the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Underestimation of anthropogenic organosulfates in atmospheric aerosols in urban regions

Yanting Qiu

Junrui Wang

Tao Qiu

Jiajie Li

Yanxin Bai

Teng Liu

Ruiqi Man

Taomou Zong

Wenxu Fang

Jiawei Yang

Yu Xie

Zeyu Feng

Chenhui Li

Ying Wei

Kai Bi

Dapeng Liang

Ziqi Gao

Zhijun Wu

Yuchen Wang

Organosulfates (OSs) are important components of organic aerosols, which serve as critical tracers of secondary organic aerosols (SOA). However, molecular composition, the relationship between OSs and their precursors, and formation driving factors of OSs at different atmospheric conditions have not been fully constrained. In this work, we integrated OS molecular composition, precursor-constrained positive matrix factorization (PMF) source apportionment, and OS-precursor correlation analysis to classify OS detected from PM2.5 samples according to their volatile organic compounds (VOCs) precursors collected from three different cities (Beijing, Taiyuan, and Changsha) in China. This new approach enables the accurate classification of OSs from molecular perspective. Compared with conventional classification methods, we found the mass fraction of Aliphatic OSs (including nitrooxy OSs; NOSs) increased by 22.0 %, 17.8 %, and 10.3 % in Beijing, Taiyuan, and Changsha, respectively, highlighting the underestimation of Aliphatic OSs in urban regions. The formation driving factors of Aliphatic OSs during the field campaign were further investigated. We found that elevated aerosol liquid water content promoted the formation of Aliphatic OSs only when aerosols transition from non-liquid state to liquid state. In addition, enhanced inorganic sulfate mass concentrations, and Ox (Ox= NO2+ O3) concentrations, as well as decreased aerosol pH commonly facilitated the formation of Aliphatic OSs. These results reveal a significant underestimation of OSs derived from anthropogenic emissions in wintertime, particularly Aliphatic OSs, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of SOA formation and composition in urban environments.

- Article

(3278 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1605 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Due to the diversity of natural and anthropogenic emissions and the complexity of atmospheric chemistry, investigating the chemical characterization and formation mechanisms of secondary organic aerosols (SOA) remains challenging. Among SOA components, organosulfates (OSs) have emerged as key tracers (Brüggemann et al., 2020; Hoyle et al., 2011), as their formation is primarily governed by secondary atmospheric processes. Moreover, OS significantly influences the aerosol physicochemical properties, including acidity (Riva et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019), hygroscopicity (Estillore et al., 2016; Ohno et al., 2022; Hansen et al., 2015), and light-absorption properties (Fleming et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2025). Therefore, a deeper understanding of OS abundance, sources, and formation drivers is crucial for elucidating SOA formation and its properties.

Quantifying OS abundance is critical to assess their contribution to SOA. However, this is difficult due to the large number and structural diversity of OSs molecules and the lack of authentic standards. Most studies quantify a few representative OSs using synthetic or surrogate standards (Wang et al., 2020, 2017; Huang et al., 2018b; He et al., 2022), while non-target analysis (NTA) with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) offers broader molecular characterization (Huang et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022b; Cai et al., 2020). Although NTA combined with surrogate standards allows molecular-level (semi-)quantification, overall OS mass concentration remains underestimated, and many OSs remain unidentified (Lukács et al., 2009; Cao et al., 2017; Tolocka and Turpin, 2012; Ma et al., 2025).

Classifying OS based on their precursors is a powerful approach for understanding OS formation from a mechanistic perspective. OSs from specific precursors generally share similar elemental compositions, with characteristic ranges of C atoms, double bond equivalents (DBE), and aromaticity equivalents (Xc). For example, isoprene-derived OSs typically contain 4–5 C atoms; monoterpene- and sesquiterpene-derived OSs usually have 9–10 and 14–15 C atoms, respectively (Lin et al., 2012; Riva et al., 2016c, 2015; Wang et al., 2019a; Surratt et al., 2008). An “OS precursor map”, correlating molecular weight and carbon number based on chamber studies, has been developed to classify OSs accordingly (Wang et al., 2019a). However, these approaches often oversimplify OS formation by relying solely on elemental composition, leaving many OSs without identified precursors.

The formation mechanisms of OS remain incompletely understood, though several driving factors have been identified through controlled chamber experiments and ambient observations. For instance, increased aerosol liquid water content (ALWC) enhances OS formation by promoting the uptake of gaseous precursors (Xu et al., 2021a; Wang et al., 2021b). Inorganic sulfate can also affect OS formation by acting as nucleophiles via epoxide pathway (Eddingsaas et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2020). However, meteorological conditions vary across cities, meaning the relative importance of these factors may differ by location. Thus, evaluating these formation drivers under diverse atmospheric conditions is essential. Identifying both common and region-specific drivers is key to a comprehensive understanding of OS formation mechanisms.

In this study, we employed NTA using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to characterize OS molecular composition in PM2.5 samples from three cities. Identified OSs were classified by their VOCs precursors, including aromatic, aliphatic, monoterpene, and sesquiterpene VOCs, via precursor-constrained positive matrix factorization (PMF). Mass concentrations were quantified or semi-quantified using authentic or surrogate standards. Additionally, spatial variations in OS mass concentrations and environmental conditions were analyzed to distinguish both common and site-specific drivers of OS formation.

2.1 Sampling and Filter Extraction

Field observations were conducted during winter (December 2023 to January 2024) at three urban sites in China: Beijing, Taiyuan, and Changsha. The site selection was based on contrasts in winter meteorological conditions and dominate PM2.5 sources. For meteorological conditions, Beijing and Taiyuan represent northern Chinese cities with cold, dry conditions (low RH). In comparison, Changsha is characterized by relatively higher winter RH. In terms of PM2.5 sources, Taiyuan is a traditional industrial and coal-mining base, Changsha's pollution profile is more influenced by traffic and domestic cooking emissions, whereas Beijing is characterized by a high mass fraction of secondary aerosols. This enables a comparative analysis of OS formation mechanisms under varied atmospheric conditions. In Beijing, PM2.5 samples were collected at the Peking University Atmosphere Environment Monitoring Station (PKUERS; 40.00° N, 116.32° E), as detailed in previous studies (Wang et al., 2023a). Sampling in Taiyuan and Changsha took place on rooftops at the Taoyuan National Control Station for Ambient Air Quality (37.88° N, 112.55° E) and the Hunan Hybrid Rice Research Center (28.20° N, 113.09° E), respectively (see Fig. S1 in the Supplement).

Daily PM2.5 samples were collected on quartz fiber filters (φ=47 mm, Whatman Inc.) from 09:00 to 08:00 local time the next day. All quartz fiber filters were pre-baked at 550° for 9 h before sampling to remove the background organic matters. In Beijing and Taiyuan, RH-resolved sampling was performed using a home-made RH-resolved sampler, stratifying daily samples into low (RH ≤ 40 %), moderate (40 %> RH ≤ 60 %), and high (RH >60 %) RH regimes with the sampling flow rate of 38 L min−1. Due to persistently high RH in Changsha, a four-channel sampler (TH-16, Wuhan Tianhong Inc.) collected PM2.5 samples without RH stratification with the flow rate of 16.7 L min−1. Consequently, Beijing and Taiyuan collected one or more samples daily, whereas Changsha collected one sample per day. A total of 40, 64, and 30 samples were obtained from Beijing, Taiyuan, and Changsha, respectively. The samples were stored in a freezer at −18 °C immediately after collection. The maximum duration between the completion of sampling and the start of chemical analysis was approximately 40 d. Prior to analysis, all samples were equilibrated for 24 h under controlled temperature (20±1 °C) and RH (40 %–45 %) within a clean bench, in order to allow the filters to reach a stable, reproducible condition for subsequent handling and to minimize moisture condensation. Average daily PM2.5 mass concentrations and RH during sampling are summarized in Table S1.

