the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Effects of NOx and SO2 on the secondary organic aerosol formation from photooxidation of α-pinene and limonene

Defeng Zhao

Sebastian H. Schmitt

Mingjin Wang

Ismail-Hakki Acir

Ralf Tillmann

Zhaofeng Tan

Anna Novelli

Hendrik Fuchs

Iida Pullinen

Robert Wegener

Franz Rohrer

Jürgen Wildt

Astrid Kiendler-Scharr

Andreas Wahner

Anthropogenic emissions such as NOx and SO2 influence the biogenic secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation, but detailed mechanisms and effects are still elusive. We studied the effects of NOx and SO2 on the SOA formation from the photooxidation of α-pinene and limonene at ambient relevant NOx and SO2 concentrations (NOx: < 1to 20 ppb, SO2: < 0.05 to 15 ppb). In these experiments, monoterpene oxidation was dominated by OH oxidation. We found that SO2 induced nucleation and enhanced SOA mass formation. NOx strongly suppressed not only new particle formation but also SOA mass yield. However, in the presence of SO2 which induced a high number concentration of particles after oxidation to H2SO4, the suppression of the mass yield of SOA by NOx was completely or partly compensated for. This indicates that the suppression of SOA yield by NOx was largely due to the suppressed new particle formation, leading to a lack of particle surface for the organics to condense on and thus a significant influence of vapor wall loss on SOA mass yield. By compensating for the suppressing effect on nucleation of NOx, SO2 also compensated for the suppressing effect on SOA yield. Aerosol mass spectrometer data show that increasing NOx enhanced nitrate formation. The majority of the nitrate was organic nitrate (57–77 %), even in low-NOx conditions (< ∼ 1 ppb). Organic nitrate contributed 7–26 % of total organics assuming a molecular weight of 200 g mol−1. SOA from α-pinene photooxidation at high NOx had a generally lower hydrogen to carbon ratio (H ∕ C), compared to low NOx. The NOx dependence of the chemical composition can be attributed to the NOx dependence of the branching ratio of the RO2 loss reactions, leading to a lower fraction of organic hydroperoxides and higher fractions of organic nitrates at high NOx. While NOx suppressed new particle formation and SOA mass formation, SO2 can compensate for such effects, and the combining effect of SO2 and NOx may have an important influence on SOA formation affected by interactions of biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with anthropogenic emissions.

- Article

(3145 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1737 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Secondary organic aerosols (SOAs) have significant impacts on air quality, human health, and climate change (Hallquist et al., 2009; Kanakidou et al., 2005; Jimenez et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). SOA mainly originates from biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by terrestrial vegetation (Hallquist et al., 2009). Once emitted into the atmosphere, biogenic VOC can undergo reactions with atmospheric oxidants including OH, O3, and NO3 and form SOA. When an air mass enriched in biogenic VOC is transported over an area with substantial anthropogenic emissions or vice versa, the reaction behavior of VOC and SOA formation can be altered due to the interactions of biogenic VOC with anthropogenic emissions such as NOx, SO2, anthropogenic aerosol, and anthropogenic VOC. A number of field studies have highlighted the role of the anthropogenic–biogenic interactions in SOA formation (de Gouw et al., 2005; Goldstein et al., 2009; Hoyle et al., 2011; Worton et al., 2011; Glasius et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2015a; Shilling et al., 2013), which can induce an “anthropogenic enhancement” effect on SOA formation.

Among biogenic VOCs, monoterpenes are important contributors to biogenic SOA due to their high emission rates, high reactivity, and relatively high SOA yield compared to isoprene (Guenther et al., 1995, 2012; Chung and Seinfeld, 2002; Pandis et al., 1991; Griffin et al., 1999; Hoffmann et al., 1997; Zhao et al., 2015b; Carlton et al., 2009). The anthropogenic modulation of the SOA formation from monoterpenes can have important impacts on the regional and global biogenic SOA budget (Spracklen et al., 2011). The influence of various anthropogenic pollutants on SOA formation of monoterpenes has been investigated by a number of laboratory studies (Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2016; Flores et al., 2014; Emanuelsson et al., 2013; Eddingsaas et al., 2012a; Offenberg et al., 2009; Kleindienst et al., 2006; Presto et al., 2005; Ng et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 1992; Pandis et al., 1991; Draper et al., 2015; Han et al., 2016). In particular, NOx and SO2 have been shown to affect SOA formation from monoterpenes.

NOx changes the fate of the RO2 radical formed in VOC oxidation and therefore can change reaction product distribution and aerosol formation. At low NOx, RO2 mainly react with HO2, forming organic hydroperoxides. At high NOx, RO2 mainly react with NO, forming organic nitrate (Hallquist et al., 2009; Ziemann and Atkinson, 2012; Finlayson-Pitts and Pitts Jr., 1999). Some studies found that the SOA yield from α-pinene is higher at lower NOx concentration for ozonolysis (Presto et al., 2005) and photooxidation (Ng et al., 2007; Eddingsaas et al., 2012a; Han et al., 2016; Stirnweis et al., 2017). The decrease in SOA yield with increasing NOx was proposed to be due to the formation of more volatile products like organic nitrate under high-NOx conditions (Presto et al., 2005). In contrast, a recent study found that the suppressing effect of NOx is in large part attributed to the effect of NOx on OH concentration for the SOA from β-pinene oxidation, and, after eliminating the effect of NOx on OH concentration, SOA yield only varies by 20–30 % (Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016). In addition to the effect of NOx on SOA yield, NOx has been found to suppress the new particle formation from VOC directly emitted by Mediterranean trees (mainly monoterpenes; Wildt et al., 2014) and β-pinene (Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016), thereby reducing the condensational sink present during high-NOx experiments.

Regarding the effect of SO2, the SOA yield of α-pinene photooxidation was found to increase with SO2 concentration at high NOx concentrations (SO2: 0–252, NOx: 242–543, α-pinene: 178–255 ppb; Kleindienst et al., 2006) and the increase is attributed to the formation of H2SO4 acidic aerosol. Acidity of seed aerosol was also found to enhance particle yield of α-pinene at high NOx (Offenberg et al., 2009: NOx 100–120, α-pinene 69–160; Han et al., 2016: initial NO ∼ 70 ppb, α-pinene 14–18 ppb). In contrast, Eddingsaas et al. (2012a) found that particle yield increases with aerosol acidity only in high-NO condition (NOx: 800, α-pinene: 20–52 ppb) but is independent of the presence of seed aerosol or aerosol acidity in both high-NO2 condition (NOx 800 ppb) and low NOx (NOx lower than the detection limit of the NOx analyzer). Similarly, at low NOx (initial NO < 0.3, α-pinene ∼ 20 ppb), Han et al. (2016) found that the acidity of seed has no significant effect on SOA yield from α-pinene photooxidation. In addition, SO2 was found to influence the gas-phase oxidation products from α-pinene and β-pinene photooxidation, which is possibly due to the change in the OH ∕ HO2 ratio caused by SO2 oxidation or SO3 directly reacting with organic molecules (Friedman et al., 2016).

While these studies have provided valuable insights into the effects of NOx and SO2 on SOA formation, a number of questions still remain elusive. For example, many studies used very high NOx and SO2 concentrations (up to several hundreds of ppb). High NOx can make the RO2 radical fate dominated by one single pathway (i.e., RO2+ NO or RO2+ NO2), which allows one to investigate the SOA yields and composition under the exclusively high-NO or high-NO2 conditions. Yet, the effects of NOx and SO2 at concentration ranges for ambient anthropogenic–biogenic interactions (sub-ppb to several tens of ppb for NO2 and SO2) have seldom been directly addressed. Moreover, many previous studies on the SOA formation from monoterpene oxidation focus on ozonolysis or do not distinguish OH oxidation and ozonolysis in photooxidation, and only a few studies on OH oxidation have been conducted (Eddingsaas et al., 2012a; Zhao et al., 2015b; McVay et al., 2016; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; Henry et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2007). More importantly, studies that investigated the combined effects of NOx and SO2 are scarce, although they are often co-emitted from anthropogenic sources. According to previous studies, NOx can have a suppressing effect on SOA formation while SO2 can have an enhancing effect. NOx and SO2 might have counteracting or synergistic effects on SOA formation in the ambient atmosphere.

In this study, we investigated the effects of NOx, SO2, and their combining effects on SOA formation from the photooxidation of α-pinene and limonene. α-Pinene and limonene are two important monoterpenes with high emission rates among monoterpenes (Guenther et al., 2012). OH oxidation dominated over ozonolysis in the monoterpene oxidation in this study as determined by measured OH and O3 concentrations. The relative contributions of RO2 loss reactions at low NOx and high NOx were quantified using measured HO2, RO2, and NO concentrations. The effects on new particle formation, SOA yield, and aerosol chemical composition were examined. We used ambient relevant NOx and SO2 concentrations so that the results can shed lights on the mechanisms of interactions of biogenic VOC with anthropogenic emissions in the real atmosphere.

2.1 Experimental setup and instrumentation

The experiments were performed in the SAPHIR chamber (simulation of atmospheric photochemistry in a large reaction chamber) at Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany. The details of the chamber have been described before (Rohrer et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2015a, b). Briefly, it is a 270 m3 Teflon chamber using natural sunlight for illumination. It is equipped with a louvre system to switch between light and dark conditions. The physical parameters for chamber running such as temperature and relative humidity (RH) were recorded. The solar irradiation was characterized and the photolysis frequency was derived (Bohn et al., 2005; Bohn and Zilken, 2005).

