cn (CNEMC, 2020), the Himawari-8 AOD product is available at https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ptree/ (JAXA Himawari Monitor, 2020), ERA5 reanalysis products are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ (CDS, 2020), the MODIS product is available at https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (NASA, 2020), and the LandScan™ product is available at https://landscan.ornl.gov/ (ORNL, 2020). The ChinaHighPM2.5 dataset is available at https://weijing-rs.github.io/product.html (Wei, 2020).

JiW designed the research and wrote the initial draft of this manuscript. ZL, RTP, JuW, and LS reviewed and edited the paper. RL and WX helped to process the data. MC copy-edited the article. All authors made substantial contributions to this work.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Satellite and ground-based remote sensing of aerosol optical, physical, and chemical properties over China”. It is not associated with a conference.

We would like to thank Qiang Zhang at Tsinghua University for providing MEIC pollution emission data for China. Jun Wang's participation is made possible via the in-kind support from the University of Iowa.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42030606) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2017YFC1501702).

This paper was edited by Toshihiko Takemura and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

An, Z., Huang, R. J., Zhang, R., Tie, X., Li, G., Cao, J., Zhou, W., Shi, Z., Han, Y., Gu, Z., and Ji, Y.: Severe haze in northern China: a synergy of anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric processes, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 8657–8666, 2019.

Baez-Villanueva, O., Zambrano-Bigiarini, M., Beck, H., Mcnamara, I., and Thinh, N.: RF-MEP: a novel random forest method for merging gridded precipitation products and ground-based measurements, Remote Sens. Environ., 239, 111606, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111606, 2020.

Behrens, T., Schmidt, K., Viscarra, R., Gries, P., Scholten, T., and Macmillan, R.: Spatial modelling with Euclidean distance fields and machine learning, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 69, 757–770, 2018.

Bessho, K., Date, K., Hayashi, M., Ikeda, A., and Yoshida, R.: An introduction to Himawari-8/9 – Japan's new-generation geostationary meteorological satellites, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn., 2016, 94, 151–183, 2016.

Breiman, L.: Random forests, Mach. Learn., 45, 5–32, 2001.

CDS: ERA5, available at: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/, last access: 1 December 2020.

Chan, C. and Yao, X.: Air pollution in megacities in China, Atmos. Environ., 42, 1–42, 2008.

Chen, J., Yin, J., Zang, L., Zhang, T., and Zhao, M.: Stacking machine learning model for estimating hourly PM2.5 in China based on Himawari-8 aerosol optical depth data, Sci. Total Environ., 697, 134021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134021, 2019.

Chen, T. and Guestrin, C.: XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system, in: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 13–17 August 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA, 785–794, 2016.

Chen, Z., Cheng, S., Li, J., Guo, X., Wang, W., and Chen, D.: Relationship between atmospheric pollution processes and synoptic pressure patterns in northern China, Atmos. Environ., 42, 6078–6087, 2008.

CNEMC: http://www.cnemc.cn, last access: 1 December 2020.

Delfino, R. J., Sioutas, C., and Malik, S.: Potential role of ultrafine particles in associations between airborne particle mass and cardiovascular health, Environ. Health Persp., 113, 934–946, 2005.

Dobson, J., Bright, E., Coleman, P., Durfee, R., and Worley, B.: A global population database for estimating populations at risk, Photogramm. Eng. Rem. S., 66, 849–857, 2000.

Fan, W., Qin, K., Cui, Y., Li, D., and Bilal, M.: Estimation of hourly ground-level PM2.5 concentration based on Himawari-8 apparent reflectance, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 59, 76–85, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2020.2990791, 2020.

Friedman, J.: Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine, Ann. Stat., 29, 1189–1232, 2001.

Geurts, P., Ernst, D., and Wehenkel, L.: Extremely randomized trees, Mach. Learn., 63, 3–42, 2006.

