the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Aerosol pH and its driving factors in Beijing

Jing Ding

Pusheng Zhao

Jie Su

Qun Dong

Xiang Du

Yufen Zhang

Aerosol acidity plays a key role in secondary aerosol formation. The high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 pH and size-resolved aerosol pH in Beijing were calculated with ISORROPIA II. In 2016–2017, the mean PM2.5 pH (at relative humidity (RH) > 30 %) over four seasons was 4.5±0.7 (winter) > 4.4±1.2 (spring) > 4.3±0.8 (autumn) > 3.8±1.2 (summer), showing moderate acidity. In coarse-mode aerosols, Ca2+ played an important role in aerosol pH. Under heavily polluted conditions, more secondary ions accumulated in the coarse mode, leading to the acidity of the coarse-mode aerosols shifting from neutral to weakly acidic. Sensitivity tests also demonstrated the significant contribution of crustal ions to PM2.5 pH. In the North China Plain (NCP), the common driving factors affecting PM2.5 pH variation in all four seasons were , TNH3 (total ammonium (gas + aerosol)), and temperature, while unique factors were Ca2+ in spring and RH in summer. The decreasing and increasing mass fractions in PM2.5 as well as excessive NH3 in the atmosphere in the NCP in recent years are the reasons why aerosol acidity in China is lower than that in Europe and the United States. The nonlinear relationship between PM2.5 pH and TNH3 indicated that although NH3 in the NCP was abundant, the PM2.5 pH was still acidic because of the thermodynamic equilibrium between and NH3. To reduce nitrate by controlling ammonia, the amount of ammonia must be greatly reduced below excessive quantities.

- Article

(5377 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(4921 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Aerosol acidity has a significant effect on secondary aerosol formation through the gas–aerosol partitioning of semi-volatile and volatile species (Eddingsaas et al., 2010; Surratt et al., 2010; Pathak et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2016). Studies have shown that aerosol acidity can promote the generation of secondary organic aerosols by affecting aerosol acid-catalyzed reactions (Rengarajan et al., 2011). Moreover, metals can become soluble by acid dissociation under low aerosol pH (Shi et al., 2011; Meskhidze et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2017) or by forming ligands with organic species, such as oxalate, at higher pH (Schwertmann et al., 1991). The investigation of aerosol acidity is conducive to better understanding the important role of aerosols in acid deposition and atmospheric chemical reactions.

Aerosol acidity is frequently estimated by the charge balance of measurable cations and anions. Nevertheless, not all ions (even trace ones) are well constrained in the observations and the dissociation state of multivalent ions is unclear. Ion balance and other similar proxies fail to represent the in situ aerosol pH because such metrics cannot accurately predict the H+ concentration in the aerosol liquid phase (Guo et al., 2015; Hennigan et al., 2015). To better understand the in situ aerosol pH, the aerosol liquid water content (ALWC) and hydrogen ion concentration per volume air () should be determined (Guo et al., 2015).

Most inorganic ions and some organic acids in aerosols are water soluble (Peng, 2001; Wang et al., 2017). Since the deliquescence relative humidity (DRH) and the efflorescence relative humidity (ERH) of mixed salts are lower than that of any single component, ambient aerosols are generally in the form of droplets containing liquid water (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). ALWC can be derived from hygroscopic growth factors or calculated by thermodynamic models, and good consistencies in ALWC have been found among these methods (Engelhart et al., 2011; Bian et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2015). However, can only be obtained by thermodynamic models, which offer a more precise approach to determine aerosol pH (Nowak et al., 2006; Fountoukis et al., 2009; Weber et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2017). Among these thermodynamic models, ISORROPIA II is widely used owing to its rigorous calculation, performance, and computational speed (Guo et al., 2015; Fang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Galon-Negru et al., 2018).

The North China Plain (NCP) is the region with the most severe aerosol pollution in China. Nitrate and sulfate are the major contributors to haze, and their secondary formation processes are determined in large part by aerosol pH (Zou et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018). Therefore, understanding the aerosol pH level in this region is extremely important and has recently become a trending topic. Fine aerosol pH reported in the NCP (Liu et al., 2017; Song et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017, 2019) was higher than that found in the United States or Europe, where aerosols are often highly acidic with a pH lower than 3.0 (Guo et al., 2015, 2016; Bougiatioti et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2016; Young et al., 2013). The differences in aerosol pH in the NCP arise from (1) different methods or different model settings, (2) variations in PM2.5 chemical composition in the NCP in recent years, (3) the levels of gas precursors of the main water-soluble ions (NH3, HNO3, and HCl), and (4) differences in ambient temperature and RH. Studies demonstrated that pH diurnal variations are largely driven by meteorological conditions (Guo et al., 2015, 2016; Bougiatioti et al., 2016). In the NCP, a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of these factors on aerosol pH is still poor.

Additionally, most studies on aerosol pH focus on PM1 or PM2.5. Knowledge regarding size-resolved aerosol pH is still rare (Fang et al., 2017; Craig et al., 2018). Aerosol chemical compositions are different among multiple size ranges. Among inorganic ions, , , Cl−, K+, and are mainly concentrated in the fine mode except on dusty days (Meier et al., 2009; Pan et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2014), whereas Mg2+ and Ca2+ are abundant in the coarse mode (Zhao et al., 2017). Aerosol pH can be expected to be diverse among different particle sizes; pH levels at different sizes may be associated with different formation pathways of secondary aerosols.

To better understand the driving factors of aerosol acidity, in this work, the thermodynamic model ISORROPIA II was utilized to predict aerosol pH in Beijing based on a long-term online high-temporal-resolution dataset and a size-resolved offline dataset. The hourly measured PM2.5 inorganic ions and precursor gases in four seasons from 2016 to 2017 were used to analyze the seasonal and diurnal variations in aerosol acidity; samples collected by multistage cascade impactors (MOUDI-120) were used to estimate the pH variations among 10 different size ranges. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the key factors affecting aerosol pH and gas–particle partitioning. The main purposes of this work are to (1) obtain the PM2.5 pH level based on an online measurement, contributing towards a global pH dataset; (2) investigate the size-resolved aerosol pH, providing useful information for understanding the formation processes of secondary aerosols; and (3) explore the main factors affecting aerosol pH and gas–particle partitioning, which can help explain the possible reasons for pH divergence in different works and provide a basis for controlling secondary aerosol generation.

2.1 Site

The measurements were performed at the Institute of Urban Meteorology in the Haidian district of Beijing (39∘56′ N, 116∘17′ E). The site is located next to a high-density residential area, without significant nearby air pollution emissions. Therefore, the observation data represent the air quality levels of the urban area of Beijing.

