the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Pathway-specific responses of isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol formation to anthropogenic emission reductions in a megacity in eastern China

Huilin Hu

Yunyi Liang

Ting Li

Yongliang She

Yao Wang

Ting Yang

Min Zhou

Chenxi Li

Huayun Xiao

Jianlin Hu

Isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol (iSOA) represents a major biogenic source of atmospheric OA, with its formation strongly influenced by anthropogenic emissions. However, long-term iSOA measurements in polluted urban regions remain scarce, limiting the understanding of anthropogenic influences on iSOA formation. In this study, field observations of iSOA were conducted in Shanghai, China during summers and winters of 2015, 2019, and 2021, aiming to assess the iSOA response to emission reductions over this period. The particulate iSOA tracers, formed via reactive uptake of isoprene-derived epoxides, were measured by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. After accounting for the measurement uncertainties, both total iSOA and organosulfates (OSs) tracers (including 2-methyltetrol sulfates and 2-methylglyceric acid sulfate) decreased annually, while summertime polyol tracers like 2-methyltetrols (2-MTs) and 2-methylglyceric acid (2-MG) varied insignificantly despite strong NOx reductions. Declining aerosol reactivity toward isoprene-derived epoxides and reduced atmospheric oxidizing capacity drove the decrease in OSs but could not explain the trend of summertime polyols. Simulations with the Community Multiscale Air Quality model in 2015 and 2019 captured the decrease in total iSOA and OSs, confirming a driving role of chemical processes. However, the model failed to replicate relatively stable polyol levels in summer, suggesting additional factors (e.g., potential unaccounted sources of 2-MTs and methacrolein, the precursor to 2-MG) may buffer their variations. These findings highlight pathway-specific iSOA responses to emission reductions in a megacity and the importance of targeted anthropogenic emission reductions for mitigating biogenic SOA formation through regulating atmospheric oxidizing capacity and aerosol reactivity.

- Article

(3441 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1794 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Isoprene (2-methyl-1,3-butadiene, C5H8), mainly emitted by terrestrial vegetation, represents the largest source of atmospheric non-methane hydrocarbons, with a global emission flux of 500–750 Tg yr−1 (Guenther et al., 2006). Because of its large abundance and high reactivity, the oxidation of isoprene contributes significantly to the formation of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) in the troposphere, estimated to 19.6 TgC yr−1 (Kelly et al., 2018). The formation chemistry of isoprene-derived SOA (iSOA) has been extensively studied in laboratory, field, and modelling studies, which have shown that anthropogenic pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO2, the precursor to particulate sulfate) play a crucial role in the formation of iSOA (Shrivastava et al., 2019).

Photooxidation is the dominant fate of isoprene in the atmosphere, during which the C=C bond of isoprene is initially attacked by OH radicals to produce an alkyl radical (Teng et al., 2017), followed by the formation of isoprene hydroxyperoxy radicals (ISOPO2) via oxygen addition (Surratt et al., 2010). The fate of ISOPO2 radicals depends on the environmental conditions. When the NOx level is sufficiently low (referred to as HO2-dominated conditions), ISOPO2 would mainly react with HO2 radicals to form hydroxyhydroperoxides (ISOPOOH) (Paulot et al., 2009). Further OH radical addition to ISOPOOH produces isomeric isoprene epoxydiols (IEPOX, trans-β-IEPOX: cis-β-IEPOX = 0.63:0.37) with a yield of ∼ 70 %–80 % (Paulot et al., 2009; Bates et al., 2014; St. Clair et al., 2016). The gaseous IEPOX can be taken up into aqueous aerosol and undergo acid-catalyzed reactions to form polyols, organosulfates (OSs), and oligomers (Hettiyadura et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2012; Surratt et al., 2010). Several constituents including 2-methyltetrols (2-MTs) and their oligomers, C5-alkene triols, methyl tetrahydrofurans, and 2-methyltetrol sulfates (2-MT-OS), which were extensively measured in both laboratory-generated and ambient SOA (Xu et al., 2015; Isaacman-VanWertz et al., 2016; Surratt et al., 2010; Surratt et al., 2007; Worton et al., 2013; Yee et al., 2020), have been employed as molecular tracers of SOA derived from reactive uptake of IEPOX (IEPOX-SOA).

When the NOx level is high (referred to as NOx-dominated conditions), ISOPO2 would preferentially react with NO, producing unsaturated carbonyls such as methacrolein (MACR) and methyl vinyl ketone (MVK). A large fraction (∼ 45 %) of MACR can be further oxidized by OH radicals via aldehydic H-abstraction, followed by oxygen addition to form an acylperoxy radical, MACRO2 (Orlando et al., 1999). Subsequent reaction between MACRO2 and NO2 yields MPAN, which was proposed to form hydroxymethyl methyl-α-lactone (HMML) or methacrylic acid epoxide (MAE) (Lin et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2015). Both of these two epoxides can undergo heterogeneous acid-catalyzed reactions to form 2-methylglyceric acid (2-MG) as well as its oligoesters and sulfated derivatives (2-methylglyceric acid sulfate, 2-MG-OS), which serve as the molecular tracers of HMML&MAE-derived SOA (Kjaergaard et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2013).

In addition to altering the fate of RO2 (including ISOPO2 and MACRO2), NOx also plays an essential role in regulating atmospheric oxidizing capacity (e.g., the OH level), which governs the photooxidation rate of isoprene in the atmosphere. Compared to NOx that strongly affect the gas-phase oxidation chemistry of isoprene, sulfate aerosol mainly exerts influences on the multiphase chemistry of isoprene-derived epoxides. On one hand, sulfate serves as an important nucleophile in the reactive uptake of isoprene epoxides to form OSs, which competes with the reaction of epoxides with water (Lin et al., 2013). On the other hand, sulfate can alter the physicochemical properties of particles such as liquid water content (LWC), acidity, and phase state (Xu et al., 2016; Pye et al., 2017), which are the key factors influencing the multiphase reactivity of epoxides and the formation of iSOA.

Because of the complexity in the gas-phase and multiphase chemistry leading to iSOA formation, the product distribution of HO2- versus NOx-dominated pathways as well as their dependence on different influencing factors (i.e., NOx, sulfate, LWC, and aerosol acidity) varies significantly in different environments. A number of field measurements have found that the formation of IEPOX-SOA tracers was predominated over the HMML&MAE-SOA tracers, even in some NOx-rich urban areas (Zhang et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2008; Yee et al., 2020), while a few studies showed that the production of HMML&MAE-SOA was more prevalent, e.g., in Tianjin, China (Fan et al., 2020) and urban areas of California (Lewandowski et al., 2013). Sulfate was found to be the primary driver of isoprene-derived SOA in rural and urban regions as the iSOA correlated strongly with sulfate while such correlation did not occur with LWC and pH, e.g., in central Amazonia and southeastern US (Xu et al., 2015; Yee et al., 2020). It should be noted that significant uncertainties exist in the quantification of iSOA tracers in ambient aerosols due to the lack of authentic standards and/or the presence of measurement artifacts (e.g., matrix effects) (Fu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2008; Ding et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2020; Zhong et al., 2021). Furthermore, while the iSOA polyol tracers are formed in the particle phase, they can actively partition between gas and particle phases due to their semi-volatile characteristics (Fan et al., 2020; Isaacman-VanWertz et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2015). As a result, considering their particle-phase concentration only may bias our understanding of the atmospheric abundance and chemistry of iSOA.

In recent years, great changes have taken place in air pollutant emissions, atmospheric composition, and air quality in China due to the implementation of stringent clean air policies nationwide. For example, PM2.5 mass concentrations dropped significantly, with a notable reduction in inorganic water-soluble ions such as sulfate, ammonium, and cations (Liu et al., 2023a, b; Zheng et al., 2018; Geng et al., 2024), and a relatively small decrease in organic aerosol in eastern China in the past decade (Liu et al., 2023a; Yao et al., 2023). The reduction of inorganic ions including sulfate and non-volatile cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+) resulted in a significant decrease in LWC and a slight increase in aerosol acidity in this region (Zhou et al., 2022). However, concentrations of VOCs and ozone exhibited different trends, with a slight decrease for the former while the latter showing an upward trend before 2018 and a slight declining trend after 2018 (Wang et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023a; Yao et al., 2023; Gong et al., 2025). The changing atmospheric conditions can affect both gas-phase and particle-phase chemistry, as well as the gas-particle partitioning behavior of organics. However, how the formation of biogenic SOA, such as iSOA, respond to the changes in anthropogenic emissions and air pollution conditions in polluted regions remains poorly understood.

The aim of this study is to understand the atmospheric abundance and formation mechanisms of iSOA under the influence of continuous anthropogenic emission reductions in eastern China. Ambient PM2.5 samples were collected at an urban site in megacity Shanghai in winter and summer of 2015, 2019, and 2021. The concentrations of isoprene-derived polyols and OSs from both HO2- and NOx-dominated pathways in PM2.5 samples were measured using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), respectively, with the aid of a suite of authentic and surrogate standards. The quantification errors of iSOA tracers were evaluated and their gas-particle partitioning behaviors were considered. The relative distribution of measured iSOA tracers from different pathways as well as their inter-annual and seasonal variations were analyzed and compared to the calculated reaction efficiency of different pathways as well as the simulated values using the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model, which helps to constrain the formation mechanisms of iSOA and the key factors driving the inter-annual variation of iSOA tracers.

