the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Ethylamine-driven amination of organic particles: mechanistic insights via key intermediates identification

Peiqi Liu

Jigang Gao

Yulong Hu

Wenhao Yuan

Zhongyue Zhou

Fei Qi

Meirong Zeng

Atmospheric amines critically contribute to secondary aerosols formation via heterogeneous reactions, yet the molecular mechanisms governing heterogeneous amination chemistry of aerosols remain unclear. Here, we utilize an integrated tandem flow-tube system coupled with online ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry to elucidate the amination chemistry of ethylamine (EA) with representative organic aerosol components, including C20–C54 secondary ozonides (SOZs), C17–C27 carboxylic acids, and aldehydes. Our experiments provide evidence for the formation of four key intermediates: hydroxyl peroxyamines, amino hydroperoxides, peroxyamines, and amino ethers, which mediate SOZs conversion to hydroxyimines, amides, and imines. Furthermore, dihydroxylamines and hydroxylamines are identified as characteristic intermediates in carboxylic acids and aldehydes amination. Quantitative heterogeneous reactivity measurements (Δγeff) reveal that SOZs exhibit a pronounced inverse dependence on carbon chain length, e.g., C21 SOZ (Δγeff = 1.0 × 10−4) > C49 SOZ (Δγeff = 5.7 × 10−6), with consistently lower reactivity than acids and aldehydes, e.g., C17 acid (Δγeff = 2.3 × 10−4). The amination mechanism of SOZs is initiated by EA addition, followed by either hydroxyl peroxyamines-mediated dehydration yielding hydroxyimines and amides, or amino hydroperoxides-driven H2O2 elimination forming imines. For carboxylic acids and aldehydes, EA addition leads to dihydroxylamines and hydroxylamines formation, which subsequently dehydrate to produce amides and imines. These findings provide a mechanistic framework for understanding amine-driven aerosol aging processes that affects atmospheric chemistry, air quality, and climate systems.

- Article

(3399 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2753 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Atmospheric aerosols undergo complex chemical transformations that significantly affect human health, environmental quality, and climate systems (Shen et al., 2023; George and Abbatt, 2010). The heterogeneous evolution of organic aerosols, initiated by gaseous amines, drives the formation and growth of nitrogen-containing secondary organic aerosols (SOAs), which are critical components of atmospheric pollution (Na et al., 2007; De Haan et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2024). These transformations are governed by composition-dependent amination mechanisms, with distinct pathways for different organic aerosols, such as carboxylic acids (RCOOHs), aldehydes (RCHOs), and secondary ozonides (SOZs). Quantitative analysis of multiple amination reactions of these particles provides fundamental insights into the chemical evolution process of atmospheric SOAs.

The decomposition of SOZs upon amine exposure is initiated by a nucleophilic attack on the carbon atom of SOZs (Jørgensen and Gross, 2009). However, subsequent reaction pathways remain controversial. Na et al. (2006) demonstrated that the nucleophilic attack of NH3 on a 3,5-diphenyl-1,2,4-trioxolane (denoted as C14 SOZ), derived from the gas-phase ozonolysis of styrene, induces ring-opening reaction to form a C14 amino hydroperoxide. This crucial intermediate subsequently decompose to yield H2O2, benzaldehyde, and phenylmethanimine (C7H7N). Consistently, Almatarneh et al. (2020) and Jørgensen and Gross (2009) identified C2 amino hydroperoxide intermediates from the reactions of NH3 with a C2 SOZ, derived from the ozonolysis of ethene. In contrast, Zahardis et al. (2008) observed that the attack of octadecylamine (ODA, C18H39N) on a C18 SOZ, produced from the ozonolysis of oleic acid, generates a C36 hydroxyl peroxyamine intermediate, ultimately forming H2O, nonanal, and C27 amide. More recently, Qiu et al. (2024) reported that the attack of ethylamine on a C15 SOZ, derived from the ozonolysis of β-caryophyllene, directly open the ring and generates H2O and a C17 amine.

To our knowledge, these key intermediates (amino hydroperoxide and hydroxyl peroxyamine) have not been experimentally measured in prior studies (Na et al., 2006; Jørgensen and Gross, 2009; Almatarneh et al., 2020; Zahardis et al., 2008), creating uncertainty about their mechanistic roles in controlling the evolution of SOZ upon amine exposure. The measured stable amination products (amides, imines, and amines) additionally exhibit inconsistency across studies (Na et al., 2006; Jørgensen and Gross, 2009; Almatarneh et al., 2020; Zahardis et al., 2008). Furthermore, previous experimental investigations primarily focused on qualitative products identification, lacking both quantitative reaction rates of SOZ and amine, as well as kinetics analyses of product formation. These factors limit the evaluation of the amination chemistry in the atmosphere. To mimic the heterogeneous reactions of SOZs and amine, we generated SOZ particles via the heterogeneous ozonolysis of alkene, their dominant natural formation pathway (Qiu et al., 2024, 2022). Specifically, the ozonolysis of squalene (Sqe) was chosen as model system to generate SOZ particles, building on the demonstration of high SOZ yields (maximum ∼ 21 % total yield) from Sqe ozonolysis (Heine et al., 2017). Meanwhile, this Sqe ozonolysis system produces some carbonyl byproducts (e.g., aldehydes and carboxylic acids) enabling simultaneous quantification of carbonyl aerosols upon amine exposure.

