the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

XCO2 in an emission hot-spot region: the COCCON Paris campaign 2015

Matthias Frey

Johannes Staufer

Frank Hase

Grégoire Broquet

Irène Xueref-Remy

Frédéric Chevallier

Philippe Ciais

Mahesh Kumar Sha

Pascale Chelin

Pascal Jeseck

Christof Janssen

Jochen Groß

Thomas Blumenstock

Qiansi Tu

Johannes Orphal

Providing timely information on urban greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and their trends to stakeholders relies on reliable measurements of atmospheric concentrations and the understanding of how local emissions and atmospheric transport influence these observations.

Portable Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometers were deployed at five stations in the Paris metropolitan area to provide column-averaged concentrations of CO2 (XCO2) during a field campaign in spring of 2015, as part of the Collaborative Carbon Column Observing Network (COCCON). Here, we describe and analyze the variations of XCO2 observed at different sites and how they changed over time. We find that observations upwind and downwind of the city centre differ significantly in their XCO2 concentrations, while the overall variability of the daily cycle is similar, i.e. increasing during night-time with a strong decrease (typically 2–3 ppm) during the afternoon.

An atmospheric transport model framework (CHIMERE-CAMS) was used to simulate XCO2 and predict the same behaviour seen in the observations, which supports key findings, e.g. that even in a densely populated region like Paris (over 12 million people), biospheric uptake of CO2 can be of major influence on daily XCO2 variations. Despite a general offset between modelled and observed XCO2, the model correctly predicts the impact of the meteorological parameters (e.g. wind direction and speed) on the concentration gradients between different stations. When analyzing local gradients of XCO2 for upwind and downwind station pairs, those local gradients are found to be less sensitive to changes in XCO2 boundary conditions and biogenic fluxes within the domain and we find the model–data agreement further improves. Our modelling framework indicates that the local XCO2 gradient between the stations is dominated by the fossil fuel CO2 signal of the Paris metropolitan area. This further highlights the potential usefulness of XCO2 observations to help optimize future urban GHG emission estimates.

- Article

(5526 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(620 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The works published in this journal are distributed under

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This license does not affect

the Crown copyright work, which is re-usable under the Open Government

Licence (OGL). The Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License and the OGL are

interoperable and do not conflict with, reduce or limit each

other.

© Crown copyright 2019

Atmospheric background concentrations of CO2 measured since 1958 in Mauna Loa, USA, have passed the symbolic milestone of 400 ppm (monthly mean) as of 2013 (Jones, 2013). Properly quantifying fossil fuel CO2 emissions (FFCO2) can contribute to defining effective climate mitigation strategies. We focus our attention on cities, which are a critical part of this endeavour as emissions from urban areas are currently estimated to represent from 53 % to 87 % of global FFCO2, depending on the accounting method considered, and are predicted to increase further (IPCC, 2013; IEA, 2008; Dhakal, 2009). As stated in the IPCC Fifth assessment report, “current and future urbanization trends are significantly different from the past” and “no single factor explains variations in per capita emissions across cities and there are significant differences in per capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions between cities within a single country” (IPCC, 2014). Therefore, findings in one city can often not be simply extrapolated to other urban regions. Furthermore, the large uncertainty of the global contribution of urban areas to CO2 emissions today and in the future is why a new generation of city-scale observing and modelling systems is needed.

In recent years, more and more atmospheric networks have emerged that observe GHG concentrations using the atmosphere as a large-scale integrator, for example in Paris, France (e.g. Bréon et al., 2015; Xueref-Remy et al., 2018), Indianapolis, USA (e.g. Turnbull et al., 2015; Lauvaux et al., 2016); Salt Lake City, USA (Strong et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2018); Heidelberg, Germany (e.g. Levin et al., 2011; Vogel et al., 2013); and Toronto, Canada (e.g. Vogel et al., 2012). The air measured at in situ ground-based stations is considered to be representative of surface CO2 fluxes of a larger surrounding area (1–10 000 km2), i.e. the emissions of the greater Paris area dominate the airshed of Île-de-France (ca. 12 000 km2) (Staufer et al., 2016). If CO2 measurements are performed both upwind and downwind of a city, the concentration gradient between the two locations is influenced by the local net flux strength between both sites and atmospheric mixing (Bréon et al., 2015; Turnbull et al., 2015; Xueref-Remy et al., 2018). To derive quantitative flux estimates, measured concentration data are typically assimilated into numerical atmospheric transport models which calculate the impact of atmospheric mixing on concentration gradients for a given flux space–time distribution. Such a data assimilation framework implemented for Paris with three atmospheric CO2 measurement sites (Xueref-Remy et al., 2018) previously allowed the derivation of quantitative estimates of monthly emissions and their uncertainties over 1 year (Staufer et al., 2016).

Space-borne measurements of the column-average dry air mole fraction of CO2 (XCO2) are increasingly considered for the monitoring of urban CO2. This potential was shown with OCO-2 and GOSAT XCO2 measurements, even though the spatial coverage and temporal sampling frequency of these two instruments were not optimized for FFCO2 (Kort et al., 2012; Janardanan et al., 2016; Schwandner et al., 2017), while other space-borne sensors dedicated to FFCO2 and with an imaging capability are in preparation (O'Brien et al., 2016; Broquet et al., 2018). Important challenges of satellite measurements are that they are not as accurate as in situ ones, having larger systematic errors, while the XCO2 gradients in the column are typically 7–8 times smaller than in the boundary layer. Another difficulty of space-borne imagery with passive instruments is that they will only sample city XCO2 plumes during clear-sky conditions for geostationary satellites and with an additional constraint to observations at around midday for low-Earth-orbiting satellites.

The recent development of a robust portable ground-based FTIR (Fourier transform infrared) spectrometer as described in Gisi et al. (2012) and Hase et al. (2015, 2016) (EM27/SUN, Bruker Optik, Germany) greatly facilitates the measurement of XCO2 from the surface, with better accuracy than from space and with the possibility of continuous daytime observation during clear-sky conditions. Typical compatibility (uncorrected bias) of the EM27/SUN retrievals of the different instruments in a local network is better than 0.01 % (i.e. 0.04 ppm) after a careful calibration procedure and a harmonized processing scheme for all spectrometers (Frey et al., 2015). The Collaborative Carbon Column Observing Network (COCCON) (Frey et al., 2018) intends to offer such a framework for operating the EM27/SUN. This type of spectrometer therefore represents a remarkable opportunity to document XCO2 variability in cities as a direct way to estimate FFCO2 (Hase et al., 2015) or in preparation of satellite missions.

When future low-Earth-orbit operational satellites with passive imaging spectrometers of suitable capabilities to invert FFCO2 sample different cities, this will likely be limited to clear-sky conditions and at a time of the day close to local noon. Increasing the density of the COCCON network stations around cities will allow us to evaluate those XCO2 measurements and to monitor XCO2 during the early morning and afternoon periods, which will not be sampled with low-Earth-orbit satellites. From geostationary orbit, which can also have other benefits, those time periods can however be observed and could be compared to ground-based measurements (e.g. Butz et al., 2015; O'Brien et al., 2016).

This study focuses on the measurements of XCO2 from ground-based EM27/SUN spectrometers deployed within the Paris metropolitan area during a field campaign in the spring of 2015 and modelling results. This campaign can be seen as a demonstration of the COCCON network concept applied to the quantification of an urban FFCO2 source. Several spectrometers were operated by different research groups, while closely following the common procedures suggested by Frey et al. (2015). The paper is organized as follows. After the instrumental and modelling setup descriptions of Sect. 2, the observations of the field campaign and the modelling results will be presented in Sect. 3. Results are discussed in Sect. 4 together with the study conclusions.

