the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Origin, transport and processing of organic aerosols at different altitudes in coastal Mediterranean urban areas

Clara Jaén

Mireia Udina

Roy Harrison

Joan O. Grimalt

Barend L. Van Drooge

Organic molecular markers in atmospheric PM10 were analysed by off-line GC-MS techniques in an urban background site (81 m above sea level (a.s.l.)) and in a nearby elevated sub-urban background site (415 ), in cold and warm periods in Barcelona; situated in the Western Mediterranean Basin. Previous studies reported similar PM concentrations and substantial organic matter contributions in both sites but did not analyze the organic molecular composition, which is expected to vary within the city's vertical airshed due to a weakening influence of local emission sources and enhanced influence of regional air masses. Multi-variant analysis of organic molecular marker concentrations, together with major air quality parameters (NO, NO2, O3, PM10), resolved six components that represented primary emissions sources and secondary organic aerosol formation processes: (1) diurnal traffic, (2) nocturnal traffic, (3) biomass burning, (4) biogenic with primary and secondary organic markers, (5) fresh secondary, and (6) regional secondary. Urban traffic emissions reached the elevated site during daytime through the sea-mountain breeze, while nocturnal traffic emissions accumulated in the nighttime urban atmosphere, when the two sites were often disconnected by temperature inversions. Biomass burning, dominant in the cold period, was the main contributor to toxic PAHs in these two background sites. Regional secondary organic aerosol contribution was more abundant in the elevated background site. Several SOA formation mechanisms were identified such as the oxidation of traffic emissions by NOx, the aqueous-phase oxidation under high relative humidity, and formation of fresh SOA under conditions of low relative humidity.

- Article

(3850 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(14924 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Particulate matter (PM) interacts with solar radiation modifying the Earth's radiation balance and involving deleterious effects on the ecosystems and human health (Garland et al., 2008; Malavelle et al., 2019; Soleimanian et al., 2020). Chronic PM exposure has been related with increased incidences of stroke, lung cancer, asthma, type II diabetes, myocardial infarction, and mental illnesses (Chen and Hoek, 2020; Janssen et al., 2013; Lida et al., 2017; Manisalidis et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2019).

Airborne PM is generated by primary sources such as traffic, industries, wildfires, and formed secondarily in the atmosphere by photochemical transformations, nucleation or condensation processes of smaller particles or gas-phase compounds in the atmosphere. Both primary and secondary PM can have natural or anthropogenic origins, and their relative contributions depend on the characteristics and intensity of local emissions as well as on the chemical and physical atmospheric conditions. The most important PM constituents are inorganic salts, crustal and anthropogenic minerals, elemental carbon, and organics (Brines et al., 2019; Harrison, 2020; Myhre et al., 2009; Tao et al., 2021).

The contribution of organic aerosol (OA) to PM varies from 20 % to 80 % (Jimenez et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2006; Putaud et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2007). Primary organic aerosols (POA) include marker compounds such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) generated during incomplete combustion of biomass or fossil fuels, hopanes from mineral oils, or anhydrosaccharides from biomass combustion. Conversely, the oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOC) leads to the formation of the secondary organic aerosols (SOA) (Atkinson, 2000; Odum et al., 1996; Palm et al., 2018; Srivastava et al., 2022). This oxidation implies an addition of oxygen and/or nitrogen atoms to the molecular structures reducing the volatility. The VOCs undergoing these processes can be either from biogenic origin such as isoprene and α-pinene or derived from anthropogenic activities like volatile aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, which can be very relevant in Mediterranean cities (Minguillón et al., 2016; van Drooge et al., 2018).

The presence of multiple PM emission sources, combined with unfavorable meteorological conditions, often leads to poor air quality in urban environments. The most severe air quality events typically occur during strong anticyclonic conditions, which promote temperature inversions that trap surface-emitted primary pollutants within shallow mixing layers. Under these conditions, ozone (O3) can accumulate in nocturnal residual layers above the inversion (Jaén et al., 2021a; Massagué et al., 2021). The accumulation of this strong oxidant may also enhance SOA formation in these upper layers as well as during daytime due to increased photochemical activity. This phenomenon is especially relevant in the Western Mediterranean Basin (WMB) that has particular air pollution dynamics due to its location between mid-latitudes and subtropical regimes and the influence of the Mediterranean Sea (Derstroff et al., 2017).

Over the last decade, several studies carried out in the metropolitan area of Barcelona gave insight on the spatial and vertical evolution of particles and other air quality parameters in the urban airshed, although the molecular organic composition was only described at the lower city level (Alier et al., 2013; Brines et al., 2019; Dall'Osto et al., 2013; van Drooge et al., 2018). These studies showed that traffic related pollutants were mainly attributed to local emission sources, while pollutants from biomass burning, harbour and industrial emissions, as well as compounds related to secondary aerosol formation processes, were of regional origin. Concerning vertical mixing within the urban airshed, the previous studies suggested that the air column above the city presents conditions that promote new particle formation (NPF) events and SOA formation due to a presumed weakening influence of local source emissions to PM. Although the higher ratios that were observed in the elevated sites above the city can be related to these aerosol formation processes (Dall'Osto et al., 2013), it was not clear to what extend local emissions other than traffic, such as biomass burning emissions, and recirculation of regional air masses influence these elevated urban background sites.

Organic matter is an important contributor to PM10 in the urban background sites, but detailed information on the molecular organic compound composition at various altitudes is limited and has not been studied yet in this vertical urban Mediterranean setting. The present study aims to characterize the POA emissions and accumulation conditions, as well as SOA formation processes in the urban background atmosphere of Barcelona through the analysis of molecular organic makers in PM10 in two altitudes (81 and 415 ) at 12 h intervals, covering day and nighttime over one week in warm and cold periods.

2.1 Sampling site

Barcelona is located on the north-eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula in the Western Mediterranean Basin. This region is a model case of environmental challenges in transition zones between temperate and arid climates. The WMB experiences intense solar radiation throughout the year, leading to high photochemical activity, even in winter. This solar activity interacts with the biogenic VOCs emitted by the region's abundant vegetation, resulting in the formation of large amounts of SOA (Ciccioli et al., 2023; van Drooge et al., 2018). Additionally, the PM mass and composition in the WMB are often altered by the transport of mineral dust from the arid regions of North Africa worsening the air quality in the basin (Querol et al., 2009; Schepanski et al., 2016).

The synoptic and regional meteorological scale affecting the WMB is mainly driven by the Azores high-pressure system, the Saharan and Iberian low-pressures, the topography, and the heat-moisture regulation by the Mediterranean Sea. The interactions between these factors lead to highly contrasting temperature, humidity and rainfall conditions among seasons. Barcelona is geographically limited by two rivers on the east and west sides, by the Mediterranean Sea in the south and by the Collserola hills in the north (512 ). Due to this orography, the city is typically influenced by sea breezes that flow inland during the day as solar heating enhances the vertical ascent of warmer air over the city creating a surface horizonal thermal gradient. At night, the opposite occurs as the cooler air above the city subsides. In the absence of large-scale meteorological phenomena, this can create a recirculation pattern, leading to distinct air masses at the surface and upper levels.

The city of Barcelona is home to 1.7 million inhabitants, while its metropolitan area hosts around 3.7 million people, involving one of the highest population densities in Europe (16 339 ). The car density in the city is around 6000 km−2 with a daily vehicle flux of 350 000 in the city centre and up to 151 000 in the main ring roads (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2024). Moreover, the activities in the nearby harbour and airport, the agricultural works in the Llobregat river delta and the emissions from several industrial zones and power plants in the metropolitan area are additional potential sources influencing the air quality of the city (Dall'Osto et al., 2013).

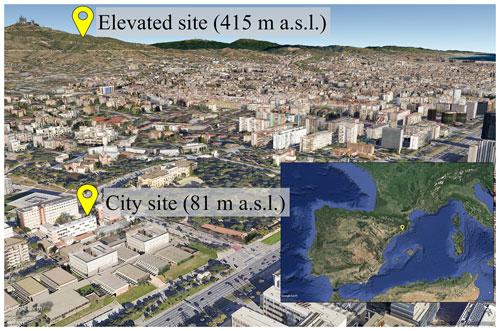

In the present study, PM10 samples were collected at two background stations at different altitudes (Fig. 1) to assess how interactions between specific meteorological conditions and multisource particle emissions influence the organic composition of airborne aerosols in the city. One station, located at 81 , represents the urban background site at IDAEA (city site), while the other, at 415 , is situated atop the Collserola hills overlooking the city (elevated site). The two sites are separated by a horizontal distance of 3.5 km. The urban background site is situated within the city airshed while the atmosphere in the elevated site can be located either within the urban airshed or above the atmospheric layer influenced by the city in the case of low planetary boundary layer height (PBLH) because of strong temperature inversions.

