the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Terrestrial runoff is an important source of biological ice-nucleating particles in Arctic marine systems

Corina Wieber

Lasse Z. Jensen

Leendert Vergeynst

Lorenz Meire

Thomas Juul-Pedersen

Kai Finster

The accelerated warming of the Arctic manifests in sea ice loss and melting glaciers, significantly altering the dynamics of marine biota. This disruption in marine ecosystems can lead to an increased emission of biological ice-nucleating particles (INPs) from the ocean into the atmosphere. Once airborne, these INPs induce cloud droplet freezing, thereby affecting cloud lifetime and radiative properties. Despite the potential atmospheric impacts of marine INPs, their properties and sources remain poorly understood. By analyzing sea bulk water and the sea surface microlayer in two southwest Greenlandic fjords, collected between June and September 2018, and investigating the INPs along with the microbial communities, we could demonstrate a clear seasonal variation in the number of INPs and a notable input from terrestrial runoff. We found the highest INP concentration in June during the late stage of the phytoplankton bloom and active melting processes causing enhanced terrestrial runoff. These highly active INPs were smaller in size and less heat-sensitive than those found later in the summer and those previously identified in Arctic marine systems. A negative correlation between salinity and INP abundance suggests freshwater input as a source of INPs. Stable oxygen isotope analysis, along with the strong correlation between INPs and the presence of terrestrial and freshwater bacteria such as Aquaspirillum arcticum, Rhodoferax, and Glaciimonas, highlighted meteoric water as the primary origin of the freshwater influx, suggesting that the notably active INPs originate from terrestrial sources such as glacial and soil runoff.

- Article

(2805 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1271 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Climate change manifests in a steady rise in the global average temperature (IPCC, 2021a), and the Arctic region is particularly susceptible to its effects, experiencing a warming 4 times faster than the global average (Rantanen et al., 2022), a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification (Previdi et al., 2021). The consequences of the rise in temperature are severe, as it leads to significant alterations in the energy balance (Letterly et al., 2018), changes that are displayed in the loss of sea ice, glacial melt, and the thawing of permafrost (Previdi et al., 2021; Box et al., 2019; Chadburn et al., 2017). Enhanced melting processes, e.g., the melting of sea ice and glaciers, lead to a decline in the sea surface salinity (freshening) due to the freshwater input (Ravindran et al., 2021; Fransson et al., 2023). Further, the reduction in sea ice exposes a larger fraction of seawater to the atmosphere, which facilitates the exchange of gases and aerosols between the ocean and the atmosphere (Browse et al., 2014). The sea surface microlayer (SML), which is the interface between the ocean and the atmosphere with a thickness of less than a millimeter (Liss and Duce, 1997), plays a particularly important role in the ocean–atmosphere exchange (Cunliffe et al., 2013). In the SML, the concentration of organic material is often increased compared to the underlying sea bulk water (SBW) as surface-active compounds preferentially partition into the SML (Wurl et al., 2009). Previous studies have shown that the microbial community of the SML differs from the SBW just a few centimeters beneath the SML (Zäncker et al., 2018; Reunamo et al., 2011) and that specific bacterial taxa (e.g., Flavobacteriaceae and Cryomorphaceae) are enriched in the SML compared to the SBW (Zäncker et al., 2018). Atmospherically relevant compounds comprising ice-nucleating particles (INPs) have also been found to concentrate in the SML compared to the SBW (Wilson et al., 2015; Hartmann et al., 2021).

INPs are particles that initiate the freezing of water at temperatures higher than the temperature of homogeneous freezing (−38 °C) and are of particular importance in the atmosphere where they impact ice formation in clouds (Kanji et al., 2017). When aerosolized from the ground, INPs can namely be transported upwards where they trigger the freezing of cloud droplets and thus affect cloud radiative properties and lifetime. While mineral dust and soot are the numerically dominating atmospheric INPs at temperatures below −15 °C, biological INPs dominate at temperatures above −15 °C and as high as −2 °C (Maki et al., 1974; Vali et al., 1976; Murray et al., 2012). Cloud ice formation has been frequently observed in Arctic mixed-phase clouds at temperatures where only biological INPs are known to nucleate ice at atmospherically relevant concentrations (Griesche et al., 2021; Creamean et al., 2022). Therefore, there has recently been an increased focus on quantifying biological INPs in both source environments and the atmosphere in the Arctic (Hartmann et al., 2021; Šantl-Temkiv et al., 2019; Creamean et al., 2022; Pereira Freitas et al., 2023; Tobo et al., 2024). Especially during summer, when the long-range transport into the Arctic atmosphere is limited, locally sourced biological INPs may play an important role in cloud processes (Griesche et al., 2021). As cloud processes feed into the energy balance in the Arctic and therefore modulate Arctic amplification (Serreze and Barry, 2011; Tan and Storelvmo, 2019), there is a need to improve our understanding of the sources, controlling factors, and emission rates of cloud-relevant particles such as INPs.

Seawater, and in particular the SML, may act as a source of biological aerosols (bioaerosols) and INPs as wave breaking and bubble bursting can inject a significant amount of biological material and INPs into the atmosphere (Ickes et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2015). So far it is unknown which types of INPs are responsible for the ice nucleation activity in seawater, but the sources may be linked to indigenous processes performed by marine microorganisms or to external inputs of terrestrial material into marine systems. Therefore, both marine and terrestrial ice-nucleation-active (INA) organisms may play a role when it comes to marine emissions of INPs. There is also an interplay between these two factors, as terrestrial runoff of nutrients has been shown to enhance the activity of marine microbes (Arrigo et al., 2017). Biological INPs can stem from a variety of sources such as different bacterial (Joly et al., 2013; Maki et al., 1974; Šantl-Temkiv et al., 2015), microalgal (Tesson and Šantl-Temkiv, 2018), and fungal species (Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Kunert et al., 2019), as well as lichen (Eufemio et al., 2023; Kieft and Ruscetti, 1990), viruses (Adams et al., 2021), and pollen (Gute and Abbatt, 2020) and subpollen particles (Burkart et al., 2021), which inhabit marine and terrestrial environments. While we have substantial knowledge of bacterial ice nucleation proteins (Hartmann et al., 2022; Roeters et al., 2021; Garnham et al., 2011; Govindarajan and Lindow, 1988), our understanding of INA material excreted by other microorganisms, i.e., microalgae and fungi, is limited. In addition, the quantitative contribution of different biologically sourced INPs remains to be determined.

Recent studies have shown a correlation between biological INPs in Arctic seawater and the phytoplanktonic growth season (Creamean et al., 2019; Zeppenfeld et al., 2019). If the INPs originate from microorganisms associated with phytoplanktonic blooms, their impact on atmospheric processes could become more pronounced with ongoing climate change as, e.g., primary productivity is stimulated by higher temperatures and increased CO2 levels. In addition, the melting of sea ice prolongs the phytoplankton growth season due to increased penetration of shortwave radiation into the water column (Park et al., 2015). This leads to more planktonic biomass and affects the marine ecosystem. Arrigo et al. (2008) observed an increase in annual primary production by marine algae of 35 Tg C yr−1 between 2006 and 2007 due to decreasing sea ice coverage and a longer phytoplankton growth season. Consequently, the increased primary production induced by warming could impact the number of biogenic INPs released from the seawater and their effect on atmospheric processes. Further, terrestrial ice melt and runoff have been increasing over time (IPCC, 2021b). Studies have shown that glacial outwash sediment (Tobo et al., 2019; Xi et al., 2022), rivers (Knackstedt et al., 2018), thawing permafrost, and thermokarst lakes (Creamean et al., 2020; Barry et al., 2023) contain high concentrations of INPs active at high sub-zero temperatures. As the runoff processes are enhanced, this will lead to increased inputs of highly active terrestrial INPs into the marine environments. Due to our poor understanding of biological INPs found in marine environments, it remains unclear whether it is indigenous microbial processes or external inputs that dominate the pool of INPs in seawater.

Although prior studies have examined the concentrations of INPs in both SBW and the SML, along with the influence of phytoplankton blooms on atmospheric INPs and INP concentrations in bulk water, the complete understanding of the dynamics and origins of marine INPs remains elusive. Hence, our research delved into the concentrations and properties of INPs within both the SBW and the SML of southwest Greenland during the late-bloom and post-bloom seasons. We chose to work on fjord systems to address the roles of indigenous processes versus external inputs such as terrestrial runoff or sea ice meltwater as fjords are semi-closed systems where water circulation and therefore dilution of freshwater inputs are restricted. We correlated INP concentrations with chlorophyll a alongside the assessments of microbial composition, diversity, and abundance to understand whether INPs are linked to the abundance of specific microbes, indicating either their indigenous production or their acting as tracers for their source environments. Finally, we correlated INP concentrations with salinity and δO18 analysis to pinpoint the contribution of terrestrial inputs to the marine INP pool. This holistic approach aims to enhance our understanding of the dynamics and characteristics of biological marine INPs in the low Arctic.

