the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The critical role of oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) in shaping photochemical O3 chemistry and control strategy in a subtropical coastal environment

Lirong Hui

Xin Feng

Hao Sun

Jia Guo

Yang Xu

Yao Chen

Penggang Zheng

Photochemical ozone (O3) pollution remains a persistent environmental challenge, and growing evidence highlights the critical role of oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) in photochemical processes. However, comprehensive and quantitative measurements of OVOCs remain limited. This study investigates the impact of OVOCs on O3 formation mechanisms and radical budgets by intergrating high-resolution field measurements from a subtropical coastal region in South China with observation-based photochemical modeling. 63 OVOC species were measured by a proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PTR-ToF-MS), and accounted for 72 %–77 % of total VOC concentrations. The O3-precusor relationship analysis revealed a transition regime for O3 formation and high sensitivity to OVOCs. OVOC-related reactions, including OVOC photolysis, OVOC oxidation by OH and NO3 radicals, contributed approximately 36 %–73 % to daytime production rates of HO2 and RO2 radicals. Model simulations without comprehensive consideration of OVOCs would significantly underestimate daytime production rates of O3 and ROx radicals by 41 %–48 %, and shift the diagnosis of O3 formation from a transition regime to a VOC-limited regime, leading to biased policy recommendations and potentially ineffective control strategies. These findings underscore the critical role of OVOCs in atmospheric photochemistry and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive OVOC quantification to improve OVOC-inclusive model frameworks. Such improvements are essential for accurately characterizing O3-precursor relationships and for developing effective and sustainable strategies to mitigate regional O3 pollution.

- Article

(3925 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(5612 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Ground-level ozone (O3) is a significant secondary air pollutant and a major component of photochemical smog, posing serious threats to human health, ecosystems, and the climate (Feng et al., 2019; Yue and Unger, 2014; Mills et al., 2018). Elevated O3 levels remain a persistent environmental challenge in many urban regions worldwide, especially a notable upward trend in East Asia (Li et al., 2019b; Li et al., 2020). O3 formation in the troposphere arises from complex photochemical reactions involving nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) under the sunlight (Zhao et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). The oxidation of VOCs by hydroxyl (OH) radical plays a central role in producing peroxy radicals, such as hydroperoxyl (HO2) and alkyl peroxy (RO2) radicals, which sustain the chain reactions driving photochemical O3 production (Lyu et al., 2022).

Previous studies have underscored the importance of non-methane hydrocarbons, particularly alkenes and aromatics, as major precursors of O3 formation, leading to targeted control measures in various regions (Li et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2019). However, recent research highlights the crucial roles of oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) in regulating atmospheric oxidation capacity and contributing to radical production (Wang et al., 2022a; Shen et al., 2021; Chai et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). OVOCs, such as carbonyls and alcohols, can be emitted directly from diverse sources or formed as secondary products from VOC oxidation (Mellouki et al., 2003). These OVOC compounds can further react with OH radical or undergo photolysis processes, serving as significant sources of HO2 and RO2 radicals that amplify radical cycling and promote O3 formation (Xue et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020b). Despite their importance, the diversity and high reactivity of OVOCs introduce substantial uncertainties in atmospheric chemistry and air quality models, particularly in regions with limited OVOC measurements.

Traditional analytical techniques such as gas chromatography (GC) coupled with flame ionization or mass spectrometry detection (FID/MS) have been widely used to measure non-methane hydrocarbons, but only a subset of OVOCs (Huang et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019a; Han et al., 2019). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) can detect several carbonyl compounds, such as formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acetone, but its reliance on offline sampling limits its temporal resolution, making it less effective for capturing real-time atmospheric variations (Lu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2024). Furthermore, many other key OVOC species, such as larger aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, organic peroxides, and other multifunctional compounds, have been rarely measured and poorly characterized in ambient air, which may result in underestimating the role of OVOCs in atmospheric chemistry (Wang et al., 2022a). While NOx and VOCs are well-recognized as the primary drivers of O3 formation, the role of OVOCs in shaping photochemical O3 chemistry has received comparatively less attention due to limited field observations and insufficient representation in chemical models. In addition, previous model studies tended to considerably underestimate ROx (OH, HO2 and RO2) radicals compared to observation (Hofzumahaus et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2019; Rohrer et al., 2014). Some studies have attempted to address these gaps by simulating unmeasured OVOC species using photochemical box model, but large uncertainties still exist, largely due to missing OVOC primary sources, incomplete or underestimated secondary chemical pathways (Karl et al., 2018; Mo et al., 2016; Bloss et al., 2005; Li et al., 2014). These knowledge gaps hinder an accurate understanding of the O3-precursor relationship, complicating the development of effective control strategies.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the role of OVOCs in photochemical O3 chemistry, a continuous field campaign was conducted at a coastal suburban site in Hong Kong in South China. High-resolution measurements of more than sixty OVOC species were measured using proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PTR-ToF-MS). By integrating these measurements into a model simulation framework, we quantified the contributions of OVOCs to radical production and O3 formation, and examined their impacts on O3-precursor relationship, providing critical insights into the formulation of targeted strategies for mitigating O3 pollution in this subtropical region and similar environments.

2.1 Field measurement and instrumentation

Field measurements were conducted at a suburban coastal site (22.33° N, 114.27° E) located at the campus of The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) in eastern Hong Kong. Situated on a cliff overlooking the sea, the site is near a hotel and a construction project, which may introduce influences from construction activities, household activities, and vehicle emissions. The continuous field campaign spanned from 4 September to 20 December in 2021, covering three seasons: summer (4 September–12 October), autumn (13 October–1 December), and early winter (2–20 December). Seasonal classification in this study was based on the occurrence of synoptic events and abrupt changes in key meteorological parameters, including upper-level wind direction, sea-level pressure, and dew point temperature (Fig. S1), as detailed in our previous studies (Feng et al., 2023). The measurement site is generally affected by long-range regional transport of aged air masses from South and East China due to the Asian monsoon, as well as fresh emission plumes from Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta region (Ding et al., 2013).

A PTR-ToF-MS (Ionicon Analytik GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria) with H3O+ as the primary reaction ion was used to measure the gaseous VOC and OVOC species with high time resolution of 10 s during the whole field campaign. Ambient air was drawn from a -inch (6.35 mm) stainless-steel sampling manifold with an inert silicon-based coating at a flow rate of 5 L min−1, and a subsample of filtered air via a -inch (approximately 1.59 mm) polyetheretherketone (PEEK) tube was directed to the PTR at a frow rate of 100 mL min−1. A polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane particle filter was installed to prevent particulate matter, dust and debris from entering the instrument. To minimize potential cumulative adsorption effects, the filter was replaced frequently throughout the campaign. The sampling inlet was maintained at 80 °C throughout the measurements to mitigate humidity-related effects, reduce adsorption losses, and ensure gas-phase stability of target compounds prior to ionization and detection. It should be note that this heating may unintentionally promote the volatilization of some organic compounds from aerosols, thus causing positive artifacts. The instrument operated under optimized conditions: drift tube temperature maintained at 80 °C, drift voltage at 520 V, and drift tube pressure at 2.8 mbar, achieving a field density ratio () of 98 Td (1 Td = 10−17 V cm2). Lower ratios can lead to a higher proportion of primary ions forming water hydronium clusters (Holzinger et al., 2019), and thus the of 98 Td was selected to balance ion fragmentation and water cluster formation, which can effectively suppress water clusters formation, thereby minimize the strong humidity dependence of the target species (Yuan et al., 2017).

Automatic mass calibration was conducted every 100 s using the built-in Ionicon permeation unit (PerMasCal), which releases strong signals of 203.943 (C6H4I2H+, fragment) and 330.848 (C6H4I2H+). Background measurement and multi-point calibration were conducted periodically during the field campaign using a Liquid Calibration Unit (LCU, Ionicon) with pure nitrogen and multi-component VOC gas standards. 19 standard gases were used for multi-point calibration, achieving linear correlation coefficients (R2) above 0.99 (Table S1). The limit of detection (LOD) for each species was defined as three times the standard deviation (3σ) of background signal (Zhou et al., 2019), ranged from approximately 0.009 to 0.094 ppbv (Table S1). Transmission correction was applied using a set of reference compounds, including benzene ( 79.054), toluene ( 93.070), m-xylene ( 107.086), 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene ( 121.101), dichlorobenzene ( 146.976), and trichlorobenzene ( 180.937). In total, 117 species were identified and quantified by attributing the measured ion masses to the most plausible molecular contributors. This attribution was based on molecular mass, elemental combinations consisting of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen atoms, reflecting plausible atmospheric molecules and functional groups, as well as prior studies utilizing high-resolution mass spectrometry (Yuan et al., 2017; Koss et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2020), as summarized in Table S2. For the remaining 98 species lacking available calibration standards, concentrations were determined using an assumed proton transfer reaction rate coefficient of 2 × 10−9 cm3 s−1, combined with mass-dependent transmission correction (Zhang et al., 2022). To reduce uncertainties for uncalibrated compounds, an approach developed by Sekimoto et al. (2017), which estimates proton-transfer rate constants based on molecular properties such as polarizability and dipole moment, provides a scientifically robust method that could be applied in future work.

