the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Modeling daytime and nighttime secondary organic aerosol formation via multiphase reactions of biogenic hydrocarbons

Sanghee Han

The daytime oxidation of biogenic hydrocarbons is attributed to both OH radicals and O3, while nighttime chemistry is dominated by the reaction with O3 and NO3 radicals. Here, daytime and nighttime patterns of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) originating from biogenic hydrocarbons were predicted under varying environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, sunlight intensity, NOx levels, and seed conditions) by using the UNIfied Partitioning Aerosol phase Reaction (UNIPAR) model, which comprises multiphase gas–particle partitioning and in-particle chemistry. The products originating from the atmospheric oxidation of three different hydrocarbons (isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene) were predicted by using extended semi-explicit mechanisms for four major oxidants (OH, O3, NO3, and O(3P)) during day and night. The resulting oxygenated products were then classified into volatility–reactivity-based lumping species. The stoichiometric coefficients associated with lumping species were dynamically constructed under varying NOx levels, and they were applied to the UNIPAR SOA model. The predictability of the model was demonstrated by simulating chamber-generated SOA data under varying environments. For daytime SOA formation, both isoprene and α-pinene were dominated by the OH-radical-initiated oxidation showing a gradual increase in SOA yields with decreasing NOx levels. The nighttime isoprene SOA formation was processed mainly by the NO3-driven oxidation, yielding higher SOA mass than daytime at higher NOx level (isoprene NOx < 5 ppb C ppb−1). At a given amount of ozone, the oxidation to produce the nighttime α-pinene SOA gradually transited from the NO3-initiated reaction to ozonolysis as NOx levels decreased. Nighttime α-pinene SOA yields were also significantly higher than daytime SOA yields, although the nighttime α-pinene SOA yields gradually decreased with decreasing NOx levels. β-Caryophyllene, which rapidly produced SOA with high yields, showed a relatively small variation in SOA yields from changes in environmental conditions (i.e., NOx levels, seed conditions, and sunlight intensity), and its SOA formation was mainly attributed to ozonolysis day and night. The daytime SOA formation was generally more sensitive to the aqueous reactions than the nighttime SOA because the daytime chemistry produced more highly oxidized multifunctional products. The simulation of α-pinene SOA in the presence of gasoline fuel, which can compete with α-pinene for the reaction with OH radicals in typical urban air, suggested more growth of α-pinene SOA by the enhanced ozonolysis path. We concluded that the oxidation of the biogenic hydrocarbon with O3 or NO3 radicals is a source of the production of a sizable amount of nocturnal SOA, despite the low emission at night.

- Article

(2255 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1632 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Organic aerosol in the ambient air has been a factor impacting human health (Pye et al., 2022; Mauderly and Chow, 2008) and climate change (Tsigaridis and Kanakidou, 2018; Kanakidou et al., 2005). A large portion of organic aerosol, especially of the fine particulate matter, is secondary organic aerosol (SOA) produced from the oxidation process of hydrocarbons (HCs), emitted from both biogenic and anthropogenic sources (Hallquist et al., 2009; Jimenez et al., 2009; Guenther et al., 1995; Goldstein and Galbally, 2007; Sindelarova et al., 2014). These biogenic HCs contain olefinic (C=C) bonds that are highly reactive towards various oxidants (i.e., OH radicals, NO3 radicals, and O3) (Atkinson and Arey, 2003). Furthermore, the SOA from the oxidation of biogenic HCs is a considerable source of the global SOA budget (Kelly et al., 2018; Hodzic et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2017). For example, Kelly et al. (2018) reported that more than 50 % of the annual global SOA production rate (48.5–74.0 Tg SOA yr−1) is from monoterpenes (19.9 Tg SOA yr−1) and isoprene (4–19.6 Tg SOA yr−1).

In the daytime, a large amount of biogenic HC is oxidized mainly with OH radicals and O3 to form a considerable SOA burden (Zhang et al., 2018; Carlton et al., 2009; Sakulyanontvittaya et al., 2008; Barreira et al., 2021). The photochemical cycle of NOx coupled with the oxidation of biogenic HCs enhances the production of O3 and regenerates OH radicals, increasing the consumption of biogenic HCs and the formation of SOA. In nighttime, the oxidation of biogenic HCs is processed dominantly by O3 and NO3 radicals. In the presence of O3, NO is titrated to form NO2. The O3 generated in daytime is not rapidly consumed at nighttime and can further react with NO2 to form a NO3 radical that can also be sustained in nighttime. The oxidation pathways of biogenic HCs can change diurnally with different NOx levels and ultimately influence SOA formation. For example, the oxidation of isoprene with the NO3 radical can rapidly produce nitrate-containing products (up to 80 % of total gas products), resulting in an increase in the SOA formation (Kwok et al., 1996; Barnes et al., 1990; Perring et al., 2009; Brownwood et al., 2021). Numerous studies have also shown the important role of the NO3 radical in the production of SOA, suggesting the emission of NOx from human activities increases the biogenic SOA mass (Ng et al., 2008; Bonn and Moorgat, 2002; Jaoui et al., 2013; Rollins et al., 2012) at nighttime.

The biogenic SOA formation in current air quality models is predicted with the surrogate products originating from four major oxidants: OH radicals, NO3 radicals, O3, and O(3P). However, the gas-phase reactions cannot be constrained by a specific oxidation path due to the various cross reactions with major oxidants. For example, the first generation of oxidation products initiated by the ozone mechanism can also react with the OH radical. The product distribution originating from a specific oxidant can also be influenced by the NOx level and atmospheric aging. Hence, the systematic approach that considers oxidation paths of biogenic HCs in daytime and nighttime under varying environments is essential to better simulate the formation of biogenic SOA.

The product distributions associated with the oxidation paths of biogenic HCs can significantly influence heterogeneous reactions of organic species in the aerosol phase, which also increase SOA growth. Numerous studies have shown the importance of the aerosol-phase reaction, yielding the non-volatile species or oligomeric matter, of reactive organic species (i.e., aldehydes and epoxides) in the aerosol phase (Jang et al., 2002; Woo et al., 2013; Altieri et al., 2006; Ervens et al., 2004; Liggio et al., 2005). The typical SOA models that have been semi-empirically established by a relationship between the organic matter (OM) concentration and the SOA yields by using simple partitioning parameters for two (Odum et al., 1996) or more surrogate products (Donahue et al., 2006) include organic-phase oligomerization, but they do not fully treat the SOA formation via the aqueous reactions in the presence of inorganic salts.

The UNIfied Partitioning Aerosol-phase Reaction (UNIPAR) model has recently been developed to predict SOA formation via the multiphase reaction of HCs (Beardsley and Jang, 2016; Im et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2019). This model was demonstrated by simulating the SOA formation from various aromatic HCs (Im et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2019; Han and Jang, 2022), monoterpenes (Yu et al., 2021), and isoprene (Beardsley and Jang, 2016). In this study, the UNIPAR model has been extended to predict daytime and nighttime patterns of biogenic SOA formation. Lumping species and their stoichiometric coefficient and physicochemical parameters from the extended semi-explicit gas mechanisms were individually obtained from the four major oxidation pathways with OH radicals, O3, NO3 radicals, and O(3P). The potential SOA yields of biogenic HCs via four different oxidation paths were simulated by using the UNIPAR model and utilized to study daytime and nighttime patterns in biogenic SOA formation under varying NOx levels, temperature, and seed conditions. To mimic the nighttime α-pinene SOA formation under the polluted urban atmosphere, α-pinene SOA formation was also simulated in the presence of gasoline fuel.

The chamber experiments to produce SOA from the oxidation process of biogenic HCs were conducted in the University of Florida Atmospheric PHotochemical Outdoor Reactor (UF-APHOR) chamber located on the rooftop of Black Hall (29.64∘ N, −82.34∘ W) at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. The detailed configuration of the UF-APHOR and the experimental procedures were previously reported (Beardsley and Jang, 2016; Im et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2019). In brief, the UF-APHOR chamber is a dual chamber (52 m3 (east) + 52 m3 (west)) made with fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) Teflon film. Before the experiment, the chamber was cleaned by using a clean air generator for 2 d after the ventilation process. For daytime experiments, the injection was done before sunrise, and the experiments started at sunrise and were conducted for 10 to 12 h. NO was introduced into the chamber from the NO cylinder (2 %, air gas) prior to sunrise for daytime experiments. The NOx level is classified into high NOx level (HC NOx < 5.5 ppb C ppb−1) and the NOx level (HC NOx > 5.5 ppb C ppb−1) based on the initial concentrations of HC and NO. Inorganic seed aerosols (sulfuric acid, SA; wet ammonium sulfate, wet-AS; and dry ammonium sulfate, dry-AS) were injected into the chamber to evaluate the effects of wet inorganic seed on SOA formation. For nighttime experiments, the injection and experiments began after sunset to avoid photochemical reaction, and experiments were conducted for 3 to 5 h. O3 was injected first into the chamber by using the O3 generator (Jenesco Inc) followed by NO2 injection using the NO2 cylinder (2 %, air gas). Nighttime biogenic SOA formation was observed under three different NOx levels (i.e., O3 only, low NOx (HC NOx > 5.5 ppb C ppb−1), and high NOx (HC NOx < 5.5 ppb C ppb−1)). Three different biogenic HCs (isoprene (C5H8, 99 %, Aldrich), α-pinene (C10H16, 98 % Aldrich), and β-caryophyllene (C15H24, > 90 %, TCI)) were injected into the chamber. CCl4 was also introduced to the chamber to measure chamber dilution. Detailed information on the chamber experiments is summarized in Table 1.

