the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Understanding the causes of satellite–model discrepancies in aerosol–cloud interactions using near-LES simulations of marine boundary layer clouds

Shaoyue Qiu

Hsiang-He Lee

Xiaoli Zhou

Aerosol–cloud interactions (ACI) remain the largest source of uncertainty in model estimates of anthropogenic radiative forcing, primarily because of deficiencies in representing aerosol–cloud microphysical processes that lead to inconsistent cloud liquid water path (LWP) responses to aerosol perturbations between observations and models. To investigate this discrepancy, we conducted a series of large-eddy-scale simulations driven by realistic meteorology over the eastern North Atlantic, and evaluated LWP susceptibility, precipitation processes, and boundary layer thermodynamics using satellite and ground-based observations.

Simulated LWP responses show a strong dependence on cloud state. Non-precipitating thin clouds exhibit a modest LWP decrease with increasing cloud droplet number concentration (Nd), consistent in sign but weaker in magnitude than satellite estimates, reflecting enhanced turbulent mixing and evaporation. The largest model-observation discrepancy occurs in non-precipitating thick clouds, where simulated LWP susceptibilities are strongly positive (+0.32) while observations indicate large negative values (−0.69). This discrepancy stems from excessive precipitation driven by underestimated entrainment, overly active accretion, and overly broad drop-size distributions in polluted conditions. While our high-resolution setup mitigates the excessive drizzling common in coarser models and captures key regime transitions, these biases persist – highlighting that improved parameterizations of cloud-top processes, precipitation, and aerosol effects are needed beyond simply increasing model resolution.

Additionally, misrepresented moisture inversions in reanalysis introduce a moist bias in cloud-top relative humidity, further amplifying positive LWP susceptibility. Our results also suggest that large negative Nd–LWP relationships in observations may reflect internal cloud processes rather than true ACI effects.

- Article

(9218 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(11141 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Marine boundary layer clouds exhibit substantial influence on Earth's radiation balance due to their high albedo and extensive global coverage. Aerosols modulate cloud albedo through changing cloud droplet number concentration (Nd), cloud liquid water path (LWP), and cloud fraction. The estimated radiative cooling from aerosols partially offsets the warming from greenhouse gas emissions (Slingo, 1990). However, aerosol-cloud interaction (ACI) remains the most uncertain component of anthropogenic radiative forcing (Forster et al., 2021). In particular, liquid-phase cloud adjustments in LWP, cloud fraction, and cloud lifetime present the largest uncertainties in determining the net radiative forcing of ACIs, especially under varying large-scale conditions (Han et al., 2002; Small et al., 2009).

Among these uncertainties, the LWP response to aerosol perturbations has drawn particular attention due to its large spread in both observations and numerical model simulations. Theoretically, increasing aerosols would reduce droplet size and suppress precipitation, thereby increasing LWP and cloud lifetime (Albrecht, 1989). However, smaller droplets might also enhance evaporation and entrainment, leading to a reduced LWP in non-precipitating clouds (Ackerman et al., 2004; Xue and Feingold, 2006; Bretherton et al., 2007). This competition between processes leads to a bifurcated LWP response that varies with aerosol concentration, cloud type, and background meteorology.

In recent years, numerous satellite studies have reported an overall decrease of LWP with increasing Nd for non-precipitating clouds in polluted environments and an increase in LWP for precipitating clouds (e.g., Gryspeerdt et al., 2019, 2021; Toll et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang and Feingold, 2023; Qiu et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2023, 2024). In contrast, current global climate models (GCMs) mostly simulate a positive LWP response to aerosol perturbation regardless the cloud conditions, which leads to an over-estimation of the aerosol-induced radiative forcing that is dominated by ACI (e.g., Ghan et al., 2016; Michibata et al., 2016; Mülmenstädt et al., 2024). This discrepancy could stem from poorly resolved cloud processes in GCMs due to their coarse horizontal resolution (∼100 km).

Recent development in computing have enabled the global convection-permitting models (GCPMs) with kilometer-scale grid spacing, serving as an invaluable complement to the traditional climate models (e.g. Satoh et al., 2019; Stevens et al., 2019; Caldwell et al., 2021; Donahue et al., 2024). Notably, Sato et al. (2018) employed a GCPM and simulated a negative LWP response, attributing it primarily to better resolved evaporation and condensation processes from aerosol perturbations. Yet, other CPM studies with finer resolution than Sato et al. (2018) mostly simulate an increase in LWP with aerosol perturbations (e.g., Fons et al., 2024; Christensen et al, 2024), largely due to uncertainties in microphysics schemes, particularly regarding the treatment of precipitation (White et al., 2017).

Since most current GCPMs and GCMs adopt two-moment microphysics schemes, it is important to evaluate precipitation parameterizations using observational constraints, and to examine their influences on simulated ACI. Meanwhile, Terai et al. (2020) found that the lack of LWP decrease in kilometer-scale models may result from unresolved sub-kilometer processes most relevant to ACI. For example, when increasing model resolution from 4 km to 250 m, the fraction of precipitating clouds decreased substantially, especially for thick clouds, and the LWP response becomes negative for non-precipitating clouds. Therefore, it is critical to assess the benefit of increasing model resolution to near large-eddy simulation (LES) scale in representing precipitation and evaporation-entrainment feedback without altering microphysics parameterization structure, and to reconcile satellite-observed LWP adjustments with those simulated by GCMs and GCPMs.

With model resolutions ranging from 25 to 200 m, numerous LES studies have utilized idealized meteorological conditions and provided valuable process-level insights into the mechanisms governing cloud responses to aerosol perturbations (e.g., Xue and Feingold, 2006; Xue et al., 2008; Bretherton et al., 2007; Seifert et al., 2015; Glassmeier et al., 2019; Hoffmann et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). However, idealized simulations cannot be directly evaluated or constrained by observations, limiting their ability to explain divergent LWP responses. Additionally, many LES studies employ limited domain size that cannot resolve mesoscale organization and variability of clouds and precipitation, which significantly influence retrieved Nd–LWP relationships (e.g., Zhou and Feingold, 2023; Kokkola et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2025). Finally, aerosol and cloud fields are strongly modulated by synoptic conditions (e.g., Engström and Ekman, 2010; Zheng et al., 2011, 2025). LES studies focusing on a few cases fail to capture the influence of cloud regimes and synoptic variability on the sign and magnitude of ACI.

The eastern North Atlantic (ENA) region is uniquely suited to address this issue due to its location at the transition between midlatitude and subtropical regimes (e.g., Rémillard and Tselioudis, 2015; Zheng et al., 2025). Long-term, high-quality ground-based observations from the DOE Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) program enable comprehensive and process-level evaluation. Marine boundary layer (MBL) clouds in this region frequently drizzle and are sensitive to aerosol and meteorological perturbations, making them ideal for studying aerosol-cloud-precipitation interactions (Wood et al., 2015).

The goal of this study is to evaluate key ACI processes, such as precipitation suppression and evaporation-entrainment feedback, as well as precipitation treatment in a two-moment scheme using simulations approaching LES scale. To address limitations in previous LES studies, we employ a nested-domain configuration to simulate realistic circulations across synoptic regimes, with the innermost domain spanning 1° × 1°, consistent with typical GCM grid spacing and satellite analysis scales. We simulated an ensemble of MBL cloud cases across three synoptic regimes characterized by northerly surface flow over the ENA site. Regime classification follows Zheng et al. (2025). To enable a process-level evaluation of warm-rain parameterization, we leverage ARM ground-based radar measurement and apply a newly developed radar simulator for direct model-observation comparison.

2.1 Datasets

This study adopts both satellite and ground-based observations to assess the simulated cloud, precipitation processes, and ACI processes. For satellite observations, we used cloud retrievals derived from the Spinning Enhanced Visible InfraRed Imager (SEVIRI) on the geostationary satellite Meteosat-10 and Meteosat-11 over the ENA region. The cloud retrievals are based on the methods developed by the Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) project using the Satellite ClOud and Radiation Property retrieval System (SatCORPS) algorithms (Minnis et al., 2011, 2021; Painemal et al., 2021). The SEVIRI Meteosat cloud retrieval products are pixel-level cloud retrievals produced by NASA LaRC SatCORPS group, specifically tailored to support the ARM program over the ARM ground-based observation sites. For Meteosat-10 and Meteosat-11 cloud retrievals, the products have a spatial resolution of 4 and 3 km at nadir and temporal resolutions of hourly and half-hourly, respectively.

In this study, we used the cloud mask, cloud effective radius (re), cloud optical depth (τ), LWP, cloud phase, and cloud top height variables in the SEVIRI Meteosat cloud retrieval product (Minnis et al., 2011, 2021). We focus on warm boundary layer clouds with cloud top below 3km and a liquid cloud phase. The re and τ retrievals are based on the shortwave-infrared split window technique during the daytime. Cloud LWP is derived from re and τ using the equation: , where Qext represents the extinction efficiency and is assumed to be constant at 2.0. Cloud mask algorithm is consistent with the CERES Ed-4 algorithm, as described in Trepte et al. (2019), where cloudy and clear pixels are distinguished based on the calculated TOA clear-sky radiance. Cloud top height is derived from the retrieved cloud effective and top temperature, together with the boundary-layer temperature profiles and lapse rate, as described in Sun-Mack et al. (2014). Cloud Nd is retrieved based on the adiabatic assumptions for warm boundary layer clouds, based on the following equation:

In Eq. (1), k represents the ratio between the volume mean radius and re, and it is assumed to be constant of 0.8 for stratocumulus, fad is the adiabatic fraction, cw is the condensation rate, Qext is the extinction coefficient, and ρw is the density of liquid water (Grosvenor et al., 2018).