However, we acknowledge the several caveats associated with the quantification. First, PTR-ToF-MS is limited in its ability to differentiate between isomeric compounds, accurate quantification of individual compounds remains challenging. Most molecular formulas were therefore evenly distributed among potential isomers (e.g., phenols, nitrophenols), while specific formulas for aldehydes and ketones were identified based on prior studies using GC-PTR-ToF measurement. For example, for C10H16, given that α-pinene and β-pinene are typically the predominant contributors (Kim et al., 2009; Byron et al., 2022; Kammer et al., 2020), an equal 50:50 allocation between the two species was adopted as a modeling assumption for the apportionment. As important oxidation products, C4H6O was apportioned as 48 % methyl vinyl ketone (MVK), 19 % methacrolein (MACR), and 33 % crotonaldehyde for model simulations, based on previous studies using PTR-MS combined with GC pre-separation (Koss et al., 2018). Although we attempted to assign signals based on likely contributors informed by literature, this approach introduces uncertainties in the molecular-level identification due to variability in instrument sensitivity, resolution, ambient conditions, and sampling periods across studies. These factors can affect the observed chemical composition and relative contributions of individual species, thereby influencing the accuracy of signal attribution and subsequent model inputs. Second, the ions detected by PTR-ToF-MS can include fragmentation products or hydrated clusters, particularly for highly functionalized OVOCs, which may lead to over- or underestimation of specific compounds if not correctly interpreted. To minimize uncertainties arising from water cluster interferences, ions susceptible to such effects, such as C4H6H+ ( 55.054), which overlaps with the H3O+(H2O)2 cluster, were excluded from compound identification and subsequent analysis in this study. Regarding impacts from fragmentation, for example, C5H8 may be affected by fragment interferences from higher-carbon aldehydes and cycloalkanes (Coggon et al., 2024; Claflin et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2025), therefore, the attribution of C5H8 to isoprene follows the proportion of 63 % reported in previous studies employing PTR-MS coupled with GC pre-separation, which effectively minimizes interference from fragments of higher molecular compounds (Koss et al., 2018). A sensitivity test assuming all C5H8H+ signals as isoprene was conducted, and it leads to a 2.9 %–6.0 % increase in daytime O3 and ROx production rates compared to the above assumption. Given these limitations, our quantification of the 63 OVOCs measured by PTR should be considered as semi-quantitative for 55 uncalibrated species, and as high-confidence for the 8 calibrated species.

In addition, canister samples of VOCs were collected every 3 h from 09:00 to 18:00 LT in three seasons, and nonmethane hydrocarbons and alkyl nitrates were analyzed using gas chromatograph system equipped with mass spectrometry, flame ionization, and electron capture detectors (GC-MS/FID/ECD). PTR-based concentrations of isoprene, benzene, and toluene, assigned using fragmentation assumptions from previous online GC-PTR-ToF, were compared with canister measurements. The two datasets showed overall good agreement (R2 = 0.70–0.86), although PTR reported slightly higher concentrations, with slope of 1.25, 1.51 and 1.63 for isoprene, toluene, and benzene, respectively. This comparison indicates that the derived PTR data are reliable within an acceptable uncertainty range. Trace gases including O3, NOx (nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2)) and carbon monoxide (CO) were measured by O3 analyzer (Thermo Scientific, model 49i), NOx analyzer (Ecotech Serinus 40) and CO analyzer (Thermo Scientific, model T300), respectively. The meteorological parameters including temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), wind speed (WS), and wind direction (WD) were recorded by a Weather Station. Detailed descriptions of the instruments are available in previous work (Hui et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2024).

2.2 Photochemistry Modeling

A zero-dimensional photochemical box model (the Framework for 0-D Atmospheric Modeling, F0AM v4.2.2) coupled with the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM) v3.3.1 was applied to simulate the atmospheric photochemistry of observed species. The MCM v3.3.1 is a nearly explicit gas-phase chemical mechanism describing over 17000 reactions and 5800 primary, secondary, and radical species. The model simulation was constrained by observed hourly data of meteorological parameters (T, RH, and pressure), trace gases (O3, NO, NO2, and CO), 38 VOC species measured by GC-MS/FID/ECD (Table S3), and 88 species measured by PTR-ToF-MS (Table S2). For the offline canister VOC samples measured by GC-MS/FID/ECD, daytime data from 09:00 to 18:00 were linearly interpolated to an hourly resolution for the model input (Yang et al., 2018), while nighttime concentrations of unmeasured C2-C10 hydrocarbons (excluding isoprene and monoterpenes) and alkyl nitrates were estimated using linear regression relationships with continuously measured hydrocarbons (e.g., C3H6, C5H10, C6H10) and nitrophenols obtained from PTR-ToF-MS measurements. The PTR measured species used in the linear regression calculation were selected based on their strong correlations with corresponding compounds in the canister data to ensure more reliable estimates. These approximations were primarily used to pre-run the model and ensure continuous modeling, and were not expected to significantly affect the daytime simulation results, since photochemical activity is minimal during nighttime, and most hydrocarbons are less reactive in the absence of sunlight (Chen et al., 2020). Photolysis frequencies within the model were calculated as the function of solar zenith angle (Wolfe et al., 2016). Observation-based simulations were performed for consecutive days with high O3 concentrations during summer (8 September–2 October), autumn (12–30 November), and early winter (4–19 December). Three days from summer (11, 12, and 17 September) were selected as the case study of summer high-O3 episode, where the maximum O3 concentration exceeded 110 ppbv. The model was pre-run for four days to stabilize the concentrations of unconstrained species, with results from the 5th day used for further analysis.

Model performance was evaluated using the index of agreement (IOA), as illustrated in Eq. (1) (Huang et al., 2005), with values of 0.81–0.87 for the simulated O3 across seasons in this study, comparable to previous studies (0.6–0.9), suggesting that the abundance and variation of O3 were deemed reasonably reproduced (He et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2018b, 2017, 2015).

Where Oi and Si represent the measured and simulated O3 concentration, respectively; represents the mean measured O3 concentration; and n represents the number of samples. The index of IOA typically ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating stronger alignment between simulation and observation.

Dominant photochemical production pathways (HO2 + NO, RO2 + NO) and destruction pathways (O3 photolysis, O3 + OH, O3 + HO2, VOCs + O3, NO2 + OH) of O3 were determined using Eqs. (2)–(4) (Tan et al., 2019a; Wang et al., 2018a). The production rates of ROx radicals (OH, HO2 and RO2 radicals) were also calculated, incorporating primary sources such as photolysis reactions (i.e., O3 photolysis, OVOC photolysis, etc.), VOC reactions with O3 and NO3, as well as recycling processes (Xue et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018a; Tan et al., 2019b).

To evaluate the model uncertainties associated with the presence of multiple isomers in PTR-ToF-MS measurements, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by estimating the lower and upper limits of ROx radicals and O3 production rates with possible isomers. For OVOCs measured by the PTR with multiple isomers, each molecular formula was assigned either to the isomer with the minimum or maximum photolysis frequencies and KOH values among all plausible isomeric structures. Specifically, for OVOCs with isomers containing both aldehydes and ketones, the upper bound was defined by assigning OVOCs to aldehydes with the highest photolysis frequency, while the lower bound assumed ketones with the lowest photolysis frequency (e.g., C4H6O, C4H8O). For OVOCs whose isomers do not undergo photolysis but are susceptible to OH oxidation, the upper and lower bounds were determined based on OH reactivity, with the upper and lower bounds corresponding to the isomers with highest and lowest KOH values, respectively (e.g., C8H10O, C6H8O2). This approach accounts for the variability in chemical reactivity stemming from the unresolved isomer distribution and provides a range of potential impacts on atmospheric ROx radicals generation and O3 formation.

Where P(O3), L(O3), and Net P(O3) represents the production rate, loss rate, and net production rate of O3, respectively. The O3 photolysis was represented as the reactions of O(1D) and H2O (Shen et al., 2021). VOCs here included both constrained VOCs and model simulated VOCs. The constants (k) represent the rate coefficients of each reaction.

The O3-precursors relationship was characterized using the relative incremental reactivity (RIR) method, calculated by Eq. (5) (Liu et al., 2021). O3 formation regime was further characterized by O3 isopleth method, which was derived by scaling precursor concentrations (10 %–200 % of original values) to simulate O3 concentrations under varying VOCs and NOx levels (Tan et al., 2018).

Where RIR represents relative incremental reactivity; X represents specific O3 precursor (i.e., VOCs, NOx); S(X) represents observed concentration of precursor X (ppbv); ΔS(X) represents hypothetical change of the concentration of precursor X; represents net O3 production in a base run with original observed precursor concentrations, while represents the net O3 production in a second run with a hypothetical change ΔS(X) of 10 % in this study. The net O3 production was calculated by Eq. (4). A larger positive RIR value indicates higher sensitivity of O3 production to this precursor, implying that reducing emissions of this precursor would more effectively suppress O3 formation. Conversely, a negative RIR value suggests that emission reductions of this precursor could paradoxically increase O3 production (Wang et al., 2018b).