2.1 Sampling and Chemical Analysis

Ambient PM2.5 samples were collected on the rooftop of a 20 m tall teaching building at Xuhui Campus of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (31.201° N, 121.429° E) located in the urban center of Shanghai, China. The site is impacted by a mixed commercial and residential area. The sampling campaigns were conducted in summer (14 July to 9 August in 2015; 14 July to 9 August 2019; 7 July to 5 August 2021) and winter (6 January to 26 January 2016; 27 December 2018 to 16 January 2019; 22 December 2021 to 18 January 2022) of 2015, 2019, and 2021. Sampling started at 08:00 a.m. local time and lasted for 23 h. A total of 138 PM2.5 samples were collected on prebaked (550 °C, 6 h) quartz filters (18 × 23 cm2, Whatman) using a high-volume sampler (HiVol 3000, Ecotech) at a flow rate of 67.8 m3 h−1. All sampled filters were wrapped with prebaked aluminum foil and stored at −20 °C until analysis.

iSOA polyol tracers, included 2-MG, cis-2-methyl-1,3,4-trihydroxy-1-butene, trans-2-methyl-1,3,4-trihydroxy-1-butene, and 3-methyl-2,3,4-trihydroxy-1-butene (cis-2-MTB, trans-2-MTB, and 3-MTB, collectively named as C5-alkene triols), as well as 2-methylthreitol and 2-methylerythritol (collectively named as 2-MTs), were analyzed by a GC-MS. The details regarding the sample preparation and analysis protocol are presented in Section S1 in the supplement. An example of the total ion chromatograms (TIC) of iSOA polyol tracers is shown in Figure S1d. For iSOA polyol tracers, surrogate standards including erythritol, ketopinic acid, and glycerol were used for quantifications in a number of studies (Kang et al., 2018; Ding et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2020). In this study, concentrations of 2-MG and 2-methylerythritol were quantified using their authentic standards (Toronto Research Chemicals, 99.8 %), and C5-alkene triols and 2-methylthreitol were quantified by 2-methylerythritol. The uncertainty for C5-alkene triols was estimated previously and their concentration was found to be underestimated by 65 % when 2-methylerythritol was used as the surrogate standard (Frauenheim et al., 2022). Furthermore, the uncertainty of 2-methylthreitol quantified by 2-methylerythritol was assumed to be negligible as the differences in the TIC response for homologues are determined by carbon number, functional groups, and number of active hydrogen atoms that would silylate (Stone et al., 2012).

The particulate iSOA OSs were analyzed by a LC-MS employing a reversed-phase column (C18, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters). The sample extraction procedure and analysis protocol were described in detail in our previous work (Wang et al., 2021). A brief summary is given in Sect. S2 and examples of total and extracted ion chromatograms of iSOA OSs are provided in Fig. S1a–c. The lactic acid sulfate (LAS) was used as a surrogate standard to quantify the 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS. Use of surrogate standards would lead to uncertainties in measured concentrations of 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS (Bryant et al., 2020, 2021), but not alter the inter-annual trend of iSOA OSs.

2.2 Additional measurements and models

The concentrations of organic carbon (OC) and element carbon (EC) in filter samples were measured using a thermal–optical multiwavelength carbon analyzer (DRI, Model 2015). The concentration of organic mass (OM) was estimated by multiplying the OC by 1.6 (Tao et al., 2014). An ion chromatograph (Metrohm MIC) was employed to determine water-soluble inorganic compounds (e.g., sulfate, nitrate, chloride, ammonium, potassium ion, and calcium ion). Temperature, relative humidity (RH), as well as the concentrations of trace gases and PM2.5 were measured at a state-controlled air quality monitoring station on the Xuhui Campus of Shanghai Normal University, which is surrounded by residential areas and commercial districts and 4.5 km southwest of the PM2.5 sampling site of this work. The mean values of these meteorological parameters and pollutant concentrations are listed in Table S1 in the Supplement.

LWC, pH, and bisulfate concentration in aqueous aerosols were predicted by the ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic model (Wang et al., 2021). The molar concentrations of particulate water-soluble inorganic ions (including sulfate, nitrate, chloride, ammonium, potassium ion, and calcium ion), temperature, and RH were input into the model, which was run in the forward mode for metastable aerosols. As the predicted aerosol pH could be underestimated when using particle-phase concentrations of ion species as inputs only (Hennigan et al., 2015), we adopted the pH values of 2015 and 2019 at a nearby site reported by Zhou et al. (2022), who used both particulate inorganic ion concentrations and gaseous ammonia as inputs of ISORROPIA-II. Additionally, the 2021 pH was predicted by the ISORROPIA-II using particle-phase-only concentrations of ions as input due to lack of gas-phase NH3 data. Previous studies have found that lacking gas-phase inputs of ammonia could lead to under-prediction of pH using thermodynamic equilibrium models, such as ISORROPIA and E-AIM (Guo et al., 2015; Song et al., 2018; Hennigan et al., 2015). Guo et al. (2015) found that the pH values were underestimated by 1 unit on average in southeast US when using only aerosol ammonium data as inputs in ISORROPIA model. Similarly, Song et al. (2018) found that a 10-fold increase in gas-phase NH3 concentrations roughly corresponds to a 1 unit increase in pH in the ammonia-rich atmosphere like Beijing. In addition, we found that aerosol pH in 2015 and 2019 predicted using aerosol ammonium only as input in our study was on average 1 unit lower than that predicted using gas-plus-particle-phase ammonia as input in Zhou et al. (2022). Thus, we inferred that the lack of gas-phase concentrations of ammonia might lead to underestimation of pH by ∼ 1 unit in the present study and increased the output pH estimated using aerosol ammonium only as input by one unit to represent aerosol acidity in 2021.

In addition, considering that iSOA polyol tracers are semi-volatile and water-soluble, which can partition into OM or dissolve into aerosol liquid water, their gas-phase and particle-phase fractions were estimated by accounting for the gas-organic phase partitioning using an organic absorptive equilibrium partitioning model and the gas-aqueous phase partitioning using the Henry's Law. The details of the estimation method are described in Sect. S3.

2.3 Quality control and quality assurance

Procedural blanks (run every 6 samples) and field blanks (two for each season) were extracted and analyzed in the same manner as the PM2.5 filter samples. Target compounds were found below the detection limit in the blanks. The recovery of iSOA polyol tracers as represented by that of the internal standard (ketopinic acid) during GC-MS analysis was determined to be 85 ± 17 % and the recovery of iSOA OSs during LC-MS analysis was 72.5 %, as determined using LAS spiked onto the filter in our previous study (Wang et al., 2021).

As the PM2.5 sample extracts contain thousands of multifunctional compounds, there might exist a significant matrix effect in the analysis of iSOA tracers. The matrix effect of polyol tracers was evaluated by comparing the signal responses of authentic standards of 2-methylerythritol and 2-MG in PM2.5 extracts to those in pure solvent. Six filter samples representing low and high PM2.5 concentrations in summer and winter were used to test the matrix effect. 16 or 160 µL of 2-methylerythritol and 2-MG standard mixtures (10 ppm) was added to the filter extracts to represent the low and high concentrations of 2-methylerythritol and 2-MG in the samples. The filters were subsequently analyzed as described in Sect. 2.1. The matrix factors of the standards were calculated as the ratio of their signal response in sample extracts (the signal response of these species in non-spiked extracts was subtracted) to their signal response in the pure solvent. As shown in Table S2, 2-MG had a matrix factor of 0.77 ± 0.12, while that of 2-methylerythritol was 1.24 ± 0.08, indicating that the concentrations of 2-MG were likely underestimated by 23 % whereas 2-methylerythritol was overestimated by 24 % due to the matrix effect.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the concentrations of 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS were significantly underestimated due to matrix effect by using reversed phase liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (RPLC-MS) (Hettiyadura et al., 2015; Bryant et al., 2020, 2021). In the present work, because of lack of authentic standards of isoprene-derived OSs, we are not able to quantify the absolute value of underestimation in the concentration of 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS due to the matrix effect. However, using ambient PM2.5 samples with different concentrations, we can quantify the relative extent of underestimation in OS concentrations due to matrix effect in different samples, which allows for an evaluation of uncertainties in the abundance, trend, and relative ratios of different iSOA tracers in this study. In the matrix effect experiments, the extracts of ambient PM2.5 samples with different concentrations were mixed and the measured signals of 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS in mixed extracts were compared to the sum of OS signals detected separately in individual extracts. The concentrations of PM2.5, sulfate, as well as 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS in ambient samples used for this evaluation are listed in Table S3. The relative matrix effect factor (Fmatrix), defined as the ratio of the measured OS signals in mixed extracts to the sum of OS signals measured in each extract before mixing, are used to evaluate the matrix effect of OSs. A Fmatrix value of less than 1 indicates the presence of matrix effect.

As shown in Fig. S2, the Fmatrix values were significantly smaller than 1 in both summer and winter, indicating that the signal responses of 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS in mixed extracts were largely suppressed due to the matrix effect. Notably, Fmatrix exhibits a significant negative dependence on the reduced mass (μ, µg m−3), a proxy used to represent effective mass loadings of the mixed PM2.5 extracts, defined as:

where m1 and m2 are the PM2.5 mass loading of individual samples. This observation suggests that the concentrations of iSOA OSs in PM2.5 samples collected in 2015 were underestimated more than those in 2021, given that ambient PM2.5 concentrations declined by 39.8 % and 47.0 % from 2015 to 2021 in summer and winter, respectively.

As PM2.5 concentrations in ambient samples used for the matrix effect evaluation generally represent lower or upper ends of PM2.5 concentrations during the observation period (see Table S3), the relative differences in measured Fmatrix values at varying reduced mass (Fig. S2) may roughly reflect the differences in the extent of underestimation in OS concentrations for samples collected across 2015–2021. During summer, the Fmatrix value decreased from 0.71 to 0.63 for 2-MT-OS and from 0.85 to 0.58 for 2-MG-OS with increasing reduced mass, indicating that the concentrations of these two iSOA OSs were a factor of 1.2 and 1.5 more underestimated in 2015 than in 2021 due to matrix effect. Similarly, during winter the Fmatrix values of iSOA OSs decreased from 0.9 to 0.6 with rising reduced mass, implying a factor of 1.5 greater underestimation in OS concentrations in 2015 than in 2021.

