the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Increased number concentrations of small particles explain perceived stagnation in air quality over Korea

Sohee Joo

Juseon Shin

Matthias Tesche

Naghmeh Dehkhoda

Taegyeong Kim

Youngmin Noh

The atmospheric visibility in South Korea has not improved despite decreasing mass concentrations of particulate matter (PM)2.5. Since visibility is influenced by particle size and composition as well as meteorological factors, light detection and ranging (lidar) data provided by the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Japan and PM2.5 measurements retrieved from AirKorea are used to determine the trends in PM2.5 mass extinction efficiency (MEE) in Seoul and Ulsan, South Korea, from 2015 to 2020. Moreover, the monthly trends in the Ångström exponent and relative and absolute humidity are determined to identify the factors influencing PM2.5 MEE. The monthly average PM2.5 MEE exhibits an increasing trend in Seoul (+0.04 m2 g−1 per month) and Ulsan (+0.07 m2 g−1 per month). Relative humidity increases by +0.070 % and +0.095 % per month in Seoul and Ulsan, respectively, and absolute humidity increases by +0.029 and +0.010 g m−3 per month, respectively. However, the trends in these variables are not statistically significant. The Ångström exponent increases by +0.005 and +0.011 per month in Seoul and Ulsan, respectively, indicating that the MEE increases as the size of the particles becomes smaller each year. However, due to limitations when obtaining long-term composition data in this study, further research is needed to accurately determine the causes of the increase in PM2.5 MEE. Such an increase in PM2.5 MEE may have limited the improvements in visibility and adversely affected public perception of air quality improvement even though the PM2.5 mass concentration in South Korea is continuously decreasing.

- Article

(2794 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Particulate matter (PM)2.5, which refers to particles with an aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 µm, significantly affects atmospheric visibility, ecosystems, regional and global climate, and human health (Yue et al., 2017; De Marco et al., 2019; An et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Hao et al., 2021). As PM2.5 is hazardous to human health, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which is under the World Health Organization, classified PM2.5 as a group 1 carcinogen in 2013 (IARC, 2013). The governments of South Korea and China, which are countries in northeast Asia with severe air pollution due to fine particles, have also recognized the acute problem with PM2.5 pollution and, thus, have enacted and implemented policies to address it (Jung, 2016; Van Donkelaar et al., 2016; Geng et al., 2019; Zhang and Geng, 2019; Zhai et al., 2019). In particular, the Chinese government implemented the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan in 2013 through strict emission controls (Gao et al., 2020); consequently, the concentration of PM2.5 in China has decreased since 2013 (Zhang et al., 2019; Yue et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022), and such a reduction has also led to a decrease in the concentration of PM2.5 in South Korea, which is located downwind of China (Xie and Liao, 2022). Similarly, the South Korean government has enacted various policies, including managing old diesel vehicles and expanding PM2.5 monitoring stations. In fact, since the establishment of the nationwide PM2.5 observation network and distribution of real-time observation data in 2015, the PM2.5 concentration in South Korea has exhibited a decreasing trend (Bae et al., 2021).

However, despite the decreasing PM2.5 concentration, public perception of fine particles has not significantly improved. Among the environmental health issues included in the perception survey conducted by Won et al. (2022), experts perceived that climate change is the most critical issue; however, 80.9 % of the citizens responded that PM2.5 pollution is the most pressing environmental concern, confirming that most South Korean citizens are still afraid of PM2.5 pollution.

Non-expert citizens perceive atmospheric PM2.5 concentration visually: clear visibility indicates a low PM2.5 concentration and, thus, clean air; meanwhile, haziness indicates a high PM2.5 concentration. Visibility decreases as the concentration of fine particles suspended in the atmosphere increases because more particles scatter light (Fu-Qi et al., 2005; Liao et al., 2020). However, there have been several instances in northeast Asia wherein improved visibility did not equal reduced PM2.5 concentration. Xu et al. (2020) reported that although the PM2.5 levels in Guangzhou, China, decreased by more than 30 % from 2013 to 2018, the frequency of low-visibility events only decreased by 5 %. They suggested that the persistence of low visibility might prevent citizens from perceiving significant alleviation in aerosol pollution. Additionally, Liu et al. (2020) observed that although the PM2.5 concentration in eastern China continuously declined between 2013 and 2018, there was no corresponding improvement in visibility. They attributed this phenomenon to the increase in nitrate levels and relative humidity. Furthermore, Jeong et al. (2022) observed that the improvement in visibility in Seoul, South Korea, between 2012 and 2018 was not as pronounced as the decrease in PM2.5 concentrations due to the composition of the particles.

Particle characteristics and meteorological conditions may alter the light-scattering properties of particles, which, in turn, affect visibility. When the size of particles in the atmosphere decreases, their light-scattering ability increases, leading to a reduction in visibility (Zhou et al., 2019). Furthermore, the extent to which particles scatter and absorb light varies depending on their composition (Yuan et al., 2006; Qu et al., 2015); for example, hydrophilic and hydrophobic particles differ in their light-scattering properties (Li et al., 2017). The aerosol mass extinction efficiency (MEE) is a key factor in the assessment of the degree of light scattering per unit of mass, which varies under different conditions. An increase in MEE indicates that although particles have the same mass concentration, changes in particle characteristics or meteorological conditions enhance the light-scattering ability of particles in the atmosphere.

Although several studies on MEE have been conducted in northeast Asia, research on the underlying causes and long-term trends in MEE is scarce. Joo et al. (2022) used long-term visibility data in South Korea to calculate the MEEs of PM2.5 and PM10, confirming an increasing trend in PM2.5 and PM10 MEEs compared to those in 2015. However, the accuracy of calculating the extinction coefficient of PM2.5 using the Koschmieder formula, which involves subtracting the mass concentration values of PM2.5−10 from visibility data, is limited because it may generate values that are higher than the actual ones. Additionally, changes in particle size could not be confirmed, preventing the determination of the cause for the increase in MEE.

In this study, we use the light detection and ranging (lidar) data provided by the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) of Japan through its Asian Dust and Aerosol Lidar Observation Network (AD-Net) and the PM2.5 mass concentration data provided by AirKorea to calculate the MEE of PM2.5 and understand its trends. Section 2 describes the method of applying particle size information obtained from the lidar data to calculate the MEE of PM2.5. In Sect. 3, we analyze the trends in PM2.5 mass concentration, visibility, and PM2.5 MEE variations; moreover, we examine the factors contributing to the variations in PM2.5 MEE and the trends in PM2.5 MEE in northeast Asia. Finally, Sect. 4 summarizes the results of our research. As MEE is essential for converting the concentration obtained through optical measurements into the actual mass concentration of fine particles suspended in the atmosphere, the findings of this study contribute to the comprehensive assessment of the changes in PM characteristics in northeast Asia.

2.1 Analysis sites and data collection

The AD-Net, operated by the NIES in Japan, is a lidar network that continuously monitors the vertical distribution of aerosols in Asia. Approximately 20 lidar observation stations have been established across Asia; currently, the observation stations in Korea are located in Seoul (37.46° N, 126.95° E) and Ulsan (35.58° N, 129.19° E). The lidar generates data for altitudes from 12 to 17 982 m at 30 m intervals every 15 min; moreover, it provides information on the mixing layer height, the aerosol depolarization ratio, and backscatter coefficients at wavelengths of 532 and 1064 nm. A detailed description of the lidar system used to obtain the observation data can be found in the studies by Shimizu et al. (2016) and Xie et al. (2008). The lidar data recorded in Seoul and Ulsan from January 2015 to December 2020, which were obtained from the NIES website (http://www-lidar.nies.go.jp/AD-Net/, last access: 10 March 2024), are analyzed in this study.

To analyze the trend in PM mass concentration along with the optical concentration of fine particles, data on atmospheric pollutants recorded by the monitoring stations near the lidar observation sites – Gwanak-gu, Seoul (37.49° N, 126.93° E), and Samnam-eup, Ulsan (35.56° N, 129.11° E) – are also analyzed. The monitoring stations in Seoul and Ulsan are 3.77 and 7.57 km away, respectively, from the designated lidar observation stations. The mass concentration of fine particles is obtained from the final confirmed data on atmospheric pollutants available on the website of AirKorea (https://www.airkorea.or.kr/web/, last access: 16 February 2024), which is operated by the Korea Environment Corporation. The PM concentration data are finalized and rigorously validated. The data were first measured according to official test methods. They then underwent primary validation by the Seoul Metropolitan Air Quality Management Office and the Korea Environment Corporation. This was followed by secondary validation performed by the National Institution of Environmental Research (NIER), after which the final validated data were released. Given that these data are validated and finalized by highly credible institutions, we have conducted our analysis based on their reliability.

