the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Reaction between Criegee intermediates and hydroxyacetonitrile: reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and atmospheric implications

Chaolu Xie

Shunyu Li

Hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN) is released from wildfires and bleach cleaning environments, which is harmful to the environment and human health. However, its atmospheric lifetime remains unclear. Here, we theoretically investigate the reactions of Criegee intermediates (CH2OO and syn-CH3CHOO) with HOCH2CN to explore their reaction mechanisms and obtain their quantitative kinetics. Specifically, we employ computational strategies approaching CCSDT(Q)/CBS accuracy, combined with a dual-level strategy, to unravel the key factors governing the reaction kinetics. We find an unprecedentedly low enthalpy of activation of −5.61 kcal mol−1 at 0 K for CH2OO + HOCH2CN among CH2OO reaction with atmospheric species containing a C ≡ N group. Furthermore, we also find that the low enthalpy of activation is caused by hydrogen bonding interactions. Moreover, the present findings reveal the rate constant of CH2OO + HOCH2CN determined by loose and tight transition states has a significantly negative temperature dependence, reaching 10−10 cm3 molec.−1 s−1 close to the collisional limit at below 220 K. In addition, our findings also reveal that the rate constant of CH2OO + HOCH2CN is 103–102 times faster than that of OH + HOCH2CN below 260 K. The calculated kinetics in combination with data based on global atmospheric chemical transport model suggest that the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction dominates over the sink of HOCH2CN at southeast China, northern India at 1 km and in the Indonesian and Malaysian regions at 5 and 10 km. The present findings also reveal that the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction leads to the formation of glycolamide, which could contribution to the formation of secondary oganic aerosols.

- Article

(2238 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1183 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN), a reactive nitrogen-containing compound, has recently been identified as a C2H3NO isomer. Earlier field measurements had attributed the C2H3NO signal to methyl isocyanate (CH3NCO) when using chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS) (Priestley et al., 2018; Mattila et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022a), as CIMS is insensitive to the detection of isomers, and thus cannot differentiate between the isomers of CH3NCO and HOCH2CN. However, very recent detection with I− chemical ionization mass spectrometry (I-CIMS) identified the C2H3NO signal as HOCH2CN (Finewax et al., 2024). In other words, the CH3NCO detected in the atmosphere is essentially HOCH2CN. Therefore, the atmospheric sources of CH3NCO from previous investigations are actually the sources of HOCH2CN. Consequently, HOCH2CN is emitted in chemicals released from biomass burning, such as wildfires and agricultural fires, as well as in bleach cleaning environments (Mattila et al., 2020; Priestley et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022a; Koss et al., 2018; Papanastasiou et al., 2020).

Previous studies have demonstrated that HOCH2CN is secondary pollutant with negative impacts on the environment and human health (Worthy, 1985; Etz et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025). Specifically, smoke with HOCH2CN can be injected into the stratosphere through pyrocumulonimbus clouds, altering the composition of stratospheric aerosols, depleting the ozone layer, and affecting the Earth's radiation balance (Bernath et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2024; Katich et al., 2023). Additionally, HOCH2CN is harmful to human health, including damage to the respiratory system and skin (Mehta et al., 1990; Bucher, 1987). Therefore, understanding the chemical processes of HOCH2CN is important in the atmosphere.

The atmospheric lifetimes of HOCH2CN in the gas phase are not well understood. Hydroxyl radical (OH) is the most prevalent oxidant in the atmosphere (Wang et al., 2021). The generally considered removal for this species is through the reaction with hydroxyl radical (OH). However, the rate constant of OH + HOCH2CN is very slow, about cm3 molec.−1 s−1 at 298 K (Marshall and Burkholder, 2024). This leads to that OH makes limited contribution to the sinks of HOCH2CN in the atmosphere. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the other removal routes for HOCH2CN in the atmosphere.

Criegee intermediates are crucial compounds, resulting from the ozonolysis of unsaturated compounds in the atmosphere (Criegee, 1975; Osborn and Taatjes, 2015; Chhantyal-Pun et al., 2020a; Bunnelle, 1991; Chhantyal-Pun et al., 2020b). They play key roles in the chemical processes of atmosphere because they significantly contribute to the formation of hydroxyl radical (OH) and sulfuric acid during the nighttime (Novelli et al., 2014; Lester and Klippenstein, 2018; Kroll et al., 2002; Newland et al., 2018; Kukui et al., 2021). Additionally, they can form secondary organic aerosols via the formation of low-volatile organic compound percussors (Khan et al., 2018; Inomata et al., 2014; Docherty et al., 2005; Chhantyal-Pun et al., 2018). In particular, Criegee intermediates can initiate atmospheric reactions, resulting in additional sinks for atmospheric species such as the reactions of Criegee intermediates with formic acid, nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, and formaldehyde and so on (Khan et al., 2018; Peltola et al., 2020; Long et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2019; Foreman et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2023). While reaction kinetics of Criegee intermediates with HOCH2CN are prerequisite for elucidating its chemical processes and finding new sink pathways in the atmosphere, its kinetics are unknown.

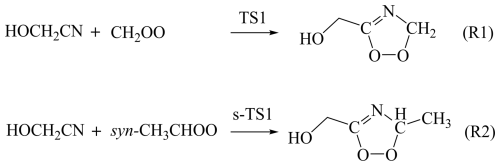

In this article, we have investigated the reactions of Criegee intermediates (CH2OO and syn-CH3CHOO) with HOCH2CN by using specific computational strategies and methods to obtain quantitative enthalpies of activation at 0 K for Reactions (R1) and (R2) (See Scheme 1). Then, we used a dual-level strategy to obtain their quantitative rate constants under atmospheric conditions. In our dual-level strategy, W3X-L//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ is used to obtain conventional transition state theory rate constants, while validated DFT methods capture recrossing and tunnelling effects through CVT with small-curvature tunnelling. Additionally, torsional anharmonicity and vibrational anharmonicity are considered in kinetics calculations. We also considered the decomposition process of the intermediate product formed in Reaction (R1). Finally, we discuss the importance of these reactions investigated here by comparing with the corresponding OH radical reactions combined with the atmospheric concentrations of these species based on global atmospheric chemistry transport model GEOS-Chem (http://www.geos-chem.org, last access: 4 November 2025).

2.1 Electronic structure methods and strategies

For simplicity, the activation enthalpy at 0 K is defined as the difference between the transition states and the reactants, abbreviated as . The difference between the products and the reactants is defined the reaction enthalpy at 0 K, abbreviated as ΔH0.

Morden quantum chemical methods and reaction rate theory can be used to obtain quantitative kinetics for atmosphere reactions (Long et al., 2018). However, the calculated processes are very complex, where error bars are controlled by multiple parameters. Furthermore, the parameters are correlated with each other. Gas-phase chemical reactions also crucially depend on entropies in thermalized conditions at non-zero temperatures, as well as excess energy, collisional stabilization, and fall-off effects in non-thermalized conditions. However, accurate determination of remains essential for calculating quantitative kinetics. The quantitative that is determined by optimized geometries, zero-point vibrational energies, and single point energies in electronic structure methods (Long et al., 2019a).

Our previous investigations have shown that W3X-L (Chan and Radom, 2015)//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ (Győrffy and Werner, 2018; Parker et al., 2014) can be utilized to obtain quantitative for the bimolecular reactions containing Criegee intermediate (Wang et al., 2022b; Long et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Here, we used W3X-L//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ to investigate the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction. Additionally, CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVDZ-F12 was used to validate the reliability of DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ for optimized geometries and calculated frequencies in the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction. Thus, with respect to syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN, the validated DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ method was used to do geometrical optimization and frequency calculations. In single point energy calculations, it is noted that W3X-L is equal to W2X and post-CCSD(T) components (Chan and Radom, 2015). Here, we assume that post-CCSD(T) contribution of syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN approximately equates to the contribution from CH2OO + HOCH2CN. We used the approximation strategy mentioned previously (Sun et al., 2023) to obtain the accuracy close to W3X-L in Eq. (1) for syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN to reduce computational costs.

