the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Mechanistic insights into I2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis and its role in iodine aerosol growth in pristine and polluted atmospheres

Xiucong Deng

Fengyang Bai

Jie Yang

Jing Li

Jiarong Liu

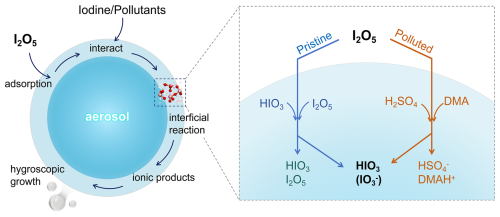

Higher-order iodine oxides are intricately linked to marine aerosol formation; however, the underlying physicochemical mechanisms remain poorly constrained, particularly for I2O5, which is stable yet conspicuously absent in the atmosphere. While reactivity with water has been implicated, the direct hydrolysis of I2O5 (I2O5+ H2O → 2HIO3) fails to account for this discrepancy due to its high activation barrier (21.8 kcal mol−1). Herein, we have probed heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5 mediated by prevalent chemicals over oceans through Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics and well-tempered metadynamics simulations. Our results demonstrate that self-catalyzed pathways involving I2O5 and its hydrolysis product HIO3 substantially reduce the reaction barrier, thereby accelerating the conversion of I2O5 to HIO3 in pristine marine environments. In polluted regions, interfacial hydrolysis of I2O5 mediated by acidic or basic pollutants (e.g., H2SO4 or amines) proceeds with even greater efficiency, characterized by remarkably low barriers (≤ 1.3 kcal mol−1). Collectively, these proposed heterogeneous reactions of I2O5 are relatively effective, acting as a hitherto unrecognized sink for I2O5 and a source of HIO3 – processes that facilitate marine aerosol growth and rationalize the high iodate abundances detected in aerosols. These findings provide mechanistic insight into the elusive I2O5-to-HIO3 conversion, offering an unheeded step toward improving the representation of iodine chemistry and marine aerosol formation in atmospheric models, with implications for climate prediction and environmental impact assessment.

- Article

(3571 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2946 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Given the vast coverage (71 %) of oceans on Earth's surface, marine aerosols exert substantial impact on the global atmosphere, altering cloud microphysical properties, radiative balance, and climate change (Kaloshin, 2021; Mahowald et al., 2018). Hence, understanding how aerosols form is fundamental for the climate system, especially ruinous extreme weather, as it introduces the greatest uncertainty in climate forcing (Gettelman and Kahn, 2025). Earlier studies have confirmed a solid association between marine aerosols and sulfur chemicals derived from the oxidation of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) (Barnes et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2024; Ning and Zhang, 2022; Shen et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022a, 2024a). While the recent evidence has shown that iodine-bearing precursors of oceanic origin such as iodine oxides (I2O2−5) and iodine oxyacids (HIO2−3) significantly contribute to marine aerosol formation, owing to their high efficiency and rising levels (Allan et al., 2015; Carpenter et al., 2021; Droste et al., 2021; Gómez Martín et al., 2021, 2022b; Huang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; McFiggans et al., 2010; O'Dowd et al., 2002; O'Dowd and De Leeuw, 2007; Roscoe et al., 2015; Saiz-Lopez et al., 2012, 2014). Despite the experimental and theoretical studies uncovering the role of HIO2−3 in aerosol formation (He et al., 2021, 2023; Liu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022b, 2024b; Zu et al., 2024), the atmospheric fate and impacts of I2O2−5 are yet to be fully established (Finkenzeller et al., 2023; Gómez Martín et al., 2013, 2020; Leroy and Bosland, 2023; Lewis et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2022), limiting the accuracy of atmospheric models in simulating iodine-driven climate effects.

As one of the highest iodine oxides, iodine pentoxide (I2O5) serves as the anhydride of iodic acid (HIO3), playing a vital role in bridging iodine oxides and iodic acid in iodine chemical cycle, however, its true fate is still elusive, with the conflicting findings reported. Specifically, I2O5 is highly thermally stable (Kaltsoyannis and Plane, 2008), yet it is not evidently present in the gas phase, implying its unknown sinks. Sipilä et al. (2016) hypothesized that I2O5 may participate in the formation of marine aerosol particles through the dehydration reaction

based on the identified oxygen-to-iodine ratio of 2.4 in field-collected particles. Nevertheless, no direct detection of I2O5, such as mass spectral signals, was provided. And the theoretical study has shown that Reaction (R1) hardly occurs due to its high energy barrier (27.8 kcal mol−1) and endothermic nature (Khanniche et al., 2016), suggesting that this sink pathway seems not well supported. A most recent experimental evidence indicates that I2O5 can indeed participate in aerosol particle formation, but under the unrealistically low-humidity conditions (Rörup et al., 2024). Upon the addition of water, I2O5 is markedly depleted, suggesting its reaction with water, accompanied by the formation of HIO3 (Gómez Martín et al., 2022a). This finding seems to support well the absence of I2O5 in high-humidity marine atmospheres. While the theoretical study of Xia et al. (2020) found that the direct reaction between I2O5 and H2O

in gas phase also needs to cross a high energy barrier of 21.8 kcal mol−1, suggesting that this process is unlikely to occur effectively, even with another H2O or I2O5 acting as a catalyst (Kumar et al., 2018). As a result, this gas-phase mechanism alone appears insufficient to explain the observed absence of I2O5 in experimental or clean marine environments, with the I2O5 sink remaining unrevealed. Furthermore, Kumar et al. (2018) proposed the heterogeneous reactions of I2O5 at the air-water interface, which is ubiquitous over oceans like aerosol surface (Zhong et al., 2018). Unfortunately, this interfacial mechanism still fails to account for the observed well-established link between I2O5 depletion and HIO3 formation, as it points to the formation of other novel product H2I2O6. Despite its dynamic stability within the simulation scale (34 ps) (Kumar et al., 2018), H2I2O6 has not been detected in the prior iodine-related experimental and field studies (Gómez Martín et al., 2020, 2022a; He et al., 2021, 2023; Rörup et al., 2024; Sipilä et al., 2016), highlighting the poor understanding of the reaction mechanism of I2O5 under pristine conditions.

The mystery of I2O5 chemistry likely deepens in polluted coastal regions, e.g., Zhejiang, China (Yu et al., 2019), where the evident burst of iodine aerosols has been also observed. Similarly, I2O5 is also evidently absent but HIO3 (detected as IO) is abundant in the field-collected aerosols, indicating I2O5 may undergo an I2O5-to-HIO3 conversion. Yet the underlying mechanisms in polluted regions remain unclear, which is likely more complex than that in pristine regions due to the pollutant-mediated impacts from typical amine or sulfuric acid that can facilitate the heterogeneous reactions of other iodine oxides (Ning et al., 2023, 2024). Taken together, these unresolved discrepancies and mechanistic uncertainties render the fate of I2O5 elusive in both pristine and polluted marine environments, which limits our understanding of its true role in atmospheric iodine chemistry and aerosol formation.

