the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Driving factors for the activity coefficient of atmospheric ammonium nitrate: discrepancies among thermodynamic models and impact on nitrate pollutions

Ruilin Wan

Guangjie Zheng

Yuyang Li

Xiaolin Duan

Jingkun Jiang

Kebin He

Semi-volatile NH4NO3 is a major component of atmospheric aerosols, and its environmental and climate effects are largely regulated by the gas-particle partitioning. The activity coefficient of NH4NO3, γAN, is one key parameter controlling the gas-particle partitioning of nitrate, with lower γAN typically favouring particle-phase partitioning of nitrate. However, the γAN dependence on meteorological condition and chemical profile remains uncertain. Here we investigated into this issue with comprehensive simulations and ambient observations, based on results of three widely-used thermodynamic models, i.e. ISORROPIA, E-AIM, and AIOMFAC. Correspondingly, AIOMFAC estimate higher particle phase nitrate values. Across all models, ranges between 10−2 and 10−1, with AIOMFAC results ∼ 33 % lower than E-AIM and ISORROPIA. Correspondingly, AIOMFAC estimate higher particle phase nitrate values. For all three models and all chemical profiles tested, the correlates positively with relative humidity (RH) and temperature, and RH generally contributes larger variations. In comparison, the effect of chemical composition on is more complex and is strongly modulated by RH, with differed dependence pattern observed at varying RH levels. Furthermore, responds more strongly to changes of particle chemical profile in E-AIM, whereas in ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC is more sensitive to meteorological variations. As E-AIM is typically considered as the benchmark thermodynamic model, these results suggest the potential under-representation of chemical profiles in predicting for ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC. The corresponding influence on 3-D chemical-transport model predictions of NH4NO3 are encouraged in future studies.

- Article

(3842 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1538 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Nitrate is a key component of atmospheric aerosols, exerting substantial influence on haze formation and climate (Li et al., 2019, 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2019). As nitrate is semi-volatile, the gas–particle partitioning process plays a critical role in regulating the particulate nitrate concentrations (Qi et al., 2023; Zhai et al., 2021), new particle formation and growth (Li et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2022), global nitrogen deposition rates (Arangio et al., 2022; Nenes et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2024), and the atmospheric photochemical oxidative capacity (Cao et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2025). Nitrate gas–particle partitioning is governed by the interplay of gas–liquid equilibrium, charge balance, acid dissociation equilibrium, and the non-ideality of aerosol solution (Guo et al., 2015, 2017b; Nenes et al., 2020, 2021; Pye et al., 2020). Due to its complexity, the mechanisms and influencing factors of nitrate gas-particle partitioning are still not fully understood, as indicated by the discrepancy between observations and model simulations (Guo et al., 2015, 2017a), and among different thermodynamic models. Inaccurate estimation of nitrate gas-particle partitioning is one major source of simulation uncertainty for nitrate concentration and its environmental and climate effects (Mezuman et al., 2016; Nault et al., 2021; Norman et al., 2025).

Among the potential influencing factors, non-ideality is the one with the largest uncertainty. Non-ideality refers to the degree to which the thermodynamic properties of a solution deviate from the behavior of an ideal solution, which is typically quantitatively described by the activity coefficient γ. Conditions such as high ionic strength and increased solution complexity (e.g., coexistence of multiple organic and inorganic species) can drive γ away from unity (Atkins et al., 2023). Deliquescent atmospheric aerosols are highly concentrated solutions with strong non-ideality (Clegg et al., 1998a, b). However, in-situ measurement of γ for ambient aerosols is challenging due to the extremely high ionic strengths, the complex and varied aerosol compositions, the low concentrations and therefore high measurement uncertainties for relevant species, etc. (Li et al., 2022; Nenes et al., 1998; Pitzer, 1987). Consequently, the non-ideality for aerosols is typically estimated by state-of-the-art thermodynamic models.

Three thermodynamic models are widely adopted to estimate non-ideality in aerosols, i.e. the ISORROPIA (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007; Nenes et al., 1998), the Extended Aerosol Inorganics Model (E-AIM) (Friese and Ebel, 2010; Wexler and Clegg, 2002) and Aerosol Inorganic-Organic Mixtures Functional groups Activity Coefficients (AIOMFAC) (Zuend et al., 2008, 2011). These models typically incorporate factors such as ionic strength, electrostatic interactions, and organic–inorganic coupling to enhance the accuracy of simulations, but the detailed assumptions differed. The ISORROPIA employs an extended Debye-Hückel form (“Bromley's formula”), in which non-ideality is parameterized through empirical ion-pair terms. While computationally efficient, this approach assumes simplified binary ion interactions and is known to become less accurate at elevated ionic strengths of above ∼ 6 mol kg−1 (Bromley, 1973; Nenes et al., 1998). The E-AIM calculated γ for individual ions based on the Pitzer–Simonson–Clegg formula, which accounted for long-range electrostatic interactions via Debye-Hückel effect and short-range binary/ternary ion–ion interactions through a Margules expansion (Clegg et al., 1992; Pitzer and Simonson, 1986), with parameters from empirical data (Carslaw et al., 1995; Clegg et al., 1998b; Friese and Ebel, 2010). This structure enables E-AIM to better capture non-ideal behavior in highly concentrated electrolyte solutions. AIOMFAC combines a Pitzer-like electrolyte model with a modified UNIFAC approach, representing long-, middle-, and short-range organic–inorganic interactions, allowing for explicit treatment of more organic–inorganic interactions (Zuend et al., 2010; Zünd, 2007). E-AIM and ISORROPIA include gas–liquid equilibrium modules (Clegg et al., 2008; Clegg and Brimblecombe, 1990; Wexler and Clegg, 2002) and use the Zdanovskii-Stokes-Robinson method for aerosol water content (AWC), whereas AIOMFAC doesn't perform gas–particle phase-equilibrium solving and predicts water activity directly as RH (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016; Zuend et al., 2008). Generally, E-AIM is considered as the most accurate “benchmark” model, and ISORROPIA is optimized for computing speed and is widely adopted in chemical transport models, while AIOMFAC offers the strongest capability for inorganic–organic interaction predictions (Hull et al., 2025; Li et al., 2022; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). In atmospheric aerosols, the NO is usually neutralized by NH and exist in the form of NH4NO3 (Nowak et al., 2010; Pathak et al., 2009; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016).

