the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Evaluating the sensitivity of radical chemistry and ozone formation to ambient VOCs and NOx in Beijing

Lisa K. Whalley

Eloise J. Slater

Robert Woodward-Massey

Chunxiang Ye

James D. Lee

Freya Squires

James R. Hopkins

Rachel E. Dunmore

Marvin Shaw

Jacqueline F. Hamilton

Alastair C. Lewis

Archit Mehra

Stephen D. Worrall

Asan Bacak

Thomas J. Bannan

Carl J. Percival

Bin Ouyang

Roderic L. Jones

Leigh R. Crilley

Louisa J. Kramer

William J. Bloss

Simone Kotthaus

Sue Grimmond

Weiqi Xu

Siyao Yue

Lujie Ren

W. Joe F. Acton

C. Nicholas Hewitt

Xinming Wang

Pingqing Fu

Dwayne E. Heard

Measurements of OH, HO2, complex RO2 (alkene- and aromatic-related RO2) and total RO2 radicals taken during the integrated Study of AIR Pollution PROcesses in Beijing (AIRPRO) campaign in central Beijing in the summer of 2017, alongside observations of OH reactivity, are presented. The concentrations of radicals were elevated, with OH reaching up to , HO2 peaking at and the total RO2 concentration reaching . OH reactivity (k(OH)) peaked at 89 s−1 during the night, with a minimum during the afternoon of on average. An experimental budget analysis, in which the rates of production and destruction of the radicals are compared, highlighted that although the sources and sinks of OH were balanced under high NO concentrations, the OH sinks exceeded the known sources (by 15 ppbv h−1) under the very low NO conditions (<0.5 ppbv) experienced in the afternoons, demonstrating a missing OH source consistent with previous studies under high volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions and low NO loadings. Under the highest NO mixing ratios (104 ppbv), the HO2 production rate exceeded the rate of destruction by , whilst the rate of destruction of total RO2 exceeded the production by the same rate, indicating that the net propagation rate of RO2 to HO2 may be substantially slower than assumed. If just 10 % of the RO2 radicals propagate to HO2 upon reaction with NO, the HO2 and RO2 budgets could be closed at high NO, but at low NO this lower RO2 to HO2 propagation rate revealed a missing RO2 sink that was similar in magnitude to the missing OH source. A detailed box model that incorporated the latest Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM3.3.1) reproduced the observed OH concentrations well but over-predicted the observed HO2 under low concentrations of NO (<1 ppbv) and under-predicted RO2 (both the complex RO2 fraction and other RO2 types which we classify as simple RO2) most significantly at the highest NO concentrations. The model also under-predicted the observed k(OH) consistently by across all NOx levels, highlighting that the good agreement for OH was fortuitous due to a cancellation of missing OH source and sink terms in its budget. Including heterogeneous loss of HO2 to aerosol surfaces did reduce the modelled HO2 concentrations in line with the observations but only at NO mixing ratios <0.3 ppbv. The inclusion of Cl atoms, formed from the photolysis of nitryl chloride, enhanced the modelled RO2 concentration on several mornings when the Cl atom concentration was calculated to exceed and could reconcile the modelled and measured RO2 concentrations at these times. However, on other mornings, when the Cl atom concentration was lower, large under-predictions in total RO2 remained. Furthermore, the inclusion of Cl atom chemistry did not enhance the modelled RO2 beyond the first few hours after sunrise and so was unable to resolve the modelled under-prediction in RO2 observed at other times of the day. Model scenarios, in which missing VOC reactivity was included as an additional reaction that converted OH to RO2, highlighted that the modelled OH, HO2 and RO2 concentrations were sensitive to the choice of RO2 product. The level of modelled to measured agreement for HO2 and RO2 (both complex and simple) could be improved if the missing OH reactivity formed a larger RO2 species that was able to undergo reaction with NO, followed by isomerisation reactions reforming other RO2 species, before eventually generating HO2. In this work an α-pinene-derived RO2 species was used as an example. In this simulation, consistent with the experimental budget analysis, the model underestimated the observed OH, indicating a missing OH source. The model uncertainty, with regards to the types of RO2 species present and the radicals they form upon reaction with NO (HO2 directly or another RO2 species), leads to over an order of magnitude less O3 production calculated from the predicted peroxy radicals than calculated from the observed peroxy radicals at the highest NO concentrations. This demonstrates the rate at which the larger RO2 species propagate to HO2, to another RO2 or indeed to OH needs to be understood to accurately simulate the rate of ozone production in environments such as Beijing, where large multifunctional VOCs are likely present.

- Article

(4850 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(804 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Owing to strict emission controls being implemented across China, a reduction in the levels of PM10, PM2.5 and SO2 has been observed in the country since 2013 (Huang et al., 2018). Similar reductions in these primary pollutants are echoed in other countries across the globe. In the United States this reduction in primary emissions is reflected in a reduction in peak O3 (He et al., 2020). In China, however, despite reductions in primary emissions, the concentration of ground-level ozone gradually increased between 2013–2017 (Huang et al., 2018). The highest peak ozone concentrations in China are observed in the Beijing area (T. Wang et al., 2017), where the highest O3 mixing ratio of 286 ppbv was recorded at a rural site 50 km north of the centre (Wang et al., 2006). During the Beijing Olympic Games, despite emission controls, hourly ozone mixing ratios between 160 to 180 ppbv were frequently observed in central Beijing (Wang et al., 2010). Ozone is a secondary pollutant, primarily formed in the troposphere via OH-initiated volatile organic compound (VOC) oxidation in the presence of NOx. O3 concentrations in megacities worldwide frequently exceed regulatory limits during the summer months, with elevated ozone concentrations shown to have negative impacts on human and crop health. The radical species, OH, HO2 and RO2, play a central role in the catalytic photochemical cycle which removes primary emissions and leads to ozone formation. The OH radical initiates the oxidation of VOCs, leading to the formation of peroxy radicals (HO2 and RO2). Peroxy radicals oxidise NO to NO2, which photolyses and generates ozone. Under high NOx conditions, OH preferentially reacts with NO2, and both peroxy radical production (via VOC oxidation) and, in turn, ozone production decrease. This non-linear relationship between ozone and NOx complicates efforts to reduce the ambient ozone levels as, in NOx-saturated environments, reductions in NOx can lead to increases in the rate of ozone production (e.g. Bigi and Harrison, 2010). Furthermore, a number of studies have highlighted that efforts to reduce PM have the potential to exacerbate O3 due to concomitant increases in HO2 caused by a reduction in the heterogeneous loss of HO2 to aerosol surfaces (Li et al., 2019), although there is continued debate on the magnitude of this effect from field studies (Tan et al., 2020). As well as the central role OH plays in photochemical ozone formation, OH promotes the formation of secondary aerosols (sulfate, nitrate and secondary organic aerosols, SOA), which have negative impacts on human health (Chen et al., 2013). Large, complex RO2 radicals are precursors to highly oxidised molecules (HOMs) (Ehn et al., 2014), which have also been shown to condense and contribute to SOA (Mohr et al., 2019). In China, the fraction of PM attributed to secondary aerosols is significant (between 44 %–71 %, Huang et al., 2014), and so understanding the oxidation chemistry which converts primary emissions to secondary aerosols is an ongoing challenge. There has been an increasing growth in photochemical oxidant studies conducted in China, where radical observations have been performed over the past decade, with the PKU and Juelich groups leading these efforts. The first radical observations took place in the summer of 2006, with observations made in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region (Hofzumahaus et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2012; PRIDE-PRD-2006) and also in suburban Beijing (Lu et al., 2013; CARE-Beijing 2006). These campaigns revealed a strong atmospheric oxidation capacity, with elevated levels of OH and HO2 in these regions, with OH concentrations up to and HO2 concentrations up to reported (Lu et al., 2012). Even during the wintertime, under low levels of solar radiation, concentrations of OH can reach in Beijing (Slater et al., 2020), which is similar to the OH concentrations observed in other urban centres in European cities during the summer months (Whalley et al., 2018). Similar to findings from radical observations and subsequent modelling activities in forested regions (Whalley et al., 2011), which are characterised by high VOC emissions and relatively low NOx concentrations, the observations and modelling studies in China in summer (Hofzumahaus et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2013) revealed that the high OH concentrations could only be explained if an additional source of OH, from recycling peroxy radicals to OH, was added to the model. An updated isoprene scheme (Peeters et al., 2009, 2014), which included isomerisation reactions of the isoprene-derived RO2 radicals, was unable to reconcile the OH observations, however. In a subsequent field study conducted in the PRD region (Tan et al., 2019), RO2 observations were made using the ROx laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) technique alongside OH, HO2 and OH reactivity, allowing an experimental budget analysis for OH, HO2, RO2 and ROx () to be performed. The analysis demonstrated a missing OH source of 4–6 ppbv h−1 and a missing RO2 sink that was similar in magnitude and, hence, supports the hypothesis of a missing mechanism that converts RO2 species to OH under low NO conditions. The authors calculated that the unknown RO2 to OH conversion that does not involve reaction with NO (and, therefore, does not lead to the formation of ozone) reduced ozone production by 30 ppbv d−1, demonstrating that knowledge of the branching ratio between the competitive reactions that RO2 radicals undergo (bimolecular reaction with NO or unimolecular isomerisation), as well as the overall VOC oxidation rate, is important when determining in situ ozone production.