In this study, we have performed the Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations to elucidate the potential hydrolysis mechanism of I2O5 at the air-water interface, as represented by aqueous aerosol surfaces, mediated by different kinds of prevalent chemicals. We first investigate the heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5 mediated by I2O5 and HIO3, which potentially occur in pristine marine regions; while the reactions of I2O5 mediated by pollutants such as acid (sulfuric acid, SA) and alkaline (methylamine (MA), dimethylamine (DMA), trimethylamine (TMA)) were also probed to comprehend the loss path of I2O5 in polluted marine environments. Alongside mechanistic insights, we further quantified the reaction barriers by metadynamics simulations (MetaD) and block error analysis. By comparing the resulting energy barriers, the dominant mechanisms of I2O5 hydrolysis under different environments were identified. Furthermore, we performed wavefunction analysis to examine the reactive sites of I2O5 hydrolysis products at the air-water interface, which may facilitate the condensation of gaseous precursors to promote aerosol growth. This work provides mechanistic insights into heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5 that potentially occur under marine conditions, enhancing our understanding of iodine chemistry and marine aerosol formation.

2.1 Quantum Chemistry Calculations

Structural optimizations for gas-phase molecular geometries were performed using the Gaussian 16 software package (Frisch et al., 2016) with tight convergence criteria. The I2O5 molecule with lowest Gibbs free energy has been selected from isomers (Kaltsoyannis and Plane, 2008; Khanniche et al., 2016; Kim and Yoo, 2016), and details of the structures and coordinates are provided in the Supplement (Fig. S1 and Table S3). During the geometry optimization, the M06-2X functional was selected for gas-phase molecules due to its excellent performance in calculating main group elements (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008), and the adopted basis set was aug-cc-pVTZ (Kendall et al., 1992) (for C, H, O, N, and S atoms) + aug-cc-pVTZ-PP with ECP28MDF (for I atom) (Peterson et al., 2003). The frequency analysis was performed at the same level of theory to ensure that the optimized structures have no imaginary frequencies. The geometries and coordinates of gas-phase molecules (i.e. I2O5, HIO3, H2SO4, MA, DMA, and TMA) are provided in Fig. S2 and Table S2 in the Supplement, respectively.

2.2 Classical MD Simulations

Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried out by the GROMACS 2022 package (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005) to probe the interfacial propensity of I2O5 at the air-water interface. Regarding the initial configurations for MD simulations, we used the PACKMOL code (Martínez et al., 2009) to build a cubic water slab with a 3.3 nm edge, the simulation box, consisting of 1000 water molecules with a tolerance of 2.0 Å (minimum interatomic distance). And the simulation box was expanded to 3.3 × 3.3 × 16 nm3 along the z-axis to build the vacuum layers, forming the air-water interface. Umbrella sampling was employed, and a harmonic bias of 5000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 was applied to I2O5 molecule along the z-axis to investigate its free energy profile crossing the air-water interface from bulk water into gas phase. Furthermore, the generalized AMBER force field (GAFF) (Wang et al., 2004) with parameters obtained from the Sobtop 1.0 code (Lu, 2024) was combined with the TIP4P water model (Jorgensen et al., 1983) to describe the driving forces in the MD simulations. The restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) method (Bayly et al., 1993) was used to fit the atomic charges using the Multiwfn 3.7 code (Lu and Chen, 2012). Prior to MD simulations, the energy minimization of the system was performed by the steepest descent algorithm. The MD simulations were carried out in the constant volume and temperature (NVT) ensemble, with the temperature controlled at 300 K by the Nosé–Hoover thermostat (Evans and Holian, 1985). A time step of 2.0 fs was employed for all MD simulations. Lennard–Jones (LJ) and Coulomb potentials were used to simulate nonbonded interactions, with the electrostatic interactions calculated using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) summation method (Darden et al., 1993) and a 10 Å real-space cutoff for nonbonded interactions. The hydrogen-involved bonds were treated via the LINCS algorithm (Hess et al., 1997). In each umbrella sampling window, the system was equilibrated for 5 ns. The free-energy profile was calculated by the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) (Kumar et al., 1992).

2.3 BOMD Simulations

To explore the interfacial reaction of I2O5, the underlying mechanism was studied by BOMD and the stepwise multi-subphase space metadynamics (SMS-MetaD) (Fang et al., 2022) simulations using the CP2K 2022 program (Kühne et al., 2020) combined with PLUMED software (Bussi and Tribello, 2019). The SMS-MetaD method is well-suited for effectively modeling chemical systems with complex potential energy surface, especially at the air-water interface (Fang et al., 2022), which has already been successfully employed in the studies of heterogeneous reactions (Fang et al., 2024a, b; Tang et al., 2024; Wan et al., 2023). The QUICKSTEP module was applied with the Gaussian and plane wave (GPW) method, and the electronic exchange–correlation term was described by the BLYP-D3 functional (Perdew and Wang, 1992). The DZVP-MOLOPT-SR-GTH basis set and Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials (Goedecker et al., 1996; Hartwigsen et al., 1998) were adopted here. The plane-wave cutoff was set to 280 Ry, and that for Gaussian was 40 Ry. All BOMD simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble, with the temperature controlled at 300 K by the Nosé–Hoover thermostat (Evans and Holian, 1985), and the time step was set to 1.0 fs. The dimensions of 3-D periodic cell are x=18 Å, y=18 Å, and z=30 Å, in which the water slab containing 128 H2O was fully relaxed to reach a statistical equilibrium for temperature and potential energy (see Fig. S4). To probe the reaction barriers of I2O5 hydrolysis mediated by different chemicals, a series of SMS-MetaD simulations were carried out. In the SMS-MetaD simulations, collective variable (CV), as the key parameter, was set to effectively differentiate distinct states (Figs. S3 and S8–S9), with its upper and lower limits referring to the interfacial behavior observed in unbiased simulations (see more details in the Supplement). Gaussian hills with adaptive heights and sigma widths of 0.1 Å were deposited every 50 steps to efficiently explore the free energy landscape and accelerate the convergence (Figs. S10–S13). And block average analysis was performed to assess the error associated with the calculated reaction barriers (Fig. S14). The wave function analysis and visualization of key structures from the BOMD simulations were carried out using VMD 1.9.3 (Humphrey et al., 1996) and Multiwfn 3.7 software (Lu and Chen, 2012).

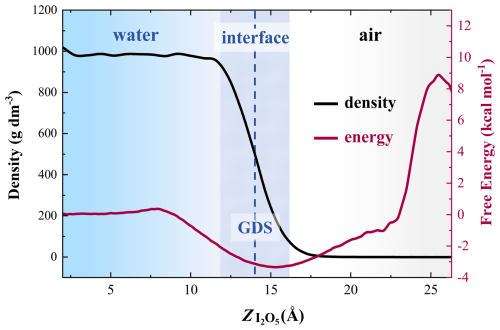

3.1 Surface Preference

The interfacial preference of I2O5 influences whether its heterogeneous reactions can effectively occur. Herein, umbrella sampling was applied to obtain the free energy profile of I2O5 from the bulk water to the air along the Z direction, where I2O5 was initially placed in the center of water layer. As shown in Fig. 1, the air-water interface is defined as the region with 10 %–90 % of the bulk density, delineated by the two dashed lines. As I2O5 moves from the bulk water into air across the interface, the free energy first decreases and then increases, reaching the lowest values near the Gibbs dividing surface (GDS, the blue dash line). The results show that I2O5 has an evident preference for aqueous surface, suggesting its potential to react with other chemicals at the air-water interface.

