the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Analysis of the long-range transport of the volcanic plume from the 2021 Tajogaite/Cumbre Vieja eruption to Europe using TROPOMI and ground-based measurements

Jens Reichardt

Felix Lauermann

Benjamin Weiß

Nicolas Theys

Alberto Redondas

Africa Barreto

Omaira Garcia

Diego Loyola

The eruptions of the Tajogaite volcano on the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja ridge on the island of La Palma between September and December 2021 released large amounts of ash and SO2. Transport and dispersion of the volcanic emissions were monitored by ground-based stations and satellite instruments alike. In particular, the spectrometric fluorescence and Raman lidar for atmospheric moisture sensing (RAMSES) at the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory measured the plume of the strongest Tajogaite eruption of 22–23 September 2021 over northeastern Germany 4 d later. This study provides an analysis of SO2 vertical column density (VCD) and layer height (LH) measurements of the volcanic plume obtained with Sentinel-5 Precursor/TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), which are compared to the observations at several stations across the Canary Islands. Furthermore, a new modeling approach based on TROPOMI SO2 VCD measurements and the Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory Model (HYSPLIT) was developed, which confirmed the link between Tajogaite eruptions and Lindenberg measurements. Modeled mean emission height at the volcanic vent is in excellent agreement with co-located TROPOMI SO2 LH and local lidar ash-height measurements. Finally, a comprehensive discussion of the RAMSES measurements is presented. A new retrieval approach has been developed to estimate the microphysical properties of the volcanic aerosol. For the first time, an optical particle model is utilized that assumes an irregular, non-spheroidal shape of the aerosol particles. According to the analysis, the volcanic aerosol consisted solely of fine-mode inorganic, solid, and irregularly shaped particles – the presence of large aerosol particles or wildfire aerosols could be excluded. The particles likely had an isometric to slightly plate-like shape with an effective half of the particle maximum dimension around 0.1 µm and a refractive index of about 1.51. Moreover, mass column values between 70 and 110 mg m−2, mean mass concentrations of 45–70 µg m−3, and mean mass conversion factors between 0.21 and 0.33 g m−2 at 355 nm were retrieved. Possibly RAMSES observed, at least in part, volcanic secondary sulfate aerosol, which was produced by gas-phase homogeneous reactions during the transport of the air masses from La Palma to Lindenberg.

- Article

(4286 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Volcanic eruptions emit large amounts of particulate matter and trace gases into the atmosphere, which can have a major impact on human health, society, and nature. While the main concern related to volcanic ash plumes is air traffic safety, of the various trace gases emitted such as sulfur species, water vapor, carbon dioxide, and halogens, sulfur dioxide (SO2) has received particular attention due to its subsequent conversion to aerosols (see, e.g., Rix et al., 2012) and its potentially strong effect on global climate (Robock, 2000). SO2 is also the volcanic gas that is most easily detected using ultraviolet (UV) and thermal infrared remote sensing techniques, and it has therefore been used to monitor volcanoes worldwide for many decades (see, e.g., Rix et al., 2009; Carn et al., 2016, 2021; Prata and Lynch, 2019; Coppola et al., 2020).

Global networks of ground-based stations enable the monitoring of air quality, atmospheric trace gases, and atmospheric constituents, including aerosols, clouds, ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), formaldehyde (HCHO), and SO2, with high temporal resolution and accuracy. However, these measurement sites are mainly located in the region of interest, i.e., in or near urban areas or on volcanoes that are potentially hazardous to nearby settlements to allow long-term monitoring at close range. Unfortunately, only 45 % of known active volcanoes are monitored operationally from the ground, as most volcanoes are inaccessible (see, e.g., Sparks et al., 2012; Widiwijayanti et al., 2024). Satellite sensors do not have this limitation; they can make observations on a global scale and are therefore ideal for detecting eruptions and tracking the movement of volcanic clouds, albeit with a limited parameter set and less accuracy than ground stations. Complementary measurements with ground-based and satellite-based instruments would therefore be ideal for a more comprehensive picture.

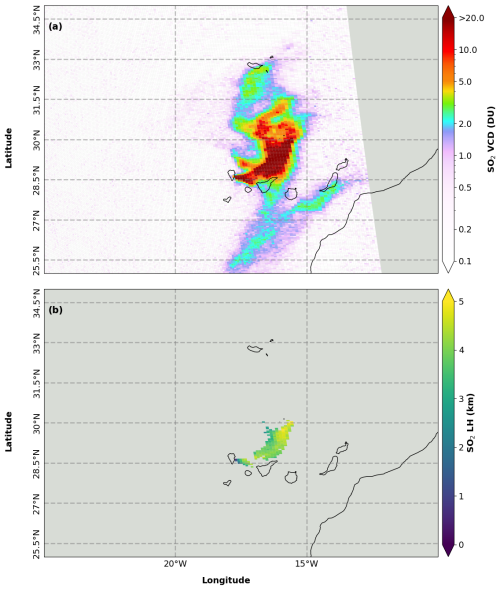

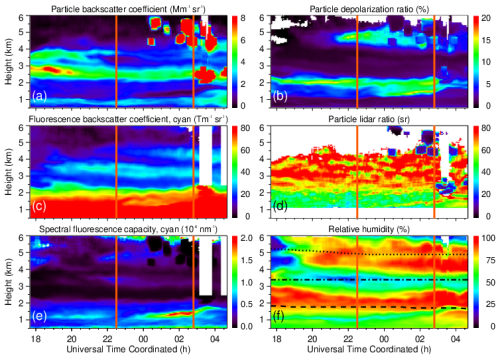

Figure 1Daily TROPOMI SO2 VCD measurements of the volcanic plume from the Tajogaite/Cumbre Vieja eruption during 23–28 September 2021. Only pixels with enhanced SO2 amounts are shown.

Not without earlier warnings (Torres-González et al., 2020) and after a swarm of earthquakes a week before the eruption, several vents opened on 19 September 2021 at 14:10 UTC at the Cumbre Vieja volcanic ridge on La Palma in the Canary Islands, Spain (IGN, 2023). Different eruptive styles were observed, ranging from strombolian to effusive with occasional strong ash-rich explosions, lava effusion, and ash and gas jets (Carracedo et al., 2022; Romero et al., 2022). According to reports from the Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC, 2022), the ash plumes rose up to 5.5 km in height. The eruption, which was subsequently referred to as the “Tajogaite” eruption, ended on 13 December 2021 after 85 d and was finally declared over on 25 December 2021 by the Steering Committee of the Special Plan for Civil Protection and Attention to Emergencies due to Volcanic Risk (PEVOLCA, 2023). The eruption had a strong impact on public health and the economy: about 7000 people had to be evacuated, and the lava flows covered an area of about 12.2 km2, destroying settlements, towns, and banana plantations (Carracedo et al., 2022; PEVOLCA, 2023). According to calculations by the Canary Islands government, the economic damage was estimated at over EUR 800 million.

Volcanic discharge of lava and SO2 was most intense in the first weeks of the eruption. Measurements with the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) aboard the European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-5 Precursor (S5P) satellite showed that daily emission of SO2 was maximum on 23 September 2021 (125 kt d−1), remained at elevated levels until 7 November, and decreased significantly afterwards (Milford et al., 2023). While the ash cloud was confined to the Canary Islands archipelago (Salgueiro et al., 2023), the SO2 plume eventually covered vast areas (Filonchyk et al., 2022) and extended northeast at least to central Europe and south to Cape Verde (Gebauer et al., 2023).

The temporal and spatial development of the Tajogaite emissions was monitored over the entire period of volcanic activity by a considerable number of ground stations and satellites. Scientific interest was so great that additional instrumentation was even brought to La Palma. Several studies have already been published. The investigations address the impact of the eruptions on air quality (Filonchyk et al., 2022; Sicard et al., 2022; Milford et al., 2023) and the microphysical and radiative properties of the volcanic cloud (Bedoya-Velásquez et al., 2022; Córdoba-Jabonero et al., 2023; García et al., 2023; Gebauer et al., 2023; Salgueiro et al., 2023). However, probably in part due to instrument commissioning time, not all studies include the intense September phase of volcanic activity.

In these first days of the eruption, SO2 vertical column density (VCD) as observed by TROPOMI reached values of more than 10 DU in the vicinity of the Canary Islands. The volcanic plume was transported mostly in the northeastern direction towards Europe where it slowly dispersed over Germany and southern Scandinavia and eventually disappeared after 27 September 2021. Figure 1 shows the daily SO2 VCD of the volcanic cloud measured by TROPOMI. A strong eruptive event on 22–23 September injected large amounts of SO2 into the atmosphere (Fig. 1a), which was transported over southern Spain and France (Fig. 1b–c), where the plume split. The sections of it that were emitted first were transported in a northeasterly direction towards Germany, while the younger sections of the plume moved over Italy and Spain (Fig. 1d–f). Previous studies of this event were performed based on data from passive and active instruments operating at ground stations close to Tajogaite on the Canary Islands (Bedoya-Velásquez et al., 2022; García et al., 2023), in southern Spain (Salgueiro et al., 2023), and in southern France (Bedoya-Velásquez et al., 2022). Unfortunately, only basic ceilometers (some with depolarization measurement capability) were available to all research groups, so lidar-based analyses were only possible to a limited extent.

This publication is aimed at furthering research into the early northeastern Tajogaite plume. It passed over Germany on 26–27 September 2021 (see Fig. 1d) where it was measured by the instruments of the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory, most notably by the Raman lidar for atmospheric moisture sensing (RAMSES), the high-performance spectrometric fluorescence and Raman lidar of the German Meteorological Service (Reichardt et al., 2012), under excellent atmospheric conditions. The paper focuses on this unique measurement case. A trajectory and dispersion model is used to establish the Tajogaite eruption on 23 September 2021 as the source of the aerosol which was subsequently observed over Lindenberg after its long-range transport. The RAMSES measurements of the volcanic aerosol are discussed in detail, and its microphysical properties are estimated using a new retrieval approach. For the first time, an optical particle model is utilized that assumes an irregular, non-spheroidal shape of the aerosol particles. To provide some background, SO2 amounts and volcanic plume heights measured by ground-based instruments and TROPOMI are first compared over the entire eruptive period from September to December 2021. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the datasets and instruments used in this paper, Sect. 3 gives an overview of the methods applied, and in Sect. 4 the results are presented and discussed.

