the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

An aldehyde as a rapid source of secondary aerosol precursors: theoretical and experimental study of hexanal autoxidation

Siddharth Iyer

Avinash Kumar

Prasenjit Seal

Aldehydes are common constituents of natural and polluted atmospheres, and their gas-phase oxidation has recently been reported to yield highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) that are key players in the formation of atmospheric aerosol. However, insights into the molecular-level mechanism of this oxidation reaction have been scarce. While OH initiated oxidation of small aldehydes, with two to five carbon atoms, under high-NOx conditions generally leads to fragmentation products, longer-chain aldehydes involving an initial non-aldehydic hydrogen abstraction can be a path to molecular functionalization and growth. In this work, we conduct a joint theoretical–experimental analysis of the autoxidation chain reaction of a common aldehyde, hexanal. We computationally study the initial steps of OH oxidation at the RHF-RCCSD(T)-F12a/VDZ-F12//ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVTZ level and show that both aldehydic (on C1) and non-aldehydic (on C4) H-abstraction channels contribute to HOMs via autoxidation. The oxidation products predominantly form through the H abstraction from C1 and C4, followed by fast unimolecular 1,6 H-shifts with rate coefficients of and s−1, respectively. Experimental flow reactor measurements at variable reaction times show that hexanal oxidation products including HOM monomers up to C6H11O7 and accretion products C12H22O9−10 form within 3 s reaction time. Kinetic modeling simulations including atmospherically relevant precursor concentrations agree with the experimental results and the expected timescales. Finally, we estimate the hexanal HOM yields up to seven O atoms with mechanistic details through both C1 and C4 channels.

- Article

(1240 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(978 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Aldehydes are important compounds in natural and polluted troposphere with typical atmospheric lifetimes on the order of 10 h or less. They play an important role in the atmosphere as prompt HOx and ROx radical sources (Vandenberk and Peeters, 2003). They are commonly formed, or directly emitted, from several biogenic and anthropogenic processes (Lipari et al., 1984). The anthropogenic emissions of many straight-chain aldehydes, essentially from incomplete fossil fuel combustion and biomass burning, are higher than the emissions of n-alkanes with the same carbon numbers (Schauer et al., 1999a, b). In the natural environment they are emitted directly by vegetation or are formed during the first steps of photo-oxidation of a multitude of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (Ciccioli et al., 1993; Carlier et al., 1986). They are the common products in the reactions of alkenes with ozone and are thus prevalent within most biogenic VOC oxidation processes (Calogirou et al., 1999). They are often toxic; irritate mucous membranes, eyes, and skin; and cause odor problems at relatively low concentrations (Vandenberk and Peeters, 2003; Ernstgård et al., 2006).

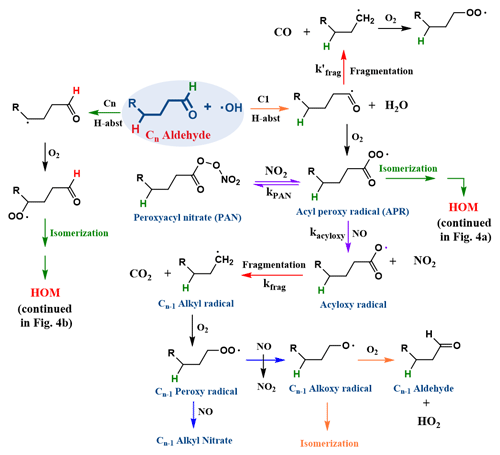

On a global scale, the fate of aldehydes is predominantly governed by OH reactions and photolysis during daytime (Calvert et al., 2011; Mellouki et al., 2003, 2015), while reactions with NO3 radicals are prevalent during the night (Calvert et al., 2011). Although OH-induced oxidation of aliphatic aldehydes with up to five carbon atoms has been extensively studied (Castañeda et al., 2012; Iuga et al., 2010; Manion et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Albaladejo et al., 2002), research on longer-chain aldehydes is scarce. Due to the weaker bond strength of the aldehydic hydrogen, the oxidation of aldehydes is frequently initiated by the abstraction of that atom (Calvert et al., 2011; Mellouki et al., 2003, 2015). Under high-NOx conditions, this commonly leads to Cn−1 alkyl nitrates, Cn−1 aldehydes, and Cn−1 alkoxy isomerization products (Chacon-Madrid et al., 2010) via scission of the carbon chain (red arrows in Fig. 1) through acyl (i.e., CO loss) and acyloxy (i.e., CO2 loss) intermediates (Rissanen et al., 2014; Vereecken and Peeters, 2009). The exceptions are the Cn peroxy acids (PA) and Cn peroxyacyl nitrates (PAN) (Calvert et al., 2011; Mellouki et al., 2003, 2015; Chacon-Madrid et al., 2010) formed in reactions of acyl peroxy radicals (APR) with HO2 and NO2, respectively (see Fig. 1). The subsequent branching of the Cn−1 alkoxy radical towards isomerization, decomposition, and reaction with O2 depends on the size and substitution of the alkyl chain, with the longer chains (≥C7) favoring the isomerization paths (Atkinson and Arey, 2003; Vereecken and Peeters, 2010; Lim and Ziemann, 2005, 2009; Kwok et al., 1996; Atkinson, 2007).

Figure 1General reaction mechanism of n-aldehyde oxidation by OH radical. The aldehydic H-abstraction channel (C1) leads to fragmentation and isomerization products, while a non-aldehydic H-abstraction channel (Cn) leads to isomerization products. The isomerization channels associated with green arrows are continued in Fig. 4. Under high-NOx conditions, the acyl peroxy radical (APR) forms an acyloxy radical (violet arrow), which fragments into a Cn−1 intermediate (+ CO2) and ultimately to a Cn−1 terminal alkoxy radical (blue arrow) that can either isomerize or react with O2 to form a Cn−1 aldehyde. The isomerization channel (orange arrow) is generally favored for long straight-chain aldehydes.

In the last decade, highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) have been identified as large, direct contributors to atmospheric secondary organic aerosol (SOA) (Ehn et al., 2014; Öström et al., 2017; Bianchi et al., 2019; Brean et al., 2019, 2020), the dominant component of tropospheric fine particulate matter influencing oxidative capacity, local and global air quality, climate change, and human health (Laden et al., 2006; Hallquist et al., 2009; Spracklen et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2014; Jacobson et al., 2000; Hansen and Sato, 2001; Kanakidou et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2014). HOMs are produced through a sequential progression of peroxy radical (RO2) hydrogen shift reactions (i.e., H-shifts) and molecular oxygen additions in a process called “autoxidation”. In the case of alkenes and aromatics, the process may also proceed via ring closure reactions forming organic peroxides (Xu et al., 2019; Rissanen et al., 2015; Glowacki et al., 2009; Møller et al., 2020). Autoxidation causes a rapid increase in the oxygen content of the molecule (Rissanen et al., 2014, 2015; Crounse et al., 2013; Jokinen et al., 2014; Mentel et al., 2015; Berndt et al., 2015, 2016), with even up to three O2 additions at sub-second timescales (Iyer et al., 2021), and produces progressively functionalized products that can participate in aerosol formation and growth. Aldehydes are common first-generation products in several hydrocarbon oxidation sequences (Atkinson and Arey, 2003), and thus their tendency to form HOMs is of special interest.

Chacon-Madrid et al. (2010) have studied the SOA yields from several n-aldehyde oxidation systems under high-NOx conditions and contrasted the findings with similar n-alkane oxidation. Under their high-NOx reaction conditions, they found significantly lower SOA yields for the aldehydes and attributed it to the relatively volatile PAN formation (see Fig. 1). In a more recent work targeting HOMs in cyclohexene oxidation, NO2 was found to suppress HOM formation (Rissanen, 2018), especially the important low-volatility dimer products (Tröstl et al., 2016), shedding some light to the low SOA mass observed by Chacon-Madrid et al. (2010).

The previous mechanistic understanding of gas-phase VOC oxidation states that the abstraction of the aldehydic H atom by, e.g., OH, rapidly leads to fragmentation and is therefore not expected to lead to VOC functionalization. However, recent experimental studies have shown that the abstraction of the aldehydic hydrogen promotes HOM formation (Rissanen et al., 2014; Ehn et al., 2014; Tröstl et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021) and is thus expected to increase the SOA yields, especially under low-NOx conditions. Thus, in this work, we set out to resolve this apparent discrepancy and study the molecular level gas-phase oxidation mechanism of a common aldehyde using a joint theoretical–experimental approach, focusing on HOM formation by autoxidation. As most of the HOM products detected appear to contain the same number of carbon atoms as the parent VOC (Bianchi et al., 2019), the pathways that do not break the carbon chain are of interest. Branched and substituted aldehydes are more prone to decomposition as alkoxy intermediates derived from these often tend to undergo fragmentation rather than isomerization reactions. In linear aldehydes, the non-fragmentation pathways likely involve H atom abstraction from a carbon atom that is distant from the aldehydic moiety. Although a major fraction of the H abstraction occurs from the aldehydic carbon, other abstraction channels are more likely to promote functionalization and become more competitive as the carbon chain size increases.