To facilitate a consistent comparison, the satellite retrievals are adjusted to the same domain size as the simulation (e.g., 1° × 1°) and the pixel-level cloud retrievals are smoothed to 25 km resolution to reduce impact from cloud heterogeneity and small-scale covariability on the estimated cloud susceptibility (e.g. Arola et al., 2022; Zhou and Feingold, 2023). In the context of ACI: cloud susceptibility quantifies how sensitive a cloud property responds to change in aerosol concentration or Nd. To constrain the spatial-temporal variation in meteorological conditions and cloud properties, cloud susceptibility is estimated as the regression slope between Nd and cloud properties within the 1° × 1° domain at each time step of satellite observations. In this study, we quantify LWP and cloud fraction (CF) susceptibilities. Because of the non-linear relations between LWP and Nd, the LWP susceptibility is quantified in logarithm scale as ) (e.g., Gryspeerdt et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2024), whereas CF susceptibility is quantified as ) (e.g., Kaufman et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2024). Due to the dependence of cloud responses on cloud regimes (e.g., Chen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2024), the estimated cloud susceptibilities are displayed in the Nd–LWP parameter space as the classification of cloud states.

In addition to the satellite retrievals, we adopt the ground-based observation at the ARM ENA site. Specifically, we use the ground-based cloud radar and lidar observations for process-level evaluation of modeled precipitation processes. In this study, the radar reflectivity (Ze) and cloud boundaries are from the Active Remote Sensing of Clouds (ARSCL) value added product (Clothiaux et al., 2001). To remove noise in the data, we smoothed the 4 s reflectivity profiles into 1 min. Cloud top height is derived as the upper most range gate height with radar reflectivity greater than the sensitivity threshold of the Ka-band zenith radar (−40 dBZ) combined with the hydrometer layer top data in the ARSCL. Cloud base height is from the best-estimate cloud base height variable in the ARSCL product. Thermodynamic profiles are derived from the radiosonde data, which is launched at the ENA site twice daily at 00:00 and 12:00 UTC.

The ground-based re and τ retrievals are based on the parameterization developed in Dong et al. (1998), where re is retrieved from a radiative transfer model as described in Dong et al. (1997) and parameterized as a function of cloud LWP, shortwave transmission ratio, and cosine of solar zenith angle. Cloud LWP is retrieved from the brightness temperature measured by the three-channel microwave radiometer (MWR3C) at 23.8, 30, and 90 GHz (Cadeddu et al., 2013). The shortwave transmission ratio is calculated from the unshaded pyranometer from the QCRAD product (Long and Shi, 2006), defined as the ratio between cloudy and clear-sky shortwave irradiance.

Meteorological and thermodynamic variables are extracted from the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 reanalysis data and used as the forcing for the simulation. ERA5 is the fifth generation of the ECMWF reanalysis, replacing the ERA-Interim reanalysis. ERA5 provides the best-estimate of the global atmosphere, land surface, and ocean waves with a horizontal resolution of 31 km and an hourly output throughout (Hersbach et al., 2020). Atmospheric variables are available on 137 vertical levels, ranging from 1000 hPa (near surface) to 1 Pa (∼80 km).

2.2 WRF model

We used the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model version 4.4.2 (Skamarock et al., 2021) for our simulations. In a companion study, Lee et al. (2025) used the WRF model at near LES scale with interactive chemistry and aerosol schemes (WRF-Chem) and investigated ACI and its feedback on both clouds and aerosols in the ENA region. As the WRF-Chem simulations are 5–10 times more computationally expensive, the present study adopted the same dynamical and physical configuration and conducted more experiments with prescribed aerosol concentrations and realistic meteorology.

We employed four one-way nested domains in the model, with the domain size of 27° × 27°, 9° × 9°, 3° × 3°, and 1° × 1°, and spatial resolution of 5 km, 1.67 km, 0.56 km, and 190 m, respectively, for d01, d02, d03, and d04 domain. The innermost domain (d04) exhibits a domain size close to most GCM grid spacing and is consistent with the spatial scale for quantification of cloud susceptibility in satellite study (e.g., Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang and Feingold, 2023; Qiu et al., 2024). The spatial resolution of 190 m is much higher than the CPMs and close to the LES scale. All the analyses and evaluations in this study are based on output from the innermost domain (d04). There are 75 vertical levels in the model with a model top of ∼20 km, the grid spacing is log-stretched with higher resolution of ∼50 m near the surface and increases to ∼150 m at the height of ∼1500 m. As mentioned above, the initial and lateral boundary conditions for the outer domain are taken from the ERA5 reanalysis data.

The simulations are performed using the Rapid Radiative Transfer Model for Global Climate Models (RRTMG; Mlawer et al., 1997), and the Noah land surface model (Chen and Dudhia, 2001). The Mellor–Yamada–Janjic (MYJ; Mellor and Yamada, 1982) planetary boundary layer (PBL) scheme and the shallow cumulus schemes (Hong and Jang, 2018) are utilized for the outer domain (d01 and d02) only. Simulations in this study employ a two-moment Morrison microphysics scheme, which has been widely implemented in both CPMs and GCMs (Morrison et al., 2005; Morrison and Gettelman, 2008; Golaz et al., 2022). In the Morrison two-moment microphysics scheme, the DSD (ϕ) is defined as:

where D is the diameter, N0 is the intercept parameter, μ is the shape parameter, λ is the slope parameter, η is the dispersion parameter which governs the width of the DSD (Morrison and Gettelman, 2008).

Instead of prescribing a constant cloud droplet number concentration, total aerosol number concentrations are prescribed as a constant throughout the domain with no explicit vertical variation or transport in all simulations. Aerosol activation follows the parameterization of Abdul-Razzak and Ghan (2000), with fixed assumptions for size distribution, chemical composition, aerosol type, and mixing state. The activated fraction mainly depends on the local supersaturation and updraft speed. The fixed aerosol field neglects spatial and temporal variability driven by emissions, long-range transport, wet scavenging, and CCN reactivation from evaporated raindrops. These missing processes can sustain higher CCN concentrations, suppress precipitation, and potentially exaggerate positive LWP responses.

Despite this simplification, our companion WRF-Chem study (Lee et al., 2025) shows that, even with full aerosol microphysics, wet scavenging, and aerosol reactivation, the simulated LWP responses remain broadly consistent with the results presented here, especially the positive susceptibility in precipitating clouds. This agreement suggests that the key findings of this work are robust, although the prescribed-aerosol assumption may still contribute to some of the quantitative discrepancies discussed in Sect. 3.

For each case, we run the model for 36 h (except for the consecutive case on 21 July 2016, where the model was run for 60 h), starting at 12:00 UTC of the previous day and the first 12 h are used as model spin-up period. The time resolution of the model is 30 s in the outer domain for advection and physics calculation and is 1 s for the innermost domain. Model variables are output instantaneously for every 10 min for the innermost domain, similar to the snapshot frequency of satellite observations.

To access the cloud responses to aerosol perturbations, we conduct three sets of simulations with different prescribed aerosol number concentration of N=100, 500, and 1000 cm−3 for all 11 cases. Cloud susceptibility is quantified as the change in domain-mean cloud properties within the innermost domain at the same output time, comparing polluted and clean simulations (e.g. N=1000 vs. N=100, N=500 vs. N=100, and N=1000 vs. N=500). With constant and uniform aerosol concentration, the Nd–LWP relations resulting from internal cloud processes are able to be quantified within each experiment at the same output time. To minimize Nd–LWP relations from cloud heterogeneity and small-scale covariability and to be consistent with the quantification of cloud susceptibility in satellite observations, the pixel level model outputs are smoothed to 25 km resolution and Nd–LWP relations are quantified as ) using the smoothed data.

To directly compare the WRF simulations with ground-based observations, we used the Cloud Resolving Model Radar Simulator (CR-SIM; Oue et al., 2020). It is a forward-modeling framework which uses consistent microphysics assumptions as in the atmospheric model (i.e., the two-moment Morrison scheme in this study) and emulates radar and lidar observables. Some common radar and lidar variables include: the radar reflectivity factor at horizontal and vertical polarization, depolarization ratio, Doppler velocity, spectrum width, lidar backscatter, attenuated backscatter, lidar extinction coefficient, and so on. In this study, we analyzed the simulated radar reflectivity factor to characterize cloud and precipitation properties.

