the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Abundance of volatile organic compounds and their role in ozone pollution management: evidence from multi-platform observations and model representation during the 2021–2022 field campaign in Hong Kong

Xueying Liu

Yeqi Huang

Yao Chen

Xin Feng

Jiading Li

Yang Xu

Hao Sun

Zhi Ning

Jianzhen Yu

Wing Sze Chow

Changqing Lin

Yan Xiang

Tianshu Zhang

Claire Granier

Guy Brasseur

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a diverse group of species that contribute to ozone formation. However, our understanding of VOC dynamics and their effect on ozone pollution is limited by the lack of long-term, continuous, and speciated measurements, especially of oxygenated compounds. To address this gap, this study integrates on-land, shipborne, and spaceborne measurements from a field campaign in Hong Kong during 2021–2022, analyzing 45–98 VOC species over land and water. Results show that oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) account for 73 % (37 ppbv) of the total VOC concentration and 56 % of the total ozone formation potential (OFP), underscoring their indispensable role in VOC chemistry. Despite such importance, OVOCs are underestimated by 45 %–70 % in the CMAQ model, while non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHCs) face a lesser underestimation of 47 %–48 % (i.e., “model underestimation”). Meanwhile, the model does not currently account for 17–56 species of the total measured VOCs (i.e., “model omission”). According to this, we break down the observed overwater VOC concentration of 51 ppbv into three components: 9 ppbv (18 %) successfully represented, 35 ppbv (69 %) underestimated, and 7 ppbv (14 %) omitted in the model. For OFP, the breakdown shows 26 % successful representation, 54 % underestimation, and 20 % omission. Together, both “omission” and “underestimation” reveal the overall “VOC underrepresentation” in the model, which partly results in greater ozone sensitivity to VOCs than observed by spaceborne TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) in polluted areas. The findings provide valuable insights into regional pollution dynamics, and inform VOC-related model development and air quality management.

- Article

(9966 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(11449 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the atmosphere represent a diverse group of gaseous organic trace substances. This extensive family includes non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHCs) such as alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, and aromatics, as well as oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) like aldehydes, alcohols, ketones, ethers, and organic peroxides, classified based on their molecular structures. VOCs are emitted from various anthropogenic and biogenic sources (Li et al., 2014; Guenther et al., 2012) and can also be produced through secondary atmospheric processes. In the ambient air, NMHCs can be oxidized to OVOCs, a process that often predominates the levels of OVOCs in many regions of China and globally (Chen et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2022). Once emitted or formed, VOCs are subject to photolysis by near-ultraviolet radiation, generating atmospheric radicals, or to oxidation by various oxidants including hydroxyl radicals (•OH), nitrate radicals (NO3•), and ozone (O3), resulting in the formation of secondary peroxyl radicals (ROx). These processes are essential for atmospheric radical recycling and play a significant role to ozone and secondary organic aerosol formation (W. Wang et al., 2022a, 2024a; Whalley et al., 2021).

Surface ozone, produced through photochemical reactions involving VOCs and nitrogen oxides (NOx), poses risks to human health and ecosystem productivity. Between 2013 and 2019, surface ozone levels increased in several metropolitan regions of China. Although levels seemed to slightly decline around 2019 in areas such as the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH), Yangtze River Delta (YRD), and Sichuan Basin (SCB), ozone levels in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) have continued to rise in recent years (Feng et al., 2023; Y. Wang et al., 2023a; W. Wang et al., 2022b, 2024a). Ozone formation in these metropolitan urban clusters is found to be particularly sensitive to VOCs (Y. Wang et al., 2023a; T. Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, understanding VOC abundance and its role in regulating ozone is crucial in urban areas nationwide, especially in the PRD where both ozone and VOC levels have shown an upward trend (Y. Wang et al., 2023a; Feng et al., 2023).

Current VOCs representation in chemical transport models remains largely suboptimal for several reasons. First, producing VOC emission inventories is more challenging than for NOx due to the larger number of compounds involved and the uncertain source profiles (Li et al., 2014; Mo et al., 2016). Volatile chemical product (VCP) emissions, which have gained increasing attention in urban areas, have only recently been incorporated into emissions inventory development (Coggon et al., 2021; Seltzer et al., 2021; S. Wang et al., 2024). To date, VOC emission inventories have performed poorly against observations on a global scale (von Schneidemesser et al., 2023; Rowlinson et al., 2024; Beaudry et al., 2025). Meanwhile, the complex chemistry of VOCs poses significant challenges for model representation, and efforts are underway to improve their parameterization through new chemical mechanisms and coefficients (Travis et al., 2024; Bates et al., 2024; Bates et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2024). Mostly importantly, unlike criteria pollutants (i.e., PM10, PM2.5, ozone, NO2, SO2, and CO) that are routinely monitored, only a limited number of VOC species are measured at a small number of sites or for episodic short durations both in China and globally (Zhang et al., 2025; She et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2024; von Schneidemesser et al., 2023). The lack of consistent, continuous measurements for many VOC species, particularly OVOCs, hinders comprehensive VOC-related model evaluation and improvement. This limitation impacts the assessment of ozone formation sensitivity to VOCs and the formulation of emission reduction strategies for ozone pollution management. Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand the extent to which VOCs are represented in models, and how this representation affects the simulation of the ozone-precursor relationship.

Knowledge gaps remain in previous studies assessing the ability of chemical transport models to reproduce the ambient abundance of VOCs. First, the scarcity of OVOC measurements has led earlier research to focus primarily on NMHCs, with only a limited number of OVOCs investigated (von Schneidemesser et al., 2023; Rowlinson et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2024). This results in a gap in understanding the model representation of OVOCs, which is becoming increasingly important as future emissions shift toward greater OVOC levels due to rising solvent use and consumer products (S. Wang et al., 2024; Y. Wang et al., 2024; Coggon et al., 2021; Karl et al., 2018). Secondly, many studies report direct comparison between equivalent VOC species between observations and models (Zhang et al., 2025; She et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2024). However, models often simulate only a subset of the total measured VOCs. The missing VOC reactivity in models versus measurements can be partly attributed to these omitted species (W. Wang et al., 2024b). Yet, the extent of this omission remains largely unreported in previous studies, highlighting a gap in quantifying the overall model representation of ambient VOC abundance and their reactivity.

To address these gaps, this study integrated field observations, from a joint field campaign conducted by the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department (HKEPD) and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) during 2021–2022, with spaceborne TROPOMI data to: (1) analyze the temporal and spatial characteristics of ozone and its precursors, with a particular focus on speciated VOCs, (2) quantify VOC representation in the CMAQ chemical transport model, and (3) assess the impact of such VOC representation on the simulated ozone formation sensitivity. This study represents the first attempt to integrate multi-source observations from on-land, shipborne, and spaceborne platforms with chemical transport modeling to examine VOC and ozone pollution in the PRD region of South China. The findings provide valuable insights into the regional VOC and ozone pollution dynamics, while highlighting deficiencies in model VOC representation that are crucial for advancing VOC-related model development and air quality management.

2.1 Surface measurements

The HKEPD–HKUST joint field campaign produced a comprehensive suite of surface measurements, including year-round continuous land-based monitoring (Mai et al., 2025; Ou et al., 2015) and the first shipborne mobile air quality observations over Hong Kong waters (Sun et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2023). A wide range of VOC species was measured, with 45 species (16 oxygenated) on land and 98 species (35 oxygenated) over water.

2.1.1 Land-based monitoring

The HKEPD operates a routine monitoring network of 18 land-based Air Quality Monitoring Stations (AQMS), which include 14 general stations, 1 background station and 3 roadside stations, broadly distributed over the Hong Kong region (Fig. S1). Additionally, the Cape D'Aguilar Supersite (CDSS), a coastal background site located at Hok Tsui in the southeastern of Hong Kong Island, equipped with surface VOC measurements and ozone lidar, is also included in the AQMS network to represent land-based monitoring in this study.

While ozone and NOx were monitored across AQMS sites, VOC measurements were only available at three sites (i.e., general site Tung Chung, background site Hok Tsui, and roadside site Mong Kok; Fig. S1). The study used measurements from 2021 to 2022, using the following respective measurement instruments. First, we use hourly NO, NO2, and ozone from the AQMS measured by various gas analyzers (Feng et al., 2023). For stations with online VOC measurements, ambient air samples were collected and analyzed every 30 min for the target 29 NMHC species (see Table 1) using an online gas chromatography (GC)-photo ionization detector (PID)/flame ion detector (FID) system (Syntech Spectras GC955 series 611/811), and then the half-hour concentrations were integrated into hourly average for analysis (Mai et al., 2025; Ou et al., 2015). In addition, daily OVOC samples were collected using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (2,4-DNPH) cartridges every 2–7 d as arranged by HKEPD, and subsequently analyzed for sixteen OVOCs species (see Table 1) using a high-performance liquid chromatography with ultra-violet spectroscopy (HPLC-UV). To capture the day-to-day variation of total observed VOCs discussed in Sect. 3.2, we first identified dates with both NMHC and OVOC measurements; for each of these days, we averaged the hourly NMHC values to obtain a daily mean and combined this with the daily OVOC value to calculate the total daily concentration of all measured VOCs.

