the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Low levels of nitryl chloride at ground level: nocturnal nitrogen oxides in the Lower Fraser Valley of British Columbia

Charles A. Odame-Ankrah

Youssef M. Taha

Travis W. Tokarek

Corinne L. Schiller

Donna Haga

Keith Jones

Roxanne Vingarzan

The nocturnal nitrogen oxides, which include the nitrate radical (NO3), dinitrogen pentoxide (N2O5), and its uptake product on chloride containing aerosol, nitryl chloride (ClNO2), can have profound impacts on the lifetime of NOx (= NO + NO2), radical budgets, and next-day photochemical ozone (O3) production, yet their abundances and chemistry are only sparsely constrained by ambient air measurements.

Here, we present a measurement data set collected at a routine monitoring site near the Abbotsford International Airport (YXX) located approximately 30 km from the Pacific Ocean in the Lower Fraser Valley (LFV) on the west coast of British Columbia. Measurements were made from 20 July to 4 August 2012 and included mixing ratios of ClNO2, N2O5, NO, NO2, total odd nitrogen (NOy), O3, photolysis frequencies, and size distribution and composition of non-refractory submicron aerosol (PM1).

At night, O3 was rapidly and often completely removed by dry deposition and by titration with NO of anthropogenic origin and unsaturated biogenic hydrocarbons in a shallow nocturnal inversion surface layer. The low nocturnal O3 mixing ratios and presence of strong chemical sinks for NO3 limited the extent of nocturnal nitrogen oxide chemistry at ground level. Consequently, mixing ratios of N2O5 and ClNO2 were low (< 30 and < 100 parts-per-trillion by volume (pptv) and median nocturnal peak values of 7.8 and 7.9 pptv, respectively). Mixing ratios of ClNO2 frequently peaked 1–2 h after sunrise rationalized by more efficient formation of ClNO2 in the nocturnal residual layer aloft than at the surface and the breakup of the nocturnal boundary layer structure in the morning. When quantifiable, production of ClNO2 from N2O5 was efficient and likely occurred predominantly on unquantified supermicron-sized or refractory sea-salt-derived aerosol. After sunrise, production of Cl radicals from photolysis of ClNO2 was negligible compared to production of OH from the reaction of O(1D) + H2O except for a short period after sunrise.

- Article

(2976 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(948 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The Lower Fraser Valley (LFV) is prone to episodes of poor air quality, in part because of its geography, which facilitates stagnation periods and accumulation of airborne pollutants through processes such as the Wake-Induced Stagnation Effect (Brook et al., 2004), and also because of continued growth of human population and associated emissions from urban, suburban, agricultural, and marine sources. Of special concern have been repeated exceedances of the Canada-wide standard and, as of 2012, the Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standards (CAAQS) for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone (O3) at Chilliwack and Hope, located in the eastern part of the LFV downwind of Vancouver (Ainslie et al., 2013). These exceedances have occurred in spite of ongoing declines in emissions of both nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) resulting from the introduction of new vehicle standards and (now discontinued) local vehicle emission testing programs (Ainslie et al., 2013). Previous large-scale studies in the LFV such as Pacific 1993 (Steyn et al., 1997), the Regional Visibility Experimental Assessment in the Lower Fraser Valley (REVEAL) I and II (Pryor et al., 1997; Pryor and Barthelmie, 2000), and Pacific 2001 (Vingarzan and Li, 2006) have added important information regarding atmospheric processes, leading to O3 and aerosol formation and visibility issues. However, the transformation of primary (e.g., NOx, VOCs, SO2, NH3) to secondary pollutants (i.e., O3 and fine particulate matter) is highly complex, and the scientific understanding of these highly non-linear processes remains incomplete.

A complicating factor in the LFV is the interaction of anthropogenic emissions with marine-derived sea salt aerosol. While sea spray aerosol is a primary source of particulate matter (PM) and hence directly affects particle concentrations and mass loadings (Pryor et al., 2008) and aerosol chloride concentrations (Anlauf et al., 2006) in the LFV, there is now considerable evidence from modelling (Knipping and Dabdub, 2003), laboratory (Raff et al., 2009), and field studies (Tanaka et al., 2003; Osthoff et al., 2008) that “active chlorine” species released from sea salt can negatively affect air quality and promote O3 and secondary aerosol formation in coastal regions.

In an analysis of 20 years of O3 air quality data in the LFV region, Ainslie and Steyn (2007) concluded that precursor buildup, prior to an exceedance day, plays an important role in the spatial O3 pattern on exceedance days. Secondary processes involving active chlorine produced from the interaction of marine aerosol with anthropogenic pollution would fit this profile but are not currently constrained by measurements.

One pathway to activate chlorine from sea salt is the reactive uptake of dinitrogen pentoxide (N2O5) on chloride containing aerosol to yield nitryl chloride (ClNO2) (Behnke et al., 1997; Finlayson-Pitts et al., 1989). Briefly, N2O5 is formed from the reversible reaction of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) with the photolabile nitrate radical (NO3; Reaction R1), which in turn is formed from reaction of NO2 with O3 (Reaction R2).

In ambient air, N2O5, NO3, and NO2 are usually in equilibrium; the equilibrium constant, K2, is temperature dependent, favouring NO3 and NO2 at higher temperatures (Osthoff et al., 2007). During daytime, NO3 (and, indirectly, N2O5) is removed primarily via its Reaction (R3) with NO (which is generated from NO2 photolysis and directly emitted, for example, by automobiles) and by NO3 photolysis (Reaction R4) (Wayne et al., 1991).

The heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 to nitric acid (HNO3) is an important nocturnal NOx and odd oxygen (Ox = NO2 + O3) removal pathway (Chang et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2006a). On chloride containing aerosol, however, uptake of N2O5 yields up to a stoichiometric amount of ClNO2 (Reaction R5) (Behnke et al., 1997; Finlayson-Pitts et al., 1989):

The ClNO2 yield, φ, is primarily a function of aerosol chloride and water content (Behnke et al., 1997; Bertram and Thornton, 2009; Roberts et al., 2009; Ryder et al., 2014, 2015). Formation of ClNO2 impacts air quality in the following ways: since ClNO2 is long-lived at night, its primary fate is photodissociation (to Cl and NO2) in the morning hours after sunrise (Reaction R6) (Osthoff et al., 2008).

This reaction increases the morning abundance of Ox, leading to greater net photochemical O3 production throughout the day. The other photo-fragment, the Cl atom, is highly reactive towards hydrocarbons and will initiate radical chain reactions that produce O3 and secondary aerosol (Behnke et al., 1997; Young et al., 2014). The fate and impact of ClNO2 is thus similar to that of nitrous acid (HONO), which also accumulates during the night and photodissociates in the morning to release NO and the hydroxyl radical (OH) that go on to produce O3 (Alicke et al., 2003).

Data collected during the 2006 Texas Air Quality Study – Gulf of Mexico Atmospheric Composition and Climate Study (TEXAQS-GOMACCS) have shown that ClNO2 production is efficient in the nocturnal polluted marine boundary layer even on primarily non-sea-salt aerosol surfaces (Osthoff et al., 2008). As a result, up to 15 % of total odd nitrogen (NOy) was present in the form ClNO2 at night (Osthoff et al., 2008). The high efficiency of ClNO2 formation on aerosol of medium-to-low total chloride content has been confirmed by several laboratory investigations (Bertram and Thornton, 2009; Raff et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2009) and direct measurements of N2O5 uptake on ambient particles (Riedel et al., 2012b). Some ambiguity remains as to the detailed mechanism of Reaction (R5), but there is agreement that acid displacement of HCl from supermicron (predominantly sea salt aerosol) to submicron (predominantly non-sea-salt aerosol) is a key step in the efficient production of ClNO2. These results suggested that this chemistry is active anywhere that pollution in the form of NOx and O3 comes in contact with marine air, including the LFV.

However, while the yield of ClNO2 in Reaction (R5) is high in polluted coastal regions, the ClNO2 yield relative to the amount of NO3 produced via Reaction (R1) cannot be easily predicted because NO3 is consumed by reactions with VOCs (Reaction R7), e.g., with biogenic VOCs such as isoprene and monoterpenes as well as aldehydes, and dimethyl sulfide (Wayne et al., 1991).

Previous studies in the LFV have shown high biogenic VOC concentrations (Biesenthal et al., 1997; Gurren et al., 1998; Drewitt et al., 1998) yet there was active nighttime nitrogen oxide chemistry and aerosol chloride present mainly as sea-salt-derived aerosol in > 1 µm diameter aerosol (Anlauf et al., 2006). During the Pacific 2001 study, measurements of the mixing ratios of NO, NO2, peroxyacetic nitric anhydride (CH3C(O)O2NO2, PAN), HONO, HNO3, and NOy at three ground sites in the LFV indicated deficits of up to 15 % in the nocturnal NOy budget (Hayden et al., 2004) attributable to unquantified species such as alkyl nitrates, N2O5, and ClNO2. McLaren and coworkers quantified mixing ratios of NO2 and NO3 by differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) at the Sumas Eagle Ridge site (∼ 250 m above the floor of the LFV) as part of Pacific 2001 (McLaren et al., 2004) and off-shore on Saturna Island (Fig. 1) in the Strait of Georgia in 2005 (McLaren et al., 2010). The LFV data showed occasional episodes of active nocturnal nitrogen oxide chemistry in the residual layer with N2O5 contributing up to 9 % of NOy, while the Saturna Island data showed NO3 mixing ratios of > 20 parts-per-trillion by volume (10−12 pptv) every night of measurement. McLaren et al. (2010) estimated that between 0.3 and 1.9 ppbv of ClNO2 would be produced under these conditions. Efficient formation of ClNO2 would be consistent with the unidentified O3 precursor proposed by Ainslie and Steyn and is also a plausible explanation for part of the deficit in the NOy budget observed by Hayden et al. (2004).