Sample extraction followed established protocols (Wang et al., 2020). Briefly, filters were ultrasonically extracted twice for 20 min. A total volume of 10 mL of LC-MS grade methanol (Merck Inc.) was used for each sample. All extracts were filtered through 0.22 µm PTFE syringe filters, and evaporated under a gentle stream of high-purity N2 (>99.99 %). The dried extracts were then redissolved in 2 mL of LC-MS grade methanol for analysis. This step was necessary to achieve sufficient sensitivity for the detection of OSs with low concentration.

During the campaign, gaseous pollutants (SO2, NO2, O3, CO) were monitored using automatic analyzers. PM2.5 and PM10 mass concentrations were measured by tapered element oscillating microbalance (TEOM). Water-soluble ions (Na+, NH, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Cl−, NO, SO) were analyzed with the Monitor for AeRosols and Gases in ambient Air (MARGA) coupled with ion chromatography. Organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) were quantified by online OC/EC analyzers or carbon aerosol speciation systems. Trace elements in PM2.5 were determined by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF). Additionally, VOCs concentrations were measured using an online gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system with a one-hour time resolution in Taiyuan and Changsha. Table S2 summarizes the monitoring instruments deployed at each site. All instruments were calibrated to ensure the reliability of the measurement data. Specifically, the online gas pollutants and particulate matter automatic analyzers underwent automatic zero/span checks every 24 h at 00:00 local time. For MARGA-ion chromatography, OC/EC analyzers, and XRF systems were calibrated weekly. The online GC-MS system was automatically calibrated every 24 h using standard VOCs mixture.

2.2 Identification of Organosulfates

The molecular composition of PM2.5 extracts was analyzed using an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system (Thermo Ultimate 3000, Thermo Scientific) coupled with an Orbitrap HRMS (Orbitrap Fusion, Thermo Scientific) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in negative mode. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a reversed-phase Accucore C18 column (150×2.1 mm, 2.6 µm particle size, Thermo Scientific). For tandem MS acquisition, full MS scans ( 70–700) were collected at a resolving power of 120 000, followed by data-dependent MS/MS (ddMS2) scans ( 50–500) at 30 000 resolving power. Detailed UHPLC-HRMS2 parameters are provided in Sect. S1 in the Supplement.

NTA was performed using Compound Discoverer (CD) software (version 3.3, Thermo Scientific) to identify chromatographic peak features (workflow details in Table S3). Molecular formulas were assigned based on elemental combinations CcHhOoNnSs (c=1–90, h=1–200, o=0–20, n=0–1, s=0–1) within a mass tolerance of 0.005 Da with up to one 13C isotope. Formulas with hydrogen-to-carbon (H C) ratios outside 0.3–3.0 and oxygen-to-carbon (O C) ratios beyond 0–3.0 were excluded to remove implausible assignments. We calculated the double bond equivalent (DBE) and aromatic index represented by Xc based on assigned elemental combinations using Eqs. (1) and (2), where m and k were the fractions of oxygen and sulfur atoms in the π-bond structures of a compound (both m and k were presumed to be 0.50 in this work (Yassine et al., 2014)).

In Eq. (2), Xc is an important indicator of whether aromatic rings exist in a molecule. Studies have proved that a molecule is considered aromatic if its Xc value exceeds 2.50 (Ma et al., 2022; Yassine et al., 2014). OSs were selected based on compounds with O/S ≥4 and HSO ( 96.96010) fragments were observed in their corresponding MS2 spectra. Among them, if N number is 1, O/S ≥7, and their MS2 spectra showed ONO ( 61.98837) fragment, these OSs were defined as nitrooxy OSs (NOSs). It should be noted that several CHOS (composed of C, H, O, and S atoms, hereinafter) and CHONS species were not determined as OSs due to their low-abundance and insufficient to trigger reliable data-dependent MS2 acquisition, which may lead to an underestimation of total OS mass concentration.

2.3 Classification and Quantification/Semi-quantification of Organosulfates

To ensure the reliability of quantitative analysis and source attribution, this study focuses on OS species with C ≥8. The exclusion of smaller OSs (C ≤7) is based on challenges in their unambiguous identification, including co-elution with interfering compounds (Liu et al., 2024), and higher uncertainty in precursor assignment due to the lack of characteristic “tracer” molecules in laboratory experiments. Though re-dissolve using pure methanol may not be the ideal solvent for retaining polar, early-eluting compounds on the reversed-phase column, it provided a consistent solvent for the analysis of the mid- and non-polar OS species (C ≥8) that are the focus of this study.

To classify the identified OSs, we employed and compared two distinct classification approaches. Firstly, a conventional classification approach relies primarily on precursor–product relationships established through controlled laboratory chamber experiments and field campaigns (Zhao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021a, 2022b; Deng et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021b; Mutzel et al., 2015; Brüggemann et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2024; Duporté et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2023; Riva et al., 2016a). Based on these established precursor–product relationships, detected OSs and NOSs were classified into four groups: Monoterpene OSs (including Monoterpene NOSs, hereinafter), Aliphatic OSs (including Aliphatic NOSs, hereinafter), Aromatic OSs (including Aromatic NOSs, hereinafter), and Sesquiterpene OSs (including Sesquiterpene NOSs, hereinafter) (see Table S4 for details). It is apparent that this approach has notable limitations when applied to detected OS in atmospheric aerosols. A substantial fraction of detected OSs does not match known laboratory tracers and are thus labeled Unknown OSs (including Unknown NOSs, hereinafter).

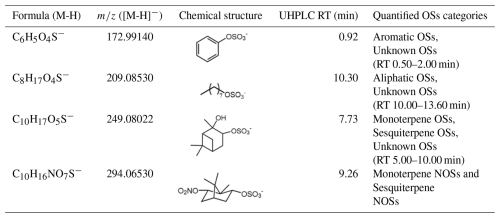

Synthetic α-pinene OSs (C10H17O5S−) and NOSs (C10H16NO7S−) served for (semi-)quantifying Monoterpene and Sesquiterpene OSs. Their detailed synthesis procedure was described in previous study (Wang et al., 2019b). Potassium phenyl sulfate (C6H5O4S−) and sodium octyl sulfate (C8H17O4S−) were used for Aromatic OSs and Aliphatic OSs due to lack of authentic standards (Yang et al., 2023; He et al., 2022; Staudt et al., 2014). Unknown OSs were semi-quantified by surrogates with similar retention times (RT) (Yang et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023). Table 1 lists the standards, retention times, and quantified categories. Unknown OSs are absent between 2.00–5.00 min and after 13.60 min.

Table 1Chemical structure, UHPLC retention time, and quantified categories of standards used in the quantification/semi-quantificaiton of OSs and NOSs.

This quantification approach introduces inherent uncertainty, as differences in molecular structure and functional groups between a surrogate and detected OSs have different ionization efficiency (Ma et al., 2025), which is a well-documented challenge in NTA of complex mixtures. However, this approach provides a consistent basis for comparing the relative abundance of OS in different cities and their formation driving factors. Hence, the mass concentration of detected OSs is still reliable in understanding their classification and formation driving factors.

To classify the Unknown OSs, we first calculated the Xc of each specie. Those with DBE >2 and Xc >2.50 were designated as Aromatic OSs (Yassine et al., 2014). Subsequently, constrained positive matrix factorization (PMF) analysis was performed using EPA PMF 5.0. The input matrix comprised the mass concentrations of 60 unclassified OS species across all samples.