To compare with spaceborne TROPOMI in Sect. 5, we made use of a regional gridded sampling at 40 sites in the PRD region on 4–5 September 2022, to provide a snapshot of ground-based formaldehyde (HCHO) levels. To ensure representativeness of the PRD regional conditions, the area was mapped into a 200 km × 200 km domain, divided into 100 grid cells of 20 km × 20 km each; measurement sites were scattered within these grid cells and located at least 50 m away from local pollution sources to capture well-mixed air within each grid cell (Mo et al., 2023). Air samples were collected into 2,4-DNPH cartridges and subsequently analyzed with an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with a triple quadrupole ESI mass spectrometer (UHPLC-MS). At each site, two HCHO samples were collected: one in the morning (06:00–10:00) and the other in the afternoon (12:00–16:00). For the comparison with spaceborne TROPOMI in Sect. 5, we selected only the afternoon samples to align as closely as possible with the satellite's overpass time at 13:30 local time. For each HCHO sampling site, we matched the corresponding afternoon mean NO2 from the nearest station of the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC) during the same period (12:00–16:00) to calculate the surface HCHO-to-NO2 ratio for comparison with spaceborne ratio.

2.1.2 Shipborne measurements

Shipborne measurement cruises were conducted in Hong Kong coastal waters in different seasons during 2021–2022, including spring (22–23 February and 23 April in 2021), summer (23 July and 27 July in 2021) and fall (17 September in 2021, and 4–5 September and 13–14 November in 2022). During these cruises, a highly integrated portable air station, i.e., MAS-AF300 (Sapiens), was developed to measure trace gases (including NO, NO2, and ozone) at 1 min resolution (Che et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2016). To detect NMHCs, whole air canister samples were collected using 2 L electropolished stainless-steel canisters and analyzed with a GC-mass selective detector (MSD)/electron capture detector (ECD)/FID system, which detected 63 NMHCs (see Table 1; Sun et al., 2024). These NMHCs were sampled hourly at a single point (i.e., point sampling), providing instantaneous concentration measurements. Additionally, OVOC samples were collected using Sep-Pak silica cartridge coated with acidified 2,4-DNPH (Waters, USA) and then analyzed by an UHPLC-MS. This method detected 35 OVOCs above the detection limit (see Table 1; Xu et al., 2023). Those VOC samples were collected over a one-hour period (i.e., integrative sampling) and reported as hourly averages.

In summary, different sampling and analytical methods are used to obtain VOC measurements. Both land and ship measurements used offline techniques for OVOCs; however, the UHPLC-MS employed in shipborne measurements can detect a broader range of OVOCs than the HPLC-UV used at land-based HKEPD sites (Table 1). Different OVOC measurement techniques can introduce uncertainties (Cui et al., 2016; Wisthaler et al., 2008). Additionally, the offline GC-MSD/ECD/FID used in shipborne measurements also identified more NMHCs than the online GC-PID/FID used at land-based HKEPD sites. Quantifying intra-instrumental differences for the same species at the same location and time poses practical challenges. Readers should be aware of the uncertainties related to these differences. The observational datasets used in this study are sourced from peer-reviewed publications that underwent a thorough quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) process; readers interested in detailed QA/QC methodologies are recommended to refer to the Supplement Text or the original publications listed above.

2.1.3 Ozone formation potential

The ozone formation potential (OFP) scale has been extensively used to quantify the relative effects of individual VOCs on ozone formation. We calculated OFP using the following formula,

where [VOC]i is the concentration of ith VOCs (µg m−3). MIRi is the maximum incremental reactivity of ith VOCs (g ozone g−1 VOC) that quantifies how much additional ozone can be produced from incremental increases of that specific VOC in the atmosphere. Some VOCs (e.g., formaldehyde and acetaldehyde) are major contributors to •OH reactivity and ozone formation, while some (e.g., benzaldehyde) contribute minimally to •OH removal and inhibit ozone formation (Zhang et al., 2019). Their contributions to ozone are represented by their respective MIR values, as obtained from Carter (2010).

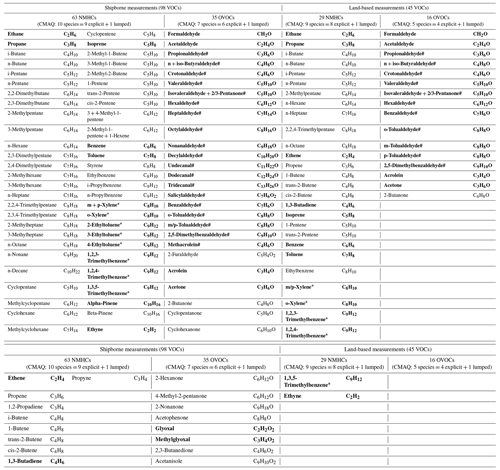

Table 1List of measured NMHCs and OVOCs on shipborne and land-based platforms. Species present in the CMAQ model are highlighted in bold. Subscripts indicate two lumped species in the model: * for XYLMN (xylene and other polyalkyl aromatics except naphthalene) and # for ALDX (aldehydes with 3 or more carbons). Other species in bold are explicitly represented in the model.

2.2 Satellite measurements: S5P TROPOMI

The TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) is a nadir-viewing spectrometer onboard the Sentinel-5P (S5P) satellite, which was launched on 13 October 2017. It operates in sun-synchronous, low-Earth (825 km) orbits, with an Equator overpass at approximately 13:30 local solar time (Veefkind et al., 2012). TROPOMI measures column amounts of several trace gases in the ultraviolet-visible-near-infrared (UV-VIS-NIR; e.g., NO2 and HCHO) and shortwave infrared (SWIR; e.g., CO) spectral regions. TROPOMI has a horizontal swath of 2600 km that is divided into 450 across-track rows. The spatial resolution of TROPOMI at nadir is 3.5 km × 7 km (across-track × along-track) for NO2 and HCHO, which was later refined to 3.5 km × 5.5 km in August 2019 due to an adjustment to the along-track integration time. This study used TROPOMI Product Algorithm Laboratory (PAL) tropospheric vertical column densities (VCDs) for a consistent reprocessed data product over 2021–2022 at ∼ 2 km × 2 km resolution (Eskes et al., 2021). For quality assurance, only observations with the overall quality flag (qa_value) >0.75 and retrieved cloud fraction (cloud_fraction) <0.3 were used. The tropospheric HCHO and NO2 columns can serve as proxies for VOCs and NOx, respectively, and thus their ratio (HCHO-to-NO2) indicates ozone formation sensitivity to changes in VOCs and NOx (Jin et al., 2017; Goldberg et al., 2022); further details can be found in Sect. 3.2.

2.3 The CMAQ model

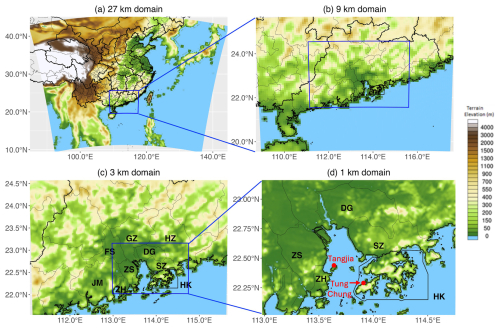

The Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) modeling system is a three-dimensional Eulerian atmospheric chemistry and transport model that simulates atmospheric composition throughout the troposphere. Four domains were set up with different horizontal resolutions at 27, 9, 3, and 1 km (Fig. 1). The model employed a terrain-following coordinate system with 38 vertical layers extending from the surface to the 50 hPa pressure level (approximately 23 km height). Chemical boundary and initial conditions for the outmost domain were generated from the seasonal average hemispheric CMAQ outputs archived on its official website. Science configuration options include the CB6r3 gas-phase chemistry (Luecken et al., 2019), the AERO7 aerosol module (Appel et al., 2021), and the M3Dry dry deposition scheme. The anthropogenic emissions used are the HKEPD emission inventory scaled to 2019 for HK region and scaled to 2021 for the PRD region, the high-resolution INTegrated emission inventory of Air pollutants for China (INTAC) scaled to 2019 for the rest of China, and the 2018 Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) for regions outside of China. Biogenic emissions are from the Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) v3.1.

The meteorological inputs to drive CMAQ were from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model. Meteorological boundary and initial conditions were the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Final Analysis data at 0.25° × 0.25°. Land surface data (e.g., land use, vegetation type, terrain elevation, etc.) were obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) terrain databases, overwritten by the 2003 land use data over the PRD region from the Planning Department of the Hong Kong Government. WRF physics schemes include Asymmetric Convective Model v2 (ACM2) for the planetary boundary layer physics, the Unified Noah Land Surface Model (Noah-LSM) for the land surface, single-moment 3-class scheme for cloud microphysics, the rapid radiative transfer model (RRTM) for longwave and shortwave radiation processes, and the Kain–Fritsch scheme for cumulus convections.

Figure 1Model domains with terrain elevation. Abbreviated city names are inserted, include Hong Kong (HK), Shenzhen (SZ), Dongguan (DG), Huizhou (HZ), Guangzhou (GZ), Foshan (FS), Zhongshan (ZS), Jiangmen (JM), and Zhuhai (ZH).

To compare model simulations with satellite retrievals, we followed the method established in previous studies (Douros et al., 2023; Goldberg et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2020). First, model simulated profiles were sampled at the TROPOMI overpassing time and location. We then interpolated model profiles to the vertical levels of satellite retrievals. For consistency between TROPOMI and model simulated vertical profiles, we also applied scene-dependent averaging kernels that describe the instrument vertical sensitivity to changes in a trace gas and replaced a priori information from the TM5-MP model used in the standard retrieval. Finally, we integrated from the surface up to the tropopause to calculate column values. Here, we opted to use model simulations at 3 km resolution for comparison with TROPOMI products at 2 km resolution, as these represent the closest match in spatial resolution in our study. This choice also allows us to highlight the differences between urban and suburban areas in Fig. 10, which a 1 km model outputs would not adequately cover. Yet this choice may result in the loss of some fine-scale features simulated at 1 km resolution.

