the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Measurements of atmospheric ethene by solar absorption FTIR spectrometry

Geoffrey C. Toon

Jean-Francois L. Blavier

Keeyoon Sung

Atmospheric ethene (C2H4; ethylene) amounts have been retrieved from high-resolution solar absorption spectra measured by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) MkIV interferometer. Data recorded from 1985 to 2016 from a dozen ground-based sites have been analyzed, mostly between 30 and 67∘ N. At clean-air sites such as Alaska, Sweden, New Mexico, or the mountains of California, the ethene columns were always less than 1 × 1015 molec cm−2 and therefore undetectable. In urban sites such as JPL, California, ethene was measurable with column amounts of 20 × 1015 molec cm−2 observed in the 1990s. Despite the increasing population and traffic in southern California, a factor 3 decrease in ethene column density is observed over JPL over the past 25 years, accompanied by a decrease in CO. This is likely due to southern California's increasingly stringent vehicle exhaust regulations and tighter enforcement over this period.

- Article

(4376 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1243 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The author's copyright for this publication is transferred to the California Institute of Technology.

Atmospheric ethene arises from microbial activity in soil and water, biological formation in plants, and by incomplete combustion from sources such as biomass burning, power plants, and combustion engines. Ethene is primarily destroyed by reaction with OH (Olivella and Sole, 2004), which is rapid, giving ethene a tropospheric lifetime of only 1 to 3 days. Despite covering only 29 % of the Earth's area, the land produces 89 % of the ethene (Sawada and Totsuka, 1986). This is mainly natural, but in urban environments or near fires, ethene from incomplete combustion can dominate. Sawada and Totsuka (1986) used measurements of ethene emissions per unit biomass to derive a global source of 26.2 Tg yr−1 from natural emissions and 9.2 Tg yr−1 from anthropogenic emissions, giving a total of 35.4 Tg yr−1, which ranges from 18 to 45 Tg yr−1. Goldstein et al. (1996) measured ethene emissions from Harvard Forest, Massachusetts, and found that they were linearly correlated with levels of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), indicating a photosynthetic source. Based on this, they estimated that at Harvard Forest biogenic emissions of ethene correspond to approximately 50 % of anthropogenic sources. Using these fluxes, and the ecosystem areas tabulated by Sawada and Totsuka (1986), a global biogenic source for ethene of 21 Tg yr−1 was calculated. This value is similar to the estimates of Hough (1991). The ethene fluxes listed by Poisson et al. (2000), however, are only 11.8 Tg yr−1, while those of Muller and Brasseur (1995) are only 5 Tg yr−1. Abeles et al. (1992) estimate a terrestrial biogenic source of 16.6 Tg yr−1 and an anthropogenic source of 9.2 Tg yr−1. Combustion of fossil fuels amounts to only 21 % of these anthropogenic emissions globally, but in urban areas this can be the major source.

There have been previous measurements of ethene using in situ techniques and also using remote sensing. These will be discussed later in the context of comparisons with results from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) MkIV interferometer, an infrared Fourier transform spectrometer that uses the sun as a source. We report here long-term remote sensing measurements of C2H4 in the lower troposphere, where the vast majority of C2H4 resides, using ground-based MkIV observations. We also present MkIV balloon measurements of C2H4 in the upper troposphere.

2.1 MkIV instrument

The MkIV Fourier Transform Spectrometer (FTS) is a double-passed Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer designed and built at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 1984 for atmospheric observations (Toon, 1991). It covers the entire 650–5650 cm−1 region simultaneously with two detectors: a HgCdTe photoconductor covering 650–1800 cm−1 and an InSb photodiode covering 1800–5650 cm−1. The MkIV instrument has flown 24 balloon flights since 1989. It has also flown on over 40 flights of the NASA DC-8 aircraft as part of various campaigns during 1987 to 1992 studying high-latitude ozone loss. MkIV has also made 1208 days of ground-based observations since 1985 from a dozen different sites, from Antarctica to the Arctic, from sea level to 3.8 km altitude. Details of the ground-based measurements and sites can be found at http://mark4sun.jpl.nasa.gov/ground.html. MkIV observations have been extensively compared with satellite remote sounders (e.g., Velazco et al., 2011) and with in situ data (e.g., Toon et al., 1999a, b).

2.2 Spectral analysis

The spectral fitting was performed with the GFIT (Gas Fitting) code, a nonlinear least-squares algorithm developed at JPL that scales the atmospheric gas volume mixing ratio (VMR) profiles to fit calculated spectra to those measured. For balloon observations, the atmosphere was discretized into 100 layers of 1 km thickness. For ground-based observations, 70 layers of 1 km thickness were used. Absorption coefficients were computed line-by-line assuming a Voigt line shape and using the ATM line list (Toon, 2014a) for the telluric lines. This is a “greatest hits” compilation, founded on HITRAN, but not always the latest version for every band of every gas. For example, in cases (gases/bands) where the HITRAN 2012 line list (Rothman et al., 2012) gave poorer fits than HITRAN 2008, the earlier version was retained. The C2H4 line list covering the 950 cm−1 region containing the ν7 and ν8 bands is described by Rothman et al. (2003). The solar line list (Toon, 2014b) used in the analysis of the ground-based MkIV spectra was obtained from balloon flights of the MkIV instrument.

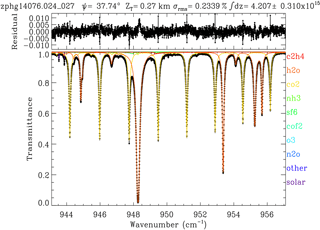

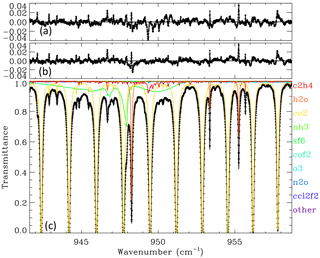

Figure 1Example of a fit to a ground-based MkIV spectrum measured from JPL, California, on 17 March 2014 at a solar zenith angle of ψ= 37.7∘ from a pressure altitude of ZT=0.27 km. In the lower panel, black diamond symbols represent the measured spectrum, the black line represents the fitted calculation, and the colored lines represent the contributions of the various absorbing gases, mainly CO2 (amber) and H2O (orange). Also fitted are the 0 and 100 % signal levels, separate telluric and solar frequency shifts, together with five more weakly absorbing gases (NH3, SF6, COF2, O3, and N2O). The retrieved C2H4 column amount on this day, 4.2 × 1015 molec cm−2, would represent 2 ppb confined to the lowest 100 mbar (1.5 km) of the atmosphere. The C2H4 absorption contribution (red) peaks at 949.35 cm−1 with an amplitude of less than 1 % and is therefore difficult to discern on this plot. The upper panel shows fitting residuals (measured minus calculated), peaking at 0.013 (1.3 %) with an rms deviation of 0.234 %, which are mainly correlated with absorption features of H2O and CO2.