In a recent campaign conducted at a rural site in the North China Plain (Tan et al., 2017), during periods in which NO mixing ratios were below 300 pptv, an additional OH recycling mechanism was again needed to reconcile the OH concentrations observed. The modelled RO2 concentrations were in good agreement with those observed under low NO concentrations typically experienced during the afternoon; however, the model under-predicted the RO2 concentrations by a factor of 3–5 at the higher NO mixing ratios (>1 ppbv) that were observed during the mornings. Additional sources of RO2 from the photolysis of ClNO2 and subsequent reactions of Cl atoms with VOCs, as well as RO2 from the missing reactivity determined, could explain ≈10 %–20 % of the model under-prediction but could not fully resolve the missing RO2 source of 2 ppbv h−1 under the high NO conditions. As a result, the model was found to under-predict the net in situ chemical ozone production by 20 ppbv d−1. In London, during the ClearfLo campaign (Whalley et al., 2018), under higher NO mixing ratios (>3 ppbv) a box model constrained to the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM3.2) was found to increasingly under-predict the RO2 concentrations observed with NOx, and, as a consequence, the rate of ozone production calculated from the modelled peroxy radical concentrations was up to an order of magnitude lower than the ozone production rate calculated from the observed peroxy radicals. The model was able to reproduce the observed levels of HO2 under the high NO concentrations but over-predicted HO2 concentrations when NO mixing ratios were below 1 ppbv, and modest under-predictions of OH were observed under low NO conditions, which demonstrated uncertainties in radical cycling at low NO. Conversely, in other urban studies, models were found to increasingly under-predict HO2 as NOx levels increased beyond ≈1 ppbv (Martinez et al., 2003; Ren et al., 2013; Brune et al., 2016), although in some of these earlier studies, the HO2 observations may have been influenced by an RO2 interference (Whalley et al., 2013). Understanding the cause of the model failure under different NO regimes in urban centres is critical to be able to accurately predict ozone production and to determine ozone abatement strategies that can be implemented to successfully reduce ozone levels. Measurements of OH, HO2 and RO2 as well as OH reactivity are necessary to fully explore a model's skill to capture the entire atmospheric oxidation cycle and to begin to identify mechanisms that can reconcile the concentration of all radical species.

The integrated Study of AIR Pollution PROcesses in Beijing (AIRPRO) project involved two intensive measurement periods that took place in central Beijing during the winter of 2016 and during the following summer of 2017 and was part of the larger Air Pollution and Human Health (APHH) programme. APHH had the overall aim of better understanding the sources, atmospheric transformations and health impacts of air pollutants in Beijing to improve air quality forecasting capabilities (Shi et al., 2019). In this paper the observations of OH, HO2, RO2 and OH reactivity from the summer period are compared to a detailed zero dimensional box model run with the latest Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM3.3.1), and an experimental budget analysis is performed on all radical species. The overall objective of this research was to test the model's ability to reproduce the radical concentrations and, through the budget analysis, investigate the balance between radical production and destruction rates. Following on from the results of earlier radical observation and modelling studies conducted in urban regions, this research will investigate if there are missing radical sources and sinks under different NO regimes and investigate new chemistry that may improve model predictions. We will assess how uncertainties in the model mechanism influence the rate of in situ ozone production in an environment with large and complex VOC emissions and under highly variable NOx concentrations.

2.1 Site description

The observations took place in central Beijing at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), which is part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The site was located between the third and fourth north ring roads in Beijing and was within 150 m of several busy roads. All instrumentation was located in close proximity within nine shipping containers that were placed on a grassed area surrounding a large (325 m) meteorological tower. Further details of the measurement site and an overview of all the instrumentation that was run during the campaign can be found in Shi et al. (2019).

2.2 FAGE instrumentation

The University of Leeds fluorescence assay by gas expansion (FAGE) instrument was deployed at the IAP site and made measurements of OH, HO2, RO2 radicals and OH reactivity (k(OH)). The instrumental set-up was analogous to that used during the ClearfLo project (see Whalley et al., 2016, for the k(OH) instrument description and Whalley et al., 2018, for the OH, HO2 and RO2 instrument details) and also the winter AIRPRO project (Slater et al., 2020) and so is only briefly overviewed here. Two detection cells, the HOx cell and the ROx LIF cell, were located on the roof of the Leeds FAGE shipping container at a sampling height of 3.5 m. The k(OH) instrument, which was housed inside the container, alongside all other FAGE instrument components (including the laser system), drew air from close by the radical detection cells via a 1/2 in. Teflon line. The HOx cell made sequential measurements of OH and then the sum of OH+HO2, by the addition of NO (Messer, 99.95 %), which titrated HO2 to OH for detection by laser-induced fluorescence (LIF). In the ROx LIF reactor, which is an 83 cm long, 6.4 cm internal diameter flow tube, in HOx mode, a flow of CO (10 % in N2) was added just beneath the sampling inlet, and this rapidly converted any ambient OH sampled to HO2. Within the ROx LIF FAGE cell, a continuous flow of NO (99.95 %) titrated ambient HO2, the converted OH and also a large percentage of complex RO2 radicals (see below) to OH for detection. In ROx mode, a total measurement was made by addition of a dilute flow of NO (500 ppmv in N2) alongside the CO, which promoted the conversion of all HO2 and RO2 radicals to OH; the OH formed was rapidly reconverted to HO2 by reaction with CO. Within the ROx LIF FAGE cell, the HO2 was titrated back to OH, by reaction with NO, for detection. Using the methodology outlined in Whalley et al. (2013), the sensitivity of both the HOx and ROx LIF FAGE cells towards HO2 and complex RO2 species was assessed before the instrument was deployed to Beijing by sampling isoprene-derived RO2; the sensitivity of the HOx cell towards other RO2 types such as those derived from ethene, methanol and propane has been previously conducted (Whalley et al., 2013) and compared well with model-predicted sensitivities. The sensitivity of the ROx LIF instrument has also been assessed previously towards a range of RO2 types deriving from methane, isoprene, ethene, toluene, butane and cyclohexane and, again, compared well with model-predicted sensitivities (Whalley et al., 2018). “Complex RO2” refers to any RO2 species (primarily those derived from alkene and aromatic hydrocarbons) that have the potential to decompose into OH in the presence of NO on the timescale of the FAGE residence time and, therefore, have the potential to act as an HO2 interference. The NO flow in the HOx cell was kept low to minimise the conversion efficiency of complex RO2 to OH, and the conversion efficiency was found to be <5 % when isoprene-derived RO2 radicals were sampled. In the ROx LIF FAGE cell, a higher NO flow was employed to promote the conversion of complex RO2 to OH, enabling 89 % of isoprene-derived RO2 radicals to be detected. From the relative sensitivities of the two cells to OH, HO2 and complex RO2, and by subtraction of complex RO2 from total RO2, the concentration of RO2 species that do not act as an HO2 interference (“simple RO2”) has been derived.

For the entirety of the campaign, the HOx cell was equipped with an inlet pre-injector (IPI; Woodward-Massey et al., 2020), which, by injection of propane into the ambient air stream directly above the HOx inlet, removes ambient OH and enables a background measurement from laser scatter, solar scatter and detector dark counts (and potentially any cell-generated OH) to be determined whilst the laser is tuned to the OH transition. The subtraction of this background signal from the ambient OH signal provides the OHCHEM measurement, which can be compared to the traditional OHWAVE measurement in which the background signal (from laser scatter, solar scatter and detector dark counts only) is determined by tuning the laser wavelength away from the OH transition. Differences between OHCHEM and OHWAVE can highlight the presence of an OH interference. During the summer AIRPRO campaign, once the known OH interference deriving from laser photolysis of ambient ozone and the subsequent reaction of photogenerated O(1D) atoms with ambient H2O (v) were accounted for (Woodward-Massey et al., 2020), the agreement between OHCHEM and OHWAVE was generally very good (see Fig. 14 in Woodward-Massey et al., 2020). However, on five afternoons when ozone was extremely elevated (>100 ppbv) and OH concentrations were high ( cm−3), OHWAVE was greater than OHCHEM (by up to 18 %), highlighting a small unknown interference under these very perturbed conditions. In all the model–measurement comparisons presented in Sect. 3, the interference-free OHCHEM measurement is used.

Both detection cells were calibrated every 3 d during the campaign by photolysis of a known concentration of H2O (v) at 185 nm with a Hg lamp in synthetic air (Messer, Air Grade Zero 2) within a turbulent flow tube, which generates an equal concentration of OH and HO2 (Whalley et al., 2018). The product of the photon flux at 185 nm (determined by N2O actinometry before and after the instrument was deployed to Beijing; Commane et al., 2010), [H2O] and irradiance time, was used to calculate [OH] and [HO2]. For calibration of RO2 concentrations, methane (Messer, Grade 5, 99.99 %) was added to the humidified air flow in sufficient quantity to completely convert OH to CH3O2. The median limit of detection (LOD) during the campaign was 6.1×105 molecule cm−3 for OH, 2.8×106 molecule cm−3 for HO2 and 7.2×106 molecule cm−3 for CH3O2 at a typical laser power of 11 mW for a 5 min data acquisition cycle (SNR=2). The field measurements of all species were recorded with 1 s time resolution, and the precision of the measurements was calculated using the standard errors in both the online and offline points. The accuracy of the measurements was ≈26 % (2σ) and is derived from uncertainties in the calibration, which derive largely from that of the chemical actinometer (Commane et al., 2010).