As visibility varies depending on the extent to which light is scattered or absorbed by particles or gases in the atmosphere and is correlated to the concentration of fine particles, it directly indicates the degree of air pollution (Huang et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2016). Accordingly, the visibility data recorded by the meteorological administration for each city at the same time as the lidar measurements were taken are also analyzed. Additionally, to ensure the accuracy of the lidar data, ground meteorological observation data provided by the meteorological administration are used to exclude the lidar data recorded on rainy, snowy, or foggy days. Thus, only the PM concentration measurements and lidar data that are available at the same time are analyzed in this study. Moreover, to assess the impact of humidity on particles, the trends in relative humidity and absolute humidity are simultaneously examined. Since the Korea Meteorological Administration currently only provides data on relative humidity, we use actual vapor pressure and temperature data to calculate the absolute humidity, which represents the ratio of water vapor mass to the total volume of air. The Vaisala formula is employed (Vaisala, 2013):

where C represents the constant 2.16679 gK J−1, Ea denotes the actual vapor pressure (in hPa), and T represents the temperature (in °C). Actual vapor pressure, temperature, visibility, and relative humidity data can be verified by referring to the ground meteorological observation data.

2.2 Calculation of extinction coefficients for fine- and coarse-mode particles

The extinction coefficient indicates the extent to which light is scattered and absorbed by particles and gases in the atmosphere. Generally, there is a positive correlation between the mass concentration and extinction coefficient of fine particles, with higher values observed on polluted days than clean-air days, leading to a reduction in visibility (Fu-Qi et al., 2005; Liao et al., 2020). Backscatter-related Ångström exponents (Å) are used to distinguish between fine- (index F) and coarse-mode (index C) particles in the lidar measurements. The total backscatter coefficient (βT) for each wavelength (λ) observed by lidar (532 and 1064 nm in our case) is equal to the sum of the backscatter coefficients of fine- (βF) and coarse-mode particles (βC):

The Ångström exponent provides information about particle size, with values closer to 0 indicating the dominance of large particles in the atmosphere (Ångström, 1929; Schuster et al., 2006). It is calculated as

Equation (3) can be expressed for the total backscatter coefficient, backscatter coefficient of fine-mode particles, and backscatter coefficient of coarse-mode particles.

Substitution of Eqs. (5) and (6) into Eqs. (2) and (4) yields Eqs. (7) and (8), which give a way of deriving backscatter coefficients of fine- and coarse-mode particles at 532 nm, respectively.

PM concentration is referred to as PM2.5 when the aerodynamic diameter of the particle is less than 2.5 µm and as PM10 when the aerodynamic diameter of the particle is less than 10 µm. In our analysis of aerosol optical properties, the classification into fine mode and coarse mode assumes that particles with an effective radius of less than 1 µm are in the fine mode, whereas particles with an effective radius larger than 1 µm are considered to be in the coarse mode (Schuster et al., 2006; O'Neill et al., 2023). Consequently, the backscatter coefficients of fine- (βF,532) and coarse-mode particles (βC,532) at 532 nm are assumed to correspond to the light extinction caused by PM2.5 and PM2.5−10 particles, respectively. For the calculations, the Ångström exponent for fine-mode particles (ÅF) is assumed to be 3, while that for coarse-mode particles (ÅC) is assumed to be 0; such assumed Ångström exponent values are calculated based on simulations using the Mie theory, considering particle volume size distribution and a refractive index of 1.5 + 0.001i (Dubovik et al., 2002; Veselovskii et al., 2004).

Multiplying the lidar ratio (S) by β separated into fine- and coarse-mode particles, the final extinction coefficients (α) for fine- and coarse-mode particles are calculated as

In this study, lidar data are not reliable close to the surface. Consequently, the lidar signal data from 162 m to the maximum height determined by the mixing layer height are averaged on an hourly basis for analysis.

2.3 LR and MEE

The lidar ratio (LR) varies depending on aerosol size, shape, type, composition, and other factors; it is important to apply the appropriate LR to calculate the extinction coefficient (Kovalev and Eichinger, 2004; Cao et al., 2019).

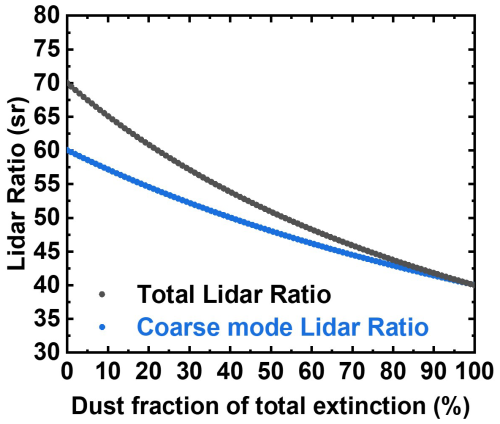

In Korea, due to geographical characteristics, dust and pollution are often mixed, and a wide variety of particle types exist. Therefore, LR research has been conducted on various particle types (Noh et al., 2007, 2008, 2011; Shin et al., 2015). We use the method described by Groß et al. (2011) for calculating LRs when two particle types are mixed. The total LR and coarse-mode LR, which are calculated using this method, are applied to the backscatter coefficients.

Depending on the fraction of dust, the extinction coefficients for a mixture of two aerosol types can be expressed as follows:

where α represents the total extinction coefficient, α1 is the extinction coefficient of component 1, α2 is the extinction coefficient due to component 2, and x can be expressed as . To determine the proportion of dust, the dust ratio (RD) is calculated using the depolarization ratio (δP) at 532 nm, which represents the non-sphericity of particles, as shown in Eq. (11):

where δ1 and δ2 represent the depolarization ratios of pure-dust particles and spherical aerosols, respectively. For the calculations in this study, δ1 and δ2 are set to 0.32 and 0.02, respectively (Shimizu et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008; Freudenthaler et al., 2009; Tesche et al., 2009; Nishizawa et al., 2011).

The LR for a mixture of two aerosol types can be expressed as follows:

where S1 and S2 represent the LRs of the two aerosol components considered in a mixture; specifically, S1 corresponds to dust, while S2 corresponds to pollution particles within the total LR. x represents the proportion of the total extinction coefficient accounted for by the extinction coefficient of component 1, which is dust. Furthermore, when calculating the coarse-mode LR, component 1 is set to dust, and component 2 is set to coarse-mode aerosol. In the coarse-mode LR, x represents the proportion of the coarse-mode particle extinction coefficient accounted for by the dust extinction coefficient of component 1.

In this study, we established the range of LRs based on the research conducted by Shin et al. (2015) in Gwangju, South Korea. Based on previous LR studies conducted in Korea, we assumed an LR (S1) of 40 sr for dust and an LR (S2) of 70 sr for pollution particles in this study. An LR (S1) of 40 sr for dust and an LR (S2) of 60 sr for coarse-mode particles are assumed and applied in the calculations (Fig. 1).

The calculated RD is inputted as the x value to determine the total extinction coefficient; the proportion of dust within coarse-mode particles is used to calculate the x value. The x value is applied to Eqs. (10) and (12) to calculate the total LR and coarse-mode LR, respectively. The calculated LRs are applied to the total backscatter coefficients and coarse-mode backscatter coefficients to calculate the total extinction coefficients and coarse-mode extinction coefficients, respectively. Afterwards, the fine-mode extinction coefficients are obtained by subtracting the coarse-mode extinction coefficients from the total extinction coefficients. The total, coarse-mode, and fine-mode extinction coefficients are divided by the mass concentrations of PM10, PM2.5−10, and PM2.5, respectively, to calculate the MEE10, MEE2.5−10, and MEE2.5 (Eq. 13):

2.4 Mann–Kendall test and Sen's slope

The slope of all trend lines in this study is obtained through simple linear regression analysis. In addition, we employ the Mann–Kendall test (MK test) and calculate Sen's slope to statistically confirm the accuracy of MEE trends (Mann, 1945; Kendall, 1957; Sen, 1968). The MK test is a non-parametric statistical test used to determine the occurrence of an increasing or decreasing trend in time series data; however, it does not provide information about the rate of change in the trend. By calculating the Sen's slope, it is possible to assume a linear trend in data and estimate the slope of the trend over time. The MK test is used to determine whether the null hypothesis (no trend) or an alternative hypothesis (a clear trend) is more appropriate. These hypotheses are determined based on z scores and p values. If is greater than 1.96, the alternative hypothesis is accepted at a 95 % confidence level; however, if is greater than 2.57, the alternative hypothesis is accepted at a 99 % confidence level. Additionally, the sign of the z scores can be used to determine an increasing or decreasing trend. A p value below 0.05 is considered statistically significant, indicating a meaningful result.