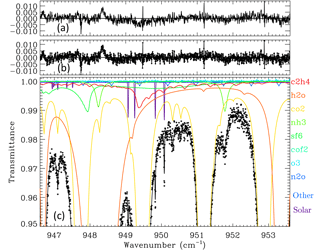

Figure 2Panels (b) and (c) are as described in Fig. 1, but zoomed in to reveal more detail of the C2H4 Q-branch (red) whose absorption peaks at 949.35 cm−1. Panel (a) shows residuals from a fit that omitted C2H4. This causes a discernable 0.5 % dip in the residuals around 949.35 cm−1 and a worsening of the rms spectral fits from 0.234 to 0.251 %.

Sen et al. (1996) provide a more detailed description of the use of the GFIT code for retrieval of VMR profiles from MkIV balloon spectra. GFIT was previously used for the Version 3 analysis (Irion et al., 2003) of spectra measured by the Atmospheric Trace Molecule Occultation Spectrometer (ATMOS), and it is currently used for analysis of Total Carbon Column Observing Network (TCCON) spectra (Wunch et al., 2011) and MkIV spectra (Toon, 2016).

We analyzed the strongest infrared absorption feature of ethene: the Q-branch of the ν7 band (CH2 wag) at 949 cm−1. This is 7 times stronger than any other feature, including the 3000 cm−1 region containing the CH-stretch vibrational modes.

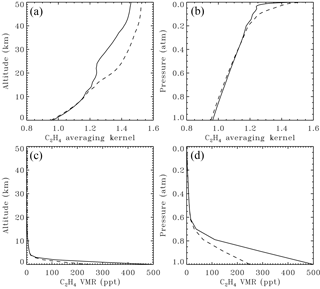

Figure 3Averaging kernels (a, b) and a priori volume mixing ratio (VMR) profiles (c, d) pertaining to the ground-based C2H4 retrieval illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2. In panels (a) and (c) quantities are plotted versus altitude. Panels (b, d) show the same data plotted versus atmospheric pressure. The solid line is the actual profile used. The dashed line is a VMR profile with a less dramatic decrease with altitude: the C2H4 VMR below 4 km has been halved, with similar amounts in the upper troposphere, and more in the stratosphere. The resulting change in the retrieved total column is only 2 %, with the dashed profile giving the smaller columns.

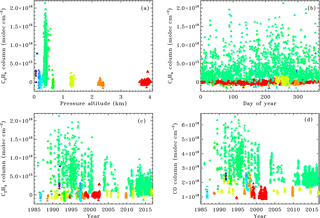

Figure 4MkIV column C2H4 amounts retrieved from 12 different sites, color-coded by pressure altitude. Significant C2H4 amounts are only found at the urban sites: JPL at 0.35 km altitude (green) and Mountain View at 0.01 km altitude (purple). Panel (b) reveals little seasonal variation in C2H4. Panel (c) shows a factor 3 decline in C2H4 in Pasadena over the past 25 years. Panel (d) shows that the CO columns also decreased since 1990, but never come close to zero.

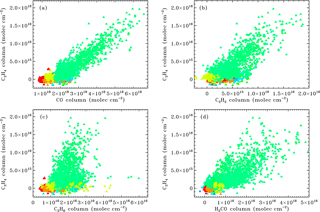

Figure 5Relationships between C2H4 and four other gases: (a) CO, (b) C2H2, (c) C2H6, and (d) H2CO. Points are color-coded by altitude, as in Fig. 4.

Figure 6Relationships between MkIV vertical column abundances of various gases measured from JPL only, color-coded by year (blue is 1990, green is 2000, orange is 2010, and red is 2015). The black line in each panel is the best-fit straight line through the data (not constrained to pass through the origin). The gradient of the fitted straight line () and the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) are written at the top of each panel. Panels on the same row all have the same y axis, avoiding repetition of the y annotation. Panels in the same column have the same x axis, avoiding repetition of the x annotation. Each panel contains 1689 to 1724 observations, representing over 98 % of the available JPL data. Note that the CO abundances have been divided by 1000 to bring them closer to the other gases. Thus the gas : CO gradients are in units of ppt ppb−1, whereas the gradients of the non-CO gases are in ppt ppt−1. In the first column, the gradients could be termed “emission ratios”.

For data acquisition from JPL, the MkIV instrument was indoors with a coelostat mounted to the south wall of the building feeding direct sunlight into the room. Figure 1 shows a fit to the 943–957 cm−1 region of one such spectrum. The strongest absorptions are from H2O lines (orange), one of which is blacked out at 948.25 cm−1. There are also eight CO2 lines (amber) in this window with depths of 40–60 %, one of which sits directly atop the C2H4 Q-branch at 949.35 cm−1. These CO2 lines are temperature-sensitive, having ground-state energies in the range 1400 to 1600 cm−1. It is not possible to clearly see the C2H4 absorption in Fig. 1, and so Fig. 2 zooms into the Q-branch region. The lower panel reveals that the peak C2H4 absorption is less than 1 % deep and strongly overlapped by CO2. It is also overlapped by absorption from H2O, SF6, NH3, N2O, and solar OH lines. NH3 absorption lines exceed 1 % in this window on this particular day but do not overlap the strongest part of the C2H4 Q-branch. The SF6ν3 Q-branch at 947.9 cm−1 also exceeds 1 % but fortunately does not overlap the C2H4 Q-branch. The SF6 R-branch, however, underlies the C2H4 Q-branch with about 0.3 % absorption depth. The upper panel shows the same spectrum fitted without any C2H4 absorption. This causes a ∼ 0.5 % dip in the residuals around 949.35 cm−1 and an increase in the overall rms from 0.234 to 0.251 %. The 0.5 % dip in the residuals is weaker than the 0.9 % depth of the C2H4 feature in the lower panel because the other fitted gases have been adjusted to try to compensate for the missing C2H4. Their inability to completely do so supports the attribution of this dip to C2H4.

Given the severity of the interference, especially the directly overlying 60 % deep CO2 line, we were at first skeptical that C2H4 could be retrieved to a worthwhile accuracy from this window, or any other. But given the good quality of the spectral fits, and the small reported uncertainties, we nevertheless went ahead and analyzed the entire MkIV ground-based spectral dataset, consisting of 4379 spectra acquired on 1208 different days over the past 30 years. Of these 1208 days, 1132 were used in this work.

Figure 3 shows the averaging kernel and a priori profile pertaining to the C2H4 retrieval illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2. The kernel represents the change in the total retrieved column due to the addition of one unit of C2H4 molecules cm−2 at a particular altitude. In a perfect column retrieval, the kernel would be 1.0 at all altitudes, but in reality the retrieval is more sensitive to C2H4 at high altitudes than near the surface, as is typical for a profile-scaling retrieval of a weakly absorbing gas. The a priori VMR profile has a value of 500 ppt at the surface, dropping rapidly to 10 ppt by 5 km altitude. An even larger fractional drop, from 10 to 0.5 ppt occurs in the lower stratosphere between 15 and 21 km. The slight kink in the averaging kernel (solid line) over this same altitude range is due to this large drop in VMR. Since 99 % of the C2H4 lies in the troposphere, the stratospheric portion of the averaging kernel is of academic interest only for total column retrievals.

