the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Source-resolved volatility and oxidation state decoupling in wintertime organic aerosols in Seoul

Jiwoo Jeong

Jihye Moon

Hyun Gu Kang

Organic aerosols (OA) are key components of wintertime urban haze, but the relationship between their oxidation state and volatility – critical for understanding aerosol evolution and improving model predictions – remains poorly constrained. While oxidation–volatility decoupling has been observed in laboratory studies, field-based evidence under real-world conditions is scarce, particularly during severe haze episodes. This study presents a field-based investigation of OA sources and their volatility characteristics in Seoul during a winter haze period, using a thermodenuder coupled with a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS).

Positive matrix factorization resolved six OA factors: hydrocarbon-like OA, cooking, biomass burning, nitrogen-containing OA (NOA), less-oxidized oxygenated OA (LO-OOA), and more-oxidized OOA (MO-OOA). Despite having the highest oxygen-to-carbon ratio (∼1.15), MO-OOA exhibited unexpectedly high volatility, indicating a decoupling between oxidation state and volatility. We attribute this to fragmentation-driven aging and autoxidation under stagnant conditions with limited OH exposure. In contrast, LO-OOA showed lower volatility and more typical oxidative behavior.

Additionally, NOA – a rarely resolved factor in wintertime field studies – was prominent during cold, humid, and stagnant conditions and exhibited chemical and volatility features similar to biomass burning OA, suggesting a shared combustion origin and meteorological sensitivity.

These findings provide one of the few field-based demonstrations of oxidation–volatility decoupling in ambient OA and highlight how source-specific properties and meteorology influence OA evolution. The results underscore the need to refine OA representation in chemical transport models, especially under haze conditions.

- Article

(4050 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3159 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Atmospheric aerosols affect both human health and the environment by reducing visibility (Ghim et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2013) and contributing to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (Hamanaka and Mutlu, 2018; Manisalidis et al., 2020). In addition, aerosols play a significant role in climate change by scattering or absorbing solar radiation and modifying cloud properties (IPCC, 2021). Among the various aerosol components – including sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, chloride, crustal materials, and water – organic aerosols (OA) are particularly important to characterize, as they account for 20 %–90 % of submicron particulate matter (Zhang et al., 2007). Identifying OA sources and understanding their behavior are critical for effective air quality management; however, this is particularly challenging due to the vast diversity and dynamic nature of OA compounds, which originate from both natural and anthropogenic sources. Unlike inorganic aerosols, organic aerosols (OAs) evolve continuously through complex atmospheric reactions, influenced by emission sources, meteorological conditions, and aerosol properties (Jimenez et al., 2009; Hallquist et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2007; Donahue et al., 2006; Ng et al., 2010; Cappa and Jimenez, 2010).

Volatility is a key parameter for characterizing organic aerosol (OA) properties, as it governs gas-to-particle partitioning behavior and directly influences particle formation yields (Sinha et al., 2023). The classification of OA species based on their volatility – from extremely low-volatility (ELVOC) to semi-volatile (SVOC) and intermediate-volatility (IVOC) compounds – is central to the conceptual framework of secondary OA (SOA) formation and growth (Donahue et al., 2006). It also affects atmospheric lifetimes and human exposure by determining how long aerosols remain suspended in the atmosphere (Glasius and Goldstein, 2016). Therefore, accurately capturing OA volatility is essential for improving predictions of OA concentrations and their environmental and health impacts. However, chemical transport models often significantly underestimate OA mass compared to observations (Jiang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2017), largely due to incomplete precursor inventories and simplified treatment of processes affecting OA volatility. For instance, aging – through oxidation reactions such as functionalization and fragmentation – can significantly alter volatility by changing OA chemical structure (Robinson et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2016). Early volatility studies primarily utilized thermal denuders (TD) coupled with various detection instruments to investigate the thermal properties of bulk OA (Huffman et al., 2008). The subsequent coupling of TD with the Aerosol Mass Spectrometer allowed for component-resolved volatility measurements, providing critical, quantitative insight into the properties of OA factors (e.g., SV-OOA vs. LV-OOA) across different regions (Paciga et al., 2016; Cappa and Jimenez, 2010). These component-resolved volatility data are often used to constrain the Volatility Basis Set (VBS) – the current state-of-the-art framework for modeling OA partitioning and evolution (Donahue et al., 2006). However, a limitation in many field studies is that the TD-AMS thermogram data are rarely translated into quantitative VBS distributions for individual OA factors, which limits their direct use in chemical transport models. Furthermore, the volatility of OOA during extreme haze conditions, where the expected inverse correlation between oxidation (O:C) and volatility can break down (Jimenez et al., 2009), remains poorly characterized, particularly in East Asia's highly polluted winter environments. A recent study in Korea further highlighted the importance of accounting for such processes when interpreting OA volatility under ambient conditions (Kang et al., 2022). Given its central role in OA formation, reaction, and atmospheric persistence, volatility analysis is critical for bridging the gap between measurements and model performance.

Traditionally, due to the complexity and variability of OA, the oxygen-to-carbon (O:C) ratio has been used as a proxy for estimating volatility. In general, higher O:C values indicate greater oxidation and lower volatility (Jimenez et al., 2009). Accordingly, many field studies classify oxygenated OA (OOA) into semi-volatile OOA (SV-OOA) and low-volatility OOA (LV-OOA) based on their O:C ratios (Ng et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2010; Mohr et al., 2012). However, this relationship is not always straightforward. Fragmentation during oxidation can increase both O:C and volatility simultaneously, disrupting the expected inverse correlation (Jimenez et al., 2009). In laboratory experiments, yields of highly oxidized SOA have been observed to decrease due to fragmentation (Xu et al., 2014; Grieshop et al., 2009). These findings suggest that while O:C can offer useful insights, it is insufficient alone to represent OA volatility. Direct volatility measurements, especially when paired with chemical composition data, are necessary to improve our understanding of OA sources and aging processes.

In this study, we investigate the sources and volatility characteristics of OA in Seoul during winter. Wintertime OA presents additional challenges due to its high complexity. During winter, emissions from combustion sources such as biomass burning and residential heating significantly increase, contributing large amounts of primary OA (Kim et al., 2017). Meanwhile, low ambient temperatures and reduced photochemical activity affect the formation and evolution of secondary OA (SOA). Frequent haze events further complicate the aerosol properties by extending aging times and increasing particle loadings. These overlapping sources and atmospheric conditions make winter OA particularly difficult to characterize and predict. Despite Seoul's significance for air quality management, comprehensive studies on OA volatility during winter remain limited. To address these goals, we conducted real-time, high-resolution measurements using a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS) coupled with a thermodenuder (TD). The objectives of this study are to: (1) improve the understanding of wintertime OA in Seoul, (2) characterize the volatility of OA associated with different sources, and (3) explore the relationship between OA volatility and chemical composition.

2.1 Sampling site and measurement period

We conducted continuous real-time measurements in Seoul, South Korea, from 28 November to 28 December 2019. The sampling site was located in the northeastern part of the city (37.60° N, 127.05° E), approximately 7 km from the city center, surrounded by major roadways and mixed commercial–residential land use. Air samples were collected at an elevation of approximately 60 m above sea level, on the fifth floor of a building. A detailed site description has been reported previously for winter Seoul (Kim et al., 2017). During this period, the average ambient temperature was 1.76±4.3 °C, and the average relative humidity (RH) was 56.9±17.5 %, based on data from the Korea Meteorological Administration (http://www.kma.go.kr, last access: 15 January 2026).

2.2 Instrumentation and measurements

The physico-chemical properties of non-refractory PM1 (NR-PM1) species – including sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, chloride, and organics – were measured using an Aerodyne high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS) (DeCarlo et al., 2006). PM1 mass in this study is taken as NR-PM1 (from AMS) + black carbon (BC; measured by MAAP), which is appropriate for winter Seoul where refractory PM1 (metal/sea-salt/crustal) is minor and dust events were excluded (e.g., Kim et al., 2017; Nault et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2022; Jeon et al., 2023).Data were acquired at 2.5 min intervals, alternating between V and W modes. The V mode provides higher sensitivity but lower resolution, suitable for mass quantification, whereas the W mode offers higher mass resolution but lower sensitivity, used here for OA source apportionment. Simultaneously, black carbon (BC) concentrations were measured at 1 min intervals using a multi-angle absorption photometer (MAAP; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Total PM1 mass was calculated as the sum of NR-PM1 and BC.

Hourly trace gas concentrations (CO, O3, NO2, SO2) were obtained from the Gireum air quality monitoring station (37.61° N, 127.03° E), managed by the Seoul Research Institute of Public Health and Environment. Meteorological data (temperature, RH, wind speed/direction) were collected from the nearby Jungreung site (37.61° N, 127.00° E). All data are reported in Korea Standard Time (UTC+9).

To examine aerosol volatility, a thermodenuder (TD; Envalytix LLC) was installed upstream of the HR-ToF-AMS. Details are provided in Sect. S1 in the Supplement (Kang et al., 2022). Briefly, ambient flow alternated every 5 min between a TD line and a bypass line at 1.1 L min−1. Residence time in the TD line was ∼6.3 s. The TD setup included a 50 cm heating section followed by an adsorption unit. Heated particles were stripped of volatile species, while the downstream carbon-packed section prevented recondensation. TD temperature cycled through 12 steps (30 to 200 °C), with each step lasting 10 min (total cycle = 120 min). AMS V and W modes were alternated during the same cycle. The heater was pre-adjusted to the next temperature while the bypass was active.