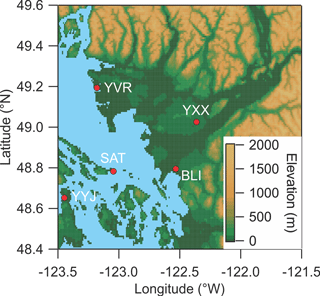

Figure 1Map of the Lower Fraser Valley. YXX is the Abbotsford International Airport (measurement location for this study). YVR is the Vancouver International Airport. YYJ is the Victoria International Airport. BLI is the Bellingham International Airport. SAT is Saturna Island.

Another feature of the LFV are somewhat unusual diurnal profiles arising from the vertical structure in pollutant concentrations. Measurements of O3 and NO2 using tethered balloons by Pisano et al. (1997) during Pacific 93 at the Harris Road site (located ∼ 38 km NW of Abbotsford International Airport) revealed a highly stratified boundary layer with a shallow, 50 m deep isothermal surface layer (also called a nocturnal boundary layer, or NBL) and low surface O3 concentrations at night. Nocturnal loss of surface O3 is known to occur by several pathways, including dry deposition, titration with NO (Reaction R8), and reaction with unsaturated biogenic hydrocarbons (Neu et al., 1994; Kleinman et al., 1994; Trainer et al., 1987; Logan, 1989; Talbot et al., 2005). Titration of O3 with NO is readily quantified as the concentration of a product of Reaction (R8), NO2, can be measured directly and conserves Ox.

Usually, the major nocturnal sink of Ox is dry deposition of O3 and NO2 (Lin et al., 2010).

The balloon data also showed pools of NO2 and O3 in a ∼ 100 m deep nocturnal residual layer (NRL) located 200 to 350 m above ground. Following the breakup of the nocturnal layers in the early morning, vertical down-mixing events of O3 pollution were observed (McKendry et al., 1997). In this process, pollutants are entrained into the growing mixed layer from the NRL, i.e., the growing mixed layer in the hours after sunrise erodes the somewhat deeper NRL, and pollutants are mixed to the surface (Neu et al., 1994; Kleinman et al., 1994).

In this paper, we present the first measurements of ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios in the LFV. The data were collected at a surface site east of the Abbotsford International Airport (International Air Transport Association (IATA) airport code YXX) located approximately 35 km from the Pacific Ocean from 20 July to 5 August, 2012. Auxiliary measurements included NO, NO2, NOy, O3, photolysis frequencies, and non-refractory PM1 aerosol composition and size distributions. An analysis of nocturnal nitrogen oxide chemistry including the formation of ClNO2 and its potential impact on nocturnal O3 and NO2 loss and radical budgets in the LFV are presented.

2.1 Location

The map shown in Fig. 1 indicates the location of the study. Ambient air measurements were conducted at the T45 routine monitoring site located to the east YXX at latitude 49.0212 (N) and longitude −122.3267 (W) and ∼ 60 m above sea level (a.s.l.) and ∼ 30 km from the Pacific Ocean. A raspberry field was located immediately to the W between the end of the airport runway and the measurement site. Nearby local sources included agricultural operations (such as poultry farms) and emissions from motor vehicle traffic on secondary roads and highways. YXX is located ∼ 60 km ESE of the Vancouver International Airport (YVR) and the City of Vancouver. Abbotsford is in the heart of the so-called “lower mainland”, the low-lying region stretching from the Pacific Ocean at Vancouver to the NW and the Canada–USA border to the S (north of Bellingham, BLI) to the eastern end of the Fraser Valley, with a total population in excess of 2 500 000.

2.2 Measurement techniques

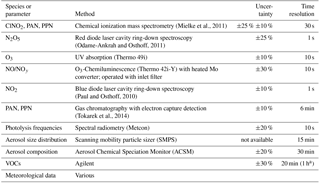

The measurement techniques used for this study are listed in Table 1. Data were averaged to 5 min prior to presentation.

Table 1Summary of measurement techniques deployed at T45 during the study.

a Sampled for 20 min within a 1 h time period.

The instruments measuring O3 and nitrogen oxides were housed in an air-conditioned trailer and sampled from a common 0.635 cm (1/4 in.) outer diameter (OD) and 0.476 cm (3/16 in.) inner diameter (ID) Teflon™ inlet at a height of 4 m above ground; the setup is depicted in Fig. 3 of Tokarek et al. (2014). A scroll pump whose flow rate was throttled using a 50 standard litres per minute (slpm) capacity mass flow controller was connected to the end of the common inlet to minimize the residence time of the sampled air and to reduce inlet “aging”, i.e., accumulation of aerosol on filters of individual instruments, whose inlets tapped into the main inlet line at 90∘. The total inlet flow was in the range of 18 to 20 slpm.

Measurements of PM1 aerosol composition and size distributions (Sect. 2.3) and of meteorological data were made from the research trailer housing the routine measurements at the site. The Agilent VOC measurements were made from a research trailer owned by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

2.2.1 Quantification of ClNO2 by iodide chemical ionization mass spectrometry

Mixing ratios of ClNO2 were quantified as iodide cluster ions at m∕z 208 using the THS Instruments iodide chemical ionization mass spectrometer (iCIMS) described by Mielke et al. (2011) and calibrated using the scheme by Thaler et al. (2011). In this method, a gas stream containing ClNO2 is generated from reaction of Cl2 (Praxair, 10 ppmv in N2) with an aqueous slurry saturated with NaNO2 (Sigma-Aldrich) (Reaction R9):

This gas stream was periodically added to the main inlet with the aid of a normally open two-way valve connected to a vacuum pump in a similar fashion as described earlier for N2O5 and PAN (Tokarek et al., 2014; Odame-Ankrah and Osthoff, 2011). The ClNO2 content of the calibration gas stream was quantified by thermal dissociation cavity ring-down spectroscopy (TD-CRDS) as described in Sect. 2.2.2. In total, 31 calibrations for ClNO2 were carried out, spread out evenly over the measurement period. The iCIMS response factor at m∕z 208 was (0.40 ± 0.06) Hz pptv−1 (where the error represents the standard deviation of repeated calibrations), normalized to 106 counts of reagent ion at m∕z 127. The 37ClNO2I− ion at m∕z 210 was also monitored and found to be (0.298 ± 0.004) times the signal at m∕z 208 (r2 = 0.944), slightly lower than Standard Mean Ocean Chloride 37Cl mole fraction in seawater of ∼ 0.319 (Wieser and Berglund, 2009) and our previously observed ratios of 0.315 ± 0.003 in Calgary (Mielke et al., 2011) and 0.3065 ± 0.0002 in Pasadena (Mielke et al., 2013). The reason(s) for these differences is unclear but they may be a result of fractionation processes (Koehler and Wassenaar, 2010; Volpe et al., 1998), a topic outside the scope of this paper.

The iCIMS was also used to quantify mixing ratios of PAN at m∕z 59 and PPN at m∕z 73 (Slusher et al., 2004; Mielke et al., 2011; Mielke and Osthoff, 2012). For this reason, part of the instrument's inlet prior to the ion–molecule reaction region was heated to 190 ∘C to dissociate PANs into their respective peroxyacyl radicals and NO2. Further, the collisional dissociation chamber (CDC) was operated in declustering mode (−22.7 V) to break up ion clusters. Calibrations and matrix effect correction procedures and a time series of the PAN and PPN data were presented by Tokarek et al. (2014).

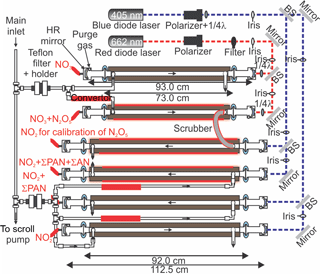

2.2.2 Quantification of NO2 and N2O5 by cavity ring-down spectroscopy

The CRDS used in this work was an amalgamated version of two instruments described earlier (Paul and Osthoff, 2010; Odame-Ankrah and Osthoff, 2011), called Improved Detection Instrument for Nitrogen Oxide Species (iDinos) (Odame-Ankrah, 2015). A schematic of the optical layout is shown in Fig. 2. The optical bread board, instrument frame, electronic, and data acquisition components were as described by Paul and Osthoff (2010). The new instrument was set up with up to six parallel detection channels: four 405 nm “blue” diode laser CRDS cells for quantification at NO2 via its absorption at 405 nm with a distance between the pairs of high-reflectivity (HR) mirrors (Advanced Thin Films) of 112.5 cm, of which 92.0 cm were filled with sample air, and two newly constructed 662 nm “red” diode laser CRDS cells for quantification at NO3 via its absorption at 662 nm with a distance between the HR mirrors (Los Gatos) of 93.0 cm of which 73.0 cm were filled with sample air. Light exiting the far ends of the CRDS cells was collected using fixed-focus collimating lenses and multi-mode optical fibers (Thorlabs) connected to photomultiplier tubes (PMTs; Hamamatsu H9433-03MOD) with 10 MHz bandwidth. Bandpass filters (Thorlabs FB405-10 and FB660-10) were placed between the PMTs and the end of the optical fibers.

The two laser diodes were simultaneously square-wave modulated by a function generator (SRS DS335). The PMT voltages were digitized using an eight-channel 14-bit data acquisition card (National Instruments PCI-6133; 2.5 MS s−1 simultaneous sampling sample rate) connected to a laptop computer via a PCMCIA-to-PCI expansion unit (Magma CB4DRQ) and controlled by software written in LabVIEW™ (National Instruments).

Ring-down time constants (τ) were determined from a linear fit to the logarithm of the digitized PMT voltage as described by Brown et al. (2002) immediately after acquisition of the ring-down traces (which were co-added to a user-selectable averaging time prior to the fit). The fitting algorithm requires the subtraction of the PMT voltage offset prior to taking the logarithm; this offset was measured between ring-down events after the signal had returned to baseline, which limited the repetition rate of the diode lasers and the number of traces averaged per second to a frequency of 300 Hz.