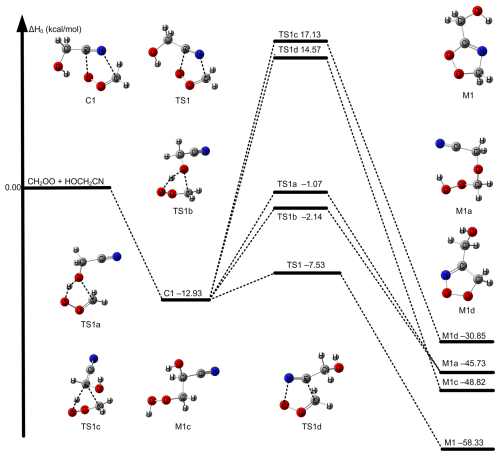

Here, is the barrier height for the transition state s-TS1 (See Scheme 1). is the barrier height for s-TS1 calculated by W2X. is post-CCSD(T) contribution that comes from the difference between W3X-L and W2X in TS1 (See Figs. 1 and 2). The benchmark methods are called higher level (HL) structure methods; this helps to clearly illustrate the dual-level strategy for kinetics calculations discussed below.

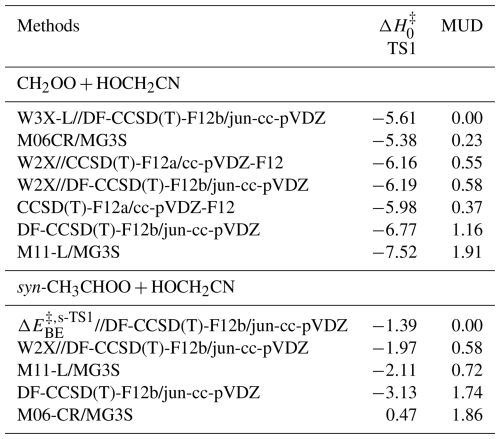

A reliable density functional method was chosen in comparison to the benchmark results to perform direct kinetics calculations. Here, we chose M06-CR (Long et al., 2021)/MG3S (Zhao et al., 2005) and M11-L (Peverati and Truhlar, 2012) /MG3S functional method for the reactions of CH2OO and syn-CH3CHOO with HOCH2CN due to the mean unsigned deviation (MUD) of 0.23 and 0.72 kcal mol−1 as listed in Table 1, respectively. M06CR/MG3S and M11-L/MG3S are called lower level (LL) electronic structure method in the present work. The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) was performed by M11-L/MG3S, and the results were depicted in Fig. S3.

2.2 Scale factors for calculated frequencies

Previous studies have verified that the standard scale (See Table S1 in the Supplement) is suitable for reactants and some transition states (Bao et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2017). In order to further explore the effect of anharmonicity on the zero-point vibrational energy, the calculation of the specific reaction scale factors was carried out. The results in Tables S2 and S4 show that the anharmonicity can be neglected in calculating . Details of the calculations can be found in previous work of Long et al. (2023). Therefore, we used standard scale factor in this work.

2.3 Kinetics methods

The rate constants of the Reaction (R1) were calculated by considering the tight and loose transition states because of its low-temperature close-to-collision-limit rate constant. Here, the loose transition state refers to the process from the reactants to the pre-reaction complexes, while the tight transition state is the process from the reactants to the products via the transition state TS1 in Fig. 1. The steady state approximation based on the canonical unified statistical theory (CUS) (Garrett and Truhlar, 1982; Bao and Truhlar, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020) is used to calculate the total rate constant by simultaneously considering both transition states by

where ktight was calculated by using a dual-level strategy described in detail below, while kloose was calculated by variable-reaction-coordinate variational transition state theory (VRC-TST) (Zheng et al., 2008; Bao et al., 2016a; Georgievskii and Klippenstein, 2003). In VRC-TST calculation, the reaction coordinate s is obtained by defining the distance between one pivot point on one reactant and the other pivot point on the other, and the dividing surface is defined by the pivot point connected to each reactant. The pivot point is located in a vector at a distance d from the centre of mass (COM) of the reactants, which is chosen to minimize the reaction rate. The vector connecting the pivot point to the centre of mass of reactant and is perpendicular to the plane of the reactant. The distance s between the pivot points was varied between 2.6 and 10 Å in steps of 0.1 Å to find the optimum value. Simultaneously, 500 Monte Carlo sampling points were used to sample single-faceted dividing surfaces. The VRC-TST calculation were performed by minimizing the rate constant by changing the distance between two pivot points and the location of the pivot points. The VRC-TST were performed using M06-CR/MG3S for Reaction (R1). However, the high-pressure-limited rate constants of the Reaction (R2) were calculated only by considering tight transition state s-TS1.

The dual-level strategy has been put forward and used in previous works (Long et al., 2022, 2018, 2019b; Xia et al., 2022; Gao et al., 2024; Long et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2023). The strategy combines the theory of conventional transition states (Glasstone et al., 1941) on the HL with the theory of canonical variational transition states (Garrett and Truhlar, 1979; Truhlar et al., 1982) on the LL and takes into account the small curvature tunnelling effect (Liu et al., 1993). In addition, the torsional anharmonicity factor was considered in our strategy (Long et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2023; Li and Long, 2024; Xie et al., 2024; Jiang et al., 2025). The rate constant is given by Eq. (3),

where is the rate constant without recrossing and tunneling effects calculated at HL. and ΓLL(T) is referred to tunneling transmission coefficient and recrossing transmission coefficient calculated by LL, respectively. is torsional anharmonicity factor calculated by using multi-structural method with coupled torsional potential and delocalized torsions (MS-T(CD) method) (Zheng and Truhlar, 2013; Chen et al., 2022). Three factors were calculated at the validated density functional methods at LL. Each calculated component present in Eq. (3) was provided in Tables S5 and S6.

2.4 Software

All density functional calculations were performed by using Gaussian 16 (Frisch et al., 2016) for geometry optimizations and frequency calculations and all coupled cluster calculations by using Molpro 2022 (Werner et al., 2012) and MRCC code (Kállay et al., 2020). Direct kinetics calculations were performed using Polyrate 2017 (Zheng et al., 2017b) and Gaussrate 2017-C (Zheng et al., 2017a). Torsional anharmonicity factor was calculated by using MSTor 2022 code (Zheng et al., 2012). And rate constants were calculated by Kisthelp program package (Canneaux et al., 2014).

3.1 Electronic Structure calculation results

3.1.1 The reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN

The reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN has not been reported in the literature. It is noted that there are three different functional groups (H-O, C ≡ N, and CH2) in HOCH2CN. Therefore, we explored four different mechanisms of CH2OO + HOCH2CN as described in Fig. 1. Three of them are similar to the CH2OO + CH3CN reaction, as they contain the same C-H and C ≡ N bonds (Zhang et al., 2022).

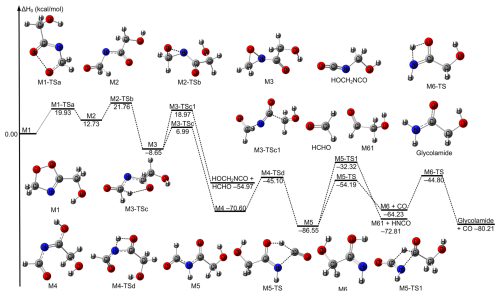

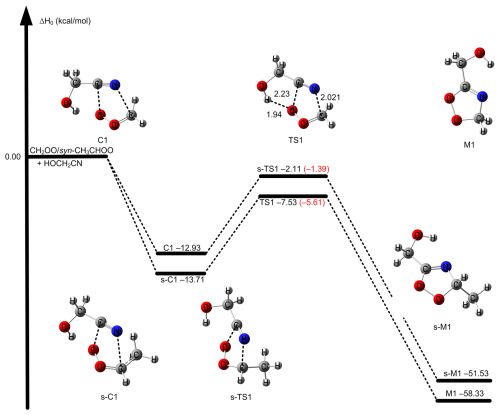

Figure 1The relative enthalpies at 0 K for the reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN. Values are given for all species as calculated by M11-L/MG3S.

