the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Direct effect of aerosols on solar radiation and gross primary production in boreal and hemiboreal forests

Ekaterina Ezhova

Ilona Ylivinkka

Joel Kuusk

Kaupo Komsaare

Marko Vana

Alisa Krasnova

Steffen Noe

Mikhail Arshinov

Boris Belan

Sung-Bin Park

Jošt Valentin Lavrič

Martin Heimann

Tuukka Petäjä

Timo Vesala

Ivan Mammarella

Pasi Kolari

Jaana Bäck

Üllar Rannik

Veli-Matti Kerminen

Markku Kulmala

The effect of aerosol loading on solar radiation and the subsequent effect on photosynthesis is a relevant question for estimating climate feedback mechanisms. This effect is quantified in the present study using ground-based measurements from five remote sites in boreal and hemiboreal (coniferous and mixed) forests of Eurasia. The diffuse fraction of global radiation associated with the direct effect of aerosols, i.e. excluding the effect of clouds, increases with an increase in the aerosol loading. The increase in the diffuse fraction of global radiation from approximately 0.11 on days characterized by low aerosol loading to 0.2–0.27 on days with relatively high aerosol loading leads to an increase in gross primary production (GPP) between 6 % and 14 % at all sites. The largest increase in GPP (relative to days with low aerosol loading) is observed for two types of ecosystems: a coniferous forest at high latitudes and a mixed forest at the middle latitudes. For the former ecosystem the change in GPP due to the relatively large increase in the diffuse radiation is compensated for by the moderate increase in the light use efficiency. For the latter ecosystem, the increase in the diffuse radiation is smaller for the same aerosol loading, but the smaller change in GPP due to this relationship between radiation and aerosol loading is compensated for by the higher increase in the light use efficiency. The dependence of GPP on the diffuse fraction of solar radiation has a weakly pronounced maximum related to clouds.

- Article

(5136 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

According to the IPCC report (Pachauri et al., 2014), the influence of aerosol loading on solar irradiance remains a relevant, open question. Aerosol particles influence the radiative balance of the Earth due to aerosol–radiation and aerosol–cloud interactions. The aerosol–radiation interactions include the scattering and absorption of solar radiation (direct effect), and potential changes in cloud properties associated with these radiative effects (semi-direct effect). Another important consequence of aerosol–radiation interactions is an increase in the diffuse fraction of solar radiation entering the Earth surface.

The influence of aerosol–radiation interactions on the diffuse fraction of solar radiation is relevant for estimates of the terrestrial carbon sink and for understanding climate feedback mechanisms (Kulmala et al., 2014). The increase in the land carbon sink due to enhanced industrial aerosols was estimated to be 20 %–25 % during the period of “global dimming” between 1960 and 1999 in the modelling study by Mercado et al. (2009). The physical mechanism behind the growth of the terrestrial carbon sink is as follows. An increased diffuse fraction of solar irradiance due to aerosols makes it easier for light photons to penetrate into the canopy. Moreover, diffuse light coming from different angles increases the efficiency of CO2 uptake by leaves of different orientation (Alton et al., 2007). This leads to an increase in the light use efficiency (LUE) of plants, which quantifies the amount of CO2 fixed by an ecosystem per unit of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), and gross primary production (GPP), which quantifies the amount of CO2 fixed by an ecosystem per unit area per unit time. However, this mechanism is ecosystem-dependent and presumably depends on canopy height and the leaf area index (LAI) (Cheng et al., 2015; Kanniah et al., 2012; Niyogi et al., 2004): an enhanced diffuse radiation does not lead to an increase in grasslands' GPP, while GPP of broadleaf forests can be significantly increased. Similarly, a study based on AmeriFlux data from several sites (Cheng et al., 2015), including broadleaf forests and crops, suggested an increase in GPP due to diffuse radiation for forests but not for crops.

Estimates of the aerosol effect on GPP are uncertain for two reasons. First, it is not clear how large the effect of aerosols is on diffuse radiation. Second, the associated effect of diffuse radiation on GPP can be both negative and positive (Alton, 2008; Niyogi et al., 2004; Park et al., 2018). Therefore, aerosol–radiation interactions may either lead to an increase or a decrease in GPP, depending on aerosol loading. As an example, Niyogi et al. (2004) reports an increase in GPP for broadleaf forests at any aerosol loading typical for the sites they considered. On the contrary, a recent model study suggests that for a substantial proportion of boreal forests in the territories of Finland, Estonia and Russia, the direct aerosol effect at relatively high aerosol loading leads to a decrease in the annual diffuse irradiance and GPP (Lu et al., 2017). Estimates on the effects of solar radiation on GPP have often been obtained by utilizing parameterizations (Alton, 2008) or based on the results of numerical modelling and satellite observations (Lu et al., 2017). The aims of this study are to provide a comprehensive data analysis related to the direct effect of aerosol on solar radiation, to separate cloud and aerosol effects on solar irradiance, and to further quantify the influence of solar radiation on GPP. The data sets include continuous field measurements from five stations in Finland, Estonia and Russia.

Note that this analysis can be put into a broader context regarding the quantification of terrestrial feedback loops, e.g. the COntinental Biosphere–Atmosphere–Cloud–Climate (COBACC) feedback loop (Kulmala et al., 2014). This loop considers the effect of the carbon dioxide concentration on biogenic volatile organic compound emissions (BVOC), further relates BVOC-aerosol interactions to the variability in solar radiation and finally the loop is closed with the effects of radiation for the ecosystem GPP and CO2 concentration. Here we provide a quantification of the part of this loop related to aerosol–solar radiation–photosynthesis interactions in boreal and hemiboreal forests.

In line with the aims of this study, we focus on two problems: (1) aerosol–radiation interactions, for which we quantify the diffuse fraction of solar radiation that can be observed due to the direct aerosol effect, and (2) the diffuse radiation effect on photosynthesis. First, we quantify the effect of aerosol–radiation interactions on diffuse radiation in boreal forests. For the estimates of the effect of aerosol on solar radiation it is important to separate clear times of the day from cloudy periods, because clouds are much more effective than aerosols with respect to scattering solar irradiance. In some previous studies (Gu et al., 2002; Kulmala et al., 2014) this separation was made based on the ratio of measured global irradiance to theoretically calculated global irradiance at the top of the atmosphere. This criterion of clear days can indeed be acceptable when one needs to distinguish between mostly sunny/mostly cloudy days with respect to the incoming global irradiance or the incoming solar energy. However, it fails to separate sunny/cloudy periods from the point of view of the amount of diffuse irradiance, which is crucially important for photosynthesis. Generally, radiation data used for analyses is averaged over a time interval (often 30 min). Some types of clouds, such as cumulus, are rather intermittent with oscillation periods of several minutes (Duchon and O'Malley, 1999). During the periods when there is no cloud in front of the sun, global irradiance can be even higher than theoretically predicted due to a global radiation enhancement (Pecenak et al., 2016). As a result, an averaged global irradiance can be close to that theoretically predicted for the clear sky, while averaged diffuse irradiance is significantly enhanced at the same time due to the presence of clouds. Such data can be erroneously attributed to clear-sky conditions, meaning that the effects of clouds on the diffuse radiation can be associated with the direct aerosol effect. These kinds of conditions are most likely to cause the highest GPP, as global irradiance does not decrease while diffuse irradiance is already high. Second, we consider the effect of solar radiation on GPP. We investigate the effect of the diffuse fraction of solar radiation on the LUE and further quantify the maximum effect on GPP due to aerosol–radiation interactions for different ecosystems in a boreal forest.

In this section we introduce data sets and methods used in the study. In Sect. 2.1 we present the sites and data sets. Section 2.2 describes the clear-sky model used to separate clear sky and clouds. We discuss the consequences of having different (PAR or broadband) radiation measurements at different sites in Sect. 2.3 and suggest a method to make the data sets comparable. In Sect. 2.4 we introduce the condensation sink as a measure of aerosol loading. Finally, Sect. 2.5 describes the method used to study the diffuse radiation effect on ecosystem GPP using a separation of GPP into the LUE and the PAR.

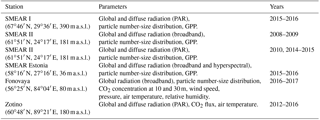

2.1 Sites and data sets

We used data from five remote forest sites located at the middle and relatively high latitudes in Finland, Estonia and Russia: SMEAR I (Värriö, Finland), SMEAR II (Hyytiälä, Finland), SMEAR Estonia (Järvselja, Estonia), Zotino (Zotino, Krasnoyarsk region, Russia) and Fonovaya (Tomsk region, Russia). Figure 1 illustrates the sites' locations on the map, while Table 1 summarizes information on the data sets used in the present study. The information regarding the instruments used can be found in separate papers that describe the stations (listed below) and on the AVAA Internet site for SMEAR I and II (https://avaa.tdata.fi/web/smart, last access: 30 June 2018).