2.3 Data analysis

2.3.1 Data analysis and OA source apportionment

HR-AMS data were processed using SQUIRREL v1.65B and PIKA v1.25B. Mass concentrations of non-refractory PM1 (NR-PM1) species were derived from V-mode data, while high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) and the elemental composition of organic aerosols (OA) were obtained from W-mode data. NR-PM1 quantification followed established AMS protocols (Ulbrich et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). Both the bypass and TD streams were processed using a time-resolved, composition-dependent collection efficiency CE(t) following Middlebrook et al. (2012). TD heating can modify particle water and phase state/mixing and thereby influence CE beyond composition (Huffman et al., 2009), but prior TD–AMS studies indicate that such effects are modest and largely multiplicative, which do not distort thermogram shapes or T50 ordering (Faulhaber et al., 2009; Cappa and Jimenez, 2010). In our data, the CE(t) statistics for the two lines were similar (campaign-average CE: TD ; bypass ; %, below the combined uncertainty ≈0.09). We therefore report volatility metrics with these line-specific CE(t) corrections applied and interpret potential residual CE effects as minor. For organics,elemental ratios (O:C, H:C, and ) were calculated using the Improved-Ambient (IA) method (Canagaratna et al., 2015). Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) was applied to the HRMS of organics using the PMF2 algorithm (v4.2, robust mode) (Paatero and Tapper, 1994). The HRMS and corresponding error matrices from PIKA were analyzed using the PMF Evaluation Tool v2.05 (Ulbrich et al., 2009). Data pretreatment followed established protocols (Ulbrich et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). A six-factor solution (fPeak =0; _expected = 3.56) was selected as optimal (Fig. S1). The resolved OA sources included hydrocarbon-like OA (HOA; 14 %; ), cooking-related OA (COA; 21 %; ), nitrogen-enriched OA (NOA; 2 %; ), biomass-burning OA (BBOA; 13 %; ), less-oxidized oxygenated OA (LO-OOA; 30 %; ), and more-oxidized oxygenated OA (MO-OOA; 20 %; ) (Figs. S2 and S3). Alternative five- and seven-factor solutions were also evaluated. In the five-factor solution, the biomass burning source was not clearly resolved and appeared to be distributed across multiple factors. In the seven-factor solution, BBOA was further split into two separate factors without clear distinction or added interpretive value, making the six-factor solution the most physically meaningful and interpretable (Figs. S4 and S5). To ensure the statistical robustness of this solution, we calculated uncertainties for each PMF factor using the bootstrap method (100 iterations) with the PET toolkit (v2.05) (EPA, 2014; Waked et al., 2014; Soleimani et al., 2022) (Table S2 and Fig. S13).

2.3.2 Thermogram and volatility estimation

The chemical composition dependent mass fraction remaining (MFR) was derived at each TD temperature by dividing the corrected mass concentration of the TD line [p] by the average of the adjacent bypass lines [p−1] and [p+1]. Thermograms were corrected for particle loss, estimated using reference substances like NaCl, which exhibit minimal evaporation (Huffman et al., 2009; Saha et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2022). OA factor concentrations at each TD temperature were derived via multivariate linear regression between post-TD HRMS and ambient OA factor HRMS profiles as described in Zhou et al., 2017.

Volatility distributions were modeled using the thermodenuder mass transfer model from Riipinen et al. (2010) and Karnezi et al. (2014), implemented in Igor Pro 9 (Kang et al., 2022). OA mass was distributed into eight logarithmic saturation concentration bins (C*: 1000 to 0.0001 µg m−3). Modeled MFRs were fit to observations using Igor's “FuncFit” function, repeated 1000 times per OA factor to determine best-fit results. The model assumes no thermal decomposition and includes adjustable parameters: mass accommodation coefficient (αm) and enthalpy of vaporization (ΔHexp), randomly sampled within literature-based ranges (Table S1).

3.1 Overview of PM1 composition and OA sources

We conducted continuous measurements from 28 November to 28 December 2019, characterizing a winter period with a mean PM1 concentration of 27.8±15.3 µg m−3. This concentration is characterized as moderate; it closely matches historical winter PM1 means in Seoul (Kim et al., 2017) and implies an equivalent PM2.5 concentration is about 34.8 µg m−3 (using a Korea-specific PM1 PM2.5≈0.8 (Kwon et al., 2023), which is near the national 24 h PM2.5 standard (35 µg m−3) (AirKorea). The full co-evolution of PM1, gaseous pollutants, and meteorological conditions is provided in Fig. S6, showing an average ambient temperature of 1.76±4.3 °C and average relative humidity (RH) of 56.9±17.5 % during the study.

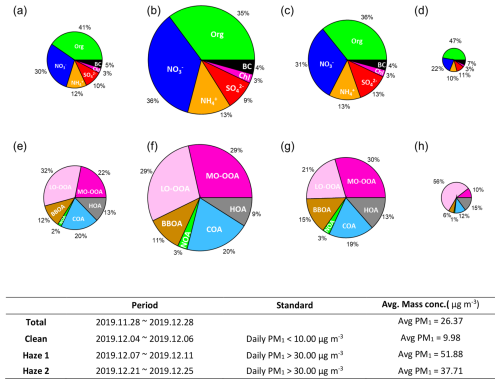

Figure 1Compositional pie charts of PM1 species for (a) the entire study period, (b) haze period 1, (c) haze period 2, and (d) a clean period; and of each OA source for (e) the entire study period, (f) haze period 1, (g) haze period 2, and (h) the clean period. Table: Standard and average PM1 mass concentrations during the entire study period, haze period 1, haze period 2, and the clean period.

Figure 1 summarizes the overall non-refractory submicron aerosol (NR-PM1) composition and the identified OA factors. Organics (41 %) and nitrate (30 %) were the most abundant chemical components of PM1, followed by ammonium (12 %), sulfate (10 %), BC (5 %), and chloride (3 %) (Fig. 1a). Among the organic aerosols, six OA factors were identified during the winter of 2019: hydrocarbon-like OA (HOA; 14 %; ), cooking-related OA (COA; 21 %; ), nitrogen-enriched OA (NOA; 2 %; ), biomass burning OA (BBOA; 13 %; ), and two types of secondary organic aerosols – less-oxidized oxygenated OA (LO-OOA; 30 %; ) and more-oxidized oxygenated OA (MO-OOA; 20 %; ) (Figs. 1e and S2). These compositions are consistent with previous wintertime observations in Kim et al. (2017), with the exception of newly resolved NOA source. In the following sections, we describe each OA factor in the order of secondary OA (SOA), primary OA (POA) and finally introduce NOA, which – while related to combustion POA – emerged as a distinct, nitrogen-rich factor under the winter conditions of this study.

PM1 mass concentrations varied widely, ranging from 4.61 to 91.4 µg m−3, largely due to two severe haze episodes that occurred between 7–12 December and 22–26 December (Fig. 1). During these episodes, average concentrations increased significantly, driven primarily by elevated levels of nitrate and organic aerosols – particularly MO-OOA and NOA (Fig. 1f, g). Back-trajectory clustering shows frequent short-range recirculation over the Seoul Metropolitan Area during haze (Cluster 1; Fig. S8), and the time series indicates persistently low surface wind speeds during these periods (1.73±0.89 vs. 2.34±1.18 (clean)) (Fig. S6). These patterns indicate stagnation-driven accumulation of local emissions, consistent with the simultaneous increase of MO-OOA and NOA that are examined in detail in subsequent sections. Such haze episodes, characterized by local emission buildup and secondary aerosol production, are a typical wintertime feature, as also reported in Kim et al. (2017).

3.1.1 Secondary organic aerosols (SOA)

In this study, two OOA factors – more-oxidized OOA (MO-OOA) and less-oxidized OOA (LO-OOA) – were identified, together accounting for approximately half of the total organic aerosol (OA) mass. This fraction is notably higher than that reported in previous wintertime urban studies (Kim et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2007). Both OOAs exhibited characteristic mass spectral features, including prominent peaks at 44 (CO) and 43 (C2H3O+), which are widely recognized as markers of oxygenated organics (Figs. S2e, S3f). The oxygen-to-carbon (O:C) ratios for MO-OOA and LO-OOA were 1.15 and 0.68, respectively, indicating both factors are highly oxidized relative to the primary OA factors (HOA, COA, BBOA) and that MO-OOA is substantially more oxidized than LO-OOA. The O:C ratio of MO-OOA was especially elevated, exceeding those reported in previous Seoul campaigns – 0.68 in winter 2015 (Kim et al., 2017), 0.99 in spring 2019 (Kim et al., 2020), and 0.78 in fall 2019 (Jeon et al., 2023) – while the LO-OOA ratio was within a similar range.

MO-OOA showed strong correlations with secondary inorganic species such as nitrate (r=0.90), ammonium (r=0.92), and sulfate (r=0.81), consistent with its formation through regional and local photochemical aging processes (Fig. S3). In contrast, LO-OOA exhibited only modest correlations with sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium (r=0.50, 0.51, and 0.42, respectively). This weaker coupling indicates that LO-OOA represents a less aged oxygenated OA component (fresh SOA), distinguishable from the more aged, highly processed MO-OOA which tracks closely with secondary inorganic species. Regarding potential primary influence, LO-OOA does not exhibit a pronounced 60 (levoglucosan) signal (Figs. S2 and 9). While the levoglucosan marker (f60) is known to diminish with atmospheric aging and can become weak or undetectable downwind (Hennigan et al., 2010; Cubison et al., 2011), the absence of a distinct peak combined with the separation from inorganic salts suggests that LO-OOA is best characterized as freshly formed secondary organic aerosol likely originating from the rapid oxidation of local anthropogenic precursors.