Figure S2 shows the source profiles of PMF model. Four factors were identified in this study. Specifically, Factor 1 is identified as Aliphatic OSs due to the dominant contributions from species like C11H22O5S and C12H24O5S, which possess low DBE and are characteristic of long-chain alkane oxidation (Yang et al., 2024). This assignment is strongly supported by the co-variation of this factor with n-dodecane. Similarly, Factor 2 is classified as Aromatic OSs, highlighted by the significant contribution of C10H10O7S and C11H14O7S, which have been proved as OSs derived from typical aromatic VOCs (Riva et al., 2015). In addition, the high contributions of benzene, toluene, and styrene in Factor 2 further suggests that this factor should be classified as Aromatic OSs. As for Factor 3 and Factor 4 is confirmed by the prominence of established Monoterpene OSs (Surratt et al., 2008; Iinuma et al., 2007) (e.g., C10H18O5S, C10H17NO7S) and Sesquiterpene OSs (Wang et al., 2022b) (e.g., C14H28O6S, C15H25NO7S), respectively. Moreover, isoprene showed high contribution in both Factors 3 and 4. As monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes cannot be detected by online GC-MS, considering that monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes mainly originate from biogenic sources and strongly correlate with isoprene (Guenther et al., 2006; Sakulyanontvittaya et al., 2008), therefore, isoprene is used as a surrogate marker as Monoterpene OSs and Sesquiterpene OSs. High contribution of isoprene in Factors 3 and 4 proved that these factors were respectively determined as Monoterpene OSs and Sesquiterpene OSs. Based on marker species, Unknown OSs were further categorized into Monoterpene, Aromatic, Aliphatic, and Sesquiterpene OSs.

The model was executed with 10 runs to ensure stability. The ratio of for this solution was stabilized below 1.50, indicating a robust fit without over-factorization. Furthermore, the scaled residual matrix (see Fig. S3), demonstrating that residuals are randomly distributed and predominantly within the acceptable range of −3 to 3. Correlation coefficients between classified OSs and corresponding VOCs (Monoterpene OSs vs. isoprene; Aromatic OSs vs. benzene; Aliphatic OSs vs. n-dodecane; Sesquiterpene OSs vs. isoprene) were calculated as a statistical auxiliary variable to verify the reliability of PMF results. The arithmetic mean of hourly VOCs within each corresponding filter sampling period was calculated to align the time resolution of VOCs and OS mass concentration. Species with R<0.40 were excluded to avoid potential incorrect classification.

To validate classification accuracy, MS2 fragment patterns were analyzed (Table S5). Diagnostic fragments supported the assignments: Aliphatic OSs showed sequential alkyl chain cleavages () and saturated alkyl fragments ([CnH2n+1]− or [CnH2n−1]−); Monoterpene OSs displayed [CnH2n−3]− fragments; Aromatic OSs exhibited characteristic aromatic substituent fragments ([C6H5R-H]−, R= alkyl, carbonyl, -OH, or H). While absolute certainty for every individual OS in a complex ambient mixture is unattainable, integrating the precursor-constrained PMF model, tracer VOCs correlation analysis, and MS2 fragment patterns validation significantly reduces the likelihood of systematic misclassification.

3.1 Concentrations, Compositions, and Classification of Organosulfates

Figure 1 shows the temporal variations of OS and organic aerosols (OA) mass concentrations, as well as RH, during the sampling period across the three cities. The total mass concentration of OS reported in this study is the sum of the (semi-)quantified concentrations of all individual OS species that met the identification criteria described in Sect. 2.3. The mean OSs concentrations were (41.1±34.5) ng m−3 in Beijing, (57.4±39.2) ng m−3 in Taiyuan, and (102.1±80.5) ng m−3 in Changsha. Table S6 summarizes the average concentrations of PM2.5, OC, gaseous pollutants, OS mass concentrations, and the mean meteorological parameters during sampling period for all three cities. OS accounted for 0.64 %±0.44 %, 0.41 %±0.24 %, and 0.76 %±0.34 % of the total OA in Beijing, Taiyuan, and Changsha, respectively.

The highest OS mass concentrations and OS OA ratios were observed in Changsha. As shown in Fig. 1a, a distinct episode with OS mass concentrations exceeding 300 ng m−3 occurred between 27 and 31 December, leading to the elevated OS mass concentrations in Changsha. This episode coincided with a period of intense fireworks activity, as evidenced by significant increases in the concentrations of recognized fireworks tracers, especially Ba and K (see Fig. S4), leading to an increase in SO2 emission. We noted that though K may originate from biomass burning, its trend in concentration shows good consistency with that of Ba. Therefore, we still infer that fireworks activity are also the primary source of K. Considering persistently high RH (consistently >70 %) during this period, as displayed in Fig. S5, ALWC (117.9 µg m−3 in average) therefore increased and facilitated the heterogeneous oxidation of SO2 to particulate sulfate (Wang et al., 2016; Ye et al., 2023). Since particulate sulfate serves as a key reactant in OS formation pathways, its elevated concentration directly promoted OS production (Xu et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2020). Furthermore, fireworks activity led to concurrent increases in the concentrations of transition metals, notably Fe and Mn (Fig. S4), which are known to catalyze aqueous-phase radical chemistry and OS formation (Huang et al., 2019, 2018a). Therefore, the pronounced OS mass concentration during this period is attributed to a combination of elevated precursor emissions (SO2), high-RH conditions favoring aqueous-phase processing, and the potential catalytic role of co-emitted transition metals.

It is noteworthy that the single highest OS OA ratio in Beijing was observed on 31 December under low RH. This phenomena highlights that ALWC, while a major driving factor of OS formation, is not an exclusive control. Specifically, this day showed high atmospheric oxidative capacity and aerosol acidity. We note that under such conditions, efficient acid-catalyzed heterogeneous reactions of gas-phase oxidation products could drive substantial OS formation. The impact of ALWC, atmospheric oxidative capacity, and aerosol pH on OS formation will be discussed in detail in Sect. 3.2.

Figure 2a and b shows the average mass concentrations and fractions of different OSs categories across the three cities, based on classification approach based on OSs' elemental composition and laboratory chamber-derived precursor–OS relationships and our precursor-based PMF classification approach developed in this work, respectively (see Sect. 2.3 for details). As displayed in Fig. 2b, Monoterpene OSs dominated detected OSs across all cities, contributing 55.2 % (Beijing), 46.8 % (Taiyuan), and 72.3 % (Changsha) to total OS, respectively. Biogenic-emitted monoterpene is the precursor of Monoterpene OSs. However, monoterpenes are primarily biogenic precursors, their limited emissions during winter cannot fully explain the high mass fractions of Monoterpene OSs. Recent studies have highlighted anthropogenic sources, particularly biomass burning, as significant contributors to monoterpene (Wang et al., 2022a; Koss et al., 2018). The PM2.5 source apportionment analysis (Sect. S2, Fig. S6) confirmed that biomass burning substantially contributed to PM2.5 across all cities. The highest total mass fractions of Monoterpene OSs in Changsha are mainly attributed to the high RH (Table S6), which facilitates their formation via heterogeneous reactions (Hettiyadura et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Ding et al., 2016a, b; Li et al., 2020).

Figure 2The average mass concentrations of different OSs categories using (a) conventional classification approach based on OSs' elemental composition and laboratory chamber-derived precursor–OS relationships and (b) precursor-based PMF classification approach developed in this work across all cities. The inserted pie chart indicates the average mass fractions of different OSs categories.

In Taiyuan, the total mass fractions of Aromatic OSs (21.2 %) were significantly higher than those in Beijing (10.7 %) and Changsha (4.6 %). Aromatic OSs primarily formed via aqueous-phase reactions between S(IV) and aromatic VOCs (Huang et al., 2020). Taiyuan exhibited the highest sulfate mass concentration among the three cities (Table S6), which promoted the formation of these species. Additionally, transition metal ions – particularly Fe3+ – catalyze aqueous-phase formation of Aromatic OSs (Huang et al., 2020). High Fe mass concentration was observed in Taiyuan (0.79±0.53 µg m−3), further facilitated the formation of Aromatic OSs.