2.4 VOC comparisons between measurements and model

As described in Sect. 2.1, land-based instruments measure a total of 45 VOC species (including 29 NMHCs and 16 OVOCs), while shipborne instruments measure 98 species (including 63 NMHCs and 35 OVOCs). These species represent the ambient measurable VOC abundance, referred to as “total observed” species. However, state-of-the-art chemical transport models do not account for such a broad range of species. Instead, these models typically simulate key species that significantly impact atmospheric composition individually (i.e., explicit species), while grouping less critical species into a single representative species (i.e., lumped species) to simplify the modeling process and improve computational efficiency. For instance, among all measured species at land-based sites, only 13 NMHCs and 15 OVOCs (referred to as “selective observed” species) are represented in our CMAQ simulation by 9 NMHCs (8 explicit and 1 lumped species) and 5 OVOCs (4 explicit and 1 lumped species) (referred to as “modeled” species). Similarly, among the shipborne measured species, only 17 NMHCs and 25 OVOCs are represented in CMAQ by 10 NMHCs (9 explicit and 1 lumped species) and 7 OVOCs (6 explicit and 1 lumped species). See Table 1 for details. The differences between “total observed” and “selective observed” species reflect the abundance of species omitted by the model.

To evaluate the model's representation of VOCs, we conducted two types of observation–model comparisons. First, we performed an equivalent comparison between “modeled” and “selective observed” species to assess model bias in simulating the concentrations of VOC species that are common to both the observations and the model. This helps identify discrepancies in the model's ability to capture key species that significantly influence atmospheric chemistry, indicating either underestimation or overestimation. Second, we compared “modeled” to “total observed” species to evaluate the overall representativeness of the modeled VOCs in relation to the ambient measurable VOC abundance. This comparison provides insight into the model's ability to reflect the full range of VOCs present in the atmosphere. In all observation–model comparisons, we first identified the original resolution of each observation. Given that the model results have a minimum temporal resolution of hourly and lack sub-hour variability, we used hourly averaged model concentrations for observations at hourly resolution or finer. For daily observations, we averaged the corresponding hourly model outputs to obtain the modeled daily values.

3.1 Monthly variation

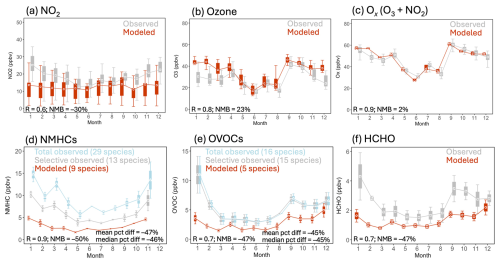

Land-based measurements provide continuous surface monitoring across all seasons, which is valuable for analyzing temporal variations in ozone and its precursors. Surface NO2 levels recorded at ground-based sites are higher in cold seasons than in warm seasons, with monthly differences relative to the annual mean ranging from −18 % in June–July–August (JJA) to +23 % in December–January–February (DJF) (Fig. 2a). This seasonal pattern of surface NO2 correlates well with the tropospheric VCDs of NO2 measured by the spaceborne TROPOMI (R=0.9; Fig. S2) and averaged over the Hong Kong domain (see domain coverage in Fig.10), which show monthly differences relative to the annual mean ranging from −20 % in JJA to +60 % in DJF. Comparing the observed surface NO2 with the CMAQ model (Fig. 2a), the model captures well the warm seasons but underestimates NO2 levels during the cold seasons, resulting in an overall underestimation (R=0.6; NMB = −30 %).

Figure 2Monthly variations of different species recorded at land-based AQMS sites over 2021–2022. Error bars indicate variability across non-roadside sites. Correlation coefficient (R) and normalized mean bias (NMB) between model (in red) and observations (in grey) are inserted.

Surface ozone in the subtropical coastal city of Hong Kong exhibits a bimodal pattern with a strong peak in autumn and a minor peak in spring (Fig. 2b), which is also visible in boundary layer ozone measurements recorded by the ozone lidar (Fig. S3). This bimodal pattern is different from that of the North China Plain, where ozone typically peaks in the summer months from May to July (W. Wang et al., 2022b). In Hong Kong, the spring peak consistently occurs in April for both the 2021–2022 average and the multi-decade average (2000–2023). Springtime ozone exceedances are often attributed to the long-range transport of air masses that are rich in ozone or its precursors from Southeast Asia (Wang et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2019; Chan et al., 2000). The autumn peak occurs in September for the 2021–2022 average, while the decadal average shows this peak in October. Late summer and autumn episodic events are typically characterized by high temperatures and stagnant conditions associated with a subtropical high or typhoon, which contribute to significant local ozone production (Lin et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2024; Ouyang et al., 2022). Comparing observations with the model, the model effectively captures the observed seasonal variation with some overestimation during cold months (R=0.8; NMB = 23 % in Fig. 2b). This overestimation is lower when comparing observed and modeled total oxidants (Ox) with improved metrics (R=0.9; NMB = 2 % in Fig. 2c).

Land-based sites measure a total of 45 VOC species, including 29 NMHCs and 16 OVOCs. We observed that the concentration of NMHCs is higher in colder months compared to warmer months (Fig. 2d), primarily driven by anthropogenic species (e.g., ethene, ethane, propane), despite higher levels of the biogenic species (e.g., isoprene) in warmer months (Fig. S4). Meanwhile, OVOCs show peaks in January and September (Fig. 2e). HCHO, the most abundant atmospheric carbonyl primarily resulting from the secondary oxidation of various VOCs, follows a similar peak pattern (Fig. 2f). We further examined spaceborne tropospheric columns specifically to identify trends, and found that the September peak is evident in both surface and column observations (Fig. S2), suggesting enhanced local secondary production from the oxidation of various VOCs, driven by Hong Kong's hot and sunny weather during this period. In contrast, the January peak is visible only at the surface but not in tropospheric columns. In general, we do not observe a strong correlation in monthly trends between column and surface HCHO; this column–surface decoupling is also noted in other locations particularly in coastal regions with intense land–sea interactions (Souri et al., 2023), similar to our study area. Overall, the model captures the observed seasonal variations in NMHCs (Fig. 2d; R=0.9; NMB = −50 %), OVOCs (Fig. 2e; R=0.7; NMB = −47 %), and HCHO (Fig. 2f; R=0.7; NMB = −47 %).

A strong relationship exists between HCHO and ozone, as indicated by a strong correlation (R=0.7; Fig. S5) between the observed monthly variability of the two. In comparison, total VOCs including both NMHCs and OVOCs, show only a modest correlation with ozone (R=0.4), as do OVOCs (R=0.3) and NMHCs (R=0.3). This strong HCHO–ozone relationship arises because HCHO and ozone are coproduced through the photochemical oxidation of VOCs. The model effectively captures the observed strong HCHO-ozone correlation (R=0.6).

3.2 HCHO as an indicator for ambient VOCs

Many studies use the HCHO-to-NO2 ratio (i.e., formaldehyde-to-NO2 ratio or FNR) to indicate ozone formation sensitivity through both surface in situ measurements (Tonnesen and Dennis, 2000; Liu et al., 2024) and spaceborne remote sensing (Jin et al., 2017; Goldberg et al., 2022; Acdan et al., 2023). However, the composition of VOCs varies significantly in different urban areas with specific emission profiles and in biogenic-dominated natural environments. Therefore, one concern with the FNR method is how representative HCHO is of ambient VOCs in different environments. To approach this question and validate our FNR analysis in Sect. 5, we now assess this relationship in three diverse environments (i.e., roadside, urban, and background) in Hong Kong.

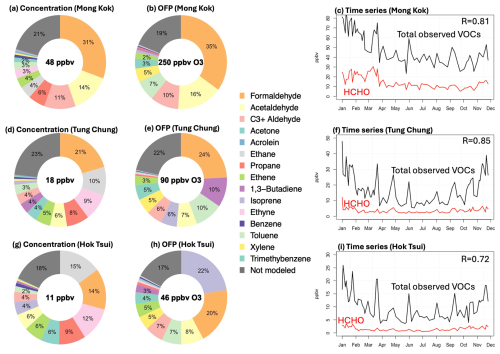

Figure 3Contribution of individual VOCs to (a, d, g) the concentration and (b, e, h) the ozone formation potential (OFP) of the total observed VOCs at three land-based sites in 2021. (c, f, i) Time series of HCHO and total observed VOCs with their correlation coefficient inserted.

First, we examine the relative contributions of HCHO to all measured VOCs at these land-based locations. Figure 3 shows that the contribution of HCHO to total VOC concentrations decreases from 31 % at roadside Mong Kok (Fig. 3a) to 21 % at urban Tung Chung (Fig. 3d) and further to 14 % at background Hok Tsui (Fig. 3g). Similarly, the contribution of HCHO to total OFP decreases from 35 % at Mong Kok (Fig. 3b) to 24 % at Tung Chung (Fig. 3e) and further to 20 % at Hok Tsui (Fig. 3h). It is worth noting that the measuring techniques used for land-based monitoring detect a smaller amount of VOC species compared to shipborne measurements (Table 1); the percentages attributed to HCHO may be smaller if different techniques capable of detecting more species were adopted. Taking a case study of the PRD region for example, we find that HCHO contributes to 15 %–30 % of the total measured VOC concentrations from ∼ 50 species; this percentage declines to 8 %–21 % when using another dataset that includes ∼ 80 species (Fig. S6). Notably, these percentage contributions in the PRD region are similar to those observed in Hong Kong, confirming the regional representativeness of HCHO's contribution. Overall, HCHO is the largest component of all measured VOCs at both Mong Kok and Tung Chung, indicating its key representativeness in polluted urban areas. At the background site Hok Tsui, HCHO is the second-largest contributor, accounting for 14 % of total concentrations and 20 % of OFP, which is slightly less than the contributions from the largest contributor, ethane for concentration and isoprene for OFP. It is worth noting that HCHO is a significant contributor to both VOC concentration and OFP due to its high levels and large MIR value (9.46 g O3 g−1 VOC), distinguishing it from other species that may either only show high concentrations or only contribute significantly to OFP, particularly at the Tung Chung and Hok Tsui sites. Finally, we examine the temporal correlation between HCHO and total measured VOCs and find strong correlations at all sites: R=0.81 at Mong Kok (Figs. 3c; S7), R=0.85 at Tung Chung (Figs. 3f; S7), and R=0.72 at Hok Tsui (Figs. 3i; S7). VOC species that are omitted by the model account for 14 %–17 % of the total observed concentrations and 16 %–19 % of their OFP across different environments.