An important uncertainty in the retrieved column amounts is likely to be the smoothing error, which represents the effect of error in the shape of the a priori VMR profile. If the averaging kernel were perfect (i.e., 1.0 at all altitudes) this would not matter, but in fact the C2H4 kernels vary from 0.96 at the ground to 1.4 at 40 km altitude. To investigate the sensitivity of the retrieved column to the assumed a priori profile, we also performed retrievals with a different a priori VMR profile in which the C2H4 VMR profile had been halved in the 0–4 km altitude range and increased in the stratosphere, as depicted by the dashed line in Fig. 3. The resulting change in the retrieved C2H4 column was less than 2 % with no discernable change to the rms fitting residuals, which are dominated by the interfering gases. This small C2H4 column perturbation is a result of the averaging kernel being close to 1.0 at the altitudes with the largest a priori VMR errors (0–3 km). Note that only errors in the shape of the a priori VMR profile affect the retrieved columns in a profile scaling retrieval.

3.1 Ground-based MkIV retrievals

Figure 4 shows the retrieved MkIV ground-based C2H4 columns from a dozen different observation sites, whose key attributes (e.g., latitude, longitude, altitude, observations, observation days) are presented in Tables SI.1 and SI.2 in the Supplement. The plot is color-coded by the pressure altitude of the site. This was preferred over geometric altitude to prevent all the points from a given site piling up at exactly the same x-value. The pressure altitude varies by up to ±1.5 % at the high altitude sites, which is equivalent to ±0.2 km. Only points with C2H4 uncertainties < 1 × 1015 molecules cm−2 were included in the plot, representing 95.7 % of the total data volume. One day (out of 258) at Barcroft (3.8 km altitude) was omitted from the plotted data because it had abnormally high C2H4, as well as other short-lived gases – clearly a local pollution event.

At all sites above 0.5 km altitude there is essentially no measurable C2H4. The Table Mountain Facility (TMF) site at 2.3 km altitude (orange) is only 25 km from the most polluted part of the Los Angeles basin; yet no measurable C2H4 was recorded there in 45 observation days, despite the good measurement accuracy at this site (see Fig. SI.3 in the Supplement). This is probably a result of the TMF always being above the PBL (planetary boundary layer), in which urban pollution is trapped, at least on the autumn and winter days when MkIV made measurements at the TMF. The high-latitude sites at Fairbanks, Esrange, and McMurdo also have no measurable C2H4, as do rural, midlatitude sites (e.g., Ft. Sumner, NM). The only sites where MkIV has ever detected C2H4 are JPL/Pasadena (0.4 km; green) and Mountain View (0.01 km, purple). These sites are part of major conurbations: Pasadena adjoins Los Angeles; Mountain View adjoins San Jose, California.

The main limitation to the accuracy of C2H4 measurements using the solar absorption technique is the ability to accurately account for the absorption from CO2, H2O, and SF6, which overlap the Q-branch. The first two gases, in particular, being much stronger absorbers than C2H4, have the potential to drastically perturb the C2H4 retrieval. For example, an error in the assumed H2O VMR vertical profile, and hence the shape of the H2O absorption line, will have a large effect on retrieved C2H4. And since the overlapping CO2 lines are so temperature-sensitive (∼ 2 % K−1), a small error in the assumed tropospheric temperature would greatly influence the C2H4 retrieval. Errors in the spectroscopy of H2O and CO2 will also strongly affect C2H4 retrievals. Figure SI.3 shows the C2H4 retrieval uncertainties, estimated by solving the matrix equation that relates the Jacobians of the various retrieved quantities to the spectral residuals. The uncertainties are the square root of the diagonal elements of the resulting covariance matrix. The same data are plotted versus year, solar zenith angle, and site altitude. From JPL the measurement uncertainty is about 0.5 × 1015 molec cm−2. At higher solar zenith angles (air masses) the uncertainty decreases as the C2H4 absorption deepens. At higher altitudes the uncertainty decreases as the interfering absorptions shrink faster than that of C2H4. There has been no significant change in the C2H4 retrieval uncertainty over the 30-year measurement period. We note that the measurements made from McMurdo, Antarctica, in September/October 1986 have very small uncertainties, due to their high air mass and the extremely small H2O absorption. The plotted uncertainties represent a single observation representing a 10–15 min integration period. A total of 95.7 % of the C2H4 observations have uncertainties < 1.0 × 1015 molec cm−2.

At JPL the C2H4 column is highly variable. JPL is located at the northern edge of the Los Angeles conurbation, and so when winds are from the northern sector, or strong from the ocean, pollution levels are much smaller than during stagnant conditions. This is seen in the large range of retrieved C2H4 values observed at JPL throughout the year. A notable feature of the MkIV C2H4 data (Fig. 4c) is the factor 3 drop over the past 25 years. In the 1990s C2H4 often topped 16 × 1015 molec cm−2, but since 2010 a column exceeding 8 × 1015 has only been observed once.

Figure 4d shows the CO time series, which exhibits a substantial decline since the 1990s, although not as dramatic as that of C2H4 since CO never falls below 1.5 × 1018 molec cm−2 at JPL, even under the cleanest conditions, due to its nonzero background concentration.

Figure 5 shows the relationships between C2H4 and four other gases: CO, C2H2, C2H6, and H2CO. Figure 5a reveals a compact, linear relationship between C2H4 and CO at JPL (green points), suggesting a common local source for both. Figure 5b–d show that C2H4 is clearly related to the other gases, but not as strongly as with CO. This is likely due to them having other sources; for example, C2H6 also comes from natural gas leaks, causing the bifurcated appearance of Fig. 5c. Since these trace gases are much less abundant than CO, their measurements are noisier, which also degrades the compactness of the relationship.

Figure 6 plots the gas column relationships for the JPL data only, color-coded by year to help reveal the long-term changes. The decreases in the CO, C2H2, C2H4, and H2CO since the 1990s are evident by the lack of red points in the upper right of the panels plotting these gases. C2H6 has not decreased significantly as is evident from the third row of panels, which shows that the 2015 column abundances (red) span similar values to those measured in 1990 (blue). In fact, on 10 November 2015, we observed a factor 2–3 enhancement of the C2H6 column as a result of JPL being directly downwind of the Aliso Canyon natural gas leak on that day (Conley et al., 2016). Although this event was associated with a 2.5 % enhancement of column CH4 (not shown here), there were no enhancements of CO, C2H2, C2H4, so these particular C2H6 points (red) in the third row of Fig. 6 protrude upwards from the main clusters. Since C2H6 has failed to decrease over the measurement period, unlike the other gases, the C2H6–gas relationships all show a bifurcation, with the later data (red) showing steeper gradients (more C2H6).

Figure 7Panel (c) shows a fit to a MkIV balloon spectrum measured over Esrange, Sweden, in December 1999, with strong C2H4 absorption measured at 6.1 km tangent altitude. The C2H4 absorption is denoted by the red line. Its Q-branch is seen at 949.35 cm−1, reaching 6 % in depth in this particular spectrum. In addition to C2H4, other gases were adjusted including H2O, CO2, O3, SF6, COF2, N2O, NH3, and CCl2F2. CH3OH was included in the calculation but not adjusted. Panel (b) shows residuals (measured minus calculated), the largest values of which are mainly due to H2O. Panel (a) shows residuals after omitting C2H4 from the calculation, which causes a large dip in the residuals at 949.35 cm−1 and increases the overall rms residual from 0.50 to 0.63 %.