It is widely established that reactions between carboxylic acids and amines typically proceed via acid-base neutralization to form ammonium salts (Na et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2018). However, Ditto et al. (2022) demonstrated experimentally that the heterogeneous reaction of oleic acid (C18H34O2) and NH3 yields an oleamide (C18H35ON) and H2O. This observation aligns with the calculated pathways by Charville et al. (2011), who suggested that the reaction between carboxylic acid and amine generates a dihydroxyamine intermediate that subsequently dehydrates to form an amide. Moreover, significant uncertainties persist regarding the heterogeneous reaction rates of such carboxylic acid and amine reactions (Fairhurst et al., 2017a, b; Liu et al., 2012). Fairhurst et al. (2017a) reported the heterogeneous reaction rates (uptake coefficient, γ) ranging from 10−1 (malonic acid) to 10−5 (adipic acid) upon ethylamine (C2H7N) exposure. They further revealed that the uptake of amines onto low-molecular-weight diacids (C3–C8) is structure-dependent, with higher γ values observed for odd-carbon diacids than even-carbon ones. Additionally, γ decreases with increasing carbon chain length of diacids. However, these trends remain unestablished for long-chain acids. Furthermore, to our knowledge, the heterogeneous uptake coefficients for aldehyde particles upon amine exposure have not been experimentally measured.

Our objective is to investigate the heterogeneous reactions of particulate SOZs, carboxylic acids, and aldehydes upon exposure to gaseous ethylamine (selected as model amine), using a tandem flowtube reactor. As a representative atmospheric amine (Lee and Wexler, 2013), ethylamine was selected for its remarkable heterogeneous reactivity and simple structure. The atmospheric pressure photoionization high-resolution mass spectrometer (APPI-HRMS) is used to identify reaction products and measure reaction kinetics as a function of ethylamine exposure. Additionally, the heterogeneous uptake coefficients for SOZs, aldehydes, and acids are quantified. To interpret the experimental data, the multiphase reaction mechanisms governing the decomposition of SOZs, carboxylic acids, and aldehydes, as well as the formation of featured amination products are revealed.

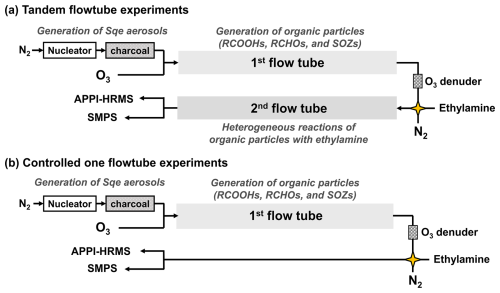

An integrated experimental system employing a tandem flowtube reactor coupled with APPI-HRMS was developed to examine the heterogeneous reactions between target organic aerosols upon ethylamine exposure, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The apparatus contains three key components: (i) in-situ generation of organic particles in the first flowtube reactor from the ozonolysis of Sqe aerosols, (ii) controlled multiphase reactions between organic particles and ethylamine in the secondary flowtube reactor, and (iii) online monitoring of chemical compositions of organic particles as a function of ethylamine exposure. To isolate the contribution of heterogeneous reactions in the secondary flowtube reactor (Fig. 1a), the controlled experiments were conducted using a single flowtube configuration, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

Figure 1Schematic diagrams of (a) the tandem flowtube system, and (b) the controlled one flowtube experiment.

2.1 Generation of organic particles in the first flowtube reactor

Polydisperse Sqe aerosols were generated via homogeneous nucleation by passing N2 (300 mL min−1) through a Pyrex tube filled with liquid Sqe (Sigma-Aldrich, 99 % purity), located in a tube furnace setting at 145 °C (Fig. 1). Upon exiting the Pyrex tube, the Sqe vapor cooled and homogeneously nucleated to form aerosols, which were subsequently passed through an annular activated charcoal denuder to remove any residual gas-phase organics produced in the oven. The average Sqe particle distribution was log-normal with a mass concentration of 6120 µg m−3 and an average diameter of 209 nm (Fig. S1 in the Supplement).

The Sqe aerosol flow was then introduced into the first quartz flowtube reactor (130 cm long and 2.6 cm inner diameter) where they reacted with O3 to generate organic particles, mainly composed of SOZs, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids (Heine et al., 2017). O3 was generated by passing 20 mL min−1 O2 through a corona discharge generator (com-ad-02, Anseros, China), with its concentration monitored using an O3 analyzer (GM-6000-OEM, Anseros, China). Dilute dry N2 (580 mL min−1) was also introduced into the first flowtube reactor to achieve a total flow rate of 900 mL min−1, corresponding to an average residence time of 46 s. The O3 concentration in the first flowtube reactor was varied from 0 to 0.678 ppm.

The chemical compositions of organic aerosols generated in the first flowtube reactor were analyzed using APPI-HRMS (Liu et al., 2024). As illustrated in Figs. S2a and S3a, the major components were identified as SOZs, carboxylic acids, and aldehydes, consistent with the product distributions measured using vacuum ultraviolet aerosol mass spectrometer (VUV-AMS) (Heine et al., 2017; Arata et al., 2019). Figure S4 displays the mass signals of representative compounds, including C27 aldehyde (C27H44O), C22 acid (C22H36O2), and C35 SOZ (C35H58O3), as a function of O3 concentration in the first flowtube reactor. It is demonstrated that, at fixed O3 concentration (e.g., 0.57 ppm), the mass signals of these compounds are stable over 30 min-operation periods with little signal fluctuation. The size distribution of organic particles was monitored using a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS, TSI 3080L DMA and 3776 CPC), revealing an average diameter of 201 nm (Fig. S1).

2.2 Reactions of organic particles with ethylamine in the secondary flowtube reactor

Upon exiting the first flowtube reactor and subsequent O3 denuder, the organic particles were introduced into a secondary quartz flowtube reactor (130 cm long and 2.6 cm inner diameter) to investigate their heterogeneous reactions with ethylamine (Fig. 1a). This coupled reactor configuration, combining organic aerosols generated in the first flowtube reactor with amine exposure in the secondary flowtube, is designated as the tandem 2FT experimental system. Ethylamine was supplied from a standard gas cylinder (1000 ppm ethylamine balanced with nitrogen; Wetry, Shanghai, China). A mixture of organic particle flow, ethylamine, and diluent N2 was introduced into the secondary flowtube reactor, maintaining a total flow rate of 1100 mL min−1 (corresponding to an average residence time of 37 s). The ethylamine concentration in the secondary flowtube reactor was varied from 0 to 43.45 ppm. All experiments were conducted at atmospheric pressure and room temperature. The experiments have been conducted under dry condition, corresponding to a relative humidity of approximately 3 % (Heine et al., 2017).