SMEAR II (Hari and Kulmala, 2005) is located at Hyytiälä Forestry Field Station in a conifer boreal forest near a lake in central Finland. The site is a managed, 55-year old Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) forest stand with a closed canopy and an average tree height of ca. 18 m.

SMEAR I (Hari et al., 1994) is the site characterized by the highest latitude and is located in Finnish Lapland. The site is comprised of ca. 60-year old Scots pines with a rather open canopy. The average tree height is ca. 10 m.

SMEAR Estonia (Noe et al., 2015) is located in a hemiboreal forest zone and the stands in the tower footprint consist of a mixture of coniferous, Scots pine and Norway spruce (Picea abies L. Karst), and deciduous, silver birch (Betula pendula Roth.) and downy birch (Betula pubescens Ehrh.), trees. Because of the high heterogeneity and the mosaic of stands of hemiboreal forests the stand age is 65-years old on average ranging from 43-year old larch stands to 120-year old pine stands. The average ages of the dominating species are 102 years for pine, 79 years for spruce and 68 years for birch. Therefore, the tree height is variable: 22 m on average (ranging between 10 and 30 m).

Fonovaya in the Tomsk region is the most southern site (Matvienko et al., 2015). It is located on the Ob River in western Siberia, Russia, and forest stand is represented by mixed forest. The stand is dominated by 50-year old Scots pine, 45-year old birch (Betula verrucósa) and 27-year old aspen (Populus tremula). The average tree height is ca. 30 m, ranging from 25 m for birch up to 40 m for pines.

Zotino (Heimann et al., 2014; Park et al., 2018) is located near the Yenisei River in central Siberia. The forest is dominated by a 100-year old Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) forest stand with an open canopy and an average canopy height of ca. 20 m.

Thus, we have data sets from five sites with three of them represented by pine stands and two represented by mixed forests; all of the sites are located at mid-latitudes. Note that currently the data from these five stations form the largest possible set of simultaneous atmospheric observations on trace gases, meteorology, solar radiation and aerosols, conducted in boreal and hemiboreal forests in Eurasia. Some of these sites lack certain components necessary for the analysis and therefore we use parameterizations when needed (and possible). For example, the diffuse fraction of solar radiation, fdifbb, was parameterized in the data set from Fonovaya. Following Gu et al. (2002) and Alton (2008), we used the formula

where Rd is diffuse radiation, Rg is global radiation and is the ratio of the measured global radiation to the modelled radiation at the top of atmosphere. For x<0.28 we used fdifbb=0.95, and for x>0.75 we used fdifbb=0.1. The radiation at the top of atmosphere was calculated as RTOA=I0cos(sza), where I0 is the solar constant and sza is the solar zenith angle.

The data used in this study correspond to the peak growing season defined as the time period with maximum GPP. Typically it includes June–August and part of May and September for all the sites except SMEAR I, where it includes July–August and part of June and September. For consistency, we used June–August data for SMEAR II, SMEAR Estonia, Fonovaya and Zotino and July–August data for SMEAR I. The analysis was performed for daytime (09:00–15:00 local time), 30 min averaged data.

The aerosol number-size distribution at Fonovaya was measured using two instruments, which do not overlap with respect to the size range. Therefore, there is a gap between 200 and 300 nm in the distribution. This gap was filled with an average value between the two adjacent points (one point was added between the two points). Apart from that, we did not apply gap-filling for aerosol data in this study, and used only good quality data. We did not fill gaps in the solar radiation data.

Note, that the CO2 flux was obtained by the micrometeorological (eddy covariance) method at the SMEAR stations and Zotino, while the gradient method was applied to obtain the CO2 flux from the Fonovaya data set. GPP was calculated using the following formula:

where TER is the total ecosystem respiration and NEE is the net ecosystem exchange. TER was obtained for all ecosystems using the nighttime method of CO2 flux partitioning (Reichstein et al., 2005). The partitioning method at SMEAR I and II was based on soil temperature which makes the method more precise (Kolari et al., 2009; Lasslop et al., 2012), while at other sites it was based on air temperature (soil temperature is not measured). According to Lasslop et al. (2012), a possible consequence of an average GPP calculated during daytime (09:00–15:00), is a decrease in GPP calculated using soil temperature of about 0.5 µmol s−1 m−2 compared with GPP calculated using air temperature. In addition, in the data sets from the SMEAR stations absent GPP points were modelled (Kolari et al., 2009), while in the data sets from the Russian stations we did not fill the gaps. For the Zotino data set a good data percentage was 55 % on average (Park et al., 2018), and for the Fonovaya data set it was approximately 30 %.

Studying aerosol–radiation interactions, we used the Solis clear-sky model (see more in Sect. 2.2). The input parameters for this model are the aerosol optical depth at 700 nm (AOD700) and precipitable water (PW). We used AOD at 675 nm and PW from AERONET (Holben et al., 1998); in particular, data from the following AERONET sites were used: Hyytiala (for SMEAR II), Sodankyla (for SMEAR I), Tomsk22 (for Fonovaya) and Toravere (for SMEAR Estonia). The AERONET sites are in the immediate vicinity of the Fonovaya and SMEAR II stations, SMEAR Estonia is 50 km from Toravere and SMEAR I is approximately 70 km from Sodankyla. We used Version 2, Level 2 data (cloud screened and quality controlled), except for Tomsk22 where we used Version 3, Level 2 data. The input data were averaged over daytime.

Currently aerosol characteristics are not measured at Zotino and there are no AERONET sites nearby; therefore aerosol–radiation interactions have not been studied for Zotino. However, radiation and CO2 flux, which are necessary for the radiation–photosynthesis analysis, are measured; consequently, the Zotino data set has been included in this study.

2.2 The Solis clear-sky model

To distinguish between the effects of aerosols and clouds on solar radiation, we used a simplified broadband version of a clear-sky radiative transfer model (RTM) – Solis (Ineichen, 2008). This is a quasi-physical model which means that it employs Lambert–Beer relations for the general estimates of irradiance while using parameterizations for the total optical depths. The input parameters are the aerosol optical depth at 700 nm (AOD700) and precipitable water (PW). Parameterizations are developed for the following range of parameters: sea level < altitude < 7000 m, 0 < AOD700 < 0.45 and 0.2 cm < PW < 10 cm.

Solis parameterizations were obtained using the “urban” type of aerosol size distribution in the full RTM (Ineichen, 2008). The difference between calculations for “urban” and “rural” types of aerosol for the same AOD700=0.18 was reported by Mueller et al. (2004). This AOD700 value is larger than the typical values for all of the places that we consider in this study; hence, we expect smaller errors due to the inconsistent aerosol type. The difference reported by Mueller et al. (2004) was negligible for direct irradiance, whereas global irradiance for “rural” aerosol was around 20 W m−2 larger during the daytime. Given that for clear-sky conditions between 09:00 and 15:00 and during the growing season, global irradiance drops to ∼600 W m−2, this difference introduces a maximum error of 3 %. More tests for several sites in the USA and comparison between Solis and two more simplified clear-sky models, Bird and REST2, were reported by Sengupta and Gotseff (2013). Solis is the optimal model from the point of view of the required parameters: it performs only slightly worse than the other two models, and it requires only two input parameters.

We used Solis to model both global and diffuse irradiance. The horizontal global irradiance, Igh, was calculated as follows:

while the direct irradiance, Idir, was calculated as

Here is a common modified (enhanced) irradiance defined in Ineichen (2008), τb and τg are the direct and global total optical depths, respectively, b and g are the fitting parameters, and sza is the solar zenith angle. Diffuse radiation can be found from the global radiation balance using the following equation:

All of the parameterizations used in the model are given in Ineichen (2008). The algorithm used for the calculations is written in Fortran. For the calculation of the sza, the online calculator Solar Position Algorithm (SPA) was used (available from http://www.nrel.gov, last access: 22 February 2018).

2.3 Accounting for the difference between PAR and broadband radiation

Note that the measurement methods of solar radiation are different at the different sites. At SMEAR II before 2009 and Fonovaya only broadband radiation is measured, while at SMEAR I and Zotino only photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) is measured. At SMEAR II after 2009 both global PAR and broadband global radiation, as well as diffuse PAR are measured. Broadband shortwave radiation, referred to as broadband radiation, is the radiation in the spectral range between 0.3 and 4.8 µm, while PAR is the radiation relevant for photosynthesis, i.e. in the range of wavelengths between 400 and 700 nm. The former is typically measured using thermopile pyranometers (energy sensors) and reported in energy units (W m−2), while the latter is measured using quantum sensors and is reported in quantum units (µmol s−1 m−2).In the following, we quantify the ratio between global PAR and global broadband radiation, and the ratio between the diffuse fraction of PAR and the diffuse fraction of broadband radiation.

