the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Mid- and far-infrared spectral signatures of mineral dust from low- to high-latitude regions: significance and implications

Claudia Di Biagio

Elisa Bru

Avila Orta

Servanne Chevaillier

Clarissa Baldo

Antonin Bergé

Mathieu Cazaunau

Sandra Lafon

Sophie Nowak

Edouard Pangui

Meinrat O. Andreae

Pavla Dagsson-Waldhauserova

Kebonyethata Dintwe

Konrad Kandler

James S. King

Amelie Chaput

Gregory S. Okin

Stuart Piketh

Thuraya Saeed

David Seibert

Zongbo Shi

Earle Williams

Pasquale Sellitto

Paola Formenti

Mineral dust absorbs and scatters solar and infrared radiation, thereby affecting the radiance spectrum at the surface and top-of-atmosphere and the atmospheric heating rate. While half of the outgoing thermal radiation is emitted in the far infrared (FIR, 15–100 µm), knowledge of the optical properties and thermal radiative effects of dust is currently limited to the mid-infrared region (MIR, 3–15 µm). In this study we performed pellet spectroscopy measurements to evaluate the MIR and FIR contribution to dust absorbance and explore the variability and spectral diversity of the dust signature within the 2.5–25 µm range. Thirteen dust samples re-suspended from parent soils with contrasting mineralogy were investigated, including low and mid latitude dust (LMLD) sources in Africa, America, Asia, and Middle East, and high latitude dust (HLD) from Iceland. Results show that the absorbance of dust in the FIR up to 25 µm is comparable in intensity to that in the MIR. Also, spectrally different absorption (position and shape of the peaks) is observed for Icelandic dust compared to LMLD, due to differences in mineralogical composition. Corroborated with the few available literature data on absorption properties of natural dust and single minerals up to 100 µm wavelength, these data suggest the relevance of MIR and FIR interactions to the dust radiative effect for low to high latitude sources. Furthermore, the dust spectral signatures in the MIR and FIR could potentially be used to characterise the mineralogy and differentiate the origin of airborne particles based on infrared remote sensing observations.

- Article

(2393 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1460 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Mineral dust is one of the most abundant aerosol species in the Earth's atmosphere with far reaching implications in the climate system (Knippertz and Stuut, 2014; Kok et al., 2023). Over 4000 Tg of dust are emitted annually from low and mid-latitude large deserts in Africa, Asia, America, and the Middle East, here referred as LMLD (low and mid latitude dust) (Ginoux et al., 2012; Gliß et al., 2021; Kok et al., 2021, 2023). In addition, new high latitude dust (HLD) sources are progressively emerging in response to glacier and snow retreat due to global warming and contribute to dust load especially in the Arctic (Bullard et al., 2016; Meinander et al., 2022, 2025).

Mineral dust aerosols strongly affect the radiative budget at local, regional and global scale via scattering and absorption of both solar (0.2–3 µm) and infrared (3–100 µm) radiation (Li et al., 2004; di Sarra et al., 2011; Slingo et al., 2006; Song et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2009). The capacity of dust to interact with radiation throughout the atmospheric spectrum is due to its extended size distribution, including particles from hundreds of nanometres to several tenths of micrometres (Formenti and Di Biagio, 2024; Ryder et al., 2013), and its mineralogical composition, including silicates, carbonates and iron oxides (Formenti et al., 2014b; Jeong, 2008) showing multiple absorption bands across the shortwave to infrared spectral range (Sokolik and Toon, 1999). In particular, strong infrared absorption is identified due to the resonance peaks of quartz, clays (illite, kaolinite, smectite), and calcite (Di Biagio et al., 2014b, 2017; Hudson et al., 2008b, a; Sokolik and Toon, 1999). The absorption in the infrared contributes to a positive dust direct radiative effect (DRE) at TOA, which opposes and counteracts a significant part of the dust negative DRE resulting from the dominant scattering at solar wavelengths (Christopher and Jones, 2007; di Sarra et al., 2011; Song et al., 2022).

Recent modelling efforts including state-of-the-art representation of dust size distribution and spectral scattering and absorption from the ultraviolet to the mid-infrared MIR (3–15 µm) suggest that at the global and annual scale the dust-radiation interactions in the infrared can counteract a significant fraction and even fully offset the negative DRE at TOA (Di Biagio et al., 2020; Kok et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2024). However, although the spectral range within 15–100 µm, referred to as far infrared (FIR), is also of great relevance for the Earth's radiative budget, as about half of thermal radiation re-emitted by the Earth and atmosphere towards space falls within this spectral range (e.g., Harries et al., 2008), the state of current knowledge is limited to the MIR range, since the dust absorption signature and refractive index above 15 µm in the FIR remain unexplored.

A better knowledge of dust-radiation interactions in the FIR is key to fully understand, model and predict the role of dust aerosols on the Earth's radiative budget, as well as for exploiting current and future satellite missions measuring in the MIR and FIR. Indeed, the interaction of dust with infrared radiation modifies the radiance flux spectrum at the surface and the TOA, therefore making particles detectable from space-borne and ground-based remote sensing sensors working at different spectral ranges. Provided with accurate input data on particle spectral complex refractive index, remote sensing instruments can use atmospheric observations in presence of suspended dust to get information on dust layers' physico-chemical properties, such as their size distribution, optical depth and 3D distributions of these properties (Capelle et al., 2014; Cuesta et al., 2015, 2020; Vandenbussche et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2022, 2023, 2024). Recent studies have also tested the possibility to retrieve information on the mineralogical composition of dust based on its infrared signature (e.g., Di Biagio et al., 2023). On the other hand, the inaccuracy of inversion algorithms in representing the infrared spectral signature of dust aerosols can induce misinterpretations and biases in the retrieval from space of other climate-relevant parameters, such as the temperature profile and sea surface temperature (Luo et al., 2019; Maddy et al., 2012).

In this study, we present measurements of the absorbance spectrum of mineral dust in the spectral range from 2–25 µm. Results are analysed with a twofold objective: first, we experimentally investigate the significance of MIR versus FIR dust interactions; secondly, we explore the spectral signatures of dust originating from source areas with differing mineralogical compositions. In particular, we aim to assess the global-scale variability of dust extinction beyond the relatively well-known MIR range and to highlight the differences or similarities between LMLD and HLD aerosols. For this purpose, thirteen dust samples from globally distributed sources are investigated. These include eleven LMLD samples from Northern and Southern Africa (Morocco, Niger, Chad, Namibia, Botswana), North and South America (Arizona, Chile), Middle East (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait), and Asia (China), and two HLD samples from northern Europe (Iceland).

This paper is relevant to the forthcoming FIR satellite missions, like the Far-infrared Outgoing Radiation Understanding and Monitoring (FORUM), which will measure for the first time the Earth's spectrum in the FIR up to 100 µm at high spectral resolution (Palchetti et al., 2020), and their synergy with MIR observing systems, such as the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) and IASI New Generation (IASI-NG) (Crevoisier et al., 2014).

This study is based on a pellet spectroscopy technique that consists in dispersing the aerosol particles in a matrix of transparent material which is then pressed to form a homogeneous pellet. The transmission spectrum of the pellet is measured to obtain the absorbance of the aerosol sample. To apply this technique the dust aerosols were resuspended in the laboratory from natural soil samples.

2.1 Parent soil selection and origin

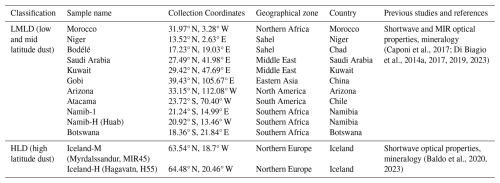

The thirteen soil and sediment samples in this study (Table 1) were selected with the aim of representing the global scale variability of particle mineralogy. Samples, collected from different source areas worldwide, represent a depth of the first millimetres of the surface. Many of the samples had already been analysed in past laboratory studies, including simulation chamber experiments to investigate their physical, chemical and spectral optical properties at solar and MIR wavelengths (Baldo et al., 2020, 2023; Caponi et al., 2017; Di Biagio et al., 2014a, 2017, 2019, 2023).