Giles, D. M., Sinyuk, A., Sorokin, M. G., Schafer, J. S., Smirnov, A., Slutsker, I., Eck, T. F., Holben, B. N., Lewis, J. R., Campbell, J. R., Welton, E. J., Korkin, S. V., and Lyapustin, A. I.: Advancements in the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) Version 3 database – automated near-real-time quality control algorithm with improved cloud screening for Sun photometer aerosol optical depth (AOD) measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 169–209, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-169-2019, 2019.

Gui, K., Che, H., Zeng, Z., Wang, Y., Zhai, S., Wang, Z., Luo, M., Zhang, L., Liao, T., Zhao, H., Li, L., Zheng, Y., and Zhang, X.: Construction of a virtual PM2.5 observation network in China based on high-density surface meteorological observations using the Extreme Gradient Boosting model, Environ. Int., 141, 105801, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105801, 2020.

Huang, R., Zhang, Y., Bozzetti, C., Ho, K., Cao, J., Han, Y., Daellenbach, K., Slowik, J., Platt, S., Canonaco, F., Zotter, P., Wolf, R., Pieber, S., Bruns, E., Crippa, M., Ciarelli, G., Piazzalunga, A., Schwikowski, M., Abbaszade, G., Schnelle-Kreis, J., Zimmermann, R., An, Z., Szidat, S., Baltensperger, U., Haddad, I., and Prevot, A.: High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China, Nature, 514, 218–222, 2014.

Jacob, D. and Winner, D.: Effect of climate change on air quality, Atmos. Environ., 43, 51–63, 2009.

JAXA Himawari Monitor: https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ptree/, last access: 1 December 2020.

Kampa, M. and Castanas, E.: Human health effects of air pollution, Environ. Pollut., 151, 362–367, 2008.

Ke, G., Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W., Ye, Q., and Liu, T.: LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree, in: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, ACM, Long Beach, CA, USA, 3149–3157, available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3294996.3295074 (last access: 1 January 2020), 2017.

Kim, K., Kabir, E., and Kabir, S.: A review on the human health impact of airborne particulate matter, Environ. Int., 74, 136–143, 2015.

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D., and Pozzer, A.: The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale, Nature, 525, 367–371, 2015.

Lennartson, E. M., Wang, J., Gu, J., Castro Garcia, L., Ge, C., Gao, M., Choi, M., Saide, P. E., Carmichael, G. R., Kim, J., and Janz, S. J.: Diurnal variation of aerosol optical depth and PM2.5 in South Korea: a synthesis from AERONET, satellite (GOCI), KORUS-AQ observation, and the WRF-Chem model, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 15125–15144, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-15125-2018, 2018.

Letu, H., Yang, K., Nakajima, T., Ishimoto, H., Nagao, T., Riedi, J., Baran, A., Ma, R., Wang, T., Shang, H., Khatri, P., Chen, L., Shi, C., and Shi, J.: High-resolution retrieval of cloud microphysical properties and surface solar radiation using Himawari-8/AHI next-generation geostationary satellite, Remote Sens. Environ., 239, 111583, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111583, 2020.

Li, M., Liu, H., Geng, G., Hong, C., Liu, F., Song, Y., Tong, D., Zheng, B., Cui, H., Man, H., Zhang, Q., and He, K.: Anthropogenic emission inventories in China: a review, Natl. Sci. Rev., 4, 834–866, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwx150, 2017.

Li, Z., Guo, J., Ding, A., Liao, H., Liu, J., Sun, Y., Wang, T., Xue, H., Zhang, H., and Zhu, B.: Aerosols and boundary-layer interactions and impact on air quality, Natl. Sci. Rev., 4, 810–833, 2017.

Li, Z., Xu, H., Li, K., Li, D., Xie, Y., Li, L., Zhang, Y., Gu, X., Zhao, W., Tian, Q., Deng, R., Su, X., Huang, B., Qiao, Y., Cui, W., Hu, Y., Gong, C., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, J., Du, W., Pan, Z., Li, Z., and Bu, D.: Comprehensive study of optical, physical, chemical, and radiative properties of total columnar atmospheric aerosols over China: an overview of Sun–Sky Radiometer Observation Network (SONET) measurements, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 99, 739–755, 2018.

