the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Persistent high PM pollution in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: insights from long-term observations and source apportionment in Cyprus

Elie Bimenyimana

Jean Sciare

Michael Pikridas

Konstantina Oikonomou

Minas Iakovides

Emily Vasiliadou

Chrysanthos Savvides

Nikos Mihalopoulos

Long-term daily PM2.5 and PM10 chemical speciation data was collected continuously from 2015 to 2023 at an urban traffic and regional background site in Cyprus, offering a unique opportunity to quantify the influence and trends of (i) local emissions on urban PM concentration levels and sources, and (ii) regional PM emissions over the Eastern Mediterranean basin.

Despite a statistically significant drop in PM2.5 and PM10 at both sites over the last 19 years (2005–2023), concentration levels remain high with no further significant improvements observed over the last 9 years; making PM concentration levels well above the new EU annual limits. To refine this analysis, long-term trends (2015–2023) were explored for individual PM chemical species and sources derived by PMF source apportionment. A decreasing trend in traffic-related PM10 of 35 % was observed at the traffic site, suggesting the effectiveness of the gradual shift of the vehicle fleet towards the latest EURO-standard vehicles. On the other hand, this reduction in tailpipe traffic emissions was completely offset by an increase of uncontrolled urban emissions, such as road dust re-suspension and biomass burning from domestic heating, calling for the rapid implementation of abatement measures.

Based on cluster analysis of air mass origins, the Middle East region was identified as a major hotspot of PM10 over the Eastern Mediterranean; with both high concentration levels of dust from the Arabian desert and substantial anthropogenic pollution with continuously increasing trends in biomass burning and sulfate-rich emissions from fossil fuel combustion over the past decade.

- Article

(3073 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(6956 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Particulate matter (PM) is a key component of air pollution with profound implications for human health (EEA, 2020; Lelieveld et al., 2019) and climate (IPCC, 2021; Myhre et al., 2013). Understanding the long-term evolution of PM concentration levels and sources over time enables the evaluation of the effectiveness of mitigation policies and possibly the identification of areas for improvement.

While long-term PM trends have been extensively studied in northern and central Europe, as well as the western Mediterranean (e.g. Borlaza et al., 2022; Giannossa et al., 2022; Merico et al., 2025; Pandolfi et al., 2016; Pérez-Vizcaíno et al., 2025; Querol et al., 2014; Tobarra et al., 2025), such long-term PM data remain scarce at urban and regional background sites of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East (EMME) region.

Most of the existing long-term PM observations in the region have been performed in Greece. In particular, declining trend of sulfate aerosols, as recorded from long-term PM chemical composition observations, has been identified as one of the key drivers responsible for the recent warming acceleration of the Mediterranean Basin (Urdiales-Flores et al., 2023). Combining ground-based PM10 and satellite products (dust aerosol optical depth, dust-AOD), Achilleos et al. (2020) assessed the trends of desert dust storms at several regional background sites in the Eastern Mediterranean basin for a 12-year period (2006–2017) both in terms of intensity and frequency but could not derive clear trends for this major regional source over this period. In urban environments, a reduction in PM concentrations has been observed in Greece, particularly before 2011, primarily resulting from policies targeting traffic emissions, followed by a rise driven by increasing residential wood burning emissions (Diapouli et al., 2017b; Kaskaoutis et al., 2023; Paraskevopoulou et al., 2015). Reduction in PM traffic emissions (by ca. 50 %) was further confirmed by Gratsea et al. (2017) for the period 2000–2015, based on CO observations taken in Athens during the morning traffic rush hours. Currently, only one comprehensive long-term study has been conducted so far in Cyprus (located at ca. 1000 km south-east of the Greek mainland), analyzing PM trends at several remote and urban sites of the national air quality monitoring network for a 17-year period (1998–2015) (Pikridas et al., 2018). This study reported downward trends in urban and regional PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations, but was unable to draw clear conclusions on the factors driving the observed decline due to lack of information on long-term PM chemical composition and sources. While PM trend observations from Greece could serve as reference, they may not be fully representative of the entire Eastern Mediterranean, given the significant differences in air mass origins (e.g. Middle East air masses are reaching the Levantine Basin and Cyprus but not Greece; Achilleos et al., 2020).

Overall, the current lack of long-term detailed data on PM chemical composition and sources in the region constitutes a major limitation to our understanding of the PM pollution long-term dynamics in Cyprus and the broader EMME, a region highly affected by a wide range of regional (both natural and anthropogenic) PM pollution sources (Fadel et al., 2023; Kanakidou et al., 2011; Lelieveld et al., 2002) further exacerbated by local uncontrolled emissions and climate change-induced environmental degradation, including prolonged droughts and severe heatwaves (Lelieveld et al., 2014; Zittis et al., 2022).

The work presented herewith stands as the most extensive long-term PM2.5 and PM10 chemical characterization conducted to date in Cyprus. By integrating continuous long-term (2015–2023) daily (24 h) PM chemical composition and robust PM source apportionment at both an urban traffic and a regional background site, this study reports, for the first time (to the best of our knowledge) simultaneous long-term trends in PM chemical composition and sources at both local (urban) and regional scales over the EMME.

2.1 Sampling sites and sample collection

This study was conducted at two contrasted sites of the Cyprus Air Quality monitoring network operated by the Department of Labour Inspection (Ministry of Labour and Social Insurance); an urban traffic site (NICosia TRAffic; NICTRA) and a regional background (Agia Marina Xyliatou; AMX). These two stations are those reporting annually the PM chemical composition to the European Commission in compliance with the EU Air Quality Directive 2008/50/EC (European Commission, 2008) and are located over 30 km away from each other (Fig. S1b in the Supplement).

The NICTRA station ( N, E; 176 m a.s.l.) is situated in a densely populated area within the urban agglomeration of Nicosia, the capital city of Cyprus, and near a major urban road (Fig. S1c). The rationale for selecting this site was to capture both the impact of road traffic emissions, but also any other type of urban emissions. The AMX station ( N, E; 532 m a.s.l.) is representative for the regional background conditions of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, as it is located at a remote rural area (see Fig. S1d), in the middle of the island, with minimal influence from local pollution. A detailed description of these two sites is available elsewhere (Bimenyimana et al., 2025; Pikridas et al., 2018; Tsagkaraki et al., 2021; Vrekoussis et al., 2022).

Continuous () PM filter sampling was carried out concurrently at the urban traffic site (NICTRA) in PM10 and at the regional background (AMX) in both PM2.5 and PM10. The sampling period extended over 19 years (2005–2023) for PM gravimetry and 9 years (2015–2023) for chemical analysis of major PM constituents (ions, carbon and trace metal content). More specifically, PM2.5 and PM10 were collected on a daily basis (from midnight to midnight, Local Standard Time) onto pre-weighed 47 and 150 mm diameter filters (Whatman Cellulose 7194-004 from 2005 to 2008; Whatman Quartz 1851-150 for 2008–2015; Pall Tissuquartz 2500 QAT-UP afterwards) using autonomous low- and high-volume samplers (Leckel SEQ 47/50 and Digitel DHA-80), with operational flow rates of 2.3 and 30 m3 h−1, respectively. Field blanks, collected and handled in the same way as field samples, were used for blank correction.

2.2 PM mass determination

Filter-based PM mass concentrations presented in this work were gravimetrically determined following the CEN 12341 reference filter weighing protocol (EN 12341, 2014). More specifically, PM filter samples, along with field blanks, were conditioned for 48 h at a room temperature of 20±1 °C and 50±5 % relative humidity. They were then weighed using a 6-digit analytical microbalance (Mettler Toledo, Model XP26C), prior to and after filter sampling.

Due to technical issues encountered with the PM2.5 filter weighing process at AMX for the period 2011–2014 (ca. 20 % of the dataset), the gravimetric PM2.5 data was substituted with daily averaged online measurements from a co-located TEOM instrument equipped with a Filter Dynamics Measurement System (FDMS; Thermo model 1405DF). Note that a good agreement (R2=0.96; slope = 1.02) between TEOM-FDMS and gravimetric PM mass determination methods has been reported by Pikridas et al. (2018) at that location.

2.3 PM chemical analyses

Filter samples were analyzed for a range of PM chemical components, including major ions, carbonaceous species (Organic carbon, OC, and elemental carbon, EC) and trace metal elements, using standard analytical methods, as described below.

Major cations (Na+, K+, NH, Mg2+, and Ca2+) and anions (Cl−, NO, and SO) were quantified by Ion Chromatography (IC; Thermo Scientific, Model ICS-5000) as described in details in Sciare et al. (2005). A filter punch was extracted with ultrapure water for 45 min by sonication. With this extraction method, over 98 % recovery is achieved for all targeted species. Cations and anions were separated using methanesulfonic acid (MSA) and potassium hydroxide (KOH) as eluents in isocratic and gradient mode, respectively.

OC and EC analysis was conducted on filter punches using a Sunset Laboratory OC-EC analyzer implemented with a thermo-optical analytical method following the EUSAAR-2 protocol (Cavalli et al., 2010). Fourteen (14) crustal and trace elements (Ca, Al, Fe, Ti, V, Ni, Se, As, Sb, Cd, Cr, Mn, Cu, Pb) were analyzed by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) after acid digestion. For more details on ICP-MS analysis, see Iakovides et al. (2021).