In this work, we investigate the H abstraction by OH of hexanal and the subsequent H-shift chemistry leading to HOMs through aldehydic and non-aldehydic H-abstraction channels. Hexanal was chosen as a surrogate for the larger aldehydes because its size was deemed suitable; it is large enough to allow for efficient H-shifts, but it is not large enough to make high-level quantum chemical computations unfeasible. It should be noted that the larger aldehydes and their oxidized products are invariably more complex than the hexanal model system studied here, and the added functional groups can often increase the rate of autoxidation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a detailed autoxidation mechanism of HOM formation from aldehydes is presented, leading to several HOM products from hexanal by a single OH oxidant attack.

2.1 Quantum chemical calculations

We employ quantum chemical calculations to find the most efficient route to an OH oxidized hexanal product containing seven oxygen atoms. Some of the intermediates and transition states along the reaction pathway possess RR and RS configurational isomers, each with many potential conformers. Since the inter-conversion between different isomers typically involves the breaking and reformation of covalent bonds and is consequently associated with high barriers, we consider the RR and RS isomers separately.

2.1.1 Conformer sampling and geometry optimization

Systematic conformer sampling is performed using the Merck molecular force field (MMFF) method implemented in the Spartan'18 program with a neutral charge enforced on the radical center (Wavefunction Inc., 2018; Møller et al., 2016). The conformers are generated by varying all torsional angles of each molecular species by 120∘ (rotating every nonterminal bond three times).

Initial geometry optimizations are performed at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level. For molecules containing three or more O atoms (resulting in more conformers that are also computationally heavy to optimize), the number of conformers is first reduced by performing a single-point electronic energy calculation at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level of theory. Conformers with electronic energies within 5 kcal mol−1 relative to the lowest-energy conformer are considered for geometry optimization at the same level of theory. Subsequently, conformers within 2 kcal mol−1 in relative electronic energies are optimized at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVTZ level (Chai and Head-Gordon, 2008; Dunning, 1989; Kendall et al., 1992). All calculations following the initial conformer sampling are carried out using the Gaussian 16 program (Frisch et al., 2016).

The transition states (TSs) corresponding to specific hydrogen shifts are found by first constraining the H atom at an approximate distance from the relevant C and O atoms (1.3 and 1.15 Å, respectively) and optimizing the structure. The optimized geometry is then used as an input for an unconstrained TS calculation. These calculations are carried out at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level of theory. Once the TS geometry is found, an MMFF conformer sampling step is carried out using Spartan'18 with the O–H and H–C bond lengths constrained. Additionally, partial bonds with torsions enabled are added to these two bonds prior to the conformer sampling step. The partial bonds have been reported to improve the MMFF optimization, resulting in geometries that are closer to local energy minima during the conformer sampling (Draper et al., 2019). The resulting TS conformers from the conformer sampling step are once again optimized, first with the TS relevant bonds constrained, followed by an unconstrained TS optimization, both at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level of theory. Finally, TS geometries within 2 kcal mol−1 of the lowest-energy geometries are optimized at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. Transition states corresponding to the OH H abstraction of hexanal are found using the same approach, except for the aldehydic H abstraction, in which case the initial TS optimization is carried out using the MN15/def2-tzvp level of theory instead of B3LYP/6-31+G* since the latter method failed to find the TS structure.

On the lowest electronic energy reactant, intermediate, TS, and product geometries at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVTZ level (MN15/def2-tzvp for the aldehydic H-abstraction case), single-point calculation at the RHF-RCCSD(T)-F12a/VDZ-F12 level is carried out using the Molpro program version 2019.2 (Werner et al., 2019). The T1 diagnostic numbers of all reactants, TSs, and products considered here are below 0.03 and 0.045 for closed-shell and open-shell species, respectively, indicating that these systems are single-reference systems and that the CCSD(T) numbers reported here are therefore reliable.

2.2 Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel–Marcus (RRKM) calculations

We employ the master equation solver for multi-energy well reactions (MESMER) program (Glowacki et al., 2012) to carry out RRKM simulations to estimate the branching ratios of selected products following unimolecular isomerization and O2 addition reactions. The unimolecular isomerization reactions are treated using the SimpleRRKM method with Eckart tunneling. The O2 addition reactions to carbon-centered radicals are treated using the “simple bimolecular sink” method in MESMER. In this case, a bimolecular loss rate coefficient of and an O2 “excess reactant” concentration of 5×1018 are used, which is the approximate O2 concentration under standard atmospheric conditions. The intermediates are assigned as “modeled” in the simulations and given Lennard–Jones parameters sigma=6.25 Å and epsilon=343 K (Hippler et al., 1983). MESMER utilizes the exponential down (ΔEdown) model for simulating the collisional energy transfer. For N2 bath gas, the MESMER-recommended values for ΔEdown are between 175 and 275 cm−1. We used a ΔEdown value of 225 cm−1 in our simulations. In addition, a grain size of 100 and a value of 60 kBT for the energy spanned by the grains were used. The MESMER input file corresponding to one of the studied reactions is provided in Sect. S9 in the Supplement as an example.

2.3 Rate coefficients

The unimolecular H-shift rate coefficients (k) reported in this work are calculated using the multi-conformer transition state theory (MC-TST) (Møller et al., 2016) including quantum mechanical tunneling (Henriksen and Hansen, 2018), as shown in Eq. (1).

The constants kB and h are Boltzmann's constant and Planck's constant, respectively. Absolute temperature, T, is set to 298.15 K. ΔEi is the zero-point-corrected energy of the ith TS conformer relative to the lowest-energy transition state conformer, and QTS,i is the partition function of the ith transition state conformer. Similarly, ΔEj and QR,j are the corresponding values for reactant conformer j. ETS−ER is the zero-point-corrected barrier height corresponding to the lowest-energy TS and reactant conformers. The partition functions are calculated at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory (MN15/def2-tzvp for the aldehydic H-abstraction case), while the energies include the final coupled-cluster correction. The tunneling coefficient κ is calculated using the one-dimensional Eckart approach as reported in Møller et al. (2016). This method requires the energies of the reactant and product wells that are connected to the lowest-energy TS geometry, which are found by running forward and reverse intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations on that TS geometry and optimizing the end geometries at the B3LYP/6-31+G* level of theory. The reactant and product wells are subsequently re-optimized at the ωB97X-D/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory, followed by single-point RHF-RCCSD(T)-F12a/VDZ-F12 energy corrections.

The rate coefficients of the H-abstraction reactions of hexanal by OH are calculated in three different ways (see Sect. S2 in the Supplement for details). The rate coefficients presented here involve only the lowest-energy conformers of TS and reactants using the bimolecular TST expression shown in Eq. (2):

where σ is the symmetry factor that is related to the reaction path degeneracy. Here, the values of σ are 1, 2, and 3 for the aldehydic H abstraction, abstraction from a secondary carbon (C2–C5), and abstraction from the primary carbon (C6), respectively (Castañeda et al., 2012). is the total concentration of molecules in standard condition, 2.46×1019 . Qhex and QOH are the partition functions of the lowest-energy hexanal and OH conformers, respectively.

The equation that accounts for multiple conformers of TS and hexanal (Viegas, 2018; Viegas and Jensen, 2023) reduces the rate coefficient of the aldehydic H abstraction. We find only three TS conformers for this reaction, while we have 18 conformers of hexanal that are within 2 kcal mol−1 in relative energy. Because the former goes into the numerator and the latter in the denominator of the bimolecular MC-TST equation, this reduces the rate. Viegas and Jensen (2023) studied fluorinated aldehydes with three carbon atoms employing an MC-TST equation that likely did not encounter this issue with the TS conformers. Castañeda et al. (2012) studied a similar aldehydic system to ours where they used the lowest-energy conformer TST (LC-TST) equation. We therefore adopt the same approach in this work to calculate the rate coefficients and consequently the branching ratios of OH H abstractions of hexanal.

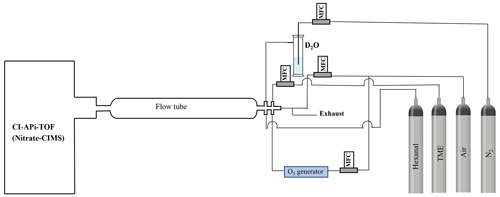

2.4 Chemical ionization mass spectrometry

The experimental hexanal OH oxidation reaction is conducted in a laboratory applying a flow rector setup (see Fig. 2). A nitrate-based time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometer (nitrate-CIMS) is used to detect the products of hexanal OH oxidation. Chemical ionization is achieved by supplying synthetic air (sheath flow) containing nitric acid (HNO3) under exposure to X-rays. This produces nitrate () ions that are mixed with the sample flow and that ionize HOMs as adducts. A sheath flow of 20 L min−1 and a sample flow of around 10 L min−1 (synthetic air as diluent) are used. The precursors are mixed in a quartz flow tube reactor where the oxidant OH is produced in situ by the ozonolysis reaction of tetramethylethylene (TME) (Berndt and Böge, 2006) (see Fig. 2). An ozone concentration of 225 ppb, which is generated by flowing synthetic air through an ozone generator fitted with a 184.9 nm (UVP, Analytik Jena) Hg Pen-Ray lamp, is allowed to react with 40 ppb of TME supplied from a gas cylinder to the reactor. A hexanal precursor concentration of 1 ppm is added to the reactor from another gas cylinder. The reaction time is controlled by adjusting the distance between the mass spectrometer orifice and the place where hexanal and OH meet inside the reactor. This is done by providing the hexanal flow through a moveable injector tube within the reactor. Accordingly, separate sets of experiments are conducted with variable reaction times (1.4, 3.1, and 12 s) to track the oxidation chain propagation. In addition, to confirm the structures of the identified products in favor of the proposed mechanisms, we conduct a hydrogen/deuterium () exchange experiment (12 s) by adding D2O from a bubbler with N2 flow.