2.1 Description of study area and field campaign design

During the COCCON field campaign (28 April to 13 May 2015) five portable FTIR spectrometers (EM27/SUN, Bruker Optik, Karlsruhe, Germany) were deployed in the Parisian region (administratively known as Île-de-France) and within the city of Paris. The campaign was conducted in early spring as the cloud cover is typically low in April and May and the time between sunrise and sunset is more than 14 h.

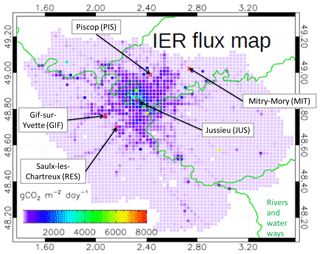

The Paris metropolitan area houses over 12 million people, with about 2.2 million inhabiting the city of Paris. This urban region is the most densely populated in France with ∼ 1000 inhabitants/km2 and over 21 000 inhabitants/km2 for the city of Paris itself (INSEE, 2016). The estimated CO2 emissions from the metropolitan region are 39 Mt yr−1, according to the air quality association AIRPARIF (Association de surveillance de la qualité de l'air en Île-de-France), which monitors the airshed of greater Paris. On-road traffic emissions and the residential and tertiary (i.e. commercial) sectors are the main sources (accounting for over 75 %), and there are minor contributions from other sectors such as industrial sources and airports (https://www.airparif.asso.fr/en/, AIRPARIF, 2016). It was crucial to understand the spatial distribution of these CO2 sources to optimally deploy the COCCON spectrometers. To this end a 1 km emission model for France by IER (Institut für Energiewirtschaft und Rationelle Energieanwendung, University of Stuttgart, Germany) was used as a starting point (Latoska, 2009). This emission inventory is based on the available activity data such as, for example, traffic counts, housing statistics, or energy use, and the temporal disaggregation was implemented according to Vogel et al. (2013). In brief, the total emissions of the IER model were rescaled to match the temporal factors for the different emission sectors according to known national temporal emission profiles.

To quantify the impact of urban emissions on XCO2, the FTIR instruments were deployed along the dominant wind directions in this region in spring, i.e. southwesterly (Staufer et al., 2016), in order to maximize the likelihood to capture upwind and downwind air masses (see Fig. 1). The two southwesterly sites (GIF and RES; see Table 2 for site abbreviations) are located in a less densely populated area, where emissions are typically lower than in the city centre, where the station JUS is located. The data in Fig. 1 show that the densest FFCO2 emission area extends northwards and eastwards. The two northwesterly sites (PIS and MIT) were placed downwind of this area. All instruments were operated manually and typically started operation at around 07:00–08:00 local time from which they continuously observe XCO2 until 17:00–18:00 LT.

2.2 Instrumentation, calibration, and data processing

The EM27/SUN is a portable FTIR spectrometer which has been described in detail in Gisi et al. (2012) and Frey et al. (2015), for example. Here, only a short overview is given. The centrepiece of the instrument is a Michelson interferometer which splits up the incoming solar radiation into two beams. After inserting a path difference between the beams, the partial beams are recombined. The modulated signal is detected by an InGaAs detector covering the spectral domain from 5000 to 11000 cm−1 and is called an interferogram. As the EM27/SUN analyzes solar radiation, it can only operate in sunny daylight conditions. A Fourier transform of the interferogram generates the spectrum and a DC correction is applied to remove the background signal and only keep the AC signal (see Keppel-Aleks et al., 2007). A numerical fitting procedure (PROFFIT code) (Schneider and Hase, 2009) then retrieves column abundances of the concentrations of the observed gases from the spectrum. The single-channel EM27/SUN is able to measure total columns of O2, CO2, CH4 and H2O. The ratio over the observed O2 column, assumed to be known and constant, delivers the column-averaged trace gas concentrations of XCO2 and XCH4 in µmol mol−1 dry air, with a temporal resolution of 1 min. XCO2 is the dry air mole fraction of CO2, defined as XCO2 = column[CO2]∕column[dry air]. Applying the ratio over the observed oxygen (O2) column reduces the effect of various possible systematic errors; see Wunch et al. (2011).

In order to correctly quantify small differences in XCO2 columns between Paris upstream and downstream locations, measurements were performed with the five FTIR instruments side by side before and after the campaign, as we expect small calibration differences between the different instruments due to slightly different alignment for each individual spectrometer. These differences are constant over time and can be easily accounted for by applying a calibration factor for each instrument. Previous studies showed that the instrument-specific corrections are well below 0.1 % for XCO2 (Frey et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016) and are stable for individual devices. The 1σ precision for XCO2 is on the order of 0.01 %–0.02 % (< 0.08 ppm) (e.g. Gisi et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2016; Hedelius et al., 2016; Klappenbach et al., 2015). The calibration measurements for this campaign were performed in Karlsruhe using the Total Carbon Column Observing Network (TCCON) (Wunch et al., 2011) spectrometer at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany, for 7 days before the Paris campaign between 9 and 23 April and after the campaign on 18 until 21 May.

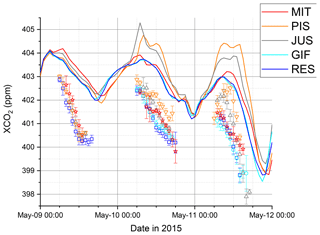

Figure S1 (left panel) shows the XCO2 time series of the calibration campaign, in which small offsets between the instruments' raw data are visible. As these offsets are constant over time, a calibration factor for each instrument can be easily applied; actually these are the calibration factors previously found for the Berlin campaign (Frey et al., 2015). These factors are given in Table 1, for which all EM27/SUN instruments are scaled to match instrument no. 1. The calibrated XCO2 values for 15 April are shown in Fig. S1. None of the five instruments that participated in the Berlin campaign show any significant drift; in other words, the calibration factors found 1 year before were still applicable. This is a good demonstration of the instrument stability stated in Sect. 2.2, especially as several instruments (nos. 1, 3, 5) were used in another campaign in northern Germany in the meantime. The EM27/SUN XCO2 measurements can also be made traceable to the WMO international scale for in situ measurements by comparison with measurements of a collocated TCCON spectrometer, which are calibrated against in situ standards by aircraft and air-core measurements (Wunch et al., 2010; Messerschmidt et al., 2011) performed using the WMO scale.

Table 1Normalization factors for the five EM27/SUN instruments derived during measurements before and after the Paris field campaign. Values in parentheses are standard deviations. Measurements of instrument 1 were arbitrarily chosen as the reference from which the others were scaled. The calibration factors from a previous field campaign in Berlin (Hase et al., 2015) are also shown. Calibration factors between the two field campaigns agree well within 0.02 % (∼0.08 ppm) for all instruments.

During the campaign and for the calibration measurements we recorded double-sided interferograms with 0.5 cm−1 spectral resolution. Each measurement of 58 s duration consisted of 10 scans using a scanner velocity of 10 kHz. For precise timekeeping, we used GPS sensors for each spectrometer.

In situ surface pressure data used for the analysis of the calibration measurements performed at KIT were recorded at the co-located meteorological tall tower. During the campaign, a MHD-382SD data logger recorded local pressure, temperature and relative humidity at each station. The analysis of the trace gases from the measured spectra for the calibration measurements has been performed as described by Frey et al. (2015). For the campaign measurements we assume a common vertical pressure–temperature profile for all sites, provided by the model, so that the surface pressure at each spectrometer only differs due to different site altitudes. The 3-hourly temperature profile from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) operational analyses interpolated for site JUS located in the centre of the array was used for the spectra analysis at all sites. The individual ground pressure was derived from site altitudes and pressure measurements performed at each site.