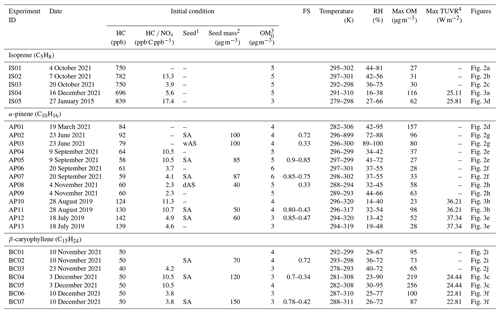

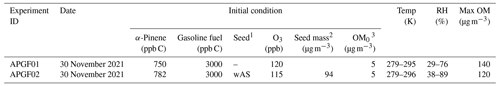

Table 1Experimental conditions for the oxidation of biogenic HCs in the UF-APHOR chamber.

1 NS, SA, wAS, and dAS indicate non-seeded, sulfuric acid seed, wet ammonium sulfate seed, and dry ammonium sulfate seed, respectively. 2 The seed mass is determined as a dry mass without water mass. 3 The pre-existing organic matter (OM0) is determined for the chamber air prior to the injection of inorganic seed and HC. 4 Maximum sunlight intensity is shown during the experiment measured by using the total ultraviolet radiometer (TUVR). For nighttime, the experiment was performed under the darkness without the sunlight.

The concentration of HCs and CCl4 was monitored using a gas chromatography–flame ionizer detector (Agilent, Model 7820A) (GC–FID). The HC concentration detected by GC–FID determined HC consumption in the chamber during the experiment. The concentration of CCl4 measured by GC–FID was monitored as a function of time to obtain the dilution factor of the chamber during the experiment. The concentration of O3 was monitored with a photometric ozone analyzer (Teledyne, Model 400E, and 2B Technologies, Model 106-L, M). NOx concentration was monitored by using a chemiluminescence NO–NO2 analyzer (Teledyne, Model 200E) and photometric NOx analyzer (2B Technologies, Model 405 nm). The inorganic ion (SO and NH) and organic carbon (OC) concentrations of aerosol were in situ monitored by the particle-into-liquid sampler (Applikon, ADI 2081), coupled with ion chromatography (Metrohm, 761Compact IC) (PILS–IC), and an OC EC carbon aerosol analyzer (Sunset Laboratory, Model 4), respectively. The scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS; TSI, Model 3080) integrated with a condensation nuclei counter (TSI, Model 3025A and Model 3022) was used to measure the particle volume concentration over the course of the experiment. An aerosol chemical speciation monitor (ACSM; Aerodyne Research Inc.) observed the composition (SO, NO, NH, and organic) of aerosol to compare with the data obtained from OC and PILS–IC. The relative humidity and temperature were monitored in the UF-APHOR and applied to the simulation, and the sunlight intensity was measured by a total ultraviolet radiometer (TUVR; EPLAB). Aerosol acidity (moles per liter of aerosol) was examined by colorimetry integrated in the reflectance UV–visible spectrometer (CRUV; Li and Jang, 2012; Jang et al., 2020). The details of the experimental conditions are summarized in Table 1.

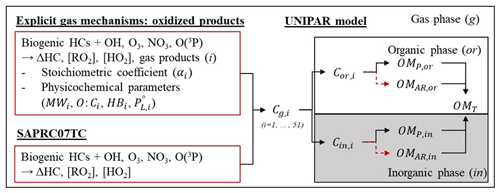

UNIPAR streamlines the gas oxidation integrated with gas mechanisms, multiphase partitioning, and aerosol-phase reactions in both organic and inorganic phases (Fig. 1). The oxidation products from each biogenic HC were predicted by using extended semi-explicit mechanisms for each oxidant (OH radicals, O3, NO3 radicals, and O(3P)). The simulated gas products were classified into the 51 lumping species (i) according to their volatility and reactivity in the aerosol phase. The UNIPAR model was simulated under the Dynamically Simple Model of Atmospheric Chemical Complexity (DSMACC) (Emmerson and Evans, 2009) integrated with the Kinetic PreProcessor (KPP) (Damian et al., 2002). The stoichiometric coefficient (αi) and physicochemical parameters of i are estimated by using the products predicted from extended semi-explicit mechanisms at a given oxidation path for each precursor. In the model, αi values are dynamically constructed with a mathematical equation as a function of NOx levels. The predetermined mathematical equation and physicochemical parameters for lumping groups are applicable to the conventional gas mechanisms. In order to support the atmospheric oxidation of biogenic HCs in complex ambient air, these model parameters were integrated with the HC consumption predicted by the Statewide Air Pollution Research Center (SAPRC07TC) (Carter, 2010) gas mechanisms and then applied to produce SOA mass. The total organic matter (OMT) is estimated by gas–particle partitioning (OMP) and heterogeneous reactions (OMAR) in both organic and inorganic phases. For α-pinene and β-caryophyllene, the SOA formation in the presence of salted aqueous solutions (i.e., sulfuric acid, SA; ammonium bisulfate, AHS; and ammonium sulfate, AS) was simulated under the assumption of the liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) between the organic and inorganic phase. In the case of isoprene, the production of single homogeneous mixed-phase SOA has been reported in the presence of inorganic seed (Beardsley and Jang, 2016; Carlton et al., 2009). Thus, the isoprene SOA formation in the presence of inorganic aerosol was excluded. The details of the UNIPAR model are described in the following sections.

Figure 1The model structure of the UNIPAR model coupled with the SAPRC07TC gas mechanism with model parameters originated from the explicit gas mechanisms. The lumping species and their model parameters were estimated by simulating the explicit gas mechanism and applied to the UNIPAR model simulation. Cg,i, Cor,i, and Cin,i are the concentration of lumping species (i) in the gas phase (g), organic phase (or), and inorganic phase (in). OMp,or and OMp,in are the SOA mass generated via gas–particle partitioning in organic (or) and inorganic (in), respectively. OMAR,or and OMAR,in are the SOA mass generated via in-particle chemistry in or and in, respectively.

3.1 Generation of lumping species from the extended semi-explicit gas mechanisms

The UNIPAR model utilizes the stoichiometric coefficient (αi) array and physicochemical parameters (, MWi, O : Ci, and HBi) of the i, which are determined by the explicitly predicted gas products. The gas-phase oxidation of three biogenic HCs (isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene) of this study was explicitly processed by using the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM v3.3.1) (Saunders et al., 2003; Jenkin et al., 2012, 2015) to generate lumping species and their model parameters. Additionally, the recently identified oxidation mechanisms that can yield low-volatility products were also integrated with MCM. For example, the peroxy radical autoxidation mechanism (PRAM) (Roldin et al., 2019) that forms the highly oxygenated organic molecule (HOM) (Molteni et al., 2019) and the accretion reaction to form ROOR from the RO2 (Bates et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021) were added (Tables S1–S3 in the Supplement). Furthermore, the oxidation process of biogenic HCs by O(3P) (Paulson et al., 1992; Alvarado et al., 1998) was included to synchronize with the oxidation path in SAPRC07TC. The additional mechanisms are shown in Sect. S1.2 in the Supplement. The oxidation-path-dependent lumping parameters were generated by individually processing the reaction of biogenic HCs with four major oxidants (OH radicals, O3, NO3 radicals, and O(3P)). After a biogenic HC is oxidized with individual oxidants, the further oxidation of the first-generation product was allowed to react with any oxidant. For instance, the first-generation ozonolysis products of biogenic HC can react with OH radicals or NO3 radicals.

For each oxidation path, the resulting oxygenated products from the extended semi-explicit gas mechanism were classified into eight levels of vapor pressure () (1–8: 10−8, 10−6, 10−5, 10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, and 1 mm Hg) and six levels of the aerosol–phase reactivity scale (Ri) (very fast, VF; fast, F; medium, M; slow, S; partitioning only, P; and multi-alcohol, MA), as well as three additional reactive species (glyoxal, methylglyoxal, and epoxydiols) (Yu et al., 2022). The physicochemical parameters (, MWi, O : Ci, and HBi) of i are determined based on the group contribution and unified into one array for each HC. Details about the model parameters and lumping structures are given in Sect. S7.

3.2 SOA growth via gas–particle partitioning

In this model, the gas–particle partitioning of oxidation products are assumed to be an equilibrium partitioning process based on the absorptive partitioning theory (Pankow, 1994). It assumes that the gas–particle partitioning instantaneously reaches equilibrium to distribute the gas products into the gas (Cg,i), organic (Cor,i), and inorganic phases (Cin,i). The partitioning coefficient of i into the organic phase (Kor,i, m3 µg−1) is determined by the traditional absorptive partitioning theory (Pankow, 1994) as follows:

where MWor (g mol−1) is the molecular weight of OMT, R (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) is the ideal gas constant, and T (K) is the temperature. γor,i is the activity coefficient of i in the organic phase and assumed to be unity. The partitioning coefficient of i into the inorganic phase (Kin,i, m3 µg−1) is also calculated according to the absorptive partitioning theory:

where MWin (g mol−1) is the averaged molecular weight of inorganic aerosol, and γin,i is the activity coefficient of i in the inorganic phase. Unlike γor,i, γin,i is semiempirically estimated with a polynomial equation, determined by fitting the γin,i estimated by the aerosol inorganic–organic mixture functional group activity coefficient (AIOMFAC) (Zuend et al., 2011) as

where RH and FS are relative humidity (%) and fractional sulfate. Fractional sulfate (FS) is the concentration ratio of total sulfate to the sum of total sulfate and ammonium ions in aerosol (Zhou et al., 2019). FS, introduced to determine aerosol acidity, ranges from 0.33 to 1 for ammonium sulfate to sulfuric acid, respectively.

The gas–organic partitioning is governed by Raoult's law, assuming that the saturation vapor pressure of the species is dependent on the mole fraction of the species in the solution. To consider the oligomerization of organic species in total concentration , OMP is recalculated after OMAR integration with the partitioning model (Schell et al., 2001), which is reconstructed by including OMAR (Cao and Jang, 2010). OMP is calculated by the Newton–Raphson method (Press et al., 1992) from CT,i using a mass balance equation:

where OM0 (g m−3) is the concentration of pre-existing OM, and MW0 (g mol−1) is the molecular weight of pre-existing OM. and MWoli,i (g mol−1) are the effective saturation concentration of i and the molecular weight of the dimer (i), respectively.