3.1 Overview of the observations

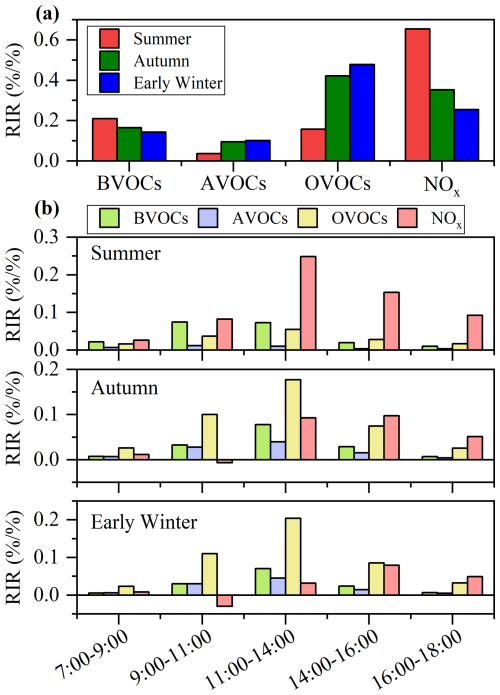

During the campaign, 117 species were continuously measured using the PTR-ToF-MS, including 2 biogenic VOCs (BVOCs), 24 anthropogenic VOCs (AVOCs, comprising alkenes, cycloalkanes, and aromatics), 63 OVOCs (categorized as CxHyO1–3), and 28 nitrogen/sulfur containing VOCs (-containing VOCs). BVOCs here refer specifically to C5H8 and C10H16, which primarily represent isoprene and monoterpenes (e.g., pinenes, limonene, camphene, etc.), respectively. It should be noted that C5H8 may be affected by fragment interferences from higher-carbon aldehydes and cycloalkanes (Coggon et al., 2024; Claflin et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2025), which may potentially lead to an overestimation of BVOCs, particularly isoprene. The time series of different VOC groups, meteorological parameters, and trace gases are shown in Fig. S2. The campaign witnessed twenty O3 episode days (maximum O3 value > 80 ppbv) across three seasons, with three extreme episodes exceeding 110 ppbv (defined as high-O3 episodes) in summer. The measured showed the highest total concentration in early winter (47.84 ppbv), followed by autumn (44.26 ppbv) and summer (28.83 ppbv), which is consistent with the O3 seasonal trend (Fig. S5). Furthermore, the total concentration was much higher during O3 episode days and reached 60.96 ppbv during summer high-O3 episode days, with 76 % contribution from OVOCs, emphasizing their pivotal role in O3 production. OVOCs, AVOCs, and -containing VOCs increased progressively from summer to early winter, with the most pronounced rise observed between summer and autumn (Fig. 1a). In contrast, BVOCs displayed an opposite seasonal pattern, with concentrations peaking in summer. OVOCs were the dominant group across all seasons, accounting for 72 %–77 % of the total concentration, with CxHyO1 and CxHyO2 accounting for 51 %–53 % and 17 %–24 %, respectively (Fig. 1b). CH4O (methanol) was the most abundant OVOC species, with average concentration ranging from 5.98–10.10 ppbv across seasons, followed by C2H4O2 (1.91–5.75 ppbv), C3H6O (4.22-5.67 ppbv) and C2H4O (1.85–3.86 ppbv), which primarily correspond to acetic acid, acetone and acetaldehyde, respectively, as shown in Fig. S3. A statistical summary of concentrations for each season is provided in Table S2.

The diurnal variations of OVOC subgroups across three seasons are shown in Fig. 1c. CxHyO1–3 groups displayed similar diurnal patterns in different seasons, characterized by pronounced daytime enhancements, particularly for species such as C2H4O (acetaldehyde), C3H6O (acetone), C4H6O (MVK and MACR) and C2H4O2 (acetic acid) (Fig. S4). These species increased at about 07:00 local time (LT), peaked during 12:00–17:00 LT in the afternoon, and then gradually decreased, which was aligned closely with the diurnal patterns of O3 (Fig. S5), indicating their likely formation through photochemical reactions. Notably, C4H6O (MVK and MACR), the key oxidation products of isoprene (Li et al., 2021), showed pronounced photochemical daytime peaks but significantly higher concentrations in summer compared to autumn and early winter, consistent with the seasonal trend of its precursor (Fig. S6), which was different from other OVOCs formed by anthropogenic precursors. CH4O (methanol) exhibited clear daytime enhancements in summer and autumn but showed no distinct diurnal pattern in early winter (Fig. S4). Instead, it maintained relatively high levels throughout the day and night in early winter, likely reflecting the larger contributions from regional background sources, such as anthropogenic emissions and background transport (Brito et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2019). In addition to precursor availability and photochemical activity, diurnal variations in boundary layer height may also influence OVOC concentrations by modulating vertical mixing and accumulation processes. These findings underscore the significance of OVOCs in atmospheric chemistry, given their abundance and complex roles in photochemical reactions.

Figure 1(a) The concentrations of different VOC groups in summer, autumn and early winter. The box plots show mean values (square), median (line within the box), interquartile range (IQR, 25 %–75 %), and whiskers extending to ±1.5 × IQR. (b) The contributions of different VOC groups to total concentration in summer (inner), autumn (middle), and early winter (outer). (c) Diurnal variations of OVOC subgroups across three seasons.

3.2 O3-precursor relationships

To further evaluate the contribution of various VOCs to O3 formation, the RIR values of key O3 precursors (including BVOCs, AVOCs, OVOCs, and NOx) were calculated for different seasons based on the model simulations. It should be noted that the subgroups of OVOCs and AVOCs analyzed here differ slightly from those in Sect. 3.1, due to the limitations that MCM does not include all mechanisms for all observed OVOC species. Additionally, C2–C10 hydrocarbons measure by GC-MS/FID/ECD were also included in the subgroup of AVOCs for this analysis. The species included in RIR calculation comprised 3 BVOC species, 45 AVOC species and 63 OVOC species, with detailed information summarized in Table S4.

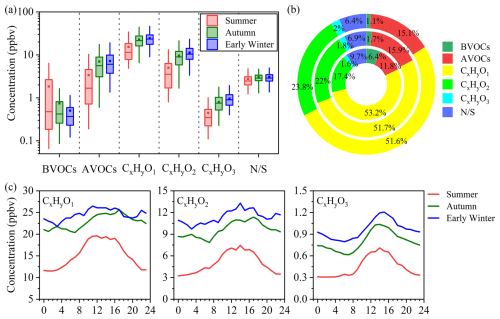

The RIR values for all VOCs subgroups and NOx were positive across three seasons (Fig. 2a), indicating a transition regime of O3 formation in the study region and that reduction in VOCs and/or NOx would lead to decreases in O3 levels. This result was different from previous studies which reported dominantly VOC-limited regime of O3 formation in Hong Kong (Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2013). In summer, NOx exhibited the highest RIR value (0.65), followed by BVOCs (0.21) and OVOCs (0.16). Similar trend was observed during high-O3 episode days (Fig. S7), indicating that summer O3 formation is more sensitive to NOx. By contrast, in autumn and early winter, OVOCs exhibited the highest RIR values (0.42–0.48), followed by NOx (0.25–0.35) and BVOCs (0.14–0.16), indicating that O3 formation in these seasons is more sensitive to OVOCs. It should be noted that current photochemical models typically represent monoterpenes using only α- and β-pinenes, neglecting some highly reactive species such as limonene. Moreover, gaps in the MCM, such as the absence of certain highly reactive monoterpenes and associated oxidation pathways, may further introduce uncertainties in assessing the role of BVOCs in atmospheric photochemistry.

The dramatic seasonal increase in the RIR value of OVOCs, coupled with a decline in those of NOx highlights the need for different control strategies to effectively reduce O3 levels depending on the seasons. Previous RIR studies of O3 formation have primarily focused on AVOCs, BVOCs and NOx, with limited consideration of OVOCs (Wang et al., 2018b; Tan et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022b; Yu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2022). Recent studies, however, have reported relatively high RIR values for OVOCs when they are included in the simulations, although these findings are confined to a narrow subset of OVOCs, mainly short-chain carbonyl compounds, based on low-resolution offline measurements (Shen et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024; Feng et al., 2023). This study integrates a much broader spectrum of OVOCs (including aldehydes, ketones, organic acids, alcohols, phenolic compounds, etc.) supported by high-resolution measurement into the observation-constrained modeling framework. This improved chemical comprehensiveness allows for a more robust characterization of OVOCs reactivity, particularly their contributions to radical production and O3 sensitivity. Nevertheless, due to the inherent limitations of PTR-ToF-MS, accurate quantification of isomers with distinct chemical reactivities remains challenging, introducing some uncertainties in atmospheric photochemical modeling.

In addition, we have further examined the diurnal variation of RIR values for O3 precursors in different seasons, as shown in Fig. 2b. Significantly higher positive RIR values were observed for NOx than other precursors in the afternoon of summer and during the episodes (Fig. S8), indicating a consistently strong sensitivity of O3 production to NOx. In autumn and early winter, OVOCs exhibited higher positive RIR values during the morning (09:00–11:00) and midday (11:00–14:00), underscoring their prominent role in O3 formation. The majority of NOx RIR values were positive except for the negative values in the morning (09:00–11:00), reflecting a shift from a VOC-limited regime in the morning to a transitional regime at the noon and in the afternoon. By late afternoon, the O3 formation regime became increasingly sensitive to NOx. Notably, in autumn, RIR values of NOx were comparable or even surpassed these of OVOCs in the afternoon. This variation is likely attributed to fresh NOx emissions from vehicle and/or household combustion activities in the morning, which decrease in the afternoon due to photochemical consumption, atmospheric diffusion, and dry deposition (Liu et al., 2021). These findings indicate a clear diurnal transformation pattern in O3 formation regimes during the photochemical active seasons (autumn and early winter) in Hong Kong. Specifically, the regime transitions from VOC-limited in the morning to a transitional regime with higher sensitivity to OVOCs at midday, and then to a general transitional regime with sensitivity to both OVOCs and NOx in the afternoon, and becomes increasingly NOx sensitive by late afternoon.