Figure 1Interfacial propensity of I2O5. Mass density (g dm−3) of the water (black line); the free energy of I2O5 (purple line) along the z axis (Å). The vertical dashed line indicates the Gibbs dividing surface (GDS), which corresponds to a location with half of the bulk density. The shaded region represents the air-water interface (10 %–90 % of bulk density).

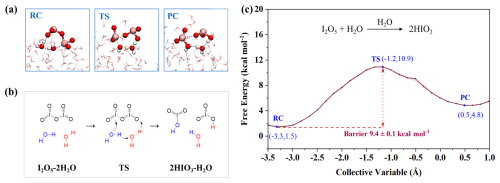

3.2 H2O-Mediated Interfacial Hydrolysis of I2O5

Experimental evidence (Gómez Martín et al., 2022a) has confirmed a high reactivity of I2O5 in the presence of H2O, which stands in contrast to theoretical predictions based on gas-phase reactions (Khanniche et al., 2016; Xia et al., 2020). To address this gap, we first probed unexplored heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5 at the air-water interface by the BOMD simulations. The results indicate no apparent tendency for I2O5 to react with interfacial H2O to form HIO3 in the unbiased BOMD simulation within 50 ps (Fig. S7), implying that this process may involve an energy barrier. Accordingly, the enhanced sampling (i.e., SMS-MetaD) simulations were further performed to examine the interfacial reactions of I2O5 and to quantify the associated reaction barrier (see CV settings in the Supplement). Figure 2a–b illustrates the process of I2O5 hydrolysis, where the reaction initiates with proton (H+) transfer from H2O to I2O5 facilitated by another H2O as a “bridge”. Then I2O5 binds with H+ to form the intermediate HI2O, with the system existing in a quasi-transition state (TS). Subsequently the I–O bond in the HI2O breaks, and the OIO+ motif quickly combines with the OH− to form a HIO3, leaving another HIO3. Figure 2c presents the free energy profile for the interfacial hydrolysis of I2O5, showing a reaction barrier of ∼ 9.4 kcal mol−1 upon convergence of the results (Fig. S10), with ±0.1 kcal mol−1 error as indicated by the block analysis (see more details in the Supplement), which is lower than that of the reported corresponding gas-phase reaction (13.6 kcal mol−1) (Xia et al., 2020). However, this barrier remains considerable, limiting the direct heterogeneous hydrolysis from proceeding rapidly. The previous study (Kumar et al., 2018) reported the formation of H2I2O6 from the reaction of I2O5 with interfacial water and indicated its dynamic stability over a 35 ps simulation period. However, H2I2O6 was unfortunately not observed in the reported iodine-related experimental and field studies (Gómez Martín et al., 2020, 2022a; He et al., 2021, 2023; Rörup et al., 2024; Sipilä et al., 2016), nor was it observed in our unbiased BOMD simulations. Thus, the H2O-mediated heterogeneous mechanism still faces challenges in representing the identified I2O5-to-HIO3 conversion, pointing to the faster pathways mediated by other chemicals responsible for the absence of I2O5 in the experimental or field observations.

Figure 2Details of H2O-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (a) Snapshot structures of SMS-MetaD simulation representing reactant complex (RC), transition state (TS), and product complex (PC). The pink, red and white spheres represent I, O, and H atoms, respectively (the same applies in Figs. 3–6 below). (b) Reaction mechanism for the H2O-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. Blue molecular indicates the water involved in hydrolysis, black one indicates the I2O5, red one indicates the catalyst. The arrows indicate the direction of atom transfer (the same below). (c) Free energy profile for I2O5 hydrolysis at the air-water interface mediated by H2O (black line) with the error band (pink region).

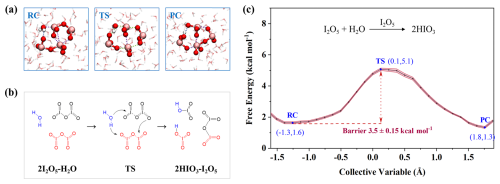

3.3 Self-Mediated Hydrolysis of I2O5

Given that H2O-mediated hydrolysis is inefficient, we next explored whether leftover I2O5 can self-catalyze a faster reaction – a critical question for explaining its atmospheric depletion. During the unbiased BOMD simulation, two I2O5 molecules combined together to form iodine oxide complex (I2O5⋯I2O5) via intermolecular halogen bond (XB), without undergoing hydrolysis within 50 ps (Fig. S7). Further SMS-MetaD simulations, shown in Fig. 3a–b, present the mechanistic details of this hydrolysis. The I2O5⋯I2O5 complex initially binds a H2O molecule via hydrogen bond (HB) and XB, forming a three-membered ring. Next, the H2O molecule dissociates into OH− and H+, each approaching a distinct I2O5. Meanwhile, the H2O-involved HB (O–H⋯O) and XB (O–I⋯O) generally converted into new H–O and I–O covalent bonds, resulting in the formation of two HIO3 molecules. And the residual OIO and IO3 of the two I2O5 molecules combined to form a new I2O5, finalizing the self-catalyzed reaction. As shown in Fig. 3c, the resulting reaction barrier is 3.5 kcal mol−1, which is 5.9 kcal mol−1 lower than that of H2O-catalyzed mechanism. The results suggest that I2O5 facilitates its own hydrolysis more pronouncedly than H2O. Thus, the I2O5-mediated mechanism efficiently drives I2O5-to-HIO3 conversion, resolving the earlier paradox of I2O5's stability yet absence in the atmosphere – and explaining the high HIO3 levels in marine aerosols.

Figure 3Details of I2O5-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (a) Snapshot structures of SMS-MetaD simulation representing RC, TS, and PC. (b) Reaction mechanism for the I2O5-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (c) Free energy profile for I2O5 hydrolysis at the air-water interface mediated by I2O5 (black line) with the error band (pink region).

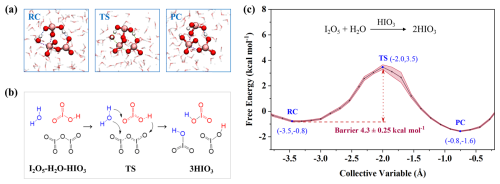

3.4 HIO3-Mediated Interfacial Hydrolysis of I2O5

We further performed SMS-MetaD simulations to explore the interfacial reaction mediated by the product HIO3, due to its widespread presence in gas and aerosol phase. And HIO3 possesses both proton donor and acceptor sites, potentially facilitating proton transfer, which is a key step in I2O5 hydrolysis. As shown in Fig. 4a–b, H+ transfers from H2O to HIO3, then HIO3 donates H+ to I2O5, finally yielding two new HIO3. The resulting energy barrier of this process is ∼ 4.3 kcal mol−1 (Fig. 4c), slightly higher than that mediated by I2O5 (3.5 kcal mol−1). However, given the high concentration and widespread distribution of HIO3 over oceans, its role in mediating hydrolysis of I2O5 should be fully considered. Moreover, as this reaction proceeds, the product HIO3 accumulates to further catalyze the reaction, establishing positive feedback. Thus, in the pristine iodine-rich region such as Mace Head, with HIO3 concentrations as high as 108 molec. cm−3 (Sipilä et al., 2016) the HIO3-catalyzed heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5 may represent its primary loss pathway. This may help explain why I2O5, though hypothesized to be involved in aerosol formation, is not observed in mass spectra, where iodate signals appear instead.