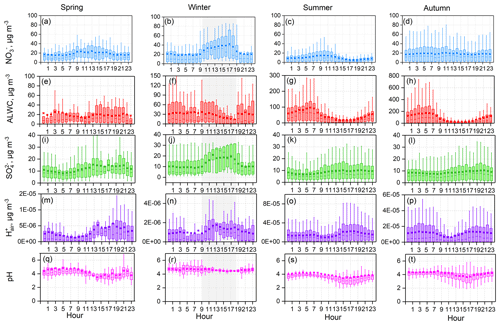

2.2 Online data collection

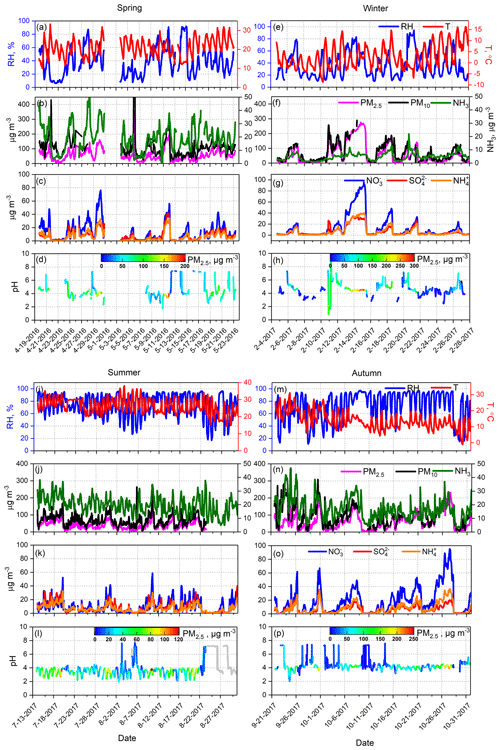

Water-soluble ions (, , Cl−, , Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) in PM2.5 and gaseous precursors (HCl, HNO3, HNO2, SO2, and NH3) in ambient air were measured by an online analyzer (MARGA) with hourly temporal resolution during spring (April and May 2016), winter (February 2017), summer (July and August 2017), and autumn (September and October 2017). More details about MARGA can be found in Rumsey et al. (2014) and Chen et al. (2017). The PM2.5 and PM10 mass concentrations (TEOM 1405-DF), hourly ambient temperature, and RH were also synchronously obtained. The hourly concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, and major secondary ions (, , and ) in PM2.5, as well as meteorological parameters during the observations, are shown in Fig. 1. In the spring, two dust events occurred (21 April and 6 May). In the following pH analysis based on MARGA data, it was assumed that the particles were internally mixed; hence, these two dust events were excluded from this analysis.

2.3 Size-resolved chemical composition

A micro-orifice uniform deposit impactor (MOUDI-120) was used to collect size-resolved aerosol samples with calibrated 50 % cut sizes of 0.056, 0.10, 0.18, 0.32, 0.56, 1.0, 1.8, 3.1, 6.2, 9.9, and 18 µm. Size-resolved sampling was conducted 12–18 July 2013, 13–19 January 2014, 3–5 July 2014, 9–20 October 2014, and 26–28 January 2015. A total of 15, 14, and 18 sets of samples were obtained in summer, autumn, and winter, respectively. Except for two sets of samples, all the samples were collected in daytime (from 08:00 to 19:00 LST) and nighttime (from 20:00 to 07:00 LST the next day). A total of 1 h of preparation time was allowed for filter changing and washing the nozzle plate with ethanol. The water-soluble ions in the samples were analyzed by using ion chromatography (DIONEX ICS-1000). Detailed information about the features of MOUDI-120 and the procedures of sampling, pre-treatment, and laboratory chemical analysis (including quality assurance and quality control) were described in our previous papers (Zhao et al., 2017; Su et al., 2018).

2.4 Aerosol pH prediction

Aerosol pH can be predicted by thermodynamic models such as AIM and ISORROPIA (Clegg et al., 1998; Nenes et al., 1998). AIM is considered an accurate benchmark model, while ISORROPIA has been optimized for use in chemical transport models. Currently, ISORROPIA II, with the addition of K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007), can calculate the equilibrium and ALWC with reasonable accuracy by using the water-soluble ion mass concentration, temperature (T), and RH as input. and ALWC were then used to predict aerosol pH by Eq. (1).

where (mol L−1) is the hydronium ion concentration in the ambient particle liquid water. can also be calculated as (µg m−3) divided by the concentration of ALWC associated with inorganic species, ALWCi (µg m−3). Both the inorganic species and part of the organic species in particles are hygroscopic. However, pH prediction is not highly sensitive to water uptake by organic species (ALWCo) (Guo et al., 2015, 2016). In recent years, the fraction of organic matter in PM2.5 in the NCP was 20 %–25 %, which is much lower than that in the United States (Guo et al., 2015). In contrast, approximately 50 % of PM2.5 in the NCP is inorganic ions (Huang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018, 2019). The results obtained by Liu et al. (2017) in Beijing showed that the mass fraction of organic-matter-induced particle water accounted for only 5 % of total ALWC, indicating a negligible contribution to aerosol pH. Hence, aerosol pH can be fairly well predicted by ISORROPIA II with only measurements of inorganic species in most cases. However, potential errors can be incurred by ignoring ALWCo in regions where hygroscopic organic species have a relatively high contribution to fine particles.

In ISORROPIA II, forward and reverse modes are provided to predict ALWC and . In forward mode, T, RH, and the total (i.e., gas + aerosol) concentrations of NH3, H2SO4, HCl, and HNO3 need to be input. In reverse mode, equilibrium partitioning is calculated given only the concentrations of aerosol components, RH, and T as input. In this work, the online ion chromatography system MARGA was used to measure both inorganic ions in PM2.5 and gaseous precursors. Moreover, the forward mode has been reported to be less sensitive to measurement error than the reverse mode (Hennigan et al., 2015; Song et al., 2018). Hence, ISORROPIA II was run in forward mode for aerosols in the metastable conditions in this study.