2.4 Estimation of the reaction efficiency of isoprene-derived epoxides in aqueous aerosols

The IEPOX/HMML/MAE can undergo acid-catalyzed nucleophilic addition with water and sulfate to form polyol tracers (2-MTs and 2-MG) and OSs (2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS) in aqueous aerosols, respectively. The aqueous-phase pseudo-first-order rate constants (kaq, s−1) for epoxides could be estimated by Eq. (1) (Eddingsaas et al., 2010),

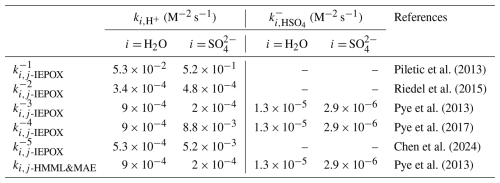

Where kij is the third-order reaction rate constant of isoprene-derived epoxides with nucleophile i (water or sulfate) and acid j (hydrogen ion or bisulfate) in the aqueous phase and the reported values of kij in previous studies are shown in Table 1. When epoxides react with water and sulfate, the aqueous-phase reaction rate constants ( and ) can be estimated by Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively.

where , , and are molar concentrations of hydrogen ion, bisulfate, and ALWC in aqueous aerosols, which were estimated by ISORROPIA-II model, and is the molar concentration of sulfate.

The reactive uptake coefficient (γ) of epoxides on aqueous aerosols is parameterized by a resistor model (Xu et al., 2016; Pye et al., 2013).

where rp is the particle radius. Previous work has found that the surface area (Sa, m2 m−3) and volume concentrations (Va, m3 m−3) of dry PM2.5 could be described as a function of PM2.5 mass concentration (, µg m−3) in Shanghai (, ) (Zang et al., 2022). In this study, the mean particle radius of dry PM2.5 was calculated as , which was then corrected for the aerosol hygroscopic growth to get the wet particle radius based on the κ-Köhler hygroscopicity function (see details in Sect. S4). α is the mass accommodation coefficient taking a value of 0.02 for both IEPOX and HMML&MAE (McNeill et al., 2012), ω is the mean molecular velocity of epoxides, Hepoxide is the Henry's law constant in the aqueous phase, with a value of 2.7 × 106 M atm−1 for IEPOX (Pye et al., 2013) and a constrained value of 7.5 × 106 M atm−1 for HMML&MAE by CMAQ in Case 1, and kaq is the first-order reaction rate constant in the aqueous phase (s−1), estimated using Eq. (1).

To describe the overall loss rate of gas-phase epoxides due to the reactive uptake by aqueous aerosols, the pseudo-first-order heterogeneous reaction rate constant was calculated by Eq. (8), when neglecting the gas-phase diffusion limitation:

2.5 Model Simulations

The CMAQ model (v5.2) was adopted to simulate the gas-phase concentration of isoprene and particulate concentrations of 2-MTs, 2-MG, and their OS derivatives formed involving the reactive uptake of IEPOX and HMML&MAE on aqueous aerosols (Pye et al., 2017) in both summer and winter of 2015 and 2019 in Shanghai. The simulations performed with the standard CMAQ v5.2 are referred to as the Base Case. While the advanced model simulations performed according to a recent study by Zhang et al. (2023) are named as Case 1. In this advanced case, the iSOA polyol tracers were treated as semi-volatile species that partition between gas, aqueous, and organic phases, while the OS tracers were treated as non-volatile species. The removal of iSOA polyol tracers by OH radicals in the gas and particle phases was also considered. The key parameters for simulating reactive uptake of IEPOX/HMML&MAE and the removal of 2-MTs and 2-MG in the gas phase and aqueous aerosol in the model are listed in Tables S4 and S5.

In this work, three nested domains covering mainland China, eastern China, and the Yangtze River Delta were configured with horizontal resolutions of 36 km × 36 km (d01), 12 km × 12 km (d02), and 4 km × 4 km (d03), as shown in Fig. S3. The outermost domain (d01) was driven by predefined initial and boundary conditions from CMAQ, with its outputs supplying these conditions for d02, which in turn provided them for d03. All domains employed a vertical structure consisting of 18 layers, extending from the surface to an altitude of 21 km.

Anthropogenic emissions were sourced from the Multi-resolution Emission Inventory for China (MEIC) version 1.4 for China (Geng et al., 2024) and the Regional Emission inventory in ASia (REAS) version 3.2.1 for other Asian countries and regions (Kurokawa and Ohara, 2020). Open biomass burning emissions were based on the Fire INventory from NCAR (FINN) version 2.5 (Wiedinmyer et al., 2023). Biogenic emissions were estimated using the Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN) version 2.1, incorporating the high-quality Leaf Area Index (HiQ-LAI) dataset developed by Yan et al. (2024), which enhances the spatiotemporal consistency of MODIS LAI products. Meteorology data was generated by the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model version 4.2.1 with initial and boundary conditions from the fifth generation ECMWF atmospheric reanalysis data (ERA5).

The simulation was conducted for four periods: 12 July–9 August 2015, 25 December 2015–16 January 2016, 4–26 January 2019, and 12 July–5 August 2019. The first two days of each period were treated as spin-up periods and excluded from the analysis.

3.1 Temporal evolution of major air pollutants during the observation period

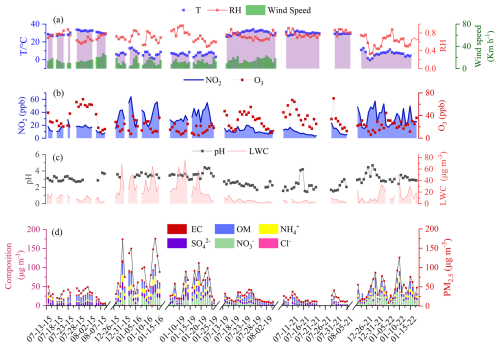

Time series of PM2.5 and its major components, as well as the major trace gases (NO2 and O3) and meteorological parameters during the observation period are shown in Fig. 1 and the seasonal and inter-annual variations of various pollutants are further demonstrated in Fig. 2. The concentration of NO2 exhibited an obvious downward trend, in particular in summer from 2015 to 2021, consistent with a strong reduction in anthropogenic emissions during this period. By contrast, the concentration of O3 significantly decreased from 52.0 ± 38.9 ppb in 2015 to 41.2 ± 22.8 ppb in 2019 (p<0.05) and then remained at a comparable level (43.4 ± 20.8 ppb) in 2021, suggesting a complex response of secondary O3 formation to primary emission reductions. During the observation period, the average PM2.5 concentration decreased by 41.7 % from 2015 to 2021, with concentrations of major components, including sulfate, ammonium, and OM, decreasing by 51.8 %, 40.6 %, and 39.1 %, respectively (Fig. 2). In contrast, the concentration of nitrate showed a slight upward trend during this period, in line with the measurement in urban Shanghai by Zhou et al. (2022). Overall, OM was the most abundant component in PM2.5, accounting for 10.2 %–72.7 % (average 22.6 %) of total PM2.5 mass, followed by sulfate (6.8 %–45.2 %, average 17.7 %), nitrate (0.5 %–32.6 %, average 17.0 %), and ammonium (1.1 %–18.2 %, average 8.8 %). Ascribed to the strong decrease of inorganic ion concentrations (in particular sulfate), aerosol LWC decreased from 9.14 ± 4.51 µg m−3 in 2015 to 4.40 ± 2.76 µg m−3 in 2021 (p<0.05). Aerosol pH decreased from 3.2 ± 0.4 in 2015 to 2.5 ± 0.9 in 2021 (p<0.05), which was mainly driven by the decrease of non-volatile cations during these years, though the decreased concentrations of sulfate had an opposite effect on aerosol acidity (Zhou et al., 2022).

Figure 1Temporal variations of (a) meteorological parameters (ambient temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed), (b) concentrations of NO2 and O3, (c) aerosol pH and liquid water content (LWC), and (d) concentrations of PM2.5 and its major components (OM, EC, sulfate, nitrate, chloride, and ammonium) in urban Shanghai during the observation period. The wind speed data were not collected during the observations in 2021.

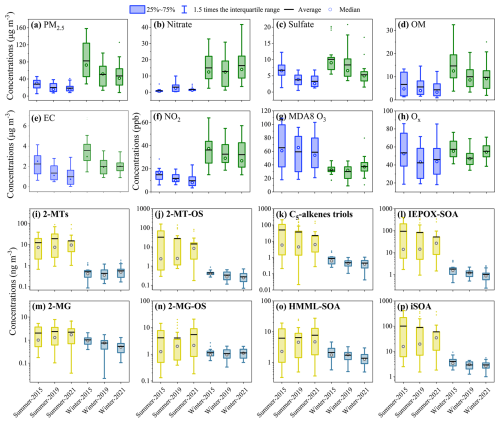

Figure 2Seasonal and inter-annual variations concentration of PM2.5 and its major components (a–e), gas-phase anthropogenic pollutants (f–h), as well as particulate iSOA tracers, including (i) 2-MTs, (j) 2-MT-OS, (k) C5-alkene triols, (l) IEPOX-SOA (the sum of 2-MTs, 2-MT-OS, and C5-alkene triols), (m) 2-MG, (n) 2-MG-OS, (o) HMML&MAE-SOA (2-MG plus 2-MG-OS), and (p) iSOA (the sum of all tracers).

3.2 Seasonal and annual variations of iSOA tracers

The measured concentrations of particulate iSOA tracers during the observation period are summarized in Fig. 2 and their specific concentration values are also provided in Table S1. Among the measured iSOA tracers, C5-alkene triols were the most abundant species with average concentrations of 27.6 ng m−3 in 2015, 20.9 ng m−3 in 2019, and 11.1 ng m−3 in 2021, accounting for 28.8 %, 22.4 %, and 18.7 % of the total iSOA mass, followed by 2-MT-OS, 2-MTs, 2-MG-OS, and 2-MG. However, the concentrations of C5-alkene triols might be overestimated since previous studies have reported that concentrations of C5-alkene triols could be artifacts of thermal degradation products of 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols and 2-MT-OS during GC-MS analysis (Cui et al., 2018; Frauenheim et al., 2022). Frauenheim et al. (2022) found that less than 15 % of 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols could transfer to two isomers of C5-alkene triols (cis-/trans-2-methyl-1,3,4-trihydroxy-1-butene). In the present study, using 2-methylerythritol as a surrogate standard, the concentrations of 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols were determined to be less than 5 % of C5-alkene triols in summer but had comparable concentrations to C5-alkene triols in winter. This result indicates that 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols was a minor contributor to C5-alkene triols in summer but an important source for C5-alkene triols in winter. In contrast, the contribution from the thermal degradation of 2-MT-OS might be more significant, though the specific contribution remains to be quantified; Cui et al. (2018) found that thermal degradation of 2-MT-OS could generate all three isomers of C5-alkene triols, while Yee et al. (2020) found that the thermal decomposition of 2-MT-OS could only produce one isomer, 3-methyl-2,3,4- trihydroxy-1-butene. Given these uncertainties, it is difficult to quantitatively evaluate the artifact formation of C5-alkene triols during GC-MS analysis. Therefore, the abundance and inter-annual trend of C5-alkene triols were not discussed in detail in the present work.