3.1 Visibility and PM concentration trends

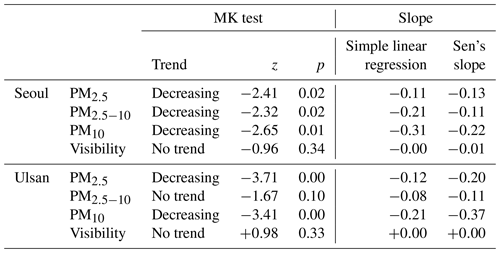

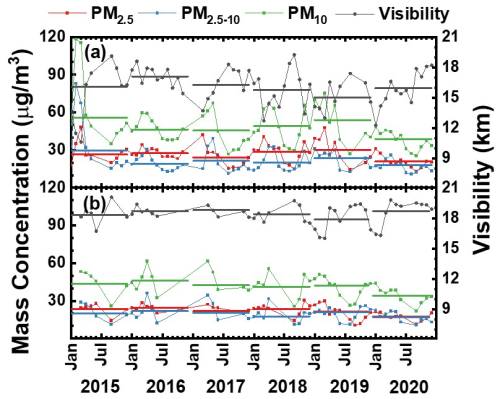

Figure 2 and Table 1 show the monthly values in PM2.5, PM2.5−10, and PM10 concentrations with the visibility across Seoul and Ulsan; consistent with the findings of previous studies, the monthly PM mass concentrations in both cities are higher in winter and spring and lower in summer and autumn (Kim, 2020; Allabakash et al., 2022). The monthly PM10 concentration exhibits a decreasing trend in both cities; the monthly PM10 concentration decreases by −0.31 µg m−3 per month in Seoul and −0.21 µg m−3 per month in Ulsan. However, the extent of the decrease in the monthly PM2.5 and PM2.5−10 concentrations in Seoul and Ulsan differ depending on particle size. The PM2.5 concentration in Seoul decreases by −0.11 µg m−3 per month, while the PM2.5−10 concentration decreases by −0.21 µg m−3 per month. The reduction in the PM mass concentration of coarse-mode particles (PM2.5−10) is greater than that of fine-mode particles (PM2.5). In Ulsan, the monthly PM2.5 concentration decreases at a rate of −0.12 µg m−3 per month, and the PM2.5−10 concentration decreases at a rate of −0.08 µg m−3 per month. However, the monthly visibility in Ulsan and Seoul does not change, showing −0.00 and +0.00 km per month, respectively. Through these monthly trends, it can be observed that despite the decrease in PM mass concentrations, the visibility in Seoul and Ulsan does not improve.

Figure 2Yearly and monthly particulate matter (PM) mass concentrations and visibility in (a) Seoul and (b) Ulsan.

These results can also be confirmed through the MK test (Table 1). In the case of PM2.5, a decreasing trend is confirmed in both regions. The p values in the PM2.5 trends in both regions are all smaller than 0.05, indicating statistically significant decreasing trends. In the case of PM2.5−10, Seoul shows a decreasing trend, unlike Ulsan. The z score of PM2.5−10 in Seoul is −2.32, showing a confidence level of 95 %. In PM10, the z scores of both regions are above 2.57, showing a decreasing trend at the 99 % confidence level. However, despite the decreasing trend in PM mass concentration, statistical analysis does not reveal any significant trends in visibility for Seoul and Ulsan. The z scores of the two regions are lower than 1.96, and the p values are also greater than 0.05, showing no statistical significance.

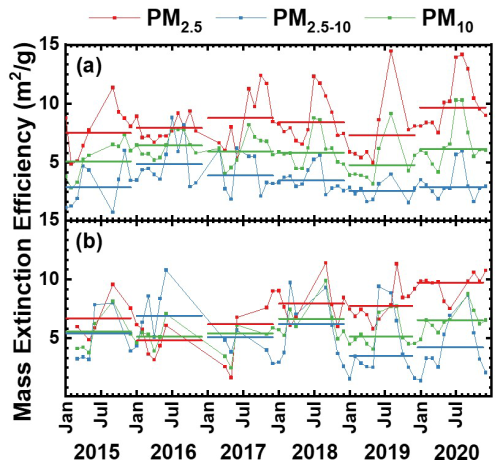

3.2 MEE trends

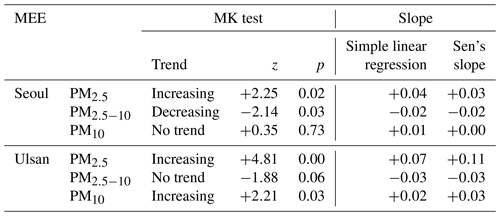

Figure 3 and Table 2 show the monthly average MEE and the monthly MEE trend from 2015 to 2020. The PM2.5 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan significantly increases, by +0.04 and +0.07 m2 g−1 per month, respectively. In contrast, the PM2.5−10 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan exhibits a decreasing trend; it decreases by −0.02 and −0.03 m2 g−1 per month, respectively. At the same PM mass concentration, the extent of light extinction by coarse-mode particles (PM2.5−10) in Seoul and Ulsan steadily decreases, whereas the light extinction by fine-mode particles (PM2.5) continues to increase, as evidenced by the monthly average MEE trends.

The monthly average MEE trends based on particle size are also confirmed by the results of the MK test (Table 2). The z scores of the PM2.5 MEE in Seoul (+2.25) exceed 1.96, indicating an increasing trend at a 95 % confidence level, and the z scores of the PM2.5 MEE in Ulsan (+4.81) exceed 2.57, indicating an increasing trend at a 99 % confidence level; moreover, the p values are all below 0.05, confirming the significance of the increasing trend. The z scores of the PM2.5−10 MEE in Seoul are −2.14, indicating a decreasing trend at a 95 % confidence level; additionally, the p values are below 0.05, confirming the statistical significance of such a decreasing trend. However, the z scores of the PM2.5−10 MEE in Ulsan are −1.88, indicating that the z score is below 1.96. It means that there is no statistically clear trend. The z score of the PM10 MEE in Seoul does not exhibit a distinct trend; however, the z score and p value of the PM10 MEE in Ulsan are +2.21 and 0.03, respectively, indicating an increasing trend at a 95 % confidence level. Therefore, in both Seoul and Ulsan, the MEE of fine-mode particles (PM2.5) exhibits a significant increasing trend, while that of coarse-mode particles (PM2.5−10) in Seoul demonstrates a significant decreasing trend. Furthermore, we conducted an analysis of seasonal trends in both Seoul and Ulsan. However, the seasonal trends did not reveal any significant differences compared to the monthly trends already presented in this study.

As previously mentioned, the PM mass concentration of coarse-mode particles (PM2.5−10) predominantly decreases in Seoul compared to that of fine-mode particles (PM2.5); however, the visibility in Seoul does not improve (−0.00 km per month). The light extinction in Seoul is predominantly caused by fine-mode particles (PM2.5). Additionally, the monthly trend in PM2.5 MEE in Seoul is +0.04 m2 g−1, indicating an increase in light extinction caused by fine particles, whereas the light extinction from PM2.5−10 MEE exhibits a decreasing trend of −0.02 m2 g−1. Therefore, despite the overall decrease in PM mass concentration, the visibility in Seoul does not improve due to the high extinction efficiency and increasing trend in fine-mode particles. In Ulsan, although the change in PM2.5−10 mass concentration is not significant (−0.08 µg m−3 per month), the PM2.5 mass concentration significantly decreases (−0.12 µg m−3 per month), statistically indicating a reduction. However, the visibility in Ulsan does not improve, showing a rate of +0.00 km per month. Therefore, despite the decrease in PM2.5 mass concentration, the significant monthly increase in PM2.5 MEE (+0.07 m2 g−1 per month) likely impacts the visibility in Ulsan. The observed monthly changes in MEE based on particle size in Seoul and Ulsan suggest that the characteristics of particles affecting light extinction vary depending on particle size. These changes are similar to the results found by Joo et al. (2022), who identified an increasing trend in PM2.5 MEE in Seoul (+0.05 m2 g−1 per month) through visibility data.