3.3 O3 formation mechanism and radical budget

The main pathways of daytime O3 production and destruction in three seasons were further explored using the photochemical box model, as shown in Fig. S9. The daytime average net O3 production rate (Pnet) was 5.8, 6.1, and 6.4 ppbv h−1 in summer, autumn, and early winter, respectively, much lower than that during summer high-O3 episode (13.1 ppbv h−1, Fig. S9b). These trends were consistent with the diurnal patterns of observed O3 concentrations (Fig. S10). Daytime O3 production (P(O3)) was dominated driven by the reactions of HO2 + NO and RO2 + NO, contributing 43.8 %–53.0 % and 47.0 %–56.2 %, respectively. Among the diverse RO2 + NO reactions (involving over 1000 different RO2 radicals), the top 10 pathways contributed 51.1 %–54.3 % of the total production rates (Fig. S11). CH3O2 + NO was the dominant pathway, accounting for 13.5 %–19.3 % of O3 production. The CH3O2 radical could be generated through various reactions, including the photolysis of OVOCs (e.g., acetaldehyde, acetone) and VOCs reactions with OH radical (e.g., acetic acid), etc. Additionally, reactions of C2 radicals with NO contributed significantly (10.4 %–18.5 %), with CH3CO3 + NO being the most prominent (10.4 %–15.2 %). Seasonal variations in RO2 + NO pathways were evident. RO2 radicals from BVOCs (such as isoprene and pinenes) contributed more to summer (20.7 %) than autumn and early winter (6.3 %–6.9 %), reflecting the seasonal patterns of vegetation emissions. Conversely, RO2 radicals derived from anthropogenic sources, such as aromatics, played a larger role in autumn and early winter (8.6 %–9.1 %). Daytime O3 destruction also exhibited seasonal differences. In autumn and early winter, the dominant loss pathway was OH + NO2 (51.1 %–57.0 %), followed by VOCs + O3 (17.9 %–23.2 %) and O3 + HO2 (12.6 %–13.8 %). In summer, however, VOCs + O3 accounted for a much higher fraction of O3 loss (43.3 %) compared to other seasons, especially the reactions with BVOCs including α-pinene and isoprene.

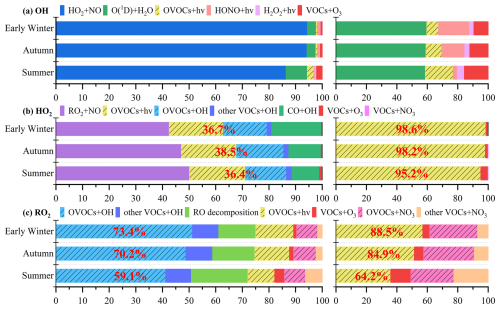

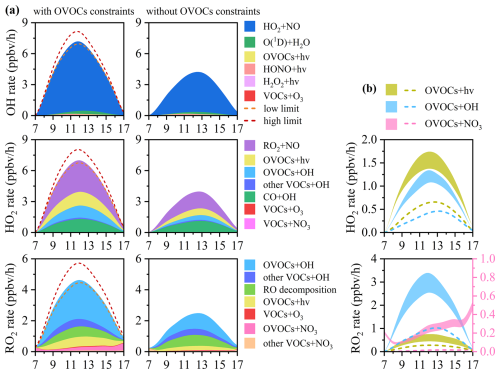

The OH, HO2, and RO2 radicals play important roles in the initiation and propagation of atmospheric photochemical reactions (Wang et al., 2022b). The daytime production budgets of these radicals were analyzed across three seasons, as shown in Fig. S12, with detailed contributions of each pathway presented in Fig. 3. Daytime OH and HO2 radical production was highest in early winter, with lower values in summer and autumn. Radical recycling via HO2 + NO was the dominant source of OH production (86.4 %–94.4 %) across three seasons, while O3 photolysis (via O(1D) + H2O) served as the main primary source for OH production, accounting for around 60 % of primary OH production rate. In addition, the photolysis reactions of OVOCs, HONO and VOCs + O3 contributed 7.6 %–18.3 %, 2.7 %–20.4 %, and 9.3 %–15.6 % of primary OH production rates, respectively. Similarly, the largest source of HO2 radicals was radical recycling through RO2 + NO reactions, contributing 42.5 %–50.2 %. OVOC photolysis accounted for 20.3 %–21.0 % to total HO2 production rates, but dominated the primary HO2 production in three seasons (95.2 %–98.6 %). Moreover, the reactions of OVOCs + OH (15.4 %–17.7 %) and CO + OH (10.2 %–18.7 %) also played significantly roles in total HO2 production. The dominant source of daytime RO2 production was the reaction of VOCs + OH, accounting for 50.8 %–61.1 %, with OVOCs + OH contributing the majority proportion (41.2 %–51.3 %). Seasonal variations in OVOCs + OH contributions aligned with observed OVOC concentrations, being highest in early winter, followed by autumn and summer. Additional RO2 sources included RO decomposition (13.9 %–21.3 %), OVOC photolysis (10.0 %–14.2 %), and VOCs + NO3 (9.6 %–14.1 %). OVOC photolysis was also an important primary source of daytime RO2 production (36.0 %–57.0 %). During summer high-O3 episodes, daytime ROx radical production rates were significantly higher, and O3 photolysis and VOCs + O3 reactions contributed more substantially to ROx production (Fig. S13). Furthermore, the results highlight the importance of VOCs + NO3, especially OVOCs + NO3, as a source of RO2 radicals in the daytime photochemistry, particularly in polluted atmosphere, consistent with prior observations at an urban site in Hong Kong (Xue et al., 2016). In total, OVOCs played a significant role in the formation of HO2 and RO2 radicals across all three seasons. OVOC-related reactions, including OVOC photolysis, OVOCs + OH oxidation, and OVOCs + NO3, accounted for 36.4 %–38.5 % and 59.1 %–73.4 % of daytime HO2 and RO2 production, respectively. These results emphasize the critical importance of OVOCs in sustaining radical cycling and driving photochemical O3 formation, especially in urban and semi-urban atmospheric environments.

Figure 3Contributions of key pathways for total daytime production rates (left) and primary daytime production rates (right) of (a) OH, (b) HO2 and (c) RO2 radicals across seasons. OVOC-related reactions including OVOC photolysis (OVOCs + hv), OVOCs oxidation by OH radicals (OVOCs + OH), and OVOCs oxidation by NO3 (OVOCs + NO3) are shaded by oblique lines. The percentage in red represents the contribution of OVOC-related reactions for overall (left) and primary (right) daytime production rates of HO2 and RO2 radicals.

3.4 Importance of OVOCs in O3 and radical formation

To better quantify the critical roles of OVOCs in photochemical O3 and radical formation, a sensitivity simulation was conducted without constraining the observed OVOC species in the model. The comparison of observed and simulated O3 concentrations under scenarios with and without OVOCs constraints across three seasons is shown in Fig. S14. Incorporating a broader range of OVOCs improved the simulation of O3, particularly in autumn and early winter, where daytime concentrations were underestimated by 26.5 % and 35.7 %, respectively, without OVOCs constraints. In contrast, the discrepancy was minimal in summer, likely due to the dominant role of NOx in O3 formation and elevated daytime NO levels during high-O3 episodes. It should be noted that the model considers only in situ photochemical processes and does not include influences such as regional transport. As a result, discrepancies between observed and simulated O3 remain, especially in autumn and early winter, when periods typically influenced by the Asian monsoon, and during nighttime when photochemical activity is minimal. Given the higher observed O3 levels in early winter and the substantial underestimation without OVOC constraints, we conducted a focused evaluation of model performance for this period.

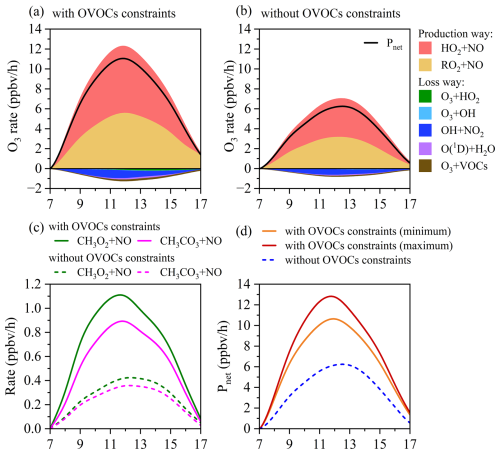

Figure 4Model simulated daytime O3 production and loss rates of main pathways in early winter (a) with and (b) without observed OVOCs constraints. The black solid line represents the net O3 production rate (Pnet). (c) The daytime reaction of the top two pathways of RO2 + NO (CH3O2 + NO, CH3CO3 + NO) towards daytime O3 formation in early winter with and without OVOCs constraints. (d) The daytime Pnet with and without observed OVOCs constraints in early winter. The orange and dark red lines represent the scenarios with the minimum and maximum OVOC contributions to Pnet, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 4a and 4b, simulated daytime P(O3) and Pnet without OVOCs constraints in early winter decreased by 44.0 % and 45.1 %, respectively, consistent with the underestimation of O3 concentrations during the same period. The reduction in RO2 + NO reaction rates (45.6 %) was slightly larger than that for HO2 + NO (42.6 %), with the most substantial decreases observed in CH3O2 + NO (61.4 %) and CH3CO3 + NO (58.6 %) pathways (Fig. 4c). These reductions were primarily attributed to the underestimation of radical precursors without OVOCs constraints. Moreover, the existence of multiple OVOC isomers detected by PTR-ToF-MS, introduces additional uncertainties in quantifying daytime O3 production. Sensitivity analysis revealed that Pnet underestimations without OVOCs constraints ranged from 43.4 % to 52.1 %, depending on the assumed photolysis frequencies and KOH values of potential isomers (Fig. 4d). These results highlight the critical role of OVOCs in O3 formation and the potentially large uncertainties in O3 modeling when their contributions are not adequately represented. The discrepancies are significantly larger than those reported in previous studies (Wang et al., 2022a; Shen et al., 2021), and likely arise from our inclusion of a broader range of OVOCs beyond commonly considered carbonyls, enhancing the chemical completeness of the model and improving the simulation accuracy.