The above analysis suggests that HCHO serves as a reliable indicator of ambient VOC environments due to (1) its key role in representing VOC levels and OFP and (2) its strong temporal correlations with the total measurable VOCs. However, its representativeness may vary, being more pronounced in polluted areas and less so in natural settings. For surface in situ measurements, which can effectively capture a diverse range of VOC species, a more comprehensive understanding of local VOC environments can be achieved through the analysis of multiple species. In the field of satellite remote sensing, HCHO is currently the most common operation grade VOC retrievals from many instruments and often used as a single indictor to represent overall VOC levels across different environments. Studies that use the FNR to identify ozone formation regimes tend to focus on urban areas with high NO2 levels (Jin et al., 2020), where HCHO is most representative of ambient VOCs. As more satellite VOC products become available, such as glyoxal (CHOCHO) (Lerot et al., 2021; Ha et al., 2024), isoprene (C5H8) (Wells et al., 2022), formic acid (HCOOH) (Stavrakou et al., 2012), and ethane (C2H6) (Brewer et al., 2024), the validity of using a multi-species representation of VOCs in various local conditions can be explored. This will aid in ozone air quality studies across different environments with varying emission profiles and local photochemistry.

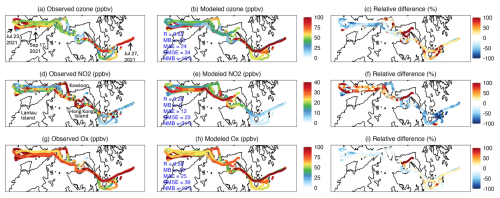

4.1 Spatial patterns

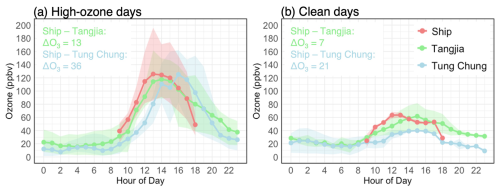

Ozone and its precursors are measured in coastal waters for the first time during mobile ship cruises in the PRD region. High ozone levels were observed over water on 23 July, 27 July, and 17 September in 2021, as well as on 4–5 September and 13 November in 2022 during the 10 d ship cruises (Fig. 4a). On high-ozone days, the maximum hourly mean ozone concentrations range from 91–196 ppbv, significantly higher than the 52–69 ppbv observed on clean days (Fig. S8). These elevated levels were detected likely because the ships were specifically tasked with measuring peak ozone episodes. Spatially, high ozone concentrations are generally found at the eastern and western ends of the cruises, while much lower levels at around 20 ppbv are recorded in the interchange between Kowloon Peninsula and Hong Kong Island due to the titration effect of high NOx levels along intensive shipping routes (Y. Wang et al., 2023b). We examine westward shipborne measurements into the Pearl River Estuary (PRE) and find that over-water ozone concentrations are typically 12 ppbv higher than the land-based Tangjia site on the west bank of the PRE and 32 ppbv higher than Tung Chung site on the east bank between 9 AM to 2 PM. This water-land gradient of ozone is more pronounced on high ozone days compared to clean days (Fig. 5). Our findings, based on actual over-water measurements into the PRE for the first time, confirm the PRE as an ozone reservoir simulated by Zeren et al. (2019).

Figure 4Mobile ship measurements of ozone (top), NO2 (middle) and Ox (bottom), along with their modeled equivalents. Percentage differences are given as (model–observation)/observation.

Figure 5Ozone diurnal variations recorded during westward ship cruises and at two land-based sites (Tangjia and Tung Chung; locations shown in Fig. 1). The mean water-land ozone gradient (ΔO3) is calculated as shipborne ozone minus land-based measurements from 9 AM to 2 PM.

For spatial pattern of NO2, low concentrations are observed on eastbound routes (Fig. 4d), which are generally upwind of Hong Kong and less affected by urban emissions. In contrast, high concentrations were detected on westbound routes that passed through busy transportation and shipping zones and reached the westernmost area of Hong Kong waters with influences by aged plumes from the urban emissions in the PRD region. This east-west gradient in NO2 is also observed in mobile vehicle measurements reported by Zhu et al. (2018). The model reasonably captures the overall observed east-west gradient, but tends to overestimate ozone and underestimate NO2 to the east of Hong Kong waters while exhibiting the opposite bias to the west (Fig. 4c, f). To reflect the model's ability to simulate atmospheric oxidative capacity without strong interreference from NOx titration effect, the oxidant level (Ox= O3+ NO2) is often used as a tracer of photochemical processes in high NOx environment, such as along major highways and shipping lanes during field campaigns (Li et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024). By comparing observed and modeled Ox, we find that the simulated Ox has low bias and a substantial positive correlation against observations (Fig. 4h), suggesting that the model effectively captures regional oxidative capacity.

As introduced in Sect. 2.1.2, NMHCs were collected via point sampling at a single timestamp within each hour, resulting in only a few isolated points being marked on the map for each daily measurement period. OVOCs, on the other hand, were measured using integrative sampling over the entire hour while the ship was in motion, resulting in no fixed latitude and longitude coordinates assigned to them. As a result, there is no comparable spatial distribution of VOCs to present here; instead, we directly compare their observation-model differences in Sect. 4.2.

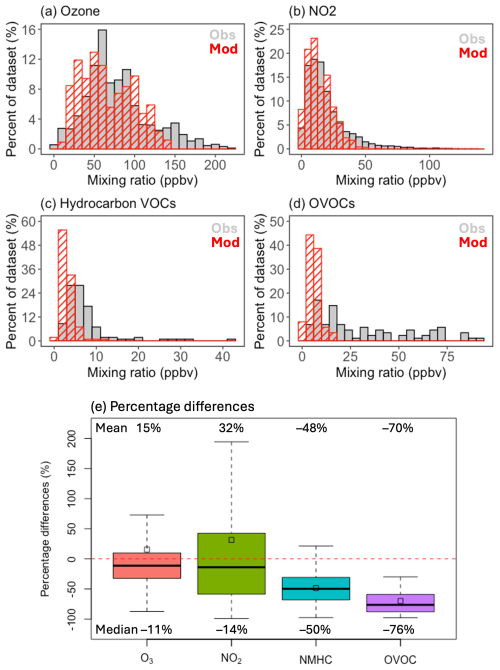

4.2 Underrepresented VOCs in the model

Using shipborne measurements, two types of observation–model comparisons were conducted for VOCs, as described in Sect. 2.4. The first type compares equivalent VOC species common to both observations and the model in Fig. 6. We found that the model struggles to simulate medium to high concentrations and thus a majority of the values cluster at low mixing ratios for both NMHCs (Fig. 6c) and OVOCs (Fig. 6d). Notably, the model underestimates equivalent OVOCs by 76 % and NMHCs by 50 %, significantly larger than that of ozone (−11 %) and NO2 (−14 %) based on the medians of their observation–model percentage differences (Fig. 6e). Such underestimation of VOCs has been observed in various chemical transport models and mechanisms (She et al., 2024; W. Wang et al., 2024b; Ge et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2019; Rowlinson et al., 2024), though these studies primarily focus on NMHCs and provide limited evidence for OVOCs.

Figure 6Frequency distribution between ship-observed (in grey) and modeled (in red) concentrations for (a) ozone, (b) NO2, (c) NMHCs, and (d) OVOCs. VOC comparisons are conducted for equivalent species between “selective observed” and “modeled”. The percentage differences for each species are summarized in (e).

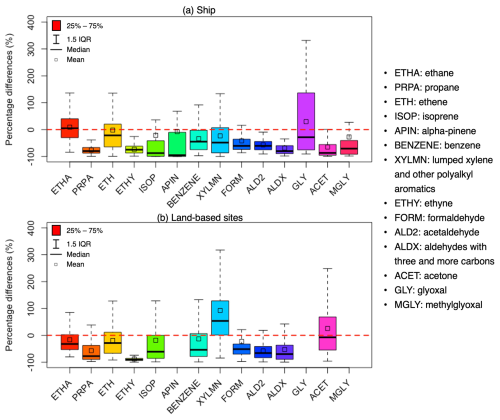

Figure 7The percentage differences between the observation and model for individual VOC species measured (a) on the ship and (b) at three land-based sites. Land-based measurements do not detect alpha-pinene (APIN), glyoxal (GLY), and methylglyoxal (MGLY).