The most feasible (first) mechanism leads to the formation of five-membered cyclic intermediate M1 via C ≡ N group addition to COO group in Fig. 1. Specifically, carbon atom of C ≡ N group in HOCH2CN is added to the terminal oxygen atom of CH2OO and N atom of C ≡ N group in HOCH2CN is added to the central carbon of CH2OO by the transition state TS1 (See Fig. 1). This mechanism is the same as CH2OO + CH3CN and is like that of the reaction between CH2OO and carbonyl group (Long et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2023; Chhantyal-Pun et al., 2018; Chung et al., 2019). We called the mechanism as carbon-oxygen addition coupled carbon-nitrogen addition mechanism. The second mechanism still occurs via five-membered cyclic transition states TS1a and TS1b responsible for the formation of M1a in Fig. 1. The H atom of the OH group in HOCH2CN is migrated to the terminal oxygen atom of CH2OO, and simultaneously the oxygen atom of OH group in HOCH2CN is added to the central carbon atom of CH2OO by TS1a and TS1b, which is similar to the reaction of CH2OO with molecules containing OH group such as H2O/H2O2/HOOCH2SCHO/CH3C(O)OOH/HOCl (Long et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2022; Long et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024; Xie et al., 2024). The third mechanism is the addition of C atom on the C ≡ N group in HOCH2CN to the central C atom of CH2OO and the N atom of C ≡ N group in HOCH2CN to the terminal O of CH2OO by TS1d. The last mechanism is that the H atom on the central CH2 group in HOCH2CN shifts to the terminal O atom of CH2OO and the C atom is added to the central C atom of CH2OO via TS1c, which leads to the formation of a peroxide. We mainly consider the most feasible mechanism in detail in this work because of TS1 is at least 5 kcal mol−1 lower than those of other reaction pathways by M11-L/MG3S (See Fig. 1). Moreover, the intermediate product M1 formed has a larger ΔH0 of −58.33 kcal mol−1 in Fig. 1. In addition, the calculated Gibbs free energy barriers at 298 K also show the five-ring closure reaction pathway via TS1 is the lowest in the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction (See Fig. S2); this reveals that entropy has a negligible effect on reaction mechanism.

We previously showed that CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVDZ-F12 can reach the accuracy of CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVTZ-F12 for geometrical optimization and frequency calculations for reactions containing C ≡ N groups (Long et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024, 2022). Therefore, we further show the reliability of DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ by using CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVDZ-F12. As a result, the difference between W2X//CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVDZ-F12 and W2X//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ shows that DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ is only 0.03 kcal mol−1 for of TS1 (See Table 1); this further shows that DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ is quantitatively reliable for geometrical optimizations and frequency calculations in the preset investigations.

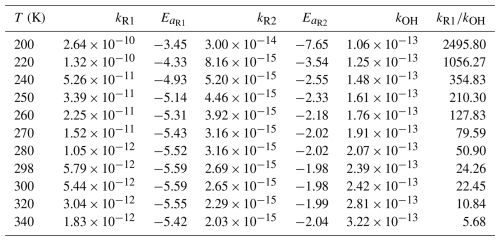

of Reaction (R1) via TS1 is computed to be −5.61 kcal mol−1 calculated by W3X-L//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ-F12, which is 5.25 lower than that of CH2OO + CH3CN (Zhang et al., 2022) calculated by W3X-L//CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVTZ-F12. The much lower via TS1 in Reaction (R1) leads to much faster rate constant of Reaction (R1), comparing with the CH2OO + CH3CN reaction. Simultaneously, we also found that of TS1 is 2.05 kcal mol−1 lower than that of the (CF3)2CFCN + CH2OO reaction calculated using the best estimate (Jiang et al., 2025). From geometrical point of view, the much lower via TS1 is due to the introduction of HO group in HOCH2CN, comparing with CH3CN; this remarkably change the reactivity of HOCH2CN toward CH2OO. We note that the introduction of OH group in HOCH2CN results in the formation of hydrogen bonding in TS1. The hydrogen bonding is formed via the interaction OH group in HOCH2CN with the terminal oxygen atom in CH2OO in TS1. The bond distance between the hydrogen atom of HO group in HOCH2CN and the terminal oxygen atom of CH2OO in TS1 is computed to be 1.942 Å by DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ (See Fig. 2); this shows the formation of hydrogen boning from geometrical point of view (Kar and Scheiner, 2004). The present results reveal that the hydrogen bonding interaction opens a way for decreasing .

Figure 2The relative enthalpies at 0 K for the reaction of CH2OO/syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN for Reactions (R1) and (R2). Values are given for all species as calculated by M11-L/MG3S, and in small parentheses and brackets, values are given for the transition state TS path as calculated by W3X-L//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ. The bond length in TS1 is in units of Å.

CCSD(T) has been considered as “gold standard” in the quantum chemical calculations. However, the previous investigations have shown that post-CCSD(T) is necessary to obtain quantitative reaction energy barriers for atmospheric reactions (Long et al., 2019b, 2016; Hansen et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2024). Here, we discuss the contribution of post-CCSD(T) calculations. The contribution of post-CCSD(T) is 0.58 kcal mol−1 from the difference between W3X-L and W2X of TS1, which is the same as the result of the reaction of CH2OO with CH3CN (0.58 kcal mol−1) and our previous estimated value (0.50 kcal mol−1) (Zhang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022). This shows that post-CCSD(T) calculations are necessary for obtaining quantitative for the reaction of Criegee intermediate with HOCH2CN. The MUD of M06-CR/MG3S is 0.23 kcal mol−1 for CH2OO and HOCH2CN in Table 1. Therefore, M06-CR/MG3S was chosen to perform direct kinetics calculation for the reaction of CH2OO with HOCH2CN.

Decomposition pathways for the formed product M1 have also been investigated at the M11-L/MG3S level; this is similar to the product decomposition pathway in the CH2OO + CH3CN reaction (Zhang et al., 2022). Firstly, the product M1 undergoes oxygen-oxygen bond cleavage via M1-TSa to result in forming a singlet biradical intermediate M2, which is similar to the reaction of CH2OO + HCHO (Jalan et al., 2013). Subsequently, the intermediate M2 undergoes the formation of carbon-nitrogen bonding to form a three-member ring with of 21.76 kcal mol−1 relative to M1 via the transition state M2-TSb. Then, the three-member ring intermediate M3 then undergoes two different reaction routes. One is open-ring coupled hydrogen shift to form M4 via the transition state M3-TSc. The other is analogous to that proposed by Franzon et al. (2023), which is an open-ring coupled bond breaking to form HCHO and HOCH2NCO via the transition state M3-TSc1. However, for M3-TS3c is 11.97 kcal mol−1 lower than that of M3-TSc1. Therefore, M3-TSc is the dominant reaction pathway for the unimolecular reaction of M3. Moreover, IRC calculations also show that M3-TSc connects well with M3 as described in Fig. S3. Subsequently, the H atom of the intermediate OH on intermediate M4 is transferred to the N atom to yield the intermediate species M5. Then, the process was depicted in Fig. 3. The calculated enthalpy of reaction at 0 K of M5 is −86.55 kcal mol−1, indicating the unimolecular isomerization is thermodynamically driven. Intermediate M5 undergoes unimolecular isomerization via two different pathways. In the first pathway, an intramolecular hydrogen transfer from the aldehyde group to the central carbonyl oxygen is followed by C–N bond cleavage, yielding CO and intermediate M6. Then, hydrogen shift of OH in M6 to NH group leads to the formation of glycolamide. Alternatively, a second pathway involves hydrogen migration from the aldehyde group to the central carbon atom, accompanied by C–N bond rupture, producing HNCO and glycolaldehyde. The formation of carbon monoxide proceeds with a significantly lower activation enthalpy (−54.19 kcal mol−1) compared to that for glycolaldehyde (−32.32 kcal mol−1), indicating that the CO-forming channel is kinetically favoured. Furthermore, the rate-determining step for the formation of the final product from the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction has been identified as the initial step, which is similar to the reaction of alkenes with ozone (Nguyen et al., 2015).