3.3 SOA formation via aerosol-phase reaction

OMAR, which is generated via aerosol-phase reaction in both organic and inorganic phases, is estimated as a second-order reaction product from condensed organics based on the assumption of a self-dimerization reaction of organic compounds in media (Im et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2019; Odian, 2004):

where and are the concentration of i in the organic and inorganic aerosol phase (mol L−1), respectively. The reaction rate constants in the aqueous phase (kAC,i, L mol−1 s−1) and organic phase (ko,i) are determined (Jang et al., 2005, 2006) as follows:

whereby kAC,i is semiempirically determined from Ri, the protonation equilibrium constant (), excess acidity (X) (Cox and Yates, 1979; Jang et al., 2006), water activity (aw), and proton concentration [H+] (Im et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2019); ko,i is determined by extrapolating kAC,i to the neutral condition in the absence of a salted aqueous solution to process oligomerization in the organic phase and is calculated without X, aw, and [H+] terms because aw, [H+], and X converged to zero in the absence of wet inorganic seed.

3.4 Integration of UNIPAR with SAPRC

The UNIPAR model that equips the pre-determined mathematical equations for αi array and physicochemical parameters of the lumping species originating from explicit products was coupled with SAPRC07TC (Carter, 2010). In this study, the consumption of biogenic HCs was obtained from SAPRC07TC simulation and applied to calculate the gas concentration of 51 lumping species and following SOA formation by utilizing the model parameters originating from the extended semi-explicit mechanisms. The reaction rate constant of β-caryophyllene in SAPRC07TC was adjusted based on that from the MCM mechanism (Jenkin et al., 2012). The resulting gas mechanism of biogenic HCs in SAPRC07TC was summarized in Table S4. For the SOA simulation with NO3 radicals in the presence of wet inorganic seed aerosol, the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 was included in gas mechanisms. N2O5 forms via the equilibrium reaction of a NO3 radical and NO2 in the gas phase but is rapidly hydrolyzed by the interfacial process on the surface of salted aqueous aerosol to form nitric acid (Galib and Limmer, 2021). The hydrolysis rate constant of N2O5 has been reported to be in the range of 10−7 to 100 s−1 (Wagner et al., 2013; Wood et al., 2005), and thus, the hydrolysis rate constant of N2O5 was set to 10−2 s−1in this study. The water content in isoprene SOA, which is very hydrophilic, was estimated to be of the hygroscopicity of ammonium sulfate (Beardsley and Jang, 2016).

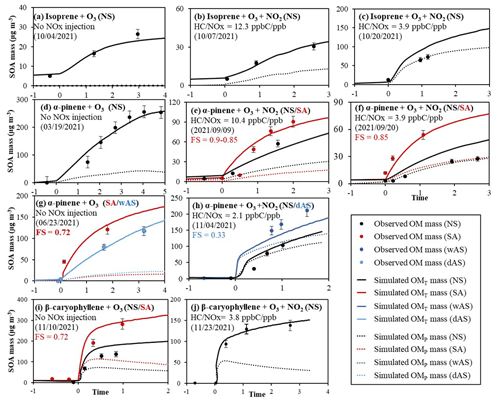

4.1 Simulation of chamber data with the UNIPAR model

The predictability of the UNIPAR model was demonstrated by simulating SOA data obtained from the oxidation of three biogenic HCs (isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene) in the UF-APHOR chamber under the various environmental conditions, such as NOx level, inorganic seed conditions, and temperature during both day and night (Table 1). Figure 2 shows the total simulated SOA mass (OMT, solid line) and OMP (dotted line) by the UNIPAR. The predicted SOA mass approached with four oxidation paths accords well with the observed SOA mass (symbol). For the ozonolysis of all three biogenic HCs of this study, OMP attributes more to SOA formation in the presence of NOx (Fig. 2b, c, e, f, h, and j) than in the absence of NOx (Fig. 2a, d, g, and i). This suggests the importance of NO3 radicals at nighttime. The SOA formation increased with wet inorganic seed due to aqueous-phase reactions of reactive organic species, rendering the reduction in OMP, as seen in Fig. 2e and f. In the same manner, SOA formation with acidic seed increased, but the fraction of OMP of total SOA mass decreased (Fig. 2g). However, the impact of inorganic seed on nocturnal SOA formation can be insignificant in the presence of NOx because N2O5 undergoes heterogeneous hydrolysis reaction on the surface of wet aerosol particles to form nitric acid (HNO3) (Brown et al., 2006; Hu and Abbatt, 1997; Galib and Limmer, 2021).

Figure 2Observed (symbols) and simulated SOA mass (line) for the ozonolysis of isoprene (a–c), α-pinene (d–h), and β-caryophyllene (i, j) under different seed conditions and NOx levels. SOA mass concentrations are corrected for the particle loss to the chamber wall. The simulated OMT (solid line) and OMP (dotted line) are also illustrated. The error (10 %) associated with SOA mass was estimated with the instrumental uncertainty. NS, SA, wAS, and dAS indicate non-seeded, sulfuric-acid-seeded, wet-ammonium-sulfate-seeded, and dry-ammonium-sulfate-seeded experiments, respectively.

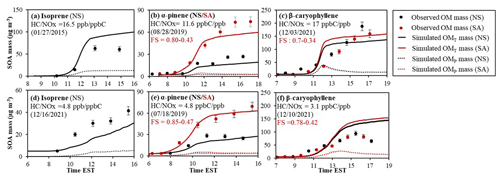

As seen in Fig. 3, the daytime simulation approached by the four oxidation paths with the UNIPAR model also agreed well with the SOA mass generated under various experimental conditions. For both isoprene SOA (Fig. 3a vs. d) and β-caryophyllene SOA (Fig. 3c vs. f), a clear NOx effect appeared for measurement and simulation performed under similar experimental conditions during daytime, showing higher SOA mass with greater HC NOx level (lower NOx), as previously reported in many studies (Carlton et al., 2009; Tasoglou and Pandis, 2015). The impact of acidic seed on α-pinene SOA formation (Fig. 3b and e) was also simulated with the model, as reported in other studies (Yu et al., 2021; Han et al., 2016; Kristensen et al., 2014). However, β-caryophyllene SOA was relatively insensitive to the aerosol acidity (Fig. 3c and f), which disagreed with the previous observations (Chan et al., 2011; Offenberg et al., 2009). In Fig. 3f, the difference in OMP between NS and SA conditions was not evident. The SOA yield from β-caryophyllene oxidation is very high, even in the absence of the salted aqueous phase. Thus, the impact of aqueous reactions on β-caryophyllene can be less dramatic than that of α-pinene.

Figure 3Observed (point) and simulated SOA mass (line) for the photooxidation of isoprene (a, d), α-pinene (b, e), and β-caryophyllene (c, f) under different seed conditions and NOx levels. SOA mass concentrations are corrected for the particle loss to the chamber wall. The simulated OMT (solid line) and OMP (dotted line) are also illustrated. The error (10 %) associated with SOA mass was estimated with the instrumental uncertainty. NS and SA indicate non-seeded and sulfuric-acid-seeded experiments, respectively.

4.2 Evaluation of biogenic SOA potential from major oxidation paths

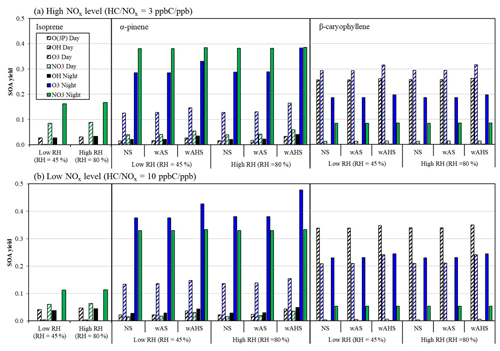

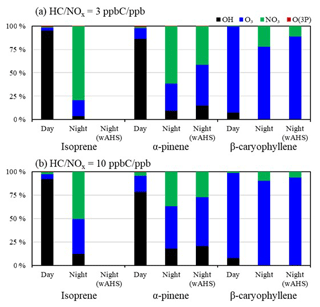

The atmospheric process of biogenic HCs is complex because of their multi-generation oxidations by the combination of various oxidation paths. To investigate the impact of product distributions of each oxidation path on SOA growth during day and night, SOA yields are simulated under the constrained oxidation path with a fixed amount of HC consumption, as seen in Fig. 4. SOA yields are simulated under varying environmental conditions, including two different NOx levels (Fig. 4a: high NOx; Fig. 4b: low NOx) and three different seed conditions (no seed; wAS; and wet ammonium bisulfate, wAHS). To investigate the impact of aerosol acidity, the SOA formation is simulated in the presence of wAHS seed at pHs −1.5 and 0, corresponding to RHs of 45 % and 80 %, respectively. The reported acidity of the ambient aerosol is in the range of pH −1 to 5 (Pye et al., 2020). Overall, biogenic SOA formation from the O(3P) reaction path is negligible.

Figure 4The simulated potential SOA yield from each oxidation path from the given HC consumption at a (a) high NOx level (HC NOx = 3 ppb C ppb−1) and (b) low NOx level (HC NOx = 10 ppb C ppb−1). The consumptions of biogenic HCs are set to 50 ppb (138 µg m−3) for isoprene, 30 ppb (162 µg m−3) for α-pinene, and 20 ppb (167 µg m−3) for β-caryophyllene. The SOA formation was simulated at 298 K under two different RHs (45 % and 80 %) with 10 µg m−3 of OM0. For the α-pinene and β-caryophyllene, the SOA formed under three different seed conditions (NS, wAS, wAHS). For the inorganic seeded simulation, the seed concentration is 20 µg m−3 (dry mass).