Figure 4Details of HIO3-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (a) Snapshot structures of SMS-MetaD simulation representing RC, TS, and PC. (b) Reaction mechanism for the HIO3-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (c) Free energy profile for I2O5 hydrolysis at the air-water interface mediated by HIO3 (black line) with the error band (pink region).

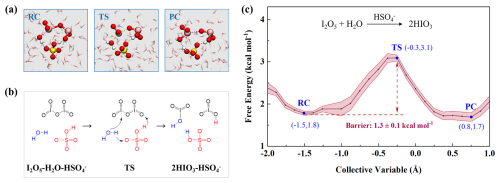

3.5 Sulfuric Acid-Mediated Interfacial Hydrolysis of I2O5

In fact, I2O5 seems not only absent over pristine oceans but also in polluted marine environments. For example, along the eastern coast of China (e.g., Zhejiang), bursts of iodine-bearing aerosols were observed, featuring high levels of IO, without I2O5 signal detected (Yu et al., 2019). Despite the proposed conversion of hydrated I2O5 to HIO3 (detected as IO) (Gómez Martín et al., 2022a), the underlying mechanism remains unclear, especially under the impacts of pollutants. Notably, HSO (ionization of typical acidic pollutant H2SO4) was also detected at considerable concentrations within iodine aerosols. Accordingly, we explored the H2SO4-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5 at the molecular level. As a strong acid (pK), H2SO4 can rapidly lose a proton to form HSO at the air-water interface, which has a surface preference (Hua et al., 2015). At this stage, HSO loses strong acidity and shows dissociation equilibrium, thus serving as a proton-transfer bridge. As shown in Fig. 5b, H+ initially moves from HSO to I2O5, meanwhile, the H atom of H2O is attracted by SO and remains the OH−, leading to I–O bond breaking, forming two HIO3 molecules. This process couples the self-dissociation of HSO and the hydrolysis of I2O5, expected to occur efficiently on aqueous surface, owing to its lower barrier (∼ 1.3 kcal mol−1) than that mediated by I2O5 (3.5 kcal mol−1). The findings indicate that HSO-mediated pathway may play an important role in I2O5 depletion under polluted conditions, thereby providing mechanistic insights into the absence of I2O5 and the coexistence of HSO and IO in field-collected aerosols (Yu et al., 2019). To further quantify the efficiency of these reactions, we calculated the reaction rate constants through Transition State Theory (Table S1). Notably, the hydrolysis of I2O5 mediated by I2O5 or HIO3 proceeds 4–5 orders of magnitude faster than that mediated by H2O, but still more slowly (1–2 orders of magnitude) than that mediated by H2SO4. These results highlight the significance of intercomponent coupling in enhancing heterogeneous iodine chemistry in marine atmospheres, from pristine to polluted.

Figure 5Details of SA-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (a) Snapshot structures of SMS-MetaD simulation representing RC, TS, and PC. Yellow atoms represent S. (b) Reaction mechanism for the SA-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (c) Free energy profile for I2O5 hydrolysis at the air-water interface mediated by SA (black line) with the error band (pink region).

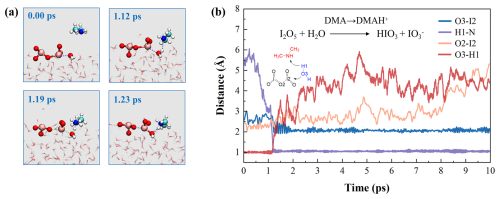

3.6 Amine-Mediated Interfacial Hydrolysis of I2O5

Aside from acid pollutants, atmospheric bases may also affect interfacial chemistry under polluted conditions. Amines, as the typical bases, exhibit evident surface preference and the potential to affect hydrolysis of iodine oxides at the air-water interface (Ning et al., 2024). Accordingly, we investigated the amine-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. Figure 6 shows the DMA-involved key structural snapshots and time-dependent evolution of key bond distances. Initially, DMA is positioned in the gas phase, without notable interaction with aqueous surface. Over time, DMA gradually approaches interfacial water to form HB (O3–H1⋯N). At 1.12 ps, interfacial water bridges I2O5 and DMA via HB (O3–H1⋯N) and XB (O2–I2⋯O3), forming a pre-reaction complex. By 1.19 ps, the covalent bond between the H1 and O3 elongated, forming a TS-like structure, then proton H1 transfers from H2O to DMA. The deprotonated H2O molecule, generating OH−, immediately approaches the I2 atom of I2O5. The I–O bond in I2O5 gradually changes from covalent bond into XB, ultimately yielding HIO3 and IO (Fig. S18). By 1.23 ps, the reaction ends to form HIO3, IO, and alkylammonium salts (DMAH+). The BOMD results indicate that the DMA-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5 occurs rapidly on a picosecond timescale, thus attesting to a barrierless pathway. Also, we studied the MA- and TMA-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5, which shows similar capabilities of other amines like MA and TMA to accelerate this process (see Figs. S5 and S6). Accordingly, in polluted environments, the role of pollutants in activating iodine chemistry should not be overlooked, as their mediation of rapid heterogeneous processes likely affects aerosol composition and growth dynamics.

Figure 6Details of DMA-mediated hydrolysis of I2O5. (a) Snapshot structures of BOMD simulation, which illustrate the mechanism for this process. The dashed lines indicate the intermolecular interactions (hydrogen or halogen bonding). Blue and cyan atoms represent N and C atoms, respectively. (b) Time evolution of key bond distances (O3–I2, H1–N, O2–I2, and O3–H1). The arrows indicate the direction of atom transfer.

In addition to the above analysis of the reaction mechanism and energy barriers, we further explored how interfacial hydrolysis of I2O5 affects aerosol growth (Scheme 1) through analysis of dynamic trajectories and wave function of key structures. Here, the DMA-mediated process is taken as an example (see details in the Supplement). The resulting products (HIO3, IO, and DMAH+) are partially solvated, as they are surrounded by interfacial water (Figs. S15 and S16) via HBs and XBs but still exposed outside to air with unoccupied HB or XB sites (Fig. S17). These HB and XB interactions serve the following roles: (i) stabilizing the product complex by preventing its decomposition via intermolecular interactions within complex; (ii) inhibiting evaporation of product via interactions with interfacial water; (iii) promoting aerosol growth by unoccupied HB or XB sites for uptake of gaseous species, in particular, the hydrophilic ionic products (e.g., MAH+, DMAH+, and TMAH+) accelerate water condensation. Thus, the chemisorption of I2O5 contributes to aerosol growth not only directly, by yielding low-volatility products, but also indirectly by enhancing hygroscopic growth. Understanding the impacts of these heterogeneous reactions and the resulting products may advance our knowledge of how iodine oxides influence iodate aerosol formation.

