the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Model evaluation of short-lived climate forcers for the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme: a multi-species, multi-model study

Cynthia H. Whaley

Rashed Mahmood

Knut von Salzen

Barbara Winter

Sabine Eckhardt

Stephen Arnold

Stephen Beagley

Silvia Becagli

Rong-You Chien

Jesper Christensen

Sujay Manish Damani

Xinyi Dong

Konstantinos Eleftheriadis

Nikolaos Evangeliou

Gregory Faluvegi

Mark Flanner

Joshua S. Fu

Michael Gauss

Fabio Giardi

Wanmin Gong

Jens Liengaard Hjorth

Lin Huang

Yugo Kanaya

Srinath Krishnan

Zbigniew Klimont

Thomas Kühn

Joakim Langner

Kathy S. Law

Louis Marelle

Andreas Massling

Dirk Olivié

Tatsuo Onishi

Naga Oshima

Yiran Peng

David A. Plummer

Olga Popovicheva

Luca Pozzoli

Jean-Christophe Raut

Maria Sand

Laura N. Saunders

Julia Schmale

Sangeeta Sharma

Ragnhild Bieltvedt Skeie

Henrik Skov

Fumikazu Taketani

Manu A. Thomas

Rita Traversi

Kostas Tsigaridis

Svetlana Tsyro

Steven Turnock

Vito Vitale

Kaley A. Walker

Minqi Wang

Duncan Watson-Parris

Tahya Weiss-Gibbons

While carbon dioxide is the main cause for global warming, modeling short-lived climate forcers (SLCFs) such as methane, ozone, and particles in the Arctic allows us to simulate near-term climate and health impacts for a sensitive, pristine region that is warming at 3 times the global rate. Atmospheric modeling is critical for understanding the long-range transport of pollutants to the Arctic, as well as the abundance and distribution of SLCFs throughout the Arctic atmosphere. Modeling is also used as a tool to determine SLCF impacts on climate and health in the present and in future emissions scenarios.

In this study, we evaluate 18 state-of-the-art atmospheric and Earth system models by assessing their representation of Arctic and Northern Hemisphere atmospheric SLCF distributions, considering a wide range of different chemical species (methane, tropospheric ozone and its precursors, black carbon, sulfate, organic aerosol, and particulate matter) and multiple observational datasets. Model simulations over 4 years (2008–2009 and 2014–2015) conducted for the 2022 Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) SLCF assessment report are thoroughly evaluated against satellite, ground, ship, and aircraft-based observations. The annual means, seasonal cycles, and 3-D distributions of SLCFs were evaluated using several metrics, such as absolute and percent model biases and correlation coefficients. The results show a large range in model performance, with no one particular model or model type performing well for all regions and all SLCF species. The multi-model mean (mmm) was able to represent the general features of SLCFs in the Arctic and had the best overall performance. For the SLCFs with the greatest radiative impact (CH4, O3, BC, and SO), the mmm was within ±25 % of the measurements across the Northern Hemisphere. Therefore, we recommend a multi-model ensemble be used for simulating climate and health impacts of SLCFs.

Of the SLCFs in our study, model biases were smallest for CH4 and greatest for OA. For most SLCFs, model biases skewed from positive to negative with increasing latitude. Our analysis suggests that vertical mixing, long-range transport, deposition, and wildfires remain highly uncertain processes. These processes need better representation within atmospheric models to improve their simulation of SLCFs in the Arctic environment. As model development proceeds in these areas, we highly recommend that the vertical and 3-D distribution of SLCFs be evaluated, as that information is critical to improving the uncertain processes in models.

- Article

(19748 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1745 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The Arctic atmosphere is warming 3 times more quickly than the global average (Bush and Lemmen, 2019; NOAA, 2020; AMAP, 2021; IPCC, 2021). Arctic warming is a manifestation of global warming, and the main driver for this is the increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) radiative forcing (IPCC, 2021). Arctic warming is amplified by sea ice and snow feedbacks and affected by local radiative forcings in the Arctic, including radiative forcings by short-lived climate forcers (SLCFs), such as methane, black carbon, and tropospheric ozone (AMAP, 2015a, b, 2022). The remote pristine Arctic environment is sensitive to the long-range transport of atmospheric pollutants and deposition (Schmale et al., 2021). At the same time, it is difficult to carry out in situ measurements (Nguyen et al., 2016; Freud et al., 2017) and satellite observations over the Arctic. The majority of the Arctic surface is ocean covered with sea ice that is usually adrift for most of the year. The Arctic environment is also harsh. These aspects have historically kept surface-based measurements sparse. The overwhelming majority of the satellite observations either depend on the visible spectrum, are limited by the presence of clouds, or have very low sensitivity in the lower troposphere where the atmospheric processes mainly determine the fate of the pollutants. Many satellite measurements also do not have good coverage in the Arctic, given their orbital parameters or problems measuring areas with high albedo (Beer, 2006).

Modeling the Arctic atmosphere comes with its own challenges due to extreme meteorological conditions, its great distance from major global pollution sources, poorly known local emissions, high gradients in physical and chemical fields, and a singularity in some model grids at the pole. Models have been improving in the last 2 decades, but many models still have inaccurate results in the Arctic (Shindell et al., 2008; Eckhardt et al., 2015; Emmons et al., 2015; Sand et al., 2017; Marelle et al., 2018). That said, there has recently been a number of improvements in numerous models that have allowed for better representation of certain processes (Morgenstern et al., 2017; Emmons et al., 2020a; Swart et al., 2019; Holopainen et al., 2020; Im et al., 2021). In this study, model simulations for the 2021 Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) SLCF assessment report (AMAP, 2022) have been thoroughly evaluated by comparison to several freely available observational datasets in the Northern Hemisphere and assessed in more detail in the Arctic. In order to support the integrated assessment of climate and human health for AMAP, 6 SLCF species (methane – CH4, ozone – O3, black carbon – BC, sulfate – SO, organic aerosol – OA, and fine particulate matter – PM2.5) and 2 O3 precursors (carbon monoxide – CO; nitrogen dioxide – NO2) from 18 atmospheric or Earth system models are compared to numerous observational datasets (from three satellite instruments, seven monitoring networks, and nine measurement campaigns) for 4 years (2008–2009 and 2014–2015), with the goal of answering the following questions.

- 1.

How well do the AMAP SLCF models perform in the context of measurements and their associated uncertainty?

-

What do the best-performing models have in common?

-

Are there regional patterns in the model biases?

-

Are there patterns in the model biases between SLCF species?

- 2.

How does the model performance impact model applications, such as simulated climate and health impacts?

- 3.

What processes should be improved or studied further for better model performance?

Out of scope of this study are any sensitivity tests by the models to assess different components of model errors. Also out of scope are the models' simulations of aerosol optical properties and cloud properties (e.g., cloud fraction, cloud droplet number concentration, cloud scavenging), though those parameters do have a large impact on climate and a tight relationship with some SLCFs. Their initial evaluation can be found in AMAP (2022) (chap. 7). Estimates of effective radiative forcings of SLCFs in the Arctic by the AMAP participating models are also provided elsewhere (Oshima et al., 2020).

The next section summarizes the models used in this study, with more information in the Appendix. Section 3 summarizes the measurements used for model evaluation. Section 4 presents our model evaluation for each SLCF species, followed by a summary of all SLCFs. Finally, Sect. 5 is the conclusion where the questions posed above are answered.

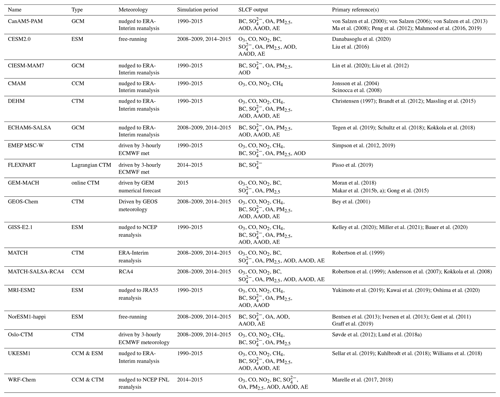

In this section we briefly describe the models used for the AMAP SLCF study and refer the reader to Appendix A for individual model descriptions and further information. All models were run globally with the same anthropogenic emissions dataset (see Sect. 2.1), and most were run for the years 2008–2009 (as was done for the 2015 AMAP assessment report) and 2014–2015 (to evaluate more recent model results) inclusive for this evaluation, as these were years with numerous Arctic measurements. Unless otherwise indicated, all model output was monthly-averaged.

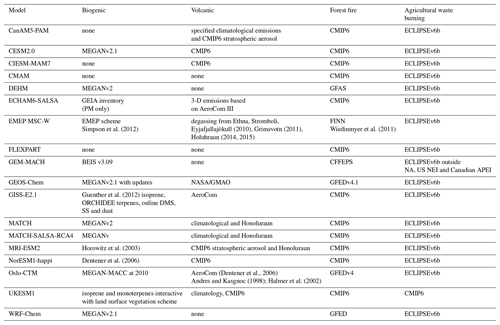

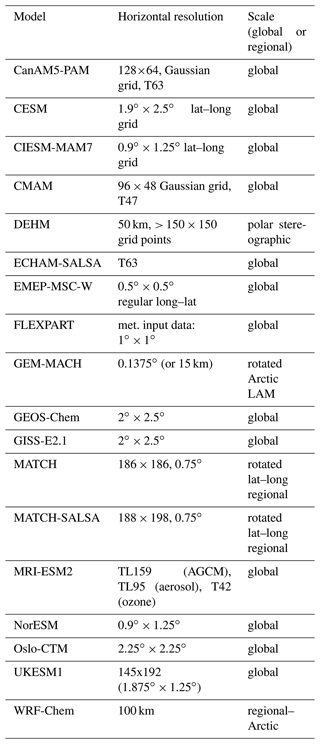

The models used for this study are summarized in Table 1. As is shown in the table, not all models provided all SLCF species, and not all models provided all 4 years. There were eight chemical transport models (CTMs), two chemistry–climate models (CCMs), three global climate models (GCMs), and five Earth system models (ESMs). Many models used specified or nudged meteorology, which allows the day-to-day variability of the model meteorology to be more closely aligned with the historical evolution of the atmosphere than occurs in a free-running model. The ERA-Interim reanalysis was the most commonly used meteorology (in 7 out of 18 models), but some were free-running (simulating their own meteorology) and some used other reanalysis products (Table 1).

von Salzen et al. (2000); von Salzen (2006); von Salzen et al. (2013)Ma et al. (2008); Peng et al. (2012); Mahmood et al. (2016, 2019)Danabasoglu et al. (2020)Liu et al. (2016)Lin et al. (2020); Liu et al. (2012)Jonsson et al. (2004)Scinocca et al. (2008)Christensen (1997); Brandt et al. (2012); Massling et al. (2015)Tegen et al. (2019); Schultz et al. (2018); Kokkola et al. (2018)Simpson et al. (2012, 2019)Pisso et al. (2019)Moran et al. (2018)Makar et al. (2015b, a); Gong et al. (2015)Bey et al. (2001)Kelley et al. (2020); Miller et al. (2021); Bauer et al. (2020)Robertson et al. (1999)Robertson et al. (1999); Andersson et al. (2007); Kokkola et al. (2008)Yukimoto et al. (2019); Kawai et al. (2019); Oshima et al. (2020)Bentsen et al. (2013); Iversen et al. (2013); Gent et al. (2011)Graff et al. (2019)Søvde et al. (2012); Lund et al. (2018a)Sellar et al. (2019); Kuhlbrodt et al. (2018); Williams et al. (2018)Marelle et al. (2017, 2018)Table 1Summary of models used in this study. GCM: global climate model, CCM: chemistry–climate model, ESM: Earth system model, CTM: chemical transport model.