2.1 Satellite data from Sentinel-5P/TROPOMI

The ESA Sentinel-5P satellite was launched in October 2017. On board is TROPOMI, a nadir-viewing imaging spectrometer, covering wavelength bands between the UV and the shortwave infrared. It has a swath width of ∼2.600 km on the Earth's surface with a ground pixel resolution of 5.5×3.5 km2 (after mid-August 2019) for the UV bands. Based on TROPOMI Earthshine reflectance measurements, near-real-time (NRT) retrievals are performed to calculate VCDs for SO2, O3, NO2, HCHO, and other atmospheric trace gases. Due to the broad swath, global daily measurements of the Earth's atmosphere can be performed, allowing, e.g., the monitoring and tracking of volcanic emissions worldwide. The overpass time over the Canary Islands is around 14:00 UTC. In this study, the (reprocessed) TROPOMI Level 2 (L2) SO2 product version 03 is used (ESA S5P, 2022).

SO2 VCDs are operationally retrieved from TROPOMI measurements with the differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) method, which yields the SO2 slant column density (SCD), i.e., the density along the light path. A so-called air mass factor is then applied to convert the SCD to VCD. A priori atmospheric SO2 profiles need to be assumed since the actual altitude of the SO2 layer is challenging to estimate directly from UV measurements. SO2 can be injected into the atmosphere at various injection heights depending on the source (anthropogenic or diffusive, weak, or explosive volcanic activity). Therefore, the operational SO2 L2 product contains four different VCDs for the following scenarios: an anthropogenic pollution VCD as well as three volcanic VCDs assuming a volcanic SO2 layer located at 1, 7, or 15 km, respectively, thus representing the full range of possible eruptive scenarios. Eventually, the user has to select the most appropriate VCD for a given volcanic eruption. See Theys et al. (2017) for details about the retrieval algorithm.

Only recently have new methods been developed to directly retrieve the actual SO2 layer height (LH) from TROPOMI data. Hedelt et al. (2019) apply a combined principal component analysis (PCA) and neural network (NN) approach to determine SO2 LH with an accuracy of <2 km for SO2 VCDs >20 DU. This SO2 LH approach has been validated by Koukouli et al. (2022), and its results are now actively assimilated by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) to improve SO2 forecasts, as shown by Inness et al. (2022). In July 2023 it was implemented in the operational TROPOMI SO2 retrieval algorithm. SO2 LHs presented in this paper have been obtained with algorithm version 4.0 (see Hedelt and Koukouli, 2021).

TROPOMI SO2 data contain a detection flag, which flags pixels with enhanced SO2 content above a threshold of 0.35 DU; see Theys et al. (2017). This flag will be used in the following to select pixels of the volcanic plume.

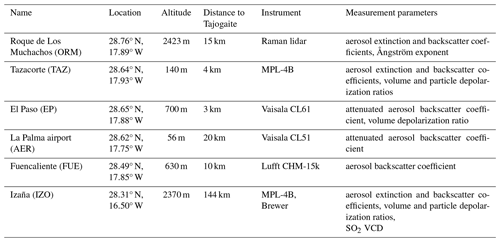

2.2 Ground-based instruments on the Canary Islands

A total of five local lidars were used by AEMET, the State Meteorological Agency of Spain, in collaboration with other ACTRIS (Aerosol, Clouds and Trace Gases Research Infrastructure) members in Spain, to monitor the altitude and wind-driven dispersion of the volcanic plume during the entire Tajogaite eruptive episode. Data from the Raman lidar installed at the Astrophysical Observatory Roque de los Muchachos (ORM), a micropulse lidar (type MPL-4B) deployed at Tazacorte (TAZ), and three ceilometers (Lufft CHM-15k at Fuencaliente, FUE; Vaisala CL51 at La Palma airport, AER; Vaisala CL61 at El Paso, EP) are used in this paper; see Table 1 for details. The retrieval method for AEMET-ACTRIS aerosol LH depends on the type of the instrument; it encompasses a qualitative estimation of the LH, which is based either on the gradient method (Flamant et al., 1997; Sicard et al., 2022) or the continuous wavelet covariance transform (WCT) method (Baars et al., 2008; Bedoya-Velásquez et al., 2022). The AEMET-ACTRIS LH dataset comprises a total of 137 altitudes of the dispersive volcanic plume, and a detailed description of the database can be found in Sicard et al. (2022). The absolute uncertainty of the retrieved aerosol LH shown in this study is about 258 m, which is based on a validation of the AEMET-ACTRIS aerosol LH measurements against reference aerosol LH measurements from the Instituto Geográfico National (IGN, Spain). This validation is the subject of a forthcoming paper by Barreto et al. (2025). Note that IGN aerosol LH retrievals rely on a video surveillance monitoring network performing a robust estimation of the height of the volcanic plume, which can be considered the reference height.

Ground-based measurements of SO2 VCDs were performed with a Brewer spectrophotometer during Tajogaite volcanic activity with high temporal resolution. The instrument was operated at the subtropical high-mountain Izaña Observatory (IZO) on Tenerife; it participates in the European Brewer Network (EUBREWNET, 2024) and is managed by the Izaña Atmospheric Research Center (IARC), which is part of AEMET.

2.3 Ground-based instrument RAMSES in Lindenberg (Germany)

Data from the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory–Richard Aßmann Observatory (MOL-RAO) in Germany are employed to investigate the volcanic plume traveling over Germany. The observatory is part of the German Meteorological Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst – DWD) and is located in the northeastern part of Germany close to Berlin at 52.21° N, 14.12° E. In particular, RAMSES data are used in this study.

RAMSES is a spectrometric fluorescence and water Raman lidar. Commissioned in 2005, RAMSES has been continuously expanded over the years and is now one of the most powerful multiparameter lidar systems in the world (Reichardt et al., 2012). Its unique feature is the operation of three spectrometers, which allows the measurement of water in all three of its phases (Reichardt, 2014; Reichardt et al., 2022) and the measurement of the fluorescence spectrum of atmospheric aerosols for their characterization and interaction with clouds (Reichardt et al., 2023, 2024). A pulsed (30 Hz) frequency-tripled flashlamp-pumped Continuum Powerlite Precision II 9030 laser serves as the radiation source. A Pellin Broca prism is implemented in the transmitter to ensure that only UV light (355 nm, 500 mJ pulse energy) is emitted, which is a prerequisite for spectral fluorescence measurements. The receiver has two telescopes with diameters of 30 and 79 cm for measurements up to 7 km and above 2 km altitude (depending on parameter), respectively, so the plume of the Cumbre Vieja eruption was within the optimal observation range of RAMSES. Therefore, in addition to humidity and the spectral aerosol properties, the elastic scattering properties (extinction and backscatter coefficient, lidar and depolarization ratio) are also available with high quality for the analysis of the volcanic event. Relative statistical uncertainties of the RAMSES measurement parameters shown in the study are below 5 %, except for the lidar ratio, which is noisier (up to 20 %).

This section describes all methods used in this work in detail.

3.1 Comparisons of ground-based and satellite measurements in the vicinity of the volcanic vent

Ground-based Brewer SO2 VCD data from the IZO station on Tenerife are directly compared to TROPOMI SO2 VCD measurements during the satellite overpasses. Only measurements taken near the volcanic vent are considered. Given the fact that the Tajogaite eruptions were not particularly kinetic, low to moderate plume heights of 1 and 7 km are assumed for TROPOMI SO2 VCDs. In addition, SO2 VCDs for retrieved plume heights are used (i.e., for pixels with high SO2 VCD). The median TROPOMI SO2 VCD of all pixels within a radius of 10 km around the IZO station (Table 1) is calculated. It should be noted, however, that such comparison is a challenging task because of the differing measurement principles involved. First, the ground-based instruments perform zenith scans from below, while the satellite is nadir-viewing. Therefore both observations are sensitive to different vertical segments of the volcanic plume. Moreover, due to the different viewing directions, both methods are subject to differential cloud screening. Depending on the location of a possible meteorological cloud with respect to the plume, it may block the observation path or not. Finally, ground-based instruments have a significantly narrower field of view (FOV) compared to satellite instruments, and hence the observed horizontal area of the volcanic plume is not the same.

Furthermore, ground-based lidar ash-height measurements on La Palma are contrasted with TROPOMI SO2 LH retrievals. The challenge here is that air parcels containing SO2 are not necessarily co-located with the ash plume even if discharged at the same time because of the different atmospheric dynamics of particles and gases and the gravitational settling of the heavier ash. The FOV mismatch poses a problem here as well. To minimize the error due to differences in measurement time and FOV, the median TROPOMI SO2 LH over all pixels within a radius of 10 km, or 200 km, around the corresponding lidar is calculated, and the maximum allowable time difference is set to 5 h. Note that TROPOMI SO2 LH and SCD data are known to exhibit a low bias in the presence of volcanic ash. Also, the TROPOMI data might be affected by cloud screening.

3.2 Trajectory analysis method

The Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory Model (HYSPLIT; Stein et al., 2015) is employed to analyze the transport of the volcanic plume and to investigate the plume height, injection height, and arrival height and time as well as the particle travel time. Backward trajectory calculations are performed using the GFS0.25 meteorology, which is a daily dataset from the Global Forecast System (GFS) with 0.25° spatial and 6 h temporal resolution, provided by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP; NCEP/GFS0.25, 2015).