Following Ross and Sulev (2000), the ratio of PAR (µmol s−1 m−2) to the broadband radiation (W m−2) is called the PAR quantum efficiency χ. By dividing global PAR by broadband global radiation at SMEAR II and finding its mean value (the values were obtained for the growing season and years listed in Table 1), χglob=2.06 µmol s−1 W−1 was obtained, and was somewhat higher than 1.81 µmol s−1 W−1 reported by Ross and Sulev (2000) for Estonia.

We explain the potential difference between the diffuse fraction of PAR and the diffuse fraction of broadband radiation as follows. Aerosol particles influence a certain part of the spectra of solar irradiance depending on the particle size distribution (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). This effect can be better understood using a dimensionless size parameter πdp∕λ, where λ is the wavelength of incident irradiance and dp is the particle diameter. If , then Rayleigh scattering is prevailing, while means that the scattering properties of the particles are determined by the geometrical optics, i.e., so-called “geometric scattering”. The characteristics of the aerosol distribution become important for solar irradiance if . For boreal forests where the particle size distribution is typically governed by the well-pronounced mode with the geometric mean diameter dp≈100 nm (Dal Maso et al., 2008), the effective interaction of aerosols with solar radiation occurs in the ultraviolet range (100–400 nm) and in the blue part of the optical spectrum (400–500 nm). Compared to PAR (400–700 nm), the essential part of the broadband radiation energy is contained in the near infrared part of the spectrum (700–1400 nm), which is not affected by the relatively small particles prevailing in aerosol distributions typical for boreal forest. In other words, the effect of aerosols on the diffuse fraction of solar irradiance can be different for PAR and broadband radiation. Qualitatively, one would expect that both the increase in diffuse radiation and the decrease in global radiation would be more pronounced for PAR, meaning that the diffuse fraction of PAR would be higher under the same aerosol conditions. In order to make our analysis consistent and to be able to compare results from different sites, we performed an analysis of the data from SMEAR Estonia to compare the diffuse fractions of PAR and broadband radiation. The data set includes 4 years, from 2014 to 2017.

The measurements at SMEAR Estonia are made using an energy sensor. The hyperspectral radiometer SkySpec (Kuusk and Kuusk, 2018) is a purpose-built instrument for the automated measurement of global and diffuse sky irradiance. To obtain PAR radiation, the spectral data are converted from energy units to quantum units and are integrated over a 400–700 nm spectral range. Integration over the whole available spectral range in energy units is used for simulating a thermopile pyranometer.

2.4 The condensation sink as a measure of aerosol loading

As previously mentioned in Sect. 1, this study can be considered as a part of the project quantifying the COBACC feedback loop using ground-based measurements. The condensation sink (CS) is a typical parameter calculated from a ground-based aerosol number-size distribution and characterizing aerosol loading. It can be related to measured organic vapours, making it possible to study the effect of the formation and growth of secondary aerosol for photosynthesis. In addition, the CS was chosen in the original study of the COBACC feedback loop by Kulmala et al. (2014); therefore, for the sake of comparison we resort to this parameter.

The CS is calculated from the particle number-size distribution as follows: (Kulmala et al., 2001):

where Dv is the diffusion coefficient of the condensing vapour, n(dp) is the particle number-size distribution, and β is the Fuchs–Sutugin coefficient. The physical meaning of the CS is the inverse time needed for vapours to be taken up by existing aerosol particles. Similar to the scattering coefficient and the AOD, the value of the CS depends on aerosol surface area. However, the contribution of large particles to the CS diminishes with increasing particles diameter, in contrast to the aerosol surface area. This effect becomes pronounced for particles with a diameter larger than about 300 nm. For boreal forests, where the mode with a geometric mean diameter of around 100 nm dominates the particle number-size distribution, the CS can be assumed to be directly proportional to the aerosol surface area (Ezhova et al., 2018). Thus, one can assume that the CS is an appropriate measure of atmospheric aerosols for the radiation studies in boreal forests. The connection between this parameter and AOD500 for boreal forests is discussed in more detail in Appendix A.

2.5 The LUE and PAR analysis to assess the effect of diffuse radiation on GPP

There is a strong evidence that GPP dependence on Rd∕Rg is non-linear and has a maximum (Alton, 2008; Moffat et al., 2010; Park et al., 2018); however, this maximum is not always well pronounced. In what follows we explain the GPP maximum based on the ecosystem LUE and PAR dependences on Rd∕Rg. Following Cheng et al. (2016), we defined the LUE as the GPP per unit PAR, therefore . Strictly speaking, the LUE is defined as the GPP per unit absorbed PAR, i.e. , where fAPAR is the fraction of the absorbed PAR. The fraction of the absorbed PAR depends on the leaf area index (LAI), the solar zenith angle and other factors. This dependence for boreal forests was studied in Maijasalmi (2015) and Hovi et al. (2016). Based on results reported by Hovi et al. (2016), fAPAR for tree heights larger than 10 m and at a moderate zenith angle (40–60∘) can be estimated to be between 0.8 and 0.9. One can obtain the LUE defined by the absorbed PAR by dividing the LUE used in the present study by 0.8–0.9.

For all ecosystems with a sufficiently deep canopy and a high leaf area index, the LUE is expected to increase with Rd∕Rg, as a larger fraction of available photons can penetrate inside the canopy and can be used for photosynthesis. Some studies (Niyogi et al., 2004) have reported a linearly growing dependence of the LUE on Rd∕Rg. Furthermore, a decrease of PAR with Rd∕Rg can be expected, as an increase in the diffuse fraction of global irradiance corresponds to the enhancement of the scattering and reflecting properties of the atmosphere due to the presence of aerosols or clouds. Therefore, for each site the dependence of the LUE and PAR on Rd∕Rg was investigated separately, after which the GPP dependence on Rd∕Rg was derived from these two dependences.

Again, in order to have consistent data sets, we recalculated Rd∕Rg obtained from the PAR measurements so that it existed in terms of broadband radiation at all the sites. Conversely, broadband global radiation from Fonovaya and part of the SMEAR II data set was recalculated to PAR when investigating the LUE and PAR dependence on Rd∕Rg. We multiplied the global radiation by χglob=2.06 µmol s−1 W−1 in order to get PAR in quantum units. The PAR quantum efficiency was chosen to be equal to the one at SMEAR II, as for the daytime and similar solar zenith angles it is mostly aerosol dependent; SMEAR II and Fonovaya generally have similar aerosol loading values which can be confirmed by their similar CS values (Fig. 5). Considering the LUE, we filter out the data with low global irradiance, Rg⩽100 W m−2 (PAR ⩽ 200 µmol s−1 m−2). Below this critical Rg, the LUE shows significant scatter (it is high for the low radiation values); therefore we excluded these data from analysis.

We present the results of our study in two subsections. In Sect. 3.1 we report the results related to the aerosol effect on solar radiation, and in Sect. 3.2 we report the results related to the effect of diffuse radiation for ecosystem photosynthesis. The link between these results and their relation to other studies are discussed in Sect. 3.3.

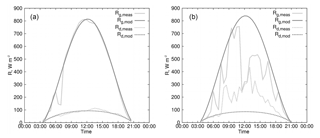

Figure 2Modelled vs. measured irradiance for SMEAR Estonia: measured global radiation, Rg,meas; modelled global radiation, Rg,mod; measured diffuse radiation, Rd,meas; and modelled diffuse radiation, Rd,mod. (a) 1 June 2016 – clear day; (b) 6 June 2016 – cloudy day. Timescale corresponds to local winter time (UTC+2).

3.1 Aerosol effect on solar radiation

3.1.1 Criterion of clear sky based on the Solis clear-sky model

To understand the importance of the clear-sky criterion for the diffuse fraction of global radiation, we report the model test against diffuse and global irradiance measurements at SMEAR Estonia ( the Solis clear-sky model is described in Sect. 2.2). Examples of the global and diffuse radiation diurnal cycles for clear and cloudy days are displayed in Fig. 2. Note that on a cloudy day with patchy clouds, the AOD can still be measured. Model results for a cloudy day report the global and diffuse clear-sky radiation for AOD and PW measured on that day. In general, the model performs well during clear-sky conditions as can be seen in Fig. 2a. This is in accordance with the results of Sengupta and Gotseff (2013) who reported good performance of the model for clear-sky conditions at several sites in the USA. On a cloudy day (Fig. 2b), there were times (e.g. at 09:00 and 17:00) when the measured and modelled global irradiance (Rg,meas and Rg,mod) were nearly equal while the measured diffuse irradiance (Rd,meas) was significantly higher than the modelled one (Rd,mod). The criterion of clear sky based on the comparison between the modelled and measured global irradiance, i.e. involving only global irradiance (Kulmala et al., 2014), does not filter out these points.