2.4 Data quality control

The quality of ions and carbon measurements was regularly evaluated through inter-laboratory comparison studies coordinated by the Quality Assurance/Science Activity Centre – Americas (QA/SAC-Americas) (http://www.qasac-americas.org, last access: 7 July 2025) and the European Centre for Aerosol Calibration (ECAC, https://www.actris-ecac.eu/, last access: 7 July 2025), respectively, while the ICP-MS analytical performance was assessed through inter-laboratory proficiency tests organized by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

2.5 Chemical mass closure

PM mass was reconstructed, as in Bimenyimana et al. (2023), using the chemical species presented above. Organic matter (OM) was derived from OC by applying site-specific conversion factors of 1.8 and 2 for the urban site (NICTRA) and the regional background (AMX), respectively (Turpin and Lim, 2001). Mineral dust was determined using the IMPROVE method (Chow et al., 2015; Malm et al., 1994), as shown in Eq. (1), except when trace metal data were not available, in which case it was derived from non-sea-salt calcium (nss-Ca Ca Na+) following the methodology proposed by Sciare et al. (2005).

The reconstructed PM mass was compared against the gravimetrically determined PM. The two methods exhibited strong agreement, with R2 ranging from 0.84 to 0.99 and slopes > 0.86 (see Fig. S2A, B and C), further indicating the high quality of our PM chemical composition database.

2.6 Data availability and coverage

Extensive daily PM10 chemical speciation data (3171 and 3356 individual filter samples at NICTRA and AMX, respectively), covering 84 %–98 % of each year, was collected at NICTRA and AMX for the period 2015–2023, and includes all species (ions, carbonaceous species and trace metals). For PM2.5, only ions and carbonaceous species were analyzed from 3331 daily filter samples, with a very good annual coverage (82 %–96 %). Daily PM2.5 ions data from AMX was also available for the period 2011–2014 and was used only in Sect. 3.6. Further information on the PM chemical speciation data availability at both sites can be found in Table S1 in the Supplement.

2.7 PM source apportionment

The compiled, extensive PM chemical database (23 individual chemical elements), which comprises a very large number of daily samples accumulated at each site over a decade offers a unique opportunity to perform long-term PM source apportionment and address trends not only for each chemical constituents but also for the various PM sources.

PM source apportionment was carried out using Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) receptor model (Paatero and Tapper, 1994). The source apportionment analysis was conducted separately for each site using PM chemical composition data covering a wide range of species, including major ions (Na+, K+, NH, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl−, NO, and SO), carbonaceous species (OC and EC), several trace metals (Al, Fe, Ti, V, Ni, As, Sb, Cd, Cr, Mn, Cu, and Pb) and PM mass. The 9-year PM chemical composition data was used as a single PMF input dataset. This approach enhances the stability of PMF factors and the robustness of the results. Furthermore, it produces consistent source profiles across the years, allowing us to track the evolution of each source contribution over time, which is the main focus of this study.

Before PMF modelling, missing values (< 1 % of the total number of samples) were replaced by the geometric mean of measured concentrations for each species, while below detection limit values (generally > 10 % of the database at both sites, except Cr (44 %), Ni (22 %) and Cu (21 %) at AMX) were substituted by half the method detection limit (MDL) (Polissar et al., 1998). The MDL is defined as three times the standard deviation of field blank measurements. MDL values used in this work are provided in Table S2. The uncertainties were estimated as shown in Eq. (2) following Xie and Berkowitz (2006).

where k is a parameter determined by trial and error ranging from 2 % to 16 %, Xij is the concentration of the jth species in the ith sample, and MDLij its method detection limit, while stands for the geometric mean for jth species Additional information on the quality control of the identified PM source profiles is presented in Sect. S1 (in the Supplement).

2.8 Air masses origin and classification

Air masses origin analysis (and their further classification into specific source regions) was performed in order to assign the various PM chemical constituents measured at the regional background site (AMX) to their respective source regions. This approach allows to build a multi-year PM chemical database for each source region; offering the opportunity to assess the influence of these source regions over time.

The Lagrangian particle dispersion model FLEXPART v8.23 (Stohl et al., 2005) was used to trace the origin of air masses affecting Cyprus at the regional background site (AMX). The model was driven by meteorological input data from National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR; USA) with a spatial resolution of 0.5°×0.5°. For each simulation, forty thousand (40 000) tracer particles were released every 6 h from the receptor site (AMX) at 350 m a.g.l. and followed 5 d backward in time. A total of 18 968 retroplumes (an improved substitute for traditional back-trajectories; Stohl et al., 2002) were calculated between 2011 and 2023 and subsequently categorized into seven (7) different source regions (namely North Africa, Middle East, Europe, West Turkey, Turkey, Marine and Local), based on the Potential Emission Sensitivity (PES), following the classification scheme of source regions described by Pikridas et al. (2018).

2.9 Ancillary observations

EU regulated ambient trace gases (NOx, SO2 and CO) data was collected alongside PM observations at both NICTRA and AMX stations throughout the study period. These gases, often co-emitted with primary PM pollutants (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016), can further serve as specific markers of combustion-related sources such as traffic and industrial emissions. These gaseous pollutant measurements were conducted using standard techniques namely non-dispersive IR spectroscopy (for CO), chemiluminescence (for NOx), and UV fluorescence (for SO2) techniques, as described in detail in Vrekoussis et al. (2022).

Factors controlling the seasonal variability of PM2.5 and PM10 at AMX and PM10 at NICTRA stations have been extensively documented by Bimenyimana et al. (2025), along with a comprehensive PM source apportionment and extensive discussion on the geographic origin of these sources (either local at city scale or regional). Briefly, NICTRA experiences peak PM concentrations during winter, driven by increased emissions from residential heating and stagnant meteorological conditions that limit dispersion of atmospheric pollutants. In contrast, higher PM concentrations are recorded during summer at AMX, due to absence of precipitation (limiting wet scavenging) and enhanced atmospheric (trans)formation processes (Bimenyimana et al., 2023). These aspects will not be discussed here again. Instead, the following discussion will focus on the inter-annual variability and long-term trends of the major chemical components and sources.

3.1 PMx concentration levels and long-term trends analysis

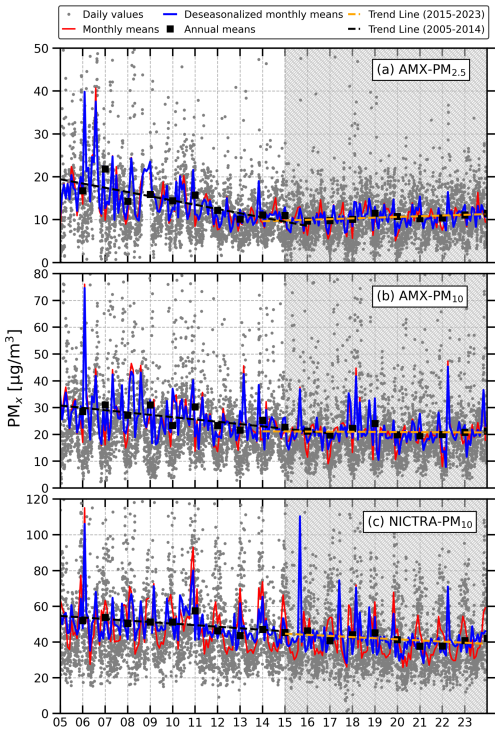

Daily values, monthly and annual averages, along with the de-seasonalized monthly means of PMx mass concentrations for the urban traffic site (NICTRA) and the regional background (AMX) are shown in Fig. 1. Discussions on the trends at both sites are presented below. Trend analysis was conducted using the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test implemented in Python following Gilbert (1987). To prevent seasonal fluctuations from masking long-term trends, our time series were first decomposed through STL (Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess) from the Python-based “statsmodels” package, and the resulting de-seasonalized component was subject to trend analysis.

3.1.1 Regional Background PMx (AMX)

Annual mean concentrations of 12.4 ± 3.0 µg m−3 for PM2.5 and 23.9 ± 3.7 µg m−3 for PM10 are calculated at AMX from 2005 to 2023. These PM levels are comparable to those observed by Pikridas et al. (2018) for the period 1998–2015 (14.0 ± 3.6 and 28.7±5.0 µg m−3, for PM2.5 and PM10, respectively) and Achilleos et al. (2020) between 2006 and 2017 (25.9 µg m−3 for PM10) at the same location.

When considering the entire 19-year (2005–2023) PM database, the Mann-Kendall trend analysis shows significant (p<0.01) decreasing trends in background PM2.5 and PM10 levels, with annual rates of −0.31 µg m−3 yr−1 (−3.0 % yr−1) and −0.49 µg m−3 yr−1 (−2.6 % yr−1), respectively, corresponding to a total reduction of 31 % for PM2.5 and 26 % for PM10, respectively.

These rates are half those previously reported by Pikridas et al. (2018) at the same location (−0.69 µg m−3 yr−1 for PM2.5 and −1.1 µg m−3 yr−1 for PM10) between 2005 and 2015, suggesting a slower decrease in the last decade. This is confirmed when considering the last 9 years (2015–2023) of our PM dataset which do not show any more a statistically significant decrease in PM2.5 and PM10 (see Fig. 1a and b, and Table 3). These stable PM10 levels over the last decade are further discussed in Sect. 3.4 in light of long-term trends in PM10 sources.

Interestingly, the observed decreasing trend in PM10 concentrations at our regional site (AMX) before 2015 is consistent with the temporal pattern of dust-AOD observed over Cyprus (see Fig. S3) and the broader Mediterranean basin (Shaheen et al., 2023; Logothetis et al., 2021; Marinou et al., 2017), which could suggest that regional dust emissions are an important driver of our regional PM10 trend. Shaheen et al. (2023) attributed the decline in regional dust to changes in regional weather patterns, particularly high winter sea-level pressure (SLP) and strong northwesterlies which inhibit dust storm activity over the region.

It is also worth noting that the reduction in our regional PM2.5 (which is largely dominated by ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4), Bimenyimana et al., 2025) before 2015 is consistent with the decreasing trend in sulfate levels observed in Europe (Aas et al., 2019, 2024) and the Eastern Mediterranean (Urdiales-Flores et al., 2023) over the last decades which can be attributed to international regulations targeting SO2 emissions (e.g. the Gothenburg Protocol; UNECE, 1999).