Our previous studies have revealed that the mean activity coefficient of ammonium nitrate, , is a key parameter influencing the gas-particle partitioning of nitrate, with lower γAN typically favouring higher particle-phase partitioning of nitrate (see Sect. S1 in the Supplement) (Zheng et al., 2022). This can be interpreted in that, the lower activity coefficient would reduce the activity of nitrate at given concentrations, while it's the activity that matters in the gas-particle equilibrium. Therefore, at given gas-phase concentrations, the equilibrium activity is fixed, while the actual particle-phase concentration would increase with decreased activity coefficient γ. Note that for easy comparison with individual ions and among different thermodynamic models, the square form of γAN, or , is adopted in following discussions (Zheng et al., 2022). Previous studies on thermodynamic model comparison and performance evaluations on non-ideality characterizations focused primarily on acidity (i.e., the activity coefficient of H+) (Liu et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2019; Song et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2022). These studies have shown that ISORROPIA, E-AIM, and AIOMFAC can yield systematically different predictions of aerosol pH under identical chemical and meteorological conditions, partially due to differences in their estimation of ion activity coefficients including γH+ and . Despite these documented discrepancies in acidity-related diagnostics, a comparable inter-model evaluation of the ammonium nitrate activity coefficient and its sensitivity to chemical and meteorological drivers remains scarce. To bridge this gap, we examined into activity coefficient of atmospheric ammonium nitrate based on both simulated cases and worldwide ambient data. The dependences of on different meteorological conditions and chemical profiles are compared among three thermodynamic models of ISORROPIA, E-AIM and AIOMFAC. The variability across different regions are further assessed through tests of worldwide observation data. The implications on global nitrate estimations and atmospheric chemistry are also discussed.

2.1 Running different thermodynamic models

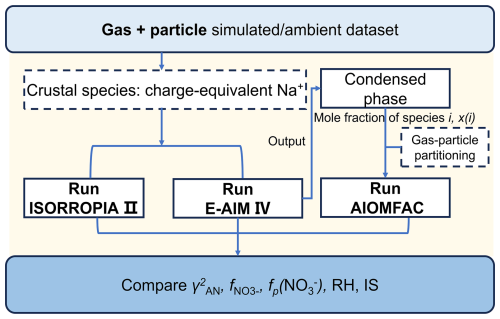

Three thermodynamic models were utilized to simulate the non-ideality in aerosols, i.e. the ISORROPIA (v2.3) (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007; Nenes et al., 1998), E-AIM (version IV) (Friese and Ebel, 2010; Wexler and Clegg, 2002), and AIOMFAC (Zuend et al., 2008, 2011). However, to enable the direct comparison of results among these three models, a set of pre- and post-processing are required to harmonize their inputs and outputs. The overall flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1Flow chart of comparison experiments among the three thermodynamic models of ISORROPIA, E-AIM and AIOMFAC.

Inputs of ISORROPIA and E-AIM are similar, which are the total (gas + particle) concentrations, relative humidity (RH) and temperature. Note here we run both models in forward and metastable modes. However, as E-AIM is unable to explicitly treat all crustal species (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, K+), these species are converted to charge-equivalent Na+ in model comparison studies (Parworth et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2019). In comparison, inputs of AIOMFAC require condensed-phase concentrations together with AWC, which can be acquired from the outputs of either ISORROPIA or E-AIM. Our tests show that the estimated AWC agreed well between these two models, while E-AIM generally provides a more balanced ionic output, particularly in Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O scenario (see Sect. S2 and Figs. S1–S2 in the Supplement). Therefore, the predicted condensed-phase concentrations and AWC from E-AIM are used as the inputs for AIOMFAC in subsequent calculation.

The gas-particle partitioning of HNO3 can be represented by , namely the molar fraction of particle-phase NO in total nitric acid HNO3,tot as:

where [X] hereinafter represents the molar concentration of species X (µmol m−3).

The is directly estimated in ISORROPIA and E-AIM, while AIOMFAC does not directly provide gas-particle partitioning results. Therefore, for AIOMFAC the is calculated in a similar approach to that described by Pye et al. (2018) as:

where mi is molality of ion i (mol kg−1 water) and γi is molality-based activity coefficient of ion i. The p is ambient pressure in Pa, normally taken as 101 325 Pa. The Tis absolute temperature in Kelvin, R refers to universal gas constant with a value of 8.314 J mol−1 K−1, is the temperature-dependent equilibrium constant of specie HNO3 (see Supplement Table S1), and is the total (gas and particle phase) concentration of HNO3 in mol m−3.

2.2 Scenario settings for thermodynamic model evaluations

Here we investigated into the potential influencing factors of for two aerosol systems, i.e. the NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system and the Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system. The former system is frequently adopted in chamber experiments and simplified theoretical calculations, as they represented major aerosol compositions of (NH4)2SO4 and NH4NO3 (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016; Weber et al., 2016). The latter system is designed to represent the ambient aerosol systems, as global inorganic aerosol components are dominated by ammonia sulfate and ammonia nitrate with crustal species existent (Liu et al., 2025).

Several representative scenarios were set up to examine the effect of meteorological condition, chemical profile and their relative importance on . The Scenario SNA is designed for the NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system, while the others are based on the Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system. The anion profile is represented by , defined as the molar ratio of NO to total anions (Eq. 3a). The cation profile is represented by fNVC, defined as the molar ratio of Na+ to total cations (Eq. 3b) as:

The detailed scenario settings are listed below.

-

Scenario SNA. This scenario examines in the absence of Na+. For this system, the particle phase contains only (NH4)2SO4 and NH4NO3, and their relative ratio are adjusted by varying the ratio of total NO to total SO. The total amount of anions is set to 1 µmol m−3, corresponding to approximately 62–96 µg m−3 depending on anion composition (e.g., NO versus SO), and total ammonia NH3,tot is fixed at 2 µmol m−3 (34 µg m−3), ensuring an excess relative to anions. Here we varied the temperature from 265 to 305 K at a step size of 1 K, and the relative humidity from 60 % to 95 % at a step size of 1 %.

-

Scenario Met. This scenario is to investigate the influence of meteorological condition on for the Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system. The total Na is fixed at 5 % of the total SO, while the remaining setting is the same as Scenario SNA.

-

Scenario Chem. This scenario is to test the effect of chemical profile on over a wider concentration range. The temperature is fixed at 288 K, and the relative humidity is fixed at 60 %, 75 % and 90 %. Na varies from 0 % to 95 % at a step size of 2 %. Remaining variables are the same as Scenario SNA.

-

Scenario Full. This scenario is to compare relative importance of meteorological condition and chemical profile on across a comprehensive range of conditions, to fully consider influences of all variables through Sobol's analysis. The temperature range is varied from 265 to 305 K at a step size of 5 K; the relative humidity range is from 60 % to 95 % at a step size of 5 %. Na accounts for 0 %–80 % of total cations with a step size of 10 %. Remaining variables are the same as Scenario SNA.