Li, Z., Guo, J., Ding, A., Liao, H., Liu, J., Sun, Y., Wang, T., Xue, H., Zhang, H., and Zhu, B.: East Asian Study of Tropospheric Aerosols and their Impact on Regional Clouds, Precipitation, and Climate (EAST-AIRCPC), J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 124, 13026–13054, 2019.

Liu, J., Weng, F., Li, Z., and Cribb, M.: Hourly PM2.5 estimates from a geostationary satellite based on an ensemble learning algorithm and their spatiotemporal patterns over central East China, Remote Sens.-Basel, 11, 2120, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11182120, 2019.

Liu, Y., Sarnat, J., Kilaru, V., Jacob, D., and Koutrakis, P.: Estimating ground-level PM2.5 in the eastern United States using satellite remote sensing, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 3269–78, 2005.

Liu, Y., Franklin, M., Kahn, R., and Koutrakis, P.: Using aerosol optical thickness to predict ground-level PM2.5 concentrations in the St. Louis area: a comparison between MISR and MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ., 107, 33–44, 2007.

Ma, Z., Hu, X., Huang, L., Bi, J., and Liu, Y.: Estimating ground-level PM2.5 in China using satellite remote sensing, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 7436–7444, 2014.

NASA: EARTHDATA, available at: https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/, last access: 1 December 2020.

ORNL: LandScan, available at: https://landscan.ornl.gov/, last access: 1 December 2020.

Quinlan, J.: Induction on decision tree, Mach. Learn., 1, 81–106, 1986.

Ramanathan, V. and Feng, Y.: Air pollution, greenhouse gases and climate change: global and regional perspectives, Atmos. Environ., 43, 37–50, 2009.

Rodriguez, J. D., Perez, A., and Lozano, J. A.: Sensitivity analysis of k-fold cross-validation in prediction error estimation, IEEE T. Pattern Anal., 32, 569–575, 2010.

Shi, H.: Best-first decision tree learning, PhD thesis, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2007.

Su, T., Li, Z., and Kahn, R.: Relationships between the planetary boundary layer height and surface pollutants derived from lidar observations over China: regional pattern and influencing factors, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 15921–15935, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-15921-2018, 2018.

Sun, Y., Zhuang, G., Wang, Y., Han, L., Guo, J., Dan, M., Zhang, W., Wang, Z., and Hao, Z.: The air-borne particulate pollution in Beijing – concentration, composition, distribution and sources, Atmos. Environ., 38, 5991–6004, 2004.

Sun, Y., Zeng, Q., Geng, B., Lin, X., Sude, B., and Chen, L.: Deep learning architecture for estimating hourly ground-level PM2.5 using satellite remote sensing, IEEE Geosci. Remote S., 16, 1343–1347, 2019.

Tang, D., Liu, D., Tang, Y., Seyler, B., Deng, X., and Zhan, Y.: Comparison of GOCI and Himawari-8 aerosol optical depth for deriving full coverage hourly PM2.5 across the Yangtze River Delta, Atmos. Environ., 217, 116973, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.116973, 2019.

van Donkelaar, A., Martin, R., and Park, R.: Estimating ground-level PM2.5 using aerosol optical depth determined from satellite remote sensing, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 111, D21201, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006996, 2006.

Wang, J. and Christopher, S.: Intercomparison between satellite-derived aerosol optical thickness and PM2.5 mass: Implication for air quality studies, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 2095, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018174, 2003.

Wang, W., Mao, F., Du, L., Pan, Z., Gong, W., and Fang, S.: Deriving hourly PM2.5 concentrations from Himawari-8 AODs over Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei in China, Remote Sens.-Basel, 9, 858, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9080858, 2017.

Wang, X., Dickinson, R., Su, L., Zhou, C., and Wang, K.: PM2.5 pollution in China and how it has been exacerbated by terrain and meteorological conditions, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 99, 105–119, 2018.

Wei, J.: ChinaHighAirPollutants (CHAP), available at: https://weijing-rs.github.io/product.html, last access: 1 December 2020.

