the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Contribution of hydroxymethanesulfonate (HMS) to severe winter haze in the North China Plain

Tao Ma

Hiroshi Furutani

Fengkui Duan

Takashi Kimoto

Jingkun Jiang

Qiang Zhang

Xiaobin Xu

Ying Wang

Jian Gao

Guannan Geng

Shaojie Song

Yongliang Ma

Fei Che

Jie Wang

Lidan Zhu

Tao Huang

Michisato Toyoda

Kebin He

Severe winter haze accompanied by high concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) occurs frequently in the North China Plain and threatens public health. Organic matter (OM) and sulfate are recognized as major components of PM2.5, while atmospheric models often fail to predict their high concentrations during severe winter haze due to incomplete understanding of secondary aerosol formation mechanisms. By using a novel combination of single-particle mass spectrometry and an optimized ion chromatography method, here we show that hydroxymethanesulfonate (HMS), formed by the reaction between formaldehyde (HCHO) and dissolved SO2 in aerosol water, is ubiquitous in Beijing during winter. The HMS concentration and the molar ratio of HMS to sulfate increased with the deterioration of winter haze. High concentrations of precursors (SO2 and HCHO) coupled with low oxidant levels, low temperature, high relative humidity, and moderately acidic pH facilitate the heterogeneous formation of HMS, which could account for up to 15 % of OM in winter haze and lead to up to 36 % overestimates of sulfate when using traditional ion chromatography. Despite the clean air actions having substantially reduced SO2 emissions, the HMS concentration and molar ratio of HMS to sulfate during severe winter haze increased from 2015 to 2016 with the growth in HCHO concentration. Our findings illustrate the significant contribution of heterogeneous HMS chemistry to severe winter haze in Beijing, which helps to improve the prediction of OM and sulfate and suggests that the reduction in HCHO can help to mitigate haze pollution.

- Article

(1329 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1952 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Severe winter haze pollution with high PM2.5 (particles with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 µm) concentration occurs frequently in the North China Plain (NCP), exerting adverse impacts on the environment and human health (Huang et al., 2014; Lelieveld et al., 2015). Secondary components, constituting a large fraction of PM2.5, are key drivers of haze formation (Huang et al., 2014); however, atmospheric models with known formation mechanisms often fail to predict high levels of secondary organic matter (OM) and sulfate during severe winter haze.

Traditional models with gas-phase photochemical mechanisms and aqueous chemistry involving glyoxal and methylglyoxal significantly underestimate the high OM levels observed in the NCP during winter (Wang et al., 2014; B. Zheng et al., 2015). Adding heterogeneous reactions involving isoprene epoxide, glyoxal, and methylglyoxal and accounting for organic aerosol aging and oxidation of intermediate-volatility organic compounds can improve the model predictions of OM (Zhao et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018); however, high OM concentrations observed in Beijing winter are still underpredicted (Hu et al., 2017), especially during the periods with low oxidant concentrations and weak photochemical activity.

In addition to OM, high levels of particulate sulfate are often observed in the NCP during winter, which increase sharply with increasing PM2.5 pollution levels (G. J. Zheng et al., 2015). Traditional atmospheric models containing both gas-phase oxidation of SO2 by OH radicals and aqueous-phase reaction pathways involving H2O2, O3, and O2 catalyzed by Fe3+ and Mn2+ fail to reproduce the observed high sulfate levels, and revised models with heterogeneous chemistry greatly improve the sulfate simulation (Wang et al., 2014; B. Zheng et al., 2015). Cheng et al. (2016) and Wang et al. (2016) reported that the oxidation of SO2 by NO2 in aerosol water under high pH could explain the difference between modeled and observed sulfate. On the other hand, the misidentification of organosulfur compounds as inorganic sulfate in conventional measurements can lead to overestimation of the observed particulate sulfate (Chen et al., 2019). Recently, Moch et al. (2018) and Song et al. (2019) reported the potential contribution of hydroxymethanesulfonate (HMS, ) to particulate sulfur during winter haze in Beijing. However, there is no direct observational evidence for the presence of HMS in haze particles, and the formation mechanism of HMS in NCP winter haze is still unclear.

HMS was previously found at appreciable concentrations in cloud and fog (Munger et al., 1986; Rao and Collett, 1995), whereas the HMS concentrations observed in atmospheric aerosols in the United States, Germany, and Japan were low (Dixon and Aasen, 1999; Suzuki et al., 2001; Scheinhardt et al., 2014). If HMS does play a role in NCP winter haze, unambiguous identification and accurate quantification of aerosol HMS are essential. Low oxidant concentrations, high water content, moderate pH, and low temperatures for typical cloud and fog conditions together with the presence of SO2 and formaldehyde (HCHO) favor HMS formation (Boyce and Hoffmann, 1984; Deister et al., 1986; Kok et al., 1986; Lagrange et al., 1999). Such conditions are common during severe winter haze in the NCP, such as in Beijing (G. J. Zheng et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2016; Rao et al., 2016).

In this study, combining aerosol time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ATOFMS) measurement and an optimized ion chromatography method, we identified the ubiquity of HMS in Beijing during winter and quantified its contribution to severe winter haze. We demonstrate that the reaction between HCHO and dissolved SO2 to form HMS in aerosol water is an important pathway that contributes to winter haze pollution in Beijing, not only accounting for a substantial mass of OM but also leading to an overestimation of sulfate in conventional measurements. High concentrations of precursors (i.e., SO2 and HCHO) coupled with appropriate conditions (i.e., low oxidants, low temperature, high relative humidity, and moderately acidic pH) in severe winter haze favor heterogeneous HMS formation. Furthermore, 2-year continuous winter measurements from 2015 to 2016 indicate that HMS concentrations increased with the increase in HCHO. Finally, we discuss the implications of heterogeneous HMS chemistry for haze chemistry and control strategies.

2.1 Sampling site

Field measurements were conducted in urban Beijing in the winter of 2015 and 2016. The observational sites are located at Tsinghua University (40.00∘ N, 116.34∘ E), the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences (39.95∘ N, 116.33∘ E), and the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences (40.05∘ N, 116.42∘ E) (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Details of the measurements and analysis are described below.