2.1 Sample collection

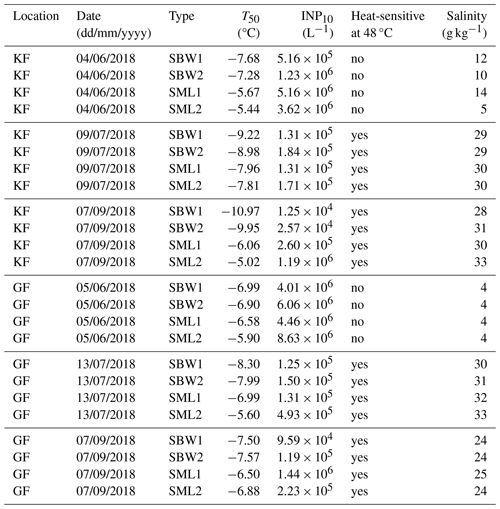

SML and SBW samples were collected at Kobbefjord (KF; 64°09.228 N, 51°25.906 W) and Godthåbsfjord (GF; 64°20.794 N, 51°42.709 W) in southwest Greenland (Fig. 1) in June, July, and September 2018. Approximately 100 mL of the SML was collected per sample using a glass plate sampler (Harvey and Burzell, 1972). The glass plate sampler was immersed vertically and retracted at approximately 5 cm s−1. The seawater was allowed to run off before the adherent SML samples were scraped into a sterile bottle using a neoprene wiper. SBW samples were collected simultaneously by lowering a sterile bottle approximately 1 m below the SML. Care was taken that the bottle was opened below the SML and closed before retrieving it back onto the boat. Samples for microbial community analysis were immediately mixed 1:1 with a high-salt solution containing 25 mM sodium citrate, 10 mM EDTA, 450 g L−1 ammonium sulfate, and pH 5.2 (Lever et al., 2015) for the preservation of RNA. The samples were taken back to the lab immediately after sampling where they were concentrated onto Sterivex filters (0.22 µm), fixed in the presence of 1 mL of RNA later (Sigma Aldrich, US), and frozen at −20 °C until the analysis.

Figure 1Map of Greenland with a zoomed-in view of the region around Nuuk. The sampling stations for SBW and SML samples Kobbefjord and Godthåbsfjord are indicated by purple double stars. Further, the two stations for the chlorophyll and nutrient measurements GF3 and the mooring station are indicated by orange single stars. The map was produced in QGIS using the publicly available © Google Maps Satellite data layer.

2.2 Measurement of ice nucleation activity

Ice nucleation analysis was conducted using the micro-PINGUIN instrument (Wieber et al., 2024a). Micro-PINGUIN is an instrument that allows for droplet freezing assays using 384-well PCR plates. To ensure optimal thermal contact between the PCR plate and the cooling unit, a gallium bath is heated to 40 °C, and the PCR plate is immersed in the liquid gallium. The instrument is then cooled to 10 °C until the gallium solidifies, creating effective contact between the PCR plate and the surrounding cooling unit. Once the plate is mounted, the samples are added to the wells to prevent sample heating during the melting process of the gallium, which could negatively impact the ice-nucleating activity. For each sample, 80 wells of the 384-well PCR plates were filled with 30 µL of the sample each using an automatic 8-channel pipette (PIPETMAN P300, Gilson, US). The remaining 64 wells were filled with Milli-Q water filtered through a 0.22 µm PES filter, serving as a negative control. The system is then cooled at a rate of 1 °C min−1 until reaching −30 °C, while the freezing processes are recorded by an infrared camera (FLIR A655sc/25° Lens; Teledyne FLIR, US). Thereafter, the number of INPs per liter of sample n(T) is calculated as

where Nf(T) is the number of frozen droplets, N0 is the total number of droplets, and V is the sample volume.

The salt concentration for each sample was measured using a refractometer (WZ201, Frederiksen Scientific, Denmark), and the freezing curves were corrected for the freezing point depression ΔTf using the theoretical formula for sodium chloride solutions:

where c is the molarity of the salt, n is the number of ions of the dissociated salt (n= 2 for NaCl), and Ef is the cryoscopic constant of water (Schwidetzky et al., 2021). The contribution of other components such as sulfate, magnesium, and calcium to the freezing point depression was considered minor and therefore neglected. For the ice nucleation measurements, 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared using autoclaved sodium chloride solutions closest to the salinity of the original seawater samples (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, or 35 g kg−1).

2.2.1 Heat treatment of the INP samples

Heat treatments were performed using a water bath. Following the initial ice nucleation test, PCR plates from the ice nucleation assay were covered with adhesive plastic foil to prevent cross-contamination of the samples during removal as well as evaporation of water during the heat treatment. The plates were then placed in a preheated water bath at 48 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the plastic foil was removed, and ice nucleation activity was measured. The heat treatment was repeated the same way at 88 °C for 30 min, and ice nucleation activity was remeasured a final time. The heating temperatures were chosen based on the available literature on the heat stability of INPs to distinguish between different types of INPs. Bacterial INPs typically denature at temperatures above 40 °C (Pouleur et al., 1992; Hara et al., 2016); in contrast, INPs from fungal spores and lichen have been shown to remain heat-stable up to 60 °C (Pouleur et al., 1992; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Kieft and Ruscetti, 1990).

2.2.2 Filtration of the water samples

During the sampling campaign, filtrates for all samples were prepared with a 0.22 µm PES filter. Ice nucleation tests were conducted on all these samples. Selected samples (one of the duplicates) underwent a detailed investigation of ice nucleation activity across different size ranges. Thus, prefiltered samples were loaded into Vivaspin filters (Vivaspin 20, Sartorius, Germany) with molecular weight cut-offs (MWCOs) ranging from 1000 to 100 kDa. Prior to use, Vivaspin filters were prewashed with 5 mL of Milli-Q water to remove observed salt residues.

2.3 The fraction of meteoric water derived from stable oxygen isotopes

The fraction of stable oxygen isotopes δ18O can be used to determine the contributions of sea ice meltwater (SIM) and meteoric water (MW), originating from precipitation, e.g., rivers and glacial meltwater, within a sample. This approach has previously been used and proven valuable to distinguish between SIM and MW in the Arctic Ocean (Burgers et al., 2017; Irish et al., 2019; Alkire et al., 2015; Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2005). Following the approach used by Irish et al. (2019) and Burgers et al. (2017), the water volume fractions of sea ice meltwater (fSIM), meteoric water (fMW), and seawater (fSW) were calculated using the following equations:

where S is the corresponding salinity of the sample and δ18O the ratio between 18O and 16O in water molecules. These equations assume that each sample consists of sea ice meltwater, meteoric water, and a seawater reference and are derived from the conservation equations. Net sea ice formation results in negative fSIM values (Alkire et al., 2015). For the sea ice meltwater, we assume a salinity of 4 g kg−1 and a δ18O of 0.5 ‰ and for the meteoric water values of 0 g kg−1 and −20 ‰, respectively (Irish et al., 2019; Burgers et al., 2017). Further, we assume that our samples are mainly influenced by the west Greenland current waters, and thus we chose the values for the reference seawater as SSW= 33.5 g kg−1 and δ18OSW= −1.27 ‰ (Burgers et al., 2017). δ18O values were measured with Picarro L1102-i (18O). δ18O values correspond to the deviation from the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW) in per mill (‰). Measurements were calibrated using three internal reference water samples (−55.5 ‰, −33.4 ‰, and −8.72 ‰) and the average value of five to six replicate injections was taken for the calculations. Standard deviations between replicate measurements ranged between 0.004 ‰ and 0.12 ‰.

2.4 Nutrient and chlorophyll a concentrations

Nutrient concentrations were extracted from the database of the Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring (GEM) project (https://data.g-e-m.dk, last access: 10 November 2023). Measurements were carried out at the MarineBasis in Nuuk (location GF3 in Fig. 1). Nitrate and nitrite concentrations were measured by vanadium chloride reduction (Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring, 2020b), and phosphate (Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring, 2020a) and silicate (Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring, 2020c) concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically. Additionally, chlorophyll a measurements from 1 m depth were extracted from the GEM database. After collection, the seawater samples were filtered, and the filters were stored frozen in 10 mL 96 % ethanol until analysis with a Turner TD-700 fluorometer (TD-700, Turner Designs, US). The same method was applied for seawater sampled at 12 m depth in KF during the sampling dates of this study. For chlorophyll measurements from the mooring site (Fig. 1), a fluorescence sensor (Cyclops-7 Logger, PME, US) was deployed at 5 m depth from March to October 2018. The sensor was calibrated with chlorophyll standards (Turner Designs). To prevent biofouling, the instruments were wrapped with copper tape. Upon retrieval, data were read out and despiked using the OCE package (Kelley et al., 2022), and chlorophyll a concentrations were calculated as a 3 d average.