Before and after the Paris campaign, side-by-side comparison measurements were performed with all five EM27/SUN spectrometers and the TCCON spectrometer operated in Karlsruhe at KIT. All spectrometers were placed on the top of the IMK office building north of Karlsruhe. The altitude is 133 m above sea level (a.s.l.); coordinates are 49.09∘ N and 8.43∘ E. The processing of the Paris raw observations (measured interferograms) was performed as described by Gisi et al. (2012) and Frey et al. (2015) for the Berlin campaign: spectra were generated applying a DC correction, a Norton–Beer medium apodization function and a spectral resampling of the sampling grid resulting from the FFT on a minimally sampled spectral grid. PROFFWD was used as the radiative transfer model and PROFFIT as the retrieval code.

2.3 Atmospheric transport modelling framework

We used the chemistry transport model CHIMERE (Menut et al., 2013) to simulate CO2 concentrations in the Paris area. More specifically, we used the CHIMERE configuration over which the inversion system of Bréon et al. (2015) and Staufer et al. (2016) was built to derive monthly to 6 h mean estimates of the CO2 Paris emissions. Its horizontal grid, and thus its domain and its spatial resolution, is illustrated in Fig. S2. It has a 2×2 km2 spatial resolution for the Paris region, and 2×10 and 10×10 km2 spatial resolutions for the surroundings. It has 20 vertical hybrid pressure-sigma (terrain-following) layers that range from the surface to the mid-troposphere, up to 500 hPa. It is driven by operational meteorological analyses of the ECMWF Integrated Forecasting System, available at an approximately 15×15 km2 spatial resolution and 3 h temporal resolution.

In this study the CO2 simulations are based on a forward run over 25 April–12 May 2015 with this model configuration; we do not assimilate atmospheric CO2 data and so no inversion for surface fluxes was conducted. In the Paris area (the Île-de-France administrative region), hourly anthropogenic emissions are given by the IER inventory; see Sect. 2.1. The anthropogenic emissions in the rest of the domain are prescribed from the EDGAR V4.2 database for the year 2010 at 0.1∘ resolution (Olivier and Janssens-Maenhout et al., 2012). In the whole simulation domain, the natural fluxes (the net ecosystem exchange, NEE) are prescribed using simulations of CTESSEL, which is the land-surface component of the ECMWF forecasting system (Boussetta et al., 2013), at a 3 hourly and 15×15 km2 resolution. Finally, the CO2 boundary conditions at the lateral and top boundaries of the simulation domain and the simulation CO2 initial conditions on 25 April 2015 are prescribed using the CO2 forecast issued by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS, http://atmosphere.copernicus.eu/, last access: last access: 1 March 2019) at a ∼15 km global resolution (Agustí-Panareda et al., 2014).

The CHIMERE transport model is used to simulate the XCO2 data. However, since the model does not cover the atmosphere up to its top, the CO2 fields from CHIMERE are complemented with those of the CAMS CO2 forecasts from 500 hPa to the top of the atmosphere to derive total column concentrations. The derivation of modelled XCO2 at the sites involves obtaining a kernel-smoothed CO2 profile of CHIMERE and CAMS and vertical integration of these smoothed profiles, weighted by the pressure at the horizontal location of the sites.

The parametrization used to smooth modelled CO2 profiles approximates the sensitivity of the EM27/SUN CO2 retrieval as a function of pressure and sun elevation. Between 1000 and 480 hPa, a linear dependency of the instrument averaging kernels on solar zenith angle (Θ) is assumed with boundary values following Frey et al. (2015):

where ∘ Approximate averaging kernels are obtained by linear interpolation to the pressure levels of CHIMERE and CAMS. If p > 1000 hPa, k is linearly extrapolated. Above 480 hPa (p < 480 hPa), the averaging kernels can be approximated by

where u is (480 hPa−p)∕480. The kernel-smoothed CO2 profile, , is obtained by

where CO2_model is the modelled CO2 profile by CHIMERE or CAMS, I the identity matrix and K is a diagonal matrix containing the averaging kernels k. The a priori CO2 profile, , is provided by the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model (WACCM) model (version 6) and interpolated to the pressure levels of CHIMERE and CAMS. is the appropriate CO2 profile to calculate modelled XCO2 at the location of the sites.

For a given site, the simulated XCO2 data are thus computed from the vertical profile of this site as

where psurf is the surface pressure, ptop_CHIM=500 hPa the pressure corresponding to the top boundary of the CHIMERE model, and and are the smoothed CO2 concentrations of CHIMERE and CAMS, respectively. For comparison we also calculated XCO2 at a lower spatial resolution with the CAMS data alone as

3.1 Observations

3.1.1 Meteorological conditions and data coverage/instrument performance

During the measurement campaign (28 April until 13 May 2015), meteorological conditions were a major limitation for the availability of XCO2 observations. Useful EM27/SUN measurements require direct sunlight, and low wind speeds typically yield higher local XCO2. Most of the time during the campaign, conditions were partly cloudy and turbid, and so successful measurements at a high solar zenith angle (SZA) were rare. Therefore, the data coverage between 28 April and 3 May is limited (see Table 2). As is typical for spring periods in Paris, the temperature and the wind direction vary and display less synoptic variations than in winter. The dominant wind directions were mostly northeasterly at the beginning of the campaign and mostly southeasterly during the second half of the campaign. We find that the wind speeds during daytime nearly always surpass 3 m s−1, which has been identified by Bréon et al. (2015) and Staufer et al. (2016) as the cut-off wind speed above which the atmospheric transport model CHIMERE performs best in modelling CO2 concentration gradients in the mixed layer.

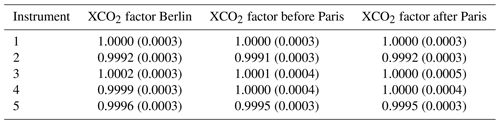

Table 2Summary of all measurement days with the number of observations at each of the sites, Mitry-Mory (MIT), Gif-sur-Yvette (GIF), Piscop (PIS), Saulx-les-Chartreux (RES) and Jussieu (JUS), the overall quality ranking of each day according to the number of available observations and temporal coverage (with classification from poor to great: +, , , , and the ground-level wind speed and direction.

Despite some periods with unfavourable conditions, more than 10 000 spectra were retrieved among the five deployed instruments. The quality of the spectra for each day was rated according to the overall data availability and to be consistent with Hase et al. (2015). The best measurement conditions prevailed for the period between 7 and 12 May.