3.3 Analysis of the causes of the increasing PM2.5 MEE trends

An increase in relative humidity and changes in particle size and composition contribute to the increase in MEE. An increase in relative humidity induces particle hygroscopic growth, thereby influencing the extinction coefficient (Zieger et al., 2011; Sabetghadam and Ahmadi-Givi, 2014; Qu et al., 2015; Dawson et al., 2020; Ting et al., 2022). Since a beta-radiation attenuation monitor (BAM) is used in South Korea to measure PM mass concentrations by removing humidity (Baek, 2022), the influence of increased relative humidity on PM mass concentration measurements may be less than that of the extinction coefficient, suggesting that the increase in relative humidity may influence the increase in MEE. For instance, Cheng-Cai et al. (2013) reported an increase in MEE with increasing relative humidity in Beijing, China, regardless of the season. Additionally, Liu et al. (2020) attributed the higher MEE in eastern China in 2018 than that in 2013 to increased relative humidity and the amount of nitrates.

Even with the same relative humidity, the extent to which aerosols absorb water varies depending on the size and composition of the particles; it can change the degree of light extinction, as particles grow larger than dry particles (Singh and Dey, 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Titos et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2019). Additionally, even with the same PM mass concentration in the atmosphere, a reduction in particle size can lead to an increased degree of light scattering, resulting in a larger MEE value (Zhou et al., 2019). Differences in hygroscopic growth are influenced by not only particle size but also particle composition, in which particles are classified into hydrophilic and hydrophobic species (Chen et al., 2014). Hydrophilic species include secondary inorganic compounds (e.g., sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) and sea salt, while hydrophobic species include dust and black carbon. Both hygroscopic growth, which increases the particle size and scattering cross-section under high humidity, and the presence of smaller particles, which scatter light more efficiently per unit of mass, contribute to the increase in MEE.

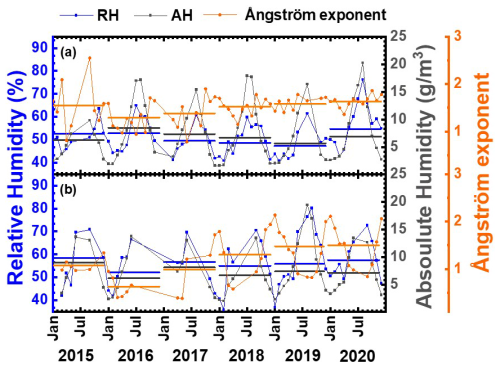

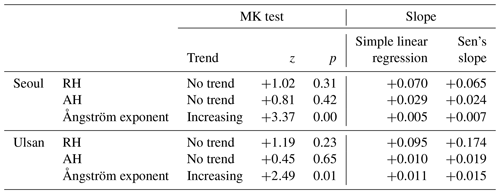

In this study, changes in particle size and humidity are examined to determine the impact of humidity on MEE. Figure 4 and Table 3 show the monthly average trends in the Ångström exponent and relative and absolute humidity in Seoul and Ulsan from 2015 to 2020. The monthly average trends in relative humidity in Seoul and Ulsan are +0.070 and +0.095 % per month, respectively. The relative humidity in Seoul and Ulsan exhibits an increasing trend, although it is not pronounced. The monthly average absolute humidity in Seoul and Ulsan slightly increases, by +0.029 and +0.010 g m−3 per month, respectively. From the monthly change trends in relative and absolute humidity in both cities, no distinct trends are observed that could significantly impact MEE. In the MK test results shown in Table 3, the z scores are all lower than 1.96, and the p value is also higher than 0.05, indicating that the humidity in both regions does not have statistically significant trends.

To gain information about particle size, which can be another factor influencing MEE changes, Ångström exponent values are utilized (Ångström, 1929). Generally, a higher Ångström exponent value indicates that there are relatively more fine-mode particles in the atmosphere. Fu-Qi et al. (2005) confirmed the effect of particle size on MEE by confirming that MEE increases as the Ångström exponent value increases. The Ångström exponent in Seoul and Ulsan exhibits a clear increasing trend of +0.03 and +0.02 per month, respectively. The increasing trend in the Ångström exponent in Seoul and Ulsan is statistically significant according to the MK test (Table 3). The z score of the Ångström exponent in Seoul (+3.37) is greater than 2.57, indicating an increase in the Ångström exponent at a confidence level of over 99 %. The z score of the Ångström exponent in Ulsan (+2.49) is greater than 1.96, indicating an increase in the Ångström exponent at a confidence level of over 95 %. The p values of the Ångström exponent in Seoul and Ulsan are 0.00 and 0.01, respectively, which are lower than 0.05, confirming the statistical significance of the trend. In contrast, neither the z scores nor the p values of relative and absolute humidity are statistically significant; thus, the influence of humidity on the increasing or decreasing trend in MEE could not be confirmed. Using AERONET data, Lee and Bae (2021) and Shin et al. (2023) reported an increase in the Ångström exponent in Seoul, South Korea. Their results are consistent with the trends in the Ångström exponent derived from the lidar measurements analyzed in this study. The increasing trend in the Ångström exponent in Seoul and Ulsan indicates a relative increase in the proportion of smaller particles compared to larger ones. It is believed that the Ångström exponent has influenced the increase in PM2.5 MEE values in Seoul and Ulsan.

Figure 4Yearly and monthly average Ångström exponents and relative and absolute humidity in (a) Seoul and (b) Ulsan.

Table 3Mann–Kendall test and slopes for monthly averages of relative humidity, absolute humidity, and the Ångström exponent.

RH – relative humidity; AH – absolute humidity.

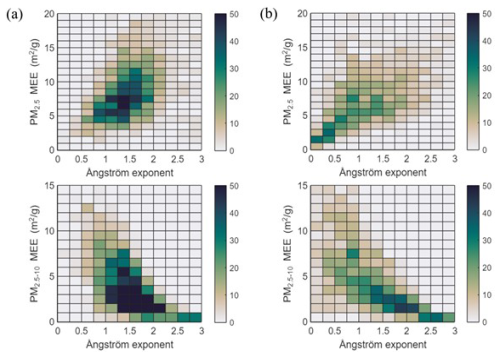

In this study, we determine that changes in the Ångström exponent, which imply changes in particle size, influence the increase in PM2.5 MEE. Figure 5 shows the correlation between the Ångström exponent and both PM2.5 MEE and PM2.5−10 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan. Examining Fig. 5, it is evident that the Ångström exponent in Seoul and Ulsan correlates with PM2.5 MEE and PM2.5−10 MEE. As demonstrated in both Figs. 4 and 5, an increase in the Ångström exponent in Seoul and Ulsan is associated with an increase in PM2.5 MEE and a decrease in PM2.5−10 MEE from 2015 to 2020. Figure 6 shows the correlation between the relative humidity and both PM2.5 MEE and PM2.5−10 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan. In the case of relative humidity in Fig. 6, it is confirmed that an increase in the value can affect the increase in PM2.5−10 MEE. However, as confirmed by the MK test in Table 3, no statistically significant trend for humidity can be found in either region, and only the Ångström exponent in Ulsan and Seoul shows a significant increasing trend. It confirms that the increase in the Ångström exponent rather than relative humidity influences the light extinction characteristics of particles in Seoul and Ulsan.

Figure 5The correlation between the Ångström exponent and both PM2.5 MEE and PM2.5−10 MEE in (a) Seoul and (b) Ulsan.

The Ångström exponent calculated in this study is the Ångström exponent of all atmospheric particles, including both coarse- and fine-mode particles. Therefore, based on the Ångström exponent alone, it cannot be concluded that the particle size of PM2.5 is getting smaller over time. However, the high correlation between the Ångström exponent and PM2.5 MEE indicates that the size of PM2.5 particles is decreasing, which is the largest contributing factor causing the increase in the Ångström exponent. The findings of Shin et al. (2023), who used AERONET data and reported an increase in the Ångström exponent of fine-mode particles in major northeast Asian cities such as Seoul, Beijing, and Osaka, along with the results presented by Shin et al. (2022a), which revealed an increase in the Ångström exponent of fine-mode particles in northeast Asia from 2.57 % in 2001 to 11.92 % in 2018, corroborate the results of this study. Considering the results of previous studies, the increases in the Ångström exponent and PM2.5 MEE observed in this study are presumed to be caused by the decrease in the size of fine-mode particles.