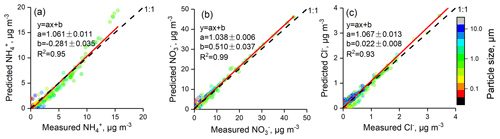

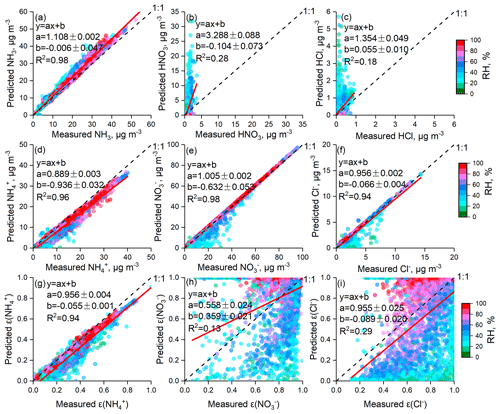

When using ISORROPIA II to calculate the PM2.5 acidity, all particles were assumed to be internally mixed, and the bulk properties were used without considering the variability in chemical composition at a given particle size. In the ambient atmosphere, the aerosol chemical composition is complicated; hence, the deliquescence relative humidity (DRH) of aerosols is generally low (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). Once the particles are deliquescent, crystallization only occurs at a very low RH, which is called the hysteresis phenomenon. The efflorescence RH (ERH) of a salt cannot be calculated from thermodynamic principles; rather, it must be measured in the laboratory. For a particle consisting of approximately 1:1 (NH4)2SO4:NH4NO3, the ERH is around 20 %, while for a 1:2 molar ratio it decreases to around 10 % (Shaw and Rood, 1990). Recently, has dominated the particles in the NCP (Zhao et al., 2013, 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2017); therefore, we assumed that the particles are in a liquid state (metastable condition). Assumptions that particles are metastable were adopted by numerous studies in the NCP (Liu et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017, 2019). Figures 2 and S1–S4 in the Supplement show comparisons between the predicted and measured NH3, HNO3, HCl, , , Cl−, ε() ( ∕ (), mol ∕ mol), ε() ( ∕ (), mol ∕ mol)), and ε(Cl−) (Cl− ∕ (), mol ∕ mol) based on real-time ion chromatography data; all results are colored with the corresponding RH. The predicted and measured NH3, , , and Cl− values are in good agreement: the R2 values of linear regressions are all higher than 0.94, and the slopes are approximately 1. Moreover, the agreement between the predicted and measured ε() is better than that of ε() and ε(Cl−). The slope of the linear regression between the predicted and measured ε() was 0.93, 0.91, 0.95, and 0.96 and R2 was 0.87, 0.93, 0.89, and 0.97 in spring, winter, summer, and autumn, respectively. However, the measured and predicted partitioning of HNO3 and HCl show significant discrepancies (R2 values of 0.28 and 0.18, respectively), which may be attributed to the much lower gas concentrations than particle concentrations, as well as the HNO3 and HCl measurement uncertainties from MARGA (Rumsey et al., 2014). Clearly, more scatter points deviate from the 1:1 line when ISORROPIA II is operated at RH ≤ 30 %, which is highly evident in winter and spring. It should be noted that when RH is low, ALWC becomes very small, and PM2.5 pH is subject to considerably more uncertainty. Guo et al. (2016) suggest that the lower RH limit is about 40 %. In this work, due to the overall good agreement between predictions and measurements when RH was higher than 30 %, we only determined the PM2.5 pH for data with RH higher than 30 %.

Figure 2Comparisons of predicted and measured NH3, HNO3, HCl, , , Cl−, ε(), ε(), and ε(Cl−) colored by RH. In this figure, data from all four seasons were combined; comparisons of individual seasons are shown in Figs. S1–S4 in the Supplement.

Running ISORROPIA II in the forward mode with only aerosol component concentrations as input may result in a bias in predicted pH due to repartitioning of ammonia in the model, leading to a lower predicted pH when gas-phase data are not available (Hennigan et al., 2015). In this work, no synchronous gas phase was available during the MOUDI sampling periods; the gas-phase measurements that were taken by the MARGA in 2017 were therefore applied. Even if the periods were not perfectly aligned, the order of magnitude of NH3, HNO3, and HCl during a certain period did not change drastically. Guo et al. (2017) found that even if there was some error in NH3, pH was less sensitive to it; a change with a factor of 10 in NH3 was required to change pH by 1 unit. Averaged values of NH3, HNO3, and HCl measured by MARGA matched to PM2.5 mass concentration levels during the MOUDI sampling periods. Together with ion concentrations of samples collected by MOUDI, the average RH and T during each sampling period were used to determine the aerosol pH for different size ranges. Similar to calculating the PM2.5 pH, it was assumed that all the particles in each size bin were internally mixed and had the same pH.

Comparisons of the measured and predicted , , and Cl− for MOUDI samples are shown in Fig. 3. The measured and predicted , , and Cl− agreed very well in fine-mode particles; the slopes are approximately 1. In the coarse mode, the predicted was lower than the measured due to the impact of crustal ions.

2.5 Sensitivity of PM2.5 pH to , TNO3, TNH3, Ca2+, RH, and T

To explore the major influencing factors on aerosol pH, sensitivity tests were performed. In the sensitivity analysis, , TNO3 (total nitrate (gas + aerosol) expressed as equivalent HNO3), TNH3 (total ammonium (gas + aerosol) expressed as equivalent NH3), Ca2+, RH, and T were selected as the variables since and are major anions in aerosols, and Ca2+ are major cations in aerosols, and Ca2+ is generally considered representative of crustal ions. To assess how a variable affects PM2.5 pH, the real-time measured values of this variable and the average values of other species (K, Na, Mg, and total chloride (gas + aerosol) were also included) in each season were input into ISORROPIA II. The magnitude of the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the calculated aerosol pH can reflect the impact of variable variations on aerosol acidity. The higher the RSD is, the greater the impact, and vice versa. The average value and variation range for each variable in the four seasons are listed in Table S1 in the Supplement.

The sensitivity analysis in this work was only aimed at PM2.5 (i.e., fine particles) since the MARGA system equipped with a PM2.5 inlet had a high temporal resolution (1 h). In addition, the dataset had a wide range, covering different levels of haze events. The sensitivity analysis in this work only reflected the characteristics during the observation periods, and further work is needed to determine whether the sensitivity analysis is valid in other environments.

3.1 Overall summary of PM2.5 pH over four seasons

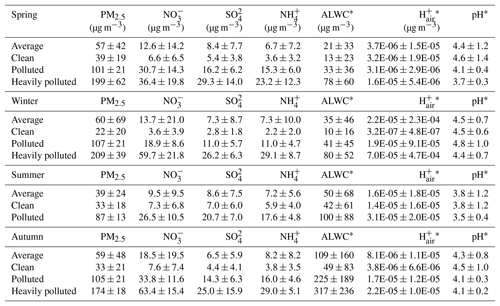

The average mass concentrations of PM2.5 and major inorganic ions in the four seasons are shown in Table 1. Among all the ions measured, , , and were the three most dominant species, accounting for 83 %–87 % of the total ion content. The average concentrations of primary inorganic ions (Cl−, Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) were higher in spring than in other seasons. PM2.5 in Beijing showed moderate acidity, with PM2.5 pH values of 4.4±1.2, 4.5±0.7, 3.8±1.2, and 4.3±0.8 for spring, winter, summer, and autumn observations, respectively (data at RH ≤ 30 % were excluded). The overall winter PM2.5 pH was comparable to the result (4.2) found in Beijing by Liu et al. (2017) and that (4.5) found by Guo et al. (2017), but lower than that (4.9, winter and spring) in Tianjin (Shi et al., 2017), another megacity approximately 120 km away from Beijing. The PM2.5 pH in summer was lowest among all four seasons. The seasonal variation in PM2.5 pH in this work was similar to the results in Tan et al. (2018), except for spring, and followed the trend of winter (4.11±1.37) > autumn (3.13±1.20) > spring (2.12±0.72) > summer (1.82±0.53).

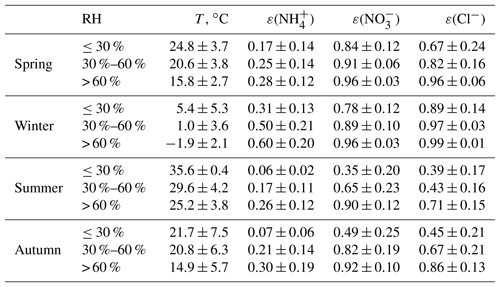

Table 1Average mass concentrations of , , , and PM2.5, as well as ALWC, , and PM2.5 pH, under clean, polluted, and heavily polluted conditions over four seasons.

* For data with RH > 30 %.