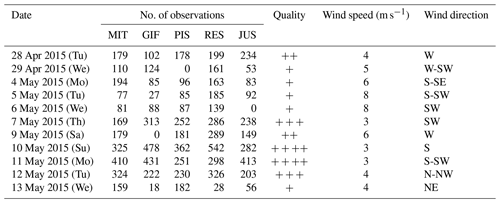

3.1.2 Observations of XCO2 in Paris

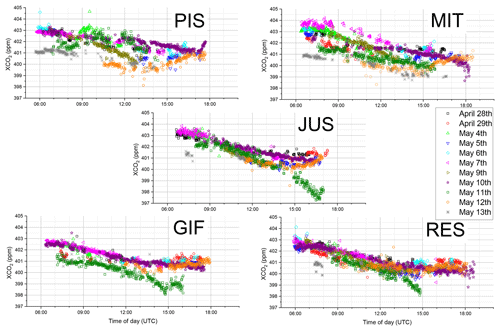

The observed XCO2 in the Paris region for all sites (10 415 observations) ranges from 397.27 to 404.66 ppm with a mean of 401.26 ppm (a median of 401.15 ppm). The strong atmospheric variability of XCO2 across Paris and within the campaign period is reflected in the standard deviation of 1.04 ppm for 1 min averages. We find that all sites exhibit very similar diurnal behaviours with a clear decrease in XCO2 during the daytime and a noticeable day-to-day variability as seen in Fig. 2. This is to be expected as they are all subject to very similar atmospheric transport in the boundary layer height and to similar large-scale influences, i.e. surrounded by stronger natural fluxes or air mass exchange with other regions at synoptic timescales. However, observed XCO2 concentrations at the downwind sites for our network remain clearly higher from sites that are upwind of Paris (see Fig. 2). The shifting dominant wind conditions also explain why the sites RES and GIF are lowest in the beginning of the campaign and higher on 12 and 13 May after meteorological conditions changed. This indicates that the influence of urban emissions is detectable with this network configuration under favourable meteorological conditions. By comparing the different daily variations in Fig. 3, it is apparent that the day-to-day variations observed at the two southwesterly (typically upwind) sites GIF and RES are approximately 1 ppm, with both sites exhibiting similar diurnal variations throughout the campaign period. This can be expected as their close vicinity would suggest that they are sensitive to emissions from similar areas and to concentrations of air masses arriving from the southwest.

Figure 2Time series of observed XCO2 in the Parisian region for all five sites (all valid data of 1 min averages).

The typical decrease in XCO2 found over the course of a day is about 2 to 3 ppm. This decrease could be driven by (natural) sinks of CO2, which can be expected to be very strong as our campaign took place after the start of the growing season in Europe for most of southern and central Europe (Rötzer and Chmielewski, 2001).

The observations at the site located in Paris (JUS) display similarly low day-to-day variations and a clear decrease in XCO2 over the course of the day. The latter feature indicates that even in the dense city centre, XCO2 is primarily representative of a large footprint like in other areas of the globe (Keppel-Aleks, 2011) and supports the findings of Belikov et al. (2017) concerning the footprints for the Paris and Orleans TCCON sites. Thus, our total column observations are less critically affected by local emissions than in situ measurements (Bréon et al., 2015; Ammoura et al., 2016). It is also apparent that the decrease in XCO2 (the slope) during the afternoon for 28 and 29 April as well as 7 and 10 May is noticeably smaller than on other days during this campaign. As XCO2 is not sensitive to vertical mixing, this has to be caused by different CO2 sources and sinks acting upon the total column arriving at JUS.

The two (typically downwind) sites PIS and MIT northeast of Paris show a markedly larger day-to-day spread in their general XCO2 levels as well as strongly changing slopes for the diurnal XCO2 decrease. For these sites the exact wind direction is critical as they can be downwind of the city centre that has a much higher emission density or less dense suburbs (see Fig. 1).

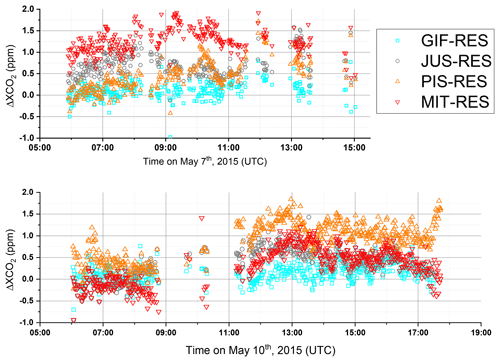

3.1.3 Gradients in observed XCO2

In order to focus more on the impact of local emissions on atmospheric conditions and less on that of CO2 fluxes from outside of our urban domain in our analysis of XCO2, we choose to study the spatial gradients (Δ) among different sites. Fundamentally, this approach assumes that regional- and large-scale fluxes have a similar impact on XCO2 for the sites within our network due to the close proximity of sites and the smoothing of remote emission signals due to atmospheric transport by the time the air mass arrives in our domain. Ideal conditions were sampled on 7 May, with predominantly southwesterly winds, and on 10 May with southerly winds. We can see in Fig. 4 that all sites were, on average, elevated compared to RES, chosen as reference here as it was upwind of Paris during those days. The hodographs for both days also indicate that the wind fields were consistent across Paris (see Fig. S3). The observations from GIF showed only minimal differences with RES, while the rest of the sites (PIS, JUS and MIT) had Δ values of 1 to 1.5 ppm. During southwesterly winds, MIT is downwind of the densest part of the Paris urban area, and JUS is impacted by emissions of neighbourhoods to the southwest. The site of PIS is still noticeably influenced by the city centre but, as can be seen in Fig. 1, we likely do not catch the plume of the most intense emissions but rather from the suburbs. On 10 May, with its dominant southerly winds, the situation was markedly different. While GIF was still only slightly elevated, the XCO2 enhancement at MIT was significantly lower and quite similar to JUS for large parts of the day. The highest ΔXCO2 can be observed at PIS, again typically ranging from 1 to 1.5 ppm. As seen in Fig. 1, PIS is then directly downwind of the densest emission area, while MIT is only exposed to CO2 emissions from the eastern outskirts of Paris.

It is also important to note that the impact of the local biosphere that is assumed to cause the strong decrease in XCO2 during the day is not seen on both days for these spatial gradients. For a more comprehensive interpretation of these observations the use of a transport model (as described in Sect. 2.3) is necessary.

3.2 Modelling

3.2.1 Model performance

Before interpreting the modelled XCO2 we need to evaluate the performance of the chosen atmospheric transport model framework as described in Sect. 2.3. Comparing it to meteorological observations (wind speed and wind direction) at GIF, we find that CHIMERE predicts these variables well throughout the duration of the campaign (see Fig. S4). Changes in wind speed direction and speed are reproduced with a slight overestimation at low wind speeds (> 1 m s−1). In addition to the meteorological forcing, the model performance can also be expected to depend on the chosen model resolution. Therefore, we compared XCO2 at JUS calculated based on the coarser-resolution atmospheric transport and flux framework CAMS (15 km) and the higher-resolution emission modelling input for the framework based on CHIMERE (2 km) for the inner domain and based on CAMS boundary conditions (see Fig. S2). We find that the coarser model displays similar inter-daily variations, but that the high-resolution model modifies the modelling results on shorter timescales. We find that the afternoon XCO2 decreases are often more pronounced in CHIMERE. Only the high resolution will be considered and referred to in the following. The impact of using different flux maps (fossil fuel CO2) on the modelled XCO2 can unfortunately not be explicitly investigated here as only one high-resolution (1 km) emission product available for fossil fuel CO2 was available for this study region (see Sect. 2.3), and other global emission products are usually not intended for urban-scale studies.

3.2.2 Modelled XCO2 and its components

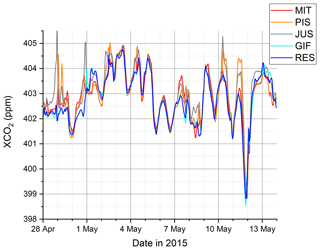

The modelled XCO2 for the five sites (Fig. 5) co-evolves over the period of the campaign with occurrences of significant differences. This was already seen with the measurements, but the model allows us to look at the full time series. The model reveals clear daily cycles of XCO2, with an accumulation during the night-time and a decrease during the daytime. Despite a good general agreement of modelled XCO2 at all sites for the timing of daily minima and their synoptic changes, for example, differences in XCO2 are observed between the sites for many days. Typically the northeasterly sites (PIS, MIT) show an enhancement in modelled XCO2 compared to the southwesterly sites (GIF, RES).