The highest total mass fractions of Aliphatic OSs were observed in Beijing (28.1 %). Since vehicle emissions, which is an important source of long-chain alkenes (He et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021a; Riva et al., 2016b; Tao et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2020), substantially contributed to PM2.5 in all cities (Fig. S6), the relative dominance of Aliphatic OSs in Beijing can be attributed to a comparative reduction in the emissions of precursors for Monoterpene OSs and Aromatic OSs. Specifically, Beijing exhibits lower emissions of monoterpene and aromatic VOCs precursors relative to Taiyuan and Changsha, which results in a reduced contribution of Monoterpene and Aromatic OSs to the total OS (see Fig. 2b). Therefore, the relative mass fraction of Aliphatic OSs, which primarily derived from between sulfate and photooxidation products of alkenes (Riva et al., 2016b), becomes more prominent in Beijing. Additionally, low RH in Beijing further suppresses the aqueous-phase formation of Monoterpene OSs, amplifying the relative importance of Aliphatic OSs.

Figure 3(a) The measured particle rebound fraction (f) and total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs as a function of RH, the plots were colored by the calculated ALWC concentrations in Taiyuan, grey dots indicate the mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs; (b) the relationship between aerosol pH and ALWC across three cities, the markers were colored by the inorganic sulfate mass concentrations, the marker sizes represented the total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs; (c) the box plot of total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs at different Ox concentration levels.

3.2 Formation Driving Factors of Aliphatic OSs and NOSs

Compared with conventional classification approach (Fig. 2a), we found Aliphatic OSs increased markedly (by 22.0 %, 17.8 %, and 10.3 % in Beijing, Taiyuan, and Changsha, respectively). Therefore, we further examined the formation drivers of Aliphatic OSs.

ALWC plays a key role in facilitate OS formation (Wang et al., 2020). Using PM2.5 chemical composition and RH, ALWC was calculated via the ISORROPIA-II model (details in Sect. S3) (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007). Given the direct influence of ambient RH on ALWC (Fig. S7) (Bateman et al., 2014) and leveraging RH-resolved samples from Beijing and Taiyuan, we assessed RH effects on Aliphatic OSs under low (RH <40 %), medium (40 %≤ RH <60 %), and high (RH ≥60 %) conditions.

In Changsha, where RH remains consistently high, Aliphatic OSs mass concentrations strongly correlated with RH (R=0.78). In Beijing and Taiyuan, correlations increased from low to medium RH (Beijing: 0.53 to 0.82; Taiyuan: 0.38 to 0.77) but declined slightly at higher RH (Beijing: 0.82 to 0.69; Taiyuan: 0.77 to 0.72). The initial correlation rise reflects ALWC-enhanced sulfate-driven heterogeneous OS formation (Wang et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2016), while the decline at elevated RH may due to the increase in ALWC dilutes the concentrations of precursors and intermediates of Aliphatic OSs within the aqueous phase. Therefore, Aliphatic OSs formation were not further promoted, exhibiting the non-linear response of their mass concentrations and ALWC.

This threshold behavior aligns with aerosol phase transitions. Particle rebound fraction (f), indicating phase state, was measured in Taiyuan using a three-arm impactor (Liu et al., 2017). As RH exceeded 60 %, f dropped below 0.2 (Fig. 3a), signaling a transition from non-liquid to liquid aerosol states. This transition at RH >60 % aligns with prior field (Liu et al., 2017, 2023; Meng et al., 2024; Song et al., 2022) and modeling (Qiu et al., 2023) studies in Eastern China. Correspondingly, Aliphatic OSs concentrations increased with RH below 60 % but plateaued beyond that despite further humidity rises. These findings underscore aerosol phase state as a critical factor: initial liquid phase formation (RH <60 %) promotes heterogeneous OS formation (Ye et al., 2018), whereas at higher RH, saturation of reactive interfaces limits further ALWC effects.

In addition, the increase in ALWC with rising RH altered aerosol pH (Fig. 3b), which inhibited OSs formation via acid-catalyzed reactions (Duporté et al., 2016). In Changsha, as aerosol pH increased from approximately 1.0 to above 3.0, the average total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs decreased significantly from 9.3 to 4.6 ng m−3 (Fig. S8), with further declines as pH increased. In Taiyuan, OS concentrations dropped from 12.2 to 6.8 ng m−3 as pH rose from below 4.5 to above 5.0. However, in Beijing, total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs remained stable within a narrow pH range of 3.2–3.9. Elevated ALWC facilitates aqueous-phase radical chemistry that forms OSs via non-acid pathways, which can dominate over pH-dependent processes (Rudziński et al., 2009; Wach et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2019). Thus, pH-dependent suppression of Aliphatic OSs formation is common across urban aerosol pH ranges, but less evident when pH varies narrowly.

Inorganic sulfate plays a crucial role in OS formation via sulfate esterification reactions (Xu et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2020). We thus examined its effect on the formation of Aliphatic OSs. Figure 3b illustrates the relationships among ALWC, pH, inorganic sulfate mass concentration, and total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs across all cities. A consistent positive correlation was observed, consistent with previous field studies (Lin et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023b, 2018; Le Breton et al., 2018). This correlation was strongest when sulfate concentrations were below 20 µg m−3. Below this threshold, total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs increased significantly with inorganic sulfate, whereas above it, the correlation weakened. Additionally, inorganic sulfate mass concentration showed a clear positive correlation with ALWC (Fig. 3b), suggesting that ionic strength did not increase linearly with sulfate mass. This likely reflects saturation effects in acid-mediated pathways, driven by limitations in water activity and ionic strength (Wang et al., 2020). Overall, these results highlight the nonlinear influence of inorganic sulfate on Aliphatic OSs formation.

Atmospheric oxidative capacity, represented by Ox (Ox= O3 + NO2) concentrations, typically modulates OS formation via acid-catalyzed ring-opening reactions pathways. As shown in Fig. 3c, total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs and NOSs exhibited significant increases with rising Ox levels across all cities. Especially, total mass concentrations of Aliphatic OSs significantly increased across all cities when Ox concentrations raised from 60–80 to >80 µg m−3. As shown in Fig. S9, O3 dominated the Ox composition during high-Ox episodes (>80 µg m−3) across all cities. Previous laboratory studies have suggested that enhanced atmospheric oxidation capacities promote the oxidation of VOCs (Zhang et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2024), forming cyclic intermediates. We therefore inferred that the increase in Ox facilitates the formation of cyclic intermediates derived from long-chain alkenes. Subsequent acid-catalyzed and ring-opening reactions are important pathways of heterogeneous OSs formation, including Aliphatic OSs (Eddingsaas et al., 2010; Iinuma et al., 2007; Brüggemann et al., 2020).

It should be noted that though formation driving factors of Aliphatic OSs identified in this work, including ALWC, inorganic sulfate, and Ox, are likely applicable in other urban environments sharing similar winter conditions characterized by high anthropogenic emissions and moderate-to-high humidity. However, their importance may differ in other cities with different atmospheric conditions, like in summer with strong biogenic emissions, in regions with low aerosol acidity, or in arid cities with persistently low RH.

In this study, we applied a NTA approach based on UHPLC-HRMS to investigate the molecular composition of OS in PM2.5 samples from three cities. By integrating molecular composition data, precursor-constrained PMF source apportionment, and OS–precursor correlation analysis, we developed a comprehensive method for accurate classification of detected OSs, demonstrating superior discrimination between Aliphatic OSs. Conventional classification methods rely on laboratory chamber-derived precursor–OS relationships (Wang et al., 2019a), which provide limited insight into the formation of Aliphatic OSs and tend to underestimate their mass fractions. The abundant Aliphatic OSs detected in ambient PM2.5 suggest complex formation pathways, such as OH oxidation of long-chain alkenes (Riva et al., 2016b) and heterogeneous reactions between SO2 and alkene in acidic conditions (Passananti et al., 2016), which remain incompletely understood in laboratory studies. Our findings highlight the importance of emphasizing the formation of Aliphatic OSs in urban atmospheres.