A straight line was fitted through the data in each panel of Fig. 6, allowing a gradient and an offset to be computed. The values of the gradients () are written into each panel, along with their uncertainties. The overall gradient of the C2H4 ∕ CO relationship using all JPL data is 3.7 ± 0.4 ppt ppb−1, but the post-2010 JPL data have a gradient of only 2.8 ± 0.4 ppt ppb−1. Baker et al. (2008) measured C2H4 ∕ CO emission ratios of 5.7 ppt ppb−1 in Los Angeles from whole air canister samples acquired between 1999 and 2005, which is close to their average of all US cities, 4.1 ppt ppb−1. Over this same time period the MkIV JPL data report 3.9 ± 0.7 ppt ppb−1, the larger uncertainty reflecting the relatively few observations from JPL over this period. Warneke et al. (2007) report a C2H4 ∕ CO emissions ratio of 4.9 ppt ppb−1 in Los Angeles in 2002, measured by aircraft canister samples. Warneke et al. (2012) report decreases of 6–8 % yr−1 in C2H4 and CO over Los Angeles between 2002 and 2010, but little change in the C2H4 ∕ CO emission ratio, which remained at 5–6 ppt ppb−1.

Figure 6 also includes the Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) of the JPL-only gas relationships. The highest values are between CO and C2H2 (0.91) and CO and C2H4 (0.92). The PCC between C2H2 and C2H4 is only 0.84, probably reflecting the fact that C2H2 and C2H4 are much more difficult to measure (i.e., noisier) than CO. The worst correlation is between C2H6 and H2CO (−0.03).

To see whether the ground-based MkIV C2H4 measured in Pasadena was correlated with the air mass origin, we performed HYSPLIT back trajectories, and computed the amount of time that air masses arriving 500 m above JPL had spent over the highly populated areas of the Los Angeles conurbation. When column C2H4 was plotted versus the predicted duration over the conurbation, the correlation was very poor. Column CO also had a poor correlation. The fact that the C2H4 correlates well with CO tends to discount the possibility that the C2H4 measurements are wrong, since the CO measurements are very easy. Therefore, this implies that the trajectories are not sufficiently accurate. We point out that JPL is located at the foot of the San Gabriel mountains, which rise over 1 km above JPL over a horizontal distance of less than 5 km. This extreme topography might give rise to complexities in the wind fields that might be inadequately represented in the EDAS 40 km resolution model. Although higher resolution models (e.g., NAM 12 km) are available for doing HYSPLIT trajectories, these cover only the past decade, whereas the JPL MkIV measurements go back more than 30 years.

3.2 MkIV balloon profiles

We also looked for ethene in MkIV balloon spectra using exactly the same window, spectroscopy, and fitting software (GFIT) as used for MkIV ground-based measurements. The advantage of the balloon spectra is that the air mass is much larger and the solar and instrumental features are removed from the occultation spectra by ratioing them against a high-Sun spectrum taken at noon from float altitude.

Figure 7 shows a spectral fit to the MkIV balloon spectrum at 6.1 km tangent altitude measured above Esrange, Sweden, in December 1999. The peak C2H4 absorption at 949.35 cm−1 is about 6 % deep, although this falls beneath a saturated CO2 line. The information about C2H4 at this and lower altitudes therefore comes from adjacent weaker features. At higher altitudes (not shown), where the CO2 lines are weaker and narrower, the C2H4 information comes mainly from the 949.35 cm−1 Q-branch.

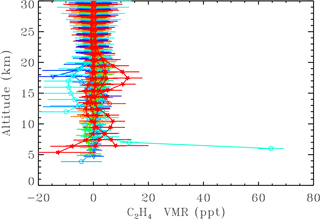

Figure 8 shows 30 balloon profiles of C2H4 from 23 flights, color-coded according to date. The C2H4 VMR retrieved from the December 1999 flight (green) was 65 ± 6 ppt at 6 km, decreasing to 14 ± 4 at 7 km, and undetectable above. The remaining balloon flights indicate a 10 ppt upper limit for C2H4 in the free troposphere and 15 ppt in the stratosphere. Of course, these balloon flights were generally launched under calm, anticyclonic, clear-sky conditions, which tend to preclude transport of PBL pollutants up to the free troposphere. Therefore, there may be an inherent sampling bias in the MkIV balloon measurements that leads to low C2H4.

PBL altitudes (0–3 km) are inaccessible from balloon flights due to the high aerosol content making the long limb path opaque (although they can be probed from the ground). Therefore, the balloon measurements are not inconsistent with C2H4 existing in measurable quantities in the polluted PBL, as implied by ground-based measurements. The typical 1–3 day lifetime of C2H4 at midlatitudes and low latitudes implies that it will only be measurable in the free troposphere soon after rapid uplift.

3.3 Comparison with remote sensing measurements

Paton-Walsh et al. (2005) measured up to 300 × 1015 molec cm−2 of C2H4 during fire events in southeast (SE) Australia in 2001–2003 with aerosol optical depths of up to 5.5 at 500 nm wavelength. From spectra acquired during one of the most intense of these fires (1 January 2002), Rinsland et al. (2005) retrieved a total C2H4 column of 380 ± 20 × 1015 through a dense smoke plume and inferred a huge mole fraction of 37 ppb peaking at about 1 km above ground level. This retrieval used information from the shape of the Q-branch feature, which was nearly as deep as the overlapping CO2 line. These C2H4 amounts are 20 times larger than anything seen by MkIV, even from polluted JPL.

Coheur et al. (2007) reported a C2H4 VMR of 70 ± 20 ppt at 11.5 km altitude in a biomass burning plume, observed by the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE) (Bernath et al., 2005) off the east coast of Africa. They also show measured C2H4 exceeding 100 ppt below 8 km. Simultaneous measurement of elevated C2H2, CO, C2H6, HCN, and HNO3 confirm their biomass burning hypothesis.

Figure 8MkIV C2H4 profiles from 24 balloon flights color-coded by year (purple is 1989, green is 2000, and red is 2014). Altitude offsets of up to 0.4 km have been applied for clarity, to prevent the error bars from over-writing each other at each integer altitude. In only one flight, launched in December 1999 from Esrange, Sweden, was a significant amount of C2H4 measured (green points at 6–7 km altitude). In other flights there was no detection, with upper limits varying from 10 to 15 ppt. The increase in uncertainty with altitude above 10 km is due to the C2H4 absorption feature weakening in comparison with the spectral noise. Below 10 km the increasing uncertainty is due to the greater interference by H2O and CO2. Note that the negative C2H4 values are all associated with large uncertainties.

Herbin et al. (2009) reported zonal average ethene profiles above 6 km altitude based on global measurements by ACE. Figure 2 of Herbin et al. (2009) shows 35∘ N zonal average VMRs of 40 ppt at 6 km altitude, 30 ppt at 8 km, and 15 ppt at 14 km altitude, with error bars as small as 1 ppt. Herbin et al. (2009) also wrote to following: “We find that a value of 20 ppt is close to the detection threshold at all altitudes in the troposphere”. To reconcile these two statements we assume that the 20 ppt detection limit refers to a single occultation, whereas the 1 ppt error bar is the result of co-adding hundreds of ACE profiles.

