the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Divergent drivers of aerosol acidity: evidence for shifting regulatory regimes in a coastal region

Jinghao Zhai

Yujie Zhang

Baohua Cai

Yaling Zeng

Jingyi Zhang

Jianhuai Ye

Chen Wang

Tzung-May Fu

Huizhong Shen

Aerosol acidity plays a crucial role in multiphase atmospheric chemistry, influencing aerosol composition, gas-particle partitioning, and the oxidative capacity of atmosphere. However, the mechanisms governing aerosol acidity in coastal areas under extreme weather remains challenging due to the complexity of atmospheric transport. Here, we investigate aerosol pH in Shenzhen, a coastal megacity in China, by integrating field observations with multiphase buffer theory and ISORROPIA simulations. Our observations captured both a typhoon episode and typical non-typhoon periods with two contrasting regimes: during non-typhoon periods, aerosols were consistently buffered by the pair, with relative humidity serving as the primary driver of pH variability, enabling reliable predictions using multiphase buffer theory. In contrast, during a typhoon episode, nonvolatile cations derived from sea salts emerged as the dominant drivers, violating the charge balance for buffering and leading to poor performance of buffer theory. ISORROPIA simulations under the assumption of constant aerosol water content reproduced the observed pH more reliably, highlighting a compositional rather than meteorological control. Our results provide direct field-based evidence for regime shifts in aerosol acidity regulation in coastal regions and underscore the need for chemical transport models to account for composition-meteorology interactions to improve acidity predictions under extreme weather events.

- Article

(4290 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(532 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Aerosol acidity is a key regulator in multiphase atmospheric chemistry. It governs the gas-particle partitioning of semi-volatile species (e.g., NH3, HNO3, HCl, and organic acids/bases) and dictates critical aqueous-phase processes, including SO2 oxidation, secondary formation and transformations of organic compounds, and the activation of trace metals (Tilgner et al., 2021; Pye et al., 2020; Cai et al., 2024; Surratt et al., 2007). Through these pathways, aerosol acidity exerts strong control over atmospheric oxidative capacity and pollutant lifetimes (Pye et al., 2020). On a large scale, aerosol acidity plays a pivotal role in determining particle composition, optical properties, and hygroscopicity, thereby influencing their radiative impacts and the ability to act as cloud condensation nuclei (Turnock et al., 2019; Karydis et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). Moreover, aerosol acidity can enhance particle toxicity by directly triggering respiratory inflammation, and affects the solubility of heavy metals, thereby regulating their bioavailability in terrestrial and marine ecosystems (Fang et al., 2017; Song et al., 2024; Amdur et al., 1978; Longo et al., 2016). Variations in aerosol acidity are not only fundamental to atmospheric chemistry processes but also directly influence regional air quality management (e.g., coordinated control of PM2.5 and ozone), the global nitrogen and sulfur cycles, and climate feedback mechanisms. Thus, advancing the understanding of aerosol acidity has critical implications for public health and environmental policy.

Precise quantification of aerosol acidity remains an important yet challenging issue in atmospheric chemistry. Aerosol acidity is typically determined from aerosol pH. Traditional methods based on filter extraction and subsequent H+ quantification are susceptible to substantial artifacts arising from sampling and dilution (Pathak et al., 2004; Hennigan et al., 2015). Recent techniques, such as Raman-based microdroplet pH detection (Cui et al., 2021), aerosol optical tweezers (Boyer et al., 2020), fluorescence probes (Li and Kuwata, 2023), and quantitative colorimetric imaging (Craig et al., 2018), have provided novel insights into particle-scale acidity, though their applicability to real-world aerosols remains limited, particularly for real-time monitoring of aerosol acidity. Indirect proxies including ion balance and gas-to-particle molar ratios, while widely applied, suffer from systematic biases owing to neglected organic acid dissociation and semi-volatile partitioning (Metzger et al., 2006; Hennigan et al., 2015). Thermodynamic equilibrium models have emerged as the dominant framework for estimating aerosol pH values (Saxena et al., 1986; Jacobson et al., 1996; Pilinis and Seinfeld, 1987; Wexler and Seinfeld, 1991). Among them, the Extended Aerosol Inorganic Model (E-AIM) and ISORROPIA are widely employed (Wexler and Clegg, 2002; Nenes et al., 1998), with E-AIM regarded as the benchmark owing to its explicit treatment of ion activity coefficients (Clegg et al., 1992), while ISORROPIA is favored for its computational efficiency (Nenes et al., 1999). Comparative studies generally report consistent pH estimates from these two models, albeit with context-dependent deviations (Song et al., 2018; Hennigan et al., 2015; Battaglia et al., 2019). Substantial uncertainties persist in characterizing the spatiotemporal variability of aerosol acidity and its dynamic response to chemical composition and meteorological drivers. Research remains limited in coastal megacities and under extreme weather events such as typhoons, where intense atmospheric transport may substantially challenge the applicability of existing models and theories.

Aerosol acidity exhibits strong spatiotemporal variability, mainly arising from the combined influences of particle chemical composition and meteorological conditions (Zhou et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022b; Tao and Murphy, 2019, 2021). In particular, water-soluble inorganic components exert significant control, with sulfate substantially enhancing aerosol acidity due to its low volatility, whereas nitrate, with its strong hygroscopicity, increases aerosol water content (AWC) under elevated relative humidity, thereby lowering acidity (Ding et al., 2019). Therefore, a lower nitrate-to-sulfate ratio generally leads to more acidic particles (Xie et al., 2020). Meteorological conditions exert a strong influence on aerosol acidity by altering both particle water content and gas-particle partitioning. Increased relative humidity facilitates hygroscopic growth and promotes aqueous-phase reactions, which typically dilute proton concentrations and thus mitigate acidity (Bian et al., 2014). In contrast, higher temperatures shift the equilibrium of semi-volatile species such as ammonia toward the gas phase and enhance water vapor pressure, processes that together elevate proton loading and intensify aerosol acidity (Guo et al., 2018; Battaglia et al., 2017).