As shown in Fig. 2, the particle-phase concentrations of total and specific IEPOX-SOA tracers (except 2-MTs) decreased yearly in both summer and winter between 2015–2021 (Fig. 2a–d), while the particulate concentrations of total and specific HMML&MAE-SOA species did not show a significant inter-annual trend in summer during this period (Fig. 2e–g). However, the inter-annual trend of iSOA OSs could be altered due to the matrix effect. The measured concentration of 2-MT-OS exhibited a decreasing inter-annual trend, while 2-MG-OS showed insignificant variation between 2015–2021. Accounting for the significantly larger matrix effects in 2015 samples compared to 2021 samples (see Sect. 2.3), the true concentrations of 2-MT-OS would decrease more sharply and 2-MG-OS might also exhibit a declining trend. Recently, Frauenheim et al. (2024) demonstrated that gas-phase OH oxidation of 3-methylenebutane-1,2,4-triol (3-MBT) and 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols, formed from acid-catalyzed isomerization of IEPOX in aerosols, can yield 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS. However, in the present study, the gas-phase concentrations of 3-MBT and 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols were not measured, precluding a quantitative assessment of the contribution of their oxidation products to 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS. Given that IEPOX-SOA concentrations observed here exhibited a significant decreasing trend over the observation period, the concentrations of IEPOX isomerization products, such as 3-MBT and 3-methyltetrahydrofuran-2,4-diols, likely also decreased annually. Therefore, gas-phase OH oxidation of these species might represent a plausible contributor to the inter-annual decline in 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS.

The particulate concentrations of IEPOX-SOA (52.6 ± 97.6, 46.7 ± 103.8, and 25.8 ± 62.9 ng m−3 in 2015, 2019 and 2021, respectively) dominated over HMML&MAE-SOA (6.2 ± 6.4, 6.4 ± 7.0, and 7.7 ± 7.7 ng m−3) in summer, while they were comparable to HMML&MAE-SOA in winter. Although C5-alkene triols might be largely artifacts of GC-MS analysis (Cui et al., 2018; Frauenheim et al., 2022), the concentrations of IEPOX-SOA excluding C5-alkene triols were still dominant over HMML&MAE-SOA in summer. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that the concentrations of 2-MT-OS were underestimated more than 2-MG-OS by a factor of 5.7–9.1 in Beijing (Bryant et al., 2020) and 2.9 in Guangzhou (Bryant et al., 2021). If 2-MT-OS was also more significantly underestimated than 2-MG-OS in the present study, the predominance of IEPOX-SOA over HMML&MAE-SOA would be more pronounced. The dominance of IEPOX-SOA over HMML&MAE-SOA in summer is in agreement with RPLC-MS measurements in Beijing, Hefei, and Kunming in China (Zhang et al., 2022) and Birmingham, US (Rattanavaraha et al., 2016), as well as hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HILIC-MS) measurements conducted in urban Guangzhou, China (Liu et al., 2025).

The annual average particulate concentration of the total iSOA polyol tracers (including 2-MTs, 2-MG, and C5-alkene triols) were 36.1 ± 63.3, 33.4 ± 70.5, and 18.7 ± 47.1 ng m−3 in 2015, 2019 and 2021, higher than those of OS tracers (including 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS) by a factor of 2.5, 2.1, and 1.4, respectively. However, given the significant underestimation of iSOA OSs due to matrix effect and overestimation of C5-alkene triols due to their potential artifact formation, the true concentration of iSOA OSs would predominate over that of polyol tracers. The iSOA OSs prevailing over polyol tracers is consistent with urban observations using HILIC-MS, such as in Manaus, Brazil (Cui et al., 2018) and Guangzhou, China (Liu et al., 2025) (see Table S6). Using RPLC-MS, Bryant et al. (2020) also observed higher concentrations of iSOA OSs than polyol tracers in Beijing, China. Considering the potential underestimation of iSOA OSs due to matrix effect, the concentration of iSOA OSs would be even higher than that of polyol tracers in their study.

2-MTs exhibited a different inter-annual trend compared to other IEPOX-SOA tracers (Fig. 2i). A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that 2-MTs may have origins other than reactive uptake of IEPOX on aqueous aerosol. Previous studies have found that 2-methylerythritol, one isomer of 2-MTs, could be generated by biosynthetic pathways (Sagner et al., 1998; Lange et al., 2000). And the contributions of non-IEPOX pathway to 2-MTs concentrations were pH-dependent, accounting for 20 %–40 % in areas with aerosol pH < 2 and more than 70 % under less acidic conditions (pH ∼ 2–5) (Zhang et al., 2023). The contribution of biological emissions to 2-MTs might be important in Shanghai given its less acidic aerosol conditions (pH > 2). As a whole, the particulate concentrations of iSOA decreased significantly in both seasons from 2015 to 2021. In addition, all iSOA compound classes had substantially higher concentrations in summer than in winter. Such a strong seasonality in abundance is mainly driven by the higher temperature and stronger solar radiation, and thereby more intensive isoprene emissions and photochemistry in summer than in winter. Notably, HMML&MAE-SOA species exhibited a relatively smaller seasonal variation than IEPOX-SOA. This is partially owing to the fast thermolysis of methacryloyl peroxynitrate (MPAN) in summer, reducing the formation of HMML&MAE and thereby SOA (Worton et al., 2013).

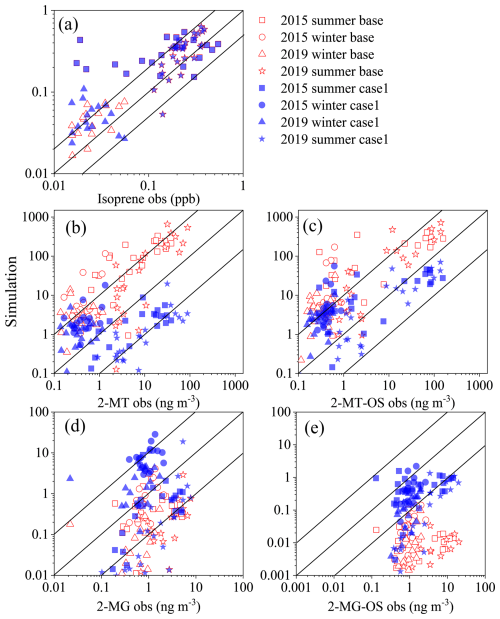

To further investigate factors that affect the abundance of iSOA, the particulate concentrations of 2-MTs, 2-MT-OS, 2-MG, and 2-MG-OS, as well as the gas-phase concentration of isoprene were simulated with the CMAQ model and compared to measurements in summertime and wintertime of 2015 and 2019 (see Fig. 3). Predicted concentrations of isoprene were generally consistent with observations with a median correlation (r2= 0.45), except in the summer of 2015, during which isoprene concentrations were significantly overestimated (Fig. 3a). For iSOA tracers, the Case 1 showed a better prediction than the Base Case. Overall, the simulated IEPOX-SOA tracers were biased low in summer, but biased high in winter (Fig. 3b and c). In contrast, the 2-MG and 2-MG-OS were biased low in both seasons (Fig. 3d and e). The underestimation of 2-MG is consistent with previous simulations at 14 sites across China in the summer of 2012 (Qin et al., 2018). Accounting for the underestimation of OSs due to the matrix effect, simulated concentrations of 2-MT-OS would be more biased low in summer but might be close to observations in winter. Similarly, the under-prediction of 2-MG-OS would be more significant in both seasons. The larger uncertainty of simulated HMML&MAE-SOA tracers compared to that of IEPOX-SOA might be attributed to the lack of well constrained kinetic parameters for reactive uptake of HMML and MAE. In addition, simulated concentrations of iSOA tracer species had decreasing inter-annual trend in both Base Case and Case 1 (Fig. S4), which was in agreement with observations of total iSOA, 2-MT-OS, and 2-MG-OS (with matrix effect considered), but not for 2-MG and 2-MTs. These results suggest that the major factors driving the overall formation and evolution of iSOA and in particular iSOA OSs were captured by the model, while some factors governing the abundance of 2-MG and 2-MTs might not be well represented in the model.

Figure 3Comparisons of simulations against observations for (a) isoprene, (b) 2-MTs, (c) 2-MT-OS, (d) 2-MG, (e) 2-MG-OS in summer and winter of 2015 and 2019. Red dot represents simulations with standard CMAQ v5.2 (Base Case), and blue represents simulations using the optimized model (Case 1). The 1:1, 10:1, and 1:10 lines are shown with solid lines.