2.2 ATOFMS measurement and data analysis

Real-time ATOFMS (model 3800-100, TSI, Inc.) measurement in Beijing was carried out from 21 December 2015 to 8 January 2016. The observation site was on the tenth floor of the School of Environment, Tsinghua University, approximately 35 m above ground level. Details of ATOFMS measurements have been described in previous studies (Furutani et al., 2011). Briefly, ATOFMS simultaneously measures the size and chemical composition of individual particles. The inlet flow rate is 0.1 L min−1. Ambient aerosols between 100 and 3000 nm enter the ATOFMS instrument through an aerodynamic focusing lens and are accelerated to their size-dependent terminal velocities. The particle velocity is determined by measuring the time-of-flight between two solid-state green lasers (λ=532 nm, 50 mW, CL532-050-L, CrystaLaser, NV, USA). The particle size is calculated from the measured velocity based on the calibration curve between particle size and velocity. In addition, the velocity is used to trigger the 266 nm Nd:YAG laser (∼1 mJ/pulse), which desorbs and ionizes the particle. The generated positive and negative ions are detected using a bipolar reflectron time-of-flight mass analyzer. The ATOFMS aerodynamic sizing was calibrated by standard polystyrene latex spheres (PSLs) with different sizes (d=151, 199, 269, 350, 499, and 799 nm; Duke Scientific Corp., USA). Mass calibration of the ATOFMS instrument was conducted with the standard solution (Ba, K, Pb, Na, Li, V in HNO3).

During the winter campaign, ATOFMS detected 4 495 233 particles containing both size and chemical information, accounting for 49 % of all sized particles. Single-particle mass spectrometers identify the peak at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode as HMS (Neubauer et al., 1997; Whiteaker and Prather, 2003; Dall'Osto et al., 2009). To eliminate interferences, HMS-containing particles were screened with a relatively high threshold: the peak area at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode should be greater than 2 % of the total integrated area of the single-particle negative ion mass spectrum (Whiteaker and Prather, 2003).

2.3 Offline sample collection and ion chromatography analysis

PM2.5 samples were collected on 47 mm quartz filters at a flow rate of 15.4 L min−1 for 23.5 h every day. Here, we analyzed 36 and 33 samples in the winter of 2015 and 2016, respectively. In the winter of 2016, we also collected three and five PM2.5 samples on 90 mm quartz filters at a flow rate of 100 L min−1 in the day- and nighttime, respectively. The filters were baked in a Muffle furnace at 550 ∘C for 4 h, put in the cassettes, and packed using aluminum foil prior to sampling, and all samples were stored at −20 ∘C before analysis. A quarter of each 47 mm filter or a 3.14 cm2 punch from each 90 mm filter was extracted twice with 5 mL 0.1 % HCHO solution, treated with ultrasonic agitation for 20 min in an ice water bath, and then filtered through the 0.45 µm membrane syringe filter. Two extracts were combined for ion chromatography analysis. We found that HMS slowly converted to sulfate during conventional sample preparation (i.e., water extraction), leading to HMS underestimation and sulfate overestimation, whereas extraction with 0.1 % HCHO solution can counteract the HMS decomposition (Fig. S2a, b).

A Dionex Integrion HPIC ion chromatography system with AS11-HC analytical column and AG11-HC guard column (Dionex Corp., CA, US), typical columns used in previous studies during winter haze in Beijing (Cao et al., 2014), was used for the anion analysis. The separation of HMS and sulfate depends on ion chromatography conditions (i.e., column and eluent). We found that the separation of HMS and sulfate peak was not complete under conventional conditions (eluent: 30 mM KOH; flow rate: 1.5 mL min−1) (Fig. S2c). Here, we used an eluent of 11 mM KOH (pH ≈12) with a flow rate of 1.5 mL min−1 and successfully distinguished HMS from sulfate (Fig. S2d). In addition, Moch et al. (2018) and Dovrou et al. (2019) found that the AS22 column could not fully separate HMS and sulfate, while AS12A was able to successfully separate HMS and sulfate. HMS dissociates into and HCHO rapidly in the eluent due to the short characteristic time for HMS dissociation at pH 12, and the HMS concentration is measured in the form of sulfite in ion chromatography (Fig. S2e) (Dasgupta, 1982). Thus, the ion chromatography method cannot distinguish HMS from sulfite directly. Previous studies indicated that the concentration of sulfite in atmospheric aerosols was much lower than that of HMS (Dixon and Aasen, 1999; Dabek-Zlotorzynska et al., 2002). In order to distinguish between sulfite and HMS, a second analysis was performed using dilute nitric acid (pH ≈3) to extract samples. In the second analysis, sulfite is oxidized to sulfate, while HMS is stable. We tested some samples collected during severe winter haze in Beijing and found that the influence of sulfite on HMS measurement was negligible (Fig. S2f). The method detection limit was 0.02 mg L−1 for , equal to 0.03 mg L−1 for HMS. The blank quartz filter was analyzed as a control. We also tested the accuracy (through recovery analysis) and precision (through repetitive analysis) of the method on HMS analysis. The recovery of blank and sample was 95.6 % and 112.5 %, respectively. The relative standard deviation (RSD) of triple repetitive analysis of the sample (average: 3.17 mg L−1) was 4.7 %.

2.4 Supplementary data and analysis

Online measurements of gaseous pollutants, particulate matter, and meteorological parameters were conducted on the roof of School of Economics and Management, approximately 20 m above ground level and 100 m away from the ATOFMS observation site, on the campus of Tsinghua University as described in previous works (G. J. Zheng et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2017). In brief, hourly mass concentrations of PM2.5 and PM1 were monitored based on the β-ray absorption method by using two dichotomous monitors (PM-712 and PM-714; Kimoto Electric Co., Ltd., Japan). The hourly concentrations of carbonaceous species including organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) in PM2.5 in 2015 winter were monitored by APC-710 (Kimoto Electric Co., Ltd., Japan). The hourly OC and EC concentrations in PM2.5 in 2016 winter were measured by a Sunset Model 4 semi-continuous carbon analyzer (Beaverton, OR, USA). We adopted a factor of 1.6 to convert the OC mass into OM mass (Xing et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017). The hourly concentrations of gaseous pollutants including SO2, CO, and O3 were monitored with a MCSAM-13 system (Kimoto Electric, Ltd., Japan). The hourly meteorological parameters including temperature and relative humidity (RH) were simultaneously monitored with an automatic meteorological observation instrument (Milos 520, VAISALA Inc., Finland).