Coastal and marine-influenced atmospheres represent chemically distinct environments from the continental counterparts. Nonvolatile cations derived from sea salts can modify aerosol ionic balance and buffering capacity, while high relative humidity and abundant aerosol liquid water substantially affect gas-particle partitioning (Wang et al., 2022a; Wang et al., 2022b). Predicting the bulk aerosol pH and quantifying the contribution of sea salt in coastal regions is challenging due to the mixing of land and marine emissions, multiphase reactions on sea-salt surfaces, and the complexity of aerosol mixing states (Pye et al., 2020; Bougiatioti et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2016). In addition, sea-land breezes, monsoonal flows, and typhoons induce rapid shifts in aerosol sources, water content, and thermodynamic conditions, resulting in more complex acidity regulating mechanisms (Liu et al., 2019; Farren et al., 2019). Although previous studies have suggested that sea salts can substantially influence aerosol acidity in some coastal regions, direct field evidence particularly under extreme weather conditions remains scarce.

The recently proposed multiphase buffer theory provides a new framework for understanding the evolution of aerosol acidity (Zheng et al., 2020). It demonstrates that conjugate acid-base pairs act as efficient buffers that stabilize particle pH against external perturbations such as changes in emissions or sulfate production (Zheng et al., 2022b). Building on the buffering framework, it enables robust aerosol pH retrievals in ammonia-buffered regions lacking comprehensive chemical measurements (Zheng et al., 2022a). In addition, it provides a mechanistic basis for understanding the thermodynamics of displacement reactions in which strong acids or bases are substituted by weaker ones within aerosols (Chen et al., 2022). Recent study further shows that multiphase buffering constrains aerosol pH and thereby regulates the dominant aqueous sulfate formation pathways (Gao et al., 2025). However, the relative importance of different buffering systems under complex meteorological conditions remains poorly constrained, and the potential dominance of nonvolatile cations (NVCs, e.g., Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, K+) in coastal environments and during extreme weather events has not been systematically assessed with field evidence.

In this study, we integrated field observations with multiphase buffer theory and ISORROPIA II simulations to investigate the buffering capacity and controlling factors of aerosol pH in Shenzhen, China, a subtropical coastal megacity frequently influenced by typhoons. Our field observations captured both a typhoon episode and typical non-typhoon periods, providing a natural contrast between distinct atmospheric regimes. The comparison between typhoon and non-typhoon regimes enables explicit characterization of the coupled effects of aerosol composition and meteorological variability on acidity regulation under rapidly changing conditions. Moreover, our results provide direct field-based evidence for the substantial role of NVCs in modulating aerosol acidity under extreme weather conditions. These findings underscore the need to account for meteorology-composition interactions when applying multiphase buffer theory in coastal regions and reveal important limitations of current models under episodic perturbations.

2.1 Field measurements

Field measurements were carried out at the Xichong site (22.48° N, 114.56° E) on the Dapeng Peninsula in Shenzhen, China, from August to September 2022. Detailed information and site characteristics of Xichong have been described in detail elsewhere (Zhai et al., 2025a). Briefly, Xichong is located at the southeastern end of Shenzhen, a representative coastal megacity in southern China. During the field campaign, a Monitor for AeRosols and Gases in Ambient air (MARGA, Metrohm-Applikon, the Netherlands) was utilized to measure online concentrations of major water-soluble gases (NH3, SO2, HNO3, HCl) and aerosol ions (NH, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, SO, NO, Cl−). Additional measurements at the site included PM2.5 and O3 mass concentrations, as well as key meteorological parameters (temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and wind direction). In this study, the analysis period spanned from 24 August to 11 September 2022, corresponding to the overlapping operational time of all deployed instruments, with all online data standardized to a temporal resolution of 1 h.

2.2 ISORROPIA calculation

The pH is defined in terms of the activity of hydrogen ions (H+) in aqueous solution, expressed on a molality basis as:

where a(H+) is the activity of H+, and χ(H+) and γ(H+) denote the mole fraction and mole fraction-based activity coefficients of H+ in aqueous solution, respectively. In this study, aerosol pH is calculated using ISORROPIA II (http://isorropia.epfl.ch, last access: 10 January 2026), which provides direct predictions of ionic activity, gas partial pressure, and the phase volumes of solids and liquids. Here, the model considers the Na NH K Ca Mg Cl NO SO system and is run in “forward mode” under the “metastable” phase state, which avoids salt crystallization and is more representative of ambient aerosol conditions under high humidity. It should be noted that ISORROPIA resolves the inorganic thermodynamic system and does not explicitly treat organic aerosol components in this study. Although the direct contribution of organics to aerosol pH is relatively minor (Guo et al., 2015), interactions between inorganic and organic components can alter acidity with pH increases of up to ∼ 0.7 units (Pye et al., 2018). Therefore, neglecting organic-inorganic interactions introduces uncertainties, but the inorganic-only framework is expected to capture the dominant acid-base chemistry governing aerosol acidity in this coastal environment. Aerosol pH was then calculated from the ISORROPIA output as:

where is the equilibrium hydronium ion concentration in ambient aerosol liquid water (mol L−1), is the equilibrium hydronium ion concentration per unit volume of air (µg m−3), and AWC is the aerosol water content (µg m−3). The factor 1000 accounts for the unit conversion between µg m−3 of air and mol L−1 of aerosol liquid water.

