the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Review of interactive open-access publishing with community-based open peer review for improved scientific discourse and quality assurance

Ken S. Carslaw

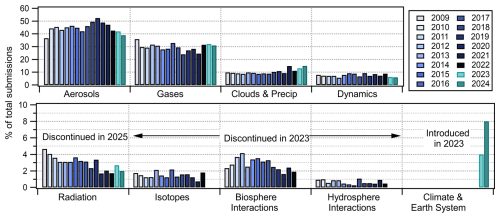

Thomas Koop

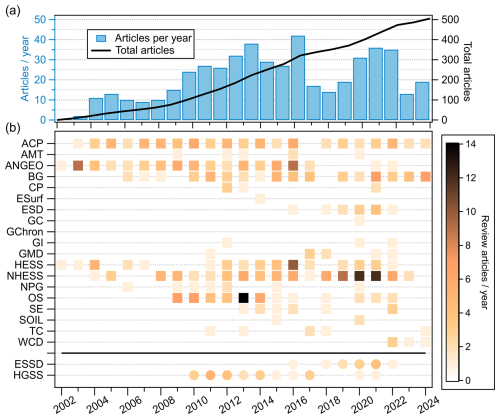

Scientific discourse and quality assurance can be improved by open-access (OA) publishing with public peer review and community discussion. Over 25 years, the viability of this approach has been proven by the interactive OA journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP) and 18 other journals published by the European Geosciences Union (EGU) and its scientific service provider Copernicus Publications. The success of the EGU journals reflects the benefits of community-driven, interactive OA publishing, including high scientific quality and impact, efficient self-regulation, low cost, and financial sustainability. Since 2001, the EGU has published over 50 000 journal articles, 60 000 preprints and 250 000 comments, utilizing and integrating different OA financing models (green, gold, diamond/platinum). The EGU journals with multi-stage open peer review are linked to the OA repository and interactive community platform EGUsphere and to the virtual scientific highlight magazine EGU Letters, integrating different levels of scientific communication and exchange. The EGU publications combine multiple features of open science, including different forms of open peer review and community evaluation with open-access, open data and open-source elements tailored to the needs and preferences of different disciplines. Indeed, the EGU pioneering approach to transparent peer review has spread to other leading publishers, including the Nature publishing group. We review the approach, achievements and future perspectives of interactive OA publishing (including transformative/institutional agreements and AI/ML tools) and its contribution to a universal epistemic web that captures the scientific discourse and comprehensively documents what we know, how well we know it and where the limitations are.

- Article

(12665 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1169 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

- Included in Encyclopedia of Geosciences

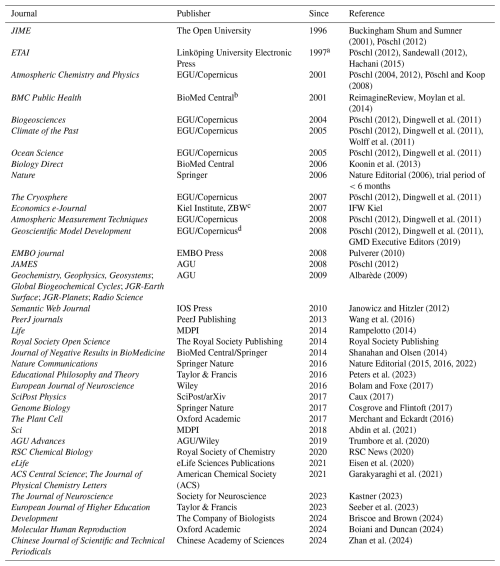

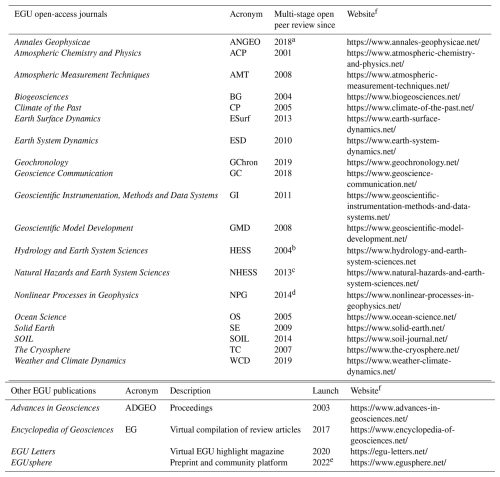

Traditional forms of scientific publishing and peer review do not satisfy current demands for efficient and traceable scientific communication and quality assurance (Pöschl, 2004, 2012; Kriegeskorte, 2012; Bornmann and Haunschild, 2015; Tennant et al., 2017; Ross-Hellauer, 2017; Tennant, 2018; Waltman et al., 2023). To improve the publishing and review process, scientists worked with the European Geosciences Union (EGU) and its publisher Copernicus to develop and launch the first interactive open-access (OA) journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (ACP) in the years 2000/2001, i.e., a couple of years before the term “open access” was formally established in the declarations of the Budapest Open Access Initiative (2002), Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing (2003), and Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities (2003). By now, the EGU publishing portfolio comprises 19 OA journals (Table A1 and EGU journals, https://www.egu.eu/publications/open-access-journals/) covering the full spectrum of geoscientific research. These interactive journals provide OA to the published articles and allow for public peer review and discussion that is open to the scientific community and to the public. The journals employ public peer review of manuscripts that are posted as preprints or discussion papers after a rapid pre-screening or access review. The advantages of the interactive OA publishing model of ACP and the other EGU/Copernicus journals can be summarized as follows (Pöschl, 2012):

-

Free scientific speech and rapid distribution of original research results after quick pre-screening/access review to remove submissions that are clearly deficient or out of scope.

-

Documentation of critical scientific discourse and exchange of arguments, complementary information, open questions, scientific controversies or flaws.

-

Traceability of quality assurance by citable reference and permanent digital object identifier (DOI) assigned to all elements of public review and discussion.

-

Transparency in maintaining scientific integrity by facilitating the detection and reducing the risk of unethical behavior or abuse of the publication and review process (plagiarism, delay/obstruction during hidden peer review, etc.).

-

Public exposure, review and discussion of original manuscripts to provide public recognition that attracts high-quality submissions and a permanent record of critical feedback, which, in turn, deters low-quality submissions and ultimately results in low rejection rates.

-

Public scrutiny to achieve effective self-regulation, high efficiency of scientific quality assurance and efficient use of (peer) reviewing capacities as the most limited resource in the scientific publishing process.

-

Educational value of public access to scientific communication and discussion, enabling everyone to follow and learn from real examples of how scientific critiques are addressed and how consensus can be reached or how disagreement can be handled in a rational and constructive way.

The motivation, approach and design of the EGU interactive OA publishing model have been described before (Gura, 2002; Pöschl, 2004, 2012; Cartlidge, 2007; Pöschl and Koop, 2008; van Edig, 2016); its performance and benefits have been independently evaluated and compared to other publishing models (Bornmann et al., 2010, 2011, 2012; Ho et al., 2013; Bornmann and Haunschild, 2015; Kovanis et al., 2017; Tennant et al., 2017; Ross-Hellauer and Görögh, 2019; Hynninen, 2022). For example, Bornmann et al. (2011) stated that “All in all, our results on the predictive validity of the ACP peer-review system can support the high expectations that Pöschl (2010), Chief Executive Editor of ACP, has of the new selection process at the journal: `The two-stage publication process stimulates scientists to prove their competence via individual high-quality papers and their discussion, rather than just by pushing as many papers as possible through journals with closed peer review and no direct public feedback and recognition for their work. Authors have a much stronger incentive to maximize the quality of their manuscripts prior to submission for peer review and publication, since experimental weaknesses, erroneous interpretations, and relevant but unreferenced earlier studies are more likely to be detected and pointed out in the course of interactive peer review and discussion open to the public and all colleagues with related research interests. Moreover, the transparent review process prevents authors from abusing the peer-review process by delegating some of their own tasks and responsibilities to the referees during review and revision behind the scenes.”'