For isoprene, the efficient pathways to form SOA are the NO3-initiated oxidation (6 %–17 %) and OH-initiated oxidation (3 %–4 %) during both day and night under given conditions of Fig. 4. However, the SOA yield from O3 is trivial, at ∼ 0.4 %. This tendency accords with the previous studies (Carlton et al., 2009; Kleindienst et al., 2007; Czoschke et al., 2003) in that isoprene SOA formation is more with the OH-initiated oxidation than the ozonolysis. Evidently, the SOA formed via ozonolysis in the absence of an OH scavenger was greater than that in the presence of the scavenger in the laboratory work (Kleindienst et al., 2007), suggesting that a sizable fraction of the isoprene aerosol is produced via the OH oxidation path.

α-Pinene SOA yields are high with ozonolysis- and NO3-initiated oxidation in both daytime and nighttime. By including an autoxidation mechanism of ozonolysis products (Roldin et al., 2019; Crounse et al., 2013; Bianchi et al., 2019) in the gas mechanism, low-volatility products increase α-pinene SOA yield. The importance of autoxidation products for terpene SOA formation has been demonstrated in a previous study by Yu et al. (2021) for daytime chemistry. At night, the contribution of autoxidation to ozonolysis SOA depends on the concentration of α-pinene. For example, the attribution of autoxidation to SOA mass in experiment AP01 (Table 1) was nearly 15 %, but it can increase due to gas–particle partitioning of non-autoxidation products onto SOA-mass-originating autoxidation products. The addition of NO3 to the alkene double bond of α-pinene is followed by the addition of an oxygen molecule to form an alkylperoxy radical that can also lead to low-volatility peroxide accretion products (ROOR) (Hasan et al., 2021; Bates et al., 2022). The α-pinene ozonolysis SOA yield is insensitive to humidity even in the presence of hygroscopic, acidic AHS seed. The UNIPAR model estimates the activity coefficient of lumping species in the inorganic salted aqueous phase by using lumping species' physicochemical parameters. Unlike isoprene (Beardsley and Jang, 2016) or aromatic products (Han and Jang, 2022; Im et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2019), α-pinene gas products are relatively hydrophobic, and thus, their solubility is low in the aqueous phase with their large activity coefficients. Evidently, α-pinene SOA yields a lower O : C ratio (∼ 0.56) than isoprene SOA (∼ 1.1) in the model.

β-Caryophyllene shows higher SOA potential in daytime than in nighttime, while both isoprene and α-pinene lessen SOA yields in daytime due to photolysis of oxidation products. In the case of β-caryophyllene, even after the photodegradation the product, volatility is still low enough to significantly partition to the aerosol phase and heterogeneously form SOA. Evidently, our simulation suggested that the averaged molecular weight of β-caryophyllene oxidation products in highly reactive groups (VF or F) is 183.01 g mol−1, while that from isoprene and α-pinene is 116.65 and 143.29 g mol−1, respectively. Under darkness, the β-caryophyllene SOA formation potential is the highest with ozonolysis, followed by the NO3-initiated oxidation. Under given simulation conditions in Fig. 4, the β-caryophyllene SOA yield ranges from 26 % to 35 % for the OH-initiated oxidation and from 21 % to 32 % for ozonolysis. The SOA yields from the reaction of β-caryophyllene with OH radicals and O3 agree with those in other laboratory studies (i.e., SOA yields with OH: 17 %–68 %; those with O3: 5 %–46 %) (Chan et al., 2011; Jaoui et al., 2013; Tasoglou and Pandis, 2015).

Figure 4 also shows the effect of NOx on SOA potential by each oxidation path under various conditions (RH and seed). Overall, the NO3-initiated SOA yield is positively correlated to the NOx level because the RO2 that forms via the reaction of biogenic HC with a NO3 radical followed by the addition of an oxygen molecule can react with HO2 radicals to form organic hydroperoxide, which yields little SOA mass (Bates et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2008). For all three biogenic HCs, the OH-initiated SOA yields are negatively correlated to the NOx level. Under our simulation condition, the low NOx level (Fig. 4b) yields on average 1.2–1.5 times higher SOA mass than the high NOx level (Fig. 4a). For the reaction of OH radicals with α-pinene or β-caryophyllene, the low NOx level increases reactive organic products (i.e., aldehydes), and thus, SOA grows rapidly via heterogeneous reactions. The OH-initiated isoprene SOA yields increase with reduced NOx level because of the formation of epoxy-diol (Kroll et al., 2006). For the ozonolysis path, α-pinene SOA yields decrease by 80 %–93 % by increasing the NOx level in this study by lowering the formation of low-volatility products. For example, the autoxidation path of the α-pinene ozonolysis product can be suppressed under the high NOx level (Bianchi et al., 2019). For β-caryophyllene, the nighttime SOA formation from ozonolysis also increases with reduced NOx level because the internal rearrangement of ozonolysis products to form the secondary ozonide competes with the reaction of these ozonolysis products with NO or NO2 (Jenkin et al., 2012). The further oxidation of the secondary ozonide products yields low-volatility products. However, the ozonolysis β-caryophyllene SOA under sunlight increases by a factor of up to 1.4 by increasing the NOx level in Fig. 4. This tendency is possibly due to the further reaction of the ozonolysis products, which contain an alkene double bond and an aldehyde group and can react with a NO3 radical to form high-carbon peroxy radicals. Furthermore, the resulting peroxy radicals can produce a variety of organic products that form SOA via heterogeneous reactions and the low-volatility products (Jenkin et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011). Figure S3 illustrates the stoichiometric coefficients of the two lumping species (low-volatility species in group 2S and the medium-reactivity species (one aldehyde group) in group 4M), which increase with increased NOx and can significantly contribute to SOA mass. These two species originate from the reaction of a nitrate radical with the ozonolysis products.

Regardless of HCs and oxidation pathways, the impact of neutral seed (wAS) on biogenic SOA formation is insignificant. The impact of the acidic seed (wAHS) on α-pinene SOA formation is various depending upon the oxidation path. For daytime SOA, the significant impact of acidic seed on SOA formation is observed as previously reported (Yu et al., 2021; Han et al., 2016). For nighttime, no significant impact of acid-catalyzed reactions on the α-pinene SOA originating from the NO3-initiated pathway appears because the SOA forms from low-volatility ROOR products that are insensitive to aerosol acidity (Boyd et al., 2017). In Fig. 4, nocturnal SOA formation from the α-pinene ozonolysis increases by including acidic seed (wAHS). Thus, the small increase in chamber-generated SOA formation (Fig. 2e and f) by inorganic seed is mainly caused by the aqueous-phase reaction of the ozonolysis products. For β-caryophyllene, overall, the increase in SOA yields due to aqueous-phase reactions is not significant for all oxidation pathways. Only a small increase in the β-caryophyllene SOA yield in the presence of acidic seed (wAHS) appears for the O3-initiated oxidation path at nighttime and daytime. The large molecules originating from β-caryophyllene oxidation might have a poor solubility in the aqueous phase, weakening the impact of aerosol acidity on OMAR. For example, the simulated O : C of β-caryophyllene SOA is estimated as ∼ 0.27 under the chamber conditions in Fig. 2i.

The chamber-generated SOA mass is influenced by the deposition of organic vapor to the chamber wall. The simulation of SOA yields in Fig. 4 is performed with the model parameters obtained in the presence of the wall effects. To investigate the SOA formation in the ambient air, the wall-free SOA model parameter has recently been derived by Han and Jang (2022). Figure S2 illustrates the SOA yields predicted in the absence of the deposition of organic vapor to the chamber wall. Overall, the effect of acidic seed on SOA formation is reduced by the correction of model parameters for the wall artifact. The impact of gas–wall deposition on SOA formation is higher in the absence of inorganic seed than that in the presence of inorganic seed (Han and Jang, 2022; Krechmer et al., 2020). α-Pinene SOA is more influenced by gas–wall partitioning than isoprene or β-caryophyllene SOA, especially for the OH radical and NO3 radical oxidation paths.

4.3 Sensitivity of biogenic SOA formation to major variables and associated uncertainty

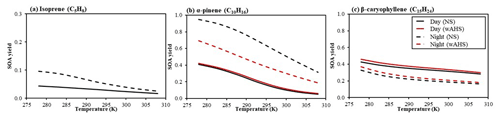

The sensitivity of three biogenic SOA yields to important environmental variables is demonstrated in Fig. 5. SOA yields in Fig. 5 were simulated for (a) isoprene, (b) α-pinene, and (c) β-caryophyllene in both daytime (solid line) and nighttime (dashed line) under the various temperatures and seeds (NS and wAHS), ranging from 278 to 308 K, under the given reference condition. For the sensitivity test, the bias from gas–wall partitioning is corrected in this simulation by the amended model parameter (Han and Jang, 2022). The contribution of each oxidation pathway to the consumption of biogenic HC is illustrated in Fig. 7a. For the daytime, the SOA formation is simulated under the reference sunlight intensity (Fig. S1), measured on 19 June 2015 at the UF-APHOR. The simulation is performed for the urban atmosphere, where the NOx level is high (HC NOx = 3 ppb C ppb−1) because the concentration of O3 and NO3 radicals is relatively high in the polluted atmosphere.

Figure 5The biogenic SOA yield from (a) isoprene, (b) α-pinene, and (c) β-caryophyllene in both daytime (solid line) and nighttime (dashed line) under the various temperatures, ranging from 278 to 308 K. The level was set to 3 ppb C ppb−1. The SOA formation was simulated with 10 µg m−3 of OM0 at the 50 % of RH with the fixed initial concentration of isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene at 50, 30, and 24 ppb, respectively. The sensitivity of SOA mass to temperature is investigated by simulating α-pinene and β-caryophyllene under NS and wAHS (20 µg m−3) conditions. The daytime SOA formation was simulated under the reference sunlight intensity (Fig. S1), which was measured on 19 June 2015 at the UF-APHOR. For the nighttime simulation, the initial O3 concentration was set to 30 ppb. The wall-free model parameters were applied to simulate SOA formation (Han and Jang, 2022).