Figure 2Schematic of the flow reactor setup used in the hexanal OH oxidation reaction. The oxidant OH radical is produced in situ by TME+O3 reaction. TME stands for tetramethylethylene. All flows are controlled by mass flow controllers (MFCs). The flow tube length is adjusted in the variable residence time experiments.

2.5 Kinetic modeling simulation

We inspect autoxidation propagation with bimolecular interventions under pristine boreal forest to polluted urban conditions using a kinetic simulator Kinetiscope version 1.1.956.x64 (Hinsberg and Houle, 2017). A single-reactor model with constant volume, pressure, and temperature is employed in the simulation. The temperature is set to 298.15 K. In the simulation setting, a total number of particles 1×108 and a random number seed 12 947 are used, while the maximum simulation time is set to 20 s.

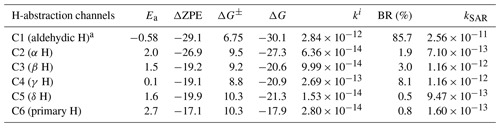

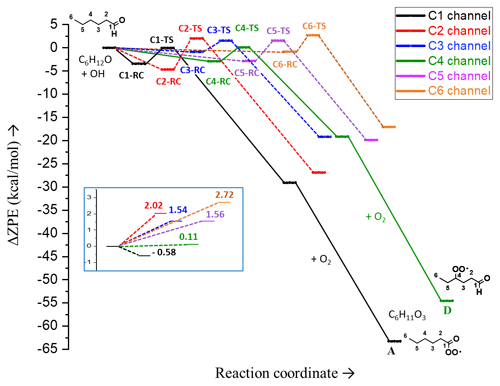

The calculated yields of the different H-abstraction channels of hexanal by OH (see Table 1) show that the abstraction from the aldehydic carbon C1 is the dominant channel, which is unsurprising due to the known low bond dissociation enthalpy of an aldehydic H atom. The next competitive H-abstraction channel is from the secondary carbon atom C4, which has a significantly lower barrier in comparison with the adjacent C3 and C5 sites. All H-abstraction channels with labeled carbon atoms and corresponding relative electronic energies of TSs and products are shown in Fig. 3.

Table 1Overall reaction and TS energies (in kcal mol−1) of the different OH H-abstraction reactions of hexanal along with calculated rate coefficients (in ) and branching ratios.

a Aldehydic H-abstraction barrier calculated at RHF-RCCSD(T)-F12a/VDZ-F12// MN15/def2-tzvp level of theory. BR stands for branching ratio. . kSAR is the structure–activity relationship (SAR) prediction rate coefficient (Jenkin et al., 2018; Ziemann and Atkinson, 2012).

Figure 3Relative (zero-point-corrected) electronic energies of pre-reactive complexes (RCs), transition states (TSs) and products in different H-abstraction channels of hexanal OH oxidation reaction. The enlarged view of the reaction barriers, Ea (ΔZPE±), relative to separated reactants and without pre-reactive complexes, is presented in the inset of the figure. The potential energy surface (PES) is extended for C1 and C4 channels up to the intermediates A and D, respectively (C6H11O3).

Since the C1 and C4 channels have the highest branching ratios, we focus on these to study the formation of HOMs. Nevertheless, the other abstraction channels can also potentially contribute and could provide additional pathways forming highly functionalized reaction products. Due to the rapid scaling up of the possible isomerization pathways, and due to the exponential increase in the required computing resources for larger system sizes, we limited our study to the formation of HOMs with up to seven oxygen atoms. These molecules are still radical intermediates that can potentially autoxidize and lead to molecules with even more oxygen atoms.

3.1 H-abstraction rates

Relative zero-point-corrected electronic energies (ZPE) and Gibbs free energies (for T=298.15 K and P=1 atm) of the TSs and overall reactions for the H-atom abstraction reactions of hexanal by OH are reported in Table 1. Ea (ΔZPE±) is the barrier of the reaction, which is calculated as ; ΔZPE is the overall reaction energy, . Analogously, ΔG± is the Gibbs free energy of activation, and ΔG is the reaction Gibbs free energy. The H-abstraction rate coefficients shown in Table 1 were calculated using Eq. (2). The corresponding branching ratios (BRs) are determined as ratios of the individual rate coefficients (ki) against the overall rate coefficient (koverall).

The results of Table 1 show that the zero-point-corrected electronic TS energy of the aldehydic H abstraction in hexanal OH oxidation is slightly below the separated reactants; the γ H abstraction on C4 has almost no barrier (i.e., 0.1 kcal mol−1), while the other H-abstraction channels have discernable barriers. The β and δ H abstractions on C3 and C5, respectively, have near-identical barriers, while the α H-abstraction barrier on C2 is 0.7 kcal mol−1 less than the primary H abstraction on C6. The H-abstraction barriers tend to increase as we move from C4 towards the carbon atoms along either the left or the right direction of the carbon chain (excluding the aldehydic carbon). This trend is consistent with the results of Castañeda et al. (2012), who showed that from ethanal to pentanal OH oxidation the β H-abstraction barriers are less than that of α H abstractions, while the aldehydic H abstractions have the lowest barriers.

Based on the decreasing trend of Ea with the increasing carbon chain length as shown by Castañeda et al. (2012) for aliphatic aldehydes up to five carbon atoms, it is expected that there will be somewhat lower barriers for similar H abstractions in hexanal. They calculated the barriers at the CCSD(T)/6-311++G**//BHandHLYP/6-311++G** level. However, using our method the barriers we calculated are roughly 0.5–2.5 kcal mol−1 higher in comparison to the values obtained by the aforementioned study for the different H abstractions.

It is apparent that our calculated overall rate coefficient cm3 s−1 is about an order of magnitude lower than the experimental rate coefficient cm3 s−1 measured for the hexanal + OH reaction (Albaladejo et al., 2002; D'Anna et al., 2001) and SAR prediction rate coefficient (see Table 1; detailed SAR calculations in Sect. S1 in the Supplement) (Jenkin et al., 2018; Ziemann and Atkinson, 2012). Reducing the barrier height by 1 kcal mol−1 (within the error margin of the method used), we obtain an overall rate coefficient of cm3 s−1 that is compatible with the reported experimental results.

The potential energy surface (PES) of hexanal for the different H-abstraction channels is shown in Fig. 3. The C1 channel associated with aldehydic H abstraction has a submerged barrier. Among other channels, the γ H abstraction on C4 shows the lowest barrier. The radical (C6H11O) formed via the α H abstraction is more stable than those obtained from β, γ, δ, and primary H abstractions because the unpaired electron in the former can delocalize over the carbonyl double bond. Although the stability of C6H11O radicals with respect to β, γ, and δ H abstractions are similar, the stability of the radical after primary H abstraction on C6 is the lowest.

C1 is the dominant channel, with a yield of 86 % (see Table 1), followed by the C4 channel, with a yield of around 8 %. The energies of the intermediate peroxy radicals A and D (see Fig. 3; C1 and C4 channels), which both have a molecular formula of C6H11O3, are below the separated reactants hexanal + OH by 63.3 and 54.5 kcal mol−1, respectively.

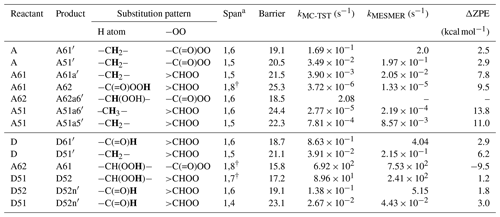

3.2 H-shift rates

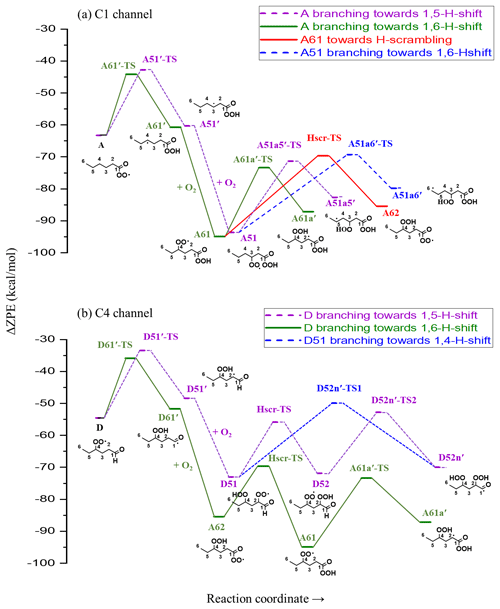

Mechanistic details of the HOM formation through both C1 and C4 channels are shown in Fig. 4. The PES of two lowest-energy barrier H-shift pathways of the peroxy radicals A and D are shown in Fig. 5, and the calculated transition state energies and rate coefficients are shown in Table 2. Although we report both MC-TST and MESMER rate coefficients, we use the MC-TST rate coefficients in the following discussions to compare with relevant literature rate coefficients. We found that the MC-TST rate coefficients are roughly an order of magnitude lower than those derived from MESMER. The MC-TST treatment includes the influence of several lowest-energy conformers, while MESMER only considers the lowest-energy TS and reactant conformers, and therefore the estimates are likely the upper limits. Both sets of rate coefficients are provided in Table 2 to establish a range of possible values. Additionally, hindered rotor calculations are performed to assess the error introduced to the calculated rate coefficients by treating anharmonic low-frequency torsions as harmonic oscillators. The hindered rotor treatment is not applied to those reactions where hindered rotor calculations failed for one or more conformers. Therefore, the resultant rate coefficients are not used here for the calculation of branching ratios as they are not suitable for direct comparison. The hindered rotor treatment changes the rate coefficients by about a factor of 2 in most of the cases (see Sect. S3 in the Supplement).