2.5 DNA extraction, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), and amplicon sequencing

As freezing of the Sterivex filters, containing the high-salt solution, lysed some microbial cells and thus released their nucleic acids (data not shown), we used two different protocols for DNA extraction, one for the DNA in solution and one for the DNA which was still within the intact cells on the filter. In brief, the high-salt solution was extracted from the Sterivex filter into a separate tube. Then, DNA was purified using the CleanAll RNA/DNA Clean-up and Concentration Micro Kit (Norgen Biotek) following the manufacturer's protocol. A combination of chemical and physical lysis was used on the Sterivex filters for simultaneous extraction of DNA as described by Lever et al. (2015). Last, the purified DNA from the Norgen Purification was pooled with the corresponding DNA from the Lever et al. (2015) extraction. qPCR was performed to quantify the number of bacterial 16S rRNA gene copies (DNA) as described earlier (Jensen et al., 2022), while 18S rRNA gene copies were quantified using primers Euk345F (5'-AAGGAAGGCAGCAGGCG-3') and Euk499R (5'-CACCAGACTTGCCCTCYAAT-3') (Zhu et al., 2005). The 16S rRNA library preparation of DNA was performed as described in Jensen et al. (2022). The 18S rRNA library preparation was performed with slight modification. Primers TareukFWD1 (5'-CCAGCASCYGCGGTAATTCC-3') and TAReukREV3 (5'-ACTTTCGTTCTTGATYRA-3') were used to amplify the V4 region of the small subunit (18S) ribosomal RNA, primarily targeting the marine microalgae (Stoeck et al., 2010). The PCR mixture contained 4 µL template DNA instead of 2 µL. The thermal cycling was run with a touchdown PCR approach with an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 min, for 10 cycles with denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s and then 15 cycles with denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 47 °C for 30 s, elongation at 72 °C, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR clean-up was performed as for the 16S rRNA PCR products. The second round of PCR was run for 10 cycles to incorporate overhang adapters and was run with the same conditions as the previous PCR with an annealing temperature of 57 °C. Products were cleaned, and the Nextera XT Index primers were incorporated in a third PCR reaction, which was run for eight cycles following the previous condition and an annealing temperature of 55 °C. The PCR products were quantified using a Quant-iT™ dsDNA BR assay kit on a FLUOstar Omega fluorometric microplate reader (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany), diluted, and pooled together in equimolar ratios. The pool was quantified using the Quant-iT™ dsDNA BR assay kit on a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA) and then sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA), which produces two 300 bp long paired-end reads.

2.6 Bioinformatic analysis

Bioinformatic analyses were performed in RStudio 4.3.3. The 16S and 18S sequence reads were processed following the same pipeline. Primer and adapter sequences were trimmed from the raw reads using cutadapt 0.0.1 (Martin, 2011). Forward and reverse read quality was plotted with the plotQualityProfile function from DADA2 1.21.0 (Callahan et al., 2016). Based on the read quality, a trimming of 280 and 200 bp was set for the forward and reverse reads, respectively, using filterAndTrim, according to their quality. The FASTQ files were randomly subsampled to the lowest read number using the ShortRead package 1.48.0 (Morgan et al., 2009), resulting in 42 375 reads per sample for the 16S and 63 555 reads per sample for the 18S, respectively. The subsampling allows for a more accurate comparison of the richness of the different samples. Error models were built for the forward and reverse reads, followed by dereplication and clustering into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) (Callahan et al., 2017) with DADA2. The denoised forward and reverse reads were merged using the function mergePairs with default parameters with a minimum overlap of 12 nucleotides, allowing zero mismatches. Sequence tables were made with the function makeSequenceTable. ASVs shorter than 401 and longer than 430 nucleotides were removed from the 16S, whereas sequences shorter than 360 and longer than 400 nucleotides were removed for the 18S dataset followed by chimeric sequence removal using the removeBimeraDenovo function. Taxonomic assignment was accomplished using the naive Bayesian classifier against the SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database v138 (Quast et al., 2012) for the 16S sequences, while the 18S sequences were classified against the Protist Ribosomal Reference (PR2) database v5.0.1 (Guillou et al., 2013) with the assignTaxonomy function from DADA2, and species assignment was performed with the assignSpecies function from DADA2. ASVs mapped to mitochondria, chloroplasts, and metazoa were removed from the dataset. Samples were decontaminated using the prevalence method (Threshold = 0.1) from the decontam package (Davis et al., 2018). Statistical tests and visualization of the data were performed with phyloseq (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013), vegan (Dixon, 2003), and microeco (Liu et al., 2021).

3.1 Spring bloom and secondary bloom in summer 2018

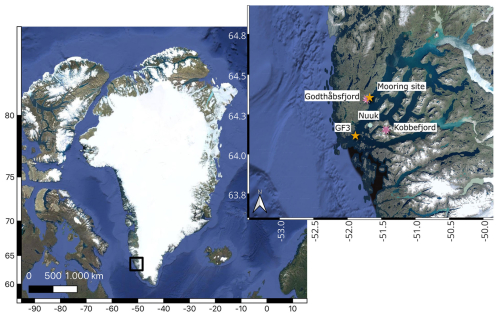

The chlorophyll a concentration, serving as a proxy for algal biomass (Creamean et al., 2019; Krawczyk et al., 2021; Huot et al., 2007; Hartmann et al., 2021), increased from early April to late May, with a brief decline at the end of April (Fig. 2a). In late August, there was a subsequent increase in chlorophyll a concentration lasting for 2 to 3 weeks. These periods of increased chlorophyll a concentration align closely with times of nutrient scarcity, particularly a reduction in silicate levels, indicating that the nutrients were likely consumed by phytoplankton, most probably diatoms (Fig. 2b) (Kröger and Poulsen, 2008; Mayzel et al., 2021). The abundance and composition of nutrients, specifically carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P), determine the activity and composition of the phytoplankton community (Arrigo, 2005). Increased primary production and chlorophyll a concentrations were previously shown to correlate with reduced nutrient concentrations such as nitrates (NO NO), silicate (SiO2), and phosphate (PO) (Juul-Pedersen et al., 2015). Low levels of these nutrients can limit phytoplankton growth (Harrison and Li, 2007). Silicate is a constituent of diatom cell walls and thus a limiting factor for diatom cell growth (Bidle and Azam, 1999). Based on this data, we conclude the occurrence of a spring bloom (beginning of April to June) followed by a shorter secondary bloom at the end of August in the Nuuk region in 2018.

Figure 2(a) Chlorophyll a concentration in 2018. Data were collected at three measurement sites, and data points for each site are connected by lines for visualization purposes. The green shaded area for the mooring site data shows the standard deviation for the 3 d average. (b) Silicate, nitrate and nitrite, and phosphate concentrations measured at location GF3 (Fig. 1) in 2018. Data points are connected by lines for visualization purposes, and the shaded areas indicate the standard deviations for measurements at 1, 5, 10, and 15 m depth. The sampling dates are highlighted by vertical dashed lines in both graphs.

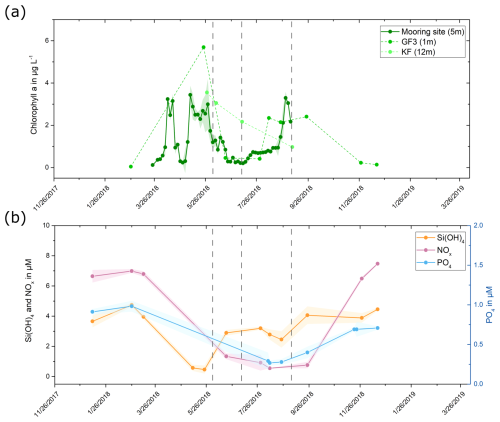

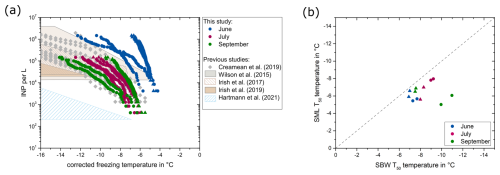

3.2 Seasonal variability in INP concentrations and higher T50 temperatures in the SML

While freezing was initiated above −7 °C in all investigated SBW samples (Fig. S1 in the Supplement), the concentration of INPs active at −10 °C (INP−10) covered a wide range from 1.3×104 INPs per liter to 6.1×106 INPs per liter (Fig. 3a). Typically, biological INPs are responsible for ice nucleation at temperatures higher than −15 °C (Murray et al., 2012), implying that the elevated onset freezing temperatures observed in our samples are attributable to INPs originating from biological sources. In addition, our study revealed higher T50 temperatures (temperature where 50 % of the droplets were frozen) in the SML compared to the corresponding SBW samples (Figs. 3b, S2), showing that the highly active INPs are primarily found in the SML, which may affect their emissions into the atmosphere through wave breaking and bubble bursting (Ickes et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2015). This finding aligns with observations by Wilson et al. (2015) and Hartmann et al. (2021), whereas Irish et al. (2017) observed no significant concentration of INPs in the SML compared to the SBW. This is unlikely to be related to the sampling technique as our study and the studies by Hartmann et al. (2021) and Wilson et al. (2015) observed a concentration of INPs in the SML despite utilizing different approaches for collecting the samples. Consequently, it is more plausible that these differences arise from spatial and temporal variations in the properties of the SML. Given that the SML serves as the interface between water and air, specific characteristics of INPs, such as hydrophobic sites, may lead to their partitioning into the SML. Moreover, elevated concentrations of organic material in the SML (Wurl et al., 2009) could provide energy for microorganisms in the SML and therefore lead to an increase in biogenic INP production, thereby explaining the higher INP concentrations observed in the SML.

