the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Theoretical framework for measuring cloud effective supersaturation fluctuations with an advanced optical system

Jiangchuan Tao

Hanbing Xu

Li Liu

Pengfei Liu

Wanyun Xu

Weiqi Xu

Chunsheng Zhao

Supersaturation is crucial in cloud physics, determining aerosol activation and influencing cloud droplet size distributions, yet its measurement remains challenging and poorly constrained. This study proposes a theoretical framework to simultaneously observe critical activation diameter and hygroscopicity of activated aerosols through direct measurements of scattering and water-induced scattering enhancement of interstitial and activated aerosols, enabling effective supersaturation measurements. Advanced optical systems based on this framework allow minute- to second-level effective supersaturation measurements, capturing fluctuations vital to cloud microphysics. Although currently limited to clouds with supersaturations below ∼ 0.2 % due to small scattering signals from sub-100 nm aerosols, advancements in optical sensors could extend its applicability. Its suitability for long-term measurements allows for climatological studies of fogs and mountain clouds. When equipped with aerial vehicles, the system could also measure aloft clouds. Therefore, the proposed theory serves as a valuable method for both short-term and long-term cloud microphysics and aerosol–cloud interaction studies.

- Article

(2216 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(583 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Clouds and fogs play critical roles in weather patterns and climate change, influencing both precipitation and the radiative balance of the Earth's atmosphere. As such, they are central to accurate weather and climate predictions. Despite their importance, representing clouds accurately in atmospheric models remains a significant challenge (Seinfeld et al., 2016). Supersaturation, defined as the difference between the actual water vapor pressure (e) and the saturation vapor pressure (es), which is typically expressed as a dimensionless quantity (e-es)/es, is a key parameter that links aerosols to clouds through the process of aerosol activation, making it fundamental to cloud physics (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). Despite its importance, supersaturation is difficult to measure and remains poorly understood and constrained (Yang et al., 2019). Previous studies have highlighted that other than the mean supersaturation, supersaturation fluctuations also play critical roles in aerosol activation and cloud droplet growth, ultimately influencing the evolution of cloud droplet size distributions (Kaufman and Tanré, 1994; Sardina et al., 2015; Chandrakar et al., 2018, 2020; Shaw et al., 2020). For instance, cloud chamber experiments have shown that supersaturation fluctuations promote aerosol activation and enhance aerosol activity (Shawon et al., 2021; Anderson et al., 2023), particularly when the magnitude of these fluctuations is comparable to the mean supersaturation (Prabhakaran et al., 2020). Both experimental and theoretical analyses suggest that supersaturation fluctuations can broaden cloud droplet size distributions (Chandrakar et al., 2016; Abade et al., 2018; Saito et al., 2019).

Supersaturation fluctuations arise not only from turbulent variations in the temperature and vapor pressure fields but also from the growth and evaporation of droplets, which drive mass and heat exchange between droplets and the surrounding air. As noted by Shaw et al. (2020), measuring supersaturation remains a formidable challenge due to its extreme sensitivity to variations in water vapor pressure and temperature. Although current techniques of water vapor and temperature measurements cannot accurately achieve measurements of supersaturation, direct measurements of water vapor pressure and temperature have previously been used to estimate supersaturation fluctuations, and obtained results have demonstrated that supersaturation is indeed a fluctuating quantity (Ditas et al., 2012; Siebert and Shaw, 2017). Currently, cloud and fog supersaturation is typically retrieved from aerosol activation measurements (Ditas et al., 2012) or estimated from vertical velocity measurements and droplet size distribution measurements (Siebert and Shaw, 2017; Cooper, 1989). Supersaturation parameterizations based on vertical velocity are common in models (Abdul-Razzak et al., 1998), while field measurements often rely on aerosol activation data to investigate supersaturation fluctuations and evolution in clouds and fogs (Ditas et al., 2012; Hammer et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2018; Mazoyer et al., 2019; Zíková et al., 2020; Wainwright et al., 2021; Kuang et al., 2024). In addition, supersaturations were also estimated using the closure between cloud droplet number and cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) measurements at various supersaturations (Yum et al., 1998; Sanchez et al., 2016, 2021; Saliba et al., 2023).

In summary, direct measurements of water vapor pressure and temperature are essential for quantifying supersaturations; however, they are nearly impossible with current technologies. Supersaturation measurements from aerosol and cloud microphysics monitoring often reflect an effective supersaturation that drives aerosol activation, which is indeed critical in cloud physics. The complexity of cloud formation and evolution and the central role of supersaturation in these processes underscore the need for precise measurement and representation of supersaturation. Advancements in measuring and understanding supersaturation are essential for improving the accuracy of models and reducing uncertainties in weather and climate predictions. In this study, we propose a theoretical framework for using optical methods to observe effective supersaturations based on aerosol activation in clouds and preliminarily validated utilizing data obtained from field campaigns. The feasibility of employing an advanced optical system to measure supersaturation fluctuations was also explored and discussed.

2.1 Observing effective supersaturations on the basis of κ-Köhler theory

The concept of effective supersaturation was introduced based on aerosol activation measurements (Hudson and Yum, 1997; Hudson et al., 2010), which could be defined as the supersaturation in the CCN chamber (CCN activation under constant supersaturation conditions) that resulted in the same aerosol activation fraction with the observed aerosol activation fraction in clouds. Quick fluctuations in supersaturation would result in the effective supersaturation, which, directly determined by aerosol activation, differs from the mean supersaturation, which is determined by average water vapor content and temperature. However, the concept of κ-Köhler theory is established according to a constant supersaturation scenario, therefore providing a framework for deriving effective supersaturation from aerosol activation measurements in clouds (Petters and Kreidenweis, 2007):

where S is the saturation ratio over an aqueous solution droplet with a diameter of D, Dd is the dry diameter, is the surface tension of the solution–air interface, T is the temperature, Mwater is the molecular weight of water, R is the universal gas constant, ρw is the density of water, and κ is the hygroscopicity parameter. The κ-Köhler theory tells us that if the critical diameter of aerosol activation (Da) and corresponding aerosol hygroscopicity parameter κ are known, the surrounding supersaturation can be retrieved based on air temperature measurements and by assuming the surface tension of water (as shown in Fig. S1a in the Supplement). Note that Da and κ are not independent of each other; the average κ of aerosols with diameter Da is needed. Previous studies have shown that the reduction in surface tension (Nozière et al., 2010; Gérard et al., 2016; Ovadnevaite et al., 2017) associated with surfactants in atmospheric aerosols can affect aerosol activation and, consequently, the derivation of effective supersaturation. However, if the derivation of κ (as done in this study) assumes a constant water surface tension, the impact of surface tension changes is minimized, as these effects are already incorporated in the κ calculation. Nonetheless, differences in surface tension between supersaturated and subsaturated conditions (Davies et al., 2019; Petters and Kreidenweis, 2013; Liu et al., 2018), and their impact on effective supersaturation, still exist. Additionally, prior research has suggested that slightly soluble components in aerosols can influence κ values under both supersaturated and subsaturated conditions (Ho et al., 2010; Petters and Kreidenweis, 2008; Lee et al., 2022; Han et al., 2022; Riipinen et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019; Whitehead et al., 2014). Therefore, κ observed under subsaturated conditions would affect the derivation of effective supersaturation.