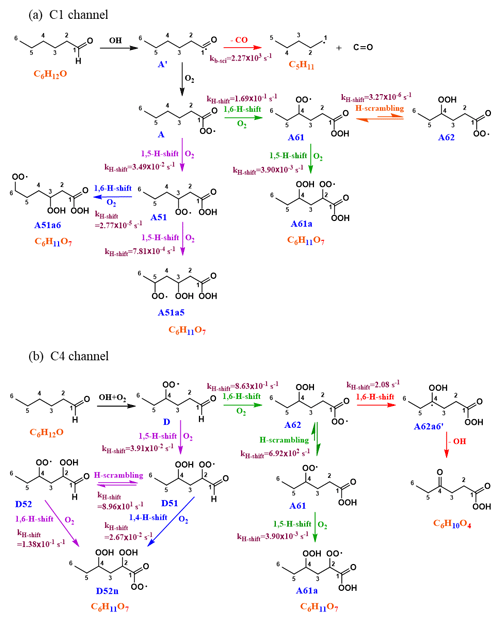

Figure 4Mechanism of hexanal + OH reaction initiated by H abstraction on (a) carbon C1 and (b) carbon C4. The branching of A between green and purple channels is 91 % : 9 %. A61 branches towards A62 by only 0.1 %, while the remaining 99.9 % is towards the formation of A61a. The branching of D between green and purple channels is 95:5. Since the subsequent branching of A62 towards the dead-end red channel is only 0.3 %, the green channel is likely to continue functionalization towards A61a. In the C4 purple channel, D51 branches towards the blue route by 3 %, still giving the same product as the parent purple channel.

Figure 5Stationary points along the PES of hexanal OH oxidation reaction (continuation from Fig. 3). Zero-point-corrected energies are shown on the y axis, and the reaction coordinate is shown on the x axis. TS is the transition state, and Hscr is H scrambling. Labels with a prime, e.g., A61′, indicate alkyl radicals.

Table 2Calculated rate coefficients for H migration in peroxy radicals. The migrating H atoms are marked in bold.

a H-shift span. † H-scrambling reactions.

The initial abstraction of the H atom from C1 by OH creates a radical center on the terminal carbon giving intermediate A′ (Fig. 4a). The intermediate A′ has the possibility of either fragmenting towards pentyl (C5H11) radical and carbon monoxide (CO) or adding an O2 molecule to form an APR intermediate A (C6H11O3). The calculated rate coefficient of the fragmentation pathway is 2.27×103 s−1, which is significantly slower than O2 addition (∼107 s−1 under atmospheric conditions). The formation of intermediate A is therefore the most competitive route available to A′. Subsequent intramolecular H-shift reactions of A are key for rapid autoxidation and the formation of highly functionalized products.

In the current analysis, we exclude and RO2+NOx reactions and focus on unimolecular autoxidation reactions that lead to rapid functionalization and formation of HOMs. The intermediate APR A can follow either the 1,6-H-shift reaction (C1 green channel) or the 1,5-H-shift reaction (C1 purple channel) and subsequently form the peroxy radical intermediates A61 and A51, respectively, both with the composition C6H11O5 and having a terminal peroxy acid group. The calculated barrier heights of A towards 1,6-H-shift (green route) and 1,5-H-shift (purple route) reactions are 19.1 and 20.5 kcal mol−1, respectively, with corresponding rates of and s−1, respectively. We did not find similar acyl peroxy H-shift rate coefficients reported in the literature for comparison.

The initial H abstraction by OH from the C4 carbon and the subsequent rapid O2 addition gives the peroxy radical D (Fig. 4b). This peroxy radical can readily abstract the aldehydic hydrogen via an intramolecular 1,6-H-shift reaction and subsequently form the APR A62 (C4 green channel). The peroxy radical D can also abstract an H atom from carbon C2, which is the next most competitive channel (purple arrows, C4 channel) after the aldehydic H-shift. The calculated barrier heights of the 1,6-H-shift (green route) and 1,5-H-shift (purple route) reactions are 18.7 and 21.1 kcal mol−1, respectively, with corresponding rate coefficients of and s−1, respectively. The literature rate coefficient of a similar aldehydic 1,6-H-shift from CHO to >CHOO reported by Vereecken and Nozière (2020) is higher (k=7.9 s−1) by about a factor of 9 than the rate reported here (1,6-H-shift in C4 channel mentioned above), while the rate coefficient of peroxy H-shift from −CH2− with 1,5 span is about an order of magnitude lower ( s−1). The higher rate coefficient for the peroxy H-shift reaction we report could be due to the presence of the α-CHO group next to the −CH2− group. The branching of A and D (both C6H11O3) towards green and purple sub-channels are governed by these initial H-shift barriers. The MESMER simulation derived branching ratios of A towards green and purple channels of 91 % and 9 %, respectively, while the same ratios for D are 95 % and 5 %, respectively.

In the C1 green channel, the alkyl peroxy radical intermediate A61 (C6H11O5) with a terminal peroxy acid group needs to overcome a barrier of 21.5 kcal mol−1 to undergo a 1,5-H-shift reaction to form a carbon-centered radical on C2. The rate coefficient for this isomerization is s−1. Subsequently, the alkyl radical A61a′ (see Fig. 5, not shown in Fig. 4) can add an O2 molecule to form the C6H11O7 peroxy radical (A61a). As the peroxy acid group is significantly more stable than the acyl peroxy group, the barrier for the H-scrambling reaction (between γ-OO and peroxy acid groups) of A61 is quite high (Ea=25.28 kcal mol−1, s−1), making the formation of A62 unlikely (orange double arrow in Fig. 4a).

Along the C1 purple channel, the intermediate A51 needs to overcome the barriers of 22.3 and 24.4 kcal mol−1 to undergo 1,5- and 1,6-H-shift reactions to yield A51a5′ and A51a6′ radicals, respectively (see Fig. 5), and subsequently, by O2 addition, they form the non-terminal peroxy radical A51a5 and the terminal peroxy radical A51a6, respectively (purple and blue arrows, Fig. 4a). The corresponding rate coefficients are and s−1, respectively; too slow to significantly compete with bimolecular reactions. Comparing with the literature data, the analogous rate coefficient of peroxy 1,6-H-shift reaction from a terminal CH3 group found by Vereecken and Nozière (2020) is even lower ( s−1). The difference is likely due to the dissimilarity in the molecular structures in terms of the functional groups on the carbon chain in the studied cases.

In the C4 green channel, the A62 peroxy radical can immediately undergo an H-scrambling reaction between γ-OOH and acyl peroxy groups, and form the peroxy radical A61 with a terminal peroxy acid group (the same intermediate as in C1 channel). The fast H-scrambling reaction with a barrier of 15.8 kcal mol−1 and rate coefficient 6.92×102 s−1 switches the radical center in C6H11O5 intermediate turning A62 to more stable A61. This fast reaction is the reverse of the previous A61 to A62 conversion reaction in C1 channel. This rate coefficient is similar to that reported by Vereecken and Nozière (2020) for H-scrambling reactions with 1,8 spans ( to 1.36×103 s−1). The α-OOH H atom of A62 can also migrate to the terminal acyl peroxy radical by 1,6-H-shift reaction leading it towards the radical termination channel (red arrows), giving the closed-shell ketohydroperoxide product C6H10O4 (see Fig. 4b). The rate coefficient of such 1,6-H-migration to a tertiary peroxy radical was estimated by Vereecken and Nozière (2020) to be s−1. In our acyl peroxy radical case, we found a very fast rate coefficient (2.08 s−1) for A62 to A62a6′ conversion. Based on our calculated rate coefficients, the branching ratios of A62 towards the green and red channel are 99.70 % and 0.30 %, respectively. This channel thus regenerates the same A61 intermediate that follows the identical pathway, as we observed in C1 green channel, leading to the C6H11O7 peroxy radical.