Gas- and particle-phase species were characterized using various instruments. OH, HO2, and RO2 concentrations were measured using a laser-induced fluorescence system with details described by Fuchs et al. (2012). OH was formed via HONO photolysis, which was produced from a photolytic process on the Teflon chamber wall (Rohrer et al., 2005). From OH concentration, OH dose, the integral of OH concentration over time, was calculated in order to better compare experiments with different OH levels. For example, experiments at high NOx in this study generally had higher OH concentrations due to the faster OH production by recycling of HO2• and RO2• to OH. The VOCs were characterized using a proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTR-ToF-MS) and gas chromatography mass spectrometer (GC-MS). NOx, O3, and SO2 concentrations were characterized using a NOx analyzer (Eco Physics TR480), an O3 analyzer (Ansyco, model O341M), and an SO2 analyzer (Thermo Systems 43i), respectively. O3 was formed in photochemical reactions since NOx, even in trace amount (< ∼ 1 ppbV), was present in this study. More details of the instrumentation are described before (Zhao et al., 2015b).

The number and size distribution of particles were measured using a condensation particle counter (CPC; TSI, model 3786) and a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS; TSI, DMA 3081/CPC 3785). From particle number measurement, the nucleation rate (J2.5) was derived from the number concentration of particles larger than 2.5 nm as measured by CPC. Particle chemical composition was measured using a high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc.). From the AMS data, the oxygen to carbon ratio (O ∕ C), hydrogen to carbon ratio (H ∕ C), and nitrogen to carbon ratio (N ∕ C) were derived using a method derived in the literature (Aiken et al., 2007, 2008). An update procedure to determine the elemental composition is reported by Canagaratna et al. (2015), showing the O ∕ C and H ∕ C derived from the method of Aiken et al. (2008) may be underestimated. The H ∕ C and O ∕ C were also derived using the newer approach by Canagaratna et al. (2015) and compared with the data derived from the Aiken et al. (2007) method. The H ∕ C values derived using the Canagaratna et al. (2015) method strongly correlated with the values derived using the Aiken et al. (2007) method (Fig. S1 in the Supplement) and just increased by 27 % as suggested by Canagaratna et al. (2015). Similar results were found for O ∕ C and there was just a difference of 11 % in O ∕ C. Since only the relative difference in elemental composition of SOA is studied here, only the data derived using the Aiken et al. (2007) method are shown as the conclusion was not affected by the methods chosen. The fractional contributions of organics in the signals at 44 and 43 to total organics (f44 and f43, respectively) were also derived.

SOA yields were calculated as the ratio of organic aerosol mass formed to the amount of VOC reacted. The mass concentration of organic aerosol was derived using the total aerosol volume concentration measured by SMPS multiplied by the volume fraction of organics with a density of 1 g cm−3 to better compare with previous literature. In the experiments with added SO2, sulfuric acid was formed upon photooxidation and partly neutralized by background ammonia, which was introduced into the chamber mainly due to humidification. The volume fraction of organics was derived based on volume additivity using the mass of organics and ammonium sulfate and ammonium bisulfate from AMS and their respective density (1.32 g cm−3 for organic aerosol from one of our previous studies (Flores et al., 2014) and the literature (Ng et al., 2007) and ∼ 1.77 g cm−3 for ammonium sulfate and ammonium bisulfate). According to the calculations based on the E-AIM model (Clegg et al., 1998; Wexler and Clegg, 2002; http://www.aim.env.uea.ac.uk/aim/aim.php), there was no aqueous phase formed at the relative humidity in the experiments of this study. The average RH for the period of monoterpene photooxidation was 28–34 % except for one experiment with average RH of 42 % RH. The organic aerosol concentration was corrected for the particle wall loss and dilution loss using the method described in Zhao et al. (2015b).

2.2 Experimental procedure

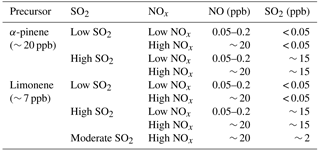

The SOA formation from α-pinene and limonene photooxidation was investigated at different NOx and SO2 levels. Four types of experiments were done: with neither NOx nor SO2 added (referred to as “low NOx, low SO2”), with only NOx added (∼ 20 ppb NO, referred to as “high NOx, low SO2”), with only SO2 added (∼ 15 ppb, referred to as “low NOx, high SO2”), and with both NOx and SO2 added (∼ 20 ppb NO and ∼ 15 ppb SO2, referred to as “high NOx, high SO2”). For low-NOx conditions, background NO concentrations were around 0.05–0.2 ppb, and background NO was mainly from a photolytic process of Teflon as chamber wall. (Rohrer et al., 2005). For low-SO2 conditions, background SO2 concentrations were below the detection limit of the SO2 analyzer (0.05 ppb). In some experiments, a lower level of SO2 (2 ppb, referred to as “moderate SO2”) was used to test the effect of SO2 concentration. An overview of the experiments is shown in Table 1.

In a typical experiment, the chamber was humidified to ∼ 75 % RH first, and then VOC and NO, if applicable, were added to the chamber. Then the roof was opened to start photooxidation. In the experiments with SO2, SO2 was added and the roof was opened to initialize nucleation first and then VOC was added. The particle number concentration caused by SO2 oxidation typically reached several tens of thousands cm−3 (see Fig. 2 high-SO2 cases) and, after VOC addition, no further nucleation occurred. Adding SO2 first and initializing nucleation by SO2 photooxidation ensured that enough nucleating particles were present when VOC oxidation started. SO2 concentration decayed slowly in the experiments with SO2 added and most of the SO2 was still left (typically around 8 ppb from initial 15 ppb) at the end of an experiment due to its low reactivity with OH. Typical SO2 time series in high-SO2 experiments are shown in Fig. S2. The detailed conditions of the experiments are shown in Table S1 in the Supplement. The experiments of α-pinene and limonene photooxidation were designed to keep the initial OH reactivity and thus OH loss rate constant so that the OH concentrations of these experiments were more comparable. Therefore, the concentration of limonene was around one-third of the concentration of α-pinene due to the higher OH reactivity of limonene.

2.3 Wall loss of organic vapors

The loss of organic vapors on chamber walls can influence SOA yield (Kroll et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2014; Ehn et al., 2014; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; McVay et al., 2016; Nah et al., 2016; Matsunaga and Ziemann, 2010; Ye et al., 2016; Loza et al., 2010). The wall loss rate of organic vapors in our chamber was estimated by following the decay of organic vapor concentrations after photooxidation was stopped in the experiments with low particle surface area (∼ 5 × 10−8 cm2 cm−3) and thus low condensational sink on particles. Such method is similar to the method used in previous studies (Ehn et al., 2014; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; Krechmer et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015). A high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-CIMS, Aerodyne Research Inc.) with nitrate ion source (15NO was used to measure semi/low-volatility organic vapors. The details of the instrument were described in our previous studies (Ehn et al., 2014; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016). The decay of vapors started from the time when the roof of the chamber was closed. The data were acquired at a time resolution of 4 s. A typical decay of low-volatility organics is shown in Fig. S3 and the first-order wall loss rate was determined to be around 6 × 10−4 s−1.

The SOA yield was not directly corrected for the vapor wall loss, but the influence of vapor wall loss on SOA yield was estimated using the method in the study of Sarrafzadeh et al. (2016) and the details of the method are described therein. Briefly, particle surface and chamber walls competed for the vapor loss (condensation) and the condensation on particles led to particle growth. The fraction of organic vapor loss to particles in the sum of the vapor loss to chamber walls plus the vapor loss to particles (Fp) was calculated. The vapor loss to chamber walls was derived using the wall loss rate. The vapor loss to particles was derived using particle surface area concentration, molecular velocity, and an accommodation coefficient αp (Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016). 1∕Fp (fcorr) provides the correction factor to obtain the “real” SOA yield. fcorr is a function of the particle surface area concentration and accommodation coefficient as shown in Fig. S4. Here a range of 0.1–1 for αp was used, which is generally in line with the ranges of αp found by Nah et al. (2016) by fitting a vapor–particle dynamic model to experimental data. At a given αp, the higher particle surface area, the lower fcorr, and the lower the influence of vapor wall loss are because most vapors condense on particle surface and vice versa. At a given particle surface area, fcorr decreases with αp because at higher αp a larger fraction of vapors condenses on particles. An average molecular weight of 200 g mol−1 was used to estimate the influence of vapor wall loss. For the aerosol surface area range in most of the experiments in this study (larger than 3 × 10−6 cm2 cm−3), fcorr is less than 1.4 (Fig. S4) and thus the influence of vapor wall loss on SOA yield was relatively small (< ∼ 40 %). Yet, for the experiments at high NOx and low SO2 for α-pinene and limonene, the influence of vapor wall loss on SOA can be high due to the low particle surface area, especially at lower αp. We did not directly correct SOA yield for vapor wall loss because the correction factor (fcorr) curve in the low surface area range is very steep and has very large uncertainties (Fig. S4). In addition, αp also has uncertainties and may depend on the identity of each condensable compound.

3.1 Chemical scheme: VOC oxidation pathway and RO2 fate

In the photooxidation of VOC, OH and O3 often coexist and both contribute to VOC oxidation because O3 formation in chamber studies is often unavoidable during photochemical reactions of VOC even in the presence of trace amount of NOx. In order to study the mechanism of SOA formation, it is helpful to isolate one oxidation pathway from the other. In this study, the reaction rates of OH and ozone with VOC are quantified using measured OH and O3 concentrations multiplied by rate constants (time series of VOC, OH, and O3 are shown in Fig. S5). Typical OH and O3 concentrations in an experiment were around (1–15) × 106 molecules cm−3 and 0–50 ppb, respectively, depending on the VOC and NOx concentrations added. For all the experiment in this study, the VOC loss was dominated by OH oxidation over ozonolysis (see Fig. S6 as an example). The relative importance of the reaction of OH and O3 with monoterpenes was similar in the low-NOx and high-NOx experiments. At high NOx, OH was often higher while more O3 was also produced. The dominant role of OH oxidation in VOC loss makes the chemical scheme simple and it is easier to interpret than cases when both OH oxidation and ozonolysis are important.