2.2 Sampling methodology

PM10 samples (n=52) were collected at 12 h intervals on 150 mm-diameter quartz filters (Pall Corporation, USA) by means of a high-volume sampler (DHA-80, Digitel, Switzerland) equipped with a PM10 inlet. Filters were pre-baked at 450 °C before use. The instrument air flow was 500 L min−1, providing a final sample volume of 360 m3. Sample collection was performed simultaneously at both sites during two one-week campaigns in the warm and cold periods (26 April–3 May 2022 and 31 January–6 February 2023, respectively). Daytime samples were taken from 07:00 to 19:00 UTC (09:00–21:00 and 08:00–20:00 LT during the warm and cold periods, respectively). The nighttime samples were collected from 19:00 to 07:00 UTC.

2.3 Chemical analysis

The analytical procedure to determine the concentration of organic compounds in the samples was performed as described in previous studies (Fontal et al., 2015; Jaén et al., 2021b, 2023). Briefly, two 45 mm-diameter punches of the whole filter were spiked with deuterated PAH (, , , , , , , , , , , ), and . Then, the filter fractions were extracted with a dichloromethane : methanol 1:1 mixture by ultra-sonication (3 mL×10 mL; 15 min). The obtained extracts were filtered with glass-microfibre discs and concentrated to 0.5 mL by means of roto-evaporators and with a nitrogen stream. A 25 µL aliquot of the extract was transferred to a conical vial, evaporated to dryness and treated with 25 µL of BSTFA and 10 µL of pyridine to obtain the trimethylsilyl derivatives of the compounds with hydroxyl groups. This aliquot was injected to a GC-MS (8290 GC with 5975 MSD, Agilent Technologies) in full scan mode to quantify the polar compounds (isoprene or α-pinene SOA products, dicarboxylic acids and saccharides). A liquid–liquid extraction was performed with the remaining extract with n-hexane (3 mL×0.5 mL) to analyse the non-polar fraction (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), their methyl (mPAH) and oxygenated (oxyPAH) derivatives, alkanes and hopanes). The hexane extract was concentrated with a nitrogen stream to a final volume of 25 µL prior to its injection in a Q-Exactive GC Orbitrap MS (Agilent Technologies) in full scan mode. The chromatographic separation was obtained with a HP-5MS 60 m capillary column for the polar compounds and with a HP-5MS 30 m column for the non-polar, in order to achieve optimum separation compounds of each group.

Two additional 45 mm-diameter punches of the filter were spiked with 9-nitroanthracene-d9 and extracted with 7 mL of DCM by ultra-sonication during 20 min for the analyses of nitro derivatives of PAH (nitro-PAH). The extract was concentrated with a nitrogen stream and then filtered with anhydrous sodium sulphate contained in a Pasteur pipette with glass wool. The filtered extract was further evaporated to 50 µL with a nitrogen stream, 50 µL of nonane were added to the extract and the concentration continued to evaporate the remaining DCM. The extracts were analyzed by GC-MS using an Agilent 5973N Inert EI/CI Mass Spec Selective Detector with a Agilent 6890N Gas Chromatograph) operated in SIM and in negative ion chemical ionisation (NICI) mode equipped with a Restek Rxi-5Sil MS 60 m column (2022 campaing) or by GC–MS/MS using an Agilent 7000 Series Triple Quad) equipped with a HP-5MS 60 m capillary column (2023 campaign). In this last case, the instrument operated under electron impact ionization and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used for acquisition. These instrumental methodologies provided equivalent nitro-PAH results.

Sixty-eight compounds were identified and quantified based on their chromatographic retention times, mass spectra and calibration with analytical internal standards and 5-point calibration curves. Field blanks of each sampling campaign and site were collected and treated together with the sample filters. The average blank levels were subtracted from the sample concentrations. The method limit of detection (MLOD), which reflects the entire analytical procedure including sampling, extraction, and analysis, was determined as the average blank level plus three times the standard deviation of blanks (Table 1). In cases where blank values were below the instrumental limit of detection (ILOD), the ILOD was applied instead. ILOD refers specifically to the instrumental performance and was set based on a minimum signal-to-noise ratio of 3 calculated from the lowest point of the calibration curve. To process the data, concentrations below MLOD were replaced by half of this value.

2.4 Air quality and meteorological data

NO, NO2, O3 and PM10 hourly values were obtained from the two air quality stations of the Atmospheric Pollution Monitoring and Forecasting Network situated in the same sites as the PM10 samplers: Palau Reial, IDAEA-CSIC, for the city site and Observatori Fabra for the elevated sub-urban site (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2024a) (Fig. S1 in the Supplement).

Meteorological parameters, including temperature, pressure, relative humidity, precipitation, solar radiation, mean wind velocity (10 m), mean wind direction (10 m) and solar radiation, were obtained every half an hour from two Automatic Weather Stations of the Catalan Meteorological Service (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2024b). These stations were located near the elevated and city sampling sites. The elevated station was adjacent to the corresponding sampling site, while the city station was situated approximately 1.2 km away from the PM sampling site (Fig. S1). This spatial separation may introduce slight differences between the recorded meteorological parameters and those directly affecting the sampled air masses. However, the station shares the same urban background classification as the sampling site and was considered representative of the meteorological conditions. Complementary meteorological data nearby the Barcelona harbour was obtained from a station located in this installation (Figs. S1 and S2 in the Supplement).

PBLHs were estimated from a CL31Vaisala Ceilometer set located at 98 and at 340 m in horizontal distance from the city site (Fig. S1). The original data was processed using the Vaisala Boundary-Layer View software (BL-VIEW) Enhanced Gradient method (García-Dalmau et al., 2021; Vaisala, 2024) followed by a selection algorithm based on the methodology of Lotteraner and Piringer (2016) to obtain PBLH values every 10 min.

2.5 Air mass trajectories and clustering

Backward air trajectories for 96 h were computed with the NOAA HYSPLIT model (Rolph et al., 2017; Stein et al., 2015) provided with NCEP/NCAR Global Reanalysis Data (Kalnay et al., 1996) with a horizontal resolution of 2.5° as meteorological files. The trajectories were computed hourly for the two sampling campaigns at the city site at 100 m above ground level (a.g.l.), at the elevated site at 400 , and at the middle point between both sites at 200 as starting locations. Moreover, a 48 h-cluster analysis joining the two sets of trajectories (the two sampling periods) was performed to elucidate the air mass sources reaching Barcelona at a mesoscale to synoptic meteorological scale. This analysis provided the origins of air masses during the sampling periods. The clustering algorithm groups similar trajectories in clusters and represent them by their mean trajectory. The optimal number of clusters was 5 considering the percentage change in total spatial variance through a step-wise reduction in cluster numbers (92 % from 5 to 4 clusters in the last case). Moreover, the geographical interpretation of the clusters was also taken into consideration. Given the proximity between sampling sites, a lack of significant differences between different altitudes of ending point back-trajectories was observed (Fig. S3 in the Supplement). Therefore, the middle point (Fig. S3b) was used for the work description.

2.6 Multivariate analysis

Multivariate Curve Resolution–Alternating Least Square (MCR-ALS 2.0) was applied to the dataset (67 variables and 52 samples) using MATLAB (Jaumot et al., 2005, 2015; Tauler, 1995). The MCR-ALS method is based on the matrix equation to decompose the initial matrix D (normalized dataset) into a reduced number of components. The output gives: C (a matrix with sample scores for each component), ST (a matrix with compound loadings for each component; profiles) and E (a matrix with residual non-explained data) The decomposition was performed under non-negativity constraints, which provide physically interpretable results and are more realistic for environmental data. The number of components was selected based on the interpretability of their chemical profiles in terms of emission sources and atmospheric processes.

Compared with other source apportionment approaches, such as Chemical Mass Balance (CMB), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), or Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF), MCR-ALS offers several advantages. CMB requires predefined source profiles and cannot resolve unknown sources, while PCA enforces orthogonality, which limits environmental interpretability. Both MCR-ALS and PMF apply non-negativity constraints and yield comparable results, but they differ in their optimization algorithms and normalization procedures (Tauler et al., 2009). Importantly, MCR-ALS does not impose orthogonality between components, allowing for overlapping explained variance that better reflects the reality of atmospheric sources, which are rarely independent. Previous studies have demonstrated the robustness of this method for source apportionment of air pollutants and organic aerosols (Jaén et al., 2021b, 2023; van Drooge et al., 2022).

3.1 Automatic data and air mass origin

The temporal evolution of potential temperature (θ) provides insight into the vertical mixing and stability of the atmosphere at the sampling sites. During both campaigns, θ exhibited similar trends at both altitudes (Fig. S4 in the Supplement). During the day, temperature and relative humidity (RH) remained comparable at the two sites, indicating that they were within the convective mixing layer of the urban airshed. Temperature peaks at the elevated site were slightly delayed relative to the city site, reflecting the progressive growth of the mixing layer in the hours following sunrise. At night, more pronounced variantion in temperature and RH were observed between the two sites, suggesting that the elevated site become partially decoupled from the urban airshed. Generally, θ was higher at the elevated site at night, consistent with the development of stable atmospheric conditions and temperature inversions. This day-night dynamic was also reflected in variations of wind speed and direction, showing similar patterns during the day but becoming stronger and originating from a different direction at the elevated site during the night compared to the city site (Fig. S4).