2.3 Experimental budget analysis

An experimental budget analysis has been conducted for OH, HO2, RO2 and total ROx following the approach outlined in Tan et al. (2019) and which relies only on field-measured quantities (concentrations and photolysis rates) and published chemical kinetic data and not on any model calculated concentrations. The rates of production and destruction of each radical species are calculated using Eqs. (1)–(8) below.

where jHONO and are the measured photolysis rates of HONO and O3 (forming O1D) respectively; f is the fraction of O1D radicals that react with H2O rather than are collisionally quenched to O(3P) (f=0.1 on average); and , , and are the yield of OH, HO2 and RO2 from, and rate coefficients for, individual ozone–alkene reactions taken from the MCM3.3.1 respectively. jHCHO_r is the measured HCHO photolysis rate that yields HO2 radicals, and khet is the first-order loss of HO2 to the measured aerosol surface area, calculated using Eq. (9):

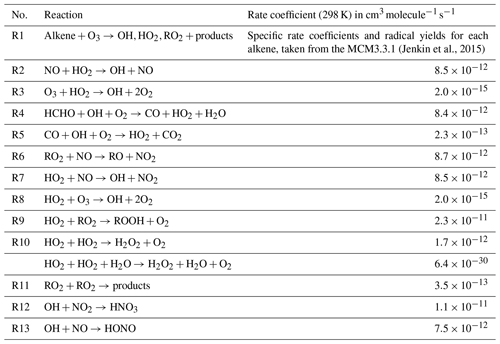

where ω is the mean molecular speed of HO2 (equal to 43 725 cm s−1 at 298 K), γ is the aerosol uptake coefficient (0.2 is used here as recommended by Jacob, 2000) and A is the measured aerosol surface area in cm2 cm−3. α is the fraction of RO2 radicals that upon reaction with NO propagate to HO2 rather than reform another RO2 radical; initially α=1 has been assumed. β is the fraction of RO2 radicals that upon reaction with NO form alkyl nitrates and is set to 0.05 as used by Tan et al. (2019) to represent an average alkyl nitrate yield for the various types of RO2 species likely present. All rate coefficients (k1–k13) used are listed in Table 1, and the concentrations of species used in the budget analysis are the concentrations that were observed during the campaign.

2.4 MCM3.3.1 box model description

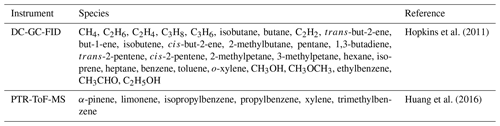

A zero-dimensional (box) model incorporating the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM3.3.1; Jenkin et al., 2015; http://mcm.leeds.ac.uk/MCM/home, last access: 1 February 2021) was used to predict the radical concentrations and OH reactivity for comparison with the observations. The model was constrained by measurements of NO, NO2, NO3, O3, CO, HCHO, HNO3, HONO, water vapour, temperature, pressure and individual VOC species measured by DC-GC-FID (dual-channel gas chromatography with flame ionisation) and PTR-ToF-MS (proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry). Table 2 lists the different VOC species measured. HCHO was measured using a recently developed LIF instrument with 1 s time resolution and LOD of 80 pptv (Cryer, 2016). HONO was measured by a long-path absorption photometer (LOPAP) and broadband cavity-enhanced absorption spectrophotometry (BBCEAS) and the HONO concentration as recommended in Crilley et al. (2019) are used here. Further details on all instrumentation deployed during the campaign are overviewed in Shi et al. (2019).

Table 2The species measured by DC-GC-FID and PTR-ToF-MS that have been used as constraints in the model.

The model was constrained with the measured photolysis frequencies j(O1D), j(NO2), and j(HONO), which were calculated from the measured wavelength-resolved actinic flux and published absorption cross sections and photodissociation quantum yields. For other species which photolyse at near-UV wavelengths (<360 nm), such as HCHO and CH3CHO, the photolysis rates were calculated by scaling to the ratio of clear-sky j(O1D) to observed j(O1D) to account for clouds. For species which photolyse further into the visible, the ratio of clear-sky j(NO2) to observed j(NO2) was used. The variation of the clear-sky photolysis rates (j) with solar zenith angle (χ) was calculated within the model using the following expression:

with the parameters l, m and n optimised for each photolysis frequency (see Table 2 in Saunders et al., 2003). The model inputs were updated every 15 min; the species that were measured more frequently were averaged to 15 min, whilst the measurements with lower time resolution were interpolated. To estimate how long model-generated intermediate species survive before being physically removed by processes such as deposition or ventilation, the model was left unconstrained to glyoxal, and the rate of physical loss was varied. The model was able to reproduce the observed glyoxal concentrations if a deposition velocity of 0.5 cm s−1 was used, combined with a ventilation term that increased with boundary layer depth. As the boundary layer gradually increased in the morning, the lifetime of glyoxal with respect to ventilation was ≈1 h, whilst at night the lifetime gradually increased to ≈5 h; this variable lifetime was applied to all model-generated species. As a further check on the physical loss rate imposed, the model was run unconstrained to HCHO using the same deposition rates and was found to reproduce the observed HCHO concentrations that were observed during the daytime but under-predicted the concentrations at night, potentially indicating that primary emissions of HCHO as well as secondary production contributed to the observed concentrations. In all the model scenarios presented in Sect. 3, the observed HCHO concentration is used. The model was run for the entirety of the campaign in overlapping 7 d segments. To allow all the unmeasured, model-generated intermediate species time to reach steady-state concentrations, the model was initialised with inputs from the first measurement day and spun up for 2 d before comparison to measurements of OH, HO2, RO2 and k(OH) was made. For comparison of the modelled RO2 to the observed total RO2, complex RO2 and simple RO2, the ROx LIF instrument sensitivity towards each RO2 species in the model was determined by running a model first under the ROx LIF reactor and then the ROx LIF FAGE cell conditions (NO concentrations and residence times) to determine the conversion efficiency of each modelled RO2 species to HO2.

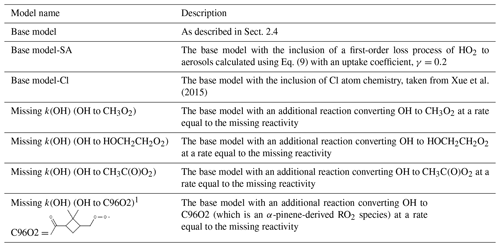

A series of model runs have been performed and are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3Different model scenarios that are discussed in Sect. 3.

1 Note that C96O2 is an α-pinene-derived RO2 that forms during the ozone-initiated oxidation of α-pinene. The additional production of C96O2 peroxy radicals in this model scenario was used to investigate the impact of an RO isomerisation mechanism on the modelled radical concentrations.

3.1 Overview of the chemistry and meteorology during the campaign

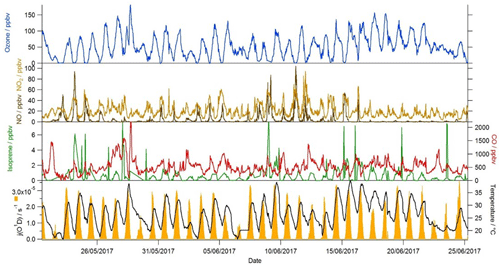

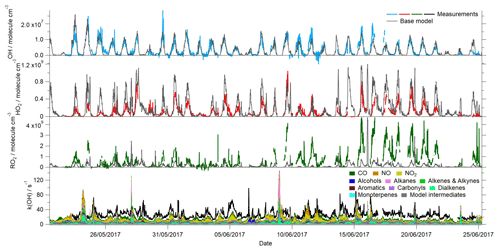

As part of the AIRPRO project, gas-phase, aerosol, and meteorological observations were made at the IAP site from 21 May to 26 June 2017. Typically clear skies and elevated temperatures prevailed, with rain on just a few days. Temperatures frequently exceeded 35 ∘C, whilst j(O1D) peaked at just over s−1 at noon (Fig. 1). The dominant wind direction reaching the site during the summer was from the south-west, and the measured hourly mean wind speed was 3.6 ms−1 (Shi et al., 2019). Despite the close proximity of the measurement site to the heavily trafficked Jingzang highway in Beijing, mixing ratios of NO, which were elevated during the morning hours, often dropped below 500 pptv during the afternoon. The daytime emissions of NOx that were recorded during the project displayed a rapid increase at 05:00 and then remained reasonably constant throughout the day, with a mean flux value of 4.6 , before dropping again at 17:00 (Squires et al., 2020). The rapid decrease in NO into the afternoon, therefore, was not driven by a change in emissions, but rather instead by the increasing boundary layer depth and also by the chemistry, as elevated levels of ozone observed in the afternoon effectively titrated NO to NO2 (Newland et al., 2020). Isoprene mixing ratios also peaked in the afternoon, often reaching a few parts per billion (ppbv), indicative of a biogenic source. The variation in NOx and VOC concentrations experienced at the site provides an opportunity to assess the skill of the MCM to capture the complex chemistry occurring over an extremely wide range of chemical regimes that encompasses both typical urban conditions (high NOx) as well as chemical conditions more akin to forested environments (low NO, high biogenic VOC (BVOC)). From 9 to 12 June, NO levels were elevated throughout the day, suggesting a local source, whilst from 17 June to the end of the measurement period, NO concentrations dropped, and so, as well as the strong diurnal trend observed in the NO concentration, these periods provide further opportunity to test the model's ability to predict radical concentrations as a function of NO by removing concomitant variables such as changing boundary layer depth and sunrise which occurred in unison with the morning increase in NO concentration.

