the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Direct observation of core-shell structure and water uptake of individual submicron urban aerosol particles

Ruiqi Man

Yishu Zhu

Zhijun Wu

Peter Aaron Alpert

Bingbing Wang

Jing Dou

Yan Zheng

Yanli Ge

Shiyi Chen

Xiangrui Kong

Markus Ammann

Determining the particle chemical morphology is crucial for unraveling reactive uptake in atmospheric multiphase and heterogeneous chemistry. However, it remains challenging due to the complexity and inhomogeneity of aerosol particles. Using a scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) coupled with near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) spectroscopy and an environmental cell, we imaged and quantified the chemical morphology and hygroscopic behavior of individual submicron urban aerosol particles. Results show that internally mixed particles composed of organic carbon and inorganic matter (OCIn) dominated the particle population (73.1±7.4 %). At 86 % relative humidity, 41.6 % of the particles took up water, with OCIn particles constituting 76.8 % of these hygroscopic particles. Most particles exhibited a core-shell structure under both dry and humid conditions, with an inorganic core and an organic shell. Our findings provide direct observational evidence of the core-shell structure and water uptake behavior of typical urban aerosols, which underscore the importance of incorporating the core-shell structure into models for predicting the reactive uptake coefficient of heterogeneous reactions.

- Article

(4045 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(5632 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Aerosols have significant impacts on visibility, climate, and human health (MccSormick and Ludwig, 1967; Noll et al., 1968; Chow et al., 2006; Rasool and Schneider, 1971). As particles in the atmosphere usually act as reaction vessels for various reactions, the physicochemical properties of aerosol particles play an important role in reactive uptake of gaseous molecules onto particles, mass transfer and gas-particle partitioning equilibrium, and transformation mechanisms of pollutants (Abbatt et al., 2012; Davidovits et al., 2011; George et al., 2015; George and Abbatt, 2010; Su et al., 2020; Ziemann and Atkinson, 2012). Therefore, quantitatively characterizing the aerosol physicochemical properties is vital to atmospheric multiphase and heterogeneous chemistry (Freedman, 2017; Li et al., 2016; Riemer et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2016).

The aerosol physicochemical properties, such as the particle size, chemical morphology (defined as the spatial distribution of various chemical components within a particle herein), mixing state, and hygroscopicity vary under different ambient conditions. These properties and their variations have a critical influence on reactive uptake, a key process in multiphase chemistry which is initiated by the collision of a gas-phase reactant with a condensed-phase surface (Davies and Wilson, 2018; Reynolds and Wilson, 2025). Organic coatings of particles with core-shell structures inhibit reactive uptake of dinitrogen pentoxide (N2O5) by particulate matter by means of affecting mass accommodation, the availability of water for hydrolysis, and mass transport (Wagner et al., 2013; Jahl et al., 2021; Jahn et al., 2021). Without considering the core-shell structure, the reactive uptake coefficient of N2O5 tends to be overestimated from several times to tens of times (Wagner et al., 2013). Therefore, investigating the particle chemical morphology is necessary for accurately quantifying the uptake coefficient and reducing uncertainty in heterogeneous reactions.

So far, extensive research has been conducted on the physicochemical properties of bulk aerosols by various techniques, such as the Humidified Tandem Differential Mobility Analyzer (H-TDMA), Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (AMS), and Soot Particle Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (SP-AMS) (Li et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2019; Riemer et al., 2019). However, the bulk analysis mostly obtains indirect information about the physicochemical properties of particle populations based on assumptions and estimations, which is difficult to directly observe the chemical morphology and mixing state of aerosol particles (Li et al., 2016). This knowledge gap hinders our understanding of the role of aerosol particles in reactive uptake and heterogeneous processes. As a comparison, individual particle analysis can provide direct observational evidence about the chemical morphology and mixing state at the microscopic scale, which is essential for exploring particle hygroscopic and optical properties (Krieger et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016; Pósfai and Buseck, 2010; Wu and Ro, 2020).

Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy combined with near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (STXM/NEXAFS) spectroscopy bases on synchrotron radiation technology. It is a robust technique for obtaining chemical morphology information of numerous individual particles with high spectral energy resolution and chemical specificity, as it can identify and distinguish various chemical composition at the single particle level within a particle population (Moffet et al., 2011; Shao et al., 2022). The soft X-ray energy range of STXM (100–2000 eV for STXM versus 50–200 keV for electron microscopy) makes it possible to quantify light elements (such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen) with little beam damage (Moffet et al., 2011). In addition, STXM doesn't require ultrahigh vacuum conditions (Moffet et al., 2011). In short, STXM/NEXAFS spectroscopy provides an enhanced chemical sensitivity for obtaining specific organic chemical bonds, functional groups, and speciation information, which has enormous potential in exploring ambient samples under atmospheric relevant conditions, especially submicron-sized particles.

Compared with other STXM endstations which generally analyze samples under vacuum conditions (Alpert et al., 2022; Bondy et al., 2018; Fraund et al., 2020; Knopf et al., 2023; Lata et al., 2021; Moffet et al., 2010a, b, 2013, 2016; Tomlin et al., 2022), several STXM instruments are equipped with an in-situ temperature and relative humidity (RH) control environmental cell, allowing for investigating hygroscopicity and water uptake behavior of laboratory-generated particles (Ghorai and Tivanski, 2010; O'brien et al., 2015; Piens et al., 2016; Zelenay et al., 2011a, b). However, only a limited amount of research focusing on hygroscopic behavior of ambient particles has been reported so far, and these particles were collected in a rural environment (Piens et al., 2016) or the forest (Mikhailov et al., 2015; Pöhlker et al., 2014). A study on water uptake of urban aerosol particles using STXM and corresponding knowledge for their chemical morphology under humid conditions is currently lacking.

In recent years, the air quality in China has improved notably due to the implementation of a series of strict pollution mitigation measures. These improvements are attributed to decreasing primary emissions, while the contributions of secondary species to particle mass have become more significant (Lei et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019). To elucidate the causes and mechanisms of pollution episodes in China, numerous research has been carried out on the pollution characteristics (Gao et al., 2015, 2018; Guo et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2013) and physicochemical properties (Gao and Anderson, 2001; Li et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2019; Song et al., 2022) of ambient aerosols. However, there is still a lack of study on direct observation of the chemical morphology and hygroscopic behavior of secondary urban aerosols at the single particle level. This knowledge gap hinders our understanding of the role of secondary aerosols as reaction vessels in heterogeneous reactions.

In this study, we investigated the chemical morphology of ambient individual submicron aerosol particles using STXM/NEXAFS spectroscopy. The ambient samples were collected at an urban site in North China Plain, Beijing during a pollution episode. We also explored the chemical morphology and water uptake behavior of individual particles at high humidity (RH=86 %) using an environmental cell. This work aims to improve our comprehension of the physicochemical properties of particles in typical urban pollution atmospheres, aiding in clarifying their atmospheric heterogeneous processes and multiphase chemistry.

2.1 Sampling and instruments

To study the physicochemical properties of ambient particles, samples were collected during a pollution episode at the Peking University Urban Atmosphere Environment Monitoring Station (PKUERS, 39°59′21′′ N, 116°18′25′′ E) in Beijing, China. More details about the measurement site can be found in our previous studies (Tang et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2007).

The individual particle sample was collected using a four-stage cascade impactor with a Leland Legacy personal sample pump (Sioutas, SKC, Inc., USA) at a flow rate of 9 L min−1. The sampling started at 05:04 PM on 1 October 2019 and lasted for 5 min. The sampling substrate was a copper grid (Lacey Carbon 200 mesh, Ted Pella, Inc., USA) suitable for its X-ray transparency. Particles collected onto the last stage with the 50 % cut-point aerodynamic diameter of 250 nm were used for STXM analysis. The sample was placed into a sample box sealed with a bag filled with nitrogen, and it was stored in a freezer at a temperature of −18 °C until analysis. Previous results indicate that the chemical composition of organic aerosols (especially secondary organic aerosols, SOA) and the mass concentrations of black carbon (BC) both remained stable for several weeks under low-temperature storage conditions (−20 and −80 °C for organic aerosols, and 2, 4, and 5 °C for BC); while significant changes occurred over time when samples were stored at room temperature even just for a few days (Mori et al., 2016, 2019; Resch et al., 2023; Ueda et al., 2025; Wendl et al., 2014).

Other parameters were measured from 28 September–7 October 2019. The non-refractory chemical composition of submicron particles (NR-PM1) was obtained by a Long Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (LTOF-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc., USA) (Zheng et al., 2020, 2023). Calibrations of ionization efficiency (IE) and relative IE followed the standard procedures described in previous studies (Canagaratna et al., 2007; Fröhlich et al., 2013). The reference temperature and pressure conditions of mass concentrations reported herein were 293.7 and 101.82 KPa. We applied composition-dependent collection efficiency (CDCE) values (0.50±0.01, mean ± standard deviation) that were calculated by the methods introduced by Middlebrook et al. (2012) to the AMS data. The mass concentration of fine particles (PM2.5) was measured by a TEOM analyzer (TH-2000Z1, Wuhan Tianhong Environmental Protection Industry Co., Ltd., China). Meteorological parameters including temperature (T), RH, wind speed, and wind direction were monitored by an integrated 5-parameter Weather Station (MSO, Met One Instruments, Inc., USA).