2.3 Multiphase buffer theory

A buffer system is defined as a chemical system that exhibits resilience to pH perturbations upon the addition of acids or bases. In homogeneous aqueous solutions, conjugate acid-base pairs are confined to the liquid phase, and thus the solution pH is governed exclusively by acid dissociation equilibria. In multiphase systems, however, the volatile components of conjugate pairs can reside in both the gas and liquid phases, and the pH is modulated by the coupled effects of gas-liquid partitioning and dissociation equilibria. The recently proposed multiphase buffer theory provides an analytical framework for the buffer capacity β of aerosol systems (Zheng et al., 2020). Here, β is defined as the amount of acid (dnacid) required to reduce pH by dpH units, or the amount of base (dnbase) required to increase pH by dpH units. It thus characterizes the instantaneous buffering capacity, relating infinitesimal changes in acid/base content to the corresponding change in pH. In this study, β (mol kg−1) is expressed as:

where Kw is the water dissociation constant (mol2 kg−2), represents the effective acid dissociation constant of the buffering agent Xi in gas-liquid multiphase systems (mol kg−1), and is the total equivalent molality of Xi, accounting for both gaseous and aqueous phases (mol kg−1).

The self-buffering capacity of water is an inherent property conferring resistance to pH changes. Here, it is defined as:

which becomes appreciable only under extreme acidic (pH < 2) or alkaline (pH > 12) conditions, but is negligible within the typical aerosol pH range. In contrast, conjugate acid-base pairs (e.g., , , ) dominate buffering within this range, while minor organic acids contribute little (Zheng et al., 2020). Similar to bulk aqueous systems, the effective buffer range () corresponds to the pH interval over which these conjugate pairs exert substantial buffering effects.

A previous study (Zheng et al., 2020) further introduced the dimensionless gas-liquid partitioning constant (Kg) to represent the equivalent molality of gaseous species dissolved in the aqueous phase. This formulation enables explicit treatment of gas-particle equilibria for buffering agents such as and . Corrections for non-ideality due to elevated ionic strength can also be incorporated through activity coefficients. Despite simplifying assumptions, such as assuming thermodynamic equilibrium and the neglecting organic contributions, multiphase buffer theory provides a powerful framework for quantifying aerosol buffering mechanisms.

For the buffering agent ,

For the buffering agent ,

where and are the classical dissociation constants of NH3 and HNO3 (mol kg−1), ρw is the density of liquid water (1×1012 µg m−3), R is the universal gas constant ( atm L mol−1 K−1), T is the absolute temperature (K), AWC is the aerosol water content (µg m−3), and and are the Henry's law coefficients (mol kg−1 atm−1).

For ambient aerosols, non-ideality due to elevated ionic strength should be considered, as it directly influences the calculation of the effective acid dissociation constant. When non-ideality is accounted for through the inclusion of activity coefficients, the effective acid dissociation constants in a non-ideal multiphase system are given by:

Finally, the buffer capacities associated with the and conjugate pairs are expressed as:

Multiphase buffer theory thus establishes a quantitative framework linking aerosol acidity to multiphase equilibria. Further details of the theoretical derivation are provided in the Supplement (Sect. S1 and Table S1).

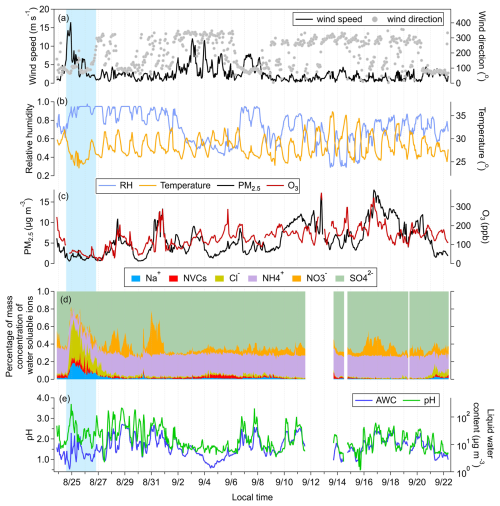

Figure 1Time series of (a) wind direction and wind speed, (b) relative humidity (RH) and temperature, (c) PM2.5 and O3 concentrations, (d) aerosol composition measured by MARGA, and (e) aerosol pH and aerosol water content (AWC) simulated by ISORROPIA at the sampling site. Other NVCs include Ca2+, Mg2+, and K+. The blue shading indicates the typhoon period.