Further, the ice nucleation tests revealed a seasonal variability, with INPs having the highest onset freezing temperatures and significantly higher INP−10 concentrations in June (Fig. S3). Notably, the INP concentrations in our study are generally higher than those reported by Wilson et al. (2015), Hartmann et al. (2021), and Irish et al. (2017). While INP concentrations for July and September fall well within the range observed by Irish et al. (2019) and Creamean et al. (2019), SBW samples in June exceed the previously reported INP concentrations and show higher onset freezing temperatures. Previous studies (Wilson et al., 2015; Irish et al., 2017; Irish et al., 2019; Creamean et al., 2019) utilized 0.6–2.5 µL droplets for ice nucleation analysis, resulting in a detection limit 12–50 times higher (assuming the same number of investigated droplets) than our method. Consequently, low-volume setups require higher concentrations of INPs for detection, thus not detecting highly active INPs that are typically present at lower concentrations. While small deviations in the reported freezing temperatures might occur due to methodological differences, INP concentrations in the two fjords observed in June are up to 4 orders of magnitude higher than previously reported values, implying that these differences are not for technical reasons.

We found a moderate significant correlation (r= 0.60, p= 0.038) between the concentration of INP−10 in the SBW from KF and GF and the in situ chlorophyll a concentration measured on the sampling dates in KF. The correlation was not significant (r= 0.79, p= 0.064) when focusing solely on the concentration of INP−10 in KF, where samples for quantifying chlorophyll a and INP were collected at the same location and time (Fig. S4). These observed correlations could either be explained by processes related to microalgal activity or result from a spurious correlation. INPs in June may originate from algal exudates released during the decay of phytoplankton in the late stage of the bloom or from the bloom-associated heterotrophic bacterial community. Factors such as nutrient limitation (Nagata, 2000), the transition between different growth stages (Wetz and Wheeler, 2007), cell death, cell lysis, and excretion can enhance the release of dissolved organic matter (DOM) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) by phytoplankton potentially including INA material (Thornton, 2014; Norrman et al., 1995; Thornton et al., 2023). Aside from containing INA material (Ickes et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2015), the released organics may also serve as nutrients for heterotrophic producers of INA material and may affect marine INP concentrations by shaping the heterotrophic community composition and enhancing abundance and activity of INA microorganisms (Mühlenbruch et al., 2018). Alternatively, the observed correlation between the chlorophyll a concentration and the INP−10 concentration may not imply causality but may be attributed to the fact that terrestrial runoff simultaneously introduced INPs and nutrients, thereby enhancing the primary production in the fjords (Arrigo et al., 2017; Juul-Pedersen et al., 2015; Terhaar et al., 2021). In line with this, external inputs such as nutrients from terrestrial runoff can change the community composition (Ardyna and Arrigo, 2020) and stimulate primary production (Juranek, 2022). INPs produced by aquatic microalgae were typically reported to be active below −12 °C (Tesson and Šantl-Temkiv, 2018; Thornton et al., 2023); however, INPs from epiphytic bacteria and fungi can nucleate ice at higher temperatures (as high as −2 and −2.5 °C, respectively (Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Huffman et al., 2013; Pouleur et al., 1992; Maki et al., 1974; Vali et al., 1976). As INP concentrations and onset freezing temperatures observed in the two fjords during June were higher than previously reported values, this might indicate that the highly active INPs are originating from other, potentially terrestrial sources. The possibility of terrestrial runoff serving as a source of biological INPs in seawater has also been previously explored (Irish et al., 2019).

Figure 3(a) Number of INPs per liter of seawater for the SBW samples collected in KF (circles) and GF (triangles). The INP data in June are derived from a 10-fold dilution due to the high activity. The boxes represent the data ranges reported by previous studies, and the grey data points represent the data reported by Creamean et al. (2019). (b) Comparison of the T50 temperatures in the SBW in relation to the SML for KF (circles) and GF (triangles). The dashed line represents the 1:1 fraction.

3.3 Shift in INP size and properties over time

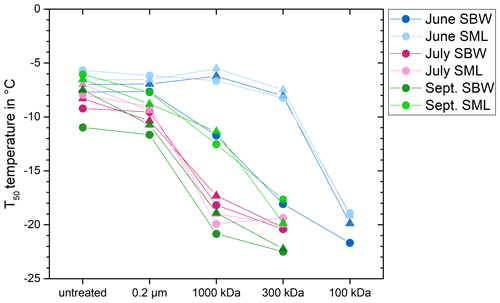

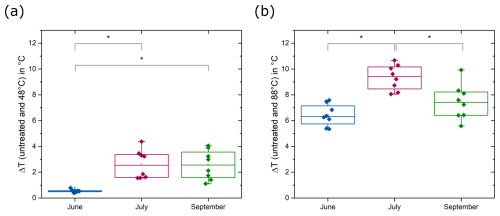

By further characterizing the INPs, we aimed to understand how their properties fit with the properties of INA compounds produced by known INA organisms. Thus, we examined the size and heat sensitivity of the INPs based on changes in T50 temperatures. In June, T50 temperatures remained constant until a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 300 kDa and decreased significantly after filtration with a 100 kDa MWCO (Mann–Whitney, p= 0.03, Fig. S5). Only the SBW sample collected in June in KF showed a reduction in the freezing temperatures after filtration with a MWCO of 1000 kDa (Fig. 4). The data suggest that the predominant size range of INPs in June falls between 100 and 300 kDa. Conversely, in all samples collected in July, the T50 temperatures decreased to below −17 °C after filtration with a MWCO of 1000 kDa. Samples collected in September showed a size disparity between INPs from the SML and the SBW. SML samples showed higher freezing temperatures with INPs in the range of 300 to 1000 kDa, while SBW samples followed the pattern observed in July, indicating INP sizes larger than 1000 kDa (Fig. 4). Overall, our data imply the presence of small biogenic INPs (molecular weight < 300 kDa) in June, coinciding with the late stage of the phytoplanktonic spring bloom. In contrast, for samples collected after the spring bloom in July and September, INPs are larger, with a molecular weight greater than 1000 kDa and 300 kDa, respectively. Further, June samples showed no decrease in T50 temperatures after moderate heating (48 °C), while samples from July and September were negatively affected by moderate heating (Fig. 5). Thus, the INPs with the ability to trigger freezing at high temperatures, primarily present in June, are smaller (100–300 kDa) and less heat sensitive (not affected by 48 °C).

Figure 4Freezing temperatures for a fraction frozen of 0.5 (T50 temperatures) after filtration with different pore size. Results from KF are shown as circles and results from GF are shown as triangles.

The characteristics observed by heat treatments and filtration provide insights into the nature of the INPs. While Hartmann et al. (2021) reported removal of INPs with a 0.2 µm pore size filter in seawater collected from May to mid-July in the Arctic Ocean close to Svalbard, Irish et al. (2017) and Wilson et al. (2015) found that marine INPs were not affected by filtration through a 0.2 µm filter and could only be removed with a smaller pore size of 0.02 µm, approximately corresponding to a 300 kDa MWCO (Sartorius, 2022). Hartmann et al. (2021) suggest that their INPs were associated with larger particles, such as bacteria, algae, fungi, or biological material attached to minerals. Irish et al. (2017) and Wilson et al. (2015) hypothesized that the INPs they observed were small biological virus-size particles, probably phytoplankton or bacteria exudates, and that they did not consist of whole cells or larger cell fragments. Similarly to Irish et al. (2017) and Wilson et al. (2015), we observed small virus-size particles in July and August. During June, however, we observed a different type of INPs, which are smaller than 300 kDa and have according to our knowledge not been previously reported in marine systems. Several studies have shown that while known bacterial ice-nucleating proteins are membrane-bound (Hartmann et al., 2022; Roeters et al., 2021; Garnham et al., 2011) and thus primarily associated with cells, INPs which were washed off pollen grains and fungal cells are within the size range between 100 and 300 kDa (Pummer et al., 2012; Pouleur et al., 1992; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015). Schwidetzky et al. (2023) showed that fungal INPs comprise cell-free proteinaceous aggregates, with 265 kDa aggregates initiating nucleation at −6.8 °C, while smaller aggregates nucleated at lower temperatures. Overall, the properties of the INPs observed in June correspond well with the properties reported for the INA exudates from fungi and pollen and point towards terrestrial environments as a potential source of INPs transported to the seawater.

Figure 5Difference between the T50 temperatures of untreated samples and samples heated to (a) 48 °C and (b) 88 °C (Mann–Whitney, p < 0.05). INPs in July and September are strongly influenced by moderate heating (48 °C), while INPs in June are less affected. All samples show significantly reduced T50 temperatures after heating to 88 °C (Mann–Whitney, p < 0.01).

Heat treatments are commonly performed to distinguish between biogenic INPs and inorganic INPs, assuming that the ice nucleation activity of biogenic INPs decreases when heated to sufficiently high temperatures, typically above 90 °C, due to protein denaturation (Daily et al., 2022). Although biological INPs can show distinct sensitivity to heating, heat treatments for environmental samples are often carried out at only one temperature (Daily et al., 2022, and references therein). Few studies conducted comprehensive heat treatments including more than a single denaturation temperature. Wilson et al. (2015) carried out heat treatments for SML samples for nine temperatures between 20 and 100 °C and observed decreasing activity with increasing heating temperatures. In combination with additional evidence, such as the results of filtrations, they attribute the ice nucleation activity to phytoplankton exudates present in the SML. D'Souza et al. (2013) found significantly reduced freezing temperatures for filamentous diatoms from ice-covered lakes after heating to 45 °C. Hara et al. (2016) showed that the majority of INPs from snow samples that were active above −10 °C are inactivated at 40 °C, similar to those associated with Pseudomonas syringae cells. While bacterial INPs are typically proteinaceous and denature at temperatures above 40 °C (Pouleur et al., 1992; Hara et al., 2016), INPs from pollen, fungal spores, and lichen (Kieft and Ruscetti, 1990) are more heat-resistant. INPs in pollen washing water were thermally stable up to 112 °C (Pummer et al., 2012), and INPs from fungal spores of Fusarium sp. and Mortierella alpina, as well as INPs from lichen, were proteinaceous and heat-stable up to 60 °C (Pouleur et al., 1992; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Kieft and Ruscetti, 1990). While the INPs that we found in July and September behaved similarly to INPs studied by Wilson et al. (2015), the INPs that we observed in June behaved similarly to what has previously been found for terrestrial INPs stemming from fungi, lichen, and pollen (Pouleur et al., 1992; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015; Kieft and Ruscetti, 1990).