Figure 5 shows that isoprene and α-pinene produce more SOA mass by nighttime chemistry than daytime chemistry. SOA yields are influenced by hydrocarbon consumption by each oxidation path (Fig. 7) and the SOA potential at a given oxidation path (Fig. S2) as discussed in Sect. 4.2. Isoprene and α-pinene at night are mainly consumed by both NO3 radicals and O3, while in daytime they can be oxidized mainly by the OH radical. At night, NO3 radicals can react with NO to form NO2, but NO3 radicals can be regenerated via the reaction of NO2 and O3. In daytime, the role of NO3 in SOA formation can be minimal owing to its rapid photolysis (e.g., lifetime = 5 s) (Magnotta and Johnston, 1980). For β-caryophyllene, the majority of HC is consumed by O3 during both day and night due to its fast ozonolysis rate constant. The daytime SOA yield (Fig. S2) from the β-caryophyllene ozonolysis and OH-initiated oxidation is similar to or greater than that at night due to the formation of reactive products for oligomerization during multi-generation photochemical oxidation as discussed in Sect. 4.2.

In the absence of the inorganic seed, the nighttime SOA from all three HCs is more sensitive to the temperature than that produced in daytime. At nighttime, the biogenic HCs, primarily consumed by O3 and NO3 radicals, produce the semi-volatiles that form SOA dominantly by the partitioning process. The products formed via the photooxidation in daytime are multi-functional and reactive for aerosol-phase reactions and thus less sensitive to temperature.

The daytime α-pinene SOA formation is enhanced by the acid-catalyzed reaction by a factor of up to 1.2 (Fig. 5b). However, the nighttime α-pinene SOA mass decreases by introducing inorganic seeds due to the decay of the NO3 radicals through the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5, which thermodynamically forms NO3 radicals. The reduction in NO3 radicals results in less contribution of the NO3 path that can lead to a high-yield SOA formation (Fig. S2a). In both nighttime and daytime, β-caryophyllene SOA mass increases by a factor of up to 1.1 by aqueous-phase reactions. The impact of wet seed on isoprene SOA is not discussed in this study because the mixing state of isoprene products and wet-salt aerosol is not governed by LLPS. Studies have shown that the impact of aqueous-reaction isoprene SOA is greater than α-pinene (Beardsley and Jang, 2016; Carlton et al., 2009).

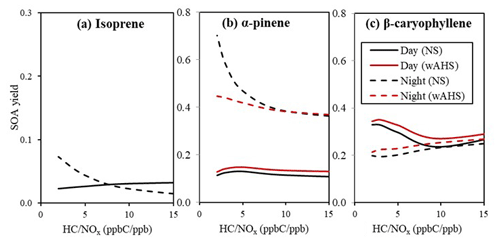

Figure 6 illustrates the sensitivity of SOA yields to the NOx level under two different seed conditions (NS and wAHS) under a given reference condition. The simulations are performed in the absence of the gas–wall partitioning (Han and Jang, 2022) with the same given initial concentration of isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene, as shown in Fig. 5. Despite a large increase in α-pinene SOA potential due to the gas–wall loss correction (Fig. 4 vs. Fig. S2), the highest yield in daytime SOA appears with β-caryophyllene, followed by α-pinene and isoprene. In nighttime, the simulated α-pinene SOA yield is higher than the β-caryophyllene SOA under the high-NOx condition due to the high α-pinene SOA potential from the NO3-initiated oxidation path. For α-pinene and isoprene, daytime SOA yields gradually decrease with increasing NOx, but nighttime SOA yields drastically increase in the high-NOx region. In daytime, the high NOx level increases the reactions of NO with RO2, leading to relatively volatile gas products lowering SOA yields (Yu et al., 2021; Carlton et al., 2009; Hallquist et al., 2009). At night, as seen in Fig. 7, the high-yield NO3-initiated path contributes more to the high NOx level. The NOx effects on nighttime biogenic SOA formation in the presence of inorganic seed are smaller than those in daytime due to the removal process of NO3 radicals via the hydrolysis of N2O5. For β-caryophyllene, the NOx effects on SOA yield show the opposite trend to α-pinene and isoprene SOA. The daytime β-caryophyllene SOA yields from ozonolysis decrease with reduced NOx level. Figure 7 suggests that the β-caryophyllene is mainly consumed by the O3-initiated path, and thus the β-caryophyllene SOA yield in daytime changes with NOx level (Fig. S2) due to the NOx dependency of ozonolysis product distributions, as discussed in Sect. 4.2.

Figure 6The biogenic SOA yield from (a) isoprene, (b) α-pinene, and (c) β-caryophyllene in both daytime (solid line) and nighttime (dashed line) under the various NOx levels. The RH and temperature were set to 50 % and 298 K, respectively. The SOA formation was simulated with 10 µg m−3 of OM0 with fixed initial concentrations of isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene of 50, 30, and 24 ppb, respectively. The dry mass of wAHS is set to 20 µg m−3. The daytime simulation is performed under the reference sunlight intensity (Fig. S1), which was measured on 19 June 2015 at the UF-APHOR. For the nighttime simulation, initial O3 concentration was set to 30 ppb. The wall-free model parameters were applied to simulate SOA formation (Han and Jang, 2022).

Figure 7The contribution of each oxidation path to the consumption of isoprene, α-pinene, and β-caryophyllene under the given condition under three different NOx levels (a HC NOx = 3 ppb C ppb−1 and (b) HC NOx = 10 ppb C ppb−1). The gas oxidation in daytime was simulated under the reference sunlight intensity, which was measured on 19 June 2015 (Fig. S1).

For the chamber study, concentrations of HC and NOx are generally higher than those in ambient air due to the detection limit of analytical instruments. Additionally, the chamber-generated SOA data can be influenced by vapor–wall deposition and the particle–wall loss. Figure S4 illustrates the influence of the initial concentration of biogenic HCs on SOA formation at a given NOx level (high-NOx condition). Regardless of initial HC concentrations, the sensitivity of SOA yields to different light conditions (day vs. night) or seed conditions (non-seed vs. wAHS) is consistent at a given biogenic hydrocarbon.

The prediction of SOA mass is influenced by two major processes: multiphase partitioning and heterogeneous reactions. Therefore, the model uncertainty test was performed for PL and in-particle reactions associated with ko, and kAC in the absence of chamber wall bias. The uncertainty in SOA mass in Fig. S5 is performed by increasing (decreasing) PL, ko, and kAC by a factor of 1.5 (0.5) at the high NOx level (HC NOx = 3 ppb C ppb−1) with 10 µg m−3 of OM0. The daytime SOA mass is simulated with the sunlight profile on 19 June 2015 near summer solstice (Fig. S1). Temperature and RH are set to 298 K and 50 %, respectively. The amount of both wAS and wAHS is fixed at 20 µg m−3 (dry mass). In the model, PL was determined based on the group contribution (Stein and Brown, 1994), with a reported error of a factor of 1.45 (Zhao et al., 1999); kAC was semi-empirically determined by correlating model compound data with the [H+] and liquid water contents and Ri (Eq. 7); ko was obtained by extending the kAC calculation to the neutral condition in the absence of a salted aqueous solution to process oligomerization in organic phase by eliminating X, aw, and [H+] terms (Eq. 8). Among the reaction systems in Fig. S5, α-pinene daytime SOA formation is the most responsive to the change in the three model parameters. PL is more influential in all three biogenic SOA formations than ko and kAC under the given simulation condition.

4.4 Nocturnal biogenic SOA formation in the presence of gasoline

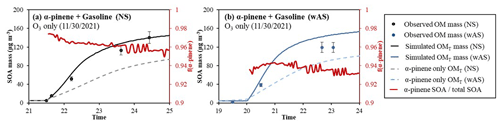

To investigate the influence of anthropogenic HC on the terpene SOA formation at night, 75 ppb α-pinene was oxidized with 120 ppb O3 in the presence of 3000 ppb C US commercial gasoline fuel (octane number of 87). The composition of gasoline fuel was analyzed by using GC–FID. Aromatic compounds made up around 30 % of gasoline fuel. The details of the experimental conditions are summarized in Table 2. Figure 8 illustrates the UNIPAR-simulated SOA mass (OMT, solid line) and the observed chamber-generated SOA mass (symbol). The aromatic HCs of gasoline fuel can be oxidized with the OH radicals, which are produced as a by-product from the ozonolysis of α-pinene (Finlayson-Pitts and Pitts, 1999). The gasoline SOA was simulated by utilizing the SOA model parameters from a previous study (Han and Jang, 2022). The simulation suggests that the SOA formation in the α-pinene and gasoline cocktail mainly originates from α-pinene oxidation products. The α-pinene SOA (red line) contributes 95 % to 98 % of the total SOA in the absence of inorganic seed (Fig. 8a), and it slightly decreases to 93 %–94 % in the presence of wet-AS because the gasoline aromatic oxidation products are highly reactive in the aqueous phase (Han and Jang, 2022). The simulated α-pinene SOA mass in the presence of gasoline fuel is also compared to that in the absence of gasoline in Fig. 8. Interestingly, the SOA formation in the presence of gasoline is elevated by 30 % compared to that in its absence. Under the ozone excess condition of this study, the oxidation of α-pinene is mainly dominated by ozonolysis in the presence of gasoline because gasoline competes with α-pinene to react with OH radicals (Fig. S7). As seen in Fig. 4, α-pinene ozonolysis is capable of yielding higher SOA mass than the α-pinene OH reaction.

Table 2Experimental conditions for the oxidation of α-pinene with gasoline fuel in the UF-APHOR chamber.

1 Wet ammonium sulfate seed is indicated by wAS. 2 The seed mass is determined as a dry mass, without water mass. 3 The pre-existing organic matter (OM0) is determined for the chamber air prior to the injection of inorganic seed and HC.