Figure 1Long-term trends in PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations from 2005 to 2023. Panels (a) and (b) show the regional background PM2.5 and PM10 levels (AMX), while panel (c) presents PM10 concentrations at the urban traffic site (NICTRA). The grey shaded areas indicate the period (2015–2023) during which complete chemical composition data is available.

3.1.2 Urban traffic PM 10 (NICTRA)

The urban PM10 concentrations (46.0 ± 5.5 µg m−3) are twice higher than those observed at the regional background over the same period (2005–2023), highlighting substantial contribution from local sources from the urban agglomeration such as traffic emissions, biomass burning, and road dust re-suspension, as extensively discussed by Bimenyimana et al. (2025). These urban PM10 concentrations are higher than in most locations of the Central and Western parts of the Mediterranean basin (Conte et al., 2020; Diapouli et al., 2017a; Merico et al., 2019; Pandolfi et al., 2020).

As shown in Fig. 1c, urban PM10 concentrations show a notable overall reduction of 19 % (−0.77 µg m−3 yr−1; p<0.001) from 2005 to 2023. This decline is less pronounced than that reported by Pikridas et al. (2018), suggesting, like the regional background site, slower or no improvement in PM10 levels in the recent years (from 2015 onward). This is further confirmed by the lack of statistically significant trend for PM10 at NICTRA over the period 2015–2023 (−0.24 µg m−3 yr−1; p>0.1; see Table 3). Similar patterns have been observed at several urban locations in Greece, with substantial decrease in PM concentrations from 2007 until 2011, followed by a moderate increase in 2012–2017 (Kaskaoutis et al., 2023). Stable PM10 concentration levels were also reported for Spain between 2017 and 2021 (Tobarra et al., 2025).

The use of the “Lenschow approach” (Lenschow et al., 2001) has been successfully tested and validated in Cyprus for the regional background station (AMX) and the Nicosia urban traffic (NICTRA) (Bimenyimana et al., 2025; Pikridas et al., 2018). This approach assumes that PM10 at NICTRA can be decomposed as the sum of a regional PM10 component (PM10-AMX) and a local PM10 fraction (PM10-Nicosia) (from emissions within Nicosia). This approach allows to derive a new PM10 daily dataset (PM10-Nicosia), covering the 19-year period (2005–2023), isolating the contribution from local urban emissions, which accounts for 50 % of total PM10 measured at NICTRA.

This results in a calculated decreasing trend of −0.29 µg m−3 yr−1 (p<0.001) for local PM10-Nicosia which can be attributed to a decrease in Nicosia emissions. In other words, local sources are only responsible for 38 % of the observed decrease over the period 2005–2023. This suggests that regional emissions have been the major driver of the observed decrease of PM10 at our traffic site, which result is quite unexpected given the major contribution of local emissions.

3.2 Long-term trends in PM chemical composition (2015–2023)

3.2.1 Regional background PM 2.5 (AMX)

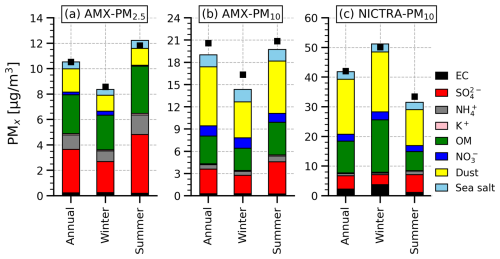

The main PM chemical components determined at AMX were averaged over the period 2015–2023. (NH4)2SO4 dominates the PM2.5 measured at the regional background (AMX) (Fig. 2a), making up 43 % of total PM2.5 mass (up to 50 % during summer), followed by OM (29 %), and dust (17 %). These results are fully consistent with those reported by Bimenyimana et al. (2025) from a one-year study conducted between mid-2016 and mid-2017 at AMX (48 %, 27 %, and 13 %, respectively, for (NH4)2SO4, OM, and dust).

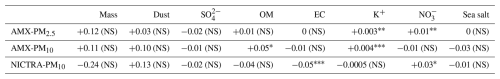

Most of the major PM2.5 constituents remained stable (p>0.1) throughout the study period (2015–2023) (see Table 1 and Fig. S4), a pattern also recorded for PM2.5 mass concentrations (see Sect. 3.1 above). The only exception is K+, a well-known biomass burning tracer, with major influence over the Eastern Mediterranean (e.g. Sciare et al., 2008). This compound shows an increasing trend of +3 ng m−3 yr−1 (+3.2 % yr−1, p<0.001), suggesting a rise in regional biomass burning emissions over the last decade (2015–2023). However, this increase does not appear to significantly influence the trend in OM which is the main chemical component from biomass burning. Further discussions on this trend are reported in Sect. 3.6 which examines the long-term evolution of this species across different geographic source regions.

3.2.2 Regional Background PM10 (AMX)

As expected, dust constitutes an important fraction of PM10 at the regional background (AMX), accounting for 42 % of the PM10 mass (Fig. 2b) and therefore can be considered as a driving force in the inter-annual variability and trend of PM10 in the Eastern Mediterranean (Achilleos et al., 2020). The calculated annual mean PM10 dust levels (8.0 µg m−3) observed at AMX (2015–2023) further confirm previous findings that Cyprus is the EU country being the most impacted by natural desert dust (Alastuey et al., 2016; Putaud et al., 2010; Querol et al., 2009), which results from substantial influence of dust from the Arabian desert in addition to the Saharan dust storms contribution (Pey et al., 2013; Achilleos et al., 2020).

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. S5, no statistically significant trends observed for most of the main PM10 components for the period 2015–2023, except K+ and OM exhibiting increasing trends of +4 ng m−3 yr−1 (+3.6 % yr−1, p<0.001) and +50 ng m−3 yr−1 (+1.4 % yr−1, p<0.05), respectively, that could be attributed to regional biomass burning (Fourtziou et al., 2017; Puxbaum et al., 2007).

3.2.3 Urban traffic PM10 (NICTRA)

As shown in Fig. 2c, the urban PM10 is primarily composed by dust (43 %) and carbonaceous aerosols (31 %, up to 43 % during winter). As such, their role cannot be overlooked when interpreting the observed multi-annual trends in PM10 concentrations.

Long-term trend of PM species at NICTRA is shown in Table 1 and Fig. S6. Similar to the observations made at the regional background site, most key PM10 species at NICTRA exhibit stable concentrations for the period 2015–2023, consistently with PM10 concentrations reported previously. However, EC shows a significant decline of −0.05 µg m−3 yr−1 (−2.6 % yr−1, p<0.001), most likely due to reductions in local traffic emissions (see Sect. 3.4). This pattern is consistent with Savadkoohi et al. (2023) reporting decreasing trends in BC concentrations ranging from −1.6 % yr−1 to −8.4 % yr−1 for fifty monitoring sites across Europe. Trend analysis was also performed on the local contributions to different PM constituents, derived by applying the “Lenschow” approach. Except OM for which a decreasing trend (−0.11 µg m−3 yr−1, −2.4 % yr−1; p<0.01) becomes evident only after excluding the regional fraction, trends for the other species remain almost unchanged.

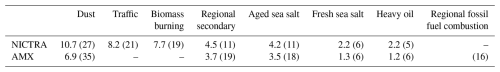

3.3 Overview of the PM source apportionment results over the period 2015–2023

This section presents briefly the main PM10 sources at NICTRA and AMX stations, while Sect. 3.4 provides a long-term perspective for each of them.

The PMF optimal solutions for the nine-year period (2015–2023) consist of seven factors for the urban traffic station (NICTRA) and six for the regional background (AMX). Among these sources, five are common to both sites: Regional secondary, dust, heavy oil, fresh sea salt and aged sea salt. Biomass burning source and traffic are resolved only at NICTRA, while the regional fossil fuel combustion source is identified only at AMX. The source profiles of the resolved factors are presented in Fig. S7. The PMF solutions obtained here are fully consistent with those reported for both AMX and NICTRA for a 1-year period (Bimenyimana et al., 2025). However, unlike the earlier study, we were able to resolve two distinct sea salt factors (aged and fresh sea salt). The averaged PM source contributions are presented in Table 2, while their multi-annual variability is shown in Figs. S9 and S10.

3.3.1 Sources identified at both sites (NICTRA and AMX)

Dust

The mineral dust factor is characterized by high abundance of crustal elements, namely Al (65 %–82 %), Ti (54 %–79 %), Fe (36 %–78 %), Ca2+ (40 %–67 %) and Mn (41 %–73 %). It is the most important PM10 source (Table 2), with average concentrations of 6.5 and 10.7 µg m−3 (33.5 % and 27 % of PM10 mass) at AMX and NICTRA, respectively. There is an additional urban (Nicosia) contribution to this dust factor, given that its concentrations at NICTRA are 65 % higher compared to the background levels measured at AMX. This urban dust is likely to be mainly associated with road dust re-suspension, as evidenced by the pronounced weekly variability of dust in PM10 (NICTRA), with significantly lower (p<0.05) concentrations during weekends (when traffic is expected to be lower) compared to weekdays. The PM10 dust concentrations observed in the current work are within the range of 6.2–12.2 µg m−3 reported by Diapouli et al. (2017b) for the sum of mineral and road dust in Athens and Thessaloniki during 2011–2012. They also align with the findings of Pérez-Vizcaíno et al. (2025) reporting values ranging from 7.3 to 8.9 µg m−3 for the “crustal + North African dust load” at several rural and urban sites in Spain for the period 2021–2023.