2.2 STXM/NEXAFS analysis

In order to gain the chemical morphology, mixing state, and component information of individual particles, STXM/NEXAFS spectroscopy measurements were carried out at the PolLux beamline (X07DA) of the Swiss Light Source (SLS) at Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) (Raabe et al., 2008). In brief, X-rays illuminated a Fresnel zone plate focusing the beam to a pixel of 35×35 nm2. The zone plate has a central stop that acts together with another optic known as an order sorting aperture to eliminate unfocused and higher-order light, ensuring only first-order focused light is transmitted to the sample. Then, X-rays transmitted through the sample were detected. The absorbance of each pixel is characterized by optical density (OD) based on the Beer–Lambert's law as follows,

where I and I0 are the intensity of photons transmitted through a sample region and a sample-free region, respectively. Further details including the uncertainty estimation of OD are described in the Supplement.

STXM/NEXAFS spectroscopy scans X-ray energies over particles with high spectral energy resolution. When inner shell electrons of atoms absorb X-ray photons, they can transition into unoccupied valence orbitals, resulting in an absorption peak that is used to identify specific bonding characteristics. The amount of absorption depends on the photon energy (E), elemental composition, as well as sample thickness and density (Moffet et al., 2011). We employed two measurement strategies to optimize photon flux to the particles, achieving the best signal-to-noise ratio while minimizing the scan time. The first strategy was a high energy-resolution mode with an X-ray energy resolution ΔE=0.2 eV and a coarse pixel size of around 100×100 nm2 to measure absorption at small energy steps. The energy resolution is defined as being able to distinguish between two absorption peaks separated by ΔE at the full width at half maximum OD. In this mode, carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and oxygen (O) K-edge spectra of individual particles were measured. The energy offset of C and O spectra were +0.4 and +1.2 eV respectively, according to the energy calibration procedures using polystyrene spheres and gas-phase carbon dioxide (CO2). The energy offset of N at the K-edge was not calibrated, however, the obtained spectra of ambient particles appeared identical to ammonium salts in literature (Ekimova et al., 2017; Latham et al., 2017). Due to the presence of ammonium, which was confirmed in particles using AMS, we applied a calibration factor of +0.1 eV for the N K-edge to match our observed main peak to that of ammonium at 405.7 eV. Optical density detected over the same spot at different photon energies at the carbon and nitrogen K-edges was displayed in Fig. S1 in the Supplement, and less beam damage during the experiment was confirmed.

The second strategy is a high spatial-resolution mode with a pixel size of 35×35 nm2 and ΔE=0.6 eV, where imaged at four specific energies for the C K-edge, namely, 278.0, 285.4, 288.6, and 320.0 eV. Automated analysis followed the methodology of Moffet et al. (2010a, 2016). In brief, absorption at 278.0 eV (OD278.0 eV) is regarded as the pre-edge of carbon, which is mainly due to off-resonance absorption by inorganic elements other than carbon. Absorption at 285.4 eV (OD285.4 eV) is due to the characteristic transition of sp2 hybridized carbon (i.e., doubly bonded carbon). Since this peak is abundant for elemental carbon (EC), it can be used to discern soot, because EC is a type of components of soot (Penner and Novakov, 1996). Absorption at 288.5 eV (OD288.5 eV) comes from carboxylic carbonyl groups, which are common in organic aerosols in atmospheres. Therefore, organic carbon (OC) is identified by this energy. Absorption of the post-edge at 320.0 eV (OD320.0 eV) is contributed by carbonaceous and non-carbonaceous atoms (Moffet et al., 2010a).

Based on absorption at these four typical energies, we obtain three images by further processing. The difference between OD at the post-edge and OD at the pre-edge (OD320.0 eV−OD278.0 eV) indicates total carbon. The ratio of OD at the pre-edge to OD at the post-edge () indicates the relative absorption contribution of inorganic matter (In). Compared with the absorbance contribution of doubly bonded carbon to total carbon (%sp2) in the highly oriented polycrystalline graphite (HOPG, assuming that %sp2=100 %) at 285.4 eV, the spatial distribution of EC/soot in samples can be identified by the procedure of Hopkins et al. (2007). It is assumed that total carbon consists of OC and EC. The thresholds of these images follow the criteria mentioned in Moffet et al. (2010a) and Moffet et al. (2016). These three images described above were then overlaid to create a chemical map of individual particles.

2.3 Criterion of particle water uptake based on the total oxygen absorbance

To determine whether particles took up water, a criterion was established on the basis of the total oxygen absorbance determined at the energy of 525.0 eV (the pre-edge of oxygen) and 550.0 eV (the post-edge of oxygen). Based on the same principle as the total carbon calculation, the difference between OD at the post-edge and pre-edge of oxygen represents the total oxygen absorbance. Due to the fact that each particle is composed of some pixels, the total oxygen absorbance (ΔOD) of an individual particle under dry and humid conditions is calculated as follows,

where m and n are numbers of pixels that make up an individual particle under dry and humid conditions, i and j are a certain pixel within an individual particle under dry and humid conditions, post and pre respectively represent the energy at the post-edge (550.0 eV) and that at the pre-edge (525.0 eV) of oxygen. If a particle takes up water, the amount of oxygen atoms within this particle will increase, leading to an amplification in ΔOD. Water uptake may increase particle height and absorption. On the other hand, it possibly causes a particle to spread out, which may reduce particle height and thus absorption. Although a thinner particle that contains more water may result in less absorption at some specific pixels, ΔODhumid will be larger than ΔODdry due to the fact that more pixels are summed, i.e., n>m. Therefore, comparing the results of Eqs. (2) and (3) will quantify the total oxygen absorbance of a particle under dry and humid conditions, and determine particle water uptake. Specifically, if ΔODhumid>ΔODdry, then we assume that a particle has taken up water.

2.4 A novel in-situ environmental cell

To explore the chemical morphology and hygroscopicity of the particles under humid conditions, we adjusted the RH of an in-situ environmental cell with sample placed in it. The environmental cell can also be used for trace gas reactive uptake and photochemical reactions with laboratory-generated particles (Alpert et al., 2019, 2021). The environmental cell used in this study consists of a removable sample clip that hosts a sealed silicon nitride (SiNit) window and a main body that contains gas supply lines and temperature control. Together, they are mounted in the STXM vacuum chamber. A SiNit window at the back side of the main body is also sealed and ensures X-ray transparency passing through the whole environmental cell assembly. Descriptions of the connections for the gas supply, heating and cooling devices, and temperature measurement can be found in previous studies (Huthwelker et al., 2010; Zelenay et al., 2011a). The detailed methods of collecting the ambient particles by the impactor and measuring them in the environmental cell were shown in the Supplement.

We performed humidity calibration experiments to make sure sufficient heat transfer and a homogeneous water vapor field across the samples. It is important due to the fact that the only way for samples to gain or lose heat and water was through air contact. To study the accuracy of RH in the environmental cell, water uptake and deliquescence of a sodium chloride (NaCl) standard sample was observed. The deliquescence relative humidity (DRH) of pure NaCl crystals obtained from literature and thermodynamic models is around 75 %–76 % at room temperature (Eom et al., 2014; Martin, 2001; Peng et al., 2022). The images of the NaCl sample displayed in Fig. S2 illustrate the morphological changes as RH increased. As shown in Fig. S2, particle morphologies in panels (A–C) remained essentially identical before RH reached the DRH of NaCl, although the focus position slightly varied in different panels. When RH was 75.6 % (Fig. S2D), particles completely deliquesced and some coalesced. The uncertainty of RH in the environmental cell in this study was determined conservatively to be ±2 %, in agreement with previous results (Huthwelker et al., 2010). Information about the oxygen K-edge spectra of the NaCl sample at high RH can be found in Fig. S3.

3.1 Pollution characteristics during the sampling period

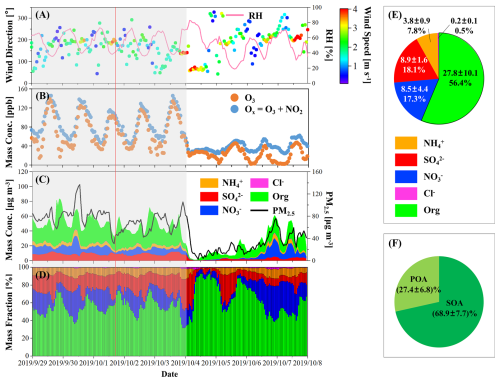

Time series of meteorological parameters, mass concentrations of gaseous pollutants, PM2.5, and NR-PM1 are shown in Fig. 1. During the pollution episode from 29 September–3 October 2019, the stagnant weather condition with low wind speed led to pollution accumulation. The air became clean due to the appearance of a strong north wind on 4 October (Fig. 1A). The sampling time of the individual particle sample was 05:04 P.M. on 1 October (see the red line in Fig. 1) with an ozone (O3) concentration of 97.1 ppb. The average mass fractions of chemical composition of NR-PM1 during the sampling period of individual particles could be found in Fig. S4. During this period, the low mass fraction of volatile inorganic species such as nitrate made it suitable for measurements using offline techniques, such as STXM, because the loss of volatile species during storage and measurement processes was minimal.