3.1.2 Primary organic aerosols (POA)

Three primary organic aerosol (POA) factors were identified in this study: hydrocarbon-like OA (HOA), cooking-related OA (COA), and biomass burning OA (BBOA). These three components exhibited mass spectral and temporal characteristics consistent with previous observations in Seoul and other urban environments. HOA was characterized by dominant alkyl fragment ions (CnH and CnH; Fig. S2a) and a low O:C ratio (0.13), consistent with traffic-related emissions (0.05–0.25) (Canagaratna et al., 2015). It showed strong correlations with vehicle-related ions C3H (r=0.79) and C4H (r=0.86) (Kim et al., 2017; Canagaratna et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005), and exhibited a distinct morning rush hour peak (06:00–08:00), followed by a decrease likely driven by boundary layer expansion (Fig. S3a).

COA, accounting for 21 % of OA, showed higher contributions from oxygenated ions than HOA, with tracer peaks at 55,84 and 98 (Fig. S2b) consistent with cooking emissions (Sun et al., 2011). COA showed an enhanced signal at 55 relative to 57, with a ratio of 3.11, substantially larger than that of HOA (1.10). This elevated ratio is consistent with previously reported AMS COA spectra in urban environments (e.g., Allan et al., 2010; Mohr et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2011), supporting our factor assignment. It correlated strongly with cooking-related ions such as C3H3O+ (r=0.94), C5H8O+ (r=0.96), and C6H10O+ (r=0.98) (Fig. S3h), and displayed prominent peaks during lunch and dinner hours, reflecting typical cooking activity patterns.

BBOA was identified based on characteristic ions at 60 (C2H4O) and 73 (C3H5O+), both of which are associated with levoglucosan – a well-established tracer for biomass burning (Simoneit, 2002). Its relatively high f60 and low f44 values (Fig. S9) indicate that the BBOA observed in this study was relatively fresh and had not undergone extensive atmospheric aging (Cubison et al., 2011). Regarding source location, several pathways can influence Seoul's biomass burning signature. First, urban/peri-urban small-scale burning (e.g., solid-fuel use in select households, restaurant charcoal use, and intermittent waste burning) has been reported and can enhance BBOA locally (Kim et al., 2017). Second, nearby agricultural-residue burning in surrounding provinces occurs seasonally and can episodically impact the metropolitan area (Han et al., 2022). Third, regional transport from upwind regions (e.g., northeastern China/North Korea) can bring biomass burning influenced air masses under northerly/northwesterly flow (Lamb et al., 2018; Nault et al., 2018). In this dataset, the nighttime and early-morning enhancements and trajectory clusters showing regional recirculation indicate a predominantly local/near-source contribution during the study period, with episodic non-local influences remaining possible (Fig. S8).

Nitrogen-containing organic aerosol (NOA)

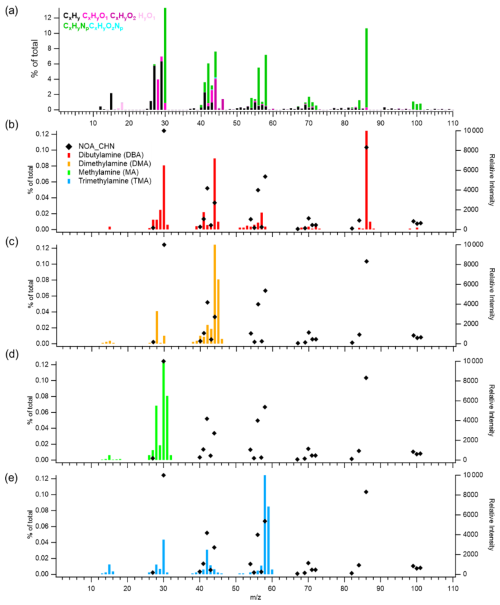

A distinct nitrogen-containing organic aerosol (NOA) factor was resolved in this study, whereas earlier wintertime AMS–PMF analyses in Seoul did not isolate such a component. The NOA factor exhibited the highest nitrogen-to-carbon (N:C) ratio (0.22) and the lowest oxygen-to-carbon (O:C) ratio (0.19) among all POA factors (Fig. S2), indicating a chemically reduced, nitrogen-rich composition. The NOA mass spectrum was dominated by amine-related fragments including 30 (CHN+), 44 (CHN+), 58 (CHN+), and 86 (CHN+) (Fig. 3a). The spectral signature of the factor is defined by the characteristic dominance of the 44 fragment, which typically serves as the primary marker for dimethylamine (DMA)-related species, closely followed by 58 (trimethylamine, TMA) and 30 (methylamine, MA). This profile is in strong agreement with NOA factors resolved via PMF in other polluted environments. For instance, the dominance of 44 and 30 aligns with amine factors reported in New York City (Sun et al., 2011) and Pasadena, California (Hayes et al., 2013). This DMA-dominated signature is also consistent with seasonal characterization of organic nitrogen in Beijing (Xu et al., 2017) and Po Valley, Italy (Saarikoski et al., 2012), reinforcing the common chemical signature of reduced organic nitrogen across diverse urban and regional environments.

In this study, NOA contributed approximately 2 % of total OA, comparable to urban contributions reported in Guangzhou (3 %; Chen et al., 2021), Pasadena (5 %; Hayes et al., 2013), and New York (5.8 %; Sun et al., 2011). These similarities suggest that the NOA factor observed in Seoul reflects a broader class of urban wintertime reduced-nitrogen aerosols rather than a site-specific anomaly. Furthermore, the presence of non-negligible signals at 58 and 86 supports the contribution of slightly larger alkylamines, a pattern that aligns well with established AMS laboratory reference spectra (Ge et al., 2011a; Silva et al., 2008). In most urban environments, the detectability of NOA appears to depend strongly on the interplay between emission strength, stagnation, and humidity – which together govern the particle-phase partitioning of volatile amines.

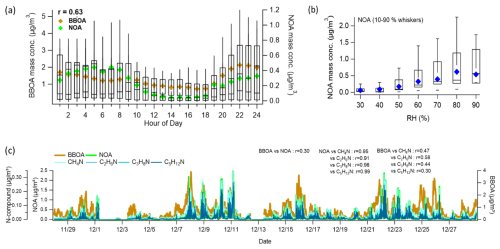

Figure 2(a) Diurnal mean profiles of NOA and BBOA. Whiskers denote the 90th and 10th percentiles; box edges represent the 75th and 25th percentiles; the horizontal line indicates the median, and the colored marker shows the mean. The diurnal correlation between NOA and BBOA mean values is 0.63. (b) Relative humidity (RH)-binned nighttime (19:00–05:00) profile of NOA. Box and whisker definitions are the same as in panel (a). (c) Time series of NOA, BBOA, and amine-related ions (CH4N+, C2H6N+, C3H8N+, C5H12N+), along with their correlations with NOA and BBOA.

Figure 3Mass spectra of (a) the NOA factor resolved by PMF analysis in this study, and reference spectra of amines from the NIST library: (b) dibutylamine (DBA), (c) dimethylamine (DMA), (d) methylamine (MA), and (e) trimethylamine (TMA). In panels (b)–(e), the left y axis indicates the contribution of CHN-containing ions in the NOA factor (% of total), while the right y axis shows the relative intensity of each compound's mass spectrum from the NIST library.

These amines are commonly emitted during the combustion of nitrogen-rich biomass and proteinaceous materials and are frequently associated with biomass-burning emissions (Ge et al., 2011a). Previous molecular analyses in Seoul also indicate DMA, MA, and TMA as the dominant amine species in December (Baek et al., 2022). While other amines such as triethylamine (TEA), diethylamine (DEA), and ethylamine (EA) may contribute via industrial/solvent pathways (e.g., chemical manufacturing, petrochemical corridors, wastewater treatment), our HR-AMS spectra are dominated by small alkylamine fragments ( 30, 44, 58, 86) and the diurnal behavior co-varies with combustion markers (Fig. 2), indicating a primarily combustion-linked influence. Nevertheless, recent urban measurements and sector-based analyses show that industrial activities can contribute measurable amines in cities (Tiszenkel et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2015; Mao et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2023). Accordingly, a minor NOA contribution from solvent/industrial amines cannot be excluded. NOA exhibited a nighttime–early-morning enhancement (Fig. 2a), similar to BBOA, indicating that both factors are influenced by wintertime combustion and residential heating, which are known sources of small alkylamines and amides (You et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2023). Strong correlations of NOA with CH4N+ (r=0.95) and C2H6N+ (r=0.91) (Fig. 2) further support the presence of reduced-nitrogen species associated with these combustion activities. However, the time series of NOA and BBOA are not strongly correlated (Figs. 2 and S7). This contrast reflects their differing behaviors: BBOA follows a relatively regular daily emission pattern, whereas NOA appears predominantly during stagnant haze periods (Fig. 1) when cold, humid, and low-wind conditions allow semi-volatile amines to partition to the particle phase and form low-volatility aminium salts. Thus, NOA in wintertime Seoul likely reflects a combination of shared primary combustion influences and enhanced secondary processing of amine-containing precursors under meteorological conditions that favor partitioning and accumulation.