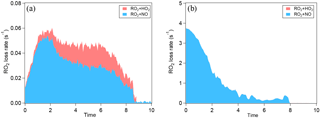

Figure 1Typical loss rate of RO2 by RO2+NO and RO2+ HO2 in the low-NOx (a) and the high-NOx (b) conditions of this study. The experiments at low SO2 are shown. The RO2+ HO2 rate is stacked on the RO2+NO rate. Note the different scales for RO2 loss rate in panel (a) and (b). In panel (b), the contribution of RO2+ HO2 is very low and barely noticeable.

As mentioned above, RO2 fate, i.e., the branching of RO2 loss among different pathways, has an important influence on the product distribution and thus on SOA composition, physicochemical properties, and yields. RO2 can react with NO, HO2, and RO2s or isomerize. The fate of RO2 mainly depends on the concentrations of NO, HO2, and RO2. Here, the loss rates of RO2 via different pathways were quantified using the measured HO2, NO, and RO2 concentrations and the rate constants based on the MCM3.3 (Jenkin et al., 1997; Saunders et al., 2003; http://mcm.leeds.ac.uk/MCM/). Measured HO2 and RO2 concentrations are shown in Fig. S7 as an example and the relative importance of different RO2 reaction pathways is compared in Fig. 1, which is similar for both α-pinene and limonene oxidation. In the low-NOx conditions of this study, RO2+NO dominated the RO2 loss rate in the beginning of an experiment (Fig. 1a). The trace amount of NO (up to ∼ 0.2 ppbV) was from the photolysis of HONO, which was continuously produced from a photolytic process on chamber walls throughout an experiment (Rohrer et al., 2005). But later in the experiment, RO2+ HO2 contributed a significant fraction (up to ∼ 40 %) to RO2 loss because of increasing HO2 concentration and decreasing NO concentration. In the high-NOx conditions, RO2+ NO overwhelmingly dominated the RO2 loss rate (Fig. 1b), and, with the decrease in NO in an experiment, the total RO2 loss rate decreased substantially (Fig. 1b). Since the main products of RO2+ HO2 are organic hydroperoxides, more organic hydroperoxides relative to organic nitrates are expected in the low-NOx conditions here. The loss rate of RO2+RO2 was estimated to be ∼ 10−4 s−1 using a reaction rate constant of 2.5 × 10−13 molecules−1 cm3 s−1 (Ziemann and Atkinson, 2012). This contribution is negligible compared to other pathways in this study, although the reaction rate constants of RO2+ RO2 are highly uncertain and may depend on specific RO2 (Ziemann and Atkinson, 2012). Note that the RO2 fate in the low and high-NOx conditions quantified here is further used in the discussion below since the information of the RO2 fate is important for data interpretation of experiments conducted at different NOx levels (Wennberg, 2013).

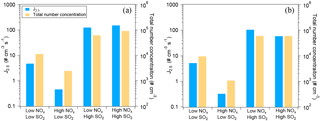

3.2 Effects of NOx and SO2 on new particle formation

The effects of NOx and SO2 on new particle formation from α-pinene oxidation are shown in Fig. 2a. In low-SO2 conditions, both the total particle number concentration and nucleation rate at high NOx were lower than those at low NOx, indicating NOx suppressed the new particle formation. The suppressing effect of NOx on new particle formation was in agreement with the findings of Wildt et al. (2014). This suppression is considered to be caused by the increased fraction of RO2+ NO reaction, decreasing the importance of RO2+ RO2 permutation reactions. RO2+ RO2 reaction products are believed to be involved in the new particle formation (Wildt et al., 2014; Kirkby et al., 2016) and initial growth of particles by forming higher molecular weight products such as highly oxidized multifunctional molecules (HOMs) and their dimers and trimers (Ehn et al., 2014; Kirkby et al., 2016). Although the contribution of RO2+ RO2 reaction to the total RO2 loss is negligible, it can contribute a lot to the compounds responsible for nucleation such as dimers and trimers. Generally, organic nitrates and primary organic peroxides (from RO2(C10)+ HO2) are not expected to be the main compounds responsible for nucleation since, although the volatility of these compounds is low (see below Sect. 3.3.1), it is likely not low enough to nucleate.

In high-SO2 conditions, the nucleation rate and total number concentrations were high, regardless of NOx levels. The high concentration of particles was attributed to the new particle formation induced by H2SO4 alone formed by SO2 oxidation since the new particle formation occurred before VOC addition. The role of H2SO4 in new particle formation has been well studied in previous studies (Berndt et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012; Sipila et al., 2010; Kirkby et al., 2011; Almeida et al., 2013).

Similar suppression of new particle formation by NOx and enhancement of new particle formation by SO2 photooxidation were found for limonene oxidation (Fig. 2b).

3.3 Effects of NOx and SO2 on SOA mass yield

3.3.1 Effect of NOx

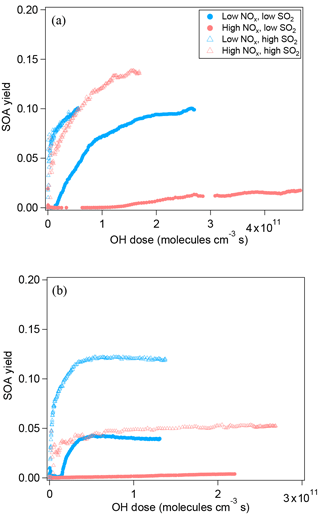

Figure 3a shows SOA yield at different NOx for α-pinene oxidation. In order to make different experiments more comparable, the SOA yield is plotted as a function of OH dose instead of reaction time. In low-SO2 conditions, NOx not only suppressed the new particle formation but also suppressed SOA mass yield. Because NOx suppressed new particle formation, the suppression of the SOA yield could be attributed to the lack of new particles as seed, and thus the lack of condensational sink, or to the decrease in condensable organic materials. We further found that when new particle formation was already enhanced by added SO2, the SOA yield at high NOx was comparable to that at low NOx and the difference in SOA yield between high NOx and low NOx was much smaller (Fig. 3a). This finding can be attributed to two possible explanations. Firstly, NOx did not significantly suppress the formation of low-volatility condensable organic materials, although NOx obviously suppressed the formation of products for nucleation. Secondly, NOx did suppress the formation of low-volatility condensable organic materials via forming potentially more volatile compounds and, in addition to that, the suppressed formation of condensable organic materials was compensated for by the presence of SO2, resulting in comparable SOA yield. Organic nitrates are a group of compounds formed at high NOx, which have been proposed to be more volatile (Presto et al., 2005; Kroll et al., 2006). However, many organic nitrates formed by photooxidation in this study were highly oxidized organic molecules containing multifunctional groups besides nitrate group (C7−10H9−15NO8−15, HOMs nitrate). These compounds are expected to have low volatility and they are found to have an uptake coefficient on particles of ∼ 1 (Pullinen et al., 2018). Therefore, the suppressing effect of NOx on SOA yield was mostly likely due to suppressed nucleation, i.e., the lack of particle surface as condensational sink. Due to the low particle surface area, the wall loss of condensable vapors in the experiment at high NOx and low SO2 was large (as shown by the large fcorr in Fig. S4) and therefore SOA mass yield was suppressed. If vapor wall loss is considered, the difference between the SOA yield at high NOx and at low NOx under low-SO2 conditions will be much reduced, as we found for high-SO2 cases (Fig. 3a). Under high-SO2 conditions, the influence of vapor wall loss on the difference in SOA yield between high NOx and low NOx was minor (1–8 %, Fig. S4) due to the larger particle surface area.

Figure 3SOA yield of the photooxidation of α-pinene (a) and limonene (b) in different NOx and SO2 conditions.

For limonene oxidation, similar results of NOx suppressing the particle mass formation have been found in low-SO2 conditions (Fig. 3b). Yet, in high-SO2 conditions, the SOA yield from limonene oxidation at high NOx was still significantly lower than that at low NOx, which is different from the findings for α-pinene SOA. The cause of this difference is currently unknown. Our data of SOA yield suggest that the products formed from limonene oxidation at high NOx seemed to have higher average volatility than that at low NOx.

The suppression of SOA mass formation by NOx under low-SO2 conditions agrees with previous studies (Eddingsaas et al., 2012a; Wildt et al., 2014; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; Hatakeyama et al., 1991). For example, it was found that high concentration of NOx (tens of ppb) suppressed mass yield of SOA formed from photooxidation of β-pinene, α-pinene, and VOC emitted by Mediterranean trees (Wildt et al., 2014; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016). And on the basis of the results by Eddingsaas et al. (2012a), the SOA yield at high NOx (referred to as high NO by the authors) is lower than at low NOx in the absence of seed aerosol.