Regional secondary

The Regional secondary factor is found at both stations and exhibits elevated abundance of NH (83 %–90 %) and SO (48 %–49 %), species which have a clear regional origin (Bimenyimana et al., 2025). As expected, this source exhibits comparable levels at NICTRA and AMX, with average contributions of 4.5 and 3.7 µg m−3, accounting for 11 and 17 % of the PM10 mass, respectively, further confirming its regional nature. Similar concentrations (ranging from 3.1 to 5.7 µg m−3) have been observed at various sites in the Mediterranean region (Amato et al., 2016; Fadel et al., 2023; Pandolfi et al., 2016; Pérez-Vizcaíno et al., 2025).

Fresh and aged sea salt

Cl−, Na+ and to a lesser extent Mg2+ are the major species characterizing the fresh sea salt factor. The ratios (1.68 and 1.98 for NICTRA and AMX, respectively) are close to the sea water composition (1.8; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016), suggesting minimally processed (i.e. fresh) sea salt particles. The “fresh sea salt” factor accounts for 5 % and 6 % of the PM10 mass at AMX and NICTRA, respectively.

The “aged sea salt” factor exhibits significant loading of NO and SO, in addition to Na+. Cl− is absent in this factor likely due to its depletion as HCl, which is formed through reactions of atmospheric acids (SO2, HNO3) onto sea salt particles (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). As a factor highly influenced by anthropogenic emissions, aged sea salt concentrations are twice as high as those of fresh sea salt, contributing 11 % and 18 % to PM10 at NICTRA and AMX, respectively (Table 2).

Heavy oil combustion

This factor is characterized by high loading of specific tracers of this source (Celo et al., 2015; Viana et al., 2008), namely V (58 %–79 %) and Ni (61 %–64 %), and is responsible for 5.5 % and 7.5 % of PM10 mass at NICTRA and AMX, respectively. The average concentration level observed at NICTRA in this study (2.2 µg m−3) is nearly double that of AMX (1.2 µg m−3), suggesting significant local influence. It also ranks among the highest heavy oil/shipping contributions to PM10 recorded at various urban sites in the Mediterranean since 2011, which range from 0.74 to 2.7 µg m−3 (Amato et al., 2016; Clemente et al., 2021; Diapouli et al., 2017b; Manousakas et al., 2021; Pandolfi et al., 2016, 2020).

3.3.2 Sources resolved only at individual sites (NICTRA or AMX)

Traffic (at NICTRA)

The traffic factor is identified by high loading of EC and OC (ca. 60 % and 40 % of their respective masses), with an average ratio of 1.6, characteristic of tail-pipe vehicular emissions in Europe (Amato et al., 2016; Saraga et al., 2021). The high abundance of Cu (79 %), Cr (56 %), and Fe (46 %) suggests emissions from brake and tire abrasion (Amato et al., 2010; Belis et al., 2013; Viana et al., 2008). Traffic is the second most important PM10 source at NICTRA, with an overall average contribution of 8.2 µg m−3, accounting for 21 % of the PM10 mass, over the period 2015–2023, which falls within the range of 3.9–10.8 µg m−3 (18 %–31 % of PM10) reported by Amato et al. (2016) for the sum of exhaust and non-exhaust traffic in five southern European cities in the framework of the AIRUSE-LIFE+ project during 2013–2014. It is also consistent with the average traffic contribution to PM10 (7.3 µg m−3 or 29 %) observed at several traffic sites in Spain for 2021–2023 (Pérez-Vizcaíno et al., 2025).

Biomass burning (at NICTRA)

The biomass burning factor is found only at NICTRA and consists of a significant abundance of K+ (40 %) and carbonaceous species (40 % and 30 % of OC and EC total mass, respectively) with a higher ratio (3.1) compared to that of traffic. With an averaged contribution of 7.7 µg m−3 (19 %), biomass burning is almost equivalent to the traffic source in PM10 (at NICTRA) and relates to domestic heating (see Christodoulou et al., 2023; Bimenyimana et al., 2023). These biomass burning concentration levels are slightly lower than the findings of Diapouli et al. (2017b) for Athens and Thessaloniki (Greece) during 2011–2012 (8.2–11.6 µg m−3). In contrast, they are higher than those reported for most European cities (e.g. Amato et al., 2016; Borlaza et al., 2022), likely due to socio-economic factors favoring biomass burning emissions, as discussed in Sect. 3.4.

Regional fossil fuel combustion (at AMX)

This factor is characterized by carbonaceous species (43 % and 58 % for OC and EC, respectively), NO (32 %) and Pb (40 %). Interestingly, Pb is not significant in the traffic factor of NICTRA while it is prominent in this “regional fossil fuel combustion” factor at AMX, likely reflecting the influence of non-EU regulated regional (Middle East; see Sect. 3.5) lead-containing oil. This factor is also associated with elevated ratios (average: 5.4), much higher than the 1.6 found for the freshly emitted traffic factor at NICTRA, supporting a long-range transport origin along with atmospheric ageing processes. Regional fossil fuel combustion exhibits significant contribution (16 %) over the past nine years at AMX (2015–2023).

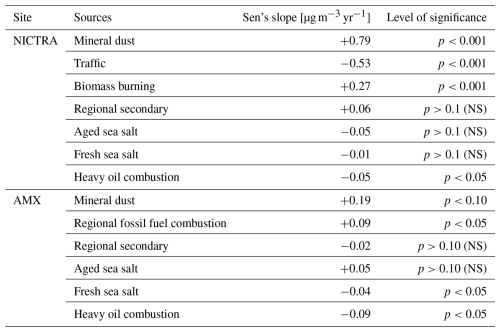

3.4 Trends in PM source contributions

Long-term trends in PM10 source concentrations at the urban traffic site (NICTRA) and the regional background (AMX) for the period 2015–2023 are presented in Table 3, as well as in Figs. S9 and S10. As mentioned earlier, this period exhibits no statistically significant trend (increase or decrease) for PM10 at either site.

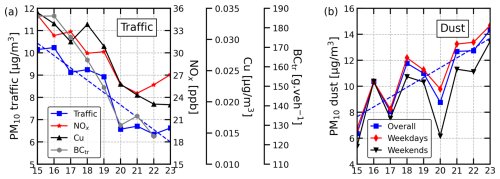

3.4.1 Traffic emissions (NICTRA)

As shown in Fig. 3a and Table 3, a clear downward trend (−0.53 µg m−3 yr−1; p<0.001), is observed at the urban traffic site (NICTRA) for the road traffic PM10 source. Over the past nine years (2015–2023), PM10 levels from traffic emissions have dropped by 35 %, from an annual average of 10.1 µg m−3 (28 % of PM mass) in 2015 to 6.6 µg m−3 (16 % of PM mass) in 2023. The major drop in the year 2020 can be attributed to the influence of the lockdown on traffic emissions in Nicosia as depicted by Putaud et al. (2023).

Similar long-term decreasing trends in traffic emissions have been reported at several locations in Europe (Borlaza et al., 2022; Diapouli et al., 2017b; In't Veld et al., 2021; Li et al., 2018; Pandolfi et al., 2016; Tobarra et al., 2025). Borlaza et al., (2022) observed a 58 % reduction in PM10 from traffic emissions at a remote site in France between 2012 and 2020. Similarly, a 56 % decrease for a mixed industrial/traffic PM2.5 factor was reported for Barcelona, Spain by Pandolfi et al. (2016) for the period 2004–2014. For the Eastern Mediterranean, Diapouli et al. (2017b) observed a drop in PM10 traffic exhaust emissions of ca. 45 % for 2011–2012 compared to 2002 in Athens (Greece). All these results illustrate the efforts to reduce air pollution across Europe through the implementation of stricter vehicle emission (EURO) standards.

The inter-annual variability of the PM traffic source observed at NICTRA aligns with the trends in co-located NOx (exhaust) and Cu (non-exhaust) concentrations (Fig. 3a), further supporting the decrease of this source at the traffic site. These observations are also consistent with a 33 % reduction in road transport-related BC emissions, as reported in the national emissions inventory to the European Commission (https://cdr.eionet.europa.eu/cy/un/clrtap/inventories/, last access: 7 July 2025).

The impact of vehicle fleet modernization on PM pollution has been highlighted by Zhou et al. (2020), who reported that completely phasing out Euro III vehicles and replacing them with cleaner technology like Euro VI could achieve a 99 % reduction in traffic-related PM emissions.

Figure 3Annual mean concentrations of: (a) traffic-related PM10 at NICTRA, NOx, Cu along with BC emissions from road transport (BCtr; in g.veh−1) retrieved from the national emissions inventories, and (b) PM10 dust at NICTRA for the period 2015–2023. The blue dashed lines depict the trend lines.

PMF source apportionment was also conducted for the beginning (2015) and the end (2023) of the study period to evaluate potential changes in chemical factor profile for the traffic source. No substantial differences are observed between 2015 and 2023, either in terms of concentrations of major species or relative contributions (%) of various tracers.

3.4.2 Dust trends (AMX and NICTRA)

Mineral dust levels exhibit rapid upward trend at NICTRA (see Fig. 3b), with an annual growth rate of +0.79 µg m−3 yr−1 (p<0.001) (see Table 3), completely offsetting the reduction in PM10 concentrations resulting from cuts in traffic emissions. This sharp increasing trend is likely to be primarily driven by local road dust emissions. This is supported by the smaller increase in background dust levels at AMX over the same period (+0.19 µg m−3 yr−1, p<0.1; Table 3) and relatively faster increase during weekdays compared to weekends (+0.80 µg m−3 yr−1 versus +0.63 µg m−3 yr−1, p<0.01).