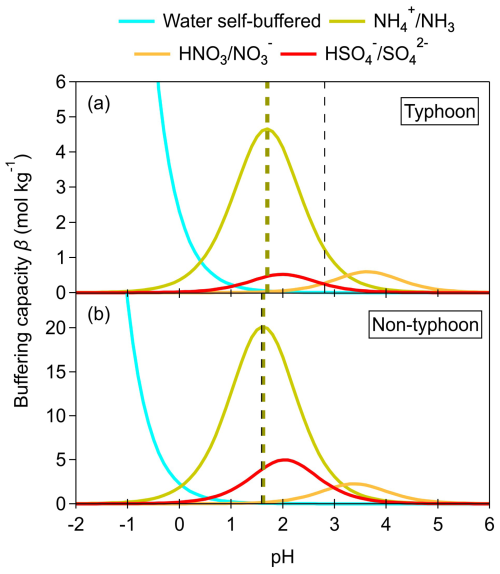

3.1 Buffer Capacity for Aerosol Multiphase Systems

In this study, MARGA measurements were conducted from 24 August to 10 September 2022 at the Xichong site. Meteorological conditions, chemical compositions obtained from MARGA, and the aerosol water content and pH values simulated by ISORROPIA throughout the sampling period are presented in Fig. 1. During the sampling period, Typhoon Ma-on (No. 2209) passed over the sampling site at 15:00 local time on 24 August 2022. Upon its arrival, wind speed at Xichong reached 16.5 m s−1, the highest value during the observation period. Concurrent decreases in PM2.5, ozone, and total water-soluble ion mass concentrations were observed, accompanied by pronounced increases in the fractional contributions of chloride, sodium, and other NVCs (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, K+) (Fig. 1a–d). The typhoon-affected period was defined based on the timing of maximum wind speed and the official declaration of typhoon passage at 19:00 on 25 August 2022. To avoid residual influence, a subsequent 24 h period was also included in the typhoon-affected period. Meteorological observations (wind speed < 3 m s−1 and a transition from easterly marine flow to inland background flow) confirmed that atmospheric conditions had stabilized before the start of the non-typhoon dataset. This interval is hereafter referred to as the typhoon episode (blue shading in Fig. 1), with all remaining periods classified as non-typhoon episodes. The ISORROPIA-simulated pH values averaged 2.81 ± 0.54 during the typhoon episode and 1.59 ± 0.45 during non-typhoon periods (Fig. 1e).

We applied the multiphase buffer theory to calculate the buffering capacities (β) of individual buffering agents (, , and ) under both typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios. The βvalues were calculated using the average chemical compositions of the typhoon and non-typhoon periods, respectively, with the averaged inputs summarized in Table S2. In both scenarios, the pair exhibited the greatest buffering capacity, followed by and (Fig. 2). The peak buffer pH (defined as the pH corresponding to the local maximum of β) for the non-typhoon scenario was ∼ 1.62 (Fig. 2a), closely matching the ISORROPIA-modeled result (1.59 ± 0.45). In contrast, the peak buffer pH under the typhoon scenario was ∼ 1.70 (Fig. 2b), showing a much larger discrepancy from the ISORROPIA-simulated result (2.81 ± 0.54).

The stronger role of under non-typhoon conditions reflects the abundance of ammonia in this coastal environment and its efficient partitioning, which results in a stable buffering regime at acidic pH. However, for the typhoon scenario, the multiphase buffer theory appears to be less applicable. It should also be noted that multiphase buffer theory assumes instantaneous thermodynamic equilibrium and primarily considers inorganic conjugate acid-base pairs, while the potential contributions of organic species and kinetic effects are neglected. Such simplifications may further contribute to discrepancies under dynamic conditions.

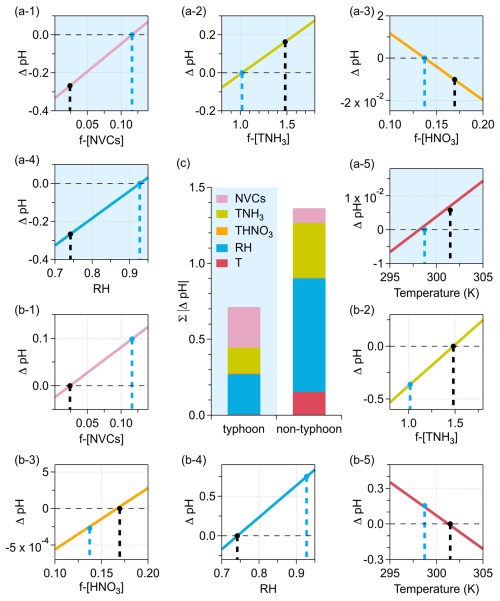

3.2 Contribution of individual drivers

We further quantified the changes in aerosol pH (ΔpH) between typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios attributable to individual drivers (Fig. 3), including anion-normalized nonvolatile cations (NVCs) and total ammonia (TNH3), the fraction of total nitric acid (THNO3) in anions, relative humidity (RH), and temperature (T). It should be noted that the perturbation constraints imposed on each driver differ both in magnitude and physical interpretation (i.e., x-axis criteria in Fig. 3, see Sect. S2). As a result, the ΔpH contributions of different drivers within the same scenario are not strictly comparable. Specifically, ΔpH was calculated as the difference between the simulated pH values obtained by constraining the ISORROPIA model with typhoon and non-typhoon datasets, while perturbing only the driver of interest within the observed variability range and holding all other inputs constant. In contrast, the ΔpH contributions of a given driver between the typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios are derived under the same constraint framework and can therefore be meaningfully compared.

To illustrate the calculation, we take relative humidity (RH) as an example. Each scenario has its own thermodynamic input setting in ISORROPIA: St for the typhoon period and Snt for the non-typhoon period. RH also has two corresponding values: RHt (typhoon) and RHnt (non-typhoon). To isolate the contribution of RH, we substituted both values into the same constraint setting while keeping all other inputs constant. Under the typhoon input setting St, we calculated:

This represents how much the pH in the typhoon environment would change if RH were replaced by its non-typhoon value.

Similarly, under the non-typhoon constraint setting Snt, we calculated:

In Fig. 3, the blue and black dashed lines represent the corresponding values for typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios, respectively. For each driver, the ΔpH values correspond to the pH differences between the two scenarios under the same constraints. The constraint ranges were selected to reflect the observed variability during the campaign, thereby ensuring that the perturbations remained within realistic atmospheric conditions. Figure 3c presents the ΔpH contributions using absolute bar charts, which highlight their absolute magnitudes rather than relative shares. While the buffering capacity β (Fig. 2) describes the intrinsic pH sensitivity within a single scenario, the ΔpH in Fig. 3 quantifies the driver-induced pH difference between typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios under the same perturbation constraints. Therefore, β and ΔpH represent different dimensions of aerosol acidity.

