the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Isotopic constraints on atmospheric sulfate formation pathways in the Mt. Everest region, southern Tibetan Plateau

Kun Wang

Shohei Hattori

Sakiko Ishino

Becky Alexander

Kazuki Kamezaki

Naohiro Yoshida

Shichang Kang

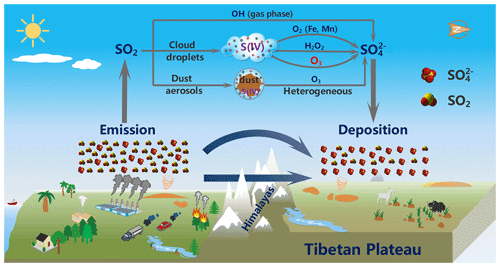

As an important atmosphere constituent, sulfate aerosols exert profound impacts on climate, the ecological environment, and human health. The Tibetan Plateau (TP), identified as the “Third Pole”, contains the largest land ice masses outside the poles and has attracted widespread attention for its environment and climatic change. However, the mechanisms of sulfate formation in this specific region still remain poorly characterized. An oxygen-17 anomaly (Δ17O) has been used as a probe to constrain the relative importance of different pathways leading to sulfate formation. Here, we report the Δ17O values in atmospheric sulfate collected at a remote site in the Mt. Everest region to decipher the possible formation mechanisms of sulfate in such a pristine environment. Throughout the sampling campaign (April–September 2018), the Δ17O in non-dust sulfate show an average of 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰, which is higher than most existing data on modern atmospheric sulfate. The seasonality of Δ17O in non-dust sulfate exhibits high values in the pre-monsoon and low values in the monsoon, opposite to the seasonality in Δ17O for both sulfate and nitrate (i.e., minima in the warm season and maxima in the cold season) observed from diverse geographic sites. This high Δ17O in non-dust sulfate found in this region clearly indicates the important role of the S(IV)+O3 pathway in atmospheric sulfate formation promoted by conditions of high cloud water pH. Overall, our study provides an observational constraint on atmospheric acidity in altering sulfate formation pathways, particularly in dust-rich environments, and such identification of key processes provides an important basis for a better understanding of the sulfur cycle in the TP.

- Article

(12022 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(562 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

As a predominant chemical component of atmospheric aerosols, sulfate () plays an important climatic role as it tend to make clouds more reflective and increases their lifetimes, thereby causing a net cooling effect on the planet (Charlson et al., 1992; Kulmala et al., 2000). Furthermore, it is also a major source of acidity in aerosols and cloud water and is implicated in acid deposition that exerts adverse effects on the ecological environment and human health (Chang et al., 1987). Sulfate is mainly produced within the atmosphere by the oxidation of sulfur dioxide (SO2), which is largely emitted from combustion processes (e.g., fossil fuel and biomass combustion) and volcanoes and is also generated by oxidation of other sulfur-containing species such as dimethyl sulfide (DMS) emitted by oceanic phytoplankton. The conversion of SO2 to sulfate is mainly dominated by gas- and aqueous-phase oxidation of SO2 by various oxidants (Liang and Jacobson, 1999; Mchenry and Dennis, 1994; Savarino et al., 2000; Lee and Thiemens, 2001; Stockwell and Calvert, 1983; Schwartz, 1987). In the gas phase, SO2 is mainly oxidized by hydroxyl radical (OH) to produce sulfuric acid (H2SO4) that can nucleate new particles and increase aerosol number density and the population of cloud condensation nuclei (Kulmala et al., 2000). Aqueous-phase sulfate formation involves dissolution of SO2 followed by dissociation of SO2•H2O to and . The total dissolved sulfur in solution, referred to as S(IV) due to their oxidation state of 4, is the sum of , which can be oxidized to sulfate via multiple pathways, mainly including oxidation by O3, H2O2, and O2 catalyzed by transition metal ions (TMIs, Fe3+ and Mn2+). Note that S(IV) can also be oxidized in the aqueous phase by other oxidants including NO2 (Lee and Schwartz, 1983), NO3 (Feingold et al., 2002), and HNO4 (Dentener et al., 2002), but these are not thought to be significant on the global scale. Hypohalous acids (HOCl and HOBr) were proposed to be potentially important oxidants only in the marine boundary layer (Vogt et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2016). Sulfate produced in the aqueous phase does not lead to nucleation of new particles but can increase particle growth rates since it forms on existing particles (Kaufman and Tanre, 1994). In addition, different aqueous pathways would be also responsible for different aerosol radiative forcing effects (Harris et al., 2013), and thus a detailed understanding of partitioning between the major oxidation pathways is critical for accurate estimation of the magnitude and spatial distribution of sulfate aerosol cooling in assessments of current and future climate. Despite the recent progress, the formation mechanisms of atmospheric sulfate still remain to be elucidated, especially for some specific regions with complex ambient conditions.

The Tibetan Plateau (hereafter referred to as TP), covering an area of km2 and having an average elevation of over 4000 m a.s.l., is the largest plateau in China and the highest plateau in the world. It contains the largest land ice masses outside the poles and supplies water for more than 1 billion people (Immerzeel et al., 2010). Due to its large area and high altitude, the TP plays an important role in the evolution of Asian monsoon system, and even the Earth's climatic system. Thus, the TP has been known as the “Third Pole” (Kang et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2012). As one of the most sensitive areas to global change (Liu and Chen, 2000) and adjacent to the world's most polluted areas, i.e., South and East Asia, the TP region has attracted widespread attention for its environmental and climatic impacts. Kang et al. (2019) summarized that the exogenous air pollutants can enter into the TP's environments via long-range transport, with regional impacts such as accelerating snow and glacier melting and degrading water quality. As one of those pollutants, atmospheric sulfate can affect not only aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems but also radiative forcing in the TP region. It has been demonstrated that sulfate plays an important role in both enhancing single scattering albedo and altering the absorption properties of carbonaceous aerosols (e.g., black carbon (BC) and brown carbon) (Lim et al., 2018). As a product of incomplete combustion of fossil fuel and biomass, BC deposited in the TP region has attracted much attention, since it can accelerate snow and glacier melting, although the magnitude of this effect is uncertain (Kang et al., 2020, and references therein). One recent study also revealed that the human-induced increase in atmospheric sulfate concentrations might be responsible for the persistent weakening of temperature seasonality over the TP since the 1870s (Duan et al., 2017). Thus, atmospheric sulfate not only has an influence on radiative forcing of the climate, to some extent, it could also affect the snow and glacier melting indirectly and further impact the supplies of fresh water to larger numbers of people in Asia. Thus, it is meaningful to investigate the formation mechanisms of sulfate in the Tibetan Plateau region for an accurate assessment of regional climatic change as well as cryospheric extent variation in this region. The mass-independent oxygen-17 anomaly (Δ17O) is any deviation from the linear approximation of , a relationship that describes the mass-dependent process, and can be quantified as (Thiemens, 1999), wherein . Since it was discovered to be produced during the chemical formation of ozone (O3) for the first time in the 1980s (Thiemens and Heidenreich, 1983), the Δ17O has been studied extensively and proven to be a powerful tool in discerning the formation mechanisms of atmospheric sulfate (e.g., Ishino et al., 2017, 2021; Alexander et al., 2002, 2005, 2009, 2012; Li et al., 2013; Jenkins and Bao, 2006; He et al., 2018; McCabe et al., 2006; Lee and Thiemens, 2001; Dominguez et al., 2008; Walters et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2017, 2021; Hattori et al., 2021). Because the oxidants transfer a unique Δ17O signal to the sulfate produced (Savarino et al., 2000), Δ17O in sulfate ()) reflects the relative importance of various oxidation pathways involved in its formation. Once emitted, SO2 quickly exchanges its oxygen atoms with abundant water vapor (Δ17O=0 ‰) in the atmosphere (Lyons, 2001), and any source signature in the oxygen isotopes is erased (Holt et al., 1981). Thus, unlike δ18O values that integrate both the δ18O values of reactants (SO2 and oxidants) and oxygen isotopic kinetic and/or equilibrium fractionation effects during the oxidation processes, atmospheric transport and deposition, Δ17O is fairly insensitive to mass-dependent fractionations and solely depend on the oxidation pathway of SO2 to sulfate, which render Δ17O a powerful tool to investigate the formation processes of sulfate. Laboratory experiments demonstrated that the mass-independent sulfate in the troposphere mainly originates from oxygen atom transfer from O3 ( ‰ for bulk tropospheric O3; Ishino et al., 2017; Savarino et al., 2000; Vicars and Savarino, 2014) and H2O2 ( ‰; Savarino and Thiemens, 1999) during oxidation of SO2, while oxidation by OH (Δ17O=0 ‰) as well as TMI-catalyzed oxidation by O2 ( ‰) produces sulfate with Δ17O at or near 0 ‰ (Vicars and Savarino, 2014; Savarino et al., 2000; Lyons, 2001; Ishino et al., 2021). Based on the transfer of the Δ17O signature from the oxidant to the produced sulfate (Savarino et al., 2000), Δ17O values of sulfate formed via the main oxidation pathways are as follows:

S(IV) oxidation by other oxidants (e.g., NO2 and hypohalous acids) is expected to produce sulfate with Δ17O near 0 ‰ as described in He et al. (2018) and Chen et al. (2016). Besides, the primary sulfate, including natural (mineral dust and sea salt) and anthropogenic (e.g., fossil fuel combustion) sources, also possesses a Δ17O value of 0 ‰ (Dominguez et al., 2008; Lee and Thiemens, 2001). As a non-labile oxyanion, once produced, sulfate in the atmosphere does not undergo further oxygen isotope exchange with ambient species. Theoretically, values in the real atmosphere can be predicted using the estimated fractional contribution of each formation pathway and corresponding Δ17O values by atmospheric chemical transport models (e.g., McCabe et al., 2006; Sofen et al., 2011). By comparing in situ observations with modeling results, the missing processes involved in sulfate formation can be quantified. However, existing observations of values provide sparse spatial coverage, particularly in remote regions such as the TP.