3.4.3 Biomass burning (NICTRA)

An annual increase in biomass burning emissions of +0.27 µg m−3 yr−1 (p<0.001) is observed at NICTRA (Table 3). This is likely a result of a combination of the economic crisis occurred in Cyprus in 2012–2013 that has led to a shift toward cheaper fuels, such as wood, for residential heating in response to rising fuel prices, and the absence of guidelines promoting the use of modern (clean-combustion) wood stoves or boilers. Such shift was clearly documented in Greece experiencing similar financial crisis during the 2010–2013 period (Fourtziou et al., 2017; Vrekoussis et al., 2013). In contrast, a reduction in biomass burning has been recorded from observations at several locations in Europe (e.g. Ngoc Thuy Dinh et al., 2026; Font et al., 2022; Borlaza et al., 2022, and references therein), as well as from emission data for the residential sector since 2011 (EEA, 2023a).

3.4.4 Regional secondary (AMX and NICTRA)

As shown in Table 3, the Regional secondary source remains stable over the years for both the urban (NICTRA) and regional background (AMX) stations. This pattern contrasts with findings from other locations in Europe where this source (often referred to as secondary sulfate or sulfate-rich) exhibits a decreasing trend (Borlaza et al., 2022; Giannossa et al., 2022; Ngoc Thuy Dinh et al., 2026; Tobarra et al., 2025), likely due to differences in wind regimes, with Middle East airflows affecting only the Levantine. In fact, statistically significant increasing trend is observed during winter (DJF), when our receptor site in under the influence of Middle East air masses, with growth rates of +0.24 and +0.17 µg m−3 yr−1 (p<0.05), for NICTRA and AMX, respectively. The influence of air masses origin on the long-term variability of this source will be further discussed in Sect. 3.6.

3.4.5 Regional fossil fuel combustion (AMX)

A small, but statistically significant increase (+0.09 µg m−3 yr−1, p<0.05) is also observed for the regional fossil fuel combustion source at the regional background site, in contrast to the major decrease for the traffic source in Nicosia. Previous studies have highlighted a major influence of fossil fuel emissions from Middle East on PM levels over Cyprus (Bimenyimana et al., 2023; Christodoulou et al., 2023).

3.4.6 Heavy oil combustion (AMX and NICTRA)

Overall, significant decreasing trends are observed for the heavy oil combustion source at both NICTRA and AMX sites (−0.05 and −0.09 µg m−3 yr−1, respectively; p<0.05) likely due to improvement in ships fuel oil quality under the 0.5 % global sulfur cap which came into force in 2020 (Van Roy et al., 2023; Sofiev et al., 2018). An even more pronounced decline (−0.48 µg m−3 yr−1) was reported by Tobarra et al. (2025) for the port of Alicante in Spain between 2017 and 2021, which was explained by regulations targeting ship emissions and reduction in shipping activity.

3.5 Influence of regional hotspots on PM source contributions over Cyprus

This section examines the influence of air mass origins on PM source contributions at our regional background receptor site (AMX) over a nine-year period (2015–2023). A total of 6 clusters (source regions) were identified based on the air masses back trajectory climatology (Pikridas et al., 2018; Bimenyimana et al., 2023); namely Turkey (32 %), West Turkey (24 %), Middle East (16 %), North Africa (13 %), Europe (11 %) and Marine (3 %) (see more information in Sect. 2.5 and Fig. S11). Local cluster was discarded given its lower frequency of occurrence (1 %). Such clustering performed over almost a decade allows to characterize the main PM source hotspots (and their location) contributing the most to PM10 over Cyprus as measured at our regional background site (AMX). This approach allows us to better interpret any increasing or decreasing trends observed over Cyprus at our regional background site (AMX).

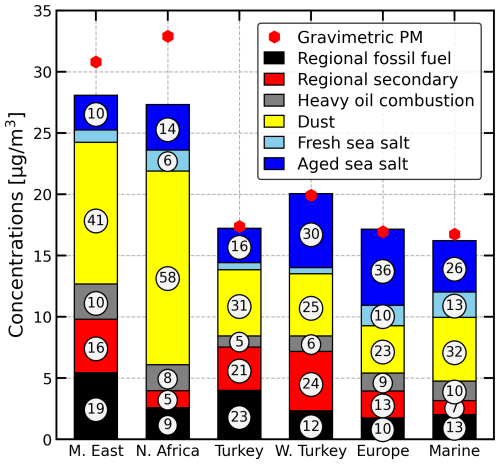

The resulted PM10 source apportionment for our 6 different clusters is reported in Fig. 4. Differences between clusters can be interpreted as follows.

3.5.1 North Africa versus Middle East clusters

The North Africa and Middle East regions exhibit the highest PM10 levels (32.2 and 29.1 µg m−3, respectively; Fig. 4). Although these contributions are quite similar, their sources differ considerably. As expected, desert dust is the most important PM10 source for North Africa, with an average contribution of 15.3 µg m−3 (57 % of PM10 mass). The Middle East sector is also characterized by high PM10 dust levels (10.2 µg m−3 or 39 % of PM10) from the Arabian desert, but also elevated concentrations of anthropogenic pollutants (e.g. of fossil fuel origin), which are nearly double those of North Africa, and are consistent with the well-documented influence of fossil fuel combustion in the Middle East (e.g. Osipov et al., 2022; Paris et al., 2021; Ukhov et al., 2020).

3.5.2 West Turkey versus other sectors

As expected, the West Turkey sector is associated with the highest sulfate-rich pollution (found in the Regional secondary source) compared to the other air mass sectors (including the Turkey sector; see Fig. 4), primarily due to coal-fired power plants that are mostly concentrated in the western region (Bimenyimana et al., 2025; Pikridas et al., 2010). Interestingly, despite the quasi-absence of coal-fired power plants in the Middle East, the sulfate-rich pollution levels observed for this region are comparable to those of West Turkey (4.3 versus 4.5 µg m−3, Fig. 4), likely due to emissions from other fossil fuel (oil) combustion sources.

3.6 Influence of regional hotspots on long-term PM trends over Cyprus

Within this section we explore the decadal trend of PM chemical composition and sources across various clusters. The daily occurrences for each source area are provided in Table S6 for the period 2011–2023 at the regional background site (AMX). This analysis is made possible thanks to the sufficient number of observations for each cluster, except the Marine sector that has limited data and was therefore excluded from further analysis.

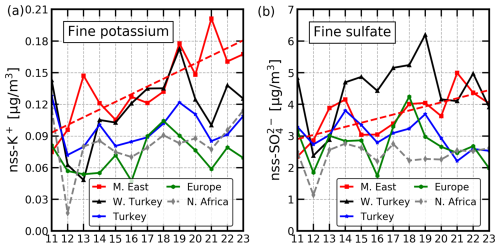

3.6.1 Regional biomass burning emissions

Because a separate biomass burning factor could not be resolved at the regional background, fine (PM2.5) non-sea-salt potassium (nss-K+ = K+ − 0.036× Na+) was used as proxy to assess the year-to-year and long-term trends in regional biomass burning emissions. As shown in Fig. 5a, the Middle East region is associated not only with the most elevated nss-K+ concentrations but also with a rapid increasing trend (+0.008 µg m−3 yr−1, p<0.01), as this species has increased by more than two-fold over the past 13 years (2011–2023) for this region. Since Middle East air masses are typically observed during winter (see Bimenyimana et al., 2023; Pikridas et al., 2018, and Fig. S11), period during which forest fires are minimal, this rising trend in nss-K+ is most likely due to increasing use of wood for residential heating or increasing agriculture waste burning.

Apart from the Middle East, a rapid upward trend in nss-K+ concentrations is also observed for the West Turkey sector until 2019 (+0.014 µg m−3 yr−1, p<0.05), followed by a sharp decline afterward (in 2020 and 2021). This increasing is most probably due to wildfires and/or crop stubble burning, as air masses from this sector are most frequent during summer (see Fig. S11). The drop in 2020–2021 is most likely linked to COVID-19 lockdowns, which have contributed to a reduction in wildfires activity in many regions across the globe (Poulter et al., 2021). The remaining sectors (Turkey, Europe and North Africa) exhibit relatively low and stable nss-K+ levels, with only minimal variations (no statistically significant) over time.

3.6.2 Growing influence of regional sulfur-containing fossil fuel combustion

Fine (PM2.5) non-sea-salt sulfate (nss-SO SO- 0.252× Na+) data collected at AMX was used here to describe the influence of the main regional sources of sulfur-containing fossil fuel combustion over time (2011–2023).

As illustrated in Fig. 5b, the West Turkey sector not only has the highest nss-SO levels but also exhibits an increasing trend until 2019 (slope µg m−3 yr−1, p<0.05), followed by a sharp decrease in 2020 that might be a result of COVID-19 restrictions. This nss-SO trend aligns with the growing coal power capacity for Turkey to meet its energy demand (Vardar et al., 2022), despite the efforts to reduce coal use under the Paris agreement. This trend is also consistent with the annual reporting of SO2 emissions from Turkey (EEA, 2023b).

Surprisingly, nss-SO concentration levels have been consistently increasing also for the Middle East sector throughout the study period (2011–2023), with a significant growth rate of +0.14 µg m−3 yr−1 (p<0.01), rising from 2.2 µg m−3 in 2011 to 4.0 µg m−3 in 2023, an increase of about 82 %. This major increase goes along with the upward trend in fossil fuel CO2 emissions observed in the Middle East countries, mainly driven by energy production as well as the oil and gas industry (Friedlingstein et al., 2022; Paris et al., 2021). Similar results are observed for the Regional secondary PMF-resolved factor, which shows a significant increasing trend of +0.54 µg m−3 yr−1 (p<0.05) for the Middle East sector between 2015 and 2023 (Fig. S12). Interestingly, the Middle East is gradually surpassing Turkey (the West Turkey sector) which has long been the main origin of sulfate-rich pollution affecting Cyprus.

The local (Nicosia) and regional (EMME) long-term trends in PM chemical composition and PM sources were quantified here using a large daily PM chemical composition database collected continuously for a period of nine years (2015–2023) at an urban traffic site of Nicosia (NICTRA) and a regional background site (AMX). This approach enabled to assess the influence of local and regional emissions on PM long-term variability and to evaluate the potential effectiveness of local abatement measures.