For Northern Africa, we selected a soil from Morocco in the Northern Sahara and two samples from the Sahel, one in Niger and one in Chad (sediment from the Bodélé depression). These are important sources for medium and long-range dust transport towards the Mediterranean (Israelevich et al., 2002) and the Atlantic Ocean (Prospero et al., 2002; Reid et al., 2003). In particular, the Bodélé depression is one of the most active sources at the global scale (Goudie and Middleton, 2001; Washington et al., 2003). The two soils from the Middle East are from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, which are important sources of dust to the Red and the Arabian seas (Prospero et al., 2002) and the North Indian Ocean (Leon and Legrand, 2003). For the second largest global source of dust, Eastern Asia, we studied one sample from the Gobi desert. For North and South America, soils were collected in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona and the Atacama Desert in Chile. The Sonoran Desert is a permanent source of dust in North America, the Atacama Desert is the most important source of dust in South America (Ginoux et al., 2012). For Southern Africa, we selected two soils from the Namib desert, one from the area between the Kuiseb and Ugab valleys (Namib-1, already studied in Di Biagio et al., 2017, 2019) and the other from the Huab ephemeral river bed (Namib-Huab), both of which are sources of dust transported towards the South-Eastern Atlantic (Vickery et al., 2013). A sample from Botswana was also selected, as an additional source from Southern Africa (Bhattachan et al., 2013, 2015). Surface sediment samples collected from two major dust hotspots in Iceland (H55, Hagavatn, and MIR45, Mýrdalssandur), which significantly contribute to the total dust emissions from this region (Arnalds et al., 2016), were also investigated. Iceland is the major documented emitting HLD source so far (Meinander et al., 2022).

2.2 Resuspension and collection of dust aerosols from natural parent soils

Dust aerosols were re-suspended in the laboratory by mechanical shaking of the parent soil samples using the same protocol previously described by Di Biagio et al. (2017) and Baldo et al. (2023). To this aim, 5 g of soil sample (previously sieved at 1000 µm and heated at 100 °C for about 1 h) were placed in a Büchner flask and shaken at 100 Hz by means of a sieve shaker (Retsch AS200). The dust suspension in the flask was entrained by a pure N2 flow at 5 L min−1 to a glass vial where the dust aerosol was collected. The collection time lasted for about 1 h, whilst continuously shaking the soil, in order to collect around 1–2 mg of dust aerosols.

2.3 Dust pellet preparation

Infrared transmission spectroscopy was performed by means of the pellet technique (Di Biagio et al., 2014b; Volz, 1972) using Potassium Bromide (KBr for IR spectroscopy Uvasol®, CAS No 7758-02-3, lot. B1978207 142) as transparent matrix in which dust grains collected from soil resuspension were dispersed. Pellet spectroscopy has various limitations and uncertainties to represent the optical behaviour of suspended aerosols, as discussed by Di Biagio et al. (2014b), however it represents a reference technique to explore the infrared optical properties of aerosols and their components, without the complication of resuspension processes. A quantity of 0.5 mg of dust was weighed and diluted in 300 mg of KBr (corresponding to 0.16 % of dust in KBr). Dust and KBr were weighed by means of a Mettler Toledo microbalance XPR26C whose maximum sensitivity is 1 µg. The dust-KBr mixture was mechanically shaken for few minutes to create a homogeneous mixing and slightly ground with an agate mortar. The obtained dust-KBr mixture was placed in the oven to dry at the temperature of 110 °C for at least 2 h and then pressed at ∼9.5 t cm−2 for 2 min to form a thin pellet. A quantity of 300.5 mg of powder (300 mg KBr plus 0.5 mg dust) was used to create a homogeneous pellet of 13 mm diameter (surface 1.33 cm2) and about 1 mm thickness. All laboratory manipulations were accomplished in clean conditions in an ISO7 room. A number of 2 to 3 pellets were produced per sample depending on the amount of the collected dust aerosols (with the exception of Arizona for which only 1 pellet could be produced), to test the repeatability of the procedure, for a total of 31 pellets. Additionally, six pure 300 mg KBr pellets were produced. All the pellets were kept in the oven at 110 °C until they were used for spectroscopy measurements in order to minimize water vapour absorption on their surface.

2.4 Infrared pellet spectroscopy

Absorbance spectra were recorded between 2.5–25 µm (4000–400 cm−1 wavenumber) at 0.5 cm−1 resolution by means of a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two FT-IR spectrometer. The instrument uses a Globar source, with a KBr beamsplitter and a deuterated triglycine sulphate (DTGS) detector. Pellets were placed in the spectrometer chamber. A background spectrum was acquired prior each pellet measurement and subtracted to remove the signatures of CO2 and H2O possibly present in the cell. A total of 10 scans were averaged to produce the dust-KBr and the pure KBr spectra, respectively. Within the 6 spectra of pure KBr, two showed slight contamination by dust grains in the pellet and were removed from the dataset. The other 4 pure KBr spectra did not show any indication of contamination, but showed a slightly different spectral variation particularly at low wavelengths (<5 µm), which we attribute to some degree of water vapour absorption by the highly hygroscopic KBr occurring during the pellet production, which was performed at ambient pressure instead of standard vacuum conditions. To take this effect into account, each dust-KBr spectrum was corrected by subtracting the pure KBr spectrum that best fit the baseline of each dust-KBr pellet. All the collected raw spectra for KBr and dust are shown in Figs. S1–S5 in the Supplement. The uncertainty in the measured absorbance is less than 5 % and has been estimated as the 3σ variability of the signal in the regions of no dust absorption (A<0.01).

The pellet absorbance spectra acquired in this study are compared against in-situ absorbance spectra measured on suspended aerosols in a simulation chamber from the same LMLD source soils by Di Biagio et al. (2017) (Fig. S6, Text S1 in the Supplement). The comparison shows that the shape of the dust absorption in the 8–15 µm common spectral range is similar between pellets and suspended aerosols. Only the quartz band is in some cases overestimated in the pellet spectra. This is likely due to the presence of some grains of soils, much richer in quartz than the aerosols (Fig. 18 in Adebiyi et al., 2023), that were entrained together with the aerosol and therefore included in the pellet. This potential artefact, however, does not seem to influence the spectra in other regions within the 8–15 µm.

2.5 Dust mineralogical composition

The identification and quantification of the main mineral phases composing the dust aerosol particles was performed by X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) and X-ray Absorption Near-Edge Structure (XANES) analyses (Formenti et al., 2014b, a). These were performed on dust samples collected on polycarbonate filters and re-suspended applying the same generation procedure as described in Sect. 2.2. Data acquisition and analysis was presented in previous studies (Baldo et al., 2020, 2023; Caponi et al., 2017; Di Biagio et al., 2017, 2019). More detailed information on measurement procedures is provided in Text S2 in the Supplement.

3.1 Mineralogical composition of LMLD and Icelandic dust samples

The mineralogy of the thirteen analysed samples is illustrated in Fig. 1 and reported in Table S1 in the Supplement. The eleven LMLD samples are composed of varying proportions of clays (illite, kaolinite, chlorite, palygorskite, muscovite; 45.5 %–75.6 % by mass), quartz (3.5 %–36.7 %), feldspars (orthoclase, albite, microcline; 2.2 %–26 %), calcite (2.0 %–21.7 %) and iron oxides (hematite, goethite; 0.7 %–5.8 %). Iron oxides are identified in different proportions of goethite and hematite in all LMLD, except for Botswana for which no iron oxides are detected (based only on XRD analysis for this sample). Calcite is found in all samples with the exception of Niger, Bodélé and Botswana. Dolomite is detected only in the Morocco dust.

Figure 1Mineralogy of the thirteen aerosol samples considered in this study. The mass apportionment between the different clay species (illite, kaolinite, chlorite) for Morocco, Niger, Bodélé, and Gobi aerosols is based on literature values of the illite-to-kaolinite and chlorite-to-kaolinite mass ratios as discussed in Di Biagio et al. (2017), while retrieved from XRD spectra analysis for Namib-H and Botswana. For the other samples only the total clay mass is reported. The carbonates include calcite and dolomite. Iron oxides include hematite, goethite and magnetite.