Herbin et al. (2009) also report increasing C2H4 with latitude. Although the ACE zonal means agree with the in situ measurements made during the PEM-West and TRACE-P, these campaigns were designed to measure the outflow of Asian pollution and therefore sampled some of the worst pollution on the planet. Therefore, one would expect lower values in a zonal average. Based on the total absence of negative values in any of their retrieved VMR profiles, we believe that Herbin et al. performed a log(VMR) retrieval, imposing an implicit positivity constraint. This would have led to a noise-dependent, high bias in their retrieved profiles in places where C2H4 was undetectable.

Clerbeaux et al. (2009) reported C2H4 column abundances reaching 3 × 1015 molec cm−2 from spectra acquired by the IASI satellite instrument, a nadir-viewing emission sounder. This isolated event occurred in May 2008 over East Asia and was associated with a Siberian fire plume, as confirmed by back trajectories and co-located enhancements of CH3OH, HCOOH, and NH3.

More recently, C2H4 was detected in boreal fire plumes (Alvarado et al., 2011; Dolan et al., 2016) during the 2008 ARCTAS mission by the Tropospheric Emission Spectrometer (TES), a nadir-viewing thermal emission FTS on board the Aura satellite. A strong correlation with CO was observed. TES's C2H4 sensitivity depends strongly on the thermal contrast: the temperature of the C2H4 relative to that of the underlying surface. For plumes in the free troposphere a detection limit of 2–3 ppb is claimed from a single sounding with a 5 × 8 km footprint.

3.4 Comparison with in situ measurements

There are a lot of published in situ ethene measurements. Here we intend to discuss only those that are in some way comparable with MkIV measurements. These include measurements over the western United States and profiles over the Pacific Ocean in the 30–40∘ N latitude range that are upwind of MkIV balloon measurements. Other measurements, e.g., over Europe and mainland SE Asia, are less relevant, given the 1–3 day lifetime of C2H4.

Gaffney et al. (2012) reported surface C2H4 over Texas and neighboring states measured in 2002. They reported a median VMR of 112 ppt, with occasionally much larger values of up to 2 ppb, presumably when downwind of local sources. This median value, if present only within a PBL that is 150 mbar thick, represents a total column of 0.3 × 1015 molec cm−2, which would be undetectable in ground-based MkIV measurements, consistent with the non-detection of C2H4 from Ft. Sumner, New Mexico (1.2 km).

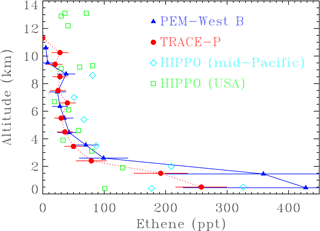

Figure 9Aircraft in situ measurements of ethene. HIPPO measurements of C2H4 made by the Advanced Whole Air Sampler between 30 and 40∘ N are shown by cyan diamonds (mid-Pacific) and green squares (central United States). Also shown are PEM-West B (blue triangles) and TRACE-P (red circles) measurements of C2H4 over coastal SE Asia and the western Pacific (taken from Fig. 9 of Blake et al., 2003).

Lewis et al. (2013) reported airborne in situ measurements of non-methane organic compounds over SE Canada in summer 2010. The median ethene VMR was 49 ppt, with plumes averaging 1848 ppt. Their C2H4 ∕ CO scatter plot (Fig. 2b of Lewis et al., 2013) reveals two distinct branches. Biomass burning plumes show an emission ratio of 6.97 ppt ppb−1, whereas local/anthropogenic emissions show an emission ratio of about 1.3 ppt ppb−1. These values bracket the MkIV value of 3.7 ± 0.4 ppt ppb−1 obtained from the green points in Fig. 5a and all points of Fig. 6 of the current paper.

Blake et al. (2003) report mean C2H4 profiles from 0 to 12 km during the February–April 2001 TRACE-P aircraft campaign, during which aircraft based in Hong Kong and Tokyo sampled outflow from SE Asia. Blake et al. (2003) compared these results with those from the similar 1991 and 1994 PEM-West campaigns. Figure 11 in Blake et al. shows that below 2 km, C2H4 averaged 100 ppt during TRACE-P and 250 ppt during PEM-West. Blake et al.'s Table 1 provides a median C2H4 of 30 ppt at 35∘ N at 2–8 km altitude in the western Pacific for both TRACE-P and PEM-West. Below 2 km the VMRs were much larger, especially during PEM-West. Blake et al.'s Fig. 9 shows mean PBL VMRs of 200 ppt during TRACE-P and 400 ppt during PEM-West, rapidly decreasing to 50 ppt by 4 km altitude, 30 ppt by 6 km, and less than 20 ppt above 9 km. Blake et al.'s Fig. 2 shows high C2H4 in the coastal margins of China, decreasing rapidly by a few hundred kilometers off shore, consistent with the short C2H4 lifetime. Since these aircraft campaigns were designed to measure polluted outflow from East Asia, the most polluted region on the planet, their samples cannot be considered representative of a zonal average. Over the mid-Pacific, C2H4 amounts were 0–15 ppt at all altitudes during TRACE-P and PEM-West B.

Sather and Cavender (2016) reported surface in situ measurements of ozone and volatile organic compounds (including ethene) from the cities of Dallas-Ft. Worth, Houston, El Paso, Texas, and from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, over the past 30 years. For ethene the measurements span the late 1990s to 2015, but nevertheless show clear declines by factors of 2–4 during 05:00–08:00 on weekdays. The authors attribute this decrease to the impacts of the 1990 amendment to the US Clean Air Act.

Ethene was measured during the HIAPER Pole-to-Pole (HIPPO; Wofsy et al., 2011, 2012) mission by the Advanced Whole Air Sampler. Figure 9 plots the C2H4 VMRs measured in the 30–40∘ N latitude range. Points are color-coded by longitude. The cyan points were measured in the mid-Pacific in January and December 2009, April 2010, and June and July 2011. The green points were measured over the central and western United States in January and December 2009, and June and July 2011. Profiles from the PEM-West B and TRACE-C aircraft campaigns are plotted in red and blue. Surprisingly, C2H4 is larger over the mid-Pacific (blue/purple points) than the United States (red points) at altitudes below 9 km. This is presumably due to Asian pollution being further destroyed while crossing the eastern Pacific. Above 9 km the C2H4 is larger over the United States, presumably due to upward transport of the Asian pollution.

Washenfelder et al. (2011) performed ground-based in situ measurements from Pasadena, California, of several glyoxal precursors in early June 2010, as part of the CalNEX 2010 campaign. An ethene mole fraction of 2.16 ppb was reported. Assuming that this value was present throughout the PBL, extending from the surface at 1000 mbar to the 900 mbar level, then the in situ measurement implies a total C2H4 column of 4 × 1015 molec cm−2, which is consistent with the upper range of values observed by MkIV in 2010. Unfortunately we do not have temporally overlapping measurements, and even if we did, JPL is 10 km away from the Pasadena site.