Ring-down time constants in the absence of the target absorber (τ0) were determined by flooding the inlet (each once per hour) with ultra-pure, or “zero”, air (Praxair) for the 405 nm channels and by titration with NO for the 662 nm channel (Brown et al., 2001; Simpson, 2003). Typical values of τ0 were in the range of 63 to 67 µs and between 198 and 210 µs for the blue and red channels, respectively. The baseline precision (i.e., standard deviation, σ) of the NO2 and NO3 measurements were ±80 and ±3 pptv (1 s data), respectively. For the NO3 channels, additional noise was introduced by variable background absorption of NO2, O3, and water vapour which produce small, spurious structure in the 662 nm absorption signal (Dubé et al., 2006) and were not tracked well by the interpolation of the baseline from the hourly τ0 determinations.

During the Abbotsford campaign, only five (four blue and one red) CRDS channels were operated because of delays in the fabrication of the final set of CRDS mirror holders. The 662 nm CRDS cell sampled from a Teflon™ inlet heated to 130 ∘C for quantification of NO3 plus the NO3 generated from thermal dissociation N2O5 (Brown et al., 2001; Simpson, 2003; Dubé et al., 2006). Under the high-NOx conditions of this study, equilibrium (2) was sufficiently far to the right (see Sect. 3.3) such that [NO3] + [N2O5] ≈ [N2O5]; i.e., the concentration measured could be equated with [N2O5] without introducing a large error (i.e., < 5%). The four 405 nm CRDS cells were operated as follows: the first sampled from an ambient temperature inlet and was used to quantify NO2. The second sampled from a quartz inlet heated to 250 ∘C and was used to quantify NO2 plus total peroxyacyl nitrate (ΣPAN) (Paul et al., 2009; Paul and Osthoff, 2010). Data from this channel will be presented in a future publication. The third was operated with a quartz inlet heated to 450 ∘C to enable ClNO2 calibrations (Thaler et al., 2011). Quantification of total alkyl nitrates (ΣAN) in ambient air was not attempted because of the high NOx levels and resulting large subtraction errors (Thieser et al., 2016). The fourth 405 nm CRDS cell was connected with polycarbonate tubing (3/8 in. OD and 1/4 in. ID) in series to the 662 nm channel and was used to calibrate the response of the N2O5 channel, which is a function of the transmission efficiency of N2O5 through the inlet and the overlap of the diode laser spectrum with the NO3 absorption line (Odame-Ankrah and Osthoff, 2011). The role of the polycarbonate tube was to scrub NO3 exiting the N2O5 channel, allowing detection of only the NO2 generated from thermal dissociation of N2O5 and to prevent recombination of NO3 and NO2 in the blue calibration channel (Wagner et al., 2011).

Figure 2Optical layout of the cavity ring-down spectrometer. 1/4λ refers to quarter-wave plate. BS is the beam splitter. HR mirror refers to the high-reflectivity mirror. Drawing is not to scale.

N2O5 was generated in situ by adding an excess of O3 (generated by passing O2 past a 254 nm Hg lamp) to nitric oxide (NO) in a 0.635 cm (1/4 in.) OD and 0.476 cm (3/16 in.) ID Teflon™ calibration line and allowed to equilibrate (i.e., until the output was constant) offline before being switched inline on demand. The N2O5 response (which accounted for N2O5 loss in the sampling line and slight mismatches of the laser wavelengths with the NO3 absorption line) varied between 65 and 100 % and depended on inlet “age”; the Teflon™ inlet and aerosol inlet filter were changed every 2–3 days. The accuracy of the NO2 and N2O5 data were ±10 and ±25 %, respectively, driven mainly by the systematic uncertainty of the NO2 absorption cross section and of the N2O5 inlet transmission efficiency (Odame-Ankrah, 2015).

2.2.3 Measurements of O3, NO, and NOy

Mixing ratios of O3 were monitored by UV absorption in a commercial instrument (Thermo 49) and were accurate within ±2 % and ±1 ppbv. An NO-O3 chemiluminescence instrument (Thermo 42i) was used to monitor mixing ratios of NO and NOy, which was reduced to NO in a Mo converter heated to ∼ 320 ∘C placed outside a short distance (∼ 1 m) from the sample inlet. This instrument sampled from the main inlet via a Teflon™ filter and filter holder and was calibrated daily against CRDS as described by Tokarek et al. (2014). The slope uncertainty for each multipoint calibration was ±15 %. Interpolation between calibration runs gave an overall uncertainty of ±30 %. The NO zero offset uncertainty (needed for calculating the NO3 loss rate with respect to reaction with NO, Reaction R9) was ±10 pptv.

2.2.4 VOC measurements

Volatile organic compounds were monitored with a commercial gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (GC-MS; Agilent model 7890A and 5975C) equipped with an FID detector and a Markes Unity 2 pre-concentrator with an ozone precursor trap cooled to −25 ∘C.

In a typical sampling sequence, a 500 mL air sample was collected at a flow rate of 25 mL min−1, taken from the centre flow of a 1.27 cm (1/2 in.) stainless steel inlet line which was continuously sampling ambient air at 5 L min−1. The sampled air flowed through a 0.318 cm (1/8 in.) stainless steel line and particles were removed using a 1 µ m pore size fritted filter. Once 500 mL of air were collected, the pre-concentrator was flushed with helium to remove air while awaiting injection. At the start of a GC run, the sample in the pre-concentrator was flash heated to 300 ∘C and held for 3 min. The sample was separated on two columns with the entire sample going through the Agilent VRX column with a Dean switch directing the first gases emitted to a second GasPro column and then to the FID detector (∼ < C4), while the heavier compounds were detected using the MS detector in scan mode.

The cycle time for the GC analysis was 1 h with the sample being collected during the previous runs analyses. The 20 min sample was taken at the start of a 1 h time period.

Due to the low temperature of the trap, the air was dried using a trap at −30 ∘C. The trap was heated and dried between each sample and reconditioned for 10 min prior to sample collection. All sample lines were stainless steel with a Restek Sulfinert™ coating to minimize sample loss on the lines. Calibrations were performed once per day for 105 species using a 100 ppbv US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) photochemical assessment monitoring system (PAMS) and a 100 ppb EPA air method, toxic organics – 15 (TO15) standard at an approximate concentration. The terpenes were semi-quantitatively measured as a calibration source was not available at the time and only the changes in concentration strength with time of day were used. The accuracy of the measurements varied depending on the species but was better than ±30 % throughout. Peaks were manually reintegrated using Chemstation software from Agilent. Table S1 in the Supplement summarizes the VOCs quantified.

2.3 Aerosol measurements

The chemical composition of non-refractory PM1 was monitored using an Aerosol Chemical Speciation Monitor (ACSM, Aerodyne), which reported concentrations of NO, SO, Cl−, NH, and total organics. A general description of this instrument designed for routine monitoring has been given by Ng et al. (2011). The composition of the refractory aerosol (i.e., sea salt) was not quantified.

Submicron aerosol size distributions were quantified by a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS, TSI 3034). This instrument measured aerosol particles in the range from 10 to 487 nm using 54 size channels (32 channels per decade). Both of these instruments were housed in a trailer operated by Metro Vancouver. The ACSM and the SMPS sampled air off a shared stainless steel inlet that had a total flow of 5 L min−1 and contained a PM2.5 sharp cut filter at the inlet and was operated at ambient relative humidity.

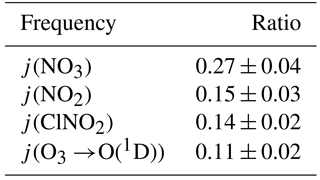

2.4 Photolysis frequencies

Photolysis frequencies were determined by solar actinic flux spectroradiometry (Hofzumahaus et al., 1999) using a commercial radiometer with 2π receptor optics and photodiode array (PDA) detector (Metcon; 512 pixels, wavelength range 285–690 nm) calibrated by the manufacturer. The spectrometer was mounted facing up (zenith view) and hence measured the down-welling radiation. On several days, the spectrometer was inverted hourly to determine the up-welling radiation, which was added to the down-welling flux. Photolysis frequencies including j(NO3), j(NO2), j(O1D), and j(ClNO2) were calculated using reference spectra and quantum yields from Sander et al. (2010) and Ghosh et al. (2012). Table 2 gives the ratio of observed up-welling to down-welling for selected photolysis frequencies. For 3 August (a cloud-free day), the measurements were compared to (hourly) predictions with the online Tropospheric Ultraviolet and Visible (TUV) radiation model V5.0 (Madronich and Flocke, 1997); with default settings, the model reproduced the measured j(NO2) and j(O1D) quite well: a scatter plot of observed against TUV rate constants had correlation coefficients (r) of 0.997 and 0.998, slopes of 1.06 ± 0.02 and 1.10 ± 0.02, and offsets of (3 ± 1) × 10−4 s−1 and (5 ± 3) × 10−7 s−1.

2.5 Box model simulations of the nocturnal O3 and Ox loss in the NBL

A box model was set up to reconcile the median nocturnal decays of O3 and Ox. These simulations are intended as back-of-the-envelope type estimates of major processes only since an accurate description of the nocturnal boundary layer chemistry would require modelling of horizontal and vertical transport, i.e., altitude-resolved information not available in this study (Geyer and Stutz, 2004). The model's assumptions are a well-mixed NBL that is decoupled from the NRL above it as observed by earlier balloon vertical profiling (Pisano et al., 1997), O3 and NO2 dry deposition velocities of vd(O3) = 0.2 cm s−1 and vd(NO2) = α × vd(O3) with α=0.65 (Lin et al., 2010), and negligible chemical O3 and Ox losses other than titration of O3 by NO (Reaction R8) and by reaction with a generic biogenic hydrocarbon (assumed to react with O3 with a rate coefficient of 5 × 10−11 cm3 molec −1 s−1, i.e., the rate coefficient for reaction of α-pinene with O3; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). Simulations were initiated with the median NO2 and O3 concentrations observed at sunset. More details are given in the Supplement.