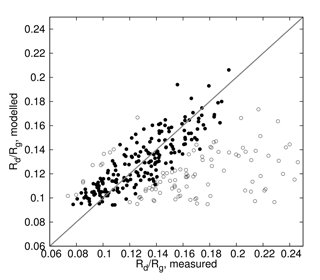

Figure 3The modelled vs. measured diffuse fraction of global irradiance (SMEAR Estonia, 2016). Closed symbols represent the criterion of clear sky based on diffuse and global irradiance (, ), the closed symbols and the open symbols combined represent the criterion of clear sky based on global irradiance (). The solid line illustrates the ideal 1:1 ratio between the modelled and measured data sets.

A further illustration of the simplified criterion and its consequences for the diffuse fraction of global irradiance is given in Fig. 3, displaying the diffuse fraction of global irradiance under clear-sky conditions at SMEAR Estonia (summer 2016). The open symbols in combination with the closed symbols correspond to the data obtained using the clear-sky criterion involving global radiation alone:

The closed symbols, in comparison, show the data obtained with the criterion involving both the diffuse and global radiation:

The criterion of clear sky suggested here is based on the results of Sengupta and Gotseff (2013), who determined a rms error of the linear regression corresponding to the measured global radiation and modelled global radiation using Solis for eight sites. This rms error did not exceed 10 % (cf. Equation 7 using global radiation), and was generally lower than that. As for diffuse radiation, we chose a 20 % difference between measured and modelled diffuse radiation in Equation (8). This difference was chosen based on the estimated 18 W m−2 error in diffuse radiation between the full Solis radiative transfer model and measurements, reported by Ineichen (2008), by assuming a typical diffuse radiation value of 120 W m−2, and by adding a 5 % error between the simplified model and the full Solis radiative transfer model. The closed symbols in Fig. 3 show a good agreement between the measured and modelled diffuse fractions of solar irradiance Rd∕Rg, while a considerable portion of the open symbols has large measured Rd∕Rg – meaning that they contain a large fraction of cloud-influenced data. Therefore, the criterion of clear sky based on the global and diffuse radiation can be used to detect clear-sky data when it is important to separate the effect of aerosol and clouds on diffuse radiation.

Note that the diffuse fraction of solar irradiance due to aerosol loading at SMEAR Estonia lies between 0.08 and 0.21. As shown later, this relatively low ratio pertains to all the sites in this study: the maximum diffuse fraction of solar irradiance due to the direct aerosol effect was no more than 0.27 at the remote sites in boreal forests during the growing season.

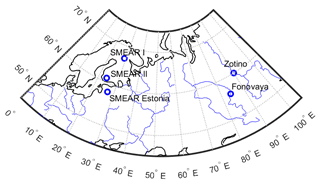

3.1.2 Parameterization of the diffuse fraction of PAR as a function of the diffuse fraction of broadband radiation

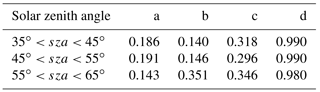

In this section we discuss the difference between the diffuse fractions of PAR and broadband radiation. Figure 4 displays the ratio between the diffuse fraction of PAR, fdifPAR, and the diffuse fraction of broadband radiation,fdifbb, as a function of fdifbb where . Since the radiation level depends on the solar zenith angle, we cast the daytime data into three solar zenith angle bins; the width of each bin was 10∘. Each data set was fitted by the exponential function

The coefficients of the fitting function for each bin are reported in Table 2. Using this function, we can compare the diffuse fractions of PAR and broadband radiation over the whole range of sky conditions, including clear and cloudy skies. As expected (see more in Sect. 2.3), in Fig. 4 we observe an increase in the diffuse fraction of PAR up to 27 % compared with the value for broadband radiation at small fdifbb, corresponding to clear-sky conditions. In absolute values, this difference between the diffuse fraction of the PAR and broadband radiation is not very large (e.g. fdifbb=0.15 corresponds to fdifPAR=0.18 under clear-sky conditions). However, as the diffuse fraction of global radiation in boreal forests varies in a relatively small range due to the direct effect of aerosol (e.g. Fig. 3), it is important to make corrections. As can be further noted from Fig. 4, the ratio fdifPAR∕fdifbb approaches one for overcast cloudy conditions, as in this case diffuse radiation prevails for both PAR and broadband radiation.

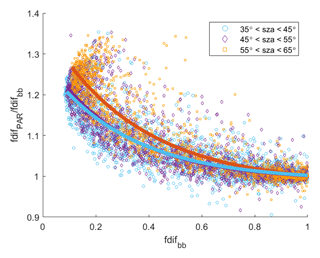

Table 2Best fit parameters for the diffuse fractions ratio, , as a function of the diffuse fraction of broadband radiation, fdifbb, for various solar zenith angles (Eq. 7).

We use these results to obtain the diffuse fraction of global broadband radiation for the sites where only PAR was measured. In the following we use the term “diffuse fraction of global radiation” for broadband radiation.

3.1.3 Aerosol influence on the diffuse fraction of global irradiance: comparative analysis for four sites

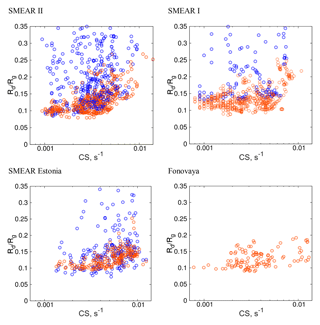

In this section, we consider the effect of aerosol on the diffuse fraction of global irradiance. In the following analysis the data were filtered to include only clear-sky conditions, based on the modelled and measured global irradiance, using Equation (7) for all of the sites. We deliberately used the equation based only on the global irradiance in order to demonstrate the effect of unfiltered cloud-contaminated data on the diffuse fraction of solar radiation. Figure 5 displays Rd∕Rg vs. CS at SMEAR I and II, SMEAR Estonia and Fonovaya (no aerosol data are available from Zotino). To separate the effect of clouds and aerosol particles, we report two quantities: the measured diffuse fraction of global irradiance (Fig. 5, blue symbols) and the modelled diffuse fraction of global irradiance (Fig. 5, orange symbols). Based on the analysis in Sect. 3.1.1, modelling provides information about the direct effect of aerosols on the diffuse fraction, while measurements illustrate the combined effects due to aerosols and clouds. Note that for consistency all the ratios Rd∕Rg were corrected in accordance with the previous section, meaning that only the ratios corresponding to the broadband radiation are reported (although PAR is measured at SMEAR I and II). For SMEAR I, the model data set includes 4 years, while only 2 years of measured data are available. Diffuse radiation is not measured at Fonovaya station; hence, only model results are shown. Moreover, the data from 2016 were not used due to forest fires in Siberia. Smoke plumes have large influences on the aerosol size distribution as a result of which the clear-sky model fails to predict diffuse and global radiation.

An increase in Rd∕Rg with increasing CS is observed at all of the sites, as follows from the model results (also representative for the measurements with an appropriate clear-sky equation, as discussed in Sect. 3.1.1 and demonstrated in Fig. 3). Note that the modelled values of Rd∕Rg correspond to the lower points in the measured data sets. The blue points above the modelled data are characterized by a larger diffuse radiation than those obtained for current AODs using Solis; hence, they represent the effect of clouds. According to the model calculations, the maximum diffuse fraction of global radiation due to the direct effect of aerosols did not exceed 0.27, while the minimum fraction was about 0.1. Furthermore, the aerosol population with CS smaller than approximately 0.005 s−1 do not significantly contribute to light scattering (Fig. 5), as the diffuse fraction of global irradiance for these values of CS is almost constant and close to 0.1; this can be generally attributed to Rayleigh scattering.

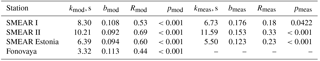

We fitted modelled and measured data with the linear function . The best-fit coefficients and correlation coefficients for four sites are reported in Table 3. All of the dependences pertaining to the modelled data, i.e. to the direct effect of aerosol particles on solar radiation, had correlation coefficients larger than 0.5 corresponding to a moderate correlation (except Fonovaya, where R=0.44, which was most likely due to the small data set). On the contrary, cloud-influenced data demonstrate rather weak correlations with .