However, the simultaneous measurements of Da and κ of activated aerosols with diameters around Da are indeed challenging. Direct measurements of the size-resolved activation ratio (AR) in clouds are essential for Da retrievals through the following equation:

where Dp is the particle diameter, MAF is the maximum activation fraction, Da is the critical activation diameter, and σ is associated with the slope of the size-resolved AR curve near Da and mostly influenced by the heterogeneous distribution of aerosols near Da as well as supersaturation fluctuations (note that not effective supersaturation fluctuations). This formula was previously proposed by Rose et al. (2008) to fit the AR measurements and is widely used in AR parameterizations (Tao et al., 2018b). Therefore, it typically requires a unique inlet system and a suite of instruments that measure the aerosol size distribution of both interstitial and total aerosol populations (Hammer et al., 2014; Zíková et al., 2020). Consequently, this is rarely done, even in ground fog measurements. Instead, Da was usually estimated from aerosol measurements, and fog droplet size distribution measurements, which indirectly provide the number concentrations of activated aerosols, therefore could be used in retrieving Da through assuming that all aerosols larger than Da are activated (Mazoyer et al., 2019; Wainwright et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2018), which brings uncertainty in Da derivations due to the fact that not all aerosols larger than Da are activated because the MAF in Eq. (2) does not equal 1, although it is usually very close to Tao et al. (2018b). For the effective supersaturation measured in aloft clouds, the aerosol number size distributions inside and outside the cloud as well as cloud droplet number concentrations were used by Ditas et al. (2012) to derive Da, and other approaches were also used (Gong et al., 2023). The κ values were usually retrieved from size-resolved cloud condensation nuclei measurements under certain supersaturations (Hammer et al., 2014; Mazoyer et al., 2019) or from growth factor measurements (Wainwright et al., 2021) or sometime assumed due to the lack of measurements. The κ values of activated aerosols were not directly measured in these studies due to the difficulty of the direct sampling of activated aerosols as well as subsequent hygroscopicity measurements.

Two types of supersaturation fluctuations have been previously identified. The first type involves fluctuations in supersaturation directly governed by water vapor pressure and temperature, as described by Siebert and Shaw (2017). These fluctuations are linked to turbulence and water phase changes that influence water vapor pressure and temperature. The second type concerns fluctuations in effective supersaturation, which are associated with the activation and deactivation processes of aerosols, as noted by Ditas et al. (2012). The first type of fluctuations dictates the instantaneous growth and evaporation of droplets, thereby controlling the activation and deactivation of cloud droplets. As such, the second type of fluctuation is inherently driven by the first type. The theoretical framework proposed in this study enables the measurement of fluctuations in effective supersaturation.

2.2 Field measurements

Kuang et al. (2024) developed an advanced aerosol–cloud sampling system designed to measure fog and cloud activation processes. This compact, integrated system can automatically switch between different inlets, including a PM1 impactor (particles and droplets with an aerodynamic diameter <1 µm), a PM2.5 impactor (particles and droplets with an aerodynamic diameter <2.5 µm), and total suspended particles (TSPs; encompassing all particles and droplets) (as shown in Fig. S2). When combined with instruments that measure aerosol physical, optical, and chemical properties, this system is well suited for investigating cloud microphysics and chemistry. It was utilized in the AQ-SOFAR campaign, dedicated to studying AQueous Secondary aerOsol formation in Fogs and Aerosols and their Radiative effects in the North China Plain (Kuang et al., 2024).

During this campaign, several radiation fog events were observed, enabling the measurement of size-resolved AR curves, aerosol hygroscopicity, and chemical compositions of interstitial and activated aerosols within fogs. These measurements provided insights into the evolution of supersaturations (Kuang et al., 2024). Notably, aerosol hygroscopicity was determined using a humidified nephelometer system, located downstream of the inlet system. This system measured multiwavelength scattering coefficients (450, 525, 635 nm) under both nearly dry (RH < 20 %) and humid conditions (RH ∼ 84 %), offering aerosol hygroscopicity data based on the optical theory proposed by Kuang et al. (2017). The size-resolved AR curves and aerosol chemical compositions were obtained through the aerosol size distribution and the aerosol mass spectrometry measurements downstream of the inlet system. A schematic of the inlet system and associated instruments is provided in Fig. S1. Further details about the entire experimental setup, size-resolved AR calculations, and data analysis about mass spectrometer measurements can be found in Kuang et al. (2024).

In addition, the particle number size distributions (PNSDs) in the dry state, which range from about 10 nm to 10 µm, were jointly measured by a twin differential mobility particle sizer (TDMPS; Leibniz-Institute for Tropospheric Research, Germany) or a scanning mobility particle size spectrometer (SMPS) and an aerodynamic particle sizer (APS; TSI Inc., Model 3321) in six field campaigns conducted on the North China Plain, which are detailed in Kuang et al. (2018). The mass concentrations of black carbon (BC) were measured using a multi-angle absorption photometer (MAAP; Model 5012, Thermo, Inc., Waltham, MA USA) or an aethalometer (AE33) (Drinovec et al., 2015) in these field campaigns. Details about these measurements and quality assurance were introduced in Kuang et al. (2018).

2.3 Method of simulating scattering coefficients of interstitial aerosols and activated aerosols

For each paired PNSD and BC mass concentration, the size distribution of dry-state PM1 was obtained using the following formula (the penetration curve shape from Gussman et al. (2002) was also included for considering the nonideality cutoff of the impactor and assuming aerosol density of 1.6 g cm−3 for converting the aerodynamic diameter to the mobility diameter):

where R(Dp) is the penetration ratio of aerosols as a function of the particle diameter Dp of the PM1 impactor. Further, and the BC mass concentration were used to simulate the size-resolved aerosol scattering coefficients () at 450, 525, and 636 nm, consistent with the angular truncation and light source nonideality of the Aurora 3000 nephelometer (Müller et al., 2011), where σsp represents the aerosol scattering coefficient. In this Mie calculation, the shape of black carbon mass size distributions is consistent with the one used in simulations of Kuang et al. (2017) assuming fractions of BC mass that are externally mixed are 0.5. Details about the Mie theory calculations can also be found in Ma et al. (2011) and Kuang et al. (2017).

With the given size-resolved AR curve that was produced using Eq. (2), the size-resolved aerosol scattering coefficients of interstitial aerosols can be calculated using the following formula:

The size-resolved aerosol scattering coefficients of activated aerosols can be calculated using

Scattering coefficients of total aerosol populations (interstitial plus activated) and interstitial aerosols can be derived through integration of ) and ).