Although PM2.5 and PM10 concentration levels have decreased at both sites over the last 19 years (2005–2023), concentration levels remain high with no further significant improvements observed over the last 9 years. To further interpret our local and regional PM trends, PMF source apportionment was applied to PM10 chemical composition data covering the period 2015–2023. This analysis allowed to apportion seven (7) PM sources at NICTRA and six (6) at AMX, five of which (Regional secondary, dust, heavy oil, fresh sea salt and aged sea salt) being common to both sites, whereas biomass burning and traffic are resolved only at NICTRA and regional fossil fuel combustion only at AMX. Dust stands out as the major PM10 source at both NICTRA and AMX (27 % and 35 % of PM10 at NICTRA and AMX, respectively), with background PM10 levels exceeding those observed at most background/rural locations in Europe due to the proximity of Cyprus to both Saharan and Arabian deserts.

At local scale (Nicosia), a decreasing trend in traffic-related emissions (mostly from exhaust) of 35 % (2015–2023) was observed, probably as a result of the gradual switch of the vehicle fleet towards higher EURO standards which are characterized by lower direct (tailpipe) PM emissions. However, these efforts are not reflected in the total urban PM10 levels, since uncontrolled emissions from other local sources, such as road dust re-suspension and biomass burning for domestic heating are rising at a rate comparable to that of traffic source, thereby offsetting the benefits induced by the more stringent EURO VI standards.

At regional scale (EMME), the impact of air mass origins on PM10 was investigated at the regional background site (AMX) using cluster analysis. While North Africa and Middle East sectors exhibited comparable influence on PM10 levels (32.2 versus 29.1 µg m−3), the emission sources driving this PM pollution differ significantly between the two sectors. Notably, the Middle East is characterized by not only high dust levels (39 %) but also by substantial anthropogenic pollution that is nearly double that of North Africa.

This observation is also consistent with the fact that the Middle East sector was found to (1) exhibit an upward trend in sulfate-rich emissions from fossil fuel combustion, gradually exceeding levels observed in Turkey, a country known as one of the largest SO2 emitters worldwide, and (2) increasingly contribute to biomass burning over Cyprus.

Overall, this work suggests that, despite major efforts to reduce PM emissions through adoption of low-emission vehicles, the increase in uncontrolled emissions from local sources (road dust resuspension and biomass burning), along with rising regional fossil fuel emissions mainly from Middle East are likely to undermine efforts to decrease PM concentration levels in Cypriot cities. Consequently, it makes it challenging to comply with the stricter PM10 limits set by the new EU air quality directives (Directive (EU) 2024/2881; EU, 2024).

Data used in this study are readily accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18305165 (Bimenyimana et al., 2026).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-1605-2026-supplement.

EB: Acquisition of measurements, data processing and writing-original draft. JS: Funding acquisition, supervision, review, editing and improvement of the manuscript. MP, KO, MI, EV, CS: Acquisition of measurements, data processing, contribution to the original draft. NM: Supervision, review, editing and improvement of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors sincerely thank the Department of Labor Inspection (DLI) for providing the PM chemical composition data.

This work has been supported financially by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme and the Cyprus Government under grant agreement no. 856612 (EMME-CARE).

This paper was edited by Lynn M. Russell and reviewed by four anonymous referees.

Aas, W., Mortier, A., Bowersox, V., Cherian, R., Faluvegi, G., Fagerli, H., Hand, J., Klimont, Z., Galy-Lacaux, C., and Lehmann, C. M. B.: Global and regional trends of atmospheric sulfur, Sci. Rep., 9, 953, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37304-0, 2019.

Aas, W., Fagerli, H., Alastuey, A., Cavalli, F., Degorska, A., Feigenspan, S., Brenna, H., Gliß, J., Heinesen, D., and Hueglin, C.: Trends in air pollution in Europe, 2000–2019, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 24, 230237, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.230237, 2024.

Achilleos, S., Mouzourides, P., Kalivitis, N., Katra, I., Kloog, I., Kouis, P., Middleton, N., Mihalopoulos, N., Neophytou, M., Panayiotou, A., Papatheodorou, S., Savvides, C., Tymvios, F., Vasiliadou, E., Yiallouros, P., and Koutrakis, P.: Spatio-temporal variability of desert dust storms in Eastern Mediterranean (Crete, Cyprus, Israel) between 2006 and 2017 using a uniform methodology, Sci. Total Environ., 714, 136693, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.136693, 2020.

Alastuey, A., Querol, X., Aas, W., Lucarelli, F., Pérez, N., Moreno, T., Cavalli, F., Areskoug, H., Balan, V., Catrambone, M., Ceburnis, D., Cerro, J. C., Conil, S., Gevorgyan, L., Hueglin, C., Imre, K., Jaffrezo, J.-L., Leeson, S. R., Mihalopoulos, N., Mitosinkova, M., O'Dowd, C. D., Pey, J., Putaud, J.-P., Riffault, V., Ripoll, A., Sciare, J., Sellegri, K., Spindler, G., and Yttri, K. E.: Geochemistry of PM10 over Europe during the EMEP intensive measurement periods in summer 2012 and winter 2013, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 6107–6129, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-6107-2016, 2016.

Amato, F., Nava, S., Lucarelli, F., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Baldasano, J. M., and Pandolfi, M.: A comprehensive assessment of PM emissions from paved roads: Real-world Emission Factors and intense street cleaning trials, Sci. Total Environ., 408, 4309–4318, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2010.06.008, 2010.

Amato, F., Alastuey, A., Karanasiou, A., Lucarelli, F., Nava, S., Calzolai, G., Severi, M., Becagli, S., Gianelle, V. L., Colombi, C., Alves, C., Custódio, D., Nunes, T., Cerqueira, M., Pio, C., Eleftheriadis, K., Diapouli, E., Reche, C., Minguillón, M. C., Manousakas, M.-I., Maggos, T., Vratolis, S., Harrison, R. M., and Querol, X.: AIRUSE-LIFE+: a harmonized PM speciation and source apportionment in five southern European cities, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 3289–3309, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-3289-2016, 2016.

Bimenyimana, E.: Persistent high PM pollution in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: Insights from long-term observations and source apportionment in Cyprus, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18305165, 2026.

Bimenyimana, E., Pikridas, M., Oikonomou, K., Iakovides, M., Christodoulou, A., Sciare, J., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Fine aerosol sources at an urban background site in the eastern Mediterranean (Nicosia; Cyprus): Insights from offline versus online source apportionment comparison for carbonaceous aerosols, Sci. Total Environ., 164741, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164741, 2023.

Bimenyimana, E., Sciare, J., Oikonomou, K., Iakovides, M., Pikridas, M., Vasiliadou, E., Savvides, C., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Cross-validation of methods for quantifying the contribution of local (urban) and regional sources to PM2.5 pollution: application in the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus), Atmos. Environ., 120975, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120975, 2025.

Bimenyimana, E., Sciare, J., Pikridas, M., Oikonomou, K., Iakovides, M., Vasiliadou, E., Savvides, C., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Persistent high PM pollution in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: Insights from long-term observations and source apportionment in Cyprus, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18305165, 2026.

Belis, C. A., Karagulian, F., Larsen, B. R., and Hopke, P. K.: Critical review and meta-analysis of ambient particulate matter source apportionment using receptor models in Europe, Atmos. Environ., 69, 94–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.11.009, 2013.

Borlaza, L. J., Weber, S., Marsal, A., Uzu, G., Jacob, V., Besombes, J.-L., Chatain, M., Conil, S., and Jaffrezo, J.-L.: Nine-year trends of PM10 sources and oxidative potential in a rural background site in France, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 8701–8723, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-8701-2022, 2022.

Cavalli, F., Viana, M., Yttri, K. E., Genberg, J., and Putaud, J.-P.: Toward a standardised thermal-optical protocol for measuring atmospheric organic and elemental carbon: the EUSAAR protocol, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 3, 79–89, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-3-79-2010, 2010.

Celo, V., Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E., and McCurdy, M.: Chemical Characterization of Exhaust Emissions from Selected Canadian Marine Vessels: The Case of Trace Metals and Lanthanoids, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 5220–5226, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b00127, 2015.

Chow, J. C., Lowenthal, D. H., Chen, L. W. A., Wang, X., and Watson, J. G.: Mass reconstruction methods for PM2.5: a review, Air Qual. Atmos. Heal., 8, 243–263, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-015-0338-3, 2015.

Christodoulou, A., Stavroulas, I., Vrekoussis, M., Desservettaz, M., Pikridas, M., Bimenyimana, E., Kushta, J., Ivančič, M., Rigler, M., Goloub, P., Oikonomou, K., Sarda-Estève, R., Savvides, C., Afif, C., Mihalopoulos, N., Sauvage, S., and Sciare, J.: Ambient carbonaceous aerosol levels in Cyprus and the role of pollution transport from the Middle East, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 6431–6456, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-6431-2023, 2023.

Clemente, Á., Yubero, E., Galindo, N., Crespo, J., Nicolás, J. F., Santacatalina, M., and Carratalá, A.: Quantification of the impact of port activities on PM10 levels at the port-city boundary of a mediterranean city, J. Environ. Manage., 281, 111842, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111842, 2021.

Conte, M., Merico, E., Cesari, D., Dinoi, A., Grasso, F. M., Donateo, A., Guascito, M. R., and Contini, D.: Long-term characterisation of African dust advection in south-eastern Italy: Influence on fine and coarse particle concentrations, size distributions, and carbon content, Atmos. Res., 233, 104690, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2019.104690, 2020.