The observation that INPs in June are smaller and exhibit distinct responses to heat treatments compared to those observed later in the summer supports the idea that they represent distinct types of INPs. We propose two alternative explanations for the origin of the specific type of INPs observed in June. They could either have been produced by indigenous microbial processes in the seawater or be transported into seawater from terrestrial environments by streams. Based on laboratory studies of known INA organisms, INPs in June may have been released by pollen, fungal spores, or lichen in terrestrial environments and introduced into the seawater by terrestrial runoff. Alternatively, INPs could be yet unknown and uncharacterized molecules produced by marine microorganisms in the late-bloom season. INPs present in July and September have similar properties reported previously by several studies in marine systems, indicating that indigenous microbial processes during the post-bloom period were responsible for their production. However, INPs observed in July and September could also emerge due to aging processes modifying the properties of INPs introduced in June. The increase in INP molecular weight could be due to aggregation in the seawater. Organic matter is known to agglomerate over time or accumulate in transparent exopolymer particles (TEPs), forming larger particles (Mari et al., 2017). TEPs are organic polymer gels primarily composed of heteropolysaccharides that form a hydrogel matrix (Engel et al., 2017). TEPs are highly adhesive and can enhance the aggregation of particles in water. Assembly and disaggregation processes result in different size ranges of the gels, typically exceeding 0.4 µm (Meng and Liu, 2016). Small INPs, which would typically pass through the filters used, might adhere to TEPs and would be consequently removed by filtration.

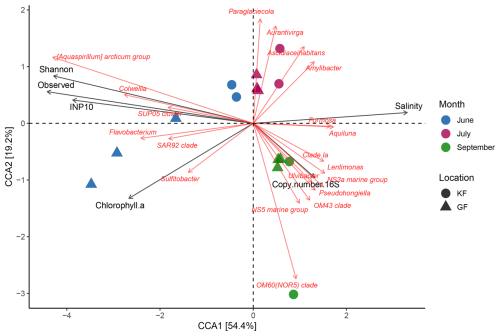

3.4 Correlation of INP concentration to environmental variables, microbial abundance, and community composition

We performed qPCR and amplicon sequencing to link the abundance and diversity of bacteria and microalgae to the types and concentrations of various INPs that we observed in the samples. While the 18S rRNA data aimed to decipher whether the INPs are linked to specific marine microalgae and thus likely produced indigenously in the seawater, the 16S rRNA data are used to both identify potential bacterial producers of INPs associated with phytoplankton blooms and to provide insights into the source environment of INPs transported from terrestrial environments. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was utilized to determine correlations between environmental factors (salinity, chlorophyll a), the microbial community compositions, and the INP concentrations in both SBW and SML samples.

Considering the correlation we observed between the chlorophyll a and the INP−10 concentration, we employed a community analysis of microalgae to search for potential indigenous producers of INPs. The microalgal community, as derived from the 18S rRNA data, is presented in Figs. S6 and S7. We identified several typical bloom-forming taxa such as centric diatom Chaetoceros (Biswas, 2022; Booth et al., 2002; Balzano et al., 2017), dinoflagellate Gyrodinium (Johnsen and Sakshaug, 1993; Hegseth and Sundfjord, 2008), and green algae Micromonas (Vader et al., 2015; Marquardt et al., 2016). We found a slight insignificant (p=0.123) increase in the 18S rRNA gene copy numbers from June to September (Fig. S8). While the observed alpha diversity was not significantly different between the different months (Fig. S9), there was a significant distinction in the composition of the microalgal community (PERMANOVA, p < 0.001, Fig. S10). The CCA shows a correlation of the microalgal community composition with salinity and chlorophyll a (Fig. S11, Table S1 in the Supplement), implying that a combination of bloom dynamics and terrestrial runoff may have affected the communities. There was no correlation between the community composition and the INP−10 concentrations (Table S1). We also investigated the association between specific microalgal taxa and the concentration of INP−10 using Spearman's rank correlation analysis. While 22 taxa significantly correlated with the INP−10 concentration (see dataset in Wieber et al., 2024b), the majority of these taxa were present at low relative abundances (< 0.01 of the total community); none of them were present across samples collected at different times; and they did not include putative bloom-associated taxa Chaetoceros, Gyrodinium, or Micromonas. Thus, bloom-associated marine microalgae do not seem to be plausible producers of the observed INPs.

Further, we used the bacterial community composition to identify potential marine bacterial producers of INPs and to obtain insights into the source environment of the observed INPs. The 16S rRNA analysis showed increasing 16S rRNA gene copy numbers from June to September, with a significantly higher alpha diversity of bacteria (observed and Shannon) in June (Fig. S12). A comparably high microbial alpha diversity as we observed in June was previously reported for soils adjacent to KF and may point to parts of the community introduced by terrestrial runoff (Šantl-Temkiv et al., 2018). Interestingly, although INPs were concentrated in the SML, bacterial cells did not show a similar pattern, as the differences in copy numbers and alpha diversity between the SML and SBW were not significant. The bacterial community (Figs. S13 and S14) was dominated by the classes Bacteroidia and Gammaproteobacteria. Throughout all months, we observed a high abundance of ASVs affiliated with the genus Polaribacter, which was previously found to correlate with the post-bloom and declining stage of the phytoplanktonic bloom in an Arctic fjord (Feltracco et al., 2021). The principal component analysis (PCA) together with permutational multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA) demonstrated a significant difference between the bacterial community composition in June, July, and September (p < 0.001) (Fig. S15). These findings underscore the seasonal differences in the bacterial community structure, with a lower copy number but higher alpha diversity in June when INP−10 concentrations were highest.

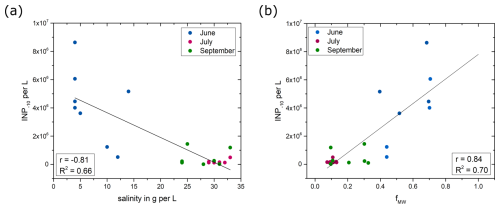

The results of the CCA for the bacterial community are presented in Fig. 6. The bacterial communities in July and September exhibit a higher degree of similarity to each other than the community observed in June. Additionally, the analysis demonstrated similarities between the communities in the two fjords. The Mantel test was subsequently conducted to assess the correlation between bacterial community dissimilarities (measured using robust Aitchison distance) and environmental parameters. We found that the community composition was strongly correlated with the concentration of INP−10 (r= 0.65, p= 0.003). Chlorophyll a was weakly correlated with the bacterial community composition (r= 0.31, p= 0.01), implying that the bloom dynamics had some impact on the community (Table S2). The salinity exhibited a strong correlation (r= 0.67, p= 0.003), emphasizing its influential role in shaping the bacterial community composition (Table S2). Further, we found a strong negative correlation (r= −0.81, p < 0.001) between salinity and the concentration of INP−10 with significantly lower salinity but higher concentration of INPs observed in June (Fig. 7a). These correlations suggest a strong impact of salinity within the observed fjords, both impacting the bacterial community composition as well as the INP−10 concentrations. The observed freshening of the seawater can be attributed to freshwater input, which may originate from either terrestrial runoff or the melting of sea ice. Either terrestrial runoff could contain INPs produced by terrestrial microorganisms that were introduced into the fjord system from the same source as the bacteria, or it might provide nutrients to marine microorganisms, thereby enhancing microbial production of ice nucleation active material in the fjords (Irish et al., 2019; Irish et al., 2017; Meire et al., 2017; Arrigo et al., 2017). Alternatively, sea ice meltwater could be a potential source of INPs; however, studies that demonstrate the presence of highly active INPs in sea ice are still lacking.

Figure 6Canonical correspondence analysis for the 16S rRNA data (20 taxa). Small angles between the arrows indicate a good correlation between the taxa and the external parameter, while the length of the arrow indicates the importance of this parameter. As we observed a negative correlation between the salinity and the ice nucleation activity, these arrows point in opposite directions.