3.1 Theory of observing critical activation diameter using scattering measurements

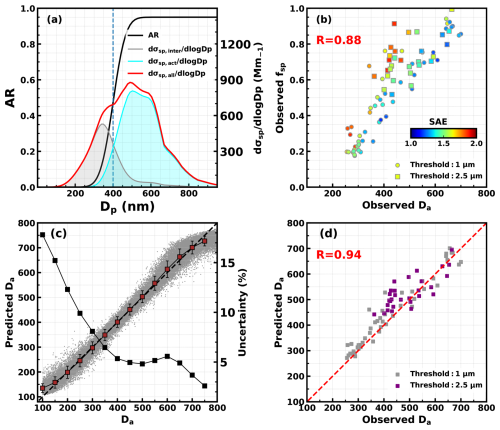

The typical shape of size-resolved AR curves observed in atmospheric fogs and clouds is illustrated in Fig. 1a (Ditas et al., 2012; Hammer et al., 2014; Zíková et al., 2020; Wainwright et al., 2021; Kuang et al., 2024). In clouds, aerosols can be classified as either activated aerosols, which form cloud droplets, or inactivated aerosols, which remain as interstitial aerosols. The critical diameter that distinguishes interstitial aerosols from cloud or fog droplets varies depending on the supersaturation (Kuang et al., 2024). A diameter of 2.5 µm is typically suitable for surface fogs with relatively lower supersaturations (< 0.1 %), while 1 µm is more appropriate for clouds aloft with higher supersaturations (> 0.1 %) (Mazoyer et al., 2019; Kuang et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2020). The typical AR curve shows that most aerosols larger than Da are activated, while most smaller aerosols remain inactivated. As a result, the scattering properties, such as size-resolved scattering coefficients (Fig. 1a), the scattering Ångström exponent (SAE), and its wavelength dependence, which are directly related to aerosol size distribution, differ significantly between interstitial and activated aerosols.

Figure 1(a) The typical shape of size-resolved aerosol activation ratio (AR) curve produced using the function of Eq. (2), with the Da of 400 nm, the MAF of 0.95, and the σ of 30 (as an example). The average PNSD observed in the North China Plain from six campaigns as introduced in Sect. 2.2 and the example AR curve were used to simulate an example of the size-resolved aerosol scattering (σsp) distributions of interstitial and activated aerosols at 525 nm. (b) Relations between observed Da and fsp during the AQ-SOFAR campaign using 1 and 2.5 µm as the threshold of interstitial aerosols, with the scatter points are colored with corresponding SAE of total dry state PM1 aerosols. (c) Comparisons of all prescribed Da and predicted Da values represented by scatter points; they are further binned with intervals of 50 nm. Averages and standard deviations are represented by purple squares and their error bars, and black squares represent relative uncertainty of the right axis at each bin. (d) The comparisons of Da retrieved using activation ratio observations and those predicted using scattering observations as inputs of the trained model; dashed lines represent 1:1 lines.

If we focus on PM1 of the total dry aerosol population (the reasoning for this is discussed in Sect. S1 of the supplement), the scattering fraction of interstitial aerosols in the total dry PM1 population, defined as (dry, 525 nm)/ (dry, 525 nm), where (dry, 525 nm) is the scattering coefficient of PM1 interstitial aerosols in a dry state at a wavelength of 525 nm, and (dry, 525 nm) is that of all PM1 aerosols, is likely to be highly correlated with Da. Generally, the larger the Da, the higher the fsp. This relationship was directly confirmed using Da and the scattering properties of dry PM1 interstitial and total aerosols during the AQ-SOFAR campaign, as shown in Fig. 1b, that observed Da correlates highly with observed fsp (R=0.88). However, at a given Da, fsp can vary significantly, and these variations are closely related to the SAE of all dry PM1 aerosols, which are mainly determined by aerosol size distribution. In fact, aside from the size distribution of the total aerosol population that determines SAE, the shape of the AR curve also plays a significant role in the variations of fsp.

The nephelometer measures the aerosol scattering coefficient at three wavelengths, enabling direct measurements of the SAE for both the total dry-state PM1 aerosols and the interstitial aerosols. Therefore, the relationship between fsp and Da can be further constrained by the SAE of interstitial and activated aerosols, as well as their wavelength dependence. This implies that a simple formulaic relationship between fsp and Da may not exist. However, the six scattering parameters – (dry, λ) at 450, 525, and 635 nm and (dry, λ) at 450, 525, and 635 nm – contain both the fsp information and the SAE characteristics of both aerosol groups; thus they can potentially be used to accurately retrieve Da. Machine learning techniques, which are well suited for handling complex relationships, can be applied to this problem.

This assumption was tested using Mie theory, based on aerosol size distributions sampled during six campaigns conducted in the North China Plain region (Kuang et al., 2018). For each aerosol size distribution, we randomly assumed different activation curves using Eq. (2). That is, for each PNSD from those campaigns, the scattering coefficients of submicron interstitial and activated + interstitial aerosols at wavelengths of 450, 525, and 635 nm corresponding to the nephelometer case under 100 size-resolved AR scenarios were simulated using the procedure. And each size-resolved AR curve was produced using randomly produced Da, σ, and MAF as inputs of Eq. (2). In the random step, the range of Da is 100–700 nm, the range of σ is 1–30, and the range of MAF is 0.5–1. In each pair, simulated (dry, λ) at 450, 525, and 635 nm and (dry, λ) at 450, 525, and 635 nm were the x values of the random forest model; the corresponding Da is the y value of the random forest model, and the random forest package from Python Scikit-Learn machine learning library (http://scikit-learn.org/stable/index.html, last access: 22 January 2025) is used for this purpose. With these configurations, more than a million pairs are simulated. To preliminarily validate this approach, we randomly selected 75 % of the simulated data pairs for training the model, while the remaining 25 % were used for validation.

The results, shown in Fig. 1c, indicate that this approach could retrieve Da with an uncertainty of less than 10 % for Da larger than 250 nm and even as low as ∼ 6 % for Da larger than 350 nm. However, the uncertainty increases as Da decreases, particularly for Da smaller than 250 nm. The larger uncertainty at smaller Da is since aerosols smaller than 250 nm typically contribute less than 10 % to total scattering in the dry state, making fsp less sensitive to variations in Da. This issue becomes more pronounced when Da is less than 100 nm, as aerosols smaller than 150 nm generally contribute negligibly to total aerosol scattering (Kuang et al., 2018). This method was further validated using observations from the AQ-SOFAR campaign. In this validation, Da values were first predicted using aerosol scattering observations with the trained model and then compared with Da values retrieved from size-resolved AR measurements, as shown in Fig. 1d. It should be noted that the impactor operates in a sequence of PM1, PM2.5, TSP, and then back to PM1, with the flow alternating between a thermodenuder and bypass every 10 min for each inlet. To calculate size-resolved AR curves, we assumed that aerosol populations remained unchanged during the 30 min period (based on comparisons between PM1/PM2.5 and TSP inlets), which can sometimes introduce significant uncertainties in the size-resolved AR calculations. When using PM2.5 as the threshold, the much lower number concentrations of aerosols larger than 400 nm can introduce more uncertainty in Da retrievals, partially explaining the lower performance in Fig. 1d when using the PM2.5 threshold.