2.3 Controlled experiments in one flowtube reactor

As widely demonstrated (Bos et al., 2006; Fredenhagen and Kuhnol, 2014), the reaction kinetics measured using the APPI technique could be influenced by potential photochemical side reactions (Fig. S5). To eliminate contributions from interactions between ethylamine and organic aerosols in the APPI region, control experiments were designed (Fig. 1b). In these control experiments, organic aerosols generated in the first flowtube reactor were introduced directly into the APPI region, bypassing the secondary flowtube reactor. By subtracting the reaction kinetics of the 1FT controlled experiments from those obtained in the tandem 2FT experiments, the net contribution of heterogeneous reactions occurring in the secondary flowtube reactor was quantitatively determined (Fig. S6).

2.4 Real-time detection system and data analysis for heterogeneous reactions

A portion of the particle stream was sampled by the SMPS to measure particle size distribution and concentration. The remaining flow (800 mL min−1) was directed into the ionization region of the APPI-HRMS (Orbitrap Fusion, Thermo Scientific) for real-time chemical characterization (Fig. S5). Additional details on the application of APPI-HRMS for quantifying heterogeneous reactions of particles are available in our previous work (Liu et al., 2024).

By monitoring the mass signals of organic particles (denoted as [Particle]) as a function of ethylamine exposure, defined as the concentration of ethylamine ([ethylamine]) × residence time (t), the heterogeneous decay rate (kparticle) was determined through fitting the decay profiles to an exponential function (Eq. 1) (Smith et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2024). The effective uptake coefficient (γeff), representing the probability of reactive particle decay upon ethylamine collisions, was then calculated using Eq. (2) (Liu et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2009). In Eq. (2), D, ρ0, NA, , and M correspond to particle diameter, density, Avogadro's number, mean speed of ethylamine, and molar mass of reactant molecules, respectively. In this work, the heterogeneous reaction rates measured in the 2FT flowtube reactor experiments and single flowtube reactor (1FT) experiments were designated as γeff, 2FT and γeff, 1FT, respectively. The net contribution of heterogeneous reactions in the secondary flowtube reactor was quantified by subtracting γeff, 1FT from γeff, 2FT, yielding the differential uptake coefficient (Δγeff) as defined in Eq. (3). Figure S6 presents the decay kinetics and corresponding Δγeff values for representative compounds: C27 aldehyde, C27 acid, and C20 SOZ. For instance, γeff, 2FT and γeff, 1FT values for C20 SOZ were determined to be 8.0 × 10−5 and 6.2 × 10−5, respectively, resulting in Δγeff = 1.8 × 10−5.

3.1 Heterogeneous reactions rates of organic aerosols upon ethylamine exposure

The O3 addition reactions to the C=C bonds of Sqe in the first flowtube reactor generate primary ozonides (POZs) (Heine et al., 2017), as illustrated in Fig. S8. These POZs subsequently decompose to form three ketones (C3H6O, C8H14O, and C13H22O) with molecular weights (MWs) of 58, 126, and 194, three aldehydes (C17H28O, C22H36O, and C27H44O) with MWs of 248, 316, and 384, and six Criegee intermediates (CIs) (Heine et al., 2017). Unimolecular isomerization reactions of C17, C22, and C27 CIs produce carboxylic acids (C17H28O2, C22H36O2, and C27H44O2) with MWs of 264, 332, and 400 (Arata et al., 2019; Zahardis et al., 2005). Bimolecular reactions between CIs and aldehydes (or ketones) generate a series of SOZs (Fig. S9), including C6, C11, C16, C20, C21, C25, C26, C30, C34, C35, C39, C40, C44, C49, and C54 SOZs (Heine et al., 2017). Considering the relative higher partitioning of smaller species (e.g., ketones and smaller SOZs) into the gas phase, the present work mostly focused on larger SOZs, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids.

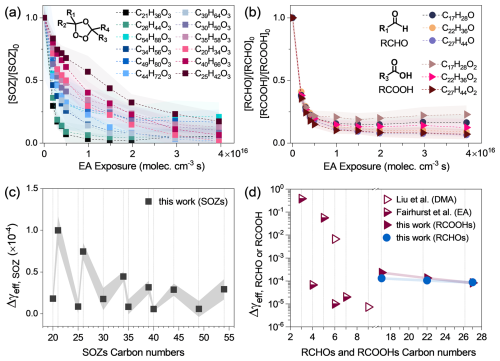

Figure 2(a–b) Decay of SOZs, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids as a function of ethylamine (EA) exposure in tandem flowtube experiments. (c–d) Differential effective uptake coefficients (Δγeff) for C20, C21, C25, C26, C30, C34, C35, C39, C40, C44, C49, and C54 SOZs; C17, C22, and C27 carboxylic acids, and C17, C22, and C27 aldehydes. Uptake coefficients for carboxylic acids from Refs (Liu et al., 2012; Fairhurst et al., 2017a) are included.

Figure 2a illustrates the relative abundance of C20 to C54 SOZs as a function of ethylamine exposure. These SOZs exhibit distinct heterogeneous decay rates (kparticle), with the C21 SOZ exhibiting the highest rate. The differential effective uptake coefficients (Δγeff), quantifying the contribution of SOZ reactions with ethylamine in the secondary flowtube reactor, were then calculated using Eqs. (2) and (3) (Fig. 2c and Table S2). The Δγeff values of SOZs generally show consistent tendencies with the decay kinetics and exhibit a zigzag pattern that decreases with increasing carbon chain length of SOZs.