Washenfelder et al. (2011) also report a factor 6 drop in C2H4 amounts since the September 1993 CalNEX campaign, but note that the 1993 readings occurred during a smog episode, implying levels of pollution higher than normal. This drop is larger than the factor 3 decrease seen in the MkIV column data, but not inconsistent given the sparse statistics together with the large day-to-day variability seen in the MkIV data.

Measurements of ethene from ground level in Mexico City in 1999, 2002, and 2003 ranged between 10 and 60 ppb, with higher levels in the commercial sectors and lower values in residential areas (Altuzar et al., 2001, 2005; Velasco et al., 2007). These are 5–30 times larger than the 2.16 ppb measured by Washenfelder et al. (2011) in Pasadena in 2010.

The simultaneous reductions in CO and C2H4 ground-based column amounts measured from JPL over the past 25 years, and their continued high correlation, suggest a common source: vehicle exhaust. The declines in CO and C2H4 are likely a result of improved vehicle emission control systems, mandated by the increasingly stringent requirements imposed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA; e.g., the 1990 Clean Air Act), various state laws, and the California Air Resources Board (CARB, LEV2) over the past decades and stronger enforcement thereof (e.g., smog checks). This view is supported by Bishop and Stedman (2008) who showed that vehicle emissions of hydrocarbons in several US cities including Los Angeles have steadily decreased with vehicle model year since 1986.

C2H4 ∕ CO emission ratios measured over JPL by MkIV have decreased over the 30 year record, from 3.7 ± 0.4 ppt ppb−1 overall to 2.7 ± 0.4 ppt ppb−1 in recent years. It is not clear what is causing this decrease since many things have changed that might affect C2H4 levels (e.g., regulation of internal combustion engine exhaust, elimination of oil-based paints and lighter fuel, better control of emissions from oil and gas wells).

MkIV balloon measurements have only detected ethene once in 24 flights: in the Arctic in December 1999 at altitudes below 6 km. In all other flights an upper limit of 15 ppt was established for the free troposphere and 10 ppt for the lower stratosphere. These upper limits are substantially smaller than the ACE 35∘ N zonal mean profiles reported by Herbin et al. (2009), which are possibly biased high when C2H4 amounts are small due to a positivity constraint imposed on the retrievals. Also, a single biomass burning plume with up to 25 ppb of C2H4 has the potential to significantly increase the zonal mean C2H4. For this reason, a zonal median would be a more robust statistic. It is also possible that the MkIV balloon flights underrepresent conditions in which PBL pollution is lofted due to their location and the meteorology associated with balloon launches. Herbin et al. (2009) reported an increase of the 6 km ACE C2H4 with latitude in the Northern Hemisphere, peaking at 53 ppt at 70∘ N. This is consistent with the December 1999 MkIV balloon flight from 67∘ N, which measured 60 ppt at 6 km.

MkIV balloon measurements over the western United States reveal much smaller ethene amounts than in situ aircraft measurements over SE Asia during TRACE-P, PEM-West B, and over the mid-Pacific Ocean during HIPPO. With its 1–3-day lifetime, C2H4 decreases substantially during its eastward journey across the Pacific, which would help reconcile the in situ measurements with the MkIV balloon profiles.

A 30-year record of atmospheric C2H4 has been extracted from ground-based FTIR spectra measured by the JPL MkIV instrument. Despite its high sensitivity, MkIV only detects ethene at polluted urban sites (e.g., Pasadena, California). At clean sites visited by MkIV, C2H4 was undetectable (less than 1015 molec cm−2). MkIV ground-based measurements are generally consistent with the available surface in situ measurements, although a definitive comparison is difficult due to the large variability of C2H4 and lack of coincidence.

A large decline in C2H4 has been observed over Pasadena over the past 25 years. This is likely the result of increasingly stringent requirements on vehicle emissions imposed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (e.g., the 1990 Clean Air Act) and the California Air Resources Board (Low-Emission Vehicle 2 requirements) over the past decades, together with stronger enforcement of these regulations (e.g., smog checks). The C2H4 ∕ CO emissions ratio also appears to have decreased in recent years.

This work shows that C2H4 might in future become a routine product of the Network for the Detection of Atmospheric Composition Change (NDACC) infrared FTS network, at least at sites near large sources. Moreover, since the spectra are saved, a historical C2H4 record may be retro-actively extractable at some of the more polluted sites.

MkIV balloon profiles used in this study can be accessed from https://mark4sun.jpl.nasa.gov/m4data.html. MkIV ground-based column data used in this study can be accessed from http://mark4sun.jpl.nasa.gov/ground.html. These were last updated by the lead author (Geoffrey C. Toon) in 2017.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-5075-2018-supplement.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Twenty-five years of operations of the Network for the Detection of Atmospheric Composition Change (NDACC) (AMT/ACP/ESSD inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

This research was performed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California

Institute of Technology, under contract with the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration. We thank the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility

(CSBF) who conducted the majority of the balloon flights. We also thank the

CNES Balloon Launch facility who conducted two MkIV balloon flights from

Esrange, Sweden. We thank the Swedish Space Corporation for their support and

our use of their facilities. We thank the HIAPER Pole-to-Pole Observations

(HIPPO) campaign for use of their data. Finally, we acknowledge support from

the NASA Upper Atmosphere Research Program.

California Institute of Technology. Government sponsorship is acknowledged.

Edited by: Neil

Harris

Reviewed by: two anonymous referees

Abeles, F. B., Morgan, P. W., and Saltveit Jr., M. E.: Ethylene in Plant Biology, 2nd Edn., 414 pp., ISBN: 978-0-08-091628-6, 1992.

Altuzar, V., Pacheco, M., Tomas, S. A., Arriaga, J. L., Zelaya-Angel, O., and Sanchez Sinencio, F.: Analysis of ethylene concentration in the Mexico City atmosphere by photoacoustic spectroscopy, Anal. Sci., 17, 541–543, 2001.

Altuzar, V., Tomás, S. A., Zelaya-Angel, O., Sánchez-Sinencio, F., and Arriaga, J. L.: Atmospheric ethene concentrations in Mexico City: indications of strong diurnal and seasonal dependences, Atmos. Environ., 39, 5215–5225, 2005.

Alvarado, M. J., Cady-Pereria, K. E., Xiao, Y., Millet, D. B., and Payne, V. H.: Emission ratios for ammonia and formic acid and observations of peroxy acetyl nitrate (PAN) and ethylene in biomass burning smoke as seen by the tropospheric emission spectrometer (TES), Atmosphere, 2, 633–644, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos2040633, 2011.

Baker, A. K., Beyersdorf, A. J., Doezema, L. A., Katzenstein, A., Meinardi, S., Simpson, I. J., Blake, D. R., and Rowland, F. S.: Measurements of nonmethane hydrocarbons in 28 United States cities, Atmos. Environ., 42, 170–182, 2008.