Iodine chemicals are closely linked to marine aerosol formation; however, the underlying physicochemical process, especially involving higher-order iodine oxides (e.g., I2Ox, x≥2), remains highly uncertain. HIO3 is widely detected in marine aerosols, while I2O5 is absent, pointing to a potential I2O5-to-HIO3 conversion, although the mechanism is still elusive. To address this, we have investigated interfacial hydrolysis of I2O5, the typical I2Ox, on aqueous aerosol surfaces at the molecular level by BOMD and SMS-MetaD simulations. The results show that I2O5 uptakes directly onto the pure water surface, where the interfacial hydrolysis proceeds slowly (I2O5+ H2O HIO3 in Fig. 2). And the self-catalyzed pathways involving I2O5 (reactant) and HIO3 (product) notably lower the energy barrier and facilitate the reaction. Thus, in pristine marine environments, the proposed I2O5- and HIO3-mediated heterogeneous mechanisms (Figs. 3 and 4) potentially serve as both an important sink for I2O5 and a source of HIO3, which helps clarify the chemical speciation of field-collected iodine aerosols. In contrast, in polluted regions, pollutant-mediated pathways – with barriers as low as 1.3 kcal mol−1 (H2SO4-mediated) or even barrierless (amine-mediated) – dominate over self-catalyzed processes, driving faster I2O5 interfacial hydrolysis and yielding HIO3, which helps to elucidate the rapid formation of iodate aerosols observed in polluted eastern coast of China (Yu et al., 2019). It also highlights the role of air pollutants in activating iodine chemistry. Accordingly, these heterogeneous mechanisms can advance our understanding of the roles of I2O5 in iodine chemistry, which may help explain the well-established but mechanistically elusive I2O5-to-HIO3 conversion. Notably, the hydrolysis products (i.e. HIO3 and ionic species) enhance aerosol growth through their low volatility, unoccupied HB/XB sites, and hygroscopicity – linking I2O5 hydrolysis directly to aerosol growth. These insights deepen our understanding of how iodine oxide affects aerosol formation – both directly and indirectly – in both pristine and polluted marine environments.

Altogether, this study highlights the critical role of heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5 mediated by some important chemicals in iodine chemistry and aerosol growth. Here, we find that intercomponent coupling – i.e., interactions of iodine oxides with themselves, iodic acids, and atmospheric pollutants – is a key, yet frequently overlooked factor that can reshape heterogeneous iodine chemistry across environments, where the reactive pollutant-mediated processes outcompete self-catalyzed pathways. These findings can help explain the observed but poorly understood I2O5 and HIO3 distribution, as well as their chemical conversion, which sheds light on iodine aerosol growth. The iodine-driven impacts are likely global and expected to grow, due to rapidly increasing oceanic iodine emissions. Accordingly, integrating these proposed mechanisms into atmospheric models is expected to reduce uncertainties (unrecognized sink or source for iodine oxides and iodine oxyacids) arising from iodine oxides, which can refine the representation of iodine cycling and further improve the assessment of globally environmental and climatic effects (like aerosol-driven radiative forcing) driven by atmospheric iodine aerosols. The real atmosphere is chemically complex, including iodine species (e.g. HOI, HIO2, HIO3, I2O3, I2O4, and I2O5) and atmospheric pollutants (e.g. H2SO4, HNO3, organic acids, and ammonia), which are likely to influence the heterogeneous hydrolysis of I2O5. In future work, we intend to confirm the impacts from other atmospheric components.

The data in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (anning@bit.edu.cn and zhangxiuhui@bit.edu.cn).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-477-2026-supplement.

XZ designed and supervised the research. XD and AN performed the quantum chemical calculations and the BOMD simulations. XD, AN, JL and LL analyzed data. XD, AN, and XZ wrote the paper. FB, JY, and JRL reviewed the paper. All authors commented on the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We acknowledge financial support from the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

This work is supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (grant no. 22225607) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22306011 and 22376013).

This paper was edited by Qiang Zhang and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Allan, J. D., Williams, P. I., Najera, J., Whitehead, J. D., Flynn, M. J., Taylor, J. W., Liu, D., Darbyshire, E., Carpenter, L. J., Chance, R., Andrews, S. J., Hackenberg, S. C., and McFiggans, G.: Iodine observed in new particle formation events in the Arctic atmosphere during ACCACIA, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5599–5609, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5599-2015, 2015.

Barnes, I., Hjorth, J., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Dimethyl Sulfide and Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Their Oxidation in the Atmosphere, Chem. Rev., 106, 940–975, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020529+, 2006.

Bayly, C. I., Cieplak, P., Cornell, W., and Kollman, P. A.: A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model, J. Phys. Chem., 97, 10269–10280, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100142a004, 1993.

Bussi, G. and Tribello, G. A.: Analyzing and Biasing Simulations with PLUMED, in: Methods in Molecular Biology, Springer New York, New York, NY, 529–578, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9608-7_21, 2019.

Carpenter, L. J., Chance, R. J., Sherwen, T., Adams, T. J., Ball, S. M., Evans, M. J., Hepach, H., Hollis, L. D. J., Hughes, C., Jickells, T. D., Mahajan, A., Stevens, D. P., Tinel, L., and Wadley, M. R.: Marine iodine emissions in a changing world, Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 477, 20200824, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2020.0824, 2021.

Chen, Q., Sherwen, T., Evans, M., and Alexander, B.: DMS oxidation and sulfur aerosol formation in the marine troposphere: a focus on reactive halogen and multiphase chemistry, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 13617–13637, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-13617-2018, 2018.

Darden, T., York, D., and Pedersen, L.: Particle mesh Ewald: An Nlog(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems, J. Chem. Phys., 98, 10089–10092, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464397, 1993.

Droste, E. S., Baker, A. R., Yodle, C., Smith, A., and Ganzeveld, L.: Soluble Iodine Speciation in Marine Aerosols Across the Indian and Pacific Ocean Basins, Front. Mar. Sci., 8, 788105, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.788105, 2021.

Evans, D. J. and Holian, B. L.: The Nose–Hoover thermostat, J. Chem. Phys., 83, 4069–4074, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.449071, 1985.

Fang, Y.-G., Li, X., Gao, Y., Cui, Y.-H., Francisco, J. S., Zhu, C., and Fang, W.-H.: Efficient exploration of complex free energy landscapes by stepwise multi-subphase space metadynamics, J. Chem. Phys., 157, 214111, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0098269, 2022.

Fang, Y.-G., Tang, B., Yuan, C., Wan, Z., Zhao, L., Zhu, S., Francisco, J. S., Zhu, C., and Fang, W.-H.: Mechanistic insight into the competition between interfacial and bulk reactions in microdroplets through N2O5 ammonolysis and hydrolysis, Nat. Commun., 15, 2347, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46674-1, 2024a.

Fang, Y.-G., Wei, L., Francisco, J. S., Zhu, C., and Fang, W.-H.: Mechanistic Insights into Chloric Acid Production by Hydrolysis of Chlorine Trioxide at an Air–Water Interface, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 146, 21052–21060, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c06269, 2024b.

Finkenzeller, H., Iyer, S., He, X.-C., Simon, M., Koenig, T. K., Lee, C. F., Valiev, R., Hofbauer, V., Amorim, A., Baalbaki, R., Baccarini, A., Beck, L., Bell, D. M., Caudillo, L., Chen, D., Chiu, R., Chu, B., Dada, L., Duplissy, J., Heinritzi, M., Kemppainen, D., Kim, C., Krechmer, J., Kürten, A., Kvashnin, A., Lamkaddam, H., Lee, C. P., Lehtipalo, K., Li, Z., Makhmutov, V., Manninen, H. E., Marie, G., Marten, R., Mauldin, R. L., Mentler, B., Müller, T., Petäjä, T., Philippov, M., Ranjithkumar, A., Rörup, B., Shen, J., Stolzenburg, D., Tauber, C., Tham, Y. J., Tomé, A., Vazquez-Pufleau, M., Wagner, A. C., Wang, D. S., Wang, M., Wang, Y., Weber, S. K., Nie, W., Wu, Y., Xiao, M., Ye, Q., Zauner-Wieczorek, M., Hansel, A., Baltensperger, U., Brioude, J., Curtius, J., Donahue, N. M., Haddad, I. E., Flagan, R. C., Kulmala, M., Kirkby, J., Sipilä, M., Worsnop, D. R., Kurten, T., Rissanen, M., and Volkamer, R.: The gas-phase formation mechanism of iodic acid as an atmospheric aerosol source, Nat. Chem., 15, 129–135, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-022-01067-z, 2023.