Online concentrations of water-soluble ions in PM2.5 and inorganic gases were measured by a Monitor for AeRosols and GAses (MARGA; Metrohm Ltd., Switzerland) in winter 2016 at the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, about 9 km from Tsinghua University. We calculated the aerosol water content and pH with the ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic equilibrium model (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007). Briefly, we adopted the forward mode constrained by gas (HNO3, HCl, and NH3) + aerosol (, , Cl−, K+, Ca2+, Na+, Mg2+, and ) measurements and assumed the aerosol phase state to be metastable (Hennigan et al., 2015). The model inputs were taken from the MARGA measurements.

Online HCHO measurement was conducted in winter 2015 at the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, about 6 km from Tsinghua University. Ambient HCHO was measured by an Aero-Laser GmbH HCHO analyzer (model AL4021) based on the Hantzsch reaction, as described in previous work (Song et al., 2019). The Hantzsch reagents were prepared every 3 d and stored in a refrigerator. This analyzer was calibrated with a 1 µM HCHO standard solution every 2 to 3 d. The detection limit is 150 ppt in the field, and the accuracy and precision are ±15 % or 150 ppt and ±10 % or 150 ppt, respectively (Hak et al., 2005).

The anthropogenic emission inventory data of HCHO was derived from the Multi-resolution Emission Inventory of China (MEIC) model framework (available at http://www.meicmodel.org/, last access: 21 September 2019), as described in detail in earlier papers (M. Li et al., 2019). Briefly, the emissions were calculated based on a technology-based methodology using updated activity data from the MEIC model framework and a collection of state-of-the-art emission factors and source profiles. The uncertainty of the volatile organic compound (VOC) emission inventory in MEIC was estimated to be ±68 % (Cheng et al., 2019).

3.1 Identification of HMS in atmospheric particles

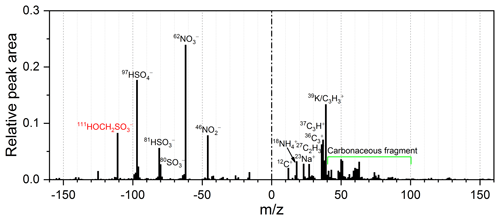

Our field measurements with ATOFMS showed that HMS was ubiquitous in aerosols from Beijing during winter. We found that 76 % of particles contained the peak at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode, and screened HMS-containing particles (the relative peak area at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode greater than 2 %; Fig. 1) accounted for 9 % of the total particles. It should be noted that and methyl sulfate () could also contribute to the peak at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode. According to the natural isotopic distribution, the contribution of was found to be insignificant. The peak area ratio of m∕z 111 to m∕z 113 in the negative ion mode in all screened particles was 18.7, which was consistent with the natural isotopic distribution of HMS (18.7) and much larger than that of (4.8). Also, the peak area ratio of m∕z 109 to m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode in all screened particles was 0.03, which was much smaller than that of (1.4). Considering the moderate aerosol pH (4–5; see Sect. 3.3) in Beijing winter haze and the tendency of m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode to exist in supermicrometer particles (see Sect. 3.2) in this study, the peak at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode unlikely corresponds to methyl sulfate since methyl sulfate formation requires relatively high acidic conditions (Lee, 2003) and organosulfates tend to exist in submicrometer particles (Hatch et al., 2011). Therefore, the peak at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode in ambient particles can safely be assigned to HMS. Ambient particles in Beijing during winter contained a large amount of ammonium relative to sodium, and the ammonium was more common than sodium in HMS-containing particles (Fig. S3), indicating that the matrix effects on HMS detection due to counterions was not significant, because ammonium promotes the presence of the HMS marker peak in the negative ion spectrum (Neubauer et al., 1997; Whiteaker and Prather, 2003). The mass spectrum of HMS-containing particles observed in this study is similar to previous studies (Whiteaker and Prather, 2003; Dall'Osto et al., 2009; Song et al., 2019). In general, the positive mass spectra are characterized by the presence of ammonium (m∕z 18 ), elemental carbon (m∕z 12 C+, 36 , 48 , and 60 ), and organic carbon (m∕z 27 , 37 C3H+, 39 , and 43 C2H3O+), whilst the peaks at m∕z 46 (), 62 (), 80 (), 81 (), and 97 () are common in the negative mass spectra.

Figure 1Presence of HMS in single-particle mass spectra during winter in Beijing. The peak at m∕z 111 in the negative ion mode is attributed to HMS (). The peaks at m∕z 80 (), 81 (), 97 (), 46 (), and 62 () are also common in the negative ion spectrum, indicating the presence of sulfur species and nitrate. In the positive mass spectra, inorganic ions (m∕z 18 , 23 Na+, and 39 K+), elemental carbon (m∕z 12 C+, 36 , and 48 ), and organic carbon (m∕z 27 , 37 C3H+, 39 , and 43 C2H3O+) are present.

3.2 Quantification of HMS in atmospheric particles

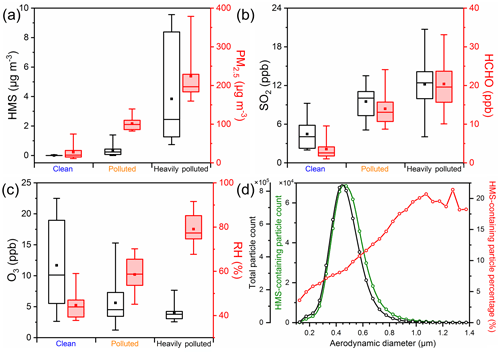

Based on the optimized ion chromatography method, we determined the HMS concentration and its contribution to haze pollution in winter. We found that the HMS concentration was appreciable in humid haze conditions but low in clean and dry haze conditions (Fig. S4). The HMS concentration exhibited similar periodic variation to that of PM2.5 and sulfate concentration in winter and was consistent with the variation in RH. With the deterioration of winter haze in 2015, i.e., from clean (PM2.5≤75 µg m−3, 10 d) to polluted (75< PM2.5≤150 µg m−3, 12 d) to heavily polluted (PM2.5>150 µg m−3, 14 d), the HMS concentration increased rapidly (Fig. 2a). Also, the molar ratio of HMS to sulfate increased from 0 (clean) to 0.02 (polluted) to 0.06 (heavily polluted). During the HMS increase process, RH, SO2, and the HCHO concentration increased, while the O3 concentration declined (Fig. 2b, c). HMS tends to exist in supermicrometer particles. During the HMS events, the ratio of PM1–2.5 to PM2.5 was generally greater than 0.4, indicating a large contribution of supermicrometer aerosols. The size distribution of HMS-containing particles displayed a mode at larger sizes compared with the total particle size distribution, and the percentage of HMS-containing particles increased with particle size and remained relatively constant when the diameter is greater than 1 µm (Fig. 2d), indicating the predominance of HMS in larger particles.