Figure 3Aerosol pH differences (ΔpH) between typhoon (a-1–a-5) and non-typhoon (b-1–b-5) scenarios, attributed to anion-normalized non-volatile cations (NVCs) and total ammonia (TNH3), the fraction of total nitric acid (THNO3) in anions, relative humidity (RH), and temperature (T). The light blue background indicates simulations using typhoon conditions as inputs (a-1–a-5), whereas the white background denotes simulations with non-typhoon conditions (b-1–b-5). Panel (c) summarizes the total absolute ΔpH () of different drivers in both scenarios. The blue and black dashed lines represent the corresponding values for typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios, respectively.

The results indicate that RH, TNH3, and temperature contributed substantially more to ΔpH in the non-typhoon scenario than in the typhoon scenario, with 0.75 vs. 0.26 units for RH, 0.36 vs. 0.16 units for TNH3, and 0.15 vs. 0.01 units for temperature, respectively. Notably, NVCs were the only driver exhibiting a larger contribution to ΔpH in the typhoon scenario than in the non-typhoon scenario (0.27 vs. 0.09 units). In other words, the contribution of chemical components, particularly NVCs, to ΔpH was more pronounced in the typhoon scenario, which partly explains the discrepancy between the pH predicted by the multiphase buffer theory and that calculated by ISORROPIA. This shift highlights a transition from meteorologically driven controls (RH and temperature) under non-typhoon conditions to compositionally driven controls dominated by sea-salt-derived cations during the typhoon.

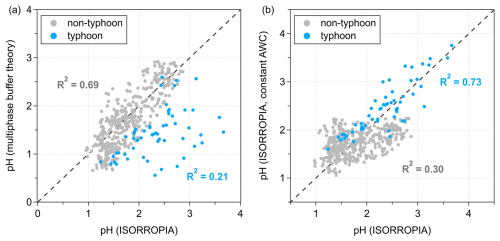

Figure 4Correlations between aerosol pH simulated using ISORROPIA and pH predicted by (a) the multiphase buffer theory, and (b) ISORROPIA under a constant aerosol water content (AWC) assumption with varying chemical compositions. Blue and gray dots represent typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios, respectively. The black dashed line indicates the 1:1 reference.

Previous studies in inland regions (Zheng et al., 2020), such as the North China Plain and the southeastern United States, have emphasized ammonia availability and aerosol water as the primary determinants of aerosol acidity, whereas our results underscore the distinct role of NVCs in coastal megacities under the influence of extreme weather. The multiphase buffer theory implicitly assumes that aerosol acidity is regulated primarily through buffering by volatile or semi-volatile conjugate acid-base pairs, rather than by direct neutralization from non-volatile species. For to serve as the dominant buffering pair, two conditions must be satisfied (Zheng et al., 2020): (1) the equivalent charge of total cations exceeds that of total anions, and (2) the equivalent charge of NVCs is lower than that of nonvolatile anions. In the typhoon scenario, however, the equivalent charge of NVCs exceeded that of nonvolatile anions, thereby effectively violating the conditions required for to serve as the dominant buffering pair. This explains why the multiphase buffer theory fails to reliably predict aerosol pH under typhoon conditions. The enhanced influence of NVCs can be attributed to the substantial influx of sea-salt particles transported by strong winds and the altered trajectories of air masses during the typhoon. These inputs directly neutralize acidic species and disrupt the conventional buffering system, a process far less pronounced in inland settings.

We compared the ISORROPIA-simulated pH with both the pH predicted by multiphase buffer theory and the ISORROPIA-simulated pH under a constant AWC assumption for typhoon and non-typhoon scenarios, respectively (Fig. 4). Here, ISORROPIA-simulated pH refers to the standard model output using measured temperature, RH, and aerosol chemical composition. Multiphase buffer theory pH refers to the pH diagnosed from observations using the multiphase buffer theory based on measured ion concentrations. Constant-AWC pH corresponds to the ISORROPIA-simulated pH under a fixed aerosol water content of 10 µg m−3 (mean AWC of all calculated conditions). The constant-AWC experiment was designed to isolate the role of chemical composition from that of aerosol water content, thereby allowing us to directly assess whether pH variability can be reproduced without explicitly accounting for dynamic changes in AWC. The results show that under the non-typhoon scenario, ISORROPIA-simulated pH exhibits a stronger correlation with the multiphase buffer theory (R2 = 0.69) than with the constant-AWC simulation (R2 = 0.30). In contrast, under the typhoon scenario, the ISORROPIA-simulated pH correlates well with constant-AWC (R2 = 0.73), but poorly with the multiphase buffer theory (R2 = 0.21). These findings indicate that in regimes or scenarios buffered by the pair, such as non-typhoon conditions in Shenzhen, variations in AWC alone can provide a reliable prediction of aerosol pH, even without explicitly accounting for the temporal and spatial variability in particle chemical composition. The buffering effect of ammonia suppresses the influence of compositional differences, making aerosol water content the primary determinant of aerosol pH. However, in environments that are not buffered by , the influence of AWC on pH becomes weaker, and reliable predictions require explicit consideration of chemical composition within a constant-AWC framework.

These results suggest that chemical composition exerts a stronger control on pH under typhoon conditions, whereas during non-typhoon periods, aerosol water content driven by RH and temperature becomes the dominant influence. While multiphase buffer theory remains robust in ammonia-buffered regimes, its applicability is substantially reduced in environments in which aerosol acidity is dominated by NVC-driven charge neutralization. Refining the framework to explicitly incorporate composition-meteorology interactions is therefore essential for accurately predicting aerosol acidity in coastal regions affected by extreme weather events.