Using CCA we found a co-occurrence between three taxa, Aquaspirillum arcticum, Colwellia sp., and SUP05 (sulfur-oxidizing Proteobacteria cluster 05), and a high concentration of INP−10 in the samples (Fig. 6). As confirmed by Spearman correlation, the co-occurrence was strong between INP−10 and the abundance of Aquaspirillum arcticum (r= 0.90, p < 0.001), a psychrophilic bacterium found in freshwater Arctic environments (Butler et al., 1989; Brinkmeyer et al., 2004) and Colwellia sp. (r= 0.83, p < 0.001) commonly found in sea ice and polar seas (Brinkmeyer et al., 2004). Further, we identified a strong correlation between the presence of ∼ 300 bacterial taxa and the concentration of INP−10 (see dataset in Wieber et al., 2024b). The most abundant of these bacterial taxa were affiliated to known marine bacterial groups (e.g., SAR11 clade Ia, Candidatus Aquiluna, and Amylibacter) but were negatively correlated with INP−10, excluding them as potential INP producers. Among the known INA genera, only Pseudomonas was found to correlate with INP−10. The properties of the highly active INPs reported in this study differ from what has been previously reported for ice-nucleating proteins produced by several species of Pseudomonas (Hartmann et al., 2022; Hara et al., 2016; Garnham et al., 2011), implying that members of this genus were not likely the producers of these INPs. As we found several bacterial taxa correlating with INP−10, it is possible that previously unknown INA bacteria, producing INA compounds different from known bacterial ice-nucleating proteins, could be responsible for the ice nucleation activity observed. In the environment, it is likely that the INPs released as exudates (Pummer et al., 2012; Pouleur et al., 1992; Fröhlich-Nowoisky et al., 2015), such as the ones we found predominant during June, may be disassociated from their producer both in the original environments and during their transport to other environments, which may affect the ability to detect both the INP and its producers simultaneously. Therefore, conclusions based on correlations should in cases, where INP exudates are involved, be taken with care and would require further confirmation of putative novel INA microorganisms through cultivation and testing. Alternatively, INPs and bacterial taxa which correlated with the presence of INPs might not be their producers but could have been co-transported to the fjords from terrestrial source environments. This is supported by the significantly positive correlation between INP−10 and the presence of bacteria typically associated with soil and terrestrial environments such as Rhodoferax (Lee et al., 2022), Glaciimonas (Zhang et al., 2011), and Janthinobacterium (Chernogor et al., 2022) (see dataset in Wieber et al., 2024b) as well as the correlation between bacterial diversity and INP−10 concentrations (Table S2). Overall, the bacterial community analysis aligns with the conclusion that terrestrial runoff may be the key source of the freshwater input and thus low salinities in June. The timely co-occurrence of high INP concentrations with the post-phytoplanktonic bloom is likely a spurious correlation as terrestrial runoff may also contain nutrients that could stimulate the phytoplanktonic bloom (Juranek, 2022). While the previously presented results indicate that terrestrial runoff is responsible for the reduced salinity observed in June, which correlated to high INP concentrations, we included the analysis of stable oxygen isotopes δ18O to exclude the possibility of melting sea ice driving the freshening of the seawater.

3.5 Freshwater fractions from sea ice meltwater and meteoric water

The freshwater fractions of sea ice meltwater and meteoric water were calculated and correlated to the number of INPs active at −10 °C. A stronger correlation was found between the number of INP−10 and the fraction of meteoric water (r= 0.84, p < 0.001) as shown in Fig. 7b, while correlations with sea ice meltwater were weaker (r= 0.64, p < 0.001, Fig. S16), implying a predominant influence of freshwater from melting glaciers and snow.

Figure 7The INP−10 concentration as a function of (a) salinity and (b) freshwater fractions from meteoric water. The lines represent linear regressions of all data points shown in the graphs. Both correlations are significant (p < 0.001).

The study region is surrounded by six glaciers, including three marine-terminating glaciers, supplying meltwater and runoff into the fjords (Van As et al., 2014). The modeling study by Van As et al. (2014) showed that melt and runoff in the Nuuk region doubled during the past 2 decades. The summer melt season in 2018 recorded exceptionally high surface melting across the Greenland Ice Sheet, surpassing preceding records in early June, late July, and early August (Osborne et al., 2018). Previous studies have shown that meteoric water, including glacial outwash sediment (Tobo et al., 2019; Xi et al., 2022), rivers (Knackstedt et al., 2018), and thawing permafrost and thermokarst lakes (Creamean et al., 2020; Barry et al., 2023), contains high concentrations of INPs active at high sub-zero temperatures. Glacial outwash from the Arctic region was found to contain highly active organic INPs (Tobo et al., 2019). Xi et al. (2022) also demonstrated the presence of INPs active above −15 °C in glacial outwash sediments, albeit in smaller concentrations. Analysis of river samples revealed significant ice nucleation activity attributed to submicron-sized biogenic INPs, exhibiting comparable ice nucleus spectra to those produced by the soil fungus Mortierella alpina, implying a terrestrial source for these INPs (Knackstedt et al., 2018). The fact that the study region is impacted by terrestrial runoff and glacial meltwater, as well as the strong correlation between the fraction of meteoric water and the INP−10 concentration, supports the conclusion that terrestrial runoff is a major source of marine INPs in the investigated region. An extrapolation of the trend line in Fig. 7b leads to an estimated concentration of 7.8×106 INPs per liter active at −10 °C in pure meteoric water (fMW=1), which is in good agreement with the average concentration of 1.0×107 INPs per liter active at −10 °C reported for freshwater samples from streams in eastern Greenland by Jensen et al. (2025).

With ongoing warming in the Arctic, microbial activity, and production of INP in terrestrial environments might increase, and thawing permafrost, glaciers, and ice sheets may become of increasing importance as contributors of INPs to coastal marine areas. Especially in fjord systems where the mixing with the open water is less pronounced, terrestrial input might lead to increased INP concentrations in seawater and especially the SML. When these INPs get aerosolized from marine areas, they can trigger ice formation in clouds and, in turn, impact the properties of clouds and thus their radiative forcing (Serreze and Barry, 2011; Tan and Storelvmo, 2019). While ice-free terrestrial areas have been previously shown to impact the atmospheric concentration of INPs (Tobo et al., 2024), aerosolization of highly active terrestrial INPs from marine areas might represent an additional transport mechanism.

In this study, we investigated the ice-nucleating particles in SBW and in the SML samples in relation to phytoplanktonic blooms and terrestrial runoff in two fjords in southwest Greenland. We observed a high concentration of INPs in June, which decreased in July and September. Filtration and heat treatments revealed a novel type of marine INPs in June, characterized by smaller sizes and lower heat sensitivity compared to INPs observed later in the summer and those previously identified in Arctic marine systems. Abundant INPs in June co-occurred with a low abundance of bacterial cells characterized by a high taxonomic diversity characteristic of terrestrial ecosystems. We noted a robust inverse relationship between salinity and the abundance of INPs, indicating that freshwater inputs likely contribute to increased INP concentrations. Stable oxygen isotopes in the freshwater fractions point towards meteoric water as the major source of the freshwater that could wash terrestrial originating INPs into the fjords. This was supported by the fact that INPs also strongly correlated with the presence of terrestrial and freshwater bacteria, e.g., Aquaspirillum arcticum, Rhodoferax, and Glaciimonas. The timely co-occurrence with the phytoplanktonic bloom is rather a correlation and not a causation of the elevated INP concentrations as the freshwater also contains nutrients that could stimulate the phytoplanktonic bloom. Vertical mixing of the water column may have diluted INP concentrations in the upper marine layer, resulting in decreased INP concentrations in the subsequent months. However, the types of INP observed in July and September were distinct from those in June, indicating that these came from another, potentially indigenous source. Based on several lines of evidence including the INP properties, the negative correlation with salinity, the stable oxygen isotope analysis, the correlation with microbial diversity, and the co-occurrence of INP with terrestrial bacterial species, we conclude that the highly active and abundant INPs that we observed in seawater in June originate from a terrestrial source, such as glacial and soil runoff. The quantitative significance of terrestrial INPs in marine environments outside fjord systems and coastal areas, as well as the extent to which sea spray contributes to their total atmospheric fluxes, needs to be determined through further investigation.

The data presented in this study are deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive under the accession number PRJNA1108919 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1108919/, National Library of Medicine, 2024). The dataset for the taxa correlating with the INP−10 concentration is accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14044413 (Wieber et al., 2024b).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-3327-2025-supplement.

TST and KF designed and supervised the research project. LV collected the SML and SBW samples in Greenland. LM and TJP provided data for the chlorophyll concentrations. LZJ performed the microbial and bioinformatic analysis. CW conducted the ice nucleation measurements and performed the data analysis. CW led the writing with contributions from LZJ, KF, and TST. All authors were involved in manuscript revision, and have approved the submitted version.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We are grateful to Ana Sofia Ferreira for analyzing the chlorophyll satellite data. The authors thank Egon Randa Frandsen for providing logistical support and assisting with the measurements of stable oxygen isotopes and Inge Buss la Cour for conducting the measurements of stable oxygen isotopes. Further, we would like to gratefully acknowledge Mette L. G. Nikolajsen and Britta Poulsen for their assistance in the laboratory as well as Claus Melvad and Mads Rosenhøj Jeppesen for their support with the micro-PINGUIN instrument. Data from the Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring program were provided by the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, Nuuk, Greenland, in collaboration with the Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Denmark, and the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

This work was supported by the Villum Foundation (grant nos. 23175 and 37435), the Independent Research Fund Denmark (grant no. 9145-00001B), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant no. NNF19OC0056963), the Danish National Research Foundation (grant no. DNRF106, to the Stellar Astrophysics Centre, Aarhus University), and the Carlsberg Foundation (grant no. CF21-0630 and CF24-1911).