2.1 Emissions

All models used the same anthropogenic emissions dataset, which is called ECLIPSE (Evaluating the Climate and Air Quality Impacts of Short-Lived Pollutants) v6B. These emissions were created using the IIASA-GAINS (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis – Greenhouse gas – Air pollution Interactions and Synergies) model (Amann et al., 2011; Klimont et al., 2017; Höglund-Isaksson et al., 2020), which provides emissions of long-lived greenhouse gases and shorter-lived species in a consistent framework. These historical emissions were provided for the years 1990 to 2015 at 5-year intervals, as well as the years 2008–2009 and 2014. Those models that simulated the 1990–2015 time period linearly interpolated the emissions for the years in between. The ECLIPSEv6b emissions include many pollutants, such as CH4, CO, NOx, BC, and SO2. They include the significant sulfur emission reductions that have taken place since the 1980s (Grennfelt et al., 2020). Global anthropogenic BC emissions are estimated to be 6.5 Tg in 2010 and 5.9 Tg in 2020, and global anthropogenic SO2 emissions are estimated to be 90 Tg in 2010 but declined significantly over the subsequent decade to 50 Tg (AMAP, 2022). The reductions are mainly due to stringent emissions standards in the energy and industrial sectors, as well as reduced coal use in the residential sector (AMAP, 2022). Global anthropogenic methane emissions were 340 Tg in 2015 and 350 Tg in 2020, and they are expected to continue to increase, unlike BC and SO2. The largest methane sources in 2015 were agriculture (42 % of total emissions), oil and gas (extraction and distribution) (18 %), waste (18 %), and energy production (including coal mining) (16 %) (AMAP, 2022; Höglund-Isaksson et al., 2020). CO and NOx emissions have been declining steadily and are expected to continue declining in the future.

In comparison to the CMIP6 emissions (Hoesly et al., 2018), ECLIPSEv6b emissions have additionally taken into account the recent declines in emissions from Asia of SO2, BC, and NOx due to recent control measures, whereas those declines in the CMIP6 emissions were unrealistically small (Wang et al., 2021; von Salzen et al., 2022). The inclusion of emissions from the flaring sector in Russia was a significant improvement, which was not present in the previous version of ECLIPSE emissions that was used in the AMAP (2015a) report.

For non-agricultural fire emissions, many models utilized the CMIP6 fire emissions, which are based on monthly GFED (Global Fire Emissions Database) v4.1 (van Marle et al., 2017). About half of the models included volcanic emissions or stratospheric aerosol concentrations from the CMIP6 dataset (Thomason et al., 2018) or other sources, and the other half did not include volcanic emissions, which mainly impact SO2 and thus modeled SO. The emissions from the October to December 2014 Honoluraun volcano eruption (Gíslason et al., 2015; Twigg et al., 2016; Ilyinskaya et al., 2017) were included by six models in a separate set of simulations. Similar differences in biogenic and agricultural waste emissions appear in these model simulations, and all are summarized in Table 2.

Simpson et al. (2012)Wiedinmyer et al. (2011)Guenther et al. (2012)Horowitz et al. (2003)Dentener et al. (2006)Dentener et al., 2006Andres and Kasgnoc (1998); Halmer et al. (2002)2.2 Chemistry

This section contains a summary of models' chemistry schemes, and we refer the reader to Appendix A and references therein for more details.

2.2.1 Methane

All participating models that provided CH4 output prescribed CH4 concentrations based on box model results from Olivié et al. (2021) for 2015 and from Meinshausen et al. (2017) for years prior to 2015. The former utilized the ECLIPSE v6B anthropogenic CH4 emissions (Sect. 2.1), along with assumptions for the natural emissions (Olivié et al., 2021; Prather et al., 2012), to provide as input to models' surface or boundary layer CH4 concentrations. Models then allow CH4 to take part in photochemical processes, such as the production of tropospheric O3.

2.2.2 Tropospheric chemistry

There is a wide range of tropospheric gas-phase chemistry implemented in the models. Air-quality-focused models, such as DEHM, EMEP MSC-W, GEM-MACH, GEOS-Chem, MATCH, and WRF-Chem, have detailed HOx–NOx–hydrocarbon O3 chemistry, with speciated volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and secondary aerosol formation. The GISS-E2.1, MRI-ESM2, and UKESM1 ESMs also use this level of tropospheric chemistry. In contrast, climate-focused models like CanAM5-PAM, CIESM-MAM7, ECHAM-SALSA, and NorESM1 contain bare minimum gas-phase chemistry and use prescribed O3 fields (e.g., CanAM5-PAM uses CMAM climatological O3 fields). The CCMs are somewhere in between, with simplified tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry so that they could be run for longer time periods. For example, CMAM's tropospheric chemistry consists only of CH4–NOx–O3 chemistry, with no VOCs.

2.2.3 Stratospheric chemistry

Only a subset of the participating models have a fully simulated stratosphere. CMAM, MRI-ESM2, GISS-E2.1, OsloCTM, and UKESM1 contain a relatively complete description of the HOx, NOx, Clx, and Brx chemistry that controls stratospheric ozone along with the longer-lived source gases such as CH4, N2O, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Other models have a simplified stratosphere, such as GEOS-Chem, which has a linearized stratospheric chemistry scheme (Linoz, McLinden et al., 2000), and WRF-Chem, which specifies stratospheric concentrations from climatologies – both of which do not simulate stratospheric chemistry. Finally, several models have no stratosphere or stratospheric chemistry at all (e.g., CIESM-MAM7, GEM-MACH, DEHM, and EMEP MSC-W).

2.2.4 Aerosols

Most models contain speciated aerosols: mineral dust (also known as crustal material), sea salt, BC, OA (sometimes separated into primary and secondary), SO, nitrate (NO), and ammonium (NH). However, some, like CanAM5-PAM and UKESM1, do not simulate NO and NH, but assume all is in the form (NH4)2SO. OA, SO, NO, and NH are involved in chemical reactions interacting with the gas-phase chemistry. Aerosol size distributions are either prescribed or discretized into lognormal modes or size sections. How the aerosol size distribution varies in space and time depends on many different processes, including emission, aerosol microphysics, aerosol–cloud interactions, and removal. How these processes are parameterized depends on the model, and we refer the reader to the Appendix and the references therein for more detail.

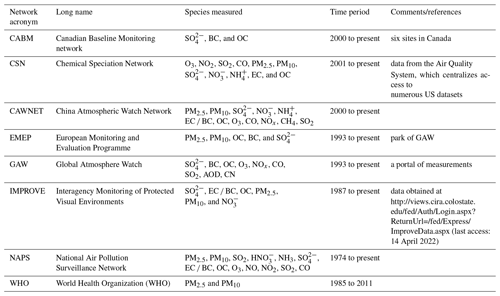

We have utilized many freely available observational datasets of SLCFs to evaluate the models. General descriptions are given below under the broad headings of surface monitoring, satellite, and campaign datasets, and there is some additional information in Appendix B.

3.1 Surface monitoring datasets

3.1.1 CH4 and O3

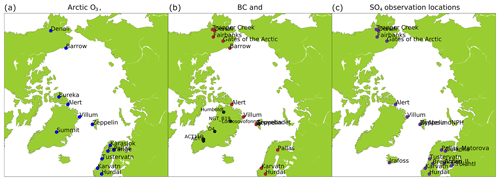

Global surface CH4 measurements were obtained from the World Data Centre for Greenhouse Gases (WDCGG). These measurements were made via gas chromatography, which has a < 1 % uncertainty range. Surface in situ O3 measurements are typically made via various types of UV absorption monitors, employing the Beer–Lambert law to relate UV absorption of O3 at 254 nm directly to the concentration of O3 in the sample air (e.g., Bauguitte, 2014), which have approximately a 3 % or 1–2 ppbv uncertainty range. We obtained surface O3 measurements from various networks: the National Air Pollutant Surveillance Program (NAPS) and the Canadian Pollutant Monitoring Network (CAPMON) for Canada, the Chemical Speciation Network (CSN) for the US, the Beijing Air Quality and Hong Kong Environmental Protection Agency for China, the Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory (CMDL) for some global sites, the European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme (EMEP), and some individual Arctic monitoring stations like Villum Research Station and Zeppelin Mountain. Many of these measurements were downloaded from the EBAS database. The Arctic O3 measurement locations are shown in Fig. 1.

3.1.2 CO, NO, and NO2

CO and NOx measurements were obtained from the same monitoring networks as O3. CO instrumentation is similar to that for O3; however, it uses gas filter correlation to relate infrared absorption of CO at 4.6 µm to the concentration of CO in the sample air (Biraud, 2011). For NOx, the instrument deploys the characteristic chemiluminescence produced by the reaction between NO and O3, the intensity of which is proportional to the NO concentration. NO2 measurements are approximated using its thermal reduction to NO by a heated (350∘C) molybdenum converter (Bauguitte, 2014). Note that this method has an estimated bias of about 5 %–20 % because of sensitivity to other oxidized nitrogen species, and this has not been corrected for. The bias is on the lower end for high-NOx conditions and in the low-NOx Arctic can be up to 100 % uncertainty.

3.1.3 BC and OA

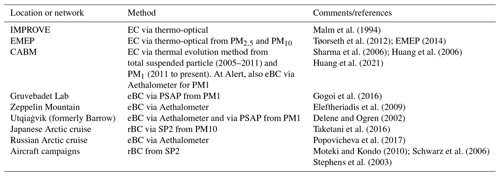

There are various BC measurement methods exploiting different properties of BC and thus measuring different quantities (Petzold et al., 2013): elemental carbon (EC) determined by thermal and/or thermal–optical methods, equivalent BC (eBC) by optical absorption methods, and refractory BC (rBC) by incandescence methods. Table B1 in Appendix B lists the different measurement techniques and instruments that the different monitoring networks and individual Arctic monitoring stations use. As BC emission inventories, including ECLIPSEv6b, are mainly based on emission factors derived from thermal and/or thermal–optical methods, modeled BC is consequently representative of EC.