The critical role of OVOCs in modulating atmospheric radical budgets was further quantified through scenario-based simulations. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, without OVOCs constraints led to significant reductions in the production rates of OH (40.2 %–47.4 %), HO2 (43.2 %–51.0 %) and RO2 (45.8 %–57.1 %) radicals, with ranges reflecting the minimum and maximum assumptions. These underestimations were amplified in OVOC-related reactions, where HO2 and RO2 production were reduced by 58.1 %–65.5 % and 62.0 %–72.2 %, respectively, underscoring the significance of OVOCs in radical cycling. These reductions were primarily attributed to the underestimation of OVOC photolysis (37.4 %–64.5 %) and OVOCs + OH reactions (60.0 %–71.0 %) (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, prominently large underestimations (up to 93.6 %–95.0 %) occurred in RO2 production from OVOCs + NO3 reactions (Fig. 5b), revealing a critical gap in modeling daytime NO3 oxidation of OVOCs. These discrepancies were largely due to the underestimation of multiple OVOC species, for example, methanol, acetaldehyde, and acetone were underestimated by 73 %–99 % in early winter simulations without OVOC constraints (Table S5). Similar underestimation (10 %–100 %) of simulated OVOCs have been reported in previous studies (Wang et al., 2022a). Although some carbonyl compounds are commonly included in the modeling of O3 and radical formation (Zhao et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023; Han et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2020a; Liu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022), our results highlight that many other photoreactive OVOCs remain overlooked, contributing to large uncertainties in radical simulations. A sensitivity test including only three commonly measured OVOCs (methanol, acetaldehyde, acetone) (Whalley et al., 2021; Whalley et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2021) increased daytime O3 by 14.1 % in autumn and 17.6 % in early winter compared to the case without any OVOCs constraints, yet still left 16.2 % and 24.4 % of the discrepancies unexplained (Fig. S14). In early winter, these three OVOCs increased daytime O3 and ROx production rates by 14.6 %–22.9 %, but a remaining gap of 32.8 %–36.0 % indicates that simple OVOCs alone cannot resolve the underestimation. Several less commonly measured yet reactive OVOC, such as butanedione, glycolaldehyde, cresols, and hydroxyacetone, were found to contribute significantly to daytime O3 and radical production via photolysis and OH oxidation. Together, these findings suggest that missing or unresolved primary and secondary OVOC sources, as well as incomplete representation of OVOC chemistry in current mechanisms (e.g., MCM) (Karl et al., 2018; Mo et al., 2016; Bloss et al., 2005) are major contributors to model bias. However, residual uncertainties remain due to limitations in isomer-specific quantification, emphasizing the need for improved measurement techniques to better constrain OVOC impacts in atmospheric models.

Figure 5(a) Model simulated daytime production rates of OH, HO2 and RO2 radicals of main pathways in early winter with (left) and without (right) observed OVOCs constraints. The orange and dark red dash lines represent daytime production rates with minimum and maximum scenarios, respectively. (b) The reaction rates of OVOC photolysis (OVOCs + hv), OH oxidation of OVOCs (OVOCs + OH), and NO3 oxidation of OVOCs (OVOCs + NO3) towards daytime production of HO2 and RO2 radicals in early winter. The dash lines represent the scenario without OVOCs constraints. The areas represent daytime production rates with minimum and maximum scenarios.

3.5 Implication for O3 pollution control strategies

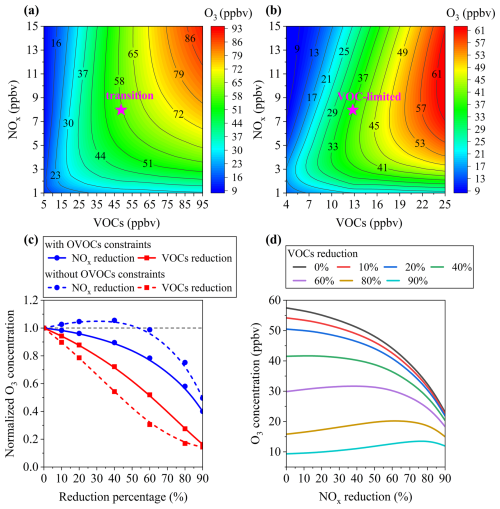

Given the critical role of OVOCs in O3 production, EKMA O3 isopleths were derived to evaluate the dependence of daytime O3 production on VOCs and NOx variations. The analysis revealed a critical difference between the two scenarios: suburban Hong Kong was classified in the transition regime with OVOCs constraints (Fig. 6a), whereas it shifted to a VOC-limited regime without OVOCs constraints (Fig. 6b). This highlights the importance of including OVOCs in modeling efforts, as their exclusion may lead to potentially misleading strategies for O3 pollution control. Figure 6c further illustrates changes in daytime O3 production in response to VOCs or NOx reductions (0 % to 90 %) under the two scenarios. With OVOCs constraints, O3 concentration would decrease with reductions in either VOCs or NOx, but more strongly with VOCs, consistent with the transition regime. In contrast, without OVOCs constraints, O3 concentration would initially increase with NOx reduction of 0 %–50 %, before declining at higher reductions. Similar patterns were observed in changes to daytime production rates of O3 and ROx radicals (Fig. S15). These results demonstrate that neglecting OVOCs exaggerates the VOC-limited degree and overestimate the effectiveness of VOCs reduction on O3 reduction, while underestimating the potential benefits of NOx control. This could lead to suboptimal or ineffective O3 mitigation strategies.

For regions in the transition regime, such as suburban Hong Kong, simultaneous reductions in both VOCs and NOx are necessary for effective O3 control. As shown in Fig. 6d, when VOC reduction is between 0 % and 40 %, any reduction in NOx would result in corresponding O3 reductions. However, at VOC reductions (60 %–90 %), minor NOx reductions would paradoxically increase O3 levels unless NOx reduction is sufficiently large to outweigh VOC reductions. Notably, when NOx reduction exceeds 90 %, O3 concentration falls below 25 ppbv, regardless of VOC levels. While such drastic emission reductions are challenging, a dual-control strategy with reduction of VOCs by 0 %–40 % and minimizing NOx emissions emerges as both feasible and effective, avoiding unintended increases in O3 levels. It should be noted that due to the absence of a robust mechanism to represent the nonlinear formation and diverse sources of OVOCs, we employed a simplified scaling approach based on precursor VOCs in O3 isopleth analysis. Despite inherent uncertainties, this provides a practical approximation for assessing OVOC impacts on O3 formation under varying emission scenarios.

Although this study focused on a representative suburban region in Hong Kong, the methodology and findings are broadly applicable to other urban and suburban regions with diverse emission profiles and photochemical regimes. In such environments, excluding OVOCs can lead to misclassification of O3 formation regimes, resulting in ineffective or counterproductive control strategies. These insights underscore the critical need for OVOCs-inclusive modeling frameworks to guide effective and science-based air quality management.

Figure 6Isopleth diagram for average daytime O3 production depending on NOx and VOCs changes in early winter (a) with and (b) without observed OVOCs constraints. The “pink star” represents the base scenario. (c) Changes in daytime O3 production with VOCs or NOx reductions from 0 % to 90 % with and without observed OVOCs constraints. The daytime average O3 concentrations were normalized to the corresponding values in the base run. The grey dash line represents the normalized O3 concentration of 1.0, indicating no O3 changing. (d) The response of daytime O3 concentration to VOCs and NOx under different reduction scenarios with observed OVOCs constraints.

This study integrated intensive field measurements with observation-based photochemical modeling to investigate the role of OVOCs in O3 and radical chemistry at a coastal suburban site in subtropical Hong Kong. High-resolution measurements using PTR-ToF-MS identified and quantified 117 species, among which 63 OVOCs contributed the majority (72 %–77 %) of total VOC concentrations across three seasons in 2021. RIR analysis revealed a transitional O3 formation regime in this suburban region, with heightened sensitivity to OVOCs, especially in autumn and early winter. Notably, O3-precursor relationship also showed diurnal variations, transitioning from a VOC-limited regime in the morning to a transitional regime during midday and afternoon, underscoring the dynamic nature of O3 chemistry.

Photochemical modeling demonstrated that OVOC-related reactions, including photolysis and oxidation by OH and NO3 radicals, contributed substantially to radical formation, accounting for 36.4 %–38.5 % of daytime HO2 and 59.1 %–73.4 % of RO2 radical production. Importantly, simulations without comprehensive OVOC constraints would significantly underestimate daytime O3 and ROx production rates by 41 %–48 % and incorrectly diagnosed the O3 chemical regime. Such misclassification may lead to misguided control strategies. Compared with previous studies that only focused on a limited set of carbonyls using offline techniques, this study expands the chemical scope by including a broader suite of OVOCs through high-resolution, real-time measurements, providing a more complete assessment of OVOC-driven radical and O3 formation. The mechanistic insights and modeling framework developed here offer practical value for diagnosing O3 formation sensitivity and designing more effective air quality management strategies in chemically complex environments globally.

Overall, these findings underscore the critical role of OVOCs in shaping atmospheric oxidation capacity and O3 formation, and highlight the need for integrating high-resolution, chemically comprehensive OVOC measurements into photochemical models. Doing so will improve the accuracy of O3 formation regimes classification, reduces uncertainties in radical budgets, and supports the development of targeted, science-based, and sustainable O3 pollution control strategies at both regional and global scales.

The datasets associated with the current study are openly available in DataSpace@HKUST at https://doi.org/10.14711/dataset/ZV6FMX (Wang, 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-18355-2025-supplement.