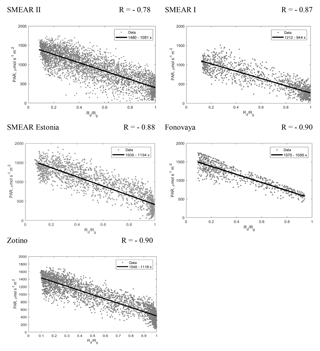

3.2 The effect of diffuse radiation on GPP

3.2.1 The effect of diffuse radiation on GPP: comparative analysis for all of the sites

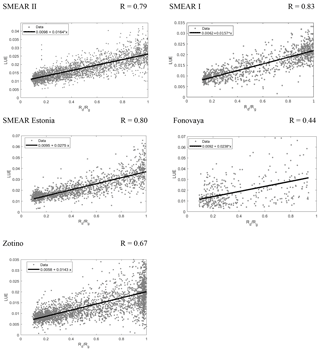

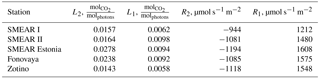

In this section we study the LUE and PAR dependences on the diffuse fraction of global radiation in order to better understand the behaviour of the dependence of GPP on Rd∕Rg. Figure 6 displays the dependences of the LUE on Rd∕Rg for all sites. All of these dependences exhibit a linear relationship with the correlation coefficients between R=0.67 and R=0.83 (except Fonovaya with R=0.44, which can be attributed to both the short data set and the less precise gradient method used for the CO2 flux calculations). The LUE slope reflects the canopy properties, i.e. it characterizes the ability of a forest stand to take up more CO2 in response to an increasing diffuse fraction of solar irradiance. The steepest LUE slopes pertain to the mixed forests at SMEAR Estonia and Fonovaya, while the slopes are approximately 60 % less steep in coniferous forests (Table 4). This difference is presumably due to the forest type, as mixed forests have a larger potential for photosynthetic activity enhancement due to a larger leaf area index and a deeper canopy. We emphasize that the difference is seen in the LUE, in accordance with the LUE definition given in Sect. 2.5, which includes a dependence on LAI and tree height attributed to fAPAR in the standard definition. Note that the increase in the LUE from approximately 0.01 to 0.03–0.04 mol CO2 mol photons−1 observed for mixed forests is similar to that reported by Cheng et al. (2016) for mixed and broadleaf forests in the USA.

Figure 7 displays the dependences of the global PAR on Rd∕Rg for all sites. As expected, PAR decreases as Rd∕Rg increases: at smaller values due to aerosol particles, and at larger values due to clouds. As follows from Fig. 5, the values of mostly correspond to the influence of aerosol particles (but they can also be influenced by thin clouds), while larger values of Rd∕Rg are associated with the presence of clouds. Similarly to the LUE, these dependences are linear with high correlation coefficients (). Generally, the slopes of the linear dependences in Fig. 7 were similar (within the range of 1081–1194 µmol s−1 m−2), which can probably be attributed to similar cloud attenuating properties over all of the sites at middle latitudes. The exception is SMEAR I, where the slope is lower (944 µmol s−1 m−2). Solar radiation under clear-sky conditions is also significantly lower at SMEAR I compared with the other sites, which is partly due to the high latitude, and partly because the growing season at SMEAR I is July and August (i.e. it does not include June which has the highest global irradiance values).

Figure 7Photosynthetically active global radiation (PAR) as a function of the diffuse fraction of global irradiance (Rd∕Rg). All dependences are statistically significant (p<0.001). The number of sample points is reported in the caption of Fig. 6.

The vertical scattering of the data in Fig. 7 is presumably due to two factors: first, the variability in the radiation intensity during daytime and growing season, and second, the different influences of clouds, as the same diffuse fraction of global irradiance may pertain to the different attenuations of global radiation by clouds. Note that the latter factor is excluded from the Fonovaya data set by the parameterization. One can conclude that the PAR variability due to clouds was larger than the diurnal (associated with different solar zenith angles during the day) and day-to-day PAR variability in the growing season. Thus, additional binning by, e.g. solar zenith angle, would be redundant, as the decrease in PAR variability due to binning would be hidden by the stronger scattering due to clouds.

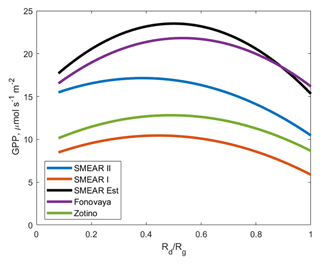

Finally, based on the linear dependences of the LUE on Rd∕Rg and PAR on Rd∕Rg, we can estimate how GPP depends on Rd∕Rg. When we multiplied the LUE by PAR, parabolic dependences were obtained for all the sites, with a maximum due to the effect of diffuse radiation on photosynthesis. Figure 8 shows the estimated GPP dependences on Rd∕Rg for the different sites for comparison, while Fig. 9 displays data sets and estimated curves separately for all sites, similar to Figs. 6 and 7.

Figure 8Estimated GPP dependences on Rd∕Rg for all of the sites (obtained as using the coefficients for PAR and the LUE dependences on Rd∕Rg reported in Table 4).

Figure 9GPP dependences on Rd∕Rg for all of the sites. The curves represent estimated GPP (the same parabolas as in Fig. 8). We use a dashed curve for Fonovaya due to the relatively low correlation coefficient obtained for the LUE (R=0.44, Fig. 6). The data sets for all of sites were cast in bins in Rd∕Rg, the width of each bin is ( for Fonovaya). Black points correspond to the mean GPP in each bin and error bars show the standard deviation of the data for each bin.

3.2.2 Constraints on the LUE and the diffuse fraction of solar radiation associated with the maximum ecosystem GPP under diffuse light

Well-pronounced linear dependences of the LUE and PAR on Rd∕Rg can be used to estimate how large an increase in the LUE should be in order to have GPP increase under diffuse radiation and at what diffuse fraction of solar radiation the maximum GPP can be observed. If

then the maximum GPP is reached at , estimated as the point where the parabola has its maximum. The position of this maximum depends on the ratios L2∕L1 and R2∕R1. For a certain range of parameters, the maximum of the parabola can be located at , which is below the minimum diffuse fraction measured at our sites; therefore, it is not feasible for the latitudes we consider in this study. In this case, GPP monotonically decreases when Rd∕Rg increases from ∼0.1 to 1. Conversely, (Rd∕Rg)max should be larger than 0.08–0.1 for the GPP to have a maximum under diffuse light. Note, that PAR dependences on Rd∕Rg at middle latitudes are similar: , while for SMEAR I this ratio is . From these estimates, for the middle latitudes. Since L1 is roughly the minimum value of the LUE at (clear sky), while L1+L2 is the maximum of the LUE at (overcast conditions), L2 can be treated as the maximal gain in the LUE under diffuse light. Thus, the GPP will have a maximum associated with diffuse radiation if the ecosystem LUE under diffuse light increases by more than approximately 80 % of its minimum possible value (which is observed under clean conditions on clear days). For the sites considered in the present study, the smallest gain in the LUE due to diffuse radiation is observed at SMEAR II, where the LUE under diffuse light was almost twice as large as its value on clear days. The largest gain was at SMEAR Estonia and Fonovaya where the LUE grew by almost a factor of 3 if the dominating radiation conditions in the area changed from mostly direct to mostly diffuse radiation. Therefore, all ecosystems displayed maxima of GPP dependence on Rd∕Rg due to diffuse light, although at different values of Rd∕Rg.

Moreover, this approach clearly demonstrates that the maximum GPP can never be reached under overcast conditions. If we again take as for the middle latitudes, then the position of the maximum is at . One can immediately deduce that for large slopes of the LUE, i.e. when L1∕L2 approaches zero, (Rd∕Rg)max approaches 0.7. At SMEAR I, this position is restricted by (Rd∕Rg)max ≈ 0.65. The maximum of GPP parabolas for the five sites considered in this study is at –0.5.

3.3 Discussion

In this section we combine the results from the previous sections to make conclusions regarding the direct effect of aerosols on GPP, and we compare the results obtained with those from previous studies.

As previously mentioned in Sect. 3.1.3, a cloud-biased data set and a standard linear regression analysis results in weak but significant (p<0.001) correlations between CS and Rd∕Rg (Table 3). The relatively high cloud-biased diffuse fraction of global radiation at low CS leads to an underestimation of the effect of increasing aerosol loading for the cloud-biased data set. If CS increases from 0.002 to 0.015 s−1 (obtained for the clear-sky conditions), a relative increase in the diffuse fraction of global radiation following from the clear-sky model is from 110 % to 165 % at all of the sites except Fonovaya, while this increase is between 65 % and 118 % for cloud-biased data. In the following we use only the results for the clear-sky model (representing the measured data set when the stricter Equation (8) of clear sky is applied, as follows from Fig. 3). In absolute values the increase was quite small: from 0.11 to ∼0.27 at SMEAR I and II, and from 0.11 to ∼0.2 at SMEAR Estonia and Fonovaya. The increases in Rd∕Rg over these value ranges led to increases in GPP from 17.2 to 18.6 µmol s−1 m−2 at Fonovaya, from 18.5 to 20.9 µmol s−1 m−2 at SMEAR Estonia, from 15.8 to 16.9 µmol s−1 m−2 at SMEAR II and from 8.8 to 10.0 µmol s−1 m−2 at SMEAR I. The largest relative increases in GPP due to the increasing aerosol loading from its minimum value to its maximum value were observed for SMEAR I and SMEAR Estonia (14 % and 13 % respectively). Note, however, that the median value of CS should be increased by a factor of about 5 at SMEAR I to get this maximum gain in GPP, whereas this same increase in GPP would be observed at SMEAR Estonia if the median CS increased by a factor of 2–3.