3.3 Atmospheric implications

In densely populated continental regions, where anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric ammonia concentrations are high, aerosol pH is likely controlled by the buffering pair and can therefore be reasonably approximated on the basis of aerosol mass concentration and liquid water content. This provides an opportunity to reconstruct long-term trends and large-scale spatial distributions of aerosol pH, and implies that emission reductions targeting ammonia and sulfate can exert direct and predictable influences on aerosol acidity.

In coastal regions, however, whether ammonia serves as the dominant buffering pair is strongly influenced by seasonality and meteorological conditions. Our field observations directly captured two contrasting situations: a non-typhoon period, in which ammonia acted as the dominant buffering pair, and a typhoon period, during which NVCs played a more important role. In the former case, aerosol pH can be reliably predicted using only aerosol mass concentration and AWC, whereas in the latter case, more detailed chemical composition information is required for accurate prediction. Acidity regulation in coastal areas is inherently more variable than in continental settings, with rapid transitions between meteorological and compositional control. Such variability complicates the prediction of secondary aerosol formation and the assessment of pH-dependent processes (e.g., metal solubility and heterogeneous chemistry). Our results therefore underscore the need for improved representation of composition-meteorology interactions in chemical transport models and highlight the need for targeted observations during extreme weather events to constrain acidity regulation in coastal atmospheres.

Data used to produce the plots within this work are available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17207845, Zhai et al., 2025b).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-623-2026-supplement.

JZ and XY designed the study. JZ and YZ analyzed the data. JZ wrote the manuscript. All co-authors contributed to discussions and suggestions in finalizing the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to thank the Shenzhen National Climate Observatory for providing the observation platform for this study.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42305108, 42530609), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Research Foundation (grant no. 2025A1515011148), the Guangdong Provincial Observation and Research Station for Coastal Atmosphere and Climate of the Greater Bay Area (grant no. 2021B1212050024), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (grant nos. KQTD20210811090048025, KCXFZ20230731093601003), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (grant no. 2023YFE0112901).

This paper was edited by Theodora Nah and reviewed by four anonymous referees.

Amdur, M. O., Bayles, J., Ugro, V., and Underhill, D. W.: Comparative irritant potency of sulfate salts, Environ. Res., 16, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-9351(78)90135-4, 1978.

Battaglia, M. A., Douglas, S., and Hennigan, C. J.: Effect of the Urban Heat Island on Aerosol pH, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 13095–13103, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b02786, 2017.

Battaglia Jr., M. A., Weber, R. J., Nenes, A., and Hennigan, C. J.: Effects of water-soluble organic carbon on aerosol pH, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 14607–14620, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-14607-2019, 2019.

Bian, Y. X., Zhao, C. S., Ma, N., Chen, J., and Xu, W. Y.: A study of aerosol liquid water content based on hygroscopicity measurements at high relative humidity in the North China Plain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 6417–6426, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-6417-2014, 2014.

Bougiatioti, A., Nikolaou, P., Stavroulas, I., Kouvarakis, G., Weber, R., Nenes, A., Kanakidou, M., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Particle water and pH in the eastern Mediterranean: source variability and implications for nutrient availability, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 4579–4591, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-4579-2016, 2016.

Boyer, H. C., Gorkowski, K., and Sullivan, R. C.: In Situ pH Measurements of Individual Levitated Microdroplets Using Aerosol Optical Tweezers, Anal. Chem., 92, 1089–1096, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04152, 2020.

Cai, B. H., Wang, Y. X., Yang, X., Li, Y. C., Zhai, J. H., Zeng, Y. L., Ye, J. H., Zhu, L., Fu, T. M., and Zhang, Q.: Rapid aqueous-phase dark reaction of phenols with nitrosonium ions: Novel mechanism for atmospheric nitrosation and nitration at low pH, Pnas Nexus, 3, https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae385, 2024.

Chen, Z., Liu, P., Su, H., and Zhang, Y. H.: Displacement of Strong Acids or Bases by Weak Acids or Bases in Aerosols: Thermodynamics and Kinetics, Environ. Sci. Technol., https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c03719, 2022.

Clegg, S. L., Pitzer, K. S., and Brimblecombe, P.: thermodynamics of multicomponent, miscible, ionic-solutions .2. mixtures including unsymmetrical electrolytes, J. Phys. Chem., 96, 9470–9479, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100202a074, 1992.

Craig, R. L., Peterson, P. K., Nandy, L., Lei, Z., Hossain, M. A., Camarena, S., Dodson, R. A., Cook, R. D., Dutcher, C. S., and Ault, A. P.: Direct Determination of Aerosol pH: Size-Resolved Measurements of Submicrometer and Supermicrometer Aqueous Particles, Anal. Chem., 90, 11232–11239, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00586, 2018.

Cui, X. Y., Tang, M. J., Wang, M. J., and Zhu, T.: Water as a probe for pH measurement in individual particles using micro-Raman spectroscopy, Anal. Chim. Acta, 1186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2021.339089, 2021.

Ding, J., Zhao, P., Su, J., Dong, Q., Du, X., and Zhang, Y.: Aerosol pH and its driving factors in Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 7939–7954, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-7939-2019, 2019.

Fang, T., Guo, H. Y., Zeng, L. H., Verma, V., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Highly Acidic Ambient Particles, Soluble Metals, and Oxidative Potential: A Link between Sulfate and Aerosol Toxicity, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 2611–2620, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06151, 2017.

Farren, N. J., Dunmore, R. E., Mead, M. I., Mohd Nadzir, M. S., Samah, A. A., Phang, S.-M., Bandy, B. J., Sturges, W. T., and Hamilton, J. F.: Chemical characterisation of water-soluble ions in atmospheric particulate matter on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 1537–1553, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-1537-2019, 2019.