3.2 Radical concentrations and OH reactivity

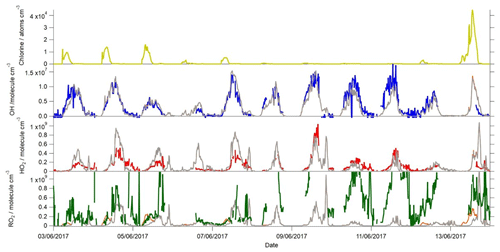

The concentrations of ROx () radicals were high during the campaign (Fig. 2), with OH concentrations frequently exceeding 1×107 molecule cm−3 and reaching up to 2.8×107 molecule cm−3 on 30 May. These OH levels are amongst the highest measured in an urban environment (Lu et al., 2019) and are comparable to the OH concentrations observed in the Pearl River Delta downwind of the southern Chinese megacity of Guangzhou, where OH concentrations reached 2.6×107 molecule cm−3 (Lu et al., 2012). HO2 concentrations peaked at 1×109 molecule cm−3 on 9 June, whilst the highest concentrations of total RO2 were observed during the latter half of the campaign, peaking at 5.5×109 molecule cm−3 on the afternoon of 15 June. RO2 measurements, alongside OH and HO2, were, until recently, relatively rare. OH and ROx were measured during the MEGAPOLI project in Paris (Michoud et al., 2012), where the average daytime maximum concentrations of ROx were 1.2×108 molecule cm−3, which is over an order of magnitude lower than the levels observed in Beijing. Since the development of the ROx LIF technique (Fuchs et al., 2008), RO2 observations are now reported by the Leeds, Juelich and PKU FAGE groups. RO2 concentrations observed in London in the summer reached up to 5.5×108 molecule cm−3 in air masses that had previously passed over central London (Whalley et al., 2018). In Wangdu, a town situated on the North China Plain, 170 km north-east of Beijing, summertime RO2 concentrations reached up to 1.5×109 molecule cm−3 (Tan et al., 2017), which, although lower than observed in central Beijing, are much higher than observed in the summertime in European cities, suggesting that there may be significant differences in the urban photochemistry occurring in China and Europe.

Figure 2Time series of the measured and modelled OH, HO2, total RO2 and OH reactivity during the campaign.

As well as the elevated daytime radical concentrations, concentrations of OH, HO2 and RO2 remained elevated above the instrumental LOD on most nights. The high night-time OH concentrations (ranging from the LOD up to 2×106 molecule cm−3) are comparable to the levels of OH observed at night in Yufa (a suburb of Beijing) and downwind of Guangzhou, where night-time OH concentrations ranged from 0.5–3×106 molecule cm−3 (Lu et al., 2014). The observations of OH from the earlier Chinese campaigns could be reconciled by a model if an additional ROx production process was included which recycled RO2 to OH via HO2. A weak positive correlation is observed between night-time OH and RO2 during AIRPRO, and the secondary peak in RO2 occurred when NO3 was observed to increase rapidly at ≈19:30, suggesting that nitrate chemistry was one source of radicals in the evening. Alkyl nitrates, formed from isoprene+NO3, were also enhanced at these times at this site (Reeves et al., 2019).

The OH reactivity, typical of urban environments, displayed an inverse relationship with boundary layer height and was highest during the nights when emissions were compressed into a lower boundary layer depth of ≈150 m. An average maximum of k(OH)≈37 s−1 was observed at 06:00, with OH reactivity reaching 89 s−1 on 15 June at 03:00. During the daytime, the OH reactivity dropped to a minimum of ≈22 s−1 on average at ≈15:00 when the boundary layer had increased to ≈1500 m. The magnitude of OH reactivity observed during AIRPRO is comparable to the OH reactivity observed at other urban sites in China in the summer (Lou et al., 2010; Fuchs et al., 2017) and also in Tokyo during the summer (Sadanaga et al., 2004; Chatani et al., 2009). In London, OH reactivity was approximately ≈7–10 s−1 lower than in central Beijing, with ≈15 s−1 observed during the day on average and an average maximum of ≈27 s−1 at 06:00 (Whalley et al., 2016). Lower OH reactivities are also reported from US urban sites in New York and Texas (Ren et al., 2003; Mao et al., 2010).

3.3 Experimental radical budget analysis

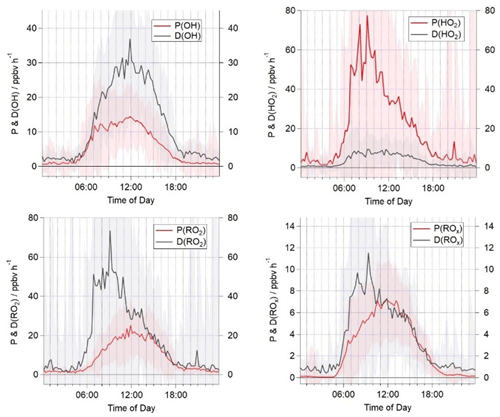

Owing to the relatively short lifetime of radicals, it can be assumed that their production rates and destruction rates are balanced. A comparison of the rates of production and destruction for each radical species can be used to help identify if all radical sources and sinks are accounted for and if the rates of propagation between radical species are fully understood. In London, the ratio of the OH production rate (Eq. 1) to OH destruction rate (Eq. 2) was generally close to 1 throughout the campaign, demonstrating consistency between the OH, HO2, k(OH), HONO and NO observations (Whalley et al., 2018). However, under low NO conditions (<0.5 ppbv), the rate of OH destruction exceeded the calculated production rate, indicating that Eq. 1 was missing a source term under these regimes (Whalley et al., 2018). A steady-state analysis of HO2 conducted for the London project, which balanced the HO2 production terms (Eq. 3) with the first- and second-order loss terms (Eq. 4), highlighted that closure between the production and destruction terms could only be reconciled if the rate of propagation of the observed RO2 radicals to HO2 was decreased substantially to just 15 %, demonstrating that the mechanism by which RO2 radicals propagate to other radical species may not be well understood (Whalley et al., 2018). As set out by Tan et al. (2019), analogous budget analyses can be performed for RO2 species (Eqs. 5 and 6) and for the entire ROx budget (Eqs. 7 and 8). Tan et al. (2019) found that the production and destruction terms for RO2 were balanced in the mornings in the PRD, when the measured OH reactivity was used to calculate the rate of RO2 production from VOC+OH reactions, but during the afternoon a missing RO2 sink (2–5 ppbv h−1) was evident. In the PRD study (Tan et al., 2019), the OH destruction rate exceeded the production rate by 4–6 ppbv h−1 in the afternoon, but, in contrast to London (Whalley et al., 2018), the HO2 budget was closed throughout the whole day. The total rates of ROx production and destruction were in good agreement in the PRD (Tan et al., 2019).

Figure 3Campaign median production and destruction rates for OH, HO2, total RO2 and ROx. The shaded areas represent the 1σ standard deviation of the data, representing the variability from day to day.

A comparison of the campaign median production and destruction rates for ROx, OH, HO2 and RO2 during AIRPRO is presented in Fig. 3. The total rates of ROx production and destruction are in good agreement throughout the day from ≈10:00. A night-time source of radicals of just under 1 ppbv h−1 is missing from the budget analysis, likely reflecting missing production from NO3+VOC reactions (night-time radical production is considered further in Sect. 3.5). From 06:00 to 10:00, the ROx destruction exceeds the production by up to 4 ppbv h−1, indicating a substantial, ≈50 %, missing primary ROx source at this time. Previous work has suggested that Cl-initiated VOC oxidation may be an important source of RO2 radicals in urban regions (Riedel et al., 2014; Bannan et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2017) but has not been included in the ROx or RO2 production rate calculations here. Nitryl chloride was measured for part of the AIRPRO campaign, and the impact of this on the modelled RO2 concentration is investigated in Sect. 3.4. The total ROx production and destruction rate is of the order of 6 ppbv h−1 at noon, which is slightly faster than in the PRD, where a median peak total radical production rate of ≈4 ppbv h−1 was calculated. The median OH destruction rate is ≈30 ppbv h−1 at noon and is roughly twice as fast the production rate at this time, highlighting a large missing source of OH radicals in the budget (≈15 ppbv h−1). Although a missing OH source was also reported in the PRD (Tan et al., 2019), the missing production rate is ≈3 times faster during AIRPRO. The known OH production rate during AIRPRO is dominated by the reaction of HO2 with NO (contributing ≈60 % during the day to P(OH) in Eq. 1). The median peak HO2 production of ≈60 ppbv h−1 is observed in the morning hours and greatly exceeded the known rate of HO2 destruction by ≈50 ppbv h−1. HO2 production is driven by the reaction of RO2 with NO, which accounts for 88 % of the total. The reaction of OH with CO and HCHO accounts for a further 9 %. The total HO2 production rate is approximately 4 times faster than that calculated for the PRD (Tan et al., 2019). The total rate of RO2 destruction mirrors the HO2 production, in that it is dominated by the reaction of RO2 radicals with NO. From sunrise to 14:00, the rate of RO2 destruction is faster than RO2 production by up to 50 ppbv h−1. After 14:00, the rates of RO2 production and destruction are in good agreement. This trend contrasts with the budget analysis presented from PRD (Tan et al., 2019), which highlighted a possible missing RO2 sink during the afternoon hours and budget closure in the morning hours.

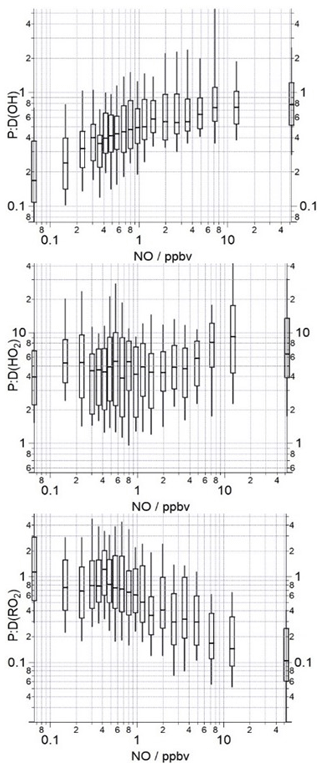

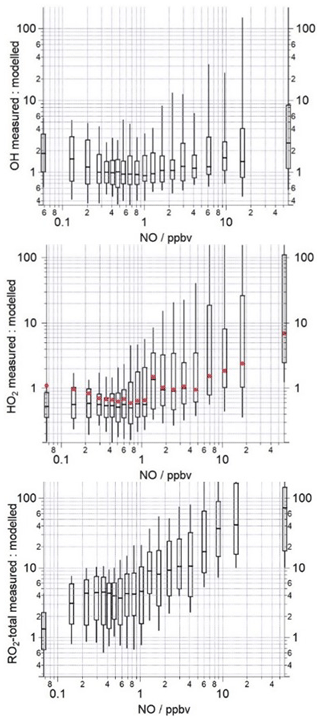

Figure 4The median ratio of the OH, HO2 and total RO2 production rates to destruction rates binned over the NO mixing ratio range encountered during the campaign on a logarithmic scale. The box and whiskers represent the 25th and 75th and the 5th and 95th confidence intervals. The number of data points in each of the NO bins is ≈80.