This study still faces several challenges. This work was conducted during the winter. OS formation exhibits seasonal variability, particularly for pathways driven by biogenic VOCs emissions and photochemical activity, which are generally enhanced in warmer months. Hence, the underestimation of Aliphatic OSs, and their key formation factors determined in this work remain valid insights for the winter period but may not fully represent annual OS behavior. In addition, our field campaigns were conducted in three typical different Chinese cities, the effect of these driving factors on the formation of Aliphatic OSs may not be applicable to other cities with different atmospheric conditions. Future long-term observations in more cities are necessary to resolve the complete annual cycle of OS composition, quantify the shifting contributions of anthropogenic versus biogenic precursors, and understand how key formation driving factors evolve with changing atmospheric conditions.

For NTA, the use of surrogate standards for the quantifications of OS mass concentration introduced uncertainty, particularly due to the extraction efficiency of individual OSs species from quartz fiber filters could not be determined. Although we have adopted standardized extraction protocol to ensure high comparability across our samples, absolute extraction recoveries may vary. In addition, this approach depends on public molecular composition such as mzCloud and ChemSpider integrated within the Compound Discoverer software, which contain limited entries for organosulfates. Reliance on these databases for compound identification may therefore underestimate OS mass concentrations in urban environments. For example, OSs identified here accounted for less than 1 % of total OA mass, whereas recent work (Ma et al., 2025) reported approximately 20 % contributions.

OS may become increasingly significant in OA, particularly in coastal regions influenced by oceanic dimethyl sulfate emissions (Brüggemann et al., 2020). Our future work will focus on synthesizing OSs standards representing various precursors and establishing a dedicated fragmentation database through multi-platform MS2 validation to elucidate OS sources in more detail.

The data used in this study is available upon request from the corresponding authors, Zhijun Wu (zhijunwu@pku.edu.cn) and Yuchen Wang (ywang@hnu.edu.cn).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-2411-2026-supplement.

Y.Q., J.W., and Z.W. designed this work. J.L., Y.Wei, C.L., J.Y., T.L., R.M., T.Z., W.F., J.Y., Z.F., Y.X. and K.B. collected PM2.5 samples. Y.Q., J.W., T.Q., Y.B., and D.L. conducted UHPLC-HRMS experiments. Y.Q., J.W., Z.G., and Y.Wang wrote this manuscript. Z.W., Y.Wang, and M.H. edited this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to submit this manuscript. Y.Q. and J.W. contributed equally to this work.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Y.W would like to acknowledge financial support by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grants 22221004 and 22306059), This work was also supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (Grants 2024RC3106 and 2025AQ2001), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant 531118010830).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22221004 and 22306059). This work was also supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (grant nos. 2024RC3106 and 2025AQ2001), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 531118010830).

This paper was edited by Jason Surratt and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Bateman, A. P., Belassein, H., and Martin, S. T.: Impactor Apparatus for the Study of Particle Rebound: Relative Humidity and Capillary Forces, Aerosol Science and Technology, 48, 42–52, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2013.853866, 2014.

Brüggemann, M., Xu, R., Tilgner, A., Kwong, K. C., Mutzel, A., Poon, H. Y., Otto, T., Schaefer, T., Poulain, L., Chan, M. N., and Herrmann, H.: Organosulfates in Ambient Aerosol: State of Knowledge and Future Research Directions on Formation, Abundance, Fate, and Importance, Environmental Science & Technology, 54, 3767–3782, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b06751, 2020.

Cai, D., Wang, X., Chen, J., and Li, X.: Molecular Characterization of Organosulfates in Highly Polluted Atmosphere Using Ultra-High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, e2019JD032253, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD032253, 2020.

Cao, G., Zhao, X., Hu, D., Zhu, R., and Ouyang, F.: Development and application of a quantification method for water soluble organosulfates in atmospheric aerosols, Environmental Pollution, 225, 316–322, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.086, 2017.

Cheng, Y., Zheng, G., Wei, C., Mu, Q., Zheng, B., Wang, Z., Gao, M., Zhang, Q., He, K., Carmichael, G., Pöschl, U., and Su, H.: Reactive nitrogen chemistry in aerosol water as a source of sulfate during haze events in China, 2, e1601530, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601530, 2016.

Deng, Y., Inomata, S., Sato, K., Ramasamy, S., Morino, Y., Enami, S., and Tanimoto, H.: Temperature and acidity dependence of secondary organic aerosol formation from α-pinene ozonolysis with a compact chamber system, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 5983–6003, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-5983-2021, 2021.

Ding, X., He, Q.-F., Shen, R.-Q., Yu, Q.-Q., Zhang, Y.-Q., Xin, J.-Y., Wen, T.-X., and Wang, X.-M.: Spatial and seasonal variations of isoprene secondary organic aerosol in China: Significant impact of biomass burning during winter, Scientific Reports, 6, 20411, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20411, 2016a.

Ding, X., Zhang, Y.-Q., He, Q.-F., Yu, Q.-Q., Shen, R.-Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Lyu, S.-J., Hu, Q.-H., Wang, Y.-S., Li, L.-F., Song, W., and Wang, X.-M.: Spatial and seasonal variations of secondary organic aerosol from terpenoids over China, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 121, 14661–14678, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025467, 2016b.

Duporté, G., Flaud, P. M., Geneste, E., Augagneur, S., Pangui, E., Lamkaddam, H., Gratien, A., Doussin, J. F., Budzinski, H., Villenave, E., and Perraudin, E.: Experimental Study of the Formation of Organosulfates from α-Pinene Oxidation. Part I: Product Identification, Formation Mechanisms and Effect of Relative Humidity, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 120, 7909–7923, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.6b08504, 2016.

Duporté, G., Flaud, P. M., Kammer, J., Geneste, E., Augagneur, S., Pangui, E., Lamkaddam, H., Gratien, A., Doussin, J. F., Budzinski, H., Villenave, E., and Perraudin, E.: Experimental Study of the Formation of Organosulfates from α-Pinene Oxidation. 2. Time Evolution and Effect of Particle Acidity, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 124, 409–421, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.9b07156, 2020.

Eddingsaas, N. C., VanderVelde, D. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Kinetics and Products of the Acid-Catalyzed Ring-Opening of Atmospherically Relevant Butyl Epoxy Alcohols, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 114, 8106–8113, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp103907c, 2010.

Estillore, A. D., Hettiyadura, A. P. S., Qin, Z., Leckrone, E., Wombacher, B., Humphry, T., Stone, E. A., and Grassian, V. H.: Water Uptake and Hygroscopic Growth of Organosulfate Aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 4259–4268, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05014, 2016.

Fleming, L. T., Ali, N. N., Blair, S. L., Roveretto, M., George, C., and Nizkorodov, S. A.: Formation of Light-Absorbing Organosulfates during Evaporation of Secondary Organic Material Extracts in the Presence of Sulfuric Acid, ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 3, 947–957, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.9b00036, 2019.

Fountoukis, C. and Nenes, A.: ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+–Ca2+–Mg2+–NH–Na+–SO–NO–Cl−–H2O aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 4639–4659, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007, 2007.

Guenther, A., Karl, T., Harley, P., Wiedinmyer, C., Palmer, P. I., and Geron, C.: Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 6, 3181–3210, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-3181-2006, 2006.

Hansen, A. M. K., Hong, J., Raatikainen, T., Kristensen, K., Ylisirniö, A., Virtanen, A., Petäjä, T., Glasius, M., and Prisle, N. L.: Hygroscopic properties and cloud condensation nuclei activation of limonene-derived organosulfates and their mixtures with ammonium sulfate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 14071–14089, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-14071-2015, 2015.

He, J., Li, L., Li, Y., Huang, M., Zhu, Y., and Deng, S.: Synthesis, MS/MS characteristics and quantification of six aromatic organosulfates in atmospheric PM2.5, Atmos. Environ., 290, 119361, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2022.119361, 2022.