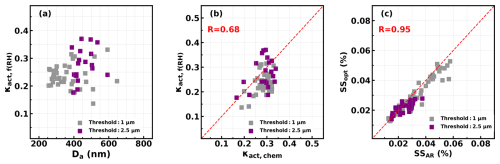

3.2 Method of observing the hygroscopicity of activated aerosols

Measuring the hygroscopicity κ of activated aerosols at the critical activation diameter Da under varying supersaturations is challenging, not only due to technical limitations but also because of the inherent variability in Da. Kuang et al. (2017) introduced a novel optical method for observing aerosol hygroscopicity using the aerosol light scattering enhancement factor f(RH) that is associated with aerosol hygroscopic growth. This method is particularly suitable for the objectives outlined here. The method requires SAE and light scattering enhancement factors f(RH) of activated aerosols as inputs, and retrieved κ can be termed as κact, f(RH), which represents the overall hygroscopicity of activated aerosols and can be understood as the average κ of activated aerosols with the scattering contribution of each aerosol particle as the weight (Kuang et al., 2020). The scattering coefficients of activated aerosols at multiwavelength can be calculated as (dry, λ) (dry, λ) (dry, λ); therefore corresponding SAE can be obtained. The f(RH) of activated aerosols at 525 nm can be calculated as follows:

During the AQ-SOFAR campaign, a humidified nephelometer system consisting of two nephelometers – one measuring aerosol scattering in the dry state and the other at a fixed RH of 84 % – was placed downstream of the PM1 impactor. This setup allows for the humidification of dry-state interstitial aerosols and total aerosol populations to a high RH (e.g., above 80 %), facilitating the required measurements, therefore severing one choice. The retrieved κact, f(RH) under different Da conditions are shown in Fig. 2a, demonstrating significant variations in κact,f(RH), and its variations need to be constrained. Also, the derived κact,f(RH) values are compared to those estimated from aerosol chemical composition measurements (κact,chem; details about calculation methods can refer to Kuang et al., 2020), as shown in Fig. 2b, and in general agree. Note that the mass spectrometer could not identify all aerosol components, and assumptions about the mixing rule as well as densities of components would bring uncertainties (Kuang et al., 2021). The comparisons between effective supersaturations derived from size-resolved AR measurements as well as κact,chem and from the optical method are shown in Fig. 2c. On average, 0.002 % of supersaturation (SS) bias is observed due to the bias of Da, which is associated more with assumptions made in Da retrievals as previously discussed. As demonstrated by Kuang et al. (2024), for the fog case in the campaign, the threshold of 2.5 µm should be used; however, it does not affect the comparisons here.

Qiao et al. (2024) developed an advanced outdoor nephelometer system that measures aerosol dry scattering coefficients and scattering coefficients at nearly ambient RH without the need for humidifying the sample air by placing the entire nephelometer system in ambient air, with the instruments protected by a specially designed enclosure. This innovative design offers new insights into the hygroscopicity measurements of activated aerosols. Under cloud conditions, where the ambient RH is close to 100 %, aerosol scattering under subsaturated conditions can be measured directly by applying heat.

Figure 2(a) Retrieved κact, f(RH) under different Da conditions. (b) Comparison between κ of activated aerosols retrieved from the optical method (κact, f(RH)) and estimated from aerosol chemical composition measurements (κact, chem). (c) Comparisons between effective supersaturations (SSs) derived from size-resolved AR measurements as well as κact, chem (SSAR) and from the optical measurements (SSopt). Dashed red lines represent 1:1.

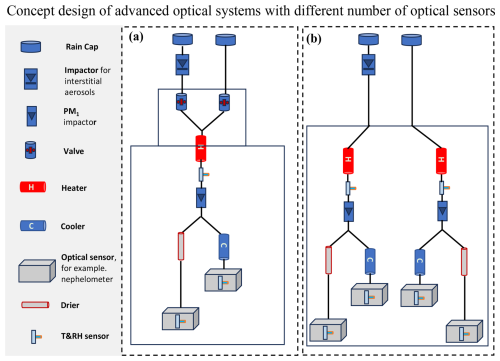

3.3 Concept design of the advanced optical system for measuring effective supersaturations

Based on the proposed optical methods for measuring Da and κact,f(RH), a conceptual design for outdoor instruments capable of measuring effective supersaturation with relatively high time resolution can be envisioned, as shown in Fig. 3a. The aerosol–cloud sampling system includes two inlets: one equipped with a PM1 or PM2.5 impactor (depending on cloud type) to sample interstitial aerosols and another with a TSP inlet to sample both interstitial aerosols and cloud/fog droplets. A PM1 impactor is placed downstream of the inlet system, where the RH of the sample air is reduced to 70 % (as discussed in Sect. S1 in the Supplement) using a heater. Downstream of the PM1 impactor, the sample flow is split into two streams: one is further dried to an RH below 10 % before aerosol scattering coefficients are measured by the “dry” nephelometer, and the other is passed through an intelligent cooler to ensure the sample RH in the “wet” nephelometer remains close to 90 %. The sample air is automatically switched between the interstitial inlet and the TSP inlet at set intervals, such as 1 min for each inlet, enabling minute-level measurements of effective supersaturations. While the nephelometer can output scattering measurements every second, reliable data can only be achieved at intervals of around 30 s (exact values can be determined through future testing) due to the residence time of aerosols in the nephelometer and potential light source instability. If four nephelometers are available, a more advanced optical system can be designed (Fig. 3b) that does not require switching between the interstitial inlet and the TSP inlet. Instead, two nephelometers would be placed downstream of the interstitial inlet and two downstream of the TSP inlet, enabling higher-time-resolution effective supersaturation measurements. Other types of optical instruments exist that can achieve stable second-level aerosol scattering or extinction measurements with a stable laser light source (Moise et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2020). Therefore, with the development of suitable optical instruments, it may be possible to achieve second-level effective supersaturation measurements.

Figure 3Concept design of the advanced optical system with different number of optical sensors, (a) using two nephelometers or other optical sensors and (b) using four nephelometers or other optical sensors. The heater upstream of the sample is used to reduce the relative humidity (RH) to below 60 %, ensuring the evaporation of most of the water content, to ensure the consistency of the needed PM1 diameter cut. The cooler upstream of the “wet” nephelometer increases the sample RH to approximately 90 %, allowing hygroscopicity measurements under conditions close to supersaturation.

The proposed theoretical framework enables simultaneous measurements of Da and κ for activated aerosols, leveraging the high time resolution of optical instruments to potentially provide second-level measurements of supersaturation. However, several limitations should be discussed and might be improved upon:

-

Shape of size-resolved AR curve. Cloud chamber studies have shown that supersaturation fluctuations can lead to the coexistence of particles with the same critical supersaturation as both interstitial aerosols and cloud droplets (Shawon et al., 2021). This results in size-resolved AR curves deviating more from a stepwise shape, a phenomenon also observed in some field measurements (Henning et al., 2004; Mertes et al., 2007). Despite this, a critical diameter Da still exists, and such nonideal curves can be treated a high standard deviation σ in the activation error function (Eq. 2), which does not fundamentally undermine the proposed framework; however, it should be further checked for different cloud types.