We further break down these discrepancies into speciated differences in Fig. 7. The results indicate that, while certain species can be overestimated under specific conditions, such as lumped xylene and other polyalkyl aromatics (XYLMN) and acetone (ACET) at land-based measurements (Figs. 7b; S9), the majority of species are underestimated in the model. Our observation-to-model differences are comparable to those reported in previous studies that primarily focus on NMHCs; however, our findings also emphasize a greater presence of oxygenated compounds that were not addressed in those studies (Table S1). In our study, propane (PRPA) and ethyne (ETHY) exhibit the most significant underestimations. Propane is underestimated by an average of 76 % compared to shipborne measurements and 57 % for land-based measurements. Time series from land-based sites indicate that the underestimation mainly occurs in winter and early spring (Fig. S4). Both ethane and propane are significantly affected by leakage from oil and natural gas production and use (Ou et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2008; Ge et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2007), resulting in a strong correlation between the two (Fig. S10). The model accurately captures such correlation; however, ethane (ETHA) concentrations and variability are better simulated than those of propane (Fig. S10). This underestimation of propane, while ethane is reasonably simulated, has also been observed in various regions around the world (Ge et al., 2024; Rowlinson et al., 2024; Adedeji et al., 2023). Consequently, the model exhibits lower propane-to-ethane ratios compared to the measurements, suggesting the presence of unaccounted sources of propane emissions.

Meanwhile, ethyne is underestimated by 73 % and 88 % relative to shipborne and land-based measurements, respectively. Ethyne, ethene (ETH), and benzene (BENZENE) are recognized as key tracers for combustion-related activities, particularly from vehicular and residential sources, in emission inventories (Lyu et al., 2016; Ho et al., 2009). This is reflected in the strong correlations among these species simulated by the model (R ranging from 0.7 to 1), driven by the aforementioned emission inventories. However, land-based observations show only moderate correlations in the ethene-to-ethyne and benzene-to-ethyne relationships (R=0.5; Fig. S10), suggesting the presence of regionally unique sources of ethyne that may not be accounted for.

Speciated discrepancies for six OVOCs are also shown in Fig. 7, including formaldehyde (FORM; −42 % over water and −23 % on land), acetaldehyde (ALD2; −57 % over water and −58 % on land), aldehydes with three and more carbons (ALDX; −69 % over water and −53 % on land), acetone (ACET; −65 % over water and +99 % on land), glyoxal (GLY; +30 % over water), and methylglyoxal (MGLY; −27 % over water). While acetone at land-based sites and glyoxal over coastal waters are overestimated on average, other OVOC species remain underestimated by the model. Previous assessments of model performance in simulating OVOCs have been limited by the scarcity of available measurements and species (Rowlinson et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2024; She et al., 2024). Here, our unique capability to measure a series of OVOCs helps to address this gap.

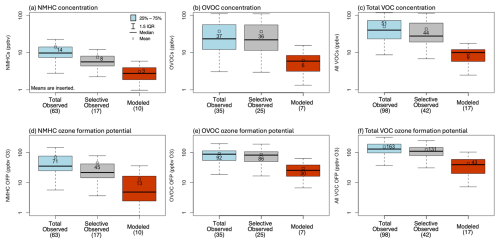

Figure 8Observation–model comparison of concentration and ozone formation potential (OFP) of NMHCs and OVOCs. “Total observed” includes all measured species. “Selective observed” and “modeled” refer to the equivalent species common to both observations and the model. Number in brackets indicates the number of species in each category. The y-axis is displayed on a logarithmic scale.

In the second comparison, we analyzed the gap between “modeled” versus `total observed' species (see Sect. 2.4 for details) to assess the overall representativeness of the modeled VOCs in relation to the full range of VOCs present in the ambient atmosphere. Figure 8 shows that the OVOC concentration of 37 ppbv accounts for 73 % of the total VOC concentration and 56 % of the total OFP, with NMHCs contributing a minor proportion. The total concentration of all measured VOCs of 51 ppbv can be broken down into three components when compared to the model (Fig. 8c). First, the concentrations successfully represented by the model account for 18 % (9 ppbv), as shown in the “modeled”. Second, model underestimation of equivalent species contributes 69 % (35 ppbv = 44–9 ppbv), indicated by the differences between “selective observed” and “modeled”. Third, model-omitted portion account for 14 % (7 ppbv = 51–44 ppbv), shown by the differences between “total observed” and “selective observed”. For OFP, the total measured is divided into 26 % successful model representation, 54 % model underestimation, and 20 % model-omitted portion (Fig. 8f). This result in 82 % and 74 % differences between `modeled' and `total observed' concentrations and OPF, respectively, highlighting the missing VOC reactivity in the model.

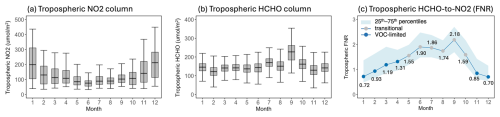

To further examine how the model underrepresentation of VOCs affects simulated ozone pollution regime, we use spaceborne tropospheric HCHO-to-NO2 ratio (FNR) as an indicator to infer regional ozone formation sensitivity (Wang Y. et al., 2023a; Jin et al., 2017; Goldberg et al., 2022; Acdan et al., 2023). Tropospheric FNR over Hong Kong exhibits distinct seasonal variation, with lower values during the cold months and higher values during warm months (Fig. 9c). According to a set of region- and season-specific FNR thresholds derived for the PRD, that is [1.55, 3.05] for spring and summer, [1.45, 2.95] for autumn, and [1.65, 3.15] for winter from Y. Wang et al. (2023a), we find that the cold months from November to April are VOC-limited, while the warm months from May to October fall into a transitional regime sensitive to both VOC and NOx (Fig. 9c). We acknowledge that the FNR method has limitations (Souri et al., 2025) and that the threshold should not be static in all scenarios. Other studies have also derived FNR thresholds but for China as a whole, including [2.2, 3.2] from Ren et al. (2022), [2.3, 4.2] from Wang et al. (2021), and [1.0, 1.9] from Li et al. (2021). Our PRD region-specific thresholds from Y. Wang et al. (2023a) fall within the ranges established by the aforementioned independent studies, but for China as a whole. Yet, because our thresholds are specifically tailored for our study region PRD, we place greater confidence in adopting them for our study compared to more general national conditions presented in other studies. Among all months, September shows the largest FNR (Fig. 9c) and the greatest monthly levels of ozone and HCHO (Fig. 2), making it highly relevant for regulatory management. Therefore, we take September 2022 as an example to illustrate the extent to which VOC underrepresentation in the model can potentially affect the spatial ozone sensitivity diagnosis and thereby regulatory measures in the following text.

Figure 9Monthly variation of TROPOMI tropospheric vertical column densities (VCDs) of (a) NO2 and (b) HCHO over the Hong Kong domain during 2021–2022. (c) The tropospheric HCHO-to-NO2 ratio (FNR) is calculated by dividing (a) by (b). The Pearl River Delta region-specific FNR thresholds for differentiating ozone formation regimes are from Y. Wang et al. (2023a): spring and summer [1.55, 3.05], autumn [1.45, 2.95], and winter [1.65, 3.15]. Spring covers March–May, summer covers June–August, autumn covers September–November, and winter covers December–February.

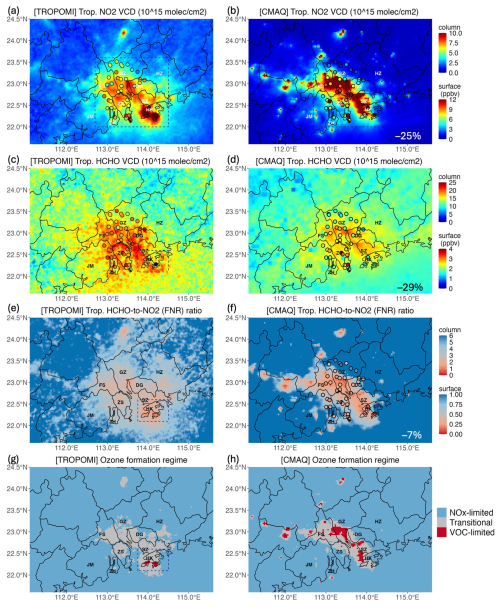

Figure 10Spatial patterns of TROPOM-observed (left) and CMAQ-modeled (right) tropospheric VCDs of NO2 and HCHO, the column HCHO-to-NO2 ratio (FNR), and ozone formation regime in September 2022. Dots represent surface measurements and their model equivalents from 4 and 5 September 2022; the medians of observation-model differences are inserted. Dashed line boxes indicate the Hong Kong domain.

TROPOMI indicates elevated NO2 and HCHO pollution in urban areas on both the eastern and western flanks of the Pearl River Estuary (Fig. 10a, c). The Estuary also experiences high pollution plumes, primarily influenced by shipping emissions over water and anthropogenic activities from nearby urban clusters. Compared to TROPOMI, the model captures the general spatial pattern (R=0.8 for NO2 and R=0.6 for HCHO) but the magnitudes vary (Fig. 10b, d). Due to the prevalence of low values in less polluted suburban areas, which significantly complicates observation-model comparisons for the domain as a whole, the domain mean or median does not well reflect differences in key polluted regions. Therefore, we overlay surface measurements of NO2 and HCHO onto these urban areas and identify the nearest model grid to perform observation-model comparisons. In this way, independent model-satellite and model-surface comparisons can be used together and verify one another in understanding the differences between observations and model in polluted regions. It is important to note that we do not directly compare surface measurements with column measurements; instead, we use these two sources of observations to conduct separate comparisons with the model, aiming to identify observation-model differences. Our findings indicate that both surface and column comparisons agree on NO2 overestimation in highly polluted areas such as southern Guangzhou (GZ), eastern Foshan (FS), and western Shenzhen (SZ), while showing underestimation in the less polluted northern Guangzhou (Fig. 10b). HCHO demonstrates regional underestimation (Fig. 10d). The median differences between surface observations and the model indicate a 25 % underestimation of NO2 and a 29 % underestimation of HCHO in the model.