3.1 Overview of data set

3.1.1 Meteorology

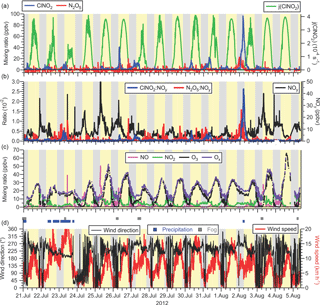

A time series of local wind direction and speed are displayed in Fig. 3d. During the 2-week-long measurement period, the air flow to the site was from the Pacific Ocean to the SW and WSW with a moderate wind speed of 8.7 km h−1 (median value). On most nights, local wind speeds were calm, i.e., < 5 km h−1 (median speed 3.6 km h−1) and from variable directions, though predominantly from the W and N. The two exceptions were the nights of 22–23 July and 1–2 August when stronger winds (> 5 km h−1) from the W and SW persisted. These nights saw relatively high ClNO2 mixing ratios (see Sect. 3.1.4).

The air temperatures were quite mild and ranged from a minimum of 11.0 ∘C to a maximum of 31.9 ∘C. The warm temperatures shifted equilibrium K2 from N2O5 towards NO3 and NO2 (further analyzed in Sect. 3.2.2). At night, temperatures frequently dropped to the dew point, resulting in occasional fog formation (shown as grey rectangles in Figure 3D), sometimes after sunrise. Fog droplets are strong sinks for N2O5 (Osthoff et al., 2006). In total, the impact of fog was minor, affecting 5 % of the data. In addition, there were two periods with precipitation: the first occurred intermittently on 20 July until the morning of 21 July. The second rainfall event was a 24 h period from mid-day 22 July to the afternoon of 23 July (shown as blue dots in Fig. 3d). 23 July also exhibited the highest wind speeds of the campaign (Fig. 3c) and lowest daytime photolysis frequencies. The time series of j(ClNO2) is shown as a representative example in Fig. 3a. The photolysis data indicate that it was sunny on 6 days (25, 26, 29 July and 1, 4, 5 August) and that the remaining days had variable cloud cover, consistent with hourly meteorological logs that showed 10 % of the measurement period affected by precipitation.

Figure 3(a) Time series of N2O5 and ClNO2 mixing ratios (left axis) and ClNO2 photolysis frequency (right axis) observed at T45 near the Abbotsford International Airport. (b) Time series of the ratios of ClNO2 and N2O5 to NOy (left axis) and of NOy (right axis). (c) Time series of NO, NO2, O3, and Ox (= NO2 + O3) mixing ratios. (d) Time series of local wind direction (left axis) and speed (right axis). The blue and grey dots above the time series indicates periods of precipitation (drizzle or rain) and fog, respectively, as identified in hourly meteorological logs.

3.1.2 NO and NO2

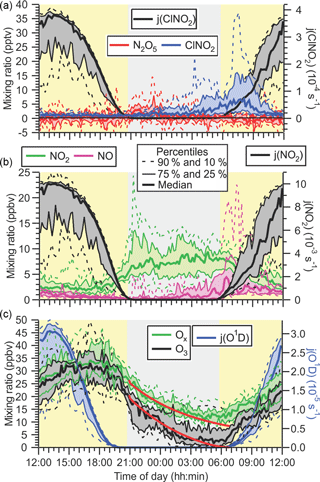

The rates of N2O5 and ClNO2 formation depend on the rate of NO3 production, P(NO3) = k1[NO2][O3] (analyzed further in Sect. 3.2.2); therefore, it is informative to first examine the mixing ratios of NO2 and O3 (see Sect. 3.1.3). The time series of NO, NO2, O3, and Ox (O3 + NO2) mixing ratios are shown in Fig. 3c, and their diurnal averages are shown as 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles in Fig. 4b and c.

Figure 4(a) Diurnal variation of ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios (left axis) and ClNO2 photolysis frequencies (right axis). (b) Diurnal profiles of NO and NO2 (left axis) and NO2 photolysis frequency (right axis). (c) Diurnal profiles of O3 and Ox = O3 + NO2 (left axis) and O3→O(1D) photolysis frequency (right axis). The superimposed lines shown in red are results from a simple box model (see text).

The median NO and NO2 mixing ratios for the entire campaign were 0.9 and 5.9 ppbv, respectively. The average NOx∕NOy ratio for the entire campaign was 0.9 ± 0.4. These concentration levels are characteristic of an urban air mass impacted by relatively fresh emissions from combustion engines in automobiles.

At night, mixing ratios of NO were generally lower than during the day though not negligible (median 0.3 ppbv, Fig. 4b) as NO was oxidized by O3 to NO2 (Reaction R8) and was not replenished by NO2 photolysis. However, mixing ratios of NO increased throughout the night, often coinciding with complete nocturnal removal of O3 (see Sect. 3.1.3), which indicates the presence of nearby combustion sources of NOx (most likely automobile exhaust). The presence of NO titrates NO3 (Reaction R3) and effectively shut down N2O5 and ClNO2 production for most of the study: 68 % of the measurement period had NO mixing ratios > 100 pptv and NO3 lifetimes (with respect to its reaction with NO) of < 15 s. In contrast, NO2 mixing ratios were highest at night (median 7.3 ppbv), amplified further by NOx emissions that continued throughout the night and likely by low nocturnal mixing heights (see discussion).

Mixing ratios of NO and NOx were highest in the morning hours. Concentration changes at this time of day are difficult to interpret since the NBL breaks up during this time, resulting in vertical mixing of air masses, photolabile species (e.g., ClNO2, HONO, N2O5) that accumulated overnight begin to photodissociate, and local emissions change with the onset of rush hour.

In contrast to the morning increase in NO, an afternoon/early evening maximum in NO was absent. This can be rationalized by a greater mixing height and abundance of oxidants that oxidize NO to NO2, i.e., O3 (see Figs. 3 and 4 and Sect. 3.1.3) and organic peroxy radicals in the afternoon, a topic outside the scope of this paper.

3.1.3 O3 and Ox

The time series of O3 mixing ratios and its diurnal profile are shown in Figs. 3c and 4c, respectively. O3 mixing ratios were small (average ±1 standard deviation of 16 ± 12 ppbv) and peaked at ∼ 17:00 PDST in the afternoon. The highest concentrations were observed on August 4 from 13:55 to 15:30, when mixing ratios were 64 ± 1 ppbv (the 8 h running average was 52 ppbv). These levels were well below the CAAQS 8 h standard of 63 ppbv and the 1 h National Ambient Air Quality Objective of 82 ppbv, smaller than the pre-2003 data analyzed by Ainslie and Steyn (2007), who reported between 10 and 20 O3 1 h exceedances of 82 ppbv in the 1980s, and of similar magnitude as observed by a high-density monitoring network in the region in 2012 (Bart et al., 2014), which observed peak O3 levels of 74 and 83 ppbv at Abbotsford on 8 July and 17 August, respectively.

A recurring feature of this data set was the rapid and often complete loss of O3 at night (Fig. 4c). This was accompanied by an increase in the NO2 mixing ratios, though by less (+6 ppbv on average) than the amount of O3 that was lost (−26 ppbv on average), showing that NO to NO2 conversion (Reaction R8) was a contributor, though minor (∼ 25 %) to the nocturnal O3 loss.

The diurnal profile of Ox was similar to that of O3, in that the highest concentrations occurred in the afternoon (at ∼ 18:00) and a considerable fraction of Ox was removed at night. At sunset, a median amount of 26 ppbv of Ox were present, which decreased to 12 ppbv at sunrise (Fig. 4c). The pathways contributing to nocturnal O3 and Ox loss are probed using box model simulations in Sect. 3.2.1.

There were two (out of 16 total) nights when O3 was not completely removed. On 22–23 July and 1–2 August, O3 mixing ratios dropped from a daytime maxima of ∼ 33 ppbv to non-zero nocturnal minima of ∼ 16 ppbv. On both of these nights, ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios were elevated (Fig. 3a), and the two largest ClNO2 to NOy ratios were observed (Fig. 3b). The local wind speeds were > 6 km h−1, whereas on other nights, local winds were calmer (Fig. 3c). The greater local wind speeds likely induced more turbulence and a higher vertical mixing height.

3.1.4 N2O5 and ClNO2

Time series of ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios and ClNO2 photolysis frequencies are shown in Fig. 3a. Mixing ratios of ClNO2 and N2O5 were small (campaign averages at night of 4.0 and 1.4 pptv, respectively). The mixing ratios peaked prior to sunrise at median values of 7.9 and 7.8 pptv for ClNO2 and N2O5, respectively. The highest mixing ratios of this campaign were 97 pptv for ClNO2 and 23 pptv for N2O5, both observed on the night of 1–2 August. This night was also the only time when nocturnal ClNO2 mixing ratios exceeded 20 pptv and is analyzed in greater detail in Sect. 3.2.3.

Consistent with their low mixing ratios, neither ClNO2 nor N2O5 were significant components of NOy (Fig. 3b): on average, they contributed 0.1 % to the nocturnal NOy budget, though NOy mixing ratios were large (median 6.3 ppbv at night), typical for a site impacted by urban emissions. The only exception was the night of 1–2 August, when ClNO2 and N2O5 constituted 2.6 and 1.6 % of NOy, respectively, and NOy mixing ratios were 4.4 ppbv on average (Fig. 3b).

The ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios are displayed as functions of time of day in Fig. 4a. Before midnight local time, N2O5 mixing ratios were slightly larger (median value of 1.8 pptv on average) than those of ClNO2 (median value of 1.4 pptv on average), whereas after midnight ClNO2 mixing ratios were larger than those of N2O5 (2.0 vs. 0.6 pptv). The latter is consistent with observations at other ground sites, which generally showed higher concentrations of the longer-lived ClNO2 prior to sunset (Thornton et al., 2010; Mielke et al., 2013). The higher N2O5 than ClNO2 abundances at the beginning of the nights suggest that the N2O5 production rate at that time exceeded its ability to react heterogeneously and convert to ClNO2, potentially due to a lack of available aerosol chloride or otherwise reduced N2O5 heterogeneous uptake parameters (Thornton et al., 2010).