The different types of BC measurements (EC, eBC, and rBC) usually agree with each other within a factor of 2 (AMAP, 2022; Pileci et al., 2021). However, it has been shown that, as the aerosol ages, the complex state of mixing of BC particles causes eBC to increase relative to EC (Zanatta et al., 2018). The absorption and scattering cross sections of coated BC particles vary by more than a factor of 2 due to different coating structures. He et al. (2015) found an increase of 20 %–250 % in absorption during aging, significantly depending on coating morphology and aging stages. Thus, this complexity impacts model–measurement comparisons at remote Arctic locations where one would expect eBC to have a high, positive uncertainty.

We obtained BC from the Canadian Aerosol Baseline Measurement (CABM) network for Canada, Interagency Monitoring of Protected Visual Environments (IMPROVE) network for the US, the EMEP network for Europe, and individual Arctic locations. To our knowledge, there were no other freely accessible BC measurements. The major observing networks EMEP, CABM, and IMPROVE measure EC with approximately 10 % uncertainty (Sharma et al., 2017). However, given the complexities in different BC measurement types, as mentioned above, the overall uncertainty is about 200 %.

Another complexity with model evaluation of BC is that some of the eBC measurements that models are compared to were made from collected particulate matter with different maximum diameters (e.g., PM1, PM2.5, and PM10). These are included in Table B1 for each of the measurement locations. From the models we use BC from PM2.5, as most of the BC is expected to be in the submicron mode.

Organic carbon (OC) is also measured via thermal and/or thermal–optical methods (Chow et al., 1993, 2001, 2004; Huang et al., 2006; Cavalli et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2021) using the same instrumentation as for EC detection in IMPROVE, CABM, NAPS, and EMEP measurement networks. These OC measurements have approximately 20 % or less uncertainty (Chan et al., 2019). Models output organic aerosol (OA), which includes OC and organic matter and is related to OC via a factor of 1.4 (Russell, 2003; Tsigaridis et al., 2014), though this factor has been reported as a range from 1.4 to 2.1 in the literature, depending on the source of OC and OA (Tsigaridis et al., 2014). Nevertheless, we applied a conversion factor of 1.4 to the OC measurements before comparing the modeled OA.

Arctic BC measurement locations are shown in Fig. 1, and many of these Arctic aerosol measurements were discussed in Schmale et al. (2022). We also evaluated modeled BC deposition by comparing it to BC deposition derived from ice core measurements (D4, ACT2: McConnell and Edwards, 2008; Humboldt: Bauer et al., 2013; Summit: Keegan et al., 2014; NGT_B19, ACT11D: McConnell et al., 2019). All of the ice core locations are also shown in Fig. 1. Deposition fluxes are not a measured value but are derived from the EC concentrations in ice and precipitation estimates.

3.1.4 SO

Surface in situ SO measurements in the major observing networks typically use ion chromatography methods, which have an approximately 3 % uncertainty range (Solomon et al., 2014). However, SO measurements have been shown to have up to 20 % analytical uncertainty (AMAP, 2022). SO datasets were obtained from IMPROVE, EMEP, and CABM networks, often via the EBAS database.

SO deposition was also derived from the same ice core measurements mentioned above for BC deposition (D4, ACT2: McConnell and Edwards, 2008; Humboldt: Bauer et al., 2013; Summit: Maselli et al., 2017; NGT_B19, ACT11D: McConnell et al., 2019). The Arctic SO measurement locations are shown in Fig. 1.

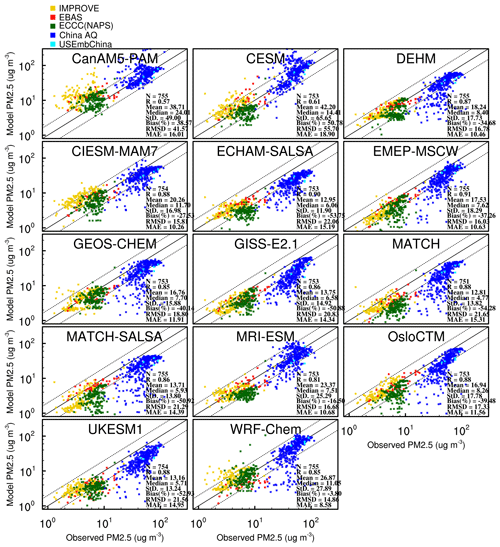

3.1.5 PM2.5

Surface in situ PM2.5 measurements are usually made via gravimetric analysis of particulate matter collected on a filter (e.g., Teflon substrate), which has around a 1 %–6 % uncertainty range (Malm et al., 2011). These data were obtained from Beijing Air Quality and US Embassy data for China, NAPS for Canada (Dabek-Zlotorzynska et al., 2011), IMRPROVE for the US, and EMEP and/or EBAS for Europe.

3.2 Satellite datasets

Satellite observations are useful for evaluating models on larger horizontal spatial scales and for evaluating the three-dimensional atmosphere – not the surface concentrations. Observations from three satellite instruments were used to evaluate model trace gas distributions in the free troposphere and, when appropriate, the lower stratosphere. These were the Tropospheric Emission Spectrometer version 7 (TES; NASA Atmospheric Science Data Centre, 2018; Gluck, 2004a, b), the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment–Fourier Transform Spectrometer version 4.1 (ACE-FTS; Bernath et al., 2005; Sheese and Walker, 2020), and the Measurements of Pollution in the Troposphere version 8 (MOPITT; Ziskin, 2000; Deeter et al., 2019). The vertical profiles of trace gas volume mixing ratios are derived or retrieved from the satellite-measured emission or absorption spectra, with varying degrees of vertical sensitivity. These remote techniques typically have about a 15 % uncertainty in the measurements (e.g., Verstraeten et al., 2013), though this depends on the specific instrument and the species retrieved (e.g., Sheese et al., 2017).

Note that while TES and MOPITT have global spatial coverage, their coverage does not extend up into the high Arctic. The TES instrument on NASA's Aura satellite measures vertical profiles of trace gases such as O3, CH4, NO2, CO, and HNO from 2004–present. After interpolating all models and TES results to a 1∘ × 1∘ horizontal grid, the monthly mean CH4 and O3 from the TES lite products were matched in space and time with models. Models were smoothed with the TES monthly mean averaging kernels prior to comparisons with satellite data. TES measurements started in 2004, stopped in late 2015, and had poorer coverage in the last few years.

A similar comparison method was used for MOPITT data. The MOPITT instrument on NASA's Terra satellite measures CO from 2000 to the present.

The ACE-FTS instrument on CSA's SCISAT satellite has measured the trace gases O3, CO, NO, NO2, and CH4, among over 30 others from 2004–present. SCISAT has a high-inclination orbit, giving its instruments better coverage in the Arctic. ACE-FTS is a limb-sounding instrument measuring the solar absorption spectra of dozens of trace gas concentrations from the upper troposphere to the thermosphere. This gives us the opportunity to evaluate the 3-D model output in a region of the atmosphere where the radiative forcing of ozone is at its highest. Evaluating models with ACE-FTS measurements also provides insight into models' transport and upper-tropospheric chemistry. As was shown in Kolonjari et al. (2018), 3-hourly model output (rather than monthly mean output) is required for accurate comparisons to ACE-FTS data; thus, only models that provided output at this time frequency were compared to ACE-FTS measurements. The model output was sampled to match the times and locations of ACE-FTS measurements. We used an updated version of the advanced method in Kolonjari et al. (2018). Instead of taking the model output at the closest time to the ACE-FTS measurement time, the model output was linearly interpolated onto the ACE-FTS time. This reduces the bias introduced by diurnal cycles, which can cause certain volume mixing ratios (VMRs; e.g., that of NO and NO2) to vary significantly between model output times. As in Kolonjari et al. (2018), the model output is also interpolated vertically in log pressure space and bilinearly in latitude and longitude to account for spatial variation between model grid points.

3.3 Measurement campaigns

Finally, there were air- and ship-based measurement campaigns of black carbon that were used for model evaluation. Aircraft campaigns allow vertical profiles of chemical species to be evaluated, and ship campaigns allow for in situ measurements in the remote Arctic seas.

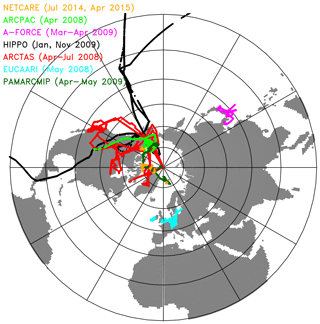

3.3.1 Aircraft campaigns

The flight paths of the aircraft used for model evaluation of BC are shown in Fig. 2. The aircraft campaigns include A-FORCE (Oshima et al., 2012), ARCPAC (Brock et al., 2011), ARCTAS (Jacob et al., 2010), EUCAARI (Hamburger et al., 2011), HIPPO (Schwarz et al., 2010), NETCARE (Schulz et al., 2019), and PAMARCMIP (Stone et al., 2010). Most of these aircraft campaigns occurred during boreal spring and summer months (April to July) except for one (HIPPO) occurring in January and November, and most occurred during the 2008–2009 time period, with only one (NETCARE) occurring during 2014–2015. All of these aircraft campaigns measured rBC from single-particle soot photometers (SP2) (Moteki and Kondo, 2010; Schwarz et al., 2006; Stephens et al., 2003).

The AMAP models that submitted 3-hourly BC output were linearly interpolated onto the aircraft locations in space and time using the Community Intercomparison Suite (CIS; Watson-Parris et al., 2016) in order to provide representative comparisons and robust evaluation.

3.3.2 Ship campaigns

There were three ship-based measurement campaigns in 2014–2015. These were the two Japanese campaigns (MR14-05 and MR15-03 cruises of R/V Mirai) in September of 2014 and 2015 (track from Japan to north of Alaska; Taketani et al., 2016) and the Russian campaign in October 2015 (track north of Russia, from Arkhangelsk to Severnaya Zemlya and back; Popovicheva et al., 2017) – both are shown in Sect. 4.5 (Fig. 17). Models that provided 3-hourly BC output were compared to these observations. The Russian measurements of aerosol eBC concentrations were determined continuously using an Aethalometer purposely designed by MSU/CAO (Popovicheva et al., 2017). Light attenuation caused by the particles depositing on a quartz fiber filter was measured, and the light attenuation coefficient of the collected aerosol was calculated. eBC concentrations were determined continuously by converting the time-resolved light attenuation to the eBC mass corresponding to the same attenuation and characterized by a specific mean mass attenuation coefficient, in calibration with AE33 (Magee Scientific).

The Japanese measurements provide rBC (refractory BC). Pileci et al. (2021) showed that rBC and eBC are linearly related; thus, in order to compare the observations to models, we converted rBC to eBC via a factor of 1.8 (eBC = 1.8 × rBC; Zanatta et al., 2018; Pileci et al., 2021).

In this section, we evaluate modeled SLCFs from the 18 participating models with a focus on performance in the Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes (defined for our purposes as 30–60∘ N) and the Arctic (defined here as > 60∘ N for simplicity). Unless otherwise noted, the observations are compared to the model grid box that they are located in, and when more than one observation location occurs in the same model grid box, those observations are averaged first before the comparison. We look at spatial patterns in the model biases, as well as the vertical distribution and the seasonal cycles for each species, but first we start by providing a multi-species summary of the annual mean model biases in the surface air.