-

Measurement of κ. Although the framework measures the overall κ of activated aerosols, the κ needed for supersaturation calculations is that of aerosols near Da (). For 200 nm, the derived κact,f(RH) can provide a first-order estimate of , based on observed size-dependent characteristics of κ values (Liu et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024), though more comprehensive evaluations are needed. Additionally, κ measured under subsaturated conditions differs from that under supersaturated conditions (Tao et al., 2023) and might also bring some uncertainties. However, as shown in Fig. S1b, even a bias of 0.1 in κ only results in a ∼ 0.01 % bias when SS is ∼ 0.1 % and a ∼ 0.005 % bias when SS is ∼ 0.05 % in supersaturation retrievals, making the first-order estimates of from optical measurements generally suitable for supersaturation observations.

-

Limitations in Da retrievals. Current techniques using aerosol scattering measurements at visible wavelengths (e.g., nephelometers) are reliable only for Da>100 nm as shown in Fig. 1a, limiting effective supersaturation measurements to less than 0.21 % (assuming a typical κ of 0.3). This restriction makes the technique most applicable to fog and stratus or stratocumulus cloud measurements. However, incorporating scattering measurements at ultraviolet wavelengths could improve sensitivity to smaller Da and lower κ, enabling measurements in conditions with higher effective supersaturation and a broader range of cloud types in the future.

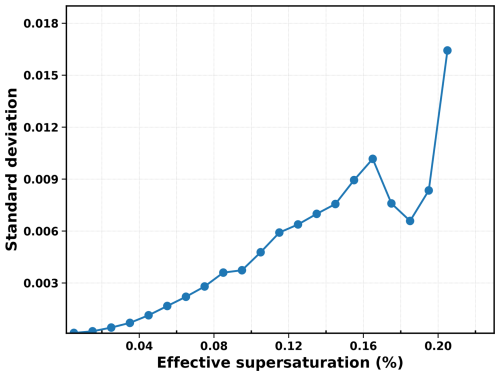

The uncertainty in effective supersaturation observations using this framework primarily arises from the uncertainties in deriving Da and . The uncertainty in Da observations using the Aurora 3000 nephelometer as the optical sensor under varying conditions is detailed in Fig. 1c. Factors affecting the accuracy of include (1) the size dependence of κ of activated aerosols and (2) uncertainties related to surface tension, slightly soluble components, and other factors that lead to κ differences under subsaturated and supersaturated conditions. Based on previous studies on the size dependence of κ (Peng et al., 2020) and the differences between subsaturated and supersaturated conditions (Whitehead et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2023), a 50 % uncertainty (3 times the standard deviation) was assumed in the derivation of for the uncertainty analysis. Using this approach, the uncertainty in effective supersaturation measurements, estimated through the Monte Carlo method, is shown in Fig. 4. The analysis indicates that applying this framework with the Aurora 3000 nephelometer as the optical sensor results in an uncertainty of approximately 5 %. The precision of effective supersaturation measurements is directly linked to the accuracy of the optical sensor's scattering signal. For example, the Aurora 3000 has an accuracy of 1 Mm−1, which leads to different levels of precision in Da and hygroscopicity measurements depending on the scattering signal strength. If the scattering signal from the total aerosol population is 100 Mm−1, the precision of the observed interstitial aerosol scattering fraction fsp is about 1 %. Based on the relationship between fsp and Da shown in Fig. 1b, this leads to a precision of approximately 3 nm for Da, which results in an effective supersaturation precision of ∼ 0.01 % when supersaturation is near 0.2 % or ∼ 0.0002 % when supersaturation is near 0.02 %. However, if the scattering signal is lower (e.g., 10 Mm−1), a bias of 1 Mm−1 could result in effective supersaturation bias to as much as ∼ 0.07 % when supersaturation is near 0.2 %, making the measurements unreliable. In summary, while the proposed framework demonstrates the feasibility of observing effective supersaturation with an advanced optical system, the accuracy and precision depend on the resolution of the optical sensors, the scattering parameters being measured, and the scattering signal levels of aerosols in clouds. Enhancing the sensor precision to 0.1 Mm−1 or even 0.01 Mm−1 and incorporating ultraviolet wavelengths and multiple scattering angles might enable high-accuracy supersaturation measurements across a broad range of supersaturation conditions, especially in cleaner environments.

Figure 4The standard deviations of effective supersaturations under different effective supersaturation (SS) levels.

As mentioned in Sect. 2.1, the theoretical framework proposed in this study is designed to observe effective supersaturation fluctuations, rather than supersaturation fluctuations themselves. While there are non-negligible uncertainties associated with observing effective supersaturation using the proposed theory, the size and hygroscopicity distributions of total interstitial and activated aerosol populations remain nearly constant when measured with second-scale or shorter time resolution. The parameter that changes over time is the dynamic exchange between interstitial and activated aerosols. Consequently, fluctuations in the scattering signals of interstitial and activated aerosols can reflect this exchange at high temporal resolution. Since effective supersaturation fluctuations result from underlying supersaturation variations, they could, in principle, provide insights into the causes of these fluctuations, such as turbulence, though this would require further investigation and endeavor. In addition, for size-resolved AR, both σ and MAF are crucial parameters. However, using scattering coefficients at just three wavelengths of Aurora 3000 nephelometer is insufficient for accurately retrieving σ and MAF. If σ and MAF could be measured more precisely through the extended optical framework, it would provide deeper insights into supersaturation fluctuations.

Despite these limitations, the proposed theoretical framework represents the first system capable of directly providing high-time-resolution measurements of effective supersaturations using a single instrument. This system is particularly well suited for surface fog and mountain cloud observations, and when coupled with aerial vehicles, it could also be employed for measurements in aloft clouds. The system offers several advantages for cloud and fog measurements:

-

High-resolution supersaturation measurements. The system can provide measurements of effective supersaturations at even a second-level resolution, making it feasible for observing effective supersaturation fluctuations and supporting investigations into fog and cloud evolution mechanisms.

-

Long-term measurement capability. The optical measurements, such as those from the nephelometer system, are well suited for long-term observations, making it possible to acquire climatological data on the variability of fogs and mountain clouds.

-

Comprehensive aerosol and cloud data. In addition to measuring effective supersaturations, the system directly captures the scattering and hygroscopic properties of both interstitial and activated aerosols. With further algorithm development, it could also retrieve the number concentrations of available cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) at certain supersaturations, as well as cloud droplet number concentrations, based on previous studies that have observed CCN using optical methods (Tao et al., 2018a).

-

Monitoring aerosol hygroscopic behavior. The system continuously monitors aerosol hygroscopic behavior under subsaturated conditions along with the corresponding optical properties. This allows for clear documentation of the formation and dissipation of fog/cloud events, as well as the variation in aerosol optical and hygroscopic properties.