Production of ClNO2 from N2O5 uptake on aerosol ceases after sunrise because of the rapid removal of N2O5 and NO3 as the latter is titrated by NO and destroyed by photolysis (Reactions R3, R4) (Wayne et al., 1991). In spite of this, ClNO2 mixing ratios frequently (on 12 out of 15 measurement days) continued to increase after sunrise (Figs. 3a and 4), peaking on average at ∼ 07:45 in the morning approximately 2 h after sunrise. The median mixing ratio at that time was 6.7 pptv larger than the median value of 5.3 pptv observed at sunrise. The most prominent example of this phenomenon occurred on the morning of 26 July. For a 2-hour period leading up to sunrise, there was fog (virtually ensuring the absence of N2O5), and ClNO2 mixing ratios were < 5 pptv. The fog then dissipated at sunrise. One hour later, ClNO2 mixing ratios increased to > 40 pptv. Similar events (though with more modest ClNO2 increases) were observed on the mornings of 22, 23, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31 July and 1 August. Two of these (23 and 27 July) overlapped with brief fog events.

Qualitatively similar ClNO2 morning peaks have been observed at other ground sites and were rationalized by vertical mixing (Tham et al., 2016; Bannan et al., 2015; Faxon et al., 2015).

In the period after the ClNO2 morning peak after ∼ 09:00, ClNO2 mixing ratios decreased, coinciding with the increasing ClNO2 photolysis rate. Box model simulations (see Supplement) indicate that the decay of ClNO2 (after 09:00) was consistent with its destruction by photolysis.

There were two exceptions: the mornings of 27 July and 2 August, when the decay of ClNO2 concentration occurred at a rate faster than its photolysis. On 27 July, fog was not observed until 08:00, at which time the ClNO2 mixing ratio rapidly decreased because of dissolution and/or an air mass shift to one with a different chemical history. On 2 August, the campaign maximum of 97 pptv was observed at 04:40 prior to sunrise, followed by a sharp decline. Hourly logs indicated scattered showers at 06:00.

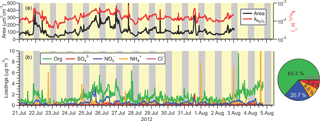

Figure 5Time series of (a) submicron surface area density measured by the TSI 3034 scanning mobility particle sizer (left-hand side) and calculate heterogeneous N2O5 uptake rate coefficient assuming γ=0.025 (right-hand side), and (b)` non-refractory submicron aerosol species measured by ACSM. The average total loading was 2.3 µg m−3. The pie chart shows the average campaign composition.

3.1.5 PM1 size distribution and composition measurements

The time series of PM1 surface area density (SA) observed by the SMPS is shown in Fig. 5a. The aerosol loadings were modest: the average (median) surface area density was 128 (104) µm2 cm−3 and ranged from extremes of 26 to 618 µm2 cm−3. The size distribution data show that bulk of the surface area (i.e., the mean diameter is in the range of 200 to 300 nm, such that most of the area of the accumulation mode was captured. However, the surface area calculations do not include contributions from larger diameter particles which were not quantified. Shown on the right-hand side of Fig. 5a is the rate coefficient for heterogeneous uptake of N2O5, , calculated using Eq. (1).

Here, γ and are the uptake probability and the mean molecular speed of N2O5, respectively. Equation (1) is valid for uptake on small, submicron aerosol as it neglects gas-phase diffusion limitations (Davidovits et al., 2006). For this calculation, a γ value of 0.025 was assumed. The average (±1 standard deviation) of was (2 ± 1) × 10−4 s−1.

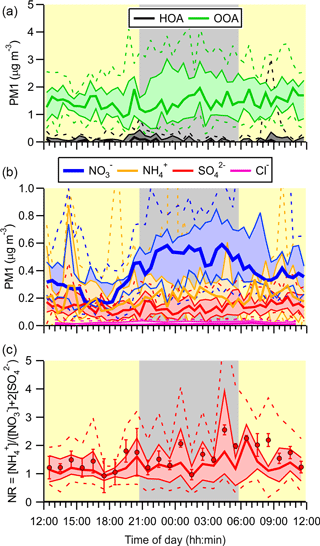

The ACSM submicron aerosol composition data are shown as a time series in Fig. 5b and as a function of time of day in Fig. 6. Consistent with the size distributions, mass loadings were also modest overall (average 2.3 µg m−3). The ACSM factor analysis identified oxygenated organic aerosol (OOA) as the largest mass fraction of the non-refractory aerosol (average ± standard deviation 1.4 ± 1.2 µg m−3, 63.3 % of the total aerosol mass measured by the ACSM). Hydrocarbon-like organic aerosol (HOA) associated with primary emissions was a minor component (average 0.03 µg m−3, 1.1 %) but occasionally enhanced in plumes (maximum 8.3 µg m−3). The OOA did not exhibit a discernible diurnal profile (Fig. 6a), which is consistent with the modest photochemistry at this site as judged from the modest peak O3 levels observed. The inorganic mass fraction was dominated by nitrate (0.47 ± 0.40 µg m−3, 20.7 %). The second most abundant inorganic component was ammonium (0.2 ± 1.4 µg m−3, 8.8 %) followed by sulfate (0.15 ± 0.15 µg m−3, 6.8 %). The data are of similar magnitude as aerosol mass spectrometry (AMS) data collected at nearby Langley as part of Pacific 2001 (Boudries et al., 2004); then, organics were also the largest component (average of 1.6 µg m−3, 49 %), though sulfate and ammonium mass loadings were larger (0.88 and 0.44 µg m−3; 25 and 14 %, respectively) and nitrate mass loadings smaller (0.38 µg m−3, 12 %).

The neutralization ratio, NR ≈ [NH] : ([NO] + 2[SO]) (Zhang et al., 2007), where the square brackets denote molar concentrations (calculated from the mass concentrations reported by the ACSM by dividing by the appropriate molecular weights), was 1.19 (median value). The high NH3 content is qualitatively consistent with the non-quantitative data collected by Metro Vancouver (using a Thermo Scientific 17i analyzer), which showed large concentrations of gas-phase NH3 (Fig. S1).

The ACSM software also reported non-refractory chloride with an average (±1 standard deviation) concentration of 0.01 ± 0.03 µg m−3, though it is unclear whether this signal was real as it did not vary over the course of the campaign and was below the stated ACSM detection of limit of 0.2 µg m−3 (Ng et al., 2011).

Aerosol nitrate exhibited a clear diurnal profile with higher concentrations at night (Fig. 6b). In particular, the amount of aerosol nitrate increased at the beginning of the night, when the nocturnal NO3 production rates were greatest.

Previous AMS measurements in Vancouver during the month of August as part of Pacific 2001 reported a slightly higher total mass loadings of 7.0 µg m−3 that included a greater HOA component (2.4 µg m−3, 34 %) and a smaller nitrate fraction (0.6 µg m−3, 8.5 %) (Alfarra et al., 2004; Jimenez et al., 2009) than observed here. The lower HOA in this data set is likely a result of tighter emission controls implemented since the earlier study, a topic outside the scope of this paper.

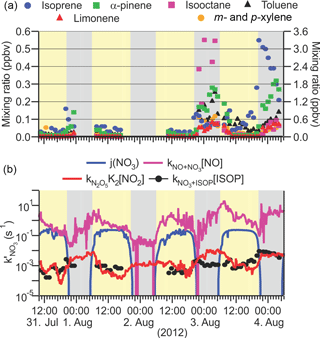

3.1.6 Hydrocarbon measurements

Mixing ratios of hydrocarbons were quantified during daytime and during the nights of 2–3 and 3–4 August. A portion of the hydrocarbon data is shown in Fig. 7a. Mixing ratios were generally smaller during the day than during night, due to the larger daytime mixing heights. On the nights of 2/3 and 3/4 August, N2O5 was not detected, consistent with low P(NO3) values as O3 mixing ratios approached zero (Fig. 3). At the same time, there were strong NO3 sinks present: mixing ratios of α-pinene and limonene (left-hand axis) increased throughout the night, as thermal emissions continued into the shallow NBL. In contrast, mixing ratios of isoprene, whose emissions are driven by photosynthesis (Hewitt et al., 2011; Guenther et al., 1995), increased at the beginning of the nights and then decreased as isoprene was removed by oxidation with O3 and NO3 and by transport. Throughout both nights, the site was also influenced by anthropogenic hydrocarbons (e.g., isooctane and toluene, right-hand axis). Because synoptic conditions as judged from local wind speed and direction (Fig. 3d) were similar on most of the other nights when hydrocarbons were not quantified, the data shown in Fig. 7a were likely representative for much of the campaign.

The VOC data were not sufficiently comprehensive to allow an accurate determination of the NO3 loss frequency to hydrocarbons, given by [VOC]i. Shown in Fig. 7b is the loss frequency of NO3 to isoprene, calculated by multiplying its concentration with the NO3 rate coefficient taken from Seinfeld and Pandis (2006). Loss of NO3 to isoprene was a small sink compared to its loss to NO via Reaction (R3) and NO3 photolysis (Reaction R4) but was approximately on par with its indirect loss, i.e., the heterogeneous uptake of N2O5.

Figure 7(a) Time series of selected VOC mixing ratios observed on the nights of 2/3 and 3/4 August, 2012. Biogenic VOCs (isoprene, α-pinene and limonene) are shown on the left-hand axis, and anthropogenic VOCs (isooctane, toluene and m- and p-xylene) on the right-hand axis. The α-pinene and limonene measurements are semi-quantitative. (b) Time series of NO3 loss-rate coefficients. ISOP = isoprene.

3.2 Analysis

3.2.1 Box model simulations of the nocturnal O3 and Ox loss in the NBL

In initial simulations, the O3 and NO2 deposition rates were tuned until the median nocturnal Ox loss was reproduced. An O3 dry deposition rate of 4 × 10−5 s−1 produced a simulation that reasonably matched the observations (Fig. S2). The magnitude of this rate corresponds to a NBL height of 50 m, the same mixing height that was frequently observed in balloon vertical profiles reported by Pisano et al. (1997). However, since wind speeds at night were low during the study (median 3.6 km h−1), the aerodynamic resistance to vertical transport was likely elevated due to reduced turbulence. It is therefore conceivable that the O3 dry deposition velocity was in actuality smaller than the values taken from Lin et al. (2010) and the mixing height was greater than 50 m.