To further investigate the PM2.5 pH level under different pollution conditions over four seasons, the PM2.5 concentrations were classified into three groups: 0–75, 75–150, and > 150 µg m−3, representing clean, polluted, and heavily polluted conditions, respectively. The relationship between PM2.5 concentration and pH is shown in Fig. S5. The PM2.5 pH under clean conditions spanned 2–7, while that under polluted and heavily polluted conditions was mostly concentrated from 3 to 5. Table 1 shows that as the air quality deteriorated, the aerosol component concentration as well as ALWC and all increased in each season. The average PM2.5 pH under clean conditions was the highest (Table 1), followed by polluted and heavily polluted conditions in spring, summer, and autumn. In winter, however, the average pH under polluted conditions (4.8±1.0) was the highest.

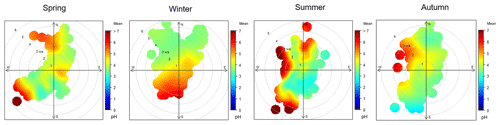

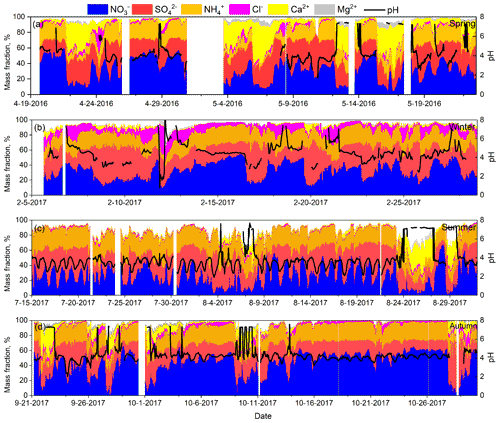

On clean days, some higher PM2.5 pH values (> 6) appeared and were generally accompanied by a higher mass fraction of crustal ions (Mg2+ and Ca2+). In contrast, lower PM2.5 pH (< 3) was often accompanied by a higher mass fraction of and lower mass fraction of crustal ions; such conditions were most obvious in summer (Fig. 4). Under polluted and heavily polluted conditions, the mass fractions of major chemical components were similar, and the difference in PM2.5 pH between these two conditions was also small. All of these results indicated that the aerosol chemical composition should be an essential factor that drives aerosol acidity. The impact of aerosol composition on PM2.5 pH is discussed in Sect. 3.3.

Figure 4Time series of mass fractions of , , , Cl−, Mg2+, and Ca2+ with respect to the total ion content, as well as PM2.5 pH in all four seasons (PM2.5 pH values at RH ≤ 30 % were excluded).

In spring, summer, and autumn, the pH of PM2.5 from the northern direction was generally higher than that from the southwest direction, and the higher pH in summer also occurred with strong southwest winds (wind speed > 3 m s−1) (Fig. 5). Generally, northern winds occur with cold-front systems, which can sweep away air pollutants but raise dust in which the crustal ion species (Ca2+, Mg2+) are higher. In winter, the PM2.5 pH was distributed relatively evenly in all wind directions, but we surprisingly found that the pH in northerly winds on clean days could be as low as 3–4, which was consistent with the high mass fraction of .

3.2 Diurnal variation in ALWC, , and PM2.5 pH

Obvious diurnal variation was observed based on the long-term online dataset, as shown in Fig. 6. To understand the factors that can drive changes in PM2.5 pH, the diurnal variations in , , ALWC, and were investigated and are exhibited in Fig. 6. Generally, ALWC was higher during nighttime than daytime and reached a peak near 04:00–06:00 (local time). After sunrise, the increasing temperature resulted in a rapid drop in RH, leading to a clear loss of particle water, and ALWC reached the lowest level in the afternoon. was highest in the afternoon, followed by nighttime, and was relatively low in the morning. The low ALWC and high values in the afternoon resulted in the minimum PM2.5 pH. The average nighttime pH was 0.3–0.4 units higher than that during daytime. From the above discussion, we found that both and ALWC had significant diurnal variations, which means that in addition to chemical composition, the PM2.5 pH diurnal variation was also affected by meteorological conditions. This trend is slightly different from in the United States: Guo et al. (2015) found that the ALWC diurnal variation was significant and the diurnal pattern in pH was mainly driven by the dilution of aerosol water.

The correlation between concentration and PM2.5 pH was weakly positive at low ALWC, and PM2.5 pH was almost independent of the mass concentration at higher ALWC values (Fig. S6). In contrast, at a low ALWC level, increasing decreased the pH; at a high ALWC level, a negative correlation still existed between mass concentration and PM2.5 pH. had a greater effect than on PM2.5 pH.

Figure 6Diurnal patterns of mass concentrations of and in PM2.5, predicted aerosol liquid water content (ALWC), , and PM2.5 pH over four seasons. Mean and median values are shown, together with 25 % and 75 % quantiles. Data at RH ≤ 30 % were excluded, and the shaded area represents the time period when most RH values were lower than 30 %.

3.3 Factors affecting PM2.5 pH

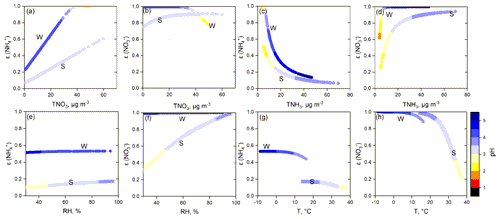

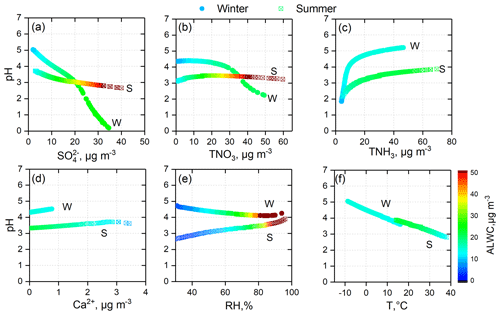

In this work, the effects of , TNO3, TNH3, Ca2+, RH, and T on PM2.5 pH were determined through a four-season sensitivity analysis. The common important driving factors affecting PM2.5 pH variations in all four seasons were , TNH3, and T (Table 2), while the unique influencing factors were Ca2+ in spring and RH in summer. For ALWC, the most important factor was RH, followed by or . Figures 7 and S7–S14 show how these factors affect the PM2.5 pH, ALWC, and over all four seasons.

Table 2Sensitivity of PM2.5 pH to , TNH3, TNO3, Ca2+, RH, and T. A larger magnitude of the relative standard deviation (RSD) represents a larger impact derived from variations in variables.

H2SO4 can be completely dissolved in ALWC and in the form of sulfate. As shown in Table 3, HNO3 also had a high conversion rate to nitrate when RH > 30 %. Under ammonia-rich conditions (defined and explained in Fig. S15), sulfate and nitrate mostly exist in the aerosol phase with ammonium. The thermodynamic equilibrium between and NH3 makes aerosol acidic (Weber et al., 2016). In the sensitivity tests, we found that elevated was crucial in the increase in (Table S2, Figs. S7, S9, S12) and ALWC (Table S2, Figs. S8, S10, S13), and had a key role in aerosol acidity (Figs. 7, S11, S14). However, only the PM2.5 pH in winter and autumn decreased significantly with elevated TNO3 (Figs. 7, S14). In spring and summer, PM2.5 pH changed little with elevated TNO3. When the TNO3 concentration was low, PM2.5 pH even increased with elevated TNO3 (Figs. 7, S11). The effect of TNO3 on and ALWC is similar to that of ; that is, the elevated TNO3 will also result in the increase in and ALWC. The difference is that can lead to a much higher concentration of than TNO3 due to its low volatility (Figs. S7, S9, S12). Thus, the sensitivity of PM2.5 pH to TNO3 is less than that to . Moreover, in spring and summer, more excessive NH3 could continuously react with the increasing TNO3 (Table S1), leading to the minimal changes in PM2.5 pH with elevated TNO3. Differently, TNH3 mass concentration was lower in winter and TNO3 was higher in autumn (Table S1), which made TNH3 not excessive enough and resulted in the decreased PM2.5 pH with elevated TNO3.