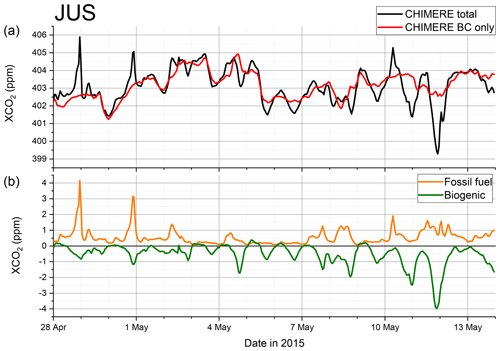

To understand the synoptic and diurnal variations of the modelled XCO2, we analyzed the contribution of different sources (and sinks) of CO2, namely the NEE, the fossil fuel CO2 emissions (FFCO2) and the boundary conditions (BCs), i.e. the variations of CO2 not caused by fluxes within our domain (the example of JUS is given in Fig. 6). The day-to-day variability of modelled XCO2 is dominated by changing boundary conditions and coincides with synoptic weather changes. As the CO2 emitted from the different sources is transported in the model as independent tracers, the strong daily decrease in XCO2 can be directly linked to NEE, which leads to a decrease of ∼1 ppm (but up to 4 ppm) during the day, but can also cause positive enhancements during the night-time driven by biogenic respiration. The XCO2 from fossil fuel emissions causes significant enhancements compared to the background but is often compensated by NEE. During short periods, fossil fuel emissions can however lead to enhancements of up to 4 ppm.

Figure 6Time series of XCO2 and related fluxes for JUS. Panel (a) provides a comparison of modelled total XCO2 and XCO2 variations due to changes in boundary conditions (BC only). Panel (b) shows the contribution of the different flux components, namely fossil fuel CO2 emissions and biogenic fluxes.

3.2.3 Modelled ΔXCO2 gradients and its components

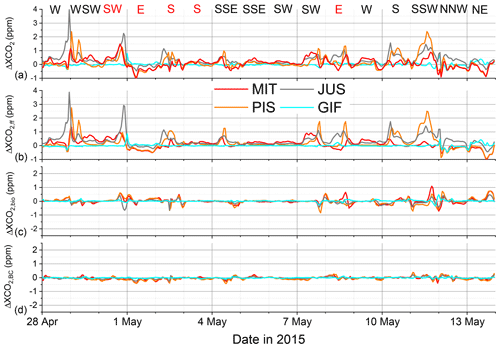

To be able to assess the impact of local sources and reduce the influence of NEE and BC on the modelled signals, we analyze the XCO2 gradient (i.e. station-to-station difference) with RES being taken as reference. In Fig. 7a we compare Δ and its components, i.e. fossil fuel CO2, biogenic CO2 and CO2 transported across the boundary of the domain (BCs), along a south–north direction. For the modelled Δ we can see that MIT shows a positive value during the campaign period whenever the predominant wind direction was southwesterly. We also find that Δ between JUS and RES was both negative and positive during the campaign and predominantly negative between MIT and JUS. When split into FFCO2, BC and NEE components, we can clearly see that the total Δ is dominated by FF causing XCO2 offsets of up to 4 ppm, but more typically 1 ppm gradients are observed. Gradients can also change rapidly (within a few hours) if the wind direction changes, for example on 1 and 12 May. This highlights the fact that, during such conditions, we cannot assume a simple upwind–downwind interpretation of our sites. As expected, the contributions from BC and NEE are generally greatly reduced when analyzing ΔXCO2. The most important impact of NEE on the XCO2 gradients of −1 and +1 ppm can be seen on 8 and 11 May, respectively. This means that, despite greatly reducing the impact of NEE on average, the contribution of NEE cannot be fully ignored. BC is an overall negligible contribution to ΔXCO2, even though it reaches −0.4 ppm on 11 May.

Figure 7Modelled XCO2 gradients for each station relative to RES are given in (a) with its contributing components in the panels below. Total ΔXCO2 (a), the fossil fuel contribution to ΔXCO2,ff (b), the biogenic contribution to ΔXCO2,bio (c) and the influence of the boundary conditions ΔXCO2,BC (d). The dominant wind conditions for each day given at the top of the figure and days without observations due to precipitation are in red.

3.3 Model data and observation comparison

3.3.1 XCO2

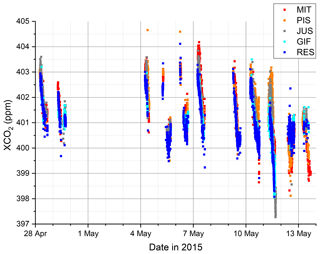

A comparison of modelled and observed XCO2 is of course limited to the relatively short periods when observations are available. Over these periods we can see a general issue in reproducing the general XCO2 for each day in the model as observed XCO2 is significantly lower, revealing a fairly stable bias between 1 and 2 ppm. As our CO2 boundary conditions were from a forecast product, this is not unexpected, as already small issues in estimating carbon uptake (or emissions) at the European scale can have such an impact on the boundary conditions. However, we observe that the main features, like daily cycles and synoptic changes of the modelled and observed XCO2, are comparable as seen in Fig. 8. The daytime variations are well reproduced by the model and the general relative concentrations among sites are preserved, e.g. the highest values for XCO2 at MIT are on 9 May and the highest XCO2 values for PIS are later on 10 and 11 May. We also see that the timing of the daily minima is not fully covered in the observed data as it typically happens after sunset and cessation of biosphere uptake. To reduce the impact of uncertainties of the boundary conditions on our analysis, a gradient approach was tested.