3.4 PM2.5 MEE trend in northeast Asia

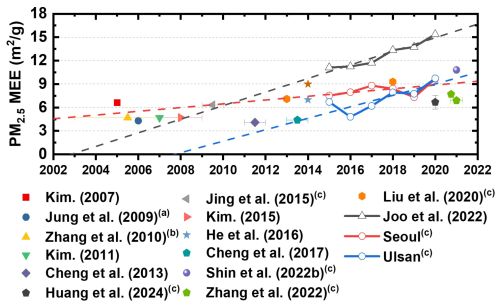

There have been several cases in northeast Asia wherein the improvement in visibility is not significant compared to the reduction in PM2.5 (Xu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Jeong et al., 2022). In this study, the overall PM2.5 MEE trend in northeast Asia is confirmed by comparing the PM2.5 MEE values reported in studies conducted in northeast Asia to the annual trend in PM2.5 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan, as reported in this study (Fig. 7). Except for Jing et al. (2015), Zhang et al. (2022), Huang et al. (2024), Liu et al. (2020), and Shin et al. (2022b), all previous studies reported the PM2.5 MEE value at a wavelength of 550 nm. Jing et al. (2015) and Zhang et al. (2022) used 525 nm. Huang et al. (2024), Liu et al. (2020), and Shin et al. (2022b) used wavelengths of 520, 589, and 534 nm, respectively. The increasing trend in PM2.5 MEE at 532 nm, which is confirmed in this study, is consistent with the results of previous studies. Using camera images, Shin et al. (2022b) reported high PM2.5 MEE values (10.8 ± 6.9 m2 g−1) in Daejeon, South Korea, in 2021; these values were higher than the findings of previous studies conducted in northeast Asia. Joo et al. (2022) examined the PM2.5 MEE trends in eight regions of South Korea using visibility data; while their findings showed higher values than those observed in this study, the increasing trend of MEE is similar.

Figure 7Comparison of PM2.5 mass extinction efficiency (MEE) values from previous studies in northeast Asia. (a) Estimated using a single scattering albedo of 0.8, according to the literature. (b) The mass ratio of PM2.5 to PM10 was set to 0.56, and relative humidity was set to 40 %, according to the literature. (c) Studies using wavelengths other than 550 nm.

Liu et al. (2020) attributed the increase in PM2.5 MEE in eastern China to an increase in nitrate proportions and relative humidity. However, Joo et al. (2022), who used visibility data to calculate PM2.5 MEE in South Korea, could not ascertain the exact causes of the increasing trend in MEE due to the lack of long-term information about particle size and composition. In this study, we utilize lidar data to calculate the Ångström exponent and assess changes in particle size, thereby recognizing the possibility that these size changes contribute to the increase in PM2.5 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan.

According to prior research conducted in northeast Asia, while the contributions of primary PM2.5 have decreased, the contribution of secondary PM2.5 has increased compared to its contribution in the past (Lang et al., 2017; Du et al., 2020). As the proportion of the primary components of PM2.5 has decreased and the proportion of smaller-sized secondary components has increased, the degree of light scattering by PM2.5 particles may have increased even though PM2.5 concentrations have decreased. In fact, the MEE of primary aerosols is lower than that of secondary aerosols (Wang et al., 2015; Du et al., 2022). The increase in the proportion of secondary aerosol might have affected the hygroscopic growth of particles, thereby influencing MEE. Li et al. (2021), in their study on the chemical species of PM2.5, confirmed that secondary pollutants, which are more prevalent in urban areas, cause greater hygroscopic growth. In contrast, primary combustion emissions were reported to exhibit less hygroscopic growth.

Additionally, changes in particle components that serve as precursors to secondary pollutants can also influence variations in light extinction. Jeong et al. (2022) reported that the minor improvement in visibility compared to the PM2.5 mass concentration in Seoul from 2012 to 2018 could be attributed to the increase in ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) due to a decrease in SOx and an increase in NOx. An increase in NOx, a precursor to secondary pollutants, can lead to an increase in NH4NO3. NH4NO3, compared to other components, has a greater degree of light extinction by particles, suggesting that it may have contributed to the increase in MEE (Liu et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2022). Although a more extensive long-term analysis is required to understand the causes of the increase in PM2.5 MEE in northeast Asia, the increasing trend in PM2.5 MEE and the enhanced light extinction by fine-mode particles are evident. Consequently, further research focusing on not just mass concentration but also changes in particle size, composition, and number concentration that can affect light extinction should be conducted in the future.

In this study, we utilized the AD-Net lidar data and PM mass concentrations to examine the trends in PM2.5, PM2.5−10, and PM10 MEE changes from 2015 to 2020 in Seoul and Ulsan. The results revealed that PM2.5 MEE exhibited an increasing trend in Seoul (+0.04 m2 g−1 per month) and Ulsan (+0.07 m2 g−1 per month). Meanwhile, PM2.5−10 MEE exhibited a decreasing trend in Seoul (−0.02 m2 g−1 per month) and Ulsan (−0.03 m2 g−1 per month). Therefore, in Seoul and Ulsan, the light extinction caused by coarse-mode particles (PM2.5−10) has decreased, whereas the light extinction caused by fine-mode particles (PM2.5) has increased. To further identify the causes of these trends, we examined the trends in relative and absolute humidity as well as the changes in the Ångström exponent. The monthly average relative humidity exhibited increasing trends in Seoul (+0.070 % per month) and Ulsan (+0.095 % per month). However, both relative humidity and absolute humidity were not statistically significant. The monthly average Ångström exponent significantly increased in Seoul (+0.005 per month) and Ulsan (+0.011 per month), suggesting that the particles have become smaller. The increasing trend in the Ångström exponent indicates that although the PM mass concentration has decreased, its effect on improving atmospheric visibility is negligible due to the increase in particles (PM2.5) with smaller particle sizes. Additionally, by comparing the annual average PM2.5 MEE in Seoul and Ulsan with the findings of previous studies conducted in northeast Asia, it is confirmed that PM2.5 MEE is generally increasing throughout northeast Asia. Therefore, despite the consistent decrease in PM mass concentration observed in previous studies across northeast Asia, the limited improvement in visibility can be attributed to an increase in the number concentration of smaller particles. Thus, to enable citizens to noticeably perceive a reduction in PM and to lower their anxiety about air pollution, effective strategies that go beyond mere policies aimed at reducing PM mass concentration must be implemented. Therefore, it is essential to enact policies and conduct related research aimed at mitigating the increasing concentration of smaller secondary particles in the atmosphere. However, in this study, we are unable to obtain long-term data on particle composition and, thus, could not determine the impact of compositional changes on MEE. Further research on MEE that considers changes in particle compositional characteristics is required.

Lidar data were provided by AD-Net (https://www-lidar.nies.go.jp/AD-Net/ncdf/, National Institute for Environmental, 2024). Lidar data for Seoul were provided by Seoul National University, under the supervision of Sang-Woo Kim (sangwookim@snu.ac.kr), and lidar data for Ulsan were provided by the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, under the supervision of Chang-Keun Song (cksong@unist.ac.kr). The PM mass concentration data were provided by the Korea Environment Corporation and are accessible through the AirKorea website at https://www.airkorea.or.kr/web/last_amb_hour_data?pMENU_NO=123 (Korea Environment Corporation, 2024).

Conceptualization and methodology – YN; formal analysis – SJ and TK; writing (original draft) – SJ and ND; manuscript review and editing – YN, MT, SJ, JS, and ND; and simulation – JS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the paper.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This research was supported by the Particulate Matter Management Specialized Graduate Program through the Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) funded by the Ministry of Environment (MOE) and by a grant (2023-MOIS-20024324) from the Ministry-Cooperation R&D Program of Disaster-Safety funded by the Ministry of Interior and Safety (MOIS, Korea).

This research was supported the by Particulate Matter Management Specialized Graduate Program through the Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) funded by the Ministry of Environment (MOE) and by a grant (grant no. 2023-MOIS-20024324) of the Ministry-Cooperation R&D Program of Disaster-Safety funded by the Ministry of Interior and Safety (MOIS, Korea).