Bernath, P. F., McElroy, C. T., Abrams, M. C., Boone, C. D., Butler, M., Camy-Peyret, C., Carleer, M., Clerbaux, C., Coheur, P. F., Colin, R., and DeCola, P., DeMazière, M., Drummond, J. R., Dufour, D., Evans, W. F. J., Fast, H., Fussen, D., Gilbert, K., Jennings, D. E., Llewellyn, E. J., Lowe, R. P., Mahieu, E., McConnell, J. C., McHugh, M., McLeod, S. D., Michaud, R., Midwinter, C., Nassar, R., Nichitiu, F., Nowlan, C., Rinsland, C. P., Rochon, Y. J., Rowlands, N., Semeniuk, K., Simon, P., Skelton, R., Sloan, J. J., Soucy, M.-A., Strong, K., Tremblay, P., Turnbull, D., Walker, K. A., Walkty, I., Wardle, D. A., Wehrle, V., Zander, R., and Zou, J.: Atmospheric chemistry experiment (ACE): mission overview, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L15S01, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL022386, 2005.

Bishop, G. A. and Stedman, D. H.: A Decade of On-road Emissions Measurements, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 1651–1656, https://doi.org/10.1021/es702413b, 2008.

Blake, N. J., Blake, D. R, Simpson, I. J., Meinardi, S., Swanson, A. L., Lopez, J. P., Katzenstein, A. S., Barletta, B., Shirai, T., Atlas, E., Sachse, G., Avery, M., Vay, S., Fuelberg, H. E., Kiley, C. M., Kita, K., and Rowland, F. S.: NMHCs and halocarbons in Asian continental outflow during the Transport and Chemical Evolution over the Pacific (TRACE-P) field campaign: Comparison with PEM-West B, J. Geophys. Res., 108, 8806, https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD003367, 2003.

Clerbaux, C., Boynard, A., Clarisse, L., George, M., Hadji-Lazaro, J., Herbin, H., Hurtmans, D., Pommier, M., Razavi, A., Turquety, S., Wespes, C., and Coheur, P.-F.: Monitoring of atmospheric composition using the thermal infrared IASI/MetOp sounder, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 6041–6054, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-6041-2009, 2009.

Coheur, P.-F., Herbin, H., Clerbaux, C., Hurtmans, D., Wespes, C., Carleer, M., Turquety, S., Rinsland, C. P., Remedios, J., Hauglustaine, D., Boone, C. D., and Bernath, P. F.: ACE-FTS observation of a young biomass burning plume: first reported measurements of C2H4, C3H6O, H2CO and PAN by infrared occultation from space, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 5437–5446, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-5437-2007, 2007.

Conley, S., Franco, G., Faloona, I., Blake, D. R., Peischl, J., and Ryerson, T. B.: Methane emissions from the 2015 Aliso Canyon blowout in Los Angeles, CA, Science, 351, 1317–1320, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2348, 2016.

Dolan, W., Payne, V. H., Kualwik, S. S., and Bowman, K. W.: Satellite observations of ethylene (C2H4) from the Aura Tropospheric Emission Spectrometer: A scoping study, Atmos. Environ., 141, 388–393, 2016.

Gaffney, J. S., Marley, N. A., and Blake, D. R.: Baseline measurements of ethene in 2002: Implications for increased ethanol use and biomass burning on air quality and ecosystems, Atmos. Environ., 56, 161–168, 2012.

Herbin, H., Hurtmans D., Clarisse L., Turquety S., Clerbaux C., Rinsland C. P., Boone C., Bernath P. F., and Coheur P.-F.: Distributions and seasonal variations of tropospheric ethene (C2H4) from Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (ACE-FTS) solar occultation spectra, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L04801, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL036338, 2009.

Hough, A. M.: Development of a two-dimensional global troposphere model: Model chemistry, J. Geophys. Res., 96, 7325–7362, 1991.

Irion, F. W., Gunson, M. R., Toon, G. C., Chang, A. Y., Eldering, A., Mahieu, E., Manney, G. L., Michelsen, H. A., Moyer, E. J., Newchurch, M. J., Osterman, G. B., Rinsland, C. P., Salawitch, R. J., Sen, B., Yung, Y. L., and Zander, R.: Atmospheric Trace Molecule Spectroscopy (ATMOS) Experiment Version 3 data retrievals, Appl. Opt., 41, 6968–6979, 2002.

Lewis, A. C., Evans, M. J., Hopkins, J. R., Punjabi, S., Read, K. A., Purvis, R. M., Andrews, S. J., Moller, S. J., Carpenter, L. J., Lee, J. D., Rickard, A. R., Palmer, P. I., and Parrington, M.: The influence of biomass burning on the global distribution of selected non-methane organic compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 851–867, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-851-2013, 2013.

Müller, J.-F. and Brasseur, G.: IMAGES: A three-dimensional chemical transport model of the global troposphere, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 100, 16445–16490, 1995.

Olivella, S. and Solé, A.: Unimolecular decomposition of β-hydroxyethylperoxy radicals in the HO-initiated oxidation of ethene: A theoretical study, J. Phys. Chem. A, 108, 11651–11663, 2004.

Paton-Walsh, C., Jones, N. B., Wilson, S. R., Haverd, V., Meier, A., Griffith, D. W. T., and Rinsland, C. P.: Measurements of trace gas emissions from Australian forest fires and correlations with coincident measurements of aerosol optical depth, J. Geophys. Res., 110, D24305, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JD006202, 2005.

Poisson, N., Kanakidou, M., and Crutzen, P. J.: Impact of Non-Methane Hydrocarbons on Tropospheric Chemistry and the Oxidizing Power of the Global Troposphere: 3-Dimensional Modelling Results, J. Atmos. Chem., 36, 157–230, 2000.

Rinsland, C., Paton-Walsh, C., Jones, N. B., Griffith, D. W., Goldman, A., Wood, S., Chiou, L., and Meier, A.: High Spectral resolution solar absorption measurements of ethylene (C2H4) in a forest fire smoke plume using HITRAN parameters: Tropospheric vertical profile retrieval, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 96, 301–309, 2005.

Rothman, L. S., Barbe, A., Chris Benner, D., Brown, L. R., Camy-Peyret, C., Carleer, M. R., Chance, K., Clerbaux, C., Dana, V., Devi, V. M., Fayt, A., Flaud, J.-M., Gamache, R. R., Goldman, A., Jacquemart, D., Jucks, K. W., Lafferty, W. J., Mandin, J.-Y., Massie, S. T., Nemtchinov, V., Newnham, D. A., Perrin, A., Rinsland, C. P., Schroeder, J., Smith, K. M., Smith, M. A. H., Tang, K., Toth, R. A., Vander Auwera, J., Varanasi, P., Yoshino, K.,: The HITRAN molecular spectroscopic database: edition of 2000 including updates through 2001, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 82, 5–44, 2003.

Rothman, L. S., Gordon, I. E., Babikov, Y., Barbe, A., Chris Benner, D., Bernath, P. F., Birk, M., Bizzocchi, L., Boudon, V., Brown, L. R., Campargue, A., Chance, K., Cohen, E. A., Coudert, L. H., Devi, V. M., Drouin, B. J., Fayt, A., Flaud, J.-M., Gamache, R. R., Harrison, J. J., Hartmann, J.-M., Hill, C., Hodges, J. T., Jacquemart, D., Jolly, A., Lamouroux, J., Le Roy, R. J., Li, G., Long, D. A., Lyulin, O. M., Mackie, C. J., Massie, S. T., Mikhailenko, S., Müller, H. S. P., Naumenko, O. V., Nikitin, A. V., Orphal, J., Perevalov, V., Perrin, A., Polovtseva, E. R., Richard, C., Smith, M. A. H., Starikova, E., Sung, K., Tashkun, S., Tennyson, J., Toon, G. C., Tyuterev, V. I. G., and Wagner, G.: The HITRAN2012 Molecular Spectroscopic Database, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 130, 4–50, 2013.