3.1.2 The reaction of syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN

The reaction of syn-CH3CHOO with HOCH2CN has been also studied by considering similar mechanisms for the reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN. The HL calculation of of s-TS1 was performed by employing an approximation method, as listed in Eq. (1), which is discussed in method section. The lowest energy route is depicted in Fig. 2 and details can be found in Fig. S1. of s-TS1 is −1.39 kcal mol−1 calculated by HL calculation, which is 4.22 kcal mol−1 higher than that of TS1. The lower reactivity of syn-CH3CHOO than CH2OO results in the much slower reaction of syn-CH3CHOO with HOCH2CN. However, for s-TS1 is 5.45 kcal mol−1 is lower than the reaction of syn-CH3CHOO + CH3CN calculated by W3X-L//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ; this again shows that the introduction of OH group in HOCH2CN can significantly reduce toward Criegee intermediates. However, the decrease in value of 5.45 kcal mol−1 between syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN and syn-CH3CHOO + CH3CN is different from the corresponding value of 5.25 kcal mol−1 between CH2OO + HOCH2CN and CH2OO + CH3CN; this indicates that the change in is not only determined by the change from CH3CN to HOCH2CN, but also determined by the change from CH2OO to syn-CH3CHOO. We also found that the MUD between the HL result and M11-L/MG3S is only 0.72 kcal mol−1. Therefore, the combination of M11-L functional method with MG3S basis set was chose to perform direct kinetics calculations.

3.2 Kinetics

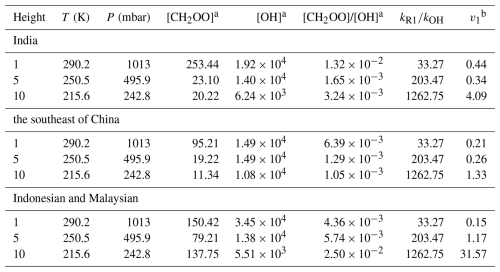

The rate constants for Reactions (R1) and (R2) have been calculated and listed in Table 2. The details are listed in Tables S5 and S6. We have fitted the calculated rate constants by Eq. (3).

Here, T is temperature in Kelvin and R is ideal gas constant (0.0019872 kcal mol−1 K−1). The fitting parameters A, n, E, and T0 were listed in Table S7. The temperature-dependent Arrhenius activation energy have been fitted by using Eq. (4) as listed in Table 3, which provides the phenomenological characteristics of temperature dependence of the rate constants.

The calculated rate constants for kR1 are decreased from to cm3 molec.−1 s−1 at 200–340 K in Table 2, which shows significant negative temperature dependence. The temperature dependent activation energies are decreased from −3.45 to −5.32 kcal mol−1 at 200–340 K, which provides the evidence for the negative temperature dependence of the rate constants of Reaction (R1). The rate constant for the reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN is cm3 molec.−1 s−1 at 298 K, which is 24 times larger than the rate constant for the reaction of OH + HOCH2CN at 298 K (Marshall and Burkholder, 2024). In particular, we have found that the rate constants of Reaction (R1) is two magnitude order faster than the reaction of OH + HOCH2CN when temperature below 260 K (See Table 2).

Table 2The rate constants (cm3 molec.−1 s−1) and activation energies (kcal mol−1) for the CH2OO/syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN reactions at different temperatures.

The rate constant of the Reaction (R2) ranges from to cm3 molec.−1 s−1 in the temperature range 200–340 K, which exhibits weak negative temperature dependence. As a result, we found that syn-CH3CHOO make a minor contribution for the sink of HOCH2CN because the rate constants of syn-CH3CHOO + HOCH2CN are always lower than those of the reaction of OH + HOCH2CN at 200–340 K. However, the rate constant of Reaction (R2) is cm3 molec.−1 s−1 at 298 K, which is two orders of magnitude slower than the rate constant of the reaction of OH + HOCH2CN and two orders of magnitude larger than that of the reaction of syn-CH3CHOO + CH3CN, suggesting that the contribution of syn-CH3CHOO to the sink of HOCH2CN is small, yet this reaction is more favourable than that for the reaction of syn-CH3CHOO + CH3CN in the atmosphere (Zhang et al., 2022). Therefore, we do not consider the contribution of syn-CH3CHOO to HOCH2CN in the atmosphere. Furthermore, for this barrierless reaction between small molecules where the torsional degrees of freedom undergo minimal change, the effects of recrossing, quantum tunnelling, and torsional anharmonicity are expected to be negligible This expectation is confirmed by our calculations, which show that the corresponding coefficients are all close to unity, as listed in Tables S5 and S6.

3.3 Atmospheric implications

The reaction of OH with HOCH2CN has been investigated in previous work (Marshall and Burkholder, 2024). Therefore, we considered the competition between the Reaction (R1) and the OH + HOCH2CN reaction by comparing with their rate ratios followed by Eq. (5),

where kR1 is referred to the rate constants of the reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN, kOH is rate constants of the reaction of OH with HOCH2CN from the literature (Marshall and Burkholder, 2024).

In the atmosphere, Vereecken et al. (2017) have evaluated that the concentrations for stabilized Criegee intermediates are in the range between 104 and 105 molec. cm−3, especially in the Amazon rainforest region, where sCls could reach a maximum concentration of 105 molec. cm−3 (Vereecken et al., 2017). Typically, the concentration of OH varies between 104 and 106 molec. cm−3 (Ren et al., 2003; Stone et al., 2012; Lelieveld et al., 2016). However, due to the consideration of reactions CH2OO with H2O and (H2O)2, the CH2OO concentration in the GEOS-Chem model simulations is always an order of magnitude less than the results of Vereecken et al. (2017). Therefore, we consider the rate ratios between CH2OO + HOCH2CN and OH + HOCH2CN at different concentrations of CH2OO and OH at 200–340 K in Table 3, and further discuss the atmospheric implications based on global atmospheric chemistry model GEOS-Chem.

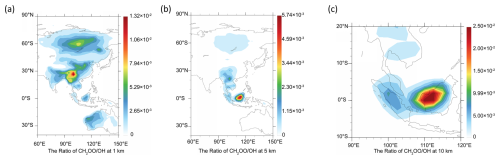

Table 3The concentration ratio of CH2OO to OH at different heights from different region in GEOS-Chem.

a The data were extracted in the work of Long et al. (2024). b The product of rate ratio and concentration ratio.

The competition between the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction and the OH + HOCH2CN reaction is determined by two factors, one is the rate constant ratio and the other is the concentration ratio. The concentration ratio decreases with increasing altitude until two orders of magnitude are observed at 10 km in the Indonesian and Malaysian regions. It is noted that when the altitude increases, the atmospheric temperature is remarkably decreased. The atmospheric temperatures are 250.5–198 K at the altitudes from 5–15 km. The results show that although the concentration ratio of two orders of magnitude, CH2OO does make some contribution to the sink of HOCH2CN at 1 km. At 10 km, CH2OO + HOCH2CN can completely dominate over the OH + HOCH2CN reaction in India, southeast China, Indonesia, and Malaysian region (See Table 3 and Fig. 4). However, CH2OO only dominates over the sink of HOCH2CN in the Indonesian and Malaysian regions due to the relatively large ratio of rate constants and concentration ratios at low temperatures at 5 km. Using the model data, we find that the sink of CH2OO to HOCH2CN has strong geographical and sensitivity to altitude (See Fig. 4).