Our finding that the difference in SOA yield between high-NOx and low-NOx conditions was highly reduced at high SO2 is also in line with the findings of some previous studies using seed aerosols (Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; Eddingsaas et al., 2012a). For example, Sarrafzadeh et al. (2016) found that, in the presence of seed aerosol, the suppressing effect of NOx on the SOA yield from β-pinene photooxidation is substantially diminished and SOA yield only decreases by 20–30 % in the NOx range of < 1 to 86 ppb at constant OH concentrations. The data by Eddingsaas et al. (2012a) also showed that, in the presence of seed aerosol, the difference in the SOA yield between low NOx and high NOx is much decreased. However, our finding is in contrast with the findings in other studies (Presto et al., 2005; Ng et al., 2007; Han et al., 2016; Stirnweis et al., 2017), who reported much lower SOA yield at high NOx than at low NOx in the presence of seed. The different findings in these studies from ours may be attributed to the difference in the reaction conditions such as VOC oxidation pathways (OH oxidation vs. ozonolysis), VOC and NOx concentration ranges, NO ∕ NO2, OH concentrations, and organic aerosol loading, which all affect SOA yield. The reaction conditions of this study often differ from those described in the literature (see Table S2).

The difference in these conditions can result in both different apparent dependence on specific parameters and the varied SOA yield. For example, SOA yield from α-pinene photooxidation at low NOx in this study appeared to be much lower than that in Eddingsaas et al. (2012a). The difference between the SOA yield in this study and some of previous studies and between the values in the literature can be attributed to several reasons: (1) RO2 fates may be different. For example, in our study at low NOx, RO2+ NO account for a large fraction of RO2 loss while in Eddingsaas et al. (2012a) RO2+ HO2 is the dominant pathway of RO2 loss. This difference in RO2 fates may affect oxidation products' distribution. (2) The organic aerosol loading of this study is much lower than that of some previous studies (e.g., Eddingsaas et al., 2012a; see Fig. S9). SOA yields in this study were also plotted versus organic aerosol loading to better compare with previous studies (Figs. S8 and S9). (3) The total particle surface area in this study may also differ from previous studies, which may influence the apparent SOA yield due to vapor wall loss (the total particle surface area is often not reported in many previous studies to compare with). (4) RH of this study is different from many previous studies, which often used very low RH (< 10 %). It is important to emphasize that reaction conditions including the NOx as well as SO2 concentration range and RH in this study were chosen to be relevant to the anthropogenic–biogenic interactions in the ambient atmosphere. In addition, the difference in the organic aerosol density used in yield calculation should be taken into account. In this study, SOA yield was derived using a density of 1 g cm−3 to better compare with many previous studies (e.g., Henry et al., 2012), while in some other studies SOA yield was derived using different density (e.g., 1.32 g cm−3 in Eddingsaas et al., 2012a).

3.3.2 Effect of SO2

For both α-pinene and limonene, SO2 was found to enhance the SOA mass yield at given NOx levels, especially for the high-NOx cases (Fig. 3). The enhancing effect of SO2 on particle mass formation can be attributed to two reasons. Firstly, SO2 oxidation induced new particle formation, which provided more surface and volume for further condensation of organic vapors. This is consistent with the finding that the enhancement of SOA yield by SO2 was more significant at high NOx when the enhancement in nucleation was also more significant. Secondly, H2SO4 formed by photooxidation of SO2 can enhance SOA formation via acid-catalyzed heterogeneous uptake, an important SOA formation pathway initially found from isoprene photooxidation (Jang et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2012; Surratt et al., 2007) and later also in the photooxidation of other compounds such as anthropogenic VOC (Chu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). For the products from monoterpene oxidation, such an acid-catalyzed effect may also occur (Northcross and Jang, 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Lal et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2006; Ding et al., 2011; Iinuma et al., 2009) and, in this study, the particles were acidic with the molar ratio of NH to SO around 1.5–1.8, although no aqueous phase was formed.

We found that the SOA yield in the limonene oxidation at a moderate SO2 level (2 ppb) was comparable to the yield at high SO2 (15 ppb) when similar particle number concentrations in both cases were formed. Both yields were significantly higher than the yield at low SO2 (< 0.05 ppb, see Fig. S10). This comparison suggests that the effect on enhancing new particle formation by SO2 seems to be more important compared to the particle acidity effect. The role of SO2 in new particle formation is similar to adding seed aerosol and providing particle surface for organics to condense. Artificially added seed aerosol has been shown to enhance SOA formation from α-pinene and β-pinene oxidation (Ehn et al., 2014; Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016; Eddingsaas et al., 2012a). In some other studies, it was found that the SOA yield from α-pinene oxidation is independent of initial seed surface area (McVay et al., 2016; Nah et al., 2016). The difference in the literature may be due to the range of the total surface area of particles, reaction conditions, and chamber setup. For example, the peak particle-to-chamber surface ratio for α-pinene photooxidation in this study was 7.7 × 10−5 at high NOx and low SO2, much lower than the aerosol surface area range in the studies by Nah et al. (2016) and McVay et al. (2016). A lower particle-to-chamber surface ratio can lead to a larger fraction of organics lost on chamber walls. Hence, providing additional particle surface by adding seed particles can increase the condensation of organics on particles and thus increase SOA yield. However, once the surface area is high enough to inhibit condensation of vapors on chamber walls, further enhancement of particle surface will not significantly enhance the yield (Sarrafzadeh et al., 2016).

As mentioned above, the SOA yield at high NOx and low SO2 was significantly suppressed due to vapor wall loss. If the influence of vapor wall loss is considered, the SOA yield at high NOx and low SO2 will be much higher and thus the observed enhancement of SOA yield by SO2 under high-NOx conditions will be much less pronounced. Under low-NOx conditions, the influence of vapor wall loss on the difference in SOA yield between high SO2 and low SO2 was minor (1–7 % for α-pinene and 5–32 % for limonene, see Fig. S4) due to the larger particle surface area.

Particle acidity may also play a role in affecting the SOA yield in the experiments with high SO2. Particle acidity was found to enhance the SOA yield from α-pinene photooxidation at high-NOx (Offenberg et al., 2009) and high-NO conditions (Eddingsaas et al., 2012a). Yet, in low-NOx condition, particle acidity was reported to have no significant effect on the SOA yield from α-pinene photooxidation (Eddingsaas et al., 2012a; Han et al., 2016). According to these findings, at low NOx the enhancement of SOA yield in this study is attributed to the effect of facilitating nucleation and providing more particle surface by SO2 photooxidation. At high NOx, the effect on enhancing new particle formation by SO2 photooxidation seems to be more important, although the effect of particle acidity resulted from SO2 photooxidation may also play a role.

SO2 has been proposed to also affect gas-phase chemistry of organics by changing the HO2 ∕ OH or forming SO3 (Friedman et al., 2016). In this study, the effect of SO2 on gas-phase chemistry of organics was not significant because of the much lower reactivity of SO2 with OH compared with α-pinene and limonene (Atkinson et al., 2004, 2006; Atkinson and Arey, 2003) and the low OH concentrations (2–3 orders of magnitude lower than those in the study by Friedman et al., 2016). Moreover, reactions of RO2 with SO2 were also not important because the reaction rate constant is very low (< 10−14 molecule−1 cm3 s−1; Lightfoot et al., 1992; Berndt et al., 2015). In addition, from the AMS data of SOA formed at high SO2 no significant organic fragments containing sulfur were found. Also the fragment CH3SO from organic sulfate suggested by Farmer et al. (2010) was not detected in our data. The absence of organic sulfate tracers is likely due to the lack of aqueous phase in aerosol particles in this study. Therefore, the influence of SO2 on gas-phase chemistry of organics and further on SOA yield via affecting gas-phase chemistry is not important in this study.

The presence of high SO2 enhanced the SOA mass yield at high-NOx conditions, which was even comparable with the SOA yield at low NOx for α-pinene oxidation. This finding indicates that the suppressing effect of NOx on SOA mass formation was compensated for to a large extent by the presence of SO2. This has important implications for SOA formation affected by anthropogenic–biogenic interactions in the real atmosphere when SO2 and NOx often coexist in relatively high concentrations as discussed below.

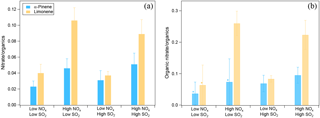

3.4 Effects of NOx and SO2 on SOA chemical composition

The effects of NOx and SO2 on SOA chemical composition were analyzed on the basis of AMS data. We found that NOx enhanced nitrate formation. The ratio of the mass of nitrate to organics was higher at high NOx than at low NOx regardless of the SO2 level, and similar trends were found for SOA from α-pinene and limonene oxidation (Fig. 4a). Higher nitrate to organics ratios were observed for SOA from limonene at high NOx, which is mainly due to the lower VOC ∕ NOx ratio resulted from the lower concentrations of limonene (7 ppb) compared to α-pinene (20 ppb) (see Table 1). Overall, the mass ratios of nitrate to organics ranged from 0.02 to 0.11 considering all the experiments in this study.

Figure 4(a) The ratio of nitrate mass concentration to organics mass in different NOx and SO2 conditions. The average ratios of nitrate to organics during the reaction are shown and error bars indicate the standard deviations. (b) The fraction of organic nitrate to total organics in different NOx and SO2 conditions calculated using a molecular weight of 200 g mol−1 for organic nitrate. The average fractions during the reaction are shown and error bars indicate the standard deviations. In panel (b), * indicates the experiments where the ratios of NO to NO+ were too noisy to derive a reliable fraction of organic nitrate. For these experiments, 50 % of total nitrate was assumed to be organic nitrate and the error bars show the range when 0 to 100 % of nitrate is assumed to be organic nitrate.