In the process of increasing NH3 concentration in the ammonia–nitric acid–sulfuric acid–water system, NH3 first reacts with sulfuric acid and consumes a large amount of H+, and then reacts with HNO3 to produce ammonium nitrate (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). After most nitric acid is converted to ammonium nitrate, it is difficult to dissolve more ammonia into aerosol droplets. The sensitivity tests described this mechanism well. Changes in TNH3 in the lower concentration range had a significant impact on and PM2.5 pH, and variations in TNH3 at higher concentrations could only generate limited pH changes (Figs. 7, S11, S14). The nonlinear relationship between PM2.5 pH and TNH3 indicates that although NH3 in the NCP was abundant, the PM2.5 pH was far from neutral.

Figure 7Sensitivity tests of PM2.5 pH to , TNO3, TNH3, Ca2+, and meteorological parameters (RH and T) in summer (S) and winter (W).

In this work, PM2.5 pH was lowest in summer but highest in winter, which was consistent with the mass fraction with respect to the total ion content. The mass fraction was highest in summer among the four seasons, with a value of 32.4 % ± 11.1 %, but lowest in winter, with a value of 20.9 % ± 4.4 %. In recent years, the mass fraction in PM2.5 in Beijing has decreased significantly due to the strict emission control measures for SO2; in most cases, dominates the inorganic ions (Zhao et al., 2013, 2017; Huang et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2017), which could reduce aerosol acidity. A study in the Pearl River Delta of China showed that the in situ acidity of PM2.5 significantly decreased from 2007 to 2012; the variation in acidity was mainly caused by the decrease in sulfate (Fu et al., 2015). The excessive NH3 in the atmosphere and the high mass fraction in PM2.5 is the reason why the aerosol acidity in China is lower than that in Europe and the United States (Guo et al., 2017).

Ca2+ is an important crustal ion; in the output of ISORROPIA II, Ca exists mainly as CaSO4 (slightly soluble). Elevated Ca2+ concentrations can increase PM2.5 pH by decreasing and ALWC (Figs. 7 and S7–S14). As discussed in Sect. 3.1, on clean days, PM2.5 pH reached 6–7 when the mass fraction of Ca2+ was high; hence, the role of crustal ions in PM2.5 pH cannot be ignored in areas or seasons (such as spring) in which mineral dust is an important particle source. Due to the strict control measures for road dust, construction sites, and other bare ground, the crustal ions in PM2.5 decreased significantly in the NCP, especially on polluted days.

In addition to the particle chemical composition, meteorological conditions also have important impacts on aerosol acidity. RH had different impacts on PM2.5 pH in different seasons (Figs. 7, S11, S14). In winter, elevated RH could reduce PM2.5 pH. However, an opposite tendency was observed in summer. In spring and autumn, RH had little impact on PM2.5 pH. Elevated RH can enhance water uptake and promote gas-to-particle conversion, resulting in increased and ALWC synchronously for all four seasons. Therefore, the effect of RH on PM2.5 pH depends on the differences in the degree of RH's effect on and ALWC. Temperature can alter the PM2.5 pH by affecting gas–particle partitioning. At higher ambient temperatures, ε(), ε(), and ε(Cl−) all showed a decreased tendency (Figs. 8, S16). The volatilization of ammonium nitrate and ammonium chloride can result in a net increase in particle H+ and lower pH (Guo et al., 2018). Moreover, a higher ambient temperature tends to lower ALWC, which can further decrease PM2.5 pH.

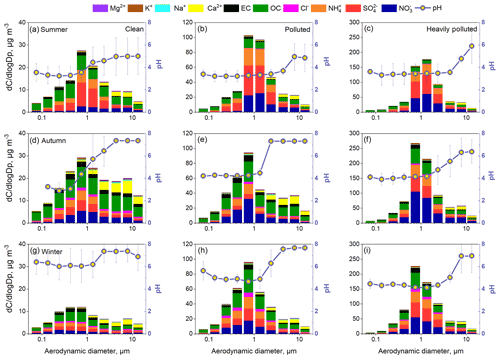

3.4 Size-resolved aerosol pH

Inorganic ions in particles present clear size distributions, and the size-resolved chemical composition can change at different pollution levels (Zhao et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2017, 2018), which may result in variations in aerosol pH. Thus, we further investigated the size-resolved aerosol pH at different pollution levels. According to the average PM2.5 concentration during each sampling period, all the samples were also classified into three groups (clean, polluted, and heavily polluted) according to the rules described in Sect. 3.1. A severe haze episode occurred during the autumn sampling period; hence, there were more heavily polluted samples in autumn than in other seasons. Figure 9 shows the average size distributions of PM components and pH under clean, polluted, and heavily polluted conditions in summer, autumn, and winter. , , , Cl−, K+, organic carbon (OC), and elemental carbon (EC) were mainly concentrated in the size range of 0.32–3.1 µm, while Mg2+ and Ca2+ were predominantly distributed in the coarse mode (> 3.1 µm). During haze episodes, the sulfate and nitrate in the fine mode increased significantly. However, the increases in Mg2+ and Ca2+ in the coarse mode were not as substantial as the increases in , , and , and the low wind speed made it difficult to raise dust during heavily polluted periods. More detailed information about the size distributions for all analyzed species during the three seasons is given in Zhao et al. (2017) and Su et al. (2018).

Figure 9Size distributions of aerosol pH and all analyzed chemical components under clean (a, d, g), polluted (b, e, h), and heavily polluted conditions (c, f, i) in summer, autumn, and winter.

The aerosol pH in both the fine mode and coarse mode was lowest in summer among the three seasons, followed by autumn and winter. The seasonal variation in aerosol pH derived from MOUDI data was consistent with that derived from the real-time PM2.5 dataset. In summer, the predominance of sulfate in the fine mode and high ambient temperature resulted in a low pH, ranging from 3.2 to 3.9. The fine-mode aerosol pH in autumn and winter was in the range of 3.9–5.2 and 4.7–5.7, respectively. The fine-mode aerosol pH was overall comparable to the PM2.5 pH. Moreover, in the fine mode, the difference in aerosol pH among size bins was not significant because the aerosol is in thermodynamic equilibrium with the gas phase (Fang et al., 2017). Additionally, the size distributions of aerosol pH in the daytime and nighttime were explored and are illustrated in Fig. S17. In summer and autumn, the pH in the daytime was lower than that in the nighttime, while in winter, the pH was higher in the daytime. During the winter sampling periods, mass fraction was obviously higher in the nighttime and led to abundant .