The gas-phase and particle-phase fractions of 2-MG and 2-MTs were estimated using a chemical equilibrium partitioning model as described in Sect. S3 and the results are shown in Fig. S5. The particle-phase fraction (Fp) of 2-MG was highly variable, with a significant lower value in summer (9.0 %–19.0 %) than in winter (31.6 %–44.0 %), indicating substantial amounts of 2-MG was present in the gas phase in summer. Additionally, the Fp value of iSOA polyols, in particular for 2-MG, decreased yearly. As a result, the gas-plus-particle-phase concentrations of 2-MG showed an upward trend in summer from 2015–2021 (p<0.05, Fig. S5). In contrast, 2-MTs were mainly distributed in the particle phase with Fp values larger than 70 % in both seasons, consistent with previous measurements (Isaacman-VanWertz et al., 2016). The inter-annual trend of 2-MTs was not significantly affected by their gas-phase fraction because of the relatively low volatility. Overall, compared to other iSOA tracers in summer, 2-MG and 2-MTs exhibited a distinctly different inter-annual trend over 2015–2021. It should be noted that the use of surrogate standards would not alter the trend of iSOA tracers. The key factors driving such trends will be discussed in detail below.

3.3 Key influencing factors of iSOA formation

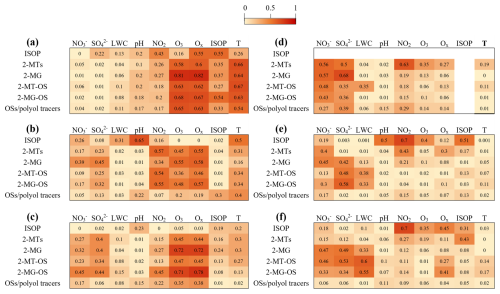

The production of iSOA can be influenced by a variety of factors such as the emission and concentration of isoprene, atmospheric oxidizing capacity as represented by the concentrations of O3 or odd oxygen (Ox= O3+ NO2), nitrogen oxides, as well as aerosol composition and properties including sulfate content, acidity, and LWC. Here, we identify the major influencing factors of IEPOX-SOA and HMML&MAE-SOA formation through the correlation analysis between different iSOA tracers and influencing factors (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Coefficients of correlation (r2) between iSOA compounds and various influencing factors of iSOA formation in (a–c) summer and (d–f) winter of 2015, 2019, and 2021, respectively. The ISOP is the abbreviation of isoprene.

The correlations of all iSOA species with isoprene were relatively weak, with most of the correlation coefficients (r2) below 0.37. Therefore, the decline in iSOA concentrations from 2015 to 2021 could not be attributed to the slight variation in isoprene concentration. The HMML&MAE-SOA species exhibited strong correlations with ozone (r2= 0.48–0.81) and Ox (r2= 0.57–0.82) in summer, in particular in 2015 and 2021 while exhibiting relatively weaker correlations with NO2 (r2= 0.20–0.55). Such correlations between 2-MG and ozone were also observed in previous measurements in urban areas in southeastern US (Rattanavaraha et al., 2016), which proposed that ozone might be a superior indicator to NOx for the photochemical process of isoprene under NOx-dominant conditions. The IEPOX-SOA tracers also correlated well with ozone (r2= 0.36–0.70) or Ox (r2= 0.40–0.68) in summer, despite less strongly than HMML&MAE-SOA species. These observations clearly suggest that atmospheric oxidation capacity (or the oxidation of isoprene to epoxide intermediates) plays a driving role in summertime iSOA formation. In addition, weak to moderate correlations (r2= 0.23–0.45) were observed between the iSOA tracers and sulfate aerosol in 2019 and 2021, indicating that sulfate aerosol also plays a role in controlling iSOA formation during these periods. In contrast, wintertime iSOA species exhibited weak correlations with O3 and Ox in all the three years (Fig. 4d–f). However, they all had moderate or strong correlations with sulfate aerosol (r2= 0.36–0.68) in 2015 and the iSOA OSs correlated moderately with sulfate (r2= 0.35–0.58) and LWC (r2= 0.34–0.58) in 2019 and 2021. These results suggest that sulfate-mediated heterogeneous chemistry of isoprene epoxide intermediates in aqueous aerosols is a key process controlling iSOA formation in winter (Surratt et al., 2010; Yee et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2012). A sensitivity test considering the measurement uncertainties of iSOA tracers did not significantly influence the correlation analysis results (see details in Sect. S5).

As shown in Table S1, the concentrations of sulfate aerosol and LWC both decreased drastically over 2015–2021 (p<0.05), which could explain the declining trend of iSOA in winter and partially contributed to the decreased formation of IEPOX-SOA in summer. Notably, the summertime average MDA8 (maximum daily 8 h average) O3 concentration at the observation site increased from 2015 to 2017 and then decreased significantly in 2018, followed by a slight increasing trend between 2018 and 2021 (Fig. S6). This inter-annual trend of O3 was similar to the trend of annual 90th percentile MDA8 O3 concentration in the region of Shanghai (Fig. S6). As a result, the summertime average MDA8 O3 concentration in 2015, 2019, and 2021 showed a slight downward trend. In addition, the simulated concentrations of OH radicals and ratios of (MVK + MACR)/isoprene both declined in 2019 compared to those in 2015 (see Table S8), indicating a decline in the atmospheric oxidation capacity during the observation period. Similarly, the nighttime atmospheric oxidation capacity as indicated by the production rate of NO3 radicals (PNO3), calculated by multiplying the reaction rate coefficient between NO2 and O3 by their concentrations (Wang et al., 2023), also decreased during this period (Fig. S7). The reduced atmospheric oxidation capacity further explained the decreased formation of iSOA OSs in summer during these years, but it could not explain the inter-annual variation in summertime 2-MG and 2-MTs, suggesting that other factors might have offset the anticipated decline in these polyols during this period.

3.4 Heterogeneous reactivity of ambient aerosols

To better understand the role of heterogeneous chemistry in the formation and inter-annual variations of iSOA, the reactive uptake coefficients (γEPOXIDE) of isoprene-derived epoxides on ambient aerosols were estimated by a resistor model (Eq. 5) (Xu et al., 2016; Pye et al., 2013). The pseudo-first-order heterogeneous reaction rate constant (khet, s−1) of gas-phase IEPOX and HMML&MAE could be then estimated from γEPOXIDE via Eq. (8). Currently, there are five sets of reported third-order reaction rate constants (i.e., ki,j in Eq. 1) for the acid-catalyzed nucleophilic addition of water and sulfate to IEPOX in the aqueous phase (Table 1). Piletic et al. (2013) predicted ki,j for IEPOX () with a computational model, which are two orders of magnitudes higher than the laboratory-measured values () by Riedel et al. (2015) and model-estimated values () using CMAQ by Pye et al. (2013). More recently, Pye et al. (2017) updated the values () by constraining the using measured 2-MT-OS/2-MTs in CMAQ and Chen et al. (2024) constrained reaction rate constant of IEPOX () using a phase-separation box model with chamber measurements. For HMML and MAE, there is a lack of direct measurements and theoretical calculations of their ki,j values. Pye et al. (2013) assumed the same ki,j values as IEPOX with of 9.0 × 10−4 M−2 s−1 for water and 2.0 × 10−4 M−2 s−1 for sulfate.

Table 1Third-order reaction rate constants of IEPOX and HMML&MAE with sulfate and water in the aqueous phase.

Firstly, the ki,j values of IEPOX and HMML&MAE were evaluated by comparing the measured ratios of 2-MT-OS/2-MTs and 2-MG-OS/2-MG with the calculated ratios of the pseudo-first-order rate constants for the nucleophilic addition reactions of epoxides with sulfate and water (). The results are shown in Figs. S8 and S9. For IEPOX, the ratios were close to measured particulate ratios of 2-MT-OS/2-MTs when using , , and suggested by Piletic et al. (2013), Pye et al. (2017), and Chen et al. (2024), respectively (Fig. S8). However, when taking into account the underestimation of 2-MT-OS due to matrix effect, all estimated ratios were lower than the measured values. Similarly, the calculated ratios for HMML and MAE were 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than the measured 2-MG-OS/2-MG ratios (Fig. S9) and such a discrepancy would be larger when considering the matrix effect of 2-MG-OS. This result indicates that the kij of isoprene-derived epoxides, particularly that of HMML and MAE, with sulfate was likely underestimated, since Pye et al. (2013) found their hydrolysis rate constant allowed a good prediction of the concentration of 2-MG.

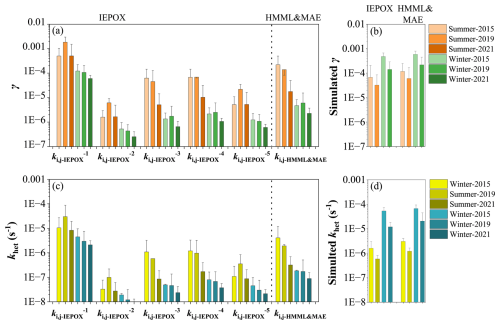

Figure 5 shows the γ and khet values for IEPOX and HMML&MAE estimated using different sets of kinetic parameters listed in Table 1. The CMAQ-modeled values are also displayed for comparison. The khet estimated by , and in summer had highest values in 2019. This might be attributed to the fact that these three sets of parameters lack the third-order reaction rate constant of IEPOX with nucleophiles catalyzed by bisulfate (Table 1). As a comparison, we calculated the khet of IEPOX and HMML&MAE excluding the reaction rate constant catalyzed by bisulfate using and (Fig. S10). We found that the inter-annual trend of IEPOX (Figure S10a) and HMML&MAE (Fig. S10b) in summer was altered and similar to that of IEPOX calculated by , and , while the inter-annual trend of khet in winter was not sensitive to the exclusion of reaction rate constant catalyzed by bisulfate. This result indicates a contribution of nucleophilic-addition of epoxides catalyzed by bisulfate to the heterogeneous reactivity. It also suggests that the is more appropriate for predicting aerosol heterogeneous reactivity toward IEPOX than other four sets of kinetic parameters.

Figure 5Reactive uptake coefficients (γ) and pseudo-first-order heterogeneous reaction rate constant (khet, s−1) of gas-phase IEPOX and HMML&MAE estimated using different sets of ki,j-IEPOX and ki,j-HMML&MAE listed in Table 1 (a and c) and simulated by CMAQ model in Case 1 (b and d).