Detection of particulate NOA using real time measurement has been challenging due to its low concentration and high volatility. Although Baek et al. (2022) identified nitrogen-containing species in Seoul via year-round filter-based molecular analysis, PMF-based resolution of NOA in real time has not been previously reported. The successful identification in this study is likely attributable to favorable winter meteorological conditions – specifically low temperatures (−0.24 °C) and persistently high relative humidity (∼57 %) compared to the 2017 winter season (Kim et al., 2017) – that enhanced gas-to-particle partitioning of semi-volatile amines, thereby enabling their detection (Fig. S2). NOA concentrations frequently exceeded 1 µg m−3 when RH surpassed 60 % (Fig. 2), supporting the importance of RH-driven partitioning and the subsequent formation of low-volatility aminium salts (Rovelli et al., 2017). Although extremely low temperatures may inhibit NOA formation due to the transition of aerosol particles into solid phase (Ge et al., 2011b; Srivastava et al., 2022), the combination of consistently cold and humid conditions during the measurement period likely promoted the partitioning of semi-volatile amines into the particle phase. In addition, episodic haze events further elevated NOA levels, increasing its contribution to OA from 1 % during clean periods to as much as 3 % (Fig. 1f–h). These high-concentration events likely improved the signal-to-noise ratio, facilitating PMF resolution. Back-trajectory clustering indicates that NOA-enhanced events were dominated by short-range recirculation (Cluster 1; Fig. S7), consistent with the short atmospheric lifetimes and high reactivity of alkylamines (Nielsen et al., 2012; Yu and Luo, 2014). Overall, the factor reflects semi-volatile, reduced-nitrogen species originating from primary urban combustion sources, with their observed particle-phase mass amplified by rapid secondary partitioning and salt formation under seasonally favorable conditions.

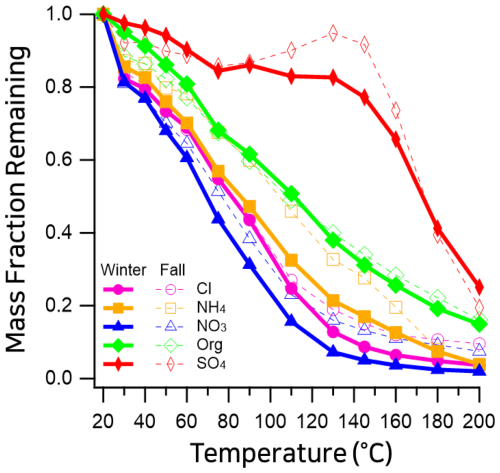

Figure 4Mass fraction remaining (MFR) of non-refractory (NR) aerosol species measured in Seoul using a thermodenuder coupled to a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS). Winter 2019 (this study; dashed) is compared with fall 2019 (previously reported; solid) (Jeon et al., 2023).Species include organics (magenta), nitrate (blue), sulfate (orange), ammonium (green), and chloride (red).

3.2 Volatility of non-refractory species

Figure 4 presents thermograms of non-refractory (NR) species measured by HR-ToF-AMS. The mass fraction remaining (MFR) after thermodenuder (TD) treatment follows the typical volatility trend reported in previous studies (Xu et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2022; Jeon et al., 2023; Huffman et al., 2009): nitrate was the most volatile, followed by chloride, ammonium, organics, and sulfate. Nitrate showed the steepest decline with increasing temperature, with a T50 of ∼67 °C – substantially higher than that of pure ammonium nitrate (∼37 °C; Huffman et al., 2009). At 200 °C, ∼2 % of the initial nitrate signal remained (Fig. 4). Since pure ammonium nitrate fully evaporates well below this temperature (Huffman et al., 2009), this small residual fraction likely represents the least volatile portion of organic nitrates. Compared to previously reported fall conditions (T50 ∼73 °C, incomplete evaporation), winter nitrate appeared more volatile, indicating relatively fewer non-volatile nitrate forms (e.g., Kang et al., 2022; Jeon et al., 2023). Sulfate exhibited the highest thermal stability among the measured species. The thermogram showed a relatively stable mass fraction (MFR >0.8) up to ∼130 °C, followed by a sharp decline at temperatures above 140 °C (Fig. 4). This profile is consistent with the typical volatilization behavior of ammonium sulfate in TD-AMS, which requires higher temperatures to evaporate compared to nitrate or organics (Huffman et al., 2009). At 200 °C, approximately 25 % of the sulfate mass remained. This residual suggests the presence of a sulfate fraction with lower volatility than pure ammonium sulfate, likely associated with organosulfates or low-volatility mixtures, whereas refractory metal sulfates are not efficiently detected by the AMS (Canagaratna et al., 2007). Ammonium showed intermediate volatility, with T50 between nitrate and sulfate. Its slightly lower winter T50 suggests stronger nitrate association. Residual ammonium at 200 °C was consistent (∼4 %) in previously reported spring/fall measurements (Kang et al., 2022; Jeon et al., 2023). Chloride volatility was broadly consistent with prior AMS studies, with T50 values comparable across seasons (e.g., Xu et al., 2016; Jeon et al., 2023). The near-complete evaporation observed in winter (∼4 % residual at 200 °C, Fig. 4) indicates that the chloride measured here was dominated by volatile inorganic chloride, specifically ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), which fully evaporates at relatively low temperatures (Huffman et al., 2009). By contrast, metal chlorides (e.g., NaCl, KCl) are refractory and far less volatile; they are also poorly detected by the AMS (Canagaratna et al., 2007). The lower residual in winter compared to fall (∼10 %) therefore suggests that wintertime chloride consisted almost exclusively of pure ammonium chloride, whereas the fall samples may have contained a minor fraction of less volatile or refractory chloride species. Organics exhibited moderate volatility (T50∼120 °C), and their thermogram showed a gradual, continuous decrease in mass fraction with increasing TD temperature. This smooth profile reflects the presence of a broad distribution of organic compounds spanning SVOC to LVOC ranges, in contrast to inorganic species such as nitrate or ammonium chloride, which often show more abrupt losses at characteristic temperatures (Huffman et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2016). This behavior is consistent with previous TD-AMS observations in Seoul during spring and fall (Kang et al., 2022; Jeon et al., 2023).

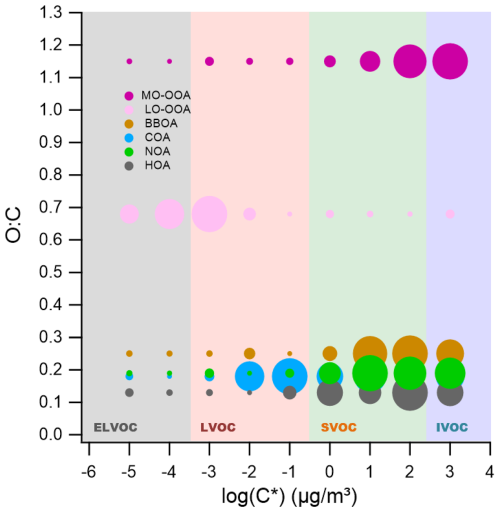

Figure 5Two-dimensional volatility basis set (2D-VBS) representation of organic aerosol (OA) sources identified in winter 2019 in Seoul. The plot illustrates the relationship between the oxygen-to-carbon (O:C) ratio and the effective saturation concentration (C*) for each OA source resolved via positive matrix factorization (PMF). Solid circles represent the volatility distribution across C* bins, with marker size proportional to the mass fraction within each bin for the given source. Shaded regions correspond to different volatility classes: extremely low-volatility organic compounds (ELVOCs), low-volatility organic compounds (LVOCs), semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs), and intermediate-volatility organic compounds (IVOCs), delineated by their C* values.

Volatility profiles of organic sources

Figure 5 presents the volatility distributions of six OA sources within the volatility basis set (VBS) framework. Volatility is expressed as the effective saturation concentration (C*, µg m−3), where higher C* values correspond to higher volatility. Following Donahue et al. (2009), C* values are categorized into four bins: extremely low-volatility organic compounds (ELVOCs, log ), low-volatility organic compounds (LVOCs, ), semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs, ), and intermediate-volatility organic compounds (IVOCs, ).

Among the primary OA (POA) sources, hydrocarbon-like OA (HOA) exhibited the highest volatility, with mass predominantly distributed in the SVOC and IVOC ranges, consistent with its chemically reduced nature () and direct combustion origin. Mass fraction remaining (MFR) results (Fig. S9) further support this, showing rapid mass loss at lower temperatures. Biomass burning OA (BBOA) and nitrogen-containing OA (NOA) also showed high volatility, peaking in the SVOC–IVOC range (–3), but displayed slightly higher O:C ratios (0.25 and 0.19, respectively). This modest enhancement in O:C reflects their source composition – biomass combustion produces partially oxygenated organic species (e.g., levoglucosan, phenols), and NOA contains nitrogen-bearing functional groups – rather than enhanced atmospheric oxidation. Cooking-related OA (COA) showed a more moderate volatility profile, with mass more evenly distributed across the LVOC and SVOC bins. This behavior differs from that of BBOA, which is slightly more oxidized yet more volatile. This apparent decoupling between oxidation state and volatility is a characteristic feature of COA reported in previous volatility studies (Paciga et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2022). These studies attribute the lower volatility of COA to its abundance of high-molecular-weight fatty acids (e.g., oleic, palmitic, and stearic acids) and glycerides (Mohr et al., 2009; He et al., 2010). Unlike the smaller, fragmented molecules typical of biomass burning, these lipid-like compounds possess high molar masses that suppress volatility, even though their long alkyl chains result in low O:C ratios.

For secondary OA (SOA), less-oxidized oxygenated OA (LO-OOA) exhibited the lowest volatility, with substantial mass in the LVOC and ELVOC bins (–10−4). This is in agreement with previous findings in Seoul during spring (Kang et al., 2022). In contrast, more-oxidized OOA (MO-OOA), despite its higher oxidation state (), displayed greater volatility, with a peak at . This discrepancy likely reflects differences in formation and aging processes, as discussed further in Sect. 3.3.