Nitrate formed can be either inorganic (such as HNO3 from the reaction of NO2 with OH) or organic (from the reaction of RO2 with NO). The ratio of NO ( 46) to NO+ ( 30) in the mass spectra detected by AMS can be used to differentiate whether nitrate is organic or inorganic (Fry et al., 2009; Rollins et al., 2009; Farmer et al., 2010; Kiendler-Scharr et al., 2016). Organic nitrate was considered to have a NO ∕ NO+ of ∼ 0.1 and inorganic NH4NO3 had a NO ∕ NO+ of ∼ 0.31 with the instrument used in this study as determined from calibration measurements. In this study, NO ∕ NO+ ratios ranged from 0.14 to 0.18, closer to the ratio of organic nitrate. The organic nitrate was estimated to account for 57–77 % (molar fraction) of total nitrate considering both the low-NOx and high-NOx conditions. This indicates that nitrate was mostly organic nitrate, even at low NOx in this study.

In order to determine the contribution of organic nitrate to total organics, we estimated the molecular weight of organic nitrates formed by α-pinene and limonene oxidation to be 200–300 g mol−1, based on reaction mechanisms (Eddingsaas et al., 2012b, and MCM v3.3 at http://mcm.leeds.ac.uk/MCM). We assumed a molecular weight of 200 g mol−1 in order to make our results comparable to the field studies which used similar molecular weight (Kiendler-Scharr et al., 2016). For this value, the organic nitrate compounds were estimated to account for 7–26 % of the total organics mass as measured by AMS in SOA. Organic nitrate fraction in total organics was within the range of values found in a field observation in southeast US (5–12 % in summer and 9–25 % in winter depending on the molecular weight of organic nitrate) using AMS (Xu et al., 2015b) and particle organic nitrate content derived from the sum of speciated organic nitrates (around 1–17 % considering observed variability and 3 and 8 % on average in the afternoon and at night, respectively; Lee et al., 2016). Note that the organic nitrate fraction observed in this study was lower than the mean value (42 %) for a number of European observation stations when organic nitrate is mainly formed by the reaction of VOC with NO3 (Kiendler-Scharr et al., 2016).

Moreover, we found that the contribution of organic nitrate to total organics (calculated using a molecular weight of 200 g mol−1 for organic nitrate) was higher at high NOx (Fig. 4b), although in some experiments the ratios of NO to NO+ were too noisy to derive a reliable fraction of organic nitrate. This result is consistent with the reaction scheme that at high NOx almost all the RO2 loss was switched to the reaction with NO, which is expected to enhance the organic nitrate formation. In addition to organic nitrate, the ratio of nitrogen to carbon atoms (N ∕ C) was also found to be higher at high NOx (Fig. S11). But after considering the nitrate functional group separately, the N ∕ C ratio was very low, generally < 0.01, which indicates that a majority of the organic nitrogen existed in the form of organic nitrate.

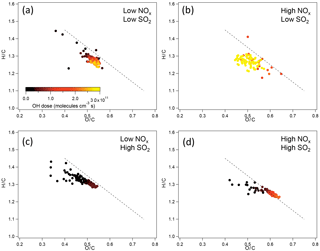

The chemical composition of organic components of SOA in terms of H ∕ C and O ∕ C ratios at different NOx and SO2 levels was further compared. For SOA from α-pinene photooxidation, in low-SO2 conditions, no significant difference in H ∕ C and O ∕ C was found between SOA formed at low NOx and at high NOx within the experimental uncertainties (Fig. 5). The variability of H ∕ C and O ∕ C at high NOx is large, mainly due to the low particle mass and small particle size. In high-SO2 conditions, SOA formed at high NOx had the higher O ∕ C and lower H ∕ C, which indicates that SOA components had higher oxidation state. The higher O ∕ C at high NOx than at low NOx is partly due to the higher OH dose at high NOx, although even at the same OH dose O ∕ C at high NOx was still slightly higher than at low NOx in high-SO2 conditions.

For the SOA formed from limonene photooxidation, no significant difference in the H ∕ C and O ∕ C was found between different NOx and SO2 conditions (Fig. S12), which is partly due to the low signal resulting from low particle mass and small particle size in high-NOx conditions.

Figure 5H ∕ C and O ∕ C ratio of SOA from photooxidation of α-pinene in different NOx and SO2 conditions. (a) Low NOx, low SO2; (b) high NOx, low SO2; (c) low NOx, high SO2; (d) high NOx, high SO2. The black dashed line corresponds to the slope of −1.

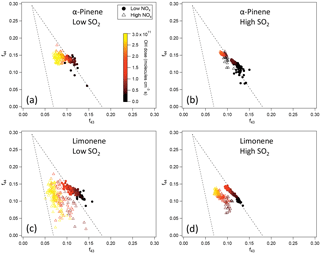

Figure 6f44 and f43 of SOA from the photooxidation of α-pinene and limonene in different NOx and SO2 conditions. (a) α-Pinene, low SO2; (b) α-pinene, high SO2; (c) limonene, low SO2; (d) limonene, high SO2. Note that in the low-SO2, high-NOx condition (c), the AMS signal of SOA from limonene oxidation was too low to derive reliable information due to the low particle mass concentration and small particle size. Therefore, the data for high NOx in (c) show an experiment with moderate SO2 (2 ppb) and high NOx instead.

Due to the high uncertainties for some of the H ∕ C and O ∕ C data, the chemical composition was further analyzed using f44 and f43 since f44 and f43 are less noisy (Fig. 6). For both α-pinene and limonene, SOA formed at high NOx generally had lower f43. Because f43 generally correlates with H ∕ C in organic aerosol (Ng et al., 2011), lower f43 is indicative of lower H ∕ C, which is consistent with the lower H ∕ C at high NOx observed for SOA from α-pinene oxidation in high-SO2 conditions (Fig. 5). The lower f43 at high NOx was evidenced in the oxidation of α-pinene based on the data in a previous study (Chhabra et al., 2011). The lower H ∕ C and f43 are likely to be related to the reaction pathways. According to the reaction mechanism mentioned above, at low NOx a significant fraction of RO2 reacted with HO2, forming hydroperoxides, while at high NOx almost all RO2 reacted with NO, forming organic nitrates. Compared with organic nitrates, hydroperoxides have a higher H ∕ C ratio. The same mechanism also caused higher organic nitrate fraction at high NOx, as discussed above.

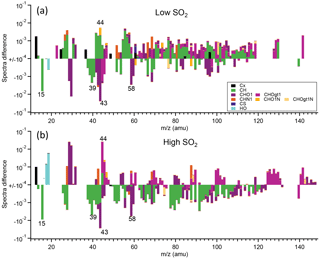

Detailed mass spectra of SOA were compared, shown in Fig. 7. For α-pinene, in high-SO2 conditions, mass spectra of SOA formed at high NOx generally had higher intensity for CHOgt1 (“gt1” means greater than 1) family ions, such as CO (m∕z 44), but lower intensity for CH family ions, such as C2H (m∕z 15) and C3H (m∕z 39; Fig. 7b), than at low NOx. In low-SO2 conditions, such difference is not apparent (Fig. 7a), partly due to the low signal from AMS for SOA formed at high NOx as discussed above. For both the high-SO2 and low-SO2 cases, mass spectra of SOA at high NOx show higher intensity of CHN1 family ions. This is also consistent with the higher N ∕ C ratio shown above. For SOA from limonene oxidation, SOA formed at high NOx had a lower mass fraction at m∕z 15 (C2H, 28 (CO+), 43 (C2H3O+), and 44 (CO and a higher mass fraction at m∕z 27 (CHN+, C2H, 41 (C3H, 55 (C4H, and 64 (C4O+) than at low NOx (Fig. S13). It seems that overall mass spectra of the SOA from limonene formed at high NOx had higher intensity for CH family ions, but lower intensity for CHO1 family ions than at low NOx. Note that the differences in these m∕z values were based on the average spectra during the whole reaction period and may not reflect the chemical composition at a certain time.

Figure 7The difference in the mass spectra of organics of SOA from α-pinene photooxidation between high-NOx and low-NOx conditions (high NOx–low NOx). SOA was formed at low SO2 (a) and high SO2 (b). The different chemical families of high-resolution mass peaks are stacked at each unit mass m∕z (“gt1” means greater than 1). The mass spectra were normalized to the total organic signals. Note the log scale of the y axis and only the data with absolute values large than 10−4 are shown.

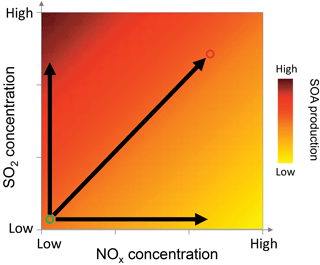

Figure 8Conceptual schematic showing how NOx and SO2 concentrations affect biogenic SOA mass production. The darker colors indicate higher SOA production. The circle on the bottom left corner indicates biogenic cases and the circle on the right top corner indicates the anthropogenic cases. And the horizontal and vertical arrows indicate the effect of NOx and SO2 alone. The overall effects on SOA production depend on specific NOx, SO2 concentrations, and VOC concentrations and speciation.

We investigated the SOA formation from the photooxidation of α-pinene and limonene under different NOx and SO2 conditions, when OH oxidation was the dominant oxidation pathway of monoterpenes. The fate of RO2 was regulated by varying NOx concentrations. We confirmed that NOx suppressed new particle formation. NOx also suppressed SOA mass yield in the absence of SO2. The suppression of SOA yield by NOx was likely due to the suppressed new particle formation, i.e., absence of sufficient particle surfaces for organic vapor to condense on at high NOx, which could result in large vapor loss to chamber walls.

SO2 enhanced SOA yield from α-pinene and limonene photooxidation. SO2 oxidation produced a high number concentration of particles and compensated for the suppression of SOA yield by NOx to a large extent. The enhancement of SOA yield by SO2 is likely to be mainly caused by facilitating nucleation by H2SO4, although the contribution of acid-catalyzed heterogeneous uptake cannot be excluded.