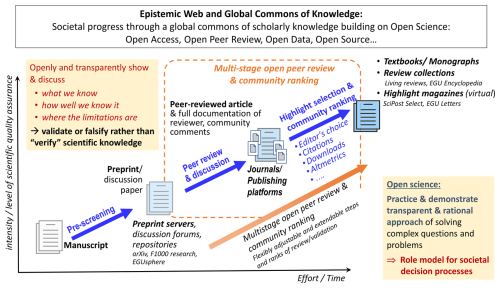

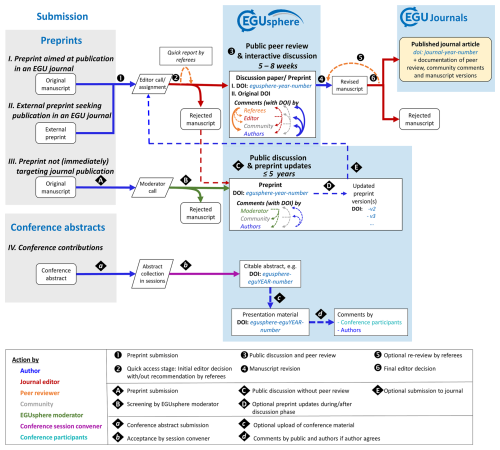

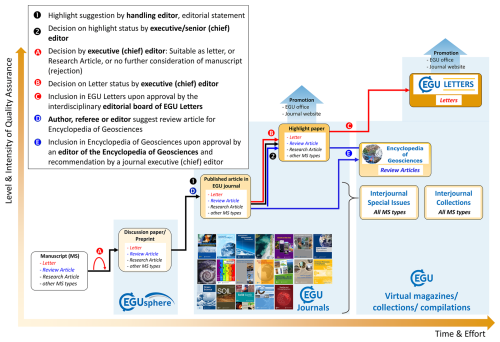

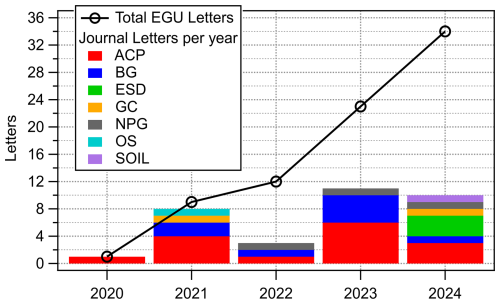

Illustrating the big picture of interactive OA publishing, Fig. 1 outlines how public review and discussion contribute to the advancement and refinement (“distillation”) of scholarly knowledge and to the development of an epistemic web that displays the scholarly discourse and shows what we know, how well we know it and where the limitations are in accordance with the scientific method and critical rationalism (Popper, 1974; Hyman and Renn, 2012; Pöschl, 2012; MPIC Open access).

Figure 1Schematic illustration of interactive open-access publishing within an epistemic web and global commons of scholarly knowledge (Popper, 1974; Hyman and Renn, 2012; Pöschl, 2012; MPIC Open access).

In Sect. 2, we provide a brief overview of approaches and developments that evolved over the past decades to enhance the accessibility, efficiency and transparency of the scientific publishing and review process. In Sects. 3 and 4, we review the key features and evolution of the interactive OA publishing approach as applied in the EGU journals and its related platforms including the OA repository EGUsphere, the Encyclopedia of Geosciences and the virtual highlight magazine EGU Letters.

2.1 Open-access (OA) publishing

2.1.1 Early initiatives on OA publishing

Open access, i.e., the free online availability and re-usability of scientific publications, leads to greater visibility, impact and equitable accessibility of scientific research results and knowledge for the global scientific community and interested public (Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities, 2003; Eysenbach, 2006; Norris et al., 2008; SPARC Europe, 2015; Tennant et al., 2016; Langham-Putrow et al., 2021; Brainard, 2024a; Can et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2024). In the traditional subscription-based model of scientific publishing, most articles require payment for access, which is particularly disadvantageous for scientific exchange and for people in resource-poor institutions and regions. Early attempts to make scientific journal articles and preprints openly available on the internet began with bottom-up initiatives of scientific researchers in the 1980s and 1990s, including but not limited to the high-energy physics preprint repository arXiv (Sect. 2.3.1), the New Journal of Physics (OA since 1998, Bodenschatz, 2008) and the Journal of Medical Internet Research (OA since 1999, Eysenbach, 2019). In the early 2000s, further OA journals were established by researchers, learned societies and innovative commercial publishers in the geosciences and life sciences, including Copernicus Publications, the European Geosciences Union (EGU) and its predecessor European Geophysical Society (1971–2003), the Public Library of Science (PLOS), and BioMed Central. In parallel, major scientific institutions adopted the aims and further developed the concepts of OA publishing. For example, the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities (2003) has been signed by over 800 leading scholarly organizations worldwide, whereby the EGU was one of the first international learned societies among the signatories (EGU News, 2020).

The proportion of OA articles among the large number of scientific journal articles (>2 million per year, published in >20 000 peer-reviewed journals, e.g., Web of Science; Scopus, 2025; Ulrich's Web), however, increased only slowly during the first 10 years after the Berlin Declaration because most funds available to cover costs of scientific journal publishing were bound in subscription contracts. Traditional publishers moved only very slowly and reluctantly towards a proper OA publishing market (Schimmer et al., 2015; Brainard, 2023; Frank et al., 2023; Kiley, 2023). To accelerate the progress and transform the corpus of traditional pay-walled subscription journals to OA, scholars, scholarly organizations and research funders developed a variety of initiatives at institutional, national and international levels (OA2020, 2016a; Pöschl, 2020; cOAlition S Blog, 2023). These and related initiatives aim at redirecting funding from subscription or paywall access to OA in scholarly oriented and cost-efficient, i.e., cost-neutral or cost-saving, ways (Pöschl, 2015; Schimmer et al., 2015).

2.1.2 OA models: green, gold, diamond/platinum

Different approaches are employed to provide free access to scientific content. These approaches vary in terms of timing of open access, copyrights, coverage of publications costs and funding sources. The three major forms are often described by the following categories, which are, however, only loosely defined:

-

Green OA (OA archiving) requires that authors self-archive their publications in repositories that are funded by their institution or by other sources. Publishers of the journals where the original article was published may impose embargo periods prior to archiving of closed-access articles, and they also may retain the copyrights for the distribution of the work. The green OA approach can help to advance OA, but it has not been proven to offer a viable alternative to traditional journal publishing and quality assurance. It can introduce ambiguities and confusion about the public availability and validity of different versions of scientific studies, where preliminary versions have been self-archived and the final validated version may be available through a subscription journal only. The open science community platform EGUsphere (Sect. 4.2) enables the archiving of preprints as well as their linking and transfer to peer-reviewed scientific journals, including but not limited to the EGU interactive OA journals.

-

Gold OA (OA publishing) requires the payment of article processing charges (APCs) that are either covered by the authors themselves or via publishing agreements with their institutions. The APCs cover the costs associated with the paper production, archiving and other publisher-related expenses (Sect. 4.1.7). Gold OA allows immediate and free access to the publication for all readers and, thus, removes the pay walls that exist in many traditional journals that only allow access when readers or their institutions pay a subscription to the journal. Many current efforts are dedicated to converting such “closed-access” journals into OA journals via “transformative agreements” (Sect. 2.1.3) or to initiate full OA journals, such as those published by EGU/Copernicus. The long-term viability of this approach has been proven for more than a couple of decades by the journals of EGU/Copernicus and other early OA publishers as outlined above and detailed below.

-

Diamond/platinum OA (OA publishing) implies that the APCs are covered through funding by institutions, universities, research organizations or other external sources. Even though authors may perceive diamond OA as cost-free publishing, it relies on sustainable funding sources to support and maintain the publishing infrastructure without any charges for authors or readers. Diamond OA is offered by EGU journals during their start-up phase and for corresponding authors from countries in the Research4Life groups as well as other authors with insufficient funding (Sect. 4.1.7). During the past few years, some other, newly launched geoscience journals have pursued the diamond OA approach1. They are usually sponsored by individual institutions and led by an editorial team that performs all steps of the publishing process for relatively few papers without professional publisher support. Another example is the journal Aerosol Research, launched by Copernicus Publications in 2023. This journal is sponsored by several research institutions and scientific societies to allow for long-term financing (Elm et al., 2023). Similar schemes can be envisioned for EGU journals in the future. Depending on scientific developments, disciplinary preferences and the global publishing landscape, sponsors may include research agencies or a sufficient number of large OA publishing agreements. For diamond/platinum OA journals, most of which are relatively recent and small, the large-scale viability, long-term commitment of supporting/funding bodies and scientific sustainability still remain to be proven.

2.1.3 Transformative and full OA publishing agreements

Transformative agreements (TAs) or “publish-and-read” agreements are contracts between scholarly institutions or consortia and publishers to transition publication output to OA; at the same time, these contracts ensure access to content that was previously covered via the institutional subscriptions to the journal. These agreements, thus, lead to OA publication for participating institutions while maintaining access to subscription-based content from other institutions or consortia that have not established OA. Such agreements offer flexible ways for publishers, institutions, consortia and countries of gradually converting subscription-based journals into OA (OA2020, 2016a; ESAC, 2014; cOAlition S Blog, 2023; Springer Nature, 2024). At the same time and as outlined in the OA2020's mission statement (OA2020, 2016b), it remains important to uphold and promote further improvements in scientific publishing at reasonable and competitive costs through innovation and competition. This involves not only traditional subscription publishers through TAs, but also innovative fully OA publishers through equivalent OA publishing agreements (e.g., institutional agreements with Copernicus Publications, Sect. 4.1.7).