Figure 4The ratio of CH2OO to OH at night from literature (Long et al., 2024) (a) at 1 km, (b) at 5 km, (c) at 10 km, (d) at 15 km.

The reaction products of HOCH2CN with OH radicals exhibit significant differences from those formed by the reaction of CH2OO with HOCH2CN. The main products of the HOCH2CN + OH reaction are H2O and the HOC(H)CN radical, which subsequently reacts with O2 to yield HO2 and formyl cyanide (HC(O)CN) (Marshall and Burkholder, 2024). In contrast, the reaction of HOCH2CN with CH2OO proceeds through chemical transformation processes, ultimately forming CO and glycolamide. Glycolamide is an amide, which can contribute to the formation of secondary organic aerosols and an important interstellar molecule (Joshi and Lee, 2025; Sanz-Novo et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2016).

Wildfires have attracted the attention of researchers due to their impact on aerosols and the ozone layer, which can lead to adverse effects on the environment and human health. HOCH2CN is a harmful species present in wildfires. Thus, it is necessary to study its atmospheric chemical processes. The quantitative kinetics for reactions of Criegee intermediates with HOCH2CN have been investigated by using specific computational strategies for electronic structure calculations and dual-level strategy for kinetics calculations coupled with atmospheric chemistry transport model analysis. The high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations were performed by using W3X-L//DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ-F12 for reaction of Reaction (R1) close to CCSDT(Q)/CBS accuracy and an approximation strategy to reach W3X-L accuracy for Reaction (R2). Additionally, CCSD(T)-F12a/cc-pVDZ-F12 was used to verified the reliability of DF-CCSD(T)-F12b/jun-cc-pVDZ-F12 for Reaction (R1). Four mechanisms were found for the reactions of CH2OO and HOCH2CN, with the lowest energy pathway called carbon-oxygen addition coupled carbon-nitrogen addition. We find an unprecedentedly low of −5.61 kcal mol−1 for the reactions of CH2OO with C ≡ N group of atmospheric species. Simultaneously, we show that the final product in the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction is glycolamide and CO, where glycolamide could contribution to the formation of secondary organic aerosols. The present findings uncover that the post-CCSD(T) is necessary to obtain quantitative because its contribution is 0.58 kcal mol−1. However, we also find that all the factors contain anharmonicity, recrossing and tunneling, torsional anharmonicity effects, which are negligible for obtaining quantitative rate constants. The rate constants for the CH2OO with HOCH2CN increase from 3.18 × 10−10 to 2.25 × 10−11 cm3 molec.−1 s−1, which is two orders of magnitude higher than the reaction of OH + HOCH2CN below 260 K. Therefore, the reaction of CH2OO with HOCH2CN dominates over the sinks of HOCH2CN in southeast China, northern India at 5 km and in the Indonesian and Malaysian regions at 5 and 10 km. This work provides a new insight into the role of Criegee intermediate in the removal of HOCH2CN.

All raw data can be provided by the corresponding authors upon request.

The following information is provided in the Supplement: Standard scale factors and Specific Reaction Scale Factors; The activate enthalpies at 0 K for the CH2OO + HOCH2CN reaction at different methods; The anharmonicity effect for the enthalpy of activation; The rate constants of the reaction of Reactions (R1) and (R2); The fitting parameters for k1 and k2; The ratio of the rate constants at various temperatures and different concentration; Absolute energies (Hartree) and the Cartesian coordinates (Å) of the optimized geometries; The relative enthalpies at 0 K for the reaction of CH2OO + HOCH2CN. The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-17399-2025-supplement.

Chaolu Xie performed the calculations, analysed and interpretation of data, and wrote the manuscript draft. Shunyu Li performed the calculations. Bo Long designed the project, analysed and interpretation of data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We also thank the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute for computational resources.

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42120104007 and 41775125) and by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects, China (CXTD 2022001 and GCC 2023026).

This paper was edited by Dantong Liu and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bao, J. L. and Truhlar, D. G.: Variational transition state theory: theoretical framework and recent developments, Chem. Soc. Rev., 46, 7548–7596, https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CS00602K, 2017.

Bao, J. L., Zhang, X., and Truhlar, D. G.: Barrierless association of CF2 and dissociation of C2F4 by variational transition-state theory and system-specific quantum Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel theory, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 113, 13606–13611, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1616208113, 2016a.

Bao, J. L., Zheng, J., and Truhlar, D. G.: Kinetics of Hydrogen Radical Reactions with Toluene Including Chemical Activation Theory Employing System-Specific Quantum RRK Theory Calibrated by Variational Transition State Theory, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 138, 2690–2704, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b11938, 2016b.

Bernath, P., Boone, C., and Crouse, J.: Wildfire smoke destroys stratospheric ozone, Science, 375, 1292–1295, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm5611, 2022.

Bucher, J. R.: Methyl isocyanate: A review of health effects research since Bhopal, Fundam. Appl. Toxicol., 9, 367–379, https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-0590(87)90019-4, 1987.

Bunnelle, W. H.: Preparation, properties, and reactions of carbonyl oxides, Chem. Rev., 91, 335–362, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr00003a003, 1991.

Canneaux, S., Bohr, F., and Henon, E.: KiSThelP: A program to predict thermodynamic properties and rate constants from quantum chemistry results, J. Comput. Chem., 35, 82–93, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.23470, 2014.

Chan, B. and Radom, L.: W2X and W3X-L: Cost-Effective Approximations to W2 and W4 with kJ mol−1 Accuracy, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 11, 2109–2119, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00135, 2015.

Chen, W., Zhang, P., Truhlar, D. G., Zheng, J., and Xu, X.: Identification of Torsional Modes in Complex Molecules Using Redundant Internal Coordinates: The Multistructural Method with Torsional Anharmonicity with a Coupled Torsional Potential and Delocalized Torsions, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 18, 7671–7682, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00952, 2022.

Chhantyal-Pun, R., Rotavera, B., McGillen, M. R., Khan, M. A. H., Eskola, A. J., Caravan, R. L., Blacker, L., Tew, D. P., Osborn, D. L., Percival, C. J., Taatjes, C. A., Shallcross, D. E., and Orr-Ewing, A. J.: Criegee Intermediate Reactions with Carboxylic Acids: A Potential Source of Secondary Organic Aerosol in the Atmosphere, ACS Earth Space Chem., 2, 833–842, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.8b00069, 2018.

Chhantyal-Pun, R., Khan, M. A. H., Taatjes, C. A., Percival, C. J., Orr-Ewing, A. J., and Shallcross, D. E.: Criegee intermediates: production, detection and reactivity, Int. Rev. Phys. Chem., 39, 385–424, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144235X.2020.1792104, 2020a.

Chhantyal-Pun, R., Khan, M. A. H., Zachhuber, N., Percival, C. J., Shallcross, D. E., and Orr-Ewing, A. J.: Impact of Criegee Intermediate Reactions with Peroxy Radicals on Tropospheric Organic Aerosol, ACS Earth Space Chem., 4, 1743–1755, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00147, 2020b.

Chung, C.-A., Su, J. W., and Lee, Y.-P.: Detailed mechanism and kinetics of the reaction of Criegee intermediate CH2OO with HCOOH investigated via infrared identification of conformers of hydroperoxymethyl formate and formic acid anhydride, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 21, 21445–21455, https://doi.org/10.1039/C9CP04168K, 2019.

Criegee, R.: Mechanism of Ozonolysis, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 14, 745–752, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.197507451, 1975.