As discussed by Baldo et al. (2020), a contrasting mineralogy is obtained for the Icelandic dust samples compared to LMLD. The Iceland-M dust is mostly composed of amorphous glass material (91.3 %), feldspars (anorthite; 3.5 %) and pyroxene (augite; 3.6 %), while Iceland-H is made of feldspars (anorthite, microcline; 53.0 %), pyroxene (augite; 29.3 %), olivine (forsterite; 7.2 %) and minor contribution of amorphous glass (8.0 %). Both Icelandic samples show the presence of iron oxides in the form of magnetite (1.4 %–2.0 %) with lower contributions of hematite and goethite (0.2 %–0.5 %) by XRD and Fe sequential extraction techniques. These observations are in line with analysis from same source areas in Iceland (González-Romero et al., 2024).

3.2 Different infrared absorbance signatures in the 2.5–25 µm spectral range for LMLD versus Icelandic dust

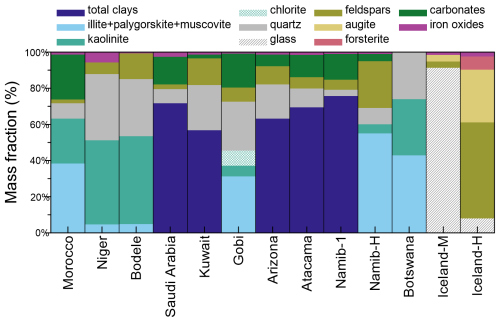

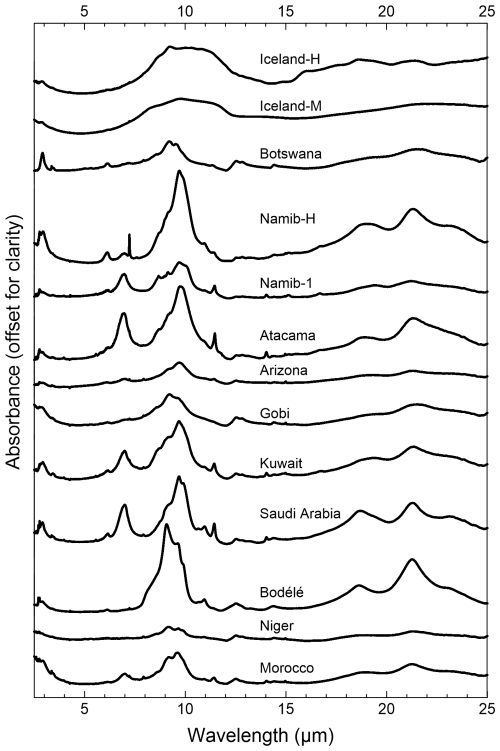

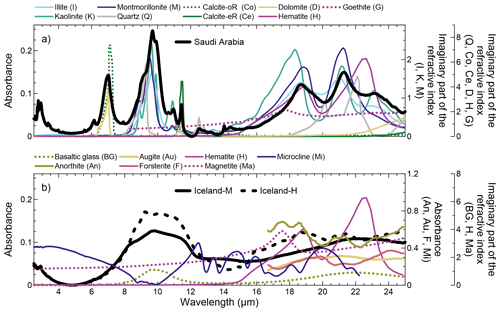

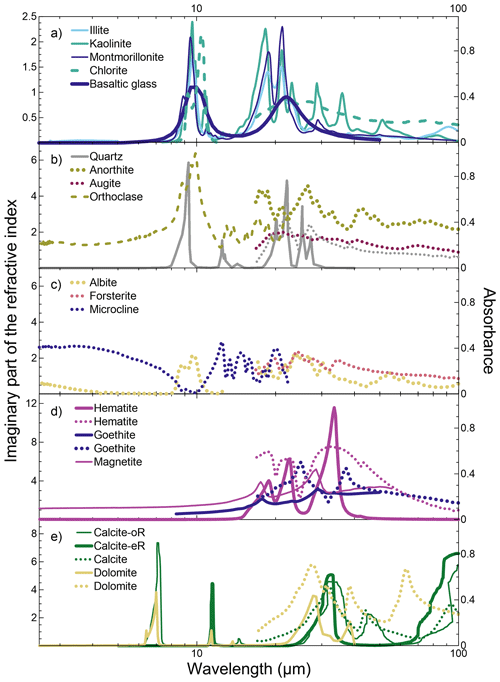

The absorbance spectra measured in the 2.5–25 µm range for the thirteen LMLD and the Icelandic dust samples are shown in Fig. 2. The comparison between dust absorbance and single mineral spectra is provided in Fig. 3 for Saudi Arabia, taken as an illustrative case for LMLD due to the presence of absorption signatures from multiple minerals in its spectrum, and for Iceland-H and Iceland-M for HLD.

Figure 2Absorbance spectra measured in the spectral range 2.5–25 µm for the thirteen different dust samples in this study. Spectra are offset for improving readability. All spectra are plotted at the same scale of absorbance (0–0.4 range), with the exception of Namib-H (0–0.6 range) and Bodélé (0–1.2 range). An alternative version of the figure where spectra are over-plotted is shown in Fig. S7 in the Supplement.

Figure 3Absorbance spectra measured within the spectral range 2.5–25 µm for the (a) Saudi Arabia and (b) Iceland-M and Iceland-H samples compared to the spectra of single minerals composing dust. Data for single minerals are reported as the imaginary part of the complex refractive index or absorbance spectra. The peaks in both refractive index and absorbance spectra indicate the position of main absorption bands for the mineral. References for the plotted curves and main information on single mineral data shown in this figure are provided in Table S2. The band centre wavelengths for all identified mineral absorption peaks are provided in Table S3.

As depicted in Figs. 2 and 3, the absorbance spectra show large sample-to-sample variability which reflects the diversity in terms of mineral content and speciation. A marked difference is observed for the Icelandic dust compared to the LMLD samples both in respect of the position and shape of the absorption bands. The largest absorbance peaks are found for both LMLD and Icelandic dust in the 6–12 µm and 15–25 µm regions due to the superposing contribution of multiple minerals, such as clays, quartz, carbonates and iron oxides (hematite, goethite) for LMLD and basaltic glass, feldspars, augite, forsterite and iron oxides (magnetite) for Icelandic dust. A full list of peak positions for single minerals are provided in Table S3 in the Supplement. Note that below 5 µm the absorbance signal shows an increase for decreasing wavelength for most of the samples, which is due to the combined effect of clay absorption around 2.8 µm and residual KBr signal not completely removed through baseline correction.

All LMLD samples display strong spectral signatures associated with clays between 9–11 µm, but the position and relative intensity of the peaks vary with clay speciation. The prevalence of kaolinite is reflected for instance in the presence of the double peaks at 9.7 and 9.9 µm and the secondary peak at 10.9 µm, as identified in the Niger and Bodélé samples. Conversely, a broader single peak located between 9.5–9.7 µm is identified for samples (i.e., Morocco, Arizona, Atacama, Namib-H) composed of different proportions of clay minerals (illite, kaolinite, montmorillonite, palygorskite, muscovite). The presence of quartz is associated in LMLD with a main absorption band at 9.3 µm, which induces the appearance of a more or less pronounced shoulder in the clay bands, and a secondary double peak at 12.5 and 12.8 µm, as clearly identified in the Niger, Bodélé, Gobi, Kuwait, Arizona and Botswana samples, where quartz content is the highest (18.9 %–36.9 % in mass). An additional region of intense absorption for LMLD is found in the 6.5–7.5 µm range associated with the specific features of carbonates (calcite, dolomite) also showing a secondary less intense peak at ∼11.4 µm. The intensity of the main calcite band at 7 µm band follows the trend in calcite content (see Table S1) but it is not always proportional to it. This could suggest that differences in size-dependent mineralogy between the different samples can affect the intensity of the absorption bands, as also discussed in Di Biagio et al. (2014b).