As shown in Fig. 5a and c, the estimated γ and khet of IEPOX and HMML&MAE using and ki,j-HMML&MAE showed a similar trend which decreased in both winter and summer. Similar decreasing trends in γ and khet were also simulated by CMAQ (Fig. 5b and d). The calculated γ and khet values of IEPOX and HMML&MAE in summer using and ki,j-HMML&MAE, respectively, are consistent with the simulated results, while the calculated values in winter were significantly lower than the simulations, which is likely attributed to the significantly under-predicted aerosol pH and thereby over-predicted aerosol reactivity in winter by the model. Overall, the declining trend of both calculated and model-predicted khet offers an explanation for the decreasing trend of 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS in summer, but it could not explain the observed trend of 2-MG and 2-MTs in summer.

3.5 Meteorological influences on iSOA variation

As discussed above, the variations in chemical factors (including atmospheric oxidizing capacity and aerosol heterogeneous reactivity) could well explain the declining trend of both summertime and wintertime iSOA OSs, but not the trend of summertime 2-MG and 2-MTs during the period of 2015–2021. Since meteorological conditions could exert a significant influence on the concentrations of atmospheric pollutants (Liu et al., 2023b; Gu et al., 2023), we further investigate the impact of the variation in meteorological conditions on the variation of iSOA during the observation period.

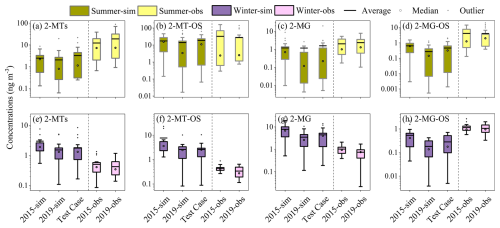

To do so, the CMAQ simulations for 2019 adopted the emissions of 2015 (Test Case), so the variations in simulated iSOA concentration from 2015 to 2019 in this case is mainly attributed to the changes in the meteorological conditions during these years. As shown in Fig. 6, the simulated variations in median concentrations of 2-MTs, 2-MT-OS, 2-MG, and 2-MG-OS in the Test case accounted for 38.3 %–82.4 % and 66.5 %–99.2 % of the concentration reductions in Case 1 in summer and winter, respectively. This suggests that the alteration in meteorological conditions exerts a more substantial influence on the variation in iSOA concentrations compared to the changes in emissions.

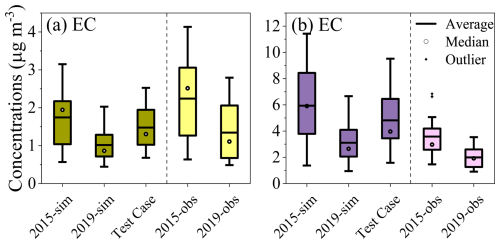

It should be noted that the variations in meteorological conditions not only affect the physical processes such as dilution and transport, but also influence the chemical processes determining the formation of iSOA. To investigate the impacts of physical and chemical factors associated with the variations in meteorological conditions on the abundance of iSOA, the concentrations of elemental carbon (EC) were simulated in the Test Case. As shown in Fig. 7, the simulated median concentrations of summertime and wintertime EC in 2019 both decreased by 32.8 %, respectively, compared to those in 2015. Since EC is a primary pollutant and chemically inert under atmospheric conditions, the variations in its concentration in the Test Case is attributed to the changes in the physical processes, contributing approximately 59.5 % of the EC reductions between 2015 and 2019 (Case 1). As a result, we could expect a similar contribution of the physical processes to the reduction in iSOA concentration. Notably, such reductions are significantly smaller than the simulated concentration reductions of iSOA in the Test case (Fig. 6), suggesting that the chemical factors associated with the changes in meteorological conditions play a crucial role in determining the trend of iSOA in Shanghai, consistent with the above analysis based on the observations. However, we note that the alternation in meteorological conditions cannot explain the observed non-declining trend of 2-MG and 2-MTs in summer, implying that some other factors that are not well represented in the CMAQ model may play a role in controlling such a trend.

Figure 6Simulated concentrations of 2-MTs, 2-MT-OS, 2-MG and 2-MG-OS in summer (a–d) and winter (e–h) in Case 1 (2015-sim and 2019-sim) and Test Case (simulations with 2015 emissions and 2019 meteorological conditions). The observed concentrations of 2-MTs, 2-MT-OS, 2-MG, and 2-MG-OS in 2015 and 2019 are also displayed (Detailed model-measurement comparisons are provided in Sect. 3.2; after accounting for matrix effect, 2-MT-OS would decrease more sharply and 2-MG-OS would show a descending inter-annual trend, consistent with model simulations).

Figure 7Simulated EC concentrations in Case 1 (2015-sim and 2019-sim) and Test Case (simulations with 2015 emissions and 2019 meteorological conditions) in (a) summer and (b) winter. The measured concentrations are also displayed and their trend is consistent with the simulations.

As discussed in Sect. 3.2, there is a large contribution of non-IEPOX sources to 2-MTs. Such sources might not be well represented in the model, which could explain the discrepancy between the simulated and observed trend of 2-MTs in summer. On the other hand, MACR is known as a first-generation oxidation product of isoprene and an important intermediate for iSOA formation through NOx-dominant pathways (Nguyen et al., 2015), but it can also originate from primary sources, such as biological emissions (Jardine et al., 2012), residential wood burning (Gaeggeler et al., 2008), and vehicle exhaust emissions (He et al., 2009). In certain urban areas, MACR arises primarily from vehicular emissions, as observed at the Heshan site in the Pearl River Delta region, China (Ling et al., 2019) and in Houston, US (Park et al., 2011). In the present work, the simulated MACR concentration demonstrated a decreasing trend from 2015 to 2019 in summer when the contribution of primary emissions was considered in the model. Yet, our recent study revealed that, despite a good agreement between modelled and measured isoprene concentrations, the model under-predicted the peak concentrations of MACR during the noon in urban Shanghai (Li et al., 2022), implying an underestimation of secondary formation and/or primary emissions of MACR in the model. Furthermore, Gu et al. (2023) reported that in the southern cities of Jiangsu Province, which is adjacent to Shanghai, anthropogenic VOCs increased by approximately 15 % from 2015 to 2019. Therefore, we infer that the sources (e.g., primary emissions) of MACR might be under-predicted in this work, which may provide a rationale for the inconsistency between simulated and observed inter-annual trends of 2-MG.

In this study, observations of isoprene-derived SOA species in ambient PM2.5 were conducted at an urban site in Shanghai, China during summer and winter in 2015, 2019, and 2021, aiming to understand the response of biogenic SOA formation to anthropogenic emission reductions in polluted regions. The complementary CMAQ model simulations were also performed for 2015 and 2019 and the results are compared to the measurements. It is found that the particulate concentration of total iSOA tracers, dominated by IEPOX-SOA species including 2-MT-OS and 2-MTs, had a decreasing trend from 2015 to 2021 (55.6, 51.0, and 29.7 ng m−3 in 2015, 2019, and 2021, respectively). When the measurement uncertainties of iSOA tracers such as the matrix effect of OSs were considered, 2-MT-OS and 2-MG-OS exhibited a declining trend in both seasons during the observation period. In contrast, 2-MG and 2-MTs showed no significant inter-annual variations After accounting for the gas-phase fraction, 2-MG even exhibited a slight upward trend in summer during these years.

The isoprene-derived SOA species correlated well with ozone and Ox in summer but with sulfate in winter, suggesting that the atmospheric oxidation of isoprene to epoxide intermediates and their subsequent reactive uptake on aqueous aerosols are the key steps driving the formation of iSOA in summer and winter, respectively. The Ox-represented atmospheric oxidizing capacity and aerosol heterogeneous reactivity decreased significantly during the observation period, which provided an explanation for the decreasing trend of iSOA tracers in summer and winter (with the exception of summertime 2-MG and 2-MTs).

The CMAQ model predicted the concentrations of iSOA tracers reasonably well and captured the declining trend of total iSOA, 2-MT-OS, and 2-MG-OS in both seasons, but not the insignificant inter-annual variations of 2-MG and 2-MTs in summer. Further model simulations show that inter-annual variations in iSOA concentration are mainly governed by the changes in the meteorological conditions rather than the emissions. Consistent with the analysis based on the observation data, the model simulations show that the changes in chemical factors such as aerosol heterogeneous reactivity caused by variations in meteorological conditions play an important role in controlling the inter-annual trend of iSOA. The discrepancy between measured and modeled inter-annual trends of 2-MG and 2-MTs is likely ascribed to the presence of unaccounted or underrepresented factors such as the direct emissions of MACR and 2-MTs in the model. Overall, our study revealed the responses and underlying driving factors of iSOA formation under rapidly changing anthropogenic emissions conditions in a typical Chinese megacity. It also highlights the importance of tailored emission reductions for the mitigation of PM formation from biogenic emissions through the regulation of atmospheric oxidizing capacity and aerosol chemical reactivity.

The data presented in this work are available upon request from the corresponding author.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-17889-2025-supplement.

YZ conceived and designed the study, HH, YW, and TY performed the field observation and analyzed the data, JL, YL, TL, and YS performed the model simulations, HH, YZ, and JL wrote the paper, and all other authors contributed to the discussion and writing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research has been supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2022YFC3701003) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22376137 and 22206120).

This paper was edited by Jason Surratt and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bates, K. H., Crounse, J. D., St. Clair, J. M., Bennett, N. B., Nguyen, T. B., Seinfeld, J. H., Stoltz, B. M., and Wennberg, P. O.: Gas Phase Production and Loss of Isoprene Epoxydiols, J. Phys. Chem. A, 118, 1237–1246, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp4107958, 2014.

Bryant, D. J., Dixon, W. J., Hopkins, J. R., Dunmore, R. E., Pereira, K. L., Shaw, M., Squires, F. A., Bannan, T. J., Mehra, A., Worrall, S. D., Bacak, A., Coe, H., Percival, C. J., Whalley, L. K., Heard, D. E., Slater, E. J., Ouyang, B., Cui, T., Surratt, J. D., Liu, D., Shi, Z., Harrison, R., Sun, Y., Xu, W., Lewis, A. C., Lee, J. D., Rickard, A. R., and Hamilton, J. F.: Strong anthropogenic control of secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene in Beijing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 7531–7552, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-7531-2020, 2020.