Although the TP is one of the most climatically important regions in the world, until now there are almost no observational studies focusing on the mechanisms of sulfate formation in this region, partly due to the harsh environmental conditions. Considering the specific climate and environment in the Tibetan Plateau region, especially the Mt. Everest region, e.g., low temperature, high elevation, and frequently occurring dust storms, we investigate whether the Δ17O characteristics in sulfate are different from other regions. As a result, we can infer the formation mechanisms of atmospheric sulfate in this unique region. We also examine whether the sulfate level in this remote site is influenced by long-range cross-border transport. With these expectations, here, for the first time, we present relatively long term Δ17O observations in atmospheric sulfate as well as its concentrations in this region, which is also an important addition to the global sulfate isotope dataset. Using the APCC (Atmospheric Pollution and Cryospheric Changes) monitoring network (Kang et al., 2019), aerosol samples (total suspended particulates, TSPs) were collected from a remote site located on the northern slope of Mt. Everest (27.98∘ N, 86.92∘ E; 8844.43 m a.s.l.) from April to September 2018. Located at the boundary of the Indian Monsoon and the southern edge of the TP, the Mt. Everest region is a possible receptor of atmospheric pollutants transported directly from the Indian subcontinent to the TP. By characterizing the observed Δ17O data combined with model simulations (GEOS-Chem global three-dimensional atmospheric chemical transport model), we decipher the possible mechanisms of sulfate formation in the Mt. Everest region, with important implications for the sulfur cycle, atmospheric oxidation processes, and models of climatic change in the TP region.

2.1 Observation site and aerosol sampling

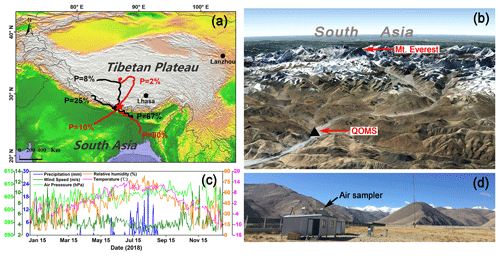

The field sampling was conducted at the Qomolangma Station for Atmospheric and Environmental Observation and Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences (QOMS; 28.36∘ N, 86.95∘ E; 4300 m a.s.l.) (Fig. 1). The sampling site has been previously described in detail (e.g., Ma et al., 2011). In brief, the QOMS is located in an S-shaped valley (Fig. 1b) where the surface is covered by sandy soil with sparse vegetation and gravel, and the surrounding region has limited human activity. Almost all precipitation (higher than 95 %) occurs during the monsoon season, and temperature and relative humidity (RH) also show clear seasonal patterns with higher values in the monsoon season than in the non-monsoon seasons (Fig. 1c). According to the measured meteorological parameters, mainly precipitation, the entire year of 2018 in the Mt. Everest region can be divided into four seasons, i.e., pre-monsoon (March to May), monsoon (June to August), post-monsoon (September to November), and winter (December to February).

Figure 1(a) A map showing the geographic location of the sampling site (QOMS, red star) with clustered 5 d backward trajectories of air masses arriving at QOMS during different seasons in 2018 (black lines stand for the pre-monsoon season and red lines stand for the monsoon season; the clusters were shown with respective percentage (P) of trajectories); (b) detailed terrain features around the QOMS and Mt. Everest (image from © Google Earth); (c) seasonal variations of meteorological parameters measured at the QOMS; and (d) a picture showing the sampling site and surroundings.

The TSP samples were collected by a high-volume air sampler (Laoying-2031, LAOYING Institute, China) mounted on the roof of an instrument room (Fig. 1d). Each sample was collected on pre-baked (450 ∘C for 4 h) quartz filters (Whatman Inc., UK) and covered for 4–7 d at a flow rate of 1.05 m3 min−1. After sampling, the filters were preserved properly (wrapped using aluminum foil, sealed in polyethylene bags and stored in a clean refrigerator at −20 ∘C), and eventually shipped to Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan, for further chemical and isotopic analyses. A filter was subjected to the same chemical analyses but without turning pump on when sampling for a blank test. A few samples with insufficient amounts of sulfate were combined with adjacent samples to obtain enough sulfates to run isotopic measurements.

2.2 Chemical and isotopic analyses

A detailed description of the method for chemical analysis of water-soluble inorganic ions can be found in K. Wang et al. (2020). Briefly, a small portion of each filter was soaked in 30 mL of deionized water in a 50 mL centrifuge tube under ultrasonic conditions for 20 min. Then the sample solution was separated from insoluble materials and the filter by a centrifugal filter unit centrifuged for 10 min. This method can recover more than 98 % of the initial water volume. The major anions (e.g., and ) were quantified by an ion chromatograph (Dionex ICS-2100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) while the cations (e.g., Ca2+ and K+) were detected by another ion chromatograph (881 Compact IC pro, Metrohm). The uncertainty of both instruments was approximately 4 % as determined by repeated measurements of standards. The reported concentrations of ions in this study are corrected by a measured field blank.

In this study, oxygen isotopic compositions were determined by an Ag2SO4 pyrolysis method as introduced by Savarino et al. (2001) with further modifications described in several later studies (Geng et al., 2013; Schauer et al., 2012). An aliquot of extracted solution (containing ∼1.5 µmol of sulfate) was dried in a freeze dryer (T=45 ∘C) to concentrate water-soluble ions. Dried salts were further heated at 450 ∘C for 2 h to remove organics following Xie et al. (2016). This heating procedure, which would not lead to measurable oxygen isotopic exchanges (Xie et al., 2016), is important in our study because organic contaminants may reduce the precision and accuracy of Δ17O measurements via consuming O2 produced during the Ag2SO4 pyrolysis state. Our preliminary tests showed that the yield of O2 produced from the Ag2SO4 pyrolysis was much lower (i.e., ∼50 %) than expected (higher than 90 %) when the Ag2SO4 was contaminated by organics (black/brown particles visible to the eye). After heating, the dried salts were re-dissolved by 10 mL of deionized water. Sulfate was subsequently separated from other anions via ion chromatography (Dionex Integrion, Thermo Fisher Scientific). About 1 µmol of sulfate in acidic form was then chemically converted into sodium salt (Na2SO4) using a cation-exchange resin. A total of 1 mL of H2O2 (30 %) was then added to the Na2SO4 samples to further remove any remaining organic materials and dried in a freeze dryer. The purified Na2SO4 was re-dissolved and subsequently converted into silver salt (Ag2SO4) by passing it through the cation-exchange resin that was in silver form. After being dried in freeze dryer, the Ag2SO4 powder contained in a custom-made quartz cup was thermally decomposed to O2 and SO2 at a temperature of 1000 ∘C in a continuous flow system. The gas products were carried by ultra-pure helium through a cleanup trap held at −196 ∘C to remove byproducts (mainly SO2 and trace SO3). The O2 was then quantitatively cryofocused by a liquid nitrogen trap with molecular sieve 5 Å. After thawing, the released O2 was further purified through gas chromatography, and finally the obtained O2 was carried into the isotope ratio mass spectrometer (MAT253, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for oxygen isotopic measurement. Since oxygen isotope (δ17O and δ18O) exchange between the O2 produced and quartz materials (Δ17O=0 ‰) occurring during the pyrolysis process shifts the Δ17O values (Savarino et al., 2001; Schauer et al., 2012), the raw Δ17O values were corrected by estimating the magnitude of the oxygen isotope exchange using inter-laboratory calibrated standards as described in Schauer et al. (2012). The correction method has also been applied by several of our previous studies (Gautier et al., 2019; Ishino et al., 2017, 2021; Hattori et al., 2021). Due to the unknown δ17O and δ18O values of each quartz material used in this study, it is difficult to get reliable corrected δ17O and δ18O values, thus we do not discuss these values in the following sections. The 1σ precision of corrected Δ17O was ±0.1 ‰ based on replicate analyses (n=20) of the standard B ( ‰) with five independent runs of this study.

2.3 Model description

GEOS-Chem is a global 3-D model of atmospheric composition (http://www.geos-chem.org, last access: 24 May 2021) originally developed by Bey et al. (2001). In this study, we use GEOS-Chem (version 12.5.0, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3403111) driven by assimilated meteorological fields from the MERRA-2 reanalysis data product from NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office's GEOS-5 Data Assimilation System. We simulate aerosol–oxidant tropospheric chemistry containing detailed HOx–NOx–VOC–ozone–BrOx chemistry (Bey et al., 2001; Pye et al., 2009; Sherwen et al., 2016). The model was run at horizontal resolution and 47 vertical levels up to 0.01 hPa and spun up for 1 year before each simulation. In the model, sulfate is produced from gas-phase oxidation of SO2 by OH; aqueous-phase oxidation of S(IV) by H2O2, O3, HOBr, and metal-catalyzed O2; and heterogeneous oxidation on sea-salt aerosols and dust aerosols by O3 (Alexander et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2017; Fairlie et al., 2010). To examine the importance of sulfate formation on dust aerosols, we tested the model simulation with or without sulfate formation on mineral dust (Fairlie et al., 2007; 2010).

The parameterization of the metal-catalyzed S(IV) oxidation is described in Alexander et al. (2009). We consider Fe and Mn which catalyze S(IV) oxidation in the oxidation states of Fe(III) and Mn(II). Dust-derived Fe ([Fe]dust) is scaled to the modeled dust concentration as 3.5 % of total dust mass, and dust-derived Mn is a factor of 50 times lower than [Fe]dust. Anthropogenic Fe ([Fe]anthro) is scaled as of primary sulfate, and anthropogenic Mn ([Mn]anthro) is 10 times lower than that of [Fe]anthro. In the model, 50 % of Mn is dissolved in cloud water as Mn(II) oxidation state, and 1 % of [Fe]dust and 10 % of [Fe]anthro are dissolved in cloud water as Fe(III) oxidation states.