Regarding the air quality parameters, ozone exhibited a clear day-night contrast between sites. During the day, O3 concentrations were all well correlated between the city site and the elevated site (r2=0.7) (Figs. S4 and S5 in the Supplement), reflecting a well-mixed urban atmosphere. At night, this correlation weakened substantially, indicating a decoupling of the elevated site from the urban airshed. O3 concentrations remained consistently high at the elevated background site throughout both day and night (78±15 µg m−3), while at the city site, O3 exhibited a diurnal oscillation peaking during sunlight hours (47±19 µg m−3). These observations are consistent with previous studies in the same sampling sites across different seasons (Dall'Osto et al., 2013) and suggest that differences in oxidant distribution along the vertical column may influence the organic composition at the studied altitudes. The nitrogen oxides also showed substantial correlations between sites during the day, although always higher in the city, but they were uncorrelated at night (Figs. S4 and S5). Their diurnal trends at the city site were strongly linked to traffic emissions, with pronounced peaks in the early morning and late afternoon (up to 107 µg m−3) but those high concentrations reached the elevated site only under mixing conditions of the atmosphere (25±19 µg m−3 city site; 10±10 µg m−3 elevated site). PM10 had moderate correlations between sites during both periods of the day (r2=0.32–035, Figs. S4 and S5) and the overall concentration trends remained similar (18±7 µg m−3 city site; 16±7 µg m−3 elevated site), although the slightly higher warm-period PM10 at the elevated site may be another indication for variations in their organic composition.

The 5 clusters of 48 h-backward trajectories for both sampling periods resolved with the HYSPLIT clustering algorithm are showed in Fig. S3b. The first (warm) sampling period was dominated by southerly trajectories (red cluster) and trajectories coming from the east (dark blue cluster). Both clusters have their origins in the Mediterranean Sea indicting regional recirculation. The end of this period was dominated by northerly trajectories coming from the European continent (light blue cluster). This change in the air mass origin from regional to continental was reflected in the air quality (Fig. S4) involving a reduction of NO, NO2 and PM10 peaks when the air was from the north. In these conditions, the differences in O3 between both sampling sites were reduced. In the second (cold) sampling campaign, all trajectories reached Barcelona from the north, the first period coming more directly from the Atlantic Ocean (green cluster) while trajectories coming from the gulf of Lion were observed in the last sampling days (pink cluster). This change was again reflected in lower pollutant concentrations at the end of the campaign.

3.2 Organic aerosol composition

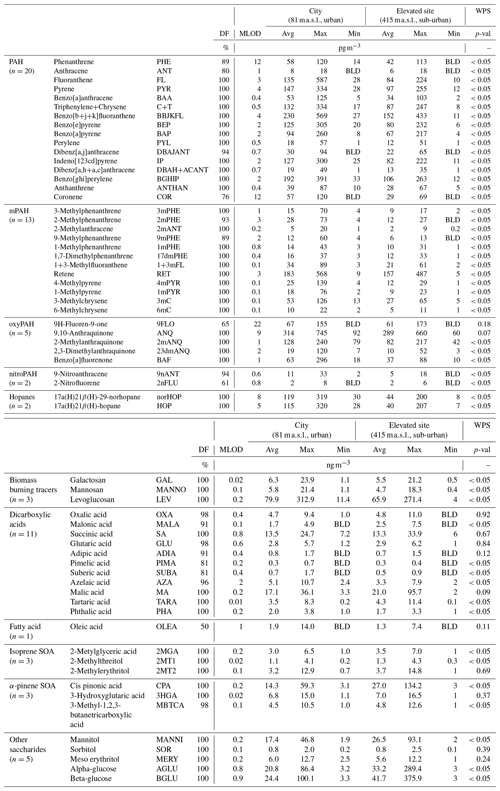

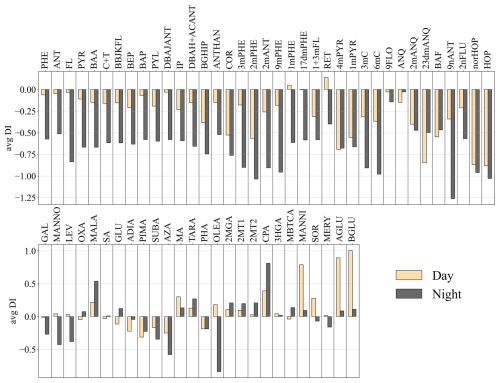

Table 1 shows detection frequencies (DF), MLOD, average, maximum and minimum concentrations at the city and elevated background sites and p-values for the Wilcoxon test for paired samples (WPS) between both sites, and average day and nighttime concentrations are given in Table S1 in the Supplement. The magnitude of these differences between sites are evaluated by calculating the Decreasing Index for each compound in each pair of samples as following: ; where i is the specific pair of samples, and n the total number of samples. The average DIs for day and night samples are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2Average decreasing indexes (DI) for day and night sampling periods. Negative DI indicate higher concentration at the city site. Abbreviations are defined in Table 1.

The average concentrations of individual PAHs ranged from 8 to 230 pg m−3 at the city site and from 6 to 152 pg m−3 at the elevated site. These compounds are generated by incomplete combustion, mainly from biomass and fossil fuels. Their concentrations were higher in the city site compared to the elevated site (p<0.05). Similar trends were observed for the methyl-PAHs which are usually emitted alongside PAHs under relatively low temperature combustion conditions. The average levels of individual methyl-PAHs varied between 5 and 183 pg m−3 at the city site and between 2 and 157 pg m−3 at the elevated site. Retene (RET), which is an indicator of pinewood combustion in the absence of coal combustion (Bi et al., 2008; Ramdahl, 1983; Shen et al., 2012), was the more abundant methyl-PAH, with similar concentrations as predominant unsubstituted PAHs (pyrene (PYR), benzofluoranthenes (BBJKFL) and benzo[ghi]perylene (BGHIP)), which suggests contribution of pinewood combustion in the sites, since there is no coal combustion in the region (van Drooge and Grimalt, 2015).

As regards to oxygenated PAHs, the average concentrations of the individual compounds ranged from 19 to 314 and from 10 to 289 pg m−3 at the city and elevated sites, respectively. The most abundant compound was 9,10-anthraquinone (ANQ) followed by 2-methylanthraquinone (2mANQ) and fluoren-9-one (9FLO), which have been associated with several primary combustion emissions, but also to secondary transformation processes, such as the reaction of anthracene and fluorene with OH, NOx or O3 (Keyte et al., 2013; Kojima et al., 2010; Oda et al., 1998; Rogge et al., 1993). The fact that their concentrations are similar at both sites suggest that secondary formation processes contribute substantially to their presence. In contrast, the other oxyPAH are significantly higher in concentration at the city level, indicating stronger influence of local primary emissions.

The two nitro derivatives of PAHs reported in this study exhibited relatively low concentrations, but with higher 9-nitroanthracene concentration in the city site than the elevated site (11 and 5 pg m−3, respectively). These compounds can be primary emitted from combustion sources, but also formed from anthracene reactions in the presence of NOx (Bandowe et al., 2014; Saldarriaga et al., 2008), and their significant higher concentrations in the city site indicates a priory a dominant influence of primary emissions over formation processing.

In almost all cases, the decreasing indexes of PAHs and derivatives were negatives for both day and night periods agreeing with higher concentrations at the city level (Fig. 2). However, the DIs were more accentuated for nighttime samples, up to −1.3, indicating larger differences between sites at night when air masses are disconnected.

Hopanes are related to traffic emissions for their presence in lubricant oils, although they are also emitted through coal combustion (Bi et al., 2008; Schauer et al., 2007). In the present study, hopanes are traffic markers due to the absence of coal combustion in the studied region, and they showed an average concentration of 117 pg m−3 at the city site and 42 pg m−3 at the elevated site (Table 1), with negative DIs for both day and night samples (Fig. 2).

The anhydro-saccharides galactosan (GAL), mannosan (MANNO) and levoglucosan (LEV) are marker compounds of biomass burning (Simoneit, 2002). They showed predominance of LEV, with average concentrations at the city and elevated sites of 80 and 66 ng m−3, respectively. The concentrations in the cold period (up to 300 ng m−3) were ten times higher than the warm period, which is similar to results in previous studies in the urban area of Barcelona (Reche et al., 2012; van Drooge et al., 2018). Nighttime DIs were around −0.4, indicating an accumulation of these combustion products in the city while they were close to 0 or positive during the day, pointing to vertical mixing in the urban airshed (Fig. 2). The substantial concentrations of these biomass combustion markers at the elevated site at nighttime in the cold period suggest an influence of local emissions besides and influence of recirculation of biomass burning aerosols (BBOA) in the region.