The abundance of Ca2+ in the coarse mode led to a predicted aerosol pH approximately at or higher than 7 in autumn and winter. Even if the coarse-mode Ca2+ mass concentration in the summer was low, the coarse-mode aerosol pH was still more than 1 unit higher than the fine-mode aerosol pH. The difference in aerosol pH (with and without Ca2+) increased with increasing particle size above 1 µm (Fig. S18). Moreover, the coarse-mode aerosols during severely hazy days shifted from neutral to weakly acidic, especially in autumn and winter. As shown in Fig. 9, the pH in stage 3 (3.1–6.2 µm) declined from 7.4 (clean) to 5.0 (heavily polluted) in winter. The significant decrease in the mass ratio of Ca2+ in the coarse-mode particles on heavily polluted days resulted in the loss of acid-buffering capacity. The different size-resolved aerosol acidity levels may be associated with different generation pathways of secondary aerosols. According to Cheng et al. (2016) and Wang et al. (2016), the aqueous oxidation of SO2 by NO2 is key in sulfate formation under high-RH and neutral conditions. However, it is speculated that dissolved metals or HONO may be more important for secondary aerosol formation under acidic conditions.

3.5 Factors affecting gas–particle partitioning

Gas–particle partitioning can be directly affected by the concentration levels of gaseous precursors and meteorological conditions. In this work, sensitivity tests showed that decreasing TNO3 lowered ε() effectively, which helped maintain NH3 in the gas phase. Elevated TNH3 can increase ε() when TNO3 is fixed, which means that the elevated TNH3 altered the gas–particle partitioning and shifted more TNO3 into the particle phase, leading to an increase in nitrate (Figs. 8 and S16). Controlling the emissions of both NOx (gaseous precursor of ) and NH3 is an efficient way to reduce . However, the relationship between TNH3 and ε() in the sensitivity tests (Figs. 8 and S16) showed that the ε() response to TNH3 control was highly nonlinear, which means that a decrease in nitrate would happen only when TNH3 is greatly reduced. The same result was also obtained from a study by Guo et al. (2018). The main sources of NH3 emission are agricultural fertilization, livestock, and other agricultural activities, which are all associated with people's livelihoods. Therefore, in terms of controlling the generation of nitrate, a reduction in NOx emissions is more feasible than a reduction in NH3 emissions.

RH and temperature can also alter gas–particle partitioning. The equilibrium constants for solutions of ammonium nitrate or ammonium chloride are functions of T and RH. The measurement data also showed that lower T and higher RH contribute to the conversion of more TNH3, TNO3, and TCl into the particle phase (Table 3). When the RH exceeded 60 %, more than 90 % of TNO3 was in the particle phase for all four seasons. In summer and autumn, more than half of the TNO3 and TCl was partitioned into the gaseous phase at lower RH conditions (≤30 %). In winter, low temperatures favored the existence of and Cl− in the aerosol phase, and ε() and ε(Cl−) were higher than 75 %, even at low RH. ε() was lower than ε() and ε(Cl−). In spring, summer, and autumn, the average ε() was still lower than 0.3 even when the RH was > 60 %; this trend was associated with excess NH3 in the NCP. Higher RH and lower temperature are typical meteorological characteristics of haze events in the NCP (Fig. 1), which are favorable conditions for the formation of secondary particles.

Long-term high-temporal-resolution PM2.5 pH and size-resolved aerosol pH in Beijing were calculated with ISORROPIA II. In 2016–2017 in Beijing, the mean PM2.5 pH (RH > 30 %) over four seasons was 4.5±0.7 (winter) > 4.4±1.2 (spring) > 4.3±0.8 (autumn) > 3.8±1.2 (summer), showing moderate acidity. In this work, both and ALWC had significant diurnal variations, indicating that aerosol acidity in the NCP was driven by both aerosol composition and meteorological conditions. The average PM2.5 nighttime pH was 0.3–0.4 units higher than that in the daytime. The PM2.5 pH in northerly wind was generally higher than that in wind from the southwest. Size-resolved aerosol pH analysis showed that the coarse-mode aerosol pH was approximately equal to or even higher than 7 in winter and autumn, which was considerably higher than the fine-mode aerosol pH. The presence of Ca2+ had a crucial effect on coarse-mode aerosol pH. Under heavily polluted conditions, the mass fractions of Ca2+ in coarse particles decreased significantly, resulting in an evident increase in the coarse-mode aerosol acidity. The PM2.5 pH sensitivity tests also showed that when evaluating aerosol acidity, the role of crustal ions cannot be ignored in areas or seasons (such as spring) where mineral dust is an important particle source. In northern China, dust can effectively buffer aerosol acidity.

The sensitivity tests in this work showed that the common important driving factors affecting PM2.5 pH are , TNH3, and T, while unique influencing factors were Ca2+ in spring and RH in summer. Owing to the significantly rich NH3 in the atmosphere, the change in PM2.5 pH was not significant with the elevated TNO3, especially in spring and summer. Excess NH3 in the atmosphere and a high mass fraction in PM2.5 is the reason why aerosol acidity in China is lower than that in Europe and the United States. Notably, TNH3 had a great influence on aerosol acidity at lower concentrations but had a limited influence on PM2.5 pH when present in excess. The nonlinear relationship between PM2.5 pH and TNH3 indicated that although NH3 in the NCP was abundant, the PM2.5 pH was still acidic due to the thermodynamic equilibrium between aerosol droplet and precursor gases. Higher ambient temperature could reduce the PM2.5 pH by increasing ammonium evaporation and decreasing ALWC. RH had different impacts on PM2.5 pH in different seasons, which depends on the differences in the degree of RH's effects on and ALWC.

In recent years, nitrates have dominated PM2.5 in the NCP, especially on heavily polluted days. Sensitivity tests showed that decreasing TNO3 and TNH3 could lower ε() and ε(), helping to reduce nitrate production. However, the ε() response to TNH3 control was highly nonlinear. Given that ammonia was excessive in most cases, a decrease in nitrate would occur only if TNH3 were greatly reduced. Therefore, in terms of controlling the generation of nitrate, a reduction in NOx emissions is more feasible than a reduction in NH3 emissions.

All data in this work are available by contacting the corresponding author P. S. Zhao (pszhao@ium.cn).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-7939-2019-supplement.

PZ designed and led this study. PZ was responsible for all observations and data collection. JD, PZ, and YZ interpreted the data and discussed the results. JS and XD analyzed the chemical compositions of size-resolved aerosol samples. JD and PZ wrote the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41675131), the Beijing Talents Fund (2014000021223ZK49), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (8131003). Special thanks are extended to the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry and Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research where Pusheng Zhao visited as a guest scientist in 2018.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 41675131), the Beijing Talents Fund (grant no. 2014000021223ZK49), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 8131003).

This paper was edited by Athanasios Nenes and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Bian, Y. X., Zhao, C. S., Ma, N., Chen, J., and Xu, W. Y.: A study of aerosol liquid water content based on hygroscopicity measurements at high relative humidity in the North China Plain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 6417–6426, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-6417-2014, 2014.

Bougiatioti, A., Nikolaou, P., Stavroulas, I., Kouvarakis, G., Weber, R., Nenes, A., Kanakidou, M., and Mihalopoulos, N.: Particle water and pH in the eastern Mediterranean: source variability and implications for nutrient availability, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 4579–4591, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-4579-2016, 2016.