Three main broad peaks are identified for all LMLD samples above 15 µm. These are contributed by superimposing bands for the different clay species between 18–23 µm, together with those of quartz (two bands centred at ∼20 and 22 µm) and iron oxides (two large bands centred at ∼19 and 23 µm for hematite, and one at ∼18 µm for goethite).

For the Iceland-M sample dominantly composed of amorphous silicate (91.3 %), the spectrum is mainly shaped by the two broad absorption bands of amorphous glass centred at 9.5 and 22 µm. A third band at 14 µm is identified and potentially associated with anorthite (Salisbury et al., 1987, 1991, data not shown). For the Iceland-H sample several absorption bands of anorthite (representing about half of the mass for this sample) are identified, with the absorption peaks centred at 18.7, 21.4, and 26.5 µm. Microcline, augite, forsterite, and magnetite also contributed to the spectral absorbance above 17 µm and different absorption peaks of these minerals are identified, as shown in Fig. 3. The amorphous material contributes to absorption in the 8–12 µm region and above 15 µm. Small peaks are also detected in the 8–12 µm range but due to the scarcity of information on single mineral spectra, no specific attribution is possible.

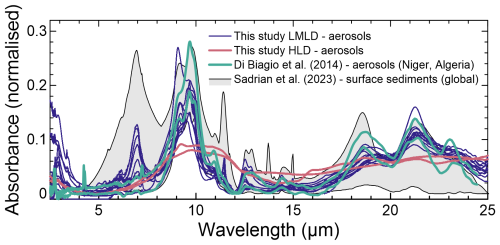

The spectral diversity of Icelandic dust samples evidenced in this study is supported also by comparison with LMLD from literature data (Di Biagio et al., 2014b; Sadrian et al., 2023), confirming the different optical signatures between low, mid and high-latitude dust. This is shown in Fig. 4 where absorbance measurements in this study are combined with literature data on pellet dust samples from worldwide locations in the 2.5–25 µm spectral range. Data include the work by Di Biagio et al. (2014b) providing measurements for five natural dust aerosol samples originated from Niger and Algeria and collected at the ground-based sites of Banizoumbou (Niger) and Tamanrasset (Algeria) in 2006 during the AMMA campaign (African Multidisciplinary Monsoon Analysis) (Formenti et al., 2011; Rajot et al., 2008). Further spectroscopic data for 26 samples from diverse locations in USA (Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah), Africa (Chad, Botswana, Djibouti, Mali, Namibia), Spain (Las Canarias), Arabian Peninsula (Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia), and Central and eastern Asia (Afghanistan, China) are provided by Sadrian et al. (2023). The Sadrian et al. (2023) dataset refers to surface soil samples sieved at 38 µm instead of aerosols. Figure 4 further illustrates the variability in the dust spectral signature across the 2.5–25 µm spectral range for dust of additional diverse geographic origin. The LMLD samples in the present work exhibit a spectral variability that is within the one identified in past studies and particularly in Sadrian et al. (2023).

Figure 4Comparison of the absorbance spectra obtained in this study for LMLD (blue lines) and Icelandic HLD (red lines) and the pellet data obtained in Di Biagio et al. (2014b) for natural aerosols in from Niger and Algeria (green lines) and in Sadrian et al. (2023) for global surface sediments (grey shaded area). The two datasets shown for Di Biagio et al. (2014b) represent the minimum and maximum of the absorbance measured in that study. Similarly, the shaded area envelopes the range of absorbance in Sadrian et al. (2023). To facilitate the comparison, all data are normalized so that the integral of the absorbance is 1 in the 5–25 µm range.

3.3 Relevance of MIR and FIR absorbance for LMLD and Icelandic dust

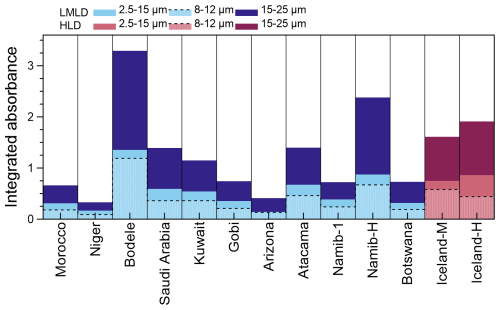

The integral of the absorbance signal in the 2.5–25 µm range for the LMLD and Icelandic HLD investigated in this study and the contributions by the MIR (2.5–15 µm) and the FIR (15–25 µm) ranges are shown in Fig. 5. The integrated spectrum in the 8–12 µm region is also shown, as it corresponds to the MIR atmospheric window, where absorption by atmospheric gases is relatively low, therefore of interest for atmospheric radiative transfer as most of the dust MIR signal is in this region.

Figure 5Integral of the absorbance signal in the 2.5–25 µm range for the LLMD and Icelandic HLD investigated in this study. The contributions by the MIR (2.5–15 µm), the FIR (15–25 µm) and the 8–12 µm region (area below the dashed line) are shown.

The integrated absorbance in the 2.5–25 µm range is within 0.33 and 3.29 for LMLD and 1.61–1.91 for Icelandic dust. The MIR contributes by 35 %–53 % (LMLD) and 45 %–47 % (HLD) to total absorbance, mostly within the 8–12 µm region, while the FIR contribution is within 47 %–65 % (LMLD) and 53 %–55 % (HLD), representing more than half of the total integrated absorbance.

Literature data on natural dust samples in Fig. 4 also confirm the relevance of the FIR absorbance for dust of varying origin. The integrated absorbance in the 2.5–25 µm is within 0.44 and 1.0 for the samples in Di Biagio et al. (2014b), and within 0.41 and 5.50 (with an average value of 1.7±1.2) in the 4–25 µm for the 26 samples in Sadrian et al. (2023). The FIR signal above 15 µm contributes 50 %–60 % of the integrated absorbance in Di Biagio et al. (2014b), and 28 %–63 % in Sadrian et al. (2023). Only one sample in Sadrian et al. (2023) displays a low contribution of the FIR (5 %) to the absorbance signal.

The few existing pellet spectroscopic measurements of natural dust aerosols beyond 25 µm (Fouquart et al., 1987; Volz, 1972, 1973), despite not allowing to explore the diversity of dust absorption from global sources, support anyhow the presence of a significant absorption signal continuously up to 40 µm (Fig. S8). These data were acquired at low spectral resolution and correspond to rainout dust samples collected in Germany (Volz, 1972), Saharan dust from Barbados (Volz, 1973) and Niger dust (Fouquart et al., 1987).

The relevance of dust absorption in the FIR for sources of varying mineralogy is further evidenced when looking at the spectra of single minerals composing LMLD and Icelandic HLD. Literature data of the imaginary part of the refractive index or absorbance spectra for single dust minerals extending through the FIR range up to 100 µm are shown in Fig. 6. Information on the datasets and the band centre wavelengths for all identified mineral absorption peaks are provided in Tables S2 and S3. As shown in Fig. 6, all minerals show multiple and often superposing absorption bands in the 25–100 µm wavelength range, therefore supporting the relevance of dust-radiation interaction in the FIR well beyond 25 and 40 µm, as measured for natural dust samples. The strongest peaks above 25 µm are identified for clays (kaolinite, illite; 28.8, 36.2, 51.3, 91.7 µm), iron oxides (hematite, goethite, magnetite; 22.6, 28.6, 29.1, 33.5, 37.3 µm), and carbonates (calcite, dolomite; 28.5, 33.0, 38.5, 45.9, 64.0 µm). Feldspars (albite, orthoclase, anorthite), pyroxene (augite), and olivine (forsterite) show several absorption peaks in the broad range 26–77 µm. The intensity of the absorption peaks is of comparable intensity, and in some cases higher, than those below 25 µm, particularly for hematite, calcite and dolomite.

Figure 6Imaginary refractive index and absorbance spectra within the spectral range 5–100 µm for individual minerals composing low and high latitude dust. References for the plotted curves are provided in Table S2. Data are either reported as imaginary refractive index (continuous lines) or absorbance spectra (dashed or dotted lines). Original data for orthoclase (b) and albite (c) have been scaled to ease comparison.