2.3 Ambient data

Long term observational data of inorganic ions (Na+, SO, NH, NO, Cl−, Ca2+, K+, Mg2+) in PM2.5 and gas pollutants (NH3, HNO3, HCl) in USA (Edgerton et al., 2006; Hansen et al., 2003), Canada (Tao and Murphy, 2019) and China (Duan et al., 2025) are collected from published work as detailed in Table S2. For direct comparison, crustal species (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, K+) were transformed into equivalent Na+. In addition, all observational data were harmonized to a uniform temporal resolution, ensuring that the analysis was consistently conducted on a daily basis.

3.1 Influence of on nitrate partitioning with different thermodynamic models

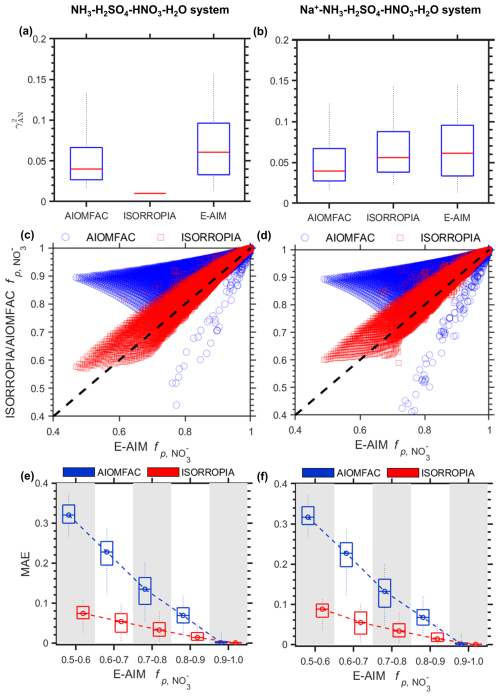

The estimated across all three thermodynamic models generally fall between 10−2 and 10−1. In the NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O aerosol system, ISORROPIA constantly predicts to be 1.0 × 10−2 across all range of chemical compositions and meteorological conditions (see Fig. 2a). In comparison, estimated by the E-AIM (median ∼ 6.1 × 10−2) is generally 33 % higher than that estimated by AIOMFAC (median ∼ 4.0 × 10−2). In the Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O aerosol system, the presence of Na+ shows minor influence on the estimation for AIOMFAC and E-AIM. In comparison, after introducing Na+ to system, the by ISORROPIA is no longer constant but begins to vary. In general, its estimation is slightly (∼ 8 %) lower than that of E-AIM, with a median of ∼ 5.6 × 10−2 (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2Comparisons of and among three models, for NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O (a, c, e) system based on Scenario SNA, and Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O (b, d, f) system based on Scenario Met. (a, b) Comparison of estimated distributions for different models. (c, d) The estimated by ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC as compared with that estimated by E-AIM. (e, f) Distribution of the mean absolute error (MAE) in estimated with changing E-AIM predicted . The boxes and whiskers indicate the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles, respectively.

The differences in among the models lead to corresponding variations in . Although ISORROPIA align relatively well with E-AIM considering the generally smaller differences, the could still differ by ∼ ± 0.1. In comparison, AIOMFAC tends to underestimates and consequently overestimates as compared with the other two models (Fig. 2c, d). Moreover, the discrepancies depend strongly on the particle-phase preference regime of nitrate, as characterized by the E-AIM predicted here. The estimated differences are generally higher when the E-AIM predicted values are lower. When the estimated by E-AIM ranged 0.5–0.6, that estimated by AIOMFAC and ISORROPIA could deviate ∼ 0.38 and ∼ 0.1, respectively. In comparison, the model discrepancies are nearly negligible at higher values of over 0.9. The large discrepancy between AIOMFAC and the other two models can be largely explained by the absence of gas-phase constraint in its calculations. This may induce large uncertainties, as has been well illustrated in previous studies (Hennigan et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2019; Pye et al., 2020). In addition to gas-particle partitioning, other relative variables will also be affected due to different mathematical solutions, see further comparison in Sect. S3 and Figs. S2–S3.

3.2 Influencing factors of for Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system

As shown in Fig. 2a, ISORROPIA assigns a constant of 0.010 for the NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system. In addition, crustal ions like Na+ are typically present under ambient conditions. Therefore, below we compared the influencing factors of the three models with the Na+-NH3-H2SO4-HNO3-H2O system.

In dilute water solution, γ is a function of IS only, as described in the Debye-Hückel equation (Zünd, 2007) of:

where γi is the activity coefficient of ion i, zj represents charges of ion i, and the constant A is a function of temperature and properties relative to water such as density and static permittivity. The IS (µmol kg−1) is the ionic strength defined as:

Where mi (mol kg−1 water) is the molality of ion i. The IS is an indicator of the overall concentration of ions in solutions, and is independent of chemical profiles by definition. That is, different ions such as NH4+ and Na+ would yield the same IS when they have identical charges and molality.

The IS is mainly determined by mi. In aerosols, the mi depends largely on AWC, while AWC is modulated mainly by RH and minorly by chemical species (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016; Tan et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2022). Therefore, we expect a larger dependence of IS on RH than chemical profiles in aerosols, as also supported in our tests (Fig. S5). Moreover, as the solutions became highly concentrated, short range forces F (e.g., binary or ternary interactions of ions) begin to play an important role, which depends on the detailed ionic pairs or the chemical compositions. This would result in the deviation from the ideal Debye-Hückel equation.

Overall, we show that both meteorological conditions (RH and T) and chemical profiles could influence the activity coefficients, where the RH influence is mainly through the AWC and therefore IS, while the influences of temperature and chemical profiles are mainly through the thermodynamic equilibrium. The corresponding relationships are illustrated with the interpretive structural model in Fig. S6. Below we investigated into their detailed influences.

3.2.1 Influences of meteorological condition at given chemical profile

-

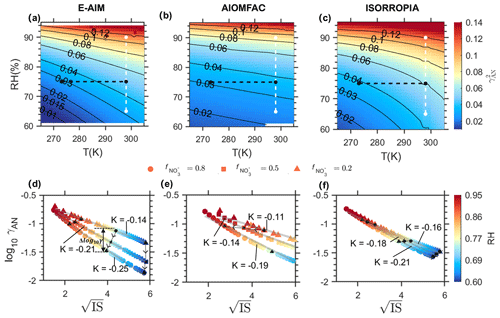

Influences of RH and T at given chemical profile. Figure 3 shows the dependence of on temperature and RH based on the Scenario SNA-Na results. To exclude the influence of particle-phase compositions, here we selected data with 0.60 only (more values test can be found in Fig. S7). As shown in Fig. 3a–c, calculated by all three models increases with rising T and RH, while with different sensitivities. In general, the sensitivity follows the order of E-AIM ≈ ISORROPIA > AIOMFAC, while the sensitivity difference between AIOMFAC and the other two models is much larger for temperature than for RH. For example, at fixed RH of 75 % while temperature increases from 273 to 298 K (see black dashed line in Fig. 3), the would change by ∼ 0.02 for ISORROPIA and E-AIM, which is 4 times that of AIOMFAC (∼ 0.005). In contrast, for fixed temperature of 298 K while RH increases from 65 % to 90 % (see white dashed line in Fig. 3), the would change by ∼ 0.08 for ISORROPIA and E-AIM, while that change of AIOMFAC is only slightly smaller (∼ 0.07).