The 12 dicarboxylic acids (DCA) that were analysed in this study show different trends than the combustion products mentioned before. The C2–C9 linear homologues, two hydroxylated compounds (malic acid (MA) and tartaric acid (TARA)) and phthalic acid (PHA) are mainly formed through photochemical reactions of VOCs from natural and anthropogenic primary emission sources such as vehicular exhaust, food cooking, or biogenic emissions (Cao et al., 2017; Kunwar and Kawamura, 2014; Lui et al., 2023; Rogge et al., 1991; Xu et al., 2020). Their average individual concentrations span from 0.3 to 17 ng m−3 at the city site and from 0.3 to 21 ng m−3 at the elevated site. Malonic acid and tartaric acid were higher at the elevated site, while pimelic, suberic, azelaic and phthalic acids were more abundant at the city site. In previous studies, these later longer chained C7–C9 DCAs had higher concentrations in an intensive traffic site in the populated city centre and were linked to the oxidation of unsaturated carboxylic acids, such as oleic acid (Alier et al., 2013; Kawamura and Gagosian, 1987). Other dicarboxylic acids, such as succinic acid, glutaric acid, and phthalic acid did not show statistically significant differences in concentration between the two sites.

Secondary organic aerosol markers from biogenic volatile compounds, i.e. isoprene (methyltetrols (MT) and 2-methyl glyceric acid (MGA)) and α-pinene (cis-pinonic acid (CPA), 3-methyl butane tricarboxylic acid (MBTCA) and 3-hydroxyglutaic acid (HGA)) oxidation products (Claeys et al., 2004, 2007; Szmigielski et al., 2007), ranged from 1 to 14 ng m−3 at the city site and from 1 to 27 ng m−3 at the elevated site. Their concentrations were around ten times higher in the warm period compared to the cold period, relating these compounds to the period with highest biogenic (vegetation) activity and photo-chemical reactions. Higher levels were observed at the elevated site compared to the city site, with the largest difference for CPA which was also the most abundant one. CPA is a fresh SOA from α-pinene oxidation product while 3HGA and MBTCA are further oxidation products (Claeys et al., 2007; Szmigielski et al., 2007). CPA decreasing index was 0.4 for daytime samples and 0.8 for nighttime samples, suggesting further oxidation of CPA in the city compared to the elevated site. This may be related to enhanced formation of aged pinene SOA in the presence of NOx from traffic emissions as has been observed in previous studies in the urban background in Barcelona (Alier et al., 2013; Minguillón et al., 2016; van Drooge et al., 2018). On the other hand, the presence of pine forests in the Collserola hills may also be a potential source for α-pinene emissions and CPA formation.

Lastly, other biogenic saccharides were also determined in this study which can be related to fungal sporulation (mannitol (MANNI) and sorbitol (SOR)), pollen grain and organic soil dust (glucoses (AGLU and BGLU) and meso-erythritol (MERY)) which are relevant in the PM coarse fraction (Bauer et al., 2008; Burshtein et al., 2011; Jia and Fraser, 2011; Medeiros and Simoneit, 2008; Simoneit et al., 2004). Their individual average levels ranged between 1 and 24 ng m−3 in the city site and between 1 and 42 ng m−3 at the elevated site. Generally, they showed higher concentrations at the elevated site agreeing with the higher density of vegetation in this site compared to the city site. However, this difference was only significant for MANNI, AGLU and BGLU which showed high positive DIs during the day (0.8–1; Fig. 2).

Table S2 in the Supplement compares the concentrations of the studied compounds at both sites and campaigns with similar studies in the region in urban, sub-urban, rural, industrial, and high-altitude areas. In general, the levels of the studied compounds were in the range of these former studies in terms of location and season. In particular, the concentration of combustion markers (biomass burning markers, PAHs and derivatives) in the cold period campaign were similar to urban and sub-urban sites in cold periods, but lower than those registered in rural areas with local biomass burning emission sources. The hopanes were lower than recorded in suburban, industrial and traffic sites under stagnant atmospheric conditions, while the biogenic SOA marker concentrations were lower than those observed in rural sites.

Regarding nitro-PAHs, few studies report their PM concentrations in southern Europe. In fact, the only measurements in ambient air in Barcelona were those by Bayona et al. (1994), conducted at heavily trafficked sites. They reported considerably higher concentrations of 9-nitroanthracene and 2-nitrofluorene than those observed in the present study, a pattern also reflected in the parent PAHs. In contrast, the oxy-PAH ANQ, which was also measured in that study, was found at lower concentrations. Studies conducted in European cities during the early 2010s similarly reported higher nitro-PAH concentrations than those observed here, particularly in winter (Alam et al., 2015; Alves et al., 2017; Tomaz et al., 2016), whereas more recent studies on the Iberian Peninsula reported comparable levels (Lara et al., 2022). Although further measurements are necessary, reduction of nitro-PAHs concentrations may be attributable to reductions in NO2 emissions over the past decade, resulting from the implementation of low-emission zones and cleaner vehicle engines, which have decreased atmospheric formation of nitro-PAHs while potentially enhancing oxy-PAH formation through reactions with O3.

3.3 Apportionment of sources and atmospheric processes

The multi-variant analysis by MCR-ALS was applied on the joined dataset, and included the organic markers in PM10 samples, as well as the average concentrations of the air quality parameters NO, NO2, O3, and PM10 for the sample periods. This was done in order to study the similarities and differences among the quantified compounds and sampled sites and to identify the most significant sources and atmospheric processes influencing air quality in the sites without pretending to be a mass balance for PM, or the organic aerosol. The analysis resolved six components based on their chemical composition in relation to their environmental interpretability. Those components explained 95 % of the variance in the dataset. The components are represented in Fig. 3 showing the loadings of each compound in each component (bars) and the percentage of the compound present in the specific component as the proportion of the compound along all components (purple dots). Moreover, Fig. 4 shows the score of the resolved components in each sample. The six components are as follows:

Figure 3MCR-ALS compound loadings (bars) for all components of the multivariate analysis. Purple dots show the percentage of the compound in a specific component in relation to all components. Abbreviations of compounds are defined in Table 1.

Figure 4MCR-ALS component scores for the two sampling periods at both sampling sites. Dashed lines indicate the start and end of weekends. Yellow and grey shadowed areas indicate day and night samplings, respectively.

3.3.1 Diurnal traffic

The first component (18 % of explained variance) accounted for a high percentage of the loadings of traffic markers, such as NO (62 % of total NO loadings), hopanes (50 %), and NO2 (36 %), but moderated contribution of PAHs (10 %) and mPAH (20 %; excluding RET). Longer-chained dicarboxylic acids such as PHA, AZA, SUBA, PIMA and ADIA, as well as oxygenated PAHs 2mANQ, 23dmANQ and BAF, and 2-nitrofluorenone (46 %), were also represented in this component (Fig. 3). These compounds can originate directly from traffic emission sources but are also related to fast oxidation of traffic related VOCs and those from food cooking during atmospheric transport (Alier et al., 2013). The highest scores of this component were found in the city site during daytime, which is consistent with the urban inputs and photo-chemical reactions, and SOA formation. This component probably resolves part of the fresh urban inputs (traffic and cooking), since an important time frame of the traffic rush hours and cooking period peak are during the nighttime period (Fig. S4). Nevertheless, other sources, such as those from the harbour area could also be involved, since they are usually characterized by elevated concentrations of NO2, but also SO2. Barcelona harbour is situated in the southern coast (Fig. S1) and winds from the sea can transport these emissions towards the city site, which is probably the case in the first days of the warm period campaign. Figure S2 shows that during the day wind comes predominantly from the south, indicating an inland transport of the visible pollution from the harbour (photos in Fig. S6 in the Supplement). This is also supported by the SO2 peaks observed at the city site (Fig. S2) during daytime sampling in both sampling campaigns. The harbour contributions mixed with secondary compounds in the city of Barcelona were also previously described using the organic and inorganic fractions of PM1 where they encountered SOA compounds mixed with metals as V, Ni and secondary inorganic compounds as and NH4+ (Brines et al., 2019).

3.3.2 Nocturnal traffic

The second component (13 % of the explained variance) had the highest loadings for the methylphenanthrenes (51 % of the total loadings of methylphenanthrenes) and 2mANT (66 %). The occurrence of these compounds in urban areas is usually related with fossil fuel emissions, particularly from diesel engines (Casal et al., 2014), pointing to a traffic emission related component. It had higher scores at nighttime (Fig. 4) which may partially be the morning rush hour traffic, which explains the high loadings of PAHs (25 %), hopanes (19 %), NO2 (32 %), NO (21 %) and methylchrysenes (31 %) (Fig. 3). Moreover, PAH derivatives, ANQ, 2mANQ and 9nANT also have high loadings in this component in agreement with previous studies that linked them to traffic sources (Oda et al., 1998; Saldarriaga et al., 2008).

Consistent with traffic emission origin, this component was higher in the city site than in the elevated site. Besides the early morning rush-hour contribution, this component may reflect various activities that involve traffic emissions, such garbage collection, street cleaning and transport of goods during the nighttime with trucks. The high NO and NO2 loadings in this component further support this association. It is worth noting that the Low Emission Zone regulations in Barcelona are valid on working days from 07:00 a.m. to 08:00 p.m. (LT), allowing the more polluting vehicles (old diesel vehicles) to circulate at night in the city. Moreover, this component had the highest scores on the four first nights when the air masses were indicating more stagnant conditions. The lowest scores were observed during weekends, when vehicle movements are reduced, reinforcing the association of this component to traffic.