For pH-dependent S(IV) partitioning, bulk cloud water pH is calculated as described in Alexander et al. (2012). We use the parameterization as described in Yuen et al. (1996) to account for the effect of heterogeneity of cloud water pH on S(IV) partitioning and subsequent aqueous-phase sulfate formation (Alexander et al., 2012). Sulfate formed from each oxidation pathway was treated as a different “tracer” in the model as described elsewhere (Chen et al., 2016; Sofen et al., 2011).

For anthropogenic emissions, we use the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) inventory (http://www.globalchange.umd.edu/ceds/, last access: 24 May 2021) (Hoesly et al., 2018). Emission species for CEDS include aerosols (BC, organic carbon (OC)), aerosol precursors, and reactive compounds (SO2, NOX, NH3, CO, non-methane volatile organic carbon (NMVOC)). We use the biomass burning emissions from the CMIP6 (BB4CMIP) inventory for each individual year (Van Marle et al., 2017). Emission species for BB4CMIP include the following species: BC, CH4, CO, NH3, NMVOC, NOX, OC, SO2, and HCl. We prescribe latitudinal CH4 concentrations for historical simulations. CH4 concentrations are based on NOAA GMD flask observations (https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends_ch4/, last access: 24 May 2021).

Model simulations were performed for the year 2013 (see Hattori et al., 2021). In addition to the model with calculated cloud water pH, we test the same model but assume cloud water pH is constant (pH=4.5), which is according to an earlier study (Sofen et al., 2011), with the purpose of examining the importance of changes in bulk cloud pH for modeled Δ17O. The values in the model were calculated by adding all sulfate isotope tracers with different Δ17O end-members as described in Eqs. (1)–(4). The modeled values of grid including sampling sites were mass-weighted averaged within the troposphere.

2.4 Complementary data

2.4.1 Meteorological and BC data

The meteorological information was recorded by a Vantage Pro2 weather station (Davis Instruments) located at the QOMS. Measured meteorological parameters include temperature, RH, wind speed and air pressure with a precision of 0.1 ∘C, 1 %, 0.1 m s−1, and 0.1 hPa, respectively. Precipitation data presented here were collected by manual measurements after each precipitation event. Since BC is mainly produced from incomplete combustion of fossil fuel and biomass, which are also important sources of SO2, in order to investigate the potential contribution of combustion source to sulfate, the BC data are also presented in this study. The BC concentrations at the sampling site were measured by a newly developed Aethalometer model AE-33 (Magee Scientific), which was operated at an airflow rate of 4 L min−1 with a 1 min time resolution. By incorporating a patented DualSpotTM measurement method, the instrument can provide accurate real-time BC measurements. The detailed information on the BC observations is described in Chen et al. (2018).

2.4.2 O3 mixing ratios

Since observations of O3 at the sampling site are unavailable, the surface O3 concentration in 2013 presented in this study are from an upwind region of our sampling site, i.e., NCO-P (Nepal Climate Observatory at Pyramid; 27.95∘ N, 86.80∘ E), which has been reported by Putero et al. (2018). This dataset was obtained from GAW/WDCRG (Global Atmosphere Watch programme/World Data Centre for Reactive Gases) and hosted by EBAS data infrastructure at NILU (the Norwegian Institute for Air Research). Located on the southern slope of Mt. Everest, NCO-P is not far from our sampling site (∼50 km), and the O3 measurements there have been continuously performed with a UV-photometric analyzer (Thermo Scientific-Tei 49C) since 2006 (Cristofanelli et al., 2010). In addition to O3 concentration at NCO-P, the O3 reanalysis data (at the level of 500 hPa) in 2018 for our sampling region (i.e., QOMS) was obtained from the ERA-Interim reanalysis (Dee et al., 2011) to further clarify the seasonality of O3 over the southern TP.

2.4.3 Solar radiation and RH along with backward trajectories

Apart from the meteorological data directly observed at the sampling site, the solar radiation fluxes and RH along with backward trajectories arriving at the sampling sites during the sampling campaigns were also calculated by NOAA's HYSPLIT (Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) atmospheric transport and dispersion model, and averaged for each day (https://ready.arl.noaa.gov/HYSPLIT_traj.php, last access: 24 May 2021) (Stein et al., 2015). The model calculation was forced by archived GDAS (Global Data Assimilation System) meteorological data obtained from NOAA Air Resource Laboratory with latitude and longitude horizontal resolution. The calculated backward trajectories were clustered using TrajStat, an air mass trajectory statistical analysis tool contributed by Wang et al. (2009). Since the lifetime of sulfate aerosols is on the order of 4–5 d (Alexander et al., 2012), the total run time of 120 h with time intervals of 3 h was adopted for each backward trajectory. Since the topography is characterized by huge relief differences in the Mt. Everest region, the arrival height of trajectories was set to 1000 m above the surface to reveal the long-range transport of air masses.

3.1 Ionic characteristics and potential sulfate sources

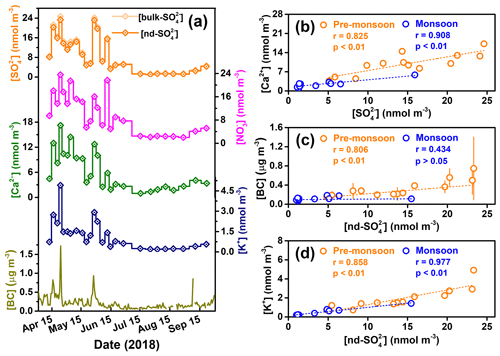

Over the entire sampling campaign, concentrations of the main water-soluble ionic species (e.g., , , Ca2+, K+) extracted from TSP samples in the Mt. Everest region show very similar and clear seasonal variations (Fig. 2a). That is, concentrations in the pre-monsoon seasons are 3–4 times higher than those during the monsoon season. It is likely the seasonal variations in the main ionic concentrations mainly result from the scavenging effect of precipitation in the monsoon season and more frequent dust storms in the pre-monsoon season (Kang et al., 2000). Our measurements indicate that was the most abundant inorganic anion species followed by , while for cations, Ca2+ was the most abundant species. Although the Mt. Everest region is far from human activities and is one of the most pristine areas in the world, we observed much higher sulfate concentrations ([]), with an average of 9.4±7.6 nmol m−3 during the sampling period in this region, than those in the polar regions. For example, an annual mean [] of 1.7 and 0.8 nmol m−3 was observed from Antarctic at the Dumont d'Urville station (DDU) and Dome C, respectively (Ishino et al., 2017; Hill-Falkenthal et al., 2013); Massling et al. (2015) reported seasonal mean values of [] within the range of 1.2 to 5.0 nmol m−3 from northeastern Greenland. The elevated [] in our study might suggest a significant contribution of long-range-transported polluted air masses with sulfur sources.

Figure 2(a) Temporal variations in concentrations of major ions and BC in TSP samples collected from the Mt. Everest region across the entire study period, and (b–d) correlations between [bulk-] and [Ca2+], [nd-] and [BC], and [nd-] and [K+] in the pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons. The error bars in (c) stand for 1σ uncertainty.

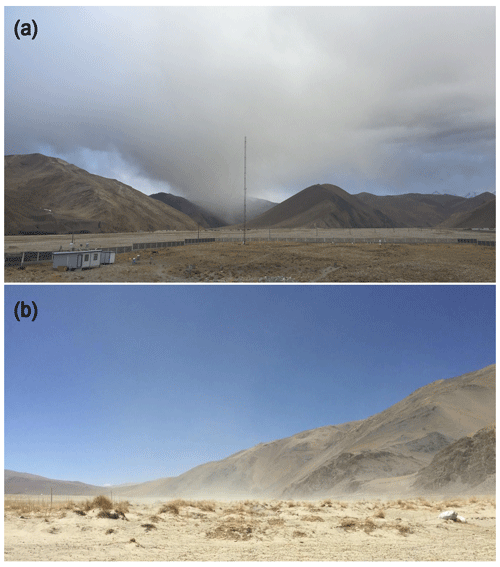

Figure 3Pictures of a dust storm (a) as well as the re-suspended dust (b) in the Mt. Everest region.

Due to the relatively high amounts of Na+ in blank filter papers and/or low Na+ concentrations ([Na+]) in environmental samples, the [Na+] data in most of the samples are unavailable and thus the [Na+] are not reported in this study. Indeed, a previous study has indicated that the Cl− and Na+ only make up a very minor portion of total ions in TSP and suggested a negligible influence of sea salt at QOMS (Cong et al., 2015a). In conclusion, the Mt. Everest region, which is located at high elevation and ∼750 km away from the ocean, is considered to possess a negligible amount of sea-salt sulfate in its air masses. In addition, the contribution of primary sulfate emitted from anthropogenic activity has been considered to be insignificant as compared to those from the secondary sulfate produced through oxidation of SO2 (Berresheim et al., 1995). Thus, mineral dust is considered to be the only significant source of primary sulfate in our study due to frequently occurring dust storms (Fig. 3) as well as the significant correlations between and Ca2+ in both seasons (r=0.825, p<0.01 for the pre-monsoon season; r=0.908, p<0.01 for the monsoon season) (Fig. 2b). Since Ca2+ is a typical tracer of crustal materials (dust) (Ram et al., 2010; Kang et al., 2000), here we use a mass ratio (k) of to Ca2+ to correct sulfate concentrations and Δ17O values for non-dust sulfate (nd-) which can be regarded as secondary atmospheric sulfate (SAS). In addition, given that primary sulfate possesses 0 ‰ of Δ17O, Δ17O values for nd- () were calculated based on the following equations:

where [bulk-] and represent concentration and Δ17O value of bulk sulfate, respectively. Here we adopt a k value of 0.18, corresponding to a molar ratio of 0.075, which has been widely used in previous studies for the estimation of the terrigenous sulfate (Lin et al., 2021; Kunasek et al., 2010; Patris et al., 2002). Note that the k value of 0.59, corresponding to a molar ratio of 0.246, is known to be an upper limit as discussed in Kaufmann et al. (2010) and Goto-Azuma et al. (2019). If this upper limit of the k value is adopted into the calculation, this would result in higher values; however, the seasonal trend of as discussed below does not change and is even more pronounced (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The uncertainties for values were estimated by propagating the uncertainties of [] and [Ca2+] (4 %) as well as 1σ precision of corrected Δ17O (0.1 ‰). All sulfate concentrations and the isotopic data are detailed in Table 1. The average contribution of terrigenous sulfate to the bulk sulfate is correspondingly calculated to be 6.3 %±3.0 %. Note that, although the terrigenous sulfate has been generally considered to possess zero Δ17O signal (Dominguez et al., 2008; Lee and Thiemens, 2001), some previous studies observed positive Δ17O values in sulfate mineral deposits formed in arid surface environments (e.g., central Namib Desert and Antarctic dry-valley soils) due to atmospheric deposition (Bao et al., 2000b; Bao et al., 2000a). If this is also true for the Mt. Everest region, the estimated would be overestimated. However, the overestimation should be very limited due to the small portion of terrigenous sulfate (6.3 %±3.0 %) in our study. As described in Sect. 3.2, the average in the Mt. Everest region is 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰. If we assume that half of the terrigenous sulfate originates from the oxidation processes in the atmosphere, the estimated would be ∼1.6 ‰, which is slightly lower than the reported data in our study. Thus, the potential overestimation would not change our discussion or conclusions.

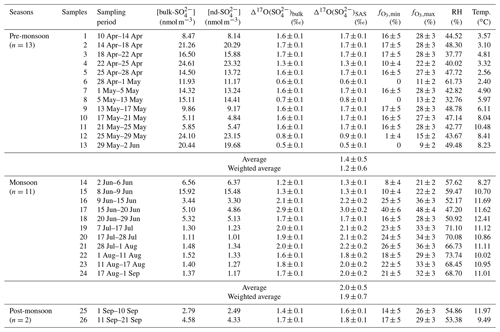

Table 1Concentrations and Δ17O values of atmospheric sulfate collected in the Mt. Everest region for individual sampling durations as well as the corresponding meteorological parameters including relative humidity (RH) and temperature. The relative contribution of SO2 oxidation by O3 to SAS for each sample is also shown as and .

To identify the possible sources of air masses arriving in the Mt. Everest region during the sampling campaign, we analyzed the 5 d backward trajectory of air masses (Fig. 1a). The results showed that the northward trajectories account for less than 10 % of the total trajectories, and the air masses originated mainly from Nepal, northern–northeastern India, and Bangladesh. Previous studies have indicated that atmospheric brown clouds, basically layers of atmospheric pollution consisting of aerosols such as BC, dust, sulfate, and nitrate, extend from South Asia and accumulate on the southern slope of the Himalayas (Ramanathan et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2014). These South Asia-sourced pollutants can be transported into the TP region via the larger-scale atmospheric circulation and/or a south–north-trending valley wind system (Cong et al., 2015a, b; Chen et al., 2018; Xia et al., 2011). Li et al. (2016) indicated that BC aerosols originating from the Indo-Gangetic Plain can be transported to the Himalayas and even further to the southern TP. As shown in Fig. 2c, the [nd-] showed a consistent seasonality similar to [BC] during the sampling period, especially for the pre-monsoon season, during which time a significant correlation (r=0.806, p<0.01) exists. Note that the insignificant correlation (r=0.434, p>0.05) in the monsoon season might be due to the much lower scavenging ratio of BC than that of (Cerqueira et al., 2010). As a marker of biomass burning, [K+] also showed significant correlations with [nd-] in both seasons (r=0.858, p<0.01 for the pre-monsoon season; r=0.977, p<0.01 for the monsoon season) (Fig. 2d). Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that combustion sources in South Asia contribute significantly to the atmospheric sulfate level in the Mt. Everest region, and even the entire southern TP.

3.2 Δ17O signatures of sulfate and comparison with other sites

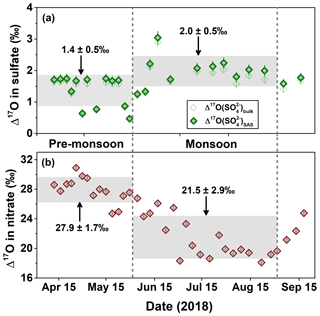

As listed in Table 1, the values in the Mt. Everest region range from 0.5 ‰ to 2.9 ‰ with an average of 1.5 ‰±0.5 ‰ (weighted averaged at 1.3 ‰±0.5 ‰), while for , the values increased from 0.5 ‰ in the pre-monsoon season to a maximum of 3.0 ‰ in the monsoon season with an average of 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰ (weighted averaged at 1.4 ‰±0.7 ‰). The difference in values between different seasons is statistically significant as suggested by a t test (p<0.01). In the pre-monsoon season (n=13), the values fell in the range from 0.5 ‰ to 1.7 ‰ with an average of 1.4 %±0.5 ‰ (weighted averaged at 1.2 ‰±0.6 ‰), which is obviously lower than that of 2.0 ‰±0.5 ‰ (weighted averaged at 1.9 ‰±0.7 ‰) in the monsoon season (n=11) with a range from 1.3 ‰ to 3.0 ‰ (Fig. 4a). Additionally, no apparent correlation is observed between and [bulk-] in any seasons, indicating that the seasonality of was not controlled by the dust-sourced sulfate with a zero Δ17O value.

Figure 4Seasonal changes in (a) and (this study) and (b) in the Mt. Everest region (K. Wang et al., 2020). The light grey horizontal bands are the seasonal average of Δ17O with 1σ uncertainty. For and , the error bars are analytical uncertainties, while for , the error bars stand for the propagated analytical uncertainties.

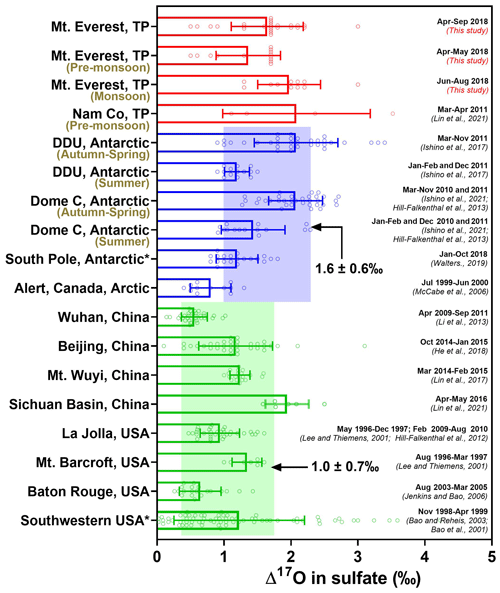

Figure 5Compilation of Δ17O in modern atmospheric sulfate observed at diverse geographic localities to date, including the TP region (red), polar regions (blue), and other mid-latitude regions (green). values were averaged with 1σ uncertainty. An asterisk (*) represents Δ17O values measured from bulk atmospheric sulfate, which will bias these Δ17O observations low; the remaining stand for Δ17O values in SAS.

While most measurements of conducted from the mid-latitudes show weak seasonality in (e.g., Jenkins and Bao, 2006; Li et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2017), a clear seasonality was observed in the polar regions (Walters et al., 2019; Ishino et al., 2017, 2021; Hill-Falkenthal et al., 2013; McCabe et al., 2006). Figure 5 summarizes the available sulfate data so far in the present atmosphere (excluding ice core, gypcrete, volcanic ash, and soil) from different geographic areas, most of which stand for Δ17O values in SAS. These observations indicate that atmospheric sulfate over much of the Earth's mid-latitude continents today appear to have relatively lower Δ17O values (averaged at 1.0 ‰±0.7 ‰, n=225) than those observed from the polar regions (averaged at 1.6 ‰±0.6 ‰, n=128). We note that seasonality with minima in the summer and higher values in the autumn to spring was observed in polar regions (Walters et al., 2019; Ishino et al., 2017; Hill-Falkenthal et al., 2013; McCabe et al., 2006), as summarized in Fig. 5, which likely reflects a seasonal shift from OH- and H2O2- to O3-dominated chemistry.

Our observed data in the Mt. Everest region (averaged at 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰) show higher values than those obtained from most of the previous measurements at a similar latitude and are comparable to those from the polar regions. However, the increase in values from the pre-monsoon season (i.e., spring) to the monsoon season (i.e., summer) is opposite to typical seasonality observed in polar regions (Fig. 5). Note that an average value of 1.1 ‰±0.6 ‰ (n=4) was observed at the northern edge of the southern TP (Nam Co) within the pre-monsoon season (Lin et al., 2016). If SAS fractions for these Nam Co samples are corrected using the same method outlined previously, an average value of 2.1 ‰±1.1 ‰ is obtained (Lin et al., 2021). Several high values (averaged at 1.9 ‰±0.3, n=6) are also observed at a suburban site in the Sichuan Basin in southwestern China, likely due to inputs of sulfates transported from the Himalayas and southern Tibetan Plateau via the westerly jet (Lin et al., 2021). These results are in agreement with our new measurements made in the Mt. Everest region, potentially indicating that the relatively higher might extensively exist within the southern TP and even its downwind region.