Figure 8Observed (symbol) and simulated SOA mass (line) for the ozonolysis of α-pinene in the presence of gasoline fuel (a) without and (b) with wet-AS seed. SOA mass concentrations are corrected for the particle loss to the chamber wall. The simulated OMT (solid line) in the presence of gasoline fuel and that in the absence of gasoline fuel (dashed line) are also illustrated. The dashed lines denote the simulated SOA mass in the absence of gasoline fuel under the same experimental conditions. The fractions of α-pinene SOA to total SOA (f(α-pinene)) are illustrated by red lines. The error (10 %) associated with SOA mass was estimated with the instrumental uncertainty.

The impact of anthropogenic hydrocarbons (gasoline) on α-pinene SOA is also demonstrated for different NOx levels and seed conditions without the chamber wall bias in Fig. S6. In the absence of inorganic seed, the simulation shows higher SOA yields with greater NO3 contribution at higher NOx. In the presence of inorganic seed, the contribution of NO3 to SOA formation decreases due to the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5, which forms the NO3 radicals, as discussed in Sect. 4.3. The effects of gasoline on total SOA formation decrease with increased NOx level because less ozonolysis results in less production of OH radicals. In addition, the gasoline SOA yield is generally smaller at higher NOx levels (Han and Jang, 2022).

In this study, the biogenic SOA produced from the reaction of isoprene, α-pinene, or β-caryophyllene with four major atmospheric oxidants (OH radicals, O3, NO3 radicals, and O(3P)) was simulated with the UNIPAR model and applied to interpretation of their diurnal pattern. Overall, isoprene and α-pinene SOA yields in daytime increased by decreasing the NOx level, but they showed the opposite tendency at night (Fig. 6). This trend accords with the previous laboratory studies and field observations (Rollins et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2021; Carlton et al., 2009; Hallquist et al., 2009; Fry et al., 2018). As seen in Fig. 7, the NO3 radical significantly contributed to the biogenic HC consumption at night, although its contribution can be smaller in the presence of wet inorganic aerosol. Field observations also show a considerable contribution of NO3 radicals to biogenic HC oxidation at night, up to 58 % of the total oxidation paths (Ng et al., 2017; Edwards et al., 2017).

The NOx emission from anthropogenic sources has gradually decreased, and the nighttime oxidation path in the southeast US is in transition from NOx dominance to O3 dominance (Edwards et al., 2017) due to the reduction in the NOx emission (Russell et al., 2012). The fate of SOA formation under the reduction in the NOx emission is, however, complex due to several reasons. Under the urban set, the biogenic HCs are oxidized in the presence of the complex cocktail of anthropogenic pollutants (i.e., aromatic HCs, SO2, and NOx). As discussed in Sect. 4.4, the reduction in NOx can lessen biogenic SOA mass at night (Figs. 4 and 6), although it increases aromatic SOA originating from the oxidation with an OH radical. In daytime, the reduction in NOx in urban air increases biogenic SOA burdens. However, NO2 can react with OH radicals at high NOx levels to form HNO3, which is semi-volatile and can condense onto the preexisting particles at the low temperature (Wang et al., 2020), increasing aqueous reactions of organics in hygroscopic inorganic aerosol. In rural environments where the NOx level is low, the reduction in NOx generally increases biogenic SOA formation in both daytime and nighttime, but its impact could be trivial compared to that in the high-NOx region.

Numerous studies (Jang et al., 2002; Czoschke et al., 2003; Offenberg et al., 2009; Surratt et al., 2010; Beardsley and Jang, 2016; Hallquist et al., 2009) have demonstrated the impact of acidic aerosol on daytime SOA. However, nighttime ozonolysis biogenic SOA in this study was insignificantly influenced by seed conditions, as seen in the model simulation (Figs. 4 and 2) and chamber observations (Fig. 2). The nighttime biogenic SOA formed via the NO3-initiated oxidation path was even far less sensitive to the seed condition compared to ozonolysis SOA. Boyd et al. (2017) also reported a similar observation for monoterpenes (Boyd et al., 2017). The heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 (Brown et al., 2006; Hu and Abbatt, 1997) on the surface of inorganic seed lessens the contribution of NO3 radicals to nighttime SOA formation. However, when nighttime SOA formation is dominated by ozonolysis in the low-NOx zone, the SOA formation can be enhanced by wet seed (Fig. S2).

There is a diurnal pattern in the biogenic HC emission showing higher biogenic HC emissions during daytime (Holzke et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2020; Petron et al., 2001; Goldstein et al., 1998). The emission of biogenic HCs is lower by a factor of 3–4 at night (Holzke et al., 2006) than that in daytime considering emission rate and the mixing height, but biogenic SOA yields significantly increase at night because of different oxidation paths and temperature reduction. For example, terpene and isoprene SOA yields at nighttime increase by almost 1 order of magnitude, as discussed in Fig. 5. The concentrations of O3 and NO2 are generally high in ambient air in daytime, involving the photochemical cycle of NOx in the presence of hydrocarbons.

There are model uncertainties to predict SOA due to the simplified gas mechanisms and the missing aerosol-phase reactions, although the UNIPAR model utilizes products originating from explicit gas mechanisms. For example, the daytime β-caryophyllene SOA of this study was underpredicted, as seen in Fig. 3, suggesting that the improvement of explicit gas mechanisms is essential to better predict SOA formation. In the model, the multiphase reaction of biogenic HC is individually treated with four different oxidation paths. Either complex cross reactions between RO2 radicals or the long-term aging process of multiple generation products was not fully considered, causing a bias in SOA prediction. In the presence of inorganic seed, heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 was assumed to be very rapid. However, the variation in aerosol constituents can influence the accommodation coefficient of N2O5. For example, the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 on organic-coated aerosol can be slower than that in the salted aqueous phase (Anttila et al., 2006). In addition, aerosol-phase reactions such as hydrolysis of organonitrates and the oxidation of particulate OM were not included in the model. In the future, the performance of the UNIPAR model for the diurnal variation in biogenic SOA formation needs to be evaluated at regional scales (Yu et al., 2022).

Code to run the SOA model in this study is available upon request.

The chamber data and simulated results used in this study are available upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-1209-2023-supplement.

MJ and SH designed the experiments, and SH carried them out. SH prepared the manuscript with contributions from MJ.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research has been supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. AGS1923651), the National Institute of Environmental Research (grant no. NIER2020-01-01-010), and the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant no. 2020M3G1A1114556).

This paper was edited by Thomas Berkemeier and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Altieri, K. E., Carlton, A. G., Lim, H.-J., Turpin, B. J., and Seitzinger, S. P.: Evidence for oligomer formation in clouds: Reactions of isoprene oxidation products, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 4956–4960, 2006.

Alvarado, A., Tuazon, E. C., Aschmann, S. M., Atkinson, R., and Arey, J.: Products of the gas-phase reactions of O(3P) atoms and O3 with α-pinene and 1,2-dimethyl-1-cyclohexene, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 103, 25541–25551, 1998.

Anttila, T., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Tillmann, R., and Mentel, T. F.: On the reactive uptake of gaseous compounds by organic-coated aqueous aerosols: Theoretical analysis and application to the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5, J. Phys. Chem. A, 110, 10435–10443, 2006.

Atkinson, R. and Arey, J.: Atmospheric degradation of volatile organic compounds, Chem. Rev., 103, 4605–4638, 2003.

Barnes, I., Bastian, V., Becker, K. H., and Tong, Z.: Kinetics and products of the reactions of nitrate radical with monoalkenes, dialkenes, and monoterpenes, J. Phys. Chem., 94, 2413–2419, 1990.

Barreira, L. M. F., Ylisirniö, A., Pullinen, I., Buchholz, A., Li, Z., Lipp, H., Junninen, H., Hõrrak, U., Noe, S. M., Krasnova, A., Krasnov, D., Kask, K., Talts, E., Niinemets, Ü., Ruiz-Jimenez, J., and Schobesberger, S.: The importance of sesquiterpene oxidation products for secondary organic aerosol formation in a springtime hemiboreal forest, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 11781–11800, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-11781-2021, 2021.

Bates, K. H., Burke, G. J. P., Cope, J. D., and Nguyen, T. B.: Secondary organic aerosol and organic nitrogen yields from the nitrate radical (NO3) oxidation of alpha-pinene from various RO2 fates, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 1467–1482, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-1467-2022, 2022.

Beardsley, R. L. and Jang, M.: Simulating the SOA formation of isoprene from partitioning and aerosol phase reactions in the presence of inorganics, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 5993–6009, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-5993-2016, 2016.

Bianchi, F., Kurten, T., Riva, M., Mohr, C., Rissanen, M., Roldin, P., Berndt, T., Crounse, J., Wennberg, P., Mentel, T., Wildt, J., Junninen, H., Jokinen, T., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D., Thornton, J., Donahue, N., Kjaergaard, H., and Ehn, M.: Highly Oxygenated Organic Molecules (HOM) from Gas-Phase Autoxidation Involving Peroxy Radicals: A Key Contributor to Atmospheric Aerosol, Chem. Rev., 119, 3472–3509, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00395, 2019.

Bonn, B. and Moorgat, G. K.: New particle formation during a- and b-pinene oxidation by O3, OH and NO3, and the influence of water vapour: particle size distribution studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 2, 183–196, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2-183-2002, 2002.

Boyd, C. M., Nah, T., Xu, L., Berkemeier, T., and Ng, N. L.: Secondary organic aerosol (SOA) from nitrate radical oxidation of monoterpenes: effects of temperature, dilution, and humidity on aerosol formation, mixing, and evaporation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 7831–7841, 2017.

Brown, S., Ryerson, T., Wollny, A., Brock, C., Peltier, R., Sullivan, A., Weber, R., Dube, W., Trainer, M., and Meagher, J. F.: Variability in nocturnal nitrogen oxide processing and its role in regional air quality, Science, 311, 67–70, 2006.