Differences in the initial concentrations of SOZs may contribute to their distinct heterogeneous reactivities (Δγeff) shown in Fig. 2c. As demonstrated by Heine et al. (2017), in multi-component particles, the heterogenous reactivity of each component depends on its initial concentration (Jacobs et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2020; Arata et al., 2019). Heine et al. (2017) reported that the abundance of SOZs formed during the ozonolysis of squalene varies, following the order: C30 > C25, C35 > C44 > C20, C21, C39, C40, C49 > C26, C34, C54 SOZs, as illustrated in Fig. S7a. Consequently, in this work, the initial concentrations of SOZs formed from the ozonolysis of Sqe in the flowtube reactor differ. To quantify the influence of the initial SOZ concentrations on their heterogeneous reaction rates, the Δγeff values for SOZs were normalized for their corresponding initial concentrations. As illustrated in Fig. S7b, the normalized Δγeff values exhibit smaller differences compared to the original Δγeff values. This observation supports the hypothesis that differences in initial SOZ concentrations affect their decay rate upon ethylamine exposure. Additionally, SOZs with long-chain substituents (e.g., C54 SOZ) exhibit lower reactivity (Ponec et al., 1997). This reduced reactivity may be attributed to the steric hindrance effects (Hon et al., 1995), which restrict the conformational flexibility of SOZ molecules during attack by ethylamine.

Figure 2b illustrates the decay kinetics of representative aldehydes and carboxylic acids. These aldehydes and carboxylic acids decay faster than SOZs. Consistently, their differential effective uptake coefficients (Δγeff from 10−5 to 10−4) are larger than those of SOZs (10−5 to 10−6), as illustrated in Fig. 2d. This difference could be explained by the higher acidity of carboxylic acids, which enhances the heterogeneous reactions between these acids upon ethylamine exposure. As reported by Liu et al. (2012) the heterogeneous uptake coefficients of dimethylamine (C2H7N, an isomer of ethylamine), with citric acid (a triacid, C6H8O7, γ ∼ 10−3) is significantly larger than with humic acid (a diacid, C9H9NO6, γ ∼ 10−6). They attributed this difference to the stronger acidity of citric acid relative to humic acid.

Figure 2d illustrates that the measured Δγeff values for carboxylic acids follow the trend: C17H28O2 > C22H36O2 > C27H44O2, indicating a negative dependence of heterogeneous reactivity on carbon chain length. A similar trend is observed for aldehydes, i.e., C17H28O > C22H36O > C27H44O. To our knowledge, no prior experimental measurements exist for the heterogeneous reactivity of aldehyde particles with ethylamine, whereas reactivity trends for carboxylic acids of varying carbon chain length have been investigated (Fairhurst et al., 2017a). For example, Fairhurst et al. (2017a) measured the heterogeneous reactivities of ethylamine by solid dicarboxylic acids with varying carbon numbers: malonic acid (C3H4O4), succinic acid (C4H6O4), glutaric acid (C5H8O4), adipic acid (C6H10O4), and pimelic acid (C7H12O4). Their measured uptake coefficients are approximately 10−1 for C3 diacids, 7 × 10−5 for C4 diacid, and 1 × 10−5 for the C6 diacid. They attributed this trend to differences in the crystalline surface structures of these solid acids. Thus, these reported uptake coefficients for carboxylic acids reacting with amine span a wide range (10−1 to 10−6), suggesting that more comprehensive data are needed to elucidate the reactivity trends for both carboxylic acids and aldehydes across varying carbon chain length.

3.2 Products distribution during the heterogeneous reactions of organic particles

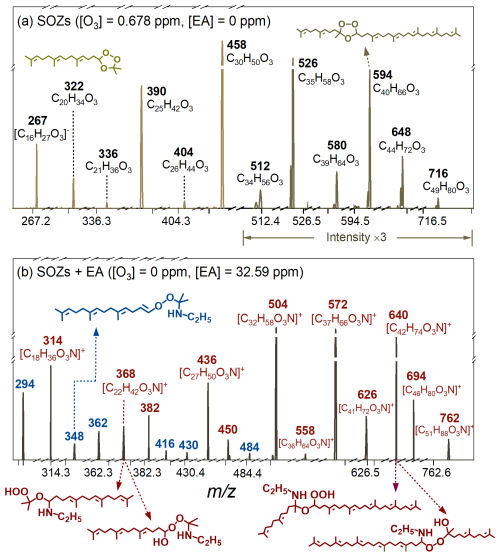

Figure 3a illustrates the product distribution during the ozonolysis of Sqe aerosols. Consistent with prior observations (Liu et al., 2024), maximum product yields were achieved at approximately 60 % Sqe conversion (corresponding to 0.678 ppm O3), with representative products (SOZs, aldehydes, and acids) shown in Figs. S2 and S3. Figures 3b and S3 show representative products from heterogeneous reactions between SOZs with ethylamine (C2H7N), with mass spectral analysis revealing three product classes. First, protonated molecular ions (denoted as [M + H]+) appear at 314, 368, 382, 436, 450, 504, 558, 572, 626, 640, 694, and 762, corresponding to adducts from reactions between SOZs and ethylamine, i.e., SOZs + C2H7N. For instance, the 504 peak corresponds to C32H57O3N (MW 503) from the reaction of C30 SOZ (C30H50O3) with C2H7N. Detailed reaction mechanisms are discussed in Sect. 3.3. Second, the deprotonated ions ([M − H]−) at 294, 348, 362, 416, 430, and 484 derive from subsequent dehydration products from SOZs + C2H7N reactions, i.e., SOZs + C2H7N − H2O. For instance, the 484 peak matches the H2O loss product of C32H57O3N, i.e., C32H57O3N − H2O. Third, the deprotonated ions ([M − H]−) at 278, 332, 346, 400, 414, 468, and 536 correspond to the H2O2 elimination products from SOZs and C2H7N reactions, i.e., SOZs + C2H7N − H2O2. For instance, the 468 peak represents the H2O2 elimination product of C32H57O3N, i.e., C32H57O3N − H2O2. Notably, dehydration and H2O2 elimination products were only observed for smaller SOZs (Cn < 35), suggesting that substituent effects and chain length of SOZs could influence the amination reaction pathways (see Sect. 3.3 for mechanistic details).