This paper was edited by Luis A. Ladino and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Adams, M. P., Atanasova, N. S., Sofieva, S., Ravantti, J., Heikkinen, A., Brasseur, Z., Duplissy, J., Bamford, D. H., and Murray, B. J.: Ice nucleation by viruses and their potential for cloud glaciation, Biogeosciences, 18, 4431–4444, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-4431-2021, 2021.

Alkire, M. B., Morison, J., and Andersen, R.: Variability in the meteoric water, sea-ice melt, and Pacific water contributions to the central Arctic Ocean, 2000–2014, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 120, 1573–1598, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JC010023, 2015.

Ardyna, M. and Arrigo, K. R.: Phytoplankton dynamics in a changing Arctic Ocean, Nat. Clim. Change, 10, 892–903, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0905-y, 2020.

Arrigo, K. R.: Marine microorganisms and global nutrient cycles, Nature, 437, 349–355, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04159, 2005.

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G., and Pabi, S.: Impact of a shrinking Arctic ice cover on marine primary production, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L19603, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035028, 2008.

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G. L., Castelao, R. M., Luo, H., Rennermalm, Å. K., Tedesco, M., Mote, T. L., Oliver, H., and Yager, P. L.: Melting glaciers stimulate large summer phytoplankton blooms in southwest Greenland waters, Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 6278–6285, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073583, 2017.

Balzano, S., Percopo, I., Siano, R., Gourvil, P., Chanoine, M., Marie, D., Vaulot, D., and Sarno, D.: Morphological and genetic diversity of Beaufort Sea diatoms with high contributions from the Chaetoceros neogracilis species complex, J. Phycol., 53, 161–187, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.12489, 2017.

Barry, K. R., Hill, T. C. J., Nieto-Caballero, M., Douglas, T. A., Kreidenweis, S. M., DeMott, P. J., and Creamean, J. M.: Active thermokarst regions contain rich sources of ice-nucleating particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 15783–15793, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-15783-2023, 2023.

Bidle, K. D. and Azam, F.: Accelerated dissolution of diatom silica by marine bacterial assemblages, Nature, 397, 508–512, https://doi.org/10.1038/17351, 1999.

Biswas, H.: A story of resilience: Arctic diatom Chaetoceros gelidus exhibited high physiological plasticity to changing CO2 and light levels, Front. Plant Sci., 13, 1028544, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1028544, 2022.

Booth, B. C., Larouche, P., Bélanger, S., Klein, B., Amiel, D., and Mei, Z. P.: Dynamics of Chaetoceros socialis blooms in the North Water, Deep-Sea Res. Pt. II, 49, 5003–5025, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00175-3, 2002.

Box, J. E., Colgan, W. T., Christensen, T. R., Schmidt, N. M., Lund, M., Parmentier, F.-J. W., Brown, R., Bhatt, U. S., Euskirchen, E. S., Romanovsky, V. E., Walsh, J. E., Overland, J. E., Wang, M., Corell, R. W., Meier, W. N., Wouters, B., Mernild, S., Mård, J., Pawlak, J., and Olsen, M. S.: Key indicators of Arctic climate change: 1971–2017, Environ. Res. Lett., 14, 045010, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aafc1b, 2019.

Brinkmeyer, R., Glöckner, F.-O., Helmke, E., and Amann, R.: Predominance of â-proteobacteria in summer melt pools on Arctic pack ice, Limnol. Oceanogr., 49, 1013–1021, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2004.49.4.1013, 2004.

Browse, J., Carslaw, K. S., Mann, G. W., Birch, C. E., Arnold, S. R., and Leck, C.: The complex response of Arctic aerosol to sea-ice retreat, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 7543–7557, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-7543-2014, 2014.

Burgers, T. M., Miller, L. A., Thomas, H., Else, B. G. T., Gosselin, M., and Papakyriakou, T.: Surface Water pCO2 Variations and Sea-Air CO2 Fluxes During Summer in the Eastern Canadian Arctic, J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 122, 9663–9678, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JC013250, 2017.

Burkart, J., Gratzl, J., Seifried, T. M., Bieber, P., and Grothe, H.: Isolation of subpollen particles (SPPs) of birch: SPPs are potential carriers of ice nucleating macromolecules, Biogeosciences, 18, 5751–5765, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-5751-2021, 2021.

Butler, B. J., McCallum, K. L., and Inniss, W. E.: Characterization of Aquaspirillum arcticum sp. nov., a New Psychrophilic Bacterium, Syst. Appl. Microbiol., 12, 263–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0723-2020(89)80072-4, 1989.

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J., and Holmes, S. P.: DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Meth., 13, 581–583, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869, 2016.

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., and Holmes, S. P.: Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis, ISME J., 11, 2639–2643, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.119, 2017.

Chadburn, S. E., Burke, E. J., Cox, P. M., Friedlingstein, P., Hugelius, G., and Westermann, S.: An observation-based constraint on permafrost loss as a function of global warming, Nat. Clim. Change, 7, 340–344, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3262, 2017.

Chernogor, L., Bakhvalova, K., Belikova, A., and Belikov, S.: Isolation and Properties of the Bacterial Strain Janthinobacterium sp. SLB01, Microorganisms, 10, 1071, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10051071, 2022.

Creamean, J. M., Cross, J. N., Pickart, R., McRaven, L., Lin, P., Pacini, A., Hanlon, R., Schmale, D. G., Ceniceros, J., Aydell, T., Colombi, N., Bolger, E., and DeMott, P. J.: Ice Nucleating Particles Carried From Below a Phytoplankton Bloom to the Arctic Atmosphere, Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, 8572–8581, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL083039, 2019.

Creamean, J. M., Hill, T. C. J., DeMott, P. J., Uetake, J., Kreidenweis, S., and Douglas, T. A.: Thawing permafrost: an overlooked source of seeds for Arctic cloud formation, Environ. Res. Lett., 15, 084022, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab87d3, 2020.

Creamean, J. M., Barry, K., Hill, T. C. J., Hume, C., DeMott, P. J., Shupe, M. D., Dahlke, S., Willmes, S., Schmale, J., Beck, I., Hoppe, C. J. M., Fong, A., Chamberlain, E., Bowman, J., Scharien, R., and Persson, O.: Annual cycle observations of aerosols capable of ice formation in central Arctic clouds, Nat. Commun., 13, 3537, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31182-x, 2022.

Cunliffe, M., Engel, A., Frka, S., Gašparoviæ, B., Guitart, C., Murrell, J. C., Salter, M., Stolle, C., Upstill-Goddard, R., and Wurl, O.: Sea surface microlayers: A unified physicochemical and biological perspective of the air–ocean interface, Prog. Oceanogr., 109, 104–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2012.08.004, 2013.

Daily, M. I., Tarn, M. D., Whale, T. F., and Murray, B. J.: An evaluation of the heat test for the ice-nucleating ability of minerals and biological material, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 2635–2665, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-15-2635-2022, 2022.

Davis, N. M., Proctor, D. M., Holmes, S. P., Relman, D. A., and Callahan, B. J.: Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data, Microbiome, 6, 226, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2, 2018.

Dixon, P.: VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology, J. Veg. Sci., 14, 927–930, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02228.x, 2003.

D'Souza, N. A., Kawarasaki, Y., Gantz, J. D., Lee, R. E., Jr., Beall, B. F., Shtarkman, Y. M., Kocer, Z. A., Rogers, S. O., Wildschutte, H., Bullerjahn, G. S., and McKay, R. M.: Diatom assemblages promote ice formation in large lakes, ISME J., 7, 1632–1640, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.49, 2013.

Engel, A., Piontek, J., Metfies, K., Endres, S., Sprong, P., Peeken, I., Gäbler-Schwarz, S., and Nöthig, E.-M.: Inter-annual variability of transparent exopolymer particles in the Arctic Ocean reveals high sensitivity to ecosystem changes, Sci. Rep., 7, 4129, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04106-9, 2017.

Eufemio, R. J., de Almeida Ribeiro, I., Sformo, T. L., Laursen, G. A., Molinero, V., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Bonn, M., and Meister, K.: Lichen species across Alaska produce highly active and stable ice nucleators, Biogeosciences, 20, 2805–2812, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-2805-2023, 2023.

Feltracco, M., Barbaro, E., Hoppe, C. J. M., Wolf, K. K. E., Spolaor, A., Layton, R., Keuschnig, C., Barbante, C., Gambaro, A., and Larose, C.: Airborne bacteria and particulate chemistry capture Phytoplankton bloom dynamics in an Arctic fjord, Atmos. Environ., 256, 118458, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118458, 2021.

Fransson, A., Chierici, M., Granskog, M. A., Dodd, P. A., and Stedmon, C. A.: Impacts of glacial and sea-ice meltwater, primary production, and ocean CO2 uptake on ocean acidification state of waters by the 79 North Glacier and northeast Greenland shelf, Frontiers in Marine Science, 10, 1155126, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1155126, 2023.

Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Hill, T. C. J., Pummer, B. G., Yordanova, P., Franc, G. D., and Pöschl, U.: Ice nucleation activity in the widespread soil fungus Mortierella alpina, Biogeosciences, 12, 1057–1071, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-1057-2015, 2015.