To distinguish different precipitation modes and the microphysical growth processes that transition clouds from non-precipitating to drizzling and raining, we investigate the vertical transition from cloud to precipitation using the Contoured Frequency of Optical Depth Diagram (CFODD) method (Suzuki et al., 2010) from both observations and model simulations. The CFODD analysis calculates the frequency of radar reflectivity profiles as a function of in-cloud optical depth (τd), where τd is calculated based on an adiabatic-condensation growth model and it starts at zero at cloud top and increases downward. One benefit of the CFODD analysis is that the slope of reflectivity directly relates to the droplet collection efficiency, where the slope of reflectivity in the common geometric height depends on cloud water content (Suzuki et al., 2010).

2.3 Case studies

With the focus of MBL clouds in this study, cases are selected when both satellite and ground-based observations define MBL clouds in the ENA region. For cloud type classification in ground-based observations, we used the same method as in Zheng et al. (2025), where clouds are classified into seven types based on the boundaries and duration of each cloud object. In this study, we include both cumulus and stratocumulus clouds. Days are excluded when only shallow cumulus clouds are detected to filter out clouds that are below the detectable resolution of the Meteosat observations and to minimize uncertainties in the cloud microphysical retrievals from the ground-based observations. We further exclude days with more than three layers of cloud in the boundary layer to minimize uncertainty in cloud retrievals. Classification of cloud type in Meteosat observations uses a similar method as the ground-based observations. Cloud objects are defined as connected cloudy pixels, where low clouds are defined as clouds with 90th percentile of cloud top height below 3km. Low clouds are further classified as stratiform clouds and cumulus or broken stratiform clouds using an area threshold of 10 000 km2 (Qiu and Williams, 2020).

We focus on summer months (June, July, August) in the ENA region, when this region is often dominated by the Bermuda high-pressure systems and MBL clouds have the highest occurrence frequency (e.g., Li et al., 2011; Mechem et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2014, 2023). Previous studies found that the ARM measurements at the ENA site – located near the northern shore of the Graciosa Island, the northernmost island in the Azores archipelago – can be influenced by local emissions and island effects during southerly wind conditions. These impacts include modification to the aerosol and CCN concentrations, boundary layer turbulence, and the cloud field (e.g., Ghate et al., 2021, 2023). To minimize these influences, we focus on the three synoptic regimes identified in Zheng et al. (2025) when the ENA site is influenced by northerly surface wind: the high-ridge regime (characterized by a mid-tropospheric ridge and surface high-pressure system), the post-trough regime, and the weak trough regime (Table S1, Fig. S1).

With the case selection criteria discussed above, there are a total 11 cases for the WRF simulations, covering different cloud states and synoptic conditions. The general characteristics of the 11 cases are listed in Table S1 in the Supplement. The synoptic pattern for each case from ERA5 is shown in Fig. S1 in the Supplement, the cloud fields observed from Meteosat are shown in Fig. S2. WRF simulated cloud fields in the N=100 and N=1000 experiments are shown in Figs. S3, S4. To better illustrate the large-scale cloud organization and compared with Meteosat observations, the simulated LWP in domain 2 are shown. As seen in Figs. S2–S4, our WRF simulations well capture the frontal systems and synoptic pattern of cloud fields across different cases.

3.1 Case study: Impacts of aerosols on PBL thermodynamics and cloud evolution

Previous studies have demonstrated distinct cloud responses to aerosol perturbations between precipitating and non-precipitating regimes in both model simulations and observations (e.g., Chen et al., 2014; Sato et al., 2018; Gryspeerdt et al., 2019; Fons et al., 2024; Qiu et al., 2024). To explore these differences, we analyze two representative cases in our simulations: one dominated by precipitating clouds and another by non-precipitating clouds, to illustrate the distinct interactions among aerosols, clouds, and PBL thermodynamics in the presence and absence of precipitation.

Figure 1Time series of domain-averaged cloud properties from satellite observations and model simulations on 21 July 2016. (a) Cloud coverage, (b) cloud top height, (c) cloud liquid water path, and (d) rain-water path for N=100 (blue lines) and N=1000 (orange lines) experiments.

On 21 July 2016, the ENA site was dominated by precipitating stratocumulus clouds from 00:00 to 13:00 UTC, as seen from radar reflectivity profiles in Fig. S5b. The clouds dissipated from 12:00 to 18:00 UTC and redeveloped after 18:00 UTC (Fig. 1a, black line). The sounding observations show a moist and well-mixed boundary layer, with relative humidity (RH) near saturation above cloud top (Fig. S6). Our simulation captures the structure of the boundary layer, with a moist layer above the cloud, and the cloud-top RH close to sounding observations (99 % and 96 %, Fig. S6c). Due to biases in the ERA5 reanalysis in representing the temperature inversion, the boundary layer top in the model is approximately 500 m lower than in sounding data (Fig. S6). Consequently, the simulated cloud tops are 300–500 m lower than both satellite and ground-based radar observations (Figs. 1b, S6).

In the N=100 simulation, the WRF model reproduces overcast and precipitating stratocumulus clouds, with a domain-mean cloud cover varying between 0.90 to 0.94 from 00:00–13:00 UTC, which is slightly below than the Meteosat estimate of 0.97–1.0 (Fig. 1a, blue and black lines). However, unlike observations, the simulated clouds do not dissipate after 14:00 UTC; both cloud cover and LWP remain nearly constant throughout the day (Fig. 1a, d, blue lines). With increased aerosol concentration (N=1000), the simulated precipitation is suppressed (Fig. 1e), and the cloud layer remains overcast while deepening, accompanied by rising cloud tops and increasing LWP (Fig. 1b, c, orange lines). This cloud response arises from aerosol-induced precipitation suppression and the corresponding changes in boundary layer processes, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) is calculated as , with a unit of m2 s−2, and buoyancy flux is calculated as , with a unit of m2 s−3.

Figure 2Time series of domain-averaged thermodynamic profiles on 21 July 2016, for (a) relative humidity, (b) turbulent kinetic energy (TKE; m2 s−2), (c) buoyancy flux (m2 s−3) in the N=100 simulation, and (d) changes in relative humidity, (e) changes in TKE, (f) changes in buoyancy flux between the N=100 and N=1000 simulations. The black contours show cloud water mixing ratio (g kg−1) in (a)–(c) for N=100 and in (d)–(f) for N=1000 simulations.

In the simulations, increases in aerosol concentrations lead to higher Nd and smaller drop size. As the two-moment Morrison scheme does not consider the cloud drop size in the parameterization of evaporation, aerosol impacts on clouds and boundary layer occur through the influence of precipitation on PBL structure. Specifically, aerosols suppress precipitation by reducing autoconversion with increasing Nd, decreasing sedimentation rate and terminal velocity from smaller droplets. The formation of drizzle release latent heat and reduce both entrainment and the production of turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) by buoyancy; while the evaporation of drizzle below cloud cool and moisten the sub-cloud layer that decrease buoyancy and TKE (Stevens et al., 1998). As a result, the reduced precipitation increases both TKE and buoyancy flux in the cloud layer and below cloud (Fig. 2e, f). The enhanced turbulence and buoyancy support vertical development of clouds, raising cloud tops and expanding the cloud layer upward (Figs. 1b and 2), while also increasing RH near the cloud top (Fig. 2d).

Figure 3Time series of domain-averaged cloud properties from observations and model simulations on 22 July 2016. (a) Cloud coverage, (b) cloud top height, (c) cloud liquid water path, and (d) rain-water path for N=100 (blue lines) and N=1000 (orange lines) experiments.

On the second day (22 July 2016), the precipitating stratocumulus clouds transition into non-precipitating thin stratus over the ENA site (Fig. S7). The clouds were predominately overcast from 00:00–09:00 UTC and dissipated after 10:00 UTC, with the domain-mean cloud coverage decreasing from 0.8–0.9 to 0.1–0.2 (Fig. 3a, black line). As shown in Fig. S8, the boundary layer was moist and well-mixed, capped by a sharp temperature inversion, and moisture decreases rapidly above the inversion. The WRF model reproduces the general thermodynamic structure, including the inversion and moisture decline above the PBL. However, due to biases in ERA5 thermodynamic profiles, the simulated PBL top is about 700 m lower than observed (Fig. S8). Additionally, WRF model fails to capture the rapid decrease of moisture above cloud top, resulting in a more humid layer above cloud with cloud-top RH of 87 % in the model, compared to 62 % in sounding observation (Fig. S8c).

In the N=100 simulation, the simulated stratocumulus cloud generates light precipitation from 00:00–06:00 UTC, then it transitions to a non-precipitating thin cloud layer after 06:00 UTC (Fig. 3d, blue line). However, the cloud does not dissipate in the model. Domain-mean cloud cover remains between 0.85 and 0.95 throughout the day, and the simulated LWP is nearly twice that retrieved from Meteosat (Fig. 3a and c, blue lines). When aerosol concentrations are increased to N=1000, clouds dissipate from 14:00–20:00 UTC, with a decreasing domain-mean cloud cover and become more consistent with observations (Fig. 3a, orange line). Meanwhile, cloud tops rise slightly with increasing aerosol. The cloud dissipation reflects a net effect of aerosol induced changes in condensation, evaporation, turbulence, and buoyancy, as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4Time series of domain-averaged thermodynamic profiles on 22 July 2016, for (a) relative humidity, (b) turbulent kinetic energy (TKE; m2 s−2), (c) buoyancy flux (m2 s−3) in the N=100 simulation, and (d) changes in relative humidity, (e) changes in TKE, (f) changes in buoyancy flux between the N=100 and N=1000 simulations. The black contours show cloud water mixing ratio (g kg−1) in (a)–(c) for N=100 and in (d)–(f) for N=1000 simulations.