The start locations of the trajectories and the release times depended on the type of analysis intended.

-

To determine the layer height of the pixels with enhanced SO2 content observed by TROPOMI over Europe on 26 September 2021, the backward trajectory calculations were started at the TROPOMI observation times. For trajectory start locations, three TROPOMI orbits (orbit numbers 20 487 to 20 489) were examined. The overpass times were at 10:45 and 12:25 UTC over continental Europe and 14:00 UTC over La Palma. A total of 32 005 pixels were selected as starting locations for the trajectories, which corresponds to every pixel on that day in the region of interest meeting the imposed requirements of SO2 VCD being >0.1 DU and flagged as enhanced SO2. In order to account for the spatial extent of the pixel and related variations in the meteorological field, eight additional starting locations with latitudinal and longitudinal offsets of ±0.01° around the pixel center were created. The trajectories were initialized with starting altitudes between 0.25 and 8.75 km in 50 m increments. The maximum simulation runtime was 7 d.

Trajectories were assigned to the Tajogaite eruption if they passed the volcanic vent within a 100 km radius. Trajectories traveling more than 1 d were further filtered if they passed at least one TROPOMI pixel with enhanced SO2 VCD on each intermediate day between 23 and 26 September within a range of 50 km (see Fig. 1) and within a time interval of ± 2 h around the measurement time of the pixel. Trajectories were discarded if the altitude at the point of their closest approach to the volcano was not within 2 to 6.5 km. This height range is roughly in line with the results of the ground-based measurements described in Sect. 3.3; see also Fig. 3. From the filtered trajectories a per-pixel mean injection height (at the vent), measurement height (at each TROPOMI pixel), and flight time (i.e., the time from emission to TROPOMI pixel) were determined. Note that this approach is comparable to the approach described in Pardini et al. (2017, 2018).

-

To investigate the source of the aerosol layer that passed over RAMSES on 26–27 September 2021, backward trajectory calculations were started from the coordinates of the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory (52.21° N, 14.12° E) in 10 min increments between 09:00 UTC on 26 September 2021 and 09:00 UTC the next day. In contrast to the analysis described above, this approach provides time-resolved results. The HYSPLIT simulation time was set to 120 h so that the simulations ended on 21–22 September 2021.

In addition, eight trajectories with horizontal offsets of ±0.05° around the RAMSES site were launched to account for uncertainties in the meteorological field. The trajectories were started at heights between 1 and 8 km with a vertical increment of 50 m. Thus, 1269 back-trajectories were calculated for each time step, totaling 1 840 005 for this analysis. The trajectories were assigned to Cumbre Vieja if they passed within 100 km. From the filtered trajectories, the mean injection height (at the vent), the measurement height (at Lindenberg), and the flight time (i.e., the time from emission to Lindenberg) were determined.

3.3 Microphysical retrieval

Measurements with RAMSES are generally not well suited for the retrieval of microphysical aerosol properties because the lidar has only one transmitter wavelength, and therefore the spectral dependence of the aerosol elastic–optical properties cannot be quantified. However, as will be shown, measurement cases are an exception where the number of retrieval parameters can plausibly be restricted and the particle depolarization ratio can be used as a second particle-number-concentration-independent measurement parameter in addition to the lidar ratio. Both conditions apply to the RAMSES measurement of the Cumbre Vieja aerosol during the night of 26–27 September 2021.

As will be discussed in Sect. 4.4, the volcanic aerosol that reached the RAMSES site exhibited high lidar ratios (∼75 sr) and small particle depolarization ratios (∼1.8 %). Since the ambient air was dry at ≤60 % and thus droplet formation unlikely, it can be concluded that the aerosol particles were small (fine mode), solid, and of non-spherical shape. Particularly, the existence of a second so-called coarse mode consisting of relatively large ash particles can be excluded. Under the conventional assumption that aerosol modes follow a lognormal distribution, this reduces the number of retrieval parameters to be determined to three (assuming complex refractive index and particle shape). This number corresponds to the number of independent RAMSES measurements of the particle backscatter coefficient (βpar), lidar ratio (Spar), and particle depolarization ratio (δpar) so that a retrieval becomes possible. Obviously, this requires a particle model with which the optical properties of non-spherical particles can be realistically modeled, and in this case the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) scheme is used (Yang et al., 2000). Previous analyses of polar stratospheric cloud observations demonstrated the applicability of FDTD data to aerosol measurements with lidar (Reichardt et al., 2004, 2014). The following is a description of the retrieval method used in Sect. 4.5 to estimate the microphysical properties of the volcanic aerosol from La Palma over northern Germany.

The inversion algorithm considers a single aerosol mode with lognormal size distribution:

where Npar is the total number of aerosol particles, c is half of the particle's maximum dimension, and cm and σ are the median half of the particle maximum dimension and the width of the distribution, respectively. Note that the independent variables do not refer to the radius of the particle but to the semi-diameter of its longest axis. This is because the particle shape is assumed to be irregular and it is difficult to define the radius of such a particle.

The retrieval error E is defined as the sum of the absolute values of the relative errors in retrieved lidar and depolarization ratios:

where superscripts “mea” and “ret” denote measured and retrieved quantities, respectively. and are calculated for a given parameter pair cm and σ using the FDTD database and following the model formulas summarized by Reichardt et al. (2002).

The objective of the inversion run is to minimize E, which can be regarded as a measure of the quality of a fit. First, the refractive index and length-to-width (aspect) ratio of the aerosol particles are preselected. Under these assumptions the distribution parameters cm and σ are estimated by comparing measured and modeled δpar and Spar (which are independent of Npar). For this purpose, the parameter pair is varied within reasonable ranges and the inversion results are ranked according to the magnitude of the resulting retrieval error E. The effective half of the particle maximum dimension (ceff) is computed as auxiliary output, which is defined as the ratio of distribution-averaged particle volume (V) and projection area (A):

To account for the variability and the statistical measurement error of measured Spar and δpar, the inversion run with minimum E is not considered the optimal solution, but rather the average over a freely selectable number of inversion runs with the lowest E values (10 in this study). The particle spectrum of the overall size distribution is therefore not necessarily lognormally distributed but a superposition of lognormal number size distributions. Npar is then calculated from the βpar measurement. Other bulk properties such as the aerosol surface area concentration (spar) and the aerosol volume concentration (vpar) are also obtained. By repeating the computations for different refractive indices and aspect ratios, the best estimates for these quantities can also be obtained by evaluating E. Finally, the plausibility and the height range of applicability of the retrieved microphysical aerosol parameters can be checked by a comparison of retrieved and measured particle extinction coefficient (αpar).

The FDTD database is a compilation of theoretical optical properties. The modeled aerosol particles are assumed to be of irregular shape, i.e., they do not exhibit any symmetry axes, and to be randomly oriented in space. The calculations were performed at three wavelengths (355, 532, and 1064 nm) for five size-independent aspect ratios (0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, and 1.5) and for discrete particle maximum dimensions between 0.01 and 4 µm. The refractive indices cover the expected range of atmospheric particles (real part between 1.32 and 1.75, weakly absorbing), ranging from water ice over those of the Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aerosol modes (Kaufman et al., 2003) to biomass burning aerosol, soil particles, and minerals such as quartz, basalt, and volcanic ash.

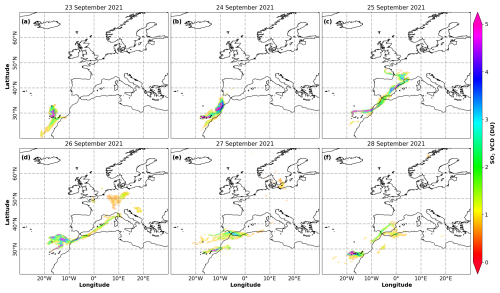

Figure 2Temporal evolution of Tajogaite/Cumbre Vieja SO2 VCD over the entire period of volcanic activity as measured with the ground-based IZO Brewer spectrophotometer located on Tenerife (black dots) and TROPOMI. Median TROPOMI SO2 VCDs are presented, calculated within a radius of 10 km around the IZO station for standardized plume heights of 1 km (red dots) and 7 km (blue dots), as well as for the retrieved SO2 LH (green dots). Dashed vertical lines indicate the eruptive event that is analyzed in this paper in detail. Note that the Brewer instrument is located on Tenerife, and hence a time offset compared to measurements on La Palma applies.

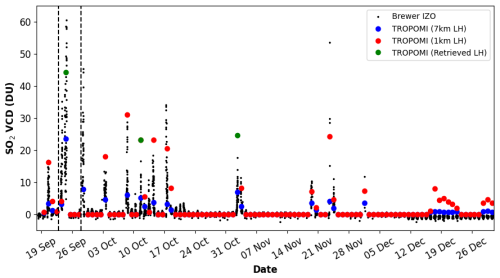

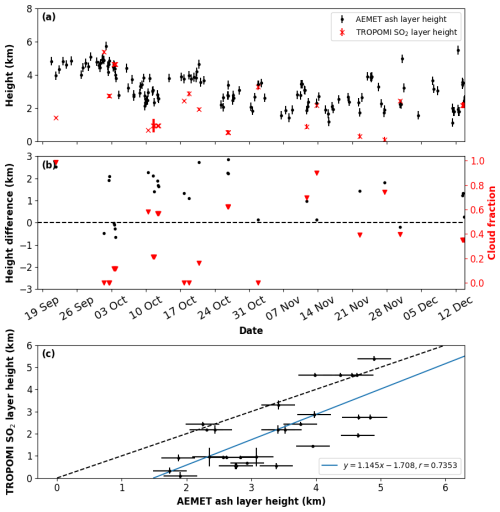

Figure 3Temporal evolution of the Tajogaite plume height over La Palma between 19 September and 13 December 2021. (a) Plume height derived from ground-based lidar measurements at local AEMET stations (black dots) and median TROPOMI SO2 layer height retrieved within a distance of 10 km (red crosses) from the corresponding station. (b) Difference between lidar plume height and median TROPOMI SO2 layer height within a 10 km radius (black dots) and the TROPOMI cloud fraction (red triangles). (c) Relation between lidar-derived plume height and median TROPOMI SO2 layer height within a 10 km radius. The result of the linear fit is shown (blue line). For reference the identity function is marked as well (dashed black line).