The greater model underestimation of HCHO compared to NO2, consistent with findings from Sects. 3–4, results in the modeled FNR being 7 % lower than surface observations (Fig. 10f). Similarly, the model also simulates lower column FNRs than those observed by TROPOMI in polluted regions (Fig. 10f). This discrepancy indicates that the modeled ozone formation is more sensitive to VOCs than what surface measurements suggest in polluted regions. To probe into the ozone formation regimes inferred from spaceborne FNR, we used the fall season FNR thresholds tailored for the PRD from Y. Wang et al. (2023a) and identified a NOx-limited ozone formation regime in extensive suburban areas (FNR > 2.95; 91.7 % of total domain grids), a transitional regime in city clusters and busy shipping lanes of the eastern Pearl River Estuary (1.45≤ FNR ≤2.95; 8.1 % of total grids), and a VOC-limited regime on Hong Kong Island and Lantau (FNR < 1.45; 0.1 % of total grids) (Fig. 10g). The model identifies a larger VOC-limited region, accounting for 1.4 % of total domain grids (Fig. 10h), suggesting that it overestimates the extent of areas classified as VOC-limited regimes. This is partly attributed to inadequate representation of VOCs within the model framework. We note that regimes can vary depending on the choice of satellite inversion products and FNR thresholds. To address this, we analyzed different spaceborne NO2 products with relative differences ranging from −19 % to 50 % (25th–75th percentile) in the domain; yet these differences diminished in the regime classification, resulting 5 % of grids showing discrepancies between the two spaceborne products (Fig. S11). We also evaluated various FNR thresholds derived from Y. Wang et al. (2023a) and other independent studies (Figs. S12; S13). All results consistently indicate that the model simulates a higher prevalence of VOC-limited regions compared to TROPOMI, despite the variations in satellite inversion products and FNR thresholds applied in regime classifications.

As models serve as an important tool for deriving ozone sensitivity and pollution control strategies for regulatory agencies worldwide, their underrepresentation of VOCs results in a greater sensitivity to VOCs in models than what is observed in ambient air. Regions identified as a transitional regime, which could benefit from coordinated emission reductions of both NOx and VOCs, as inferred from TROPOMI, are suggested by the model to achieve ozone reduction primarily through VOC reductions alone (Fig. 10). This mismatch may lead to confusion for regulatory agencies in developing effective ozone control strategies and underscores the need to advance VOC-related model development to support effective air quality management.

The HKEPD-HKUST field campaign conducted in 2021–2022 provided the first overwater measurements of ozone and its precursors in Hong Kong coastal waters, complementing land-based monitoring efforts. Notably, the campaign advances in the ability to measure a wide array of VOC species, including a total of 98 species (63 MNHCs and 35 OVOCs) over water and 45 species (29 MNHCs and 16 OVOCs) on land. Such detailed speciation, particularly of oxygenated compounds, is valuable for model evaluation, especially given the limited availability of such measurements reported globally. This study leverages these field observations together with spaceborne TROPOMI data to assess the regional VOC and ozone pollution dynamics, and, more importantly, to diagnose VOC representation in the CMAQ chemical transport model and its implications on ozone pollution regulation.

Ozone levels in subtropical Hong Kong display a bimodal pattern, characterized by a minor peak in spring and a significant peak in autumn. Oxygenated compounds, particularly HCHO, reach their highest level in September, aligning with the peak monthly ozone levels. This underscores the active photochemistry in autumn and its contribution to VOC and ozone pollution. Comparing these observed features with the CMAQ model, we found that VOCs are typically underestimated by 47 %–48 % for NMHCs and 45 %–70 % for OVOCs over land and water. A detailed breakdown of the speciated comparison reveals the most significant underestimations in propane (76 % over water and 57 % on land) and ethyne (73 % over water and 88 % on land). Oxygenated compounds are also underestimated to varying degrees, such as formaldehyde (−42 % over water and −23 % on land), acetaldehyde (−57 % over water and −58 % on land). These differences between observations and models are referred to as the “underestimation” of equivalent VOC species.

Through speciated analysis, we infer potential reasons for the underestimation of VOC to support model development. Propane, primarily sourced from oil and natural gas leaks, and ethyne, linked to combustion activities, are primary species whose ambient levels are mostly emission-controlled. Addressing unaccounted emission sources and refining emission profiles for these primary species can help reduce the underestimation. In contrast, oxygenated compounds have both primary sources and are generated as oxidation products from other VOCs. This complexity makes it challenging to ascertain whether the underestimation arises from missing primary emissions, inadequate secondary chemical production, or overestimated chemical and deposition losses. Many studies emphasize that addressing OVOC emissions from VCPs is crucial for improving model simulations (S. Wang et al., 2024; Y. Wang et al., 2024; Coggon et al., 2021; Karl et al., 2018). Moving forward, there is a growing need to refine the speciation profiles (Rowlinson et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2024) and unaccounted sources (She et al., 2024; Travis et al., 2024; Beaudry et al., 2025) of VOC emissions, as well as to dissect a more detailed breakdown of the chemical mechanisms for oxygenated species (Travis et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2024) to improve model representation.

Apart from underestimation, another important aspect is that the model simulates only certain species from the total measured VOCs. Specifically, only 28 out of the 45 VOC species observed on land and 42 out of the 98 measured over water are represented in the model. These species, often regarded as less important and thus not included in the model, are defined as model “omission” in this study. In our case, the model omits 17 species (38 %) observed on land and 56 species (57 %) observed over water, respectively. Together, “omission” and “underestimation” contribute to what we define as “VOC underrepresentation” for models. This way, the total concentration of all measured VOCs of 51 ppbv over water can be broken down into three factors when compared to the model: 18 % successful model representation, 69 % model underestimation of equivalent species, and 14 % model-omitted portion. Similarly for OFP, the total measured is divided into 26 % model representation, 54 % model underestimation, and 20 % model omission. Among the three factors, underestimation is the most important; addressing it is both impactful and feasible, making it a priority for model development. Omitted species require further evidence to identify which specific species or groups are particularly important yet overlooked in our current understanding.

Previous modeling studies have primarily focused on NMHCs, while assessments of OVOC have been limited by the scarcity of available measurements. Our study measured a wide array of OVOCs to help address this gap. We found that OVOCs account for 73 % of the total concentration and 56 % of the total OFP of all measured VOC species over water. Despite such importance, OVOCs are underestimated to a greater extent than NMHCs in the model. While emissions of short-chain NMHCs associated with fossil fuels and combustion have notably decreased, future emission patterns are shifting towards increased OVOCs due to rising solvent use and consumer products. Our assessment serves as a valuable reference for informing OVOC representation in models, and offers insights into how model underrepresentation may impact the future atmosphere as emission patterns evolve. Community efforts are urged to integrate global VOC speciated measurements, particularly on OVOC components that have been less emphasized in current model validation but are expect to become increasingly important.

The insufficient representation of VOCs in the model impacts policy-relevant ozone formation sensitivity and pollution control strategies. We approach this using the widely used FNR method for diagnosing ozone formation sensitivity. Both spaceborne TROPIMI and surface measurements indicate lower FNRs simulated by the model than those observed in pollution hotspots in the PRD region, implying that the simulated ozone formation may be overly sensitive to VOCs. As models are critical tools for deriving ozone sensitivity and pollution control strategies for regulatory agencies worldwide, the underrepresentation of VOCs could lead to a skewed understanding of ozone sensitivity and misguide effective control measures. This issue ripples through broader geographical regions, as VOC underrepresentation has also been noted in other Chinese cities (She et al., 2024; W. Wang et al., 2024b), as well as in Europe (Ge et al., 2024), North America (Chen et al., 2019), and globally (Rowlinson et al., 2024). From a broader Earth system perspective, such VOC underrepresentation may be associated with the OH reactivity underestimation in models (Travis et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2022; Ferracci et al., 2018), which has significant implications, not only for regional air quality through ozone and secondary organic aerosols, but also for the lifetimes of greenhouse gases and global climate (Turner et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2025).

Overall, our study demonstrates the significant contribution of OVOCs in both the urban environment of Hong Kong and its adjacent coastal waters, reveals the underrepresentation of VOCs in models, and highlights the impact of this VOC underrepresentation on ozone pollution regulations. Our findings serve as a valuable reference for understanding regional VOC and ozone dynamics, advancing VOC-related model development, and fostering a synergistic assessment of the broader impacts of underrepresented VOCs on air quality and climate from a coherent Earth system perspective.

WRF and CMAQ are open-source models and can be obtained from their developers. Model output data and field measurements are available upon request. Shipborne OVOC measurements are available on an open-source data platform: https://doi.org/10.14711/dataset/HFRZ8M (Liu, 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-17629-2025-supplement.

XL designed the study, conducted the analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript with guidance from JCHF and ZW. YH performed the CMAQ simulations. ZW, YC, XF, YX, and YC provided the shipborne OVOC data. DG and SH provided the shipborne NMHC data. ZN provided the shipborne NOx and ozone data. JY and BC provided the HKUST supersite data. CL, YX, and TZ provided ozone lidar data. CG and GB contributed to the TROPOMI analysis. All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We appreciate the assistance of the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department (HKEPD), which provided some air quality data. XL acknowledges the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) Research Assistant Professor (RAP) scheme. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Environment and Conservation Fund.

This research has been supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China, National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFC3709200); the Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee (grant nos. C7041-21G, 16209022, 16211824, N_HKUST626/24, and N_HKUST609/21); and the Environment and Conservation Fund (grant no. 195/2024).