4.1 Multi-species summary

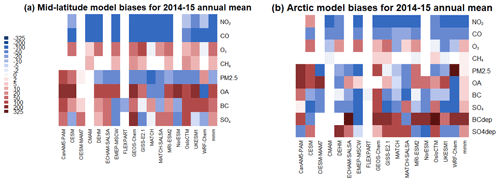

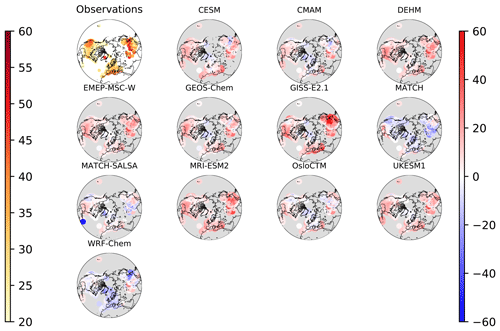

The 2014–2015 average modeled percent biases for surface concentrations of SLCFs are shown in Fig. 3 for each model and the multi-model mean (mmm). This figure is based on the model comparisons at the surface observation locations that will be shown in subsequent sections (Figs. 1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 18, 21, and 23 and additional American observations from the IMPROVE network for BC, SO, and OA).

Figure 3Mean 2014–2015 model percent biases for each model and the mmm for surface SLCF concentrations as well as BC and SO deposition at (a) midlatitudes and (b) the Arctic. Note that the color scale is not linear.

Figure 3b shows that, for surface Arctic concentrations, no one model performs best for all species but that the mmm performs particularly well. It also shows that the model biases vary quite a bit among SLCF species for both the midlatitudes and the Arctic. It is important to note that there are many more measurement locations at midlatitudes compared to in the Arctic. BC, CH4, O3, and PM2.5 have the smallest model biases out of the SLCFs of this study, whereas OA, CO, and NO2 have larger model biases.

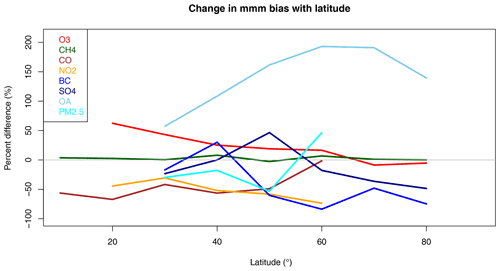

We find for half of the SLCF species that the mmm percent bias decreases with latitude (Fig. 4). O3, NO2, BC, and SO4 have a negative slope in the bias vs. latitude figure. So if the mmm bias was high at the midlatitudes, it is close to zero in the Arctic (O3), and if the mmm bias was near zero at midlatitudes, it is negative in the Arctic (NO2, BC, SO). This implies that there is not enough long-range transport from the midlatitude source regions to the Arctic. That said, the mmm CH4 bias stays relatively constant with latitude, and we will see in Sect. 4.2 that this result is model-dependent. The CO, PM2.5, and OA mmm biases have an increasing trend with latitude. However, both CO and PM2.5 have no observation locations in the high Arctic, so those results cannot represent long-range transport. OA only has one observation location in the high Arctic, and its bias is very large overall, so issues other than long-range transport are at play, as we will see in the following discussion (Sect. 4.7).

Figure 4Multi-model mean percent biases for surface SLCF concentrations versus latitude (in 10∘ latitude bins).

Of course, there are spatial, temporal, and model differences in the results, so we will now explore model performance for each SLCF in more detail in the next subsections.

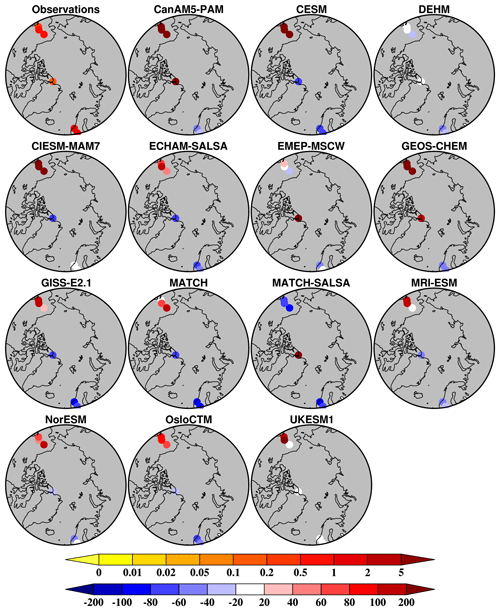

4.2 Methane

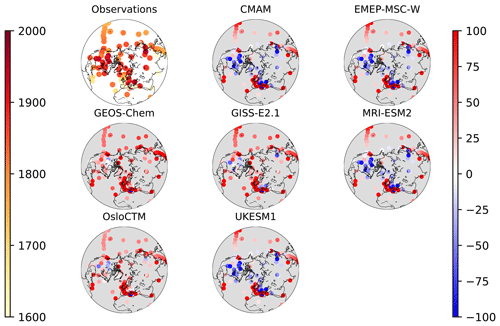

Measured annual mean surface methane is shown in the top left panel of Fig. 5, along with model biases in the rest of the panels. Recall that unlike the rest of the SLCF species in this study, CH4 concentrations were prescribed in these models from the same CH4 dataset (Olivié et al., 2021). That said, the different decisions by modelers on how those CH4 global concentrations are distributed make differences in how these models compare to measurements. The mean model biases are small and mainly positive; in the midlatitudes, the multi-model mean bias is +145 ppbv (or +8.5 %), and in the Arctic, the mmm bias is 24 ppbv (or 1.3 %), which means that the models simulate the magnitude of surface CH4 well – though still outside the < 1 % measurement uncertainty range. There is a gradient in CH4 VMRs (higher in the Northern Hemisphere and lower in the Southern Hemisphere) that is seen in the measurements (Fig. 5, top left) and reported in the literature (e.g., Dlugokencky et al., 1994), though it is not well captured by CMAM, MRI-ESM2, and UKESM1 models, which are all biased low in the Northern Hemisphere and biased higher towards the south. That is because of the simplifications made in these models' distributions of CH4. For example, CMAM used a single global average CH4 concentration that is interpolated linearly in time from once-yearly values.

Figure 5Measured surface-level methane (top left) (ppbv, left color bar) and (remaining panels) model biases (model minus measurement, also ppbv, right color bar) for 2014–2015.

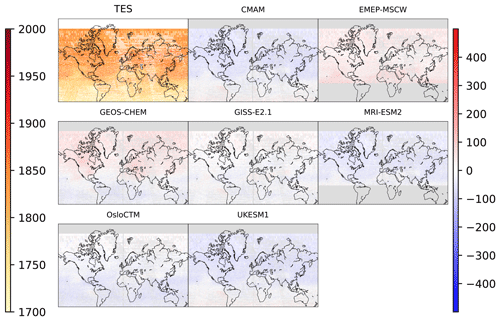

Figure 5 also shows that observed annual mean surface CH4 ranges geographically from about 1500 to 2100 ppbv depending on location; however, the models have a much smaller range due to their prescribing CH4 concentrations as a lower boundary input. For example CMAM CH4 volume mixing ratios only span about ±3 ppbv around 1836 ppbv. The span of MRI-ESM2 surface CH4 is even smaller. GEOS-Chem, GISS-E2.1, and OsloCTM have a more realistic range of 1700–2000 ppbv, though they still do not get the full variability that is seen in surface CH4 mixing ratios close to CH4 sources. However, in the free troposphere (above the boundary layer), we have TES satellite measurements of CH4 that show that CH4 is much more smoothly distributed aloft. Thus, the simplification of prescribing CH4 concentrations in the models is more realistic there (Fig. 6, showing the 600 hPa level in the mid-troposphere). Additionally, Fig. 6 better illustrates the latitudinal gradient in CH4 over the globe and its lack in some models, which have more negative biases in the Northern Hemisphere and more positive biases in the Southern Hemisphere. Other models, such as GISS-E2.1, do a good job of capturing the global distribution of CH4.

Figure 6TES measurements (top left) of CH4 in the mid-troposphere (at 600 hPa, ppbv, left color bar) and (remaining panels) model biases for 2008–2009 (model minus measurement, also ppbv, right color bar). Results for 2014–2015 are similar but had less spatial coverage by the satellite. Gray areas have no data (either from the model, TES, or both).

In the Arctic, the vertical cross section of CH4 VMRs over time as measured by the ACE-FTS in the middle to upper troposphere and in the stratosphere is shown in Fig. S1. There is a large decrease in CH4 above the tropopause at around 300–100 hPa. The models are all biased low around 300 hPa and high around 100 hPa. This pattern is true for midlatitudes as well as in the Arctic and may imply that the altitude of the modeled tropopause is too low. This same conclusion was also found in Whaley et al. (2022a) via comparisons of these models' simulations to ozonesonde measurements and in our satellite O3 comparison in the next section. The CH4 model–measurement correlation coefficients for ACE-FTS are relatively high (e.g., R=0.48 to 0.86 depending on the model).

Therefore, the general model evaluation for CH4 indicates that because models do not explicitly model CH4 emissions, they do not simulate the surface-level variability of CH4 VMRs. Models differ in their global distribution of CH4; thus, only some contain the north–south CH4 gradient. Those that do not have the largest underestimations of Arctic tropospheric CH4. The CH4 evaluation also implies that the modeled tropopause height may be too low.

4.3 Ozone

Tropospheric O3 is the third most important greenhouse gas (IPCC, 2021), and it is a regional pollutant that causes damage to human health and ecosystems. O3 is a secondary pollutant formed in the troposphere via photochemical oxidation of volatile organic compounds in the presence of nitrogen oxides (NOx= NO + NO2). As such, models must simultaneously simulate the meteorological conditions, precursor species distributions, and photochemistry correctly in order to accurately simulate O3. That said, since surface O3 is an important contributor to poor air quality, there is significant pressure for models to simulate it accurately, particularly in the heavily populated midlatitudes (e.g., for air quality forecasting). Only models with prognostic O3 are included in this section.

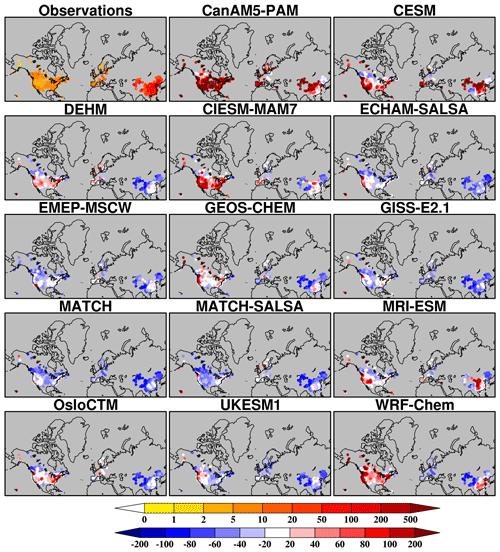

Figure 7 shows the in situ summertime mean O3 measurements (top left panel), and the model biases (remaining panels) and the same for the annual mean is shown in the Supplement (Fig. S2). These include averaging O3 from hourly observations (day and night) and 3-hourly or monthly modeled O3 depending on which were available for each model. Surface O3 is overpredicted by most models, which has been documented previously (Makar et al., 2017; Turnock et al., 2020). It has been shown that models can have problems producing low O3 overnight (Brown et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2008). In the Arctic, simulated surface O3 has more mixed results. Annual mean concentrations are of the order of 40 ppbv, and individual model biases range from −20 % to +52 % globally on average for 2014–2015. The multi-model mean has a bias of +11 % for the Arctic, but this is not uniformly spatially distributed. All models overestimated surface O3 in Alaska (mainly due to the overestimation of summertime concentrations, discussed below), and most models have too little O3 at the Greenland location and in northern Europe.