Bryant, D. J., Elzein, A., Newland, M., White, E., Swift, S., Watkins, A., Deng, W., Song, W., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Wang, X., Rickard, A. R., and Hamilton, J. F.: Importance of Oxidants and Temperature in the Formation of Biogenic Organosulfates and Nitrooxy Organosulfates, ACS Earth Space Chem., 5, 2291–2306, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.1c00204, 2021.

Chen, Y., Ng, A. E., Green, J., Zhang, Y., Riva, M., Riedel, T. P., Pye, H. O. T., Lei, Z., Olson, N. E., Cooke, M. E., Zhang, Z., Vizuete, W., Gold, A., Turpin, B. J., Ault, A. P., and Surratt, J. D.: Applying a Phase-Separation Parameterization in Modeling Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation from Acid-Driven Reactive Uptake of Isoprene Epoxydiols under Humid Conditions, ACS ES&T Air, 1, 511–524, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestair.4c00002, 2024.

Cui, T., Zeng, Z., dos Santos, E. O., Zhang, Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Rose, C. A., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Collins, L. B., Bodnar, W. M., de Souza, R. A. F., Martin, S. T., Machado, C. M. D., Turpin, B. J., Gold, A., Ault, A. P., and Surratt, J. D.: Development of a hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) method for the chemical characterization of water-soluble isoprene epoxydiol (IEPOX)-derived secondary organic aerosol, Environ. Sci.-Proc. IMP, 20, 1524–1536, https://doi.org/10.1039/C8EM00308D, 2018.

Ding, X., He, Q. F., Shen, R. Q., Yu, Q. Q., and Wang, X. M.: Spatial distributions of secondary organic aerosols from isoprene, monoterpenes, beta-caryophyllene, and aromatics over China during summer, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 119, 11877–11891, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jd021748, 2014.

Eddingsaas, N. C., VanderVelde, D. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Kinetics and Products of the Acid-Catalyzed Ring-Opening of Atmospherically Relevant Butyl Epoxy Alcohols, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 8106–8113, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp103907c, 2010.

Fan, Y., Liu, C.-Q., Li, L., Ren, L., Ren, H., Zhang, Z., Li, Q., Wang, S., Hu, W., Deng, J., Wu, L., Zhong, S., Zhao, Y., Pavuluri, C. M., Li, X., Pan, X., Sun, Y., Wang, Z., Kawamura, K., Shi, Z., and Fu, P.: Large contributions of biogenic and anthropogenic sources to fine organic aerosols in Tianjin, North China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 117–137, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-117-2020, 2020.

Frauenheim, M., Offenberg, J., Zhang, Z., Surratt, J. D., and Gold, A.: The C5–Alkene Triol Conundrum: Structural Characterization and Quantitation of Isoprene-Derived C5H10O3 Reactive Uptake Products, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett, 9, 829–836, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00548, 2022.

Frauenheim, M., Offenberg, J., Zhang, Z., Surratt, J. D., and Gold, A.: Chemical Composition of Secondary Organic Aerosol Formed from the Oxidation of Semivolatile Isoprene Epoxydiol Isomerization Products, Environ. Sci. Technol, 58, 22571–22582, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c06850, 2024.

Fu, P., Aggarwal, S. G., Chen, J., Li, J., Sun, Y., Wang, Z., Chen, H., Liao, H., Ding, A., Umarji, G. S., Patil, R. S., Chen, Q., and Kawamura, K.: Molecular Markers of Secondary Organic Aerosol in Mumbai, India, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 4659–4667, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b00372, 2016.

Fu, P. Q., Kawamura, K., Chen, J., Li, J., Sun, Y. L., Liu, Y., Tachibana, E., Aggarwal, S. G., Okuzawa, K., Tanimoto, H., Kanaya, Y., and Wang, Z. F.: Diurnal variations of organic molecular tracers and stable carbon isotopic composition in atmospheric aerosols over Mt. Tai in the North China Plain: an influence of biomass burning, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 8359–8375, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-8359-2012, 2012.

Fu, P. Q., Kawamura, K., Chen, J., and Miyazaki, Y.: Secondary Production of Organic Aerosols from Biogenic VOCs over Mt. Fuji, Japan, Environ. Sci. Technol., 48, 8491-8497, 10.1021/es500794d, 2014.

Gaeggeler, K., Prevot, A. S. H., Dommen, J., Legreid, G., Reimann, S., and Baltensperger, U.: Residential wood burning in an Alpine valley as a source for oxygenated volatile organic compounds, hydrocarbons and organic acids, Atmos. Environ., 42, 8278–8287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.07.038, 2008.

Geng, G., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, S., Cheng, J., Yan, L., Wu, N., Hu, H., Tong, D., Zheng, B., Yin, Z., He, K., and Zhang, Q.: Efficacy of China's clean air actions to tackle PM2.5 pollution between 2013 and 2020, Nat. Geosci., 17, 987–994, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01540-z, 2024.

Gong, J., Yin, Z., Lei, Y., Lu, X., Zhang, Q., Cai, C., Chai, Q., Chen, H., Chen, R., Chen, W., Cheng, J., Chi, X., Dai, H., Dong, Z., Geng, G., Hu, J., Hu, S., Huang, C., Li, T., Li, W., Li, X., Lin, Y., Liu, J., Ma, J., Qin, Y., Tang, W., Tong, D., Wang, J., Wang, L., Wang, Q., Wang, X., Wang, X., Wu, L., Wu, R., Xiao, Q., Xie, Y., Xu, X., Xue, T., Yu, H., Zhang, D., Zhang, L., Zhang, N., Zhang, S., Zhang, S., Zhang, X., Zhang, Z., Zhao, H., Zheng, B., Zheng, Y., Zhu, T., Wang, H., Wang, J., and He, K.: The 2023 report of the synergetic roadmap on carbon neutrality and clean air for China: Carbon reduction, pollution mitigation, greening, and growth, Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol., 23, 100517, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2024.100517, 2025.

Gu, C., Zhang, L., Xu, Z., Xia, S., Wang, Y., Li, L., Wang, Z., Zhao, Q., Wang, H., and Zhao, Y.: High-resolution regional emission inventory contributes to the evaluation of policy effectiveness: a case study in Jiangsu Province, China, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 4247–4269, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-4247-2023, 2023.

Guenther, A., Karl, T., Harley, P., Wiedinmyer, C., Palmer, P. I., and Geron, C.: Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature), Atmos. Chem. Phys., 6, 3181–3210, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-6-3181-2006, 2006.

Guo, H., Xu, L., Bougiatioti, A., Cerully, K. M., Capps, S. L., Hite Jr., J. R., Carlton, A. G., Lee, S.-H., Bergin, M. H., Ng, N. L., Nenes, A., and Weber, R. J.: Fine-particle water and pH in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 5211–5228, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-5211-2015, 2015.

He, C., Ge, Y. S., Tan, J. W., You, K. W., Han, X. K., Wang, J. F., You, Q. W., and Shah, A. N.: Comparison of carbonyl compounds emissions from diesel engine fueled with biodiesel and diesel, Atmos. Environ., 43, 3657–3661, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.04.007, 2009.

Hennigan, C. J., Izumi, J., Sullivan, A. P., Weber, R. J., and Nenes, A.: A critical evaluation of proxy methods used to estimate the acidity of atmospheric particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 2775–2790, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-2775-2015, 2015.

Hettiyadura, A. P. S., Stone, E. A., Kundu, S., Baker, Z., Geddes, E., Richards, K., and Humphry, T.: Determination of atmospheric organosulfates using HILIC chromatography with MS detection, Atmos. Meas. Tech., 8, 2347–2358, https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-8-2347-2015, 2015.

Hettiyadura, A. P. S., Al-Naiema, I. M., Hughes, D. D., Fang, T., and Stone, E. A.: Organosulfates in Atlanta, Georgia: anthropogenic influences on biogenic secondary organic aerosol formation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 3191–3206, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-3191-2019, 2019.

Hu, D., Bian, Q., Li, T. W. Y., Lau, A. K. H., and Yu, J. Z.: Contributions of isoprene, monoterpenes, β-caryophyllene, and toluene to secondary organic aerosols in Hong Kong during the summer of 2006, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 113, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010437, 2008.

Isaacman-VanWertz, G., Yee, L. D., Kreisberg, N. M., Wernis, R., Moss, J. A., Hering, S. V., de Sá, S. S., Martin, S. T., Alexander, M. L., Palm, B. B., Hu, W., Campuzano-Jost, P., Day, D. A., Jimenez, J. L., Riva, M., Surratt, J. D., Viegas, J., Manzi, A., Edgerton, E., Baumann, K., Souza, R., Artaxo, P., and Goldstein, A. H.: Ambient Gas-Particle Partitioning of Tracers for Biogenic Oxidation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 9952–9962, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b01674, 2016.

Jardine, K. J., Monson, R. K., Abrell, L., Saleska, S. R., Arneth, A., Jardine, A., Ishida, F. Y., Serrano, A. M. Y., Artaxo, P., Karl, T., Fares, S., Goldstein, A., Loreto, F., and Huxman, T.: Within-plant isoprene oxidation confirmed by direct emissions of oxidation products methyl vinyl ketone and methacrolein, Global Change Biol., 18, 973–984, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02610.x, 2012.

Kang, M., Fu, P., Kawamura, K., Yang, F., Zhang, H., Zang, Z., Ren, H., Ren, L., Zhao, Y., Sun, Y., and Wang, Z.: Characterization of biogenic primary and secondary organic aerosols in the marine atmosphere over the East China Sea, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 13947–13967, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-13947-2018, 2018.

Lange, B. M., Rujan, T., Martin, W., and Croteau, R.: Isoprenoid biosynthesis: The evolution of two ancient and distinct pathways across genomes, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 13172–13177, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.240454797, 2000.