Relative humidity affects more strongly than temperature in terms of typical variation ranges under ambient conditions. For example, at a fixed temperature (T= 298 K), varying RH from 65 % to 90 % (ΔRH = 25 %) would lead to an average 0.075 across all models. However, at a fixed humidity (RH = 75 %), increasing temperature from 273 to 298 K (ΔT= 25 K) only induces an average of 0.015. Our analysis across different timescales further show that RH consistently exerts a stronger influence than T in real atmospheric conditions. In a temperate continental monsoon climate such as Beijing, RH typically fluctuates by 20 %–40 % within a day, while diurnal T variations are around 10°C, meaning that humidity changes dominate the daily variability of . Over seasonal scales, RH differs by about 15 %–25 % between summer and winter, whereas T differences can exceed 30 °C; nevertheless, the larger relative impact of RH makes it the primary driver in meteorology of seasonal variability. On even longer timescales (e.g., interannual), annual mean RH varies only within 5 %–10 %, while mean T shifts by 1–3 °C, again pointing to humidity as the determining factor in meteorology. Therefore, RH dominates the variability of at daily, seasonal, and interannual scales, whereas the role of T is secondary for meteorology.

-

Ionic strength as the primary pathway of RH influence on . As discussed above, the influence of RH on is most likely through IS, which is illustrated in Fig. 3d–f. The general patterns are similar for all the three models. The relationship generally followed the form as outlined in Debye-Hückel law in dilute solutions that log 10γ is inversely proportional to . However, the detailed sensitivity (as quantified by the slope K in plots; Fig. 3d–f) differs with the particle compositions , with higher sensitivity (absolute value of K) predicted at higher levels. Moreover, the influence of chemical compositions differs much among the three models. E-AIM is the most sensitive model to chemical composition, as reflected in much larger variation of K with . When change from 0.2 to 0.8, the slope K would change by 0.11 in E-AIM, which is much larger than that in ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC (K changes by ∼ 0.05 and ∼ 0.08, respectively). This indicates a higher sensitivity of estimation to chemical profile for the E-AIM model, as also revealed in Sect. 4.3. In comparison, the relationship is independent on temperature (see Fig. S8).

Figure 3Comparison of the dependence of γAN on different influencing factors as estimated by E-AIM (a, d); AIOMFAC (b, e); ISORROPIA (c, f). (a–c). The under different T and RH conditions, with fixed at 0.60. (d–f) Dependence of γAN to IS and RH at three different levels. Here the temperature is fixed at 273 K. Data are based on Scenario Met.

3.2.2 Influence of particle-phase chemical profile at given meteorological conditions

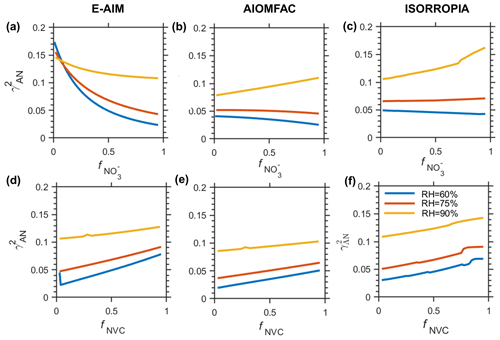

Figure 4 shows the dependence of on particle-phase anion profiles (as characterized by ; Sect. 2.2) and cation profiles (as characterized by fNVC; Sect. 2.2). Unlike the response to meteorological condition, influence of particle-phase chemical profiles on varies markedly among the three thermodynamic models.

Figure 4The under different (a–c) and (d–f) fNVC estimated by (a), (d) E-AIM; (b), (e) AIOMFAC; (c), (f) ISORROPIA when the opposite ions () is fixed at 0.5. RH = 90 %, 75 %, 60 % are selected to represent different RH levels. Data are based on Scenario Chem.

The sensitivity of to anion profile (or ) is strongly modulated by RH, in terms of both direction and absolute value. The E-AIM predicted a consistently negative correlation of – across all RH ranges (Fig. 4a). In addition, the magnitude of the correlation weakens substantially from lower to higher RH. For instance, when changes from 0.1 to 0.9, the is ∼ −0.15 at RH = 60 %, which weakens to only ∼ −0.03 at RH = 90 %. In contrast, AIOMFAC and ISORROPIA exhibit weak negative correlation at relative lower RH. However, that pattern is reversed to a clear positive correlation at higher RH (e.g., 90 %) (Fig. 4b, c).

Influence of RH on the sensitivity of to cation profile (or fNVC) is much weaker (Fig. 4d–f). All three models show positive correlations at all RH ranges. Yet, the sensitivity shows certain dependence on RH. For E-AIM and AIOMFAC, the sensitivity of to fNVC weakens slightly with increasing RH, as indicated by the smaller slopes at higher RH (Fig. 4d, e). In comparison, the relationship for ISORROPIA remains largely insensitive to RH.

Taken together, the models exhibit much greater divergence in their responses to anion perturbations than to cation perturbations, highlighting substantial uncertainties in thermodynamic predictions of under varying aerosol particle phase chemical profile. Notably, E-AIM shows the highest sensitivity to chemical profiles, in terms of both anions and cations (see Table S3).

3.2.3 Relative importance of meteorological condition vs. chemical profile

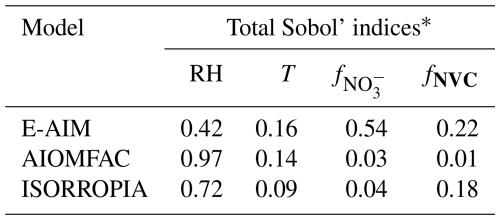

To examine the overall relative importance of meteorological condition and chemical profile on , we adopted the Sobol's variance decomposition method (Feinberg et al., 2020; Ji et al., 2018). This method is a global sensitivity analysis approach that partitions the variance of a model output into contributions from individual input factors and their interactions, thereby quantifying how much each factor and their combinations influence the output variability and thus determining their relative importance within a given model. Note that Sobol's variance decomposition method requires all input variables must be statistically independent of each other (see Fig. S9). Therefore, we selected the key parameters of RH and temperature, and fNVC to represent the meteorological conditions and chemical profiles, respectively.