Figure 7Summertime (JJA) (top left) mean in situ surface O3 measurements (ppbv, left color bar) and (remaining panels) model biases for 2014–2015 (model minus measurement, also ppbv, right color bar). Results for 2008–2009 are similar but are not available for China.

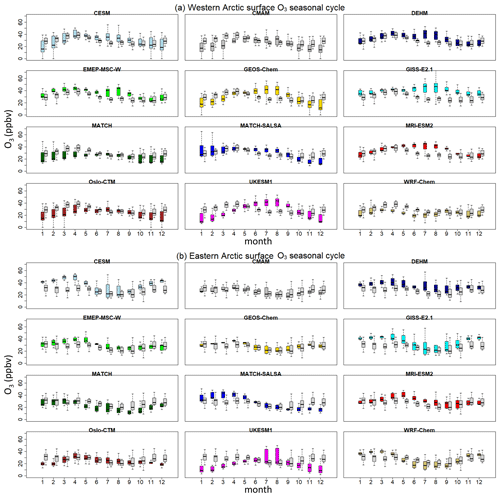

The models were all able to represent the summertime peak in the midlatitude seasonal cycle (not shown). In contrast to the more polluted midlatitudes, where surface O3 peaks in the summertime due to photochemical production being at a maximum, Arctic O3 is more influenced by the Brewer–Dobson circulation, bringing a maximum of tropospheric O3 in the springtime due to photochemical production (Wespes et al., 2012), descent from the stratosphere, and more long-range transport of O3 to the Arctic. Figure 8, shows this springtime peak in both the western (a, longitude < 0∘) and eastern (b, longitude > 0∘) Arctic in the measurements. However, the models only capture that seasonal cycle in the eastern Arctic (Fig. 8b), implying that the models represent large-scale circulation and possibly stratosphere to troposphere exchange well. But it is interesting to note that the models that have sophisticated representation of stratosphere–troposphere exchange (such as CMAM, MRI-ESM2, UKESM1) do not particularly stand out as better performers in Fig. 8 compared to models that do not simulate the stratosphere (such as DEHM, MATCH, MATCH-SALSA). Thus, its impact on surface O3 may be very small.

Figure 8Surface O3 monthly range that occurs at the locations in Fig. 7 above 60∘ N. The measurements are the black and white boxes and whiskers, and the models are the colored box and whiskers. (a) The western Arctic and (b) the eastern Arctic for 2014–2015. Thick horizontal lines indicate the median O3 VMR in each month, and the box extends to the interquartile range. The whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum monthly mean O3 VMR.

In the western Arctic (Alaska mainly, Fig. 8a), models overestimate summertime Arctic O3, likely due to overpredicting the impact of wildfire emissions on tropospheric O3 concentrations, which is a research topic with high uncertainty (van der Werf et al., 2010; Monks et al., 2015; Arnold et al., 2015). Another possibility is that modeled O3 dry deposition over boreal vegetation is underestimated (Stjernberg et al., 2012; Thorp et al., 2021).

Some Arctic locations are more inclined to get springtime surface O3 depletion due to bromine explosions and halogen chemistry (Bottenheim et al., 1986; Barrie et al., 1988; Simpson et al., 2007). None of the model simulations in this study contain the necessary tropospheric halogen chemistry to simulate those events, which partly explains why some models in Fig. 8 (bottom) overestimate springtime O3 concentrations. That particular feature is explored further on a site-to-site basis in Whaley et al. (2022a).

The next subsection shows that both the O3 precursors CO and NO2 are underestimated compared to measurements at all global locations. This has implications for simulated tropospheric O3 chemistry.

Free-tropospheric O3 – satellite comparisons. Aircraft-based measurements and ozonesondes can provide insight into the vertical distribution of O3, and these have been well documented (e.g., Tarasick et al., 2019; Whaley et al., 2022a). However, model grid boxes may not be representative of those fine-spatial-scale measurements. In this study, we examine how the model biases change in the vertical when compared to satellite measurements, which have a larger, “smoothed out” spatial sensitivity due to their viewing geometry and retrieval methods. Specifically, we compare modeled O3 to TES and ACE-FTS satellite-based retrievals. These satellite instruments also have better global coverage than aircraft and sonde-based measurements.

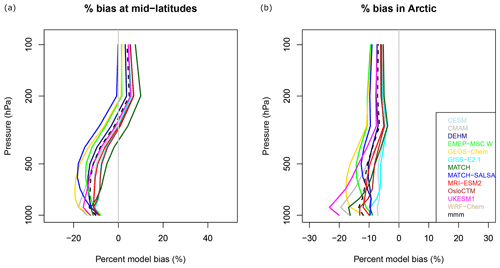

The model fractional biases compared to TES measurements from near the surface up to 100 hPa are shown in Fig. 9 for the Arctic (left) and midlatitudes (right). All models' simulated fractional biases have similar vertical profiles for both the Arctic and midlatitudes, with greater negative values at lower levels and a more positive “bulge” of about 10 % around 300 hPa in the Arctic and about 5 % around 200 hPa at midlatitudes. That bulge in model biases at 300 hPa was also seen to a greater degree (50 %–70 %) when comparing these model simulations to Arctic ozonesonde measurements in Whaley et al. (2022a). Compared to TES, which has much lower vertical resolution, the results are not as striking but are consistent with ACE-FTS measurements. On average, the models have a negative bias at all vertical levels in the Arctic region and in lower troposphere in the midlatitude region, whereas a positive bias is seen in the upper troposphere below 60∘ N. This is consistent for the two time periods (2008–2009 and 2014–2015).

Figure 9Vertical distribution of models' O3 percent biases (model minus measurement over measurement) for 2008–2009 compared to the TES measurements; (a) average for midlatitudes (30–60∘ N) and (b) average for Arctic latitudes (> 60∘ N).

Given that Fig. 7 shows positive biases near the midlatitudes, while Fig. 9 shows lower O3 in the free troposphere, these results imply that there is not enough vertical lifting and/or mixing of tropospheric O3 in most of the models. However, the TES measurements have been shown to be biased high by approximately 13 % throughout the troposphere (Verstraeten et al., 2013), which is the same amount that the mmm is low. Similarly, ACE-FTS O3 has an uncertainty range of +5 %–10 % when compared to O3 from other satellite limb-view observations (Sheese et al., 2017). The ACE-FTS comparison for O3 can be found in the Supplement (Fig. S3), showing higher model biases around 300–100 hPa (except for GEOS-Chem) and good agreement below that. Therefore, overall, participating models simulate the free-tropospheric O3 reasonably well and within the uncertainly limits of the observations.

Therefore, the general model evaluation for O3 indicates that all models overestimate surface O3 at midlatitudes, and that, combined with a lack of O3 transport to the Arctic, results in modeled Arctic O3 VMRs having relatively little bias (the right answer for the wrong reason). The summertime evaluation implies that models overestimate the O3 produced and transported by wildfires in the western Arctic. The O3 evaluation also implies that the modeled tropopause height may be too low.

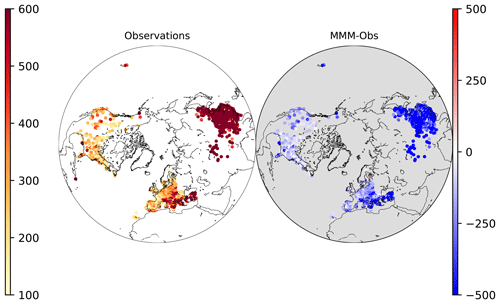

4.4 O3 precursors: carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides

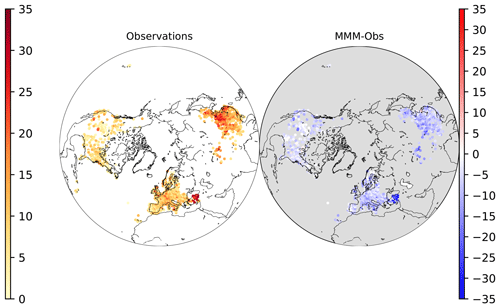

Figures 10 and 11 show the comparisons of the multi-model medians (MMMs) to the surface in situ measurements. The figures for each model appear in the Supplement (Figs. S4 and S5), but only the MMMs are shown here since the spatial patterns were very similar for all models. The multi-model annual mean underpredicts both CO and NO2 by approximately −55 % in the Northern Hemisphere for 2014–2015. The 2015 AMAP report showed similar findings for simulated surface CO, as have other studies (AMAP, 2015a; Emmons et al., 2015; Monks et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2015; Quennehen et al., 2016), pointing to a likely underestimation of CO emissions and possibly shorter modeled lifetimes of CO due to an overestimation in OH (Miyazaki et al., 2012). The annual mean surface CO underestimation is mainly dominated by the wintertime (e.g., the mmm bias in DJF is −92 %), when it has been reported that CO emissions from combustion are too low (e.g., Kasibhatla et al., 2002; Pétron et al., 2002). All the models exhibit a large negative bias over China, which is consistent with the study by Quennehen et al. (2016) and is attributed to the enhanced destruction of CO by OH radicals, but it was also found in Kasibhatla et al. (2002) and Pétron et al. (2002) that bottom-up CO emission inventories in Asia are greatly underestimated.

Figure 10Mean CO volume mixing ratios (ppbv, left color bar) at surface measurement sites and MMM bias (MMM minus measurement ppbv, right color bar) for 2014–2015. Results from 2008–2009 are similar and not shown.

Figure 11Mean NO2 volume mixing ratios (ppbv, left color bar) at surface measurement sites and MMM bias (MMM minus measurement in ppbv, right color bar) for 2014–2015. Results from 2008–2009 are similar and not shown.