Figure 2Evolution of HMS in Beijing winter of 2015. (a–c) Concentrations of HMS, PM2.5, SO2, HCHO, O3, and RH at different pollution levels from 26 November 2015 to 8 January 2016. In the box–whisker plots, the whiskers, boxes, and points indicate the 95th, 75th, 50th, 25th, 5th percentiles, and mean values. (d) Size distribution of HMS-containing particles from 21 December 2015 to 8 January 2016.

Field measurements in Beijing in winter 2016 showed a similar HMS evolution to that of winter 2015; i.e., high HMS concentrations usually occurred in humid haze conditions with high concentrations of precursors, high RH, and weak photochemical activity (Figs. S5 and S6), but HMS concentrations were higher than in winter 2015. During severe winter haze (PM2.5>150 µg m−3), the concentrations of HMS, PM2.5, OM, and sulfate were 4 µg m−3 (0.7–9.6 µg m−3), 224 µg m−3 (160–379 µg m−3), 83 µg m−3 (45–121 µg m−3), and 45 µg m−3 (23–108 µg m−3) in 2015 and 7 µg m−3 (0.4–18.5 µg m−3), 237 µg m−3 (154–339 µg m−3), 97 µg m−3 (65–147 µg m−3), and 36 µg m−3 (15–66 µg m−3) in 2016. The HMS accounted for 1.5 % (0.4 %–4 %) of PM2.5 mass in 2015, and this contribution increased to 2.7 % (0.3 %–6 %) in 2016 (Fig. S7). Correspondingly, the contribution of HMS to estimated OM increased from 4.4 % (0.9 %–11 %) in 2015 to 7.6 % (1.4 %–15 %) in 2016. The increase in HMS from winter 2015 to winter 2016 was consistent with the increasing HCHO concentration. Instead, the concentrations of SO2 during severe winter haze decreased significantly due to the strict control measures, resulting in a decrease in sulfate. Accordingly, the molar ratio of HMS to sulfate increased significantly from winter 2015 to winter 2016. Considering the conversion of HMS to sulfate in conventional ion chromatography analysis, the observed sulfate concentrations during severe winter haze could be overestimated by 6.4 % (3 %–15 %) in 2015, and the ratio increased to 15 % (2.5 %–36 %) in 2016.

3.3 Factors influencing HMS formation

HMS is formed in the aqueous phase, such as cloud (Moch et al., 2018), fog (Munger et al., 1986), and aerosol water (Song et al., 2019). We find that HMS is present in aerosols regardless of the presence of cloud or fog (Fig. S8a, b), and HMS concentrations show a good correlation (r=0.92, P<0.01) with aerosol water content (Fig. S8b), indicating that aerosol water serves as a medium for HMS formation. In some HMS events, cloud or fog processes exist (Fig. S8a, b) and, together with heterogeneous processes in aerosol water, may contribute to the formation of HMS. Our results indicate that high concentrations of precursors (i.e., SO2 and HCHO) coupled with appropriate conditions (i.e., low oxidants, low temperature, high RH, and moderately acidic pH) in severe winter haze in the NCP facilitate the heterogeneous HMS formation.

Low oxidants and low temperature during winter haze facilitate HMS formation. S(IV) oxidation reactions compete with HMS formation (Pandis and Seinfeld, 1989). The low O3 concentration and low solar radiation during HMS events (Figs. S4 and S5) indicate the weak photochemical activity. Previous measurements also showed that OH radical and H2O2 concentrations were low in winter, especially during severe winter haze (Zhang et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2018). Low temperature increases the solubility of gas (Sander, 2015), whereas it decreases the reaction rate constant for HMS production (Boyce and Hoffmann, 1984). According to the kinetics calculation (Song et al., 2019), the increase in gas solubility in water at low temperature is greater than the decrease in the reaction rate constant, leading to higher HMS formation rate in winter haze. Once formed, HMS is relatively stable due to the self-acidification and resistance to oxidation by O3, H2O2, and O2 (Dasgupta et al., 1980; Hoigne et al., 1985; Kok et al., 1986; Munger et al., 1986).

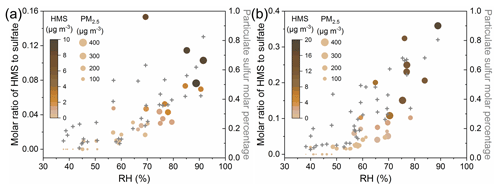

High RH is a key factor driving fast HMS formation in winter haze. The HMS concentration increases slowly under low RH, whereas it increases rapidly under high RH (Fig. S9). Similarly, the aerosol water content exhibits an exponential increase with RH (Fig. S10), providing abundant reaction interfaces for HMS formation. The HMS concentration started to increase significantly with the enhancement in RH when the RH >60 %, coinciding with the reported deliquesce RH of particles in Beijing winter (Y. Liu et al., 2017). With the increase in RH, the atmospheric sulfur distribution shifts toward the particle phase and more particulate sulfur exists in the form of HMS (Fig. 3). The molar ratio of HMS to sulfate also started to increase rapidly at the RH ∼60 %, and high values usually occurred under severe winter haze with high PM2.5 and HMS concentrations.

Figure 3Evolution of sulfur distribution with the increase in RH in the winter of (a) 2015 and (b) 2016. The solid circles represent the molar ratio of HMS to sulfate, colored by the HMS concentrations and sized by the PM2.5 concentrations. The gray crosses represent the particulate sulfur molar percentage. Particulate sulfur molar percentage .