This paper was edited by Arthur Chan and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Acdan, J. J. M., Pierce, R. B., Dickens, A. F., Adelman, Z., and Nergui, T.: Examining TROPOMI formaldehyde to nitrogen dioxide ratios in the Lake Michigan region: implications for ozone exceedances, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 7867–7885, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-7867-2023, 2023.

Adedeji, A. R., Andrews, S. J., Rowlinson, M. J., Evans, M. J., Lewis, A. C., Hashimoto, S., Mukai, H., Tanimoto, H., Tohjima, Y., and Saito, T.: Measurement report: Assessment of Asian emissions of ethane and propane with a chemistry transport model based on observations from the island of Hateruma, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 9229–9244, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-9229-2023, 2023.

Appel, K. W., Bash, J. O., Fahey, K. M., Foley, K. M., Gilliam, R. C., Hogrefe, C., Hutzell, W. T., Kang, D., Mathur, R., Murphy, B. N., Napelenok, S. L., Nolte, C. G., Pleim, J. E., Pouliot, G. A., Pye, H. O. T., Ran, L., Roselle, S. J., Sarwar, G., Schwede, D. B., Sidi, F. I., Spero, T. L., and Wong, D. C.: The Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model versions 5.3 and 5.3.1: system updates and evaluation, Geosci. Model Dev., 14, 2867–2897, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-2867-2021, 2021.

Bates, K. H., Jacob, D. J., Li, K., Ivatt, P. D., Evans, M. J., Yan, Y., and Lin, J.: Development and evaluation of a new compact mechanism for aromatic oxidation in atmospheric models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 18351–18374, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-18351-2021, 2021.

Bates, K. H., Evans, M. J., Henderson, B. H., and Jacob, D. J.: Impacts of updated reaction kinetics on the global GEOS-Chem simulation of atmospheric chemistry, Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 1511–1524, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-1511-2024, 2024.

Beaudry, E., Jacob, D. J., Bates, K. H., Zhai, S., Yang, L. H., Pendergrass, D. C., Colombi, N., Simpson, I. J., Wisthaler, A., Hopkins, J. R., and Li, K.: Ethanol and Methanol in South Korea and China: Evidence for Large Anthropogenic Emissions Missing from Current Inventories, ACS Es&t Air, 2, 456–465, 2025.

Brewer, J. F., Millet, D. B., Wells, K. C., Payne, V. H., Kulawik, S., Vigouroux, C., Cady-Pereira, K. E., Pernak, R., and Zhou, M.: Space-based observations of tropospheric ethane map emissions from fossil fuel extraction, Nat. Commun., 15, 7829, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52247-z, 2024.

Carter, W. P. L.: Updated Maximum Incremental Reactivity Scale and Hydrocarbon Bin Reactivities for Regulatory Applications, Prepared for California Air Resources Board Contract 07-339, https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2009/mir2009/mir10.pdf (last access: 1 December 2025), 2010.

Chan, L. Y., Chan, C. Y., Liu, H. Y., Christopher, S., Oltmans, S. J., and Harris, J. M.: A case study on the biomass burning in Southeast Asia and enhancement of tropospheric ozone over Hong Kong, Geophysical Research Letters, 27, 1479–1482, 2000.

Che, W., Frey, H. C., Fung, J. C., Ning, Z., Qu, H., Lo, H. K., Chen, L., Wong, T. W., Wong, M. K., Lee, O. C., and Carruthers, D.: PRAISE-HK: A personalized real-time air quality informatics system for citizen participation in exposure and health risk management, Sustainable Cities and Society, 54, 101986, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101986, 2020.

Chen, Q., Miao, R., Geng, G., Shrivastava, M., Dao, X., Xu, B., Sun, J., Zhang, X., Liu, M., Tang, G., and Tang, Q.: Widespread 2013–2020 decreases and reduction challenges of organic aerosol in China, Nature Communications, 15, 4465, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48902-0, 2024.

Chen, W. T., Shao, M., Lu, S. H., Wang, M., Zeng, L. M., Yuan, B., and Liu, Y.: Understanding primary and secondary sources of ambient carbonyl compounds in Beijing using the PMF model, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 3047–3062, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-3047-2014, 2014.

Chen, X., Millet, D. B., Singh, H. B., Wisthaler, A., Apel, E. C., Atlas, E. L., Blake, D. R., Bourgeois, I., Brown, S. S., Crounse, J. D., de Gouw, J. A., Flocke, F. M., Fried, A., Heikes, B. G., Hornbrook, R. S., Mikoviny, T., Min, K.-E., Müller, M., Neuman, J. A., O'Sullivan, D. W., Peischl, J., Pfister, G. G., Richter, D., Roberts, J. M., Ryerson, T. B., Shertz, S. R., Thompson, C. R., Treadaway, V., Veres, P. R., Walega, J., Warneke, C., Washenfelder, R. A., Weibring, P., and Yuan, B.: On the sources and sinks of atmospheric VOCs: an integrated analysis of recent aircraft campaigns over North America, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 9097–9123, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-9097-2019, 2019.

Chen, Y., Lu, X., and Fung, J. C. H.: Spatiotemporal source apportionment of ozone pollution over the Greater Bay Area, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 8847–8864, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-8847-2024, 2024.

Coggon, M. M., Gkatzelis, G. I., McDonald, B. C., Gilman, J. B., Schwantes, R. H., Abuhassan, N., Aikin, K. C., Arend, M. F., Berkoff, T. A., Brown, S. S., and Campos, T. L.: Volatile chemical product emissions enhance ozone and modulate urban chemistry, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, e2026653118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2026653118, 2021.

Cui, L., Zhang, Z., Huang, Y., Lee, S. C., Blake, D. R., Ho, K. F., Wang, B., Gao, Y., Wang, X. M., and Louie, P. K. K.: Measuring OVOCs and VOCs by PTR-MS in an urban roadside microenvironment of Hong Kong: relative humidity and temperature dependence, and field intercomparisons, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 5763–5779, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-5763-2016, 2016.

Douros, J., Eskes, H., van Geffen, J., Boersma, K. F., Compernolle, S., Pinardi, G., Blechschmidt, A.-M., Peuch, V.-H., Colette, A., and Veefkind, P.: Comparing Sentinel-5P TROPOMI NO2 column observations with the CAMS regional air quality ensemble, Geosci. Model Dev., 16, 509–534, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-16-509-2023, 2023.

Eskes, H., van Geffen, J., Sneep, M., Veefkind, P., Niemeijer, S., and Zehner, C.: S5P Nitrogen Dioxide v02.03.01 intermediate reprocessing on the S5P-PAL system: Readme file, https://data-portal.s5p-pal.com/product-docs/no2/PAL_reprocessing_NO2_v02.03.01_20211215.pdf (last access: 1 December 2025), 2021.

Feng, X., Guo, J., Wang, Z., Gu, D., Ho, K. F., Chen, Y., Liao, K., Cheung, V. T., Louie, P. K., Leung, K. K., and Yu, J. Z.: Investigation of the multi-year trend of surface ozone and ozone-precursor relationship in Hong Kong, Atmospheric Environment, 315, 120139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.120139, 2023.

Ferracci, V., Heimann, I., Abraham, N. L., Pyle, J. A., and Archibald, A. T.: Global modelling of the total OH reactivity: investigations on the “missing” OH sink and its atmospheric implications, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7109–7129, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7109-2018, 2018.

Gao, Y., Li, R., Wang, F., Wu, C., Zhang, F., Li, Y., Huo, J., Chen, J., Cui, H., Fu, Q., and Wang, G.: A Newly Discovered Ozone Formation Mechanism Observed in a Coastal Island of East China, ACS ES&T Air, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestair.4c00082 (last access: 3 December 2025), 2024.

Ge, Y., Solberg, S., Heal, M. R., Reimann, S., van Caspel, W., Hellack, B., Salameh, T., and Simpson, D.: Evaluation of modelled versus observed non-methane volatile organic compounds at European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme sites in Europe, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 7699–7729, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-7699-2024, 2024.

Goldberg, D. L., Harkey, M., de Foy, B., Judd, L., Johnson, J., Yarwood, G., and Holloway, T.: Evaluating NOx emissions and their effect on O3 production in Texas using TROPOMI NO2 and HCHO, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 10875–10900, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-10875-2022, 2022.

Guenther, A. B., Jiang, X., Heald, C. L., Sakulyanontvittaya, T., Duhl, T., Emmons, L. K., and Wang, X.: The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions, Geosci. Model Dev., 5, 1471–1492, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012, 2012.

Guo, H., So, K. L., Simpson, I. J., Barletta, B., Meinardi, S., and Blake, D. R.: C1–C8 volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere of Hong Kong: overview of atmospheric processing and source apportionment, Atmospheric Environment, 41, 1456–1472, 2007.

Ha, E. S., Park, R. J., Kwon, H.-A., Lee, G. T., Lee, S. D., Shin, S., Lee, D.-W., Hong, H., Lerot, C., De Smedt, I., Danckaert, T., Hendrick, F., and Irie, H.: First evaluation of the GEMS glyoxal products against TROPOMI and ground-based measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 6369–6384, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-6369-2024, 2024.

Ho, K. F., Lee, S. C., Ho, W. K., Blake, D. R., Cheng, Y., Li, Y. S., Ho, S. S. H., Fung, K., Louie, P. K. K., and Park, D.: Vehicular emission of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from a tunnel study in Hong Kong, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 7491–7504, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-7491-2009, 2009.

Jin, X., Fiore, A., Boersma, K. F., De Smedt, I., and Valin, L.: Inferring Changes in Summertime Surface Ozone–NOx–VOC Chemistry over U.S. Urban Areas from Two Decades of Satellite and Ground-Based Observations, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 6518–6529, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b07785, 2020.