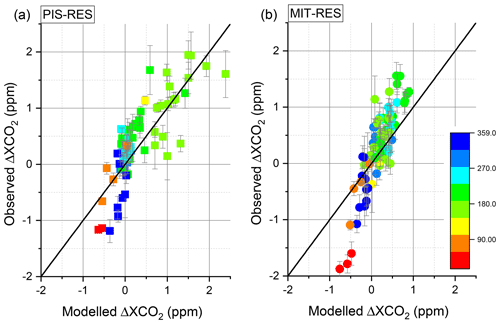

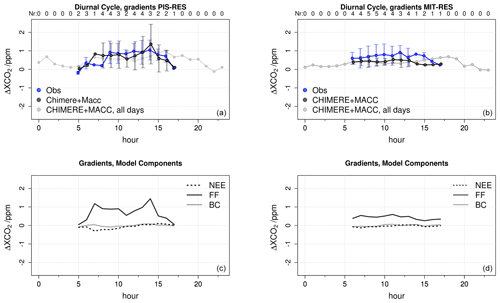

3.3.2 ΔXCO2

Due to the prevailing southeasterly wind conditions, we can compare XCO2 at the typical downwind sites (PIS, MIT) relative to the mostly upwind sites (RES, GIF) and expect elevated XCO2 downwind. Furthermore, we can expect to see negative gradients for opposing wind conditions, i.e. northwesterly. For other wind conditions, the concentration difference is not determined by emissions between the station pairs but rather by the areas upwind of the sites (see Fig. 1). We find that the model versus observed ΔXCO2 of PIS relative to RES generally falls along the 1:1 line with a slope of 1.07±0.09 with a Pearson's R of 0.8. Negative ΔXCO2 values, seen in Fig. 9, are associated with meteorological conditions when winds come from northerly directions; i.e. the roles of normal upwind and downwind sites are reversed. For wind perpendicular to the direct line of sight for (PIS, RES) the concentration enhancements are small and harder to interpret. The gradient of XCO2 MIT relative to RES has a significantly lower range for modelled XCO2 while the observed range of XCO2 is similar to PIS. The slope of observed to modelled ΔXCO2 for upwind–downwind (or downwind–upwind conditions) is 1.72±0.06 with a Pearson's R of 0.96. This points to a significant underestimation of the impact of urban sources on the MIT–RES gradient, which is especially visible in the more negative ΔXCO2 during northerly wind conditions. This could indicate that the spatial distribution of our emissions prior should be improved; i.e. emissions in the eastern outskirts/suburbs are likely underestimated in the IER emissions model. The low modelled ΔXCO2 could also be due to overestimated horizontal dispersion in the model, which seems less likely. Again the model does not predict concentration differences well for perpendicular wind conditions. When comparing the mean modelled daily cycle of the days with southwesterly wind conditions and when observations exist with the mean diurnal cycle for all days within the field campaign period when MIT and PIS can be considered downwind of RES, we find that the days with observations do not significantly differ from those without observations (see Fig. 10). An investigation of typical diurnal variations of modelled ΔXCO2 can only be performed to a limited degree with the observational data available for suitable wind conditions. Within the large uncertainties, the modelled and observed ΔXCO2 agree throughout the day. When analyzing the modelled ΔXCO2 components we also find that the observed daytime increases in ΔXCO2 are driven by CO2 added by urban FFCO2 burning and that the impact of FF is significantly higher at the PIS (up to 1 ppm) than at the MIT site (0.5 ppm) in the model, when both sites are downwind of Parisian emissions. Our observations indicate that both sites have strong diurnal variations. Given that the most important biogenic sinks, in our domain, can be expected to be found in the rural parts surrounding Paris, we would expect the biogenic contribution to be similar at both sites (as predicted by the model). This would further point towards the impact of FF emissions on the MIT site being larger than predicted by our modelling framework.

Figure 9Comparison of modelled and observed hourly averaged ΔXCO2 for gradients between PIS and RES (a) and MIT and RES (b), with standard deviations of the minute values of the hourly mean as vertical bars and the points colour coded by wind direction from 0 to 359∘.

Figure 10Comparison of modelled (black) and observed mean daily cycles (blue) of hourly averaged ΔXCO2 of PIS (a) and of MIT (b) during the campaign when RES can be considered an upwind site. Labels at the top of (a) and (b) denote the number of days contributing to the mean. The mean daily cycle for all days within the campaign period when PIS and MIT are downwind of RES is given in light grey. The modelled contribution of different CO2 sources–sinks to the mean daily cycle for days with observations for the two sites is given in (c) and (d).

Different ΔXCO2 diurnal variations can be found for other upwind–downwind site pairs, but they are all systematically driven by the locally added CO2 from FFCO2.

For the 2-week field campaign we demonstrated the ability of a network of five EM27/SUN spectrometers, placed on the outskirts of Paris, to track the XCO2 changes due to the urban plume of the city. However, we also found that XCO2 cannot be simply interpreted in the context of local emissions as, even in such a densely populated area, XCO2 is still significantly influenced by natural CO2 uptake during the growing season. Understanding the area influencing XCO2 and/or the use of suitable atmospheric transport models seems indispensable to correctly interpret atmospheric XCO2 variations. Using a gradient approach, i.e. analyzing the difference between XCO2 measured at upwind and downwind stations, greatly reduced the impact of the CO2 boundary condition, which reflects fluxes outside the domain and biogenic fluxes within the domain. Overall, the XCO2 variability modelled using our ECMWF CHIMERE system with IER (1×1 km2) emissions data was found to be comparable with the observed variability and diurnal evolution of XCO2, despite a higher background for modelled XCO2. Our modelling framework, run at a 2×2 km2 resolution over Paris also predicts that biogenic fluxes and boundary conditions (i.e. the influence of CO2 being transported into our domain) have only a very small impact on ΔXCO2 during a few situations, specifically when meteorological condition changes made the concept of “upwind” and “downwind” not applicable. When comparing modelled and measured ΔXCO2, we find strong correlations (Pearson's R) of 0.8 and 0.96 for PIS–RES and MIT–RES, respectively. The offset between model and observations also diminished for ΔXCO2 and the slope found between the observed and modelled PIS–RES gradients is statistically in accordance with a 1:1 relationship (1.07±0.09). However, the slope of the MIT–RES XCO2 gradient of 1.72±0.06 suggests that the emission model could potentially be improved, as it seems unlikely that the general atmospheric transport in the model is the key issue as both site pairs would be subject to very similar winds. Another potential source of error that needs to be investigated is if such an underestimation of ΔXCO2 could be caused by the limited model resolution. It also seems rather likely that a 2×2 km2 model would cause a general spreading of point source emissions and not systematically underestimate emissions impacts from less densely populated parts of Île-de-France. The data also confirm previous results by models that XCO2 gradients caused by a megacity do not exceed 2 ppm, which supports the previous requirement for satellite observations of less than 1 ppm precision on individual soundings and biases lower than 0.5 ppm (Ciais et al., 2015). The gradients are mainly caused by the transport of FFCO2 emissions but, interestingly, during specific episodes, a noticeable contribution comes from biogenic fluxes, suggesting that these fluxes cannot always be neglected even when using gradients.

Unfortunately, the duration of the campaign was relatively short, so that an in-depth analysis of mean daily cycles or the impact of ambient conditions (traffic conditions, temperature, solar insolation, etc.) on the observed gradient and underlying fluxes could not be investigated here. Hence, future studies in Paris and elsewhere should aim to perform longer-term observations during different seasons, which will allow better understanding of changes in biogenic and anthropogenic CO2 fluxes. A remotely controllable shelter for the EM27/SUN instrument is currently under development (Heinle and Chen, 2018). This will considerably facilitate the establishment of permanent spectrometer arrays around cities and other sources of interest. Nevertheless, our study already indicates that such observations of urban XCO2 and ΔXCO2 contain original information to understand local sources and sinks and that the modelling framework used here is a step forward to support their detailed interpretation in the future. An improved model will also be able to adjust or better model the background conditions and potentially use this type of observations to estimate local CO2 fluxes using a Bayesian inversion scheme similar to the existing system based on in situ observations for Paris (Staufer et al., 2016).

We expect that the previous successful collaboration in the framework of the Paris campaign will mark the permanent implementation of COCCON as a common framework for a French–Canadian–German collaboration on the EM27/SUN instrument. The acquisition of additional spectrometers is planned by several partners.

The data are available from the corresponding author upon request. The CHIMERE modelling system source code and documentation is freely available from the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, France, http://www.lmd.polytechnique.fr/chimere/ (last access: 4 March 2019).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-3271-2019-supplement.

FRV, MF, FH, IXR, MKS, PCh, PJ, YT, CJ, TB, QT and JO supported the field campaign and contributed data to this study.

MF, FH, FRV, JS, GB and PCi planned the fieldwork and modelling activities for this study.

JS, GB, FC, and FRV performed the CHIMERE modelling, provided modelling data input and/or analyzed the output data.

MF, FH and FRV processed and analyzed the EM27/SUN data.

FRV, MF, JS, FH and PCi wrote sections of the paper and created figures and tables.

All authors reviewed, edited and approved the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their

comments that helped to significantly improve this paper. ECCC would like to

thank Ray Nasser (CRD) and Yves Rochon (AQRD) for their internal review. The

authors from LSCE acknowledge the support of the SATINV group of Frederic

Chevallier. The authors from KIT acknowledge support from the Helmholtz

Research Infrastructure ACROSS. The authors from LISA acknowledge support

from the OSU-EFLUVE (Observatoire des Sciences de l'Univers-Enveloppes

Fluides de la Ville à l'Exobiologie).