Continuing to the C4 purple channel, we get to the intermediate D51 with an OOH functionality at C4 and with an intact aldehydic functionality. The D51 radical intermediate can then follow a rapid H-scrambling reaction to form the peroxy radical D52. The H-scrambling rate corresponding to the conversion of intermediate D51 to D52 is around 5 times lower than that of in the green channel. The H-scrambling barrier in the latter case is 1.27 kcal mol−1 higher, and the corresponding D52 intermediate is 1.17 kcal mol−1 less stable than D51. However, the faster aldehydic 1,6-H-shift reaction ( s−1) in D52 makes it possible to quickly form C6H11O7 APR through the formation of D52n′ (shown in Fig. 5) acyl radical intermediate followed by O2 addition. The same D52n′ intermediate can also be formed directly from D51 by aldehydic 1,4-H-shift reaction (blue arrow, Fig. 4b), which seems to be very unlikely due to the higher barrier of 23.1 kcal mol−1 and corresponding low rate coefficient of s−1. Vereecken and Nozière (2020) reported a similar rate coefficient ( s−1) for such aldehydic H-shift reaction with 1,4 span. The APR D52n is likely to follow similar subsequent reactions to the other APR A62. However, the former has an additional OOH functionality on carbon C2, allowing for two competing H-scrambling reactions. Here the MESMER simulation derived a branching ratio of D51 (C6H11O5) towards purple and blue channel of 97 % and 3 %, respectively. We did not calculate the relative energies of the final C6H11O7 intermediates, which we expect to get further energetically lowered by 25–35 kcal mol−1 due to O2 addition at the last step of their formation. Note that the reported unimolecular rate coefficients have an error margin of about a factor of 5 for the method used.

The overall maximum yields of the different oxidation products up to C6H11O7 HOM from initial hexanal OH oxidation are calculated by multiplying the branching ratios of each intermediate along the reaction pathway. When considering the two competing isomerization channels of the APR A shown in Fig. 4a (and excluding possible bimolecular reactions), the overall maximum yield of C6H11O5 intermediate (A61) through the C1 green channel is 78 %, which subsequently leads to an O7 HOM via a 1,5-H-shift reaction. The overall yield of the same A61 intermediate formed by the C4 green channel is 7.7 %, which can follow similar chain propagation steps towards HOM. The O5-intermediate associated with the C1 purple channel has a yield of 7.7 %, but the subsequent H-shift rates are very slow, and it is unlikely to efficiently form an O7 HOM through this channel. On the other hand, the overall C6H11O7 yield by the C4 purple channel is 0.4 %, where the only limiting step is the initial branching of the green and purple pathways.

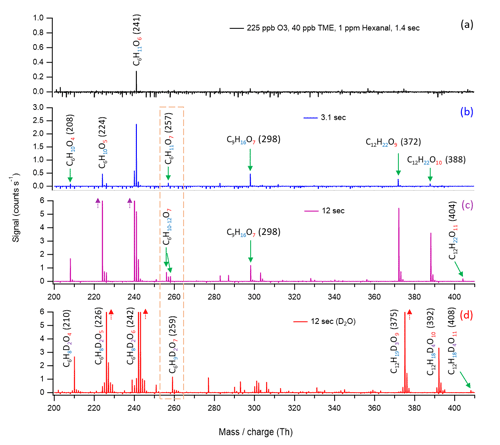

3.3 Flow reactor experiments

The evolution of mass spectra at variable reaction time experiments is in agreement with the proposed OH initiated hexanal autoxidation mechanism. In our experiments, we use high precursor concentrations, and the experimental condition does not exclude the bimolecular reactions. The formation of O7 HOM (C6H11O7) is observed at a 3.1 s reaction time, strongly supporting the proposed computational mechanism (see Fig. 6b and c ; blue and purple). In addition, kinetic modeling simulations using atmospherically relevant concentrations and including RO2+RO2 and RO2+NO loss processes show the formation of O5 and O7 products in the expected timescales (details in Sect. 3.4). The C6H11O6 peak in Fig. 6a appears as early as 1.4 s reaction time, and it almost certainly involves RO2 bimolecular reactions, as only odd numbers of O atoms would be expected for purely RO2-mediated aldehyde autoxidation. A possible formation mechanism of C6H11O6 peroxy radical is the conversion of C6H11O5 (A61 in Fig. 4) to an alkoxy radical C6H11O4 via a bimolecular step, followed by a 1,4-H-shift reaction and subsequent O2 addition (see Fig. S2 in the Supplement). The absence of the C6H11O5 peroxy intermediate can be due to the poor detection sensitivity of for species with less than two hydrogen bonding functional groups (Hyttinen et al., 2015). In Fig. 6b, we observe the appearance of O7 HOM (C6H11O7), HOM accretion products (C12H22O9−10), O4 and O5 closed-shell products, and a cross-reaction product C9H16O7 (i.e., a peroxide accretion product formed from hexanal-derived C6H11O6 and TME-produced C3H5O3 peroxy radical; see Fig. S4 in the Supplement) at 3.1 s reaction time. For the closed-shell C6H10O5 product, it could be formed through the classical Russell mechanism producing an alcohol and ketone (Russell, 1957; Hasan et al., 2020) (see Fig. S3a in the Supplement), or it could alternatively also form through the C6H11O7 (A61a in Fig. 4) involving a bimolecular step to produce an alkoxy radical C6H11O6 followed by a 1,4-H-shift reaction and a subsequent OH loss (see Fig. S3b). As the reaction proceeds up to 12 s (Fig. 6c; purple), we see that the previously observed product peaks grow larger and more peaks appear, including the HOM accretion product C12H22O11. The likely formation processes of C9H16O7 and HOM accretion products (C12H22O9−11) are discussed in Sect. S5 in the Supplement.

Figure 6Nitrate chemical ionization mass spectra at different hexanal + OH reaction times: (a) 1.4 s, (b) 3.1 s, and (c) 12 s. The oxidation products are detected as adducts with , which is excluded from the labels. The backgrounds of TME ozonolysis (TME + O3) and hexanal have been subtracted from all spectra, resulting in several negative peaks in panels (a) and (b). Panel (d) shows the mass shifts in the product peaks during the exchange experiment. TME is tetramethylethylene. The accretion product C9H16O7 is linked with the TME-derived peroxy radical C3H5O3.

The structures that we propose for C6H11O7 (A61a), C6H11O6, and C6H10O5 contain two labile hydrogen atoms (either two −OOH groups or one −OH together with an −OOH group). Accordingly, the D2O experiment associated with the spectrum (red) in Fig. 6d shows mass shifts of two units for these products in support of the assigned structures. Regarding the accretion products, the mass shifts of 3–4 units in the D2O experiment are according to the presence of 3–4 labile hydrogen-containing groups in their structures, and they are in full agreement with the proposed peroxy radical structures forming them according to a general reaction (Bianchi et al., 2019; Valiev et al., 2019; Hasan et al., 2020).

3.4 Kinetic modeling and atmospheric implications

The hexanal peroxy radical autoxidation process producing HOM described in the current work is in competition with bimolecular sink reactions under most atmospheric conditions. In our kinetic modeling simulations, we include RO2+RO2 and RO2+NO reactions as bimolecular sinks to illustrate the relative role of autoxidation in hexanal OH oxidation leading to HOM. We use a range of precursor concentrations to simulate situations from pristine boreal forest conditions to moderately polluted urban conditions (details are provided in Sect. S7 in the Supplement). Considering a cleaner environment with 0.1 ppb of NO (2.46×109 ), a generic 1.0×108 of RO2, 1 ppb (2.46×1010 ) of hexanal, and 1.0×107 of OH, the simulation leads to an appreciable concentration (3.0×103 ) of O5 intermediate formed as early as after 0.3 s of reaction time while O7 HOM is at 3.8 s. The concentrations grow to a maximum of 1.9×106 and 3.2×104 for O5 intermediate and O7 HOM, respectively, after 10 s of reaction time. Under high hexanal concentrations (maximum of 8.8 ppb), the above product concentrations increase by roughly a factor of 3 to 4. At a very low NO condition (0.01 ppb), these product concentrations increase by a factor of up to 1.6. Interestingly, even at 1 ppb of NO with 1.0×108 of RO2, the O7 HOM concentration goes as high as 1.3×104 after 10 s of reaction time. However, a NO level of 4 ppb practically halts O7 HOM production through C4 channel even at higher hexanal conditions, while 40 ppb of NO significantly prohibits any O5 intermediate formation. Although we use higher precursor and oxidant concentrations in our laboratory experiments (1 ppm hexanal, 225 ppb ozone, 40 ppb TME) to allow for efficient HOM production and detection, the trend in the evolution of mass spectral peaks matches with that of the simulations. The H-shift rate coefficients in autoxidation are highly temperature dependent, and the MESMER simulations carried out over a range of temperatures show that the second H-shift rate coefficients that lead to O7 HOM are increased by a factor of ∼2 to 8 at 310 and 330 K, respectively, relative to the rate coefficients at 298.15 K (see Sect. S8 in the Supplement). It should also be noted that bimolecular reactions involving NO, RO2, and HO2 that produce RO radicals do not necessarily terminate autoxidation but can also propagate it (Iyer et al., 2018; Rissanen, 2018; Wang et al., 2021; Newland et al., 2021; Mehra et al., 2021).