L.H. conducted field measurement, data analysis, model simulations and wrote the paper. Y.C. assisted in supervising the paper and provided feedback on the analysis and manuscript. D.G. and H.S. provided VOC data measured by GC-MS/FID/ECD for model simulation. J.G. and Y.C. provided help with model simulations. X.F., Y.X., and P.Z. provided feedback on the analysis and manuscript. Z.W. supervised the paper and supported the funding. All the authors participated in reviewing and editing the final version of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Environmental Central Facility of HKUST for providing the air quality supersite and equipment support on ambient measurement.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42122062), the Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee (grant nos. 16209022, 16201623, and 16211824), the Environment and Conservation Fund (grant no. 102/2023), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. GDST23SC13).

This paper was edited by Lisa Whalley and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bloss, C., Wagner, V., Bonzanini, A., Jenkin, M. E., Wirtz, K., Martin-Reviejo, M., and Pilling, M. J.: Evaluation of detailed aromatic mechanisms (MCMv3 and MCMv3.1) against environmental chamber data, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 623–639, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-623-2005, 2005.

Brito, J., Wurm, F., Yanez-Serrano, A. M., de Assuncao, J. V., Godoy, J. M., and Artaxo, P.: Vehicular Emission Ratios of VOCs in a Megacity Impacted by Extensive Ethanol Use: Results of Ambient Measurements in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 11381–11387, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b03281, 2015.

Byron, J., Kreuzwieser, J., Purser, G., van Haren, J., Ladd, S. N., Meredith, L. K., Werner, C., and Williams, J.: Chiral monoterpenes reveal forest emission mechanisms and drought responses, Nature, 609, 307–312, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05020-5, 2022.

Chai, W., Wang, M., Li, J., Tang, G., Zhang, G., and Chen, W.: Pollution characteristics, sources, and photochemical roles of ambient carbonyl compounds in summer of Beijing, China, Environ. Pollut., 336, 122403, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122403, 2023.

Chen, J., Liu, T., Gong, D., Li, J., Chen, X., Li, Q., Liao, T., Zhou, Y., Zhang, T., Wang, Y., Wang, H., and Wang, B.: Insight into decreased ozone formation across the Chinese National Day Holidays at a regional background site in the Pearl River Delta, Atmos. Environ., 315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.120142, 2023.

Chen, T., Xue, L., Zheng, P., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Sun, J., Han, G., Li, H., Zhang, X., Li, Y., Li, H., Dong, C., Xu, F., Zhang, Q., and Wang, W.: Volatile organic compounds and ozone air pollution in an oil production region in northern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 7069–7086, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-7069-2020, 2020.

Cheng, H., Guo, H., Wang, X., Saunders, S. M., Lam, S. H., Jiang, F., Wang, T., Ding, A., Lee, S., and Ho, K. F.: On the relationship between ozone and its precursors in the Pearl River Delta: application of an observation-based model (OBM), Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 17, 547–560, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-009-0247-9, 2010.

Claflin, M. S., Pagonis, D., Finewax, Z., Handschy, A. V., Day, D. A., Brown, W. L., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., Jimenez, J. L., Ziemann, P. J., de Gouw, J., and Lerner, B. M.: An in situ gas chromatograph with automatic detector switching between PTR- and EI-TOF-MS: isomer-resolved measurements of indoor air, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 14, 133–152, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-14-133-2021, 2021.

Coggon, M. M., Stockwell, C. E., Claflin, M. S., Pfannerstill, E. Y., Xu, L., Gilman, J. B., Marcantonio, J., Cao, C., Bates, K., Gkatzelis, G. I., Lamplugh, A., Katz, E. F., Arata, C., Apel, E. C., Hornbrook, R. S., Piel, F., Majluf, F., Blake, D. R., Wisthaler, A., Canagaratna, M., Lerner, B. M., Goldstein, A. H., Mak, J. E., and Warneke, C.: Identifying and correcting interferences to PTR-ToF-MS measurements of isoprene and other urban volatile organic compounds, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 801–825, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-801-2024, 2024.

Ding, A., Wang, T., and Fu, C.: Transport characteristics and origins of carbon monoxide and ozone in Hong Kong, South China, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 118, 9475–9488, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50714, 2013.

Feng, X., Guo, J., Wang, Z., Gu, D., Ho, K.-F., Chen, Y., Liao, K., Cheung, V. T. F., Louie, P. K. K., Leung, K. K. M., Yu, J. Z., Fung, J. C. H., and Lau, A. K. H.: Investigation of the multi-year trend of surface ozone and ozone-precursor relationship in Hong Kong, Atmos. Environ., 315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.120139, 2023.

Feng, Z., De Marco, A., Anav, A., Gualtieri, M., Sicard, P., Tian, H., Fornasier, F., Tao, F., Guo, A., and Paoletti, E.: Economic losses due to ozone impacts on human health, forest productivity and crop yield across China, Environ. Int., 131, 104966, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.104966, 2019.

Guo, H., Ling, Z. H., Cheung, K., Jiang, F., Wang, D. W., Simpson, I. J., Barletta, B., Meinardi, S., Wang, T. J., Wang, X. M., Saunders, S. M., and Blake, D. R.: Characterization of photochemical pollution at different elevations in mountainous areas in Hong Kong, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 3881–3898, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-3881-2013, 2013.

Guo, W., Yang, Y., Chen, Q., Zhu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Li, G., Sun, W., and She, J.: Chemical reactivity of volatile organic compounds and their effects on ozone formation in a petrochemical industrial area of Lanzhou, Western China, Sci. Total Environ., 839, 155901, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155901, 2022.

Han, C., Liu, R., Luo, H., Li, G., Ma, S., Chen, J., and An, T.: Pollution profiles of volatile organic compounds from different urban functional areas in Guangzhou China based on GC/MS and PTR-TOF-MS: Atmospheric environmental implications, Atmos. Environ., 214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.116843, 2019.

Han, J., Liu, Z., Hu, B., Zhu, W., Tang, G., Liu, Q., Ji, D., and Wang, Y.: Observations and explicit modeling of summer and autumn ozone formation in urban Beijing: Identification of key precursor species and sources, Atmos. Environ., 309, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119932, 2023.

He, Z., Wang, X., Ling, Z., Zhao, J., Guo, H., Shao, M., and Wang, Z.: Contributions of different anthropogenic volatile organic compound sources to ozone formation at a receptor site in the Pearl River Delta region and its policy implications, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 8801–8816, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-8801-2019, 2019.

Hofzumahaus, A., Rohrer, F., Lu, K., Bohn, B., Brauers, T., Chang, C.-C., Fuchs, H., Holland, F., Kita, K., Kondo, Y., Li, X., Lou, S., Shao, M., Zeng, L., Wahner, A., and Zhang, Y.: Amplified Trace Gas Removal in the Troposphere, Science, 324, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164566, 2009.

Holzinger, R., Acton, W. J. F., Bloss, W. J., Breitenlechner, M., Crilley, L. R., Dusanter, S., Gonin, M., Gros, V., Keutsch, F. N., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Kramer, L. J., Krechmer, J. E., Languille, B., Locoge, N., Lopez-Hilfiker, F., Materić, D., Moreno, S., Nemitz, E., Quéléver, L. L. J., Sarda Esteve, R., Sauvage, S., Schallhart, S., Sommariva, R., Tillmann, R., Wedel, S., Worton, D. R., Xu, K., and Zaytsev, A.: Validity and limitations of simple reaction kinetics to calculate concentrations of organic compounds from ion counts in PTR-MS, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 6193–6208, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-6193-2019, 2019.

Hong, Z., Li, M., Wang, H., Xu, L., Hong, Y., Chen, J., Chen, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., Wu, X., Hu, B., and Li, M.: Characteristics of atmospheric volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at a mountainous forest site and two urban sites in the southeast of China, Sci. Total Environ., 657, 1491–1500, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.132, 2019.

Huang, J. P., Fung, J. C. H., Lau, A. K. H., and Qin, Y.: Numerical simulation and process analysis of typhoon-related ozone episodes in Hong Kong, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 110, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004jd004914, 2005.

Huang, W., Zhao, Q., Liu, Q., Chen, F., He, Z., Guo, H., and Ling, Z.: Assessment of atmospheric photochemical reactivity in the Yangtze River Delta using a photochemical box model, Atmospheric Research, 245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2020.105088, 2020a.

Huang, X. F., Wang, C., Zhu, B., Lin, L. L., and He, L. Y.: Exploration of sources of OVOCs in various atmospheres in southern China, Environ. Pollut., 249, 831–842, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.106, 2019.

Huang, X. F., Zhang, B., Xia, S. Y., Han, Y., Wang, C., Yu, G. H., and Feng, N.: Sources of oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) in urban atmospheres in North and South China, Environ. Pollut., 261, 114152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114152, 2020b.

Huang, Y., Ling, Z. H., Lee, S. C., Ho, S. S. H., Cao, J. J., Blake, D. R., Cheng, Y., Lai, S. C., Ho, K. F., Gao, Y., Cui, L., and Louie, P. K. K.: Characterization of volatile organic compounds at a roadside environment in Hong Kong: An investigation of influences after air pollution control strategies, Atmos. Environ., 122, 809–818, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.09.036, 2015.

Hui, L., Feng, X., Yuan, Q., Chen, Y., Xu, Y., Zheng, P., Lee, S., and Wang, Z.: Abundant oxygenated volatile organic compounds and their contribution to photochemical pollution in subtropical Hong Kong, Environ. Pollut., 335, 122287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122287, 2023.

Kammer, J., Flaud, P. M., Chazeaubeny, A., Ciuraru, R., Le Menach, K., Geneste, E., Budzinski, H., Bonnefond, J. M., Lamaud, E., Perraudin, E., and Villenave, E.: Biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) reactivity related to new particle formation (NPF) over the Landes forest, Atmospheric Research, 237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2020.104869, 2020.