Overall, the volatility characteristics across OA factors suggest that oxidation state alone does not fully explain volatility. Rather, volatility is shaped by a combination of emission source, emission timing, temperature, and atmospheric processing. These findings highlight the importance of integrating both chemical and physical characterization to better understand OA formation and aging across seasons.

3.3 Aging effect on volatility from 2D VBS

Generally, the oxygen-to-carbon (O:C) ratio of organic aerosols (OA) is inversely related to their volatility. As O:C increases through aging, the effective saturation concentration (C*) typically decreases, resulting in lower volatility (Donahue et al., 2006; Jimenez et al., 2009). This relationship arises because oxidative functionalization introduces polar groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl) that increase molecular weight and enhance intermolecular hydrogen bonding, thereby reducing the effective saturation concentration (C*) and promoting particle-phase retention (Jimenez et al., 2009; Kroll and Seinfeld, 2008; Donahue et al., 2011). However, in this study, the most oxidized OA factor – MO-OOA, with a high O:C ratio of 1.15 – exhibited unexpectedly high volatility. Its volatility distribution was skewed toward SVOCs and IVOCs (Fig. 5), and its rapid mass loss in MFR thermograms (Fig. S9) further indicated low thermal stability. This observation appears to contradict the usual inverse O:C–volatility relationship; however, under winter haze conditions – with suppressed O3/low OH, particle-phase autoxidation and fragmentation can yield higher-O:C yet more volatile products, with enhanced condensation on abundant particle surface area (details below).

Viewed against prior TD-AMS results, the volatility of Seoul's winter MO-OOA presents a unique case, particularly in the nature of its O:C-volatility relationship. Prior urban studies have commonly reported substantial SVOC-OA, consistent with high photochemical activity or elevated loadings; for example, prior TD-AMS studies in Mexico City, Los Angeles, Beijing, and Shenzhen have all reported substantial SVOC–IVOC contributions during polluted periods, indicating that high OA volatility is a common feature of urban environments across seasons (Cappa and Jimenez, 2010; Xu et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2018). While these comparisons establish that volatile OA is common, they generally did not report the factor-level inversion observed here, where the highly-oxidized OOA component (MO-OOA) was more volatile than a less-oxidized OOA (LO-OOA). This behavior is distinct from findings in colder, lower-loading regimes; wintertime Paris, for instance, maintained the conventional hierarchy where the more-oxidized OOA was comparatively less volatile (Paciga et al., 2016). Furthermore, seasonal context within Seoul showed springtime OA with lower oxidation levels than our winter MO-OOA despite similar SVOC contributions (Kang et al., 2022). This comprehensive comparison underscores the unusual nature of the O:C-volatility relationship observed under the specific winter haze conditions in Seoul.

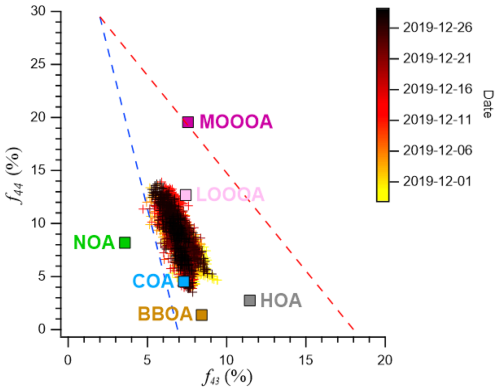

Figure 6Scatterplot of f44 (CO) versus f43 (C2H3O+). for the measured organic aerosol. The data points are color-coded by date to illustrate the temporal variation in OA composition throughout the observation period. The separated OA factors (HOA, COA, BBOA, NOA, LO-OOA, and MO-OOA) are also shown to enable comparison of source contributions and oxidation characteristics. The dashed line represents the typical f60 threshold associated with biomass-burning influence, while the triangular boundary indicates the conventional oxidative aging trend in the f44–f60 space.

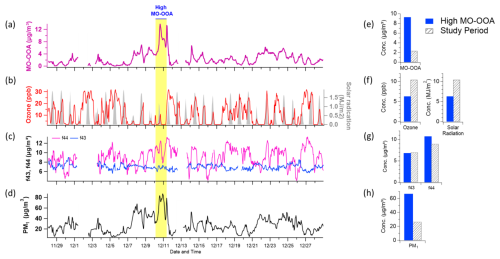

Figure 7Time series plots of (a) MO-OOA concentration, (b) ozone (O3) and solar radiation, (c) f44 and f43 (indicative of oxidation state), and (d) total PM1 concentration. The period characterized by elevated MO-OOA levels is highlighted in bright yellow. Panels (e)–(f) present comparative distributions of these variables – MO-OOA, O3 and solar radiation, f44 and f43, and PM1 – between the high MO-OOA period (shaded in blue) and the entire measurement period (indicated by gray hatching).

High-volatility nature of MO-OOA in Seoul wintertime

MO-OOA exhibited high O:C ratios and high apparent volatility, characteristics that were further amplified during haze episodes – periods marked by reduced ozone levels, low solar radiation, and elevated aerosol mass concentrations (Figs. 7 and S6, yellow shading). Spectrally, MO-OOA was defined by a consistently high f44 (CO) signal and a comparatively stable f43 (C2H3O+) signal relative to LO-OOA (Fig. 6). Notably, when MO-OOA concentrations intensified during haze, only f44 was significantly enhanced, while f43 remained nearly unchanged (Fig. 6). This trend is corroborated by the haze–non-haze comparison (Fig. S12), where haze periods (including high MO-OOA intervals) showed elevated contributions from oxygenated fragments ( 28, 29, 44) and higher O:C ratios. In contrast, non-haze periods were characterized by larger fractional contributions from hydrocarbon-like fragments ( 41, 43, 55, 57). The observed temporal pattern – elevated f44 without corresponding changes in f43 – is a typical signature of highly oxidized and fragmented organic aerosol (Figs. 6 and 7), suggesting that aging was dominated by fragmentation rather than functionalization (Kroll et al., 2009). These spectral patterns collectively indicate that MO-OOA is highly oxidized yet remains relatively volatile compared to LO-OOA.

The elevated volatility of MO-OOA despite its high O:C (∼1.15) indicates that oxidation under these haze conditions did not follow the classical multi-generational OH-driven aging pathway, which typically increases molecular mass and reduces volatility. Instead, the data align with fragmentation-dominated aging, where highly oxygenated but lower-molecular-weight compounds (e.g., small acids or diacids) are formed. Prior field and laboratory studies using online AMS/FIGAERO-CIMS and EESI-TOF have similarly reported high-O:C yet volatile product distributions characterized by high f44 and stable f43 (Kroll et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2010; Chhabra et al., 2011; Lambe et al., 2012; López-Hilfiker et al., 2016; D'Ambro et al., 2017).

While direct mechanistic measurements were not available in this study, we hypothesize that the formation of this volatile, high-O:C component may be driven by specific low-light oxidation pathways consistent with the observed environmental conditions. The suppressed ozone levels during haze likely indicate a low-OH oxidation regime (Fig. 7). Under such conditions, radical chemistry involving NO3 (which is longer-lived in low light) or particle-phase autoxidation could preferentially produce highly oxygenated but relatively small organic fragments (Ehn et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2023). Although haze suppresses photolysis, HONO concentrations – maintained via heterogeneous conversion or surface emissions – could still provide a non-negligible source of OH (Gil et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2024; Slater et al., 2020). Furthermore, the high aerosol mass loadings during haze (Coa) provide abundant surface area for absorptive partitioning (Pankow, 1994; Donahue et al., 2006). This increased partitioning mass allows even relatively volatile, oxidized compounds to condense into the particle phase, contributing to the high apparent volatility and oxidation state observed (Jimenez et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2017). Consequently, these results underscore the need for SOA models to incorporate fragmentation-dominated pathways to accurately represent wintertime haze evolution.

This study provides a comprehensive characterization of wintertime submicron aerosols (PM1) in Seoul, integrating chemical composition, volatility measurements, and source apportionment to reveal critical insights into urban OA evolution. The two most significant findings are the robust real-time identification of a nitrogen-containing organic aerosol (NOA) factor and the observation of unexpected volatility behavior in highly oxidized OA. The NOA factor, spectrally dominated by low-molecular-weight alkylamine fragments, was successfully resolved primarily due to the accumulation of pollutants during wintertime stagnation, which sufficiently enhanced the spectral signals of these semi-volatile species for identification. Its temporal and chemical characteristics point to a mixed primary/secondary origin: driven by direct combustion emissions (e.g., residential heating) but significantly enhanced by the rapid gas-to-particle partitioning of semi-volatile amines under cold, humid conditions. Concurrently, the volatility analysis revealed a notable decoupling between oxidation state and volatility for the More-Oxidized Oxygenated OA (MO-OOA). Despite its high O:C ratio (∼1.15), MO-OOA exhibited elevated volatility, a deviation from classical aging models that typically associate high oxidation with low volatility. This behavior is attributed to the specific conditions of winter haze – reduced photolysis and high aerosol mass loadings – which favor fragmentation-dominated aging pathways and the absorptive partitioning of volatile oxygenated products.

These results revise our understanding of wintertime aerosol dynamics and underscore the limitations of current models in representing reduced-nitrogen species and non-canonical oxidation pathways. To address the remaining uncertainties, future research should prioritize evaluating the seasonal variability of NOA to better disentangle the influence of meteorological drivers from specific emission sources. Concurrently, there is a critical need to directly probe radical oxidation mechanisms, such as RO2 autoxidation and NO3 chemistry, particularly under haze conditions. Integrating these field inquiries with laboratory studies and advanced molecular-level measurements (e.g., FIGAERO-CIMS, EESI-TOF) will be essential for constraining the formation, lifetime, and climate impacts of these complex organic aerosol components in polluted megacities.