On the other hand, for several minerals such as basaltic glass, quartz and microcline, information is lacking in the FIR. Figure 6, while showing the potential relevance of dust absorption throughout the FIR domain, also highlights the paucity of spectral data available for single dust mineral components, which sum up to the low available information for natural dust. For most of minerals, the data do not cover the full infrared spectral range, being limited either to the MIR or to part of the FIR. Information on the complex refractive index are available only for some minerals, while no data exist for feldspars, pyroxene and olivine. Almost all data available have been acquired for compressed pellets or often crystals, so they provide limited representativeness for suspended dust.

3.4 Implications for dust direct radiative effect and infrared remote sensing

The results from this study show that the absorbance of dust in the FIR up to 25 µm is comparable in intensity to that in the MIR. These observations highlight the potential contribution of FIR interactions to the total dust direct radiative effect for low to high latitude dust sources. As a matter of fact, the FIR range is at present not specifically considered in model simulations due to the lack of knowledge of the dust optical properties at these wavelengths. However, it can be climatically relevant in different regions, notably dry areas and the upper troposphere, as well as high latitudes where infrared radiation control the radiative budget over large part of the year.

Another observation from the present analysis is the comparable intensity of the infrared absorbance, both in the MIR, FIR and the 8–12 µm window, for the Icelandic HLD compared to the LMLD samples. The integrated absorbance of HLD is indeed at the upper end of that measured for low and mid-latitude dust (Fig. 5). In a previous study, Baldo et al. (2023) estimated that Icelandic dust absorption in the solar range (370–590 nm) is at the upper end of typical values for LMLD as reported by Di Biagio et al. (2019), while in the near infrared (660–950 nm) the absorption by Icelandic dust is up to 2–8 times higher than most of dust aerosols from northern Africa and Asia. The results from Baldo et al. (2023) combined with observation from this work suggest the relevance of dust-radiation interaction for Icelandic dust across the whole atmospheric spectrum.

Data from this study also highlight the variability of dust spectral absorbance as measured up to 25 µm for dust of diverse origin and composition, particularly when contrasting LMLD versus Icelandic HLD types. Specific minerals are identified to modulate the intensity and the spectral variation of dust absorption bands, producing characteristic spectral signatures for LMLD (clays, carbonates, quartz, iron oxides) and Icelandic dust (amorphous silicate, anorthite, microcline, augite, forsterite). This suggests that the spectral signature of dust in the MIR and FIR could be used to identify mineralogical composition for different dusts, which can be used to differentiate the origin of airborne particles based on remote sensing infrared observations, such as those from IASI/IASI-NG and FORUM. Single mineral spectra also suggest the presence of additional specific mineral signatures beyond 25 µm, which supports further possibilities to detect and characterise global dust from ground-based and space-borne hyperspectral remote sensing observations in the FIR. Indeed, as demonstrated in Di Biagio et al. (2023), infrared spectral signatures can be used to derive quantitative information of dust mineralogy, which enables to distinguish dust sources and potentially follow dust plume evolution transport in the atmosphere. A specific analysis of the sensitivity of MIR and FIR remote sensing to dust aerosols is provided by Sellitto et al. (2025).

In this work we explored the dust spectral signature and sample-to-sample variability of absorbance in the infrared region including the MIR and the FIR up to 25 µm. To this aim we investigated thirteen aerosol samples generated in the laboratory from surface soils and sediments originated from global dust source regions including both low, mid and high-latitude dust source areas from four continents (Africa, Asia, America, Europe).

The analysis of absorbance spectra acquired in the present study, corroborated with past literature results on natural dust and single minerals, evidences the significance of dust-radiation interactions in the infrared range for both LMLD and Icelandic dust and the relevant contribution of the FIR to total dust infrared absorption. The FIR is estimated to represent up to 65 % of total infrared absorbance as measured up to 25 µm in the present work. However its consideration in radiative transfer models is hampered by lack of data on dust optical properties in this spectral range. Extending investigation of the dust spectral optical properties (absorbance spectra, mass absorption and extinction cross section, complex refractive index) to the FIR is necessary to improve the understanding of the role of dust in the radiative transfer and in the regional and planetary radiative budget. New knowledge should include both natural dust samples and single minerals composing dust, as for both the knowledge is scarce and as both are relevant to improve representation of dust in regional and global models (Gómez Maqueo Anaya et al., 2024; Gonçalves Ageitos et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Obiso et al., 2024; Scanza et al., 2015). Future measurements should preferentially focus on suspended natural samples instead of pellets, or even crystal samples as for single minerals, to represent closely the natural state of mineral dust aerosols.

Our results also put in evidence the diversity in infrared spectral signature for Icelandic HLD samples compared to LMLD due to differences in mineralogical composition. These differences are of particular significance for remote sensing applications as they suggest the possibility to distinguish the composition and the origin of dust based on infrared hyperspectral observations. It is worth noting that the present analysis is limited to two Icelandic dust sources only, as Iceland is one of the strongest sources of dust at high latitudes identified so far (Arnalds et al., 2016; Dagsson-Waldhauserova et al., 2017; Meinander et al., 2022). Previous studies have also focussed on Icelandic dust highlighting differences in its composition and optical behaviour at solar wavelengths compared to African and Asian dust (Baldo et al., 2020, 2023; González-Romero et al., 2024). The results in the present work, combined with these past studies, hence underscore the importance of extending investigation of HLD composition and spectral optical properties from other relevant sources of HLD in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, including Greenland, Canada, Svalbard, Patagonia, and Antarctica (Meinander et al., 2022, 2025). Although HLD represents only about 1 %–5 % of global dust emissions to date (Bullard et al., 2016; Meinander et al., 2022), the role of HLD in the polar environment is expected to progressively increase in the next years and decades, because of emissions increase in a warming climate due to both increasing exposure of natural sources (reduction of glaciers and ice– and snow–covered surfaces for a growing fraction of the year) and rising impact of anthropogenic activities (mines, road dust) (Thaarup et al., 2020). Ice core data show that there is a significant increase in Greenland dust loading since 2000, highly correlated with the local air temperature (Amino et al., 2021). As emphasized in Kok et al. (2023), model schemes should start explicitly account for dust emissions from high latitudes, and our results underline the need for source-specific characterization.

The retrieved absorbance spectra from this study are available at the EasyData data portal https://www.easydata.earth/#/public/home (last access: 16 January 2026) with the following doi number: https://doi.org/10.57932/905eff0b-d508-4aad-a422-5708e3132790 (Di Biagio et al., 2025). The single mineral spectra used in this study (Figs. 3 and 6) are available through original publications or open access repositories as listed in Table S2. The data from Sadrian et al. (2023) are available in the Supplement from their paper.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-1079-2026-supplement.

CDB, PF and PS designed the experiments and discussed the results. EB conducted the experiments with contributions by CDB, SC, AB, MC, and EP. EB and AO performed the data analysis of the pellet spectroscopy measurements under the supervision of CDB. EB, CDB, and PF collected single mineral data. CB, SL, and SN contributed to the mineralogical analyses. MOA, PDW, KD, KK, JSK, AC, GSO, SP, TS, DS, and ZS collected and shared the soil samples used for the experiments. PS, CDB, and PF provided funding acquisition and administration of the project. CDB wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Contributions to experimental work by Gael Noyalet, Manuela Cirtog, Marc David, Juan Cuesta, Stephane Alfaro, Bernadette Chatenet, Beatrice Marticorena, and Jean Louis Rajot at Laboratoire Interuniversitaire des Systemes Atmospehriques (LISA, UMR7583 CNRS) are gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by CNES through the project focused on FORUM mission, the French National program PNTS (Programme National de Télédétection Spatiale) through the IR-DUST project, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant nos. 416816480 and 417012665), and the Mitacs. This work has received funding from EU-PolarNet 2 via the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant no. 101003766).

This paper was edited by Markus Petters and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adebiyi, A., Kok, J. F., Murray, B. J., Ryder, C. L., Stuut, J.-B. W., Kahn, R. A., Knippertz, P., Formenti, P., Mahowald, N. M., Pérez García-Pando, C., Klose, M., Ansmann, A., Samset, B. H., Ito, A., Balkanski, Y., Di Biagio, C., Romanias, M. N., Huang, Y., and Meng, J.: A review of coarse mineral dust in the Earth system, Aeolian Res., 60, 100849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2022.100849, 2023.