Modelling studies have assumed N2O5 and NO3 deposition velocities of up to 2 cm s−1 in urban areas (Sander and Crutzen, 1996); adopting this value allows the dry deposition rate constants of N2O5 and NO3 to be estimated at ∼ 4 × 10−4 s−1, which is on par with the estimated heterogeneous uptake rate constant of N2O5 on submicron aerosol.

Next, the generic biogenic VOC was added. For this, a biogenic hydrocarbon abundance of 1 ppbv at sunset (mostly isoprene – see Fig. 7) and a (monoterpene) emission rate of 3 × 105 molecules cm−3 s−1 based on the crop emission factor given by Guenther et al. (2012) into a 50 m deep NBL were assumed. This assumed flux gives a similar emission rate as the 0.3 ppbv increase over a 6 h period observed on 3–4 August (Fig. 7). The addition of this biogenic VOC only had a marginal effect on Ox (Fig. S3).

The simulations presented in Fig. S2 underpredict the observed loss of O3, necessitating the addition of an NO source that results in selective removal of O3 while preserving Ox. Since automobiles are the largest NOx source in the region, a constant emission source of 95 % NO and 5 % NO2 (Wild et al., 2017) was added and its magnitude varied. The NOx source strength necessary to reproduce the median O3 loss was ∼ 1.1 ppbv h−1. The simulation results using these parameters are superimposed (in red) in Fig. 4c. There is reasonable agreement between the simulations and observations of Ox and O3 until ∼ 03:00 (and between simulation and observation of NO, Fig. S4). This shows that the nocturnal O3 and Ox loss can be rationalized without active NO3 and N2O5 chemistry and suggests that NO3, N2O5, and ClNO2 did not contribute significantly to Ox and O3 loss in the NBL.

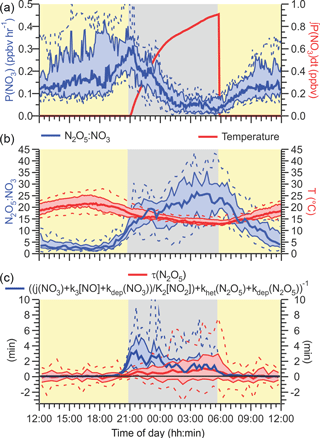

3.2.2 Metrics of nocturnal nitrogen oxide chemistry: P(NO3), ϕ'(ClNO2), and τ(N2O5)

Nocturnal N2O5 chemistry was analyzed using several common metrics: the rate of NO3 production by Reaction (R1), P(NO3)=k1[NO2][O3], the yield of ClNO2 relative to the total amount of NO3 formed at night, ϕ'(ClNO2), and the steady-state lifetime of N2O5, τ(N2O5).

The time-of-day dependence of P(NO3) is shown in Fig. 8a. The NO3 production rates were small (median values < 0.3 ppbv h−1) and were larger during the day than at night due to the low O3 mixing ratios. After midnight, for example, the median P(NO3) was (55 ± 23) pptv h−1. These are very modest NO3 production rates for a site influenced by urban emissions. In a recent study on a mountain top in Hong Kong, for instance, P(NO3) in excess of 1 ppbv h−1 was observed in polluted air (Brown et al., 2016).

The median integrated nocturnal NO3 production over the course of the night was 940 pptv (Fig. 8a, right-hand axis), of which 600 pptv was produced before midnight. The amount of ClNO2 produced relative to this amount, ϕ'(ClNO2), was very small (median 0.17 %, maximum 5.4 % on the morning of 2 August) and considerably less than reported by our group for Calgary (median 1.0 %) (Mielke et al., 2016) and Pasadena, CA (median 12 %) (Mielke et al., 2013).

A frequently calculated metric of nighttime nitrogen oxide chemistry is the steady-state lifetimes of NO3 and N2O5, τ(NO3), and τ(N2O5) (Aldener et al., 2006; Heintz et al., 1996). The latter is calculated from (Brown et al., 2003; Brown and Stutz, 2012)

Here, and are the pseudo-first-order loss-rate coefficients of N2O5 and NO3, respectively, and K2 is the equilibrium constant for equilibrium (Reaction R2).

A central assumption in Reaction (R2) is that NO3, NO2, and N2O5 more rapidly equilibrate than NO3 is formed and either NO3 or N2O5 is destroyed; i.e., NO3 + N2O5 are assumed to be in steady state with respect to production and loss. Brown et al. (2003) outlined potential pitfalls concerning the validity of the steady-state approximation and recommended that box model simulations are carried out to evaluate if a steady state in N2O5 can be assumed. Using the median nocturnal NO2 and O3 mixing ratios of 7.5 ppbv and 18 to 5.0 ppbv, respectively, a temperature of 286 K, and assumed N2O5 and NO3 pseudo-first-order loss frequencies of 1 × 10−3 s−1 and between 1 × 10−2 s−1 and 0 s−1, the time to achieve steady state in N2O5 is 70 min or less (see Supplement). Thus, the steady-state assumption is reasonable for this data set.

A key parameter in Eq. (2) is the strongly temperature-dependent equilibrium constant K2 (Osthoff et al., 2007). At night, the air temperatures during this study were quite warm (median nocturnal minimum of +13 ∘C) and did not vary a lot between nights (Fig. 8b). The warm temperatures shift equilibrium (Reaction R2) away from N2O5 and towards NO3 and NO2, making losses via NO3 (Reactions R3–R4, R7) more competitive with the losses of N2O5 (that produce ClNO2; R), i.e., the term in Eq. (11) becomes large relative to . In contrast, the relatively high NO2 mixing ratios (median value 7.5 ± 0.8 ppbv) shift the equilibrium towards N2O5. Thus, in spite of the relatively warm temperatures, the N2O5: NO3 equilibrium ratios were large on aggregate (> 15; Fig. 8b), enabling ClNO2 formation via Reaction (R5).

The steady-state lifetime of N2O5, τ(N2O5), is shown as a diurnal average in Fig. 8c. The median τ(N2O5) at night was short (∼ 1 min), and the 90th percentile peaked at a modest 7.6 min at sunrise, considerably shorter than observed above the NBL (Brown et al., 2006b) and at other ground sites (Wood et al., 2005; Crowley et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2016)

Superimposed on the right-hand side of Figure 8C are upper limits to the steady-state lifetime of N2O5, calculated using the sum of pseudo-first-order rate coefficients for the titration of NO3 by NO (k3[NO], Reaction R3), NO3 photolysis (j(NO3), Reaction R4), and NO3 dry deposition (kdep(NO3)), all divided by the N2O5 over NO3 ratio at equilibrium given by K2NO2 (Fig. 8b), plus the pseudo-first-order rate coefficient for N2O5 heterogeneous uptake (khet(N2O5), Eq. 1) plus N2O5 dry deposition (kdep(N2O5)).

The dry deposition rate constants were set to 4 × 10−4 s−1 (see Sect. 3.2.1), which likely overestimates dry deposition during the day due to higher mixing heights; however, the error this introduces is negligible compared to the large daytime sinks such as NO3 photolysis and its reaction with NO. Missing from Eq. (3) are losses of NO3 to hydrocarbons (which were omitted because of the poor VOC data coverage) and terms for NO3 and N2O5 wet (i.e., on cloud and rain droplets) deposition. Periods affected by precipitation or fog (shown in Fig. 3d) were hence excluded from the calculation. Estimates of how loss of NO3 to VOCs could affect the lifetime of N2O5 are given in the Supplement.

Figure 8(a) NO3 production rate P(NO3) = k1[NO2][O3] as a function of time of day. The red line is the total amount NO3 generated since sunset, P(NO3)dt. (b) Equilibrium ratio of N2O5 to NO3 calculated by multiplying the temperature-dependent equilibrium constant, K2, with the NO2 concentration, [NO2] (left axis), and air temperature (right axis). (c) Steady-state lifetime of N2O5 (left axis) and upper limits calculated using Eq. (3) (right axis) as functions of time of day.

The median “observed” τ(N2O5) is below or equal to the upper limit calculation with Eq. (3) during both night and day. The largest discrepancy is observed at the beginning of the night, when oxidation of (unsaturated) hydrocarbons by NO3 (Reaction R7) was likely most significant due to the presence of isoprene and other biogenic VOCs. Indeed, if the Σk[VOC]i is assumed to be 0.11 s−1 (average nocturnal NO3 loss frequency reported by Liebmann et al., 2018), the gap between observed and calculated N2O5 lifetime between sunset and midnight closes (Fig. S8). However, this is also the time when the steady-state approximation is most likely invalid.

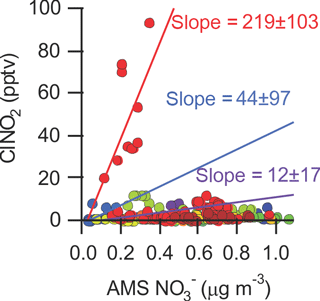

3.2.3 Heterogeneous conversion of N2O5 to ClNO2 on the night of 1/2 August

Phillips et al. (2016) recently applied several methods to estimate the N2O5 uptake parameter (γ) and yield of ClNO2 (φ) from ambient measurements of NO3, N2O5, ClNO2, and aerosol nitrate. One of these methods uses the covariance of ClNO2 and aerosol nitrate production rates, P(NO and P(ClNO2):

In the above equations, c is the mean molecular speed of N2O5 (≈ 237 m s−1). The use of Eqs. (4)–(5) assumes that the relevant properties of the air mass are conserved (i.e., identical upwind of and at the measurement location and affected identically by air masses mixing), that losses of measured species are not significant, that the efficiency of N2O5 uptake and production of ClNO2 and NO is independent of particle size, and that partitioning of HNO3(g) and aerosol nitrate between the gas and particle phases does not occur (Phillips et al., 2016). It is assumed further that production of nitrate from N2O5 uptake on refractory aerosol (that the ACSM does not quantify) is minimal.