During the early phase (00:00–06:00 UTC), increased aerosol loading suppresses drizzle, leading to an increase in LWP and a decrease in RWP (Fig. 3c, d). Similar to the first case, the suppressed precipitation enhances turbulence and increases TKE in and below cloud (Fig. 4e), lifts the cloud top, and leads to an increase in RH near cloud top (Fig. 4d). Meanwhile, the free tropospheric air above cloud top is relatively drier compared to the first case (Fig. 4a). The increased turbulence and raised cloud top entrain dry air into the cloud and enhance evaporation. After 06:00 UTC, as clouds become non-precipitating in the N=100 experiment, the decrease of cloud water from evaporation starts to dominate the increase from precipitation suppression and lead to a net decrease in LWP. Reduced buoyancy weakens the upward transport of moisture and energy from the sub-cloud layer, further contributing to cloud dissipation. As a result, both cloud cover and LWP decrease with increasing aerosol (Fig. 3a, c).

The absence of afternoon cloud dissipation in WRF simulations are likely associated with model biases in the thermodynamic structure inherited from ERA5. For example, on 21 July 2016, ARM sounding observations show a pronounced decrease in specific humidity and relative humidity above the PBL between 14:00 and 20:00 UTC (figures not shown). This sharp drying leads to cloud erosion in the observations. However, WRF simulations or ERA5 reanalysis produces only a gradual reduction in moisture from 00:00 to 20:00 UTC (Fig. 2a), maintaining a moist layer above cloud top and preventing cloud breakup. On 22 July 2016, the model reproduces the moisture gradient above PBL with a warm and dry layer above, the lifted cloud top in the N=1000 simulation entrain dry air into cloud system and dissipate clouds in the afternoon (Fig. 3a). On days when ERA5 accurately capture the observed moisture decrease above PBL (e.g., 25 and 28 July 2016), the model reproduces both the dissipation and evening redevelopment of clouds seen in Meteosat data (figures not shown). This indicates that the diurnal evolution of MBL clouds is highly sensitive to the representation of diurnal variation in moisture as well as the moisture gradients near the inversion.

The prescribed, vertically uniform aerosol concentration further reinforces cloud persistence by maintaining elevated CCN levels and suppressing drizzle formation. The lack of precipitation scavenging prevents cloud-base evaporative cooling and inhibits decoupling, both of which would otherwise promote afternoon cloud breakup. The implications of thermodynamic biases (e.g. the moist layer above cloud top and the underestimated PBL height) for the estimated ACI are discussed in detail in Sect. 3.3.2.

In a nutshell, precipitating and non-precipitating clouds react differently to aerosol perturbations in our simulations. For precipitating clouds, aerosols increase LWP through precipitation suppression and support vertical development of cloud through the impact of precipitation on PBL dynamic and thermodynamics. For the non-precipitating case, PBL air is drier compared to the first case, the enhanced turbulence and entrainment of dry air above leads to evaporation and reduced buoyancy. The reduced buoyancy stabilizes PBL and decays the cloud layer.

3.2 Evaluation of LWP susceptibilities across cloud states and synoptic conditions

The two cases in Sect. 3.1 demonstrate the impact of different cloud states and PBL thermodynamics on cloud responses to aerosol perturbations. To systematically evaluate ACI process across all simulated cloud states, we composite the cloud fields from all 11 cases and all three aerosol concentrations (e.g. N=1000 vs. N=100, N=500 vs. N=100, and N=1000 vs. N=500) to estimate the mean LWP response, and compare it with satellite retrievals, as shown in Fig. 5. More specifically, LWP susceptibility in WRF simulations is defined as the change in domain mean cloud properties as ) between polluted and clean simulations for each 10 min model output. To be consistent with satellite retrievals, we focus on daytime with solar zenith angle less than 65°. Lastly, we use the LWP-Nd parameter space to represent different cloud states. (Qiu et al., 2024).

Figure 5Mean liquid water path (LWP) susceptibility from (a, b) WRF simulations and (c, d) Meteosat cloud retrievals during daytime. Panels (a) and (c) show cloud LWP susceptibility, defined as ), panels (b) and (d) show the frequency of occurrence in each bin. Dashed lines in each panel indicate thresholds of re=15 µm, re=10 µm for precipitation, and LWP = 75 g m−2 for thick clouds. Precipitating clouds are located to the left of the re=15 µm line, and thick clouds are defined as LWP >75 g m−2. Black-outlined bins denote cases where the WRF and Meteosat LWP susceptibilities differ significantly (p<0.05) based on a Welch's t test.

Based on the relationships between re, LWP, and Nd in the satellite retrievals (e.g., , ), re=15 µm isoline is marked in the LWP-Nd parameter space as an commonly used indicator of precipitation likelihood in the satellite retrieval (e.g., Gryspeerdt et al., 2019; Toll et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2024). Based on the distinct LWP, cloud albedo and CF susceptibilities between cloud states, MBL clouds are classified into three states: precipitating clouds (re>15 µm), non-precipitating thick clouds (re<15 µm, LWP >75 g m−2), and non-precipitating thin clouds (re<15 µm, LWP <75 g m−2) (Qiu et al., 2024). To remain consistency with observational reference, the WRF-simulated cloud states are classified using the same definition. Similar to warm MBL clouds in observations (e.g. Qiu et al., 2024), LWP responses to aerosol perturbations in model simulations show a clear dependence on cloud state (Fig. 5a).

For precipitating clouds (re>15 µm), LWP slightly increases with Nd, with a mean susceptibility of + 0.15. The increase of LWP agrees with the precipitation suppression mechanism. Meanwhile, there are only 4 % of clouds in model simulations locate to the left of the re=15 µm isotherm with small Nd, even with aerosol concentration set to 100 cm−3 (Fig. 5b). The non-precipitating thick clouds (re<15 µm, LWP >75 g m−2) are the dominant cloud state in model simulation, accounting for 49 % of total cloud occurrence. In contrast to the evaporation-entrainment feedback mechanism, LWP increases substantially in the model with increasing aerosols, with a mean susceptibility of + 0.32. For non-precipitating thin clouds (re<15 µm, LWP <75 g m−2), LWP decreases with aerosol perturbations with a mean susceptibility of − 0.14, consistent with the second case discussed in Sect. 3.1.

To evaluate model performance, we estimated LWP susceptibility from satellite retrievals within the same domain and for the same 11 cases as the model simulations (Fig. 5c and d). Specifically, LWP susceptibility was quantified as the regression slope between LWP and Nd within the 1° × 1° domain at each time step of satellite observations. For precipitating clouds, LWP slightly decreases with increasing Nd in satellite data, consistent with the four-year climatological mean feature in the ENA region reported in our previous study (Qiu et al., 2024). This decrease of LWP with increasing Nd is likely associated with the depletion of LWP through sedimentation–evaporation–entrainment feedbacks, which outweigh the increase of LWP from precipitation suppression. In contrast, in model simulations, the lack of realistic evaporation-entrainment feedback results in LWP increasing primarily through precipitation suppression. The simulated LWP susceptibilities are significantly different with satellite observations at the 95 % confidence level for most precipitating clouds (Fig. 5a).

For non-precipitating thin clouds, the simulated decrease in LWP with increasing aerosol concentration agrees in sign with satellite observations. However, the magnitude of this decrease is weaker, and the simulated susceptibilities remain significantly different from satellite estimates at the 95 % confidence level for most bins (Fig. 5a, c). This model behavior contrasts with most GCM and coarse CPM studies, which typically simulate LWP increases for non-precipitating clouds (e.g., Fons et al., 2024; Christensen et al, 2024; Mülmenstädt et al., 2024). The improved representation in our high-resolution simulations arise from better-resolved PBL turbulence and thermodynamics, which enhance entrainment of dry air, accelerate evaporation, reduce buoyancy, and promote dissipation of the cloud system.