Figure 1Time series of (A) wind direction, wind speed, and relative humidity (RH), (B) mass concentrations of ozone (O3) and Ox (O3+nitrogen dioxide, NO2), (C) mass concentrations of fine particles (PM2.5) and non-refractory submicron particles (NR-PM1), and (D) mass fractions of chemical composition of NR-PM1 are shown. The gray area represents the pollution episode lasting from 29 September–3 October. The red line indicates the sampling time for the individual particle sample. (E) Pie chart showing the average mass fractions of chemical composition of NR-PM1 during the pollution period. The number in the first row of each part is the average mass concentration and standard deviation (SD) with a unit of µg m−3. The number in the second row is the average mass fraction. (F) Pie chart showing the average mass contributions of primary organic aerosol (POA, light green) and secondary organic aerosol (SOA, dark green) to the total organic. Average mass fraction and SD are marked in the pie chart.

During the pollution episode, the maximum daily 8 h average of ozone (MDA8-O3) was 110.3±10.1 ppb (i.e., ). The concentration of Ox [] was 88.6±29.4 ppb (Fig. 1B), reflecting a high atmospheric oxidation capacity that drives secondary transformations of gaseous pollutants (Dou et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2022). The average PM2.5 was (Fig. 1C). As shown in Fig. 1D and E, the average mass concentration of secondary inorganic aerosol (SIA) in NR-PM1 was , with sulfate and nitrate contributing almost equally to particle mass (i.e., 18.1 % and 17.3 % respectively). Organic matter in NR-PM1 had an average mass fraction of 56.4 % (Fig. 1E). The mass concentrations of primary organic aerosol (POA) and SOA were estimated based on the positive matrix factorization (PMF) analysis (Ulbrich et al., 2009). As shown in Fig. 1F, SOA dominated organic matter, contributing an average of 68.9 %. Overall, this pollution episode was led by secondary oxidation processes and featured by high contributions of secondary particulate species.

3.2 Chemical maps of individual particles

Chemical maps of individual particles under dry conditions are displayed in Fig. 2. Different images denote particles located in different regions of interest (ROI, 12 in total) of the sampling substrate. 197 individual particles were investigated in total. The detailed images of total carbon, inorganic, and doubly bonded carbon maps are available in Figs. S5–S7. Most submicron particles on the substrate were round or nearly round, while supermicron particles predominantly exhibited irregular shapes. The circular equivalent diameter of individual particles was calculated, with the methods detailed in the Supplement. The normalized size distribution of overall particles followed a normal distribution, with a mean diameter ± standard deviation (SD) being 0.83±0.30 µm (Fig. S8A). A significant proportion of the particles were within the 0.4–1.2 µm size range.

As displayed in Fig. 2, chemical maps of individual particles showed that they were dominated by inorganic substances (colored in cyan), which were likely sulfate that was frequently observed by AMS (Fig. 1C). Approximately one quarter (24.9 %) of the particles contained EC/soot (colored in red). Notably, around 82 % of these soot-containing particles had soot located at particle edges. One of the possible reasons is that inorganic species (such as crystals) pushed soot away from the center of the particles during their efflorescence (Moffet et al., 2016). While, it should be noted that particle deformation may occur during the particle collection process due to the high particle impaction velocity of the impactor (O'Brien et al., 2014). Therefore, the distribution of chemical components within individual particles displayed in the images may differ from that of aerosol particles in ambient atmospheres. Additionally, several particles contained multiple soot components, which was also observed before (Moffet et al., 2016).

Figure 2Chemical maps of individual particles in 12 regions of interest (ROI) of sampling substrate under dry conditions on the basis of pixels. Green, cyan, and red color represent dominant components of organic carbon (OC), inorganic matter (In), and elemental carbon (EC), respectively. The scale bar in the upper left image represents 2 µm and applies to all the images.

Typically, inorganic components and/or soot were encased in organic matter, forming a core-shell structure characterized by an inorganic-dominated core and an organic-dominated shell. Figure 2 illustrates that most organic–inorganic internally mixed particles exhibited thin coatings, likely from fresh emissions. Conversely, a few particles have thick coatings, which is indicative of aging processes in a highly active photochemical environment. Previous studies suggest that most of the soot-containing particles with thin coatings would have rather smaller absorption enhancement compared with those with thick coatings (Bond et al., 2006; Moffet et al., 2016).

The observed core-shell morphology could also result from liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS), influenced by fluctuating ambient RH (Fig. 1A) and determined by the oxygen-to-carbon (O : C) ratio of the organic fraction (Freedman, 2020; Li et al., 2021; You et al., 2012, 2014; Freedman, 2017). To test this hypothesis, the O : C ratio of the individual particles composed of pure organic composition was estimated as 0.53±0.15 based on the STXM data. The estimation methods were displayed in the Supplement. This falls within the threshold range for LLPS occurrence in ammonium sulfate – organic mixing particles () (You et al., 2013). For comparison, the value of the O : C ratio by AMS during the individual particle collection period is also calculated (0.60±0.01), and the data set was displayed in the Supplement. The difference between the O : C ratio results by STXM and LToF-AMS may be due to the reasons as follows: (1) STXM measures individual particles, while AMS targets bulk aerosols; (2) Particles collected onto the last stage using a four-stage cascade impactor with the 50 % cut-point aerodynamic diameter of 250 nm were used for STXM analysis, while AMS measured the non-refractory chemical composition of submicron particles.

Statistically, the particles were categorized into four types based on their mixing state, including pure organic (OC), organic internally mixed with soot (OCEC), organic internally mixed with inorganic (OCIn), and organic internally mixed with inorganic and soot (OCInEC). OCIn particles were the most abundant type in the examined particle population (73.1±7.4 %), followed by OCInEC (20.8±6.7 %) and OCEC (4.1±3.3 %), indicating a highly internally mixed particle population. Pure organic particles only accounted for 2.0±2.3 %. The calculation of the margin of error of the mixing state proportions can be found in the Supplement. The mean diameters of OCEC, OCIn, and OCInEC particles were 0.66, 0.79, and 1.02 µm, respectively (Fig. S9). This suggests that the internally mixed particles containing three species families tend to be larger than those composed of two species families.

3.3 The effects of particle water uptake on chemical maps

Chemical maps of individual particles under humid conditions (RH=86 %) measured in the environmental cell were displayed in Fig. 3, and these ROI are identical and matched one by one to those in Fig. 2. For comparison, the one-to-one particle chemical maps of the same region of interest under both dry and humid conditions can be found in Fig. S10. It was observed that many particles tended to be more rounded due to water uptake at high RH, especially for particles with diameters in the supermicron range (e.g., particles in (ii), (vi), (xi), and (xii) in Fig. 3). If particles take up significant amounts of water and are homogeneously mixed, they would appear as dominated by inorganic (colored in cyan) due to absorption of a large amount of water at the carbon pre-edge. In contrast, most particles remained inhomogeneous and exhibited a core-shell structure under humid conditions. A possible reason is that the settled RH may not reach the mixing relative humidity (MRH) of particles, which is defined as a threshold where different phases in an aqueous particle mix into one homogeneous phase. This MRH usually varies from 84 % to over 90 % (Li et al., 2021; You et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2022).

Figure 3Chemical maps of individual particles in 12 ROI of sampling substrate under humid conditions (RH=86 %) measured in an in-situ environmental cell. Green, cyan, and red color represent dominant components of OC, In, and EC, respectively. The scale bar in the upper left image represents 2 µm and applied to all the images.

Additionally, around 87 % of soot was located at the edge of the humidified particles, with no obvious location change of soot observed in most particles. A previous study witnessed the redistribution of soot within phase-separated particles only after the phase mixing process occurred (Zhang et al., 2022), which is consistent with the phenomenon observed in our study.

Comparing size distributions of particle populations under dry (Fig. S8A) and humid conditions (Fig. S8B) reveals that they exhibited similar distribution characteristics. The mean diameter of overall particles at high RH was 0.86±0.33 µm, compared with 0.83±0.30 µm under dry conditions. This indicates that the overall size distribution of the humidified particles shifted a little towards larger particles due to water uptake. Specifically, approximately 56.3 % of the particles showed an average increase of 14.9 % in diameter, while the remaining exhibited an average decrease of 8.2 %. Pöhlker et al. (2014) also observed this abnormal phenomenon where some particles decreased in size with increasing RH. They suggested that it could be attributed to the decreasing viscosity and increasing surface tension due to particle water uptake at high RH. This led to larger contact angles between the collected particles and the substrate, causing the particles to “bead up” and therefore reducing their cross-section areas in the view (Pöhlker et al., 2014). In addition, one should note that a small number of particles at the edge of the ROI did not entirely enter the field of view due to the limited observation range, which may slightly affect the quantification of their size.