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Li, X., Caricato, M., Marenich, A. V., Bloino, J., Janesko, B. G., Gomperts, R., Mennucci, B., Hratchian, H. P., Ortiz, J. V., Izmaylov, A. F., Sonnenberg, J. L., Ding, F., Lipparini, F., Egidi, F., Goings, J., Peng, B., Petrone, A., Henderson, T., Ranasinghe, D., Zakrzewski, V. G., Gao, J., Rega, N., Zheng, G., Liang, W., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Throssell, K., Montgomery, J. A., Jr., Peralta, J. E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M. J., Heyd, J. J., Brothers, E. N., Kudin, K. N., Staroverov, V. N., Keith, T. A., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A. P., Burant, J. C., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Millam, J. M., Klene, M., Adamo, C., Cammi, R., Ochterski, J. W., Martin, R. L., Morokuma, K., Farkas, O., Foresman, J. B., and Fox, D. J.: Gaussian 16, Rev. A.01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT [code], https://gaussian.com/gaussian16/ (last access: 18 January 2024), 2016.

Gettelman, A. and Kahn, R.: Aerosols are critical for “nowcasting” climate, One Earth, 101239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2025.101239, 2025.

Goedecker, S., Teter, M., and Hutter, J.: Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials, Phys. Rev. B, 54, 1703–1710, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.54.1703, 1996.

Gómez Martín, J. C., Gálvez, O., Baeza-Romero, M. T., Ingham, T., Plane, J. M. C., and Blitz, M. A.: On the mechanism of iodine oxide particle formation, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 15, 15612, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cp51217g, 2013.

Gómez Martín, J. C., Lewis, T. R., Blitz, M. A., Plane, J. M. C., Kumar, M., Francisco, J. S., and Saiz-Lopez, A.: A gas-to-particle conversion mechanism helps to explain atmospheric particle formation through clustering of iodine oxides, Nat. Commun., 11, 4521, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18252-8, 2020.

Gómez Martín, J. C., Saiz-Lopez, A., Cuevas, C. A., Fernandez, R. P., Gilfedder, B., Weller, R., Baker, A. R., Droste, E., and Lai, S.: Spatial and Temporal Variability of Iodine in Aerosol, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2020JD034410, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD034410, 2021.

Gómez Martín, J. C., Lewis, T. R., James, A. D., Saiz-Lopez, A., and Plane, J. M. C.: Insights into the Chemistry of Iodine New Particle Formation: The Role of Iodine Oxides and the Source of Iodic Acid, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 144, 9240–9253, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c12957, 2022a.

Gómez Martín, J. C., Saiz-Lopez, A., Cuevas, C. A., Baker, A. R., and Fernández, R. P.: On the Speciation of Iodine in Marine Aerosol, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 127, e2021JD036081, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD036081, 2022b.

Hartwigsen, C., Goedecker, S., and Hutter, J.: Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn, Phys. Rev. B, 58, 3641–3662, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.58.3641, 1998.

He, X.-C., Tham, Y. J., Dada, L., Wang, M., Finkenzeller, H., Stolzenburg, D., Iyer, S., Simon, M., Kürten, A., Shen, J., Rörup, B., Rissanen, M., Schobesberger, S., Baalbaki, R., Wang, D. S., Koenig, T. K., Jokinen, T., Sarnela, N., Beck, L. J., Almeida, J., Amanatidis, S., Amorim, A., Ataei, F., Baccarini, A., Bertozzi, B., Bianchi, F., Brilke, S., Caudillo, L., Chen, D., Chiu, R., Chu, B., Dias, A., Ding, A., Dommen, J., Duplissy, J., El Haddad, I., Gonzalez Carracedo, L., Granzin, M., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Hofbauer, V., Junninen, H., Kangasluoma, J., Kemppainen, D., Kim, C., Kong, W., Krechmer, J. E., Kvashin, A., Laitinen, T., Lamkaddam, H., Lee, C. P., Lehtipalo, K., Leiminger, M., Li, Z., Makhmutov, V., Manninen, H. E., Marie, G., Marten, R., Mathot, S., Mauldin, R. L., Mentler, B., Möhler, O., Müller, T., Nie, W., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Pfeifer, J., Philippov, M., Ranjithkumar, A., Saiz-Lopez, A., Salma, I., Scholz, W., Schuchmann, S., Schulze, B., Steiner, G., Stozhkov, Y., Tauber, C., Tomé, A., Thakur, R. C., Väisänen, O., Vazquez-Pufleau, M., Wagner, A. C., Wang, Y., Weber, S. K., Winkler, P. M., Wu, Y., Xiao, M., Yan, C., Ye, Q., Ylisirniö, A., Zauner-Wieczorek, M., Zha, Q., Zhou, P., Flagan, R. C., Curtius, J., Baltensperger, U., Kulmala, M., Kerminen, V.-M., Kurtén, T., Donahue, N. M., Volkamer, R., Kirkby, J., Worsnop, D. R., and Sipilä, M.: Role of iodine oxoacids in atmospheric aerosol nucleation, Science, 371, 589–595, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe0298, 2021.

He, X.-C., Simon, M., Iyer, S., Xie, H.-B., Rörup, B., Shen, J., Finkenzeller, H., Stolzenburg, D., Zhang, R., Baccarini, A., Tham, Y. J., Wang, M., Amanatidis, S., Piedehierro, A. A., Amorim, A., Baalbaki, R., Brasseur, Z., Caudillo, L., Chu, B., Dada, L., Duplissy, J., El Haddad, I., Flagan, R. C., Granzin, M., Hansel, A., Heinritzi, M., Hofbauer, V., Jokinen, T., Kemppainen, D., Kong, W., Krechmer, J., Kürten, A., Lamkaddam, H., Lopez, B., Ma, F., Mahfouz, N. G. A., Makhmutov, V., Manninen, H. E., Marie, G., Marten, R., Massabò, D., Mauldin, R. L., Mentler, B., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Pfeifer, J., Philippov, M., Ranjithkumar, A., Rissanen, M. P., Schobesberger, S., Scholz, W., Schulze, B., Surdu, M., Thakur, R. C., Tomé, A., Wagner, A. C., Wang, D., Wang, Y., Weber, S. K., Welti, A., Winkler, P. M., Zauner-Wieczorek, M., Baltensperger, U., Curtius, J., Kurtén, T., Worsnop, D. R., Volkamer, R., Lehtipalo, K., Kirkby, J., Donahue, N. M., Sipilä, M., and Kulmala, M.: Iodine oxoacids enhance nucleation of sulfuric acid particles in the atmosphere, Science, 382, 1308–1314, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh2526, 2023.

Hess, B., Bekker, H., Berendsen, H. J. C., and Fraaije, J. G. E. M.: LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations, J. Comput. Chem., 18, 1463–1472, https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-987x(199709)18:12<1463::aid-jcc4>3.0.co;2-h, 1997.