In contrast, for non-precipitating thick clouds, the model and observations diverge substantially. In satellite observations, LWP decreases most strongly for this cloud state, with a mean LWP susceptibility of − 0.69 (Fig. 5c). This observational estimate is consistent with the climatological mean derived from four years of Meteosat data over the ENA region (Qiu et al., 2024). In the model, however, LWP increases most strongly with increasing Nd for this cloud state. Moreover, compared with satellite retrievals, model simulates a substantially larger population of polluted thick clouds characterized by high Nd and LWP. For example, non-precipitating thick clouds are the dominant cloud state in the model, accounting for 49 % of total cloud occurrence (Fig. 5b), whereas they are the least frequent in observations, at only 15.7 % (Fig. 5d). Meanwhile, only 4 % of simulated clouds fall into the precipitating cloud regime with Nd<50, compared with 22.2 % in satellite observations

The overall overestimation of Nd likely arises from the prescribed aerosol concentration in the model configuration, combined with the absence of precipitation scavenging. For reference, the mean aerosol concentration over the ENA region during summer is approximately 400 cm−3 (e.g., Zhang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2024). The model's overestimation of LWP may stem from its excessively positive LWP susceptibility in thick clouds. As shown in Fig. S9, simulated LWP in the N=100 experiment agrees reasonably well with the Meteosat retrievals, with a mean value about 10 % lower than observed. However, in the N=500 and N=1000 simulations, the strong positive LWP susceptibility leads to increases in LWP for clouds with LWP >75 g m−2, resulting in mean values 30 % and 40 % higher than Meteosat retrievals, respectively.

To further examine whether these discrepancies depend on large-scale meteorological conditions, we assessed LWP susceptibility across different synoptic regimes. Because only one case is available for the “weak-trough” regime (Table S1), our comparison focuses on the “high-ridge” and the “post-trough” regimes (Fig. S10). The “high-ridge” regime shows a higher occurrence of non-precipitating thin clouds than the “post-trough” regime, with total frequencies of 49 % and 40 %, respectively (Fig. S10b, d). This more frequent non-precipitating thin cloud in the model is consistent with our previous study based on six years of ground-based observations at the ARM ENA site, which revealed that the “high-ridge” regime favors single-layer stratocumulus clouds with shallower cloud depth and smaller LWP compared to the “post-trough” regime (Zheng et al., 2025).

In addition, non-precipitating thin clouds in the “high-ridge” regime exhibit more negative LWP susceptibilities than clouds with similar LWP and Nd in the “post-trough” regime. This difference in LWP susceptibility is associated with the colder and drier air above clouds under subsidence in the “high-ridge” regime, which facilitates cloud dissipation, as also demonstrated in the case study. Furthermore, non-precipitating or lightly drizzling thick clouds in both synoptic regimes manifest strong positive LWP susceptibilities, suggesting that the model-observation discrepancy for this cloud state persist regardless of synoptic conditions and therefore warrants further investigation.

In summary, mean LWP susceptibility from our simulations were evaluated against satellite retrievals in the LWP-Nd parameter space across different cloud states and synoptic conditions for a comprehensive comparison. The simulations reproduce the observed decrease in LWP for non-precipitating thin clouds, although with weaker magnitudes. For precipitating clouds, the model predicts a slight increase in LWP instead of the weak decrease seen in satellite observations, reflecting the limited representation of evaporation-entrainment feedback in the model. Large discrepancies remain for non-precipitating or lightly drizzling thick clouds, where the model simulates too many polluted thick clouds and yields an opposite (positive) LWP response compared to the strongly negative satellite signal.

In addition, these discrepancies persist across all synoptic regimes, suggesting that they originate from the model's representation of cloud microphysics, precipitation, and aerosol-cloud coupling rather than from large-scale meteorological variability. The consistency of these modeled LWP response, in agreement with previous LES studies of similar cloud regimes (e.g., Wang et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2025), further motivates the central focus of the next section: diagnosing the physical mechanisms driving these biases. We show that three leading factors dominate the discrepancy: excessive precipitation production in thick clouds, a moist bias above cloud top, and contamination of satellite retrieved Nd–LWP relationships by internal cloud processes.

3.3 Causes of satellite–model discrepancies in LWP susceptibility

The satellite–model differences highlighted above point to systematic biases in how the model represents cloud microphysics, precipitation processes, and entrainment pathways. In this section, we diagnose the physical mechanisms driving these discrepancies, beginning with the model's precipitation efficiency.

Figure 6Mean cloud properties from (a, b) Meteosat retrievals and (c, d) WRF simulations during the daytime. (a, c) Effective radius, (b, d) pixel-level precipitation fraction. The dashed lines indicate re=15 µm, re=10 µm, and LWP = 75 g m−2, as re thresholds for precipitation (precipitating clouds located to the left of the line), and for thick clouds (with LWP >75 g m−2), respectively.

3.3.1 Precipitation efficiency

A long-standing challenge in numerical models is the tendency to produce precipitation too frequently and too lightly (Sun et al., 2006; Stephens et al., 2010). To assess the modeled precipitation efficiency against observations, Fig. 6 shows the mean cloud properties from Meteosat observations and from WRF simulations for the 11 cases, combining all three aerosol concentrations (N=100, 500, and 1000). As satellite retrieves re near cloud top, we use re at ∼100 m below cloud top in the simulations, which approximately corresponds to τ≈2 from cloud top for marine stratocumulus. The modeled pixel-level precipitation fraction is calculated as the area fraction of cloudy pixels with the column maximum radar reflectivity (Zmax) greater than −15 dBZ at each model output time (Haynes et al., 2009; Suzuki et al., 2015; Jing et al., 2017). Modeled radar reflectivity is from the radar simulator (CR-SIM), as discussed in the methodology. The precipitation fraction in Meteosat is calculated as the area fraction of clouds with re>15 µm. Qiu et al. (2024) evaluated different effective radius thresholds and rain rate thresholds in satellite retrievals using precipitation masks derived from ground-based radar reflectivity at the ENA site, and concluded that the re>15 µm threshold showed the best agreement with observations.

As shown in Fig. 6a, c, the modeled re is ∼1–3 µm smaller than satellite retrievals for a similar cloud condition. Additionally, compared to observation, the model produces precipitation too frequently at smaller drop size (re>10 µm) and at higher Nd concentration (Fig. 6b and d, re=10 µm dashed line). The large discrepancy in LWP susceptibility for thick clouds between the 10 and 15 µm isolines is likely linked to model bias in precipitation efficiency. To further investigate the model bias of excessive rain at smaller drop size and the positive LWP responses to aerosol perturbations, we compared the modeled radar reflectivity profiles from the radar simulator with ARM observations using the CFODD framework. Based on the relationship between Ze and the droplet collection efficiency (Ec), the vertical slope of Ze as a function of in-cloud optical depth (τd) is directly linked to Ec, a steeper slope indicates a larger Ec (Suzuki et al., 2010).

Ground-based radar reflectivity profiles and cloud retrievals at the ARM ENA site are used as the observational reference. To reduce noise, radar reflectivity profiles and cloud boundary data are smoothed to a 1 min resolution. To increase the sample size, we analyzed summer (June–August) climate-mean radar reflectivity profiles for stratocumulus and cumulus clouds observed from 2016 to 2021, comprising a total of 91 737 profiles. Radar reflectivity profiles derived from the selected 11 cases exhibit consistent characteristics (figure not shown).

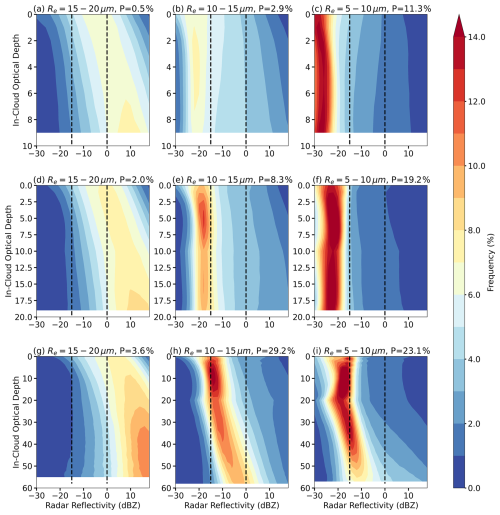

To better distinguish microphysical processes such as autoconversion and accretion from dynamical processes such as updraft, clouds are further categorized by both re and τ ranges. MBL clouds are classified as non-precipitating clouds, drizzle, and rain using a reflectivity threshold of dBZ, −15 dBZ dBZ, and Ze>0 dBZ, respectively, as denoted by black dashed lines in Fig. 7 (Haynes et al., 2009; Suzuki et al., 2015; Jing et al., 2017).

Applying the same cloud state classification as in the satellite observations (e.g., re>15 µm for precipitating clouds and LWP >75 g m−2 for thick clouds), the total frequency of occurrence of precipitating, non-precipitating thin, and non-precipitating thick clouds are 30.7 %, 46.3 %, and 23.0 %, respectively, based on six years of ARM observations. These frequencies are consistent with those derived from satellite data for the 11 cases (22.2 %, 55.6 %, and 22.2 %, respectively; Fig. 5d). Therefore, the selected cases are representative of the typical summer MBL cloud-type distribution in the ENA region.

As shown in the first column of Fig. 7, in clean environment with re>15 µm, the observed MBL clouds start to drizzle with dBZ even in the thinnest category (Fig. 7a), of which the cloud top is mostly non-precipitating ( dBZ). Cloud drops rapidly grow from cloud top downward and initiate drizzle at ∼4–6 optical depth into the cloud. However, most observed MBL clouds, even for the thickest category (Fig. 7g), remain drizzling rather than raining as most of the radar reflectivity is lower than 0 dBZ.