Due to the sunlight-driven seasonal changes in the photochemical activity, the oxidants with low or zero Δ17O signature, e.g., HOx, ROx, and H2O2, are more abundant in warm seasons relative to cold seasons. Accordingly, the Δ17O values are expected to show a specific seasonal trend with minima in warm seasons and maxima in cold seasons. In fact, the seasonal trend of Δ17O values in () in the same samples (K. Wang et al., 2020) shows a typical seasonality (Fig. 4) reflecting the sunlight-driven seasonal changes in the photochemical oxidants, which has been reported in many previous studies conducted from diverse geographic sites (e.g., Michalski et al., 2003; Savarino et al., 2007; Guha et al., 2017; Y. L. Wang et al., 2019). Thus, the clear seasonal trends of high in the warm season and low in the cold season observed in the Mt. Everest region imply the existence of a characteristic factor controlling sulfate formation.

3.3 Implications for the formation mechanism of sulfate in the Mt. Everest region

3.3.1 Contribution of stratospheric intrusion

Sulfate in the stratosphere, mainly produced by the reaction of SO2 with OH (high Δ17O in the stratosphere due to the lack of liquid water for isotopic exchange), has been suggested as a potential contributor to the relatively higher (Jenkins and Bao, 2006). Additionally, O3 in the stratosphere also has a higher Δ17O value (34.2 ‰±3.7 ‰ for bulk oxygen atoms) as compared with that in the troposphere (Krankowsky et al., 2000). Numerical simulations and field-based observations show that the Himalayas are a global hot spot for deep stratospheric intrusion (SI) in the springtime (pre-monsoon) (Škerlak et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2016, 2021). A recent study carried out at the southern TP and downwind in southwestern China observed high values in springtime aerosol samples that were influenced by the downward transport of stratospheric air, preliminary suggesting the potential causal link between values and the stratospheric influences (Lin et al., 2021). We therefore first evaluate the potential stratospheric influence on the relatively higher values in our study. Previous studies suggest that SI frequency at the southern TP is generally lower in summer than in spring (Priyadarshi et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2017). in our study, however, displays higher values in summer than spring. Consequently, the observed high values, especially in summer, may not be predominately explained by the stratospheric influences. The stratospheric contribution to each individual sample, which may be quantified and constrained in the future by simultaneous measurements of chemical tracers for stratospheric air masses, is beyond the scope of this study. In the ensuing sections, we focus on the role of sulfate formation mechanisms in the troposphere in elevating values.

3.3.2 Importance of S(IV)+O3 oxidation pathway

Given that the signatures for the sulfate formation pathways are all lower than 0.8 ‰ except for the S(IV)+O3 pathway (), the atmospheric sulfate values with ‰ clearly indicate the role of O3 in sulfate production. The high values with an average of 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰ in the Mt. Everest region suggest a significant role of oxidation of S(IV) by O3 in the formation of atmospheric sulfate in this region. Here, by applying a simple isotope mass-balance method (Eqs. 3 and 4) (Walters et al., 2019), we calculated the maximum contribution of oxidation by O3 () to SAS production by assuming that TMI-catalyzed oxidation by O2 is the only other pathway, and the minimum contribution (), on the other hand, was estimated by assuming that O3 and H2O2 are the only oxidants.

where ‰, ‰, and ‰ as indicated above. The results show an estimated O3 contribution range ( to ) of 15 %±10 % to 27 %±9 % corresponding to the mean value of 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰ for the entire sampling period. Based on the seasonal average values (1.4 ‰±0.5 ‰ for the pre-monsoon season and 2.0 ‰±0.5 ‰ for the monsoon season) and estimation of by the above isotope mass-balance method, the fell in a range of 10 %±9 % to 23 %±8 % and 21 %±9 % to 32 %±8 % for the pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons, respectively. The relative contribution of aqueous oxidation by O3 is significantly higher in the monsoon than in the pre-monsoon season.

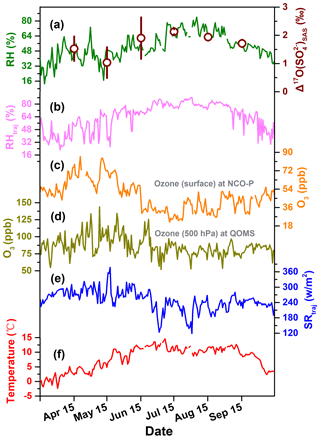

Figure 6Seasonal patterns of (a) relative humidity (RH) and monthly weighted average values of with 1σ uncertainty, (b) relative humidity along with backward trajectories arriving at the sampling sites (RHtraj), (c) ozone mixing ratio at surface level at NCO-P from Putero et al. (2018), (d) ozone mixing ratio at 500 hPa at QOMS, (e) solar radiation fluxes along with backward trajectories arriving at the sampling sites (SRtraj), and (f) temperature.

In Fig. 6, we compare the seasonal variation of observed with these meteorological parameters in this region. Interestingly, the RH at QOMS during the sampling period shows co-variation with our observed with a statistically significant correlation (r=0.845, p<0.05), although this correlation between and RH along with the air-mass transport pathways is less significant (r=0.697, p=0.124) (Fig. 6a and b). In contrast, tropospheric O3 concentrations, acquired from both the northern and southern slopes of Mt. Everest at the QOMS and NCO-P, show seasonal variations with significantly higher levels in the pre-monsoon season than in the monsoon season (Fig. 6c and d), indicating that O3 abundance is not the ultimate determinant of seasonal variation in . The solar radiation along with the air-mass transport pathways was stronger in the pre-monsoon season than in the monsoon season, which might explain the seasonality of via facilitating SO2 oxidation by OH ( ‰). However, if this is the case, relatively lower values should be observed in the pre-monsoon season due to enhancement of NO2+OH pathways producing low values, but this variation was not observed (Fig. 4b and K. Wang et al., 2020). Thus, this explanation is not likely to dominate the characteristic values in the Mt. Everest region. Although we cannot extract clear relations of with the meteorological parameters, the relatively high values in this region imply the importance of aqueous oxidation of S(IV) by O3. We therefore discuss the importance of atmospheric acidity in the aqueous-phase chemistry as factor controlling the S(IV)+O3 oxidation pathway in the next section.

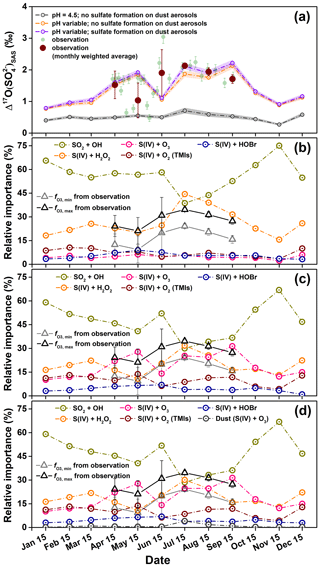

Figure 7(a) Comparison of modeled and observed in the Mt. Everest region. The shaded area for the modeled indicates the 1σ uncertainty. (b–d) Modeled relative fraction of sulfate formation pathways under the conditions of (b) cloud water pH=4.5 and no sulfate formation on dust aerosols, (c) variable cloud water pH and no sulfate formation on dust aerosols, and (d) variable cloud water pH and considering the sulfate formation on dust aerosols. The estimated contributions of O3+S(IV) based on observations ( and ) were also plotted in (b–d).

Figure 8Schematic illustration of South Asia-sourced sulfate aerosols as well as their formation mechanism in the troposphere during the long-range cross-border transport over the Himalayas, which contribute significantly to the sulfate levels in the Mt. Everest region, and even the entire southern TP.

3.3.3 Importance of atmospheric acidity for sulfate formation pathways

The aqueous oxidation of S(IV) by O3 is only significant at high-pH conditions greater than pH=5, due to the strong pH dependence of S(IV) species in solutions (Calvert et al., 1985; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). At the pH below 5, H2O2 is considered to dominate aqueous sulfate production. Since the pH in modern cloud water is typically within the range of 3 to 5 (Pye et al., 2020, and references therein), the aqueous oxidation of S(IV) by O3 is thus considered to be unimportant when compared to the oxidation by H2O2. However, our observed high values suggest the importance of sulfate formation by aqueous oxidation of S(IV) by O3, indicating that sulfate formation is occurring at relatively high-pH conditions. Indeed, the pH values in fog, rain, and snow in the TP region were reported to be high (pH=6.4, 6.2, and 5.96±0.54, respectively; W. Wang et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2002), and the modeled cloud water pH in the Mt. Everest region and the South Asia showed approximately pH=6 (Shah et al., 2020; Pye et al., 2020). Such high-pH conditions favor S(IV) oxidation by O3. We suggest that the frequently occurring dust storms, not only in the Mt. Everest region but also in South Asia (Fig. 3 and Prospero et al., 2002), are likely to play an important role in promoting the S(IV) oxidation by O3 through the conditions of high cloud water pH. That is, the sulfate produced in South Asia and during the long-range transport should contribute significantly to the observed sulfate in the Mt. Everest region. Consequently, our findings provide an important observational basis for better constraints on the importance of pH in sulfate formation pathways.

To examine the importance of cloud water pH and sulfate formation on dust surface, we conducted model simulations by GEOS-Chem in three cases including (i) fixed cloud water pH (=4.5) and no consideration of sulfate formation on dust surface, (ii) variable cloud water pH and no consideration of sulfate formation on dust surface, and (iii) variable cloud water pH and consideration of sulfate formation on dust surface. Note that the sulfate simulated by the chemical transport model includes both local and distant sources of sulfate, and thus the estimated also includes sulfate produced during the transport. The results show that, if the cloud water pH is fixed to 4.5, the modeled monthly-mean values range from 0.5 ‰ to 0.7 ‰ during the sampling period (April to September), significantly lower than the observed monthly weighted average values with a range of 1.0 ‰ to 2.1 ‰ in the Mt. Everest region (Fig. 7a). On the other hand, when considering variable cloud water pH (i.e., cases ii and iii), the modeled values increase markedly with a range of 1.1 ‰ to 2.2 ‰ (Fig. 7a). The increases in modeled when calculating cloud water pH are due to increases in the modeled from 5 %±1 % in case (i) (Fig. 7b) to 24 %±6 % in cases (ii) and/or (iii) (Fig. 7c and d). In addition to the magnitude of , is also well reproduced by the model simulations in cases (ii) and (iii). During the sampling period, the modeled monthly-mean in cases (ii) and (iii) varied from 14 % to 31 % with an average of 24 %±6 %, which shows a good agreement with calculated based on Eqs. (3) and (4) (15 %±10 % for and 27 %±9 % for , respectively) (Fig. 7c and d). It is important to note that the modeled in cases (ii) and/or (iii) is even higher than the modeled (averaged at 20 %±7 %). Also, as shown in Fig. 7d, the modeled heterogeneous S(IV) oxidation on dust surface also play a role in producing high values, particularly in the pre-monsoon season, but the modeled relative contribution of this pathway does not exceed 5 % to the total sulfate production.