This work illustrates how a common aldehyde, hexanal, has the potential to rapidly autoxidize to a HOM, and thus contribute to the condensable material budget that ultimately grows atmospheric secondary organic aerosol. Our results on the initial H-abstraction channels of hexanal by OH are consistent with the previous literature results. Abstraction of the aldehydic H atom is the most competitive pathway, and it leads primarily to an acyl peroxy radical as the competing CO loss channel is slow relative to O2 addition under atmospheric conditions. Subsequent H-shift reactions of the acyl peroxy radical are surprisingly fast and lead to a O5-containing product at sub-second timescales. Apart from the aldehydic H-abstraction channel, the H abstraction from the C4 carbon by OH is the next most competitive pathway for hexanal. As the subsequent peroxy H-shift in the aldehydic H atom is rapid, and this abstraction ultimately leads to the same O5 peroxy acid containing RO2 as the most prominent abstraction route. The following H-shift reaction rate coefficient is slow, and bimolecular processes can intervene with the autoxidation chain. On the other hand, although the initial branching of the primary RO2 towards hydroperoxy-substituted RO2 with the aldehydic group intact is very small, the following H-shift rate coefficients are significant enough to rapidly form O7 HOMs. In the current work, we show how gas-phase autoxidation of aldehydes can be a direct source of condensable material to urban atmospheres even under moderately polluted conditions and should be accounted for in assessing the air quality and particle loads of any atmospheric environment.

Kinetic modeling results and an example MESMER input file corresponding to one of the studied reactions are provided in the Supplement. The ab initio output files (.log and .out), a MESMER input file (.xml) including hindered rotor treatment, and an Excel file (.xlsx) with hindered rotor potentials are available online (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8212748; Barua, 2022).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-10517-2023-supplement.

MR, SB, and SI devised the research. SB carried out the electronic structure and master equation calculations and performed the kinetic modeling simulations with contributions from SI and PS. MR, SB, and AK designed the experimental setup; SB and AK carried out the experiments; and SB analyzed the data. SB wrote the paper with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the CSC IT Center for Science in Espoo, Finland, for providing the computing resources.

The research has been supported by the H2020 European Research Council (grant no. 101002728), the Research council of Finland (grant nos. 331207, 336531, 346373, and 353836), and the doctoral school of the Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences of Tampere University.

This paper was edited by Sergey A. Nizkorodov and reviewed by Robin Shannon, Luís Pedro Viegas, and one anonymous referee.

Albaladejo, J., Ballesteros, B., Jiménez, E., Martín, P., and Martínez, E.: A PLP–LIF kinetic study of the atmospheric reactivity of a series of C4–C7 saturated and unsaturated aliphatic aldehydes with OH, Atmos. Environ., 36, 3231–3239, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(02)00323-0, 2002. a, b

Atkinson, R.: Rate constants for the atmospheric reactions of alkoxy radicals: An updated estimation method, Atmos. Environ., 41, 8468–8485, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.07.002, 2007. a

Atkinson, R. and Arey, J.: Atmospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds, Chem. Rev., 103, 4605–4638, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0206420, 2003. a, b

Barua, S.: An aldehyde as a rapid source of secondary aerosol precursors: Theoretical and experimental study of hexanal autoxidation, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8212748, 2022. a

Berndt, T. and Böge, O.: Formation of phenol and carbonyls from the atmospheric reaction of OH radicals with benzene, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 8, 1205–1214, https://doi.org/10.1039/B514148F, 2006. a

Berndt, T., Richters, S., Kaethner, R., Voigtländer, J., Stratmann, F., Sipilä, M,̇ Kulmala, M., and Herrmann, H.: Gas-phase ozonolysis of cycloalkenes: formation of highly oxidized RO2 radicals and their reactions with NO, NO2, SO2, and other RO2 radicals, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 10336–10348, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b07295, 2015. a

Berndt, T., Richters, S., Jokinen, T., Hyttinen, N., Kurtén, T., Otkjær, R. V., Kjaergaard, H. G., Stratmann, F., Herrmann, H., Sipilä, M., Kulmala, M., and Ehn, M.: Hydroxyl radical-induced formation of highly oxidized organic compounds, Nat. Commun., 7, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13677, 2016. a

Bianchi, F., Kurtén, T., Riva, M., Mohr, C., Rissanen, M. P., Roldin, P., Berndt, T., Crounse, J. D., Wennberg, P. O., Mentel, T. F., Wildt, J., Junninen, H., Jokinen, T., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Thornton, J. A., Donahue, N., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Ehn, M.: Highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOM) from gas-phase autoxidation involving peroxy radicals: A key contributor to atmospheric aerosol, Chem. Rev., 119, 3472–3509, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00395, 2019. a, b, c

Brean, J., Harrison, R. M., Shi, Z., Beddows, D. C. S., Acton, W. J. F., Hewitt, C. N., Squires, F. A., and Lee, J.: Observations of highly oxidized molecules and particle nucleation in the atmosphere of Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 14933–14947, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-14933-2019, 2019. a

Brean, J., Beddows, D. C. S., Shi, Z., Temime-Roussel, B., Marchand, N., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Minguillón, M. C., and Harrison, R. M.: Molecular insights into new particle formation in Barcelona, Spain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 10029–10045, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-10029-2020, 2020. a

Calogirou, A., Larsen, B., and Kotzias, D.: Gas-phase terpene oxidation products: a review, Atmos. Environ., 33, 1423–1439, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(98)00277-5, 1999. a

Calvert, J., Mellouki, A., and Orlando, J.: Mechanisms of atmospheric oxidation of the oxygenates, OUP USA, ISBN 9780199767076, 2011. a, b, c, d

Carlier, P., Hannachi, H., and Mouvier, G.: The chemistry of carbonyl compounds in the atmosphere – A review, Atmos. Environ., 20, 2079–2099, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(86)90304-5, 1986. a

Castañeda, R., Iuga, C., Álvarez-Idaboy, J. R., and Vivier-Bunge, A.: Rate constants and branching ratios in the oxidation of aliphatic aldehydes by OH radicals under atmospheric conditions, J. Mex. Chem. Soc., 56, 316–324, 2012. a, b, c, d, e

Chacon-Madrid, H. J., Presto, A. A., and Donahue, N. M.: Functionalization vs. fragmentation: n-aldehyde oxidation mechanisms and secondary organic aerosol formation, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 12, 13975–13982, https://doi.org/10.1039/C0CP00200C, 2010. a, b, c, d

Chai, J.-D. and Head-Gordon, M.: Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 10, 6615–6620, https://doi.org/10.1039/B810189B, 2008. a

Ciccioli, P., Brancaleoni, E., Frattoni, M., Cecinato, A., and Brachetti, A.: Ubiquitous occurrence of semi-volatile carbonyl compounds in tropospheric samples and their possible sources, Atmos. Environ. A-Gen., 27, 1891–1901, https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-1686(93)90294-9, 1993. a

Crounse, J. D., Nielsen, L. B., Jørgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Autoxidation of organic compounds in the atmosphere, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 4, 3513–3520, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz4019207, 2013. a

D'Anna, B., Andresen, Ø., Gefen, Z., and Nielsen, C. J.: Kinetic study of OH and NO3 radical reactions with 14 aliphatic aldehydes, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 3, 3057–3063, https://doi.org/10.1039/B103623H, 2001. a

Draper, D. C., Myllys, N., Hyttinen, N., Møller, K. H., Kjaergaard, H. G., Fry, J. L., Smith, J. N., and Kurtén, T.: Formation of Highly Oxidized Molecules from NO3 Radical Initiated Oxidation of Δ-3-Carene: A Mechanistic Study, ACS Earth Space Chem., 3, 1460–1470, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.9b00143, 2019. a

Dunning Jr., T. H.: Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen, J. Chem. Phys., 90, 1007–1023, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.456153, 1989. a

Ehn, M., Thornton, J. A., Kleist, E., Sipilä, M., Junninen, H., Pullinen, I., Springer, M., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Lee, B., Lopez-Hilfiker, F., Andres, S., Acir, I.-H., Rissanen, M., Jokinen, T., Schobesberger, S., Kangasluoma, J., Kontkanen, J., Nieminen, T., Kurtén, T., Nielsen, L. B., Jørgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., Canagaratna, M., Maso, M. D., Berndt, T., Petäjä, T., Wahner, A., Kerminen, V.-M., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Wildt, J., and Mentel, T. F.: A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol, Nature, 506, 476–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13032, 2014. a, b

Ernstgård, L., Iregren, A., Sjögren, B., Svedberg, U., and Johanson, G.: Acute effects of exposure to hexanal vapors in humans, J. Occup. Environ. Med., 48, 573–580, 2006. a

Frisch, M., Trucks, G., Schlegel, H., Scuseria, G., Robb, M., Cheeseman, J., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Petersson, G., Nakatsuji, H., Li, X., Caricato, M.,Marenich, A. V., Bloino, J., Janesko, B. G., Gomperts, R., Mennucci, B., Hratchian, H. P., Ortiz, J. V., Izmaylov, A. F., Sonnenberg, J. L., Williams-Young, D., Ding, F., Lipparini, F., Egidi, F., Goings, J., Peng, B., Petrone, A., Henderson, T., Ranasinghe, D., Zakrzewski, V. G., Gao, J., Rega, N., Zheng, G., Liang, W., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Throssell, K., Montgomery, J. A. Jr., Peralta, J. E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M. J., Heyd, J. J., Brothers, E. N., Kudin, K. N., Staroverov, V. N., Keith, T. A., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A. P., Burant, J. C., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Millam, J. M., Klene, M., Adamo, C., Cammi, R., Ochterski, J. W., Martin, R. L., Morokuma, K., Farkas, O., Foresman, J. B., and Fox, D. J.: Gaussian 16 Revision C. 01. 2016, Gaussian Inc, Wallingford CT, 421, 2016. a