Figure 7Frequency of radar reflectivity as a function of in-cloud optical depth (τd) for ARM ground-based observations during the daytime. Different rows correspond to different optical depth (τ) ranges: (a–c) τ<10, (d–f) , (g–i) τ>20. Different columns correspond to effective radius (re) ranges: 15–20 µm (left), 10–15 µm (middle), and 5–10 µm (right). The black dashed lines denote −15 and 0 dBZ, thresholds for drizzle and rain, respectively. The percentage of sample (P) in each subgroup is shown in each panel; the total sample size is 91 737.

Figure 7b, e, and h represent clouds with observed re=10–15 µm, indicating increased Nd relative to clouds of similar τ with re>15 µm (Fig. 7a, d, and g). Precipitation in these clouds is suppressed: Ze is mostly below −15 dBZ in thin clouds (τ<10, Fig. 7b). Thick clouds produce drizzle at approximately τd>20, and Ze slightly decrease at cloud base, likely due to mixing and evaporation (Fig. 7h).

When re decreases to below 10 µm (Fig. 7c, f, and i), Ze further reduces to around −20 to −30 dBZ throughout the cloud layer, indicating that precipitation is further suppressed. The precipitation suppression effect is shown not only by the peak frequency of Ze, but also the slope of Ze, which indicates the droplet collection efficiency as discussed above. As seen in Fig. 7, for clouds with similar thickness, the slope of Ze decreases with decreasing re, which reflects a weaker collision coalescence and accretion processes with higher Nd and smaller cloud drops.

In thick clouds with re<10 µm (Fig. 7i), most radar reflectivity remains below −25 dBZ in the lower cloud layer, while reflectivity increases slightly toward cloud top in the region corresponding to ∼10–20 optical depth into the cloud. Reflectivity then decreases again toward cloud top. This vertical pattern is consistent with the structure of marine clouds reported in Suzuki et al. (2010). The observed decrease in reflectivity near cloud top may be attributed to entrainment and evaporation, or to the accretion process involving large droplets falling downward, as indicated by localized reflectivity peaks exceeding −15 dBZ (Fig. 7i). Meanwhile, observations suggest that for clouds with small droplet sizes, cloud deepening and dynamical variability have limited influence on precipitation initiation.

Figure 8Frequency of radar reflectivity as a function of in-cloud optical depth (τd) for WRF N=100 simulation. Different rows correspond to different optical depth (τ) ranges: (a–c) τ<10, (d–f) , (g–i) τ>20. Different columns correspond to effective radius (re) ranges: 15–20 µm (left), 10–15 µm (middle), and 5–10 µm (right). The black dashed lines denote −15 and 0 dBZ, thresholds for drizzle and rain, respectively. The percentage of sample (P) in each subgroup is shown in each panel.

Compared with the observational reference (“ground truth”), the model simulations reasonably identify the non-precipitating regime in clouds with re<10 µm and τ<20, where cloud drops are too small for efficient collision-coalescence (Fig. 8c and f). Additionally, drizzle initiates at the same re and τ ranges as in observations: for example, the maximum frequency of Ze exceeds −15 dBZ in thin clouds with re>15 µm and τ<10 (Fig. 8a) or in thick clouds with re=10–15 µm and τ=10–20 (Fig. 8e). This result contrast with GCM or GCPM results, in which models often simulate few non-precipitating clouds, or initiate drizzle too early within the cloud layer (e.g. 5–10 optical depths; Jing et al., 2017, 2019; Michibata and Suzuki, 2020). The improved representation of non-precipitating clouds and the transition from non-precipitating clouds to drizzle process in our simulations highlights the importance of high model resolution for realistically simulating precipitation processes.

On the other hand, the model overestimates precipitation in both intensity and frequency in optically thick clouds with τ>20. The simulations produce rain with peak Ze exceeding 0 dBZ across all droplet size ranges, even for clouds with re<10 µm (Fig. 8g–i). Furthermore, precipitation initiates too early near cloud top: all precipitating clouds in the model start to drizzle or even rain at cloud top (Fig. 8a, d, e, g, h, i). Based on the features shown in the CFODD analysis, the overestimation of precipitation could be attributed to the following four aspects in the parameterization.

First, the overestimation of reflectivity near cloud top indicates that autoconversion is activated too early in clouds near the top. For a given aerosol concentration, clouds with lower activated Nd exhibit larger re (Fig. 6c). As the autoconversion rate scaled nonlinearly with Nd (e.g. ), clouds with larger droplets (e.g. ∼15–20 µm) have smaller Nd, and therefore exhibit larger autoconversion rate.

Second, the elevated reflectivity near cloud top may reflect an underestimation of entrainment rate or evaporation rate from the moist layer above the cloud. As shown in Fig. 8, the simulated Ze does not decrease towards cloud top or cloud base as in the observations, indicating insufficient entrainment and evaporation.

Third, excessive rain production indicates an overestimation of the accretion process. In the Morrison scheme, accretion depends on both cloud water and rainwater content; thus, when autoconversion is triggered too early, accretion also initiates too early. This bias is amplified in thick clouds, which have larger liquid water content and provide longer path for droplet collection (Fig. 8g–i). For thick clouds with small drop size (Fig. 8i), they remain non-precipitating near cloud top, indicating that autoconversion is appropriately suppressed by small drop size. However, these clouds still produce rain, suggesting excessive accretion.

Lastly, excessive rain production in thick clouds also suggest an overly broad parameterized drop size distribution (DSD), which lead to an early initiation of autoconversion at cloud top and rain formation in clouds with large re.

Overall, in N=100 simulation (Fig. 8), most modeled MBL clouds are optically thin (τ<20) and exhibit medium (re=10–15 µm, 49.8 %) or large droplet sizes (re=15–20 µm, 25.8 %). In contrast, observations show that the majority of clouds have re<10 µm (53.3 %) (Fig. 7, third column). Meanwhile, although the aerosol concentrations are prescribed, the model predicts Nd through aerosol activation and microphysical processes, resulting in variabilities in Nd. For clouds of a given optical depth, decreasing re corresponds to increasing Nd. This increase in Nd is associated with both lower peak of Ze and a reduced vertical Ze gradients in the CFODD, suggesting aerosol-induced precipitation suppression. Lastly, cloud dynamics exhibits a stronger influence in the simulations than in observations. For example, thicker clouds in the model show higher peak Ze values and broader Ze distribution than thinner clouds with the same re, whereas this enhancement is less evident in ARM observations.

Figure 9Frequency of radar reflectivity as a function of in-cloud optical depth (τd) for WRF N=500 simulation. Different rows correspond to different optical depth (τ) ranges: (a–c) τ<10, (d–f) , (g–i) τ>20. Different columns correspond to effective radius (re) ranges: 15–20 µm (left), 10–15 µm (middle), and 5–10 µm (right). The black dashed lines denote −15 and 0 dBZ, thresholds for drizzle and rain, respectively. The percentage of sample (P) in each subgroup is shown in each panel.

By comparing simulations with different prescribed aerosol concentrations, we observe that with increasing aerosols and decreasing drop size, precipitation is suppressed. This suppression is evidenced by a shift in the frequency of precipitating clouds, along with reduced peak Ze values and shallower vertical gradient of Ze. For example, the most common cloud type shifts from thin clouds with moderate re in the N=100 simulation (Fig. 8b and e) to thicker clouds with smaller re in the N=500 run (Fig. 9h and i), revealing a typical cloud response to precipitation suppression. Meanwhile, the percentage of clouds with re=15–20 µm decreases substantially from 31.9 % in N=100 simulation to 6.1 % in N=500 simulation. As a result, the droplet size distribution in N=500 simulation aligns more closely with ARM observations, although the simulated clouds remain optically thicker than observed. For clouds with similar re and τ, both the peak Ze and its vertical gradient decrease with increasing aerosol concentrations due to the reduced autoconversion with higher Nd. In particular, thick clouds with medium re (re=10–15 µm, τ>20, Fig. 9h) transition from raining to drizzling in the N=500 simulation, aligning more closely with observations.

For clouds with re>15 µm, rain becomes stronger compared to the N=100 simulation, even in the thinnest cloud (Fig. 9a, d, and g vs. Fig. 8a, d, and g). While the enhancement of precipitation with increasing aerosol concentration may initially seem counter-intuitive, it can be explained by the parameterization of DSD in the model. For clouds with similar τ, increasing re is associated with higher LWP and qc, but lower Nd. Based on Eq. (5), the slope parameter λ decreases with increasing re, resulting in a broader DSD with a flatter slope. Additionally, the dispersion parameter η is proportional to Nd so that polluted clouds in N=500 simulation also exhibit broader DSDs. As a result, even under suppressed autoconversion due to higher Nd, the extended tail of the broader DSD initiates autoconversion, enhances accretion from higher fall speed, and ultimately enhances precipitation in the N=500 simulation. Note that this type of cloud occurs much less frequently in the N=500 simulation (6.1 %) than in the N=100 simulation (31.9 %).