NOx promoted nitrate formation. The majority (57–77 %) of nitrate was organic nitrate at both low NOx and high NOx, based on the estimate using the NO ∕ NO+ ratios from AMS data. The significant contribution of organic nitrate to nitrate may have important implications for deriving the hygroscopicity from chemical composition. For example, a number of studies derived the hygroscopicity parameter by linear combination of the hygroscopicity parameters of various components such as sulfate, nitrate, and organics, assuming all nitrates are inorganic nitrate (Wu et al., 2013; Cubison et al., 2008; Yeung et al., 2014; Bhattu and Tripathi, 2015; Jaatinen et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2012; Gysel et al., 2007). Because the hygroscopicity parameter of organic nitrate may be much lower than inorganic nitrate (Suda et al., 2014), such derivation may overestimate hygroscopicity.

Organic nitrate compounds are estimated to contribute 7–26 % of the total organics using an average molecular weight of 200 g mol−1 for organic nitrate compounds and a higher contribution of organic nitrate was found at high NOx. Generally, SOA formed at high NOx has a lower H ∕ C compared to that at low NOx. The higher contribution of organic nitrate to total organics and lower H ∕ C at high NOx than at low NOx is attributed to the reaction of RO2 with NO, which produced more organic nitrates relative to organic hydroperoxides formed via the reaction of RO2 with HO2. The different chemical composition of SOA between high and low-NOx conditions may affect the physicochemical properties of SOA such as volatility, hygroscopicity, and optical properties and thus change the impact of SOA on environment and climate.

In this study, the influence of vapor wall loss on SOA yield was estimated, although the SOA yields in this study were not corrected for vapor wall loss. We need to be cautious about the enhancement of the SOA yield by SO2 under high-NOx conditions and the suppression of the SOA yield by NOx under low-SO2 conditions. These effects will be less pronounced when vapor wall loss is considered because of the significant vapor loss to chamber walls rather than to particles at low particle surface concentration. Yet, the low particle surface concentration and thus low condensational sink of vapors to particle surface reflect some real cases in the atmosphere, because when the condensational sink by particle surface is low in the atmosphere, organic vapors will be lost to the next largest sink, e.g., dry deposition. Nevertheless, our important findings hold for the influence of NOx and SO2 on SOA new particle formation, mass yield, and chemical composition, showing indeed the interaction of anthropogenic and biogenic emissions in the process of SOA formation.

The different effects of NOx and SO2 on new particle formation and SOA mass yields have important implications for SOA formation affected by anthropogenic–biogenic interactions in the ambient atmosphere. When an air mass of anthropogenic origin is transported to an area enriched in biogenic VOC emissions or vice versa, anthropogenic–biogenic interactions occur. Such scenarios are common in the ambient atmosphere in many areas. For example, Kiendler-Scharr et al. (2016) shows that the organic nitrate concentrations are high in all the rural sites all over Europe, indicating the important influence of anthropogenic emissions in rural areas which are often enriched in biogenic emissions. The 14C analyses in several studies show that modern source carbon, from biogenic emission or biomass burning, accounts for large fractions of organic aerosol even in urban areas (Szidat et al., 2009; Weber et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2012), indicating the potential interactions of biogenic emissions with anthropogenic emissions in urban areas. In such cases, anthropogenic NOx alone may suppress the new particle formation and SOA mass from biogenic VOC oxidation, as we found in this study, because in principle the suppression of SOA mass due to suppressed nucleation can occur in the ambient atmosphere, although chamber experiments often cannot accurately simulate the vapor loss on surface in the boundary layer. However, due to the coexistence of NOx with SO2, H2SO4 formed by SO2 oxidation can counteract such suppression of particle mass because, regardless of NOx levels, H2SO4 can induce new particle formation especially in the presence of water, ammonia, or amine (Berndt et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2012; Sipila et al., 2010; Almeida et al., 2013; Kirkby et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012). The overall effects on SOA mass depend on specific NOx, SO2, and VOC concentrations and VOC types as well as anthropogenic aerosol concentrations and can be a net suppressing, neutral, or enhancing effect. Such scheme is depicted in Fig. 8. Other anthropogenic emissions, such as primary anthropogenic aerosol and precursors of anthropogenic secondary aerosol, can have similar roles as SO2. By affecting the concentrations of SO2, NOx, and anthropogenic aerosol, anthropogenic emissions may have important mediating impacts on biogenic SOA formation. Considering the effects of these factors in isolation may cause bias in predicting biogenic SOA concentrations. The combined impacts of SO2, NOx, and anthropogenic aerosol are also important to the estimate on how much organic aerosol concentrations will change with the ongoing and future reduction of anthropogenic emissions (Carlton et al., 2010).

All the data in the figures of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author (t.mentel@fz-juelich.de).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-1611-2018-supplement.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank the SAPHIR team, especially Rolf Häseler, Florian Rubach, and

Dieter Klemp, for supporting our measurements and providing helpful data.

Mingjin Wang would like to thank the China Scholarship Council for funding the joint

PhD program. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and

suggestions.

The article processing charges for this open-access

publication were covered by a Research

Centre of the Helmholtz Association.

Edited by: Hang Su

Reviewed by: two anonymous referees

Aiken, A. C., DeCarlo, P. F., and Jimenez, J. L.: Elemental analysis of organic species with electron ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem., 79, 8350–8358, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac071150w, 2007.

Aiken, A. C., Decarlo, P. F., Kroll, J. H., Worsnop, D. R., Huffman, J. A., Docherty, K. S., Ulbrich, I. M., Mohr, C., Kimmel, J. R., Sueper, D., Sun, Y., Zhang, Q., Trimborn, A., Northway, M., Ziemann, P. J., Canagaratna, M. R., Onasch, T. B., Alfarra, M. R., Prevot, A. S. H., Dommen, J., Duplissy, J., Metzger, A., Baltensperger, U., and Jimenez, J. L.: O ∕ C and OM/OC ratios of primary, secondary, and ambient organic aerosols with high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometry, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 4478–4485, https://doi.org/10.1021/es703009q, 2008.

Almeida, J., Schobesberger, S., Kurten, A., Ortega, I. K., Kupiainen-Maatta, O., Praplan, A. P., Adamov, A., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., David, A., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Downard, A., Dunne, E., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Henschel, H., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kajos, M., Kangasluoma, J., Keskinen, H., Kupc, A., Kurten, T., Kvashin, A. N., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Leiminger, M., Leppa, J., Loukonen, V., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., McGrath, M. J., Nieminen, T., Olenius, T., Onnela, A., Petaja, T., Riccobono, F., Riipinen, I., Rissanen, M., Rondo, L., Ruuskanen, T., Santos, F. D., Sarnela, N., Schallhart, S., Schnitzhofer, R., Seinfeld, J. H., Simon, M., Sipila, M., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tome, A., Trostl, J., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Vaattovaara, P., Viisanen, Y., Virtanen, A., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Weingartner, E., Wex, H., Williamson, C., Wimmer, D., Ye, P. L., Yli-Juuti, T., Carslaw, K. S., Kulmala, M., Curtius, J., Baltensperger, U., Worsnop, D. R., Vehkamaki, H., and Kirkby, J.: Molecular understanding of sulphuric acid-amine particle nucleation in the atmosphere, Nature, 502, 359–363, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12663, 2013.

Atkinson, R. and Arey, J.: Atmospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds, Chem. Rev., 103, 4605–4638, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0206420, 2003.

Atkinson, R., Baulch, D. L., Cox, R. A., Crowley, J. N., Hampson, R. F., Hynes, R. G., Jenkin, M. E., Rossi, M. J., and Troe, J.: Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume I – gas phase reactions of Ox, HOx, NOx and SOx species, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 4, 1461–1738, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-4-1461-2004, 2004.

Atkinson, R., Baulch, D. L., Cox, R. A., Crowley, J. N., Hampson, R. F., Hynes, R. G., Jenkin, M. E., Rossi, M. J., Troe, J., and IUPAC Subcommittee: Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume II – gas phase reactions of organic species, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 6, 3625–4055, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-3625-2006, 2006.

Berndt, T., Boge, O., Stratmann, F., Heintzenberg, J., and Kulmala, M.: Rapid formation of sulfuric acid particles at near-atmospheric conditions, Science, 307, 698–700, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1104054, 2005.

Berndt, T., Richters, S., Kaethner, R., Voigtlander, J., Stratmann, F., Sipila, M., Kulmala, M., and Herrmann, H.: Gas-Phase Ozonolysis of Cycloalkenes: Formation of Highly Oxidized RO2 Radicals and Their Reactions with NO, NO2, SO2, and Other RO2 Radicals, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 10336–10348, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b07295, 2015.

Bhattu, D. and Tripathi, S. N.: CCN closure study: Effects of aerosol chemical composition and mixing state, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 120, 766–783, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jd021978, 2015.

Bohn, B. and Zilken, H.: Model-aided radiometric determination of photolysis frequencies in a sunlit atmosphere simulation chamber, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 191–206, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-191-2005, 2005.

Bohn, B., Rohrer, F., Brauers, T., and Wahner, A.: Actinometric measurements of NO2 photolysis frequencies in the atmosphere simulation chamber SAPHIR, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 493–503, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-493-2005, 2005.

Canagaratna, M. R., Jimenez, J. L., Kroll, J. H., Chen, Q., Kessler, S. H., Massoli, P., Hildebrandt Ruiz, L., Fortner, E., Williams, L. R., Wilson, K. R., Surratt, J. D., Donahue, N. M., Jayne, J. T., and Worsnop, D. R.: Elemental ratio measurements of organic compounds using aerosol mass spectrometry: characterization, improved calibration, and implications, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 253–272, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-253-2015, 2015.