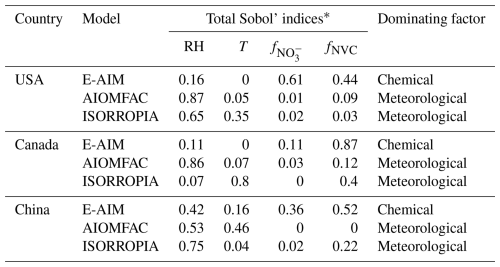

The results show that for AIOMFAC and ISORROPIA, variations are largely regulated by RH rather than chemical profile (see Table 1). In comparison, for E-AIM the is more sensitive to chemical profiles than meteorology. Especially, E-AIM show the largest sensitivity to the anion profiles , which is consistent with the results presented in Fig. 4a, d.

Table 1Sobol's variance decomposition of different factors based on Scenario Full.

* Total Sobol' indices are used in global sensitivity analysis to quantify the contribution of an input variable and its interaction effects with other variables to the total variance of the model output.

We also note that while E-AIM is less sensitive to metrological conditions than to chemical profile, its absolute sensitivity to meteorological factor is still comparable to ISORROPIA and substantially higher than that of AIOMFAC, especially in terms of temperature (Sect. 4.1; Fig. 3a–c) (Pye et al., 2020). As E-AIM is typically treated as the benchmark model, these results implies that the ISORROPIA could roughly capture the influence of meteorological conditions on , while its representation on the influence of chemical profiles is not enough. In comparison, the AIOMFAC needs to be improved in the considerations of both meteorological conditions and chemical profiles.

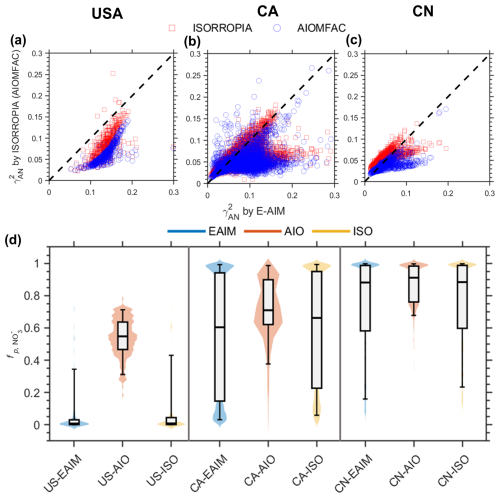

3.3 Dominant influencing factors for ambient aerosols

The dependences of to different influencing factors as estimated by the three thermodynamic models are further evaluated with ambient observations worldwide. Overall, the range from 0.008 to 0.3 (see Fig. 5). The as predicted with E-AIM are generally higher than the other two models, in agreement with the results from the simulation data (Fig. 2a, b). Consequently, E-AIM estimates a lower than the other two models (see Fig. 5d). AIOMFAC occasionally yields values outside the physically valid range of 0–1 (< 2 %), indicating that further improvements are needed in the current version of AIOMFAC for reliable gas–particle partitioning predictions. However, none of them are in good alignment with observational , and larger underestimation is often seen in lower ambient range (see Fig. S10). This may also be partially attributed to the uncertainties of measured , including sampling artifacts associated with semi-volatile ammonium nitrate, potential volatilization losses during filter-based measurements, temporal mismatches between gas-phase HNO3 and particulate NO observations, etc. These effects can be particularly pronounced under low total nitrate (NO HNO3) conditions, where small absolute errors in nitrate or nitric acid measurements may translate into large uncertainties in (Guo et al., 2016; Tao and Murphy, 2019). Future studies should therefore focus on narrowing these discrepancies through coordinated improvements in both measurement and model. On the measurement side, the use of online or semi-continuous techniques, together with collocated and time-resolved observations of gas-phase HNO3 and particulate NO, would help reduce uncertainties associated with sampling artifacts and temporal mismatches. On the modelling side, the variability of , especially at low nitrate levels, may be better captured by considering potential kinetic limitations and by improving the parameterization of activity coefficients in inorganic-organic mixed aerosol system. Observation-constrained modeling, together with sensitivity analyses, can further reduce discrepancies in between modelled and observed values.

Figure 5Estimation of (a–c), (d) from three thermodynamic models, based on global observational data. The (a) left, (b) middle, and (c) right panels correspond to the USA, Canada (CA), and China (CN), respectively. Violin-box plots of simulated by three thermodynamic models (EAIM, AIOMFAC, ISORROPIA) under three regions (USA, CA, CN). The shaded violin background indicates the probability density of the data distribution. The boxes and whiskers indicate the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles, respectively.

Sobol's variance decomposition analysis corroborates the simulation findings, indicating that chemical profiles are the primary controlling factor in E-AIM, whereas meteorological conditions play a more significant role in ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC (see Table 2). Furthermore, the relative influence of anions versus cations varies with location. As can be seen from E-AIM results, while anion profiles exert a stronger effect in the USA, cation profiles are more dominant in Canada and China. These results reveal that the controlling factors for are model-dependent and location-specific.

Our results show significant differences of and estimation among three widely-used thermodynamic models, i.e. ISORROPIA, E-AIM, and AIOMFAC. While the E-AIM is typically considered as the benchmark, ISORROPIA is more widely adopted in 3-D chemical-transport models, whereas AIOMFAC is preferred in dealing with organic-related processes. The large difference among these models indicate that model choice can substantially influence the predicted particle-phase activity coefficient and nitrate partitioning, which may bring non-negligible uncertainties and can be important in explaining the gaps among observations, chamber studies and large-scale model simulations.

While all three models show strong dependence of on RH, their estimation of the dependence on chemical profiles differed much. Especially, while for E-AIM the is more sensitive to chemical profiles, for ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC the meteorological conditions play the major role. These results indicate the needs for improved consideration of chemical profiles in estimations, especially for ISORROPIA and AIOMFAC. More chamber and ambient observations, as well as theoretical calculations are encouraged in future studies to derive a unified and comprehensive picture, and therefore to improve the accuracy of aerosol thermodynamic predictions and better inform air quality and climate assessments.

Data are available on request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-26-1795-2026-supplement.

Wan Ruilin: Software, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Zheng Guangjie: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration. Li Yuyang and Duan Xiaolin: Validation, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing. Jiang Jingkun and He Kebin: Supervision, Project administration, Writing – Review & Editing.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22476106 and 22188102).

This paper was edited by Zhibin Wang and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Arangio, A. M., Shahpoury, P., Dabek-Zlotorzynska, E., and Nenes, A.: Seasonal Aerosol Acidity, Liquid Water Content and Their Impact on Fine Urban Aerosol in SE Canada, Atmosphere, 13, 1012, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13071012, 2022.

Atkins, P. W., De Paula, J., and Keeler, J.: Atkins' physical chemistry, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-876986-6, 2023.