Gao, J., Wei, Y. T., Wang, H. Q., Song, S. J., Xu, H., Feng, Y. C., Shi, G. L., and Russell, A. G.: Multiphase Buffering: A Mechanistic Regulator of Aerosol Sulfate Formation and Its Dominant Pathways, Environ. Sci. Technol., 59, 8073–8084, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c13744, 2025.

Guo, H., Xu, L., Bougiatioti, A., Cerully, K. M., Capps, S. L., Hite Jr., J. R., Carlton, A. G., Lee, S.-H., Bergin, M. H., Ng, N. L., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine-particle water and pH in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5211–5228, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5211-2015, 2015.

Guo, H., Otjes, R., Schlag, P., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Effectiveness of ammonia reduction on control of fine particle nitrate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 12241–12256, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-12241-2018, 2018.

Hennigan, C. J., Izumi, J., Sullivan, A. P., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: A critical evaluation of proxy methods used to estimate the acidity of atmospheric particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2775–2790, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2775-2015, 2015.

Jacobson, M. Z., Tabazadeh, A., and Turco, R. P.: Simulating equilibrium within aerosols and nonequilibrium between gases and aerosols, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 101, 9079–9091, https://doi.org/10.1029/96jd00348, 1996.

Karydis, V. A., Tsimpidi, A. P., Pozzer, A., and Lelieveld, J.: How alkaline compounds control atmospheric aerosol particle acidity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 14983–15001, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-14983-2021, 2021.

Li, W. H. and Kuwata, M.: Detecting pH of Sub-Micrometer Aerosol Particles Using Fluorescent Probes, Environ. Sci. Technol., 57, 8701–8707, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c01517, 2023.

Liu, Y., Wu, Z., Huang, X., Shen, H., Bai, Y., Qiao, K., Meng, X., Hu, W., Tang, M., and He, L.: Aerosol Phase State and Its Link to Chemical Composition and Liquid Water Content in a Subtropical Coastal Megacity, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 5027–5033, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01196, 2019.

Longo, A. F., Feng, Y., Lai, B., Landing, W. M., Shelley, R. U., Nenes, A., Mihalopoulos, N., Violaki, K., and Ingall, E. D.: Influence of Atmospheric Processes on the Solubility and Composition of Iron in Saharan Dust, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 6912–6920, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02605, 2016.

Metzger, S., Mihalopoulos, N., and Lelieveld, J.: Importance of mineral cations and organics in gas-aerosol partitioning of reactive nitrogen compounds: case study based on MINOS results, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 6, 2549–2567, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-2549-2006, 2006.

Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., and Pilinis, C.: ISORROPIA: A new thermodynamic equilibrium model for multiphase multicomponent inorganic aerosols, Aquatic Geochemistry, 4, 123–152, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009604003981, 1998.

Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., and Pilinis, C.: Continued development and testing of a new thermodynamic aerosol module for urban and regional air quality models, Atmos. Environ., 33, 1553–1560, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1352-2310(98)00352-5, 1999.

Pathak, R. K., Yao, X. H., and Chan, C. K.: Sampling artifacts of acidity and ionic species in PM2.5, Environ. Sci. Technol., 38, 254–259, https://doi.org/10.1021/es0342244, 2004.

Pilinis, C. and Seinfeld, J. H.: Continued development of a general equilibrium-model for inorganic multicomponent atmospheric aerosols, Atmos. Environ., 21, 2453–2466, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(87)90380-5, 1987.

Pye, H. O. T., Zuend, A., Fry, J. L., Isaacman-VanWertz, G., Capps, S. L., Appel, K. W., Foroutan, H., Xu, L., Ng, N. L., and Goldstein, A. H.: Coupling of organic and inorganic aerosol systems and the effect on gas–particle partitioning in the southeastern US, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 357–370, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-357-2018, 2018.

Pye, H. O. T., Nenes, A., Alexander, B., Ault, A. P., Barth, M. C., Clegg, S. L., Collett Jr., J. L., Fahey, K. M., Hennigan, C. J., Herrmann, H., Kanakidou, M., Kelly, J. T., Ku, I.-T., McNeill, V. F., Riemer, N., Schaefer, T., Shi, G., Tilgner, A., Walker, J. T., Wang, T., Weber, R., Xing, J., Zaveri, R. A., and Zuend, A.: The acidity of atmospheric particles and clouds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 4809–4888, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-4809-2020, 2020.

Saxena, P., Hudischewskyj, A. B., Seigneur, C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: A Comparative-study of equilibrium approaches to the chemical characterization of secondary aerosols, Atmos. Environ., 20, 1471–1483, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(86)90019-3, 1986.

Song, S., Gao, M., Xu, W., Shao, J., Shi, G., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., and McElroy, M. B.: Fine-particle pH for Beijing winter haze as inferred from different thermodynamic equilibrium models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7423–7438, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7423-2018, 2018.

Song, X. W., Wu, D., Chen, X., Ma, Z. Z., Li, Q., and Chen, J. M.: Toxic Potencies of Particulate Matter from Typical Industrial Plants Mediated with Acidity via Metal Dissolution, Environ. Sci. Technol., 58, 6736–6743, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c00929, 2024.

Surratt, J. D., Lewandowski, M., Offenberg, J. H., Jaoui, M., Kleindienst, T. E., Edney, E. O., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Effect of acidity on secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 5363–5369, https://doi.org/10.1021/es0704176, 2007.

Tao, Y. and Murphy, J. G.: The sensitivity of PM2.5 acidity to meteorological parameters and chemical composition changes: 10-year records from six Canadian monitoring sites, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 9309–9320, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-9309-2019, 2019.