The above results show that the consideration of variable cloud water pH significantly improved the model's ability to simulate the in the Mt. Everest region, which indicates the importance of atmospheric acidity in favoring the oxidation of S(IV) by O3 in this region. Overall, our observed result with high values found in the Mt. Everest region, in turn, highlights observational evidence that atmospheric acidity plays an important role in controlling sulfate formation pathways, particularly for dust-rich environments. For typical earlier studies until the 1990s, pH of cloud droplet was considered too low to promote the S(IV)+O3 reaction for sulfate formation (Chin et al., 1996; Koch et al., 1999). Although recent studies have proposed the importance of the cloud water pH in promoting the S(IV)+O3 pathway to estimate atmospheric sulfate formation (Paulot et al., 2014; Banzhaf et al., 2012; Hattori et al., 2021), even the latest study (Turnock et al., 2019) still prescribes a constant cloud pH in the estimation for radiative forcing effect via aerosols. Consequently, an accurate estimate of cloud water pH in the model simulation and elucidation of its relation to atmospheric sulfate formation are necessary for precise model forecasts, and observations of are important constraints on model validation.

3.3.4 Possible importance of atmospheric humidity on

Although the model in this study predicted minor relative contribution of heterogeneous oxidation of SO2 by O3 on dust surface (Fig. 7d), it is worth noting the possible importance of this pathway. The adsorption of SO2 is thought to be one of the important rate-determining steps for SO2 oxidation on dust surface, suggesting that the heterogeneous reactions on dust surface are very dependent on the SO2 uptake coefficient, which is further determined by RH (Bauer and Koch, 2005; Li et al., 2006). By increasing the hygroscopicity of atmospheric aerosols, RH can promote SO2 oxidation on the surface of dust aerosols. Thus, RH should play a crucial role in the heterogeneous oxidation processes. In a laboratory study, Ullerstam et al. (2002) observed a 47 % increase in the amount of sulfate formed via SO2 oxidation by O3 on dust surface when dust samples were exposed to a RH of 80 % as compared to an experiment without the intermittent water exposure. Thus, the relatively high RH during the monsoon season in the Mt. Everest region would facilitate the heterogeneous SO2 oxidation by O3 on the alkaline dust surface, which increases the overall fraction of the S(IV)+O3 reaction and results in relatively higher values in the monsoon season than that in the pre-monsoon season. Taken together with the co-variation between and RH as described above (Fig. 7a and b), there is thus a possibility that the ubiquitous alkaline dust aerosols extending from South Asia to the Mt. Everest region as reported in previous studies (e.g., T. Wang et al., 2020; Prospero et al., 2002) render a suitable condition for S(IV) oxidation by O3, especially during the monsoon season. Also note that, although the seasonal trends in Δ17O for both nitrate and sulfate result from the relative importance of the S(IV)+O3 pathway, the mechanisms behind it are different. For nitrate, the main factor controlling the Δ17O seasonality is the O3 concentrations, while for sulfate, RH might play a more important role in determining the Δ17O seasonality as discussed above. Given that soluble Ca2+ and Mg2+, those being thought to provide alkalinity, mostly exist as coarse-mode particles larger than 1 µm (Yang et al., 2016), size distributions of sulfate concentration and for dust-rich environments would provide a detailed consequence for the importance of heterogeneous oxidation of SO2 by O3 on the dust surface in the future study.

In this study, we report observations of sulfate concentrations and in aerosol samples collected from the Mt. Everest region over a period including pre-monsoon and monsoon seasons in 2018. The combustion tracers (i.e., BC and K+) as well as the backward trajectories of air masses suggest combustion sources (e.g., fossil fuel and biomass combustion) in South Asia contributed significantly to the observed sulfate. The average value of 1.7 ‰±0.5 ‰ observed from the Mt. Everest region is higher than the published data reported from the Earth's mid-latitude continents which have relatively lower values (1.0 ‰±0.7 ‰). Intriguingly, a seasonal variation of with high values during the monsoon (warm) season and low values in the pre-monsoon (cold) season was observed in this study, which is opposite to that of measured from the same aerosol samples as well as that of observed from the polar regions. The relatively high values in this region imply the importance of aqueous oxidation of S(IV) by O3 which is favored by high-pH conditions. An updated global three-dimensional chemical transport model with high-pH conditions better reproduced the observed high values in the Mt. Everest region. As illustrated in Fig. 8, we propose that the S(IV) oxidation by O3 in South Asia as well as during long-range transport over the Himalayas contributes significantly to the sulfate levels in the Mt. Everest region, and even the entire southern TP. Overall, our study provides observational evidence that atmospheric acidity plays an important role in controlling sulfate formation pathways, particularly for dust-rich environments. Such identification of key processes provides an important basis for better understanding of the sulfur cycle in the TP, which is also meaningful for the accurate evaluation of the environment and climatic changes within this region.

The data used for the figures and the interpretations have been included in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-8357-2021-supplement.

KW, SK, and SH designed the study. KW and SK organized the Mt. Everest field campaign and collected samples. SH, KW, ML, SI, and KK carried out the experiments. SH, SI, and BA performed the model simulations and analysis. KW and SH analyzed the data with contributions from SK, ML, BA, and NY. KW and SH prepared the paper with contributions from all other co-authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This project was financially supported by the second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) (no. 2019QZKK0605) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 41705132 (Shichang Kang), 41630754 (Shichang Kang), 42021002 (Mang Lin)). Kun Wang acknowledges the China Scholarship Council under no. 201804910810. This work was carried out within a framework across the Tibetan Plateau: Atmospheric Pollution and Cryospheric Change (APCC). We would like to thank the staff working at the Qomolangma Station for Atmospheric and Environmental Observation and Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for their valuable help with field sampling and supplying the meteorological dataset. Also, we acknowledge CNR-ISAC (Institute of Atmospheric Sciences and Climate of the National Research Council of Italy) and the Ev-K2-CNR Chartered Association for providing the O3 dataset at NCO-P and managing/supporting the NCO-P station as well as the on-site scientific operation. The authors also thank the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts for the ERA-Interim reanalysis dataset (https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/datasets/reanalysis-datasets/era-interim, last access: 24 May 2021). The authors gratefully acknowledge the NOAA Air Resources Laboratory for the provision of the HYSPLIT transport and dispersion model and READY website (https://www.ready.noaa.gov, last access: 24 May 2021) used in this publication. This study was also supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grants JP18F18113 (Naohiro Yoshida), JP18K19850 (Shohei Hattori), JP19H01143 (Shohei Hattori), JP20H04305 (Shohei Hattori), JP16H05884 (Shohei Hattori), and JP17H06105 (Naohiro Yoshida)) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. Becky Alexander acknowledges support from NSF AGS 1644998. Mang Lin acknowledges financial support from the JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowship and Guangdong Pearl River Talents Program (2019QN01L150). We acknowledge two anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

This research has been supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant nos. KAKENHI JP20H04305, KAKENHI JP19H01143, KAKENHI JP16H05884, KAKENHI JP17H06105, KAKENHI JP18F18113, and KAKENHI JP18K19850), the National Science Foundation (grant no. AGS 1644998), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 41705132, 41630754, and 42021002), and the second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) (grant no. 2019QZKK0605).

This paper was edited by Eliza Harris and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alexander, B., Savarino, J., Barkov, N., Delmas, R., and Thiemens, M.: Climate driven changes in the oxidation pathways of atmospheric sulfur, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 1685, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014879, 2002.

Alexander, B., Park, R. J., Jacob, D. J., Li, Q., Yantosca, R. M., Savarino, J., Lee, C., and Thiemens, M.: Sulfate formation in sea-salt aerosols: Constraints from oxygen isotopes, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 110, D10307, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JD005659, 2005.

Alexander, B., Park, R. J., Jacob, D. J., and Gong, S.: Transition metal-catalyzed oxidation of atmospheric sulfur: Global implications for the sulfur budget, J. Geophys. Res., 114, D02309, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010486, 2009.

Alexander, B., Allman, D., Amos, H., Fairlie, T., Dachs, J., Hegg, D. A., and Sletten, R. S.: Isotopic constraints on the formation pathways of sulfate aerosol in the marine boundary layer of the subtropical northeast Atlantic Ocean, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 117, D06304, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016773, 2012.

Banzhaf, S., Schaap, M., Kerschbaumer, A., Reimer, E., Stern, R., Van Der Swaluw, E., and Builtjes, P.: Implementation and evaluation of pH-dependent cloud chemistry and wet deposition in the chemical transport model REM-Calgrid, Atmos. Environ., 49, 378–390, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.10.069, 2012.

Bao, H., Campbell, D. A., Bockheim, J. G., and Thiemens, M. H.: Origins of sulphate in Antarctic dry-valley soils as deduced from anomalous 17O compositions, Nature, 407, 499–502, https://doi.org/10.1038/35035054, 2000a.

Bao, H., Thiemens, M. H., Farquhar, J., Campbell, D. A., Lee, C. C.-W., Heine, K., and Loope, D. B.: Anomalous 17O compositions in massive sulphate deposits on the Earth, Nature, 406, 176–178, https://doi.org/10.1038/35018052, 2000b.