Amino, T., Iizuka, Y., Matoba, S., Shimada, R., Oshima, N., Suzuki, T., Ando, T., Aoki, T., and Fujita, K.: Increasing dust emission from ice free terrain in southeastern Greenland since 2000, Polar Sci., 27, 100599, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2020.100599, 2021.

Arnalds, O., Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., and Olafsson, H.: The Icelandic volcanic aeolian environment: Processes and impacts – A review, Aeolian Res., 20, 176–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2016.01.004, 2016.

Baldo, C., Formenti, P., Nowak, S., Chevaillier, S., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Di Biagio, C., Doussin, J.-F., Ignatyev, K., Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., Arnalds, O., MacKenzie, A. R., and Shi, Z.: Distinct chemical and mineralogical composition of Icelandic dust compared to northern African and Asian dust, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 13521–13539, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-13521-2020, 2020.

Baldo, C., Formenti, P., Di Biagio, C., Lu, G., Song, C., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Doussin, J.-F., Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., Arnalds, O., Beddows, D., MacKenzie, A. R., and Shi, Z.: Complex refractive index and single scattering albedo of Icelandic dust in the shortwave spectrum, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2023-276, 2023.

Bhattachan, A., D'Odorico, P., Okin, G. S., and Dintwe, K.: Potential dust emissions from the southern Kalahari's dunelands, J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf., 118, 307–314, 2013.

Bhattachan, A., D'Odorico, P., and Okin, G. S.: Biogeochemistry of dust sources in Southern Africa, J. Arid Environ., 117, 18–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2015.02.013, 2015.

Bullard, J. E., Baddock, M., Bradwell, T., Crusius, J., Darlington, E., Gaiero, D., Gassó, S., Gisladottir, G., Hodgkins, R., McCulloch, R., McKenna-Neuman, C., Mockford, T., Stewart, H., and Thorsteinsson, T.: High-latitude dust in the Earth system, Rev. Geophys., 54, 447–485, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016RG000518, 2016.

Capelle, V., Chédin, A., Siméon, M., Tsamalis, C., Pierangelo, C., Pondrom, M., Crevoisier, C., Crepeau, L., and Scott, N. A.: Evaluation of IASI-derived dust aerosol characteristics over the tropical belt, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 9343–9362, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-9343-2014, 2014.

Caponi, L., Formenti, P., Massabó, D., Di Biagio, C., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Chevaillier, S., Landrot, G., Andreae, M. O., Kandler, K., Piketh, S., Saeed, T., Seibert, D., Williams, E., Balkanski, Y., Prati, P., and Doussin, J.-F.: Spectral- and size-resolved mass absorption efficiency of mineral dust aerosols in the shortwave spectrum: a simulation chamber study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 7175–7191, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-7175-2017, 2017.

Christopher, S. A. and Jones, T.: Satellite-based assessment of cloud-free net radiative effect of dust aerosols over the Atlantic Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027783, 2007.

Crevoisier, C., Clerbaux, C., Guidard, V., Phulpin, T., Armante, R., Barret, B., Camy-Peyret, C., Chaboureau, J.-P., Coheur, P.-F., Crépeau, L., Dufour, G., Labonnote, L., Lavanant, L., Hadji-Lazaro, J., Herbin, H., Jacquinet-Husson, N., Payan, S., Péquignot, E., Pierangelo, C., Sellitto, P., and Stubenrauch, C.: Towards IASI-New Generation (IASI-NG): impact of improved spectral resolution and radiometric noise on the retrieval of thermodynamic, chemistry and climate variables, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 7, 4367–4385, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-7-4367-2014, 2014.

Cuesta, J., Eremenko, M., Flamant, C., Dufour, G., Laurent, B., Bergametti, G., Höpfner, M., Orphal, J., and Zhou, D.: Three-dimensional distribution of a major desert dust outbreak over East Asia in March 2008 derived from IASI satellite observations, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 120, 7099–7127, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD022406, 2015.

Cuesta, J., Flamant, C., Gaetani, M., Knippertz, P., Fink, A. H., Chazette, P., Eremenko, M., Dufour, G., Di Biagio, C., and Formenti, P.: Three-dimensional pathways of dust over the Sahara during summer 2011 as revealed by new Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer observations, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc., 146, 2731–2755, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3814, 2020.

Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., Arnalds, O., and Olafsson, H.: Long-term dust aerosol production from natural sources in Iceland, J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc., 67, 173–181, https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2013.805703, 2017.

Di Biagio, C., Formenti, P., Styler, S. A., Pangui, E., and Doussin, J.-F.: Laboratory chamber measurements of the longwave extinction spectra and complex refractive indices of African and Asian mineral dusts, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 6289–6297, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL060213, 2014a.

Di Biagio, C., Boucher, H., Caquineau, S., Chevaillier, S., Cuesta, J., and Formenti, P.: Variability of the infrared complex refractive index of African mineral dust: experimental estimation and implications for radiative transfer and satellite remote sensing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 11093–11116, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-11093-2014, 2014b.

Di Biagio, C., Formenti, P., Balkanski, Y., Caponi, L., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Journet, E., Nowak, S., Caquineau, S., Andreae, M. O., Kandler, K., Saeed, T., Piketh, S., Seibert, D., Williams, E., and Doussin, J.-F.: Global scale variability of the mineral dust long-wave refractive index: a new dataset of in situ measurements for climate modeling and remote sensing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 1901–1929, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-1901-2017, 2017.

Di Biagio, C., Formenti, P., Balkanski, Y., Caponi, L., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Journet, E., Nowak, S., Andreae, M. O., Kandler, K., Saeed, T., Piketh, S., Seibert, D., Williams, E., and Doussin, J.-F.: Complex refractive indices and single-scattering albedo of global dust aerosols in the shortwave spectrum and relationship to size and iron content, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 15503–15531, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-15503-2019, 2019.

Di Biagio, C., Balkanski, Y., Albani, S., Boucher, O., and Formenti, P.: Direct Radiative Effect by Mineral Dust Aerosols Constrained by New Microphysical and Spectral Optical Data, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2019GL086186, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL086186, 2020.

Di Biagio, C., Doussin, J.-F., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Cuesta, J., Sellitto, P., Ródenas, M., and Formenti, P.: Infrared optical signature reveals the source-dependency and along-transport evolution of dust mineralogy as shown by laboratory study, Sci. Rep., 13, 13252, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39336-7, 2023.

Di Biagio, C., Bru, E., Orta, A.,, Chevaillier, S., Bergé, A., Cazaunau, M., Pangui, E., Sellitto, P., and Formenti, P.: Absorbance spectra of Mineral Dust from Low- to High-Latitude Regions in the Mid- and Far-Infrared spectral range (2.5–25 µm), EaSy Data [data set], https://doi.org/10.57932/905eff0b-d508-4aad-a422-5708e3132790, 2025.

di Sarra, A., Di Biagio, C., Meloni, D., Monteleone, F., Pace, G., Pugnaghi, S., and Sferlazzo, D.: Shortwave and longwave radiative effects of the intense Saharan dust event of 25–26 March 2010 at Lampedusa (Mediterranean Sea), J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016238, 2011.

Formenti, P. and Di Biagio, C.: Large synthesis of in situ field measurements of the size distribution of mineral dust aerosols across their life cycles, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 16, 4995–5007, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-4995-2024, 2024.

Formenti, P., Rajot, J. L., Desboeufs, K., Saïd, F., Grand, N., Chevaillier, S., and Schmechtig, C.: Airborne observations of mineral dust over western Africa in the summer Monsoon season: spatial and vertical variability of physico-chemical and optical properties, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 6387–6410, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-6387-2011, 2011.

Formenti, P., Caquineau, S., Chevaillier, S., Klaver, A., Desboeufs, K., Rajot, J. L., Belin, S., and Briois, V.: Dominance of goethite over hematite in iron oxides of mineral dust from Western Africa: Quantitative partitioning by X-ray absorption spectroscopy, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 119, 12,740–12,754, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD021668, 2014a.