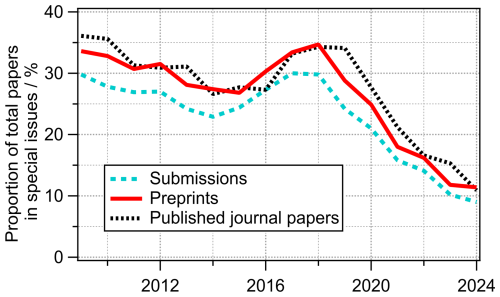

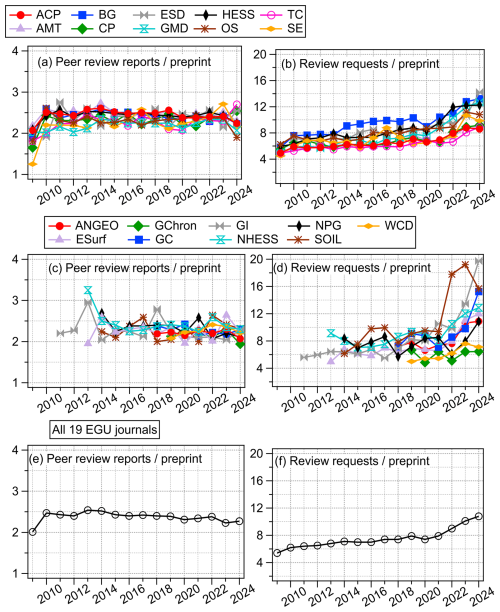

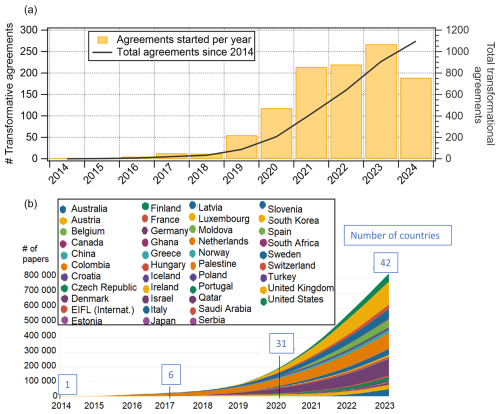

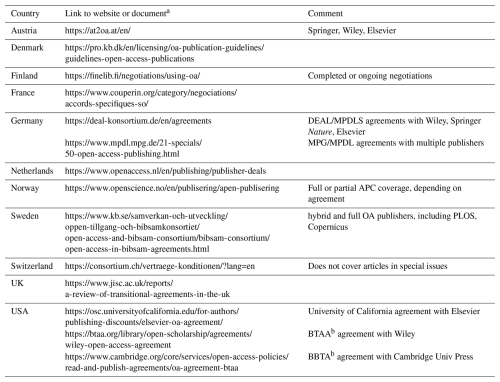

The evolution of the number of TAs in the ESAC registry (2024) that start per year and the number of OA articles published on the basis of TAs are shown in Fig. 2. Some examples of such TAs with traditional subscription publishers and of agreements with full OA publishers are listed in Table 1. Leading scholarly organizations and consortia in a growing number of countries have successfully negotiated and used TAs with major international scientific publishers to achieve high percentages of OA for their publication output during recent years (Fig. S1 in the Supplement), while some national organizations continue to resist these developments due to concerns over supposed financial sustainability, perceived inequities in cost distribution or speculative fears about future cost increases (Schuhl, 2024).

Figure 2(a) Number of transformational agreements started per year (left axis) and cumulative number (right axis) registered in the given year with the Initiative for Efficiency and Standards for Article Charges (ESAC, 2014). (b) Cumulative number of published open-access articles using transformational agreements (figure adapted from Dér, 2023, with modifications). The data in the figure are arranged in alphabetical order by country, starting from the bottom.

Several countries and scholarly organizations have already achieved OA for more than 90 % of their scientific journal publishing output (B16 Conference, 2023) using TAs with traditional publishers, agreements with proper OA publishers and further OA publishing funds for scientists to flexibly cover OA article processing charges. For example, the German Max Planck Digital Library (MPDL) has converted more than 95 % of the publication output of the Max Planck Society into OA via the German National Consortium DEAL with big traditional publishers (Elsevier, Springer, Wiley) and via individual contracts with numerous OA and learned society publishers (Dér, 2023).

Table 1Overview of selected transformative or full open-access publishing agreements in various countries (ESAC, 2014; OA2020, 2016a; B16 Conference, 2023).

a Last access for all links: 28 September 2025. b Big Ten Academic Alliance, https://btaa.org/about.

This development towards a full OA landscape helps to maintain and increase bibliodiversity of scholarly scientific publications, i.e., the variety of publishing formats, models, platforms and outlets used to disseminate scientific knowledge in different disciplines, languages and regions of the world (Jussieu Call, 2016). It also includes the range of financing models and mechanisms (e.g., gold/diamond OA) to make scientific publishing and its access inclusive and equitable. This desired outcome will be reached if OA agreements not only focus on large publishers but are also extended to smaller publishers and new publishing models. This is, for example, practiced by the JISC in the UK that can be considered a role model for how library agencies could and should provide OA publishing agreements to learned societies and small innovative OA publishers like Copernicus. Acknowledging this evolution toward full OA to all scientific literature, Time magazine recognized the advances in OA achieved by transformative agreements as one of the “13 ways the world got better in 2023” (TIME, 2023).

The average fee per article in the traditional subscription publishing model is approximately EUR 4000, whereas OA journals of similar quality are sustainable with article charges of EUR 2000 or less (Open APC, 2024). This was shown by Schimmer et al. (2015) in a comprehensive analysis of the global scholarly journal publication market with a financial annual volume of ∼ EUR 10 billion, mostly paid by publicly funded academic libraries. Similar differences were found in more recent, less comprehensive studies (Björk and Solomon, 2015; Pinfield et al., 2016; Triggle and Triggle, 2017; Ross-Hellauer et al., 2018; Pollock and Michael, 2019; Grossmann and Brembs, 2021; Borrego, 2023; Haustein et al., 2024). In other words, the costs of traditional subscription journals are on average higher by a factor of 2 than required to produce high-quality publications. This is also reflected by the high profit margins of traditional journal publishers, often exceeding 35 %, i.e., higher oligopoly revenues than in many other industries (Van Noorden, 2013; Larivière et al., 2015; Pöschl, 2020; Butler et al., 2023). Thus, concerns that OA threatens the financial viability of the academic publishing system, as, e.g., put forward by Velterop (2003), are unfounded because much more public funding than needed for OA publishing is bound in the traditional subscription journal business. The financial benefits and savings through transformative agreements have been clearly demonstrated by the MPDL and the German DEAL consortium. For example, the MPDL managed to convert practically all scientific journal publication output of the Max Planck Society from subscription to OA over a period of 6 years without any increase in expenses in spite of substantial inflation (2018–2024: approx. EUR 14 million unchanged; see slide 13 in Dér, 2024). Moreover, the DEAL consortium managed to obtain OA for all research articles with corresponding authors from German institutions while reducing the overall expenses for Elsevier journals from approx. EUR 50 million in 2015 to approx. EUR 30 million in 2023, corresponding to a 40 % cost reduction (Vogel, 2023). The opportunities and viability of cost saving through OA are confirmed by the following: while nearly 50 % of new peer-reviewed articles are now published OA, 80 % of publisher revenues are still bound in opaque subscription fees (B17 Conference, 2025). On average, 1 %–2 % of total research budgets by scientific institutions is spent on literature and information provision and publishing (German Science and Humanities Council, 2022). However, the distribution of these funds is important in the OA transition and also implies that financial flows within the institutions should be adjusted accordingly.

OA publishing models have led to valid concerns about the potential impacts of OA on the quality of scientific content (Pöschl, 2004; Björk, 2019; MacLeavy et al., 2020; Frank et al., 2023). Since APCs are levied for individual articles, unlike in subscription payments which are remunerated to entire journals or journal families, every published OA article enhances the publisher profits. As a consequence, the APC business model led to the launch of a large number of journals motivated purely by commercial interests. These journals solicit a high number of submissions that often undergo only cursory (if any) peer review, resulting in publications of low scientific quality, and are thus frequently referred to as “predatory journals” (Beall, 2017; Grudniewicz et al., 2019; Brainard, 2023). We strongly propose that such economically driven aberrations of OA publishing be counteracted by measures of quality assurance providing transparent evidence of rigorous peer review. With the goal of maintaining or even improving scholarly quality assurance, the EGU interactive OA journals and other innovative OA publishing platforms applying various forms of open and/or transparent peer review and different OA approaches (diamond/gold) were launched even prior to initiatives aimed at the OA transformation of traditional subscription journals (Sects. 3 and 4).

2.2 Open peer review

Balancing the needs of rapid dissemination of scientific results and publications while ensuring scientific quality can be achieved by complementing traditional publishing practices with open and transparent approaches (Pöschl, 2004, 2010, 2012; Kriegeskorte, 2012; Bornmann and Haunschild, 2015). The traditional peer-review system neither allows for tracking the rigor of the peer review nor leads to quick, efficient communication of scientific knowledge (Tennant et al., 2017; Tennant, 2018; Ross-Hellauer, 2017; Borrego et al., 2021; Aczel et al., 2025; Pattinson and Currie, 2025), which may inherently bias scientific assessment and progress (Lee et al., 2013). These shortcomings were recognized in the recent “Proposal towards responsible publishing” (cOAlitionS, 2023) that suggests measures to ensure scientific quality, several of which have already been implemented in the publication model by EGU/Copernicus since 2001 (Sect. 3).