Figure 3Mass spectra of (a) representative SOZs (the signals within range of 500–800 are amplified) formed during the ozonolysis of Sqe in the first flowtube reactor, and (b) their amination products (adducts of SOZ + EA are in red and dehydration products are in blue) upon exposure to ethylamine (EA) in the secondary flowtube reactor.

Figures S2b and S3b illustrate the products formed from heterogeneous reactions of C17, C22, and C27 aldehydes (RCHOs), as well as C17, C22, and C27 carboxylic acids (RCOOHs) upon ethylamine exposure in the secondary flowtube reactor. The protonated molecular ions ([M + H]+) at 294, 310, 362, 378, 430, and 446 correspond to products from reactions of these aldehydes (or carboxylic acids) with ethylamine (C2H7N), i.e., RCHOs (or RCOOHs) + C2H7N (Bain et al., 2016; De Haan et al., 2011). For instance, the peak at 294 is assigned to C19H35ON (MW 293) formed from the reaction of C17 aldehyde (C17H28O) with C2H7N. These RCHOs (or RCOOHs) + C2H7N adducts subsequently undergo H2O elimination reactions (Shen et al., 2023; Bain et al., 2016; De Haan et al., 2009; Tuguldurova et al., 2024), producing characteristic peaks at 276, 344, and 412 (from aldehyde reactions); as well as 292, 360, and 428 (from acid reactions). For instance, the [M + H]+ peak at 276 corresponds C19H33N (MW 275), resulting from H2O elimination from C19H35ON, i.e., C19H35ON − H2O.

3.3 Amination mechanisms of secondary ozonides, carboxylic acids, and aldehydes

A reaction mechanism was developed to elucidate the heterogeneous reactions of organic aerosols, including SOZs, carboxylic acids (C17H28O2, C22H36O2, and C27H44O2), and aldehydes (C17H28O, C22H36O, and C27H44O).

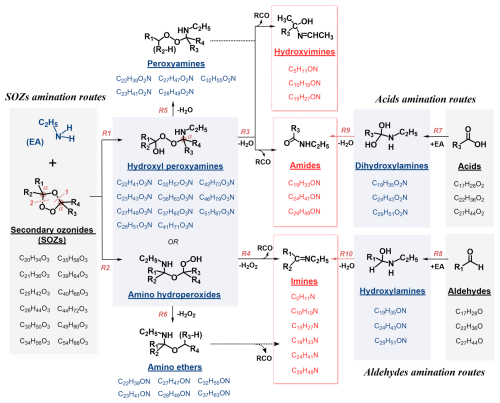

Figure 4Amination mechanisms of secondary ozonides (SOZs), carboxylic acids (RCOOHs), and aldehydes (RCHOs) upon ethylamine (EA) exposure, with representative chemical structures and compositions of reactants and products.

For SOZs, the electronegativity of neighboring oxygen atoms induces a net positive charge on the α-carbon atoms (Fig. 4), facilitating nucleophilic attack by an amine (Jørgensen and Gross, 2009). This could lead to the formation of either hydroxyl peroxyamines (R1) or amino hydroperoxides (R2), depending on the nucleophilic attack sites (Zahardis et al., 2008; Jørgensen and Gross, 2009; Almatarneh et al., 2020). However, these competing pathways and their proposed products remain controversial (Fig. S11). Zahardis et al. (2008) proposed that SOZ reaction with octadecylamine generates a hydroxyl peroxyamine intermediate, which subsequently decomposes to nonanal and a C27 amide via H2O elimination (Fig. S11a). Conversely, Almatarneh et al. (2020), Jørgensen and Gross (2009), and Na et al. (2006) suggested that SOZ reactions with ammonia form amino hydroperoxide intermediates (Fig. S11b to e). Notably, neither hydroxyl peroxyamine nor amino hydroperoxide intermediates have been experimentally detected in these studies (Zahardis et al., 2008; Almatarneh et al., 2020; Jørgensen and Gross, 2009; Na et al., 2006). Contrasting both pathways, Qiu et al. (2024) demonstrated that ethylamine addition to a cyclic SOZ directly yields a linear amination product through simultaneously H2O elimination (Fig. S11a), i.e., bypassing formation of either proposed intermediates (Fig. S11f).

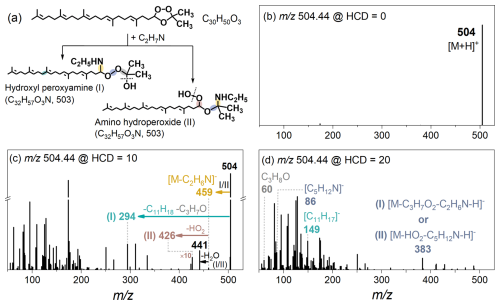

Figure 5(a) Structures of two representative isomers (C32H57O3N, MW 503), i.e., hydroxyl peroxyamine (I) and amino hydroperoxide (II). (b–d) MS2 fragmentation of their protonated ions at HCD energies: (b) 0 %, (c) 10 %, and (d) 20 %.

In this work, mass peaks corresponding to SOZs + ethylamine (C2H7N) adducts were observed (Fig. 3b), providing direct experimental evidence for nucleophilic attack by ethylamine on SOZs. The MS2 spectra provide complementary evidence for their structural characterization. Figure 5 illustrates representative MS2 fragmentation patterns of the [C32H58O3N]+ ion (denoted as [M + H]+), corresponding to the C32H57O3N product formed from C30 SOZ (C30H50O3) + ethylamine (C2H7N) reaction. Two representative isomers, a hydroxyl peroxyamine (I) and amino hydroperoxide (II), were selected for analysis (Fig. 5a). Both isomers undergo C2H5NH elimination, yielding [M − C2H6N]− ions ( 459). The hydroxyl peroxyamine isomer (I) subsequently loses C3H7O and C11H18 to form 294, while the amino hydroperoxide isomer (II) eliminates HO2 yielding 426. Additional fragmentation peaks ( 60, 86, 149, 383, and 441) may derive from these isomers. It is also noted that C30 SOZ isomers formation during the ozonolysis of Sqe (Figs. S9 and S10b) suggests additional C32H57O3N isomers likely contribute to these fragmentation patterns (Fig. 5). Figure 6a illustrates the kinetics of representative C30 hydroxyl peroxyamines (or amino hydroperoxides) as a function of ethylamine exposure.