Overall, we obtained rather weak dependence of the diffuse fraction on CS. It is much weaker than that reported by Kulmala et al. (2014): for all of the sites the slope is less than 10 s (Table 3) compared with the almost 100 s obtained in the above-mentioned study. This difference is due to the inappropriate equation of clear sky selecting cloud-biased points with a diffuse fraction up to 0.8 (Kulmala et al., 2014) and a different statistical method (bivariate fitting compared with the linear regression used in this study). Note that Kulmala et al. (2014) reported minimum and maximum possible slopes for an increase in the diffuse fraction of global radiation with CS. Our present results are close to their minimum slope. Furthermore, due to the large diffuse fractions attributed to the effect of aerosols rather than clouds, the maximum direct effect of aerosols on GPP was overestimated by Kulmala et al. (2014). In the present study we obtained a 6 % increase in GPP at SMEAR II due to the diffuse radiation effect rather than the ≈30 % reported by Kulmala et al. (2014). However, their minimum slope, reported for GPP vs. Rd∕Rg dependence, would result in an increase of GPP similar to this study.

Note that the aerosol loading observed at all sites corresponds to 0.04 < AOD675<0.35 with the typical values being in the range of 0.05–0.10 and AOD500<0.25 (see Appendix A). In accordance with the study by Park et al. (2018), an increase in the diffuse fraction did not exceed 0.3 for these relatively low AOD values. Much higher diffuse fractions (0.5–0.7) due to the direct aerosol effect were obtained by Cirino et al. (2014) for the biomass burning season in the Amazon.

Next, all of the GPP dependences have a maximum due to clouds. The maximum corresponds to the clouds with a diffuse fraction in the order of 0.4–0.5. According to Cheng et al. (2016) and Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia et al. (2017), this Rd∕Rg corresponds to optically thin clouds with cloud optical thicknesses less than 5. Conversely, GPP decreases for optically thick clouds, which has also been demonstrated by Cheng et al. (2016). The largest increase is 32 %–33 % at SMEAR Estonia and Fonovaya, whereas the smallest increase is 11 % at SMEAR II compared with the GPP values on clear days characterized by low aerosol loading. At middle latitudes with a similar attenuation of radiation due to aerosols and clouds, the increase in GPP depends on the LUE slope: the steeper the LUE slope is, the more pronounced the maximum.

Based on Fig. 8, similar forest stands at Zotino and SMEAR I demonstrated a similar dependence of the GPP on Rd∕Rg, while this dependence was different for the coniferous forest at SMEAR II. GPP at SMEAR II under clear sky is almost 1.5 times larger than the corresponding GPP at SMEAR I and Zotino, but GPP increase under cloudy sky is smaller at SMEAR II. This could be a consequence of the closed canopy and the higher leaf area index of the SMEAR II forest stand. Our GPP data sets, reported in Fig. 9, look similar to those reported by Alton et al. (2007) and Alton (2008). The GPP dependence reported for SMEAR II is also similar to that reported by Alton (2008) for needle-leaf forests, but for mixed forests we obtained an increase of up to 30 % compared with the moderate 10 % increase for broadleaf forests reported by Alton (2008). Note that Alton (2008) used parameterization, Eq. (1), for the diffuse fraction of global radiation, while we had measurements of diffuse radiation at four sites out of five.

Finally, we considered the data from Zotino including the periods of forest fires (Park et al., 2018). Figure 7 suggests that forest fires do not have any specific influence on the PAR decrease with increasing Rd∕Rg compared with cloudy sky. In other words, plumes from forest fires lead to a similar decrease in PAR and a similar separation in diffuse and direct fractions as some clouds. The same holds for the LUE of an ecosystem: the dependence of the LUE on Rd∕Rg at Zotino is similar to that of other coniferous sites. However, a significant increase in GPP under wildfire plumes can potentially be obtained at a daily timescale because the radiation regime with (Rd∕Rg)max, i.e. close to the optimal conditions for ecosystem photosynthesis, can persist for a long time under plume conditions. At the same time, clouds may be intermittent and the effect of a sporadic GPP increase can be compensated for by the smaller GPP when clouds are in front of the sun and radiation is reduced (Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia et al., 2017).

We quantified the direct effect of aerosol on solar radiation and GPP in boreal and hemiboreal forests in Eurasia. The analysis was based on data from five sites including coniferous and mixed forest ecosystems. The diffuse fraction of global radiation due to the direct aerosol effect was estimated to be in the range of at all of the sites.

For the first time we demonstrated a connection between solar radiation properties (the diffuse fraction of global radiation) and condensation sink. The latter parameter is used in aerosol studies and it is obtained from ground-based observations. Employing CS instead of a column-averaged aerosol parameter AOD is a necessary step towards further investigation of the COBACC climate feedback loop, linking biogenic volatile organic compounds emissions and aerosol characteristics.

The GPP-radiation analysis was performed using the separation of GPP into the LUE and PAR. We found a linear dependence between the diffuse fraction of solar radiation and the LUE, as well as between the diffuse fraction of solar radiation and PAR, for all of the sites. While the PAR dependences were quite similar to one another (except for SMEAR I which is located at a relatively high latitude), the LUE dependences were different: the slopes were 60 % steeper for mixed forests than for coniferous forests, and the intercepts were about 40 % lower for coniferous forests with open canopies. We obtained a parabolic shape for the GPP dependence on the diffuse fraction of solar radiation. The maximum of the parabola was more pronounced for mixed forests due to the above-mentioned differences in the LUE dependences between the mixed and coniferous forests. Note that parabolic, or near parabolic, shapes have been reported for different forest sites by Alton (2008) and Moffat et al. (2010) using different methods to those used in this study.

We showed that GPP can be increased by 6 %–14 % due to the direct effect of aerosol particles at remote sites compared to clean conditions with low values of CS. The maximum increase was observed for mixed forests at mid-latitudes and for coniferous forests at relatively high latitudes.

Furthermore, based on the similarity in the PAR dependences on the diffuse fraction of solar radiation for all of the sites, we obtained the constraints on the ecosystems' LUE increase under diffuse light necessary for a GPP maximum due to diffuse light. At mid-latitudes, the LUE of an ecosystem should increase by more than ∼80 % under diffuse light compared with its value under clear-sky conditions. Moreover, at the mid-latitude sites, the diffuse fraction of solar radiation corresponding to the maximum GPP can not exceed 0.7.

The specific shape of the GPP dependence on the diffuse fraction of solar radiation suggests that clouds with a 30 min-averaged fraction Rd∕Rg between 0.4 and 0.5 play an important role in determining ecosystems' GPP and demand further investigation. An increase in GPP due to clouds can reach 32 %–33 % for mixed forests and 21 %–26 % for coniferous forests with an open canopy. Other relevant questions include cloud effects on the radiation regime and ecosystems' GPP on annual scale and the investigation of potential aerosol effects on the evolution of clouds over forests.

Data measured at the SMEAR II and SMEAR I stations are available from an open research data portal AVAA: http://avaa.tdata.fi/web/smart/ (Keronen et al., 2018). The data sets from other stations can be made available from the authors upon request.

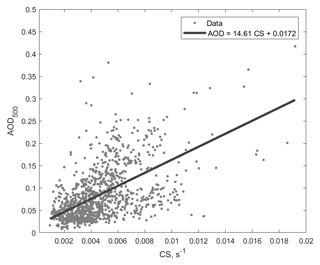

To make our study comparable to studies that use AOD500 as a parameter quantifying aerosol loading, we performed an additional analysis for the data sets from SMEAR II and SMEAR Estonia. We used 30 min-averaged AOD from AERONET sites and CS, corresponding to the period from 09:00 to 15:00 (local time) and maximal growing season. The data set from SMEAR II encompasses 3 years (2008–2010) and the data set from SMEAR Estonia encompasses 4 years (2013–2016).

The results are shown in Fig. A1. Though AOD500 clearly increases with increasing CS, the scatter of data is great. It means that in spite of the fact that both parameters are roughly proportional to the aerosol surface area distribution (Sundström et al., 2015), and in spite of the presumably well-mixed boundary layer during daytime, there is no simple relationship between ground-based and column-integrated aerosol characteristics. This has also been noted by Sundström et al. (2015) for sites in South Africa. Sundström et al. (2015) found a moderate correlation between the in situ measured scattering coefficient and AOD from AERONET. At the same time, the scattering coefficient was strongly correlated with CS; therefore, a moderate correlation between CS and AOD from AERONET could be expected. Figure A1 shows a moderate correlation (R=0.53) for boreal forests at the mid-latitudes.