Jin, X., Fiore, A. M., Murray, L. T., Valin, L. C., Lamsal, L. N., Duncan, B., Folkert Boersma, K., De Smedt, I., Abad, G. G., Chance, K., and Tonnesen, G. S.: Evaluating a space-based indicator of surface ozone-NOx-VOC sensitivity over midlatitude source regions and application to decadal trends, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 122, 10–439, 2017.

Karl, T., Striednig, M., Graus, M., Hammerle, A., and Wohlfahrt, G.: Urban flux measurements reveal a large pool of oxygenated volatile organic compound emissions, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 1186–1191, 2018.

Kim, H., Park, R. J., Kim, S., Brune, W. H., Diskin, G. S., Fried, A., Hall, S. R., Weinheimer, A. J., Wennberg, P., Wisthaler, A., Blake, D. R., and Ullmann, K.: Observed versus simulated OH reactivity during KORUS-AQ campaign: Implications for emission inventory and chemical environment in East Asia, Elem. Sci. Anth., 10, 00030, https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2022.00030, 2022.

Lee, Y. C., Chan, K. L., and Wenig, M. O.: Springtime warming and biomass burning causing ozone episodes in South and Southwest China, Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 12, 919–931, 2019.

Lerot, C., Hendrick, F., Van Roozendael, M., Alvarado, L. M. A., Richter, A., De Smedt, I., Theys, N., Vlietinck, J., Yu, H., Van Gent, J., Stavrakou, T., Müller, J.-F., Valks, P., Loyola, D., Irie, H., Kumar, V., Wagner, T., Schreier, S. F., Sinha, V., Wang, T., Wang, P., and Retscher, C.: Glyoxal tropospheric column retrievals from TROPOMI – multi-satellite intercomparison and ground-based validation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 14, 7775–7807, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-14-7775-2021, 2021.

Li, K., Jacob, D. J., Liao, H., Qiu, Y., Shen, L., Zhai, S., Bates, K. H., Sulprizio, M. P., Song, S., Lu, X., Zhang, Q., Zheng, B., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Lee, H. C., and Kuk, S. K.: Ozone pollution in the North China Plain spreading into the latewinter haze season, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 118, e2015797118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015797118, 2021.

Li, M., Zhang, Q., Streets, D. G., He, K. B., Cheng, Y. F., Emmons, L. K., Huo, H., Kang, S. C., Lu, Z., Shao, M., Su, H., Yu, X., and Zhang, Y.: Mapping Asian anthropogenic emissions of non-methane volatile organic compounds to multiple chemical mechanisms, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 5617–5638, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-5617-2014, 2014.

Li, R., Xu, M., Li, M., Chen, Z., Zhao, N., Gao, B., and Yao, Q.: Identifying the spatiotemporal variations in ozone formation regimes across China from 2005 to 2019 based on polynomial simulation and causality analysis, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 15631–15646, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-15631-2021, 2021.

Li, W., Wang, Y., Liu, X., Soleimanian, E., Griggs, T., Flynn, J., and Walter, P.: Understanding offshore high-ozone events during TRACER-AQ 2021 in Houston: insights from WRF–CAMx photochemical modeling, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 13685–13699, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-13685-2023, 2023.

Liu, Y., Shao, M., Lu, S., Chang, C.-C., Wang, J.-L., and Chen, G.: Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) measurements in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 1531–1545, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-1531-2008, 2008.

Liu, Q., Gao, Y., Huang, W., Ling, Z., Wang, Z., and Wang, X.: Carbonyl compounds in the atmosphere: a review of abundance, source and their contributions to O3 and SOA formation, Atmos. Res., 274, 106184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2022.106184, 2022.

Liu, X., Wang, Y., Wasti, S., Lee, T., Li, W., Zhou, S., Flynn, J., Sheesley, R. J., Usenko, S., and Liu, F.: Impacts of anthropogenic emissions and meteorology on spring ozone differences in San Antonio, Texas between 2017 and 2021, Science of The Total Environment, 914, 169693, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169693, 2024. Liu, X., Shipborne OVOC measurements over Hong Kong waters during 2021–2022, DataSpace@HKUST [data set], https://doi.org/10.14711/dataset/HFRZ8M, 2025.

Luecken, D. J., Yarwood, G., and Hutzell, W. T.: Multipollutant modeling of ozone, reactive nitrogen and HAPs across the continental US with CMAQ-CB6, Atmos. Environ., 201, 62–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.11.060, 2019.

Lyu, X., Guo, H., Simpson, I. J., Meinardi, S., Louie, P. K. K., Ling, Z., Wang, Y., Liu, M., Luk, C. W. Y., Wang, N., and Blake, D. R.: Effectiveness of replacing catalytic converters in LPG-fueled vehicles in Hong Kong, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 6609–6626, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-6609-2016, 2016.

Mai, Y., Cheung, V., Louie, P. K., Leung, K., Fung, J. C., Lau, A. K., Blake, D. R., and Gu, D.: Characterization and source apportionment of volatile organic compounds in Hong Kong: A 5-year study for three different archetypical sites, Journal of Environmental Sciences, 151, 424–440, 2025.

Mo, X., Gong, D., Liu, Y., Li, J., Zhao, Y., Zhao, W., Shen, J., Liao, T., Wang, H., and Wang, B.: Ground-based formaldehyde across the Pearl River Delta: a snapshot and meta-analysis study, Atmos. Environ., 309, 119935 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119935, 2023.

Mo, Z., Shao, M., and Lu, S.: Compilation of a source profile database for hydrocarbon and OVOC emissions in China, Atmospheric Environment, 143, 209–217, 2016.

Ou, J., Guo, H., Zheng, J., Cheung, K., Louie, P. K., Ling, Z., and Wang, D.: Concentrations and sources of non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHCs) from 2005 to 2013 in Hong Kong: A multi-year real-time data analysis, Atmospheric Environment, 103, 196–206, 2015.

Ou, J., Zheng, J., Yuan, Z., Guan, D., Huang, Z., Yu, F., Shao, M., and Louie, P. K.: Reconciling discrepancies in the source characterization of VOCs between emission inventories and receptor modeling, Science of the Total Environment, 628, 697–706, 2018.

Ouyang, S., Deng, T., Liu, R., Chen, J., He, G., Leung, J. C.-H., Wang, N., and Liu, S. C.: Impact of a subtropical high and a typhoon on a severe ozone pollution episode in the Pearl River Delta, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 10751–10767, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-10751-2022, 2022.

Ren, J., Guo, F., and Xie, S.: Diagnosing ozone–NOx–VOC sensitivity and revealing causes of ozone increases in China based on 2013–2021 satellite retrievals, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 15035–15047, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-15035-2022, 2022.

Rowlinson, M. J., Evans, M. J., Carpenter, L. J., Read, K. A., Punjabi, S., Adedeji, A., Fakes, L., Lewis, A., Richmond, B., Passant, N., Murrells, T., Henderson, B., Bates, K. H., and Helmig, D.: Revising VOC emissions speciation improves the simulation of global background ethane and propane, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 8317–8342, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-8317-2024, 2024.

Seltzer, K. M., Pennington, E., Rao, V., Murphy, B. N., Strum, M., Isaacs, K. K., and Pye, H. O. T.: Reactive organic carbon emissions from volatile chemical products, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 5079–5100, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-5079-2021, 2021.

She, Y., Li, J., Lyu, X., Guo, H., Qin, M., Xie, X., Gong, K., Ye, F., Mao, J., Huang, L., and Hu, J.: Current status of model predictions of volatile organic compounds and impacts on surface ozone predictions during summer in China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 219–233, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-219-2024, 2024.

Souri, A. H., Kumar, R., Chong, H., Golbazi, M., Knowland, K. E., Geddes, J., and Johnson, M. S.: Decoupling in the vertical shape of HCHO during a sea breeze event: The effect on trace gas satellite retrievals and column-to-surface translation, Atmos. Environ., 309, 119929, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119929, 2023.

Souri, A. H., González Abad, G., Wolfe, G. M., Verhoelst, T., Vigouroux, C., Pinardi, G., Compernolle, S., Langerock, B., Duncan, B. N., and Johnson, M. S.: Feasibility of robust estimates of ozone production rates using a synergy of satellite observations, ground-based remote sensing, and models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 2061–2086, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-2061-2025, 2025.

Stavrakou, T., Müller, J. F., Peeters, J., Razavi, A., Clarisse, L., Clerbaux, C., Coheur, P. F., Hurtmans, D., De Mazière, M., Vigouroux, C., and Deutscher, N. M.: Satellite evidence for a large source of formic acid from boreal and tropical forests, Nature Geoscience, 5, 26–30, 2012.

Sun, H., Gu, D., Feng, X., Wang, Z., Cao, X., Sun, M., Ning, Z., Zheng, P., Mai, Y., Xu, Z., and Chan, W.M.: Cruise observation of ambient volatile organic compounds over Hong Kong coastal water, Atmospheric Environment, 323, 120387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120387, 2024.

Sun, L., Wong, K. C., Wei, P., Ye, S., Huang, H., Yang, F., Westerdahl, D., Louie, P. K., Luk, C. W., and Ning, Z.: Development and application of a next generation air sensor network for the Hong Kong marathon 2015 air quality monitoring, Sensors, 16, 211, https://doi.org/10.3390/s16020211, 2016.

Tonnesen, G. S. and Dennis, R. L.: Analysis of radical propagation efficiency to assess ozone sensitivity to hydrocarbons and NOx: 2. Long-lived species as indicators of ozone concentration sensitivity, J. Geophys. Res., 105, 9227–9241, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900372, 2000.