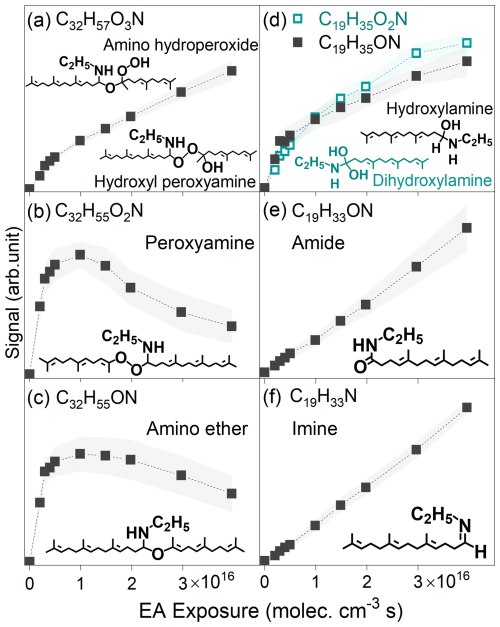

Figure 6Experimental signal as a function of ethylamine (EA) exposure for: (a) hydroxyl peroxyamine (or amino hydroperoxide), (b) peroxyamine, (c) amino ether, (d) dihydroxylamine and hydroxylamine, (e) amide, and (f) imine.

Consumption reactions for the amino hydroperoxide and hydroxyl peroxyamine intermediates were previously proposed (Zahardis et al., 2008; Na et al., 2006; Almatarneh et al., 2020; Jørgensen and Gross, 2009). Amino hydroperoxide decomposition has been demonstrated to generate smaller imines and aldehydes via H2O2 elimination (Fig. 4). For instance, Almatarneh et al. (2020) demonstrated that a C2 amino hydroperoxide decomposition yields methylenimine, formaldehyde, and H2O2 (Fig. S11). Consistently, products with compositions of C5H11N, C10H19N, C15H27N, C19H33N, C24H41N, and C29H49N are assigned to be imines (Fig. S13) that could be attributed to these reactions. In contrast, for hydroxyl peroxyamine, Zahardis et al. (2008) reported that hydroxyl peroxyamine decomposition generates a C27 amide, C9 aldehyde with H2O elimination. Observed products with compositions of C19H33ON, C24H41ON, and C29H49ON are proposed to be amides (Fig. S12) that could be formed from these pathways. Moreover, hydroxyl peroxyamines lacking α-H atoms form hydroxyimines (C5H11ON, C10H19ON, and C15H27ON), rather than amides. For instance, a C36 hydroxyl peroxyamine with available α-H atom (Fig. S12a) decomposes to a C19 amide, C17 aldehyde and H2O, whereas a C28 hydroxyl peroxyamine without α-H atom (Fig. S12b) yields C15 hydroxyimine, C13 ketone, and H2O.

These hydroxyimines, amides, and imines (Fig. 4) exhibit significantly lower carbon numbers than their precursor hydroxy peroxyamines (R3) or amino hydroperoxides (R4). Consequently, neither R3 nor R4 pathways explain observed products retaining same carbon numbers with amino hydroperoxides or hydroxy peroxyamines. This work therefore proposes two new pathways: R5 (hydroxyl peroxyamine → H2O + peroxyamine), and R6 (amino hydroperoxide → H2O2 + amino ether). With C32 intermediates for example, these pathways reasonably explain observed C32H55O2N (peroxyamine) and C32H55ON (amino ether) products formed from C32H57O3N via H2O or H2O2 elimination, respectively (Fig. 6b and c). The observed trend of their experimental signal, which initially increased and then decreased as a function of ethylamine exposure, providing evidence for mediating the conversion of hydroxy peroxyamine (or amino hydroperoxide) to hydroxylamine, amide, and imine. Given the absence of these pathways in prior work (Almatarneh et al., 2020; Na et al., 2006; Zahardis et al., 2008; Qiu et al., 2024; Jørgensen and Gross, 2009), these R5 and R6 require further investigations. Figure S15 summarizes a simplified mechanism involving four key intermediates, including hydroxyl peroxyamines, peroxyamines, amino hydroperoxides, and amino ethers.

Figure 4 illustrates reaction mechanisms for ethylamine reactions with C17, C22, and C27 carboxylic acids, as well as C17, C22, and C27 aldehydes, forming dihydroxylamines (R7) and hydroxylamines (R8), respectively (De Haan et al., 2011; Ditto et al., 2022; Bain et al., 2016; Shashikala et al., 2023; Sarkar et al., 2019). For instance, the nucleophilic attack reaction of ammonia at carbonyl (C=O) site of acetaldehyde generates a hydroxylamine as demonstrated by Sarkar et al. (2019). Here, dihydroxylamines (C19H35O2N, C24H43O2N, C29H51O2N) and hydroxylamines (C19H35ON, C24H43ON, and C29H51ON) have been measured by APPI-HRMS (Fig. S2b) (Sarkar et al., 2019), as well as their kinetics as a function of ethylamine exposure (e.g., C19 dihydroxylamine and hydroxylamine in Fig. 6d). Subsequent H2O elimination reactions of dihydroxylamines and hydroxylamines yield amides (R9, C19H33ON, C24H41ON, and C29H49ON) and imines (R10, e.g., C19H33N, C24H41N, and C29H49N) (Montgomery and Day, 1965), respectively, as shown in Fig. S2b. For example, C17 aldehyde (C17H28O, Fig. S14a) reacts with ethylamine to generate C19 hydroxylamine intermediate (C19H35ON, MW 293), which dehydrates to C19 imine (C19H33N, MW 275). Additionally, these amides and imines can be also produced from hydroxyl peroxyamines (R3) or amino hydroperoxides (R4), as shown in Fig. 6e and f.