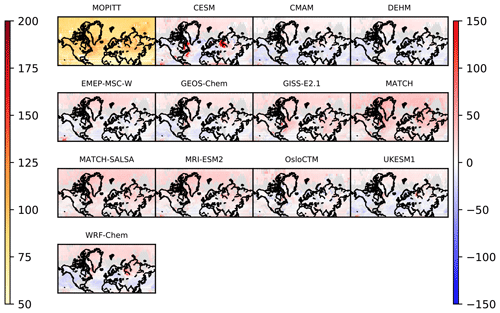

In the free troposphere, we compare modeled CO to that measured by MOPITT. Figure 12 shows these comparisons for the summertime (JJA) mean at the 600 hPa level, and Fig. S6 in the Supplement shows the same for the springtime (MAM) mean. Unlike in the winter and spring when all models are biased low at midlatitudes, there is more variability in the summertime biases, with about half the models overestimating free-tropospheric CO and the other half underestimating it. In the Arctic region, all models are biased high in the summer but low in the springtime. In the winter, MOPITT does not have coverage in the Arctic. Monks et al. (2015) discussed the fact that models had high biases in the tropospheric column of CO compared to MOPITT measurements in the outflow from Asia and low biases north of there due to lack of transport. The Quennehen et al. (2016) study also suggested that summertime CO transport out of Asia is too zonal when comparing models to IASI CO columns. At 600 hPa, where CO concentrations are lower and the atmosphere is more mixed, these features do not appear.

Figure 12Summertime (JJA) (top left) mean MOPITT CO at 600 hPa (ppbv, left color bar) and (remaining panels) model biases (model minus measurement ppbv, right color bar) for 2014–2015.

In the upper troposphere and stratosphere, modeled CO and NOx monthly time series are compared to measurements from the ACE-FTS satellite instrument (where NOx= NO + NO2, which are measured separately), and those results are shown as Taylor diagrams in Fig. S7, along with O3 and CH4 at 150 hPa, which is in the upper troposphere–lower stratosphere (UTLS) region. The contours show the model's overall skill as defined in Hegglin et al. (2010). Only the models that simulate the stratosphere were included, and the results show that there is a range in model performance by SLCF species, with no one model performing best for all. Comparison statistics for CO were poorer than those for O3, CH4, and NOx.

4.5 Black carbon

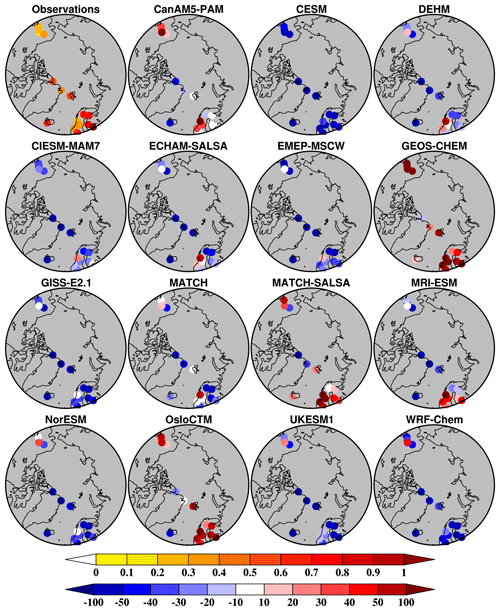

In this section, we examine the spatial and seasonal distributions of BC using ground-based measurements, which are primarily available in North America, Europe, and several locations in the Arctic, but are also available from two ship-based campaigns and several aircraft campaigns. Given the limited global data available for both BC and SO (e.g., we could find none freely available for Asia), we focus the plots on the Arctic region here, and given that the magnitude of BC and SO does not span a wide range throughout the Arctic, we show model biases as percent rather than absolute differences as was done in previous sections for trace gas species shown globally. We also analyze the BC model–measurement comparisons, keeping in mind that because there are various definitions and measurement types for BC, we consider agreement within a factor of 2 to be within the uncertainty range (Sect. 3.1.3).

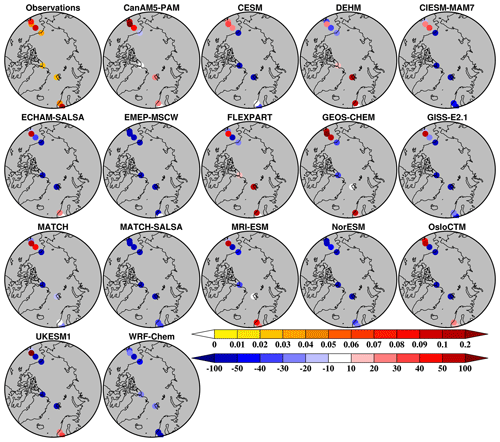

Figure 13 (top left panel) shows annual mean surface-level concentrations of black carbon (BC) at nine Arctic observation stations and (remaining panels) the model percent biases there. The annual mean BC concentrations are of the order of less than 1 µg m−3, and most models tend to underestimate BC in the high Arctic while overestimating in Alaska and Scandinavia. This result could be partially explained by the discrepancy caused by the use of EC and eBC data, which are not the same (Sect. 3.1.3). As aerosols age during transport to high-Arctic locations, their eBC (based on absorption converted to mass) gets more and more of a positive bias compared to EC. As models are more representative of EC, they will not be able to agree with eBC measurements in aged air at high-Arctic remote stations, such as Gruvebadet, Zeppelin, Alert, and Utqiaġvik. This is in contrast to the Alaskan and European stations, which are closer to sources where BC is more fresh; thus, the eBC measurements have lower uncertainty.

That said, a few models (CanAM5-PAM, DEHM, and FLEXPART) overestimate BC concentrations in the high Arctic. Overall individual model biases range ±100 % at individual sites.

Figure 13Mean BC concentrations (µg m−3, top color bar) at surface Arctic measurement sites and model bias (as (model–measurement) measurement in percent, bottom color bar) for 2014–2015. Results from 2008–2009 are similar and not shown.

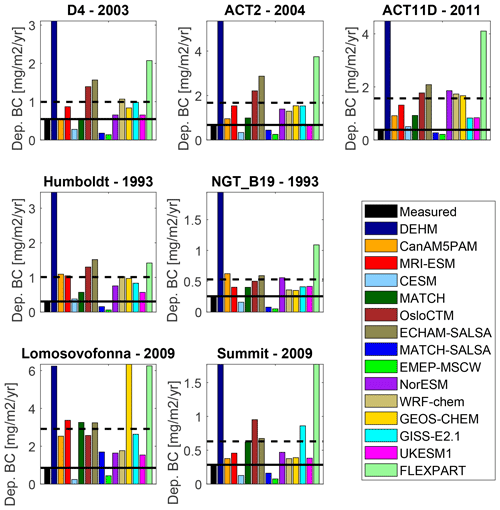

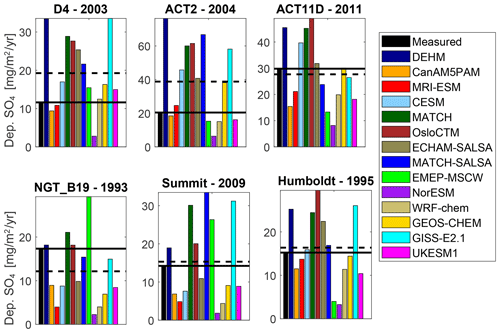

The underestimation of high-Arctic atmospheric BC concentrations may be related to excessive BC deposition further south; however, there are very few BC deposition measurements. In the Arctic, we can evaluate total (wet + dry) modeled deposition via derived ice core measurements. There were six ice cores on Greenland and one in the European Arctic in Spitsbergen (Lomosovfonna). Figure 14 shows that all models overestimate BC deposition fluxes at the ice core locations. While the ice cores contain BC data starting in the year 1750, only data after 1990 have been used to match the modeled time period (1990–2015, 1995–2015, 2008–2009, and 2014–2015, depending on the model).

Figure 14Annual average BC deposition flux values for the seven ice core locations (Fig. 1b) for each model based on values from 2008–2009 and 2014–2015. The observed fluxes are plotted in black, and a black line indicates the level of the average observed flux; the black dashed line is the model mean for each location. The period used for plotting is based on all available years after 1990; the title indicates the last available year form the ice core record.

The measured BC deposition flux values on Greenland vary with elevation (lower fluxes at higher elevation). Summit (3177 m a.s.l.) has an average of 285 µg m−2 yr−1 in contrast to ACT2 (2461 m a.s.l.) with 676 µg m−2 yr−1. BC deposition is highest in the European Arctic at Spitsbergen with 856 µg m−2 yr−1. For all seven ice cores used in this comparison the averaged model mean is 3 times as high as the observations. At D4 (2728 m a.s.l.) the modeled mean corresponds best to the observation, with a mean bias of +83 %. At ACT11 (2296 m a.s.l.) the models have 4 times the deposition flux compared to the measurements. Generally though, the model mean is skewed higher by FLEXPART and DEHM (Fig. 14), which also had higher atmospheric BC concentrations. A few models simulated less BC deposition than observed at these sites, and these models also underestimated BC atmospheric concentrations. Thus, it is difficult to conclude that deposition biases are a cause for atmospheric biases when the two are inter-related parameters.

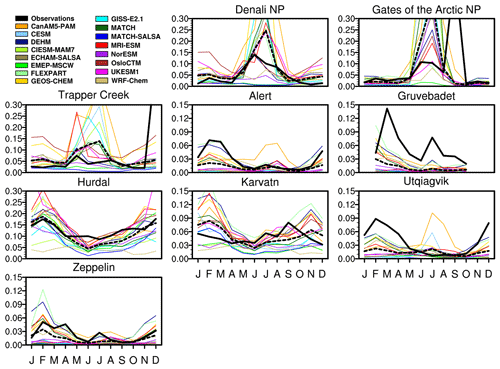

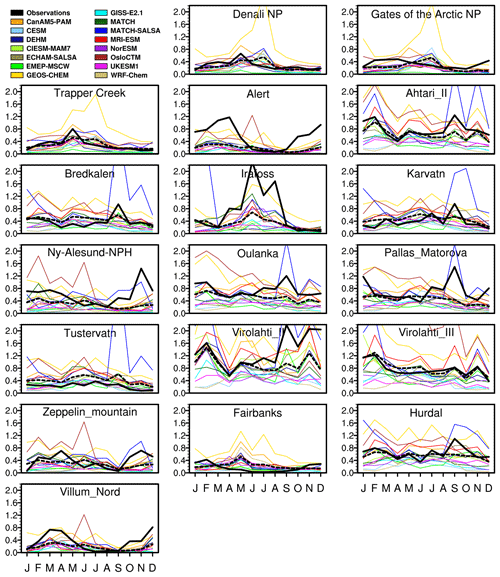

The seasonal cycles of surface-level atmospheric BC concentrations at several Arctic locations are shown in Fig. 15. As seen in Eckhardt et al. (2015), some models still underestimate wintertime BC, but many models now show similar seasonality as the observations. The multi-model mean also captures the monthly variations well including the summertime peak at some Alaskan sites caused by fire emissions. The multi-model mean Arctic BC is underestimated in winter (−24 %) and overestimated in the summer (+32 %), though overall, this is an improvement in model performance in simulating Arctic BC since the 2015 AMAP assessment of black carbon and ozone as climate forcers – the latter of which had −59 % winter bias and +88 % summertime bias (AMAP, 2015a; Eckhardt et al., 2015). However, it is difficult to make direct comparisons to that report as those values were for a smaller set of Arctic locations, different observation periods, and with a different set of models (though many overlapping). The model improvement may be due to the improved anthropogenic emissions of BC, particularly from northern Russia, where flaring emission factors were increased in ECLIPSEv6B compared to those used for the 2015 AMAP report.