Overall, the datasets generated by this system are well suited for in-depth investigations of cloud physics and aerosol–cloud interactions. This system has the potential to significantly advance fundamental research on clouds and fogs. However, further theoretical studies are needed to refine and optimize this type of system.

All data presented in figures of this paper are freely available at https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL107147 (Kuang et al., 2024), and more specific data will be made available on request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-1163-2025-supplement.

YK conceived the theoretical framework and wrote the manuscript. JT, HX, LL, WX, and WeX participated in the field campaign and conducted measurements of aerosol chemical and physical properties. YS, PL, and CZ reviewed and commented on the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42175083, 42175127) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

This paper was edited by Zhibin Wang and reviewed by four anonymous referees.

Abade, G. C., Grabowski, W. W., and Pawlowska, H.: Broadening of Cloud Droplet Spectra through Eddy Hopping: Turbulent Entraining Parcel Simulations, J. Atmos. Sci., 75, 3365–3379, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-18-0078.1, 2018.

Abdul-Razzak, H., Ghan, S. J., and Rivera-Carpio, C.: A parameterization of aerosol activation: 1. Single aerosol type, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 103, 6123–6131, https://doi.org/10.1029/97JD03735, 1998.

Anderson, J. C., Beeler, P., Ovchinnikov, M., Cantrell, W., Krueger, S., Shaw, R. A., Yang, F., and Fierce, L.: Enhancements in Cloud Condensation Nuclei Activity From Turbulent Fluctuations in Supersaturation, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2022GL102635, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL102635, 2023.

Chandrakar, K. K., Cantrell, W., Chang, K., Ciochetto, D., Niedermeier, D., Ovchinnikov, M., Shaw, R. A., and Yang, F.: Aerosol indirect effect from turbulence-induced broadening of cloud-droplet size distributions, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 14243–14248, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1612686113, 2016.

Chandrakar, K. K., Cantrell, W., and Shaw, R. A.: Influence of Turbulent Fluctuations on Cloud Droplet Size Dispersion and Aerosol Indirect Effects, J. Atmos. Sci., 75, 3191–3209, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-18-0006.1, 2018.

Chandrakar, K. K., Saito, I., Yang, F., Cantrell, W., Gotoh, T., and Shaw, R. A.: Droplet size distributions in turbulent clouds: experimental evaluation of theoretical distributions, Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc., 146, 483–504, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3692, 2020.

Cooper, W. A.: Effects of Variable Droplet Growth Histories on Droplet Size Distributions. Part I: Theory, J. Atmos. Sci., 46, 1301–1311, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1989)046<1301:EOVDGH>2.0.CO; 2, 1989.

Davies, J. F., Zuend, A., and Wilson, K. R.: Technical note: The role of evolving surface tension in the formation of cloud droplets, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 2933–2946, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-2933-2019, 2019.

Ditas, F., Shaw, R. A., Siebert, H., Simmel, M., Wehner, B., and Wiedensohler, A.: Aerosols-cloud microphysics-thermodynamics-turbulence: evaluating supersaturation in a marine stratocumulus cloud, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 2459–2468, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-2459-2012, 2012.

Drinovec, L., Močnik, G., Zotter, P., Prévôt, A. S. H., Ruckstuhl, C., Coz, E., Rupakheti, M., Sciare, J., Müller, T., Wiedensohler, A., and Hansen, A. D. A.: The ”dual-spot” Aethalometer: an improved measurement of aerosol black carbon with real-time loading compensation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 1965–1979, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-1965-2015, 2015.

Gérard, V., Nozière, B., Baduel, C., Fine, L., Frossard, A. A., and Cohen, R. C.: Anionic, Cationic, and Nonionic Surfactants in Atmospheric Aerosols from the Baltic Coast at Askö, Sweden: Implications for Cloud Droplet Activation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 2974–2982, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05809, 2016.

Gong, X., Wang, Y., Xie, H., Zhang, J., Lu, Z., Wood, R., Stratmann, F., Wex, H., Liu, X., and Wang, J.: Maximum Supersaturation in the Marine Boundary Layer Clouds Over the North Atlantic, AGU Adv., 4, e2022AV000855, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022AV000855, 2023.

Gussman, R. A., Kenny, L. C., Labickas, M., and Norton, P.: Design, Calibration, and Field Test of a Cyclone for PM1 Ambient Air Sampling, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 36, 361–365, https://doi.org/10.1080/027868202753504461, 2002.

Hammer, E., Gysel, M., Roberts, G. C., Elias, T., Hofer, J., Hoyle, C. R., Bukowiecki, N., Dupont, J.-C., Burnet, F., Baltensperger, U., and Weingartner, E.: Size-dependent particle activation properties in fog during the ParisFog 2012/13 field campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 10517–10533, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-10517-2014, 2014.

Han, S., Hong, J., Luo, Q., Xu, H., Tan, H., Wang, Q., Tao, J., Zhou, Y., Peng, L., He, Y., Shi, J., Ma, N., Cheng, Y., and Su, H.: Hygroscopicity of organic compounds as a function of organic functionality, water solubility, molecular weight, and oxidation level, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 3985–4004, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-3985-2022, 2022.

Henning, S., Bojinski, S., Diehl, K., Ghan, S., Nyeki, S., Weingartner, E., Wurzler, S., and Baltensperger, U.: Aerosol partitioning in natural mixed-phase clouds, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L06101, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL019025, 2004.

Ho, K. F., Lee, S. C., Ho, S. S. H., Kawamura, K., Tachibana, E., Cheng, Y., and Zhu, T.: Dicarboxylic acids, ketocarboxylic acids, α-dicarbonyls, fatty acids, and benzoic acid in urban aerosols collected during the 2006 Campaign of Air Quality Research in Beijing (CAREBeijing-2006), J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 115, D19312, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD013304, 2010.

Hudson, J. G. and Yum, S. S.: Droplet Spectral Broadening in Marine Stratus, J. Atmos. Sci., 54, 2642–2654, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1997)054<2642:DSBIMS>2.0.CO; 2, 1997.

Hudson, J. G., Noble, S., and Jha, V.: Stratus cloud supersaturations, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L21813, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL045197, 2010.

Kaufman, Y. J. and Tanré, D.: Effect of variations in super-saturation on the formation of cloud condensation nuclei, Nature, 369, 45–48, https://doi.org/10.1038/369045a0, 1994.

Kuang, Y., Zhao, C., Tao, J., Bian, Y., Ma, N., and Zhao, G.: A novel method for deriving the aerosol hygroscopicity parameter based only on measurements from a humidified nephelometer system, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 6651–6662, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-6651-2017, 2017.

Kuang, Y., Zhao, C. S., Zhao, G., Tao, J. C., Xu, W., Ma, N., and Bian, Y. X.: A novel method for calculating ambient aerosol liquid water content based on measurements of a humidified nephelometer system, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 2967–2982, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-2967-2018, 2018.