Brownwood, B., Turdziladze, A., Hohaus, T., Wu, R., Mentel, T. F., Carlsson, P. T., Tsiligiannis, E., Hallquist, M., Andres, S., and Hantschke, L.: Gas-particle partitioning and SOA yields of organonitrate products from NO3-initiated oxidation of isoprene under varied chemical regimes, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 785–800, 2021.

Cao, G. and Jang, M.: An SOA model for toluene oxidation in the presence of inorganic aerosols, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 727–733, 2010.

Carlton, A. G., Wiedinmyer, C., and Kroll, J. H.: A review of Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) formation from isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4987–5005, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4987-2009, 2009.

Carter, W. P.: Development of the SAPRC-07 chemical mechanism, Atmos. Environ., 44, 5324–5335, 2010.

Chan, M. N., Surratt, J. D., Chan, A. W. H., Schilling, K., Offenberg, J. H., Lewandowski, M., Edney, E. O., Kleindienst, T. E., Jaoui, M., Edgerton, E. S., Tanner, R. L., Shaw, S. L., Zheng, M., Knipping, E. M., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Influence of aerosol acidity on the chemical composition of secondary organic aerosol from β-caryophyllene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 1735–1751, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-1735-2011, 2011.

Chen, J., Tang, J., and Yu, X.: Environmental and physiological controls on diurnal and seasonal patterns of biogenic volatile organic compound emissions from five dominant woody species under field conditions, Environ. Pollut., 259, 113955, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.113955, 2020.

Cox, R. A. and Yates, K.: Kinetic equations for reactions in concentrated aqueous acids based on the concept of “excess acidity”, Can. J. Chem., 57, 2944–2951, 1979.

Crounse, J. D., Nielsen, L. B., Jørgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Autoxidation of organic compounds in the atmosphere, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 4, 3513–3520, 2013.

Czoschke, N. M., Jang, M., and Kamens, R. M.: Effect of acidic seed on biogenic secondary organic aerosol growth, Atmos. Environ., 37, 4287–4299, 2003.

Damian, V., Sandu, A., Damian, M., Potra, F., and Carmichael, G. R.: The kinetic preprocessor KPP-a software environment for solving chemical kinetics, Comput. Chem. Eng., 26, 1567–1579, 2002.

Donahue, N., Robinson, A., Stanier, C., and Pandis, S.: Coupled partitioning, dilution, and chemical aging of semivolatile organics, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 2635–2643, https://doi.org/10.1021/es052297c, 2006.

Edwards, P., Aikin, K., Dube, W., Fry, J., Gilman, J., De Gouw, J., Graus, M., Hanisco, T., Holloway, J., and Hübler, G.: Transition from high-to low-NOx control of night-time oxidation in the southeastern US, Nat. Geosci., 10, 490–495, 2017.

Emmerson, K. M. and Evans, M. J.: Comparison of tropospheric gas-phase chemistry schemes for use within global models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 1831–1845, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1831-2009, 2009.

Ervens, B., Feingold, G., Frost, G. J., and Kreidenweis, S. M.: A modeling study of aqueous production of dicarboxylic acids: 1. Chemical pathways and speciated organic mass production, J. Geophys. Res., 109, D15205, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JD004387, 2004.

Finlayson-Pitts, B. J. and Pitts Jr., J. N.: Chemistry of the upper and lower atmosphere: theory, experiments, and applications, Elsevier, ISBN 9780080529073, 1999.

Fry, J. L., Brown, S. S., Middlebrook, A. M., Edwards, P. M., Campuzano-Jost, P., Day, D. A., Jimenez, J. L., Allen, H. M., Ryerson, T. B., Pollack, I., Graus, M., Warneke, C., de Gouw, J. A., Brock, C. A., Gilman, J., Lerner, B. M., Dubé, W. P., Liao, J., and Welti, A.: Secondary organic aerosol (SOA) yields from NO3 radical + isoprene based on nighttime aircraft power plant plume transects, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 11663–11682, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-11663-2018, 2018.

Galib, M. and Limmer, D. T.: Reactive uptake of N2O5 by atmospheric aerosol is dominated by interfacial processes, Science, 371, 921–925, 2021.

Goldstein, A. H. and Galbally, I. E.: Known and unexplored organic constituents in the earth's atmosphere, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 1514–1521, 2007.

Goldstein, A. H., Goulden, M. L., Munger, J. W., Wofsy, S. C., and Geron, C. D.: Seasonal course of isoprene emissions from a midlatitude deciduous forest, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 103, 31045–31056, 1998.

Guenther, A., Hewitt, C. N., Erickson, D., Fall, R., Geron, C., Graedel, T., Harley, P., Klinger, L., Lerdau, M., and McKay, W.: A global model of natural volatile organic compound emissions, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 100, 8873–8892, 1995.

Hallquist, M., Wenger, J. C., Baltensperger, U., Rudich, Y., Simpson, D., Claeys, M., Dommen, J., Donahue, N. M., George, C., Goldstein, A. H., Hamilton, J. F., Herrmann, H., Hoffmann, T., Iinuma, Y., Jang, M., Jenkin, M. E., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Maenhaut, W., McFiggans, G., Mentel, Th. F., Monod, A., Prévôt, A. S. H., Seinfeld, J. H., Surratt, J. D., Szmigielski, R., and Wildt, J.: The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 5155–5236, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-5155-2009, 2009.

Han, S. and Jang, M.: Prediction of secondary organic aerosol from the multiphase reaction of gasoline vapor by using volatility–reactivity base lumping, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 625–639, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-625-2022, 2022.

Han, Y., Stroud, C. A., Liggio, J., and Li, S.-M.: The effect of particle acidity on secondary organic aerosol formation from α-pinene photooxidation under atmospherically relevant conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 13929–13944, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-13929-2016, 2016.

Hasan, G., Valiev, R. R., Salo, V.-T., and Kurtén, T.: Computational Investigation of the Formation of Peroxide (ROOR) Accretion Products in the OH- and NO3-Initiated Oxidation of α-Pinene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 125, 10632–10639, 2021.

Hodzic, A., Kasibhatla, P. S., Jo, D. S., Cappa, C. D., Jimenez, J. L., Madronich, S., and Park, R. J.: Rethinking the global secondary organic aerosol (SOA) budget: stronger production, faster removal, shorter lifetime, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 7917–7941, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-7917-2016, 2016.

Holzke, C., Hoffmann, T., Jaeger, L., Koppmann, R., and Zimmer, W.: Diurnal and seasonal variation of monoterpene and sesquiterpene emissions from Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), Atmos. Environ., 40, 3174–3185, 2006.

Hu, J. and Abbatt, J.: Reaction probabilities for N2O5 hydrolysis on sulfuric acid and ammonium sulfate aerosols at room temperature, J. Phys. Chem. A, 101, 871–878, 1997.

Im, Y., Jang, M., and Beardsley, R. L.: Simulation of aromatic SOA formation using the lumping model integrated with explicit gas-phase kinetic mechanisms and aerosol-phase reactions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 4013–4027, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-4013-2014, 2014.

Jang, M., Czoschke, N., Lee, S., and Kamens, R.: Heterogeneous atmospheric aerosol production by acid-catalyzed particle-phase reactions, Science, 298, 814–817, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1075798, 2002.

Jang, M., Czoschke, N. M., and Northcross, A. L.: Semiempirical model for organic aerosol growth by acid-catalyzed heterogeneous reactions of organic carbonyls, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 164–174, 2005.

Jang, M., Czoschke, N. M., Northcross, A. L., Cao, G., and Shaof, D.: SOA formation from partitioning and heterogeneous reactions: model study in the presence of inorganic species, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 3013–3022, 2006.

Jang, M., Sun, S., Winslow, R., Han, S., and Yu, Z.: In situ aerosol acidity measurements using a UV–Visible micro-spectrometer and its application to the ambient air, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 54, 446–461, 2020.

Jaoui, M., Kleindienst, T. E., Docherty, K. S., Lewandowski, M., and Offenberg, J. H.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from the oxidation of a series of sesquiterpenes: α-cedrene, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene and α-farnesene with O3, OH and NO3 radicals, Environ. Chem., 10, 178–193, 2013.

Jenkin, M. E., Wyche, K. P., Evans, C. J., Carr, T., Monks, P. S., Alfarra, M. R., Barley, M. H., McFiggans, G. B., Young, J. C., and Rickard, A. R.: Development and chamber evaluation of the MCM v3.2 degradation scheme for β-caryophyllene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 5275–5308, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-5275-2012, 2012.

Jenkin, M. E., Young, J. C., and Rickard, A. R.: The MCM v3.3.1 degradation scheme for isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 11433–11459, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-11433-2015, 2015.

Jimenez, J. L., Canagaratna, M., Donahue, N., Prevot, A., Zhang, Q., Kroll, J. H., DeCarlo, P. F., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., and Ng, N.: Evolution of organic aerosols in the atmosphere, Science, 326, 1525–1529, 2009.

Kanakidou, M., Seinfeld, J. H., Pandis, S. N., Barnes, I., Dentener, F. J., Facchini, M. C., Van Dingenen, R., Ervens, B., Nenes, A., Nielsen, C. J., Swietlicki, E., Putaud, J. P., Balkanski, Y., Fuzzi, S., Horth, J., Moortgat, G. K., Winterhalter, R., Myhre, C. E. L., Tsigaridis, K., Vignati, E., Stephanou, E. G., and Wilson, J.: Organic aerosol and global climate modelling: a review, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 1053–1123, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-1053-2005, 2005.

Kelly, J. M., Doherty, R. M., O'Connor, F. M., and Mann, G. W.: The impact of biogenic, anthropogenic, and biomass burning volatile organic compound emissions on regional and seasonal variations in secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7393–7422, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7393-2018, 2018.

Khan, M., Jenkin, M., Foulds, A., Derwent, R., Percival, C., and Shallcross, D.: A modeling study of secondary organic aerosol formation from sesquiterpenes using the STOCHEM global chemistry and transport model, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 122, 4426–4439, 2017.