3.3.3 Biomass burning

The third component (40 % of total variance) contained 82 % of the biomass burning markers (GAL, MANNO, LEV) and other combustion indicators, such as 46 % of the PAHs and 34 % of the mPAHs, including 79 % of the pinewood burning marker RET (Fig. 3). Biomass burning is the main source for toxic PAHs, such as benzo[a]pyrene in the two background sites. It also substantially consists of oxy-PAHs, 9FLO, ANQ, BAF (24 %–40 %) and 9nANT (32 %) which could be directly emitted from biomass combustion, or other sources, or formed after oxidation of parent PAHs during atmospheric transport. However, there are very low loadings of other SOA markers, such as dicarboxylic acids and phthalic acid, suggesting that this component consists mainly of fresh biomass burning organic aerosols (BBOA) (Chuesaard et al., 2014; Medeiros and Simoneit, 2008).

Previous studies conducted in the urban area of Barcelona have always attributed BBOA to regional atmospheric transport to city of Barcelona by land breezes through the surrounding river valleys during nighttime, essentially in winter (Alier et al., 2013; Brines et al., 2016; Reche et al., 2012; van Drooge et al., 2018). In agreement with these previous studies, biomass burning in the present study was almost exclusively related to the cold period (Fig. 4), aligning with dominant contributions from domestic heating, and regional contributions from agricultural residue burning in fields, allowed in this Mediterranean region from mid-October to mid-March. Figure 4 shows that the score values for BBOA in the cold period were similar among the samples in the two background sites, although higher scores were obtained in the city site during the nighttime, evidencing that this introduction of biomass burning aerosols into the urban airshed, possibly by the land breezes or by direct contributions from the outskirts of the city. Local nighttime contributions may also influence the elevated site, since the score values in this site do not decrease substantially with respect to daytime levels (Fig. 4). At night, the two air masses were physically separated due to a low boundary layer, so the similar score values indicate fresh biomass burning emissions. A separate multi-variant analysis of the two datasets of the sites did not change the composition or intensity of the loadings and scores, neither could any further component be resolved dividing fresh from aged biomass burning aerosols. This indicates that biomass burning is probably a very substantial emission source in urban and sub-urban backgrounds within the metropolitan area of Barcelona during the cold period, and the main source of toxic PAHs, such as benzo[a]pyrene (Fig. 4).

3.3.4 Biogenic

The fourth component (14 %) was mainly composed by biogenic organic aerosol markers, such as those from organic soil dust and detritus (alpha and beta glucoses, 96 % and 97 %) and fungal spores (mannitol, sorbitol and meso-erythritol, 59 %, 42 % and 40 %, respectively) as well as high loadings from the isoprene oxidation products (49 %), malic acid (50 %) and succinic acid (31 %; Fig. 3). Therefore, it is representing biogenic POA, with influence of SOA. Beside the presence of methyltetrols, short-chained dicarboxylic acids may be due to the oxidation of isoprene, which has been observed in laboratory and field studies (Altieri et al., 2008; Bikkina et al., 2021) through aqueous-phase reactions (Ervens et al., 2011).

The scores of this component have a clear seasonality with high score values in the warm period (Fig. 4). Moreover, in this period, scores are similar in the two sites except in the daytime sample from 3 May in the elevated site, which may be due to the short rain episode on this day (Fig. S4). High relative humidity conditions are associated with higher levels of pollen (Gosselin et al., 2016; Rathnayake et al., 2017), which may be captured in this sample.

3.3.5 Regional secondary

The fifth component (29 % of explained variance) is dominated by secondary organic compounds, such as dicarboxylic acids (39 %) and biogenic SOA compounds (2MGA, 2MT1, 2MT2, 3HGA and MBTCA; 37 %) (Fig. 3). This component is related to aged SOA that recirculates in the regional atmosphere, with substantial chemical loadings of PM10 (16 %) and ozone (29 %). This component is dominant in the samples from the warm period, consistently with higher biogenic VOC emission, higher temperatures and solar radiation (Fig. S4).

The higher score values were observed on days with continental air masses (Fig. S3b) supporting a regional origin of this aged secondary component. In general, the score values in the two sites followed similar trends (Fig. 4). However, during the day, mixing was more uniform in the urban airshed, while at night, scores were higher at the elevated site, indicating either faster depletion in the city, or long-range atmospheric transport and formation within the ozone reservoir above the urban airshed (Jaén et al., 2021a).

3.3.6 Fresh secondary

The sixth component (16 %) had high loadings of cis-pinonic acid (84 %) and O3 (52 %) (Fig. 3). This component was generally more abundant at the elevated site, where the sampling station has pine forest nearby and, therefore, α-pinene and its oxidation derivative, CPA (Fig. 4). The higher abundance of this component in the winter campaign may be explained by lower humidity, which may preserve CPA over long time periods before transformation into further oxidation products, as has been observed in previous studies in the city (van Drooge et al., 2018).

This component was more abundant in the cold period campaign following an opposite trend than the above-described Regional secondary component that dominated in the warm period. In the elevated site, the Fresh secondary component was predominant in the daytime samples, which is in agreement with favoured photochemical reactions and nucleation processing (Alier et al., 2013; Dall'Osto et al., 2013). However, the high scores also observed at night indicate a conservation of this aerosol and ozone in the upper layers.

3.4 Source contributions and seasonal variability

As expected, NO and NO2 were highly represented in the traffic components, comprising 83 % and 68 % of the total loadings of these compounds, respectively. O3 was related with secondary components, 52 % and 29 % for the fresh and regional, respectively. PM10 was represented in multiple components, namely secondary (45 %) but also traffic (22 %) and Biomass Burning (17 %).

The highest PAH loading (46 %) was related to biomass burning component which contrasts with observations one decade ago that attributed these pollutants to traffic emissions (Alier et al., 2013; van Drooge et al., 2018). Although these previous studies also included urban traffic sites, a general decrease of benzo[a]pyrene has been observed in the Air Quality network with a 73 % reduction in urban traffic sites between period 2010–2015 and period 2020–2023, compared to a smaller decrease of 28 % in urban background sites. This change reflects improvement in engine efficiency of motorized vehicles and the traffic restrictions in the low emission zone, in combination with an increase of biomass burning emissions during the past decade in the background sites. In contrast, the sum of the two traffic components represents the highest loadings of the PAHs derivatives, they account for the 56 % of mPAH (excluding RET), the 46 % of oxyPAHs and the 62 % of nitro-PAHs. In fact, the individual oxidized compounds show some significant differences in their abundances among the components. The more volatile oxyPAHs, 9FLO and ANQ, are probably mainly secondary, formed with the Fresh secondary aerosol formation while 23dmANQ and BAF are associated with the diurnal traffic. For the nitro-PAHs, 2nFLU is probably secondary formed after diurnal traffic emissions (46 %) while 9nANT is predominantly related to nocturnal traffic (51 %).

The polar fraction, excluding saccharides, is related with the secondary and biogenic components. In particular, most of the DCA and oleic acid have a regional origin, 39 % and 43 %, respectively, while biogenic SOA compounds (isoprene and α-pinene SOA) are more uniformly distributed between the non-combustion sources. Finally, the glucoses and fungal markers have almost solely relevant loadings from the biogenic component with percentages from 42 % to 97 % in this component.

The relative contribution from each component to the sum of scores varied significantly by season, site and period of the day (Fig. S7 in the Supplement). During the warm campaign, traffic-related components dominated at the city site, contributing 40 % during the day and 49 % at night, though regional contributions were also substantial (29 % day; 36 % night). In contrast, at the elevated site, traffic contributions were lower during the day (17 %) and nearly absent at night (4 %), with the Regional Secondary component becoming dominant (35 % day; 67 % night). The biogenic POA component was also relevant, particularly at the elevated site (32 % day; 13 % night) compared to the city site (18 % day; 10 % night). On the other hand, in the cold period, biomass burning become the dominant component in all cases, especially at night. At the city background site, it accounted for 56 % of the scores during the day and 72 % at night, those percentages contributions to the OA are similar than those observed in OA source apportionment studies in Barcelona and Madrid (van Drooge et al., 2018). A similar dominance was observed at the elevated site, where it accounted for 57 % of the scores during the day and 62 % at night, highlighting the influence of biomass burning in urban background areas with an implication of local sources. The Fresh secondary component also had relevant contributions to the sum of scores during the cold campaign, particularly at the elevated site (30 % day; 22 % night) although it was also important in the city site during the day (19 %).

3.5 Altitudinal distribution of OA

Significant correlations (p<0.01) between score values in the samples from the urban background site at city level and the elevated site were observed for Biomass burning, Regional secondary and Biogenic components (r2=0.86, 0.89 and 0.56, respectively; Fig. S8 in the Supplement) with similar score values at both sites which suggests vertical and horizontal mixing, or local primary emissions, such is the case of nighttime biomass burning emissions in the elevated site. The Diurnal traffic component was also significantly correlated between sites (r2=0.71), but shows 3 times higher scores at the city site compared to the elevated site (Fig. S8). The Fresh secondary also showed good correlation between sites (r2=0.42) but with higher scores at the elevated site, especially when the scores were low in the city site (Fig. S8). This behaviour indicates a common influence between the two sites for the distribution of these pollutants but pointing to specific sources and processes for their origin, e.g., Diurnal traffic in the city and Fresh secondary related to nucleation at the elevated site.