The need for transparency and the advantages of interactive public discussion during the peer-review process have been discussed (Kriegeskorte, 2012; Sandewall, 2012; Walker and Rocha da Silva, 2015; Fiala and Diamandis, 2017; Horbach and Halffman, 2018; Wolfram et al., 2020). During the last decades, new ways of peer review have been suggested, including several forms of open peer review (Ross-Hellauer, 2017). The two most common ones are the disclosure of the reviewer identities to the authors and the publication of reviewer reports alongside the papers either during the peer review or after publication (or a combination of both) (Ross-Hellauer et al., 2023). Initial concerns about potential bias among reviewers in an open peer-review process were shown to be unfounded (Thelwall et al., 2020); in fact, there is evidence that such reviews may be even more constructive (Ross-Hellauer and Horbach, 2024). In the EGU journals, all peer-reviewer comments are immediately published, and they are subsequently archived as part of the interactive discussion, in which the referees, editors, authors and the scientific community can participate. Therefore, we refer to it as “public peer review” in the context of the EGU journals, which is arguably one of the longest-practiced, best-established and most successful forms of open peer review.

It seems that the importance of proper archiving and citability for manuscripts and reviewer comments has been overlooked in the open peer-review experiments of various publishers and societies. For example, the American Geophysical Union (AGU) started experimenting with public peer review in 2008, building on the success of the EGU interactive OA journals, which were at that time already very well established in the global geoscience community. Unlike the EGU, however, the AGU did not offer permanent archiving but deleted the discussion papers and interactive comments after public review and final acceptance or rejection of a manuscript (Albarède, 2009). This line was also followed by the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems (JAMES), which had initially adopted the interactive OA publishing concept of ACP but did not maintain the archiving of comments in their discussion forum (JAMES-D). It was taken over by the AGU, but eventually open peer review was abandoned (Pöschl, 2012). The 2006 “peer-review trial and debate” in Nature (Nature Editorial, 2006) was also not successful because neither authors nor their colleagues and readers had much of an incentive to participate in the public discussion (Pöschl, 2012). Articles were posted in a public discussion forum while they underwent closed peer review with non-public referee comments. A very high fraction (93 %) of all papers were rejected, not because of a lack of scientific quality but because they were not deemed sufficiently exciting for the interdisciplinary audience of the magazine. For the rejected manuscripts, the previously published comments would become inaccessible. The incomplete documentation of the scientific discourse, which was an inherent result of deleting discussion papers and comments, undermined several key aspects of the public discussion and peer review, including the documentation of controversial scientific innovations or flaws, public recognition of commentators' contributions, and deterrence of careless submissions. Such differences may appear subtle at first sight, but they may explain why several other trials of open peer review were much less successful than the approach of ACP/EGU. After all, most scientists do care what happens to manuscripts and comments in which they have invested substantial effort, i.e., if their results and opinions voiced in a public review and discussion process remain traceable or not.

Already in 1996, the Journal of Interactive Media in Education JIME was launched, facilitating in a first stage of the publication process a “private open peer review” between authors and eponymous reviewers. In a second stage, the public could comment on the author and reviewer comments, after which the editor advised the authors on the revision of their manuscript (Buckingham Shum and Sumner, 2001). Finally, the editor decided which, optionally edited, parts of the interactive discussion were published alongside the final paper. This interactive review concept, however, does not seem to have been applied in JIME any longer after its relaunch in 2011 (Weller, 2012). The journal Electronic Transactions on Artificial Intelligence (ETAI), launched in 1997 and discontinued as of 2006, introduced a different form of interactive two-stage publication process (Sandewall, 2012; Hachani, 2015): in a first stage, the scientific community could publicly discuss the article. In a second stage, designated peer reviewers provided reports that were available to the authors and editors only, but not to the public. In both JIME and ETAI, the discussions were restricted to interactions between specific groups, i.e., only within the scientific community or between referees and authors, respectively, limiting the overall transparency of the review process and the traceability of the evolution of the scientific manuscript.

A variant of interactive and public peer review has been explored by eLife, an OA journal in the biomedical and life sciences, launched jointly in 2011 by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Max Planck Society and the Wellcome Trust (Schekman et al., 2012). In the initial years of eLife, there was a non-public interactive discussion between reviewers and authors. As of 2021, this discussion has been open to the public with a full record of all reviewer comments and author responses (Eisen et al., 2020), similar to the concept as applied in the EGU journals (Fig. 3). The review process in eLife was concluded with a public editor decision to accept or reject the paper. This latter step was abandoned as of 2022; instead, the review process concludes with an editorial “eLife assessment”, implying that the public communication among authors, reviewers and editors is sufficient for readers to judge the research quality (Eisen et al., 2022). However, this concept has led to major controversy among the eLife editors (Else, 2022; Abbott, 2023) and to discussions about the interconnections between peer review, editorial policies and indexing by the Web of Science (Brainard, 2024a, b; eLife, 2024; Stern, 2024; Barbour et al., 2025; eLife, 2025).

As a compromise between traditional closed peer review and public interactive peer review, some publishers and journals, such as the medical and biological journals by BioMed Central, as of 2001, provide a record of the pre-publication history of the scientific exchange between the reviewers, editors and authors after the publication of a final peer-reviewed paper (Cosgrove and Flintoft, 2017). As of 2020, more than 500 journals publish peer-reviewer reports alongside the published paper, either immediately or as post-publication review history; their publication may be mandatory or upon approval by the authors and/or reviewers (Wolfram et al., 2020).

Table 2 lists several of such journals, illustrating the pioneering role of the EGU in public peer review. In later years, some publishers offered to publish reviewer reports for journal families or series, e.g., PLOS (Madison, 2019), Elsevier (Bravo et al., 2019; Justman, 2019), IOP publishing (Banks, 2019), Wiley (Moylan et al., 2020) and Sage Publications (Sage, 2021).

Buckingham Shum and Sumner (2001)Pöschl (2012)Pöschl (2012)Sandewall (2012)Hachani (2015)Pöschl (2004, 2012)Pöschl and Koop (2008)ReimagineReviewMoylan et al. (2014)Pöschl (2012)Dingwell et al. (2011)Pöschl (2012)Dingwell et al. (2011)Wolff et al. (2011)Pöschl (2012)Dingwell et al. (2011)Koonin et al. (2013)Nature Editorial (2006)Pöschl (2012)Dingwell et al. (2011)IFW KielPöschl (2012)Dingwell et al. (2011)Pöschl (2012)Dingwell et al. (2011)GMD Executive Editors (2019)Pulverer (2010)Pöschl (2012)Albarède (2009)Janowicz and Hitzler (2012)Wang et al. (2016)Rampelotto (2014)Royal Society PublishingShanahan and Olsen (2014)Nature Editorial (2015, 2016, 2022)Peters et al. (2023)Bolam and Foxe (2017)Caux (2017)Cosgrove and Flintoft (2017)Merchant and Eckardt (2016)Abdin et al. (2021)Trumbore et al. (2020)RSC News (2020)Eisen et al. (2020)Garakyaraghi et al. (2021)Kastner (2023)Seeber et al. (2023)Briscoe and Brown (2024)Boiani and Duncan (2024)Zhan et al. (2024)Table 2Selection of journals disclosing peer-review reports (optional/mandatory, after/during review) sorted by the year, in which this feature was introduced.

While the post-publication of the peer-review history does not allow for participation of other members of the scientific community in an interactive discussion with authors and referees, it provides at least evidence of the existence and the rigor of the peer-review process. Such disclosure of reviewer comments upon publication of final papers should be regarded as a minimum standard for OA publishing in order to counteract low scientific standards of (semi-)predatory and fraudulent journals that are solely motivated by the publishers' financial interests. The mere post-publication of reviewer reports, however, inherently leads to a kind of bias and loss of information because only the reports of finally accepted papers are shown, whereas the reviews for rejected manuscripts are lost. In addition, deleting the discourse on papers that do not ultimately result in journal publication diminishes the educational value of open peer review, as these examples also provide important learning opportunities and orientation for all involved parties.

Full transparency during the review process may only be achieved by publishing not only reviewer reports but also reviewer identities. Some studies suggest that this could result in fewer reviewers being willing to take on the task (van Rooyen et al., 1999; Fox, 2021) and lead to less critical reviewer reports, in particular from early-career researchers who may feel intimidated about publicly criticizing more experienced colleagues (Rodríguez-Bravo et al., 2017). However, other studies did not find any significant evidence that open identities limit criticism (van Rooyen et al., 2010; Ross-Hellauer and Horbach, 2024). In the EGU journals, a significant number of referees voluntarily reveal their names (on average 19 % (10 %–63 %), Sect. 3.3, Table S2). This number is higher than in journals with closed peer review (∼ 6 %, Fox, 2021), demonstrating self-regulation of the EGU's public peer review, in which reviewers take pride in and appreciate the acknowledgment they receive inherently for their publicly available, citable reports. In addition, referee reports can be entered to platforms like ORCID or the Web of Science Reviewer Recognition tool (formerly “Publons”, an independent platform (2012–2017, acquired by Clarivate in 2017), providing additional recognition for these scientific contributions.