According to the criterion for water uptake by individual particles based on the total oxygen absorbance described in the Sect. 2.3, 41.6 % of the particles took up water. As shown in Fig. S11A, OCIn particles were the dominant mixing state type taking up water (76.8 %), followed by OCInEC (17.1 %). There were also several OCEC (2.4 %) and OC (3.7 %) particles displayed water uptake. Different particle mixing state types exhibited distinct patterns of hygroscopic behavior. For instance, 43.8 % of OCIn particles took up water, while 34.1 % of OCInEC particles performed the same. This difference may be attributed to varying hygroscopicity of different components. For example, the single hygroscopic parameter (κ) of ammonium nitrate, ammonium sulfate, ammonium hydrogen sulfate, POA, and SOA is 0.58, 0.48, 0.56, 0, and 0.1, respectively (Wu et al., 2016). Based on the AMS data, κ of bulk aerosols during the sampling period (0.25±0.01) was calculated according to κ-Köhler theory (Stokes and Robinson, 1966; Petters and Kreidenweis, 2007), indicating a relatively low hygroscopic capacity of NR-PM1 during sampling, which could explain why only less than half of the particles exhibited water uptake at such high humidity conditions. In addition, the average diameter of particles taking up water increased from 0.82±0.33 µm to 0.91±0.36 µm. The relative frequency distribution and the size-resolved fraction of particles taking up water can be found in Fig. S11B.

3.4 Chemical composition of ambient submicron particles

NEXAFS spectra with high energy resolution were measured at the C (278–320 eV), N (395–430 eV), and O (525–550 eV) K-edges. As shown in Fig. 4A, three notable absorption peaks at the C K-edge were observed at 285.4, 286.7, and 288.6 eV. According to previous literature (Warwick et al., 1998; Moffet et al., 2010a), the peak at 285.4 eV refers to the characteristic transition of sp2 hybridized carbon (). The peak at 286.7 eV may result from the transition of ketonic carbonyl (), representing ketone and ketone-like compounds. The peak appearing at 288.6 eV represents the characteristic transition of carboxylic carbonyl functional groups (), which refers to organic matter and is generally dominant in the outer shell of particles (Moffet et al., 2016; Prather et al., 2013). One should note that there could be extra components in both core and shell in a phase-separated particle with an inorganic-rich core and an organic-rich shell, for example, organic in core or inorganic in shell (Gaikwad et al., 2022). Therefore, the 288.6 eV peak may also be observed in a particle core with relatively low peak intensity. In addition, two other peaks at 296.8 and 299.6 eV were present (see spectra (d) and (e) in Fig. 4A), corresponding to the L2- and L3-edges of potassium (Moffet et al., 2010a). In our sample, potassium may come from biomass burning processes based on a previous study (Wu et al., 2017).

Nitrogen K-edge spectra in Fig. 4B illustrate that ammonium salts were the main nitrogen species in the sample. We observed a broad main peak centered at 405.7 eV, which is the feature of ammonium (Ekimova et al., 2017). A smaller peak was observed at 401.0 eV, which is absorption due to nitrogen gas (N2) either trapped in the inorganic crystal or formed under X-ray exposure (Latham et al., 2017). Absorption of nitrate () and nitrite () commonly have narrow peaks at 405.1 and 401.7 eV (Smith et al., 2015), respectively, which were not apparent in our spectra. This is likely because particulate nitrite is below the detection limit, or its peak is masked by the pronounced absorption of ammonium (). The solid ammonium nitrate and sodium nitrate salts could exhibit a peak at around 415.0 eV (Smith et al., 2015). However, this was not observed in Fig. 4B. Organic compounds containing nitrogen, such as amino acids, N-heterocyclics, and nitroaromatic compounds, can be abundant in urban aerosol particles due to combustion sources (Yu et al., 2024). They have a large variety of possible peak positions, heights, and widths (Leinweber et al., 2007), making the identification of these compounds difficult. Although a positive identification of specific organic nitrides cannot be made, we note that amino acids and 5- or 6-ring heterocycles commonly have narrow peaks at around 401 eV and broad peaks at 405 eV (Leinweber et al., 2007). We expect that organic nitrides did contribute to the observed N K-edge spectra, although a targeted study on molecular identification would be necessary to establish further certainty.

Figure 4NEXAFS spectra for individual particles at (A) carbon (C), (B) nitrogen (N), and (C) oxygen (O) K-edges. In panel (A), peaks were observed at 285.4, 286.7, and 288.6 eV, and two typical peaks appeared at around 296.8 and 299.6 eV in spectra (d, e). In panel (B), a main peak appeared at 405.7 eV, and a smaller peak appeared at 410.0 eV. In panel (C), a main peak appeared at 536.9 eV, and a smaller peak was at 532.5 eV. Each small case letter of a spectrum stands for the average result of all the pixels within an individual particle. The same letter in different panels doesn't refer to a same particle.

Oxygen K-edge spectra in Fig. 4C exhibited a large peak at 536.9 eV, which is a representative characteristic of sulfate-rich particles (Colberg et al., 2004; Slowik et al., 2011; Mikhailov et al., 2015; Pöhlker et al., 2014), consistent with the result of AMS. A smaller peak was observed at 532.5 eV, confirming the presence of ketone, aldehyde, or carboxyl functionalities (Moffet et al.,2011), which aligns with the results from C K-edge spectra. These compositions tend to take up water under humid conditions.

Particles in the atmosphere usually act as reaction vessels for heterogeneous reactive uptake of gaseous molecules, and heterogeneous processes play an important part in gas-particle partitioning and secondary aerosol formation (Abbatt et al., 2012; Davidovits et al., 2011; Kolb et al., 2010). However, determining the particle physicochemical properties is crucial but challenging due to the complexity and inhomogeneity of aerosol particles (Barbaray et al., 1979; Zong et al., 2022). So far, there is a lack of study on direct observation of the physicochemical properties of urban aerosols at the single particle level under different conditions, which hinders our understanding of the role of urban aerosols in multiphase and heterogeneous chemistry.

In this study, we used STXM/NEXAFS spectroscopy combined with an environmental cell to image and quantify the chemical morphology and water uptake behavior of individual submicron particles collected in an urban pollution atmosphere. Results show that most organic compounds were internally mixed with inorganic and/or soot, generally presenting a core-shell structure with an inorganic core and an organic shell. Internally mixed particles composed of organic carbon and inorganic matter dominated the particle population by 73.1±7.4 %. At 86 %RH, 41.6 % of the particles took up water, with OCIn particles making up 76.8 % of these hygroscopic particles. The relatively low hygroscopicity of bulk aerosols during the sampling period () helps to explain the reason why only less than half of the particles took up water. Besides, the majority of particles still showed a heterogeneous core-shell morphology under humid conditions.

This study directly displays the dominant chemical morphology (i.e., core-shell structure) and hygroscopic behavior of individual submicron urban aerosol particles at the microscale. The uptake coefficient onto aerosol particles with different phase states exhibit different patterns as the relative humidity changes (Wang and Lu, 2016). For aqueous particles, the uptake coefficient is closely related to RH (Wang and Lu, 2016). Specifically, when RH is lower than the DRH of the inorganic component, the uptake coefficient increased with the increasing RH. When RH is higher than DRH, the uptake coefficient remains constant. For solid particles, the relationship between the uptake coefficient and RH usually depends on particle species (Wang and Lu, 2016). Results highlight the importance of taking the core-shell structure into consideration for estimating the uptake coefficient and investigating heterogeneous reactions at different humidity, which can improve our comprehension of atmospheric processes of secondary aerosols in typical urban pollution atmospheres.

Moreover, previous studies found that the reactive uptake coefficients of N2O5 on aqueous sulfuric acid solutions coated with different kinds of organics vary (Cosman and Bertram, 2008; Cosman et al., 2008). The reactive uptake coefficient decreased dramatically for straight-chain surfactants (1-hexadecanol, 1-octadecanol, and stearic acid) by a factor of 17–61 depending on the surfactant type. While, the presence of branched surfactant phytanic acid didn't show obvious effect on the reactive uptake coefficient compared to the uncoated solution. These results underline that the significant impact of organic species on the reactive uptake coefficient. Therefore, on the basis of the high spectral energy resolution of STXM/NEXAFS, it is instrumental to conduct research on the effect of organic molecules and functional groups on heterogeneous reactions in future studies.

The data presented in this article can be accessed through the corresponding author, Zhijun Wu, via e-mail (zhijunwu@pku.edu.cn).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-349-2026-supplement.