Chen, X., Walker, J. T., and Geron, C.: Chromatography related performance of the Monitor for AeRosols and GAses in ambient air (MARGA): laboratory and field-based evaluation, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 10, 3893–3908, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-3893-2017, 2017.

Cheng, Y. F., Zheng, G. J., Wei C., Mu, Q., Zheng, B., Wang, Z. B., Gao, M., Zhang, Q., He, K. B., Carmichael, G., Pöschl, U., and Su, H.: Reactive nitrogen chemistry in aerosol water as a source of sulfate during haze events in China, Sci. Adv., 2, e1601530, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601530, 2016.

Clegg, S. L., Brimblecombe, P., and Wexler, A. S.: A thermodynamic model of the system H+, , , , H2O at tropospheric temperatures, J. Phys. Chem., 102, 2137–2154, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp973042r, 1998.

Craig, R. L., Peterson, P. K., Nandy, L., Lei, Z., Hossain, M. A., Camarena, S., Dodson, R. A., Cook, R. D., Dutcher, C. S., and Ault, A. P.: Direct determination of aerosol pH: size-Resolved measurements of submicrometer and supermicrometer aqueous particles, Anal. Chem., 90, 11232–11239, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00586, 2018.

Ding, J., Zhang, Y. F., Han, S. Q., Xiao, Z. M., Wang, J., and Feng, Y. C.: Chemical, optical and radiative characteristics of aerosols during haze episodes of winter in the North China Plain, Atmos. Environ., 181, 164–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.03.006, 2018.

Ding, X. X., Kong, L. D., Du, C. T., Zhanzakova, A., Fu, H. B., Tang, X. F., Wang, L., Yang, X., Chen, J. M., and Cheng, T. T.: Characteristics of size-resolved atmospheric inorganic and carbonaceous aerosols in urban Shanghai, Atmos. Environ., 167, 625–641, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.08.043, 2017.

Eddingsaas, N. C., VanderVelde, D. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Kinetics and products of the acid-catalyzed ring-opening of atmospherically relevant butyl epoxy alcohols, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 8106–8113, https://doi.org/10.1021/Jp103907c, 2010.

Engelhart, G. J., Hildebrandt, L., Kostenidou, E., Mihalopoulos, N., Donahue, N. M., and Pandis, S. N.: Water content of aged aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 911–920, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-911-2011, 2011.

Fang, T., Guo, H. Y., Zeng, L. H., Verma, V., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Highly acidic ambient particles, soluble metals, and oxidative potential: A link between sulfate and aerosol toxicity, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 2611–2620, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06151, 2017.

Fountoukis, C. and Nenes, A.: ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+-Ca2+-Mg2+--Na+---Cl−-H2O aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 4639-4659, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007, 2007.

Fountoukis, C., Nenes, A., Sullivan, A., Weber, R., Van Reken, T., Fischer, M., Matías, E., Moya, M., Farmer, D., and Cohen, R. C.: Thermodynamic characterization of Mexico City aerosol during MILAGRO 2006, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2141–2156, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2141-2009, 2009.

Fu, X., Guo, H., Wang, X., Ding, X., He, Q., Liu, T., and Zhang, Z.: PM2.5 acidity at a background site in the Pearl River Delta region in fall-winter of 2007-2012, J. Hazard. Mater., 286, 484–492, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.01.022, 2015.

Gao, J. J., Wang, K., Wang, Y., Liu, S. H., Zhu, C. Y., Hao, J. M., Liu, H. J., Hua, S. B., and Tian, H. Z.: Temporal-spatial characteristics and source apportionment of PM2.5 as well as its associated chemical species in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China, Environ. Pollut., 233, 714–724, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.02.022, 2018.

Galon-Negru, A. G., Olariu, R. I., and Arsene, C.: Chemical characteristics of size-resolved atmospheric aerosols in Iasi, north-eastern Romania: nitrogen-containing inorganic compounds control aerosol chemistry in the area, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 5879–5904, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-5879-2018, 2018.

Guo, H., Xu, L., Bougiatioti, A., Cerully, K. M., Capps, S. L., Hite Jr., J. R., Carlton, A. G., Lee, S.-H., Bergin, M. H., Ng, N. L., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine-particle water and pH in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5211–5228, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5211-2015, 2015.

Guo, H. Y., Sullivan, A. P., Campuzano-Jost, P., Schroder, J. C., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Dibb, J. E., Jimenez, J. L., Thornton, J. A., Brown, S. S., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine particle pH and the partitioning of nitric acid during winter in the northeastern United States, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 121, 10355–10376, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025311, 2016.

Guo, H. Y., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: High levels of ammonia do not raise fine particle pH sufficiently to yield nitrogen oxide-dominated sulfate production, Sci. Rep., 7, 12109, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11704-0, 2017.

Guo, H., Otjes, R., Schlag, P., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Effectiveness of ammonia reduction on control of fine particle nitrate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 12241–12256, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-12241-2018, 2018.

Hennigan, C. J., Izumi, J., Sullivan, A. P., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: A critical evaluation of proxy methods used to estimate the acidity of atmospheric particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2775–2790, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2775-2015, 2015.

Huang, X., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Hu, B., Wen, T., Tang, G., Zhang, J., Wu, F., Ji, D., Wang, L., and Wang, Y.: Chemical characterization and source identification of PM2.5 at multiple sites in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 12941–12962, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-12941-2017, 2017.

Liu, M. X., Song, Y., Zhou, T., Xu, Z. Y., Yan, C. Q., Zheng, M., Wu, Z. J., Hu, M., Wu, Y. S., and Zhu, T.: Fine particle pH during severe haze episodes in northern China, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 5213–5221, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073210, 2017.

Ma, Q. X., Wu, Y. F., Zhang, D. Z., Wang, X. J., Xia, Y. J., Liu, X. Y., Tian, P., Han, Z. W., Xia, X. G., Wang, Y., and Zhang, R. J.: Roles of regional transport and heterogeneous reactions in the PM2.5 increase during winter haze episodes in Beijing, Sci. Total Environ., 599–600, 246–253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.193, 2017.

Meier, J., Wehner, B., Massling, A., Birmili, W., Nowak, A., Gnauk, T., Brüggemann, E., Herrmann, H., Min, H., and Wiedensohler, A.: Hygroscopic growth of urban aerosol particles in Beijing (China) during wintertime: a comparison of three experimental methods, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 6865–6880, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-6865-2009, 2009.

Meskhidze, N., Chameides, W. L., Nenes, A., and Chen, G.: Iron mobilization in mineral dust: Can anthropogenic SO2 emissions affect ocean productivity?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, 2085, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003gl018035, 2003.

Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., and Pilinis, C.: ISORROPIA: A new thermodynamic equilibrium model for multiphase multicomponent inorganic aerosols, Aquat. Geochem., 4, 123–152, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009604003981, 1998.

Nowak, J. B., Huey, L. G., Russell, A. G., Tian, D., Neuman, J. A., Orsini, D., Sjostedt, S. J., Sullivan, A. P., Tanner, D. J., Weber, R. J., Nenes, A., Edgerton, E., and Fehsenfeld, F. C.: Analysis of urban gas phase ammonia measurements from the 2002 Atlanta Aerosol Nucleation and Real-Time Characterization Experiment (ANARChE), J. Geophys. Res., 111, D17308, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007113, 2006.