Docherty, K. S., Wu, W., Lim, Y. B., and Ziemann, P. J.: Contributions of Organic Peroxides to Secondary Aerosol Formed from Reactions of Monoterpenes with O3, Environ Sci Technol., 39, 4049–4059, https://doi.org/10.1021/es050228s, 2005.

Etz, B. D., Woodley, C. M., and Shukla, M. K.: Reaction mechanisms for methyl isocyanate (CH3NCO) gas-phase degradation, J. Hazard. Mater., 473, 134628, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134628, 2024.

Finewax, Z., Chattopadhyay, A., Neuman, J. A., Roberts, J. M., and Burkholder, J. B.: Calibration of hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN) and methyl isocyanate (CH3NCO) isomers using I− chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS), Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 6865–6873, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-6865-2024, 2024.

Foreman, E. S., Kapnas, K. M., and Murray, C.: Reactions between Criegee intermediates and the inorganic acids HCl and HNO3: Kinetics and atmospheric implications, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 128, 10575–10578, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201604662, 2016.

Franzon, L., Peltola, J., Valiev, R., Vuorio, N., Kurtén, T., and Eskola, A.: An Experimental and Master Equation Investigation of Kinetics of the CH2OO + RCN Reactions (R = H, CH3, C2H5) and Their Atmospheric Relevance, J. Phys. Chem. A, 127, 477–488, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c07073, 2023.

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Caricato, M., Li, X., Hratchian, H. P., Izmaylov, A. F., Bloino, J., Zheng, G., Sonnenberg, J. L., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Montgomery, J. A., Peralta, J. E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M., Heyd, J. J., Brothers, E., Kudin, K. N., Staroverov, V. N., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A., Burant, J. C., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Rega, N., Millam, J. M., Klene, M., Knox, J. E., Cross, J. B., Bakken, V., Adamo, C., Jaramillo, J., Gomperts, R., Stratmann, R. E., Yazyev, O., Austin, A. J., Cammi, R., Pomelli, C., Ochterski, J. W., Martin, R. L., Morokuma, K., Zakrzewski, V. G., Voth, G. A., Salvador, P., Dannenberg, J. J., Dapprich, S., Daniels, A. D., Farkas, O., Foresman, J. B., Ortiz, J. V., Cioslowski, J., and Fox, D. J.: Gaussian 16, Revision A.03, Gaussian Inc, Wallingford CT, https://gaussian.com/gaussian16/ (last access: 20 November 2023), 2016.

Gao, Q., Shen, C., Zhang, H., Long, B., and Truhlar, D. G.: Quantitative kinetics reveal that reactions of HO2 are a significant sink for aldehydes in the atmosphere and may initiate the formation of highly oxygenated molecules via autoxidation, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 26, 16160–16174, https://doi.org/10.1039/D4CP00693C, 2024.

Garrett, B. C. and Truhlar, D. G.: Criterion of minimum state density in the transition state theory of bimolecular reactions, J. Chem. Phys., 70, 1593–1598, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.437698, 1979.

Garrett, B. C. and Truhlar, D. G.: Canonical unified statistical model. Classical mechanical theory and applications to collinear reactions, J. Chem. Phys., 76, 1853–1858, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.443157, 1982.

Georgievskii, Y. and Klippenstein, S. J.: Variable reaction coordinate transition state theory: Analytic results and application to the C2H3+H → C2H4 reaction, J. Chem. Phys., 118, 5442–5455, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1539035, 2003.

Glasstone, S., Laidler, K. J., and Eyring, H.: The Theory of Rate Processes: The Kinetics of Chemical Reactions, Viscosity, Diffusion and Electrochemical Phenomena, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Incorporated, 1st Edn., ISBN 13 9780070233607, 1941.

Győrffy, W. and Werner, H.-J.: Analytical energy gradients for explicitly correlated wave functions. II. Explicitly correlated coupled cluster singles and doubles with perturbative triples corrections: CCSD(T)-F12, J. Chem. Phys., 148, 114104, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5020436, 2018.

Hansen, A. S., Qian, Y., Sojdak, C. A., Kozlowski, M. C., Esposito, V. J., Francisco, J. S., Klippenstein, S. J., and Lester, M. I.: Rapid Allylic 1,6 H-Atom Transfer in an Unsaturated Criegee Intermediate, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 144, 5945–5955, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c00055, 2022.

Inomata, S., Sato, K., Hirokawa, J., Sakamoto, Y., Tanimoto, H., Okumura, M., Tohno, S., and Imamura, T.: Analysis of secondary organic aerosols from ozonolysis of isoprene by proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ., 97, 397–405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.03.045, 2014.

Jalan, A., Allen, J. W., and Green, W. H.: Chemically activated formation of organic acids in reactions of the Criegee intermediate with aldehydes and ketones, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 15, 16841–16852, https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP52598H, 2013.

Jiang, H., Xie, C., Liu, Y., Xiao, C., Zhang, W., Li, H., Long, B., Dong, W., Truhlar, D. G., and Yang, X.: Criegee Intermediates Significantly Reduce Atmospheric (CF3)2CFCN, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 147, 12263–12272, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c01737, 2025.

Joshi, P. R. and Lee, Y.-P.: Identification of the HOCHC(O)NH2 Radical Intermediate in the Reaction of H + Glycolamide in Solid Para-Hydrogen and Its Implication to the Interstellar Formation of Higher-Order Amides and Polypeptides, ACS Earth Space Chem., 9, 769–781, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.4c00409, 2025.

Kállay, M., Nagy, P. R., Mester, D., Rolik, Z., Samu, G., Csontos, J., Csóka, J., Szabó, P. B., Gyevi-Nagy, L., Hégely, B., Ladjánszki, I., Szegedy, L., Ladóczki, B., Petrov, K., Farkas, M., Mezei, P. D., and Ganyecz, Á.: The MRCC program system: Accurate quantum chemistry from water to proteins, J. Chem. Phys., 152, 074107, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5142048, 2020.

Kar, T. and Scheiner, S.: Comparison of Cooperativity in CH O and OH O Hydrogen Bonds, J. Phys. Chem. A, 108, 9161–9168, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp048546l, 2004.

Katich, J. M., Apel, E. C., Bourgeois, I., Brock, C. A., Bui, T. P., Campuzano-Jost, P., Commane, R., Daube, B., Dollner, M., Fromm, M., Froyd, K. D., Hills, A. J., Hornbrook, R. S., Jimenez, J. L., Kupc, A., Lamb, K. D., McKain, K., Moore, F., Murphy, D. M., Nault, B. A., Peischl, J., Perring, A. E., Peterson, D. A., Ray, E. A., Rosenlof, K. H., Ryerson, T., Schill, G. P., Schroder, J. C., Weinzierl, B., Thompson, C., Williamson, C. J., Wofsy, S. C., Yu, P., and Schwarz, J. P.: Pyrocumulonimbus affect average stratospheric aerosol composition, Science, 379, 815–820, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add3101, 2023.

Khan, M. A. H., Percival, C. J., Caravan, R. L., Taatjes, C. A., and Shallcross, D. E.: Criegee intermediates and their impacts on the troposphere, Environ. Sci-Proc. Imp., 20, 437–453, https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EM00585G, 2018.

Koss, A. R., Sekimoto, K., Gilman, J. B., Selimovic, V., Coggon, M. M., Zarzana, K. J., Yuan, B., Lerner, B. M., Brown, S. S., Jimenez, J. L., Krechmer, J., Roberts, J. M., Warneke, C., Yokelson, R. J., and de Gouw, J.: Non-methane organic gas emissions from biomass burning: identification, quantification, and emission factors from PTR-ToF during the FIREX 2016 laboratory experiment, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 3299–3319, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-3299-2018, 2018.

Kroll, J. H., Donahue, N. M., Cee, V. J., Demerjian, K. L., and Anderson, J. G.: Gas-Phase Ozonolysis of Alkenes: Formation of OH from Anti Carbonyl Oxides, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 8518–8519, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0266060, 2002.