EE, JB, TV, MH and MK developed the concept of the study and interpreted the results. EE analysed most of the data sets and wrote the paper. IY calculated CS and performed the CS-radiation data analysis for SMEAR I. JK analysed the hyperspectral radiation data from the Tartu observatory and contributed to writing Sects. 2.3 and 3.1.2. KK and MV prepared the aerosol data sets and calculated CS for SMEAR Estonia. AK and SN calculated GPP for SMEAR Estonia and contributed to writing Sect. 2. MA and BB performed the quality control of the data set from Fonovaya and contributed to writing Sect. 2. PK and IM calculated GPP for SMEAR I and II and commented on the comparison of GPP from different stations. SBP and JVL performed quality control of the data set from Zotino and contributed to writing Sect. 2. UR helped with the gradient method to calculate CO2 flux for Fonovaya and to improve the graphic representation of results. VMK and TP helped with the interpretation of results. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This study is a part of the Pan-Eurasian Experiment (PEEX) program (Lappalainen et al., 2016). All of the Eurasia sites mentioned in this study are partners of the PEEX program and perform continuous multidisciplinary measurements pertaining to boreal forests.

This article is part of the special issue “Pan-Eurasian Experiment (PEEX)”. It is not associated with a conference.

The authors are grateful to two referees who helped to improve clarity of

the paper. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland Center of

Excellence programme (grant no. 307331) and the Academy of Finland professor

grant to Markku Kulmala (grant no. 302958). The results are part of a project (ATM-GTP/ERC)

that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the

European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant

agreement no. 742206) and NordForsk via TRAKT-2018: Transferable Knowledge

and Technologies for High-Resolution Environmental Impact Assessment and

Management. Steffen Noe and Alisa Krasnova acknowledge support from the

European network for observing our changing planet project (ERA-PLANET, grant

agreement no. 689443) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and

innovation programme and the Estonian Ministry of Sciences project “Biosphere–atmosphere interaction and climate research applying the SMEAR

Estonia research infrastructure” (grant no. P170026PKTF). Measurements at

Fonovaya station are performed with support from the Russian Science Foundation

(grant no. 17-17-01095). Aerosol measurements at SMEAR Estonia were supported

by the institutional research funding IUT20-11 and IUT20-52 of the Estonian

Ministry of Education and Research.

Edited

by: Dominick Spracklen

Reviewed by: Jordi Vila and one

anonymous referee

Alton, P.: Reduced carbon sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems under overcast skies compared to clear skies, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 148, 1641–1653, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2008.05.014, 2008. a, b, c, d, e

Alton, P., Mercado, L., and North, P.: A sensitivity analysis of the land-surface scheme JULES conducted for three forest biomes: Biophysical parameters, model processes, and meteorological driving data, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 20, GB1008, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002653, 2007. a

Cheng, S. J., Bohrer, G., Steiner, A. L., Hollinger, D. Y., Suyker, A., Phillips, R. P., and Nadelhoffer, K. J.: Variations in the influence of diffuse light on gross primary productivity in temperate ecosystems, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 201, 98–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2014.11.002, 2015. a, b

Cheng, S. J., Steiner, A. L., Hollinger, D. Y., Bohrer, G., and Nadelhoffer, K. J.: Using satellite-derived optical thickness to assess the influence of clouds on terrestrial carbon uptake, J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeo., 121, 1747–1761, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JG003365, 2016. a, b, c, d

Cirino, G. G., Souza, R. A. F., Adams, D. K., and Artaxo, P.: The effect of atmospheric aerosol particles and clouds on net ecosystem exchange in the Amazon, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 6523–6543, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-6523-2014, 2014. a

Dal Maso, M., Hyvärinen, A., Komppula, M., Tunved, P., Kerminen, V.-M., Lihavainen, H., Viisanen, Y., Hansson, H.-C., and Kulmala, M.: Annual and interannual variation in boreal forest aerosol particle number and volume concentration and their connection to particle formation, Tellus, 60, 495–508, 2008. a

Duchon, C. E. and O'Malley, M. S.: Estimating Cloud Type from Pyranometer Observations, J. Appl. Meteorol., 38, 132–141, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1999)038<0132:ECTFPO>2.0.CO;2, 1999. a

Ezhova, E., Kerminen, V.-M., Lehtinen, K. E. J., and Kulmala, M.: A simple model for the time evolution of the condensation sink in the atmosphere for intermediate Knudsen numbers, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 2431–2442, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-2431-2018, 2018. a

Gu, L., Baldocchi, D., Verma, S. B., Black, T. A., Vesala, T., Falge, E. M., and Dowty, P. R.: Advantages of diffuse radiation for terrestrial ecosystem productivity, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 107, 2–23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD001242, 2002. a, b

Hari, P. and Kulmala, M.: Station for measuring ecosystem-atmosphere relations (SMEAR II), Boreal. Env. Res., 10, 315–322, 2005. a

Hari, P., Kulmala, M., Pohja, T., Lahti, T., Siivola, E., Palva, L., Aalto, P., Hämeri, K., Vesälä, T., Luoma, S., and Pulliainen, E.: Air pollution in eastern Lapland: challenge for an environmental research station, Sylva Fenn., 28, 29–39, 1994. a

Heimann, M., Schulze, E.-D., Winderlich, J., Andreae, M., Chi, X., Gerbig, C., Kolle, O., Kübler, K., Lavric, J., Mikhailov, E., Panov, A., Park, S., Rödenbeck, C., and Skorochod, A.: The Zotino Tall Tower Observatory (ZOTTO): Quantifying large scale biogeochemical changes in central Siberia, Nova Acta Leopold., 117, 51–64, 2014. a

Holben, B., Eck, T., Slutsker, I., Tanré, D., Buis, J., Setzer, A., Vermote, E., Reagan, J., Kaufman, Y., Nakajima, T., Lavenu, F., Jankowiak, I., and Smirnov, A.: AERONET – A Federated Instrument Network and Data Archive for Aerosol Characterization, Remote Sens. Environ., 66, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(98)00031-5, 1998. a

Hovi, A., Liang, J., Korhonen, L., Kobayashi, H., and Rautiainen, M.: Quantifying the missing link between forest albedo and productivity in the boreal zone, Biogeosciences, 13, 6015–6030, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-6015-2016, 2016. a, b

Ineichen, P.: A broadband simplified version of the Solis clear sky model, Sol. Energy, 82, 758–762, 2008. a, b, c, d, e

Kanniah, K. D., Beringer, J., North, P., and Hutley, L.: Control of atmospheric particles on diffuse radiation and terrestrial plant productivity: A review, Prog. Phys. Geogr.-Earth Environ., 36, 209–237, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133311434244, 2012. a

Keronen, P., Kolari, P., Mammarella, I., and Aalto, P.: Data measured at the SMEAR II and SMEAR I stations, http://avaa.tdata.fi/web/smart/, last access: 30 June 2018.

Kolari, P., Kulmala, L., Pumpanen, J., Launiainen, S., Ilvesniemi, H., Hari, P., and Nikinmaa, E.: CO2 exchange and component CO2 fluxes of a boreal Scots pine forest, Boreal Env. Res., 14, 761–783, 2009. a, b

Kulmala, M., Dal Maso, M., Mäkelä, J. M., Pirjola, L., Väkevä, M., Aalto, P., Miikkulainen, P., Hämeri, K., and O'Dowd, C. D.: On the formation, growth and composition of nucleation mode particles, Tellus B, 53, 479–490, 2001. a

Kulmala, M., Nieminen, T., Nikandrova, A., Lehtipalo, K., Manninen, H. E., Kajos, M. K., Kolari, P., Lauri, A., Petäjä, T., Krejci, R., Hansson, H.-C., Swietlicki, E., Lindroth, A., Christensen, T. R., Arneth, A., Hari, P., Bäck, J., Vesala, T., and Kerminen, V.-M.: CO2-induced terrestrial climate feedback mechanism: From carbon sink to aerosol source and back, Boreal Env. Res., 19, 122–131, 2014. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j

Kuusk, J. and Kuusk, A.: Hyperspectral radiometer for automated measurement of global and diffuse sky irradiance, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 204, 272–280, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2017.09.028, 2018. a

Lappalainen, H. K., Kerminen, V.-M., Petäjä, T., Kurten, T., Baklanov, A., Shvidenko, A., Bäck, J., Vihma, T., Alekseychik, P., Andreae, M. O., Arnold, S. R., Arshinov, M., Asmi, E., Belan, B., Bobylev, L., Chalov, S., Cheng, Y., Chubarova, N., de Leeuw, G., Ding, A., Dobrolyubov, S., Dubtsov, S., Dyukarev, E., Elansky, N., Eleftheriadis, K., Esau, I., Filatov, N., Flint, M., Fu, C., Glezer, O., Gliko, A., Heimann, M., Holtslag, A. A. M., Hõrrak, U., Janhunen, J., Juhola, S., Järvi, L., Järvinen, H., Kanukhina, A., Konstantinov, P., Kotlyakov, V., Kieloaho, A.-J., Komarov, A. S., Kujansuu, J., Kukkonen, I., Duplissy, E.-M., Laaksonen, A., Laurila, T., Lihavainen, H., Lisitzin, A., Mahura, A., Makshtas, A., Mareev, E., Mazon, S., Matishov, D., Melnikov, V., Mikhailov, E., Moisseev, D., Nigmatulin, R., Noe, S. M., Ojala, A., Pihlatie, M., Popovicheva, O., Pumpanen, J., Regerand, T., Repina, I., Shcherbinin, A., Shevchenko, V., Sipilä, M., Skorokhod, A., Spracklen, D. V., Su, H., Subetto, D. A., Sun, J., Terzhevik, A. Y., Timofeyev, Y., Troitskaya, Y., Tynkkynen, V.-P., Kharuk, V. I., Zaytseva, N., Zhang, J., Viisanen, Y., Vesala, T., Hari, P., Hansson, H. C., Matvienko, G. G., Kasimov, N. S., Guo, H., Bondur, V., Zilitinkevich, S., and Kulmala, M.: Pan-Eurasian Experiment (PEEX): towards a holistic understanding of the feedbacks and interactions in the land–atmosphere–ocean–society continuum in the northern Eurasian region, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 14421–14461, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-14421-2016, 2016. a