Tao, Y. and Murphy, J. G.: Simple Framework to Quantify the Contributions from Different Factors Influencing Aerosol pH Based on NHx Phase-Partitioning Equilibrium, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 10310–10319, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c03103, 2021.

Tilgner, A., Schaefer, T., Alexander, B., Barth, M., Collett Jr., J. L., Fahey, K. M., Nenes, A., Pye, H. O. T., Herrmann, H., and McNeill, V. F.: Acidity and the multiphase chemistry of atmospheric aqueous particles and clouds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 13483–13536, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-13483-2021, 2021.

Turnock, S. T., Mann, G. W., Woodhouse, M. T., Dalvi, M., O'Connor, F. M., Carslaw, K. S., and Spracklen, D. V.: The Impact of Changes in Cloud Water pH on Aerosol Radiative Forcing, Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, 4039–4048, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019gl082067, 2019.

Wang, G. C., Chen, J., Xu, J., Yun, L., Zhang, M. D., Li, H., Qin, X. F., Deng, C. R., Zheng, H. T., Gui, H. Q., Liu, J. G., and Huang, K.: Atmospheric Processing at the Sea-Land Interface Over the South China Sea: Secondary Aerosol Formation, Aerosol Acidity, and Role of Sea Salts, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 127, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021jd036255, 2022a.

Wang, G. C., Tao, Y., Chen, J., Liu, C. F., Qin, X. F., Li, H., Yun, L., Zhang, M. D., Zheng, H. T., Gui, H. Q., Liu, J. G., Huo, J. T., Fu, Q. Y., Deng, C. R., and Huang, K.: Quantitative Decomposition of Influencing Factors to Aerosol pH Variation over the Coasts of the South China Sea, East China Sea, and Bohai Sea, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 9, 815–821, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00527, 2022b.

Weber, R., Guo, H., Russell, A., and Nenes, A.: High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years, Nat. Geosci., 9, 282, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2665, 2016.

Wexler, A. S. and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric aerosol models for systems including the ions H+, NH4+, Na+, SO42−, NO3−, Cl−, Br−, and H2O, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 107, 4207, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jd000451, 2002.

Wexler, A. S. and Seinfeld, J. H.: Second-generation inorganic aerosol model, Atmos. Environ., 25, 2731–2748, https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-1686(91)90203-J, 1991.

Xie, Y., Wang, G., Wang, X., Chen, J., Chen, Y., Tang, G., Wang, L., Ge, S., Xue, G., Wang, Y., and Gao, J.: Nitrate-dominated PM2.5 and elevation of particle pH observed in urban Beijing during the winter of 2017, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 5019–5033, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-5019-2020, 2020.

Xu, Y., Miyazaki, Y., Tachibana, E., Sato, K., Ramasamy, S., Mochizuki, T., Sadanaga, Y., Nakashima, Y., Sakamoto, Y., Matsuda, K., and Kajii, Y.: Aerosol Liquid Water Promotes the Formation of Water-Soluble Organic Nitrogen in Submicrometer Aerosols in a Suburban Forest, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 1406–1414, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b05849, 2020.

Zhai, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, P., Zhang, Y., Zhang, A., Zeng, Y., Cai, B., Zhang, J., Xing, C., Yang, H., Wang, X., Ye, J., Wang, C., Fu, T.-M., Zhu, L., Shen, H., Tao, S., and Yang, X.: Source-dependent optical properties and molecular characteristics of atmospheric brown carbon, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 7959–7972, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-7959-2025, 2025a.

Zhai, J., Zhang, Y., Cai, B., Zeng, Y., Zhang, J., Ye, J., Wang, C., Fu, T.-M., Zhu, L., Shen, H., and Yang, X.: Divergent Drivers of Aerosol Acidity: Evidence for Shifting Regulatory Regimes in a Coastal Region, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17207845, 2025b.

Zhang, A. T., Zeng, Y. L., Yang, X., Zhai, J. H., Wang, Y. X., Xing, C. B., Cai, B. H., Shi, S., Zhang, Y. J., Shen, Z. X., Fu, T. M., Zhu, L., Shen, H. Z., Ye, J. H., and Wang, C.: Organic Matrix Effect on the Molecular Light Absorption of Brown Carbon, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023gl106541, 2023.

Zhang, B., Shen, H., Liu, P., Guo, H., Hu, Y., Chen, Y., Xie, S., Xi, Z., Skipper, T. N., and Russell, A. G.: Significant contrasts in aerosol acidity between China and the United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 8341–8356, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-8341-2021, 2021.

Zheng, G., Su, H., Wang, S., Pozzer, A., and Cheng, Y.: Impact of non-ideality on reconstructing spatial and temporal variations in aerosol acidity with multiphase buffer theory, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 47–63, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-47-2022, 2022a.

Zheng, G. J., Su, H., and Cheng, Y. F.: Revisiting the Key Driving Processes of the Decadal Trend of Aerosol Acidity in the U.S, ACS Environmental Au, 2, 346–353, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenvironau.1c00055, 2022b.

Zheng, G. J., Su, H., Wang, S. W., Andreae, M. O., Pöschl, U., and Cheng, Y. F.: Multiphase buffer theory explains contrasts in atmospheric aerosol acidity, Science, 369, 1374, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba3719, 2020.

Zhou, M., Zheng, G., Wang, H., Qiao, L., Zhu, S., Huang, D., An, J., Lou, S., Tao, S., Wang, Q., Yan, R., Ma, Y., Chen, C., Cheng, Y., Su, H., and Huang, C.: Long-term trends and drivers of aerosol pH in eastern China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 13833–13844, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-13833-2022, 2022.