Bromley, L. A.: Thermodynamic properties of strong electrolytes in aqueous solutions, AIChE Journal, 19, 313–320, https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690190216, 1973.

Cao, Y., Ma, Q., Chu, B., and He, H.: Homogeneous and heterogeneous photolysis of nitrate in the atmosphere: state of the science, current research needs, and future prospects, Front. Environ. Sci. Eng., 17, 48, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-023-1648-6, 2023.

Carslaw, K. S., Clegg, S. L., and Brimblecombe, P.: A Thermodynamic Model of the System HCl-HNO3-H2SO4-H2O, Including Solubilities of HBr, from < 200 to 328 K, J. Phys. Chem., 99, 11557–11574, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100029a039, 1995.

Clegg, S. L. and Brimblecombe, Peter.: Equilibrium partial pressures and mean activity and osmotic coefficients of 0–100 % nitric acid as a function of temperature, J. Phys. Chem., 94, 5369–5380, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100376a038, 1990.

Clegg, S. L., Pitzer, K. S., and Brimblecombe, P.: Thermodynamics of multicomponent, miscible, ionic solutions. Mixtures including unsymmetrical electrolytes, J. Phys. Chem., 96, 9470–9479, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100202a074, 1992.

Clegg, S. L., Brimblecombe, P., and Wexler, A. S.: Thermodynamic Model of the System H+-NH-Na+-SO-NO-Cl−-H2 O at 298.15 K, J. Phys. Chem. A, 102, 2155–2171, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp973043j, 1998a.

Clegg, S. L., Brimblecombe, P., and Wexler, A. S.: Thermodynamic Model of the System H+-NH-SO-NO-H2 O at Tropospheric Temperatures, J. Phys. Chem. A, 102, 2137–2154, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp973042r, 1998b.

Clegg, S. L., Kleeman, M. J., Griffin, R. J., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Effects of uncertainties in the thermodynamic properties of aerosol components in an air quality model – Part 1: Treatment of inorganic electrolytes and organic compounds in the condensed phase, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 1057–1085, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-1057-2008, 2008.

Duan, X., Zheng, G., Chen, C., Zhang, Q., and He, K.: Driving factors of aerosol acidity: a new hierarchical quantitative analysis framework and its application in Changzhou, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 3919–3928, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-3919-2025, 2025.

Edgerton, E. S., Hartsell, B. E., Saylor, R. D., Jansen, J. J., Hansen, D. A., and Hidy, G. M.: The Southeastern Aerosol Research and Characterization Study, Part 3: Continuous Measurements of Fine Particulate Matter Mass and Composition, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 56, 1325–1341, https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2006.10464585, 2006.

Feinberg, A., Maliki, M., Stenke, A., Sudret, B., Peter, T., and Winkel, L. H. E.: Mapping the drivers of uncertainty in atmospheric selenium deposition with global sensitivity analysis, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 1363–1390, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-1363-2020, 2020.

Fountoukis, C. and Nenes, A.: ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+–Ca2+–Mg2+–NH–Na+–SO–NO–Cl−–H2O aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 4639–4659, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007, 2007.

Friese, E. and Ebel, A.: Temperature Dependent Thermodynamic Model of the System H+-NH-Na+-SO-NO-Cl−-H2 O, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 11595–11631, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp101041j, 2010.

Guo, H., Xu, L., Bougiatioti, A., Cerully, K. M., Capps, S. L., Hite Jr., J. R., Carlton, A. G., Lee, S.-H., Bergin, M. H., Ng, N. L., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine-particle water and pH in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5211–5228, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5211-2015, 2015.

Guo, H., Sullivan, A. P., Campuzano-Jost, P., Schroder, J. C., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Dibb, J. E., Jimenez, J. L., Thornton, J. A., Brown, S. S., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine particle pH and the partitioning of nitric acid during winter in the northeastern United States, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 121, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025311, 2016.

Guo, H., Liu, J., Froyd, K. D., Roberts, J. M., Veres, P. R., Hayes, P. L., Jimenez, J. L., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine particle pH and gas–particle phase partitioning of inorganic species in Pasadena, California, during the 2010 CalNex campaign, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 5703–5719, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-5703-2017, 2017a.

Guo, H., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: High levels of ammonia do not raise fine particle pH sufficiently to yield nitrogen oxide-dominated sulfate production, Sci. Rep., 7, 12109, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11704-0, 2017b.

Hansen, D. A., Edgerton, E. S., Hartsell, B. E., Jansen, J. J., Kandasamy, N., Hidy, G. M., and Blanchard, C. L.: The Southeastern Aerosol Research and Characterization Study: Part 1 – Overview, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 53, 1460–1471, https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2003.10466318, 2003.

Hennigan, C. J., Izumi, J., Sullivan, A. P., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: A critical evaluation of proxy methods used to estimate the acidity of atmospheric particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2775–2790, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2775-2015, 2015.

Hull, T., D'Aronco, S., Crumeyrolle, S., Hanoune, B., Giammanco, S., La Spina, A., Salerno, G., Soldà, L., Badocco, D., Pastore, P., Sellitto, P., and Giorio, C.: Metal speciation of volcanic aerosols from Mt. Etna at varying aerosol water content and pH obtained by different thermodynamic models, Environ. Sci. Atmos., 5, 8–24, https://doi.org/10.1039/D4EA00108G, 2025.

Ji, D., Dong, W., Hong, T., Dai, T., Zheng, Z., Yang, S., and Zhu, X.: Assessing Parameter Importance of the Weather Research and Forecasting Model Based On Global Sensitivity Analysis Methods, JGR Atmospheres, 123, 4443–4460, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JD027348, 2018.

Li, H., Cheng, J., Zhang, Q., Zheng, B., Zhang, Y., Zheng, G., and He, K.: Rapid transition in winter aerosol composition in Beijing from 2014 to 2017: response to clean air actions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 11485–11499, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-11485-2019, 2019.

Li, M., Su, H., Zheng, G., Kuhn, U., Kim, N., Li, G., Ma, N., Pöschl, U., and Cheng, Y.: Aerosol pH and Ion Activities of HSO and SO in Supersaturated Single Droplets, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 12863–12872, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c01378, 2022.

Li, Y., Li, X., Cai, R., Yan, C., Zheng, G., Li, Y., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., Hua, C., Kerminen, V.-M., Liu, Y., Kulmala, M., Hao, J., Smith, J. N., and Jiang, J.: The Significant Role of New Particle Composition and Morphology on the HNO3 -Driven Growth of Particles down to Sub-10 nm, Environ. Sci. Technol., 58, 5442–5452, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c09454, 2024.