YZ, PAA, BW, and JD measured the individual particle sample by STXM/NEXAFS. YZ, ZW, YZ, YG, QC, and SC carried out the field observation and obtained data. RM and PAA processed and analyzed data. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the writing of this paper. RM prepared the manuscript. ZW, PAA, JC, XK, MA, and MH further modified and improved the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We gratefully acknowledge the Swiss Light Source (SLS) for providing a platform for sample measurements. We also thank Benjamin Watts for helping us dealing with technical problems about STXM/NEXAFS.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22221004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 41775133), and the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (grant no. TMPFP2_209830).

This paper was edited by Sergey A. Nizkorodov and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abbatt, J. P. D., Lee, A. K. Y., and Thornton, J. A.: Quantifying trace gas uptake to tropospheric aerosol: recent advances and remaining challenges, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6555–6581, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cs35052a, 2012.

Alpert, P. A., Arroyo, P. C., Dou, J., Krieger, U. K., Steimer, S. S., Förster, J.-D., Ditas, F., Pöhlker, C., Rossignol, S., Passananti, M., Perrier, S., George, C., Shiraiwa, M., Berkemeier, T., Watts, B., and Ammann, M.: Visualizing reaction and diffusion in xanthan gum aerosol particles exposed to ozone, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 21, 20613–20627, https://doi.org/10.1039/c9cp03731d, 2019.

Alpert, P. A., Dou, J., Arroyo, P. C., Schneider, F., Xto, J., Luo, B. P., Peter, T., Huthwelker, T., Borca, C. N., Henzler, K. D., Schaefer, T., Herrmann, H., Raabe, J., Watts, B., Krieger, U. K., and Ammann, M.: Photolytic radical persistence due to anoxia in viscous aerosol particles, Nat. Commun., 12, 1769, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21913-x, 2021.

Alpert, P. A., Kilthau, W. P., O'Brien, R. E., Moffet, R. C., Gilles, M. K., Wang, B. B., Laskin, A., Aller, J. Y., and Knopf, D. A.: Ice-nucleating agents in sea spray aerosol identified and quantified with a holistic multimodal freezing model, Sci. Adv., 8, eabq6842, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq6842, 2022.

Barbaray, B., Contour, J. P., Mouvier, G., Barde, R., Maffiolo, G., and Millancourt, B.: Chemical heterogeneity of aerosol samples as revealed by atomic absorption and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Environ. Sci. Technol., 13, 1530–1532, https://doi.org/10.1021/es60160a008, 1979.

Bond, T. C., Habib, G., and Bergstrom, R. W.: Limitations in the enhancement of visible light absorption due to mixing state, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 111, D20211, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007315, 2006.

Bondy, A. L., Bonanno, D., Moffet, R. C., Wang, B., Laskin, A., and Ault, A. P.: The diverse chemical mixing state of aerosol particles in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 12595–12612, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-12595-2018, 2018.

Canagaratna, M. R., Jayne, J. T., Jimenez, J. L., Allan, J. D., Alfarra, M. R., Zhang, Q., Onasch, T. B., Drewnick, F., Coe, H., Middlebrook, A., Delia, A., Williams, L. R., Trimborn, A. M., Northway, M. J., DeCarlo, P. F., Kolb, C. E., Davidovits, P., and Worsnop, D. R.: Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer, Mass Spectrom. Rev., 26, 185–222, https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.20115, 2007.

Chow, J. C., Watson, J. G., Mauderly, J. L., Costa, D. L., Wyzga, R. E., Vedal, S., Hidy, G. M., Altshuler, S. L., Marrack, D., Heuss, J. M., Wolff, G. T., Pope, C. A., and Dockery, D. W.: Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect, J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc., 56, 1368–1380, https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2006.10464545, 2006.

Colberg, C. A., Krieger, U. K., and Peter, T.: Morphological investigations of single levitated aerosol particles during deliquescence/efflorescence experiments, J. Phys. Chem. A., 108, 2700–2709, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp037628r, 2004.

Cosman, L. M. and Bertram, A. K.: Reactive Uptake of N2O5 on Aqueous H2SO4 Solutions Coated with 1-Component and 2-Component Monolayers, J. Phys. Chem. A., 112, 4625–4635, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp8005469, 2008.

Cosman, L. M., Knopf, D. A., and Bertram, A. K.: N2O5 Reactive Uptake on Aqueous Sulfuric Acid Solutions Coated with Branched and Straight-Chain Insoluble Organic Surfactants, J. Phys. Chem. A., 112, 2386–2396, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp710685r, 2008.

Davidovits, P., Kolb, C. E., Williams, L. R., Jayne, J. T., and Worsnop, D. R.: Update 1 of: Mass Accommodation and Chemical Reactions at Gas-Liquid Interfaces, Chem. Rev., 111, PR76–PR109, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr100360b, 2011.

Davies, J. F. and Wilson, K. R.: Chapter 13 - Heterogeneous Reactions in Aerosol, Physical Chemistry of Gas-Liquid Interfaces, edited by: Faust, J. A. and House, J. E., Elsevier, the Netherlands, 403–433, ISBN: 9780128136416, 2018.

Dou, X. D., Yu, S. C., Li, J. L., Sun, Y. H., Song, Z., Yao, N. N., and Li, P. F.: The WRF-CMAQ Simulation of a Complex Pollution Episode with High-Level O3 and PM2.5 over the North China Plain: Pollution Characteristics and Causes, Atmosphere, 15, 198, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15020198, 2024.

Ekimova, M., Quevedo, W., Szyc, L., Iannuzzi, M., Wernet, P., Odelius, M., and Nibbering, E. T. J.: Aqueous Solvation of Ammonia and Ammonium: Probing Hydrogen Bond Motifs with FT-IR and Soft X-ray Spectroscopy, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 139, 12773–12783, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b07207, 2017.

Eom, H. J., Gupta, D., Li, X., Jung, H. J., Kim, H., and Ro, C. U.: Influence of collecting substrates on the characterization of hygroscopic properties of inorganic aerosol particles, Anal. Chem., 86, 2648–2656, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac4042075, 2014.

Fraund, M., Bonanno, D. J., China, S., Pham, D. Q., Veghte, D., Weis, J., Kulkarni, G., Teske, K., Gilles, M. K., Laskin, A., and Moffet, R. C.: Optical properties and composition of viscous organic particles found in the Southern Great Plains, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 11593–11606, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-11593-2020, 2020.

Freedman, M. A.: Phase separation in organic aerosol, Chem. Soc. Rev., 46, 7694–7705, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cs00783j, 2017.

Freedman, M. A.: Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation in Supermicrometer and Submicrometer Aerosol Particles, Acc. Chem. Res., 53, 1102–1110, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00093, 2020.

Fröhlich, R., Cubison, M. J., Slowik, J. G., Bukowiecki, N., Prévôt, A. S. H., Baltensperger, U., Schneider, J., Kimmel, J. R., Gonin, M., Rohner, U., Worsnop, D. R., and Jayne, J. T.: The ToF-ACSM: a portable aerosol chemical speciation monitor with TOFMS detection, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 6, 3225–3241, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-6-3225-2013, 2013.

Gaikwad, S., Jeong, R., Kim, D., Lee, K., Jang, K.-S., Kim, C., and Song, M.: Microscopic observation of a liquid–liquid-(semi)solid phase in polluted PM2.5, Front Env. Sci. – Switz, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.947924, 2022.

Gao, J. J., Tian, H. Z., Cheng, K., Lu, L., Zheng, M., Wang, S. X., Hao, J. M., Wang, K., Hua, S. B., Zhu, C. Y., and Wang, Y.: The variation of chemical characteristics of PM2.5 and PM10 and formation causes during two haze pollution events in urban Beijing, China, Atmos. Environ., 107, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.02.022, 2015.

Gao, J. J., Wang, K., Wang, Y., Liu, S. H., Zhu, C. Y., Hao, J. M., Liu, H. J., Hua, S. B., and Tian, H. Z.: Temporal-spatial characteristics and source apportionment of PM2.5 as well as its associated chemical species in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China, Environ. Pollut., 233, 714–724, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.10.123, 2018.

Gao, Y. and Anderson, J. R.: Characteristics of Chinese aerosols determined by individual-particle analysis, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 106, 18037–18045, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000jd900725, 2001.

George, C., Ammann, M., D'Anna, B., Donaldson, D. J., and Nizkorodov, S. A.: Heterogeneous Photochemistry in the Atmosphere, Chem. Rev., 115, 4218–4258, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr500648z, 2015.

George, I. J. and Abbatt, J. P. D.: Heterogeneous oxidation of atmospheric aerosol particles by gas-phase radicalsm, Nat. Chem., 2, 713–722, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.806, 2010.

Ghorai, S. and Tivanski, A. V.: Hygroscopic Behavior of Individual Submicrometer Particles Studied by X-ray Spectromicroscopy, Anal. Chem., 82, 9289–9298, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac101797k, 2010.