Kukui, A., Chartier, M., Wang, J., Chen, H., Dusanter, S., Sauvage, S., Michoud, V., Locoge, N., Gros, V., Bourrianne, T., Sellegri, K., and Pichon, J.-M.: Role of Criegee intermediates in the formation of sulfuric acid at a Mediterranean (Cape Corsica) site under influence of biogenic emissions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 13333–13351, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-13333-2021, 2021.

Lelieveld, J., Gromov, S., Pozzer, A., and Taraborrelli, D.: Global tropospheric hydroxyl distribution, budget and reactivity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 12477–12493, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-12477-2016, 2016.

Lester, M. I. and Klippenstein, S. J.: Unimolecular Decay of Criegee Intermediates to OH Radical Products: Prompt and Thermal Decay Processes, Acc. Chem. Res., 51, 978–985, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00077, 2018.

Li, J. and Long, B.: Dual-level strategy for quantitative kinetics for the reaction between ethylene and hydroxyl radical, J. Chem. Phys., 160, 174301, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0200107, 2024.

Liu, Y. P., Lynch, G. C., Truong, T. N., Lu, D. H., Truhlar, D. G., and Garrett, B. C.: Molecular modeling of the kinetic isotope effect for the [1,5]-sigmatropic rearrangement of cis-1,3-pentadiene, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 115, 2408–2415, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00059a041, 1993.

Long, B., Cheng, J., Tan, X., and Zhang, W.: Theoretical study on the detailed reaction mechanisms of carbonyl oxide with formic acid, J. Mol. Struc-THEOCHEM, 916, 159–167, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theochem.2009.09.028, 2009.

Long, B., Bao, J. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: Atmospheric Chemistry of Criegee Intermediates: Unimolecular Reactions and Reactions with Water, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 138, 14409–14422, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b08655, 2016.

Long, B., Bao, J. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: Unimolecular reaction of acetone oxide and its reaction with water in the atmosphere, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 115, 6135–6140, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804453115, 2018.

Long, B., Bao, J. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: Kinetics of the Strongly Correlated CH3O + O2 Reaction: The Importance of Quadruple Excitations in Atmospheric and Combustion Chemistry, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 141, 611–617, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b11766, 2019a.

Long, B., Bao, J. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: Rapid unimolecular reaction of stabilized Criegee intermediates and implications for atmospheric chemistry, Nat. Commun., 10, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09948-7, 2019b.

Long, B., Wang, Y., Xia, Y., He, X., Bao, J. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: Atmospheric Kinetics: Bimolecular Reactions of Carbonyl Oxide by a Triple-Level Strategy, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 143, 8402–8413, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c02029, 2021.

Long, B., Xia, Y., and Truhlar, D. G.: Quantitative Kinetics of HO2 Reactions with Aldehydes in the Atmosphere: High-Order Dynamic Correlation, Anharmonicity, and Falloff Effects Are All Important, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 144, 19910–19920, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c07994, 2022.

Long, B., Xia, Y., Zhang, Y.-Q., and Truhlar, D. G.: Kinetics of Sulfur Trioxide Reaction with Water Vapor to Form Atmospheric Sulfuric Acid, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 145, 19866–19876, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c06032, 2023.

Long, B., Zhang, Y.-Q., Xie, C.-L., Tan, X.-F., and Truhlar, D. G.: Reaction of Carbonyl Oxide with Hydroperoxymethyl Thioformate: Quantitative Kinetics and Atmospheric Implications, Research, 7, 0525, https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0525, 2024.

Luo, P. L., Chen, I. Y., Khan, M. A. H., and Shallcross, D. E.: Direct gas-phase formation of formic acid through reaction of Criegee intermediates with formaldehyde, Commun. Chem., 6, 130, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-023-00933-2, 2023.

Ma, C., Su, H., Lelieveld, J., Randel, W., Yu, P., Andreae, M. O., and Cheng, Y.: Smoke-charged vortex doubles hemispheric aerosol in the middle stratosphere and buffers ozone depletion, Sci. Adv., 10, eadn3657, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adn3657, 2024.

Marshall, P. and Burkholder, J. B.: Kinetics and Thermochemistry of Hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN) and Its Reaction with Hydroxyl Radical, ACS Earth Space Chem., 8, 1933–1941, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.4c00176, 2024.

Mattila, J. M., Arata, C., Wang, C., Katz, E. F., Abeleira, A., Zhou, Y., Zhou, S., Goldstein, A. H., Abbatt, J. P. D., DeCarlo, P. F., and Farmer, D. K.: Dark Chemistry during Bleach Cleaning Enhances Oxidation of Organics and Secondary Organic Aerosol Production Indoors, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 7, 795–801, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00573, 2020.

Mehta, P. S., Mehta, A. S., Mehta, S. J., and Makhijani, A. B.: Bhopal Tragedy's Health Effects: A Review of Methyl Isocyanate Toxicity, J. Am. Med. Assoc., 264, 2781–2787, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1990.03450210081037, 1990.

Newland, M. J., Rickard, A. R., Sherwen, T., Evans, M. J., Vereecken, L., Muñoz, A., Ródenas, M., and Bloss, W. J.: The atmospheric impacts of monoterpene ozonolysis on global stabilised Criegee intermediate budgets and SO2 oxidation: experiment, theory and modelling, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 6095–6120, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-6095-2018, 2018.

Nguyen, T. L., Lee, H., Matthews, D. A., McCarthy, M. C., and Stanton, J. F.: Stabilization of the Simplest Criegee Intermediate from the Reaction between Ozone and Ethylene: A High-Level Quantum Chemical and Kinetic Analysis of Ozonolysis, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 5524–5533, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b02088, 2015.

Novelli, A., Vereecken, L., Lelieveld, J., and Harder, H.: Direct observation of OH formation from stabilised Criegee intermediates, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 16, 19941–19951, https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP02719A, 2014.

Osborn, D. L. and Taatjes, C. A.: The physical chemistry of Criegee intermediates in the gas phase, Int. Rev. Phys. Chem., 34, 309–360, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144235X.2015.1055676, 2015.

Papanastasiou, D. K., Bernard, F., and Burkholder, J. B.: Atmospheric Fate of Methyl Isocyanate, CH3NCO: OH and Cl Reaction Kinetics and Identification of Formyl Isocyanate, HC(O)NCO, ACS Earth Space Chem., 4, 1626–1637, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00157, 2020.

Parker, T. M., Burns, L. A., Parrish, R. M., Ryno, A. G., and Sherrill, C. D.: Levels of symmetry adapted perturbation theory (SAPT). I. Efficiency and performance for interaction energies, J. Chem. Phys., 140, 094106, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4867135, 2014.

Peltola, J., Seal, P., Inkilä, A., and Eskola, A.: Time-resolved, broadband UV-absorption spectrometry measurements of Criegee intermediate kinetics using a new photolytic precursor: unimolecular decomposition of CH2OO and its reaction with formic acid, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 22, 11797–11808, https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CP00302F, 2020.

Peverati, R. and Truhlar, D. G.: M11-L: A Local Density Functional That Provides Improved Accuracy for Electronic Structure Calculations in Chemistry and Physics, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 3, 117–124, https://doi.org/10.1021/jz201525m, 2012.

Priestley, M., Le Breton, M., Bannan, T. J., Leather, K. E., Bacak, A., Reyes-Villegas, E., De Vocht, F., Shallcross, B. M. A., Brazier, T., Anwar Khan, M., Allan, J., Shallcross, D. E., Coe, H., and Percival, C. J.: Observations of Isocyanate, Amide, Nitrate, and Nitro Compounds From an Anthropogenic Biomass Burning Event Using a ToF-CIMS, J. Geophys. Res-Atmos., 123, 7687–7704, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JD027316, 2018.