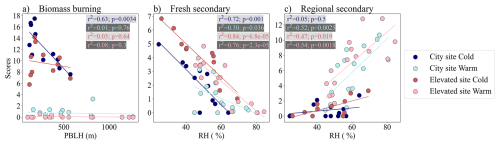

On the contrary, the Nocturnal traffic component does not show a significant correlation between sampling sites with substantial higher scores at the city site. This decoupled behaviour between altitudes suggests the accumulation of this traffic related component in the nocturnal urban atmosphere in absence of turbulent mixing in nighttime period. The score values of the biomass burning in the urban area at city level in the cold period were anti-correlated with the planetary boundary layer height (PBLH; r2=0.63; p=0.003; Fig. 5). This anti-correlation was not observed at the elevated site, and suggest local emissions in the elevated site, and input of biomass burning emissions and accumulation in the urban airshed for the city site.

3.6 SOA formation mechanisms

The Fresh secondary component was significantly anti-correlated with relative humidity in all cases (Fig. 5). These correlations evidenced the importance of low RH in the formation through nucleation and conservation of fresh SOA (Brines et al., 2019; van Drooge et al., 2022). The chemical compounds involved in the formation of this fresh SOA likely result from reaction with O3, which is also dominantly present in this component. On the other side, the formation of the secondary compounds present in the diurnal and nocturnal traffic components could be more related with the oxidation with the NO2 as evidenced by the presence of nitro-PAHs in these components.

Contrarily to Fresh secondary, the Regional secondary component was significantly correlated with relative humidity in the city site in the warm period and elevated site in both periods (Fig. 5). The formation of the chemical compounds contributing to this SOA component involved aqueous-phase oxidation under high relative humidity. The formation of SOA compounds from biogenic VOCs is influenced by multiple factors, including atmospheric conditions, aerosol acidity, and the presence of oxidants such as NO2 (Surratt et al., 2010). Unlike Fresh and Regional secondary components, individual SOA compounds from isoprene oxidation do not exhibit significant correlations with RH (Fig. S9 in the Supplement) which is characteristic of non-acidic conditions (Nestorowicz et al., 2018) and aligning with the little influence of RH in isoprene SOA yields (Dommen et al., 2006). However, their relative composition () shows an anticorrelation with ambient humidity with independence from site and sampling periods, suggesting that different isoprene SOA formation pathways dominate under varying RH conditions. Similarly, the correlation of isoprene SOA compounds with NO2 is significant only for samples from the city site during the spring campaign, where concentrations decrease with increasing NO2 (Fig. S10 in the Supplement). Notably, the ratio exhibits opposite trends with NO2 in the warm and cold campaigns. In the warm campaign, higher ratios are observed with increasing NO2, aligning with literature that describes the preferential formation of 2-methylglyceric acid under high NOx conditions (Surratt et al., 2010). In contrast, during the cold campaign, the ratio decreases as NO2 levels rise.

For α-pinene SOA, the observed trends resemble those of the Fresh and Regional components, with increased aged-to-fresh ratios () under higher RH conditions (Fig. S9). In contrast, NO2 shows a negative correlation with this ratio only in the city site during the warm campaign (Fig. S10).

These opposite trends of individual SOA compounds with RH and NO2 may suggest a relatively minor contribution from local biogenic SOA formation and a greater influence from regional transport. In fact, notable differences in SOA concentrations and relative abundances are observed under different air mass regimes (Fig. S11 in the Supplement), which also reflect variations in RH. Isoprene SOA concentrations are higher in samples influenced by Mediterranean (Regional) and Continental air masses (dark blue and light blue clusters, Fig. S3b).

The molecular analysis of organic compounds in PM10 at two altitudes in Barcelona allowed a description of the POA distribution, the discernment of different SOA formation pathways and an assessment of their impacts upon the air quality in the city complementing previous studies in the area. Of all 68 analysed organic molecular markers, the biomass burning markers, hopanes and PAHs, and most of their derivatives were significantly higher in the urban background site at city level (81 ), the dicarboxylic acids were not clearly related with a specific site while the biogenic compounds were more abundant at the elevated site (415 ).

The bilinear decomposition of the combined dataset (organic compounds with NO, NO2, O3 and PM10) with the MCR-ALS algorithm resolved 6 components that explained 95 % of the variance of the dataset. Those components were; (1) Diurnal traffic, with high loadings of the traffic markers (hopanes), NOx, and a contribution from harbour emissions, (2) Nocturnal traffic, related with gasoline and diesel combustion emissions, (3) Biomass Burning, containing levoglucosan and PAHs, (4) Biogenic, with primary and secondary biogenic compounds, (5) Regional secondary, with high contributions of aged SOA and (6) Fresh secondary mainly composed of cis-pinonic acid that could be related to new particle formation.

The main contribution to the parent PAHs was from biomass burning while many PAH derivatives were associated with the traffic components. However, some particular cases are of especial relevance as 9-fluoreneone and 9,10-anthraquinone appeared to be mainly secondary, formed with the Fresh secondary component, and 2-nitrofluoranthene which was part of the SOA formed from diurnal traffic emissions in the urban airshed. On the other hand, despite in urban areas usually being more associated with primary emissions, the dicarboxylic acids present in Barcelona were essentially due to recirculation of the regional air masses. As a consequence, SOA was more abundant at the elevated site while aerosols from traffic emissions were more abundant at the lower city level. Nocturnal traffic aerosols were more abundant in nighttime samples at the city site indicating an accumulation of these emissions in the urban airshed.

All component's score values showed good correlations between sites except for Nocturnal traffic evidencing disconnected air masses at both altitudes during nighttime periods, confirmed by different wind directions. Biomass burning was detected in higher abundance during the cold period, and at similar levels the two background sites, indicating local emissions in the elevated site as well as an accumulation of biomass burning aerosols in the city site during nighttime.

The relationship with atmospheric variables revealed different SOA formation mechanisms. The Fresh secondary component was temperature dependent in all sites and was enhanced under drier conditions, pointing to nucleation processing. On the contrary, the Regional secondary component, including isoprene and aged α-pinene showed positive correlations with relative humidity suggesting an aquatic phase oxidation.

Data visualization was performed with the open-source programming language Python (version 3.12). MCR-ALS code is available at https://mcrals.wordpress.com/ (last access: 27 October 2023).

Automatic air quality data are publicly available at https://analisi.transparenciacatalunya.cat/Medi-Ambient/Qualitat-de-l-aire-als-punts-de-mesurament-autom-t/tasf-thgu/about_data (last access: 24 March 2024). Meteorological data are publicly available at https://analisi.transparenciacatalunya.cat/Medi-Ambient/Dades-meteorol-giques-de-la-XEMA/nzvn-apee/about_data (last access: 24 March 2024). Organic molecular data are available upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-18389-2025-supplement.

CJ: Sampling, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review and Editing; MU: Methodology, Writing – Review and Editing; RH: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review and Editing; JOG: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing – Review and Editing; BLVD: Sampling, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review and Editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Acknowledgments to Roser Chaler and Alexandre Garcia for GC-MS technical assistance, and to Alfons Puertas for technical assistance at the Fabra Observatory.

This research has been supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (grant nos. PGC2018-102288-B-I00, PID2022-140392OB-I00 and FPU 19/06826) and the HORIZON EUROPE Health (grant no. HORIZON-HLTH-2021-ENVHLTH-03: 101057014).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).

This paper was edited by Marco Gaetani and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ajuntament de Barcelona: Vehicle park 2020: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/estadistica/catala/Estadistiques_per_temes/Transport_i_mobilitat/Mobilitat/Vehicles/Parc_de_vehicles/a2020/index.htm, last access: 15 May 2024.

Alam, M. S., Keyte, I. J., Yin, J., Stark, C., Jones, A. M., and Harrison, R. M.: Diurnal variability of polycyclic aromatic compound (PAC) concentrations: Relationship with meteorological conditions and inferred sources, Atmos. Environ., 122, 427–438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.09.050, 2015.

Alier, M., van Drooge, B. L., Dall'Osto, M., Querol, X., Grimalt, J. O., and Tauler, R.: Source apportionment of submicron organic aerosol at an urban background and a road site in Barcelona (Spain) during SAPUSS, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 10353–10371, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-10353-2013, 2013.

Altieri, K. E., Seitzinger, S. P., Carlton, A. G., Turpin, B. J., Klein, G. C., and Marshall, A. G.: Oligomers formed through in-cloud methylglyoxal reactions: Chemical composition, properties, and mechanisms investigated by ultra-high resolution FT-ICR mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ., 42, 1476–1490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.11.015, 2008.