Nature reported on the EGU approach (Gura, 2002), performed an open peer-review trial (Nature Editorial, 2006), and recently announced that it will publish all reviewer reports for new papers, making mandatory what had been optional since 2020 (Nature Editorial, 2025):

Since 2020, Nature has offered authors the opportunity to have their peer-review file published alongside their paper. Our colleagues at Nature Communications have been doing so since 2016. Until now, Nature authors could opt in to this process of transparent peer review. From 16 June, however, new submissions of manuscripts that are published as research articles in Nature will automatically include a link to the reviewers' reports and author responses. It means that, over time, more Nature papers will include a peer-review file. The identity of the reviewers will remain anonymous, unless they choose otherwise – as happens now. But the exchanges between the referees and the authors will be accessible to all. Our aim in doing so is to open up what many see as the “black box” of science, shedding light on how a research paper is made. This serves to increase transparency and (we hope) to build trust in the scientific process.

As we have written previously, a published research paper is the result of an extensive conversation between authors and reviewers, guided by editors. These discussions, which can last for months, aim to improve a study's clarity and the robustness of its conclusions. It is a hugely important process that should receive increased recognition, including acknowledgement of the reviewers involved, if they choose to be named. For early-career researchers, there is great value in seeing inside a process that is key to their career development. Making peer-reviewer reports public also enriches science communication: it's a chance to add to the “story” of how a result is arrived at, or a conclusion supported, even if it includes only the perspectives of authors and reviewers. The full story of a paper is, of course, more complex, involving many other contributors.

Many people think of science as something fixed and unchanging. But scientific knowledge evolves as new or more-nuanced evidence comes to light. Scientists constantly discuss their results, yet these debates are not contained in research papers and often remain unreported in wider science-communication efforts. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a brief interlude during which much of the world got to see how research works, almost in real time. It's easy to forget that, right from the start, we were continuously learning something new about the nature and behaviour of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. On television screens, in newspapers and on social media worldwide, scientists were discussing among themselves and with public audiences the nature of the virus, how it infects people and how it spreads. They were debating treatments and prevention methods, constantly adjusting everyone's knowledge as fresh evidence came to light. And then, it went mostly back to business as usual. We hope that publishing the peer-reviewer reports of all newly submitted Nature papers shows, in a small way, that this doesn't need to remain the case. Nature started mandating peer review for all published research articles only in 1973 (M. Baldwin Notes Rec. 69, 337–352; 2015). But the convention in most fields is still to keep the content of these peer-review exchanges confidential. That has meant that the wider research community, and the world, has had few opportunities to learn what is discussed. Peer review improves papers. The exchanges between authors and referees should be seen as a crucial part of the scientific record, just as they are a key part of doing and disseminating research.

This move is a major improvement for which the EGU interactive OA publishing approach and related initiatives aimed at opening up the review process and disclosing reviewer reports (Table 2) have paved the way during the past decades.

Recently, Nature Geoscience highlighted the key role of the EGU in shaping this development (Nature Geoscience Editorial, 2025) by stating “Publication of the exchanges between the authors and reviewers of published papers, known as transparent peer review (TPR), is a long-established practice in geoscience publishing; for example, the journals of the European Geosciences Union adopted it over 20 years ago. It is therefore not surprising that in 2021, Earth sciences was among the top disciplines for the proportion of publications in Nature (around 60 %) and Nature Communications (around 77 %) for which authors opted for TPR (Nature Communications Editorial, 2022).”

2.3 Publishing formats and platforms

2.3.1 Preprints

The idea of sharing non-peer-reviewed manuscripts, nowadays called “preprints”, within scientific communities reaches back several decades: in the 1960s, the National Institute of Health circulated manuscripts by regular mail within “Information Exchange Groups” (Green, 1964; Cobb, 2017). At the same time, researchers in the Soviet Union were encouraged to deposit their papers on VINITI for efficient dissemination (Hammarfelt and Dahlin, 2024). Similarly, in the 1970s, Ginsparg (1994) distributed manuscripts on physics- and mathematics-related topics prior to publication, which eventually led them to launch the first preprint server, arXiv, in 1991. By now the same concept is applied to numerous other discipline-specific servers2.

In parallel to arXiv, publishers launched more interdisciplinary preprint servers, e.g., SSRN (1994) (acquired by Elsevier in 2016), Nature Precedings (2007–2012) by the Nature Publishing Group, Preprints.org (2020) by MDPI, ESSOAr (2022) by Wiley/AGU and Research Square (2023) (acquired by Springer Nature in 2022). Preprint servers have also been launched by non-profit organizations such as WikiJournal Preprints (2023). To facilitate access and visibility of scientific publications in developing countries, regional initiatives started even before the official open-access initiatives (Basilio, 2023). They include the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO, 1997) of OA journals in Latin America and South Africa that was later complemented by SciELO preprints (2020). To date, the adoption and utilization of preprints greatly vary across regions and scientific disciplines (Rzayeva et al., 2025). Other research communities started promoting the advantages and benefits of preprints such as Accelerating Science and Publication in Biology (ASAPbio, 2017). In 2001, EGU/Copernicus started the interactive journal discussion forum for Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics to share papers in an interactive discussion and peer review; this concept has by now been adapted in the 18 newer EGU journals (Table A1) and complemented by the interdisciplinary preprint repository EGUsphere.

Generally, preprints are indexed in common databases (Google Scholar, Scopus, since 2017) and are thus citable as non-peer-reviewed publications, sometimes also referred to as gray literature. Both benefits and shortcomings of preprints became particularly obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic: on the one hand, the quick dissemination of novel scientific evidence was crucial to collaboratively developing solutions to the global crisis. On the other hand, the public and media are often not fully educated about the non-peer-reviewed, sometimes preliminary status of the results presented in preprints and how to interpret the published information, potentially leading to premature assessments or conclusions (Fraser et al., 2021; Drury, 2022; Schultz, 2023; Fleerackers et al., 2024; Brainard, 2025a).

To overcome the lack of quality assurance for preprints, Boldt (2011) proposed extending arXiv by a peer-review model, similar to journals; however, this idea did not succeed in the suggested form. Later, similar concepts were termed the “publish-then-review model” or peer review of preprints in “overlay journals”, in which manuscripts on preprint servers undergo peer review (Tennant et al., 2017; Rousi and Laakso, 2022) (Sect. 2.2). An example of successful overlay journals combining arXiv preprints with an interactive OA publishing concept are the SciPost Journals (2025) published since 2016 in physics and other fields, with a structure similar to that in the discussion forums of the EGU journals and EGUsphere (Sects. 3 and 4.2).

When ACP was launched in 2001 as EGU's first interactive scientific OA journal, preprints posted for public review and discussion were labeled as “discussion papers”. This labeling indicated that these papers had already passed some form of basic scientific access review by an editor, optionally supported by referees, before they were accepted for public review and discussion in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions (ACPD), the discussion forum of ACP. It is clearly indicated on all relevant web pages and through watermarks in the papers' PDF files that discussion papers are not fully peer-reviewed scientific articles as opposed to final journal papers. For clarification across and beyond the field of geosciences, this was also expressed in an official “EGU Position Statement on the Status of Discussion Papers Published in EGU Interactive Open Access Journals” (EGU News, 2010). Since ACP's launch, the community has readily embraced and accepted this distinction between discussion papers and final journal papers. In fact, ACP and EGU's interactive OA publishing initiative might not have succeeded without this clear labeling – and at that time even quite distinct typesetting – of discussion papers/preprints prior to being publicly revealed. These measures and the introduction of digital object identifiers (DOIs) and related labels effectively dispelled widespread initial concerns and misperceptions about plagiarism of preprints and introduced the novel concept of preprints with public peer review many years prior to the launch of traditional preprint servers in the Earth sciences (Pourret et al., 2021). By now, most publishers accept submissions of previously preprinted manuscripts for peer review and possible subsequent publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

To date, the more general terms “preprint” and “preprint repository” for the different types of preprints (with and without peer review) on EGUsphere (Sect. 4.2) largely replace the terms “discussion paper” and “discussion forum” across the EGU and in the wider (geo)scientific community. This adaption simplifies the terminology in the (geo)scientific publishing landscape and on the web page structures of the EGU and its publisher Copernicus. We propose, however, that the term discussion paper should not be fully abandoned as a useful label for preprints that underwent a scientific preselection process through access review by a journal editor (Sect. 3.2) and are undergoing full, public peer review (Sect. 3.3), as opposed to other traditional, stand-alone preprints that have not undergone and may never undergo any substantial scientific quality assurance. Such distinction is valuable for our understanding of an epistemic web as a dynamic and interconnected space to trace the creation, sharing and construction of knowledge.

2.3.2 Open-access publication platforms with transparent, public peer review

During the past century, different publishing formats have emerged that allow for distributing work prior to publication in scientific journals and to receive feedback by peers. An early example of discussions of unpublished work are the Faraday Discussions, a journal launched in 1947 by the Royal Society of Chemistry. It publishes research papers presented at “Faraday Discussion Meetings”, together with a record of the questions, discussion and debates that had occurred during the meeting. However, the discussion is limited to the meeting participants only and thus greatly differs from today’s public, interactive discussions on online platforms.