Li, Z., Xu, W., Zhou, W., Lei, L., Sun, J., You, B., Wang, Z., and Sun, Y.: Insights into the compositional differences of PM1 and PM2.5 from aerosol mass spectrometer measurements in Beijing, China, Atmospheric Environment, 301, 119709, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119709, 2023.

Liu, M., Song, Y., Zhou, T., Xu, Z., Yan, C., Zheng, M., Wu, Z., Hu, M., Wu, Y., and Zhu, T.: Fine particle pH during severe haze episodes in northern China, Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 5213–5221, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073210, 2017.

Liu, M., Liu, Z., Wang, J., Chen, W., Feng, T., Pan, T., Yuan, B., Huang, S., Shao, M., Hu, M., Wang, X., and Hu, W.: The Variation, Source, and Environmental Impact of Chloride Across China: Summarized Field Results Based on the Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (AMS), JGR Atmospheres, 130, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024jd043275, 2025.

Mezuman, K., Bauer, S. E., and Tsigaridis, K.: Evaluating secondary inorganic aerosols in three dimensions, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 10651–10669, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-10651-2016, 2016.

Nault, B. A., Campuzano-Jost, P., Day, D. A., Jo, D. S., Schroder, J. C., Allen, H. M., Bahreini, R., Bian, H., Blake, D. R., Chin, M., Clegg, S. L., Colarco, P. R., Crounse, J. D., Cubison, M. J., DeCarlo, P. F., Dibb, J. E., Diskin, G. S., Hodzic, A., Hu, W., Katich, J. M., Kim, M. J., Kodros, J. K., Kupc, A., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Marais, E. A., Middlebrook, A. M., Andrew Neuman, J., Nowak, J. B., Palm, B. B., Paulot, F., Pierce, J. R., Schill, G. P., Scheuer, E., Thornton, J. A., Tsigaridis, K., Wennberg, P. O., Williamson, C. J., and Jimenez, J. L.: Chemical transport models often underestimate inorganic aerosol acidity in remote regions of the atmosphere, Commun Earth Environ, 2, 93, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00164-0, 2021.

Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., and Pilinis, C.: ISORROPIA: A New Thermodynamic Equilibrium Model for Multiphase Multicomponent Inorganic Aerosols, Aquatic Geochemistry, 4, 123–152, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009604003981, 1998.

Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., Weber, R. J., and Russell, A.: Aerosol pH and liquid water content determine when particulate matter is sensitive to ammonia and nitrate availability, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 3249–3258, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-3249-2020, 2020.

Nenes, A., Pandis, S. N., Kanakidou, M., Russell, A. G., Song, S., Vasilakos, P., and Weber, R. J.: Aerosol acidity and liquid water content regulate the dry deposition of inorganic reactive nitrogen, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 6023–6033, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-6023-2021, 2021.

Norman, O. G., Heald, C. L., Bililign, S., Campuzano-Jost, P., Coe, H., Fiddler, M. N., Green, J. R., Jimenez, J. L., Kaiser, K., Liao, J., Middlebrook, A. M., Nault, B. A., Nowak, J. B., Schneider, J., and Welti, A.: Exploring the processes controlling secondary inorganic aerosol: evaluating the global GEOS-Chem simulation using a suite of aircraft campaigns, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 25, 771–795, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-771-2025, 2025.

Nowak, J. B., Neuman, J. A., Bahreini, R., Brock, C. A., Middlebrook, A. M., Wollny, A. G., Holloway, J. S., Peischl, J., Ryerson, T. B., and Fehsenfeld, F. C.: Airborne observations of ammonia and ammonium nitrate formation over Houston, Texas, J. Geophys. Res., 115, 2010JD014195, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD014195, 2010.

Pan, D., Mauzerall, D. L., Wang, R., Guo, X., Puchalski, M., Guo, Y., Song, S., Tong, D., Sullivan, A. P., Schichtel, B. A., Collett, J. L., and Zondlo, M. A.: Regime shift in secondary inorganic aerosol formation and nitrogen deposition in the rural United States, Nat. Geosci., 17, 617–623, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01455-9, 2024.

Parworth, C. L., Young, D. E., Kim, H., Zhang, X., Cappa, C. D., Collier, S., and Zhang, Q.: Wintertime water-soluble aerosol composition and particle water content in Fresno, California, JGR Atmospheres, 122, 3155–3170, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016jd026173, 2017.

Pathak, R. K., Wu, W. S., and Wang, T.: Summertime PM2.5 ionic species in four major cities of China: nitrate formation in an ammonia-deficient atmosphere, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 1711–1722, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1711-2009, 2009.

Peng, X., Vasilakos, P., Nenes, A., Shi, G., Qian, Y., Shi, X., Xiao, Z., Chen, K., Feng, Y., and Russell, A. G.: Detailed Analysis of Estimated pH, Activity Coefficients, and Ion Concentrations between the Three Aerosol Thermodynamic Models, Environ. Sci. Technol., 53, 8903–8913, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b00181, 2019.

Pitzer, K. S.: Chapter 4. A THERMODYNAMIC MODEL FOR AQUEOUS SOLUTIONS OF LIQUID-LIKE DENSITY, Thermodynamic Modeling of Geologic Materials: Minerals, Fluids, and Melts, edited by: Carmichael, I. S. E. and Eugster, H., Berlin, De Gruyter, Boston, 97–142, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501508950-006, 1987.

Pitzer, K. S. and Simonson, J. M.: Thermodynamics of multicomponent, miscible, ionic systems: theory and equations, J. Phys. Chem., 90, 3005–3009, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100404a042, 1986.

Pye, H. O. T., Zuend, A., Fry, J. L., Isaacman-VanWertz, G., Capps, S. L., Appel, K. W., Foroutan, H., Xu, L., Ng, N. L., and Goldstein, A. H.: Coupling of organic and inorganic aerosol systems and the effect on gas–particle partitioning in the southeastern US, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 357–370, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-357-2018, 2018.

Pye, H. O. T., Nenes, A., Alexander, B., Ault, A. P., Barth, M. C., Clegg, S. L., Collett Jr., J. L., Fahey, K. M., Hennigan, C. J., Herrmann, H., Kanakidou, M., Kelly, J. T., Ku, I.-T., McNeill, V. F., Riemer, N., Schaefer, T., Shi, G., Tilgner, A., Walker, J. T., Wang, T., Weber, R., Xing, J., Zaveri, R. A., and Zuend, A.: The acidity of atmospheric particles and clouds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 4809–4888, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-4809-2020, 2020.

Qi, L., Zheng, H., Ding, D., and Wang, S.: Responses of sulfate and nitrate to anthropogenic emission changes in eastern China – in perspective of long-term variations, Science of The Total Environment, 855, 158875, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158875, 2023.