Figure 10Frequency of radar reflectivity as a function of in-cloud optical depth (τd) for WRF N=1000 simulation. Different rows correspond to different optical depth (τ) ranges: (a–c) τ<10, (d–f) , (g–i) τ>20. Different columns correspond to effective radius (re) ranges: 15–20 µm (left), 10–15 µm (middle), and 5–10 µm (right). The black dashed lines denote −15 and 0 dBZ, thresholds for drizzle and rain, respectively. The percentage of sample (P) in each subgroup is shown in each panel.

When aerosol concentration is further increased from N=500 to N=1000 (Fig. 9 versus Fig. 10), the CFODD of reflectivity changes little, indicating a saturation of precipitation suppression and DSD broadening. A larger fraction of clouds shifts into the non-precipitating thick-cloud subgroup with re<10 µm and τ>20 (44.6 %, Fig. 10i).

In summary, we evaluated the vertical development of precipitation in the model using ARM radar reflectivity profiles. Our simulations realistically reproduce the non-precipitating regime and the transition to drizzling clouds at similar re and τ ranges as ARM observations. Meanwhile, model overestimates precipitation for optically thick clouds and clouds with re>15 µm. This overestimation could be attributed to the early initiation of the autoconversion process, which leads to an early onset of rain near the cloud top. The excessive accretion rates, along with underestimation of entrainment and evaporation, lead to an overproduction of rain in the model, especially in thick clouds with larger water content and longer droplet collection path. Additionally, the parameterized DSD is too broad in the model, especially for polluted clouds with large Nd and large re.

Because the model reasonably captures the properties of non-precipitating thin clouds in agreement with ARM observations, the simulated LWP susceptibility aligns well with satellite-based estimates. In contrast, the overestimation of precipitation in thick clouds leads to a predominantly positive LWP susceptibility in the model due to the precipitation suppression effect. However, satellite observations indicate that these clouds are typically non-precipitating, where entrainment drying dominates, resulting in a negative LWP susceptibility. These results highlight the need to improve the parameterization of precipitation processes: particularly autoconversion, accretion, and DSD representation, in order to better simulate ACI across all cloud regimes.

While our analysis focuses on the two-moment Morrison scheme, Christensen et al. (2024) found that the choice of microphysics and PBL schemes accounts for only about 30 % of the variability in simulated ACI, much smaller than the variability across meteorological conditions and cloud states. Given that this study encompasses 11 cases spanning diverse synoptic regimes and cloud types, the overly positive LWP susceptibility for thick clouds is consistent across synoptic regimes, we therefore expect that the overall conclusions are not strongly sensitive to the specific choice of two-moment bulk microphysics schemes.

Moreover, the key deficiencies identified in this study (e.g. early initiation of autoconversion, excessive accretion, and too broad DSD) are well-known limitations within the framework of two-moment bulk microphysics scheme, rather than being unique to the Morrison formulation. As a result, the process-level diagnostics and physical interpretations presented here are broadly applicable. We acknowledge that explicit sensitivity tests using alternative microphysics schemes would further strengthen these conclusions. However, such experiments are computationally expensive at the near-LES resolution (∼200 m) employed here for a large ensemble of realistic cases. Nonetheless, future investigations using multiple microphysics schemes would be valuable for quantifying the robustness of the precipitation parameterization and its role in ACI uncertainty.

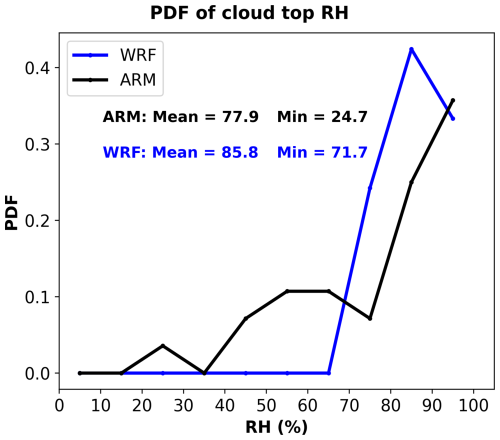

3.3.2 Model bias in capturing inversions

As discussed in the case study in Sect. 3.1, ERA5 profiles fail to accurately represent the location and strength of inversions over the ENA region. These biases lead to an underestimated boundary layer height and an overestimated RH above cloud top in the simulations. Figure 11 compares the probability density function (PDF) of cloud-top RH between ARM sounding observations and WRF simulations across all 11 cases for N=1000 simulation. Simulations with other aerosol concentrations (e.g., N=100, N=500) show similar results (not shown).

In ARM observations, cloud-top height is derived from radar reflectivity profiles, as described in the method section; whereas in WRF simulations, cloud top is defined as the highest model level where the cloud water mixing ratio exceeds 0.001 g kg−1. The RH is sampled at ∼100 m above cloud top in both datasets. We further compare the cloud-top heights in WRF simulations defined using cloud water mixing ratio and radar reflectivity profiles with dBZ from the radar simulator. The two approaches yield nearly identical results, with a mean difference of less than 40 m (figure not shown).

Figure 11PDF of cloud-top relative humidity (RH) for WRF simulations (blue line) and ARM sounding observations (black line).

To ensure a meaningful comparison between WRF output and ground-based observations, cloud-top RH from WRF is averaged over a 10 km × 10 km grid box centered at the ARM ENA site for each sounding time, given the ∼1.2–1.4 km mean cloud-top height for MBL clouds and ∼7 m s−1 prevailing wind speed at ENA during summer (Wood et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2020). As seen in Fig. 11, WRF simulations exhibit a systematic wet bias in cloud-top RH, with mean values 7.9 % higher than observations and with no RH values below 71 %.

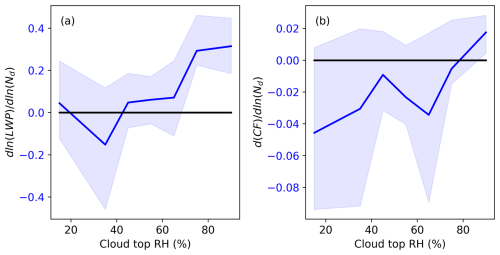

Figure 12 shows the mean relationship between clout-top RH and cloud susceptibilities calculated based on domain-mean values for all three simulations (N=1000 vs. N=100, N=500 vs. N=100, and N=1000 vs. N=500). Cloud-top RH is the domain-mean RH at ∼100 m above cloud top for each simulation. As seen in Fig. 12a, we find a positive correlation between cloud-top RH and LWP susceptibility in the simulations, consistent with case-study results in which a dry layer above cloud promotes evaporation and decreases LWP. Additionally, this positive relationship is robust across different aerosol concentrations (e.g., N=1000 vs. N=100 or N=500 vs. N=100; figures not shown). Moreover, cloud-top moisture exhibits a stronger impact on LWP susceptibility than CF susceptibility (Fig. 12). The relationships between cloud-top moisture and cloud susceptibilities identified in our simulations are consistent with that in satellite-based analyses on a global scale (e.g. Toll et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2023), except that LWP susceptibility is predominantly negative while CF susceptibility predominantly positive in satellite observations.

Figure 12Dependence of (a) LWP susceptibility and (b) CF susceptibility on cloud-top relative humidity in WRF simulations during daytime. The solid blue lines show the median value in each RH bin, and the shaded area indicates the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles).

Based on the relationship between cloud susceptibility and cloud-top RH, the over-estimated cloud-top RH of ∼8 % may lead to an overestimation of 0.04 and 0.005 in LWP and CF susceptibilities, respectively. Meanwhile, the under-estimated cloud-top height of 480 m could result in underestimations of LWP and CF susceptibilities of 0.18 and 0.02, respectively (figures not shown). These results suggest that improvements in the representation of thermodynamic profiles, such as through data assimilation, are necessary for future modeling studies over the ENA region.

To further illustrate the influence of cloud-top evaporation on LWP and CF adjustment rates, we analyzed the relationship between cloud susceptibilities and change in the cloud-layer buoyancy flux. As shown in the case study, buoyancy flux increases with aerosol perturbation in precipitating clouds due to precipitation suppression, whereas it decreases in non-precipitating clouds owing to enhanced entrainment-driven evaporation. Thus, changes in buoyancy flux serves as a proxy for both cloud-top evaporation and precipitation suppression processes.

Figure 13Dependence of (a) LWP susceptibility and (b) CF susceptibility on changes in buoyancy flux (unit: m2 s−3) in the cloud layer in WRF simulations during the daytime. The solid blue lines show the median value in each buoyancy flux bins and the shaded areaindicates the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles).

In Fig. 13, changes in cloud-layer buoyancy flux are calculated as differences in domain-mean values between polluted and clean experiments (e.g., N=1000 vs. N=100, N=500 vs. N=100, and N=1000 vs. N=500), averaged over the cloud layer defined by the domain-mean cloud water mixing ratio. As shown in Fig. 13, two distinct regimes emerge: when cloud-layer buoyancy flux substantially decrease with increasing aerosols, both LWP and CF decrease. When changes in buoyancy flux are weakly negative or positive, LWP and CF susceptibilities are generally positive or near zero. Together with the results shown in Fig. 12, these findings support the conclusion that the reductions in LWP and CF in the model are primarily driven by cloud-top evaporation associated with enhanced entrainment. The absence of negative LWP responses in earlier modeling studies may therefore be attributed to inadequate resolution of the coupled interactions among boundary layer turbulence, entrainment, and cloud-top evaporation.