Formenti, P., Caquineau, S., Desboeufs, K., Klaver, A., Chevaillier, S., Journet, E., and Rajot, J. L.: Mapping the physico-chemical properties of mineral dust in western Africa: mineralogical composition, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 10663–10686, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-10663-2014, 2014b.

Fouquart, Y., Bonnel, B., Brogniez, G., Buriez, J. C., Smith, L., Morcrette, J. J., and Cerf, A.: Observations of Saharan Aerosols: Results of ECLATS Field Experiment. Part II: Broadband Radiative Characteristics of the Aerosols and Vertical Radiative Flux Divergence, J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol., 26, 38–52, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1987)026<0038:OOSARO>2.0.CO;2, 1987.

Ginoux, P., Prospero, J. M., Gill, T. E., Hsu, N. C., and Zhao, M.: Global-scale attribution of anthropogenic and natural dust sources and their emission rates based on MODIS Deep Blue aerosol products, Rev. Geophys., 50, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012RG000388, 2012.

Gliß, J., Mortier, A., Schulz, M., Andrews, E., Balkanski, Y., Bauer, S. E., Benedictow, A. M. K., Bian, H., Checa-Garcia, R., Chin, M., Ginoux, P., Griesfeller, J. J., Heckel, A., Kipling, Z., Kirkevåg, A., Kokkola, H., Laj, P., Le Sager, P., Lund, M. T., Lund Myhre, C., Matsui, H., Myhre, G., Neubauer, D., van Noije, T., North, P., Olivié, D. J. L., Rémy, S., Sogacheva, L., Takemura, T., Tsigaridis, K., and Tsyro, S. G.: AeroCom phase III multi-model evaluation of the aerosol life cycle and optical properties using ground- and space-based remote sensing as well as surface in situ observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 87–128, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-87-2021, 2021.

Gómez Maqueo Anaya, S., Althausen, D., Faust, M., Baars, H., Heinold, B., Hofer, J., Tegen, I., Ansmann, A., Engelmann, R., Skupin, A., Heese, B., and Schepanski, K.: The implementation of dust mineralogy in COSMO5.05-MUSCAT, Geosci. Model Dev., 17, 1271–1295, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-1271-2024, 2024.

Gonçalves Ageitos, M., Obiso, V., Miller, R. L., Jorba, O., Klose, M., Dawson, M., Balkanski, Y., Perlwitz, J., Basart, S., Di Tomaso, E., Escribano, J., Macchia, F., Montané, G., Mahowald, N. M., Green, R. O., Thompson, D. R., and Pérez García-Pando, C.: Modeling dust mineralogical composition: sensitivity to soil mineralogy atlases and their expected climate impacts, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 8623–8657, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-8623-2023, 2023.

González-Romero, A., González-Flórez, C., Panta, A., Yus-Díez, J., Córdoba, P., Alastuey, A., Moreno, N., Kandler, K., Klose, M., Clark, R. N., Ehlmann, B. L., Greenberger, R. N., Keebler, A. M., Brodrick, P., Green, R. O., Querol, X., and Pérez García-Pando, C.: Probing Iceland's dust-emitting sediments: particle size distribution, mineralogy, cohesion, Fe mode of occurrence, and reflectance spectra signatures, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 6883–6910, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-6883-2024, 2024.

Goudie, A. S. and Middleton, N. J.: Saharan dust storms: Nature and consequences, Earth-Sci. Rev., 56, 179–204, 2001.

Harries, J., Carli, B., Rizzi, R., Serio, C., Mlynczak, M., Palchetti, L., Maestri, T., Brindley, H., and Masiello, G.: The Far-infrared Earth, Rev. Geophys., 46, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007RG000233, 2008.

Hudson, P. K., Gibson, E. R., Young, M. A., Kleiber, P. D., and Grassian, V. H.: Coupled infrared extinction and size distribution measurements for several clay components of mineral dust aerosol, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008791, 2008a.

Hudson, P. K., Young, M. A., Kleiber, P. D., and Grassian, V. H.: Coupled infrared extinction spectra and size distribution measurements for several non-clay components of mineral dust aerosol (quartz, calcite, and dolomite), Atmos. Environ., 42, 5991–5999, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.03.046, 2008b.

Israelevich, P. L., Levin, Z., Joseph, J. H., and Ganor, E.: Desert aerosol transport in the Mediterranean region as inferred from the TOMS aerosol index, J. Geophys. Res., 107, 4572, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD002011, 2002.

Jeong, G. Y.: Bulk and single-particle mineralogy of Asian dust and a comparison with its source soils, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008606, 2008.

Knippertz, P. and Stuut, J. B. W.: Mineral dust: A key player in the earth system, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8978-3, 2014.

Kok, J. F., Ridley, D. A., Zhou, Q., Miller, R. L., Zhao, C., Heald, C. L., Ward, D. S., Albani, S., and Haustein, K.: Smaller desert dust cooling effect estimated from analysis of dust size and abundance, Nat. Geosci., 10, 274–278, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2912, 2017.

Kok, J. F., Adebiyi, A. A., Albani, S., Balkanski, Y., Checa-Garcia, R., Chin, M., Colarco, P. R., Hamilton, D. S., Huang, Y., Ito, A., Klose, M., Li, L., Mahowald, N. M., Miller, R. L., Obiso, V., Pérez García-Pando, C., Rocha-Lima, A., and Wan, J. S.: Contribution of the world's main dust source regions to the global cycle of desert dust, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 8169–8193, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-8169-2021, 2021.

Kok, J. F., Storelvmo, T., Karydis, V. A., Adebiyi, A. A., Mahowald, N. M., Evan, A. T., He, C., and Leung, D. M.: Mineral dust aerosol impacts on global climate and climate change, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 4, 71–86, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00379-5, 2023.

Leon, J.-F. and Legrand, M.: Mineral dust sources in the surroundings of the north Indian Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL016690, 2003.

Li, F., Vogelmann, A. M., and Ramanathan, V.: Saharan Dust Aerosol Radiative Forcing Measured from Space, J. Clim., 17, 2558–2571, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<2558:SDARFM>2.0.CO;2, 2004.

Li, L., Mahowald, N. M., Gonçalves Ageitos, M., Obiso, V., Miller, R. L., Pérez García-Pando, C., Di Biagio, C., Formenti, P., Brodrick, P. G., Clark, R. N., Green, R. O., Kokaly, R., Swayze, G., and Thompson, D. R.: Improved constraints on hematite refractive index for estimating climatic effects of dust aerosols, Commun. Earth Environ., 5, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01441-4, 2024.

Luo, B., Minnett, P. J., Gentemann, C., and Szczodrak, G.: Improving satellite retrieved night-time infrared sea surface temperatures in aerosol contaminated regions, Remote Sens. Environ., 223, 8–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.01.009, 2019.

Maddy, E. S., DeSouza-Machado, S. G., Nalli, N. R., Barnet, C. D., Strow, L. L., Wolf, W. W., Xie, H., Gambacorta, A., King, T. S., Joseph, E., Morris, V., Hannon, S. E., and Schou, P.: On the effect of dust aerosols on AIRS and IASI operational level 2 products, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL052070, 2012.

Meinander, O., Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., Amosov, P., Aseyeva, E., Atkins, C., Baklanov, A., Baldo, C., Barr, S. L., Barzycka, B., Benning, L. G., Cvetkovic, B., Enchilik, P., Frolov, D., Gassó, S., Kandler, K., Kasimov, N., Kavan, J., King, J., Koroleva, T., Krupskaya, V., Kulmala, M., Kusiak, M., Lappalainen, H. K., Laska, M., Lasne, J., Lewandowski, M., Luks, B., McQuaid, J. B., Moroni, B., Murray, B., Möhler, O., Nawrot, A., Nickovic, S., O'Neill, N. T., Pejanovic, G., Popovicheva, O., Ranjbar, K., Romanias, M., Samonova, O., Sanchez-Marroquin, A., Schepanski, K., Semenkov, I., Sharapova, A., Shevnina, E., Shi, Z., Sofiev, M., Thevenet, F., Thorsteinsson, T., Timofeev, M., Umo, N. S., Uppstu, A., Urupina, D., Varga, G., Werner, T., Arnalds, O., and Vukovic Vimic, A.: Newly identified climatically and environmentally significant high-latitude dust sources, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 11889–11930, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-11889-2022, 2022.