Bao, H., Michalski, G. M., and Thiemens, M. H.: Sulfate oxygen-17 anomalies in desert varnishes, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 65, 2029–2036, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00490-7, 2001.

Bao, H. and Reheis, M. C.: Multiple oxygen and sulfur isotopic analyses on water-soluble sulfate in bulk atmospheric deposition from the southwestern United States, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 108, 4430, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD003022, 2003.

Bauer, S. E. and Koch, D.: Impact of heterogeneous sulfate formation at mineral dust surfaces on aerosol loads and radiative forcing in the Goddard Institute for Space Studies general circulation model, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 110, D17202, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd005870, 2005.

Berresheim, H., Wine, P., and Davis, D.: Sulfur in the atmosphere, in: Composition, chemistry, and climate of the atmosphere, edited by: Singh, H. B., Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 251–307, 1995.

Bey, I., Jacob, D. J., Yantosca, R. M., Logan, J. A., Field, B. D., Fiore, A. M., Li, Q., Liu, H. Y., Mickley, L. J., and Schultz, M. G.: Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 106, 23073–23095, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jd000807, 2001.

Calvert, J. G., Lazrus, A., Kok, G. L., Heikes, B. G., Walega, J. G., Lind, J., and Cantrell, C. A.: Chemical mechanisms of acid generation in the troposphere, Nature, 317, 27–35, https://doi.org/10.1038/317027a0, 1985.

Cerqueira, M., Pio, C., Legrand, M., Puxbaum, H., Kasper-Giebl, A., Afonso, J., Preunkert, S., Gelencsér, A., and Fialho, P.: Particulate carbon in precipitation at European background sites, J. Aerosol Sci., 41, 51–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2009.08.002, 2010.

Chang, J., Brost, R., Isaksen, I., Madronich, S., Middleton, P., Stockwell, W., and Walcek, C.: A three-dimensional Eulerian acid deposition model: Physical concepts and formulation, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 92, 14681–14700, https://doi.org/10.1029/jd092id12p14681, 1987.

Charlson, R. J., Schwartz, S., Hales, J., Cess, R. D., Coakley, J. J., Hansen, J., and Hofmann, D.: Climate forcing by anthropogenic aerosols, Science, 255, 423–430, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.255.5043.423, 1992.

Chen, Q., Geng, L., Schmidt, J. A., Xie, Z., Kang, H., Dachs, J., Cole-Dai, J., Schauer, A. J., Camp, M. G., and Alexander, B.: Isotopic constraints on the role of hypohalous acids in sulfate aerosol formation in the remote marine boundary layer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11433–11450, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11433-2016, 2016.

Chen, Q., Schmidt, J. A., Shah, V., Jaeglé, L., Sherwen, T., and Alexander, B.: Sulfate production by reactive bromine: Implications for the global sulfur and reactive bromine budgets, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 7069–7078, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl073812, 2017.

Chen, X., Kang, S., Cong, Z., Yang, J., and Ma, Y.: Concentration, temporal variation, and sources of black carbon in the Mt. Everest region retrieved by real-time observation and simulation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 12859–12875, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-12859-2018, 2018.

Chin, M., Jacob, D. J., Gardner, G. M., Foreman-Fowler, M. S., Spiro, P. A., and Savoie, D. L.: A global three-dimensional model of tropospheric sulfate, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 101, 18667–18690, https://doi.org/10.1029/96jd01221, 1996.

Cong, Z., Kang, S., Kawamura, K., Liu, B., Wan, X., Wang, Z., Gao, S., and Fu, P.: Carbonaceous aerosols on the south edge of the Tibetan Plateau: concentrations, seasonality and sources, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 1573–1584, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-1573-2015, 2015a.

Cong, Z., Kawamura, K., Kang, S., and Fu, P.: Penetration of biomass-burning emissions from South Asia through the Himalayas: new insights from atmospheric organic acids, Sci. Rep., 5, 9580, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09580, 2015b.

Cristofanelli, P., Bracci, A., Sprenger, M., Marinoni, A., Bonafè, U., Calzolari, F., Duchi, R., Laj, P., Pichon, J. M., Roccato, F., Venzac, H., Vuillermoz, E., and Bonasoni, P.: Tropospheric ozone variations at the Nepal Climate Observatory-Pyramid (Himalayas, 5079 m a.s.l.) and influence of deep stratospheric intrusion events, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 6537–6549, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-6537-2010, 2010.

Dee, D. P., Uppala, S. M., Simmons, A., Berrisford, P., Poli, P., Kobayashi, S., Andrae, U., Balmaseda, M., Balsamo, G., and Bauer, D. P.: The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 553–597, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.828, 2011.

Dentener, F., Williams, J., and Metzger, S.: Aqueous phase reaction of HNO4: The impact on tropospheric chemistry, J. Atmos. Chem., 41, 109–133, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014233910126, 2002.

Dominguez, G., Jackson, T., Brothers, L., Barnett, B., Nguyen, B., and Thiemens, M. H.: Discovery and measurement of an isotopically distinct source of sulfate in Earth's atmosphere, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 105, 12769–12773, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0805255105, 2008.

Duan, J., Esper, J., Buntgen, U., Li, L., Xoplaki, E., Zhang, H., Wang, L., Fang, Y., and Luterbacher, J.: Weakening of annual temperature cycle over the Tibetan Plateau since the 1870s, Nat. Commun., 8, 14008–14008, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14008, 2017.

Fairlie, T. D., Jacob, D. J., and Park, R. J.: The impact of transpacific transport of mineral dust in the United States, Atmos. Environ., 41, 1251–1266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.09.048, 2007.

Fairlie, T. D., Jacob, D. J., Dibb, J. E., Alexander, B., Avery, M. A., van Donkelaar, A., and Zhang, L.: Impact of mineral dust on nitrate, sulfate, and ozone in transpacific Asian pollution plumes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 3999–4012, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-3999-2010, 2010.

Feingold, G., Frost, G. J., and Ravishankara, A.: Role of NO3 in sulfate production in the wintertime northern latitudes, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, 4640, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002jd002288, 2002.

Gautier, E., Savarino, J., Hoek, J., Erbland, J., Caillon, N., Hattori, S., Yoshida, N., Albalat, E., Albarede, F., and Farquhar, J.: 2600 years of stratospheric volcanism through sulfate isotopes, Nat. Commun., 10, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08357-0, 2019.

Geng, L., Schauer, A. J., Kunasek, S. A., Sofen, E. D., Erbland, J., Savarino, J., Allman, D. J., Sletten, R. S., and Alexander, B.: Analysis of oxygen-17 excess of nitrate and sulfate at sub-micromole levels using the pyrolysis method, Rapid Commun. Mass Sp., 27, 2411–2419, https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.6703, 2013.

Goto-Azuma, K., Hirabayashi, M., Motoyama, H., Miyake, T., Kuramoto, T., Uemura, R., Igarashi, M., Iizuka, Y., Sakurai, T., and Horikawa, S.: Reduced marine phytoplankton sulphur emissions in the Southern Ocean during the past seven glacials, Nat. Commun., 10, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11128-6, 2019.

Guha, T., Lin, C., Bhattacharya, S., Mahajan, A., Ou Yang, C., Lan, Y., Hsu, S., and Liang, M.: Isotopic ratios of nitrate in aerosol samples from Mt. Lulin, a high-altitude station in Central Taiwan, Atmos. Environ., 154, 53–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.01.036, 2017.

Harris, E., Sinha, B., Van Pinxteren, D., Tilgner, A., Fomba, K. W., Schneider, J., Roth, A., Gnauk, T., Fahlbusch, B., and Mertes, S.: Enhanced role of transition metal ion catalysis during in-cloud oxidation of SO2, Science, 340, 727–730, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230911, 2013.

Hattori, S., Iizuka, Y., Alexander, B., Ishino, S., Fujita, K., Zhai, S., Sherwen, T., Oshima, N., Uemura, R., Yamada, A., Suzuki, N., Matoba, S., Tsuruta, A., Savarino, J., and Yoshida, N.: Isotopic evidence for acidity-driven enhancement of sulfate formation after SO2 emission control, Sci. Adv., 7, eabd4610, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd4610, 2021.

He, P., Alexander, B., Geng, L., Chi, X., Fan, S., Zhan, H., Kang, H., Zheng, G., Cheng, Y., Su, H., Liu, C., and Xie, Z.: Isotopic constraints on heterogeneous sulfate production in Beijing haze, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 5515–5528, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-5515-2018, 2018.

Hill-Falkenthal, J., Priyadarshi, A., Savarino, J., and Thiemens, M.: Seasonal variations in 35S and Δ17O of sulfate aerosols on the Antarctic plateau, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 9444–9455, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50716, 2013.

Hoesly, R. M., Smith, S. J., Feng, L., Klimont, Z., Janssens-Maenhout, G., Pitkanen, T., Seibert, J. J., Vu, L., Andres, R. J., Bolt, R. M., Bond, T. C., Dawidowski, L., Kholod, N., Kurokawa, J.-I., Li, M., Liu, L., Lu, Z., Moura, M. C. P., O'Rourke, P. R., and Zhang, Q.: Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS), Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 369–408, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-369-2018, 2018.

Holt, B., Kumar, R., and Cunningham, P.: Oxygen-18 study of the aqueous-phase oxidation of sulfur dioxide, Atmos. Environ., 15, 557–566, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(81)90186-4, 1981.

Immerzeel, W. W., Van Beek, L. P., and Bierkens, M. F.: Climate change will affect the Asian water towers, Science, 328, 1382–1385, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1183188, 2010.

Ishino, S., Hattori, S., Savarino, J., Jourdain, B., Preunkert, S., Legrand, M., Caillon, N., Barbero, A., Kuribayashi, K., and Yoshida, N.: Seasonal variations of triple oxygen isotopic compositions of atmospheric sulfate, nitrate, and ozone at Dumont d'Urville, coastal Antarctica, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 3713–3727, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-3713-2017, 2017.