In this data set, ClNO2 and non-refractory PM1 nitrate rarely covaried (Fig. 9); the only instance showing a modest correlation (r=0.66) is the time period prior to sunrise of 2 August (shown as red dots in Fig. 9).

Figure 9Scatter plot of ClNO2 mixing ratios with submicron (PM1) ACSM NO data. The slopes were calculated for three periods: 2 August, 01:25–04:55 (red dots; slope = 219 ± 103; φ=0.72), 23 July, 03:00–04:25 (blue dots slope = 44 ± 97; φ=0.21), and 21 July, 02:25–05:20 (purple dots slope = 12 ± 17; φ=0.06).

The night of 1–2 August exhibited the highest nocturnal nitrogen oxide concentrations for the entire campaign. Winds were initially from the NW and relatively light (4.8 ± 0.7 km h−1) and after 01:00 picked up in speed (to 8 ± 1 km h−1) and shifted to the W. Judging from the HYbrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) back trajectories (Stein et al., 2015), the upwind air had moved in from the coast, roughly from the direction of the city of Victoria, BC (Odame-Ankrah, 2015).

After sunset at ∼ 21:00 local time, N2O5 levels started increasing and continued to increase until about 01:30 (Fig. 3a). The steady-state N2O5 lifetime at this time was the highest of the campaign, ∼ 10 min. At 01:20, ClNO2 mixing ratio increased from 20.4 pptv at 01:25 to 93.7 pptv at 04:55 and the PM1 content from 0.10 to 0.34 µg m−3 (40 to 127 pptv). During this time, N2O5 mixing ratios and PM1 surface area density were relatively constant, 11 ± 6 pptv and 67 ± 4 µg m−3 (average ± standard deviation), respectively. The combined amount of N2O5, ClNO2 and PM1 NO produced (172 pptv) is less than the amount of NO3 produced from Reaction (R1) which was 519 pptv during this period.

From Eqs. (4) and (5), a ClNO2 yield of φ = 0.7 ± 0.3 and an N2O5 uptake probability of γ = 0.15 ± 0.07 were calculated for this period. Both of these values are upper limits because production of ClNO2 from uptake of N2O5 on unquantified supermicron (i.e., > 0.5 µm) or refractory aerosol (which takes place simultaneously) is not accounted for.

A γ value of > 0.05 is greater than can be rationalized from laboratory and field studies (Chang et al., 2011) and is hence unrealistic. This suggests that ClNO2 production took place predominantly on supermicron or refractory aerosol, which likely was comprised of mainly sea-salt-derived aerosol (Anlauf et al., 2006). However, if one assumes that “all” of the ClNO2 is produced on supermicron or refractory aerosol such that P(ClNO2) on submicron aerosol equals 0 pptv s−1 (which is not unreasonable considering the absence of measurable amounts of aerosol chloride in this size fraction; see Sect. 3.1.5), a γ value of 0.08 ± 0.04 is calculated. This large value suggests very efficient N2O5 uptake (and conversion to aerosol nitrate) on the non-refractory submicron aerosol that night.

3.3 Impacts of ClNO2 on radical production

Photolysis of ClNO2 increases the rates of photochemical O3 production (and hence worsen air quality) by producing NO2 and reactive Cl atoms (Reaction R6). The amounts of ClNO2 available for photolysis in the morning (median 3.5 pptv at sunrise and 6.8 pptv at 08:00 local time) were too small to have had a measurable impact on local NO2 concentrations (Fig. 3c) but were sufficiently large to, at least occasionally, impact radical budgets.

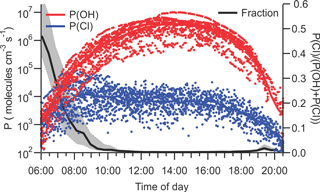

Figure 10 shows the instantaneous radical production rates of Cl and OH, P(Cl) = j(ClNO2) × [ClNO2] and P(OH) from reaction of O(1D)+H2O. The latter was calculated from an assumed steady state in O(1D) with respect to its production from O3 photolysis and reactions with N2, O2, and H2O as described by Mielke et al. (2016). This analysis does not account for OH radical production from photolysis of nitrous acid or aldehydes and, hence, overestimates the importance of Cl radicals.

Figure 10Plots of instantaneous rates of Cl (blue) and OH (red) radical production from ClNO2 photolysis and reaction of O1D, generated from O3 photolysis, with H2O and as a function of time of day. The fraction of radicals produced from ClNO2 photolysis is shown in black. The solid line indicates median values, and shaded areas the 75th and 25th percentiles.

The largest P(Cl) values were observed on 26 July, 07:45 local time (9.5 × 104 atoms cm−3 s−1), accounting for 40 % of the total radical production. The largest fraction of radicals produced from ClNO2 photolysis was observed on the same day at 06:35 local time (74 %, 7.8 × 103 atoms cm−3 s−1). The photolysis of ClNO2 produces a median value of 6.5 × 103 atoms cm−3 s−1 during daytime, which is negligibly small compared to the median P(OH) of 3.8 × 106 molecules cm−3 s−1 at noon.

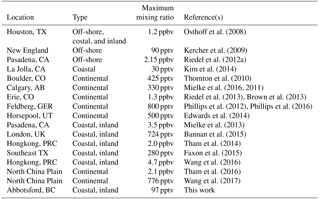

It is now well-established that ClNO2 is an abundant nitrogen oxide in many regions of the troposphere (Table 3). The results presented in this paper are atypical in that they show consistently small ClNO2 mixing ratios in spite of close proximity to sources, i.e., in a region where nearby oceanic emissions of sea salt aerosol and NOx emissions from a megacity combine. In the following, factors contributing to the low ClNO2 mixing ratios observed in this study and broader implications of ClNO2 in the LFV are discussed.

The main reason for the low ClNO2 mixing ratios observed in this work are the low nocturnal mixing ratios of O3 and small NO3 production rate, P(NO3), resulting from the stratification of the boundary layer at night and decoupling of the shallow NBL from the NRL. In the following, it is assumed that a boundary layer structure similar to those observed during PACIFIC 93 (Pisano et al., 1997; McKendry et al., 1997; Hayden et al., 1997) also existed on most measurement nights of this study. Once the nocturnal boundary layer formed at sunset, O3 and Ox in the NBL were rapidly (lifetime of ∼ 4 h) removed. The box model simulations presented in Sect. 3.2.1 show that this removal can be rationalized by dry deposition and titration of O3 with NO and biogenic VOCs alone, leaving little room for nitrogen oxide chemistry to destroy O3 or NO2, for example, via heterogeneous formation of HONO, which destroys NO2 (Stutz et al., 2004a; Indarto, 2012), or formation of N2O5 and subsequent heterogeneous hydrolysis, which consumes two molecules of NO2 and 1 molecule of O3 (Brown et al., 2006a). It is the often complete absence of O3 at night which distinguishes this data set from the other measurement locations for which ClNO2 data have been reported, including continental sites where aerosol chloride is likely less abundant (Table 3).

A compounding factor in this study was the occasional formation of fog and occasional precipitation events. Fog droplets act as a very rapid sink for NO3 and N2O5 (Osthoff et al., 2006), which shuts down ClNO2 production, and may have also directly contributed episodically to ClNO2 losses, for example on the morning of 27 July. Overall, though, the contribution of fog to ClNO2 losses in this data set was minor, as only 5 % of the measurement period was impacted by fog. However, this potential ClNO2 loss mechanism should be investigated further in future lab studies.

The rapid drop of ClNO2 mixing ratio at around 06:00 of 2 August is interesting in that it coincided with a very brief precipitation event. Though an air mass shift cannot be ruled out, this coincidence suggests the possibility that scavenging of ClNO2 by rain droplets followed by hydrolysis may be a possible loss pathway. Scavenging of NO3, N2O5, and ClNO2 by rain droplets is currently not constrained by laboratory investigations (unlike other gases, such as SO2 or NH3; Hannemann et al., 1995). Similarly to fog, precipitation was not a major factor in this data set as it affected only 10 % but may be in other locations or seasons that experience higher rainfall amounts.

An important observation is the lack of non-refractory PM1 chloride (Fig. 5b). This suggests that there was limited redistribution of chloride from acidification of sea salt aerosol onto other aerosol surfaces in this data set. Such a redistribution was observed, for example, during the CalNex-LA campaign, where the AMS measured a median chloride concentration of ∼ 0.1 µg m−3 on non-refractory aerosol (Mielke et al., 2013). This in turn implies that the submicron aerosol surface did not significantly participate in the production of ClNO2 from N2O5 uptake in the NBL, broadly consistent with the conclusions in Sect. 3.2.3 and consistent with measurements of water-soluble aerosol components in the LFV during Pacific 2001 (Anlauf et al., 2006) that showed no evidence for chloride redistribution to PM1 from larger particles where aerosol chloride was present.

The low observed τ(N2O5) is consistent with earlier studies that reported strong vertical gradients in τ(N2O5) due to elevated near-surface sinks from emissions by plants (i.e., monoterpenes) and automobiles (i.e., NO and butadiene; Curren et al., 2006) that titrate NO3 (Stutz et al., 2004b; Wang et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2007; Young et al., 2012). An emblematic example is the study by Wood et al. (2005) at a ground site east of the San Francisco Bay Area in January 2004: They observed relatively modest N2O5 mixing ratios of up to 200 pptv, corresponding to τ(N2O5) < 5 min for the entire study period. Studies for which vertically resolved data were available (e.g., Stutz et al., 2004b; Wang et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2007; Young et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2014) generally showed higher N2O5 concentrations and hence larger τ(N2O5) aloft in the NRL than at the surface.

A different scenario likely played out aloft in the NRL, which would exhibit higher NO3 production rates (via Reactions R1) than the surface layer. Assuming levels of 20 ppbv of O3 and NO2 in the NRL (Pisano et al., 1997; McKendry et al., 1997), the NO3 production rate would equal ∼ 1.1 ppbv h−1 in the NRL, roughly on par with values recently reported for Hong Kong, the current record holder for ClNO2 mixing ratios (Brown et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Recent aircraft and tower studies have shown high rates of production of ClNO2 aloft (Riedel et al., 2013; Young et al., 2012), which likely also occurred in this work.