Ren, X., Harder, H., Martinez, M., Lesher, R. L., Oliger, A., Simpas, J. B., Brune, W. H., Schwab, J. J., Demerjian, K. L., He, Y., Zhou, X., and Gao, H.: OH and HO2 Chemistry in the urban atmosphere of New York City, Atmos. Environ., 37, 3639–3651, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(03)00459-X, 2003.

Sanz-Novo, M., Belloche, A., Alonso, J. L., Kolesniková, L., Garrod, R. T., Mata, S., Müller, H. S. P., Menten, K. M., and Gong, Y.: Interstellar glycolamide: A comprehensive rotational study and an astronomical search in Sgr, Astron. Astrophys., 639, A135, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202038149, 2020.

Stone, D., Whalley, L. K., and Heard, D. E.: Tropospheric OH and HO2 radicals: field measurements and model comparisons, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6348–6404, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CS35140D, 2012.

Sun, Y., Long, B., and Truhlar, D. G.: Unimolecular Reactions of E-Glycolaldehyde Oxide and Its Reactions with One and Two Water Molecules, Research, 6, 0143, https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0143, 2023.

Truhlar, D. G., Isaacson, A. D., Skodje, R. T., and Garrett, B. C.: Incorporation of quantum effects in generalized-transition-state theory, J. Phys. Chem., 86, 2252–2261, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100209a021, 1982.

Vereecken, L., Novelli, A., and Taraborrelli, D.: Unimolecular decay strongly limits the atmospheric impact of Criegee intermediates, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 19, 31599–31612, https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CP05541B, 2017.

Wang, C., Mattila, J. M., Farmer, D. K., Arata, C., Goldstein, A. H., and Abbatt, J. P. D.: Behavior of Isocyanic Acid and Other Nitrogen-Containing Volatile Organic Compounds in The Indoor Environment, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 7598–7607, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c08182, 2022a.

Wang, G., Iradukunda, Y., Shi, G., Sanga, P., Niu, X., and Wu, Z.: Hydroxyl, hydroperoxyl free radicals determination methods in atmosphere and troposphere, J. Environ. Sci., 99, 324–335, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2020.06.038, 2021.

Wang, P., Truhlar, D. G., Xia, Y., and Long, B.: Temperature-dependent kinetics of the atmospheric reaction between CH2OO and acetone, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 24, 13066–13073, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CP01118B, 2022b.

Werner, H.-J., Knowles, P. J., Knizia, G., Manby, F. R., and Schütz, M.: Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package, WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci., 2, 242–253, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.82, 2012.

Worthy, W.: Methyl Isocyanate: The Chemistry of a Hazard, Chem. Eng. News Archive, 63, 27–33, https://doi.org/10.1021/cen-v063n006.p027, 1985.

Xia, Y., Long, B., Lin, S., Teng, C., Bao, J. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: Large Pressure Effects Caused by Internal Rotation in the s-cis-syn-Acrolein Stabilized Criegee Intermediate at Tropospheric Temperature and Pressure, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 144, 4828–4838, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c12324, 2022.

Xia, Y., Long, B., Liu, A., and Truhlar, D. G.: Reactions with Criegee intermediates are the dominant gas-phase sink for formyl fluoride in the atmosphere, Fundam. Res., 4, 1216–1224, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2023.02.012, 2024.

Xie, C., Yang, H., and Long, B.: Reaction between peracetic acid and carbonyl oxide: Quantitative kinetics and insight into implications in the atmosphere, Atmos. Environ., 341, 120928, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2024.120928, 2024.

Yao, L., Wang, M. Y., Wang, X. K., Liu, Y. J., Chen, H. F., Zheng, J., Nie, W., Ding, A. J., Geng, F. H., Wang, D. F., Chen, J. M., Worsnop, D. R., and Wang, L.: Detection of atmospheric gaseous amines and amides by a high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometer with protonated ethanol reagent ions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 14527–14543, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-14527-2016, 2016.

Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Truhlar, D. G., and Xu, X.: Nonmonotonic Temperature Dependence of the Pressure-Dependent Reaction Rate Constant and Kinetic Isotope Effect of Hydrogen Radical Reaction with Benzene Calculated by Variational Transition-State Theory, J. Phys. Chem. A, 121, 9033–9044, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.7b09374, 2017.

Zhang, L., Truhlar, D. G., and Sun, S.: Association of Cl with C2H2 by unified variable-reaction-coordinate and reaction-path variational transition-state theory, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 117, 5610–5616, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920018117, 2020.

Zhang, Y., Xu, R., Huang, W., Ye, T., Yu, P., Yu, W., Wu, Y., Liu, Y., Yang, Z., Wen, B., Ju, K., Song, J., Abramson, M. J., Johnson, A., Capon, A., Jalaludin, B., Green, D., Lavigne, E., Johnston, F. H., Morgan, G. G., Knibbs, L. D., Zhang, Y., Marks, G., Heyworth, J., Arblaster, J., Guo, Y. L., Morawska, L., Coelho, M. S. Z. S., Saldiva, P. H. N., Matus, P., Bi, P., Hales, S., Hu, W., Phung, D., Guo, Y., and Li, S.: Respiratory risks from wildfire-specific PM2.5 across multiple countries and territories, Nat. Sustain., 8, 474–484, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01533-9, 2025.

Zhang, Y. Q., Xia, Y., and Long, B.: Quantitative kinetics for the atmospheric reactions of Criegee intermediates with acetonitrile, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 24, 24759–24766, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CP02849B, 2022.

Zhang, Y. Q., Francisco, J. S., and Long, B.: Rapid Atmospheric Reactions between Criegee Intermediates and Hypochlorous Acid, J. Phys. Chem. A, 128, 909–917, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.3c06144, 2024.

Zhao, Y., Lynch, B. J., and Truhlar, D. G.: Multi-coefficient extrapolated density functional theory for thermochemistry and thermochemical kinetics, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 7, 43–52, https://doi.org/10.1039/B416937A, 2005.

Zhao, Y. C., Long, B., and Francisco, J. S.: Quantitative Kinetics of the Reaction between CH2OO and H2O2 in the Atmosphere, J. Phys. Chem. A, 126, 6742–6750, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c04408, 2022.

Zheng, J. and Truhlar, D. G.: Quantum Thermochemistry: Multistructural Method with Torsional Anharmonicity Based on a Coupled Torsional Potential, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 9, 1356–1367, https://doi.org/10.1021/ct3010722, 2013.

Zheng, J., Zhang, S., and Truhlar, D. G.: Density Functional Study of Methyl Radical Association Kinetics, J. Phys. Chem. A, 112, 11509–11513, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp806617m, 2008.

Zheng, J., Mielke, S. L., Clarkson, K. L., and Truhlar, D. G.: MSTor: A program for calculating partition functions, free energies, enthalpies, entropies, and heat capacities of complex molecules including torsional anharmonicity, Comput. Phys. Commun., 183, 1803–1812, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2012.03.007, 2012.

Zheng, J., Bao, J. L., Zhang, S., Corchado, J. C., Chuang, Y., Ellingson, B. A., and Truhlar, D. G.: Gaussrate, version 2017-B; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, https://comp.chem.umn.edu/gaussrate/ (last access: 4 November 2025), 2017a.

Zheng, J., Bao, J. L., Meana-Pañeda, R., Zhang, S., Lynch, B. J., Corchado, J. C., Chuang, Y., Fast, P. L., Hu, W. P., Liu, Y. P., Lynch, G. C., Nguyen, K. A., Jackels, C. F., Fernandez Ramos, A., Ellingson, B. A., Melissas, V. S., Villà, J., Rossi, I., Coitiño, E. L., Pu, J., Albu, T. V., Ratkiewicz, A., Steckler, R., Garrett, B. C., Isaacson, A. D., and Truhlar, D. G.: Polyrate-version 2017-C; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, https://comp.chem.umn.edu/polyrate/ (last access: 4 November 2025), 2017b.