Seinfeld, J. H. and Pandis, S. N.: Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, ISBN 978-1-118-94740-1, 2016.

Shi, Q., Tao, Y., Krechmer, J. E., Heald, C. L., Murphy, J. G., Kroll, J. H., and Ye, Q.: Laboratory Investigation of Renoxification from the Photolysis of Inorganic Particulate Nitrate, Environ. Sci. Technol., 55, 854–861, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c06049, 2021.

Song, S., Gao, M., Xu, W., Shao, J., Shi, G., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., and McElroy, M. B.: Fine-particle pH for Beijing winter haze as inferred from different thermodynamic equilibrium models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7423–7438, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7423-2018, 2018.

Tan, H., Cai, M., Fan, Q., Liu, L., Li, F., Chan, P. W., Deng, X., and Wu, D.: An analysis of aerosol liquid water content and related impact factors in Pearl River Delta, Science of The Total Environment, 579, 1822–1830, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.167, 2017.

Tao, Y. and Murphy, J. G.: The sensitivity of PM2.5 acidity to meteorological parameters and chemical composition changes: 10-year records from six Canadian monitoring sites, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 9309–9320, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-9309-2019, 2019.

Wang, D., Shen, Z., Yang, X., Huang, S., Luo, Y., Bai, G., and Cao, J.: Insight into the Role of NH3/NH and NOx/NO in the Formation of Nitrogen-Containing Brown Carbon in Chinese Megacities, Environ. Sci. Technol., https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c10374, 2024.

Wang, M., Xiao, M., Bertozzi, B., Marie, G., Rörup, B., Schulze, B., Bardakov, R., He, X.-C., Shen, J., Scholz, W., Marten, R., Dada, L., Baalbaki, R., Lopez, B., Lamkaddam, H., Manninen, H. E., Amorim, A., Ataei, F., Bogert, P., Brasseur, Z., Caudillo, L., De Menezes, L.-P., Duplissy, J., Ekman, A. M. L., Finkenzeller, H., Carracedo, L. G., Granzin, M., Guida, R., Heinritzi, M., Hofbauer, V., Höhler, K., Korhonen, K., Krechmer, J. E., Kürten, A., Lehtipalo, K., Mahfouz, N. G. A., Makhmutov, V., Massabò, D., Mathot, S., Mauldin, R. L., Mentler, B., Müller, T., Onnela, A., Petäjä, T., Philippov, M., Piedehierro, A. A., Pozzer, A., Ranjithkumar, A., Schervish, M., Schobesberger, S., Simon, M., Stozhkov, Y., Tomé, A., Umo, N. S., Vogel, F., Wagner, R., Wang, D. S., Weber, S. K., Welti, A., Wu, Y., Zauner-Wieczorek, M., Sipilä, M., Winkler, P. M., Hansel, A., Baltensperger, U., Kulmala, M., Flagan, R. C., Curtius, J., Riipinen, I., Gordon, H., Lelieveld, J., El-Haddad, I., Volkamer, R., Worsnop, D. R., Christoudias, T., Kirkby, J., Möhler, O., and Donahue, N. M.: Synergistic HNO3–H2SO4–NH3 upper tropospheric particle formation, Nature, 605, 483–489, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04605-4, 2022.

Weber, R. J., Guo, H., Russell, A. G., and Nenes, A.: High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years, Nat. Geosci., 9, 282–285, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2665, 2016.

Wexler, A. S. and Clegg, S. L.: Atmospheric aerosol models for systems including the ions H+, NH, Na+, SO, NO, Cl−, Br−, and H2 O, J.-Geophys.-Res., 107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JD000451, 2002.

Xu, Q., Wang, S., Jiang, J., Bhattarai, N., Li, X., Chang, X., Qiu, X., Zheng, M., Hua, Y., and Hao, J.: Nitrate dominates the chemical composition of PM2.5 during haze event in Beijing, China, Science of The Total Environment, 689, 1293–1303, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.294, 2019.

Yao, X., Yan Ling, T., Fang, M., and Chan, C. K.: Comparison of thermodynamic predictions for in situ pH in PM2.5, Atmospheric Environment, 40, 2835–2844, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.01.006, 2006.

Ye, C., Zhang, N., Gao, H., and Zhou, X.: Photolysis of Particulate Nitrate as a Source of HONO and NOx, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 6849–6856, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00387, 2017.

Zhai, S., Jacob, D. J., Wang, X., Liu, Z., Wen, T., Shah, V., Li, K., Moch, J. M., Bates, K. H., Song, S., Shen, L., Zhang, Y., Luo, G., Yu, F., Sun, Y., Wang, L., Qi, M., Tao, J., Gui, K., Xu, H., Zhang, Q., Zhao, T., Wang, Y., Lee, H. C., Choi, H., and Liao, H.: Control of particulate nitrate air pollution in China, Nat. Geosci., 14, 389–395, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00726-z, 2021.

Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Ma, W., Hua, C., Zheng, F., Lian, C., Wang, W., Xia, M., Zhao, Z., Li, J., Xie, J., Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Chen, X., Zhang, Y., Feng, Z., Yan, C., Chu, B., Du, W., Kerminen, V.-M., Bianchi, F., Petäjä, T., Worsnop, D., and Kulmala, M.: Changing aerosol chemistry is redefining HONO sources, Nat. Commun., 16, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60614-7, 2025.

Zheng, G., Su, H., Wang, S., Pozzer, A., and Cheng, Y.: Impact of non-ideality on reconstructing spatial and temporal variations in aerosol acidity with multiphase buffer theory, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 47–63, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-47-2022, 2022.

Zuend, A., Marcolli, C., Luo, B. P., and Peter, T.: A thermodynamic model of mixed organic-inorganic aerosols to predict activity coefficients, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 4559–4593, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-4559-2008, 2008.

Zuend, A., Marcolli, C., Peter, T., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Computation of liquid-liquid equilibria and phase stabilities: implications for RH-dependent gas/particle partitioning of organic-inorganic aerosols, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10, 7795–7820, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-10-7795-2010, 2010.

Zuend, A., Marcolli, C., Booth, A. M., Lienhard, D. M., Soonsin, V., Krieger, U. K., Topping, D. O., McFiggans, G., Peter, T., and Seinfeld, J. H.: New and extended parameterization of the thermodynamic model AIOMFAC: calculation of activity coefficients for organic-inorganic mixtures containing carboxyl, hydroxyl, carbonyl, ether, ester, alkenyl, alkyl, and aromatic functional groups, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 9155–9206, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-9155-2011, 2011.

Zünd, A.: Modelling the thermodynamics of mixed organic-inorganic aerosols to predict water activities and phase separations, ETH Zurich, https://doi.org/10.3929/ETHZ-A-005582922, 2007.