This paper was edited by Jayanarayanan Kuttippurath and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Allabakash, S., Lim, S., Chong, K. S., and Yamada, T. J.: Particulate matter concentrations over South Korea: Impact of meteorology and other pollutants, Remote Sens., 14, 4849, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14194849, 2022.

An, Z., Huang, R. J., Zhang, R., Tie, X., Li, G., Cao, J., Zhou, W., Shi, Z., Han, Y., Gu, Z., and Ji, Y.: Severe haze in northern China: A synergy of anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric processes, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 8657–8666, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900125116, 2019.

Ångström, A.: On the atmospheric transmission of sun radiation and on dust in the air, Geogr. Ann., 11, 156–166, https://doi.org/10.1080/20014422.1929.11880498, 1929.

Bae, M., Kim, B. U., Kim, H. C., Kim, J., and Kim, S.: Role of emissions and meteorology in the recent PM2.5 changes in China and South Korea from 2015 to 2018, Environ. Pollut., 270, 116233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116233, 2021.

Baek, S. H.: Energy-efficient monitoring of fine particulate matter with tiny aerosol conditioner, Sensors (Basel), 22, 1950, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22051950, 2022.

Cao, N., Yang, S., Cao, S., Yang, S., and Shen, J.: Accuracy calculation for lidar ratio and aerosol size distribution by dual-wavelength lidar, Appl. Phys. A, 125, 1–10, 2019.

Chen, J., Zhao, C. S., Ma, N., and Yan, P.: Aerosol hygroscopicity parameter derived from the light scattering enhancement factor measurements in the North China Plain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 8105–8118, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-8105-2014, 2014.

Chen, J., Li, Z., Lv, M., Wang, Y., Wang, W., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Yan, X., Sun, Y., and Cribb, M.: Aerosol hygroscopic growth, contributing factors, and impact on haze events in a severely polluted region in northern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 1327–1342, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-1327-2019, 2019.

Cheng, Z., Wang, S., Jiang, J., Fu, Q., Chen, C., Xu, B., Yu, J., Fu, X., and Hao, J.: Long-term trend of haze pollution and impact of particulate matter in the Yangtze River Delta, China, Environ. Pollut., 182, 101–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.06.043, 2013.

Cheng, Z., Ma, X., He, Y., Jiang, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Sheng, L., Hu, J., and Yan, N.: Mass extinction efficiency and extinction hygroscopicity of ambient PM2.5 in urban China, Environ. Res., 156, 239–246, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.022, 2017.

Cheng-Cai, L., Xiu, H., Zhao-Ze, D., Kai-Hon Lau, A., and Ying, L.: Dependence of mixed aerosol light scattering extinction on relative humidity in Beijing and Hong Kong, Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 6, 117–121, https://doi.org/10.1080/16742834.2013.11447066, 2013.

Dawson, K. W., Ferrare, R. A., Moore, R. H., Clayton, M. B., Thorsen, T. J., and Eloranta, E. W.: Ambient aerosol hygroscopic growth from combined Raman lidar and HSRL, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, JD031708, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD031708, 2020.

De Marco, A., Proietti, C., Anav, A., Ciancarella, L., D'Elia, I., Fares, S., Fornasier, M. F., Fusaro, L., Gualtieri, M., Manes, F., Marchetto, A., Mircea, M., Paoletti, E., Piersanti, A., Rogora, M., Salvati, L., Salvatori, E., Screpanti, A., Vialetto, G., Vitale, M., and Leonardi, C.: Impacts of air pollution on human and ecosystem health, and implications for the National Emission Ceilings Directive: Insights from Italy, Environ. Int., 125, 320–333, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.064, 2019.

Du, A., Li, Y., Sun, J., Zhang, Z., You, B., Li, Z., Chen, C., Li, J., Qiu, Y., Liu, X., Ji, D., Zhang, W., Xu, W., Fu, P., and Sun, Y.: Rapid transition of aerosol optical properties and water-soluble organic aerosols in cold season in Fenwei Plain, Sci. Total Environ., 829, 154661, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154661, 2022.

Du, X. X., Shi, G. M., Zhao, T. L., Yang, F. M., Zheng, X. B., Zhang, Y. J., and Tan, Q. W.: Contribution of secondary particles to wintertime PM2.5 during 2015–2018 in a major urban area of the Sichuan Basin, Southwest China, Earth Space Sci., 7, EA001194, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EA001194, 2020.

Dubovik, O., Holben, B., Eck, T. F., Smirnov, A., Kaufman, Y. J., King, M. D., Tanré, D., and Slutsker, I.: Variability of absorption and optical properties of key aerosol types observed in worldwide locations, J. Atmos. Sci., 59, 590–608, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(2002)059<0590:VOAAOP>2.0.CO;2, 2002.

Freudenthaler, V., Esselborn, M., Wiegner, M., Heese, B., Tesche, M., Ansmann, A., Müller, D., Althausen, D., Wirth, M., Fix, A., Ehret, G., Knippertz, P., Toledano, C., Gasteiger, J., Garhammer, M., and Seefeldner, M.: Depolarization ratio profiling at several wavelengths in pure Saharan dust during SAMUM 2006, Tellus B, 61, 165–179, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2008.00396.x, 2009.

Fu-Qi, S., Jian-Guo, L., Ping-Hua, X., Yu-Jun, Z., Wen-Qing, L., Kuze, H., Cheng, L., Lagrosas, N., and Takeuchi, N.: Determination of aerosol extinction coefficient and mass extinction efficiency by DOAS with a flashlight source, Chinese Phys., 14, 2360–2364, https://doi.org/10.1088/1009-1963/14/11/037, 2005.

Gao, M., Liu, Z., Zheng, B., Ji, D., Sherman, P., Song, S., Xin, J., Liu, C., Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Xing, J., Jiang, J., Wang, Z., Carmichael, G. R., and McElroy, M. B.: China's emission control strategies have suppressed unfavorable influences of climate on wintertime PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing since 2002, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 1497–1505, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-1497-2020, 2020.

Geng, G., Xiao, Q., Zheng, Y., Tong, D., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, Q., He, K., and Liu, Y.: Impact of China's air pollution prevention and control action plan on PM2.5 chemical composition over eastern China, Sci. China Earth Sci., 62, 1872–1884, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-018-9353-x, 2019.

Groß, S., Tesche, M., Freudenthaler, V., Toledano, C., Wiegner, M., Ansmann, A., Althausen, D., and Seefeldner, M.: Characterization of Saharan dust, marine aerosols and mixtures of biomass-burning aerosols and dust by means of multi-wavelength depolarization and Raman lidar measurements during SAMUM 2, Tellus, 63, 706–724, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0889.2011.00556.x, 2011.

Hao, X., Li, J., Wang, H., Liao, H., Yin, Z., Hu, J., Wei, Y., and Dang, R.: Long-term health impact of PM2.5 under whole-year COVID-19 lockdown in China, Environ. Pollut., 290, 118118, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118118, 2021.

He, Q., Zhou, G., Geng, F., Gao, W., and Yu, W.: Spatial distribution of aerosol hygroscopicity and its effect on PM2.5 retrieval in East China, Atmos. Res., 170, 161–167, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2015.11.011, 2016.

Huang, W., Tan, J., Kan, H., Zhao, N., Song, W., Song, G., Chen, G., Jiang, L., Jiang, C., Chen, R., and Chen, B.: Visibility, air quality and daily mortality in Shanghai, China, Sci. Total Environ., 407, 3295–3300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.02.019, 2009.

Huang, X., Li, C., Pan, C., Zheng, W., Lin, G., Li, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Lei, Y., Ye, J., Ge, X., and Zhang, H.: Effects of significant emission changes on PM2.5 chemical composition and optical properties from 2019 to 2021 in a typical industrial city of eastern China, Atmos. Res., 301, 107287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2024.107287, 2024.

IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer): Outdoor air pollution a leading environmental cause of cancer deaths, Lyon/Geneva, 2 pp., https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr221_E.pdf (last access: 20 January 2025), 17 October 2013.

Jeong, J. I., Seo, J., and Park, R. J.: Compromised improvement of poor visibility due to PM chemical composition changes in South Korea, Remote Sens., 14, 5310, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14215310, 2022.

Jing, J., Wu, Y., Tao, J., Che, H., Xia, X., Zhang, X., Yan, P., Zhao, D., and Zhang, L.: Observation and analysis of near-surface atmospheric aerosol optical properties in urban Beijing, Particuology, 18, 144–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2014.03.013, 2015.