Atmospheric amines critically modulate the evolution of aerosols and particulate pollution. Here, we investigate heterogeneous reactions of ethylamine with SOZs, carboxylic acids, and aldehydes aerosols using a tandem flowtube reactor combined with online APPI-HRMS. Heterogeneous reactivities (Δγeff) for SOZs decrease 17.5-fold with increasing carbon chain length, from Δγeff = 1.0 × 10−4 for C21 SOZ to 5.7 × 10−6 for C49 SOZ, with nonmonotonic behavior suggesting substitution effects. Crucially, reactions of ethylamine with carboxylic acids and aldehydes exhibit Δγeff values of 10−4 to 10−5, exceeding SOZs reactivity at equivalent carbon numbers, with reactivity similarly declining with chain length. This reactivity dependence implies atmospheric lifetimes () spanning two orders of magnitude across these organic aerosols, thereby controlling their differential impacts on air quality, health, and climate. Moreover, hydroxyl peroxyamines, amino hydroperoxides, peroxyamines, and amino ethers, were measured as characteristic intermediates linking SOZ consumption to stable nitrogenous products (hydroxyimines, amides, and imines). Dihydroxylamines and hydroxylamines from reactions of carboxylic acids and aldehydes were characterized as crucial intermediates. Further reaction mechanism analysis reveals that nucleophilic addition of ethylamine to SOZs initiates the formation of hydroxyl peroxyamines and amino hydroperoxides. Beyond established cleavage pathways yielding form hydroxyimines, amides, and imines, this work demonstrates new elimination pathways: hydroxyl peroxyamines (amino hydroperoxides) → H2O (or H2O2) + peroxyamines (or amino ethers). These mechanistic insights elucidate the transformation of organic aerosols to nitrogen-containing secondary organic aerosols (SOAs), providing fundamental parameters for more accurate modeling of atmospheric processes.

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this work are available within the article and its Supplement.

Supplementary details about the experimental data (Figs. S1 to S7) and reaction mechanism (Figs. S8 to S15, and Tables S1 to S2) are available in the Supplement. The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-18313-2025-supplement.

PL performed the investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and wrote the original draft. JG and YH contributed to data curation. MZ, WY, ZZ, and FQ developed the methodology. MZ was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors are grateful for the funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan. The authors thank Kevin R. Wilson (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) for helpful discussions.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22373066 and 52376119) and Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan (grant no. 24142201500).

This paper was edited by Quanfu He and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Almatarneh, M. H., Alrebei, S. F., Altarawneh, M., Zhao, Y., and Abu-Saleh, A. A.-A.: Computational study of the dissociation reactions of secondary ozonide, Atmosphere., 11, 100–110, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11010100, 2020.

Arata, C., Heine, N., Wang, N., Misztal, P. K., Wargocki, P., Bekö, G., Williams, J., Nazaroff, W. W., Wilson, K. R., and Goldstein, A. H.: Heterogeneous ozonolysis of squalene: gas-phase products depend on water vapor concentration, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 14441–14448, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b05957, 2019.

Bain, R. M., Pulliam, C. J., Ayrton, S. T., Bain, K., and Cooks, R. G.: Accelerated hydrazone formation in charged microdroplets, Rapid. Commun. Mass. Sp., 30, 1875–1878, https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7664, 2016.

Bos, S. J., van Leeuwen, S. M., and Karst, U.: From fundamentals to applications: recent developments in atmospheric pressure photoionization mass spectrometry, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 384, 85–99, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-005-0046-1, 2006.

Charville, H., Jackson, D. A., Hodges, G., Whiting, A., and Wilson, M. R.: The uncatalyzed direct amide formation reaction – mechanism studies and the key role of carboxylic acid H-bonding, Eur. J. Org. Chem., 2011, 5981–5990, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201100714, 2011.

De Haan, D. O., Tolbert, M. A., and Jimenez, J. L.: Atmospheric condensed-phase reactions of glyoxal with methylamine, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, 11819–11823, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl037441, 2009.

De Haan, D. O., Hawkins, L. N., Kononenko, J. A., Turley, J. J., Corrigan, A. L., Tolbert, M. A., and Jimenez, J. L.: Formation of nitrogen-containing oligomers by methylglyoxal and amines in simulated evaporating cloud droplets, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 984–991, https://doi.org/10.1021/es102933x, 2011.

Ditto, J. C., Abbatt, J. P. D., and Chan, A. W. H.: Gas- and particle-phase amide emissions from cooking: mechanisms and air quality impacts, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 7741–7750, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c01409, 2022.

Fairhurst, M. C., Ezell, M. J., and Finlayson-Pitts, B. J.: Knudsen cell studies of the uptake of gaseous ammonia and amines onto C3–C7 solid dicarboxylic acids, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 19, 26296–26309, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp05252a, 2017a.

Fairhurst, M. C., Ezell, M. J., Kidd, C., Lakey, P. S. J., Shiraiwa, M., and Finlayson-Pitts, B. J.: Kinetics, mechanisms and ionic liquids in the uptake of n-butylamine onto low molecular weight dicarboxylic acids, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 19, 4827-4839, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cp08663b, 2017b.

Fredenhagen, A. and Kuhnol, J.: Evaluation of the optimization space for atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI) in comparison with APCI, J. Mass. Spectrom., 49, 727–736, https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.3401, 2014.

Gao, X., Zhang, Y., and Liu, Y.: A kinetics study of the heterogeneous reaction of n-butylamine with succinic acid using an ATR-FTIR flow reactor, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 20, 15464–15472, https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cp01914b, 2018.