Moderately acidic pH in Beijing winter haze favors the HMS formation. Previous studies indicated that both HMS formation and decomposition rate increased rapidly with pH; thereby, high HMS concentrations were usually observed in moderate-pH conditions, since low pH retards the formation of HMS, while high pH is not suitable for its preservation (Munger et al., 1986). The calculations based on the ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic equilibrium model constrained by in situ gas and aerosol measurements showed an average pH value of 4.5 (from 4 to 5) for aerosol water under severe winter haze in 2016, which agreed reasonably with previous studies in the NCP (M. Liu et al., 2017; Song et al., 2018; Ding et al., 2019; Ge et al., 2019; H. Li et al., 2019) and was higher than those in the United States and Europe (Bougiatioti et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2016). Under such conditions, HMS formation is favored, whereas decomposition of HMS is negligible, thereby resulting in the observed high HMS concentrations during severe winter haze.

3.4 Implications for haze chemistry and control strategies

Our findings reveal the significant contribution of HMS to severe winter haze. We propose a more comprehensive conceptual model of heterogeneous sulfur chemistry in NCP haze events, including traditional sulfate formation, and HMS formation under high HCHO concentrations, low oxidant levels, low temperature, high RH, and moderate pH (Fig. 4a). With the deterioration of winter haze, the atmospheric oxidation capacity decreases with the weak photochemical activity, while heterogeneous HMS chemistry is enhanced, resulting in the increase in HMS concentration and the ratio of HMS to sulfate (Fig. 4b). Adding heterogeneous HMS chemistry into the model could improve the simulation of OM. In addition, the presence of HMS could lead to sulfate overestimation in conventional measurements, such as ion chromatography and aerosol mass spectrometry (Song et al., 2019). This can partly explain the discrepancy between sulfate simulation and observation during severe NCP winter haze. Furthermore, HMS can be used as a tracer for heterogeneous chemistry and moderate pH during typical winter haze pollution.

Figure 4Schematic of the heterogeneous sulfur chemistry. (a) Oxidation and addition reaction pathways of dissolved SO2 in aerosol water under different atmospheric conditions. (b) Evolution of sulfur-containing species during winter haze deterioration in the NCP. With the increase in RH and decrease in atmospheric oxidation capacity under NCP winter haze, the atmospheric sulfur distribution shifts toward the particle phase and more particulate sulfur exists in the form of HMS. The gray, red, and green colors represent SO2, , and HMS, respectively.

Our results suggest that the reduction in HCHO concentration can help to mitigate severe winter haze pollution in the NCP. Previous studies show that HCHO is an important source of ROx () radicals and ozone (Niu et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2018; M. Li et al., 2019) and has high toxicity as a Group 1 human carcinogen (Niu et al., 2016); in this study, we further demonstrate its significant contribution to particulate matter in winter. Since the implementation of the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan in 2013, SO2 concentrations during winter haze in Beijing have decreased significantly due to the implementation of desulfurization measures and controls on emission activities (G. J. Zheng et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2018), resulting in the decrease in sulfate, while HCHO concentrations show an increasing trend (Fig. S7), leading to the increased importance of HMS in winter haze. HCHO comes from primary emissions and secondary formation (Chen et al., 2014; Sheng et al., 2018). Therefore, the cooperative emission reduction in primary HCHO, which mainly comes from residential solid fuel (biofuel and coal) combustion and transportation (Fig. S11) (M. Li et al., 2019), and VOCs (e.g., alkenes, aromatics, and alkanes) related to secondary HCHO formation should be considered in future pollutant control strategies in the NCP. Furthermore, the HMS chemistry and related control strategies can be applicable to other regions with high SO2 and HCHO concentrations, such as India (De Smedt et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017).

Combining field measurements and laboratory experiments, we show the ubiquity of HMS in aerosols and the quantification of the large amounts of HMS in PM2.5 in Beijing during winter and elucidate the heterogeneous HMS chemistry in winter haze. High concentrations of precursors (SO2 and HCHO), low oxidant levels, low temperature, high RH, and moderately acidic pH during severe winter haze facilitate the heterogeneous formation of HMS, which could account for up to 15 % of OM in winter haze and lead to up to 36 % overestimates of sulfate. The HMS concentration and the molar ratio of HMS to sulfate increased with the deterioration of winter haze, as well as from winter 2015 to winter 2016 with the growth in HCHO concentration. Our results reveal the significant contribution of HMS to severe winter haze, which helps to improve the prediction of OM and sulfate and suggests that the reduction in HCHO can help to mitigate severe winter haze pollution.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-5887-2020-supplement.

TM, FD, and KH designed the research; TM, HF, FD, TK, JJ, YM, LZ, TH, MT, and KH performed the research; TM, HF, TK, and SS contributed new reagents and analytic tools; TM and HF analyzed data; QZ, GG, and ML provided the emission inventory; XX and YW provided formaldehyde data; JG, FC, and JW provided MARGA data; TM wrote the paper; and TM, HF, FD, JJ, QZ, and KH revised the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank Weiya Yu and Xiaodong Liu for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Program of China (2017YFC0211601), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571130090), the National Research Program for Key Issues in Air Pollution Control (DQGG0103), and the Tsinghua-Toyota General Research Center.

This paper was edited by Aijun Ding and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bougiatioti, A., Nikolaou, P., Stavroulas, I., Kouvarakis, G., Weber, R., Nenes, A., Kanakidou, M., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Particle water and pH in the eastern Mediterranean: source variability and implications for nutrient availability, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 4579–4591, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-4579-2016, 2016.

Boyce, S. D. and Hoffmann, M. R.: Kinetics and mechanism of the formation of hydroxymethanesulfonic acid at low pH, J. Phys. Chem., 88, 4740–4746, https://doi.org/10.1021/j150664a059, 1984.

Cao, C., Jiang, W. J., Wang, B. Y., Fang, J. H., Lang, J. D., Tian, G., Jiang, J. K., and Zhu, T. F.: Inhalable Microorganisms in Beijing's PM2.5 and PM10 Pollutants during a Severe Smog Event, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 1499–1507, https://doi.org/10.1021/es4048472, 2014.