Joo, S., Dehkhoda, N., Shin, J., Park, M. E., Sim, J., and Noh, Y.: A study on the long-term variations in mass extinction efficiency using visibility data in South Korea, Remote Sens., 14, 1592, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14071592, 2022.

Jung, J., Lee, H., Kim, Y. J., Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Gu, J., and Fan, S.: Aerosol chemistry and the effect of aerosol water content on visibility impairment and radiative forcing in Guangzhou during the 2006 Pearl River Delta campaign, J. Environ. Manage., 90, 3231–3244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.04.021, 2009.

Jung, W.: Environmental challenges and cooperation in NorthEast Asia, Focus Asia Perspect. Anal., 16, 1–11, 2016.

Kendall, M. G.: Rank correlation methods, Biometrika, 44, 298, https://doi.org/10.2307/2333282, 1957.

Kim, H.: Seasonal impacts of particulate matter levels on bike sharing in Seoul, South Korea, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 17, 3999, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113999, 2020.

Kim, K. W.: Physico-chemical characteristics of visibility impairment by airborne pollen in an urban area, Atmos. Environ., 41, 3565–3576, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.12.054, 2007.

Kim, K. W.: Time-resolved chemistry measurement to determine the aerosol optical properties using PIXE analysis, J. Korean Phy. Soc., 59, 189–195, https://doi.org/10.3938/jkps.59.189, 2011.

Kim, K. W.: Optical properties of size-resolved aerosol chemistry and visibility variation observed in the urban site of Seoul, Korea, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 15, 271–283, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2013.11.0347, 2015.

Korea Environment Corporation: PM Mass Concentration Data, AirKorea [data set], https://www.airkorea.or.kr/web/last_amb_hour_data?pMENU_NO=123 (last access: 16 February 2024), 2024.

Kovalev, V. A. and Eichinger, W. E.: Elastic lidar: Theory, practice, and analysis methods, John Wiley & Sons, 640 pp., https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Elastic+Lidar:+Theory,+Practice,+and+Analysis+Methods-p-9780471201717 (last access: 20 January 2025), 2004.

Lang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y., Cheng, S., Chen, D., Guo, X., Chen, S., Li, X., Xing, X., and Wang, H.: Trends of PM2.5 and chemical composition in Beijing, 2000–2015, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 17, 412–425, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2016.07.0307, 2017.

Lee, K. H. and Bae, M. S.: Discrepancy between scientific measurement and public anxiety about particulate matter concentrations, Sci. Total Environ., 760, 143980, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143980, 2021.

Li, J., Zhang, Z., Wu, Y., Tao, J., Xia, Y., Wang, C., and Zhang, R.: Effects of chemical compositions in fine particles and their identified sources on hygroscopic growth factor during dry season in urban Guangzhou of South China, Sci. Total Environ., 801, 149749, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149749, 2021.

Li, Y., Huang, H. X. H., Griffith, S. M., Wu, C., Lau, A. K. H., and Yu, J. Z.: Quantifying the relationship between visibility degradation and PM2.5 constituents at a suburban site in Hong Kong: Differentiating contributions from hydrophilic and hydrophobic organic compounds, Sci. Total Environ., 575, 1571–1581, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.082, 2017.

Li, Z., Wang, Y., Guo, J., Zhao, C., Cribb, M. C., Dong, X., Fan, J., Gong, D., Huang, J., Jiang, M., Jiang, Y., Lee, S.-S., Li, H., Li, J., Liu, J., Qian, Y., Rosenfeld, D., Shan, S., Sun, Y., Wang, H., Xin, J., Yan, X., Yang, X., Yang, X., Zhang, F., and Zheng, Y.: East Asian study of tropospheric aerosols and their impact on regional clouds, precipitation, and climate (EAST-AIR CPC), J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 124, 13026–13054, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030758, 2019.

Liao, W., Zhou, J., Zhu, S., Xiao, A., Li, K., and Schauer, J. J.: Characterization of aerosol chemical composition and the reconstruction of light extinction coefficients during winter in Wuhan, China, Chemosphere, 241, 125033, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125033, 2020.

Liu, F., Tan, Q., Jiang, X., Yang, F., and Jiang, W.: Effects of relative humidity and PM2.5 chemical compositions on visibility impairment in Chengdu, China, J. Environ. Sci. (China), 86, 15–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2019.05.004, 2019.

Liu, H., Wang, C., Zhang, M., and Wang, S.: Evaluating the effects of air pollution control policies in China using a difference-in-differences approach, Sci. Total Environ., 845, 157333, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157333, 2022.

Liu, J., Ren, C., Huang, X., Nie, W., Wang, J., Sun, P., Chi, X., and Ding, A.: Increased aerosol extinction efficiency hinders visibility improvement in eastern China, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, GL090167, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL090167, 2020.

Liu, X., Gu, J., Li, Y., Cheng, Y., Qu, Y., Han, T., Wang, J., Tian, H., Chen, J., and Zhang, Y.: Increase of aerosol scattering by hygroscopic growth: Observation, modeling, and implications on visibility, Atmos. Res., 132–133, 91–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2013.04.007, 2013.

Liu, Z., Omar, A., Vaughan, M., Hair, J., Kittaka, C., Hu, Y., Powell, K., Trepte, C., Winker, D., Hostetler, C., Ferrare, R., and Pierce, R.: CALIPSO lidar observations of the optical properties of Saharan dust: A case study of long-range transport, J. Geophys. Res., 113, D7, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008878, 2008.

Mann, H. B.: Nonparametric tests against trend, Econometrica, 13, 245–259, https://doi.org/10.2307/1907187, 1945.

National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES): Asian Dust and Aerosol Lidar Observation Network (AD-Net), https://www-lidar.nies.go.jp/AD-Net/ncdf/ (last access: 10 March 2024), 2024.

Nishizawa, T., Sugimoto, N., Matsui, I., Shimizu, A., and Okamoto, H.: Algorithms to retrieve optical properties of three component aerosols from two-wavelength backscatter and one-wavelength polarization lidar measurements considering nonsphericity of dust, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 112, 254–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2010.06.002, 2011.

Noh, Y. M., Kim, Y. J., Choi, B. C., and Murayama, T.: Aerosol lidar ratio characteristics measured by a multi-wavelength Raman lidar system at Anmyeon Island, Korea, Atmos. Res., 86, 76–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2007.03.006, 2007.

Noh, Y. M., Kim, Y. J., and Müller, D.: Seasonal characteristics of lidar ratios measured with a Raman lidar at Gwangju, Korea in spring and autumn, Atmos. Environ., 42, 2208–2224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.11.045, 2008.

Noh, Y. M., Müller, D., Mattis, I., Lee, H., and Kim, Y. J.: Vertically resolved light-absorption characteristics and the influence of relative humidity on particle properties: Multiwavelength Raman lidar observations of East Asian aerosol types over Korea, J. Geophys. Res., 116, D6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD014873, 2011.

O'Neill, N. T., Ranjbar, K., Ivǎnescu, L., Eck, T. F., Reid, J. S., Giles, D. M., Pérez-Ramírez, D., and Chaubey, J. P.: Relationship between the sub-micron fraction (SMF) and fine-mode fraction (FMF) in the context of AERONET retrievals, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 16, 1103–1120, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-16-1103-2023, 2023.

Qu, W. J., Wang, J., Zhang, X. Y., Wang, D., and Sheng, L. F.: Influence of relative humidity on aerosol composition: Impacts on light extinction and visibility impairment at two sites in coastal area of China, Atmos. Res., 153, 500–511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2014.10.009, 2015.

Sabetghadam, S. and Ahmadi-Givi, F.: Relationship of extinction coefficient, air pollution, and meteorological parameters in an urban area during 2007 to 2009, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 21, 538–547, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-013-1901-9, 2014.

Schuster, G. L., Dubovik, O., and Holben, B. N.: Angstrom exponent and bimodal aerosol size distributions, J. Geophys. Res., 111, D7, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006328, 2006.

Sen, P. K.: Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall's tau, J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 63, 1379–1389, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1968.10480934, 1968.

Shen, Z., Cao, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Huang, R.-J., Liu, S., Zhao, Z., Zhu, C., Lei, Y., Xu, H., and Zheng, C.: Retrieving historical ambient PM2.5 concentrations using existing visibility measurements in Xi'an, Northwest China, Atmos. Environ., 126, 15–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.11.040, 2016.