Lasslop, G., Migliavacca, M., Bohrer, G., Reichstein, M., Bahn, M., Ibrom, A., Jacobs, C., Kolari, P., Papale, D., Vesala, T., Wohlfahrt, G., and Cescatti, A.: On the choice of the driving temperature for eddy-covariance carbon dioxide flux partitioning, Biogeosciences, 9, 5243–5259, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-5243-2012, 2012. a, b

Lu, X., Chen, M., Liu, Y., Miralles, D. G., and Wang, F.: Enhanced water use efficiency in global terrestrial ecosystems under increasing aerosol loadings, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 237/238, 39–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.02.002, 2017. a, b

Maijasalmi, T.: Estimation of leaf area index and the fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation in a boreal forest, Dissertationes Forestales, Helsingin Yliopisto, 2015. a

Matvienko, G. G., Belan, B. D., Panchenko, M. V., Romanovskii, O. A., Sakerin, S. M., Kabanov, D. M., Turchinovich, S. A., Turchinovich, Y. S., Eremina, T. A., Kozlov, V. S., Terpugova, S. A., Pol'kin, V. V., Yausheva, E. P., Chernov, D. G., Zhuravleva, T. B., Bedareva, T. V., Odintsov, S. L., Burlakov, V. D., Nevzorov, A. V., Arshinov, M. Y., Ivlev, G. A., Savkin, D. E., Fofonov, A. V., Gladkikh, V. A., Kamardin, A. P., Balin, Y. S., Kokhanenko, G. P., Penner, I. E., Samoilova, S. V., Antokhin, P. N., Arshinova, V. G., Davydov, D. K., Kozlov, A. V., Pestunov, D. A., Rasskazchikova, T. M., Simonenkov, D. V., Sklyadneva, T. K., Tolmachev, G. N., Belan, S. B., Shmargunov, V. P., Kozlov, A. S., and Malyshkin, S. B.: Complex experiment on studying the microphysical, chemical, and optical properties of aerosol particles and estimating the contribution of atmospheric aerosol-to-earth radiation budget, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 4507–4520, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-4507-2015, 2015. a

Mercado, L., Bellouin, N., Sitch, S., Boucher, O., Huntingford, C., Wild, M., and Cox, P.: Impact of changes in diffuse radiation on the global land carbon sink, Nature, 458, 1015–1018, 2009. a

Moffat, A. M., Beckstein, C., Churkina, G., Mund, M., and Heimann, M.: Characterization of ecosystem responses to climatic controls using artificial neural networks, Glob. Change Biol., 16, 2737–2749, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02171.x, 2010. a, b

Mueller, R., Dagestad, K., Ineichen, P., Schroedter-Homscheidt, M., Cros, S., Dumortier, D., Kuhlemann, R., Olseth, J., Piernavieja, G., Reise, C., Wald, L., and Heinemann, D.: Rethinking satellite-based solar irradiance modelling: The SOLIS clear-sky module, Remote Sens. Environ., 91, 160–174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2004.02.009, 2004. a, b

Niyogi, D., Chang, H., Saxena, V. K., Holt, T., Alapaty, K., Booker, F., Chen, F., Davis, K. J., Holben, B., Matsui, T., Meyers, T., Oechel, W. C., Pielke, R. A., Wells, R., Wilson, K., and Xue, Y.: Direct observations of the effects of aerosol loading on net ecosystem CO2 exchanges over different landscapes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L20506, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GL020915, 2004. a, b, c, d

Noe, S., Niinemets, Ü., Krasnova, A., Krasnov, D., Motallebi, A., Kängsepp, V., Jõgiste, K., Hõrrak, U., Komsaare, K., Mirme, S., Vana, M., Tammet, H., Bäck, J., Vesala, T., Kulmala, M., Petäjä, T., and Kangur, A.: SMEAR Estonia: Perspectives of a large-scale forest ecosystem – atmosphere research infrastructure, Forest. Stud., 63, 56–84, 2015. a

Pachauri, R. K., Allen, M. R., Barros, V. R., Broome, J., Cramer, W., Christ, R., Church, J. A., Clarke, L., Dahe, Q., Dasgupta, P., Dubash, N. K., Edenhofer, O., Elgizouli, I., Field, C. B., Forster, P., Friedlingstein, P., Fuglestvedt, J., Gomez-Echeverri, L., Hallegatte, S., Hegerl, G., Howden, M., Jiang, K., Cisneroz, B. J., Kattsov, V., Lee, H., Mach, K. J., Marotzke, J., Mastrandrea, M. D., Meyer, L., Minx, J., Mulugetta, Y., O'Brien, K., Oppenheimer, M., Pereira, J. J., Pichs-Madruga, R., Plattner, G.-K., Pörtner, H.-O., Power, S. B., Preston, B., Ravindranath, N. H., Reisinger, A., Riahi, K., Rusticucci, M., Scholes, R., Seyboth, K., Sokona, Y., Stavins, R., Stocker, T. F., Tschakert, P., van Vuuren, D., and van Ypserle, J.-P.: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. a

Park, S.-B., Knohl, A., Lucas-Moffat, A. M., Migliavacca, M., Gerbig, C., Vesala, T., Peltola, O., Mammarella, I., Kolle, O., Lavrič, J. V., Prokushkin, A., and Heimann, M.: Strong radiative effect induced by clouds and smoke on forest net ecosystem productivity in central Siberia, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 250/251, 376–387, 2018. a, b, c, d, e, f

Pecenak, Z. K., Mejia, F. A., Kurtz, B., Evan, A., and Kleissl, J.: Simulating irradiance enhancement dependence on cloud optical depth and solar zenith angle, Sol. Energy, 136, 675–681, 2016. a

Pedruzo-Bagazgoitia, X., Ouwersloot, H. G., Sikma, M., van Heerwaarden, C. C., Jacobs, C. M. J., and Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J.: Direct and Diffuse Radiation in the Shallow Cumulus–Vegetation System: Enhanced and Decreased Evapotranspiration Regimes, J. Hydrometeorol., 18, 1731–1748, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-16-0279.1, 2017. a, b

Reichstein, M., Falge, E., Baldocchi, D., Papale, D., Aubinet, M., Berbigier, P., Bernhofer, C., Buchmann, N., Gilmanov, T., Granier, A., Grünwald, T., Havránková, K., Ilvesniemi, H., Janous, D., Knohl, A., Laurila, T., Lohila, A., Loustau, D., Matteucci, G., Meyers, T., Miglietta, F., Ourcival, J., Pumpanen, J., Rambal, S., Rotenberg, E., Sanz, M., Tenhunen, J., Seufert, G., Vaccari, F., Vesala, T., Yakir, D., and Valentini, R.: On the separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and ecosystem respiration: review and improved algorithm, Glob. Change Biol., 11, 1424–1439, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001002.x, 2005. a

Ross, J. and Sulev, M.: Sources of errors in measurements of PAR, Agr. Forest Meteorol., 100, 103–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(99)00144-6, 2000. a, b

Seinfeld, J. H. and Pandis, S. N.: Atmospheric chemistry and physics: from air pollution to climate change, Wiley, New Jersey, USA, 2016. a

Sengupta, M. and Gotseff, P.: Evaluation of Clear Sky Models for Satellite-Based Irradiance Estimates, Tech. Rep. NREL/TP-5D00-60735, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2013. a, b, c

Sundström, A.-M., Nikandrova, A., Atlaskina, K., Nieminen, T., Vakkari, V., Laakso, L., Beukes, J. P., Arola, A., van Zyl, P. G., Josipovic, M., Venter, A. D., Jaars, K., Pienaar, J. J., Piketh, S., Wiedensohler, A., Chiloane, E. K., de Leeuw, G., and Kulmala, M.: Characterization of satellite-based proxies for estimating nucleation mode particles over South Africa, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 4983–4996, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-4983-2015, 2015. a, b, c