4.1 Comparison of TROPOMI and ground-based data in the vicinity of Tajogaite

Figure 2 compares SO2 VCDs measured with TROPOMI and the IZO Brewer spectrophotometer on the island of Tenerife over the entire eruptive phase of the Tajogaite volcano. The agreement is satisfactory. Although TROPOMI only performs daily measurements over the Canary Islands, it detects most of the eruptive events with high SO2 amounts observed by the Brewer instrument. Around the major eruption in late September 2021, the matching can be significantly improved if an intermediate layer height of about 4 to 5 km is assumed, which agrees well with the actual plume height evidenced by the ground-based lidar measurements and TROPOMI SO2 LH (Fig. 3a). On 12 October 2021, the TROPOMI SO2 LH retrieval underestimates layer height, possibly due to the presence of volcanic ash, and hence the SO2 VCD for the retrieved LH is overestimated and close to the value derived for the standard plume height of 1 km. Note that this underestimation of the SO2 LH in the presence of volcanic ash is a well-known problem due to the light-shielding effect of ash particles in the atmosphere. Surprisingly, on 3 November 2021 TROPOMI SO2 LH and lidar-derived plume height agree remarkably well, but the associated TROPOMI SO2 VCD is larger than the Brewer measurement. It may be speculated that spatial inhomogeneity in the volcanic plume or some undetected clouds caused the discrepancy.

Figure 3 discusses the local long-term observations of the Tajogaite plume height. As detailed in Sect. 2.2, lidar profiles from several instruments across the island of La Palma were evaluated to determine the top height of the ash layer. The layer was highest (around 4–5 km) in the first days after the eruption and subsided slightly after 5 October 2021 (Fig. 3a). The final part of the eruption then again showed an explosive episode with high ash heights. Median TROPOMI SO2 LH (Sect. 2.1) shows good agreement with the lidar results, even though the measurement time difference was up to 5 h and the mean cloud fraction over the scene was significant at times (Fig. 3b, red triangles). The differences are in the range of only 1–3 km, with a difference of less than 1 km for cloud fractions below 0.5, which is quite astonishing given the dissimilar methodology. Note that the co-presence of meteorological clouds can have an impact on the SO2 LH retrieval: if a meteorological cloud is above or mixed with the SO2 cloud it could shield the SO2 cloud. If the meteorological cloud is below the SO2 cloud, the higher (surface) albedo could lead to an increased sensitivity. The most reliable SO2 LH value can therefore be retrieved when there are no meteorological clouds in the pixel area. This is clearly visible for pixels with low cloud fractions in Fig. 3c, showing low differences between ash and SO2 layer heights. Statistically, TROPOMI SO2 LH underestimates the height of the volcanic plume if compared to lidar ash height (Fig. 3c). Although a correlation between the two datasets is evident, it is not pronounced (correlation coefficient r=0.74), which is hardly surprising given the methodological difficulties discussed in detail.

4.2 Analysis of the northeastern-Europe-bound volcanic plume

According to Milford et al. (2023), Tajogaite ejected a record daily amount of 125 kt SO2 during its most intense eruption, which culminated on 23 September 2021. The volcanic cloud split into a part that moved south and a part that moved northeast towards Europe (Fig. 1), the latter of which passed over Lindenberg several days later.

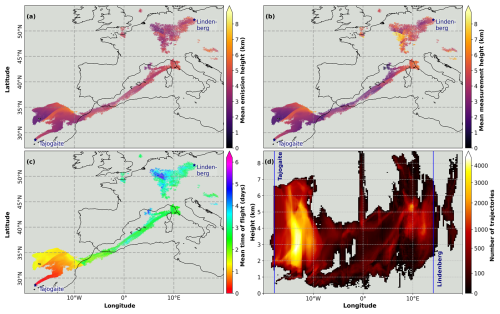

Figure 4Analysis of the SO2 plume over Europe on 26 September 2021 based on HYSPLIT back-trajectory calculations. For each TROPOMI pixel with enhanced SO2 VCD, (a) mean injection height at volcanic vent, (b) mean layer height at measurement location, and (c) mean plume age are visualized; (d) number of trajectories reaching the vent as a function of measurement height and longitude.

Key features of the Tajogaite plume are explored for 26 September 2021, the starting day of the RAMSES measurements. Since the retrieval of the volcanic plume height directly from the TROPOMI observations is only possible for significant levels of SO2 (Sect. 2.1), an alternative method had to be devised to track the height of the increasingly diluted SO2 cloud over Europe. This indirect method is based on extensive back-trajectory computations, as explained in Sect. 3.2. The criteria described in that section were fulfilled by 6 776 014 trajectories, which corresponds to 13.84 % of the total number of started trajectories. Figure 4a–c present the mean emission height, mean measurement height, and mean plume age for the TROPOMI SO2 VCD scene of 26 September 2021 (see Fig. 1). Every TROPOMI pixel with elevated SO2 level was used as a start location for a backward trajectory. The longitudinally integrated number of trajectories reaching the volcanic vent for measurement heights between ground and 8.75 km is also depicted (Fig. 4d). Note that the number of trajectories, however, does not directly indicate the SO2 load of the trajectory. In view of the ground-based ash layer altitude measurements near the Tajogaite volcano (Fig. 3), trajectories were discarded if the height at their location closest to the vent was not within 2 to 6.5 km. This is based on the assumption that ash and SO2 layers were similar.

As expected, the volcanic SO2 plume close to La Palma is relatively young, with ages of around 1 d (Fig. 4c). The age of the extended plume over the Mediterranean Sea is around 2–3 d and over Germany about 3–4 d. Thus, it can be concluded that SO2 observed on 26–27 September over Germany was released from Tajogaite around 23 September 2021.

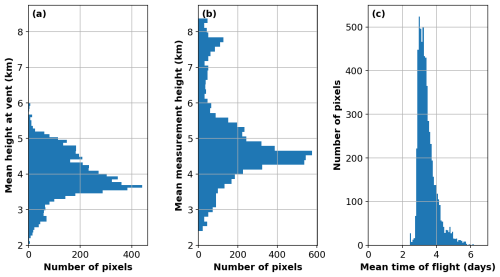

Furthermore, the plume over Germany is located around heights of 3–6 km at the time of the TROPOMI measurement, with a small fraction between heights of 7 and 8 km over southwestern Germany (Fig. 4b, d), and was emitted at an injection height of about 2.5–5 km (Fig. 4a). This is also visualized in Fig. 5, which shows histograms of the mean injection height at the volcanic vent (a), mean measurement height over Germany (b), and mean time of flight of the trajectories launched from each TROPOMI pixel over Germany (45–55° N, 6–15° E) that successfully arrive at the volcanic vent. Importantly, this emission height range is in excellent agreement with the direct TROPOMI SO2 LH measurements on 23 September (Fig. 6b), underlining the usefulness of the backward-trajectory-based analysis approach.

Figure 5Histograms of mean trajectory properties launched from each TROPOMI pixel location over Germany (45–55° N, 6–15° E) on 26 September 2021 and arriving at the Cumbre Vieja vent based on HYSPLIT back-trajectory calculations. The (a) injection height at the volcanic vent, (b) layer height over Germany, and (c) time of flight are visualized.

4.3 Trajectory analysis applied to Lindenberg observations

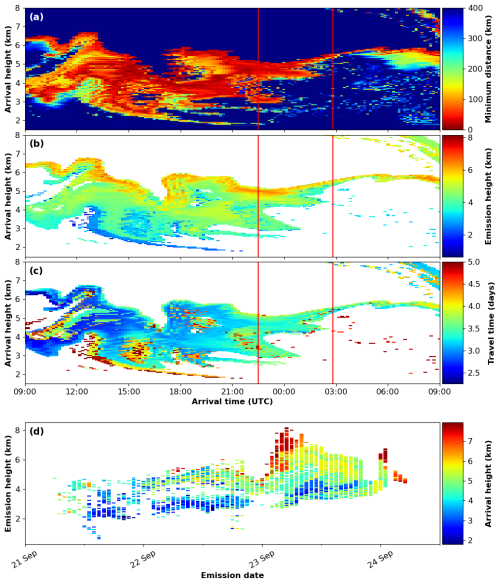

To put the measurements of the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory, Germany, into context with the Tajogaite eruptions, extensive trajectory calculations have been performed as described in Sect. 3.2. Figure 7 presents the results of this time-dependent trajectory analysis. Figure 7a–c show the arrival height as a function of arrival time at Lindenberg: in Fig. 7a the minimum approach distance of all trajectories to the volcano is color-coded. In Fig. 7b and c, however, only trajectories are considered which passed it within 100 km; in the former the emission height is color-coded, and in the latter is the trajectory travel time from La Palma to Lindenberg. Finally, Fig. 7d visualizes the emission heights and dates for the arrival heights of the air parcels over RAMSES.

There is a noticeable time dependence of the arrival heights in Lindenberg: until 21:00 UTC trajectories from near the volcanic vent are registered over a broad altitude range between 2 and 6 km. Then several distinct layers emerge at 2.5, around 3.5, and around 4.5 km. After 00:00 UTC only one layer persists between 4.5 and 5.5 km, slowly ascending with time.