Hettiyadura, A. P. S., Jayarathne, T., Baumann, K., Goldstein, A. H., de Gouw, J. A., Koss, A., Keutsch, F. N., Skog, K., and Stone, E. A.: Qualitative and quantitative analysis of atmospheric organosulfates in Centreville, Alabama, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 1343–1359, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-1343-2017, 2017.

Hoyle, C. R., Boy, M., Donahue, N. M., Fry, J. L., Glasius, M., Guenther, A., Hallar, A. G., Huff Hartz, K., Petters, M. D., Petäjä, T., Rosenoern, T., and Sullivan, A. P.: A review of the anthropogenic influence on biogenic secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 321–343, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-321-2011, 2011.

Huang, L., Cochran, R. E., Coddens, E. M., and Grassian, V. H.: Formation of Organosulfur Compounds through Transition Metal Ion-Catalyzed Aqueous Phase Reactions, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 5, 315–321, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00225, 2018a.

Huang, L., Coddens, E. M., and Grassian, V. H.: Formation of Organosulfur Compounds from Aqueous Phase Reactions of S(IV) with Methacrolein and Methyl Vinyl Ketone in the Presence of Transition Metal Ions, ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 3, 1749–1755, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.9b00173, 2019.

Huang, L., Liu, T., and Grassian, V. H.: Radical-Initiated Formation of Aromatic Organosulfates and Sulfonates in the Aqueous Phase, Environmental Science & Technology, 54, 11857–11864, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c05644, 2020.

Huang, L., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Hu, H., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, J.-Z., Chen, T., Cheng, Z., Li, C., Li, Z., and Xiao, H.: Biogenic and Anthropogenic Contributions to Atmospheric Organosulfates in a Typical Megacity in Eastern China, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 128, e2023JD038848, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023JD038848, 2023.

Huang, R.-J., Cao, J., Chen, Y., Yang, L., Shen, J., You, Q., Wang, K., Lin, C., Xu, W., Gao, B., Li, Y., Chen, Q., Hoffmann, T., O'Dowd, C. D., Bilde, M., and Glasius, M.: Organosulfates in atmospheric aerosol: synthesis and quantitative analysis of PM2.5 from Xi'an, northwestern China, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 11, 3447–3456, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-3447-2018, 2018b.

Iinuma, Y., Müller, C., Berndt, T., Böge, O., Claeys, M., and Herrmann, H.: Evidence for the Existence of Organosulfates from β-Pinene Ozonolysis in Ambient Secondary Organic Aerosol, Environmental Science & Technology, 41, 6678–6683, https://doi.org/10.1021/es070938t, 2007.

Jiang, H., Cai, J., Feng, X., Chen, Y., Guo, H., Mo, Y., Tang, J., Chen, T., Li, J., and Zhang, G.: Organosulfur Compounds: A Non-Negligible Component Affecting the Light Absorption of Brown Carbon During North China Haze Events, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 130, e2024JD042043, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JD042043, 2025.

Koss, A. R., Sekimoto, K., Gilman, J. B., Selimovic, V., Coggon, M. M., Zarzana, K. J., Yuan, B., Lerner, B. M., Brown, S. S., Jimenez, J. L., Krechmer, J., Roberts, J. M., Warneke, C., Yokelson, R. J., and de Gouw, J.: Non-methane organic gas emissions from biomass burning: identification, quantification, and emission factors from PTR-ToF during the FIREX 2016 laboratory experiment, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 3299–3319, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-3299-2018, 2018.

Le Breton, M., Wang, Y., Hallquist, Å. M., Pathak, R. K., Zheng, J., Yang, Y., Shang, D., Glasius, M., Bannan, T. J., Liu, Q., Chan, C. K., Percival, C. J., Zhu, W., Lou, S., Topping, D., Wang, Y., Yu, J., Lu, K., Guo, S., Hu, M., and Hallquist, M.: Online gas- and particle-phase measurements of organosulfates, organosulfonates and nitrooxy organosulfates in Beijing utilizing a FIGAERO ToF-CIMS, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 10355–10371, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-10355-2018, 2018.

Li, L., Yang, W., Xie, S., and Wu, Y.: Estimations and uncertainty of biogenic volatile organic compound emission inventory in China for 2008–2018, Science of The Total Environment, 733, 139301, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139301, 2020.

Lin, P., Yu, J. Z., Engling, G., and Kalberer, M.: Organosulfates in Humic-like Substance Fraction Isolated from Aerosols at Seven Locations in East Asia: A Study by Ultra-High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, Environmental Science & Technology, 46, 13118–13127, https://doi.org/10.1021/es303570v, 2012.

Lin, Y., Han, Y., Li, G., Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Li, Z., Li, L., Prévôt, A. S. H., and Cao, J.: Molecular Characteristics of Atmospheric Organosulfates During Summer and Winter Seasons in Two Cities of Southern and Northern China, Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 127, e2022JD036672, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JD036672, 2022.

Liu, P., Ding, X., Li, B.-X., Zhang, Y.-Q., Bryant, D. J., and Wang, X.-M.: Quality assurance and quality control of atmospheric organosulfates measured using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), Atmos. Meas. Tech., 17, 3067–3079, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-17-3067-2024, 2024.

Liu, Y., Wu, Z., Wang, Y., Xiao, Y., Gu, F., Zheng, J., Tan, T., Shang, D., Wu, Y., Zeng, L., Hu, M., Bateman, A. P., and Martin, S. T.: Submicrometer Particles Are in the Liquid State during Heavy Haze Episodes in the Urban Atmosphere of Beijing, China, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 4, 427–432, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00352, 2017.

Liu, Y. C., Wu, Z. J., Qiu, Y. T., Tian, P., Liu, Q., Chen, Y., Song, M., and Hu, M.: Enhanced Nitrate Fraction: Enabling Urban Aerosol Particles to Remain in a Liquid State at Reduced Relative Humidity, Geophysical Research Letters, 50, e2023GL105505, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL105505, 2023.

Lukács, H., Gelencsér, A., Hoffer, A., Kiss, G., Horváth, K., and Hartyáni, Z.: Quantitative assessment of organosulfates in size-segregated rural fine aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 231–238, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-231-2009, 2009.

Ma, J., Ungeheuer, F., Zheng, F., Du, W., Wang, Y., Cai, J., Zhou, Y., Yan, C., Liu, Y., Kulmala, M., Daellenbach, K. R., and Vogel, A. L.: Nontarget Screening Exhibits a Seasonal Cycle of PM2.5 Organic Aerosol Composition in Beijing, Environmental Science & Technology, 56, 7017–7028, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c06905, 2022.

Ma, J., Reininger, N., Zhao, C., Döbler, D., Rüdiger, J., Qiu, Y., Ungeheuer, F., Simon, M., D'Angelo, L., Breuninger, A., David, J., Bai, Y., Li, Y., Xue, Y., Li, L., Wang, Y., Hildmann, S., Hoffmann, T., Liu, B., Niu, H., Wu, Z., and Vogel, A. L.: Unveiling a large fraction of hidden organosulfates in ambient organic aerosol, Nat. Commun., 16, 4098, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59420-y, 2025.

Meng, X., Wu, Z., Chen, J., Qiu, Y., Zong, T., Song, M., Lee, J., and Hu, M.: Particle phase state and aerosol liquid water greatly impact secondary aerosol formation: insights into phase transition and its role in haze events, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 24, 2399–2414, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-24-2399-2024, 2024.

Mutzel, A., Poulain, L., Berndt, T., Iinuma, Y., Rodigast, M., Böge, O., Richters, S., Spindler, G., Sipilä, M., Jokinen, T., Kulmala, M., and Herrmann, H.: Highly Oxidized Multifunctional Organic Compounds Observed in Tropospheric Particles: A Field and Laboratory Study, Environmental Science & Technology, 49, 7754–7761, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b00885, 2015.