Data presented in this article are available upon request to the corresponding author.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-1145-2026-supplement.

HK designed the study and prepared the manuscript. JJ operated the TD-AMS and analyzed the TD-AMS data. JM curated and managed the dataset. HGK conducted the volatility analysis of organic aerosol (OA).

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-00514570), the project “development of SMaRT based aerosol measurement and analysis systems for the evaluation of climate change and health risk assessment” operated by Seoul National University (900-20240101). Also this research was supported by Particulate Matter Management Specialized Graduate Program through the Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) funded by the Ministry of Environment (MOE).

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MSIT) (grant no. RS-2025-00514570), and by a project operated by Seoul National University (project no. 900-20240101).

This paper was edited by Theodora Nah and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Allan, J. D., Williams, P. I., Morgan, W. T., Martin, C. L., Flynn, M. J., Lee, J., Nemitz, E., Phillips, G. J., Gallagher, M. W., and Coe, H.: Contributions from transport, solid fuel burning and cooking to primary organic aerosols in two UK cities, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 647–668, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-647-2010, 2010.

Baek, K. M., Park, E. H., Kang, H., Ji, M. J., Park, H. M., Heo, J., and Kim, H.: Seasonal characteristics of atmospheric water-soluble organic nitrogen in PM2.5 in Seoul, Korea: Source and atmospheric processes of free amino acids and aliphatic amines, Sci. Total Environ., 807, 150785, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152335, 2022.

Canagaratna, M. R., Jayne, J. T., Ghertner, D. A., Herndon, S. C., Shi, Q., Jimenez, J. L.,Silva, P. J., Williams, P., Lanni, T., Drewnick, F., Demerjian, K. L., Kolb, C. E., andWorsnop, D. R.: Chase studies of particulate emissions from in-use New York City vehicles, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 38, 555–573, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820490465504, 2004.

Canagaratna, M. R., Jayne, J. T., Jimenez, J. L., Allan, J. D., Alfarra, M. R., Zhang, Q., Onasch, T. B., Drewnick, F., Coe, H., Middlebrook, A., Delia, A., Williams, L. R., Trimborn, A. M., Northway, M. J., DeCarlo, P. F., Kolb, C. E., Davidovits, P., and Worsnop, D. R.: Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the Aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer, Mass Spectrom. Rev., 26, 185–222, https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.20115, 2007.

Canagaratna, M. R., Jimenez, J. L., Kroll, J. H., Chen, Q., Kessler, S. H., Massoli, P., Hildebrandt Ruiz, L., Fortner, E., Williams, L. R., Wilson, K. R., Surratt, J. D., Donahue, N. M., Jayne, J. T., and Worsnop, D. R.: Elemental ratio measurements of organic compounds using aerosol mass spectrometry: characterization, improved calibration, and implications, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 253–272, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-253-2015, 2015.

Cao, L.-M., Huang, X.-F., Li, Y.-Y., Hu, M., and He, L.-Y.: Volatility measurement of atmospheric submicron aerosols in an urban atmosphere in southern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 1729–1743, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-1729-2018, 2018.

Cappa, C. D. and Jimenez, J. L.: Quantitative estimates of the volatility of ambient organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 5409–5424, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-5409-2010, 2010.

Chen, W., Ye, Y., Hu, W., Zhou, H., Pan, T., Wang, Y., Song, W., Song, Q., Ye, C., Wang, C., Wang, B., Huang, S., Yuan, B., Zhu, M., Lian, X., Zhang, G., Bi, X., Jiang, F., Liu, J., Canonaco, F., Prevot, A. S. H., Shao, M., and Wang, X.: Real-time characterization of aerosol compositions, sources, and aging processes in Guangzhou during PRIDE-GBA 2018 campaign, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2021JD035114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035114, 2021.

Chhabra, P. S., Ng, N. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Corrigan, A. L., Russell, L. M., Worsnop, D. R., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Elemental composition and oxidation of chamber organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 8827–8845, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-8827-2011, 2011.

Cubison, M. J., Ortega, A. M., Hayes, P. L., Farmer, D. K., Day, D., Lechner, M. J., Brune, W. H., Apel, E., Diskin, G. S., Fisher, J. A., Fuelberg, H. E., Hecobian, A., Knapp, D. J., Mikoviny, T., Riemer, D., Sachse, G. W., Sessions, W., Weber, R. J., Weinheimer, A. J., Wisthaler, A., and Jimenez, J. L.: Effects of aging on organic aerosol from open biomass burning smoke in aircraft and laboratory studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 12049–12064, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-12049-2011, 2011.

D'Ambro, E. L., Lee, B. H., Liu, J., Shilling, J. E., Gaston, C. J., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Schobesberger, S., Zaveri, R. A., Mohr, C., Lutz, A., Zhang, Z., Gold, A., Surratt, J. D., Rivera-Rios, J. C., Keutsch, F. N., and Thornton, J. A.: Molecular composition and volatility of isoprene photochemical oxidation secondary organic aerosol under low- and high-NOx conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 159–174, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-159-2017, 2017.

DeCarlo, P. F., Kimmel, J. R., Trimborn, A., Northway, M. J., Jayne, J. T., Aiken, A. C., Gonin, M., Fuhrer, K., Horvath, T., Docherty, K. S., Worsnop, D. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Field-deployable, high-resolution, time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer, Anal. Chem., 78, 8281–8289, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac061249n, 2006.

Donahue, N. M., Robinson, A. L., Stanier, C. O., and Pandis, S. N.: Coupled partitioning, dilution, and chemical aging of semivolatile organics, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 2635–2643, https://doi.org/10.1021/es052297c, 2006.

Donahue, N. M., Robinson, A. L., and Pandis, S. N.: Atmospheric organic particulate matter: From smoke to secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Environ., 43, 94–106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.055, 2009.

Donahue, N. M., Epstein, S. A., Pandis, S. N., and Robinson, A. L.: A two-dimensional volatility basis set: 1. organic-aerosol mixing thermodynamics, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 3303–3318, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-3303-2011, 2011.

Ehn, M., Thornton, J. A., Kleist, E., Sipilä, M., Junninen, H., Pullinen, I., Springer, M., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Schreiber, B., Wendisch, M., Wahner, A., Mentel, T. F., Worsnop, D. R., and Kulmala, M.: A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol, Nature, 506, 476–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13032, 2014.

EPA: EPA Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0 Fundamentals and User Guide, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-14/108, 2014.

Faulhaber, A. E., Thomas, B. M., Jimenez, J. L., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., and Ziemann, P. J.: Characterization of a thermodenuder-particle beam mass spectrometer system for the study of organic aerosol volatility and composition, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 2, 15–31, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2-15-2009, 2009.

Ge, X., Wexler, A. S., and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric amines – Part I. A review, Atmos. Environ., 45, 524–546, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.10.012, 2011a.

Ge, X., Wexler, A. S., and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric amines – Part II: Thermodynamic properties and gas/particle partitioning, Atmos. Environ., 45, 561–577, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.10.013, 2011b.

Ge, X., Wexler, A. S., and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric amines – Part III: Photochemistry and toxicity, Atmos. Environ., 45, 561–591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.050, 2011c.

Ghim, Y. S., Moon, K.-C., Lee, S., and Kim, Y. P.: Visibility trends in Korea during the past two decades, J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc., 55, 73–82, https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2005.10464599, 2005.

Gil, J., Lee, Y., and Kim, Y. P.: Characteristics of HONO and its impact on O3 formation in the Seoul Metropolitan Area during KORUS-AQ, Atmos. Environ., 246, 118032, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.118182, 2021.

Glasius, M. and Goldstein, A. H.: Recent discoveries and future challenges in atmospheric organic chemistry, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 2754–2764, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05105, 2016.

Grieshop, A. P., Logue, J. M., Donahue, N. M., and Robinson, A. L.: Laboratory investigation of photochemical oxidation of organic aerosol from wood fires 1: measurement and simulation of organic aerosol evolution, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 1263–1277, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1263-2009, 2009.

Hallquist, M., Wenger, J. C., Baltensperger, U., Rudich, Y., Simpson, D., Claeys, M., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., George, C., Goldstein, A. H., Hamilton, J. F., Herrmann, H., Hoffmann, T., Iinuma, Y., Jang, M., Jenkin, M. E., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Maenhaut, W., McFiggans, G., Mentel, Th. F., Monod, A., Prévôt, A. S. H., Seinfeld, J. H., Surratt, J. D., Szmigielski, R., and Wildt, J.: The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 5155–5236, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-5155-2009, 2009.

Hamanaka, R. B. and Mutlu, G. M.: Particulate matter air pollution: Effects on the cardiovascular system, Front. Endocrinol., 9, 680, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00680, 2018.

Han, K.-M., Kim, D.-G., Kim, J., Lee, S., Song, C.-H., Kim, P. S., Kim, J., Lim, H., and Kim, Y.: Crop residue burning emissions and impact on particulate matter over South Korea, Atmosphere, 13, 559, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13040559, 2022.

Hayes, P. L., Ortega, A. M., Cubison, M. J., Froyd, K. D., Zhao, Y., Cliff, S. S., Hu, W. W., Toohey, D. W., Flynn, J. H., Lefer, B. L., Grossberg, N., Alvarez, S., Rappenglück, B., Taylor, J. W., Allan, J. D., Holloway, J. S., Gilman, J. B., Kuster, W. C., de Gouw, J. A., Massoli, P., Zhang, X., Canagaratna, M. R., Zotter, P., Prévôt, A. S. H., Washenfelder, R. A., Young, D. J., Kriner, A. J., and Jimenez, J. L.: Organic aerosol composition and sources in Pasadena, California, during the 2010 CalNex campaign, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 9233–9257, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50530, 2013.