Guo, S., Hu, M., Zamora, M. L., Peng, J. F., Shang, D. J., Zheng, J., Du, Z. F., Wu, Z. J, Shao, M., Zeng, L. M., Molina, M. J., and Zhang, R. Y.: Elucidating severe urban haze formation in China, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 17373–17378, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1419604111, 2014.

Hopkins, R. J., Tivanski, A. V., Marten, B. D., and Gilles, M. K.: Chemical bonding and structure of black carbon reference materials and individual carbonaceous atmospheric aerosols, J. Aerosol Sci., 38, 573–591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2007.03.009, 2007.

Huang, R. J., Zhang, Y., Bozzetti, C., Ho, K. F., Cao, J. J., Han, Y., Daellenbach, K. R., Slowik, J. G., Platt, S. M., Canonaco, F., Zotter, P., Wolf, R., Pieber, S. M., Bruns, E. A., Crippa, M., Ciarelli, G., Piazzalunga, A., Schwikowski, M., Abbaszade, G., Schnelle-Kreis, J., Zimmermann, R., An, Z. S., Szidat, S., Baltensperger, U., ElHaddad, I., and Prévôt, A. S. H.: High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China, Nature, 514, 218–222, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13774, 2014.

Huthwelker, T., Zelenay, V., Birrer, M., Krepelova, A., Raabe, J., Tzvetkov, G., Vernooij, M. G. C., and Ammann, M.: An in situ cell to study phase transitions in individual aerosol particles on a substrate using scanning transmission X-ray microspectroscopy, Rev. Sci. Instrum., 81, 113706, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3494604, 2010.

Jahl, L. G., Bowers, B. B., Jahn, L. G., Thornton, J. A., and Sullivan, R. C.: Response of the reaction probability of N2O5 with authentic biomass-burning aerosol to high relative humidity, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 2587–2598, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00227, 2021.

Jahn, L. G., Jahl, L. G., Bowers, B. B., and Sullivan, R. C.: Morphology of organic carbon coatings on biomass-burning particles and their role in reactive gas uptake, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 2184–2195, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00237, 2021.

Knopf, D. A., Wang, P., Wong, B., Tomlin, J. M., Veghte, D. P., Lata, N. N., China, S., Laskin, A., Moffet, R. C., Aller, J. Y., Marcus, M. A., and Wang, J.: Physicochemical characterization of free troposphere and marine boundary layer ice-nucleating particles collected by aircraft in the eastern North Atlantic, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 8659–8681, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-8659-2023, 2023.

Kolb, C. E., Cox, R. A., Abbatt, J. P. D., Ammann, M., Davis, E. J., Donaldson, D. J., Garrett, B. C., George, C., Griffiths, P. T., Hanson, D. R., Kulmala, M., McFiggans, G., Pöschl, U., Riipinen, I., Rossi, M. J., Rudich, Y., Wagner, P. E., Winkler, P. M., Worsnop, D. R., and O' Dowd, C. D.: An overview of current issues in the uptake of atmospheric trace gases by aerosols and clouds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 10561–10605, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-10561-2010, 2010.

Krieger, U. K., Marcolli, C., and Reid, J. P.: Exploring the complexity of aerosol particle properties and processes using single particle techniques, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6631–6662, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cs35082c, 2012.

Lata, N. N., Zhang, B., Schum, S., Mazzoleni, L., Brimberry, R., Marcus, M. A., Cantrell, W. H., Fialho, P., Mazzoleni, C., and China, S.: Aerosol Composition, Mixing State, and Phase State of Free Tropospheric Particles and Their Role in Ice Cloud Formation, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 3499–3510, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00315, 2021.

Latham, K. G., Simone, M. I., Dose, W. M., Allen, J. A., and Donne, S. W.: Synchrotron based NEXAFS study on nitrogen doped hydrothermal carbon: Insights into surface functionalities and formation mechanisms, Carbon, 114, 566–578, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2016.12.057, 2017.

Lei, L., Zhou, W., Chen, C., He, Y., Li, Z. J., Sun, J. X., Tang, X., Fu, P. Q., Wang, Z. F., and Sun, Y. L.: Long-term characterization of aerosol chemistry in cold season from 2013 to 2020 in Beijing, China, Environ. Pollut., 268, 115952, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115952, 2021.

Leinweber, P., Kruse, J., Walley, F. L., Gillespie, A., Eckhardt, K. U., Blyth, R. I. R., and Regier, T.: Nitrogen K-edge XANES – An overview of reference compounds used to identify 'unknown' organic nitrogen in environmental samples, J. Synchrotron Radiat., 14, 500–511, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0909049507042513, 2007.

Li, W. J., Shao, L. Y., Zhang, D. Z., Ro, C. U., Hu, M., Bi, X. H., Geng, H., Matsuki, A., Niu, H. Y., and Chen, J. M.: A review of single aerosol particle studies in the atmosphere of East Asia: morphology, mixing state, source, and heterogeneous reactions, J. Cleaner Prod., 112, 1330–1349, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.050, 2016.

Li, W. J., Liu, L., Zhang, J., Xu, L., Wang, Y. Y., Sun, Y. L., and Shi, Z. B.: Microscopic Evidence for Phase Separation of Organic Species and Inorganic Salts in Fine Ambient Aerosol Particles, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 2234–2242, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02333, 2021.

Li, Y. J., Sun, Y. L., Zhang, Q., Li, X., Li, M., Zhou, Z., and Chan, C. K.: Real-time chemical characterization of atmospheric particulate matter in China: A review, Atmos. Environ., 158, 270–304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.02.027, 2017.

Liu, Z., Gao, W., Yu, Y., Hu, B., Xin, J., Sun, Y., Wang, L., Wang, G., Bi, X., Zhang, G., Xu, H., Cong, Z., He, J., Xu, J., and Wang, Y.: Characteristics of PM2.5 mass concentrations and chemical species in urban and background areas of China: emerging results from the CARE-China network, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 8849–8871, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-8849-2018, 2018.

Martin, S. T.: Phase transitions of aqueous atmospheric particles, Chem. Rev., 100, 3403–3453, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr990034t, 2001.

McCormick, R. A. and Ludwig, J. H.: Climate Modification by Atmospheric Aerosols, Science, 156, 1358–1359, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.156.3780.1358, 1967.

Middlebrook, A. M., Bahreini, R., Jimenez, J. L., and Canagaratna, M. R.: Evaluation of Composition-Dependent Collection Efficiencies for the Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer using Field Data, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 46, 258–271, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2011.620041, 2012.

Mikhailov, E. F., Mironov, G. N., Pöhlker, C., Chi, X., Krüger, M. L., Shiraiwa, M., Förster, J.-D., Pöschl, U., Vlasenko, S. S., Ryshkevich, T. I., Weigand, M., Kilcoyne, A. L. D., and Andreae, M. O.: Chemical composition, microstructure, and hygroscopic properties of aerosol particles at the Zotino Tall Tower Observatory (ZOTTO), Siberia, during a summer campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 8847–8869, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-8847-2015, 2015.

Moffet, R. C., Henn, T., Laskin, A., and Gilles, M. K.: Automated Chemical Analysis of Internally Mixed Aerosol Particles Using X-ray Spectromicroscopy at the Carbon K-Edge, Anal. Chem., 82, 7906–7914, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac1012909, 2010a.

Moffet, R. C., Henn, T. R., Tivanski, A. V., Hopkins, R. J., Desyaterik, Y., Kilcoyne, A. L. D., Tyliszczak, T., Fast, J., Barnard, J., Shutthanandan, V., Cliff, S. S., Perry, K. D., Laskin, A., and Gilles, M. K.: Microscopic characterization of carbonaceous aerosol particle aging in the outflow from Mexico City, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 961–976, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-961-2010, 2010b.

Moffet, R. C., Tivanski, A. V., and Gilles, M. K.: Scanning Transmission X-ray Microscopy Applications in Atmospheric Aerosol Research, Fundamentals and Applications in Aerosol Spectroscopy, edited by: Signorell, R., and Reid, J. P., CRC Press, USA, 419–462, ISBN: 9781420085617, 2011.

Moffet, R. C., Rödel, T. C., Kelly, S. T., Yu, X. Y., Carroll, G. T., Fast, J., Zaveri, R. A., Laskin, A., and Gilles, M. K.: Spectro-microscopic measurements of carbonaceous aerosol aging in Central California, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 10445–10459, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-10445-2013, 2013.

Moffet, R. C., O'Brien, R. E., Alpert, P. A., Kelly, S. T., Pham, D. Q., Gilles, M. K., Knopf, D. A., and Laskin, A.: Morphology and mixing of black carbon particles collected in central California during the CARES field study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 14515–14525, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-14515-2016, 2016.