Alves, C. A., Vicente, A. M., Custódio, D., Cerqueira, M., Nunes, T., Pio, C., Lucarelli, F., Calzolai, G., Nava, S., Diapouli, E., Eleftheriadis, K., Querol, X., and Musa Bandowe, B. A.: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives (nitro-PAHs, oxygenated PAHs, and azaarenes) in PM2.5 from Southern European cities, Sci. Total Environ., 595, 494–504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.256, 2017.

Atkinson, R.: Atmospheric chemistry of VOCs and NOx, Atmos. Environ., 34, 2063–2101, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00460-4, 2000.

Bandowe, B. A. M., Meusel, H., Huang, R. jin, Ho, K., Cao, J., Hoffmann, T., and Wilcke, W.: PM2.5-bound oxygenated PAHs, nitro-PAHs and parent-PAHs from the atmosphere of a Chinese megacity: Seasonal variation, sources and cancer risk assessment, Sci. Total Environ., 473–474, 77–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.11.108, 2014.

Bauer, H., Claeys, M., Vermeylen, R., Schueller, E., Weinke, G., Berger, A., and Puxbaum, H.: Arabitol and mannitol as tracers for the quantification of airborne fungal spores, Atmos. Environ., 42, 588–593, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2007.10.013, 2008.

Bayona, J. M., Casellas, M., Fernández, P., Solanas, A. M., and Albaigés, J.: Sources and seasonal variability of mutagenic agents in the Barcelona city aerosol, Chemosphere, 29, 441–450, https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-6535(94)90432-4, 1994.

Bi, X., Simoneit, B. R. T., Sheng, G., and Fu, J.: Characterization of molecular markers in smoke from residential coal combustion in China, Fuel, 87, 112–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2007.03.047, 2008.

Bikkina, S., Kawamura, K., Sakamoto, Y., and Hirokawa, J.: Low molecular weight dicarboxylic acids, oxocarboxylic acids and α-dicarbonyls as ozonolysis products of isoprene: Implication for the gaseous-phase formation of secondary organic aerosols, Sci. Total Environ., 769, 144472, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144472, 2021.

Brines, M., Dall'Osto, M., Amato, F., Cruz Minguillón, M., Karanasiou, A., Alastuey, A., and Querol, X.: Vertical and horizontal variability of PM10 source contributions in Barcelona during SAPUSS, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 6785–6804, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-6785-2016, 2016.

Brines, M., Dall'Osto, M., Amato, F., Minguillón, M. C., Karanasiou, A., Grimalt, J. O., Alastuey, A., Querol, X., and van Drooge, B. L.: Source apportionment of urban PM1 in Barcelona during SAPUSS using organic and inorganic components, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Re., 26, 32114–32127, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06199-3, 2019.

Burshtein, N., Lang-Yona, N., and Rudich, Y.: Ergosterol, arabitol and mannitol as tracers for biogenic aerosols in the eastern Mediterranean, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 829–839, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-829-2011, 2011.

Cao, F., Zhang, S. C., Kawamura, K., Liu, X., Yang, C., Xu, Z., Fan, M., Zhang, W., Bao, M., Chang, Y., Song, W., Liu, S., Lee, X., Li, J., Zhang, G., and Zhang, Y. L.: Chemical characteristics of dicarboxylic acids and related organic compounds in PM2.5 during biomass-burning and non-biomass-burning seasons at a rural site of Northeast China, Environ. Pollut., 231, 654–662, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.045, 2017.

Casal, C. S., Arbilla, G., and Corrêa, S. M.: Alkyl polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons emissions in diesel/biodiesel exhaust, Atmos. Environ., 96, 107–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.07.028, 2014.

Chen, J. and Hoek, G.: Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Environ. Int., 143, 105974, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVINT.2020.105974, 2020.

Chuesaard, T., Chetiyanukornkul, T., Kameda, T., Hayakawa, K., and Toriba, A.: Influence of biomass burning on the levels of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their nitro derivatives in Chiang Mai, Thailand, Aerosol Air Qual. Res., 14, 1247–1257, https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2013.05.0161, 2014.

Ciccioli, P., Silibello, C., Finardi, S., Pepe, N., Ciccioli, P., Rapparini, F., Neri, L., Fares, S., Brilli, F., Mircea, M., Magliulo, E., and Baraldi, R.: The potential impact of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) from terrestrial vegetation on a Mediterranean area using two different emission models, Agric. For Meteorol., 328, 109255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2022.109255, 2023.

Claeys, M., Graham, B., Vas, G., Wang, W., Vermeylen, R., Pashynska, V., Cafmeyer, J., Guyon, P., Andreae, M. O., and Artaxo, P.: Formation of secondary organic aerosols through photooxidation of isoprene, Science, 303, 1173–1176, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1092805, 2004.

Claeys, M., Szmigielski, R., Kourtchev, I., der Veken, P., Vermeylen, R., Maenhaut, W., Jaoui, M., Kleindienst, T. E., Lewandowski, M., Offenberg, J. H., and Edney, E. O.: Hydroxydicarboxylic acids: Markers for secondary organic aerosol from the photooxidation of α-pinene, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 1628–1634, https://doi.org/10.1021/es0620181, 2007.

Dall'Osto, M., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Minguillon, M. C., Alier, M., Amato, F., Brines, M., Cusack, M., Grimalt, J. O., Karanasiou, A., Moreno, T., Pandolfi, M., Pey, J., Reche, C., Ripoll, A., Tauler, R., Van Drooge, B. L., Viana, M., Harrison, R. M., Gietl, J., Beddows, D., Bloss, W., O'Dowd, C., Ceburnis, D., Martucci, G., Ng, N. L., Worsnop, D., Wenger, J., Mc Gillicuddy, E., Sodeau, J., Healy, R., Lucarelli, F., Nava, S., Jimenez, J. L., Gomez Moreno, F., Artinano, B., Prévôt, A. S. H., Pfaffenberger, L., Frey, S., Wilsenack, F., Casabona, D., Jiménez-Guerrero, P., Gross, D., and Cots, N.: Presenting SAPUSS: Solving Aerosol Problem by Using Synergistic Strategies in Barcelona, Spain, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 8991–9019, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-8991-2013, 2013.

Derstroff, B., Hüser, I., Bourtsoukidis, E., Crowley, J. N., Fischer, H., Gromov, S., Harder, H., Janssen, R. H. H., Kesselmeier, J., Lelieveld, J., Mallik, C., Martinez, M., Novelli, A., Parchatka, U., Phillips, G. J., Sander, R., Sauvage, C., Schuladen, J., Stönner, C., Tomsche, L., and Williams, J.: Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in photochemically aged air from the eastern and western Mediterranean, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 9547–9566, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-9547-2017, 2017.

Dommen, J., Metzger, A., Duplissy, J., Kalberer, M., Alfarra, M. R., Gascho, A., Weingartner, E., Prevot, A. S. H., Verheggen, B., and Baltensperger, U.: Laboratory observation of oligomers in the aerosol from isoprene/NOx photooxidation, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L13805, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026523, 2006.

Ervens, B., Turpin, B. J., and Weber, R. J.: Secondary organic aerosol formation in cloud droplets and aqueous particles (aqSOA): a review of laboratory, field and model studies, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 11069–11102, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-11069-2011, 2011.

Fontal, M., van Drooge, B. L., López, J. F., Fernández, P., and Grimalt, J. O.: Broad spectrum analysis of polar and apolar organic compounds in submicron atmospheric particles, J. Chromatogr. A, 1404, 28–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2015.05.042, 2015.

García-Dalmau, M., Udina, M., Bech, J., Sola, Y., Montolio, J., and Jaén, C.: Pollutant Concentration Changes During the COVID-19 Lockdown in Barcelona and Surrounding Regions: Modification of Diurnal Cycles and Limited Role of Meteorological Conditions, Boundary Layer Meteorol., 183, 273–294, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-021-00679-1, 2021.

Garland, R. M., Yang, H., Schmid, O., Rose, D., Nowak, A., Achtert, P., Wiedensohler, A., Takegawa, N., Kita, K., Miyazaki, Y., Kondo, Y., Hu, M., Shao, M., Zeng, L. M., Zhang, Y. H., Andreae, M. O., and Pöschl, U.: Aerosol optical properties in a rural environment near the mega-city Guangzhou, China: implications for regional air pollution, radiative forcing and remote sensing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 5161–5186, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-8-5161-2008, 2008.

Generalitat de Catalunya: Air Quality of the automatic measuring points of the Atmospheric Pollution Monitoring and Forecasting Network: https://analisi.transparenciacatalunya.cat/Medi-Ambient/Qualitat-de-l-aire-als-punts-de-mesurament-autom-t/tasf-thgu/about_data, last access: 25 March 2024a.

Generalitat de Catalunya: Meteo data of XE M.: https://analisi.transparenciacatalunya.cat/Medi-Ambient/Dades-meteorol-giques-de-la-XEMA/nzvn-apee/about_data, last access: 25 March 2024b.