Chen, W. T., Shao, M., Lu, S. H., Wang, M., Zeng, L. M., Yuan, B., and Liu, Y.: Understanding primary and secondary sources of ambient carbonyl compounds in Beijing using the PMF model, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 3047–3062, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-3047-2014, 2014.

Chen, Y., Xu, L., Humphry, T., Hettiyadura, A. P. S., Ovadnevaite, J., Huang, S., Poulain, L., Schroder, J. C., Campuzano-Jost, P., Jimenez, J. L., Herrmann, H., O'Dowd, C., Stone, E. A., and Ng, N. L.: Response of the Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer to Inorganic Sulfates and Organosulfur Compounds: Applications in Field and Laboratory Measurements, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 5176–5186, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b00884, 2019.

Cheng, J., Su, J., Cui, T., Li, X., Dong, X., Sun, F., Yang, Y., Tong, D., Zheng, Y., Li, Y., Li, J., Zhang, Q., and He, K.: Dominant role of emission reduction in PM2.5 air quality improvement in Beijing during 2013–2017: a model-based decomposition analysis, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 6125–6146, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-6125-2019, 2019.

Cheng, Y. F., Zheng, G. J., Wei, C., Mu, Q., Zheng, B., Wang, Z. B., Gao, M., Zhang, Q., He, K. B., Carmichael, G., Poschl, U., and Su, H.: Reactive nitrogen chemistry in aerosol water as a source of sulfate during haze events in China, Sci. Adv., 2, e1601530, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601530, 2016.

Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E., Piechowski, M., Keppel-Jones, K., and Aranda-Rodriguez, R.: Determination of hydroxymethanesulfonic acid in environmental samples by capillary electrophoresis, J. Sep. Sci., 25, 1123–1128, https://doi.org/10.1002/1615-9314(20021101)25:15/17<1123::aid-jssc1123>3.0.co;2-3, 2002.

Dall'Osto, M., Harrison, R. M., Coe, H., and Williams, P.: Real-time secondary aerosol formation during a fog event in London, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2459–2469, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2459-2009, 2009.

Dasgupta, P. K.: On the ion chromatographic determination of S(IV), Atmos. Environ., 16, 1265–1268, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(82)90217-7, 1982.

Dasgupta, P. K., Decesare, K., and Ullrey, J. C.: Determination of atmospheric sulfur-dioxide without tetrachloromercurate (II) and the mechanism of the schiff reaction, Anal. Chem., 52, 1912–1922, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac50062a031, 1980.

Deister, U., Neeb, R., Helas, G., and Warneck, P.: Temperature Dependence of the Equilibrium CH2(OH)2 + = + H2O in Aqueous Solution, J. Phys. Chem., 90, 3213–3217, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100405a033, 1986.

De Smedt, I., Stavrakou, T., Hendrick, F., Danckaert, T., Vlemmix, T., Pinardi, G., Theys, N., Lerot, C., Gielen, C., Vigouroux, C., Hermans, C., Fayt, C., Veefkind, P., Müller, J.-F., and Van Roozendael, M.: Diurnal, seasonal and long-term variations of global formaldehyde columns inferred from combined OMI and GOME-2 observations, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 12519–12545, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-12519-2015, 2015.

Ding, J., Zhao, P., Su, J., Dong, Q., Du, X., and Zhang, Y.: Aerosol pH and its driving factors in Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 7939–7954, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-7939-2019, 2019.

Dixon, R. W. and Aasen, H.: Measurement of hydroxymethanesulfonate in atmospheric aerosols, Atmos. Environ., 33, 2023–2029, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1352-2310(98)00416-6, 1999.

Dovrou, E., Lim, C. Y., Canagaratna, M. R., Kroll, J. H., Worsnop, D. R., and Keutsch, F. N.: Measurement techniques for identifying and quantifying hydroxymethanesulfonate (HMS) in an aqueous matrix and particulate matter using aerosol mass spectrometry and ion chromatography, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 12, 5303–5315, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-5303-2019, 2019.

Fountoukis, C. and Nenes, A.: ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+–Ca2+–Mg2+––Na+–––Cl−–H2O aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 4639–4659, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007, 2007.

Furutani, H., Jung, J., Miura, K., Takami, A., Kato, S., Kajii, Y., and Uematsu, M.: Single-particle chemical characterization and source apportionment of iron-containing atmospheric aerosols in Asian outflow, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 116, D18204, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jd015867, 2011.

Ge, B., Xu, X., Ma, Z., Pan, X., Wang, Z., Lin, W., Ouyang, B., Xu, D., Lee, J., Zheng, M., Ji, D., Sun, Y., Dong, H., Squires, F. A., Fu, Q., and Wang, Z.: Role of Ammonia on the Feedback Between AWC and Inorganic Aerosol Formation During Heavy Pollution in the North China Plain, Earth Space Sci. 6, 1675–1693. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019ea000799, 2019.

Hak, C., Pundt, I., Trick, S., Kern, C., Platt, U., Dommen, J., Ordóñez, C., Prévôt, A. S. H., Junkermann, W., Astorga-Lloréns, C., Larsen, B. R., Mellqvist, J., Strandberg, A., Yu, Y., Galle, B., Kleffmann, J., Lörzer, J. C., Braathen, G. O., and Volkamer, R.: Intercomparison of four different in-situ techniques for ambient formaldehyde measurements in urban air, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 5, 2881–2900, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-5-2881-2005, 2005.

Hatch, L. E., Creamean, J. M., Ault, A. P., Surratt, J. D., Chan, M. N., Seinfeld, J. H., Edgerton, E. S., Su, Y. X., and Prather, K. A.: Measurements of Isoprene-Derived Organosulfates in Ambient Aerosols by Aerosol Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry – Part 1: Single Particle Atmospheric Observations in Atlanta, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 5105–5111, https://doi.org/10.1021/es103944a, 2011.

Hennigan, C. J., Izumi, J., Sullivan, A. P., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: A critical evaluation of proxy methods used to estimate the acidity of atmospheric particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2775–2790, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2775-2015, 2015.

Hoigne, J., Bader, H., Haag, W. R., and Staehelin, J.: Rate constants of reactions of ozone with organic and inorganic-compounds in water .3. inorganic-compounds and radicals, Water Res., 19, 993–1004, https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1354(85)90368-9, 1985.