Mori, T., Goto-Azuma, K., Kondo, Y., Ogawa-Tsukagawa, Y., Miura, K., Hirabayashi, M., Oshima, N., Koike, M., Kupiainen, K., Moteki, N., Ohata, S., Sinha, P. R., Sugiura, K., Aoki, T., Schneebeli, M., Steffen, K., Sato, A., Tsushima, A., Makarov, V., Omiya, S., Sugimoto, A., Takano, S., and Nagatsuka, N.: Black carbon and inorganic aerosols in Arctic snowpack, JGR. Atmos., 124, 13325–13356, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030623, 2019.

Mori, T., Moteki, N., Ohata, S., Koike, M., Goto-Azuma, K., Miyazaki, Y., and Kondo, Y.: Improved technique for measuring the size distribution of black carbon particles in liquid water, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 50, 242–254, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2016.1147644, 2016.

Noll, K. E., Mueller, P. K., and Imada, M.: Visibility and aerosol concentration in urban air, Atmos. Environ., 2, 465–475, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(68)90040-1, 1968.

O'Brien, R. E., Neu, A., Epstein, S. A., Macmillan, A. C., Wang, B. B., Kelly, S. T., Nizkorodov, S. A., Laskin, A., Moffet, R. C., and Gilles, M. K.: Physical properties of ambient and laboratory-generated secondary organic aerosol, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 4347–4353, orghttps://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL060219, 2014.

O'Brien, R. E., Wang, B. B., Kelly, S. T., Lundt, N., You, Y., Bertram, A. K., Leone, S. R., Laskin, A., and Gilles, M. K.: Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation in Aerosol Particles: Imaging at the Nanometer Scale, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 4995–5002, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b00062, 2015.

Peng, C., Chen, L. X. D., and Tang, M. J.: A database for deliquescence and efflorescence relative humidities of compounds with atmospheric relevance, Fundam. Res., 2, 578–587, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2021.11.021, 2022.

Penner, J. E. and Novakov, T.: Carbonaceous particles in the atmosphere: A historical perspective to the Fifth International Conference on Carbonaceous Particles in the Atmosphere, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 101, 19373–19378, https://doi.org/10.1029/96JD01175, 1996.

Petters, M. D. and Kreidenweis, S. M.: A single parameter representation of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nucleus activity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 1961–1971, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-1961-2007, 2007.

Piens, D. S., Kelly, S. T., Harder, T. H., Petters, M. D., O'Brien, R. E., Wang, B. B., Teske, K., Dowell, P., Laskin, A., and Gilles, M. K.: Measuring Mass-Based Hygroscopicity of Atmospheric Particles through in Situ Imaging, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 5172–5180, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b00793, 2016.

Pöhlker, C., Saturno, J., Krüger, M. L., Förster, J. D., Weigand, M., Wiedemann, K. T., Bechtel, M., Artaxo, P., and Andreae, M. O.: Efflorescence upon humidification? X-ray microspectroscopic in situ observation of changes in aerosol microstructure and phase state upon hydration, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 3681–3689, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014gl059409, 2014.

Pósfai, M. and Buseck, P. R.: Nature and climate effects of individual tropospheric aerosol particles, Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 38, 17–43, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100032, 2010.

Prather, K. A., Bertram, T. H., Grassian, V. H., Deane, G. B., Stokes, M. D., DeMott, P. J., Aluwihare, L. I., Palenik, B. P., Azam, F., Seinfeld, J. H., Moffet, R. C., Molina, M. J., Cappa, C. D., Geiger, F. M., Roberts, G. C., Russell, L. M., Ault, A. P., Baltrusaitis, J., Collins, D. B., Corrigan, C. E., Cuadra-Rodriguez, L. A., Ebben, C. J., Forestieri, S. D., Guasco, T. L., Hersey, S. P., Kim, M. J., Lambert, W. F., Modini, R. L., Mui, W., Pedler, B. E., Ruppel, M. J., Ryder, O. S., Schoepp, N. G., Sullivan, R. C., and Zhao, D. F.: Bringing the ocean into the laboratory to probe the chemical complexity of sea spray aerosol, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 7550–7555, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1300262110, 2013.

Raabe, J., Tzvetkov, G., Flechsig, U., Böge, M., Jaggi, A., Sarafimov, B., Vernooij, M. G. C., Huthwelker, T., Ade, H., Kilcoyne, D., Tyliszczak, T., Fink, R. H., and Quitmann, C.: PolLux: A new facility for soft X-ray spectromicroscopy at the Swiss Light Source, Rev. Sci. Instrum., 79, 113704, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3021472, 2008.

Rasool, S. I. and Schneider, S. H.: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide and Aerosols: Effects of Large Increases on Global Climate, Science, 173, 138–141, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.173.3992.138, 1971.

Resch, J., Wolfer, K., Barth, A., and Kalberer, M.: Effects of storage conditions on the molecular-level composition of organic aerosol particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 9161–9171, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-9161-2023, 2023.

Reynolds, R. S. and Wilson, K. R.: Unraveling the Meaning of Effective Uptake Coefficients in Multiphase and Aerosol Chemistry, Acc. Chem. Res., 58, 366–374, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.4c00662, 2025.

Riemer, N., Ault, A. P., West, M., Craig, R. L., and Curtis, J. H.: Aerosol Mixing State: Measurements, Modeling, and Impacts, Rev. Geophys., 57, 187–249, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018rg000615, 2019.

Shao, L. Y., Liu, P. J., Jones, T., Yang, S. S., Wang, W. H., Zhang, D. Z., Li, Y. W., Yang, C.-X., Xing, J. P., Hou, C., Zhang, M. Y., Feng, X. L., Li, W. J., and BéruBé K.: A review of atmospheric individual particle analyses: Methodologies and applications in environmental research, Gondwana Res., 110, 347–369, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2022.01.007, 2022.

Shen, X. J., Sun, J. Y., Zhang, X. Y., Zhang, Y. M., Zhong, J. T., Wang, X., Wang, Y. Q., and Xia, C.: Variations in submicron aerosol liquid water content and the contribution of chemical components during heavy aerosol pollution episodes in winter in Beijing, Sci. Total Environ., 693, 133521, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.327, 2019.

Slowik, J. G., Cziczo, D. J., and Abbatt, J. P. D.: Analysis of cloud condensation nuclei composition and growth kinetics using a pumped counterflow virtual impactor and aerosol mass spectrometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 4, 1677–1688, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-4-1677-2011, 2011.

Smith, J. W., Lam, R. K., Shih, O., Rizzuto, A. M., Prendergast, D., and Saykally, R. J.: Properties of aqueous nitrate and nitrite from X-ray absorption spectroscopy, J. Chem. Phys., 143, 084503, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4928867, 2015.

Song, M., Jeong, R., Kim, D., Qiu, Y. T., Meng, X. X. Y., Wu, Z. J., Zuend, A., Ha, Y., Kim, C., Kim, H., Gaikwad, S., Jang, K. S., Lee, J. Y., and Ahn, J.: Comparison of Phase States of PM2.5 over Megacities, Seoul and Beijing, and Their Implications on Particle Size Distribution, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 17581–17590, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c06377, 2022.

Stokes, R. H. and Robinson, R. A.: Interactions in aqueous nonelectrolyte solutions. I. Solute-solvent equilibria, J. Phys. Chem., 70, 2126–2131, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100879a010, 1966.

Su, H., Cheng, Y. F., and Pöschl, U.: New Multiphase Chemical Processes Influencing Atmospheric Aerosols, Air Quality, and Climate in the Anthropocene, Acc. Chem. Res., 53, 2034–2043, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00246, 2020.

Sun, Y. L., Wang, Z. F., Fu, P. Q., Yang, T., Jiang, Q., Dong, H. B., Li, J., and Jia, J. J.: Aerosol composition, sources and processes during wintertime in Beijing, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 4577–4592, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-4577-2013, 2013.

Tang, L. Z., Shang, D. J., Fang, X., Wu, Z. J., Qiu, Y. T., Chen, S. Y., Li, X., Zeng, L. M., Guo, S., and Hu, M.: More Significant Impacts From New Particle Formation on Haze Formation During COVID-19 Lockdown, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2020GL091591, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020gl091591, 2021.

Tang, M., Chan, C. K., Li, Y. J., Su, H., Ma, Q., Wu, Z., Zhang, G., Wang, Z., Ge, M., Hu, M., He, H., and Wang, X.: A review of experimental techniques for aerosol hygroscopicity studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 12631–12686, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-12631-2019, 2019.

Tang, M. J., Cziczo, D. J., and Grassian, V. H.: Interactions of Water with Mineral Dust Aerosol: Water Adsorption, Hygroscopicity, Cloud Condensation, and Ice Nucleation, Chem. Rev., 116, 4205–4259, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00529, 2016.

Tomlin, J. M., Weis, J., Veghte, D. P., China, S., Fraund, M., He, Q., Reicher, N., Li, C., Jankowski, K. A., Rivera-Adorno, F. A., Morales, A. C., Rudich, Y., Moffet, R. C., Gilles, M. K., and Laskin, A.: Chemical composition and morphological analysis of atmospheric particles from an intensive bonfire burning festival, Environ. Sci.: Atmos., 2, 616–633, https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ea00037g, 2022.