Edited by: Ronald Cohen

Reviewed by: three anonymous referees

Agustí-Panareda, A., Massart, S., Chevallier, F., Boussetta, S., Balsamo, G., Beljaars, A., Ciais, P., Deutscher, N. M., Engelen, R., Jones, L., Kivi, R., Paris, J.-D., Peuch, V.-H., Sherlock, V., Vermeulen, A. T., Wennberg, P. O., and Wunch, D.: Forecasting global atmospheric CO2, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 11959–11983, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-11959-2014, 2014.

AIRPARIF: Inventaire régional des émissions en Île-de-France Année de référence 2012 – éléments synthétiques, Edition Mai 2016, Paris, France, available at: https://www.airparif.asso.fr/_pdf/publications/inventaire-emissions-idf-2012-150121.pdf (last access: 14 December 2017), 2016.

Ammoura, L., Xueref-Remy, I., Vogel, F., Gros, V., Baudic, A., Bonsang, B., Delmotte, M., Té, Y., and Chevallier, F.: Exploiting stagnant conditions to derive robust emission ratio estimates for CO2, CO and volatile organic compounds in Paris, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 15653–15664, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-15653-2016, 2016.

Belikov, D., Maksyutov, S., Ganshin, A., Zhuravlev, R., Deutscher, N. M., Wunch, D., Feist, D. G., Morino, I., Parker, R. J., Strong, K., and Yoshida, Y.: Study of the footprints of short-term variation in XCO2 observed by TCCON sites using NIES and FLEXPART atmospheric transport models, 2017.

Bréon, F. M., Broquet, G., Puygrenier, V., Chevallier, F., Xueref-Remy, I., Ramonet, M., Dieudonné, E., Lopez, M., Schmidt, M., Perrussel, O., and Ciais, P.: An attempt at estimating Paris area CO2 emissions from atmospheric concentration measurements, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 1707–1724, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-1707-2015, 2015.

Broquet, G., Bréon, F.-M., Renault, E., Buchwitz, M., Reuter, M., Bovensmann, H., Chevallier, F., Wu, L., and Ciais, P.: The potential of satellite spectro-imagery for monitoring CO2 emissions from large cities, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 681–708, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-681-2018, 2018.

Boussetta, S., Balsamo, G., Beljaars, A., Panareda, A. A., Calvet, J. C., Jacobs, C., Hurk, B., Viterbo, P., Lafont, S., Dutra, E., and Jarlan, L.: Natural land carbon dioxide exchanges in the ECMWF Integrated Forecasting System: Implementation and offline validation, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 5923–5946, 2013.

Butz, A., Orphal, J., Checa-Garcia, R., Friedl-Vallon, F., von Clarmann, T., Bovensmann, H., Hasekamp, O., Landgraf, J., Knigge, T., Weise, D., Sqalli-Houssini, O., and Kemper, D.: Geostationary Emission Explorer for Europe (G3E): mission concept and initial performance assessment, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 4719–4734, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-4719-2015, 2015.

Chen, J., Viatte, C., Hedelius, J. K., Jones, T., Franklin, J. E., Parker, H., Gottlieb, E. W., Wennberg, P. O., Dubey, M. K., and Wofsy, S. C.: Differential column measurements using compact solar-tracking spectrometers, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 8479–8498, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-8479-2016, 2016.

Ciais, P., Crisp, D., Denier van der Gon, H., Engelen, R., Heimann, M., Janssens-Maenhout, G., Rayner, P., and Scholze, M.: Towards a European Operational Observing System to Monitor Fossil CO2 Emissions, Final Report from the Expert Group, European Commission, October 2015, available at: http://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/news_docs/CO2_report_22-10-2015.pdf (last access: 6 February 2018), 2015.

Dhakal, S.: Urban energy use and carbon emissions from cities in China and policy implications, Energ. Policy, 37, 4208–4219, 2009.

Frey, M., Hase, F., Blumenstock, T., Groß, J., Kiel, M., Mengistu Tsidu, G., Schäfer, K., Sha, M. K., and Orphal, J.: Calibration and instrumental line shape characterization of a set of portable FTIR spectrometers for detecting greenhouse gas emissions, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 3047–3057, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-3047-2015, 2015.

Frey, M., Sha, M. K., Hase, F., Kiel, M., Blumenstock, T., Harig, R., Surawicz, G., Deutscher, N. M., Shiomi, K., Franklin, J., Bösch, H., Chen, J., Grutter, M., Ohyama, H., Sun, Y., Butz, A., Mengistu Tsidu, G., Ene, D., Wunch, D., Cao, Z., Garcia, O., Ramonet, M., Vogel, F., and Orphal, J.: Building the COllaborative Carbon Column Observing Network (COCCON): Long term stability and ensemble performance of the EM27/SUN Fourier transform spectrometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2018-146, in review, 2018.

Gisi, M., Hase, F., Dohe, S., Blumenstock, T., Simon, A., and Keens, A.: XCO2-measurements with a tabletop FTS using solar absorption spectroscopy, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 5, 2969–2980, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-5-2969-2012, 2012.

Hase, F., Frey, M., Blumenstock, T., Groß, J., Kiel, M., Kohlhepp, R., Mengistu Tsidu, G., Schäfer, K., Sha, M. K., and Orphal, J.: Application of portable FTIR spectrometers for detecting greenhouse gas emissions of the major city Berlin, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 3059–3068, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-3059-2015, 2015.

Hase, F., Frey, M., Kiel, M., Blumenstock, T., Harig, R., Keens, A., and Orphal, J.: Addition of a channel for XCO observations to a portable FTIR spectrometer for greenhouse gas measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 2303–2313, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-2303-2016, 2016.

Hedelius, J. K., Viatte, C., Wunch, D., Roehl, C. M., Toon, G. C., Chen, J., Jones, T., Wofsy, S. C., Franklin, J. E., Parker, H., Dubey, M. K., and Wennberg, P. O.: Assessment of errors and biases in retrievals of , , XCO, and from a 0.5 cm−1 resolution solar-viewing spectrometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 3527–3546, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-3527-2016, 2016.

Heinle, L. and Chen, J.: Automated enclosure and protection system for compact solar-tracking spectrometers, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 2173–2185, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-2173-2018, 2018.

IEA (International Energy Agency): World Energy Outlook, IEA Publications, Paris, France ISBN 978926404560-6, 2008.

INSEE: Institut national de la statistique et des etudes economiquem, available at: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques (last access: 1 March 2019), 2016.

IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., and Midgley, P. M., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp., 2013.

IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., Kriemann, B., Savolainen, J., Schlömer, S., von Stechow, C., Zwickel, T., and Minx, J. C., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2014.

Janardanan, R., Maksyutov, S., Oda, T., Saito, M., Kaiser, J. W., Ganshin, A., Stohl, A., Matsunaga, T., Yoshida, Y., and Yokota, T.: Comparing GOSAT observations of localized CO2 enhancements by large emitters with inventory-based estimates, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 3486–3493, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL067843, 2016.

Jones, N.: Troubling milestone for CO2, Nat. Geosci., 6, 589–589, 2013.

Keppel-Aleks, G., Toon, G. C., Wennberg, P. O., and Deutscher, N. M.: Reducing the impact of source brightness fluctuations on spectra obtained by Fourier-transform spectrometry, Appl. Optics, 46, 4774–4779, 2007.