Kuang, Y., He, Y., Xu, W., Zhao, P., Cheng, Y., Zhao, G., Tao, J., Ma, N., Su, H., Zhang, Y., Sun, J., Cheng, P., Yang, W., Zhang, S., Wu, C., Sun, Y., and Zhao, C.: Distinct diurnal variation in organic aerosol hygroscopicity and its relationship with oxygenated organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 865–880, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-865-2020, 2020.

Kuang, Y., Huang, S., Xue, B., Luo, B., Song, Q., Chen, W., Hu, W., Li, W., Zhao, P., Cai, M., Peng, Y., Qi, J., Li, T., Wang, S., Chen, D., Yue, D., Yuan, B., and Shao, M.: Contrasting effects of secondary organic aerosol formations on organic aerosol hygroscopicity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 10375–10391, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-10375-2021, 2021.

Kuang, Y., Xu, W., Tao, J., Luo, B., Liu, L., Xu, H., Xu, W., Xue, B., Zhai, M., Liu, P., and Sun, Y.: Divergent Impacts of Biomass Burning and Fossil Fuel Combustion Aerosols on Fog-Cloud Microphysics and Chemistry: Novel Insights From Advanced Aerosol-Fog Sampling, Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, e2023GL107147, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL107147, 2024.

Lee, W.-C., Deng, Y., Zhou, R., Itoh, M., Mochida, M., and Kuwata, M.: Water Solubility Distribution of Organic Matter Accounts for the Discrepancy in Hygroscopicity among Sub- and Supersaturated Humidity Regimes, Environ. Sci. Technol., 17924–17935, 56, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c04647, 2022.

Liu, H. J., Zhao, C. S., Nekat, B., Ma, N., Wiedensohler, A., van Pinxteren, D., Spindler, G., Müller, K., and Herrmann, H.: Aerosol hygroscopicity derived from size-segregated chemical composition and its parameterization in the North China Plain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 2525–2539, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-2525-2014, 2014.

Liu, P., Song, M., Zhao, T., Gunthe, S. S., Ham, S., He, Y., Qin, Y. M., Gong, Z., Amorim, J. C., Bertram, A. K., and Martin, S. T.: Resolving the mechanisms of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nuclei activity for organic particulate matter, Nat. Commun., 9, 4076, 10.1038/s41467-018-06622-2, 2018.

Lu, C., Liu, Y., Yum, S. S., Chen, J., Zhu, L., Gao, S., Yin, Y., Jia, X., and Wang, Y.: Reconciling Contrasting Relationships Between Relative Dispersion and Volume-Mean Radius of Cloud Droplet Size Distributions, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, e2019JD031868, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD031868, 2020.

Müller, T., Laborde, M., Kassell, G., and Wiedensohler, A.: Design and performance of a three-wavelength LED-based total scatter and backscatter integrating nephelometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 4, 1291–1303, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-4-1291-2011, 2011.

Ma, N., Zhao, C. S., Nowak, A., Müller, T., Pfeifer, S., Cheng, Y. F., Deng, Z. Z., Liu, P. F., Xu, W. Y., Ran, L., Yan, P., Göbel, T., Hallbauer, E., Mildenberger, K., Henning, S., Yu, J., Chen, L. L., Zhou, X. J., Stratmann, F., and Wiedensohler, A.: Aerosol optical properties in the North China Plain during HaChi campaign: an in-situ optical closure study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 5959–5973, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-5959-2011, 2011.

Mazoyer, M., Burnet, F., Denjean, C., Roberts, G. C., Haeffelin, M., Dupont, J.-C., and Elias, T.: Experimental study of the aerosol impact on fog microphysics, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 4323–4344, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-4323-2019, 2019.

Mertes, S., Verheggen, B., Walter, S., Connolly, P., Ebert, M., Schneider, J., Bower, K. N., Cozic, J., Weinbruch, S., Baltensperger, U., and Weingartner, E.: Counterflow Virtual Impactor Based Collection of Small Ice Particles in Mixed-Phase Clouds for the Physico-Chemical Characterization of Tropospheric Ice Nuclei: Sampler Description and First Case Study, Aerosol Sci. Technol., 41, 848–864, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820701501881, 2007.

Moise, T., Flores, J. M., and Rudich, Y.: Optical Properties of Secondary Organic Aerosols and Their Changes by Chemical Processes, Chem. Rev., 115, 4400–4439, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr5005259, 2015.

Nozière, B., Ekström, S., Alsberg, T., and Holmström, S.: Radical-initiated formation of organosulfates and surfactants in atmospheric aerosols, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, L05806, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041683, 2010.

Ovadnevaite, J., Zuend, A., Laaksonen, A., Sanchez, K. J., Roberts, G., Ceburnis, D., Decesari, S., Rinaldi, M., Hodas, N., Facchini, M. C., Seinfeld, J. H., and C, O. D.: Surface tension prevails over solute effect in organic-influenced cloud droplet activation, Nature, 546, 637–641, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22806, 2017.

Peng, C., Wang, Y., Wu, Z., Chen, L., Huang, R.-J., Wang, W., Wang, Z., Hu, W., Zhang, G., Ge, M., Hu, M., Wang, X., and Tang, M.: Tropospheric aerosol hygroscopicity in China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 13877–13903, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-13877-2020, 2020.

Petters, M. D. and Kreidenweis, S. M.: A single parameter representation of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nucleus activity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 1961–1971, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-1961-2007, 2007.

Petters, M. D. and Kreidenweis, S. M.: A single parameter representation of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nucleus activity – Part 2: Including solubility, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 6273–6279, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-6273-2008, 2008.

Petters, M. D. and Kreidenweis, S. M.: A single parameter representation of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nucleus activity – Part 3: Including surfactant partitioning, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 1081–1091, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-1081-2013, 2013.

Prabhakaran, P., Shawon, A. S. M., Kinney, G., Thomas, S., Cantrell, W., and Shaw, R. A.: The role of turbulent fluctuations in aerosol activation and cloud formation, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 16831–16838, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006426117, 2020.

Qiao, H., Kuang, Y., Yuan, F., Liu, L., Zhai, M., Xu, H., Zou, Y., Deng, T., and Deng, X.: Unlocking the Mystery of Aerosol Phase Transitions Governed by Relative Humidity History Through an Advanced Outdoor Nephelometer System, Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, e2023GL107179, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL107179, 2024.

Riipinen, I., Rastak, N., and Pandis, S. N.: Connecting the solubility and CCN activation of complex organic aerosols: a theoretical study using solubility distributions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 6305–6322, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-6305-2015, 2015.

Rose, D., Gunthe, S. S., Mikhailov, E., Frank, G. P., Dusek, U., Andreae, M. O., and Pöschl, U.: Calibration and measurement uncertainties of a continuous-flow cloud condensation nuclei counter (DMT-CCNC): CCN activation of ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride aerosol particles in theory and experiment, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 1153–1179, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-1153-2008, 2008.

Saito, I., Gotoh, T., and Watanabe, T.: Broadening of Cloud Droplet Size Distributions by Condensation in Turbulence, J. Meteorol. Soc. JPN II, 97, 867–891, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2019-049, 2019.