Carlton, A. G., Wiedinmyer, C., and Kroll, J. H.: A review of Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) formation from isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4987–5005, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4987-2009, 2009.

Carlton, A. G., Pinder, R. W., Bhave, P. V., and Pouliot, G. A.: To What Extent Can Biogenic SOA be Controlled?, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 3376–3380, https://doi.org/10.1021/es903506b, 2010.

Chen, M., Titcombe, M., Jiang, J. K., Jen, C., Kuang, C. A., Fischer, M. L., Eisele, F. L., Siepmann, J. I., Hanson, D. R., Zhao, J., and McMurry, P. H.: Acid-base chemical reaction model for nucleation rates in the polluted atmospheric boundary layer, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 18713–18718, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210285109, 2012.

Chhabra, P. S., Ng, N. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Corrigan, A. L., Russell, L. M., Worsnop, D. R., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Elemental composition and oxidation of chamber organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 8827–8845, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-8827-2011, 2011.

Chu, B., Zhang, X., Liu, Y., He, H., Sun, Y., Jiang, J., Li, J., and Hao, J.: Synergetic formation of secondary inorganic and organic aerosol: effect of SO2 and NH3 on particle formation and growth, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 14219–14230, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-14219-2016, 2016.

Chung, S. H. and Seinfeld, J. H.: Global distribution and climate forcing of carbonaceous aerosols, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, 4407, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jd001397, 2002.

Clegg, S. L., Brimblecombe, P., and Wexler, A. S.: Thermodynamic model of the system H+-NH-SO-NO-H2O at tropospheric temperatures, J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 2137–2154, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp973042r, 1998.

Cubison, M. J., Ervens, B., Feingold, G., Docherty, K. S., Ulbrich, I. M., Shields, L., Prather, K., Hering, S., and Jimenez, J. L.: The influence of chemical composition and mixing state of Los Angeles urban aerosol on CCN number and cloud properties, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 5649–5667, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-5649-2008, 2008.

de Gouw, J. A., Middlebrook, A. M., Warneke, C., Goldan, P. D., Kuster, W. C., Roberts, J. M., Fehsenfeld, F. C., Worsnop, D. R., Canagaratna, M. R., Pszenny, A. A. P., Keene, W. C., Marchewka, M., Bertman, S. B., and Bates, T. S.: Budget of organic carbon in a polluted atmosphere: Results from the New England Air Quality Study in 2002, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 110, D16305, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004jd005623, 2005.

Ding, X. A., Wang, X. M., and Zheng, M.: The influence of temperature and aerosol acidity on biogenic secondary organic aerosol tracers: Observations at a rural site in the central Pearl River Delta region, South China, Atmos. Environ., 45, 1303–1311, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.057, 2011.

Draper, D. C., Farmer, D. K., Desyaterik, Y., and Fry, J. L.: A qualitative comparison of secondary organic aerosol yields and composition from ozonolysis of monoterpenes at varying concentrations of NO2, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 12267–12281, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-12267-2015, 2015.

Eddingsaas, N. C., Loza, C. L., Yee, L. D., Chan, M., Schilling, K. A., Chhabra, P. S., Seinfeld, J. H., and Wennberg, P. O.: α-pinene photooxidation under controlled chemical conditions – Part 2: SOA yield and composition in low- and high-NOx environments, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 7413–7427, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-7413-2012, 2012a.

Eddingsaas, N. C., Loza, C. L., Yee, L. D., Seinfeld, J. H., and Wennberg, P. O.: α-pinene photooxidation under controlled chemical conditions – Part 1: Gas-phase composition in low- and high-NOx environments, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 6489–6504, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-6489-2012, 2012b.

Ehn, M., Thornton, J. A., Kleist, E., Sipila, M., Junninen, H., Pullinen, I., Springer, M., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Lee, B., Lopez-Hilfiker, F., Andres, S., Acir, I. H., Rissanen, M., Jokinen, T., Schobesberger, S., Kangasluoma, J., Kontkanen, J., Nieminen, T., Kurten, T., Nielsen, L. B., Jorgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., Canagaratna, M., Dal Maso, M., Berndt, T., Petaja, T., Wahner, A., Kerminen, V. M., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Wildt, J., and Mentel, T. F.: A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol, Nature, 506, 476–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13032, 2014.

Emanuelsson, E. U., Hallquist, M., Kristensen, K., Glasius, M., Bohn, B., Fuchs, H., Kammer, B., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Nehr, S., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Wahner, A., Wu, H.-C., and Mentel, Th. F.: Formation of anthropogenic secondary organic aerosol (SOA) and its influence on biogenic SOA properties, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 2837–2855, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-2837-2013, 2013.

Farmer, D. K., Matsunaga, A., Docherty, K. S., Surratt, J. D., Seinfeld, J. H., Ziemann, P. J., and Jimenez, J. L.: Response of an aerosol mass spectrometer to organonitrates and organosulfates and implications for atmospheric chemistry, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 6670–6675, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912340107, 2010.

Finlayson-Pitts, B. J., and Pitts Jr., J. N.: Chemistry of the upper and lower atmosphere: theory, experiments, and applications, Academic Press, San Diego, 969 pp., 1999.

Flores, J. M., Zhao, D. F., Segev, L., Schlag, P., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Fuchs, H., Watne, Å. K., Bluvshtein, N., Mentel, Th. F., Hallquist, M., and Rudich, Y.: Evolution of the complex refractive index in the UV spectral region in ageing secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 5793–5806, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-5793-2014, 2014.

Friedman, B., Brophy, P., Brune, W. H., and Farmer, D. K.: Anthropogenic Sulfur Perturbations on Biogenic Oxidation: SO2 Additions Impact Gas-Phase OH Oxidation Products of alpha- and beta-Pinene, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 1269–1279, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05010, 2016.

Fry, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Rollins, A. W., Wooldridge, P. J., Brown, S. S., Fuchs, H., Dubé, W., Mensah, A., dal Maso, M., Tillmann, R., Dorn, H.-P., Brauers, T., and Cohen, R. C.: Organic nitrate and secondary organic aerosol yield from NO3 oxidation of β-pinene evaluated using a gas-phase kinetics/aerosol partitioning model, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 1431–1449, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1431-2009, 2009.

Fuchs, H., Dorn, H.-P., Bachner, M., Bohn, B., Brauers, T., Gomm, S., Hofzumahaus, A., Holland, F., Nehr, S., Rohrer, F., Tillmann, R., and Wahner, A.: Comparison of OH concentration measurements by DOAS and LIF during SAPHIR chamber experiments at high OH reactivity and low NO concentration, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 5, 1611–1626, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-5-1611-2012, 2012.

Glasius, M., la Cour, A., and Lohse, C.: Fossil and nonfossil carbon in fine particulate matter: A study of five European cities, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 116, D11302, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jd015646, 2011.

Goldstein, A. H., Koven, C. D., Heald, C. L., and Fung, I. Y.: Biogenic carbon and anthropogenic pollutants combine to form a cooling haze over the southeastern United States, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 8835–8840, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904128106, 2009.

Griffin, R. J., Cocker, D. R., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Organic aerosol formation from the oxidation of biogenic hydrocarbons, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 104, 3555–3567, https://doi.org/10.1029/1998jd100049, 1999.

Guenther, A., Hewitt, C. N., Erickson, D., Fall, R., Geron, C., Graedel, T., Harley, P., Klinger, L., Lerdau, M., McKay, W. A., Pierce, T., Scholes, B., Steinbrecher, R., Tallamraju, R., Taylor, J., and Zimmerman, P.: A global-model of natural volatile organic-compound emissions, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 100, 8873–8892, https://doi.org/10.1029/94jd02950, 1995.

Guenther, A. B., Jiang, X., Heald, C. L., Sakulyanontvittaya, T., Duhl, T., Emmons, L. K., and Wang, X.: The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions, Geosci. Model Dev., 5, 1471–1492, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012, 2012.

Gysel, M., Crosier, J., Topping, D. O., Whitehead, J. D., Bower, K. N., Cubison, M. J., Williams, P. I., Flynn, M. J., McFiggans, G. B., and Coe, H.: Closure study between chemical composition and hygroscopic growth of aerosol particles during TORCH2, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 6131–6144, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-6131-2007, 2007.

Hallquist, M., Wenger, J. C., Baltensperger, U., Rudich, Y., Simpson, D., Claeys, M., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., George, C., Goldstein, A. H., Hamilton, J. F., Herrmann, H., Hoffmann, T., Iinuma, Y., Jang, M., Jenkin, M. E., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Maenhaut, W., McFiggans, G., Mentel, Th. F., Monod, A., Prévôt, A. S. H., Seinfeld, J. H., Surratt, J. D., Szmigielski, R., and Wildt, J.: The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 5155–5236, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-5155-2009, 2009.

Han, Y., Stroud, C. A., Liggio, J., and Li, S.-M.: The effect of particle acidity on secondary organic aerosol formation from α-pinene photooxidation under atmospherically relevant conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 13929–13944, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-13929-2016, 2016.

Hatakeyama, S., Izumi, K., Fukuyama, T., Akimoto, H., and Washida, N.: Reactions of oh with alpha-pinene and beta-pinene in air – estimate of global co production from the atmospheric oxidation of terpenes, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 96, 947–958, https://doi.org/10.1029/90jd02341, 1991.

Henry, K. M., Lohaus, T., and Donahue, N. M.: Organic Aerosol Yields from alpha-Pinene Oxidation: Bridging the Gap between First-Generation Yields and Aging Chemistry, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 12347–12354, https://doi.org/10.1021/es302060y, 2012.