Wei, J., Huang, W., Li, Z., Xue, W., Peng, Y., Sun, L., and Cribb, M.: Estimating 1-km-resolution PM2.5 concentrations across China using the space-time random forest approach, Remote Sens. Environ., 231, 111221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111221, 2019a.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Guo, J., Sun, L., Huang, W., Xue, W., Fan, T, and Cribb, M.: Satellite-derived 1-km-resolution PM1 concentrations from 2014 to 2018 across China, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 13265–13274, 2019b.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Sun, L., Peng, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, Z., Su, T., Feng, L., Cai, Z., and Wu, H.: Evaluation and uncertainty estimate of the next-generation geostationary meteorological Himawari-8/AHI aerosol products, Sci. Total Environ., 692, 879–891, 2019c.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Peng, Y., and Sun, L.: MODIS Collection 6.1 aerosol optical depth products over land and ocean: validation and comparison, Atmos. Environ., 201, 428–440, 2019d.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Cribb, M., Huang, W., Xue, W., Sun, L., Guo, J., Peng, Y., Li, J., Lyapustin, A., Liu, L., Wu, H., and Song, Y.: Improved 1 km resolution PM2.5 estimates across China using enhanced space–time extremely randomized trees, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 3273–3289, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-3273-2020, 2020.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Lyapustin, A., Sun, L., Peng, Y., Xue, W., Su, T., and Cribb, M.: Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: spatiotemporal variations and policy implications, Remote Sens. Environ., 252, 112136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.112136, 2021a.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Xue, W., Sun, L., Fan, T., Liu, L., Su, T., and Cribb, M.: The ChinaHighPM10 dataset: generation, validation, and spatiotemporal variations from 2015 to 2019 across China, Environ. Int., 146, 106290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106290, 2021b.

Wei, J., Li, Z., Sun, L., Xue, X., Ma, Z., Liu, L., Fan, T., and Cribb, M.: Extending the EOS long-term PM2.5 data records since 2013 in China: application to the VIIRS Deep Blue aerosol products, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 59, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2021.3050999, 2021c.

Wu, J., Yao, F., Si, M., and Li, W.: VIIRS-based remote sensing estimation of ground-level PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei: a spatiotemporal statistical model, Remote Sens. Environ., 184, 316–328, 2016.

Xue, Y., Li, Y., Guang, J., Tugui, A., She, L., Qin, K., Fan, C., Che, Y., Xie, Y., Wen, Y., and Wang, Z.: Hourly PM2.5 estimation over central and eastern China based on Himawari-8 data, Remote Sens.-Basel, 12, 855, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12050855, 2020.

Yao, F., Wu, J., Li, W., and Peng, J.: A spatially structured adaptive two-stage model for retrieving ground-level PM2.5 concentrations from VIIRS AOD in China, ISPRS J. Photogramm., 151, 263–276, 2019.

Yoshida, M, Kikuchi, M., Nagao, T., Murakami, H., Nomaki, T., and Higurashi, A.: Common retrieval of aerosol properties for imaging satellite sensors, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn., 96b, 193–209, 2018.

Zhang, Q., Zheng, Y., Tong, D., Shao, M., and Hao, J.: Drivers of improved PM2.5 air quality in china from 2013 to 2017. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 24463–24469, 2019.

Zhang, T., Zang, L., Wan, Y., Wang, W., and Zhang, Y.: Ground-level PM2.5 estimation over urban agglomerations in China with high spatiotemporal resolution based on Himawari-8. Sci. Total Environ., 676, 535–544, 2019.

Zhang, T., He, W., Zheng, H., Cui, Y., Song, H., and Fu, S.: Satellite-based ground PM2.5 estimation using a gradient boosting decision tree, Chemosphere, 268, 128801, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128801, 2020.

Zheng, B., Tong, D., Li, M., Liu, F., Hong, C., Geng, G., Li, H., Li, X., Peng, L., Qi, J., Yan, L., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Zheng, Y., He, K., and Zhang, Q.: Trends in China's anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 14095–14111, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-14095-2018, 2018.