Binning the ratio of P(OH) to D(OH), P(HO2) to D(HO2) and P(RO2) to D(RO2) against the NO mixing ratio (Fig. 4) reveals that the RO2 budget is in good agreement at the lowest NO mixing ratios, but as NO mixing ratios increase the destruction of RO2 becomes faster than the production of RO2 by up to a factor of 10 at the highest NO bin. The trends in the RO2 and HO2 ratios are similar in the morning hours, albeit in opposite directions, and suggest that rather than there being a missing primary source of RO2 and missing sink for HO2 that happen to balance, instead, as found in London (Whalley et al., 2018), the net propagation rate of RO2 to HO2 may be substantially slower than the rate that has currently been used in this analysis. In London (Whalley et al., 2018), the modelled rate of production analysis revealed that only ≈50 % of the total RO2 species propagated to HO2 following reaction with NO, as a significant fraction of the alkoxy radicals formed (such as those generated during the oxidation of monoterpenes and long-chain alkanes) preferentially isomerised and reformed a more oxidised RO2 species in the presence of O2 instead. In the radical flux analysis using the MCM3.2 for London (Whalley et al., 2018), the propagation of alkyl- and acyl-RO2 species were combined, and so the interconversion of acyl-RO2 radicals (from the OH-initiated oxidation of aldehydic VOCs, photolysis of ketones and decomposition of PAN species) to alkyl-RO2 radicals following reaction with NO was not explicitly shown, but this interconversion of one RO2 species to another would serve to reduce the fraction of RO2 radicals that propagate to HO2 further. Thus far for AIRPRO, the experimental budget analysis has assumed that 95 % of the measured RO2 species, upon reaction with NO, produce HO2. If, however, a large fraction of the total RO2 measured derive from long-chain alkanes, monoterpenes or acyl-RO2 species, the budget analysis will overestimate HO2 production and also the net RO2 destruction, as the reaction of these peroxy radicals with NO effectively converts one RO2 species to another RO2 species, and so the reaction with NO will be neutral in terms of RO2 production and destruction. Taking α=0.1 leads to a good agreement between the production and destruction rates of HO2 over the whole day and the observed range of NO. The production and destruction rates of RO2 agree under high NO conditions, but at NO mixing ratios <5 ppbv the production of RO2 exceeds the destruction, highlighting (if this α value is correct) that there is a missing RO2 sink at the lower NO concentrations. Tan et al. (2019) also report a missing RO2 sink under low NO conditions during PRD and suggested that autoxidation of RO2 species could account for this missing sink and may also possibly act as the missing source of OH identified under the low NO conditions. An additional first-order reaction that converts RO2 to OH at a rate of 0.1 s−1 brings the P:D(OH) and P:D(RO2) ratios close to 1 at all NO mixing ratios >0.3 ppbv, but at low NO mixing ratios (0.1–0.3 ppbv range) an even slower rate of conversion is required, highlighting, as one might expect, that the overall rate of RO2 isomerisation is variable and likely depends on the specific RO2 species present at a particular time or location. In the PRD study (Tan et al., 2019), the HO2 budget was closed when α=0.95 was used, suggesting that acyl peroxy radicals and those derived from long-chain alkanes and monoterpenes only made up a very small fraction of the total RO2 concentration.

Although revealing, this type of experimental budget analysis coupled with the radical observations is unable to differentiate between different RO2 types, and so assumptions have to be made on the fraction of the total RO2 that propagate to HO2. In the following section, a box model constrained to the latest MCM scheme (MCM3.3.1) is used to predict the radical concentrations. The MCM is a near-explicit model and, as such, treats the production, propagation and destruction of each RO2 species present discretely and so can provide an insight into the rate at which different RO2 species convert to HO2 or to other RO2 species (or, indeed to OH) and the impact this propagation has on NO to NO2 conversion and, hence, O3 production.

3.4 MCM modelled radical predictions and comparison with observations

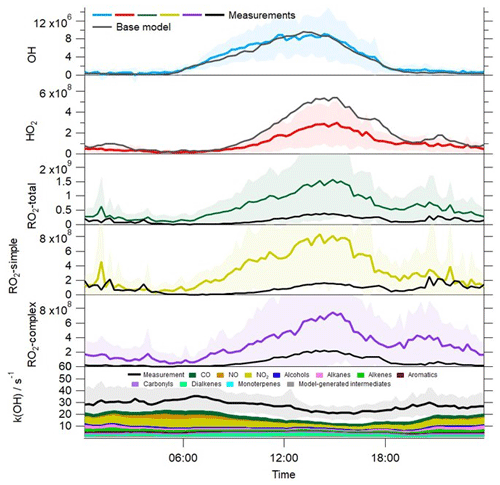

The time series of the model-predicted radical concentrations and a breakdown of the modelled OH reactivity from the base MCM model are overlaid with the observations in Fig. 2. The average diurnal profiles of the measured and modelled radical and k(OH) profiles are also provided in Fig. 5. In contrast to the experimental budget analysis, the model-predicted OH is in excellent agreement with the observed OH throughout the campaign. This same model overestimates HO2, however, particularly during the daytime but also during the evening when a small secondary peak in HO2 is predicted but not observed. An exception to this trend occurs between 9–12 June when elevated levels of NO were measured at the site during the day, and on these days, the agreement between the observed HO2 and the model is better. The over-prediction of HO2 primarily occurs under the lower NO conditions that were typically observed during the afternoon hours; the skill of the model to predict the radical concentrations as a function of NO is discussed further below. The model underestimates total RO2 throughout the measurement period, although the level of disagreement (in terms of absolute concentration) is most severe (15–22 June) when NO concentrations were at their lowest. During this period, the average NO mixing ratio was ≈0.4 ppbv during the afternoon hours, whilst the average NO mixing ratio for the entirety of the campaign was ≈0.75 ppbv during the afternoons (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The average peak NO mixing ratio observed in the morning (1–22 June) was just over 6 ppbv, whilst the average peak NO mixing ratio for the entirety of the campaign was close to 16 ppbv. During this period, the observed RO2 concentrations were most elevated relative to other times during the campaign; however, the model does not predict a similar increase in RO2 concentrations during this period relative to other times in the campaign. OH reactivity is underestimated by the model, on average by ≈10 s−1. However, between 15–22 June the average missing OH reactivity increases to ≈13 s−1. The model underestimation of OH reactivity may, in part, contribute to the model underestimation of RO2 as the model is evidently underestimating the rate of OH+VOC reactions which form RO2. Including an additional reaction between OH and VOC to account for the missing reactivity in the model and the impact this has on the modelled radical concentrations is investigated in Sect. 3.6. Although the model is able to capture the observed OH concentrations reasonably well, the model's failure to reproduce the observed HO2 and RO2 (and in the base model, the OH reactivity) indicates the model is either missing or misrepresenting some key reactions. Furthermore, the discrepancy between the model-predicted OH and OH budget analysis which highlighted a missing OH source, suggests that the over-prediction of HO2 is masking a missing OH source in the MCM model.

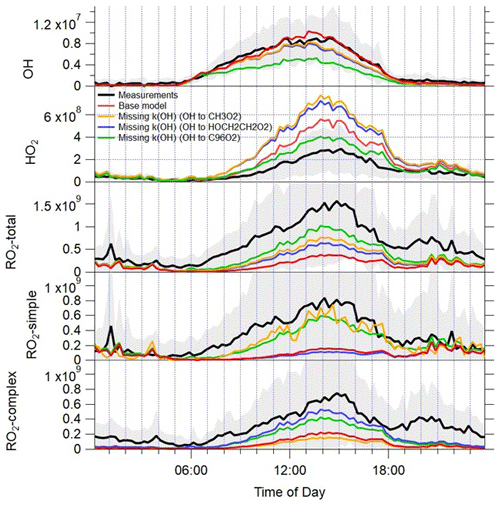

Figure 5Average profiles for the observed OH, HO2, total RO2, partially speciated RO2 (in molecule cm−3) and OH reactivity at 15 min intervals over 24 h. The error bars represent the 1σ standard deviation of the measurements, representing the variability in the measurements from day to day. The average diurnal profiles for OH, HO2, total RO2, partially speciated RO2 and OH reactivity from the base model are overlaid.

Figure 6The median ratio (−) of the measured to modelled OH, HO2 and total RO2 binned over the NO mixing ratio range encountered during the campaign on a logarithmic scale. The box and whiskers represent the 25th and 75th and the 5th and 95th confidence intervals. The red circles in the middle panel display the measured to modelled HO2 ratio when the model includes a heterogeneous loss of HO2 to aerosols calculated using Eq. (9). The number of data points in each of the NO bins is ≈80.