Gosselin, M. I., Rathnayake, C. M., Crawford, I., Pöhlker, C., Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J., Schmer, B., Després, V. R., Engling, G., Gallagher, M., Stone, E., Pöschl, U., and Huffman, J. A.: Fluorescent bioaerosol particle, molecular tracer, and fungal spore concentrations during dry and rainy periods in a semi-arid forest, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 15165–15184, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-15165-2016, 2016.

Harrison, R. M.: Airborne particulate matter, Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 378, 20190319, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2019.0319, 2020.

Jaén, C., Udina, M., and Bech, J.: Analysis of two heat wave driven ozone episodes in Barcelona and surrounding region: Meteorological and photochemical modeling, Atmos. Environ., 246, 118037, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.118037, 2021a.

Jaén, C., Villasclaras, P., Fernández, P., Grimalt, J. O., Udina, M., Bedia, C., and van Drooge, B. L.: Source apportionment and toxicity of PM in urban, sub-urban, and rural air quality network stations in Catalonia, Atmosphere, 12, 744, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12060744, 2021b.

Jaén, C., Titos, G., Castillo, S., Casans, A., Rejano, F., Cazorla, A., Herrero, J., Alados-Arboledas, L., Grimalt, J. O., and van Drooge, B. L.: Diurnal source apportionment of organic and inorganic atmospheric particulate matter at a high-altitude mountain site under summer conditions (Sierra Nevada; Spain), Sci. Total Environ., 905, 167178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167178, 2023.

Janssen, N. A. H., Fischer, P., Marra, M., Ameling, C., and Cassee, F. R.: Short-term effects of PM2.5, PM10 and PM2.5−10 on daily mortality in the Netherlands, Sci. Total Environ., 463–464, 20–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.05.062, 2013.

Jaumot, J., Gargallo, R., De Juan, A., and Tauler, R.: A graphical user-friendly interface for MCR-ALS: A new tool for multivariate curve resolution in MATLAB, Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst., 76, 101–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemolab.2004.12.007, 2005.

Jaumot, J., de Juan, A., and Tauler, R.: MCR-ALS GUI 2.0: New features and applications, Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst., 140, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemolab.2014.10.003, 2015.

Jia, Y. and Fraser, M.: Characterization of saccharides in size-fractionated ambient particulate matter and aerosol sources: The contribution of primary biological aerosol particles (PBAPs) and soil to ambient particulate matter, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 930–936, https://doi.org/10.1021/es103104e, 2011.

Jimenez, J. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Donahue, N. M., Prevot, A. S. H., Zhang, Q., Kroll, J. H., DeCarlo, P. F., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Ng, N. L., Aiken, A. C., Docherty, K. S., Ulbrich, I. M., Grieshop, A. P., Robinson, A. L., Duplissy, J., Smith, J. D., Wilson, K. R., Lanz, V. A., Hueglin, C., Sun, Y. L., Tian, J., Laaksonen, A., Raatikainen, T., Rautiainen, J., Vaattovaara, P., Ehn, M., Kulmala, M., Tomlinson, J. M., Collins, D. R., Cubison, M. J., E., Dunlea, J., Huffman, J. A., Onasch, T. B., Alfarra, M. R., Williams, P. I., Bower, K., Kondo, Y., Schneider, J., Drewnick, F., Borrmann, S., Weimer, S., Demerjian, K., Salcedo, D., Cottrell, L., Griffin, R., Takami, A., Miyoshi, T., Hatakeyama, S., Shimono, A., Sun, J. Y., Zhang, Y. M., Dzepina, K., Kimmel, J. R., Sueper, D., Jayne, J. T., Herndon, S. C., Trimborn, A. M., Williams, L. R., Wood, E. C., Middlebrook, A. M., Kolb, C. E., Baltensperger, U., and Worsnop, D. R.: Evolution of Organic Aerosols in the Atmosphere, Science, 326, 1525–1529, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1180353, 2009.

Kalnay, E., Kanamitsu, M., Kistler, R., Collins, W., Deaven, D., Gandin, L., Iredell, M., Saha, S., White, G., Woollen, J., Zhu, Y., Chelliah, M., Ebisuzaki, W., Higgins, W., Janowiak, J., Mo, K. C., Ropelewski, C., Wang, J., Leetmaa, A., Reynolds, R., Jenne, R., and Joseph, D.: The NCEP/NCAR 40-Year Reanalysis Project, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 77, 437–472, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>%2.0.CO;2, 1996.

Kawamura, K. and Gagosian, R. B.: Implications of ω-Oxocarboxylic acids in the remote marine atmosphere for photo-Oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, Nature, 325, 330–332, https://doi.org/10.1038/325330a0, 1987.

Keyte, I. J., Harrison, R. M., and Lammel, G.: Chemical reactivity and long-range transport potential of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons-a review, Chem. Soc. Rev., 42, 9333–9391, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cs60147a, 2013.

Kojima, Y., Inazu, K., Hisamatsu, Y., Okochi, H., Baba, T., and Nagoya, T.: Influence of secondary formation on atmospheric occurrences of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in airborne particles, Atmos. Environ., 44, 2873–2880, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.04.048, 2010.

Kunwar, B. and Kawamura, K.: Seasonal distributions and sources of low molecular weight dicarboxylic acids, ω-oxocarboxylic acids, pyruvic acid, α-dicarbonyls and fatty acids in ambient aerosols from subtropical Okinawa in the western Pacific Rim, Environ. Chem., 11, 673–689, https://doi.org/10.1071/EN14097, 2014.

Lara, S., Villanueva, F., Martín, P., Salgado, S., Moreno, A., and Sánchez-Verdú, P.: Investigation of PAHs, nitrated PAHs and oxygenated PAHs in PM10 urban aerosols. A comprehensive data analysis, Chemosphere, 294, 133745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133745, 2022.

Lida, G., David, S., Mark, G., Lawrence, B. W., Samuel, S., Raymond, K., and F, K. S.: The Association between Ambient Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Lung Cancer Incidence: Results from the AHSMOG-2 Study, Environ. Health Perspect., 125, 378–384, https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP124, 2017.

Lotteraner, C. and Piringer, M.: Mixing-Height Time Series from Operational Ceilometer Aerosol-Layer Heights, Boundary Layer Meteorol, 161, 265–287, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-016-0169-2, 2016.

Lui, K. H., Lau, Y. S., Poon, H. Y., Organ, B., Chan, M. N., Guo, H., Ho, S. S. H., and Ho, K. F.: Characterization of chemical components of fresh and aged aerosol from vehicle exhaust emissions in Hong Kong, Chemosphere, 333, 138940, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138940, 2023.

Malavelle, F. F., Haywood, J. M., Mercado, L. M., Folberth, G. A., Bellouin, N., Sitch, S., and Artaxo, P.: Studying the impact of biomass burning aerosol radiative and climate effects on the Amazon rainforest productivity with an Earth system model, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 1301–1326, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-1301-2019, 2019.

Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Stavropoulos, A., and Bezirtzoglou, E.: Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review, Front. Public Health, 8, 1, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00014, 2020.

Massagué, J., Contreras, J., Campos, A., Alastuey, A., and Querol, X.: 2005–2018 trends in ozone peak concentrations and spatial contributions in the Guadalquivir Valley, southern Spain, Atmos. Environ., 254, 118385, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118385, 2021.

Medeiros, P. M. and Simoneit, B. R. T.: Source profiles of organic compounds emitted upon combustion of green vegetation from temperate climate forests, Environ. Sci. Technol., 42, 8310–8316, https://doi.org/10.1021/es801533b, 2008.

Minguillón, M. C., Pérez, N., Marchand, N., Bertrand, A., Temime-Roussel, B., Agrios, K., Szidat, S., Van Drooge, B., Sylvestre, A., Alastuey, A., Reche, C., Ripoll, A., Marco, E., Grimalt, J. O., and Querol, X.: Secondary organic aerosol origin in an urban environment: Influence of biogenic and fuel combustion precursors, Faraday Discuss., 189, 337–359, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5fd00182j, 2016.

Murphy, D. M., Cziczo, D. J., Froyd, K. D., Hudson, P. K., Matthew, B. M., Middlebrook, A. M., Peltier, R. E., Sullivan, A., Thomson, D. S., and Weber, R. J.: Single-peptide mass spectrometry of tropospheric aerosol particles, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 111, D23S32, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD007340, 2006.

Myhre, G., Berglen, T. F., Johnsrud, M., Hoyle, C. R., Berntsen, T. K., Christopher, S. A., Fahey, D. W., Isaksen, I. S. A., Jones, T. A., Kahn, R. A., Loeb, N., Quinn, P., Remer, L., Schwarz, J. P., and Yttri, K. E.: Modelled radiative forcing of the direct aerosol effect with multi-observation evaluation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 1365–1392, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-1365-2009, 2009.

Nestorowicz, K., Jaoui, M., Rudzinski, K. J., Lewandowski, M., Kleindienst, T. E., Spólnik, G., Danikiewicz, W., and Szmigielski, R.: Chemical composition of isoprene SOA under acidic and non-acidic conditions: effect of relative humidity, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 18101–18121, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-18101-2018, 2018.