Saliba, G., Bell, D. M., Suski, K. J., Fast, J. D., Imre, D., Kulkarni, G., Mei, F., Mülmenstädt, J. H., Pekour, M., Shilling, J. E., Tomlinson, J., Varble, A. C., Wang, J., Thornton, J. A., and Zelenyuk, A.: Aircraft measurements of single particle size and composition reveal aerosol size and mixing state dictate their activation into cloud droplets, Environ. Sci. Atmos., 3, 1352–1364, https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EA00052D, 2023.

Sanchez, K. J., Russell, L. M., Modini, R. L., Frossard, A. A., Ahlm, L., Corrigan, C. E., Roberts, G. C., Hawkins, L. N., Schroder, J. C., Bertram, A. K., Zhao, R., Lee, A. K. Y., Lin, J. J., Nenes, A., Wang, Z., Wonaschütz, A., Sorooshian, A., Noone, K. J., Jonsson, H., Toom, D., Macdonald, A. M., Leaitch, W. R., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Meteorological and aerosol effects on marine cloud microphysical properties, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 4142–4161, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD024595, 2016.

Sanchez, K. J., Roberts, G. C., Saliba, G., Russell, L. M., Twohy, C., Reeves, J. M., Humphries, R. S., Keywood, M. D., Ward, J. P., and McRobert, I. M.: Measurement report: Cloud processes and the transport of biological emissions affect southern ocean particle and cloud condensation nuclei concentrations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 3427–3446, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-3427-2021, 2021.

Sardina, G., Picano, F., Brandt, L., and Caballero, R.: Continuous Growth of Droplet Size Variance due to Condensation in Turbulent Clouds, Phys. Rev. Lett., 115, 184501, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.184501, 2015.

Seinfeld, J. and Pandis, S.: Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd Edn., John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2016.

Seinfeld, J. H., Bretherton, C., Carslaw, K. S., Coe, H., DeMott, P. J., Dunlea, E. J., Feingold, G., Ghan, S., Guenther, A. B., Kahn, R., Kraucunas, I., Kreidenweis, S. M., Molina, M. J., Nenes, A., Penner, J. E., Prather, K. A., Ramanathan, V., Ramaswamy, V., Rasch, P. J., Ravishankara, A. R., Rosenfeld, D., Stephens, G., and Wood, R.: Improving our fundamental understanding of the role of aerosol-cloud interactions in the climate system, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 5781–5790, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1514043113, 2016.

Shaw, R. A., Cantrell, W., Chen, S., Chuang, P., Donahue, N., Feingold, G., Kollias, P., Korolev, A., Kreidenweis, S., Krueger, S., Mellado, J. P., Niedermeier, D., and Xue, L.: Cloud–Aerosol–Turbulence Interactions: Science Priorities and Concepts for a Large-Scale Laboratory Facility, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 101, E1026–E1035, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-20-0009.1, 2020.

Shawon, A. S. M., Prabhakaran, P., Kinney, G., Shaw, R. A., and Cantrell, W.: Dependence of Aerosol-Droplet Partitioning on Turbulence in a Laboratory Cloud, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2020JD033799, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JD033799, 2021.

Shen, C., Zhao, C., Ma, N., Tao, J., Zhao, G., Yu, Y., and Kuang, Y.: Method to Estimate Water Vapor Supersaturation in the Ambient Activation Process Using Aerosol and Droplet Measurement Data, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 0, 10606–10619, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD028315, 2018.

Shen, C., Zhao, G., Zhao, W., Tian, P., and Zhao, C.: Measurement report: aerosol hygroscopic properties extended to 600 nm in the urban environment, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 1375–1388, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-1375-2021, 2021.

Siebert, H. and Shaw, R. A.: Supersaturation Fluctuations during the Early Stage of Cumulus Formation, J. Atmos. Sci., 74, 975–988, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-16-0115.1, 2017.

Tao, J., Zhao, C., Kuang, Y., Zhao, G., Shen, C., Yu, Y., Bian, Y., and Xu, W.: A new method for calculating number concentrations of cloud condensation nuclei based on measurements of a three-wavelength humidified nephelometer system, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 895–906, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-895-2018, 2018a.

Tao, J., Zhao, C., Ma, N., and Kuang, Y.: Consistency and applicability of parameterization schemes for the size-resolved aerosol activation ratio based on field measurements in the North China Plain, Atmos. Environ., 173, 316–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.11.021, 2018b.

Tao, J., Kuang, Y., Luo, B., Liu, L., Xu, H., Ma, N., Liu, P., Xue, B., Zhai, M., Xu, W., Xu, W., and Sun, Y.: Kinetic Limitations Affect Cloud Condensation Nuclei Activity Measurements Under Low Supersaturation, Geophys. Res. Lett., 50, e2022GL101603, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL101603, 2023.

Wainwright, C., Chang, R. Y.-W., and Richter, D.: Aerosol Activation in Radiation Fog at the Atmospheric Radiation Program Southern Great Plains Site, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 126, e2021JD035358, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035358, 2021.

Wang, J., Shilling, J. E., Liu, J., Zelenyuk, A., Bell, D. M., Petters, M. D., Thalman, R., Mei, F., Zaveri, R. A., and Zheng, G.: Cloud droplet activation of secondary organic aerosol is mainly controlled by molecular weight, not water solubility, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 941–954, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-941-2019, 2019.

Wang, Y., Li, J., Fang, F., Zhang, P., He, J., Pöhlker, M. L., Henning, S., Tang, C., Jia, H., Wang, Y., Jian, B., Shi, J., and Huang, J.: In-situ observations reveal weak hygroscopicity in the Southern Tibetan Plateau: implications for aerosol activation and indirect effects, npj Clim. Atmos. Sci., 7, 77, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00629-x, 2024.

Whitehead, J. D., Irwin, M., Allan, J. D., Good, N., and McFiggans, G.: A meta-analysis of particle water uptake reconciliation studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 11833–11841, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-11833-2014, 2014.

Yang, F., McGraw, R., Luke, E. P., Zhang, D., Kollias, P., and Vogelmann, A. M.: A new approach to estimate supersaturation fluctuations in stratocumulus cloud using ground-based remote-sensing measurements, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 5817–5828, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-5817-2019, 2019.

Yum, S. S., Hudson, J. G., and Xie, Y.: Comparisons of cloud microphysics with cloud condensation nuclei spectra over the summertime Southern Ocean, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 103, 16625–16636, https://doi.org/10.1029/98JD01513, 1998.

Zhou, J., Xu, X., Zhao, W., Fang, B., Liu, Q., Cai, Y., Zhang, W., Venables, D. S., and Chen, W.: Simultaneous measurements of the relative-humidity-dependent aerosol light extinction, scattering, absorption, and single-scattering albedo with a humidified cavity-enhanced albedometer, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 13, 2623–2634, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-13-2623-2020, 2020.

Zíková, N., Pokorná, P., Makeš, O., Sedlák, P., Pešice, P., and Ždímal, V.: Activation of atmospheric aerosols in fog and low clouds, Atmos. Environ., 230, 117490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117490, 2020.