The potential of the internet for interactive discussions among much wider communities was recognized by Harnad (1992), who implemented the concept of “scholarly skywriting” into the OA journal Psycoloquy (discontinued as of 2002), which allowed authors to solicit feedback by peers from all over the world on their new ideas and findings. In 2002, Berkeley Electronic Press (Bepress), in collaboration with the California Digital Library, launched the eScholarship Repository to share “working papers” in the humanities and social sciences to allow for soliciting feedback before formal peer-reviewed publication3. Within the economics community, several platforms and outlets exist(ed) for the early sharing of papers. The metadata and abstracts of non-peer-reviewed working papers, published by individual research institutions, were compiled within the journal Abstracts of Working Papers in Economics (AWPE, 2004, Cambridge University Press; discontinued in 2004) that was launched in 1986 and enabled researchers to discover new work from over 70 research centers. In addition, RePEc Research Papers in Economics was launched in 1997 as an OA platform where researchers and institutions share working papers, articles and related outputs.

This early concept of an online interactive discussion in a scientific journal has further developed since then and is practiced nowadays on numerous scientific publishing platforms, as outlined below and in scientific journals, including the EGU journals. In 2012, the OA publisher F1000 launched the open research publishing platform F1000 Research for the peer review of preprints. Authors submit their manuscript for immediate posting and suggest potential reviewers. Upon a sufficient number of favorable reviewer recommendations, the paper status is considered final in order to be indexed in bibliographic databases (Scopus, etc.). Authors can upload updated versions of their manuscript at any time, even after indexing. In the same year, PeerJ was launched applying the same sequence of manuscript posting and peer review (PeerJ, 2012; Binfield, 2014). F1000 and PeerJ initially differed in their business model; the former was fully financed through article processing charges (Lawrence, 2012), and the latter applied a membership-based model for authors which was extended in 2016 to allow for payments of individual articles. Both F1000 and PeerJ were acquired by the commercial publisher Taylor & Francis in 2020 and 2024, respectively (Taylor & Francis News, 2020; PeerJ Blog, 2024).

Since 2012, several other F1000-managed platforms have been launched, e.g., Wellcome Open Research (2016), Gates Open Research (2017) and Open Research Europe (2017), the latter of which is open to all scientists funded by the European Horizon2020 program. As of 2025, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation makes the publication of preprints mandatory when they report on studies that were funded by the foundation, followed by optional peer review on their preprint platform VeriXiv (2024). The popularity of these platforms apparently stems from their OA and publish-then-review concept without charges, with peer-review rigor being a secondary criterion (Whitfield, 2012; Kirkham and Moher, 2018) These priorities frequently lead to concerns about the quality assurance on such OA publishing platforms despite the fully transparent and public peer review. In addition, Ross-Hellauer et al. (2018) raised ethical concerns with regards to funder-supported publishing platforms due to potential biases in the selection of published research results. Moreover, they warned that the quality and reputation of such platforms may decrease if authors consider such platforms as an inferior choice and would rather submit their best papers to highly prestigious journals.

Non-profit initiatives triggered the creation of funder-independent platforms. For example, the French-led Peer Community PCI (2016) facilitates open peer review of preprints deposited on the Episciences platform (CCSD, 2017), in the French “Hyper Article en Ligne” repository (HAL, 2001) or on several other preprint servers (OSF preprints, PaleorXiv, EcoEvorxiv, AfriArxiv, SocArXiv and bioRxiv). Preprints posted on these servers can then be linked to one of 19 thematic PCIs for open peer review. Upon acceptance of the paper by an editor, it can either be published at no cost in the Peer Community Journal (PCI, 2016) or transferred to a “PCI-friendly journal” for potential publication, possibly without further peer review. In 2017, about 50 preprints were submitted and also recommended; these numbers increased to 518 and 240, respectively, in 2024, with each preprint receiving two to three reviews on average. In total, about 1800 preprints were linked to the PCI platform, and 830 papers were recommended for publication in either the Peer Community Journal or in an PCI-friendly journal (about 50 % each) (PCI Facts & Figures, 2024).

The platform Review Commons (2019) was created as a joint initiative by the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) and the non-profit initiative ASAPbio and allows for open discussion and peer review of external preprints posted on bioRxiv, medRxiv and, since 2022, SciELO preprints (Lemberger and Pulverer, 2019). The authors may either transfer their peer-reviewed preprints to a Review Commons partner journal4 or just leave their archived preprints on the preprint server accompanied by the peer-review reports. The same concept of preprint peer review is applied to submissions to the JMIRx journals that require posting a preprint as a JMIR preprint or on bioRxiv or medRxiv, which then undergoes discussion in a PREreview journal club or peer review by a Plan-P-accredited service (JMIR, 2022). The JMIRx platform acts as an overlay journal and authors can select the journal in which their preprint should be peer-reviewed. On the same platform, editors can select preprints for potential peer review in their journals (Eysenbach, 2019). In 2022, the journal Society (2022) by the Microbiology Society was transitioned into an open publishing platform where all versions of an article are posted as preprints together with peer-reviewer reports. The review process concludes with an editor decision to accept a final version of the paper that is indexed in common databases. It recently joined Sciety (2025), a platform created by eLife that provides a compilation of preprints that were peer-reviewed on different platforms, including Biophysics coLab, eLife, preLights, Review Commons, ASAPbio and PeerJ.

Many publishing platforms have in common that authors suggest their peer reviewers to be nominated without further editorial selection. Such “review by endorsement” was suggested to potentially make peer review more efficient (Velterop, 2015). In 2024, F1000 introduced an editorial-led peer-reviewer selection (F1000, 2024), mainly to speed up the review process that was often delayed by having to verify author-suggested reviewers. The platform QEIOS (2019) relies entirely on reviewers selected by an artificial intelligence (AI)-based tool to identify preprint commentators. Similar as on other (e.g., F1000-managed) platforms, the review process concludes with recommendations by the reviewers only, without any final editor decision. Although QEIOS has been referred to as an innovative new journal (Columbia University, 2022), its lack of a final editor decision does not adhere to the selection criteria for scientific journals as defined by the Web of Science (Clarivate, 2024). The examples above represent (more or less) successful platforms for peer review of preprints for potential journal publication. Several of these platforms include aspects of the concept as applied in the EGU journals and their related discussion forums and preprint repository EGUsphere (Sect. 4).

Moreover, publishing platforms and preprint servers offer great opportunities for various additional purposes, including the educational value for younger scientists to discuss, evaluate and constructively criticize scientific publications as recognized by several communities. Examples include PRElights (2018), a community initiative supported by The Company of Biologists, where early-career scientists organize the discussion and highlighting of external preprints. Similarly, the PREreview (2017) initiative organizes trainings for early-career scientists, including feedback to preprint authors and collaboratively written reviewer reports on preprints in connected overlay journals. Richter et al. (2023) proposed that such journal clubs, which carry out community-based peer review, might possibly help to alleviate the burden on traditional journal-based peer review by expanding the pool of reviewers, providing timely feedback and fostering a collaborative review process.

The PubPeer platform, launched in 2012, differs from the concepts of the various publishing platforms since it only allows for discussion and review of peer-reviewed journal articles published elsewhere. It is primarily used to point out flaws or scientific fraud. Readers of the original article, however, may not be aware of these critiques because the journal websites usually do not provide a link to the discussion on PubPeer. To address this gap, a notification tool has recently been developed to establish links between the platform and the original publication (Singh Chawla, 2024).

The number of different publishing platforms (with varying rigor and procedures) and, hence, also the number of peer-reviewed preprints have sharply increased over the last few years (Brainard, 2022; Avissar-Whiting et al., 2024). Sondervan et al. (2022) and Lutz et al. (2023) provide overviews of the broad range of features, including different forms of public peer review that are offered by a few of them. They also differ in the workflows regarding how preprint metadata are stored, transferred and eventually linked to journal articles (Alves et al., 2024). Their main common feature is the fast publication and transparency in peer review, also termed “publish, review, curate” that has recently been proposed by the OA initiative Plan S as the essential standard for all OA scientific publications (Liverpool, 2023). This concept has been applied in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics since 2001 and in all other EGU journals that were launched subsequently.

2.4 Bibliometric indicators of visibility and quality: traditional measures and new opportunities

The quality and importance of scientific journals are often judged by means of the journal impact factor (JIF), which denotes the ratio of citations in a given year to citable articles published in a particular journal during the preceding 2 years. The JIF was initially developed as a guideline for librarians to select the most popular journals within a discipline (Garfield and Sher, 1963). Using the JIF as an indicator for the quality or impact of individual papers in a given journal is, thus, highly questionable and potentially even misleading because the JIF

-

does not give any direct information on the quality or impact of an individual article (Seglen, 1997; Simons, 2008; Nature Editorial, 2013; Casadevall and Fang, 2014).