Qualitatively, the model overestimation of HO2 and underestimation of RO2 is consistent with the budget analysis, which identified a missing RO2 production term and missing HO2 destruction term which could be reconciled, in part, by slowing the rate at which RO2 propagates to HO2. However, when the HO2 measured to modelled ratio is binned against NO, differences between the model and budget analyses become apparent (Fig. 6). The model over-predicts the observed HO2 concentrations at the lowest NO mixing ratios experienced (0.1–1 ppbv); this over-prediction can be reconciled (under the very lowest NO conditions, <0.3 ppbv) when a loss of HO2 to aerosols (calculated using Eq. 9, with an uptake coefficient of 0.2) is included in the model. This demonstrates that a reduction in aerosol surface area has the potential to enhance HO2 concentrations and thereby increase photochemical ozone formation but only under very low NO conditions. As there was little to no change in the modelled HO2 concentration upon inclusion of an heterogeneous loss term under the higher NO conditions, efforts to reduce anthropogenic PM when NO is present (which is highly likely to be the case) would not be expected to lead to an increase in HO2 and, in turn, O3, as was suggested from earlier modelling studies (Li et al., 2019). Between 1–5 ppbv NO, the model is able to reproduce the observed HO2 well (between 9–12 June, the daytime NO concentrations fell within this intermediate NO range, hence the good agreement between the model and observations on these days). In contrast with the budget analysis, the model under-predicts HO2 beyond 5 ppbv NO by up to a factor of 10 at the highest NO experienced (see the 52 ppbv NO bin, Fig. 6, which includes NO mixing ratios up to 104 ppbv). The model under-predicts the observed RO2 over the whole NO range, and, consistent with the RO2 budget analysis, the under-prediction (in terms of %) is greatest at the highest NO concentrations experienced during the morning hours. The model under-predicts the observed RO2 by a factor of ≈70 in the highest NO mixing ratio bin range, whereas the destruction rate of RO2 exceeded the production rate by a factor of ≈10 in the budget analysis. This large under-prediction of RO2 by the model under the highest NO concentrations is most likely driving the differences noted between the P to D(HO2) and the measured to modelled (HO2) ratios at NO mixing ratios >5 ppbv. Previous radical studies made at urban sites which were influenced by a range of NOx concentrations have demonstrated that the level of agreement between model predictions and the observations tends to vary with the level of NO: models have a tendency to under-predict the observed OH concentrations at NO mixing ratios below 1 ppbv (Lu et al., 2012, 2013; Tan et al., 2017; Whalley et al., 2018), and RO2 concentrations are increasingly under-predicted as NO concentrations rise (Tan et al., 2017; Whalley et al., 2018; Slater et al., 2020).

Figure 7Time series of the measured and modelled OH, HO2 and total RO2 during the campaign when ClNO2 was also measured. The Cl atom concentration calculated to be present is shown in the top panel. The measured OH concentrations are represented by the blue line, HO2 by the red line and total RO2 by the green line. The base model scenario is shown in grey, whilst the base model with Cl atom chemistry included (Xue et al., 2015) is shown in orange (only evident in the RO2 panel).

Cl atoms, formed from the photolysis of nitryl chloride (ClNO2), have been shown to act as a source of RO2 (Riedel et al., 2014; Bannan et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2017) and have also been investigated here to see if Cl chemistry can resolve the modelled RO2 under-prediction under the elevated NO concentrations which were typically observed during the mornings. ClNO2 was measured for part of the campaign (Zhou et al., 2018) and reached up to 1.44 ppbv during the night on 12–13 June. The Cl atom concentration exceeded 4×104 atoms cm−3 during the morning of 13 June and exceeded 1×104 atoms cm−3 on several other mornings (Fig. 7). The Cl atom concentration was calculated from the concentration of ClNO2, its photolysis rate to yield Cl (determined from the observed actinic flux and published absorption cross section of ClNO2) and the VOC loading. During these times, the modelled RO2 concentrations increased, relative to the concentration in the base model, by up to 2.5×108 molecule cm−3, which represents close to a 100 % increase in the modelled RO2 at these times. On several mornings (4, 5, 7 and 13 June) this increase in RO2 brought the model and measured RO2 into close agreement. The production rate of RO2 from Cl-initiated VOC oxidation on these mornings would serve to enhance P(ROx) by up to 2.1 ppbv h−1. However, on several nights, only low concentrations of ClNO2 were measured, and only very low concentrations of Cl atoms were calculated to be present upon sunrise, and so, on these days, only modest enhancements (1–2×107 molecule cm−3) in RO2 concentrations were predicted by the model, and the large under-prediction in the RO2 concentration on these mornings remained, which may indicate that there are other, overlooked, primary ROx sources in the experimental budget calculation besides missing Cl+VOC reactions. The Cl atom concentration dropped off rapidly during the mornings with just ≈100 atoms cm−3 present by noon on most days and so was unable to reconcile the magnitude of the RO2 underestimation observed throughout the day.

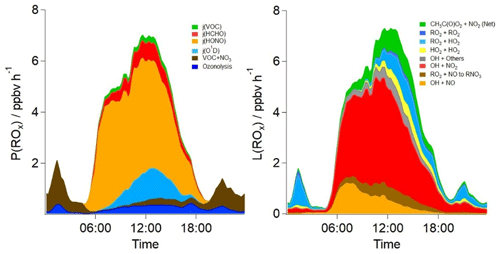

3.5 Rate of production and rate of destruction analysis

A rate of production and rate of destruction analysis on model OH, HO2 and RO2 species (Fig. 8) highlights the main radical sources and sinks in the base model. Consistent with earlier studies of radicals in urban locations, the photolysis of HONO is the dominant primary source of radicals during the daytime, accounting for ≈64 % of the primary radical production on average during the day (05:00–19:30) throughout the campaign. The photolysis of O3 and subsequent reaction of O(1D) with H2O vapour accounts for ≈9 % of primary production during the day, whilst the photolysis of HCHO and other photo-labile VOCs accounts for ≈11 % of the radical production. Ozonolysis and nitrate radical (NO3) reactions account for 9 % and 7 % of the total radical production during the day, respectively. At night, both ozonolysis (≈18 %) and nitrate radical reactions (≈82 %) are the source of radicals. The primary source of radicals from VOC+NO3 reactions is ≈1 ppbv h−1 during the night, which is sufficient to close the ROx experimental budget (Fig. 3).

Figure 8The average diurnal rates of primary production and termination for ROx radicals in parts per billion per hour (ppbv h−1) in the base model scenario. CH3C(O)O2+NO2 (Net) represents the net rate (forward minus backward) for all species.

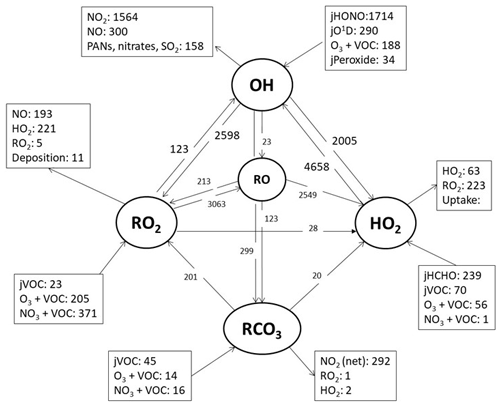

Figure 9A model reaction flux analysis, showing the mean rate of reaction for formation, propagation and termination of radicals (pptv h−1) (day and night) during the whole campaign.

Figure 9 highlights the rates of propagation in the model which transform OH to HO2 and RO2, RO2 to HO2 and HO2 back to OH. The rate of propagation is rapid, and the secondary source of OH from HO2+NO is more than twice as large as the primary production of OH from HONO photolysis. Approximately one-third of the OH reacts with CO, O3 or HCHO to form HO2, just over one-third reacts with VOCs to form RO2 and just under one-third is lost by reaction with NO2 forming nitric acid. In contrast to London (Whalley et al., 2018), the majority of RO2 formed during AIRPRO propagates to HO2, and subsequently the majority of HO2 propagates back to OH. From the model radical flux analysis, which takes into consideration the different types of RO2 species present, a value of α=0.87 is derived (where α=1 minus the rate at which RO forms RO2 or RC(O)O2 divided by the rate of RO conversion to HO2). Note that this fraction does not consider RO2 and RC(O)O2 termination reactions. In London, the model-derived α was ≈0.5, reflecting the presence of long-chain alkane-derived RO2 species from diesel emissions and monoterpenes. In Beijing, measurement of such long-chain VOC species could not be attempted, but these could have been present. A lumped monoterpene signal was measured by PTR-ToF-MS and is included in the model, split equally between α-pinene and limonene. The base model, on which the radical flux analysis was performed, under-predicts OH reactivity and so is likely missing RO2 species from additional OH+VOC reactions, which, depending on the RO2 type, may serve to reduce α.

3.6 OH reactivity and missing OH reactivity

NO2 was the single biggest contributor to the OH reactivity in Beijing, with a campaign average contribution of 18.6 % (Fig. 5). This is similar to the NO2 contribution to OH reactivity observed in London (Whalley et al., 2016). NO contributed just 1.3 % to the total reactivity in Beijing, compared to a 4.2 % contribution in London (Whalley et al., 2016). In London, measured carbonyl species accounted for close to 20 % of the OH reactivity budget, largely due to the high concentrations of HCHO (Whalley et al., 2016). In contrast, in Beijing, carbonyls accounted for just 3.8 % of the measured k(OH). Alkenes and dialkenes were more prevalent in Beijing than in London, and the dialkene group of VOCs (dominated by isoprene) accounted for 10.5 % of the OH reactivity in Beijing compared to 1.8 % in London (Whalley et al., 2016). Owing to the faster physical loss of secondary species in Beijing by ventilation compared to London (see Sect. 2), the contribution that model-generated intermediate species made to the observed OH reactivity was 2.7 % in Beijing vs. 23.8 % in London (Whalley et al., 2016). In contrast to Beijing, where approximately 30 % of the measured reactivity remains unaccounted for, in London, the OH reactivity budget was largely closed (Whalley et al., 2016). In Beijing during the measurement period when the missing OH reactivity reached on average 13 s−1 (15–22 June), isoprene concentrations were elevated relative to earlier in the campaign (Fig. 1). Overall, much higher concentrations of isoprene were observed in Beijing than in London (Whalley et al., 2016), and so this may indicate that other biogenic species that were not measured, along with their oxidation products, may account for some of the missing OH reactivity in Beijing.