Meinander, O., Uppstu, A., Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., Groot Zwaaftink, C., Juncher Jørgensen, C., Baklanov, A., Kristensson, A., Massling, A., and Sofiev, M.: Dust in the arctic: a brief review of feedbacks and interactions between climate change, aeolian dust and ecosystems, Front. Environ. Sci., 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2025.1536395, 2025.

Obiso, V., Gonçalves Ageitos, M., Pérez García-Pando, C., Perlwitz, J. P., Schuster, G. L., Bauer, S. E., Di Biagio, C., Formenti, P., Tsigaridis, K., and Miller, R. L.: Observationally constrained regional variations of shortwave absorption by iron oxides emphasize the cooling effect of dust, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 5337–5367, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-5337-2024, 2024.

Palchetti, L., Brindley, H., Bantges, R., Buehler, S. A., Camy-Peyret, C., Carli, B., Cortesi, U., Del Bianco, S., Di Natale, G., Dinelli, B. M., Feldman, D., Huang, X. L., Labonnote, L. C., Libois, Q., Maestri, T., Mlynczak, M. G., Murray, J. E., Oetjen, H., Ridolfi, M., Riese, M., Russell, J., Saunders, R., and Serio, C.: FORUM: Unique Far-Infrared Satellite Observations to Better Understand How Earth Radiates Energy to Space, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 101, E2030–E2046, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0322.1, 2020.

Prospero, J. M., Ginoux, P., Torres, O., Nicholson, S. E., and Gill, T. E.: Environmental characterization of global sources of atmospheric soil dust identified with the Nimbus 7 Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) absorbing aerosol product, Rev. Geophys., 40, 1002, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000RG000095, 2002.

Rajot, J. L., Formenti, P., Alfaro, S., Desboeufs, K., Chevaillier, S., Chatenet, B., Gaudichet, A., Journet, E., Marticorena, B., Triquet, S., Maman, A., Mouget, N., and Zakou, A.: AMMA dust experiment: An overview of measurements performed during the dry season special observation period (SOP0) at the Banizoumbou (Niger) supersite, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD009906, 2008.

Reid, E. A., Reid, J. S., Meier, M. M., Dunlap, M. R., Cliff, S. S., Broumas, A., Perry, K., and Maring, H.: Characterization of African dust transported to Puerto Rico by individual particle and size segregated bulk analysis, J. Geophys. Res., 108, 8591, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002jd002935, 2003.

Ryder, C. L., Highwood, E. J., Rosenberg, P. D., Trembath, J., Brooke, J. K., Bart, M., Dean, A., Crosier, J., Dorsey, J., Brindley, H., Banks, J., Marsham, J. H., McQuaid, J. B., Sodemann, H., and Washington, R.: Optical properties of Saharan dust aerosol and contribution from the coarse mode as measured during the Fennec 2011 aircraft campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 303–325, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-303-2013, 2013.

Sadrian, M. R., Calvin, W. M., Engelbrecht, J. P., and Moosmüller, H.: Spectral Characterization of Parent Soils from Globally Important Dust Aerosol Entrainment Regions, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, e2022JD037666, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JD037666, 2023.

Salisbury, J. W., Walter, L. S., and Vergo, N.: Mid-infrared (2.1–25 µm) spectra of minerals; first edition, Open-File Report, U. S. Geological Survey, https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr87263, 1987.

Salisbury, J. W., Walter, L. S., Vergo, N., and D'Aria, D. M.: Infrared (2.1–25 µm) spectra of minerals, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, xxvi, 267 pp., 1991.

Scanza, R. A., Mahowald, N., Ghan, S., Zender, C. S., Kok, J. F., Liu, X., Zhang, Y., and Albani, S.: Modeling dust as component minerals in the Community Atmosphere Model: development of framework and impact on radiative forcing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 537–561, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-537-2015, 2015.

Sellitto, P., Eremenko, M., Formenti, P., Alalam, P., Höpfner, M., and Di Biagio, C.: The sensitivity of the Far-infrared Outgoing Radiation Understanding and Monitoring (FORUM) mission to dust aerosols: a pseudo-observations analysis, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-5858, 2025.

Slingo, A., Ackerman, T. P., Allan, R. P., Kassianov, E. I., McFarlane, S. A., Robinson, G. J., Barnard, J. C., Miller, M. A., Harries, J. E., Russell, J. E., and Dewitte, S.: Observations of the impact of a major Saharan dust storm on the atmospheric radiation balance, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027869, 2006.

Sokolik, I. N. and Toon, O. B.: Incorporation of mineralogical composition into models of the radiative properties of mineral aerosol from UV to IR wavelengths, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 104, 9423–9444, https://doi.org/10.1029/1998JD200048, 1999.

Song, Q., Zhang, Z., Yu, H., Kok, J. F., Di Biagio, C., Albani, S., Zheng, J., and Ding, J.: Size-resolved dust direct radiative effect efficiency derived from satellite observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 13115–13135, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-13115-2022, 2022.

Thaarup, S., Djurhuus Poulsen, M., Thorsøe, K., and Keiding, J.: Study on Arctic Mining in Greenland, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.36378.21448, 2020.

Vandenbussche, S., Callewaert, S., Schepanski, K., and De Mazière, M.: North African mineral dust sources: new insights from a combined analysis based on 3D dust aerosol distributions, surface winds and ancillary soil parameters, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 15127–15146, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-15127-2020, 2020.

Vickery, K. J., Eckardt, F. D., and Bryant, R. G.: A sub-basin scale dust plume source frequency inventory for southern Africa, 2005–2008, Geophys. Res. Lett., 40, 5274–5279, https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50968, 2013.

Volz, F. E.: Infrared Refractive Index of Atmospheric Aerosol Substances, Appl Opt, 11, 755–759, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.11.000755, 1972.

Volz, F. E.: Infrared Optical Constants of Ammonium Sulfate, Sahara Dust, Volcanic Pumice, and Flyash, Appl Opt, 12, 564–568, https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.12.000564, 1973.

Wang, H., Liu, X., Wu, C., Lin, G., Dai, T., Goto, D., Bao, Q., Takemura, T., and Shi, G.: Larger Dust Cooling Effect Estimated From Regionally Dependent Refractive Indices, Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, e2023GL107647, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL107647, 2024.

Washington, R., Todd, M. C., Middleton, N., and Goudie, A. S.: Dust-storm source areas determined by the Total Ozone Monitoring Spectrometer and surface observations, Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr., 93, 297–313, 2003.

Yang, E.-S., Gupta, P., and Christopher, S. A.: Net radiative effect of dust aerosols from satellite measurements over Sahara, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL039801, 2009.

Zheng, J., Zhang, Z., Garnier, A., Yu, H., Song, Q., Wang, C., Dubuisson, P., and Di Biagio, C.: The thermal infrared optical depth of mineral dust retrieved from integrated CALIOP and IIR observations, Remote Sens. Environ., 270, 112841, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112841, 2022.

Zheng, J., Zhang, Z., Yu, H., Garnier, A., Song, Q., Wang, C., Di Biagio, C., Kok, J. F., Derimian, Y., and Ryder, C.: Thermal infrared dust optical depth and coarse-mode effective diameter over oceans retrieved from collocated MODIS and CALIOP observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 8271–8304, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-8271-2023, 2023.

Zheng, J., Zhang, Z., DeSouza-Machado, S., Ryder, C. L., Garnier, A., Di Biagio, C., Yang, P., Welton, E. J., Yu, H., Barreto, A., and Gonzalez, M. Y.: Assessment of Dust Size Retrievals Based on AERONET: A Case Study of Radiative Closure From Visible-Near-Infrared to Thermal Infrared, Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, e2023GL106808, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL106808, 2024.