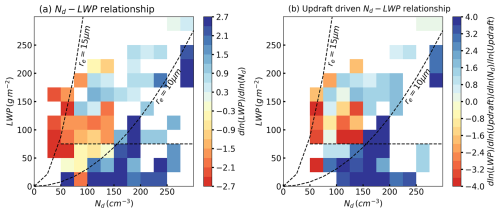

3.3.3 LWP adjustment from internal cloud processes and precipitation heterogeneity

In addition to model biases in representing precipitation processes and PBL thermodynamic profiles, one leading factor contributing to the discrepancy in ACI estimates lies in how ACI is diagnosed in numerical studies versus observations. In model simulations, ACI can be isolated using controlled experiments by varying aerosol concentrations while holding meteorology constant. In satellite-based analysis, however, the retrieved ACI signal inevitably includes not only aerosol-induced cloud responses but also Nd–LWP covariability arising from internal cloud processes, even under strict spatial and temporal sampling constraints. Diagnosing these internal cloud processes in satellite observations is difficult because key governing variables, such as cloud-base updraft speed, TKE, entrainment rate are not directly measured or retrieved. In contrast, model simulations allow us to quantify the Nd–LWP relationships driven by internal cloud processes by examining their spatial covariation under homogeneous aerosol conditions. To ensure consistency with satellite methodology and suppress small-scale cloud heterogeneity, pixel-level model outputs are aggregated to a 25 km × 25 km grid.

Figure 14(a) LWP-Nd relations stem from internal cloud processes (b) LWP-Nd relations driven by cloud base updraft speed in WRF simulations during the daytime.

Figure 14a shows the resulting Nd–LWP relationships across all cases and all aerosol concentrations, revealing opposing signs between different cloud regimes: a strong positive correlation for non-precipitating clouds and a strong negative correlation for precipitating clouds. To understand this contrast, we examine whether both Nd and LWP co-vary with a third parameter indicative of internal dynamics. Cloud-base updraft speed emerges as a physical meaningful driver: the ratio of to in Fig. 14b closely mirrors the Nd–LWP relations in Fig. 14a. This indicates that cloud base updraft speed largely governs the opposing responses. In non-precipitating clouds, stronger updrafts enhance supersaturation, activation, and condensation, increasing both Nd and LWP, and resulting in a positive Nd–LWP relationship. In precipitating clouds, stronger updrafts increase LWP and rain rate, but precipitation formation reduces Nd via coalescence and collection, leading to a negative relation.

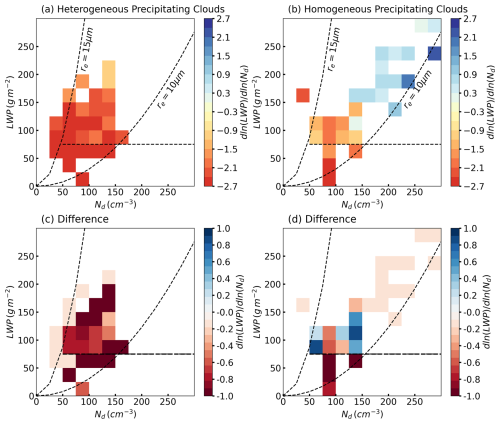

Furthermore, mesoscale variability in precipitation structure can further modulate the Nd–LWP relationship in precipitating clouds. To test this hypothesis, precipitating cases (domain-mean precipitation fraction >0.1) are further divided into heterogeneous and homogeneous categories based on the spatial standard deviation of precipitation fraction using the upper and lower 50th percentile, respectively (Fig. 15). Precipitation fraction is defined as the areal fraction of cloud pixels with the column maximum reflectivity greater than −15 dBZ (Fig. 6).

In heterogeneous convective precipitation (Fig. 15a), strong and spatially variable latent heating release enhances buoyancy within clouds, while rain evaporation and downdrafts generate cold pools. Both processes act to intensify updrafts, which in turn promote rapid droplet growth and increase the cloud's capacity to retain liquid water, leading to higher LWP and precipitation. Meanwhile, stronger coalescence and precipitation scavenging reduce Nd. Such opposite changes in LWP and Nd amplify the negative Nd–LWP relationship (Fig. 15c). In homogeneous stratiform precipitation, latent heating is more spatially uniform and stratification inhibits localized buoyancy-driven updrafts. Weaker coalescence and less efficient scavenging lead to a less negative Nd–LWP relationship (Fig. 15d).

Figure 15LWP-Nd relations stem from internal cloud processes for scenes with (a) heterogeneous and (b) homogeneous precipitating clouds. (c) and (d) show the difference between (a) and (b) with Fig. 14a.

In summary, even though clouds with LWP >75 g m−2 and re<15 µm are typically classified as non-precipitating thick clouds in observational ACI studies, pixel-level data real that 20 %–35 % of these clouds produce precipitation (Fig. 6a). The strongly negative LWP susceptibilities inferred from satellite data for non-precipitating thick clouds may partly arise from internal cloud processes driven by updraft speed and mesoscale precipitation structure, rather than from aerosol–cloud interactions alone. providing a plausible explanation for the model–observation discrepancy. Meanwhile, non-precipitating thin clouds with LWP <75 g m−2 and re<15 µm exhibit low pixel-level precipitation fractions (typically <0.1, Fig. 6a), and the positive Nd–LWP relationships arising from internal cloud processes may bias satellite-derived LWP susceptibility toward more positive values, further expanding the model-observation gap. The opposing signs of Nd–LWP relationships in Figs. 14a and 5c for non-precipitating thin clouds highlight the need for additional process-level analysis in future study.

Previous studies have found that model simulations and observations often reveal opposing results in LWP responses to aerosol perturbations for MBL clouds. For example, satellite-based assessments indicate a decrease in cloud LWP with aerosol perturbations, especially in polluted conditions for non-precipitating clouds (e.g., Gryspeerdt et al., 2019; Toll et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang and Feingold, 2023; Qiu et al., 2024; Yuan et al., 2023, 2024). On the other hand, most GCMs and CPMs simulate an increase in LWP with increasing aerosols (e.g., Ghan et al., 2016; Michibata et al., 2016; Mülmenstädt et al., 2024; Fons et al., 2024; Christensen et al, 2024). Previous studies have shown that increasing model resolution to sub-kilometer scales can improve the representation of precipitation processes and model performance in ACI by resolving small-scale processes most relevant to ACI (e.g., Terai et al., 2020). However, it remains unclear how well models perform at near-LES scales in representing ACI feedbacks when using realistic meteorological conditions and large case ensembles spanning diverse cloud states and synoptic regimes.

To address these gaps, our study makes three key advances: (1) we conduct a series of realistic near-LES-scale simulations that enable direct comparison with ground-based and satellite observations to reconcile observed–modeled discrepancies; (2) we examine a large ensemble of MBL cloud cases spanning a range of cloud states and synoptic conditions to capture the diversity of ACI responses; and (3) we employ the same two-moment microphysics scheme implemented in several GCMs and CPMs, making our findings directly relevant for improving microphysical parameterizations in climate models.

The simulated MBL clouds generally match the satellite observation in domain-mean cloud coverage and mesoscale organization (Figs. 1, 3, and S2–S4). However, the model struggle to reproduce the observed diurnal evolution of clouds, particularly afternoon cloud dissipation. The model overestimates cloud LWP, especially in polluted simulations, and underestimates cloud-top height compared to satellite retrievals. To illustrate the dependence of cloud responses on cloud state, LWP susceptibilities are displayed in the Nd–LWP parameter space (Fig. 5).

For non-precipitating thin clouds, our simulations show a consistently negative but weaker LWP susceptibility compared to satellite observations, with a mean value of −0.13. This negative LWP susceptibility likely results from better resolved turbulence, condensation-evaporation processes, and their feedback on PBL thermodynamics. More specifically, increases in aerosols enhance turbulence and TKE within the cloud layer. In the presence of dry air above clouds, the entrained dry air intensifies evaporation, reduces buoyancy flux in the cloud layer, and leads to cloud dissipation (Figs. 4 and 13).

For precipitating clouds, the model predicts a slight increase in LWP with a mean susceptibility of +0.15, consistent with the precipitation suppression hypothesis and with the climatological mean cloud response for heavily precipitating clouds (e.g., Qiu et al., 2024). For non-precipitating thick clouds, model simulations and satellite observations show the largest disagreement, with opposite LWP susceptibilities of +0.32 and −0.69, respectively. Meanwhile, non-precipitating thick clouds dominate the modeled cloud population, accounting for 49 % of occurrences, compared with only 15.7 % in satellite observations. This systematic bias can be traced to both aerosol and microphysical assumptions in the model. The overestimation of Nd arises from the prescribed aerosol concentration in the model configuration combined with the absence of precipitation scavenging. The overestimation of LWP primarily reflect the strong positive LWP susceptibility in thick clouds, whereas LWP in N=100 simulation shows good agreement with satellite retrievals (Fig. S9)