Sather, M. E. and Cavender, K.: Trends analyses of 30 years of ambient 8 hour ozone and precursor monitoring data in the South Central U.S.: progress and challenges, Environ. Sci. Process Impacts, 18, 819–831, 2016.

Sawada, S. and Totsuka, T.: Natural and anthropogenic sources and fate of atmospheric ethylene, Atmos. Environ., 20, 821–832, https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(86)90266-0, 1986.

Sen, B., Toon, G. C., Blavier, J.-F., Fleming, E. L., and Jackman, C. H.: Balloon-borne observations of mid-latitude fluorine abundance, J. Geophys. Res., 101, 9045–9054, 1996.

Toon, G. C.: The JPL MkIV Interferometer, Opt. Photonics News, 2, 19–21, 1991.

Toon, G. C.: Telluric line list for GGG2014, TCCON data archive, hosted by CaltechDATA, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, https://doi.org/10.14291/tccon.ggg2014.atm.R0/1221656, 2014a.

Toon, G. C.: Solar line list for GGG2014. TCCON data archive, hosted by CaltechDATA, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, https://doi.org/10.14291/tccon.ggg2014.solar.R0/1221658, 2014b.

Toon, G. C., Blavier, J.-F., Sen, B., Salawitch, R. J., Osterman, G. B., Notholt, J., Rex, M., McElroy, C. T., and Russell, J. M.: Ground-based observations of Arctic O3 loss during spring and summer 1997, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 26497–26510, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JD900745, 1999a.

Toon, G. C., Blavier, J.-F., Sen, B., Margitan, J. J., Webster, C. R., May, R. D., Fahey, D. W., Gao, R., Del Negro, L., Proffitt, M., Elkins, J., Romashkin, P. A., Hurst, D. F., Oltmans, S., Atlas, E., Schauffler, S., Flocke, F., Bui, T. P., Stimpfle, R. M., Bonne, G. P., Voss, P. B., and Cohen, R. C.: Comparison of MkIV balloon and ER-2 aircraft profiles of atmospheric trace gases, J. Geophys. Res., 104, 26779–26790, 1999b.

Toon, G. C., Blavier, J.-F., Sung, K., Rothman, L. S., and Gordon, I.: HITRAN spectroscopy evaluation using solar occultation FTIR spectra, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 182, 324–336, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2016.05.021, 2016.

Velasco, E., Lamb, B., Westberg, H., Allwine, E., Sosa, G., Arriaga-Colina, J. L., Jobson, B. T., Alexander, M. L., Prazeller, P., Knighton, W. B., Rogers, T. M., Grutter, M., Herndon, S. C., Kolb, C. E., Zavala, M., de Foy, B., Volkamer, R., Molina, L. T., and Molina, M. J.: Distribution, magnitudes, reactivities, ratios and diurnal patterns of volatile organic compounds in the Valley of Mexico during the MCMA 2002 & 2003 field campaigns, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 329–353, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-329-2007, 2007.

Velazco, V. A., Toon, G. C., Blavier, J.-F. L., Kleinbohl, A., Manney, G. L., Daffer, W. H., Bernath, P. F., Walker, K. A., and Boone, C.: Validation of the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment by noncoincident MkIV balloon profiles, J. Geophys. Res., 116, D06306, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD014928, 2011.

Warneke, C., McKeen, S. A., De Gouw, J. A., Goldan, P. D., Kuster, W. C., Holloway, J. S., Williams, E. J., Lerner, B., Parrish, D. D., Trainer, M., Fehsenfeld, F. C., Kato, S., Atlas, E. L., Baker, A., and Blake, D. R.: Determination of urban volatile organic compound emission ratios and comparison with an emissions database, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 112, D10S47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD007930, 2007.

Warneke, C., de Gouw, J. A., Holloway, J. S., Peischl, J., Ryerson, T. B., Atlas, E., Blake, D., Trainer, M., and Parrish, D. D.: Multiyear trends in volatile organic compounds in Los Angeles, California: Five decades of decreasing emissions, J. Geophys. Res., 117, D00V17, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JD017899, 2012.

Washenfelder, R. A., Young, C. J., Brown, S. S., Angevine, W. M., Atlas, E. L., Blake, D. R., Bon, D. M., Cubison, M. J., de Gouw, J. A., Dusanter, S., Flynn, J., Gilman, J. B., Graus, M., Griffith, S., Grossberg, N., Hayes, P. L., Jimenez, J. L., Kuster, W. C., Lefer, B. L., Pollack, I. B., Ryerson, T. B., Stark, H, Stevens, P. S., and Trainer, M. K.: The glyoxal budget and its contribution to organic aerosol for Los Angeles, California, during CalNex 2010, J. Geophys. Res., 116, D00V02, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016314, 2011.

Wofsy, S. C., the HIPPO Science Team, and Cooperating Modellers and Satellite Teams: HIAPER Pole-to-Pole Observations (HIPPO): fine-grained, global-scale measurements of climatically important atmospheric gases and aerosols, Philos. T. R. Soc. A, 369, 2073–2086, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0313, 2011.

Wofsy, S. C., Daube, B. C., Jimenez, R., Kort, E., Pittman, J. V., Park, S., Commane, R., Xiang, B., Santoni, G., Jacob, D., Fisher, J., Pickett-Heaps, C., Wang, H., Wecht, K., Wang, Q.-Q., Stephens, B. B., Shertz, S., Watt, A. S., Romashkin, P., Campos, T., Haggerty, J., Cooper, W. A., Rogers, D., Beaton, S., Hendershot, R., Elkins, J. W., Fahey, D. W., Gao, R. S., Moore, F., Montzka, S. A., Schwarz, J. P., Perring, A. E., Hurst, D., Miller, B. R., Sweeney, C., Oltmans, S., Nance, D., Hintsa, E., Dutton, G., Watts, L. A., Spackman, J. R., Rosenlof, K. H., Ray, E. A., Hall, B., Zondlo, M. A., Diao, M., Keeling, R., Bent, J., Atlas, E. L., Lueb, R., and Mahoney, M. J.: HIPPO Merged 10-second Meteorology, Atmospheric Chemistry, Aerosol Data (R_20121129), Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA, https://doi.org/10.3334/CDIAC/hippo_010 (Release 20121129), 2012.

Wunch, D., Toon, G. C., Blavier, J.-F. L., Washenfelder, R. A., Notholt, J., Connor, B. J., Griffith, D. W. T., Sherlock, V., and Wennberg, P. O.: The total carbon column observing network, Philos. T. R. Soc. A, 369, 2087–2112, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0240, 2011.

Xue, L., Wang, T., Simpson, I. J., Ding, A., Gao, J., Blake, D. R., Wang, X., Wanga, W., Lei, H., and Jin, D.: Vertical distributions of non-methane hydrocarbons and halocarbons in the lower troposphere over northeast China, Atmos. Environ., 45, 6501–6509, 2011.