Pan, X. L., Yan, P., Tang, J., Ma, J. Z., Wang, Z. F., Gbaguidi, A., and Sun, Y. L.: Observational study of influence of aerosol hygroscopic growth on scattering coefficient over rural area near Beijing mega-city, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 7519–7530, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-7519-2009, 2009.

Pathak, R. K., Wang, T., Ho, K. F., and Lee, S. C.: Characteristics of summertime PM2.5 organic and elemental carbon in four major Chinese cities: Implications of high acidity for water soluble organic carbon (WSOC), Atmos. Environ., 45, 318–325, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.10.021, 2011.

Peng, C. G., Chan, M. N., and Chan, C. K.: The hygroscopic properties of dicarboxylic and multifunctional acids: Measurements and UNIFAC predictions, Environ. Sci. Technol., 35, 4495–4501, https://doi.org/10.1021/es0107531, 2001.

Rengarajan, R., Sudheer, A. K., and Sarin, M. M.: Aerosol acidity and secondary formation during wintertime over urban environment in western India, Atmos. Environ., 45, 1940–1945, 2011.

Rumsey, I. C., Cowen, K. A., Walker, J. T., Kelly, T. J., Hanft, E. A., Mishoe, K., Rogers, C., Proost, R., Beachley, G. M., Lear, G., Frelink, T., and Otjes, R. P.: An assessment of the performance of the Monitor for AeRosols and GAses in ambient air (MARGA): a semi-continuous method for soluble compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 5639–5658, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-5639-2014, 2014.

Schwertmann, U. and Cornell, R. M.: Iron Oxides In the Laboratory: Preparation and Characterization, WCH Publisher, Weinheim, https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527613229, 1991.

Seinfeld, J. H. and Pandis, S. N.: Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change (3rd edition), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2016.

Shaw, M. A. and Rood, M. J.: Measurement of the crystallization humidities of ambient aerosol particles, Atmos. Environ., 24, 1837–1841, 1990.

Shi, G. L., Xu, J., Peng, X., Xiao, Z. M., Chen, K., Tian, Y. Z., Guan, X. P., Feng, Y. C., Yu, H. F., Nenes, A., and Russell, A. G.: pH of aerosols in a polluted atmosphere: source contributions to highly acidic aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 4289–4296, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b05736, 2017.

Shi, X. R., Nenes, A., Xiao, Z. M., Song, S. J., Yu, H. F., Shi, G. L., Zhao, Q. Y., Chen, K., Feng, Y. C., and Russell, A. G.: High-resolution data sets unravel the effects of sources and meteorological conditions on nitrate and its gas-particle partitioning, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 3048–3057, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06524, 2019.

Shi, Z., Bonneville, S., Krom, M. D., Carslaw, K. S., Jickells, T. D., Baker, A. R., and Benning, L. G.: Iron dissolution kinetics of mineral dust at low pH during simulated atmospheric processing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 995–1007, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-995-2011, 2011.

Song, S., Gao, M., Xu, W., Shao, J., Shi, G., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., and McElroy, M. B.: Fine-particle pH for Beijing winter haze as inferred from different thermodynamic equilibrium models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7423–7438, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7423-2018, 2018.

Su, J., Zhao, P. S., and Dong, Q.: Chemical Compositions and Liquid Water Content of Size-Resolved Aerosol in Beijing, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 18, 680–692, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2017.03.0122, 2018.

Surratt, J. D., Chan, A. W., Eddingsaas, N. C., Chan, M., Loza, C. L., Kwan, A. J., Hersey, S. P., Flagan, R. C., Wennberg, P. O., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Reactive intermediates revealed in secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 6640–6645, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0911114107, 2010.

Tan, T. Y., Hu, M., Li, M. R., Guo, Q. F., Wu, Y. S., Fang, X., Gu, F. T., Wang, Y., and Wu, Z. J.: New insight into PM2.5 pollution patterns in Beijing based on one-year measurement of chemical compositions, Sci. Total Environ., 621, 734–743, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.208, 2018.

Tian, S. L., Pan, Y. P., Liu, Z. R., Wen, T. X., and Wang, Y. S.: Size-resolved aerosol chemical analysis of extreme haze pollution events during early 2013 in urban Beijing, China, J. Hazard. Mater., 279, 452–460, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.07.023, 2014.

Wang, G., Zhang, R., Gomez, M. E., Yang, L., Levy Zamora, M., Hu, M., Lin, Y., Peng, J., Guo, S., Meng, J., Li, J., Cheng, C., Hu, T., Ren, Y., Wang, Y., Gao, J., Cao, J., An, Z., Zhou, W., Li, G., Wang, J., Tian, P., Marrero-Ortiz, W., Secrest, J., Du, Z., Zheng, J., Shang, D., Zeng, L., Shao, M., Wang, W., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhu, Y., Li, Y., Hu, J., Pan, B., Cai, L., Cheng, Y., Ji, Y., Zhang, F., Rosenfeld, D., Liss, P. S., Duce, R. A., Kolb, C. E., and Molina, M. J.: Persistent sulfate formation from London Fog to Chinese haze, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 13630–13635, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1616540113, 2016.

Wang, X., Jing, B., Tan, F., Ma, J., Zhang, Y., and Ge, M.: Hygroscopic behavior and chemical composition evolution of internally mixed aerosols composed of oxalic acid and ammonium sulfate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 12797–12812, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-12797-2017, 2017.

Weber, R. J., Guo, H., Russell, A. G., and Nenes, A.: High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years, Nat. Geosci., 9, 282–285, https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2665, 2016.

Young, A. H., Keene, W. C., Pszenny, A. A. P., Sander, R., Thornton, J. A., Riedel, T. P., and Maben, J. R.: Phase partitioning of soluble trace gases with size-resolved aerosols in near-surface continental air over northern Colorado, USA, during winter, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 9414–9427, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50655, 2013.

Zhang, H., Cheng, S., Li, J., Yao, S., and Wang, X.: Investigating the aerosol mass and chemical components characteristics and feedback effects on the meteorological factors in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China, Environ. Pollut., 244, 495–502, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.087, 2019.

Zhang, Y., Lang, J., Cheng, S., Li, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, D., Zhang, H., and Wang, H.: Chemical composition and sources of PM1 and PM2.5 in Beijing in autumn, Sci. Total Environ., 630, 72–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.151, 2018.

Zhao, P. S., Dong, F., He, D., Zhao, X. J., Zhang, X. L., Zhang, W. Z., Yao, Q., and Liu, H. Y.: Characteristics of concentrations and chemical compositions for PM2.5 in the region of Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 4631–4644, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-4631-2013, 2013.

Zhao, P. S., Chen, Y. N., and Su, J.: Size-resolved carbonaceous components and water-soluble ions measurements of ambient aerosol in Beijing, J. Environ. Sci., 54, 298–313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2016.08.027, 2017.

Zou, J. N., Liu, Z. R., Hu, B., Huang, X. J., Wen, T. X., Ji, D. S., Liu, J. Y., Yang, Y., Yao, Q., and Wang, Y. S.: Aerosol chemical compositions in the North China Plain and the impact on the visibility in Beijing and Tianjin, Atmos. Res., 201, 235–246, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2017.09.014, 2018.