Ohno, P. E., Wang, J., Mahrt, F., Varelas, J. G., Aruffo, E., Ye, J., Qin, Y., Kiland, K. J., Bertram, A. K., Thomson, R. J., and Martin, S. T.: Gas-Particle Uptake and Hygroscopic Growth by Organosulfate Particles, ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 6, 2481–2490, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.2c00195, 2022.

Passananti, M., Kong, L., Shang, J., Dupart, Y., Perrier, S., Chen, J., Donaldson, D. J., and George, C.: Organosulfate Formation through the Heterogeneous Reaction of Sulfur Dioxide with Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Long-Chain Alkenes, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 55, 10336–10339, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201605266, 2016.

Qiu, Y., Liu, Y., Wu, Z., Wang, F., Meng, X., Zhang, Z., Man, R., Huang, D., Wang, H., Gao, Y., Huang, C., and Hu, M.: Predicting Atmospheric Particle Phase State Using an Explainable Machine Learning Approach Based on Particle Rebound Measurements, Environmental Science & Technology, 57, 15055–15064, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c05284, 2023.

Riva, M., Tomaz, S., Cui, T., Lin, Y.-H., Perraudin, E., Gold, A., Stone, E. A., Villenave, E., and Surratt, J. D.: Evidence for an Unrecognized Secondary Anthropogenic Source of Organosulfates and Sulfonates: Gas-Phase Oxidation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Presence of Sulfate Aerosol, Environmental Science & Technology, 49, 6654–6664, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b00836, 2015.

Riva, M., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Zhang, Z., Gold, A., and Surratt, J. D.: Chemical characterization of secondary organic aerosol constituents from isoprene ozonolysis in the presence of acidic aerosol, Atmospheric Environment, 130, 5–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.06.027, 2016a.

Riva, M., Da Silva Barbosa, T., Lin, Y.-H., Stone, E. A., Gold, A., and Surratt, J. D.: Chemical characterization of organosulfates in secondary organic aerosol derived from the photooxidation of alkanes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11001–11018, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11001-2016, 2016b.

Riva, M., Da Silva Barbosa, T., Lin, Y.-H., Stone, E. A., Gold, A., and Surratt, J. D.: Chemical characterization of organosulfates in secondary organic aerosol derived from the photooxidation of alkanes, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11001–11018, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11001-2016, 2016c.

Riva, M., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Lei, Z., Olson, N. E., Boyer, H. C., Narayan, S., Yee, L. D., Green, H. S., Cui, T., Zhang, Z., Baumann, K., Fort, M., Edgerton, E., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Rose, C. A., Ribeiro, I. O., e Oliveira, R. L., dos Santos, E. O., Machado, C. M. D., Szopa, S., Zhao, Y., Alves, E. G., de Sá, S. S., Hu, W., Knipping, E. M., Shaw, S. L., Duvoisin Junior, S., de Souza, R. A. F., Palm, B. B., Jimenez, J.-L., Glasius, M., Goldstein, A. H., Pye, H. O. T., Gold, A., Turpin, B. J., Vizuete, W., Martin, S. T., Thornton, J. A., Dutcher, C. S., Ault, A. P., and Surratt, J. D.: Increasing Isoprene Epoxydiol-to-Inorganic Sulfate Aerosol Ratio Results in Extensive Conversion of Inorganic Sulfate to Organosulfur Forms: Implications for Aerosol Physicochemical Properties, Environmental Science & Technology, 53, 8682–8694, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b01019, 2019.

Rudziński, K. J., Gmachowski, L., and Kuznietsova, I.: Reactions of isoprene and sulphoxy radical-anions – a possible source of atmospheric organosulphites and organosulphates, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 2129–2140, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-2129-2009, 2009.

Sakulyanontvittaya, T., Guenther, A., Helmig, D., Milford, J., and Wiedinmyer, C.: Secondary Organic Aerosol from Sesquiterpene and Monoterpene Emissions in the United States, Environmental Science & Technology, 42, 8784–8790, https://doi.org/10.1021/es800817r, 2008.

Song, M., Jeong, R., Kim, D., Qiu, Y., Meng, X., Wu, Z., Zuend, A., Ha, Y., Kim, C., Kim, H., Gaikwad, S., Jang, K. S., Lee, J. Y., and Ahn, J.: Comparison of Phase States of PM2.5over Megacities, Seoul and Beijing, and Their Implications on Particle Size Distribution, Environmental Science and Technology, 56, 17581–17590, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c06377, 2022.

Staudt, S., Kundu, S., Lehmler, H.-J., He, X., Cui, T., Lin, Y.-H., Kristensen, K., Glasius, M., Zhang, X., Weber, R. J., Surratt, J. D., and Stone, E. A.: Aromatic organosulfates in atmospheric aerosols: Synthesis, characterization, and abundance, Atmospheric Environment, 94, 366–373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.05.049, 2014.

Surratt, J. D., Gómez-González, Y., Chan, A. W. H., Vermeylen, R., Shahgholi, M., Kleindienst, T. E., Edney, E. O., Offenberg, J. H., Lewandowski, M., Jaoui, M., Maenhaut, W., Claeys, M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Organosulfate Formation in Biogenic Secondary Organic Aerosol, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 112, 8345–8378, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp802310p, 2008.

Tang, J., Li, J., Su, T., Han, Y., Mo, Y., Jiang, H., Cui, M., Jiang, B., Chen, Y., Tang, J., Song, J., Peng, P., and Zhang, G.: Molecular compositions and optical properties of dissolved brown carbon in biomass burning, coal combustion, and vehicle emission aerosols illuminated by excitation–emission matrix spectroscopy and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry analysis, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 2513–2532, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-2513-2020, 2020.

Tao, S., Lu, X., Levac, N., Bateman, A. P., Nguyen, T. B., Bones, D. L., Nizkorodov, S. A., Laskin, J., Laskin, A., and Yang, X.: Molecular Characterization of Organosulfates in Organic Aerosols from Shanghai and Los Angeles Urban Areas by Nanospray-Desorption Electrospray Ionization High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, Environmental Science & Technology, 48, 10993–11001, https://doi.org/10.1021/es5024674, 2014.

Tolocka, M. P. and Turpin, B.: Contribution of Organosulfur Compounds to Organic Aerosol Mass, Environmental Science & Technology, 46, 7978–7983, https://doi.org/10.1021/es300651v, 2012.

Wach, P., Spólnik, G., Rudziński, K. J., Skotak, K., Claeys, M., Danikiewicz, W., and Szmigielski, R.: Radical oxidation of methyl vinyl ketone and methacrolein in aqueous droplets: Characterization of organosulfates and atmospheric implications, Chemosphere, 214, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.026, 2019.

Wang, G., Zhang, R., Gomez, M. E., Yang, L., Levy Zamora, M., Hu, M., Lin, Y., Peng, J., Guo, S., Meng, J., Li, J., Cheng, C., Hu, T., Ren, Y., Wang, Y., Gao, J., Cao, J., An, Z., Zhou, W., Li, G., Wang, J., Tian, P., Marrero-Ortiz, W., Secrest, J., Du, Z., Zheng, J., Shang, D., Zeng, L., Shao, M., Wang, W., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhu, Y., Li, Y., Hu, J., Pan, B., Cai, L., Cheng, Y., Ji, Y., Zhang, F., Rosenfeld, D., Liss, P. S., Duce, R. A., Kolb, C. E., and Molina, M. J.: Persistent sulfate formation from London Fog to Chinese haze, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 13630–13635, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1616540113, 2016.

Wang, H., Ma, X., Tan, Z., Wang, H., Chen, X., Chen, S., Gao, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Yang, X., Yuan, B., Zeng, L., Huang, C., Lu, K., and Zhang, Y.: Anthropogenic monoterpenes aggravating ozone pollution, National Science Review, 9, nwac103, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwac103, 2022a.