Hu, J., Wang, P., Ying, Q., Zhang, H., Chen, J., Ge, X., Li, X., Jiang, J., Wang, S., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., and Zhang, Y.: Modeling biogenic and anthropogenic secondary organic aerosol in China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 77–92, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-77-2017, 2017.

Huang, R. J., Zhang, Y., Bozzetti, C., Ho, K. F., Cao, J. J., Han, Y., Daellenbach, K. R., Slowik, J. G., Platt, S. M., Canonaco, F., Zotter, P., Wolf, R., Pieber, S. M., Bruns, E. A., Crippa1, M., Ciarelli, G., Piazzalunga, A., Schwikowski, M., Abbaszade, G., Schnelle-Kreis, J., Zimmermann, R., An, Z., Szidat, S., Baltensperger, U., Haddad, I. E., and Prévôt, A. S. H.: High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China, Nature, 514, 218–222, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13774, 2014.

Kok, G. L., Gitlin, S. N., and Lazrus, A. L.: Kinetics of the formation and decomposition of hydroxymethanesulfonate, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 91, 2801–2804, https://doi.org/10.1029/JD091iD02p02801, 1986.

Lagrange, J., Wenger, G., and Lagrange, P.: Kinetic study of HMSA formation and decomposition: Tropospheric relevance, J. Chim. Phys. Phys.-Chim. Biol., 96, 610–633, https://doi.org/10.1051/jcp:1999161, 1999.

Lee, S. H.: Nitrate and oxidized organic ions in single particle mass spectra during the 1999 Atlanta Supersite Project, J. Geophys. Res., 108, D78417, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001jd001455, 2003.

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D., and Pozzer, A.: The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale, Nature, 525, 367–371, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15371, 2015.

Li, C., McLinden, C., Fioletov, V., Krotkov, N., Carn, S., Joiner, J., Streets, D., He, H., Ren, X., Li, Z., and Dickerson, R. R.: India Is Overtaking China as the World's Largest Emitter of Anthropogenic Sulfur Dioxide, Sci. Rep., 7, 14304, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14639-8, 2017.

Li, H., Cheng, J., Zhang, Q., Zheng, B., Zhang, Y., Zheng, G., and He, K.: Rapid transition in winter aerosol composition in Beijing from 2014 to 2017: response to clean air actions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 11485–11499, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-11485-2019, 2019.

Li, M., Zhang, Q., Zheng, B., Tong, D., Lei, Y., Liu, F., Hong, C., Kang, S., Yan, L., Zhang, Y., Bo, Y., Su, H., Cheng, Y., and He, K.: Persistent growth of anthropogenic non-methane volatile organic compound (NMVOC) emissions in China during 1990–2017: drivers, speciation and ozone formation potential, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 8897–8913, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-8897-2019, 2019.

Liu, M., Song, Y., Zhou, T., Xu, Z., Yan, C., Zheng, M., Wu, Z., Hu, M., Wu, Y., and Zhu, T.: Fine particle pH during severe haze episodes in northern China, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 5213–5221, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl073210, 2017.

Liu, Y., Wu, Z., Wang, Y., Xiao, Y., Gu, F., Zheng, J., Tan, T., Shang, D., Wu, Y., Zeng, L., Hu, M., Bateman, A. P., and Martin, S. T.: Submicrometer Particles Are in the Liquid State during Heavy Haze Episodes in the Urban Atmosphere of Beijing, China, Environ. Sci. Tech. Let., 4, 427–432, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00352, 2017.

Moch, J. M., Dovrou, E., Mickley, L. J., Keutsch, F. N., Cheng, Y., Jacob, D. J., Jiang, J., Li, M., Munger, J. W., Qiao, X., and Zhang, Q.: Contribution of hydroxymethane sulfonate to ambient particulate matter: A potential explanation for high particulate sulfur during severe winter haze in Beijing, Geophys. Res. Lett., 45, 11969–11979, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018gl079309, 2018.

Munger, J. W., Tiller, C., and Hoffmann, M. R.: Identification of hydroxymethanesulfonate in fog water, Science, 231, 247–249, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.231.4735.247, 1986.

Neubauer, K. R., Johnston, M. V., and Wexler, A. S.: On-line analysis of aqueous aerosols by laser desorption ionization, Int. J. Mass Spectrom., 163, 29–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1176(96)04534-x, 1997.

Niu, H., Mo, Z. W., Shao, M., Lu, S. H., and Xie, S. D.: Screening the emission sources of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in China by multi-effects evaluation, Front. Environ. Sci. En., 10, 1, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-016-0828-z, 2016.

Pandis, S. N. and Seinfeld, J. H.: Sensitivity analysis of a chemical mechanism for aqueous-phase atmospheric chemistry, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 94, 1105–1126, https://doi.org/10.1029/JD094iD01p01105, 1989.

Rao, X. and Collett, J. L.: Behavior of S(IV) and formaldehyde in a chemically heterogeneous cloud, Environ. Sci. Technol., 29, 1023–1031, https://doi.org/10.1021/es00004a024, 1995.

Rao, Z. H., Chen, Z. M., Liang, H., Huang, L. B., and Huang, D.: Carbonyl compounds over urban Beijing: Concentrations on haze and non-haze days and effects on radical chemistry, Atmos. Environ., 124, 207–216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.06.050, 2016.

Sander, R.: Compilation of Henry's law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 4399–4981, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-4399-2015, 2015.

Scheinhardt, S., van Pinxteren, D., Muller, K., Spindler, G., and Herrmann, H.: Hydroxymethanesulfonic acid in size-segregated aerosol particles at nine sites in Germany, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 4531–4538, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-4531-2014, 2014.

Sheng, J., Zhao, D., Ding, D., Li, X., Huang, M., Gao, Y., Quan, J., and Zhang, Q.: Characterizing the level, photochemical reactivity, emission, and source contribution of the volatile organic compounds based on PTR-TOF-MS during winter haze period in Beijing, China, Atmos. Res., 212, 54–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2018.05.005, 2018.

Song, S., Gao, M., Xu, W., Shao, J., Shi, G., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., and McElroy, M. B.: Fine-particle pH for Beijing winter haze as inferred from different thermodynamic equilibrium models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7423–7438, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7423-2018, 2018.