He, L.-Y., Lin, Y., Huang, X.-F., Guo, S., Xue, L., Su, Q., Hu, M., Luan, S.-J., and Zhang, Y.-H.: Characterization of high-resolution aerosol mass spectra of primary organic aerosol emissions from Chinese cooking and biomass burning, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 11535–11543, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-11535-2010, 2010.

Hennigan, C. J., Sullivan, A. P., Collett Jr., J. L., and Robinson, A. L.: Levoglucosan stability in biomass burning particles exposed to hydroxyl radicals, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L09806, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043088, 2010.

Huang, X.-F., He, L.-Y., Hu, M., Canagaratna, M. R., Sun, Y., Zhang, Q., Zhu, T., Xue, L., Zeng, L.-W., Liu, X.-G., Zhang, Y.-H., Jayne, J. T., Ng, N. L., and Worsnop, D. R.: Highly time-resolved chemical characterization of atmospheric submicron particles during 2008 Beijing Olympic Games using an Aerodyne High-Resolution Aerosol Mass Spectrometer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 8933–8945, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-8933-2010, 2010.

Huffman, J. A., Ziemann, P. J., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Development and characterization of a fast-stepping thermodenuder for chemically resolved aerosol volatility measurements, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 42, 395–407, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820802104981, 2008.

Huffman, J. A., Docherty, K. S., Aiken, A. C., Cubison, M. J., Ulbrich, I. M., DeCarlo, P. F., Sueper, D., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., Ziemann, P. J., and Jimenez, J. L.: Chemically-resolved aerosol volatility measurements from two megacity field studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 7161–7182, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-7161-2009, 2009.

IPCC: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 817–922, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.008, 2021.

Jeon, J., Chen, Y., and Kim, H.: Influence of meteorology on emission sources and physicochemical properties of particulate matter in Seoul, Korea during heating period, Atmos. Environ., 301, 119733, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119733, 2023.

Jiang, F., Liu, Q., Huang, X., Wang, T., Zhuang, B., and Xie, M.: Regional modelling of secondary organic aerosol over China using WRF/Chem, J. Aerosol Sci., 53, 50–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2011.09.003, 2012.

Jimenez, J. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Donahue, N. M., Prevot, A. S. H., Zhang, Q., Kroll, J. H., DeCarlo, P. F., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Ng, N. L., Aiken, A. C., Docherty, K. S., Ulbrich, I. M., Grieshop, A. P., Robinson, A. L., Duplissy, J., Smith, J. D., Wilson, K. R., Lanz, V. A., Hueglin, C., Sun, Y. L., Tian, J., Laaksonen, A., Raatikainen, T., Rautiainen, J., Vaattovaara, P., Ehn, M., Kulmala, M., Tomlinson, J. M., Collins, D. R., Cubison, M. J., Dunlea, E. J., Huffman, J. A., Onasch, T. B., Alfarra, M. R., Williams, P. I., Bower, K., Kondo, Y., Schneider, J., Drewnick, F., Borrmann, S., Weimer, S., Demerjian, K., Salcedo, D., Cottrell, L., Griffin, R. J., Rautianen, J., and Worsnop, D. R.: Evolution of organic aerosols in the atmosphere, Science, 326, 1525–1529, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180353, 2009.

Kang, H. G., Kim, Y., Collier, S., Zhang, Q., and Kim, H.: Volatility of springtime ambient organic aerosol derived with thermodenuder aerosol mass spectrometry in Seoul, Korea, Environ. Pollut., 310, 119203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119203, 2022.

Karnezi, E., Riipinen, I., and Pandis, S. N.: Measuring the atmospheric organic aerosol volatility distribution: a theoretical analysis, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 2953–2965, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-2953-2014, 2014.

Kim, H., Zhang, Q., Bae, G.-N., Kim, J. Y., and Lee, S. B.: Sources and atmospheric processing of winter aerosols in Seoul, Korea: insights from real-time measurements using a high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 2009–2033, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-2009-2017, 2017.

Kim, H., Zhang, Q., and Sun, Y.: Measurement report: Characterization of severe spring haze episodes and influences of long-range transport in the Seoul metropolitan area in March 2019, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 11527–11550, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-11527-2020, 2020.

Kim, K., Han, K. M., Song, C. H., Lee, H., Beardsley, R., Yu, J., Yarwood, G., Koo, B., Madalipay, J., Woo, J.-H., and Cho, S.: An investigation into atmospheric nitrous acid (HONO) processes in South Korea, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 12575–12593, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-12575-2024, 2024.

Kroll, J. H. and Seinfeld, J. H.: Chemistry of secondary organic aerosol: Formation and evolution of low-volatility organics in the atmosphere, Atmos. Environ., 42, 3593–3624, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.01.003, 2008.

Kroll, J. H., Smith, J. D., Che, D. L., Kessler, S. H., Worsnop, D. R., and Wilson, K. R.: Measurement of fragmentation and functionalization pathways in the heterogeneous oxidation of oxidized organic aerosol, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 11, 8005–8014, https://doi.org/10.1039/b905289e, 2009.

Kwon, S., Won, S. R., Lim, H. B., Jang, K. S., and Kim, H.: Relationship between PM1.0 and PM2.5 in urban and background areas of the Republic of Korea, Atmos. Pollut. Res., 14, 101858, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2023.101858, 2023.

Lamb, K. D., Kim, B.-G., and Kim, S.-W.: Estimating source-region influences on black carbon in South Korea using the ratio, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 123, 11579–11591, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD029257, 2018.

Lambe, A. T., Onasch, T. B., Massoli, P., Croasdale, D. R., Wright, J. P., Ahern, A. T., Williams, L. R., Worsnop, D. R., and Davidovits, P.: Transitions from Functionalization to Fragmentation Reactions of Laboratory Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) Generated from the OH Oxidation of Alkane Precursors, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 5430–5437, https://doi.org/10.1021/es300274t, 2012.

Li, J., Zhang, M., Wu, F., Sun, Y., and Tang, G.: Assessment of the impacts of aromatic VOC emissions and yields of SOA on SOA concentrations with the air quality model RAMS-CMAQ, Atmos. Environ., 158, 105–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.03.035, 2017.

Liu, T., Xu, Y., Sun, Q.-B., Xiao, H.-W., Zhu, R.-G., Li, C.-X., Li, Z.-Y., Zhang, K.-Q., Sun, C.-X., and Xiao, H.-Y.: Characteristics, origins, and atmospheric processes of amines in fine aerosol particles in winter in China, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 128, e2023JD038974, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JD038974, 2023.

López-Hilfiker, F. D., Mohr, C., Ehn, M., Voigtländer, J., Abrahamsson, K., Hallquist, M., Bertman, S. B., Kjærgaard, H. G., and Thornton, J. A.: Molecular composition and volatility of organic aerosol in the Southeastern U.S. using FIGAERO–CIMS with comparison to AMS, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 2200–2209, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b04769, 2016.

Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Starvropoulos, A., and Bezirtzoglou, E.: Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: a review, Front. Public Health, 8, 14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014, 2020.

Mao, J., Yu, F., Zhang, Y., An, J., Wang, L., Zheng, J., Yao, L., Luo, G., Ma, W., Yu, Q., Huang, C., Li, L., and Chen, L.: High-resolution modeling of gaseous methylamines over a polluted region in China: source-dependent emissions and implications of spatial variations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7933–7950, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7933-2018, 2018.

Middlebrook, A. M., Bahreini, R., Jimenez, J. L., and Canagaratna, M. R.: Evaluation of Composition-Dependent Collection Efficiencies for the Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer using Field Data, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 46, 258–271, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2011.620041, 2012.

Mohr, C., Huffman, J. A., Cubison, M. J., Aiken, A. C., Docherty, K. S., Kimmel, J. R., Ulbrich, I. M., Hannigan, M., and Jimenez, J. L.: Characterization of primary organic aerosol emissions from meat cooking, trash burning, and motor vehicles with high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry and comparison with ambient and chamber observations, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 2443–2449, https://doi.org/10.1021/es8011518, 2009.

Mohr, C., DeCarlo, P. F., Heringa, M. F., Chirico, R., Slowik, J. G., Richter, R., Reche, C., Alastuey, A., Querol, X., Seco, R., Peñuelas, J., Jiménez, J. L., Crippa, M., Zimmermann, R., Baltensperger, U., and Prévôt, A. S. H.: Identification and quantification of organic aerosol from cooking and other sources in Barcelona using aerosol mass spectrometer data, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 1649–1665, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-1649-2012, 2012.

Nault, B. A., Campuzano-Jost, P., Day, D. A., Schroder, J. C., Anderson, B., Beyersdorf, A. J., Blake, D. R., Brune, W. H., Choi, Y., Corr, C. A., de Gouw, J. A., Dibb, J., DiGangi, J. P., Diskin, G. S., Fried, A., Huey, L. G., Kim, M. J., Knote, C. J., Lamb, K. D., Lee, T., Park, T., Pusede, S. E., Scheuer, E., Thornhill, K. L., Woo, J.-H., and Jimenez, J. L.: Secondary organic aerosol production from local emissions dominates the organic aerosol budget over Seoul, South Korea, during KORUS-AQ, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 17769–17800, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-17769-2018, 2018.