Wang, K., Zhang, Y., Huang, R.-J., Wang, M., Ni, H., Kampf, C. J., Cheng, Y., Bilde, M., Glasius, M., and Hoffmann, T.: Molecular Characterization and Source Identification of Atmospheric Particulate Organosulfates Using Ultrahigh Resolution Mass Spectrometry, Environmental Science & Technology, 53, 6192–6202, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b02628, 2019a.

Wang, Y., Ren, J., Huang, X. H. H., Tong, R., and Yu, J. Z.: Synthesis of Four Monoterpene-Derived Organosulfates and Their Quantification in Atmospheric Aerosol Samples, Environmental Science & Technology, 51, 6791–6801, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b01179, 2017.

Wang, Y., Hu, M., Guo, S., Wang, Y., Zheng, J., Yang, Y., Zhu, W., Tang, R., Li, X., Liu, Y., Le Breton, M., Du, Z., Shang, D., Wu, Y., Wu, Z., Song, Y., Lou, S., Hallquist, M., and Yu, J.: The secondary formation of organosulfates under interactions between biogenic emissions and anthropogenic pollutants in summer in Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 10693–10713, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-10693-2018, 2018.

Wang, Y., Ma, Y., Li, X., Kuang, B. Y., Huang, C., Tong, R., and Yu, J. Z.: Monoterpene and Sesquiterpene α-Hydroxy Organosulfates: Synthesis, MS/MS Characteristics, and Ambient Presence, Environmental Science & Technology, 53, 12278–12290, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04703, 2019b.

Wang, Y., Hu, M., Wang, Y.-C., Li, X., Fang, X., Tang, R., Lu, S., Wu, Y., Guo, S., Wu, Z., Hallquist, M., and Yu, J. Z.: Comparative Study of Particulate Organosulfates in Contrasting Atmospheric Environments: Field Evidence for the Significant Influence of Anthropogenic Sulfate and NOx, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 7, 787–794, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00550, 2020.

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, J.-Z., Shao, J., Liu, P., Zhu, W., Cheng, Z., Li, Z., Yan, N., and Xiao, H.: Organosulfates in atmospheric aerosols in Shanghai, China: seasonal and interannual variability, origin, and formation mechanisms, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 2959–2980, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-2959-2021, 2021a.

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, J.-Z., Shao, J., Liu, P., Zhu, W., Cheng, Z., Li, Z., Yan, N., and Xiao, H.: Organosulfates in atmospheric aerosols in Shanghai, China: seasonal and interannual variability, origin, and formation mechanisms, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 2959–2980, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-2959-2021, 2021b.

Wang, Y., Ma, Y., Kuang, B., Lin, P., Liang, Y., Huang, C., and Yu, J. Z.: Abundance of organosulfates derived from biogenic volatile organic compounds: Seasonal and spatial contrasts at four sites in China, Science of The Total Environment, 806, 151275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151275, 2022b.

Wang, Y., Feng, Z., Yuan, Q., Shang, D., Fang, Y., Guo, S., Wu, Z., Zhang, C., Gao, Y., Yao, X., Gao, H., and Hu, M.: Environmental factors driving the formation of water-soluble organic aerosols: A comparative study under contrasting atmospheric conditions, Science of The Total Environment, 866, 161364, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161364, 2023a.

Wang, Y., Liang, S., Le Breton, M., Wang, Q. Q., Liu, Q., Ho, C. H., Kuang, B. Y., Wu, C., Hallquist, M., Tong, R., and Yu, J. Z.: Field observations of C2 and C3 organosulfates and insights into their formation mechanisms at a suburban site in Hong Kong, Science of The Total Environment, 904, 166851, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166851, 2023b.

Wei, L., Liu, R., Liao, C., Ouyang, S., Wu, Y., Jiang, B., Chen, D., Zhang, T., Guo, Y., and Liu, S. C.: An observation-based analysis of atmospheric oxidation capacity in Guangdong, China, Atmospheric Environment, 318, 120260, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.120260, 2024.

Xu, L., Tsona, N. T., and Du, L.: Relative Humidity Changes the Role of SO2 in Biogenic Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation, The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 12, 7365–7372, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01550, 2021a.

Xu, L., Yang, Z., Tsona, N. T., Wang, X., George, C., and Du, L.: Anthropogenic–Biogenic Interactions at Night: Enhanced Formation of Secondary Aerosols and Particulate Nitrogen- and Sulfur-Containing Organics from β-Pinene Oxidation, Environmental Science & Technology, 55, 7794–7807, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c07879, 2021b.

Xu, R., Chen, Y., Ng, S. I. M., Zhang, Z., Gold, A., Turpin, B. J., Ault, A. P., Surratt, J. D., and Chan, M. N.: Formation of Inorganic Sulfate and Volatile Nonsulfated Products from Heterogeneous Hydroxyl Radical Oxidation of 2-Methyltetrol Sulfate Aerosols: Mechanisms and Atmospheric Implications, Environ. Sci. Tech. Lett., 11, 968–974, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.4c00451, 2024.

Yang, T., Xu, Y., Ye, Q., Ma, Y.-J., Wang, Y.-C., Yu, J.-Z., Duan, Y.-S., Li, C.-X., Xiao, H.-W., Li, Z.-Y., Zhao, Y., and Xiao, H.-Y.: Spatial and diurnal variations of aerosol organosulfates in summertime Shanghai, China: potential influence of photochemical processes and anthropogenic sulfate pollution, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 13433–13450, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-13433-2023, 2023.

Yang, T., Xu, Y., Ma, Y.-J., Wang, Y.-C., Yu, J. Z., Sun, Q.-B., Xiao, H.-W., Xiao, H.-Y., and Liu, C.-Q.: Field Evidence for Constraints of Nearly Dry and Weakly Acidic Aerosol Conditions on the Formation of Organosulfates, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 11, 981–987, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.4c00522, 2024.

Yassine, M. M., Harir, M., Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E., and Schmitt-Kopplin, P.: Structural characterization of organic aerosol using Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: Aromaticity equivalent approach, Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 28, 2445–2454, https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7038, 2014.

Ye, C., Lu, K., Song, H., Mu, Y., Chen, J., and Zhang, Y.: A critical review of sulfate aerosol formation mechanisms during winter polluted periods, Journal of Environmental Sciences, 123, 387–399, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2022.07.011, 2023.

Ye, J., Abbatt, J. P. D., and Chan, A. W. H.: Novel pathway of SO2 oxidation in the atmosphere: reactions with monoterpene ozonolysis intermediates and secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 5549–5565, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-5549-2018, 2018.

Zhang, Y., Chen, Y., Lei, Z., Olson, N. E., Riva, M., Koss, A. R., Zhang, Z., Gold, A., Jayne, J. T., Worsnop, D. R., Onasch, T. B., Kroll, J. H., Turpin, B. J., Ault, A. P., and Surratt, J. D.: Joint Impacts of Acidity and Viscosity on the Formation of Secondary Organic Aerosol from Isoprene Epoxydiols (IEPOX) in Phase Separated Particles, ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 3, 2646–2658, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.9b00209, 2019.

Zhang, Z., Jiang, J., Lu, B., Meng, X., Herrmann, H., Chen, J., and Li, X.: Attributing Increases in Ozone to Accelerated Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds at Reduced Nitrogen Oxides Concentrations, PNAS Nexus, 1, pgac266, https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac266, 2022.

Zhao, D., Schmitt, S. H., Wang, M., Acir, I.-H., Tillmann, R., Tan, Z., Novelli, A., Fuchs, H., Pullinen, I., Wegener, R., Rohrer, F., Wildt, J., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Wahner, A., and Mentel, T. F.: Effects of NOx and SO2 on the secondary organic aerosol formation from photooxidation of α-pinene and limonene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 1611–1628, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-1611-2018, 2018.