Song, S., Gao, M., Xu, W., Sun, Y., Worsnop, D. R., Jayne, J. T., Zhang, Y., Zhu, L., Li, M., Zhou, Z., Cheng, C., Lv, Y., Wang, Y., Peng, W., Xu, X., Lin, N., Wang, Y., Wang, S., Munger, J. W., Jacob, D. J., and McElroy, M. B.: Possible heterogeneous chemistry of hydroxymethanesulfonate (HMS) in northern China winter haze, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 1357–1371, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-1357-2019, 2019.

Suzuki, Y., Kawakami, M., and Akasaka, K.: H-1 NMR application for characterizing water-soluble organic compounds in urban atmospheric particles, Environ. Sci. Technol., 35, 2656–2664, https://doi.org/10.1021/es001861a, 2001.

Tan, Z., Rohrer, F., Lu, K., Ma, X., Bohn, B., Broch, S., Dong, H., Fuchs, H., Gkatzelis, G. I., Hofzumahaus, A., Holland, F., Li, X., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Novelli, A., Shao, M., Wang, H., Wu, Y., Zeng, L., Hu, M., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Wahner, A., and Zhang, Y.: Wintertime photochemistry in Beijing: observations of ROx radical concentrations in the North China Plain during the BEST-ONE campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 12391–12411, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-12391-2018, 2018.

Wang, G. H., Zhang, R. Y., Gomez, M. E., Yang, L. X., Zamora, M. L., Hu, M., Lin, Y., Peng, J. F., Guo, S., Meng, J. J., Li, J. J., Cheng, C. L., Hu, T. F., Ren, Y. Q., Wang, Y. S., Gao, J., Cao, J. J., An, Z. S., Zhou, W. J., Li, G. H., Wang, J. Y., Tian, P. F., Marrero-Ortiz, W., Secrest, J., Du, Z. F., Zheng, J., Shang, D. J., Zeng, L. M., Shao, M., Wang, W. G., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhu, Y. J., Li, Y. X., Hu, J. X., Pan, B., Cai, L., Cheng, Y. T., Ji, Y. M., Zhang, F., Rosenfeld, D., Liss, P. S., Duce, R. A., Kolb, C. E., and Molina, M. J.: Persistent sulfate formation from London Fog to Chinese haze, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 13630–13635, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1616540113, 2016.

Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Jiang, J., Zhou, W., Wang, B., He, K., Duan, F., Zhang, Q., Philip, S., and Xie, Y.: Enhanced sulfate formation during China's severe winter haze episode in January 2013 missing from current models, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 119, 10425–10440, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JD021426, 2014.

Weber, R. J., Guo, H., Russell, A. G., and Nenes, A.: High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years, Nat. Geosci., 9, 282–285, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2665, 2016.

Whiteaker, J. R. and Prather, K. A.: Hydroxymethanesulfonate as a tracer for fog processing of individual aerosol particles, Atmos. Environ., 37, 1033–1043, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1352-2310(02)01029-4, 2003.

Xing, L., Fu, T.-M., Cao, J. J., Lee, S. C., Wang, G. H., Ho, K. F., Cheng, M.-C., You, C.-F., and Wang, T. J.: Seasonal and spatial variability of the OM/OC mass ratios and high regional correlation between oxalic acid and zinc in Chinese urban organic aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 4307–4318, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-4307-2013, 2013.

Xu, L. L., Duan, F. K., He, K. B., Ma, Y. L., Zhu, L. D., Zheng, Y. X., Huang, T., Kimoto, T., Ma, T., Li, H., Ye, S. Q., Yang, S., Sun, Z. L., and Xu, B. Y.: Characteristics of the secondary water-soluble ions in a typical autumn haze in Beijing, Environ. Pollut., 227, 296–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.04.076, 2017.

Yang, W., Li, J., Wang, M., Sun, Y., and Wang, Z.: A Case Study of Investigating Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation Pathways in Beijing using an Observation-based SOA Box Model, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 18, 1606–1616, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2017.10.0415, 2018.

Ye, C., Liu, P., Ma, Z., Xue, C., Zhang, C., Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Liu, C., Sun, X., and Mu, Y.: High H2O2 Concentrations Observed during Haze Periods during the Winter in Beijing: Importance of H2O2 Oxidation in Sulfate Formation, Environ. Sci. Tech. Let., 5, 757–763, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00579, 2018.

Zhang, X., He, S. Z., Chen, Z. M., Zhao, Y., and Hua, W.: Methyl hydroperoxide (CH3OOH) in urban, suburban and rural atmosphere: ambient concentration, budget, and contribution to the atmospheric oxidizing capacity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 8951–8962, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-8951-2012, 2012.

Zhang, Y. J., Cai, J., Wang, S. X., He, K. B., and Zheng, M.: Review of receptor-based source apportionment research of fine particulate matter and its challenges in China, Sci. Total Environ., 586, 917–929, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.071, 2017.

Zhao, B., Wang, S., Donahue, N. M., Jathar, S. H., Huang, X., Wu, W., Hao, J., and Robinson, A. L.: Quantifying the effect of organic aerosol aging and intermediate-volatility emissions on regional-scale aerosol pollution in China, Sci. Rep., 6, 28815, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28815, 2016.

Zheng, B., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Y., He, K. B., Wang, K., Zheng, G. J., Duan, F. K., Ma, Y. L., and Kimoto, T.: Heterogeneous chemistry: a mechanism missing in current models to explain secondary inorganic aerosol formation during the January 2013 haze episode in North China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2031–2049, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2031-2015, 2015.

Zheng, B., Tong, D., Li, M., Liu, F., Hong, C., Geng, G., Li, H., Li, X., Peng, L., Qi, J., Yan, L., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Zheng, Y., He, K., and Zhang, Q.: Trends in China's anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 14095–14111, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-14095-2018, 2018.

Zheng, G. J., Duan, F. K., Su, H., Ma, Y. L., Cheng, Y., Zheng, B., Zhang, Q., Huang, T., Kimoto, T., Chang, D., Pöschl, U., Cheng, Y. F., and He, K. B.: Exploring the severe winter haze in Beijing: the impact of synoptic weather, regional transport and heterogeneous reactions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2969–2983, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2969-2015, 2015.