Figure 10Average diel profiles for the observed OH, HO2, total RO2 and partially speciated RO2 (black lines) at 15 min intervals over 24 h. The error bars represent the 1σ standard deviation of the measurements. The average OH, HO2, total RO2 and partially speciated RO2 model profiles when the missing reactivity observed at a given time is accounted for by different OH to RO2 reactions are overlaid (yellow, blue and green lines); the base model predictions are in red. See text for details.

A series of model simulations have been performed, whereby an additional OH to RO2 reaction has been included to account for the missing reactivity at a given time (Fig. 10); the RO2 formed has been varied to investigate the influence of different RO2 types on the modelled radical concentrations. When OH converts to methyl peroxy radicals, the modelled RO2 concentration increases by close to a factor of 2 on average, but just over a factor-of-2 under-prediction of the observed RO2 radicals remains. Unsurprisingly, it is the modelled fraction of RO2 radicals that do not act as an HO2 interference (simple RO2) that increase in this scenario, and the model now only underestimates this class of RO2 species by a factor of 1.45, whilst complex RO2 is still underestimated by a factor of 6.2. When OH converts to HOCH2CH2O2 (an RO2 species that does act as an HO2 interference, formed from the reaction of OH with ethene), the modelled complex RO2 fraction increases, and the model underestimation of complex RO2 is reduced to a factor of 1.8 on average, with the largest under-predictions observed during the evening hours. In both these model simulations, the modelled over-prediction of HO2 increases from the base model scenario as CH3O2 and HOCH2CH2O2 both rapidly propagate to HO2. The modelled OH concentration displays a modest decrease with the additional OH sink; however, this is largely compensated for by the increase in modelled HO2, which enhances the secondary source of OH from HO2+NO, and so, overall, the modelled OH concentration is largely buffered by the inclusion of missing OH reactivity in the form of additional methane (leading to CH3O2) or ethene (leading to HOCH2CH2O2).

Model simulations (not shown) which include an additional source of CH3C(O)O2, for example, from additional CH3CHO+OH reactions, do predict substantially less HO2 (and can reconcile the observed HO2 to with 25 %), but modelled RO2 concentrations do not increase as a large fraction of the acyl-RO2 radicals react with NO2 to form PAN and are, therefore, lost. These missing reactivity model simulations and measurement comparisons suggest that the missing RO2 may be a species, which, upon reaction with NO, converts from one RO2 species to another and, therefore, competes with RO2 to HO2 propagation rather than a RO2 radical, which leads to RO2 termination. This suggests that the overall lifetime of RO2 radicals is longer than currently estimated and that multiple conversions of one RO2 species to another may be occurring to sustain the high concentrations observed. As identified in London, larger, more complex VOC species such as monoterpenes or long-chain alkanes deriving from diesel emissions do undergo multiple RO2 to RO2 conversions in the presence of NO as the alkoxy radical formed preferentially undergoes isomerisation rather than an external H atom abstraction by O2. If an additional reaction which converts OH to an RO2 species formed during the oxidation of α-pinene, and which undergoes four reactions with NO before eventually forming HO2, is added to the model at a rate sufficient to reconcile the missing OH reactivity, the model predicts significantly more total RO2 and now only modestly under-predicts the observed RO2 concentrations (by a factor of 1.8). The modelled radical concentrations predicted from the “missing k(OH) (OH to C96O2)” scenario are overlaid with the radical observations and modelled radicals from the base model scenario in Fig. S2. The additional VOC reactivity which produces RO2 radicals that isomerise after reaction with NO is able to increase the modelled total RO2 concentration, both under the lower NO conditions experienced between 15–22 June and on the higher NO days (9–12 June), indicating that NO is still at sufficient concentrations to dominate the fate of RO2 between 15–22 June, despite NO concentrations being lower. The median measured to modelled (missing k(OH) (OH to C96O2)) ratio vs. NO (Fig. S3) highlights that the inclusion of alkoxy isomerisation following the RO2+NO reaction increases the modelled RO2 across the entire NO range but, considering the log scale, has the biggest impact on the ratio (from the measured to modelled (base) ratio) at the highest NO concentration. Both the simple and complex RO2 species are enhanced, as the first three generations of RO2 species formed would be detected during the ROx mode in the ROx LIF instrument and, hence, contribute to simple RO2. The final RO2 species formed, that does propagate to HO2 via RO upon reaction with NO, would be detected during the HOx mode in the ROx LIF instrument and, as such, contributes to the complex RO2 fraction. In this scenario, the HO2 concentration is now only modestly overestimated by a factor of 1.4. The ROx LIF instrument relies on the conversion of RO2 species to HO2 (and ultimately to OH) for detection, so one might expect the instrument to be insensitive to RO2 species that do not directly propagate to RO then to HO2 upon reaction with NO. However, given the ROx LIF flow tube conditions (NO concentration of 4×1013 molecule cm−3 and residence time of just under 1 s), RO2 species that require several reactions with NO before HO2 is produced should still be detected. These types of RO2 species that require more than one reaction with NO before HO2 forms may be generated via the additional VOC+OH reactions identified as missing OH reactivity (as presented here). They may also be present due to a missing primary source of RO2 such as decomposition of a complex PAN species, VOC photolysis, a Cl atom+VOC reaction or an alkene ozonolysis product. The experimental peroxy radical budget analysis highlighted that budget closure could only be achieved if α was reduced to 0.1, which suggests that the model breakdown of peroxy radical species present (e.g. the fraction of acyl-RO2, long- vs. short-chained alkyl-RO2 species) may be incomplete. In the scenario in which OH converts to an α-pinene-derived RO2 species, consistent with the experimental budget analysis, the model under-predicts the observed OH by a factor of 1.8, revealing that there is a missing source of OH under the low NO conditions in Beijing that was previously masked by the model over-prediction of HO2.

3.7 Impact on ozone production

Previous work, for example, by Tan et al. (2017), suggested that the addition of a primary RO2 source could help reconcile the model under-prediction of RO2. However, as demonstrated in Sect. 3.6, the identity of the primary RO2 is important, and in Beijing a complex RO2 species that has a large enough carbon skeleton such that the RO radical formed upon reaction with NO preferentially isomerises to another RO2 (and undergoes multiple RO2 to RO2 conversions before eventually forming HO2) is needed to reconcile both the observed RO2 and HO2 concentrations. These types of RO2 species may also preferentially isomerise rather than undergo the bimolecular reactions with NO if NO concentrations are low enough. For example, laboratory studies have shown that the monoterpenes, following an initial attack by ozone or OH, form highly oxidised RO2 radicals within a few seconds via repeated H shift from C−H to an bond and subsequent O2 additions (Ehn et al., 2014; Jokinen et al., 2014; Berndt et al., 2016). Recently, autoxidation has also been shown to occur during the oxidation of aromatic VOCs too (S. N. Wang et al., 2017). Autoxidation reactions may generate OH directly from RO2 and, therefore, may also resolve the missing OH source reported under low NO conditions (here and in the literature). These types of autoxidation reactions lead to the generation of HOMs, which have also been shown to condense and contribute to SOA (Mohr et al., 2019). Mass spectrometric signals relating to these highly oxidised RO2 species were observed during the AIRPRO campaign (Brean et al., 2019; Mehra et al., 2021) suggesting that autoxidation was occurring at the Beijing site. Unimolecular H atom shifts are represented within the MCM3.3.1 for isoprene oxidation. Autoxidation reactions for other RO2 radicals are currently not included within the MCM3.3.1, although improved representation of RO2 radical chemistry is a focus for the next generation of explicit detailed chemical mechanisms (Jenkin et al., 2019). In addition to missing unimolecular RO2 reactions, the model may be missing other RO2 reaction pathways, for example, RO2 accretion reactions, as identified by Berndt et al. (2018). Although it is difficult to fully assess how competitive these RO2+RO2 reactions may be compared to RO2+NO reactions from the total RO2 observations made (the concentration of each individual RO2 would be needed), the inclusion of accretion reactions in the MCM would serve to reduce the modelled RO2 concentration under low NOx conditions as the reaction represents an overall ROx sink. This suggests that the missing RO2 source identified here may be even larger under the lower NO conditions.

The model measurement comparisons above suggest that our understanding of the rate at which the larger RO2 species propagate to HO2 (or to OH directly) and the possible reactions they undergo (which have not undergone substantial laboratory study) is far from complete and highlights that RO2 chemistry warrants further study. One important finding, however, is that the underestimation of the observed RO2 may be caused by missing reactions that compete with the RO2+NO reactions that form HO2. These competing reactions are effectively slowing the rate at which RO2 species convert to HO2, but if, as suggested here, these reactions are RO2+NO reactions that reform another RO2 radical, they will still be relevant in terms of ozone production. Under low NO conditions there is emerging evidence that unimolecular isomerisation reactions occur for a range of RO2 radicals (Ehn et al., 2014; Jokinen et al., 2014; Berndt et al., 2016; S. N. Wang et al., 2017) as well as RO2 accretion reactions (Berndt et al., 2018). These reactions will effectively remove RO2 radicals without conversion of NO to NO2 and so also have implications for modelling in situ O3 production, if models rely only on the rate of VOC oxidation when investigating O3 production.

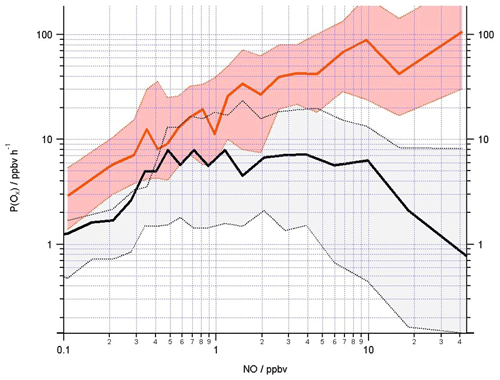

By approximating the rate of ozone production to the rate of NO2 production from the reaction of NO with HO2 and RO2 radicals, urban radical measurements can be used to estimate chemical ozone formation (Kanaya et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2013; Brune et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2017; Whalley et al., 2018).