Ueda, S., Ohata, S., Iizuka, Y., Seki, O., Matoba, S., Matsui, H., Koike, M., and Kondo, Y.: Evaluation of sample storage methods for single particle analyses of black carbon in snow and ice: Merits and risks of glass and plastic vials for melted sample storage, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2025.2542900, 2025.

Ulbrich, I. M., Canagaratna, M. R., Zhang, Q., Worsnop, D. R., and Jimenez, J. L.: Interpretation of organic components from Positive Matrix Factorization of aerosol mass spectrometric data, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2891–2918, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2891-2009, 2009.

Wagner, N. L., Riedel, T. P., Young, C. J., Bahreini, R., Brock, C. A., Dubé, W. P., Kim, S., Middlebrook, A. M., Öztürk, F., Roberts, J. M., Russo, R., Sive, B., Swarthout, R., Thornton, J. A., VandenBoer, T. C., Zhou, Y., and Brown, S. S.: N2O5 uptake coefficients and nocturnal NO2 removal rates determined from ambient wintertime measurements, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 118, 9331–9350, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50653, 2013.

Wang, H. C. and Lu, K. D.: Determination and Parameterization of the Heterogeneous Uptake Coefficient of Dinitrogen Pentoxide (N2O5), Prog. Chem., 28, 917–933, https://manu56.magtech.com.cn/progchem/CN/10.7536/PC151225 (last access: 15 December 2025), 2016.

Wang, Y. C., Chen, J., Wang, Q. Y., Qin, Q. D., Ye, J. H., Han, Y. M., Li, L., Zhen, W., Zhi, Q., Zhang, Y. X, and Cao, J. J.: Increased secondary aerosol contribution and possible processing on polluted winter days in China, Environ. Int., 127, 78–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.021, 2019.

Wang, Y. S., Yao, L., Wang, L. L., Liu, Z. R., Ji, D. S., Tang, G. Q., Zhang, J. K., Sun, Y., Hu, B., and Xin, J. Y.: Mechanism for the formation of the January 2013 heavy haze pollution episode over central and eastern China, Sci. China: Earth Sci., 57, 14–25, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-013-4773-4, 2014.

Warwick, T., Franck, K., Kortright, J. B., Meigs, G., Moronne, M., Myneni, S., Rotenberg, E., Seal, S., Steele, W. F., Ade, H., Garcia, A., Cerasari, S., Delinger, J., Hayakawa, S., Hitchcock, A. P., Tyliszczak, T., Kikuma, J., Rightor, E. G., Shin, H. J., and Tonner, B. P.: A scanning transmission X-ray microscope for materials science spectromicroscopy at the advanced light source, Rev. Sci. Instrum., 69, 2964–2973, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1149041, 1998.

Wendl, I. A., Menking, J. A., Färber, R., Gysel, M., Kaspari, S. D., Laborde, M. J. G., and Schwikowski, M.: Optimized method for black carbon analysis in ice and snow using the Single Particle Soot Photometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 2667–2681, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-2667-2014, 2014.

Wu, L. and Ro, C. U.: Aerosol Hygroscopicity on A Single Particle Level Using Microscopic and Spectroscopic Techniques: A Review, Asian J. Atmos. Environ., 14, 177–209, https://doi.org/10.5572/ajae.2020.14.3.177, 2020.

Wu, Z. J., Hu, M., Liu, S., Wehner, B., Bauer, S., Maßling, A., Wiedensohler, A., Petäjä, T., Dal Maso, M., and Kulmala, M.: New particle formation in Beijing, China: Statistical analysis of a 1 year data set, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 112, D0920, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007406, 2007.

Wu, Z. J., Zheng, J., Shang, D. J., Du, Z. F., Wu, Y. S., Zeng, L. M., Wiedensohler, A., and Hu, M.: Particle hygroscopicity and its link to chemical composition in the urban atmosphere of Beijing, China, during summertime, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 1123–1138, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-1123-2016, 2016.

Wu, Z. J., Zheng, J., Wang, Y., Shang, D. J., Du, Z. F., Zhang, Y. H., and Hu, M.: Chemical and physical properties of biomass burning aerosols and their CCN activity: A case study in Beijing, China, Sci. Total Environ., 579, 1260–1268, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.112, 2017.

Xiao, Z. M., Xu, H., Gao, J. Y., Cai, Z. Y., Bi, W. K., Li, P., Yang, N., Deng, X. W., Ji, Y. F.: Characteristics and Sources of PM2.5-O3 Compound Pollution in Tianjin, Environmental Science (Chinese), 43, 1140–1150, https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.202108164, 2022.

You, Y., Renbaum-Wolff, L., Carreras-Sospedra, M., Hanna, S. J., Hiranuma, N., Kamal, S., Smith, M. L., Zhang, X. L., Weber, R. J., Shilling, J. E., Dabdub, D., Martin, S. T., and Bertram, A. K.: Images reveal that atmospheric particles can undergo liquid–liquid phase separations, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 13188–13193, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1206414109, 2012.

You, Y., Renbaum-Wolff, L., and Bertram, A. K.: Liquid–liquid phase separation in particles containing organics mixed with ammonium sulfate, ammonium bisulfate, ammonium nitrate or sodium chloride, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 11723–11734, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-11723-2013, 2013.

You, Y., Smith, M. L., Song, M. J., Martin, S. T., and Bertram, A. K.: Liquid–liquid phase separation in atmospherically relevant particles consisting of organic species and inorganic salts, Int. Rev. Phys. Chem., 33, 43–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144235x.2014.890786, 2014.

Yu, X., Li, Q. F., Liao, K. Z., Li, Y. M., Wang, X. M., Zhou, Y., Liang, Y. M., and Yu, J. Z.: New measurements reveal a large contribution of nitrogenous molecules to ambient organic aerosol, npj Clim. Atmos. Sci., 7, 72, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00620-6, 2024.

Zelenay, V., Ammann, M., Křepelová, A., Birrer, M., Tzvetkov, G., Vernooij, M. G. C., Raabe, J., and Huthwelker, T.: Direct observation of water uptake and release in individual submicrometer sized ammonium sulfate and ammonium sulfate/adipic acid particles using X-ray microspectroscopy, J. Aerosol Sci., 42, 38–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2010.11.001, 2011a.

Zelenay, V., Huthwelker, T., Krepelová, A., Rudich, Y., and Ammann, M.: Humidity driven nanoscale chemical separation in complex organic matter, Environ. Chem., 8, 450–460, https://doi.org/10.1071/en11047, 2011b.

Zhang, J., Wang, Y. Y., Teng, X. M., Liu, L., Xu, Y. S., Ren, L. H., Shi, Z. B., Zhang, Y., Jiang, J. K., Liu, D. T., Hu, M., Shao, L. Y., Chen, J. M., Martin, S. T., Zhang, X. Y., and Li, W. J.: Liquid–liquid phase separation reduces radiative absorption by aged black carbon aerosols, Commun. Earth Environ., 3, 128, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00462-1, 2022.

Zhao, X. J., Zhao, P. S., Xu, J., Meng, W., Pu, W. W., Dong, F., He, D., and Shi, Q. F.: Analysis of a winter regional haze event and its formation mechanism in the North China Plain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 5685–5696, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-5685-2013, 2013.

Zheng, Y., Cheng, X., Liao, K., Li, Y., Li, Y. J., Huang, R.-J., Hu, W., Liu, Y., Zhu, T., Chen, S., Zeng, L., Worsnop, D. R., and Chen, Q.: Characterization of anthropogenic organic aerosols by TOF-ACSM with the new capture vaporizer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 13, 2457–2472, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-13-2457-2020, 2020.

Zheng, Y., Miao, R. Q., Zhang, Q., Li, Y. W., Cheng, X., Liao, K. R., Koenig, T. K., Ge, Y. L., Tang, L. Z., Shang, D. J., Hu, M., Chen, S. Y., and Chen, Q.: Secondary Formation of Submicron and Supermicron Organic and Inorganic Aerosols in a Highly Polluted Urban Area, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 128, e2022JD037865, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jd037865, 2023.

Ziemann, P. J. and Atkinson, R.: Kinetics, products, and mechanisms of secondary organic aerosol formation, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6582–6605, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cs35122f, 2012.

Zong, T. M., Wang, H. C., Wu, Z. J., Lu, K. D., Wang, Y., Zhu, Y. S., Shang, D. J., Fang, X., Huang, X. F., He, L. Y., Ma, N., Gröss, J., Huang, S., Guo, S., Zeng, L. M., Herrmann, H., Wiedensohler, A., Zhang, Y. H., and Hu, M.: Particle hygroscopicity inhomogeneity and its impact on reactive uptake, Sci. Total Environ., 811, 151364, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151364, 2022.