Ishino, S., Hattori, S., Legrand, M., Chen, Q., Alexander, B., Shao, J., Huang, J., Jaegle, L., Jourdain, B., and Preunkert, S.: Regional characteristics of atmospheric sulfate formation in East Antarctica imprinted on 17O-excess signature, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2020JD033583, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD033583, 2021.

Jenkins, K. A. and Bao, H.: Multiple oxygen and sulfur isotope compositions of atmospheric sulfate in Baton Rouge, LA, USA, Atmos. Environ., 40, 4528–4537, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.04.010, 2006.

Kang, S., Wake, C. P., Qin, D., Mayewski, P. A., and Yao, T.: Monsoon and dust signals recorded in Dasuopu glacier, Tibetan Plateau, J. Glaciol., 46, 222–226, https://doi.org/10.3189/172756500781832864, 2000.

Kang, S., Qin, D., Mayewski, P. A., Sneed, S. B., and Yao, T.: Chemical composition of fresh snow on Xixabangma peak, central Himalaya, during the summer monsoon season, J. Glaciol., 48, 337–339, https://doi.org/10.3189/172756502781831467, 2002.

Kang, S., You, Q., Flügel, W. A., Pepin, N., and Yao, T.: Review of climate and cryospheric change in the Tibetan Plateau, Environ. Res. Lett., 5, 015101, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/5/1/015101, 2010.

Kang, S., Zhang, Q., Qian, Y., Ji, Z., Li, C., Cong, Z., Zhang, Y., Guo, J., Du, W., and Huang, J.: Linking Atmospheric Pollution to Cryospheric Change in the Third Pole Region: Current Progresses and Future Prospects, Natl. Sci. Rev., 6, 796–809, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwz031, 2019.

Kang, S., Zhang, Y., Qian, Y., and Wang, H.: A review of black carbon in snow and ice and its impact on the cryosphere, Earth Sci. Rev., 210, 103346, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103346, 2020.

Kaufman, Y. J. and Tanre, D.: Effect of variations in super-saturation on the formation of cloud condensation nuclei, Nature, 369, 45–48, https://doi.org/10.1038/369045a0, 1994.

Kaufmann, P., Fundel, F., Fischer, H., Bigler, M., Ruth, U., Udisti, R., Hansson, M., De Angelis, M., Barbante, C., and Wolff, E. W.: Ammonium and non-sea salt sulfate in the EPICA ice cores as indicator of biological activity in the Southern Ocean, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 29, 313–323, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.11.009, 2010.

Koch, D., Jacob, D., Tegen, I., Rind, D., and Chin, M.: Tropospheric sulfur simulation and sulfate direct radiative forcing in the Goddard Institute for Space Studies general circulation model, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 104, 23799–23822, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999jd900248, 1999.

Krankowsky, D., Lämmerzahl, P., and Mauersberger, K.: Isotopic measurements of stratospheric ozone, Geophys. Res. Lett., 27, 2593–2595, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000gl011812, 2000.

Kulmala, M., Pirjola, L., and Mäkelä, J. M.: Stable sulphate clusters as a source of new atmospheric particles, Nature, 404, 66–69, https://doi.org/10.1038/35003550, 2000.

Kunasek, S., Alexander, B., Steig, E., Sofen, E., Jackson, T., Thiemens, M., McConnell, J., Gleason, D., and Amos, H.: Sulfate sources and oxidation chemistry over the past 230 years from sulfur and oxygen isotopes of sulfate in a West Antarctic ice core, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 115, D18313, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jd013846, 2010.

Lee, C. W. and Thiemens, M. H.: The δ17O and δ18O measurements of atmospheric sulfate from a coastal and high alpine region: A mass-independent isotopic anomaly, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 106, 17359–17374, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000jd900805, 2001.

Lee, Y. and Schwartz, S. E.: Kinetics of oxidation of aqueous sulfur (IV) by nitrogen dioxide, in: Precipitation Scavenging, Dry Deposition and Resuspension, edited by: Pruppacher, H. R., Semonin, R. G., and Slinn, W. G. N., Elsevier, New York, 453–470, 1983.

Li, C., Bosch, C., Kang, S., Andersson, A., Chen, P., Zhang, Q., Cong, Z., Chen, B., Qin, D., and Gustafsson, Ö.: Sources of black carbon to the Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau glaciers, Nat. Commun., 7, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12574, 2016.

Li, L., Chen, Z. M., Zhang, Y. H., Zhu, T., Li, J. L., and Ding, J.: Kinetics and mechanism of heterogeneous oxidation of sulfur dioxide by ozone on surface of calcium carbonate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 6, 2453–2464, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-2453-2006, 2006.

Li, X., Bao, H., Gan, Y., Zhou, A., and Liu, Y.: Multiple oxygen and sulfur isotope compositions of secondary atmospheric sulfate in a mega-city in central China, Atmos. Environ., 81, 591–599, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.09.051, 2013.

Liang, J. and Jacobson, M. Z.: A study of sulfur dioxide oxidation pathways over a range of liquid water contents, pH values, and temperatures, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 104, 13749–13769, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999jd900097, 1999.

Lim, S., Lee, M., Kim, S.-W., and Laj, P.: Sulfate alters aerosol absorption properties in East Asian outflow, Sci. Rep., 8, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23021-1, 2018.

Lin, M., Zhang, Z., Su, L., Hill-Falkenthal, J., Priyadarshi, A., Zhang, Q., Zhang, G., Kang, S., Chan, C. Y., and Thiemens, M. H.: Resolving the impact of stratosphere-to-troposphere transport on the sulfur cycle and surface ozone over the Tibetan Plateau using a cosmogenic 35S tracer, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 439–456, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015jd023801, 2016.

Lin, M., Biglari, S., Zhang, Z., Crocker, D., Tao, J., Su, B., Liu, L., and Thiemens, M. H.: Vertically uniform formation pathways of tropospheric sulfate aerosols in East China detected from triple stable oxygen and radiogenic sulfur isotopes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 5187–5196, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl073637, 2017.

Lin, M., Wang, K., Kang, S., Li, Y., Fan, Z., and Thiemens, M. H.: Isotopic signatures of stratospheric air at the himalayas and beyond, Sci. Bull., 66, 323–326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.11.005, 2021.

Liu, X. and Chen, B.: Climatic warming in the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades, Int. J. Climatol., 20, 1729–1742, https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0088(20001130)20:14<1729::aid-joc556>3.0.co;2-y, 2000.

Lyons, J. R.: Transfer of mass-independent fractionation in ozone to other oxygen-containing radicals in the atmosphere, Geophys. Res. Lett., 28, 3231–3234, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000gl012791, 2001.

Ma, Y., Wang, Y., Zhong, L., Wu, R., Wang, S., and Li, M.: The characteristics of atmospheric turbulence and radiation energy transfer and the structure of atmospheric boundary layer over the northern slope area of Himalaya, J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn., 89, 345–353, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2011-a24, 2011.

Massling, A., Nielsen, I. E., Kristensen, D., Christensen, J. H., Sørensen, L. L., Jensen, B., Nguyen, Q. T., Nøjgaard, J. K., Glasius, M., and Skov, H.: Atmospheric black carbon and sulfate concentrations in Northeast Greenland, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 9681–9692, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-9681-2015, 2015.

McCabe, J. R., Savarino, J., Alexander, B., Gong, S., and Thiemens, M. H.: Isotopic constraints on non-photochemical sulfate production in the Arctic winter, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L05810, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005gl025164, 2006.

Mchenry, J. N. and Dennis, R. L.: The relative importance of oxidation pathways and clouds to atmospheric ambient sulfate production as predicted by the regional acid deposition model, J. Appl. Meteorol., 33, 890–905, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1994)033<0890:trioop>2.0.co;2, 1994.

Michalski, G., Scott, Z., Kabiling, M., and Thiemens, M. H.: First measurements and modeling of Δ17O in atmospheric nitrate, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 1870, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003gl017015, 2003.

Patris, N., Delmas, R., Legrand, M., De Angelis, M., Ferron, F. A., Stiévenard, M., and Jouzel, J.: First sulfur isotope measurements in central Greenland ice cores along the preindustrial and industrial periods, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, ACH 6-1–ACH 6-11, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jd000672, 2002.

Paulot, F., Jacob, D. J., Pinder, R., Bash, J., Travis, K., and Henze, D.: Ammonia emissions in the United States, European Union, and China derived by high-resolution inversion of ammonium wet deposition data: Interpretation with a new agricultural emissions inventory (MASAGE_NH3), J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 119, 4343–4364, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jd021130, 2014.

Priyadarshi, A., Hill-Falkenthal, J., Thiemens, M., Zhang, Z., Lin, M., Chan, C.-y., and Kang, S.: Cosmogenic 35S measurements in the Tibetan Plateau to quantify glacier snowmelt, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 119, 4125–4135, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013jd019801, 2014.

Prospero, J. M., Ginoux, P., Torres, O., Nicholson, S. E., and Gill, T. E.: Environmental characterization of global sources of atmospheric soil dust identified with the Nimbus 7 Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) absorbing aerosol product, Rev. Geophys., 40, 2-1–2-31, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000rg000095, 2002.

Putero, D., Marinoni, A., Bonasoni, P., Calzolari, F., Rupakheti, M., and Cristofanelli, P.: Black carbon and ozone variability at the Kathmandu Valley and at the southern Himalayas: a comparison between a “hot spot” and a downwind high-altitude site, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 18, 623–635, ap621, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2017.04.0138, 2018.

Pye, H., Liao, H., Wu, S., Mickley, L. J., Jacob, D. J., Henze, D. K., and Seinfeld, J.: Effect of changes in climate and emissions on future sulfate-nitrate-ammonium aerosol levels in the United States, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 114, D01205, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jd010701, 2009.