Keppel-Aleks, G., Wennberg, P. O., and Schneider, T.: Sources of variations in total column carbon dioxide, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 3581–3593, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-3581-2011, 2011.

Klappenbach, F., Bertleff, M., Kostinek, J., Hase, F., Blumenstock, T., Agusti-Panareda, A., Razinger, M., and Butz, A.: Accurate mobile remote sensing of XCO2 and XCH4 latitudinal transects from aboard a research vessel, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 5023–5038, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-5023-2015, 2015.

Kort, E. A., Frankenberg, C., Miller, C. E., and Oda, T.: Space-based observations of megacity carbon dioxide, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L17806, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL052738, 2012.

Latoska, A.: Erstellung eines räumlich hoch aufgelösten Emissionsinventar von Luftschadstoffen am Beispiel von Frankreich im Jahr 2005, Master's thesis, Institut für Energiewirtschaft und Rationelle Energieanwendung, Universität Stuttgart, Germany, 2009.

Lauvaux, T., Miles, N. L., Deng, A., Richardson, S. J., Cambaliza, M. O., Davis, K. J., Gaudet, B., Gurney, K. R., Huang, J., O'Keefe, D., and Song, Y.: High-resolution atmospheric inversion of urban CO2 emissions during the dormant season of the Indianapolis Flux Experiment (INFLUX), J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 5213–5236, 2016.

Levin, I., Hammer, S., Eichelmann, E., and Vogel, F. R.: Verification of greenhouse gas emission reductions: the prospect of atmospheric monitoring in polluted areas, Philos. T. R. Soc. A, 369, 1906–1924, 2011.

Menut, L., Bessagnet, B., Khvorostyanov, D., Beekmann, M., Blond, N., Colette, A., Coll, I., Curci, G., Foret, G., Hodzic, A., Mailler, S., Meleux, F., Monge, J.-L., Pison, I., Siour, G., Turquety, S., Valari, M., Vautard, R., and Vivanco, M. G.: CHIMERE 2013: a model for regional atmospheric composition modelling, Geosci. Model Dev., 6, 981–1028, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-6-981-2013, 2013.

Messerschmidt, J., Geibel, M. C., Blumenstock, T., Chen, H., Deutscher, N. M., Engel, A., Feist, D. G., Gerbig, C., Gisi, M., Hase, F., Katrynski, K., Kolle, O., Lavric, J. V., Notholt, J., Palm, M., Ramonet, M., Rettinger, M., Schmidt, M., Sussmann, R., Toon, G. C., Truong, F., Warneke, T., Wennberg, P. O., Wunch, D., and Xueref-Remy, I.: Calibration of TCCON column-averaged CO2: the first aircraft campaign over European TCCON sites, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 10765–10777, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-10765-2011, 2011.

Mitchell, L. E., Lin, J. C., Bowling, D. R., Pataki, D. E., Strong, C., Schauer, A. J., Bares, R., Bush, S. E., Stephens, B. B., Mendoza, D., and Mallia, D.: Long-term urban carbon dioxide observations reveal spatial and temporal dynamics related to urban characteristics and growth, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 2912–2917, 2018.

O'Brien, D. M., Polonsky, I. N., Utembe, S. R., and Rayner, P. J.: Potential of a geostationary geoCARB mission to estimate surface emissions of CO2, CH4 and CO in a polluted urban environment: case study Shanghai, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 4633–4654, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-4633-2016, 2016.

Olivier, J. and Janssens-Maenhout, G.: CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion – 2012 Edition, IEA CO2 report 2012, Part III, Greenhouse-Gas Emissions, ISBN 978-92-64-17475-7, 2012.

Rötzer, T. and Chmielewski, F.-M.: Phenological maps of Europe, Clim. Res., 18, 249–257, 2001.

Schwandner, F. M., Gunson, M. R., Miller, C. E., Carn, S. A., Eldering, A., Krings, T., Verhulst, K. R., Schimel, D. S., Nguyen, H. M., Crisp, D., and O'Dell, C. W.: Spaceborne detection of localized carbon dioxide sources, Science, 358, eaam5782, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam5782, 2017.

Schneider, M. and Hase, F.: Ground-based FTIR water vapour profile analyses, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 2, 609–619, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2-609-2009, 2009.

Staufer, J., Broquet, G., Bréon, F.-M., Puygrenier, V., Chevallier, F., Xueref-Rémy, I., Dieudonné, E., Lopez, M., Schmidt, M., Ramonet, M., Perrussel, O., Lac, C., Wu, L., and Ciais, P.: The first 1-year-long estimate of the Paris region fossil fuel CO2 emissions based on atmospheric inversion, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 14703–14726, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-14703-2016, 2016.

Strong, C., Stwertka, C., Bowling, D. R., Stephens, B. B., and Ehleringer, J. R.: Urban carbon dioxide cycles within the Salt Lake Valley: A multiple-box model validated by observations, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 116, D15307, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD015693, 2011.

Turnbull, J. C., Sweeney, C., Karion, A., Newberger, T., Lehman, S. J., Tans, P. P., Davis, K. J., Lauvaux, T., Miles, N. L., Richardson, S. J., and Cambaliza, M. O.: Toward quantification and source sector identification of fossil fuel CO2 emissions from an urban area: Results from the INFLUX experiment, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 120, 292–312, 2015.

Vogel, F. R., Ishizawa, M., Chan, E., Chan, D., Hammer, S., Levin, I., and Worthy, D. E. J.: Regional non-CO2 greenhouse gas fluxes inferred from atmospheric measurements in Ontario, Canada, J. Integr. Environ. Sci., 9, 41–55, 2012.

Vogel, F. R., Thiruchittampalam, B., Theloke, J., Kretschmer, R., Gerbig, C., Hammer, S., and Levin, I.: Can we evaluate a fine-grained emission model using high-resolution atmospheric transport modelling and regional fossil fuel CO2 observations?, Tellus B, 65, 18681, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v65i0.18681, 2013.

Wunch, D., Toon, G. C., Wennberg, P. O., Wofsy, S. C., Stephens, B. B., Fischer, M. L., Uchino, O., Abshire, J. B., Bernath, P., Biraud, S. C., Blavier, J.-F. L., Boone, C., Bowman, K. P., Browell, E. V., Campos, T., Connor, B. J., Daube, B. C., Deutscher, N. M., Diao, M., Elkins, J. W., Gerbig, C., Gottlieb, E., Griffith, D. W. T., Hurst, D. F., Jiménez, R., Keppel-Aleks, G., Kort, E. A., Macatangay, R., Machida, T., Matsueda, H., Moore, F., Morino, I., Park, S., Robinson, J., Roehl, C. M., Sawa, Y., Sherlock, V., Sweeney, C., Tanaka, T., and Zondlo, M. A.: Calibration of the Total Carbon Column Observing Network using aircraft profile data, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 3, 1351–1362, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-3-1351-2010, 2010.

Wunch, D., Toon, G. C., Blavier, J. F. L., Washenfelder, R. A., Notholt, J., Connor, B. J., Griffith, D. W. T., Sherlock, V., and Wennberg, P. O.: The total carbon column observing network, Philos. T. R. Soc. A, 369, 2087–2112, 2011.

Xueref-Remy, I., Dieudonné, E., Vuillemin, C., Lopez, M., Lac, C., Schmidt, M., Delmotte, M., Chevallier, F., Ravetta, F., Perrussel, O., Ciais, P., Bréon, F.-M., Broquet, G., Ramonet, M., Spain, T. G., and Ampe, C.: Diurnal, synoptic and seasonal variability of atmospheric CO2 in the Paris megacity area, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 3335–3362, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-3335-2018, 2018.