The emission height at the volcanic vent is well correlated with the arrival height at Lindenberg (Fig. 7b). Generally, emission height increases with measurement height, although the temporal behavior is dynamical. For instance, between 13:00 and 21:00 UTC emission height fluctuates considerably at 3–4 km. Interestingly, plume age is connected to emission height. While between 15:00 and 16:00 UTC the travel time of the air parcels with low emission heights can reach up to 5 d, which means that they passed by Tajogaite volcano on 21 September 2021, the earlier and later air parcels with elevated injection heights exhibit a significantly shorter transport time (Fig. 7c) due to different wind speeds and directions in different atmospheric layers.

Finally, from Fig. 7d one can tell that air masses observed over Lindenberg between 3 and 4 km carried volcanic emissions that were injected at heights between 2 and 5 km over 2 d starting at 09:00 UTC on 21 September 2021. For measurement altitudes above, emission height is higher and emission time confined to after 09:00 UTC on 23 September 2021. The agreement between the HYSPLIT simulations and the RAMSES lidar measurements (Fig. 8) is quite satisfying, and the fluorescent layers at 3.2 and 4.5 km are especially well reproduced by the HYSPLIT simulations between 22:00 and 00:00 UTC.

Figure 7Analysis of air parcel history over Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory for the time period between 09:00 UTC on 26 September 2021 and 09:00 UTC on 27 September 2021 based on HYSPLIT back-trajectory calculations. Trajectory start heights ranged from 1 to 8 km. (a) Minimum approach distance to Tajogaite, (b) height at minimum distance to Tajogaite for approach distances <100 km, and (c) air parcel travel time between Tajogaite and Lindenberg. Vertical red lines indicate the RAMSES lidar measurement times, which are analyzed in Sect. 4.5. From the latter two datasets, (d) the emission heights and dates for the arrival heights of the air parcels over Lindenberg can be derived.

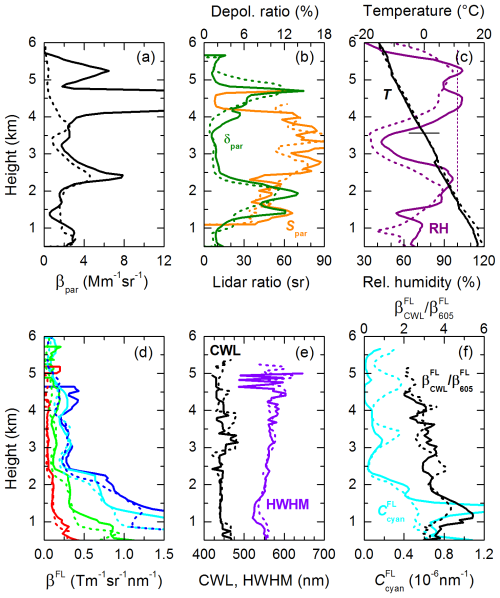

Figure 8Temporal evolution of (a) particle backscatter coefficient, (b) particle depolarization ratio, (c) fluorescence backscatter coefficient (cyan false color: spectrum integrated from 455 to 535 nm), (d) particle lidar ratio (not corrected for multiple scattering), (e) spectral fluorescence capacity (mean value, 455–535 nm), and (f) relative humidity (with respect to water; 10, 0, and −10 °C isotherms indicated by black lines) as measured with RAMSES on the night of 26–27 September 2021 between 17:40 and 04:40 UTC. Measurements at 22:30 and 02:48 UTC are analyzed in detail in Fig. 9 (times marked by vertical orange lines). For each profile, 1200 s of lidar data are integrated, and the calculation step width is 120 s. The resolution of the raw data is 60 m, and signal profiles are smoothed with a sliding average length increasing with height. White areas indicate where data were rejected by the automated quality control process.

4.4 Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory: volcanic aerosol optical properties

In September 2021, RAMSES measured continuously first, but starting on 24 September operation was restricted to night mode due to generally unfavorable weather conditions. Therefore, the measurement of the Tajogaite aerosol on 26–27 September only started at 17:30 UTC. Incidentally, measurements during cloud gaps in the nights before and after provide no indication of the presence of volcanic aerosol, which is in agreement with the TROPOMI SO2 measurements (Fig. 1). The RAMSES dataset extended by ceilometer measurements on-site in the early afternoon of 26 September and morning of 27 September provides the end times of the extensive back-trajectory analyses in Sect. 4.3.

Figure 8 depicts the temporal evolution of the aerosol event. In addition to the more common measurement quantities such as particle backscatter coefficient, lidar and particle depolarization ratio, and relative humidity, those that characterize the fluorescence of the Tajogaite aerosol are also shown. These are the fluorescence backscatter coefficient as the sum of the spectral backscatter coefficients (βFL) from 455 to 535 nm, which is therefore assigned the false color cyan (Fig. 8c), and the spectral fluorescence capacity in the same wavelength range (, Fig. 8e), which is defined as the quotient of mean βFL and the (elastic) particle backscatter coefficient (Reichardt, 2014; Reichardt et al., 2023). The latter is a measure of how strongly the observed aerosol fluoresces and, together with the knowledge of the shape of the fluorescence spectrum, allows one to deduce the aerosol type. On this night, clouds only appear towards the end of the observation period (discernible by the red and deep blue patches in the βpar and Spar displays, respectively) so that the data quality is excellent.

The aerosol field showed relatively little dynamism during the entire measurement night. Three layers can be identified, which differ significantly in their aerosol properties. The layer below approximately 2.4 km exhibits relatively low βpar and Spar, at times significant δpar, and comparatively high fluorescence backscatter coefficients and spectral fluorescence capacity.

Clearly delineated by its properties, the layer that will be the main focus of this study is located above in the height range of approximately 2.5 to 4 km. This filament can be traced back with a high degree of certainty to the eruptive phase of the Tajogaite volcano on 23 September 2021 (see Sect. 4.3) and at the same time exhibits homogeneous elastic and inelastic optical properties that can be measured with low statistical errors. In contrast to the bottom layer, it is characterized by extremely low δpar and , a low fluorescence backscatter coefficient, elevated βpar, and high Spar. The dynamic evolution of βpar is not reflected in Spar and δpar and is therefore caused by variations in particle concentration and not in particle type. For the discussion that follows it is also important to note that the relative humidity is generally low.

Above an altitude of 4 km, a third aerosol layer appears around 21:00 UTC (Fig. 8b, c, and e), which probably also consists of volcanic aerosol but is so optically thin that it is hardly visible in βpar, and Spar cannot be determined. A prominent feature is its elevated depolarization ratio. Relative humidity is so high that clouds can form sporadically.

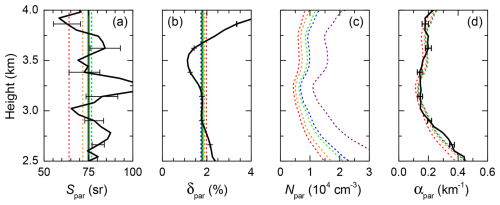

Figure 9RAMSES measurements on the night of 26–27 September 2021 at 22:30 UTC (dashed curves) and 02:48 UTC (solid curves). Profiles of (a) particle backscatter coefficient (βpar), (b) particle lidar ratio (Spar) and particle depolarization ratio (δpar), (c) relative humidity (RH, with respect to water and ice above and below 0 °C, respectively) and temperature (T), (d) mean spectral fluorescence backscatter coefficient (βFL) at red, green, cyan, and blue wavelengths, (e) wavelength of the spectral maximum (CWL) and of the half-maximum value on the long-wavelength shoulder of the fluorescence spectrum (HWHM), and (f) spectral fluorescence capacity at cyan wavelengths () and the ratio of spectral fluorescence backscatter coefficients at the maximum of the fluorescence spectrum and at 605 nm (). Error bars have been omitted for conciseness.

For a quantitative discussion, the profile measurements at 22:30 and 02:48 UTC are depicted in Fig. 9. It can be clearly seen that the aerosol optical properties, both elastic and inelastic, remained essentially unchanged over the measurement period, and the vertical stratification was also maintained. Only an increase in relative humidity can be observed, which ultimately led to a swelling of the aerosols and to cloud formation, particularly at heights above 4 km, as manifested by the βpar profile (Fig. 9a).

The aerosol layer between 2.5 and 4 km remained dry at its center but got moister towards its bounds (up to 90 % relative humidity). An important observation is that Spar and δpar (Fig. 9b) did not respond to these changes in relative humidity (Fig. 9c), which indicates that the particles were either insoluble in water or had a high deliquescence relative humidity (e.g., ammonium sulfate exhibits a deliquescence relative humidity of 81.9 % at 4 °C; Brooks et al., 2002). Furthermore, the minimum relative humidity of around 34 % observed at 22:30 UTC is below the efflorescence relative humidity of many atmospheric compounds such as sulfates and nitrates (Peng et al., 2022), so if these aerosol particles had been droplets previously, they would have solidified due to water loss by the time of measurement. It can therefore be assumed that the volcanic aerosol particles were not of spherical shape. Instead, the low δpar values near 2 % and the high Spar values around 75 sr (Fig. 9b) must be attributed to scattering by solid particles. These particles are definitely not volcanic ash because lidar measurements during several volcanic eruptions provided ash δpar and Spar values of >30 % and <65 sr, respectively, in the troposphere (Ansmann et al., 2010; Groß et al., 2012; Pisani et al., 2012). Saharan dust can also be excluded for the same reason (Groß et al., 2012).