Garnham, C. P., Campbell, R. L., Walker, V. K., and Davies, P. L.: Novel dimeric â-helical model of an ice nucleation protein with bridged active sites, BMC Struct. Biol., 11, 36, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6807-11-36, 2011.

Govindarajan, A. G. and Lindow, S. E.: Size of bacterial ice-nucleation sites measured in situ by radiation inactivation analysis, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 1334–1338, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.5.1334, 1988.

Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring: MarineBasis Nuuk – Water column – Phosphate Concentration (µmol/L), Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring [data set], https://doi.org/10.17897/PZNK-SP15, 2020a.

Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring: MarineBasis Nuuk – Water column – Nitrate + Nitrite Concentration (µmol/L), Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring [data set], https://doi.org/10.17897/3NQX-FA50, 2020b.

Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring: MarineBasis Nuuk – Water column – Silicate Concentration (µmol/L), Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring [data set], https://doi.org/10.17897/VVQP-F862, 2020c.

Griesche, H. J., Ohneiser, K., Seifert, P., Radenz, M., Engelmann, R., and Ansmann, A.: Contrasting ice formation in Arctic clouds: surface-coupled vs. surface-decoupled clouds, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 10357–10374, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-10357-2021, 2021.

Guillou, L., Bachar, D., Audic, S., Bass, D., Berney, C., Bittner, L., Boutte, C., Burgaud, G., de Vargas, C., Decelle, J., Del Campo, J., Dolan, J. R., Dunthorn, M., Edvardsen, B., Holzmann, M., Kooistra, W. H., Lara, E., Le Bescot, N., Logares, R., Mahé, F., Massana, R., Montresor, M., Morard, R., Not, F., Pawlowski, J., Probert, I., Sauvadet, A. L., Siano, R., Stoeck, T., Vaulot, D., Zimmermann, P., and Christen, R.: The Protist Ribosomal Reference database (PR2): a catalog of unicellular eukaryote small sub-unit rRNA sequences with curated taxonomy, Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D597–D604, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1160, 2013.

Gute, E. and Abbatt, J. P. D.: Ice nucleating behavior of different tree pollen in the immersion mode, Atmos. Environ., 231, 117488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117488, 2020.

Hara, K., Maki, T., Kakikawa, M., Kobayashi, F., and Matsuki, A.: Effects of different temperature treatments on biological ice nuclei in snow samples, Atmos. Environ., 140, 415–419, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.06.011, 2016.

Harrison, W. G. and Li, W. K.: Phytoplankton growth and regulation in the Labrador Sea: light and nutrient limitation, Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 39, 71–82, https://doi.org/10.2960/J.v39.m592, 2007.

Hartmann, M., Gong, X., Kecorius, S., van Pinxteren, M., Vogl, T., Welti, A., Wex, H., Zeppenfeld, S., Herrmann, H., Wiedensohler, A., and Stratmann, F.: Terrestrial or marine – indications towards the origin of ice-nucleating particles during melt season in the European Arctic up to 83.7° N, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 11613–11636, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-11613-2021, 2021.

Hartmann, S., Ling, M., Dreyer, L. S. A., Zipori, A., Finster, K., Grawe, S., Jensen, L. Z., Borck, S., Reicher, N., Drace, T., Niedermeier, D., Jones, N. C., Hoffmann, S. V., Wex, H., Rudich, Y., Boesen, T., and Santl-Temkiv, T.: Structure and Protein-Protein Interactions of Ice Nucleation Proteins Drive Their Activity, Front. Microbiol., 13, 872306, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.872306, 2022.

Harvey, G. W. and Burzell, L. A.: A simple microlayer method for small samples, Limnol. Oceanogr., 17, 156–157, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1972.17.1.0156, 1972.

Hegseth, E. N. and Sundfjord, A.: Intrusion and blooming of Atlantic phytoplankton species in the high Arctic, J. Marine Syst., 74, 108–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.11.011, 2008.

Huffman, J. A., Prenni, A. J., DeMott, P. J., Pöhlker, C., Mason, R. H., Robinson, N. H., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Tobo, Y., Després, V. R., Garcia, E., Gochis, D. J., Harris, E., Müller-Germann, I., Ruzene, C., Schmer, B., Sinha, B., Day, D. A., Andreae, M. O., Jimenez, J. L., Gallagher, M., Kreidenweis, S. M., Bertram, A. K., and Pöschl, U.: High concentrations of biological aerosol particles and ice nuclei during and after rain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 6151–6164, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-6151-2013, 2013.

Huot, Y., Babin, M., Bruyant, F., Grob, C., Twardowski, M. S., and Claustre, H.: Relationship between photosynthetic parameters and different proxies of phytoplankton biomass in the subtropical ocean, Biogeosciences, 4, 853–868, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-4-853-2007, 2007.

Ickes, L., Porter, G. C. E., Wagner, R., Adams, M. P., Bierbauer, S., Bertram, A. K., Bilde, M., Christiansen, S., Ekman, A. M. L., Gorokhova, E., Höhler, K., Kiselev, A. A., Leck, C., Möhler, O., Murray, B. J., Schiebel, T., Ullrich, R., and Salter, M. E.: The ice-nucleating activity of Arctic sea surface microlayer samples and marine algal cultures, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 11089–11117, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-11089-2020, 2020.

IPCC: Global Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedbacks, in: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 673–816, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.007, 2021a.

IPCC: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change, in: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1211–1362, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.011, 2021b.

Irish, V. E., Elizondo, P., Chen, J., Chou, C., Charette, J., Lizotte, M., Ladino, L. A., Wilson, T. W., Gosselin, M., Murray, B. J., Polishchuk, E., Abbatt, J. P. D., Miller, L. A., and Bertram, A. K.: Ice-nucleating particles in Canadian Arctic sea-surface microlayer and bulk seawater, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 10583–10595, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-10583-2017, 2017.

Irish, V. E., Hanna, S. J., Xi, Y., Boyer, M., Polishchuk, E., Ahmed, M., Chen, J., Abbatt, J. P. D., Gosselin, M., Chang, R., Miller, L. A., and Bertram, A. K.: Revisiting properties and concentrations of ice-nucleating particles in the sea surface microlayer and bulk seawater in the Canadian Arctic during summer, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 7775–7787, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-7775-2019, 2019.

Jensen, L. Z., Glasius, M., Gryning, S.-E., Massling, A., Finster, K., and Šantl-Temkiv, T.: Seasonal Variation of the Atmospheric Bacterial Community in the Greenlandic High Arctic Is Influenced by Weather Events and Local and Distant Sources, Front. Microbiol., 13, 909980, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.909980, 2022.

Jensen, L. Z., Simonsen, J. K., Pastor, A., Pearce, C., Nørnberg, P., Lund-Hansen, L. C., Finster, K., and Šantl-Temkiv, T.: Linking biogenic high-temperature ice nucleating particles in Arctic soils and streams to their microbial producers, Aerosol Res., 3, 81–100, https://doi.org/10.5194/ar-3-81-2025, 2025.

Johnsen, G. and Sakshaug, E.: Bio-optical characteristics and photoadaptive responses in the toxic and bloom-forming dinoflagellates Gyrodinium aureolum, Gymnodinium galatheanum, and two strains of Prorocentrum minimum, J. Phycol., 29, 627–642, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3646.1993.00627.x, 1993.

Joly, M., Attard, E., Sancelme, M., Deguillaume, L., Guilbaud, C., Morris, C. E., Amato, P., and Delort, A.-M.: Ice nucleation activity of bacteria isolated from cloud water, Atmos. Environ., 70, 392–400, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.01.027, 2013.

Juranek, L. W.: Changing biogeochemistry of the Arctic Ocean: Surface nutrient and CO2 cycling in a warming, melting north, Oceanography, 35, 144–155, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2022.120, 2022.

Juul-Pedersen, T., Arendt, K. E., Mortensen, J., Blicher, M. E., Søgaard, D. H., and Rysgaard, S.: Seasonal and interannual phytoplankton production in a sub-Arctic tidewater outlet glacier fjord, SW Greenland, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 524, 27–38, 2015.

Kanji, Z. A., Ladino, L. A., Wex, H., Boose, Y., Burkert-Kohn, M., Cziczo, D. J., and Krämer, M.: Overview of Ice Nucleating Particles, Meteor. Mon., 58, 1.1–1.33, https://doi.org/10.1175/amsmonographs-d-16-0006.1, 2017.

Kelley, D., Richards, C., and Layton, C.: oce: an R package for Oceanographic Analysis, Journal of Open Source Software, 7, 3594, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03594, 2022.

Kieft, T. L. and Ruscetti, T.: Characterization of biological ice nuclei from a lichen, J. Bacteriol., 172, 3519–3523, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.172.6.3519-3523.1990, 1990.

Knackstedt, K. A., Moffett, B. F., Hartmann, S., Wex, H., Hill, T. C. J., Glasgo, E. D., Reitz, L. A., Augustin-Bauditz, S., Beall, B. F. N., Bullerjahn, G. S., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Grawe, S., Lubitz, J., Stratmann, F., and McKay, R. M. L.: Terrestrial Origin for Abundant Riverine Nanoscale Ice-Nucleating Particles, Environ. Sci. Technol., 52, 12358–12367, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b03881, 2018.