Figure 15Modeled (thin colored lines) and measured (thick black line) monthly mean BC concentrations (in µg m−3) at surface Arctic measurement sites in 2014–2015. The multi-model mean is shown by the black dashed line.

Most models have reasonable spatial correlation with the measurements across the Arctic in that they correctly simulate the range of BC concentrations that appear across the Arctic (e.g., higher concentrations at Hurdal, lower concentrations at Zeppelin), as shown in Fig. S8. However, there are still large differences and low R values in the statistics shown in Fig. S8.

There are positive model biases at midlatitudes (in North America and Europe; not shown) for surface-level BC. The vertical analysis of BC from the aircraft campaigns (below) provides further insight and support for the suggestion that models do not have adequate long-range transport of the pollutants from their sources in the midlatitude; thus, they do not simulate enough pollution in the Arctic.

Vertical profiles of BC – aircraft campaigns. Gridded BC output at 3-hourly intervals was provided by 11 of the participating models and was compared to aircraft campaign measurements of BC. The interpolation of model output to flight track coordinates was carried out by tools from the Community Intercomparison Suite (CIS; Watson-Parris et al., 2016), which co-located the extracted model tracks with their corresponding observational values.

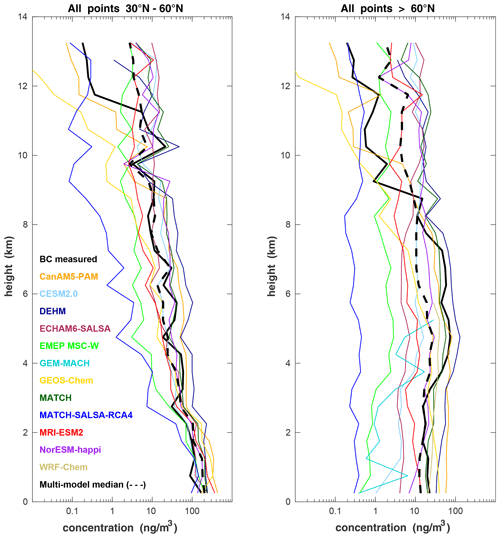

Figure 16 shows the median vertical profiles of BC concentrations from the aircraft measurements and from the models. At midlatitudes, from 0–2 km, all of the models agree well with the measurements. However, BC concentrations decline steeply in a few models (e.g., MATCH-SALSA, EMEP-MSC-W, and GEOS-Chem) above 2 km. It would appear that they do not have enough vertical lifting of BC and/or perhaps too short of a BC lifetime. Indeed, one of these is EMEP MSC-W, in which the short BC lifetime was previously reported in Gliß et al. (2021). That said, in Lund et al. (2018b), the Oslo-CTM and ECHAM models were shown to overestimate the BC lifetime. In our case, OsloCTM is not shown in Fig. 16 because it did no provide BC at 3-hourly timescales. But ECHAM-SALSA results are consistent with the Lund et al. (2018b) study in that they particularly overestimate BC in the upper altitudes in both the midlatitudes and the Arctic, implying too long a lifetime and too much long-range transport into the upper Arctic atmosphere. The measured BC profile at midlatitudes drops off more quickly around the tropopause at 11–12 km, and, except for CanAM5-PAM, the models do not reproduce this drop.

Figure 16Median vertical profiles of observed (heavy black line) and modeled (colored lines) BC concentrations for all aircraft campaigns combined, separated into (left) midlatitudes and (right) the Arctic. The multi-model median is shown by the dashed black line.

In the Arctic profiles (Fig. 16), the modeled and observed profiles do not decline with altitude throughout the troposphere, but the observed median BC concentration does drop sharply around 9 km – again near the Arctic tropopause, and again, the only model to capture that change is CanAM5-PAM. In the Arctic comparisons, the models that did not simulate enough BC aloft at the midlatitudes stand out as having larger underestimates of BC in the Arctic. For example, MATCH-SALSA and EMEP MSC-W have very low BC throughout the Arctic vertical profile. These results are consistent with the surface BC underestimation in Fig. 15. Therefore, the underestimation seen in the Arctic for those two models is likely due to a lack of long-range transport from the midlatitudes, as well as errors in BC deposition mentioned above. In addition, the Zhao et al. (2021) study showed that different parts of the Arctic BC vertical profile are sensitive to BC transported from different areas of the world. For example, the lower-tropospheric BC is influenced by emissions transported from North America, Russia–Belarus–Ukraine, Europe, and East Asia, whereas upper-tropospheric Arctic BC is mainly influenced by transport from South Asia. Thus, the differences in the model results could be related to differences in how they simulate these transport pathways.

Mahmood et al. (2016) found that, overall, considerable differences in wet deposition efficiencies in the models exist and are a leading cause of differences in simulated BC burdens. Results from their model sensitivity experiments indicated that convective scavenging outside the Arctic reduces the mean altitude of BC residing in the Arctic, making it more susceptible to scavenging by stratiform (layer) clouds in the Arctic. Consequently, scavenging of BC in convective clouds outside the Arctic acts to substantially increase the overall efficiency of BC wet deposition in the Arctic, which leads to low BC burdens compared to simulations without convective BC scavenging. Oshima et al. (2013) also found that convective scavenging at middle and subtropical latitudes removes a significant fraction of BC. In contrast, BC concentrations in the upper troposphere are only weakly influenced by wet deposition in stratiform clouds, whereas lower-tropospheric concentrations are highly sensitive (Mahmood et al., 2016) – these are consistent with the results we find in this study, wherein the multi-model median is too high above about 9 km and too low from 0–9 km. Indeed, the MATCH and MATCH-SALSA models, for example, assume reduced scavenging of aerosol in mixed-phase clouds following Liu et al. (2011), which increases long-range transport to the Arctic. It is odd then that MATCH is one of the better=performing models in Fig. 16 and MATCH-SALSA is not. Despite the large range in modeled vertical BC concentrations, the multi-model median is close to the observed throughout the troposphere at both midlatitudes and in the Arctic.

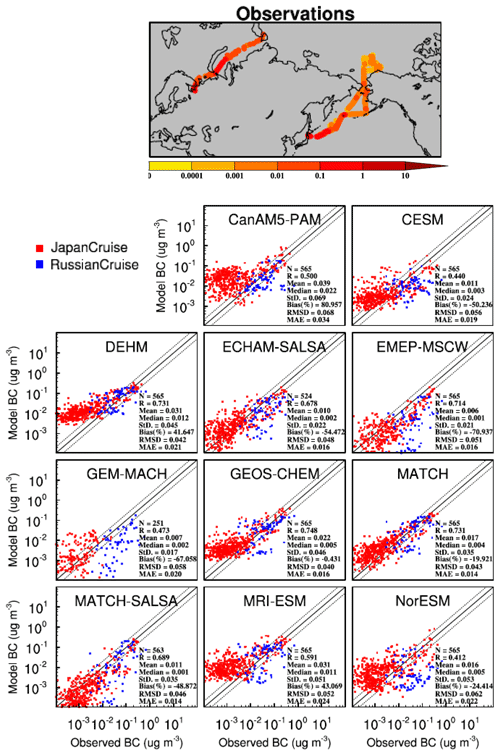

Arctic seas analysis – ship campaigns. From the ship-based measurements, we see that there is a consistent model overestimate of BC in the Pacific region (Japan cruise) where measured concentrations are very low (Fig. 17). Indeed, Taketani et al. (2016) report that BC concentrations were in the range 0–66 ng m−3, with an overall mean value of just 1.0 ± 1.2 ng m−3. The models, possibly due to their coarse resolutions, were not able to simulate such low background BC concentrations. However, even the model with the highest resolution (GEM-MACH at 15 km resolution) overestimated BC in the Pacific – though that limited-area model in that region near the boundary would have been heavily influenced by the upwind, coarser-resolution boundary conditions that were assumed (1∘ × 1∘ MOZART4 chemical boundary conditions). The high bias in the Pacific may be due to all models overestimating the amount of BC that gets transported off the Asian continent. That model bias is consistent with our low-altitude comparisons of the models to the HIPPO aircraft campaign measurements, which were taken over the northwestern Pacific (Fig. 2). The BC overestimate over the Pacific was also found in the Schwarz et al. (2013) study looking at simulated BC from the AeroCom global model intercomparison initiative compared to HIPPO measurements.

Conversely, the modeled BC concentrations generally agree with measurements in the Russian Arctic Ocean, though they are biased slightly low for the most part. Popovicheva et al. (2017) attribute the higher BC concentrations measured near the Kara Straight (north of 70∘ N) to gas-flaring emissions, and near Arkhangelsk (White Sea), important sources were midlatitude biomass burning, transportation, and combustion (residential and commercial). Since models were able to simulate this well, their improvement is likely due to improved Russian anthropogenic emissions in ECLIPSE v6B (Sect. 2.1, AMAP, 2022) compared to previous emissions datasets, which did not include enough Russian flaring emissions. The best model results were from ECHAM-SALSA and MATCH when compared to all of the ship campaign data.

Figure 17Observed BC concentrations (top) (µg m−3, top color bar) along the ship paths and (remaining panels) the modeled vs. measured 3 h average BC concentrations along the ship paths. Note the logarithmic scale.

Therefore, the general model evaluation for BC indicates that while there is a large variability in models results, they tend to overestimate surface BC at midlatitudes (including over the Pacific Ocean) and underestimate surface BC in the Arctic. Again, these results point to a lack of transport to the Arctic and, in this case, too much BC deposition along the way. While we were only able to evaluate BC deposition in the Arctic in this study, those results support the hypothesis of some models having too much BC deposition. The BC vertical profile evaluation also implies that the modeled tropopause height may be too low.

4.6 Sulfate

We used monthly mean surface level observations of SO from 18 Arctic sites to evaluate the models. Figure 18 shows that, similar to BC, the SO concentrations in the high Arctic are underestimated by most of the models. A few models overestimate SO in Scandinavia and Alaska.

Figure 18Mean measured SO concentrations (µg m−3, top color bar) at surface Arctic measurement sites and model bias (as model–measurement measurement in percent, bottom color bar) for 2014–2015. Results from 2008–2009 are similar and not shown.

The model underestimations of SO could be mainly due to higher efficiencies of models in removing aerosol during the long-range transport to the high Arctic. This is consistent with a previous study based on AMAP 2015 model simulations that found that the convective wet deposition outside the Arctic region may have led to different seasonal cycles of aerosol concentrations in the Arctic (Mahmood et al., 2016). Dimethylsulfide (DMS), a naturally occurring source of sulfur from marine algae emissions, could also be misrepresented in models. However, this source would be more pronounced in the summer when there is less sea ice in the high Arctic, and it does not appear as though models are underestimating only in the summertime (Fig. 19). Rather, some models appear too low in the winter and spring – which points towards underestimating local Arctic sources and to a lack of transport from midlatitudes as being the key issues. Despite the individual model differences in representing the seasonal cycle, the multi-model mean compares well with observations at most locations. However, the multi-model mean SO is significantly underestimated at Alert and Irafoss sites. Mean model biases for all Arctic sites range from −65 % to +80 % among different models, and correlation coefficients are typically around 0.5 (Fig. S9).