Kleindienst, T. E., Lewandowski, M., Offenberg, J. H., Jaoui, M., and Edney, E. O.: Ozone-isoprene reaction: Re-examination of the formation of secondary organic aerosol, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L01805, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027485, 2007.

Krechmer, J. E., Day, D. A., and Jimenez, J. L.: Always Lost but Never Forgotten: Gas-Phase Wall Losses Are Important in All Teflon Environmental Chambers, Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, 12890–12897, 2020.

Kristensen, K., Cui, T., Zhang, H., Gold, A., Glasius, M., and Surratt, J. D.: Dimers in α-pinene secondary organic aerosol: effect of hydroxyl radical, ozone, relative humidity and aerosol acidity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 4201–4218, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-4201-2014, 2014.

Kroll, J. H., Ng, N. L., Murphy, S. M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 40, 1869–1877, 2006.

Kwok, E. S., Aschmann, S. M., Arey, J., and Atkinson, R.: Product formation from the reaction of the NO3 radical with isoprene and rate constants for the reactions of methacrolein and methyl vinyl ketone with the NO3 radical, Int. J. Chem. Kinet., 28, 925–934, 1996.

Li, J. and Jang, M.: Aerosol acidity measurement using colorimetry coupled with a reflectance UV-visible spectrometer, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 46, 833–842, 2012.

Li, Y. J., Chen, Q., Guzman, M. I., Chan, C. K., and Martin, S. T.: Second-generation products contribute substantially to the particle-phase organic material produced by β-caryophyllene ozonolysis, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 121–132, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-121-2011, 2011.

Liggio, J., Li, S.-M., and McLaren, R.: Heterogeneous reactions of glyoxal on particulate matter: Identification of acetals and sulfate esters, Environ. Sci. Technol., 39, 1532–1541, 2005.

Magnotta, F. and Johnston, H. S.: Photodissociation quantum yields for the NO3 free radical, Geophys. Res. Lett., 7, 769–772, 1980.

Mauderly, J. L. and Chow, J. C.: Health effects of organic aerosols, Inhal. Toxicol., 20, 257–288, 2008.

Molteni, U., Simon, M., Heinritzi, M., Hoyle, C. R., Bernhammer, A.-K., Bianchi, F., Breitenlechner, M., Brilke, S., Dias, A., and Duplissy, J.: Formation of highly oxygenated organic molecules from α-pinene ozonolysis: chemical characteristics, mechanism, and kinetic model development, ACS Earth Space Chem., 3, 873–883, 2019.

Ng, N. L., Kwan, A. J., Surratt, J. D., Chan, A. W. H., Chhabra, P. S., Sorooshian, A., Pye, H. O. T., Crounse, J. D., Wennberg, P. O., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation from reaction of isoprene with nitrate radicals (NO3), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 4117–4140, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-4117-2008, 2008.

Ng, N. L., Brown, S. S., Archibald, A. T., Atlas, E., Cohen, R. C., Crowley, J. N., Day, D. A., Donahue, N. M., Fry, J. L., Fuchs, H., Griffin, R. J., Guzman, M. I., Herrmann, H., Hodzic, A., Iinuma, Y., Jimenez, J. L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Lee, B. H., Luecken, D. J., Mao, J., McLaren, R., Mutzel, A., Osthoff, H. D., Ouyang, B., Picquet-Varrault, B., Platt, U., Pye, H. O. T., Rudich, Y., Schwantes, R. H., Shiraiwa, M., Stutz, J., Thornton, J. A., Tilgner, A., Williams, B. J., and Zaveri, R. A.: Nitrate radicals and biogenic volatile organic compounds: oxidation, mechanisms, and organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 2103–2162, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-2103-2017, 2017.

Odian, G.: Principles of polymerization, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9780471478751, 2004.

Odum, J., Hoffmann, T., Bowman, F., Collins, D., Flagan, R., and Seinfeld, J.: Gas/particle partitioning and secondary organic aerosol yields, Environ. Sci. Technol., 30, 2580–2585, https://doi.org/10.1021/es950943+, 1996.

Offenberg, J. H., Lewandowski, M., Edney, E. O., Kleindienst, T. E., and Jaoui, M.: Influence of aerosol acidity on the formation of secondary organic aerosol from biogenic precursor hydrocarbons, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 7742–7747, 2009.

Pankow, J. F.: An absorption model of the gas/aerosol partitioning involved in the formation of secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Environ., 28, 189–193, 1994.

Paulson, S. E., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Atmospheric photooxidation of isoprene part I: The hydroxyl radical and ground state atomic oxygen reactions, Int. J. Chem. Kinet., 24, 79–101, 1992.

Perring, A. E., Wisthaler, A., Graus, M., Wooldridge, P. J., Lockwood, A. L., Mielke, L. H., Shepson, P. B., Hansel, A., and Cohen, R. C.: A product study of the isoprene+NO3 reaction, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4945–4956, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4945-2009, 2009.

Petron, G., Harley, P., Greenberg, J., and Guenther, A.: Seasonal temperature variations influence isoprene emission, Geophys. Res. Lett., 28, 1707–1710, 2001.

Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Flannery, B. P., and Vetterling, W. T.: Numerical recipes in Fortran 77: the art of scientific computing, Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521430647, 1992.

Pye, H. O. T., Nenes, A., Alexander, B., Ault, A. P., Barth, M. C., Clegg, S. L., Collett Jr., J. L., Fahey, K. M., Hennigan, C. J., Herrmann, H., Kanakidou, M., Kelly, J. T., Ku, I.-T., McNeill, V. F., Riemer, N., Schaefer, T., Shi, G., Tilgner, A., Walker, J. T., Wang, T., Weber, R., Xing, J., Zaveri, R. A., and Zuend, A.: The acidity of atmospheric particles and clouds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 4809–4888, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-4809-2020, 2020.

Pye, H. O. T., Appel, K. W., Seltzer, K. M., Ward-Caviness, C. K., and Murphy, B. N.: Human-Health Impacts of Controlling Secondary Air Pollution Precursors, Environ. Sci. Tech. Lett., 9, 96–101, 2022.

Roldin, P., Ehn, M., Kurtén, T., Olenius, T., Rissanen, M. P., Sarnela, N., Elm, J., Rantala, P., Hao, L., and Hyttinen, N.: The role of highly oxygenated organic molecules in the Boreal aerosol-cloud-climate system, Nat. Commun., 10, 4370, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12338-8, 2019.

Rollins, A. W., Browne, E. C., Min, K.-E., Pusede, S. E., Wooldridge, P. J., Gentner, D. R., Goldstein, A. H., Liu, S., Day, D. A., and Russell, L. M.: Evidence for NOx control over nighttime SOA formation, Science, 337, 1210–1212, 2012.

Russell, A. R., Valin, L. C., and Cohen, R. C.: Trends in OMI NO2 observations over the United States: effects of emission control technology and the economic recession, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 12197–12209, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-12197-2012, 2012.

Sakulyanontvittaya, T., Guenther, A., Helmig, D., Milford, J., and Wiedinmyer, C.: Secondary organic aerosol from sesquiterpene and monoterpene emissions in the United States, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 8784–8790, 2008.

Saunders, S. M., Jenkin, M. E., Derwent, R. G., and Pilling, M. J.: Protocol for the development of the Master Chemical Mechanism, MCM v3 (Part A): tropospheric degradation of non-aromatic volatile organic compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 3, 161–180, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-3-161-2003, 2003.

Schell, B., Ackermann, I. J., Hass, H., Binkowski, F. S., and Ebel, A.: Modeling the formation of secondary organic aerosol within a comprehensive air quality model system, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 106, 28275–28293, 2001.

Sindelarova, K., Granier, C., Bouarar, I., Guenther, A., Tilmes, S., Stavrakou, T., Müller, J.-F., Kuhn, U., Stefani, P., and Knorr, W.: Global data set of biogenic VOC emissions calculated by the MEGAN model over the last 30 years, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 9317–9341, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-9317-2014, 2014.

Stein, S. and Brown, R.: Estimation of normal boiling points from group contributions, J. Chem. Inf. Comp. Sci., 34, 581–587, https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00019a016, 1994.

Surratt, J. D., Chan, A. W., Eddingsaas, N. C., Chan, M., Loza, C. L., Kwan, A. J., Hersey, S. P., Flagan, R. C., Wennberg, P. O., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Reactive intermediates revealed in secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 6640–6645, 2010.

Tasoglou, A. and Pandis, S. N.: Formation and chemical aging of secondary organic aerosol during the β-caryophyllene oxidation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 6035–6046, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-6035-2015, 2015.

Tsigaridis, K. and Kanakidou, M.: The present and future of secondary organic aerosol direct forcing on climate, Current Climate Change Reports, 4, 84–98, 2018.

Wagner, N., Riedel, T., Young, C. J., Bahreini, R., Brock, C. A., Dubé, W., Kim, S., Middlebrook, A., Öztürk, F., and Roberts, J.: N2O5 uptake coefficients and nocturnal NO2 removal rates determined from ambient wintertime measurements, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 9331–9350, 2013.

Wang, M., Kong, W., Marten, R., He, X.-C., Chen, D., Pfeifer, J., Heitto, A., Kontkanen, J., Dada, L., and Kürten, A.: Rapid growth of new atmospheric particles by nitric acid and ammonia condensation, Nature, 581, 184–189, 2020.

Woo, J. L., Kim, D. D., Schwier, A. N., Li, R., and McNeill, V. F.: Aqueous aerosol SOA formation: impact on aerosol physical properties, Faraday Discuss., 165, 357–367, 2013.

Wood, E. C., Bertram, T. H., Wooldridge, P. J., and Cohen, R. C.: Measurements of N2O5, NO2, and O3 east of the San Francisco Bay, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 483–491, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-483-2005, 2005.

Yu, Z., Jang, M., Zhang, T., Madhu, A., and Han, S.: Simulation of Monoterpene SOA Formation by Multiphase Reactions Using Explicit Mechanisms, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 1455–1467, 2021.