Ng, N. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Zhang, Q., Jimenez, J. L., Tian, J., Ulbrich, I. M., Kroll, J. H., Docherty, K. S., Chhabra, P. S., Bahreini, R., Murphy, S. M., Seinfeld, J. H., Hildebrandt, L., Donahue, N. M., DeCarlo, P. F., Lanz, V. A., Prévôt, A. S. H., Dinar, E., Rudich, Y., and Worsnop, D. R.: Organic aerosol components observed in Northern Hemispheric datasets from Aerosol Mass Spectrometry, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 4625–4641, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-4625-2010, 2010.

Ng, N. L., Brown, S. S., Archibald, A. T., Atlas, E., Cohen, R. C., Crowley, J. N., Day, D. A., Donahue, N. M., Fry, J. L., Fuchs, H., Griffin, R. J., Guzman, M. I., Herrmann, H., Hodzic, A., Iinuma, Y., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Lee, B. H., Luecken, D. J., Mao, J., McLaren, R., Mutzel, A., Osthoff, H. D., Ouyang, B., Picquet-Varrault, B., Platt, U., Pye, H. O. T., Rudich, Y., Schwantes, R. H., Shiraiwa, M., Stutz, J., Thornton, J. A., Tilgner, A., Williams, B. J., and Zaveri, R. A.: Nitrate radicals and biogenic volatile organic compounds: oxidation, mechanisms, and organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 2103–2162, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-2103-2017, 2017.

Nielsen, C. J., Herrmann, H., and Weller, C.: Atmospheric chemistry and environmental impact of the use of amines in carbon capture and storage (CCS), Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6684–6704, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CS35059A, 2012.

Paatero, P. and Tapper, U.: Positive matrix factorization – A nonnegative factor model with optimal utilization of error estimates of data values, Environmetrics, 5, 111–126, https://doi.org/10.1002/env.3170050203, 1994.

Paciga, A., Karnezi, E., Kostenidou, E., Hildebrandt, L., Psichoudaki, M., Engelhart, G. J., Lee, B.-H., Crippa, M., Prévôt, A. S. H., Baltensperger, U., and Pandis, S. N.: Volatility of organic aerosol and its components in the megacity of Paris, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 2013–2023, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-2013-2016, 2016.

Pankow, J. F.: An absorption model of gas/particle partitioning of organic compounds in the atmosphere, Atmos. Environ., 28, 185–188, 1994.

Riipinen, I., Pierce, J. R., Donahue, N. M., and Pandis, S. N.: Equilibration time scales of organic aerosol inside thermodenuders: Kinetics versus equilibrium thermodynamics, Atmos. Environ., 44, 597–607, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.11.022, 2010.

Robinson, A. L., Donahue, N. M., Shrivastava, M. K., Weitkamp, E. A., Sage, A. M., Grieshop, A. P., Lane, T. E., Pierce, J. R., and Pandis, S. N.: Rethinking organic aerosols: Semivolatile emissions and photochemical aging, Science, 315, 1259–1262, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1133061, 2007.

Rovelli, G., Miles, R. E. H., Reid, J. P., and Clegg, S. L.: Hygroscopic properties of aminium sulfate aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 4369–4385, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-4369-2017, 2017.

Saarikoski, S., Carbone, S., Decesari, S., Giulianelli, L., Angelini, F., Canagaratna, M., Ng, N. L., Trimborn, A., Facchini, M. C., Fuzzi, S., Hillamo, R., and Worsnop, D.: Chemical characterization of springtime submicrometer aerosol in Po Valley, Italy, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 8401–8421, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-8401-2012, 2012.

Saha, P. K., Khlystov, A., and Grieshop, A. P.: Determining aerosol volatility parameters using a “dual thermodenuder” system: Application to laboratory-generated organic aerosols, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 49, 620–632, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2015.1056769, 2014.

Shen, W., Ren, L., Zhao, Y., Zhou, L., Dai, L., Ge, X., Kong, S., Yan, Q., Xu, H., Jiang, Y., He, J., Chen, M., and Yu, H.: C1–C2 alkyl aminiums in urban aerosols: Insights from ambient and fuel combustion emission measurements in the Yangtze River Delta region of China, Environ. Pollut., 230, 12–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.034, 2017.

Silva, P. J., Erupe, M. E., Price, D., Elias, J., Malloy, Q. G. J., Li, Q., Warren, B., and Cocker III, D. R.: Trimethylamine as precursor to secondary organic aerosol formation via nitrate radical reaction in the atmosphere, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 4689–4696, https://doi.org/10.1021/es703016v, 2008.

Simoneit, B. R. T.: Biomass burning – a review of organic tracers for smoke from incomplete combustion, Appl. Geochem., 17, 129–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-2927(01)00061-0, 2002.

Sinha, A., George, I., Holder, A., Preston, W., Hays, M., and Grieshop, A. P.: Development of volatility distributions for organic matter in biomass burning emissions, Environ. Sci. Adv., 3, 11–23, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EA00080F, 2023.

Slater, E. J., Whalley, L. K., Woodward-Massey, R., Ye, C., Lee, J. D., Squires, F., Hopkins, J. R., Dunmore, R. E., Shaw, M., Hamilton, J. F., Lewis, A. C., Crilley, L. R., Kramer, L., Bloss, W., Vu, T., Sun, Y., Xu, W., Yue, S., Ren, L., Acton, W. J. F., Hewitt, C. N., Wang, X., Fu, P., and Heard, D. E.: Elevated levels of OH observed in haze events during wintertime in central Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 14847–14871, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-14847-2020, 2020.

Soleimani, M., Ebrahimi, Z., Mirghaffari, N., and Naseri, M.: Source identification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with fine particulate matters (PM2.5) in Isfahan City, Iran, using diagnostic ratio and PMF model, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 29, 30310–30326, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17635-8, 2022.

Srivastava, D., Vu, T. V., Tong, S., Shi, Z., and Harrison, R. M.: Formation of secondary organic aerosols from anthropogenic precursors in laboratory studies, npj Clim. Atmos. Sci., 5, 22, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00238-6, 2022.

Sun, Y.-L., Zhang, Q., Schwab, J. J., Demerjian, K. L., Chen, W.-N., Bae, M.-S., Hung, H.-M., Hogrefe, O., Frank, B., Rattigan, O. V., and Lin, Y.-C.: Characterization of the sources and processes of organic and inorganic aerosols in New York city with a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass apectrometer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 1581–1602, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-1581-2011, 2011.

Tiszenkel, L., Flynn, J. H., and Lee, S.-H.: Measurement report: Urban ammonia and amines in Houston, Texas, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 11351–11363, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-11351-2024, 2024.

Ulbrich, I. M., Canagaratna, M. R., Zhang, Q., Worsnop, D. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Interpretation of organic components from Positive Matrix Factorization of aerosol mass spectrometric data, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2891–2918, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2891-2009, 2009.

Waked, A., Favez, O., Alleman, L. Y., Piot, C., Petit, J.-E., Delaunay, T., Verlinden, E., Golly, B., Besombes, J.-L., Jaffrezo, J.-L., and Leoz-Garziandia, E.: Source apportionment of PM10 in a north-western Europe regional urban background site (Lens, France) using positive matrix factorization and including primary biogenic emissions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 3325–3346, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-3325-2014, 2014.

Xu, L., Kollman, M. S., Song, C., Shilling, J. E., and Ng, N. L.: Effects of NOx on the volatility of secondary organic aerosol from isoprene photooxidation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 2253–2262, https://doi.org/10.1021/es404842g, 2014.

Xu, L., Williams, L. R., Young, D. E., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Massoli, P., Fortner, E., Chhabra, P., Herndon, S., Brooks, W. A., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., Aiken, A. C., Liu, S., Gorkowski, K., Dubey, M. K., Fleming, Z. L., Visser, S., Prévôt, A. S. H., and Ng, N. L.: Wintertime aerosol chemical composition, volatility, and spatial variability in the greater London area, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 1139–1160, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-1139-2016, 2016.

Xu, W., Sun, Y., Wang, Q., Chen, C., Chen, J., Ge, X., Zhang, Q., Ji, D., Du, W., Zhao, J., Zhou, W., and Worsnop, D. R.: Seasonal characterization of organic nitrogen in atmospheric aerosols using high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry in Beijing, China, ACS Earth Space Chem., 1, 649–658, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00106, 2017.

Xu, W., Xie, C., Karnezi, E., Zhang, Q., Wang, J., Pandis, S. N., Ge, X., Zhang, J., An, J., Wang, Q., Zhao, J., Du, W., Qiu, Y., Zhou, W., He, Y., Li, Y., Li, J., Fu, P., Wang, Z., Worsnop, D. R., and Sun, Y.: Summertime aerosol volatility measurements in Beijing, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 10205–10216, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-10205-2019, 2019.

You, Y., Kanawade, V. P., de Gouw, J. A., Guenther, A. B., Madronich, S., Sierra-Hernández, M. R., Lawler, M., Smith, J. N., Takahama, S., Ruggeri, G., Koss, A., Olson, K., Baumann, K., Weber, R. J., Nenes, A., Guo, H., Edgerton, E. S., Porcelli, L., Brune, W. H., Goldstein, A. H., and Lee, S.-H.: Atmospheric amines and ammonia measured with a chemical ionization mass spectrometer (CIMS), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 12181–12194, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-12181-2014, 2014.

Yu, F. and Luo, G.: Modeling of gaseous methylamines in the global atmosphere: impacts of oxidation and aerosol uptake, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 12455–12464, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-12455-2014, 2014.

Zhang, Q., Alfarra, M. R., Worsnop, D. R., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Canagaratna, M. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Deconvolution and quantification of hydrocarbon-like and oxygenated organic aerosols based on aerosol mass spectrometry, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 4938–4952, https://doi.org/10.1021/es048568l, 2005.