Figure 19Modeled (thin colored lines) and measured (thick black line) monthly mean SO concentrations (µg m−3) at surface Arctic measurement sites in 2014–2015. The multi-model mean is shown by the black dashed line.

The high GEOS-Chem bias in the summertime seen in Fig. 19 was first reported in Breider et al. (2014) and found to be due to problems with cloud pH and cloud liquid water in the summer over the Arctic. In Breider et al. (2017), the summertime Arctic surface SO concentrations are reduced by a factor of 2 by reducing the cloud liquid water content to a uniform value of 1 × 10−7 g m−3 north of 65∘ N in the model. The version of GEOS-Chem in our study is more recent and uses the offline cloud liquid water content from both GEOS-FP and MERRA2. We did not scale this variable down, which may be a reason for the high GEOS-Chem sulfate bias in Fig. 19.

The seasonal cycle for observations grouped together is shown in Fig. S10, showing a consistent seasonal cycle for 2008–2009 as seen in the observations. Most models (e.g., CanAM5-PAM, DEHM, MATCH, OsloCTM) are able to capture the seasonal cycle well. However, several models (e.g., CESM, CIESM-MAM7, ECHAM-SALSA, and EMEP-MSCW) strongly underestimate observed springtime peak values. Conversely, the models and the measurements showed a weaker seasonal cycle during the 2014–2015 time period (Fig. S11). It may be partly due to the local pollution sources in the Arctic during wintertime (e.g., Fairbanks). Those highly localized pollution events, caused by local emissions getting trapped in a stable boundary layer, occur on scales that are smaller than the model resolutions employed here can represent. Many models are also missing chemical formation processes for SO in the absence of sunlight, which may explain underestimations seen in winter (e.g., Moch et al., 2018; Alexander et al., 2009). An evaluation of SO2 could help with our understanding but was beyond the scope of this study. A lack of dark chemistry may be true for organic aerosol, as discussed in the next section as well.

From October to December 2014, the Honoluraun volcanic eruption may have elevated SO concentrations at some locations in the Arctic. However, in our model–measurement comparisons, there does not appear to be a large underestimate during those months, which implies that model performance was not impeded by not including those volcanic emissions.

As mentioned above, the uncertainty in wet deposition could be a significant factor in atmospheric SO model biases. Previous studies have shown that models have too much washout in winter and not enough wet deposition in summer, leading to a “flatter” seasonal cycle than observed (e.g., Fig. 19; Browse et al., 2012; Mahmood et al., 2016). As with BC in the previous section, the SO deposition was evaluated here in the same manner. The average measured SO deposition fluxes from ice cores for all locations (only Greenland was available here) are 18 mg m−2 yr−1. The lowest observed fluxes are found at D4 (12 mg m−2 yr−1) and the highest at ACT11D (30 mg m−2 yr−1). The model average for all locations is overestimated by around 20 % compared to measured fluxes. This is similar to the model biases in atmospheric SO concentrations.

Figure 20SO deposition fluxes for the Greenland ice core locations shown in Fig. 1b. The observed fluxes are plotted in black, and a black line indicates the level of the average observed flux; the black dashed line is the multi-model mean at that location. The period used for plotting is based on all available years after 1990; the title indicates the last available year from the ice core record.

Therefore, the general model evaluation for SO indicates that while there is a large variability in models results, as with BC, models underestimate surface SO in the Arctic. The evaluation of SO deposition in the Arctic is similar to BC, with both overestimating deposition.

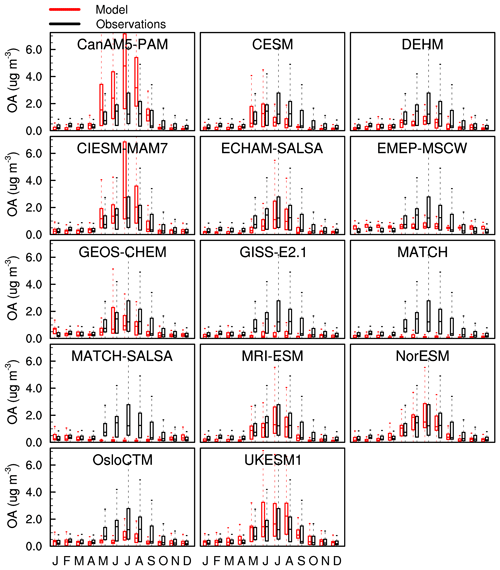

4.7 Organic aerosol

Unfortunately, there is only one high-Arctic station with OA measurements (Alert, NV, Canada); however, there are a few additional stations measuring OA in the sub-Arctic (still > 60∘ N). These are all shown in Fig. 21. The seasonal cycles are shown in Fig. 22, and the model vs. measurement scatter plot along with some comparison statistics are presented in Fig. S12.

Figure 21Mean OA concentrations (µg m−3, top color bar) at surface Arctic measurement sites and model bias (as model–measurement measurement in percent, bottom color bar) for 2014–2015. Results from 2008–2009 are similar and not shown.

Model biases have a large range of ±200 % at the different locations, but the multi-model mean for the region is +65 %. At midlatitudes (30–60∘ N), measurements are conducted mainly in the US, where the multi-model mean bias is +83 % for the 2014–2015 average (not shown).

Several models (CanAM5-PAM, DEHM, CIESM-MAM7, ECHAM-SALSA, GEOS-Chem, MRI-ESM2, NorESM, OsloCTM, and UKESM1) are able to simulate the summertime peak in Arctic OA concentrations; however, the other seven models in Fig. 22 simulate a seasonal cycle that is too flat or peaks at the wrong time (e.g., the CESM seasonal cycle peaks too early in the year).

Figures 21 and S11 both show that most models consistently overestimate Alaskan OA and underestimate European OA, consistent with our assessment of other species showing that models are likely overestimating wildfire influence in summertime Alaska. All models, except EMEP-MSC-W, used the GFED fire emissions inventory. EMEP-MSC-W used the FINN fire emissions inventory, which for BC+OC has been shown to be significantly lower than the GFED emissions (Liu et al., 2020). As a result, EMEP-MSC-W model biases in Alaska are lower. However, they are not the lowest. MATCH-SALSA has the lowest OA model biases in Alaska, despite that model using GFED emissions. The comparison statistics in Fig. S12 show highly varying results.

4.8 Fine particulate matter

PM2.5 is partly connected to direct and indirect climate effects via its interactions with clouds. It is mainly composed of BC, SO, OA, NO, and NH, as well as crustal material (dust), sea salt, and water, though the water component is often dried off during measurements. Model biases of those species will contribute to the total PM2.5 biases.

While BC, SO, and OA were discussed above, it is beyond the scope of this project to evaluate the other major PM species, which, aside from water, have a smaller radiative impact. Note that the analysis in this section is focused on sub-Arctic and midlatitude sites closer to human populations rather than remote high-Arctic sites due to a lack of data. PM2.5 is not a typical parameter included in the longer-term remote Arctic observations. Since PM2.5 has important health impacts, it is well measured at air quality monitoring networks.

Figure 23Measured ground-level PM2.5 concentrations (µg m−3) and model biases (as model–measurement measurement in percent, bottom color bar) for 2014–2015. The upper color bar represents observations, and the lower bar represents model biases.

The model PM2.5 biases at several locations in the United States, Europe, and China are within the 60 %–80 % range. However, some models (CanAM5-PAM, CIESM-MAM7, GEOS-CHEM, GEM-MACH, and Oslo-CTM) show biases larger than 200 %, especially in the western US and Alaska. The large inter-model differences in Fig. 23 are likely due to uncertainty in mineral dust. CanAM5-PAM has a particularly large contribution of dust to PM2.5. The Turnock et al. (2020) study showed that dust regions were globally one of the largest areas of diversity in PM2.5 concentrations between different CMIP6 models. The EMEP MSC-W results are consistent with EMEP annual evaluations for Europe, where the model underestimates PM2.5 by 10 %–25 %, including a few Arctic sites in Norway and Finland (Gauss et al., 2020, and annual model evaluation reports at https://www.emep.int/publ/common_publications.html, last access: 14 April 2022).

The simulated surface-level SLCFs were quite sensitive to the different meteorological conditions such as boundary layer stability and levels of photochemistry, which differed between the two time periods chosen in this study. 2014–2015 was also a time period with more wildfires compared to 2008–2009. For example, according to the CMIP6 emission data that were used in most of the models, emissions of BC from Canadian wildfires in 2014–2015 were 340 % higher than in 2008–2009, whereas the emissions from the USA and Russia were similar for these years. Given the very intense wildfire emissions and low anthropogenic emissions in northern Canada in 2014–2015, differences in simulated PM2.5 concentrations over Canada and Alaska can be partly attributed to differences in simulations of wildfire aerosols in the models.

Some models (CanAM5-PAM, CESM, CIESM-MAM7, GEOS-Chem, and WRF-Chem) simulate higher PM2.5 and more variable PM2.5 in the summertime (e.g., Fig. S13 in the Supplement). While this is seen to some extent in the observations, this may be due to the way fire emissions and sea salt emissions are treated in these models. Fire emissions, fire plume injection height, plume rise, and wet deposition of fire pollutants are all highly uncertain model processes and a subject of ongoing research (e.g., Urbanski, 2014; Heilman et al., 2014; Paugam et al., 2016). Indeed, the individual model PM2.5 Arctic biases are more tightly clustered for 2008–2009 when there were fewer fires. Mölders and Kramm (2018) showed that Arctic PM2.5 seasonal pollution is mainly due to local air pollution in the winter and due to fires in the summer.

Figure 24Annual mean PM2.5 comparisons between station observations and model simulations for the year 2015.

Figure 24 shows that the annual mean simulated PM2.5 concentrations compare well with observations and the correlation coefficients are relatively high (R=0.8 or higher for all models). The high concentrations in China and low concentrations in the US and Europe are captured by the models, providing confidence for health impact assessments that utilize these model results.

In this study, we evaluated the SLCF simulation capabilities of 18 models that were used in the 2022 AMAP SLCF assessment report. Our conclusions are grouped into the questions we aimed to answer in the Introduction.

5.1 How well do the AMAP SLCF models perform in the context of measurements and their associated uncertainty?

Recall that the in situ SLCF measurements had the following reported uncertainties: CH4 1 %, O3 3 %, CO 5 %, NO2 5 %–100 %, BC 200 %, SO 20 %, OA 20 %, and PM2.5 1 %–6 %. However, since the variability in measurements from different techniques was only really taken into account for the BC uncertainty, and since we are comparing annual mean results to each other, it is not a fair comparison to say that models and measurements agree with each other if model biases are within the reported measurement uncertainty range. However, we do use those numbers as a rough guideline for “good” model performance in the absence of other quantitative criteria.