A further indication of the aerosol type of the central layer is provided by the fluorescence properties, which are illustrated in Fig. 9d–f. It should be noted at this point that the fluorescence spectrum cannot originate from SO2 itself but must come from the aerosol particles. An estimation shows that even under favorable experimental and atmospheric assumptions, the fluorescence backscatter signal of SO2 could explain at most 0.1 % of the measured count rates in the cyan spectral range because the absorption cross section of SO2 at 355 nm ( cm2 molecule−1, Manatt and Lane, 1993), the SO2 column value measured above Lindenberg (4 DU), and the fluorescence backscatter coefficients between 455 and 535 nm (<35 , Fig. 8c) are simply too small. The wavelengths of the maximum of the fluorescence spectrum and of the half-maximum value on its long-wavelength shoulder (Fig. 9e) as well as the ratio of the spectral backscatter coefficients at the maximum of the fluorescence spectrum and at 605 nm (Fig. 9f) characterize the shape of the fluorescence spectrum. Values of 440 nm, 560 nm, and around 3, respectively, and values nm−1 are similar to those measured in the boundary layer under undisturbed conditions (no domestic fires, no forest fires) and differ significantly from the spectra of biomass burning aerosol (BBA) frequently measured with RAMSES in the troposphere and lower stratosphere (Reichardt et al., 2023, 2024). For example, the maximum of the spectrum for BBA is well above 500 nm and is often more than 10 times higher.

In summary, spectral fluorescence properties and capacity indicate the presence of inorganic aerosols, and particle elastic optical properties suggest that the particles were small and of irregular shape. If any volcanic ash had been injected into the air masses that were monitored in the central layer, by the time the plume reached Lindenberg the particles would have disappeared. Under these assumptions a microphysical interpretation of the RAMSES measurements is presented in Sect. 4.5.

Interestingly, the adjacent aerosol layers show significantly higher δpar and lower Spar. Between 1.4 and 2.4 km, maximum δpar values at both measurement times are >10 %, and Spar fluctuates around 50 sr. The spectral fluorescence properties are little changed, and only increases slightly. Above 4 km some of the measurement quantities are not available because the aerosol layer is either optically too thin or masked by the cloud, but at 22:30 UTC comparable δpar values can be measured. These observations would be consistent with the assumption that there could have been admixtures of mineral aerosol such as volcanic ash or Saharan dust. According to the back-trajectory analyses in Sect. 4.3, this is entirely plausible.

4.5 Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory: volcanic aerosol microphysical properties

The analysis of the particle optical properties in Sect. 4.4 led to the conclusion that the volcanic aerosol layer between 2.5 and 4 km consisted of inorganic, small, solid, and irregularly shaped particles. In the following, an attempt is made to determine some of the microphysical properties of these – in the terminology of Córdoba-Jabonero et al. (2023) – non-ash particles.

The retrieval scheme described in Sect. 3.3 was employed, with the retrieval runs configured as follows. The particle spectrum is considered monomodal. To determine the median half of the particle maximum dimension and the width of the normalized size distribution (cm and σ), Spar and δpar layer mean values of 75 sr and 1.8 %, respectively, are assumed as and (see Fig. 10a, b). These values are taken from the RAMSES measurement at 02:48 UTC but can be considered representative for the earlier measurement as well (see Fig. 9). Aspect ratio (shape) and refractive index are prescribed for each run, where cm is varied between 0.05 and 0.20 µm (step size of 0.01 µm) and ln σ is varied between 0.10 and 0.45 (step size of 0.01). The individual results are ordered according to E. However, in order to better account for measurement errors and natural variability, the pair of values cm and σ with minimum retrieval error is not considered the optimal solution, but rather the mean value from the 10 best retrieval runs. The resulting normalized particle size distribution is therefore a superposition of lognormal distributions and thus no longer a normal distribution itself. The aspect ratio is varied over five discrete values between 0.50 (plate-like particles) and 1.5 (elongated particles).

Figure 10Retrieval of the microphysical properties of the volcanic aerosol layer measured with RAMSES between 2.5 and 4 km on 27 September 2021 at 02:48 UTC. Profiles of (a) measured (black curve, with statistical error bars), measured mean (vertical dark green line), and retrieved (dashed colored vertical lines) particle lidar ratios (Spar); (b) measured, measured mean, and retrieved particle depolarization ratios (δpar); (c) retrieved particle number concentrations (Npar); and (d) measured and retrieved particle extinction coefficients (αpar). Measured mean Spar and δpar were used as input to the inversion algorithm to estimate the defining parameters of the normalized size distribution assumed to be of monomodal lognormal shape. Retrieval results presented are the mean values over the 10 inversion runs with the lowest retrieval error; the values obtained are for particle complex refractive indexes of 1.40-i0.002 (violet), 1.45-i0.0035 (blue), 1.51-i0.000 (green), 1.55-i0.005 (orange), and 1.65-i0.005 (red) and an aspect ratio of 1. Measured particle backscatter coefficients were then used to retrieve the associated Npar profiles. From the retrieval results αpar can be calculated; estimated and measured αpar profiles are compared in panel (d). Retrieved size distributions are shown in Fig. 12.

The refractive index is also varied over five values from 1.4 to 1.65 (real part). This is intended to obtain an indication of the aerosol type. For example, it is conceivable, albeit unlikely, that the aerosol mode consisted of ultrafine ash particles. Both real and imaginary parts of the refractive index of volcanic ash increase when the silicon dioxide (SiO2) mass fraction decreases. Basalt (49 % SiO2), for instance, exhibits a refractive index of about 1.625-i0.0017 at 355 nm (Vogel et al., 2017). Because Cumbre Vieja lava has a low SiO2 content (Romero et al., 2022; Castro and Feisel, 2022), it is therefore worthwhile to carry out retrieval runs with a refractive index in the range of 1.55 to 1.65 (real part). Moreover, the real refractive index of soil particles shows values of 1.42 to 1.73 in the visible and near-infrared light spectrum, with most data between 1.5 and 1.7 (Ishida et al., 1991). Finally, Ebert et al. (2002) published secondary electron images and summarized refractive indexes of airborne particles. According to these data, one would expect a rather isometric shape (aspect ratio around 1) and a refractive index between 1.5 and 1.53 (note that in the following this paper only refers to the real part of the refractive index).

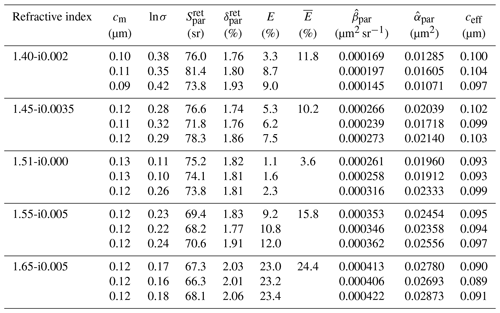

Table 2Summary of retrieval results obtained for the volcanic aerosol layer between 2.5 and 4 km measured on 27 September 2021 at 02:48 UTC.*

* The measured lidar and depolarization ratios representative of the layer to be emulated are 75 sr and 1.8 %, respectively. The particles are assumed to have an irregular shape with an aspect ratio of 1 and a lognormal size distribution. For each refractive index, the results of the three best retrieval runs are presented; see text for details. cm, σ – retrieved size distribution parameters: median half of the particle maximum dimension and standard deviation; , – retrieved lidar and depolarization ratio; E – individual retrieval error (sum of the absolute values of the relative errors in retrieved lidar and depolarization ratios); – retrieval error averaged over the 10 best retrieval runs; , – retrieved backscatter and extinction coefficient of a single particle, distribution-averaged; ceff – effective half of the particle maximum dimension (ratio of distribution-averaged particle volume and projection area).

Table 2 summarizes some retrieval results obtained for isometric aerosol particles. As examples the output of the three individual retrieval runs with minimum E are listed for each refractive index, and the average error of the 10 best runs is also given. Optimum results are obtained for particles with a refractive index of 1.51. Retrieval errors generally increase at both smaller and larger refractive indexes, and so do the differences between measured and retrieved aerosol optical properties. Distribution-averaged particle backscatter and extinction coefficients (, ) exhibit a significant trend with refractive index, while the effective half of the particle maximum dimension (ceff) is relatively invariant (<20 % variation).

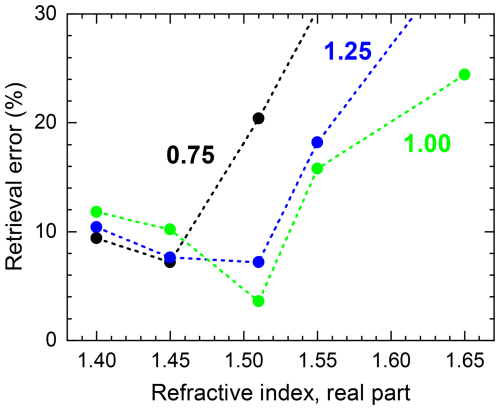

Figure 11Dependence of the retrieval error of the optimum solution () on refractive index and aspect ratios of 0.75, 1.00, and 1.25.

Figure 11 visualizes the dependence of the retrieval error of the optimum solution () on refractive index and aspect ratio. With increasing asphericity, the minimum of shifts to smaller refractive indexes. For all aspect ratios considered, is much larger for refractive indexes >1.51, so it can be ruled out with some certainty that the aerosol layer over Lindenberg consisted of fine volcanic ash or optically similar material.

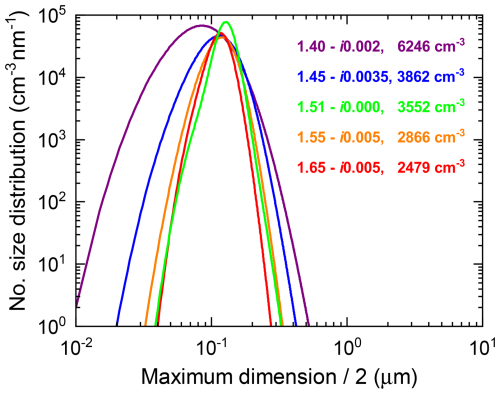

As detailed in Sect. 3.3, the retrieval results can be used to calculate the particle number concentration (Npar) from the particle backscatter coefficient (βpar) and then retrieve the modeled particle extinction coefficient (αpar). Figure 10c depicts the Npar results obtained for the optimum solutions (averages over the 10 best retrieval runs) for all refractive indexes considered (aspect ratio of 1), and Fig. 10d compares retrieved and measured αpar profiles. The underlying particle size distributions are shown in Fig. 12. Npar profiles are relatively close to one another, with the exception of the profile with the lowest refractive index, where Npar is significantly larger, which can be explained by the increased contributions of small particles to the size distribution (Fig. 12). This discrepancy disappears when the retrieved extinction coefficient is considered because a higher number is compensated for by smaller projection areas of the particles ( decreases with refractive index, Table 2). Accordingly, all modeled extinction profiles are within or close to the statistical error limits of the RAMSES measurement. The two αpar profiles obtained with the largest refractive indexes show the worst agreement, which again suggests that the particles actually had a refractive index <1.55. The comparison between measured and modeled extinction coefficients thus provides an opportunity to estimate the height range of the measurement in which the retrieval can be considered representative. It is therefore not surprising that the αpar profiles show large discrepancies above 4 km in the layer with cloud formation and below 2.5 km in the aerosol layer with decreased Spar and increased δpar (not shown).