Hoffmann, T., Odum, J. R., Bowman, F., Collins, D., Klockow, D., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Formation of organic aerosols from the oxidation of biogenic hydrocarbons, J. Atmos. Chem., 26, 189–222, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005734301837, 1997.

Hoyle, C. R., Boy, M., Donahue, N. M., Fry, J. L., Glasius, M., Guenther, A., Hallar, A. G., Huff Hartz, K., Petters, M. D., Petäjä, T., Rosenoern, T., and Sullivan, A. P.: A review of the anthropogenic influence on biogenic secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 321–343, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-321-2011, 2011.

Iinuma, Y., Boege, O., Kahnt, A., and Herrmann, H.: Laboratory chamber studies on the formation of organosulfates from reactive uptake of monoterpene oxides, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 11, 7985–7997, https://doi.org/10.1039/b904025k, 2009.

Jaatinen, A., Romakkaniemi, S., Anttila, T., Hyvarinen, A. P., Hao, L. Q., Kortelainen, A., Miettinen, P., Mikkonen, S., Smith, J. N., Virtanen, A., and Laaksonen, A.: The third Pallas Cloud Experiment: Consistency between the aerosol hygroscopic growth and CCN activity, Boreal Environ. Res., 19, 368–382, 2014.

Jang, M. S., Czoschke, N. M., Lee, S., and Kamens, R. M.: Heterogeneous atmospheric aerosol production by acid-catalyzed particle-phase reactions, Science, 298, 814–817, 10.1126/science.1075798, 2002.

Jenkin, M. E., Saunders, S. M., and Pilling, M. J.: The tropospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds: A protocol for mechanism development, Atmos. Environ., 31, 81–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1352-2310(96)00105-7, 1997.

Jimenez, J. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Donahue, N. M., Prevot, A. S. H., Zhang, Q., Kroll, J. H., DeCarlo, P. F., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Ng, N. L., Aiken, A. C., Docherty, K. S., Ulbrich, I. M., Grieshop, A. P., Robinson, A. L., Duplissy, J., Smith, J. D., Wilson, K. R., Lanz, V. A., Hueglin, C., Sun, Y. L., Tian, J., Laaksonen, A., Raatikainen, T., Rautiainen, J., Vaattovaara, P., Ehn, M., Kulmala, M., Tomlinson, J. M., Collins, D. R., Cubison, M. J., Dunlea, E. J., Huffman, J. A., Onasch, T. B., Alfarra, M. R., Williams, P. I., Bower, K., Kondo, Y., Schneider, J., Drewnick, F., Borrmann, S., Weimer, S., Demerjian, K., Salcedo, D., Cottrell, L., Griffin, R., Takami, A., Miyoshi, T., Hatakeyama, S., Shimono, A., Sun, J. Y., Zhang, Y. M., Dzepina, K., Kimmel, J. R., Sueper, D., Jayne, J. T., Herndon, S. C., Trimborn, A. M., Williams, L. R., Wood, E. C., Middlebrook, A. M., Kolb, C. E., Baltensperger, U., and Worsnop, D. R.: Evolution of Organic Aerosols in the Atmosphere, Science, 326, 1525–1529, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180353, 2009.

Kanakidou, M., Seinfeld, J. H., Pandis, S. N., Barnes, I., Dentener, F. J., Facchini, M. C., Van Dingenen, R., Ervens, B., Nenes, A., Nielsen, C. J., Swietlicki, E., Putaud, J. P., Balkanski, Y., Fuzzi, S., Horth, J., Moortgat, G. K., Winterhalter, R., Myhre, C. E. L., Tsigaridis, K., Vignati, E., Stephanou, E. G., and Wilson, J.: Organic aerosol and global climate modelling: a review, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 1053–1123, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-1053-2005, 2005.

Kiendler-Scharr, A., Mensah, A. A., Friese, E., Topping, D., Nemitz, E., Prevot, A. S. H., Äijälä, M., Allan, J., Canonaco, F., Canagaratna, M., Carbone, S., Crippa, M., Dall Osto, M., Day, D. A., De Carlo, P., Di Marco, C. F., Elbern, H., Eriksson, A., Freney, E., Hao, L., Herrmann, H., Hildebrandt, L., Hillamo, R., Jimenez, J. L., Laaksonen, A., McFiggans, G., Mohr, C., O'Dowd, C., Otjes, R., Ovadnevaite, J., Pandis, S. N., Poulain, L., Schlag, P., Sellegri, K., Swietlicki, E., Tiitta, P., Vermeulen, A., Wahner, A., Worsnop, D., and Wu, H. C.: Ubiquity of organic nitrates from nighttime chemistry in the European submicron aerosol, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 7735–7744, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069239, 2016.

Kirkby, J., Curtius, J., Almeida, J., Dunne, E., Duplissy, J., Ehrhart, S., Franchin, A., Gagne, S., Ickes, L., Kurten, A., Kupc, A., Metzger, A., Riccobono, F., Rondo, L., Schobesberger, S., Tsagkogeorgas, G., Wimmer, D., Amorim, A., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., David, A., Dommen, J., Downard, A., Ehn, M., Flagan, R. C., Haider, S., Hansel, A., Hauser, D., Jud, W., Junninen, H., Kreissl, F., Kvashin, A., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Lima, J., Lovejoy, E. R., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Mikkila, J., Minginette, P., Mogo, S., Nieminen, T., Onnela, A., Pereira, P., Petaja, T., Schnitzhofer, R., Seinfeld, J. H., Sipila, M., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tome, A., Vanhanen, J., Viisanen, Y., Vrtala, A., Wagner, P. E., Walther, H., Weingartner, E., Wex, H., Winkler, P. M., Carslaw, K. S., Worsnop, D. R., Baltensperger, U., and Kulmala, M.: Role of sulphuric acid, ammonia and galactic cosmic rays in atmospheric aerosol nucleation, Nature, 476, 429–477, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10343, 2011.

Kirkby, J., Duplissy, J., Sengupta, K., Frege, C., Gordon, H., Williamson, C., Heinritzi, M., Simon, M., Yan, C., Almeida, J., Tröstl, J., Nieminen, T., Ortega, I. K., Wagner, R., Adamov, A., Amorim, A., Bernhammer, A.-K., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Brilke, S., Chen, X., Craven, J., Dias, A., Ehrhart, S., Flagan, R. C., Franchin, A., Fuchs, C., Guida, R., Hakala, J., Hoyle, C. R., Jokinen, T., Junninen, H., Kangasluoma, J., Kim, J., Krapf, M., Kürten, A., Laaksonen, A., Lehtipalo, K., Makhmutov, V., Mathot, S., Molteni, U., Onnela, A., Peräkylä, O., Piel, F., Petäjä, T., Praplan, A. P., Pringle, K., Rap, A., Richards, N. A. D., Riipinen, I., Rissanen, M. P., Rondo, L., Sarnela, N., Schobesberger, S., Scott, C. E., Seinfeld, J. H., Sipilä, M., Steiner, G., Stozhkov, Y., Stratmann, F., Tomé, A., Virtanen, A., Vogel, A. L., Wagner, A. C., Wagner, P. E., Weingartner, E., Wimmer, D., Winkler, P. M., Ye, P., Zhang, X., Hansel, A., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., Worsnop, D. R., Baltensperger, U., Kulmala, M., Carslaw, K. S., and Curtius, J.: Ion-induced nucleation of pure biogenic particles, Nature, 533, 521–526, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17953, 2016.

Kleindienst, T. E., Edney, E. O., Lewandowski, M., Offenberg, J. H., and Jaoui, M.: Secondary organic carbon and aerosol yields from the irradiations of isoprene and alpha-pinene in the presence of NOx and SO2, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 3807–3812, https://doi.org/10.1021/es052446r, 2006.

Krechmer, J. E., Pagonis, D., Ziemann, P. J., and Jimenez, J. L.: Quantification of Gas-Wall Partitioning in Teflon Environmental Chambers Using Rapid Bursts of Low-Volatility Oxidized Species Generated in Situ, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 5757–5765, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b00606, 2016.

Kroll, J. H., Ng, N. L., Murphy, S. M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 1869–1877, https://doi.org/10.1021/es0524301, 2006.

Kroll, J. H., Chan, A. W. H., Ng, N. L., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Reactions of semivolatile organics and their effects on secondary organic aerosol formation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 3545–3550, https://doi.org/10.1021/es062059x, 2007.

Lal, V., Khalizov, A. F., Lin, Y., Galvan, M. D., Connell, B. T., and Zhang, R. Y.: Heterogeneous Reactions of Epoxides in Acidic Media, J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 6078–6090, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp2112704, 2012.

Lee, B. H., Mohr, C., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Lutz, A., Hallquist, M., Lee, L., Romer, P., Cohen, R. C., Iyer, S., Kurten, T., Hu, W., Day, D. A., Campuzano-Jost, P., Jimenez, J. L., Xu, L., Ng, N. L., Guo, H., Weber, R. J., Wild, R. J., Brown, S. S., Koss, A., de Gouw, J., Olson, K., Goldstein, A. H., Seco, R., Kim, S., McAvey, K., Shepson, P. B., Starn, T., Baumann, K., Edgerton, E. S., Liu, J., Shilling, J. E., Miller, D. O., Brune, W., Schobesberger, S., D'Ambro, E. L., and Thornton, J. A.: Highly functionalized organic nitrates in the southeast United States: Contribution to secondary organic aerosol and reactive nitrogen budgets, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 1516–1521, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1508108113, 2016.