-

was shown to be determined predominantly by only a small number of papers (e.g., highly cited review articles), whereas most articles belong to the “long tail” that have citation counts much lower than the JIF suggests (Triggle and Triggle, 2017; Antonoyiannakis, 2020)

-

is prone to be enhanced by way of coercive journal citation malpractices, such as excessive self-citations (citation stacking) (Kulczycki et al., 2021; Oviedo-García, 2021; Siler and Larivière, 2022) or citation cartels (Kojaku et al., 2021)

-

is particularly sensitive to the number of citable items in a journal – the denominator in the JIF calculation normally includes only papers that are classified as “articles” but excludes editorials, news items, commentaries and letters to the editor, etc., which are, however, counted in the numerator (Hernán, 2009; McVeigh and Mann, 2009; Manley, 2022)

-

may be artificially inflated by commentaries that lack genuine scientific findings and conclusions and can be AI-generated. These commentaries, often classified as opinion pieces, receive disproportionate weighting in the JIF calculation and are frequently encouraged by journals to include citations to their own articles (Joelving, 2024).

Given these shortcomings, the OA publisher PLOS refrains from reporting JIF and related journal indicators and limits their reporting to article-based measures (Public Library of Science (PLOS)). Similarly, EGU journals state on their start pages that the journals are indexed in the Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar, etc. However, the journal metrics are not prominently advertised because they do not describe the importance, impact or quality of a journal if used in isolation. Therefore, it is explicitly stated on the journal pages that the use of journal metrics is discouraged due to widely recognized limitations.

Several bibliometric measures alternative to the JIF have been suggested to account for discipline- or topic-specific citation statistics (Bornmann and Haunschild, 2016; Bornmann and Marx, 2016). The limitations of such bibliometric measures for evaluating the work of individual scientists have been acknowledged over the past decade by research funders, institutions and other entities. This recognition has prompted proposals for more equitable and comprehensive assessments of scientific influence and societal impact, accounting for the entire range of research outputs, practices and scholarly activities (Pourret et al., 2022; Triggle et al., 2022; Trueblood et al., 2025). This notion is expressed in several international declarations, including the Declaration of Research Assessment (DORA, 2012), the Leiden Manifesto (2015) and in the agreement by the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA, 2022)5.

OA publishing with interactive public discussion provides further opportunities to make scientific impact beyond traditional article-level metrics. In addition to citations, altmetric details are commonly reported as a measure of public engagement and feedback on scientific publications (Priem et al., 2010; Shuai et al., 2012; Taylor, 2023) as they account for data from social and traditional media, blogs and online reference managers (Altmetric, 2023).

The “open-access advantage” that was initially only shown in terms of higher citation counts of OA articles as compared to those in pay-walled publications (Eysenbach, 2006; Xie et al., 2021) can be extended to differences in Altmetrics (Fu and Hughey, 2019; Clayson et al., 2021; Vadhera et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2024). OA articles are not only more frequently cited in the Wikipedia encyclopedia (Teplitskiy et al., 2017) and more visible to the public via social media (Schultz, 2021), but they are also more readily accessible to policy makers (Xu and Zong, 2024). The aforementioned indicators focus on the impact of scientific papers and, thus, give recognition to their authors. However, the participation in scientific discussions can also be considered an intellectual contribution to the advancement of science. Therefore, citable peer-reviewer and community comments on preprint servers and publishing platforms, as provided in the EGU journal discussion forums and on EGUsphere, should be considered valuable as they add to scientific discourse and debates and are therefore essential elements of the epistemic web of knowledge (Fig. 1).

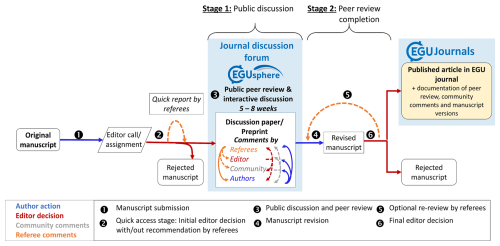

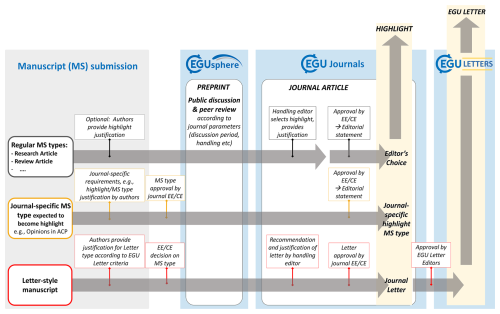

For more than two decades, the traits of publishing platforms as described in Sect. 2.3.1 and 2.3.2 have been successfully applied and combined in the EGU's multi-stage interactive publication model. In the following, we outline the steps from manuscript submission to potential final publication in the 19 EGU journals (Fig. 3).

Figure 3Schematics of the multi-stage, interactive peer-review process as applied in EGU journals; solid arrows denote mandatory steps, and dashed arrows are optional actions.

3.1 Manuscript submission

During manuscript registration, authors provide a brief summary of their article along with a statement indicating its alignment with the journal scope. At this stage, authors select prescribed subject areas for the later editor calls. In addition, authors choose the manuscript type of their paper (Sect. 4.1.2) and optionally a special issue (Sect. 4.1.3). Once submitted, manuscripts undergo an initial basic technical check (“file validation”) by the publisher's editorial support team, upon which editors of the matching subject area are informed of the submission by automatic emails and are invited on a first-come/first-served basis to handle the manuscript. If no editor agrees, editor calls are repeated several times, increasingly broadening the editorial subject areas to finally all editorial board members. If these calls are unsuccessful, the executive editors decide on how to proceed: they either reject the paper or manually assign or nominate an editor with suitable expertise and/or a low editorial workload. Manuscripts that do not find an editor during the automated calls are often found to be at the edge of the journal scope, for which no editor considers themselves an expert, or are weak papers not suitable for public discussion. In EGU journals with relatively low numbers of submissions (ESurf, GC, GChron, NPG, SOIL, SE; see Table A1 for full journal names), every submission is assigned manually to an editor by an executive editor.

3.2 Access review

As part of their initial decision, the handling editor evaluates whether the paper fulfills the main review criteria, such as the ACP review criteria:

-

Scientific significance. Does the manuscript represent a substantial contribution to scientific progress within the scope of the journal (substantial new concepts, ideas, methods or data)?

-

Scientific quality. Are the scientific approach and applied methods valid? Are the results discussed in an appropriate and balanced way (consideration of related work, including appropriate references)?

-

Presentation quality. Are the scientific results and conclusions presented in a clear, concise and well-structured way (number and quality of figures/tables, appropriate use of English language)?

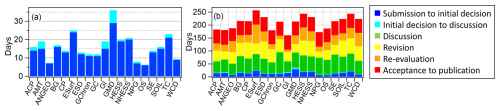

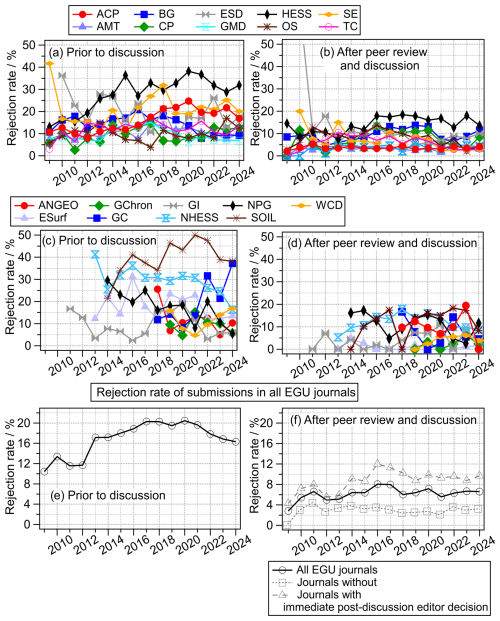

Editors are expected to make the initial decision by themselves, in particular if the paper falls into their core expertise. Editors of some journals (ACP, AMT, BG, WCD) can ask referees for a “quick report” to aid their decision. The editor and referees may provide suggestions for minor/technical corrections (e.g., typos and clarifications); any revisions beyond those are not foreseen at the access stage and lead to rejection, possibly with the option of a resubmission of a suitably revised manuscript. In the case of resubmission, the authors are asked to explain how previous criticisms were addressed. As part of their decision, the editor confirms or adjusts the manuscript category; an adjustment does not imply a rejection but may require a change of the title to include the manuscript type (e.g., technical note, measurement report or opinion in ACP; Sect. 4.1.2). Reasons for rejection during the quick access stage may include the recommendation to transfer the paper to another Copernicus journal which better fits the topic of the submitted manuscript. The rejection rate in EGU journals at the access stage is ∼ 16 % (in 2024) on average, with some differences between journals (Fig. A1), which is higher as compared to 10 % in 2009. However, a comparison of rejection rates in journals of related disciplines in 2010 showed that EGU journals had significantly lower rejection rates at that time (Schultz, 2010). The relatively low rejection rates in EGU journals suggest a form of self-regulation by the public peer-review process, which encourages authors to submit high-quality manuscripts for public discussion and to refrain from submitting poor manuscripts on a trial-and-error basis, possibly because authors may want to avoid receiving bad reviews for their papers in public.