Figure 12Size distributions retrieved for the volcanic aerosol layer between 2.5 and 4 km measured on 27 September 2021 at 02:48 UTC. Curves display averages over the 10 best retrieval runs for each refractive index. Because the particle shape is irregular, it is difficult to define the radius of such a particle. Therefore, the results are presented as a function of half of the particle maximum dimension. The assumed refractive index and retrieved particle number concentration (βpar=1 Mm−1 sr−1) of the aerosol modes are indicated. The aspect ratio is 1.

It should be noted that even a modeling attempt specifically tailored to the lower layer did not lead to satisfactory results. The solution space was very limited and the retrieval errors were high. The characterizing optical properties (Spar=50 sr, δpar=11 %; Fig. 9) cannot be reproduced under the assumption of a monomodal particle size distribution. This finding supports the assumption made in Sect. 4.4 that larger particles could also have been present in this layer, forming a coarse mode. A bimodal approach would therefore be required to retrieve its microphysical properties.

For the non-ash particles of the volcanic aerosol filament between 2.5 and 4 km a volume concentration (vpar) of (10.6±0.5) µm3 cm−3 per βpar=1 can be found for the refractive index of 1.51. With a refractive index of 1.45, vpar is 9 % larger. To calculate the aerosol mass concentration, the mass density of the particles must be assumed. Córdoba-Jabonero et al. (2023) use a mass density of 1.5 g cm−3 for non-ash particles that constitute the fine aerosol mode, and Ebert et al. (2002) determine values between 1.6 and 2.3 g cm−3 for different types of sulfates. Applying this range of densities and considering the βpar profile between 2.5 and 4 km, mass column values M between 70 and 110 mg m−2 can be obtained. Mean mass concentration amounts to 45–70 µg m−3. With an optical depth (OD) of 0.33, the mean mass conversion factor OD ranges between 0.21 and 0.33 g m−2 at 355 nm. Córdoba-Jabonero et al. (2023) retrieved a similar f value for non-ash particles (∼0.31 g m−2), which is quite remarkable because completely different retrieval schemes were used in the two studies, and the lidar wavelengths were different (355 vs. 532 nm).

Finally, the question arises as to whether the type of volcanic aerosol observed over Lindenberg can be inferred based on the measurements and the retrieval results. As explained in Sect. 4.4, organic aerosols and aerosols with large mineral particles can be excluded based on the optical properties. Furthermore, despite all its limitations, the results of the retrieval suggest that the non-ash particles had a solid, isometric to slightly plate-like irregular shape with an effective half of the particle maximum dimension around 0.1 µm and a refractive index of about 1.51 (1.45 with lower probability). Moreover, the lack of sensitivity of the particle properties to wide variations in relative humidity implies that they were poorly soluble in water.

Emissions from volcanoes generally encompass gases like SO2 and particles. Volcanic ash, if ejected at all, was not observed by RAMSES during its 26–27 September 2021 operation. Other particles include primary sulfates, a term which is used to differentiate between sulfates directly emitted and those produced in the atmosphere (secondary sulfates; Martin et al., 2014). According to Allen et al. (2002), primary sulfates are present mainly in the form of sulfuric acid droplets and are subject to evaporation in dry air. SO2 can undergo different reaction paths in the atmosphere that may lead to the formation of particulate (secondary) sulfate (Mather et al., 2003). In gas-phase homogeneous reactions the concentration of the hydroxyl radical is paramount. The SO2 conversion rates are generally slow and depend on daylight, temperature, and humidity (around 5 % h−1–10 % h−1 of SO2 reacted in summer and 0.3 % h−1–1 % h−1 of SO2 reacted in winter), Pattantyus et al. (2018) report even smaller conversion rates (daytime: 0.8 % h−1–5 % h−1; nighttime: 0.01 % h−1–0.07 % h−1). Aqueous-phase reactions are much faster (20 % h−1–100 % h−1 of SO2 reacted) but require high humidity and water droplets (Mather et al., 2003).

In the case of the RAMSES observations, aqueous-phase reactions could not have played a dominant role. If cloud processing had occurred, all SO2 would have been consumed by the time the northeastern plume reached Lindenberg. The altitude range between 2.5 and 4 km, in particular, was too dry. So possibly RAMSES observed in this layer secondary sulfate aerosol which was produced by gas-phase homogeneous reactions. Associated SO2 conversion rates may have been so slow that even after several days of atmospheric transport, a significant amount of SO2 could still be observed. The performed sensitivity test is supportive of this hypothesis because the absolute minimum in is found for isometric particles with a refractive index of 1.51, which is in accordance with the study of Ebert et al. (2002) on atmospheric sulfate particles, and the retrieved mass conversion factor is comparable to the one published by Córdoba-Jabonero et al. (2023) for non-ash particles. But still, it remains unknown how much of the aerosol measured with RAMSES was actually volcanic secondary sulfate since other solid particles with a similar refractive index may have contributed as well.

Incidentally, Gebauer et al. (2023) arrive at a similar conclusion regarding their measurements of planetary boundary layer aerosols when the southbound plume of Cumbre Vieja crossed over Mindelo, Cape Verde, on the morning of 24 September 2021. According to Gebauer et al. (2023), sulfate aerosol was observed. A distinctive difference from the RAMSES measurements is, however, that aerosol δpar was much lower (layer mean value of 0.4±0.3 % at 355 nm), so the phase was likely different. The boundary layer particles were probably droplets rather than dry solid sulfates, which is reasonable because they were exposed to high humidity over the Atlantic Ocean and thus aqueous-phase reactions dominated. The significant aerosol extinction coefficient of 0.8 km−1 (4 times higher than measured in the sulfate layer over Lindenberg) may be indicative of water uptake by the particles.

The Tajogaite volcano on the western flank of the Cumbre Vieja ridge on La Palma, Canary Islands, was volcanologically active between 19 September and 25 December 2021. The focus of this publication has been its first and strongest eruptive event, which occurred on 22–23 September 2021 and resulted in SO2 emissions of more than 10 DU. The northeastern leg of the associated plume headed towards central Europe where it was observed with the high-performance spectrometric fluorescence and Raman lidar RAMSES when it passed over the Lindenberg Meteorological Observatory of the German Meteorological Service near Berlin, Germany, on the night of 26–27 September 2021. For the first time, satellite and ground-based measurements have been combined to characterize this plume near its source and after the long-range transport to Lindenberg.

To provide some background, measurements of SO2 amounts and volcanic plume heights by local ground-based instruments and by TROPOMI on board the Sentinel-5P satellite have been compared over the entire eruptive period (September to December 2021). For SO2 total vertical column, data obtained with the Brewer spectrophotometer of the Izaña Observatory at 144 km distance to the vent have been used. Good qualitative agreement throughout the entire eruptive period of the Tajogaite volcano has been found. A quantitative comparison has proven difficult because of the different FOVs of both instruments and the associated uncertainties. For volcanic plume height, measurements performed with several lidar instruments stationed across La Palma have been employed. When compared to the TROPOMI SO2 layer height retrieval, differences have been found to be in the range of 1–3 km. In view of the methodological differences and adverse effects such as the temporal mismatch between the measurements, differing FOVs of the instruments, and interfering clouds, the results are satisfactory. The TROPOMI SO2 layer height retrieval exhibits a slight low bias with respect to the lidar measurements, and the two datasets are correlated with a correlation coefficient of r=0.74.

A new modeling approach based on TROPOMI SO2 VCD measurements and the HYSPLIT trajectory and dispersion model had to be developed to establish the Tajogaite eruption as the source of the aerosol which was subsequently observed over Lindenberg after its long-range transport. This endeavor became necessary because the direct retrieval of the SO2 layer height from the TROPOMI measurements was not possible due to the low SO2 content of the air masses. The extensive model calculations have shown that the aerosol measured by RAMSES on 26–27 September 2021 could indeed be traced backed to the Tajogaite eruptions around 23 September 2021. According to this analysis, the volcanic plume over Germany was at heights between 3 and 6 km (at the time of the TROPOMI measurement on 26 September) and was emitted at an injection height of about 2.5–5 km 3–4 d earlier. Both height ranges are in good agreement with the RAMSES measurement and with the lidar and TROPOMI observations near the volcano, respectively.

The RAMSES measurements have been discussed in detail. The analysis of the particle elastic and inelastic optical properties of the volcanic aerosol showed that it consisted of inorganic, small, solid, and irregularly shaped particles, the presence of large aerosol particles such as volcanic ash or Saharan dust as well as wildfire aerosols could be excluded. A new retrieval approach has been developed to estimate the microphysical properties of the volcanic aerosol. The parameters of the assumed normalized monomodal and lognormal size distribution are retrieved from the measured particle lidar ratio and particle depolarization ratio, and the number density is from the measured particle backscatter coefficient. For the first time, an optical particle model has been utilized that assumes an irregular, non-spheroidal shape of the aerosol particles. According to the microphysical retrieval, the particles of volcanic origin likely had an isometric to slightly plate-like shape with an effective half of the particle maximum dimension around 0.1 µm and a real part of the refractive index of about 1.51. Moreover, mass column values between 70 and 110 mg m−2, mean mass concentrations of 45–70 µg m−3, and mean mass conversion factors between 0.21 and 0.33 g m−2 at 355 nm have been retrieved. A detailed discussion suggests that possibly RAMSES observed, at least in part, volcanic secondary sulfate aerosol which was produced by gas-phase homogeneous reactions during the transport of the air masses from La Palma to Lindenberg.