Glowacki, D. R., Wang, L., and Pilling, M. J.: Evidence of formation of bicyclic species in the early stages of atmospheric benzene oxidation, J. Phys. Chem. A, 113, 5385–5396, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9001466, 2009. a

Glowacki, D. R., Liang, C.-H., Morley, C., Pilling, M. J., and Robertson, S. H.: MESMER: an open-source master equation solver for multi-energy well reactions, J. Phys. Chem. A, 116, 9545–9560, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp3051033, 2012. a

Hallquist, M., Wenger, J. C., Baltensperger, U., Rudich, Y., Simpson, D., Claeys, M., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., George, C., Goldstein, A. H., Hamilton, J. F., Herrmann, H., Hoffmann, T., Iinuma, Y., Jang, M., Jenkin, M. E., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Maenhaut, W., McFiggans, G., Mentel, Th. F., Monod, A., Prévôt, A. S. H., Seinfeld, J. H., Surratt, J. D., Szmigielski, R., and Wildt, J.: The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 5155–5236, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-5155-2009, 2009. a

Hansen, J. E. and Sato, M.: Trends of measured climate forcing agents, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 14778–14783, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.261553698, 2001. a

Hasan, G., Salo, V.-T., Valiev, R. R., Kubecka, J., and Kurtén, T.: Comparing reaction routes for 3 (RO⋯OR′) intermediates formed in peroxy radical self- and cross-reactions, J. Phys. Chem. A, 124, 8305–8320, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.0c05960, 2020. a, b

Henriksen, N. E. and Hansen, F. Y.: Theories of molecular reaction dynamics: the microscopic foundation of chemical kinetics, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198805014.001.0001, 2018. a

Hinsberg, W. and Houle, F.: Kinetiscope: A stochastic kinetics simulator, http://hinsberg.net/kinetiscope (last access: 27 July 2020), 2017. a

Hippler, H., Troe, J., and Wendelken, H.: Collisional deactivation of vibrationally highly excited polyatomic molecules. II. Direct observations for excited toluene, J. Chem. Phys., 78, 6709–6717, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.444670, 1983. a

Huang, R.-J., Zhang, Y., Bozzetti, C., Ho, K.-F., Cao, J.-J., Han, Y., Daellenbach, K. R., Slowik, J. G., Platt, S. M., and Canonaco, F., Zotter, P., Wolf, R., Pieber, S. M., Bruns, E. A., Crippa, M., Ciarelli, G., Piazzalunga, A., Schwikowski, M., Abbaszade, G., Schnelle-Kreis, J., Zimmermann, R., An, Z., Szidat, S., Baltensperger, U., El Haddad, I., and Prévôt, A. S. H: High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China, Nature, 514, 218–222, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13774, 2014. a

Hyttinen, N., Kupiainen-Maatta, O., Rissanen, M. P., Muuronen, M., Ehn, M., and Kurtén, T.: Modeling the charging of highly oxidized cyclohexene ozonolysis products using nitrate-based chemical ionization, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 6339–6345, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b01818, 2015. a

Iuga, C., Sainz-Díaz, C. I., and Vivier-Bunge, A.: On the OH initiated oxidation of C2–C5 aliphatic aldehydes in the presence of mineral aerosols, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 74, 3587–3597, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2010.01.034, 2010. a

Iyer, S., Reiman, H., Møller, K. H., Rissanen, M. P., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Kurtén, T.: Computational investigation of RO2+HO2 and RO2+RO2 reactions of monoterpene derived first-generation peroxy radicals leading to radical recycling, J. Phys. Chem. A, 122, 9542–9552, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.8b09241, 2018. a

Iyer, S., Rissanen, M. P., Valiev, R., Barua, S., Krechmer, J. E., Thornton, J., Ehn, M., and Kurtén, T.: Molecular mechanism for rapid autoxidation in α-pinene ozonolysis, Nat. Commun., 12, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21172-w, 2021. a

Jacobson, M., Hansson, H.-C., Noone, K., and Charlson, R.: Organic atmospheric aerosols: Review and state of the science, Rev. Geophys., 38, 267–294, https://doi.org/10.1029/1998RG000045, 2000. a

Jenkin, M. E., Valorso, R., Aumont, B., Rickard, A. R., and Wallington, T. J.: Estimation of rate coefficients and branching ratios for gas-phase reactions of OH with aliphatic organic compounds for use in automated mechanism construction, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 9297–9328, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-9297-2018, 2018. a, b

Jokinen, T., Sipilä, M., Richters, S., Kerminen, V.-M., Paasonen, P., Stratmann, F., Worsnop, D., Kulmala, M., Ehn, M., Herrmann, H., and Berndt, T.: Rapid autoxidation forms highly oxidized RO2 radicals in the atmosphere, Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 53, 14596–14600, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201408566, 2014. a

Kanakidou, M., Seinfeld, J. H., Pandis, S. N., Barnes, I., Dentener, F. J., Facchini, M. C., Van Dingenen, R., Ervens, B., Nenes, A., Nielsen, C. J., Swietlicki, E., Putaud, J. P., Balkanski, Y., Fuzzi, S., Horth, J., Moortgat, G. K., Winterhalter, R., Myhre, C. E. L., Tsigaridis, K., Vignati, E., Stephanou, E. G., and Wilson, J.: Organic aerosol and global climate modelling: a review, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 1053–1123, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-1053-2005, 2005. a

Kendall, R. A., Dunning Jr., T. H., and Harrison, R. J.: Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions, J. Chem. Phys., 96, 6796–6806, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.462569, 1992. a

Kwok, E. S., Arey, J., and Atkinson, R.: Alkoxy radical isomerization in the OH radical-initiated reactions of C4–C8 n-alkanes, J. Phys. Chem., 100, 214–219, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp952036x, 1996. a

Laden, F., Schwartz, J., Speizer, F. E., and Dockery, D. W.: Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities study, Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care, 173, 667–672, https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200503-443OC, 2006. a

Lim, Y. B. and Ziemann, P. J.: Products and mechanism of secondary organic aerosol formation from reactions of n-alkanes with OH radicals in the presence of NOx, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 9229–9236, https://doi.org/10.1021/es051447g, 2005. a

Lim, Y. B. and Ziemann, P. J.: Effects of molecular structure on aerosol yields from OH radical-initiated reactions of linear, branched, and cyclic alkanes in the presence of NOx, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 2328–2334, https://doi.org/10.1021/es803389s, 2009. a

Lipari, F., Dasch, J. M., and Scruggs, W. F.: Aldehyde emissions from wood-burning fireplaces, Environ. Sci. Technol., 18, 326–330, https://doi.org/10.1021/es00123a007, 1984. a

Manion, J., Huie, R., Levin, R., Burgess Jr., D., Orkin, V., Tsang, W., McGivern, W., Hudgens, J., Knyazev, V., Atkinson, D., Chai, E., Tereza, A. M., Lin, C. Y., Allison, T. C., Mallard, W. G., Westley, F., Herron, J. T., Hampson, R. F., and Frizzell, D. H.: Nist chemical kinetics database, nist standard reference database 17, version 7.0 (web version), release 1.6.8, data version 2015.09, National Institute of Standards and Technology, MD, 2015. a

Mehra, A., Canagaratna, M., Bannan, T. J., Worrall, S. D., Bacak, A., Priestley, M., Liu, D., Zhao, J., Xu, W., Sun, Y., Hamilton, J. F., Squires, F. A., Lee, J., Bryant, D. J., Hopkins, J. R., Elzein, A., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Cheng, X., Chen, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, L., Stark, H., Krechmer, J. E., Brean, J., Slater, E., Whalley, L., Heard, D., Ouyang, B., Acton, W. J. F., Hewitt, C. N., Wang, X., Fu, P., Jayne, J., Worsnop, D., Allan, J., Percival, C., and Coe, H.: Using highly time-resolved online mass spectrometry to examine biogenic and anthropogenic contributions to organic aerosol in Beijing, Faraday Discuss., 226, 382–408, https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FD00080A, 2021. a

Mellouki, A., Le Bras, G., and Sidebottom, H.: Kinetics and mechanisms of the oxidation of oxygenated organic compounds in the gas phase, Chem. Rev., 103, 5077–5096, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020526x, 2003. a, b, c

Mellouki, A., Wallington, T., and Chen, J.: Atmospheric chemistry of oxygenated volatile organic compounds: impacts on air quality and climate, Chem. Rev., 115, 3984–4014, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr500549n, 2015. a, b, c

Mentel, T. F., Springer, M., Ehn, M., Kleist, E., Pullinen, I., Kurtén, T., Rissanen, M., Wahner, A., and Wildt, J.: Formation of highly oxidized multifunctional compounds: autoxidation of peroxy radicals formed in the ozonolysis of alkenes – deduced from structure–product relationships, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 6745–6765, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-6745-2015, 2015. a

Møller, K. H., Otkjær, R. V., Hyttinen, N., Kurtén, T., and Kjaergaard, H. G.: Cost-effective implementation of multiconformer transition state theory for peroxy radical hydrogen shift reactions, J. Phys. Chem. A, 120, 10072–10087, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.6b09370, 2016. a, b, c