Kelly, J. M., Doherty, R. M., O'Connor, F. M., and Mann, G. W.: The impact of biogenic, anthropogenic, and biomass burning volatile organic compound emissions on regional and seasonal variations in secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7393–7422, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7393-2018, 2018.

Kjaergaard, H. G., Knap, H. C., Ørnsø, K. B., Jørgensen, S., Crounse, J. D., Paulot, F., and Wennberg, P. O.: Atmospheric fate of methacrolein. 2. Formation of lactone and implications for organic aerosol production, J. Phys. Chem. A, 116, 5763–5768, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp210853h, 2012.

Kurokawa, J. and Ohara, T.: Long-term historical trends in air pollutant emissions in Asia: Regional Emission inventory in ASia (REAS) version 3, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 12761–12793, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-12761-2020, 2020.

Lewandowski, M., Piletic, I. R., Kleindienst, T. E., Offenberg, J. H., Beaver, M. R., Jaoui, M., Docherty, K. S., and Edney, E. O.: Secondary organic aerosol characterisation at field sites across the United States during the spring–summer period, Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem., 93, 1084–1103, https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2013.803545, 2013.

Li, J., Xie, X., Li, L., Wang, X., Wang, H., Jing, S. A., Ying, Q., Qin, M., and Hu, J.: Fate of Oxygenated Volatile Organic Compounds in the Yangtze River Delta Region: Source Contributions and Impacts on the Atmospheric Oxidation Capacity, Environ. Sci. Technol., 56, 11212–11224, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c00038, 2022.

Lin, Y. H., Zhang, Z. F., Docherty, K. S., Zhang, H. F., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Rubitschun, C. L., Shaw, S. L., Knipping, E. M., Edgerton, E. S., Kleindienst, T. E., Gold, A., and Surratt, J. D.: Isoprene Epoxydiols as Precursors to Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation: Acid-Catalyzed Reactive Uptake Studies with Authentic Compounds, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 250–258, https://doi.org/10.1021/es202554c, 2012.

Lin, Y. H., Zhang, H., Pye, H. O. T., Zhang, Z., Marth, W. J., Park, S., Arashiro, M., Cui, T., Budisulistiorini, S. H., and Sexton, K. G.: Epoxide as a precursor to secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene photooxidation in the presence of nitrogen oxides, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 6718–6723, 2013.

Ling, Y., Wang, Y., Duan, J., Xie, X., Liu, Y., Peng, Y., Qiao, L., Cheng, T., Lou, S., Wang, H., Li, X., and Xing, X.: Long-term aerosol size distributions and the potential role of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in new particle formation events in Shanghai, Atmos. Environ., 202, 345–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.01.018, 2019.

Liu, P., Ding, X., Bryant, D. J., Zhang, Y.-Q., Wang, J.-Q., Yang, K., Cheng, Q., Jiang, H., Wang, Z.-R., He, Y.-F., Li, B.-X., Zhao, M.-Y., Hamilton, J. F., Rickard, A. R., and Wang, X.-M.: Comparison of Isoprene-Derived Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation Pathways at an Urban and a Forest Site, ACS Earth Space Chem., 9, 1752–1767, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.4c00398, 2025.

Liu, Y., Yang, X., Tan, J., and Li, M.: Concentration prediction and spatial origin analysis of criteria air pollutants in Shanghai, Environ. Pollut., 327, 121535, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121535, 2023a.

Liu, Y., Geng, G., Cheng, J., Liu, Y., Xiao, Q., Liu, L., Shi, Q., Tong, D., He, K., and Zhang, Q.: Drivers of Increasing Ozone during the Two Phases of Clean Air Actions in China 2013-2020, Environ. Sci. Technol., 57, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c00054, 2023b.

McNeill, V. F., Woo, J. L., Kim, D. D., Schwier, A. N., Wannell, N. J., Sumner, A. J., and Barakat, J. M.: Aqueous-phase secondary organic aerosol and organosulfate formation in atmospheric aerosols: a modeling study, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 8075–8081, 2012.

Nguyen, T. B., Bates, K. H., Crounse, J. D., Schwantes, R. H., Zhang, X., Kjaergaard, H. G., Surratt, J. D., Lin, P., Laskin, A., Seinfeld, J. H., and Wennberg, P. O.: Mechanism of the hydroxyl radical oxidation of methacryloyl peroxynitrate (MPAN) and its pathway toward secondary organic aerosol formation in the atmosphere, PCCP, 17, 17914–17926, https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cp02001h, 2015.

Orlando, J. J., Tyndall, G. S., and Paulson, S. E.: Mechanism of the OH-initiated oxidation of methacrolein, Geophys. Res. Lett, 26, 2191–2194, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GL900453, 1999.

Park, C., Schade, G. W., and Boedeker, I.: Characteristics of the flux of isoprene and its oxidation products in an urban area, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jd015856, 2011.

Paulot, F., Crounse, J. D., Kjaergaard, H. G., Kurten, A., St Clair, J. M., Seinfeld, J. H., and Wennberg, P. O.: Unexpected Epoxide Formation in the Gas-Phase Photooxidation of Isoprene, Science, 325, 730–733, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172910, 2009.

Piletic, I. R., Edney, E. O., and Bartolotti, L. J.: A computational study of acid catalyzed aerosol reactions of atmospherically relevant epoxides, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 15, 18065–18076, https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cp52851k, 2013.

Pye, H. O. T., Pinder, R. W., Piletic, I. R., Xie, Y., Capps, S. L., Lin, Y.-H., Surratt, J. D., Zhang, Z., Gold, A., Luecken, D. J., Hutzell, W. T., Jaoui, M., Offenberg, J. H., Kleindienst, T. E., Lewandowski, M., and Edney, E. O.: Epoxide Pathways Improve Model Predictions of Isoprene Markers and Reveal Key Role of Acidity in Aerosol Formation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 47, 11056–11064, https://doi.org/10.1021/es402106h, 2013.

Pye, H. O. T., Murphy, B. N., Xu, L., Ng, N. L., Carlton, A. G., Guo, H., Weber, R., Vasilakos, P., Appel, K. W., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Surratt, J. D., Nenes, A., Hu, W., Jimenez, J. L., Isaacman-VanWertz, G., Misztal, P. K., and Goldstein, A. H.: On the implications of aerosol liquid water and phase separation for organic aerosol mass, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 343–369, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-343-2017, 2017.

Qin, M., Wang, X., Hu, Y., Ding, X., Song, Y., Li, M., Vasilakos, P., Nenes, A., and Russell, A. G.: Simulating Biogenic Secondary Organic Aerosol During Summertime in China, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 123, 11100–11119, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD029185, 2018.

Rattanavaraha, W., Chu, K., Budisulistiorini, S. H., Riva, M., Lin, Y.-H., Edgerton, E. S., Baumann, K., Shaw, S. L., Guo, H., King, L., Weber, R. J., Neff, M. E., Stone, E. A., Offenberg, J. H., Zhang, Z., Gold, A., and Surratt, J. D.: Assessing the impact of anthropogenic pollution on isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol formation in PM2.5 collected from the Birmingham, Alabama, ground site during the 2013 Southern Oxidant and Aerosol Study, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 4897–4914, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-4897-2016, 2016.

Riedel, T. P., Lin, Y.-H., Budisulistiorini, H., Gaston, C. J., Thornton, J. A., Zhang, Z., Vizuete, W., Gold, A., and Surrattt, J. D.: Heterogeneous Reactions of Isoprene-Derived Epoxides: Reaction Probabilities and Molar Secondary Organic Aerosol Yield Estimates, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2, 38–42, https://doi.org/10.1021/ez500406f, 2015.

Sagner, S., Eisenreich, W., Fellermeier, M., Latzel, C., Bacher, A., and Zenk, M. H.: Biosynthesis of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol in plants by rearrangement of the terpenoid precursor, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, Tetrahedron Lett., 39, 2091–2094, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00296-2, 1998.

Shrivastava, M., Andreae, M. O., Artaxo, P., Barbosa, H. M. J., Berg, L. K., Brito, J., Ching, J., Easter, R. C., Fan, J., Fast, J. D., Feng, Z., Fuentes, J. D., Glasius, M., Goldstein, A. H., Alves, E. G., Gomes, H., Gu, D., Guenther, A., Jathar, S. H., Kim, S., Liu, Y., Lou, S., Martin, S. T., McNeill, V. F., Medeiros, A., de Sa, S. S., Shilling, J. E., Springston, S. R., Souza, R. A. F., Thornton, J. A., Isaacman-VanWertz, G., Yee, L. D., Ynoue, R., Zaveri, R. A., Zelenyuk, A., and Zhao, C.: Urban pollution greatly enhances formation of natural aerosols over the Amazon rainforest, Nat. Commun., 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08909-4, 2019.

Song, S., Gao, M., Xu, W., Shao, J., Shi, G., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., and McElroy, M. B.: Fine-particle pH for Beijing winter haze as inferred from different thermodynamic equilibrium models, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 7423–7438, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7423-2018, 2018.

St. Clair, J. M., Rivera-Rios, J. C., Crounse, J. D., Knap, H. C., Bates, K. H., Teng, A. P., Jørgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., Keutsch, F. N., and Wennberg, P. O.: Kinetics and Products of the Reaction of the First-Generation Isoprene Hydroxy Hydroperoxide (ISOPOOH) with OH, J. Phys. Chem. A, 120, 1441–1451, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b06532, 2016.

Stone, E. A., Nguyen, T. T., Pradhan, B. B., and Man Dangol, P.: Assessment of biogenic secondary organic aerosol in the Himalayas, Environ. Chem., 9, 263–272, https://doi.org/10.1071/EN12002, 2012.

Surratt, J. D., Kroll, J. H., Kleindienst, T. E., Edney, E. O., Claeys, M., Sorooshian, A., Ng, N. L., Offenberg, J. H., Lewandowski, M., Jaoui, M., Flagan, R. C., and Seinfeld, J. H.: Evidence for organosulfates in secondary organic aerosol, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 517–527, https://doi.org/10.1021/es062081q, 2007.