The microphysical retrieval is currently being extended to bimodal size distributions. It is planned to release the program code after further testing. Information about the AEMET ash LH retrieval will become available once the article of Barreto et al. (2025) is published.

Sentinel-5P/TROPOMI observations are distributed via the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (https://doi.org/10.5270/S5P-74eidii, ESA S5P, 2022). TROPOMI SO2 LH data are available upon request via https://atmos.eoc.dlr.de/so2-lh/ (S5P+I SO2LH, 2022). Brewer SO2 data are available from the website of EUBREWNET: European Brewer Network, http://rbcce.aemet.es/eubrewnet/ (EUBREWNET, 2024). RAMSES measurements are available upon request. AEMET ash LH data are available upon request and will be available with a corresponding DOI once the paper of Barreto et al. (2025) is published. NCEP/GFS0.25 meteorologic data is available from the NOAA/NCEP website (https://doi.org/10.5065/D65D8PWK, NCEP/GFS0.25, 2015).

PH conceived the study with the help of DL and wrote part of the manuscript. PH and FL carried out the TROPOMI and Lindenberg HYSPLIT analysis and retrievals. JR performed and analyzed the RAMSES measurements, developed and applied the microphysical retrieval scheme, and wrote part of the manuscript. BW performed the TROPOMI HYSPLIT analysis and wrote Sect. 4.2. AR provided the IZO Brewer data and support. AB and OG provided the AEMET ash layer height dataset. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and writing of the paper.

The contact authors have declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The authors would like to thank the PIs and technical staff of the lidar instruments on the Canary Islands for the datasets of the altitude of the dispersion plume, namely the following:

-

CommSensLab, Dept. of Signal Theory and Communications, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC), Spain: Michaël Sicard, Constantino Muñoz-Porcar, Adolfo Comerón, Alejandro Rodríguez-Gómez

-

Atmospheric Research and Instrumentation Branch, Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (INTA), Spain: Carmen Córdoba-Jabonero, María Ángeles López-Cayuela, Clara Carvajal-Pérez

-

ONERA, the French Aerospace Lab, Universite de Toulouse, France: Andrés Bedoya-Velázquez, Romain Ceolato

-

Group of Atmospheric Optics, Universidad de Valladolid, Spain: Roberto Román

-

Vaisala Oyj, Finland: Reijo Roininen

-

INFN-GSGC L’Aquila and CETEMPS-DSFC, Università degli Studi dell’Aquila, Italy: Marco Iarlori, Vincenzo Rizi, Ermanno Pietropaolo

-

INFN Napoli, Complesso Universitario Monte Sant’Angelo, Italy: Carla Aramo

The authors thank the European Brewer Network (http://rbcce.aemet.es/eubrewnet/, last access: 20 January 2025) for providing access to the data.

This study was partially funded by the DLR projects S5P and INPULS (KTR 2472046 and 2472922). AB and OG acknowledge the support of the ACTRIS Research Infrastructure Project by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program through ACTRIS-IMP (grant agreement no. 871115) and ACTRIS Spain.The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

This paper was edited by Eduardo Landulfo and reviewed by Alessia Sannino and two anonymous referees.

Allen, A. G., Oppenheimer, C., Ferm, M., Baxter, P. J., Horrocks, L. A., Galle, B., McGonigle, A. J. S., and Duffell, H. J.: Primary sulfate aerosol and associated emissions from Masaya Volcano, Nicaragua, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, ACH5-1–ACH5-8, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002120, 2002. a

Ansmann, A., Tesche, M., Groß, S., Freudenthaler, V., Seifert, P., Schwarz, A., Schmidt, J., Wandinger, U., Mattis, I., Müller, D., and Wiegner, M.: The 16 April 2010 major volcanic ash plume over central Europe: EARLINET lidar and AERONET photometer observations at Leipzig and Munich, Germany, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L13810, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043809, 2010. a

Baars, H., Ansmann, A., Engelmann, R., and Althausen, D.: Continuous monitoring of the boundary-layer top with lidar, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 7281–7296, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-7281-2008, 2008. a

Barreto, Á, Quirós, F., García, O. E., Pereda-de-Pablo, J., González, D., Bedoya-Velázquez, A., Sicard, M., Córdoba, C., Iarlori, M., Rizi, V., Hedelt, P., Krotkov, N., Carn, S., Molina-Arias, A. J., Fernando Almansa, A., Aramo, C., Bustos, J. J., Li, C., Carvajal-Pérez, C. V., Ceolato, R., Comerón, A., Cuevas, E., Felpeto, A., García, R. D., López-Cayuela, M.-Á., Loyola, D., Meletlidis, S., Muñoz-Porcar, C., Pietropaolo, E., Ramos, R., Rodríguez-Gómez, A., Roininen, R., Román, R., Romero-Campos, P. M., Stuefer, M., Toledano, C., and Welton, E.: Description of the eruption on Cumbre Vieja (La Palma) from a multidisciplinary perspective. Evaluation of satellite SO2 and aerosol heights and SO2 mass emission estimations, in preparation, 2025.

Bedoya-Velásquez, A. E., Hoyos-Restrepo, M., Barreto, A., García, R. D., Romero-Campos, P. M., García, O., Ramos, R., Roininen, R., Toledano, C., Sicard, M., and Ceolato, R.: Estimation of the Mass Concentration of Volcanic Ash Using Ceilometers: Study of Fresh and Transported Plumes from La Palma Volcano, Remote Sens., 14, 5680, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14225680, 2022. a, b, c, d

Brooks, S. D., Wise, M. E., Cushing, M., and Tolbert, M. A.: Deliquescence behavior of organic/ammonium sulfate aerosol, Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 23-1–23-4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014733, 2002. a

Carn, S., Clarisse, L., and Prata, A.: Multi-decadal satellite measurements of global volcanic degassing, J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res., 311, 99–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.01.002, 2016. a

Carn, S. A., Krotkov, N. A., Theys, N., and Li, C.: Advances in UV Satellite Monitoring of Volcanic Emissions, in: 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, 973–976 pp., https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS47720.2021.9554594, 2021. a

Carracedo, J. C., Troll, V. R., Day, J. M. D., Geiger, H., Aulinas, M., Soler, V., Deegan, F. M., Perez-Torrado, F. J., Gisbert, G., Gazel, E., Rodriguez-Gonzalez, A., and Albert, H.: The 2021 eruption of the Cumbre Vieja volcanic ridge on La Palma, Canary Islands, Geol. Today, 38, 94–107, https://doi.org/10.1111/gto.12388, 2022. a, b

Castro, J. M. and Feisel, Y.: Eruption of ultralow-viscosity basanite magma at Cumbre Vieja, La Palma, Canary Islands, Nat. Commun., 13, 3174, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30905-4, 2022. a

Coppola, D., Laiolo, M., Cigolini, C., Massimetti, F., Delle Donne, D., Ripepe, M., Arias, H., Barsotti, S., Parra, C. B., Centeno, R. G., Cevuard, S., Chigna, G., Chun, C., Garaebiti, E., Gonzales, D., Griswold, J., Juarez, J., Lara, L. E., López, C. M., Macedo, O., Mahinda, C., Ogburn, S., Prambada, O., Ramon, P., Ramos, D., Peltier, A., Saunders, S., de Zeeuw-van Dalfsen, E., Varley, N., and William, R.: Thermal Remote Sensing for Global Volcano Monitoring: Experiences From the MIROVA System, Front. Earth Sci., 7, 362, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00362, 2020. a

Córdoba-Jabonero, C., Sicard, M., África Barreto, Toledano, C., Ángeles López-Cayuela, M., Gil-Díaz, C., García, O., Carvajal-Pérez, C. V., Comerón, A., Ramos, R., Muñoz-Porcar, C., and Rodríguez-Gómez, A.: Fresh volcanic aerosols injected in the atmosphere during the volcano eruptive activity at the Cumbre Vieja area (La Palma, Canary Islands): Temporal evolution and vertical impact, Atmos. Environ., 300, 119667, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119667, 2023. a, b, c, d, e

Ebert, M., Weinbruch, S., Rausch, A., Gorzawski, G., Helas, G., Hoffmann, P., and Wex, H.: Complex refractive index of aerosols during LACE 98 as derived from the analysis of individual particles, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, LAC3-1–LAC3-15, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JD000195, 2002. a, b, c

ESA S5P: Copernicus Sentinel-5P (processed by ESA), 2020, TROPOMI Level 2 Sulphur Dioxide Total Column, Version 02 [data set], https://doi.org/10.5270/S5P-74eidii, 2022. a, b

EUBREWNET: European Brewer Network [data set], http://rbcce.aemet.es/eubrewnet/ (last access: 9 February 2024), 2024. a, b

Filonchyk, M., Peterson, M. P., Gusev, A., Hu, F., Yan, H., and Zhou, L.: Measuring air pollution from the 2021 Canary Islands volcanic eruption, Sci. Total Environ., 849, 157827, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157827, 2022. a, b

Flamant, C., Pelon, J., Flamant, P., and Durand, P.: Lidar Determination of the Entrainment Zone Thickness at the Top of the Unstable Marine Atmospheric Boundary Layer, Bound.-Lay. Meteorol., 83, 247–284, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1000258318944, 1997. a