Losses of Ox (L(Ox)) include chemical losses such as the reaction of NO2 with OH, net PAN formation, the fraction of O(1D) (formed by the photolysis of O3) that react with H2O and the reaction of O3 with OH and HO2. Physical loss processes, such as O3 deposition and ventilation out of the model box (see Sect. 2.4), will also contribute to L(Ox). Physical processes such as advection of O3 into the model box would also need to be considered in the model to make a direct comparison to the observed O3 concentrations.

Figure 11Mean Ox production (ppbv h−1) calculated from observed (red line) and modelled (black line) ROx concentrations using Eq. (11) binned over the NO mixing ratio range encountered during the campaign on a logarithmic scale. The shading represents the 25th and 75th percentile confidence limits. The number of data points in each of the NO bins is ≈80.

Considering the chemical production of Ox (Eq. 11), recent studies, in which OH, HO2 and RO2 observations (via ROx LIF) were made, demonstrated that models may under-predict ozone production at high NO due to an underestimation of the RO2 radical concentrations at high NO concentrations (Tan et al., 2017; Whalley et al., 2018). Figure 11 displays the mean ozone production calculated from the radical observations (red line) as a function of NO, and, consistent with the earlier ozone production calculations from the Wangdu (Tan et al., 2017) and London (Whalley et al., 2018) studies, the in situ ozone production calculated from the modelled OH and peroxy radicals (black line) is lower than from the observed radicals, most significantly at the higher NO concentrations. To accurately simulate ozone production and to understand how emission reduction policies may impact ozone levels, it is essential that the model accurately reflects the types of RO2 species present and how fast they propagate to another RO2 species or to HO2 or to OH.

Measurement and model comparisons of OH, HO2, complex RO2, simple RO2 and total RO2 in Beijing have displayed varying levels of agreement as a function of NOx. Under low NO conditions, consistent with previous studies in low NOx but high VOC environments, a missing OH source is evident. Radical budget analysis has demonstrated that this missing OH source could be resolved if unimolecular reactions of RO2 radicals generate OH directly. Under the low NO conditions (<1 ppbv), the MCM over-predicted HO2, although this over-prediction could be resolved at very low NO mixing ratios (<0.3 ppbv) by including a heterogeneous loss term to aerosol surfaces. This highlights that a reduction in aerosol surface area has the potential to enhance HO2 concentrations and thereby increase photochemical ozone formation but only under very low NO conditions. The model under-predicted RO2, most severely under high NO conditions (>1 ppbv). Although Cl atoms could increase the concentration of RO2, this enhancement was limited to times when the Cl atom concentration was elevated and could not resolve the RO2 under-prediction observed at all times. In the presence of NO, the model overestimates the rate at which RO2 propagates to HO2, and we hypothesise that larger RO2 species likely undergo multiple bimolecular reactions with NO, followed by isomerisation of the RO radical to another RO2 species, before a HO2 radical forms. By this process, the lifetime and the concentration of total RO2 radicals are extended. The ozone production efficiency of large, complex VOCs from which these RO2 species are formed may be greater than currently appreciated, and so further efforts to understand the rate at which the larger RO2 species propagate to HO2 (or to OH directly) and all the possible reactions they undergo are necessary to accurately model ozone levels in urban centres such as Beijing and to fully understand how emission controls will impact ozone.

Data presented in this study are available from the author upon request (l.k.whalley@leeds.ac.uk).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-2125-2021-supplement.

LKW, EJS, RWM, CY and DEH carried out the measurements. LKW and EJS developed the model and performed the calculations. JDL, FS, JRH, RED, MS, JFH, ACL, AM, SDW, AB, TJB, HC, BO, RLJ, LRC, LJK, WJB, TV, SK, SG, YS, WX, SY, LR, WJFA, CNH, XW and PF provided logistical support and supporting data to constrain the model. LKW prepared the manuscript, with contributions from all the co-authors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “In-depth study of air pollution sources and processes within Beijing and its surrounding region (APHH-Beijing) (ACP/AMT inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

Eloise Slater, Robert Woodward-Massey, Freya Squires and Archit Mehra acknowledge NERC SPHERES PhD studentships. We would like to thank Likun Xue and co-authors for providing the chlorine chemistry module used in the MCM. We acknowledge the support from Zifa Wang and Jie Li from the Institute of Applied Physics (IAP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, for hosting the APHH-Beijing campaign. We thank Liangfang Wei, Hong Ren, Qiaorong Xie, Wanyu Zhao, Linjie Li, Ping Li, Shengjie Hou and Qingqing Wang from IAP, Kebin He and Xiaoting Cheng from Tsinghua University and James Allan from the University of Manchester for providing logistic and scientific support for the field campaigns. We would also like to thank other participants in the APHH field campaign.

This research has been supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (grant no. NE/N006895/1) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 41571130031).

This paper was edited by Ronald Cohen and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bannan, T. J., Booth, A. M., Bacak, A., Muller, J. B. A., Leather, K. E., Le Breton, M., Jones, B., Young, D., Coe, H., Allan, J., Visser, S., Slowik, J. G., Furger, M., Prevot, A. S. H., Lee, J., Dunmore, R. E., Hopkins, J. R., Hamilton, J. F., Lewis, A. C., Whalley, L. K., Sharp, T., Stone, D., Heard, D. E., Fleming, Z. L., Leigh, R., Shallcross, D. E., and Percival, C. J.: The first UK measurements of nitryl chloride using a chemical ionization mass spectrometer in central London in the summer of 2012, and an investigation of the role of Cl atom oxidation, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 120, 5638–5657, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD022629, 2015.

Berndt, T., Richters, S., Jokinen, T., Hyttinen, N., Kurten, T., Otkjaer, R. V., Kjaergaard, H. G., Stratmann, F., Herrmann, H., Sipila, M., Kulmala, M., and Ehn, M.: Hydroxyl radical-induced formation of highly oxidized organic compounds, Nat. Commun., 7, 13677, https://doi.org/10.1038/Ncomms13677, 2016.

Berndt, T., Mentler, B., Scholz, W., Fischer, L., Herrmann, H., Kulmala, M., and Hansel, A.: Accretion product formation from ozonolysis and OH radical reaction of α-pinene: Mechanistic insight and the influence of isoprene and ethylene, Environ. Sci. Technol., 52, 11069–11077, 2018.

Bigi, A. and Harrison, R. M.: Analysis of the air pollution climate at a central urban background site, Atmos. Environ., 44, 2004–2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.028, 2010.

Brean, J., Harrison, R. M., Shi, Z., Beddows, D. C. S., Acton, W. J. F., Hewitt, C. N., Squires, F. A., and Lee, J.: Observations of highly oxidized molecules and particle nucleation in the atmosphere of Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 14933–14947, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-14933-2019, 2019.

Brune, W. H., Baier, B. C., Thomas, J., Ren, X., Cohen, R. C., Pusede, S. E., Browne, E. C., Goldstein, A. H., Gentner, D. R., Keutsch, F. N., Thornton, J. A., Harrold, S., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., and Wennberg, P. O.: Ozone production chemistry in the presence of urban plumes, Faraday Discuss., 189, 169–189, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5fd00204d, 2016.

Chatani, S., Shimo, N., Matsunaga, S., Kajii, Y., Kato, S., Nakashima, Y., Miyazaki, K., Ishii, K., and Ueno, H.: Sensitivity analyses of OH missing sinks over Tokyo metropolitan area in the summer of 2007, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 8975–8986, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-8975-2009, 2009.

Chen, R. J., Zhao, Z. H., and Kan, H. D.: Heavy Smog and Hospital Visits in Beijing, China, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., 188, 1170–1171, https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201304-0678LE, 2013.

Commane, R., Floquet, C. F. A., Ingham, T., Stone, D., Evans, M. J., and Heard, D. E.: Observations of OH and HO2 radicals over West Africa, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 8783–8801, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-8783-2010, 2010.

Crilley, L. R., Kramer, L. J., Ouyang, B., Duan, J., Zhang, W., Tong, S., Ge, M., Tang, K., Qin, M., Xie, P., Shaw, M. D., Lewis, A. C., Mehra, A., Bannan, T. J., Worrall, S. D., Priestley, M., Bacak, A., Coe, H., Allan, J., Percival, C. J., Popoola, O. A. M., Jones, R. L., and Bloss, W. J.: Intercomparison of nitrous acid (HONO) measurement techniques in a megacity (Beijing), Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 6449–6463, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-6449-2019, 2019.

Cryer, D. R.: Measurements of hydroxyl radical reactivity and formaldehyde in the atmosphere, PhD, School of Chemistry, University of Leeds, UK, 2016.

Ehn, M., Thornton, J. A., Kleist, E., Sipila, M., Junninen, H., Pullinen, I., Springer, M., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Lee, B., Lopez-Hilfiker, F., Andres, S., Acir, I. H., Rissanen, M., Jokinen, T., Schobesberger, S., Kangasluoma, J., Kontkanen, J., Nieminen, T., Kurten, T., Nielsen, L. B., Jorgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., Canagaratna, M., Dal Maso, M., Berndt, T., Petaja, T., Wahner, A., Kerminen, V. M., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Wildt, J., and Mentel, T. F.: A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol, Nature, 506, 476–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13032, 2014.

Fuchs, H., Holland, F. and Hofzumahaus, A.: Measurement of tropospheric RO2 and HO2 radicals by a laser-induced fluorescence instrument, Rev. Sci. Instrum., 79, 084104, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2968712, 2008.