Møller, K. H., Otkjær, R. V., Chen, J., and Kjaergaard, H. G.: Double bonds are key to fast unimolecular reactivity in first-generation monoterpene hydroxy peroxy radicals, J. Phys. Chem. A, 124, 2885–2896, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.0c01079, 2020. a

Newland, M. J., Bryant, D. J., Dunmore, R. E., Bannan, T. J., Acton, W. J. F., Langford, B., Hopkins, J. R., Squires, F. A., Dixon, W., Drysdale, W. S., Ivatt, P. D., Evans, M. J., Edwards, P. M., Whalley, L. K., Heard, D. E., Slater, E. J., Woodward-Massey, R., Ye, C., Mehra, A., Worrall, S. D., Bacak, A., Coe, H., Percival, C. J., Hewitt, C. N., Lee, J. D., Cui, T., Surratt, J. D., Wang, X., Lewis, A. C., Rickard, A. R., and Hamilton, J. F.: Low-NO atmospheric oxidation pathways in a polluted megacity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 1613–1625, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-1613-2021, 2021. a

Öström, E., Putian, Z., Schurgers, G., Mishurov, M., Kivekäs, N., Lihavainen, H., Ehn, M., Rissanen, M. P., Kurtén, T., Boy, M., Swietlicki, E., and Roldin, P.: Modeling the role of highly oxidized multifunctional organic molecules for the growth of new particles over the boreal forest region, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 8887–8901, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-8887-2017, 2017. a

Rissanen, M. P.: NO2 Suppression of autoxidation–inhibition of gas-phase highly oxidized dimer product formation, ACS Earth Space Chem., 2, 1211–1219, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.8b00123, 2018. a, b

Rissanen, M. P., Kurtén, T., Sipilä, M., Thornton, J. A., Kangasluoma, J., Sarnela, N., Junninen, H., Jørgensen, S., Schallhart, S., Kajos, M. K., Taipale, R., Springer, M., Mentel, T. F., Ruuskanen, T., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D. R., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Ehn, M.: The formation of highly oxidized multifunctional products in the ozonolysis of cyclohexene, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 136, 15596–15606, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja507146s, 2014. a, b, c

Rissanen, M. P., Kurtén, T., Sipilä, M., Thornton, J. A., Kausiala, O., Garmash, O., Kjaergaard, H. G., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D. R., Ehn, M., and Kulmala, M.: Effects of chemical complexity on the autoxidation mechanisms of endocyclic alkene ozonolysis products: From methylcyclohexenes toward understanding α-pinene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 4633–4650, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp510966g, 2015. a, b

Russell, G. A.: Deuterium-isotope effects in the autoxidation of aralkyl hydrocarbons. Mechanism of the interaction of peroxy radicals1, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 79, 3871–3877, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01571a068, 1957. a

Schauer, J. J., Kleeman, M. J., Cass, G. R., and Simoneit, B. R.: Measurement of emissions from air pollution sources. 1. C1 through C29 organic compounds from meat charbroiling, Environ. Sci. Technol., 33, 1566–1577, https://doi.org/10.1021/es980076j, 1999a. a

Schauer, J. J., Kleeman, M. J., Cass, G. R., and Simoneit, B. R.: Measurement of emissions from air pollution sources. 2. C1 through C30 organic compounds from medium duty diesel trucks, Environ. Sci. Technol., 33, 1578–1587, https://doi.org/10.1021/es980081n, 1999b. a

Spracklen, D. V., Jimenez, J. L., Carslaw, K. S., Worsnop, D. R., Evans, M. J., Mann, G. W., Zhang, Q., Canagaratna, M. R., Allan, J., Coe, H., McFiggans, G., Rap, A., and Forster, P.: Aerosol mass spectrometer constraint on the global secondary organic aerosol budget, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 12109–12136, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-12109-2011, 2011. a

Tröstl, J., Chuang, W. K., Gordon, H., Heinritzi, M., Yan, C., Molteni, U., Ahlm, L., Frege, C., Bianchi, F., Wagner, R., Simon, M., Lehtipalo, K., Williamson, C., Craven, J. S., Duplissy, J., Adamov, A., Almeida, J., Bernhammer, A.-K., Breitenlechner, M., Brilke, S., Dias, A., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Fuchs, C., Guida, R., Gysel, M., Hansel, A., Hoyle, C. R., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kangasluoma, J., Keskinen, H., Kim, J., Krapf, M., Kürten, A., Laaksonen, A., Lawler, M., Leiminger, M., Mathot, S., Möhler, O., Nieminen, T., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Piel, F. M., Miettinen, P., Rissanen, M. P., Rondo, L., Sarnela, N., Schobesberger, S., Sengupta, K., Sipilä, M., Smith, J. N., Steiner, G., Tomè, A., Virtanen, A., Wagner, A. C., Weingartner, E., Wimmer, D., Winkler, P. M., Ye, P., Carslaw, K. S., Curtius, J., Dommen, J., Kirkby, J., Kulmala, M., Riipinen, I., Worsnop, D. R., Donahue, N. M., and Baltensperger, U.: The role of low-volatility organic compounds in initial particle growth in the atmosphere, Nature, 533, 527–531, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18271, 2016. a, b

Valiev, R. R., Hasan, G., Salo, V.-T., Kubecka, J., and Kurtén, T.: Intersystem crossings drive atmospheric gas-phase dimer formation, J. Phys. Chem. A, 123, 6596–6604, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.9b02559, 2019. a

Vandenberk, S. and Peeters, J.: The reaction of acetaldehyde and propionaldehyde with hydroxyl radicals: experimental determination of the primary H2O yield at room temperature, J. Photoch. Photobio. A, 157, 269–274, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1010-6030(03)00063-7, 2003. a, b

Vereecken, L. and Nozière, B.: H migration in peroxy radicals under atmospheric conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 7429–7458, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-7429-2020, 2020. a, b, c, d, e

Vereecken, L. and Peeters, J.: Decomposition of substituted alkoxy radicals–part I: a generalized structure–activity relationship for reaction barrier heights, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 11, 9062–9074, https://doi.org/10.1039/B909712K, 2009. a

Vereecken, L. and Peeters, J.: A structure–activity relationship for the rate coefficient of H-migration in substituted alkoxy radicals, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 12, 12608–12620, https://doi.org/10.1039/C0CP00387E, 2010. a

Viegas, L. P.: Exploring the reactivity of hydrofluoropolyethers toward OH through a cost-effective protocol for calculating multiconformer transition state theory rate constants, J. Phys. Chem. A, 122, 9721–9732, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.8b08970, 2018. a

Viegas, L. P. and Jensen, F.: A computer-based solution to the oxidation kinetics of fluorinated and oxygenated volatile organic compounds, Environ. Sci. Atmos., 3, 855–871, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EA00164K, 2023. a, b

Wang, S., Davidson, D. F., and Hanson, R. K.: High temperature measurements for the rate constants of C1–C4 aldehydes with OH in a shock tube, P. Combust. Inst., 35, 473–480, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proci.2014.06.112, 2015. a

Wang, Z., Ehn, M., Rissanen, M. P., Garmash, O., Quéléver, L., Xing, L., Monge-Palacios, M., Rantala, P., Donahue, N. M., Berndt, T., and Sarathy, S. M.: Efficient alkane oxidation under combustion engine and atmospheric conditions, Commun. Chem., 4, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-020-00445-3, 2021. a, b

Wavefunction Inc.: Spartan'18, Irvine, CA, USA, https://www.wavefun.com/ (last access: 11 February 2022), 2018. a

Werner, H., Knowles, P., Knizia, G., Manby, F., Schütz, M., Celani, P., Györffy, W., Kats, D., Korona, T., Lindh, R., Mitrushenkov, A., Rauhut, G., Shamasundar, K. R., Adler, T. B., Amos, R. D., Bennie, S. J., Bernhardsson, A., Berning, A., Cooper, D. L., Deegan, M. J. O., Dobbyn, A. J., Eckert, F., Goll, E., Hampel, C., Hesselmann, A., Hetzer, G., Hrenar, T., Jansen, G., Köppl, C., Lee, S. J. R., Liu, Y., Lloyd, A. W., Ma, Q., Mata, R. A., May, A. J., McNicholas, S. J., Meyer, W., Miller, T. F., Mura, M. E., Nicklass, A., O'Neill, D. P., Palmieri, P., Peng, D., Pflüger, K., Pitzer, R., Reiher, M., Shiozaki, T., Stoll, H., Stone, A. J., Tarroni, R., Thorsteinsson, T., Wang, M., and Welborn, M.: MOLPRO, version 2019.2, a package of ab initio programs, Cardiff, UK, 2019. a

Xu, L., Møller, K. H., Crounse, J. D., Otkjær, R. V., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Unimolecular reactions of peroxy radicals formed in the oxidation of α-pinene and β-pinene by hydroxyl radicals, J. Phys. Chem. A, 123, 1661–1674, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.8b11726, 2019. a

Zhang, X., Cappa, C. D., Jathar, S. H., McVay, R. C., Ensberg, J. J., Kleeman, M. J., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Influence of vapor wall loss in laboratory chambers on yields of secondary organic aerosol, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 5802–5807, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1404727111, 2014. a

Ziemann, P. J. and Atkinson, R.: Kinetics, products, and mechanisms of secondary organic aerosol formation, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6582–6605, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CS35122F, 2012. a, b