Diapouli, E., Manousakas, M. I., Vratolis, S., Vasilatou, V., Pateraki, S., Bairachtari, K. A., Querol, X., Amato, F., Alastuey, A., Karanasiou, A. A., Lucarelli, F., Nava, S., Calzolai, G., Gianelle, V. L., Colombi, C., Alves, C., Custódio, D., Pio, C., Spyrou, C., Kallos, G. B., and Eleftheriadis, K.: AIRUSE-LIFE +: estimation of natural source contributions to urban ambient air PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in southern Europe – implications to compliance with limit values, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 3673–3685, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-3673-2017, 2017a.

Diapouli, E., Manousakas, M., Vratolis, S., Vasilatou, V., Maggos, T., Saraga, D., Grigoratos, T., Argyropoulos, G., Voutsa, D., and Samara, C.: Evolution of air pollution source contributions over one decade, derived by PM10 and PM2.5 source apportionment in two metropolitan urban areas in Greece, Atmos. Environ., 164, 416–430, 2017b.

EEA: Air quality in Europe – 2020 report, 162 pp., https://doi.org/10.2800/786656, 2020.

EEA: European Union emission inventory report 1990–2021 – Under the UNECE Convention on Long – range Transboundary Air Pollution (Air Convention), https://doi.org/10.2800/68478, 2023a.

EEA: Türkiye: Air pollution country fact sheet 2023, https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/maps-and-charts/turkiye-air-pollution-country-2023-country-fact-sheets (last access: 28 January 2026), 2023b.

EN 12341: Ambient air – Standard gravimetric measurement method for the determination of the PM10 or PM2.5 mass concentration of suspended particulate matter, https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/sist/5d138eac-4d44-4419-a069-eb23d01a9b0c/sist-en-12341-2014 (last access: 28 January 2026), 2014.

EU: Directive (EU) 2024/2881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe, Off. J. Eur. Union, http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/2881/oj (last access: 28 January 2026), 2024.

European Commission: Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe, Off. J. Eur. Union, 152, 1–44, 2008.

Fadel, M., Courcot, D., Seigneur, M., Kfoury, A., Oikonomou, K., Sciare, J., Ledoux, F., and Afif, C.: Identification and apportionment of local and long-range sources of PM2.5 in two East-Mediterranean sites, Atmos. Pollut. Res., 14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2022.101622, 2023.

Font, A., Ciupek, K., Butterfield, D., and Fuller, G. W.: Long-term trends in particulate matter from wood burning in the United Kingdom: Dependence on weather and social factors, Environ. Pollut., 314, 120105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120105, 2022.

Fourtziou, L., Liakakou, E., Stavroulas, I., Theodosi, C., Zarmpas, P., Psiloglou, B., Sciare, J., Maggos, T., Bairachtari, K., Bougiatioti, A., Gerasopoulos, E., Sarda-Estève, R., Bonnaire, N., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Multi-tracer approach to characterize domestic wood burning in Athens (Greece) during wintertime, Atmos. Environ., 148, 89–101, 2017.

Friedlingstein, P., O'Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Gregor, L., Hauck, J., Le Quéré, C., Luijkx, I. T., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Alkama, R., Arneth, A., Arora, V. K., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Bittig, H. C., Bopp, L., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Cronin, M., Evans, W., Falk, S., Feely, R. A., Gasser, T., Gehlen, M., Gkritzalis, T., Gloege, L., Grassi, G., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Houghton, R. A., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jain, A. K., Jersild, A., Kadono, K., Kato, E., Kennedy, D., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Landschützer, P., Lefèvre, N., Lindsay, K., Liu, J., Liu, Z., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGrath, M. J., Metzl, N., Monacci, N. M., Munro, D. R., Nakaoka, S.-I., Niwa, Y., O'Brien, K., Ono, T., Palmer, P. I., Pan, N., Pierrot, D., Pocock, K., Poulter, B., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rödenbeck, C., Rodriguez, C., Rosan, T. M., Schwinger, J., Séférian, R., Shutler, J. D., Skjelvan, I., Steinhoff, T., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Sweeney, C., Takao, S., Tanhua, T., Tans, P. P., Tian, X., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G. R., Walker, A. P., Wanninkhof, R., Whitehead, C., Willstrand Wranne, A., Wright, R., Yuan, W., Yue, C., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, J., and Zheng, B.: Global Carbon Budget 2022, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14, 4811–4900, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4811-2022, 2022.

Giannossa, L. C., Cesari, D., Merico, E., Dinoi, A., Mangone, A., Guascito, M. R., and Contini, D.: Inter-annual variability of source contributions to PM10, PM2.5, and oxidative potential in an urban background site in the central mediterranean, J. Environ. Manage., 319, 115752, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115752, 2022.

Gilbert, R. O.: Statistical methods for environmental pollution monitoring, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-28878-7, 1987.

Gratsea, M., Liakakou, E., Mihalopoulos, N., Adamopoulos, A., Tsilibari, E., and Gerasopoulos, E.: The combined effect of reduced fossil fuel consumption and increasing biomass combustion on Athens' air quality, as inferred from long term CO measurements, Sci. Total Environ., 592, 115–123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.045, 2017.

Iakovides, M., Iakovides, G., and Stephanou, E. G.: Atmospheric particle-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, n-alkanes, hopanes, steranes and trace metals: PM2.5 source identification, individual and cumulative multi-pathway lifetime cancer risk assessment in the urban environment, Sci. Total Environ., 752, 141834, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.141834, 2021.

In't Veld, M., Alastuey, A., Pandolfi, M., Amato, F., Perez, N., Reche, C., Via, M., Minguillon, M. C., Escudero, M., and Querol, X.: Compositional changes of PM2.5 in NE Spain during 2009–2018: A trend analysis of the chemical composition and source apportionment, Sci. Total Environ., 795, 148728, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148728, 2021.

IPCC: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2021.

Kanakidou, M., Mihalopoulos, N., Kindap, T., Im, U., Vrekoussis, M., Gerasopoulos, E., Dermitzaki, E., Unal, A., Koçak, M., Markakis, K., Melas, D., Kouvarakis, G., Youssef, A. F., Richter, A., Hatzianastassiou, N., Hilboll, A., Ebojie, F., Wittrock, F., von Savigny, C., Burrows, J. P., Ladstaetter-Weissenmayer, A., and Moubasher, H.: Megacities as hot spots of air pollution in the East Mediterranean, Atmos. Environ., 1223–1235, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.048, 2011.

Kaskaoutis, D. G., Liakakou, E., Grivas, G., Gerasopoulos, E., Mihalopoulos, N., Alastuey, A., Dulac, F., Dumka, U. C., Pandolfi, M., and Pikridas, M.: Interannual variability and long-term trends of aerosols above the Mediterranean, in: Atmospheric Chemistry in the Mediterranean Region: Volume 1-Background Information and Pollutant Distribution, Springer, 357–390, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12741-0_11, 2023.

Lelieveld, J., Berresheim, H., Borrmann, S., Crutzen, P. J., Dentener, F. J., Fischer, H., Feichter, J., Flatau, P. J., Heland, J., Holzinger, R., Korrmann, R., Lawrence, M. G., Levin, Z., Markowicz, K. M., Mihalopoulos, N., Minikin, A., Ramanathan, V., De Reus, M., Roelofs, G. J., Scheeren, H. A., Sciare, J., Schlager, H., Schultz, M., Siegmund, P., Steil, B., Stephanou, E. G., Stier, P., Traub, M., Warneke, C., Williams, J., and Ziereis, H.: Global air pollution crossroads over the Mediterranean, Science, 298, 794–799, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1075457, 2002.

Lelieveld, J., Hadjinicolaou, P., Kostopoulou, E., Giannakopoulos, C., Pozzer, A., Tanarhte, M., and Tyrlis, E.: Model projected heat extremes and air pollution in the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East in the twenty-first century, Reg. Environ. Chang., 14, 1937–1949, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0444-4, 2014.

Lelieveld, J., Klingmüller, K., Pozzer, A., Burnett, R. T., Haines, A., and Ramanathan, V.: Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 116, 7192–7197, 2019.

Lenschow, P., Abraham, H.-J., Kutzner, K., Lutz, M., Preuß, J.-D., and Reichenbächer, W.: Some ideas about the sources of PM10, Atmos. Environ., 35, S23–S33, 2001.

Li, J., Chen, B., de la Campa, A. M. S., Alastuey, A., Querol, X., and de la Rosa, J. D.: 2005–2014 trends of PM10 source contributions in an industrialized area of southern Spain, Environ. Pollut., 236, 570–579, 2018.

Logothetis, S.-A., Salamalikis, V., Gkikas, A., Kazadzis, S., Amiridis, V., and Kazantzidis, A.: 15-year variability of desert dust optical depth on global and regional scales, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 16499–16529, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-16499-2021, 2021.

Malm, W. C., Sisler, J. F., Huffman, D., Eldred, R. A., and Cahill, T. A.: Spatial and seasonal trends in particle concentration and optical extinction in the United States, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 99, 1347–1370, 1994.

Manousakas, M., Diapouli, E., Belis, C. A., Vasilatou, V., Gini, M., Lucarelli, F., Querol, X., and Eleftheriadis, K.: Quantitative assessment of the variability in chemical profiles from source apportionment analysis of PM10 and PM2.5 at different sites within a large metropolitan area, Environ. Res., 192, 110257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110257, 2021.

Marinou, E., Amiridis, V., Binietoglou, I., Tsikerdekis, A., Solomos, S., Proestakis, E., Konsta, D., Papagiannopoulos, N., Tsekeri, A., Vlastou, G., Zanis, P., Balis, D., Wandinger, U., and Ansmann, A.: Three-dimensional evolution of Saharan dust transport towards Europe based on a 9-year EARLINET-optimized CALIPSO dataset, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 5893–5919, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-5893-2017, 2017.