Shimizu, A., Sugimoto, N., Matsui, I., Arao, K., Uno, I., Murayama, T., Kagawa, N., Aoki, K., Uchiyama, A., and Yamazaki, A.: Continuous observations of Asian dust and other aerosols by polarization lidars in China and Japan during ACE-Asia, J. Geophys. Res., 109, D19, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD003253, 2004.

Shimizu, A., Nishizawa, T., Jin, Y., Kim, S. W., Wang, Z., Batdorj, D., and Sugimoto, N.: Evolution of a lidar network for tropospheric aerosol detection in East Asia, Opt. Eng., 56, 031219–031219, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.OE.56.3.031219, 2016.

Shin, J., Sim, J., Dehkhoda, N., Joo, S., Kim, T., Kim, G., Müller, D., Tesche, M., Shin, S., Shin, D., and Noh, Y.: Long-term variation study of fine-mode particle size and regional characteristics using AERONET data, Remote Sens., 14, 4429, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14184429, 2022a.

Shin, J., Kim, D., and Noh, Y.: Estimation of aerosol extinction coefficient using camera images and application in mass extinction efficiency retrieval, Remote Sens., 14, 1224, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14051224, 2022b.

Shin, J., Shin, D., Müller, D., and Noh, Y.: Long-term analysis of AOD separated by aerosol type in East Asia, Atmos. Environ., 310, 119957, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119957, 2023.

Shin, S.-K., Müller, D., Lee, C., Lee, K. H., Shin, D., Kim, Y. J., and Noh, Y. M.: Vertical variation of optical properties of mixed Asian dust/pollution plumes according to pathway of air mass transport over East Asia, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 6707–6720, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-6707-2015, 2015.

Singh, A. and Dey, S.: Influence of aerosol composition on visibility in megacity Delhi, Atmos. Environ., 62, 367–373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.08.048, 2012.

Tesche, M., Ansmann, A., Müller, D., Althausen, D., Engelmann, R., Freudenthaler, V., and Groß, S.: Vertically resolved separation of dust and smoke over Cape Verde using multiwavelength Raman and polarization lidars during Saharan Mineral Dust Experiment 2008, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 114, D13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD011862, 2009.

Ting, Y. C., Young, L. H., Lin, T. H., Tsay, S. C., Chang, K. E., and Hsiao, T. C.: Quantifying the impacts of PM2.5 constituents and relative humidity on visibility impairment in a suburban area of eastern Asia using long-term in-situ measurements, Sci. Total Environ., 818, 151759, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151759, 2022.

Titos, G., Cazorla, A., Zieger, P., Andrews, E., Lyamani, H., Granados-Muñoz, M. J., Olmo, F. J., and Alados-Arboledas, L.: Effect of hygroscopic growth on the aerosol light-scattering coefficient: A review of measurements, techniques and error sources, Atmos. Environ., 141, 494–507, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.07.021, 2016.

Vaisala, O.: Humidity conversion formulas, Calculation formulas for humidity, 17 pp., https://web.archive.org/web/20200212215746im_/https://www.vaisala.com/en/system/files?file=documents/Humidity_Conversion_Formulas_B210973EN.pdf (last access: 20 January 2025), 2013.

Van Donkelaar, A., Martin, R. V., Brauer, M., Hsu, N. C., Kahn, R. A., Levy, R. C., Lyapustin, A., Sayer, A. M., and Winker, D. M.: Global estimates of fine particulate matter using a combined geophysical-statistical method with information from satellites, models, and monitors, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 3762–3772, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05833, 2016.

Veselovskii, I., Kolgotin, A., Griaznov, V., Müller, D., Franke, K., and Whiteman, D. N.: Inversion of multiwavelength Raman lidar data for retrieval of bimodal aerosol size distribution, Appl. Opt., 43, 1180–1195, https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.43.001180, 2004.

Wang, Q., Sun, Y., Jiang, Q., Du, W., Sun, C., Fu, P., and Wang, Z.: Chemical composition of aerosol particles and light extinction apportionment before and during the heating season in Beijing, China, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 120, 12708–12722, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023871, 2015.

Won, J. S., Kim, H., and Kim, S. G.: A study on the preliminary plan for environmental health in Seoul, Korea, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19, 16611, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416611, 2022.

Xiao, Q., Geng, G., Liang, F., Wang, X., Lv, Z., Lei, Y., Huang, X., Zhang, Q., Liu, Y., and He, K.: Changes in spatial patterns of PM2.5 pollution in China 2000–2018: Impact of clean air policies, Environ. Int., 141, 105776, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105776, 2020.

Xie, C., Nishizawa, T., Sugimoto, N., Matsui, I., and Wang, Z.: Characteristics of aerosol optical properties in pollution and Asian dust episodes over Beijing, China, Appl. Opt., 47, 4945–4951, https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.47.004945, 2008.

Xie, P. and Liao, H.: The impacts of changes in anthropogenic emissions over China on PM2.5 concentrations in South Korea and Japan during 2013–2017, Front. Environ. Sci., 10, 31, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.841285, 2022.

Xu, W., Kuang, Y., Bian, Y., Liu, L., Li, F., Wang, Y., Xue, B., Luo, B., Huang, S., Yuan, B., Zhao, P., and Shao, M.: Current challenges in visibility improvement in southern China, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 7, 395–401, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00274, 2020.

Yuan, C. S., Lee, C. G., Liu, S. H., Chang, J. C., Yuan, C., and Yang, H. Y.: Correlation of atmospheric visibility with chemical composition of Kaohsiung aerosols, Atmos. Res., 82, 663–679, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2006.02.027, 2006.

Yue, H., He, C., Huang, Q., Yin, D., and Bryan, B. A.: Stronger policy required to substantially reduce deaths from PM2.5 pollution in China, Nat. Commun., 11, 1462, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15319-4, 2020.

Yue, X., Unger, N., Harper, K., Xia, X., Liao, H., Zhu, T., Xiao, J., Feng, Z., and Li, J.: Ozone and haze pollution weakens net primary productivity in China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 6073–6089, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-6073-2017, 2017.

Zhai, S., Jacob, D. J., Wang, X., Shen, L., Li, K., Zhang, Y., Gui, K., Zhao, T., and Liao, H.: Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) trends in China, 2013–2018: separating contributions from anthropogenic emissions and meteorology, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 11031–11041, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-11031-2019, 2019.

Zhang, Q. and Geng, G.: Impact of clean air action on PM2.5 pollution in China, Sci. China Earth Sci., 62, 1845–1846, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-019-9531-4, 2019.

Zhang, Q., Zheng, Y., Tong, D., Shao, M., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Xu, X., Wang, J., He, H., Liu, W., Ding, Y., Lei, Y., Li, J., Wang, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Cheng, J., Liu, Y., Shi, Q., Yan, L., Geng, G., Hong, C., Li, M., Liu, F., Zheng, B., Cao, J., Ding, A., Gao, J., Fu, Q., Huo, J., Liu, B., Liu, Z., Yang, F., He, K., and Hao, J.: Drivers of improved PM2.5 air quality in China from 2013 to 2017, P. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 24463–24469, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1907956116, 2019.

Zhang, Q., Qin, L., Zhou, Y., Jia, S., Yao, L., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, L.: Evaluation of Extinction Effect of PM2.5 and Its Chemical Components during Heating Period in an Urban Area in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, Atmosphere, 13, 403, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13030403, 2022.

Zhang, Q. H., Zhang, J. P., and Xue, H. W.: The challenge of improving visibility in Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 7821–7827, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-7821-2010, 2010.

Zhou, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Liu, S., Wang, M., Tian, J., Zhu, C., Huang, R., Zhang, Q., Zhang, T., Zhou, J., Dai, W., and Cao, J.: Exploring the impact of chemical composition on aerosol light extinction during winter in a heavily polluted urban area of China, J. Environ. Manage., 247, 766–775, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.100, 2019.

Zieger, P., Weingartner, E., Henzing, J., Moerman, M., de Leeuw, G., Mikkilä, J., Ehn, M., Petäjä, T., Clémer, K., van Roozendael, M., Yilmaz, S., Frieß, U., Irie, H., Wagner, T., Shaiganfar, R., Beirle, S., Apituley, A., Wilson, K., and Baltensperger, U.: Comparison of ambient aerosol extinction coefficients obtained from in-situ, MAX-DOAS and LIDAR measurements at Cabauw, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 2603–2624, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-2603-2011, 2011.