In contrast, the low mixing height of the NBL is conducive to high levels of biogenic hydrocarbons (Sect. 3.1.6). The nocturnal temperatures during this study were quite warm and did not vary a lot between nights (Fig. 8b). Emissions of monoterpenes, which are reactive towards NO3, are driven by a temperature-dependent process from storage tissue within the plants at night (Guenther et al., 1995) and, hence, were likely substantial. Their presence is likely responsible for the difference between the “observed” N2O5 steady lifetimes, τ(N2O5), and upper limit calculated using equation (3) before midnight (Figs. 8c and S8). Even if one assumes a relatively large uptake probability of γ=0.025 and accounts for the large ratios of N2O5: NO3, the loss rate of N2O5 on submicron aerosol was likely small in comparison to losses via NO3 for most of this data set (Fig. 7b). Hence, only a small fraction of the integrated nocturnal NO3 production of 940 pptv resulted in ClNO2 formation at the surface.

Because of the relatively long lifetime of ClNO2, the breakdown of the surface layer and merging of the surface air with the NRL constituted itself as a ClNO2 “morning peak” in a similar manner as what has recently been reported at other locations (Tham et al., 2016; Bannan et al., 2015; Faxon et al., 2015). This morning peak is rationalized by higher net ClNO2 production in the NRL; the breakup of this layer ∼ 2 h after sunrise then mixes ClNO2 down to the surface. Such a vertical mixing process was not seen during CalNex-LA (Young et al., 2012; Tsai et al., 2014) where the NBL was sufficiently deep to prevent complete O3 removal and the ClNO2 produced mixed down to the surface at night.

Assuming a 100 m deep NRL where ClNO2 production takes place, a mixed layer height of 500 m by 08:00 (Pisano et al., 1997) and negligible destruction of ClNO2 by photolysis (which is reasonable as the lifetime of ClNO2 with respect to photolysis is > 4.6 h at that time of day), a morning increase in ClNO2 mixing ratio by 40 pptv at the surface as seen on the morning of 26 July suggests a pool of ClNO2 in the NRL at sunrise of ∼ 200 pptv, likely a modest value considering that the (assumed) NO3 production rate may have integrated to ∼ 9 ppbv over the course of the night.

The largest nocturnal ClNO2 mixing ratios were observed on 22–23 July and 1–2 August. Both of these nights exhibited high wind speeds and are counterexamples to what was observed on other nights. We speculate that the higher levels of wind shear and turbulence altered the nocturnal boundary layer structure which exhibited a greater degree of vertical mixing and higher O3 concentrations at the surface. Consistent with this interpretation and the notion that an isolated NRL with higher net ClNO2 production was absent on those nights, the mornings of 23 July and 2 August did not show a “morning peak”. In contrast, low surface wind speeds were observed on the other nights, facilitating a stable and shallow nocturnal surface layer.

It is conceivable that a land–sea breeze effect transported air from a region closer to the coast that saw higher ClNO2 production than at Abbotsford, i.e., that the ClNO2 morning peaks are generated by horizontal as opposed to vertical transport. Large NO3 mixing ratios have been reported at Saturna Island (McLaren et al., 2010), which strongly suggest that sizeable reservoirs of ClNO2 form offshore at night. However, it is not known how far inland these reservoirs extend. Considering the average wind speed in the morning (6 km h−1), distance to the coast (35 km), and close proximity (200 m) of the site to the bottom of the polluted NRL with documented high nocturnal pollution levels and early morning down-mixing events, the vertical transport explanation is much more likely correct. Nevertheless, measurements of ClNO2 at a site closer to the coast (e.g., at White Rock) would be beneficial.

Formation of ClNO2 affects air quality through its photolysis which generates Ox, NOx, and reactive Cl radicals in the morning, leading to higher net photochemical O3 production (Sarwar et al., 2014). In spite of the low levels of ClNO2 observed in this work, the production of radicals from its photodissociation was not always negligible (Fig. 10). Conditions leading to O3 exceedances did not develop during this study. If such conditions had developed, it is highly likely that this radical generation pathway would have played a much greater role.

The data presented here suggest that higher rates of ClNO2 and subsequent radical generation take place routinely in layers aloft, processes that are not directly observable at the surface but whose implications are felt as the ultimate product, O3, is sufficiently long-lived to mix down to the surface (McKendry et al., 1997). Future studies should therefore target the NRL, for example through missed-approaches by aircraft, a blimp, or from a tall tower, especially during episodes of a developing O3 exceedance event and also include composition measurements of refractory aerosol.

In this paper, we have presented the first measurements of ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios in the LFV. In spite of the close proximity to NOx (Greater Vancouver) and sea salt aerosol (the Pacific Ocean) sources, ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios were small (maximum of 97 and 27 pptv, respectively) and smaller than observed at other measurement locations for which ClNO2 abundances were reported. The low mixing ratios are explained through the removal of O3 by deposition and titration with NO in a shallow nocturnal surface layer. Measurements of submicron aerosol composition by ACSM showed no enhancements of particle-phase chloride, which is in contrast to locations where high ClNO2 mixing ratios were observed (such as Pasadena; Mielke et al., 2013) and indicates that there was little processing and redistribution of sea-salt-derived chloride at this location. There is indirect evidence that higher production of ClNO2 took place above the measurement site in the NRL, observed via down-mixing after the breakup of the NBL in the morning, and highlights the need for future vertically resolved measurements (e.g., from an aircraft platform) of ClNO2 and N2O5 mixing ratios in the LFV. Conditions leading to O3 exceedances did not develop during the relatively short measurement period of 2 weeks, such that the full impact that nocturnal formation of ClNO2 could have on radical production and NO2 recycling remains unquantified.

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request (hosthoff@ucalgary.ca).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-6293-2018-supplement.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This project was undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Federal Department of the Environment. Partial funding for this work was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) in the form of operating (“Discovery”) and Research Tools and Instruments (RTI) grants. The Abbotsford field study was financially supported by a BC Clear research grant from the Fraser Basin Council of British Columbia and by Metro Vancouver.

The authors acknowledge support by the Open Access Authors Fund at the

University of Calgary and the NOAA Air Resources Laboratory (ARL)

for the provision of the HYSPLIT transport and dispersion model

and/or READY website (http://www.ready.noaa.gov) used in this

publication.

Edited by: Timothy Bertram

Reviewed by: three anonymous referees

Ainslie, B. and Steyn, D. G.: Spatiotemporal Trends in Episodic Ozone Pollution in the Lower Fraser Valley, British Columbia, in Relation to Mesoscale Atmospheric Circulation Patterns and Emissions, J. Appl. Met. Climatol., 46, 1631–1644, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAM2547.1, 2007.

Ainslie, B., Steyn, D. G., Reuten, C., and Jackson, P. L.: A Retrospective Analysis of Ozone Formation in the Lower Fraser Valley, British Columbia, Canada. Part II: Influence of Emissions Reductions on Ozone Formation, Atmos.-Ocean, 51, 170–186, https://doi.org/10.1080/07055900.2013.782264, 2013.

Aldener, M., Brown, S. S., Stark, H., Williams, E. J., Lerner, B. M., Kuster, W. C., Goldan, P. D., Quinn, P. K., Bates, T. S., Fehsenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Reactivity and loss mechanisms of NO3 and N2O5 in a polluted marine environment: Results from in situ measurements during New England Air Quality Study 2002, J. Geophys. Res., 111, D23S73, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD007252, 2006.

Alfarra, M. R., Coe, H., Allan, J. D., Bower, K. N., Boudries, H., Canagaratna, M. R., Jimenez, J. L., Jayne, J. T., Garforth, A. A., Li, S.-M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Characterization of urban and rural organic particulate in the Lower Fraser Valley using two Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometers, Atmos. Environ., 38, 5745–5758, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.01.054, 2004.

Alicke, B., Geyer, A., Hofzumahaus, A., Holland, F., Konrad, S., Patz, H. W., Schafer, J., Stutz, J., Volz-Thomas, A., and Platt, U.: OH formation by HONO photolysis during the BERLIOZ experiment, J. Geophys. Res., 108, 8247, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000579, 2003.

Anlauf, K., Li, S.-M., Leaitch, R., Brook, J., Hayden, K., Toom-Sauntry, D., and Wiebe, A.: Ionic composition and size characteristics of particles in the Lower Fraser Valley: Pacific 2001 field study, Atmos. Environ., 40, 2662–2675, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.12.027, 2006.

Bannan, T. J., Booth, A. M., Bacak, A., Muller, J. B. A., Leather, K. E., Le Breton, M., Jones, B., Young, D., Coe, H., Allan, J., Visser, S., Slowik, J. G., Furger, M., Prévôt, A. S. H., Lee, J., Dunmore, R. E., Hopkins, J. R., Hamilton, J. F., Lewis, A. C., Whalley, L. K., Sharp, T., Stone, D., Heard, D. E., Fleming, Z. L., Leigh, R., Shallcross, D. E., and Percival, C. J.: The first UK measurements of nitryl chloride using a chemical ionization mass spectrometer in central London in the summer of 2012, and an investigation of the role of Cl atom oxidation, J. Geophys. Res., 120, 5638–5657, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jd022629, 2015.

Bart, M., Williams, D. E., Ainslie, B., McKendry, I., Salmond, J., Grange, S. K., Alavi-Shoshtari, M., Steyn, D., and Henshaw, G. S.: High Density Ozone Monitoring Using Gas Sensitive Semi-Conductor Sensors in the Lower Fraser Valley, British Columbia, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 3970–3977, https://doi.org/10.1021/es404610t, 2014.

Behnke, W., George, C., Scheer, V., and Zetzsch, C.: Production and decay of ClNO2, from the reaction of gaseous N2O5 with NaCl solution: Bulk and aerosol experiments, J. Geophys. Res., 102, 3795–3804, https://doi.org/10.1029/96JD03057 1997.