Karl, T., Striednig, M., Graus, M., Hammerle, A., and Wohlfahrt, G.: Urban flux measurements reveal a large pool of oxygenated volatile organic compound emissions, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 1186–1191, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714715115, 2018.

Kim, S., Karl, T., Helmig, D., Daly, R., Rasmussen, R., and Guenther, A.: Measurement of atmospheric sesquiterpenes by proton transfer reaction-mass spectrometry (PTR-MS), Atmos. Meas. Tech., 2, 99–112, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2-99-2009, 2009.

Koss, A. R., Sekimoto, K., Gilman, J. B., Selimovic, V., Coggon, M. M., Zarzana, K. J., Yuan, B., Lerner, B. M., Brown, S. S., Jimenez, J. L., Krechmer, J., Roberts, J. M., Warneke, C., Yokelson, R. J., and de Gouw, J.: Non-methane organic gas emissions from biomass burning: identification, quantification, and emission factors from PTR-ToF during the FIREX 2016 laboratory experiment, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 3299–3319, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-3299-2018, 2018.

Li, B., Ho, S. S. H., Gong, S., Ni, J., Li, H., Han, L., Yang, Y., Qi, Y., and Zhao, D.: Characterization of VOCs and their related atmospheric processes in a central Chinese city during severe ozone pollution periods, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 617–638, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-617-2019, 2019a.

Li, H., Canagaratna, M. R., Riva, M., Rantala, P., Zhang, Y., Thomas, S., Heikkinen, L., Flaud, P.-M., Villenave, E., Perraudin, E., Worsnop, D., Kulmala, M., Ehn, M., and Bianchi, F.: Atmospheric organic vapors in two European pine forests measured by a Vocus PTR-TOF: insights into monoterpene and sesquiterpene oxidation processes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 4123–4147, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-4123-2021, 2021.

Li, K., Jacob, D. J., Liao, H., Shen, L., Zhang, Q., and Bates, K. H.: Anthropogenic drivers of 2013–2017 trends in summer surface ozone in China, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 422–427, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812168116, 2019b.

Li, K., Jacob, D. J., Shen, L., Lu, X., De Smedt, I., and Liao, H.: Increases in surface ozone pollution in China from 2013 to 2019: anthropogenic and meteorological influences, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 11423–11433, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-11423-2020, 2020.

Li, K., Chen, L., Ying, F., White, S. J., Jang, C., Wu, X., Gao, X., Hong, S., Shen, J., Azzi, M., and Cen, K.: Meteorological and chemical impacts on ozone formation: A case study in Hangzhou, China, Atmospheric Research, 196, 40–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2017.06.003, 2017.

Li, L., Xie, S., Zeng, L., Wu, R., and Li, J.: Characteristics of volatile organic compounds and their role in ground-level ozone formation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China, Atmos. Environ., 113, 247–254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.05.021, 2015.

Li, X., Rohrer, F., Brauers, T., Hofzumahaus, A., Lu, K., Shao, M., Zhang, Y. H., and Wahner, A.: Modeling of HCHO and CHOCHO at a semi-rural site in southern China during the PRIDE-PRD2006 campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 12291–12305, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-12291-2014, 2014.

Lin, H., Wang, M., Duan, Y., Fu, Q., Ji, W., Cui, H., Jin, D., Lin, Y., and Hu, K.: O3 Sensitivity and Contributions of Different NMHC Sources in O3 Formation at Urban and Suburban Sites in Shanghai, Atmosphere-Basel, 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11030295, 2020.

Liu, X., Lyu, X., Wang, Y., Jiang, F., and Guo, H.: Intercomparison of O3 formation and radical chemistry in the past decade at a suburban site in Hong Kong, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 5127–5145, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-5127-2019, 2019.

Liu, X., Wang, N., Lyu, X., Zeren, Y., Jiang, F., Wang, X., Zou, S., Ling, Z., and Guo, H.: Photochemistry of ozone pollution in autumn in Pearl River Estuary, South China, Sci. Total Environ., 754, 141812, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141812, 2021.

Liu, Y., Qiu, P., Li, C., Li, X., Ma, W., Yin, S., Yu, Q., Li, J., and Liu, X.: Evolution and variations of atmospheric VOCs and O3 photochemistry during a summer O3 event in a county-level city, Southern China, Atmos. Environ., 272, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2022.118942, 2022.

Lu, H., Cai, Q. Y., Wen, S., Chi, Y., Guo, S., Sheng, G., and Fu, J.: Seasonal and diurnal variations of carbonyl compounds in the urban atmosphere of Guangzhou, China, Sci. Total Environ., 408, 3523–3529, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.05.013, 2010.

Lyu, X., Guo, H., Zou, Q., Li, K., Xiong, E., Zhou, B., Guo, P., Jiang, F., and Tian, X.: Evidence for Reducing Volatile Organic Compounds to Improve Air Quality from Concurrent Observations and In Situ Simulations at 10 Stations in Eastern China, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 15356–15364, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c04340, 2022.

Ma, X., Tan, Z., Lu, K., Yang, X., Liu, Y., Li, S., Li, X., Chen, S., Novelli, A., Cho, C., Zeng, L., Wahner, A., and Zhang, Y.: Winter photochemistry in Beijing: Observation and model simulation of OH and HO2 radicals at an urban site, Sci. Total Environ., 685, 85–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.329, 2019.

Mellouki, A., Bras, G. L., and Sidebottom, H.: Kinetics and Mechanisms of the Oxidation of Oxygenated Organic Compounds in the Gas Phase, Chem. Rev., 103, 5077–5096, 2003.

Mills, G., Pleijel, H., Malley, C. S., Sinha, B., Cooper, O. R., Schultz, M. G., Neufeld, H. S., Simpson, D., Sharps, K., Feng, Z., Gerosa, G., Harmens, H., Kobayashi, K., Saxena, P., Paoletti, E., Sinha, V., and Xu, X.: Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Present-day tropospheric ozone distribution and trends relevant to vegetation, Elem. Sci. Anth., 6, 47, https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.302, 2018.

Mo, Z., Shao, M., and Lu, S.: Compilation of a source profile database for hydrocarbon and OVOC emissions in China, Atmos. Environ., 143, 209–217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.08.025, 2016.

Rohrer, F., Lu, K., Hofzumahaus, A., Bohn, B., Brauers, T., Chang, C.-C., Fuchs, H., Häseler, R., Holland, F., Hu, M., Kita, K., Kondo, Y., Li, X., Lou, S., Oebel, A., Shao, M., Zeng, L., Zhu, T., Zhang, Y., and Wahner, A.: Maximum efficiency in the hydroxyl-radical-based self-cleansing of the troposphere, Nature Geoscience, 7, 559–563, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2199, 2014.

Sekimoto, K., Li, S.-M., Yuan, B., Koss, A., Coggon, M., Warneke, C., and de Gouw, J.: Calculation of the sensitivity of proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) for organic trace gases using molecular properties, International Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 421, 71–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2017.04.006, 2017.

Shen, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, M., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Yang, J., Jiang, Y., Chen, T., Chen, M., Huang, X., Li, C., Guo, D., Sun, X., Xue, L., and Wang, W.: Significance of carbonyl compounds to photochemical ozone formation in a coastal city (Shantou) in eastern China, Sci. Total Environ., 764, 144031, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144031, 2021.

Sun, H., Gu, D., Feng, X., Wang, Z., Cao, X., Sun, M., Ning, Z., Zheng, P., Mai, Y., Xu, Z., Chan, W. M., Li, X., Zhang, W., Lee, H. W., Leung, K. F., Yu, J. Z., Lee, E., Louie, P. K. K., and Leung, K.: Cruise observation of ambient volatile organic compounds over Hong Kong coastal water, Atmos. Environ., 323, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120387, 2024.

Tan, Z., Lu, K., Jiang, M., Su, R., Dong, H., Zeng, L., Xie, S., Tan, Q., and Zhang, Y.: Exploring ozone pollution in Chengdu, southwestern China: A case study from radical chemistry to O3–VOC–NOx sensitivity, Sci. Total Environ., 636, 775–786, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.286, 2018.

Tan, Z., Lu, K., Jiang, M., Su, R., Wang, H., Lou, S., Fu, Q., Zhai, C., Tan, Q., Yue, D., Chen, D., Wang, Z., Xie, S., Zeng, L., and Zhang, Y.: Daytime atmospheric oxidation capacity in four Chinese megacities during the photochemically polluted season: a case study based on box model simulation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 3493–3513, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-3493-2019, 2019a.

Tan, Z., Lu, K., Hofzumahaus, A., Fuchs, H., Bohn, B., Holland, F., Liu, Y., Rohrer, F., Shao, M., Sun, K., Wu, Y., Zeng, L., Zhang, Y., Zou, Q., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Wahner, A., and Zhang, Y.: Experimental budgets of OH, HO2, and RO2 radicals and implications for ozone formation in the Pearl River Delta in China 2014, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 7129–7150, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-7129-2019, 2019b.

Wang, H., Lyu, X., Guo, H., Wang, Y., Zou, S., Ling, Z., Wang, X., Jiang, F., Zeren, Y., Pan, W., Huang, X., and Shen, J.: Ozone pollution around a coastal region of South China Sea: interaction between marine and continental air, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 4277–4295, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-4277-2018, 2018a.

Wang, N., Guo, H., Jiang, F., Ling, Z. H., and Wang, T.: Simulation of ozone formation at different elevations in mountainous area of Hong Kong using WRF-CMAQ model, Sci. Total Environ., 505, 939–951, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.070, 2015.