George, I. J. and Abbatt, J. P.: Heterogeneous oxidation of atmospheric aerosol particles by gas-phase radicals, Nat. Chem., 2, 713–722, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.806, 2010.

Heine, N., Houle, F. A., and Wilson, K. R.: Connecting the elementary reaction pathways of criegee intermediates to the chemical erosion of squalene interfaces during ozonolysis, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 13740–13748, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b04197, 2017.

Hon, Y. S., Lin, S. W., Lu, L., and Chen, Y. J.: The mechanistic study and synthetic applications of the base treatment in the ozonolytic reactions, Tetrahedron., 51, 5019–5034, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(95)98699-I, 1995.

Jacobs, M. I., Xu, B., Kostko, O., Heine, N., Ahmed, M., and Wilson, K. R.: Probing the heterogeneous ozonolysis of squalene nanoparticles by photoemission, J. Phys. Chem. A., 120, 8645–8656, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.6b09061, 2016.

Jørgensen, S. and Gross, A.: Theoretical investigation of reactions between ammonia and precursors from the ozonolysis of ethene, Chem. Phys., 362, 8–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2009.05.020, 2009.

Lee, D. and Wexler, A. S.: Atmospheric amines – part III: Photochemistry and toxicity, Atmos. Environ., 71, 95–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.01.058, 2013.

Liu, P., Gao, J., Xiao, X., Yuan, W., Zhou, Z., Qi, F., and Zeng, M.: Investigating the kinetics of heterogeneous lipid ozonolysis by an online photoionization high-resolution mass spectrometry technique, Anal. Chem., 96, 19576–19584, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.4c04404, 2024.

Liu, Y., Ma, Q., and He, H.: Heterogeneous uptake of amines by citric acid and humic acid, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 11112–11118, https://doi.org/10.1021/es302414v, 2012.

Montgomery, M. W. and Day, E. A.: Aldehyde-amine condensation reaction: a possible fate of carbonyls in foods, J. Food. Sci., 30, 828–832, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1965.tb01849.x, 1965.

Na, K., Song, C., and Cockeriii, D.: Formation of secondary organic aerosol from the reaction of styrene with ozone in the presence and absence of ammonia and water, Atmos. Environ., 40, 1889–1900, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.10.063, 2006.

Na, K., Song, C., Switzer, C., and Cocker, D. R.: Effect of ammonia on secondary organic aerosol formation from α-pinene ozonolysis in dry and humid conditions, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 6096–6102, https://doi.org/10.1021/es061956y, 2007.

Ponec, R., Yuzhakov, G., Haas, Y., and Samuni, U.: Theoretical analysis of the stereoselectivity in the ozonolysis of olefins. Evidence for a modified criegee mechanism, J. Org. Chem., 62, 2757–2762, https://doi.org/10.1021/jo9621377, 1997.

Qiu, J., Fujita, M., Tonokura, K., and Enami, S.: Stability of terpenoid-derived secondary ozonides in aqueous organic media, J. Phys. Chem. A., 126, 5386–5397, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c04077, 2022.

Qiu, J., Shen, X., Chen, J., Li, G., and An, T.: A possible unaccounted source of nitrogen-containing compound formation in aerosols: amines reacting with secondary ozonides, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 155–166, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-155-2024, 2024.

Sarkar, S., Oram, B. K., and Bandyopadhyay, B.: Ammonolysis as an important loss process of acetaldehyde in the troposphere: energetics and kinetics of water and formic acid catalyzed reactions, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 21, 16170–16179, https://doi.org/10.1039/c9cp01720h, 2019.

Shashikala, K., Niha, P. M., Aswathi, J., Sharanya, J., and Janardanan, D.: Theoretical exploration of new particle formation from glycol aldehyde in the atmosphere - A temperature-dependent study, Comput. Theor. Chem., 1222, 114057–114067, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2023.114057, 2023.

Shen, X., Chen, J., Li, G., and An, T.: A new advance in the pollution profile, transformation process, and contribution to aerosol formation and aging of atmospheric amines, Environ. Sci.: Atmos., 3, 444–473, https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ea00167e, 2023.

Smith, J. D., Kroll, J. H., Cappa, C. D., Che, D. L., Liu, C. L., Ahmed, M., Leone, S. R., Worsnop, D. R., and Wilson, K. R.: The heterogeneous reaction of hydroxyl radicals with sub-micron squalane particles: a model system for understanding the oxidative aging of ambient aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 3209–3222, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-3209-2009, 2009.

Smith, J. N., Barsanti, K. C., Friedli, H. R., Ehn, M., Kulmala, M., Collins, D. R., Scheckman, J. H., Williams, B. J., and McMurry, P. H.: Observations of aminium salts in atmospheric nanoparticles and possible climatic implications, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 6634–6639, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912127107, 2010.

Tian, X., Chan, V. Y., and Chan, C. K.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from aqueous ethylamine oxidation mediated by particulate nitrate photolysis, ACS ES&T Air., 1, 951–959, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestair.3c00095, 2024.

Tuguldurova, V. P., Kotov, A. V., Vodyankina, O. V., and Fateev, A. V.: Nature or number of species in a transition state: the key role of catalytically active molecules in hydrogen transfer stages in atmospheric aldehyde reactions, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 26, 5693–5703, https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp04500e, 2024.

Zahardis, J., LaFranchi, B. W., and Petrucci, G. A.: Photoelectron resonance capture ionization-aerosol mass spectrometry of the ozonolysis products of oleic acid particles: Direct measure of higher molecular weight oxygenates, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmo., 110, D08307, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004jd005336, 2005.

Zahardis, J., Geddes, S., and Petrucci, G. A.: The ozonolysis of primary aliphatic amines in fine particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 1181–1194, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-1181-2008, 2008.

Zeng, M., Heine, N., and Wilson, K. R.: Evidence that criegee intermediates drive autoxidation in unsaturated lipids, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 4486–4490, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920765117, 2020.