Merico, E., Cesari, D., Dinoi, A., Gambaro, A., Barbaro, E., Guascito, M. R., Giannossa, L. C., Mangone, A., and Contini, D.: Inter-comparison of carbon content in PM10 and PM2.5 measured with two thermo-optical protocols on samples collected in a Mediterranean site, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 26, 29334–29350, 2019.

Merico, E., Cesari, D., Dinoi, A., Potì, S., Pennetta, A., Bloise, E., and Contini, D.: Long-term analysis of carbonaceous fractions of particulate at a Central Mediterranean site in Italy, Atmos. Pollut. Res., 102668, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2025.102668, 2025.

Myhre, G., Samset, B. H., Schulz, M., Balkanski, Y., Bauer, S., Berntsen, T. K., Bian, H., Bellouin, N., Chin, M., Diehl, T., Easter, R. C., Feichter, J., Ghan, S. J., Hauglustaine, D., Iversen, T., Kinne, S., Kirkevåg, A., Lamarque, J.-F., Lin, G., Liu, X., Lund, M. T., Luo, G., Ma, X., van Noije, T., Penner, J. E., Rasch, P. J., Ruiz, A., Seland, Ø., Skeie, R. B., Stier, P., Takemura, T., Tsigaridis, K., Wang, P., Wang, Z., Xu, L., Yu, H., Yu, F., Yoon, J.-H., Zhang, K., Zhang, H., and Zhou, C.: Radiative forcing of the direct aerosol effect from AeroCom Phase II simulations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 1853–1877, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-1853-2013, 2013.

Ngoc Thuy Dinh, V., Jaffrezo, J.-L., Dominutti, P. A., Elazzouzi, R., Darfeuil, S., Voiron, C., Marsal, A., Socquet, S., Mary, G., Cozic, J., Coulaud, C., Durif, M., Favez, O., and Uzu, G.: Decadal trends (2013–2023) in PM10 sources and oxidative potential at a European urban supersite (Grenoble, France), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 26, 247–268, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-247-2026, 2026.

Osipov, S., Chowdhury, S., Crowley, J. N., Tadic, I., Drewnick, F., Borrmann, S., Eger, P., Fachinger, F., Fischer, H., Predybaylo, E., Fnais, M., Harder, H., Pikridas, M., Vouterakos, P., Pozzer, A., Sciare, J., Ukhov, A., Stenchikov, G. L., Williams, J., and Lelieveld, J.: Severe atmospheric pollution in the Middle East is attributable to anthropogenic sources, Commun. Earth Environ., 3, 203, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00514-6, 2022.

Paatero, P. and Tapper, U.: Positive matrix factorization: A non-negative factor model with optimal utilization of error estimates of data values, Environmetrics, 5, 111–126, https://doi.org/10.1002/ENV.3170050203, 1994.

Pandolfi, M., Alastuey, A., Pérez, N., Reche, C., Castro, I., Shatalov, V., and Querol, X.: Trends analysis of PM source contributions and chemical tracers in NE Spain during 2004–2014: a multi-exponential approach, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11787–11805, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11787-2016, 2016.

Pandolfi, M., Mooibroek, D., Hopke, P., van Pinxteren, D., Querol, X., Herrmann, H., Alastuey, A., Favez, O., Hüglin, C., Perdrix, E., Riffault, V., Sauvage, S., van der Swaluw, E., Tarasova, O., and Colette, A.: Long-range and local air pollution: what can we learn from chemical speciation of particulate matter at paired sites?, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 409–429, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-409-2020, 2020.

Paraskevopoulou, D., Liakakou, E., Gerasopoulos, E., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Sources of atmospheric aerosol from long-term measurements (5 years) of chemical composition in Athens, Greece, Sci. Total Environ., 527–528, 165–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.04.022, 2015.

Paris, J.-D., Riandet, A., Bourtsoukidis, E., Delmotte, M., Berchet, A., Williams, J., Ernle, L., Tadic, I., Harder, H., and Lelieveld, J.: Shipborne measurements of methane and carbon dioxide in the Middle East and Mediterranean areas and the contribution from oil and gas emissions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 12443–12462, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-12443-2021, 2021.

Pérez-Vizcaíno, P., de la Campa, A. M. S., Sánchez-Rodas, D., Alastuey, A., Querol, X., and de la Rosa, J. D.: PM10 chemical fingerprints and source assessment guiding air quality improvements by 2030 in Andalusia, southern Spain, Environ. Pollut., 127347, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2025.127347, 2025.

Pey, J., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Forastiere, F., and Stafoggia, M.: African dust outbreaks over the Mediterranean Basin during 2001–2011: PM10 concentrations, phenomenology and trends, and its relation with synoptic and mesoscale meteorology, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 1395–1410, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-1395-2013, 2013.

Pikridas, M., Bougiatioti, A., Hildebrandt, L., Engelhart, G. J., Kostenidou, E., Mohr, C., Prévôt, A. S. H., Kouvarakis, G., Zarmpas, P., Burkhart, J. F., Lee, B.-H., Psichoudaki, M., Mihalopoulos, N., Pilinis, C., Stohl, A., Baltensperger, U., Kulmala, M., and Pandis, S. N.: The Finokalia Aerosol Measurement Experiment – 2008 (FAME-08): an overview, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 6793–6806, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-6793-2010, 2010.

Pikridas, M., Vrekoussis, M., Sciare, J., Kleanthous, S., Vasiliadou, E., Kizas, C., Savvides, C., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Spatial and temporal (short and long-term) variability of submicron, fine and sub-10 µm particulate matter (PM1, PM2.5, PM10) in Cyprus, Atmos. Environ., 191, 79–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.07.048, 2018.

Polissar, A. V, Hopke, P. K., Paatero, P., Malm, W. C., and Sisler, J. F.: Atmospheric aerosol over Alaska: 2. Elemental composition and sources, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 103, 19045–19057, 1998.

Poulter, B., Freeborn, P. H., Jolly, W. M., and Varner, J. M.: COVID-19 lockdowns drive decline in active fires in southeastern United States, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 118, e2105666118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2105666118, 2021.

Putaud, J.-P., Van Dingenen, R., Alastuey, A., Bauer, H., Birmili, W., Cyrys, J., Flentje, H., Fuzzi, S., Gehrig, R., and Hansson, H.-C.: A European aerosol phenomenology–3: Physical and chemical characteristics of particulate matter from 60 rural, urban, and kerbside sites across Europe, Atmos. Environ., 44, 1308–1320, 2010.

Putaud, J.-P., Pisoni, E., Mangold, A., Hueglin, C., Sciare, J., Pikridas, M., Savvides, C., Ondracek, J., Mbengue, S., Wiedensohler, A., Weinhold, K., Merkel, M., Poulain, L., van Pinxteren, D., Herrmann, H., Massling, A., Nordstroem, C., Alastuey, A., Reche, C., Pérez, N., Castillo, S., Sorribas, M., Adame, J. A., Petaja, T., Lehtipalo, K., Niemi, J., Riffault, V., de Brito, J. F., Colette, A., Favez, O., Petit, J.-E., Gros, V., Gini, M. I., Vratolis, S., Eleftheriadis, K., Diapouli, E., Denier van der Gon, H., Yttri, K. E., and Aas, W.: Impact of 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns on particulate air pollution across Europe, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 10145–10161, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-10145-2023, 2023.

Puxbaum, H., Caseiro, A., Sánchez-Ochoa, A., Kasper-Giebl, A., Claeys, M., Gelencsér, A., Legrand, M., Preunkert, S., and Pio, C.: Levoglucosan levels at background sites in Europe for assessing the impact of biomass combustion on the European aerosol background, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 112, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008114, 2007.

Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Pey, J., Cusack, M., Pérez, N., Mihalopoulos, N., Theodosi, C., Gerasopoulos, E., Kubilay, N., and Koçak, M.: Variability in regional background aerosols within the Mediterranean, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4575–4591, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4575-2009, 2009.

Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Pandolfi, M., Reche, C., Pérez, N., Minguillón, M. C., Moreno, T., Viana, M., Escudero, M., Orio, A., Pallarés, M., and Reina, F.: 2001–2012 trends on air quality in Spain, Sci. Total Environ., 490, 957–969, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.074, 2014.

Saraga, D., Maggos, T., Degrendele, C., Klánová, J., Horvat, M., Kocman, D., Kanduč, T., Garcia Dos Santos, S., Franco, R., Gómez, P. M., Manousakas, M., Bairachtari, K., Eleftheriadis, K., Kermenidou, M., Karakitsios, S., Gotti, A., and Sarigiannis, D.: Multi-city comparative PM2.5 source apportionment for fifteen sites in Europe: The ICARUS project, Sci. Total Environ., 751, 141855, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.141855, 2021.

Savadkoohi, M., Pandolfi, M., Reche, C., Niemi, J. V, Mooibroek, D., Titos, G., Green, D. C., Tremper, A. H., Hueglin, C., and Liakakou, E.: The variability of mass concentrations and source apportionment analysis of equivalent black carbon across urban Europe, Environ. Int., 178, 108081, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108081, 2023.

Sciare, J., Oikonomou, K., Cachier, H., Mihalopoulos, N., Andreae, M. O., Maenhaut, W., and Sarda-Estève, R.: Aerosol mass closure and reconstruction of the light scattering coefficient over the Eastern Mediterranean Sea during the MINOS campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 2253–2265, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-2253-2005, 2005.

Sciare, J., Oikonomou, K., Favez, O., Liakakou, E., Markaki, Z., Cachier, H., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Long-term measurements of carbonaceous aerosols in the Eastern Mediterranean: Evidence of long-range transport of biomass burning, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 5551–5563, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-5551-2008, 2008.