Wang, R., Wang, L., Yang, Y., Zhan, J., Ji, D., Hu, B., Ling, Z., Xue, M., Zhao, S., Yao, D., Liu, Y., and Wang, Y.: Comparative analysis for the impacts of VOC subgroups and atmospheric oxidation capacity on O3 based on different observation-based methods at a suburban site in the North China Plain, Environ Res, 248, 118250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.118250, 2024.

Wang, W., Yuan, B., Peng, Y., Su, H., Cheng, Y., Yang, S., Wu, C., Qi, J., Bao, F., Huangfu, Y., Wang, C., Ye, C., Wang, Z., Wang, B., Wang, X., Song, W., Hu, W., Cheng, P., Zhu, M., Zheng, J., and Shao, M.: Direct observations indicate photodegradable oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) as larger contributors to radicals and ozone production in the atmosphere, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 4117–4128, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-4117-2022, 2022a.

Wang, X., Yin, S., Zhang, R., Yuan, M., and Ying, Q.: Assessment of summertime O3 formation and the O3-NOX-VOC sensitivity in Zhengzhou, China using an observation-based model, Sci. Total Environ., 813, 152449, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152449, 2022b.

Wang, Y., Guo, H., Zou, S., Lyu, X., Ling, Z., Cheng, H., and Zeren, Y.: Surface O3 photochemistry over the South China Sea: Application of a near-explicit chemical mechanism box model, Environ. Pollut., 234, 155–166, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.001, 2018b.

Wang, Y., Wang, H., Guo, H., Lyu, X., Cheng, H., Ling, Z., Louie, P. K. K., Simpson, I. J., Meinardi, S., and Blake, D. R.: Long-term O3–precursor relationships in Hong Kong: field observation and model simulation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 10919–10935, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-10919-2017, 2017.

Wang, Z.: Oxygenated volatile organic compounds measured at HKUST, DataSpace@HKUST [data set], https://doi.org/10.14711/dataset/ZV6FMX, 2025.

Whalley, L. K., Stone, D., Dunmore, R., Hamilton, J., Hopkins, J. R., Lee, J. D., Lewis, A. C., Williams, P., Kleffmann, J., Laufs, S., Woodward-Massey, R., and Heard, D. E.: Understanding in situ ozone production in the summertime through radical observations and modelling studies during the Clean air for London project (ClearfLo), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 2547–2571, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-2547-2018, 2018.

Whalley, L. K., Slater, E. J., Woodward-Massey, R., Ye, C., Lee, J. D., Squires, F., Hopkins, J. R., Dunmore, R. E., Shaw, M., Hamilton, J. F., Lewis, A. C., Mehra, A., Worrall, S. D., Bacak, A., Bannan, T. J., Coe, H., Percival, C. J., Ouyang, B., Jones, R. L., Crilley, L. R., Kramer, L. J., Bloss, W. J., Vu, T., Kotthaus, S., Grimmond, S., Sun, Y., Xu, W., Yue, S., Ren, L., Acton, W. J. F., Hewitt, C. N., Wang, X., Fu, P., and Heard, D. E.: Evaluating the sensitivity of radical chemistry and ozone formation to ambient VOCs and NOx in Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 2125–2147, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-2125-2021, 2021.

Wolfe, G. M., Marvin, M. R., Roberts, S. J., Travis, K. R., and Liao, J.: The Framework for 0-D Atmospheric Modeling (F0AM) v3.1, Geosci. Model Dev., 9, 3309–3319, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-3309-2016, 2016.

Wu, C., Wang, C., Wang, S., Wang, W., Yuan, B., Qi, J., Wang, B., Wang, H., Wang, C., Song, W., Wang, X., Hu, W., Lou, S., Ye, C., Peng, Y., Wang, Z., Huangfu, Y., Xie, Y., Zhu, M., Zheng, J., Wang, X., Jiang, B., Zhang, Z., and Shao, M.: Measurement report: Important contributions of oxygenated compounds to emissions and chemistry of volatile organic compounds in urban air, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 14769–14785, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-14769-2020, 2020.

Xu, C., He, X., Sun, S., Bo, Y., Cui, Z., Zhang, Z., and Dong, H.: Sensitivity of Ozone Formation in Summer in Jinan Using Observation-Based Model, Atmosphere-Basel, 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13122024, 2022.

Xue, L., Gu, R., Wang, T., Wang, X., Saunders, S., Blake, D., Louie, P. K. K., Luk, C. W. Y., Simpson, I., Xu, Z., Wang, Z., Gao, Y., Lee, S., Mellouki, A., and Wang, W.: Oxidative capacity and radical chemistry in the polluted atmosphere of Hong Kong and Pearl River Delta region: analysis of a severe photochemical smog episode, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 9891–9903, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-9891-2016, 2016.

Yang, X., Feng, X., Chen, Y., Zheng, P., Hui, L., Chen, Y., Yu, J. Z., and Wang, Z.: Development of an enhanced method for atmospheric carbonyls and characterizing their roles in photochemistry in subtropical Hong Kong, Sci. Total Environ., 165135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165135, 2023.

Yang, X., Xue, L., Wang, T., Wang, X., Gao, J., Lee, S., Blake, D. R., Chai, F., and Wang, W.: Observations and Explicit Modeling of Summertime Carbonyl Formation in Beijing: Identification of Key Precursor Species and Their Impact on Atmospheric Oxidation Chemistry, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 123, 1426–1440, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017jd027403, 2018.

Yang, X., Xue, L., Yao, L., Li, Q., Wen, L., Zhu, Y., Chen, T., Wang, X., Yang, L., Wang, T., Lee, S., Chen, J., and Wang, W.: Carbonyl compounds at Mount Tai in the North China Plain: Characteristics, sources, and effects on ozone formation, Atmospheric Research, 196, 53–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2017.06.005, 2017.

Yang, Y., Ji, D., Sun, J., Wang, Y., Yao, D., Zhao, S., Yu, X., Zeng, L., Zhang, R., Zhang, H., Wang, Y., and Wang, Y.: Ambient volatile organic compounds in a suburban site between Beijing and Tianjin: Concentration levels, source apportionment and health risk assessment, Sci. Total Environ., 695, 133889, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133889, 2019.

Yu, D., Tan, Z., Lu, K., Ma, X., Li, X., Chen, S., Zhu, B., Lin, L., Li, Y., Qiu, P., Yang, X., Liu, Y., Wang, H., He, L., Huang, X., and Zhang, Y.: An explicit study of local ozone budget and NOx–VOCs sensitivity in Shenzhen China, Atmos. Environ., 224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117304, 2020.

Yuan, B., Koss, A. R., Warneke, C., Coggon, M., Sekimoto, K., and de Gouw, J. A.: Proton-Transfer-Reaction Mass Spectrometry: Applications in Atmospheric Sciences, Chem. Rev., 117, 13187–13229, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00325, 2017.

Yue, X. and Unger, N.: Ozone vegetation damage effects on gross primary productivity in the United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 9137–9153, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-9137-2014, 2014.

Zhang, J., Wang, T., Chameides, W. L., Cardelino, C., Kwok, J., Blake, D. R., Ding, A., and So, K. L.: Ozone production and hydrocarbon reactivity in Hong Kong, Southern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 557–573, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-557-2007, 2007.

Zhang, Y., Dai, W., Li, J., Ho, S. S. H., Li, L., Shen, M., Wang, Q., and Cao, J.: Comprehensive observations of carbonyls of Mt. Hua in Central China: Vertical distribution and effects on ozone formation, Sci. Total Environ., 907, 167983, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167983, 2024.

Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Li, C., Li, Y., Yin, S., Claflin, M. S., Lerner, B. M., Worsnop, D., and Wang, L.: Interpretation of mass spectra by a Vocus proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-MS) at an urban site: insights from gas chromatographic pre-separation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 18, 3547–3568, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-18-3547-2025, 2025.

Zhang, Y. H., Su, H., Zhong, L. J., Cheng, Y. F., Zeng, L. M., Wang, X. S., Xiang, Y. R., Wang, J. L., Gao, D. F., and Shao, M.: Regional ozone pollution and observation-based approach for analyzing ozone–precursor relationship during the PRIDE-PRD2004 campaign, Atmos. Environ., 42, 6203–6218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.05.002, 2008.

Zhang, Z., Man, H., Duan, F., Lv, Z., Zheng, S., Zhao, J., Huang, F., Luo, Z., He, K., and Liu, H.: Evaluation of the VOC pollution pattern and emission characteristics during the Beijing resurgence of COVID-19 in summer 2020 based on the measurement of PTR-ToF-MS, Environ. Res. Lett., 17, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac3e99, 2022.

Zhao, M., Zhang, Y., Pei, C., Chen, T., Mu, J., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, W., and Xue, L.: Worsening ozone air pollution with reduced NOx and VOCs in the Pearl River Delta region in autumn 2019: Implications for national control policy in China, J. Environ. Manage., 324, 116327, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116327, 2022.

Zhao, Y., Chen, L., Li, K., Han, L., Zhang, X., Wu, X., Gao, X., Azzi, M., and Cen, K.: Atmospheric ozone chemistry and control strategies in Hangzhou, China: Application of a 0-D box model, Atmospheric Research, 246, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2020.105109, 2020.

Zhou, X., Li, Z. Q., Zhang, T. J., Wang, F., Wang, F. T., Tao, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, F. L., and Huang, J.: Volatile organic compounds in a typical petrochemical industrialized valley city of northwest China based on high-resolution PTR-MS measurements: Characterization, sources and chemical effects, Sci. Total Environ., 671, 883–896, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.283, 2019.