Hua, W., Verreault, D., and Allen, H. C.: Relative Order of Sulfuric Acid, Bisulfate, Hydronium, and Cations at the Air–Water Interface, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 137, 13920–13926, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b08636, 2015.

Huang, R.-J., Hoffmann, T., Ovadnevaite, J., Laaksonen, A., Kokkola, H., Xu, W., Xu, W., Ceburnis, D., Zhang, R., Seinfeld, J. H., and O'Dowd, C.: Heterogeneous iodine-organic chemistry fast-tracks marine new particle formation, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 119, e2201729119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2201729119, 2022.

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A., and Schulten, K.: VMD: Visual molecular dynamics, J. Mol. Graph., 14, 33–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5, 1996.

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W., and Klein, M. L.: Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water, J. Chem. Phys., 79, 926–935, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.445869, 1983.

Kaloshin, G. A.: Modeling the Aerosol Extinction in Marine and Coastal Areas, IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett., 18, 376–380, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2020.2980866, 2021.

Kaltsoyannis, N. and Plane, J. M. C.: Quantum chemical calculations on a selection of iodine-containing species (IO, OIO, INO3, (IO)2, I2O3, I2O4 and I2O5) of importance in the atmosphere, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 10, 1723, https://doi.org/10.1039/b715687c, 2008.

Kendall, R. A., Dunning, T. H., and Harrison, R. J.: Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions, J. Chem. Phys., 96, 6796–6806, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.462569, 1992.

Khanniche, S., Louis, F., Cantrel, L., and Černušák, I.: Computational study of the I2O5+ H2O = 2 HOIO2 gas-phase reaction, Chem. Phys. Lett., 662, 114–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2016.09.023, 2016.

Kim, M. and Yoo, C.-S.: Phase transitions in I2O5 at high pressures: Raman and X-ray diffraction studies, Chem. Phys. Lett., 648, 13–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2016.01.043, 2016.

Kühne, T. D., Iannuzzi, M., Del Ben, M., Rybkin, V. V., Seewald, P., Stein, F., Laino, T., Khaliullin, R. Z., Schütt, O., Schiffmann, F., Golze, D., Wilhelm, J., Chulkov, S., Bani-Hashemian, M. H., Weber, V., Borštnik, U., Taillefumier, M., Jakobovits, A. S., Lazzaro, A., Pabst, H., Müller, T., Schade, R., Guidon, M., Andermatt, S., Holmberg, N., Schenter, G. K., Hehn, A., Bussy, A., Belleflamme, F., Tabacchi, G., Glöß, A., Lass, M., Bethune, I., Mundy, C. J., Plessl, C., Watkins, M., VandeVondele, J., Krack, M., and Hutter, J.: CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package – Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations, J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0007045, 2020.

Kumar, M., Saiz-Lopez, A., and Francisco, J. S.: Single-Molecule Catalysis Revealed: Elucidating the Mechanistic Framework for the Formation and Growth of Atmospheric Iodine Oxide Aerosols in Gas-Phase and Aqueous Surface Environments, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 140, 14704–14716, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b07441, 2018.

Kumar, S., Rosenberg, J. M., Bouzida, D., Swendsen, R. H., and Kollman, P. A.: THE weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method, J. Comput. Chem., 13, 1011–1021, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.540130812, 1992.

Leroy, O. and Bosland, L.: Study of the stability of iodine oxides (IxOy) aerosols in severe accident conditions, Ann. Nucl. Energy, 181, 109526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2022.109526, 2023.

Lewis, T. R., Gómez Martín, J. C., Blitz, M. A., Cuevas, C. A., Plane, J. M. C., and Saiz-Lopez, A.: Determination of the absorption cross sections of higher-order iodine oxides at 355 and 532 nm, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 10865–10887, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-10865-2020, 2020.

Li, J., Wu, N., Chu, B., Ning, A., and Zhang, X.: Molecular-level study on the role of methanesulfonic acid in iodine oxoacid nucleation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 3989–4000, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-3989-2024, 2024.

Li, Q., Tham, Y. J., Fernandez, R. P., He, X., Cuevas, C. A., and Saiz-Lopez, A.: Role of Iodine Recycling on Sea-Salt Aerosols in the Global Marine Boundary Layer, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2021GL097567, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL097567, 2022.

Liang, Y., Rong, H., Liu, L., Zhang, S., Zhang, X., and Xu, W.: Gas-phase catalytic hydration of I2O5 in the polluted coastal regions: Reaction mechanisms and atmospheric implications, J. Environ. Sci., 114, 412–421, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.09.028, 2022.

Liu, L., Li, S., Zu, H., and Zhang, X.: Unexpectedly significant stabilizing mechanism of iodous acid on iodic acid nucleation under different atmospheric conditions, Sci. Total Environ., 859, 159832, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159832, 2023.

Lu, T.: Sobtop, Version 1.0 (dev5), http://sobereva.com/soft/Sobtop (last access: 5 July 2025), 2024.

Lu, T. and Chen, F.: Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer, J. Comput. Chem., 33, 580–592, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.22885, 2012.

Mahowald, N. M., Hamilton, D. S., Mackey, K. R. M., Moore, J. K., Baker, A. R., Scanza, R. A., and Zhang, Y.: Aerosol trace metal leaching and impacts on marine microorganisms, Nat. Commun., 9, 2614, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04970-7, 2018.

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G., and Martínez, J. M.: PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations, J. Comput. Chem., 30, 2157–2164, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21224, 2009.

McFiggans, G., Bale, C. S. E., Ball, S. M., Beames, J. M., Bloss, W. J., Carpenter, L. J., Dorsey, J., Dunk, R., Flynn, M. J., Furneaux, K. L., Gallagher, M. W., Heard, D. E., Hollingsworth, A. M., Hornsby, K., Ingham, T., Jones, C. E., Jones, R. L., Kramer, L. J., Langridge, J. M., Leblanc, C., LeCrane, J.-P., Lee, J. D., Leigh, R. J., Longley, I., Mahajan, A. S., Monks, P. S., Oetjen, H., Orr-Ewing, A. J., Plane, J. M. C., Potin, P., Shillings, A. J. L., Thomas, F., von Glasow, R., Wada, R., Whalley, L. K., and Whitehead, J. D.: Iodine-mediated coastal particle formation: an overview of the Reactive Halogens in the Marine Boundary Layer (RHaMBLe) Roscoff coastal study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 2975–2999, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-2975-2010, 2010.

Ning, A. and Zhang, X.: The synergistic effects of methanesulfonic acid (MSA) and methanesulfinic acid (MSIA) on marine new particle formation, Atmos. Environ., 269, 118826, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118826, 2022.

Ning, A., Zhong, J., Li, L., Li, H., Liu, J., Liu, L., Liang, Y., Li, J., Zhang, X., Francisco, J. S., and He, H.: Chemical Implications of Rapid Reactive Absorption of I2O4 at the Air-Water Interface, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 145, 10817–10825, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c01862, 2023.

Ning, A., Li, J., Du, L., Yang, X., Liu, J., Yang, Z., Zhong, J., Saiz-Lopez, A., Liu, L., Francisco, J. S., and Zhang, X.: Heterogenous Chemistry of I2O3 as a Critical Step in Iodine Cycling, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 146, 33229–33238, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c13060, 2024.

O'Dowd, C. D. and De Leeuw, G.: Marine aerosol production: a review of the current knowledge, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 365, 1753–1774, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2007.2043, 2007.

O'Dowd, C. D., Jimenez, J. L., Bahreini, R., Flagan, R. C., Seinfeld, J. H., Hämeri, K., Pirjola, L., Kulmala, M., Jennings, S. G., and Hoffmann, T.: Marine aerosol formation from biogenic iodine emissions, Nature, 417, 632–636, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00775, 2002.

Perdew, J. P. and Wang, Y.: Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy, Phys. Rev. B, 45, 13244–13249, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.45.13244, 1992.

Peterson, K. A., Figgen, D., Goll, E., Stoll, H., and Dolg, M.: Systematically convergent basis sets with relativistic pseudopotentials. II. Small-core pseudopotentials and correlation consistent basis sets for the post-d group 16–18 elements, J. Chem. Phys., 119, 11113–11123, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1622924, 2003.

Rörup, B., He, X.-C., Shen, J., Baalbaki, R., Dada, L., Sipilä, M., Kirkby, J., Kulmala, M., Amorim, A., Baccarini, A., Bell, D. M., Caudillo-Plath, L., Duplissy, J., Finkenzeller, H., Kürten, A., Lamkaddam, H., Lee, C. P., Makhmutov, V., Manninen, H. E., Marie, G., Marten, R., Mentler, B., Onnela, A., Philippov, M., Scholz, C. W., Simon, M., Stolzenburg, D., Tham, Y. J., Tomé, A., Wagner, A. C., Wang, M., Wang, D., Wang, Y., Weber, S. K., Zauner-Wieczorek, M., Baltensperger, U., Curtius, J., Donahue, N. M., El Haddad, I., Flagan, R. C., Hansel, A., Möhler, O., Petäjä, T., Volkamer, R., Worsnop, D., and Lehtipalo, K.: Temperature, humidity, and ionisation effect of iodine oxoacid nucleation, Environ. Sci. Atmospheres, 4, 531–546, https://doi.org/10.1039/D4EA00013G, 2024.

Roscoe, H. K., Jones, A. E., Brough, N., Weller, R., Saiz-Lopez, A., Mahajan, A. S., Schoenhardt, A., Burrows, J. P., and Fleming, Z. L.: Particles and iodine compounds in coastal Antarctica, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 120, 7144–7156, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023301, 2015.

Saiz-Lopez, A., Plane, J. M. C., Baker, A. R., Carpenter, L. J., Von Glasow, R., Gómez Martín, J. C., McFiggans, G., and Saunders, R. W.: Atmospheric Chemistry of Iodine, Chem. Rev., 112, 1773–1804, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr200029u, 2012.

Saiz-Lopez, A., Fernandez, R. P., Ordóñez, C., Kinnison, D. E., Gómez Martín, J. C., Lamarque, J.-F., and Tilmes, S.: Iodine chemistry in the troposphere and its effect on ozone, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 13119–13143, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-13119-2014, 2014.

Shen, J., Elm, J., Xie, H.-B., Chen, J., Niu, J., and Vehkamäki, H.: Structural Effects of Amines in Enhancing Methanesulfonic Acid-Driven New Particle Formation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 13498–13508, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c05358, 2020.

Sipilä, M., Sarnela, N., Jokinen, T., Henschel, H., Junninen, H., Kontkanen, J., Richters, S., Kangasluoma, J., Franchin, A., Peräkylä, O., Rissanen, M. P., Ehn, M., Vehkamäki, H., Kurten, T., Berndt, T., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D., Ceburnis, D., Kerminen, V.-M., Kulmala, M., and O'Dowd, C.: Molecular-scale evidence of aerosol particle formation via sequential addition of HIO3, Nature, 537, 532–534, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19314, 2016.

Tang, B., Bai, Q., Fang, Y.-G., Francisco, J. S., Zhu, C., and Fang, W.-H.: Mechanistic Insights into N2O5-Halide Ions Chemistry at the Air–Water Interface, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 146, 21742–21751, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c05850, 2024.

Van Der Spoel, D., Lindahl, E., Hess, B., Groenhof, G., Mark, A. E., and Berendsen, H. J. C.: GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free, J. Comput. Chem., 26, 1701–1718, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20291, 2005.

Wan, Z., Fang, Y., Liu, Z., Francisco, J. S., and Zhu, C.: Mechanistic Insights into the Reactive Uptake of Chlorine Nitrate at the Air–Water Interface, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 145, 944–952, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c09837, 2023.

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A., and Case, D. A.: Development and testing of a general amber force field, J. Comput. Chem., 25, 1157–1174, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20035, 2004.

Xia, D., Chen, J., Yu, H., Xie, H., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Xu, T., and Allen, D. T.: Formation Mechanisms of Iodine–Ammonia Clusters in Polluted Coastal Areas Unveiled by Thermodynamics and Kinetic Simulations, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 9235–9242, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b07476, 2020.

Yu, H., Ren, L., Huang, X., Xie, M., He, J., and Xiao, H.: Iodine speciation and size distribution in ambient aerosols at a coastal new particle formation hotspot in China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 4025–4039, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-4025-2019, 2019.

Zhang, R., Shen, J., Xie, H.-B., Chen, J., and Elm, J.: The role of organic acids in new particle formation from methanesulfonic acid and methylamine, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 2639–2650, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-2639-2022, 2022a.

Zhang, R., Xie, H.-B., Ma, F., Chen, J., Iyer, S., Simon, M., Heinritzi, M., Shen, J., Tham, Y. J., Kurtén, T., Worsnop, D. R., Kirkby, J., Curtius, J., Sipilä, M., Kulmala, M., and He, X.-C.: Critical Role of Iodous Acid in Neutral Iodine Oxoacid Nucleation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 14166–14177, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c04328, 2022b.

Zhang, R., Ma, F., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Elm, J., He, X.-C., and Xie, H.-B.: HIO3–HIO2-Driven Three-Component Nucleation: Screening Model and Cluster Formation Mechanism, Environ. Sci. Technol., 58, 649–659, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c06098, 2024a.

Zhang, Y., Li, D., He, X.-C., Nie, W., Deng, C., Cai, R., Liu, Y., Guo, Y., Liu, C., Li, Y., Chen, L., Li, Y., Hua, C., Liu, T., Wang, Z., Xie, J., Wang, L., Petäjä, T., Bianchi, F., Qi, X., Chi, X., Paasonen, P., Liu, Y., Yan, C., Jiang, J., Ding, A., and Kulmala, M.: Iodine oxoacids and their roles in sub-3 nm particle growth in polluted urban environments, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 1873–1893, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-1873-2024, 2024b.

Zhao, Y. and Truhlar, D. G.: The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals, Theor. Chem. Acc., 120, 215–241, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x, 2008.

Zhong, J., Kumar, M., Francisco, J. S., and Zeng, X. C.: Insight into Chemistry on Cloud/Aerosol Water Surfaces, Acc. Chem. Res., 51, 1229–1237, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00051, 2018.

Zu, H., Chu, B., Lu, Y., Liu, L., and Zhang, X.: Rapid iodine oxoacid nucleation enhanced by dimethylamine in broad marine regions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 5823–5835, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-5823-2024, 2024.