3.3 Public discussion and peer review

After the quick access review and acceptance for public discussion, manuscripts are posted in the discussion forum of the particular journal and on EGUsphere (Sect. 4.2). A permanent DOI is assigned to the preprint and its status is indicated by the addition of [preprint] in the citation and by the DOI “egusphere-year-number” (or previously “[journal]-year-number”, discontinued as of the beginning of 2025). The duration of the public discussion phase depends on the journal and on the manuscript type and varies from 5 to 8 weeks for regular articles and 4 weeks for letter-style articles (Sect. 4.3.3). The scientific community is informed about new preprints/discussion papers and invited to contribute to their public discussion via the respective journal website and the EGUsphere website, automated alerts (upon previous sign-up), and social media. At the beginning of the discussion phase, the editor nominates referees until at least two of them agree to provide a report. For the nomination, the editor can take advantage of various search tools provided by the publisher (Sect. 4.1.5); referees who provided input at the access stage are automatically re-nominated. The editor can select numerous referees initially to be successively called in the order of their choice if one or several of them decline. To minimize the generation of unnecessary referee reports and conserve the valuable resource of referee time, the editor is notified once a sufficient number of referees has been secured. Nominated referees whose nomination deadline did not expire yet may still accept the nomination unless it is manually terminated by the editor. If the quorum of two referee reports is not fulfilled during the primal discussion period, the discussion is automatically extended, and the editor is requested to (re-)nominate additional referees. On average, each preprint receives two to three peer-reviewer reports which are published (Fig. A2). In addition, referees can send confidential comments to editors that are not publicly shared, allowing them to raise sensitive concerns.

Referees can optionally keep their identity anonymous (“single-blind review”), allowing them to provide critical comments without worrying about negative personal consequences if authors or other scientists are dissatisfied with their comments. Independent studies have shown that the option of anonymity leads to more thorough and potentially more constructive reviewer comments (Khan, 2010; Shoham and Pitman, 2021). Concerns that anonymity removes the accountability of referees and, therefore, leads to hostile comments or unsubstantiated criticisms are outweighed when all reviewer comments are publicly posted and can be checked for relevance and credibility. The option to remain anonymous is reserved for referees nominated by and known to the editors.

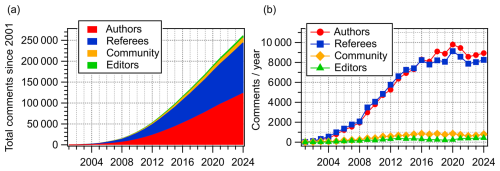

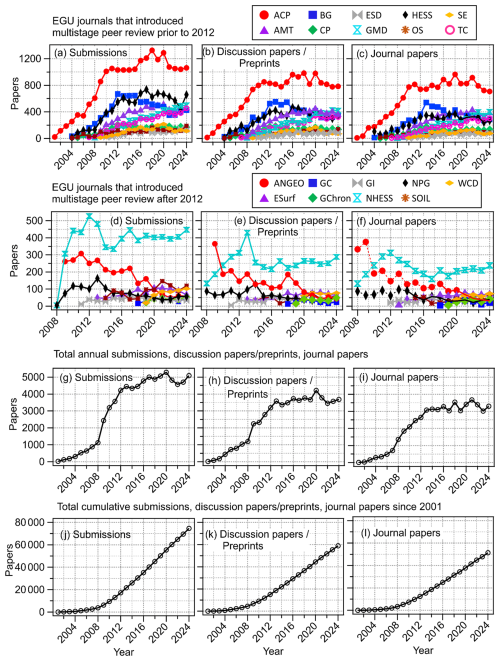

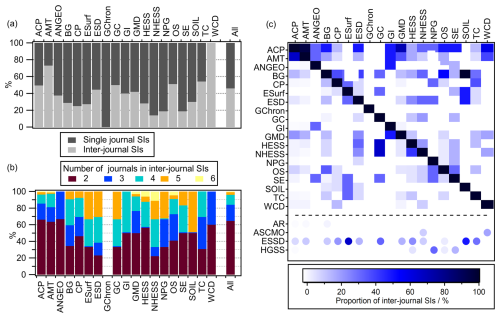

Any member of the scientific community may post eponymous comments during the discussion phase. Such community comments contribute about 5 % to all comments (3 %–17 %, depending on the journal) and are about a factor of 10 less frequent than regular referee comments (Fig. 4). Frequently, the discussions contain 20 or more comments from all involved parties (Table S2). For example, the discussion of the article by Hansen et al. (2016) with a total of 110 comments evolved among the first author, two referees, the editor and 26 additional members of the scientific community (Interactive discussion: Hansen et al., 2016). Statistics of the most commented papers in EGU journals show that these papers are often not regular research articles but opinion articles, review articles or peer-reviewed comments that may be controversial and motivate the community to contribute to the public discussion (Table S3). In many cases, the interactive discussion led to significant improvements of the paper such that several highly commented papers were finally selected as highlight articles. In other cases, however, the discussion led to the identification of major flaws in the paper so that either no revised manuscript was submitted or the revised manuscript was not accepted for final publication.

This distribution of referee, author, editorial and community comments in the interactive discussion is broadly in agreement with that in other journals with interactive platforms such as PLOS (Wakeling et al., 2019). There, most comments are made by authors or editors; attributed comments are mostly related to the publication process (language, typesetting, referencing) or to scientific or technical soundness. To stimulate scientific exchange between all parties, the authors of EGU journals are encouraged to interact with the commentators during the discussion phase, rather than just posting an author response to all comments after the end of the public discussion. Executive editors may alter or remove comments that are inappropriate, personally insulting or scientifically not relevant. However, this has been applied to a negligible number of all comments (< 0.1 %) on EGU publications. This extremely low number highlights the strength of public peer review leading to more elaborated and decent comments (Bornmann et al., 2012; Ross-Hellauer and Horbach, 2024) as compared to other journals, in which up to 62 % of all editors reported the need to modify reviewer reports for various reasons, including offensive or discriminating language (Hamilton et al., 2020).

3.4 Peer-review completion

The concept of ACP, as initially developed and still applied, foresees that the editor does not interfere between the two stages of the peer-review process (Fig. 3). An editorial decision immediately after the interactive discussion may bias the peer-review completion, for example, when the editor asks for specific changes before the authors respond to all referee and community comments and have a chance to upload a revised manuscript. Instead, ACP authors are always given the opportunity to revise their manuscript to demonstrate and enhance its quality before any editorial decision. After receiving critical feedback during the public discussion, scientists are expected to decide on their own on how to address comments and concerns. Only if necessary, e.g., if they are uncertain about whether revising their manuscript in a specific way would lead to a publishable paper, may they seek guidance from the editor. Generally, ACP authors appreciate this independence to improve their manuscript without further editorial interference. In fact, their revisions after public discussion frequently even exceed the requests and suggestions by the referees.

At present, 10 EGU journals (ANGEO, BG, CP, ESD, GC, GChron, HESS, NHESS, SOIL, TC) deviate from this original concept by imposing a mandatory editor decision after the authors have responded to the discussion comments, but prior to uploading any revised manuscript. This “post-discussion editor decision” is often felt to be disruptive when authors prepare their response to the referees and the revised manuscript simultaneously. In journals without post-discussion editor decision (ACP, AMT, ESurf, GI, GMD, NPG, OS, SE), authors are always given the chance to revise and improve their manuscript in response to the discussion, while in the other journals, papers may be rejected at this stage, even though authors potentially may have been able to revise their manuscript satisfactorily. Such rejections prior to manuscript revision may (in part) explain the higher average post-discussion rejection rates (∼ 10 % vs. ∼ 4 %, Fig. A1f) and longer processing times (Sect. 4.1.6) in these journals as compared to those that forgo early editor interference.

3.5 Optional re-review by referees

When the authors upload their documents for peer-review completion, which includes a point-to-point response to all comments as well as the revised manuscript (including a version with changes tracked), the handling editor is automatically informed. The editor makes a decision with or without consulting with previous or new referees; this decision may include the request for further revisions. If required, the process of re-review and revision can be iterated multiple times. However, in the interest of processing times, the iterations should be limited and terminated if it becomes clear that further revision will not result in a paper version that may eventually be acceptable for publication.

3.6 Final editor decision

After the revisions by the authors, the editor makes their final decision on acceptance or rejection. In the case of acceptance, all editor and referee reports, manuscript versions, and author responses that were prepared during the peer-review completion stage are made public alongside the final journal paper. In the case of rejection, the editor is expected to post a public editor comment, in which they explain the reason(s) for their decision and, thus, preempt appeals or requests for clarification by the authors. Such public editor comments should also be posted if an editor decision overrules important referee comments or when referees had differing views. These comments help to explain the editor decision and give public acknowledgement to the contribution of the referees during the revision process. Thus, the active editor role in making decisions on the manuscript can be transparently tracked for all published papers. In other peer-review models, in which such editor reports are not made publicly available, the extent to which editors may act only in a judicial role is nontransparent (Tennant and Ross-Hellauer, 2020).

The low rejection rate of manuscripts after the discussion phase in EGU journals (Fig. A1b, d, f) can be attributed to two main reasons: first, the number of initial submissions of deficient manuscripts is relatively low as authors hesitate to trigger negative reviews in the public review process; second, if major deficiencies are present, they are usually either identified during the access stage or sufficiently addressed by appropriate revisions. Rejected manuscripts and their preprint DOI are permanently archived and, thus, remain accessible. Final published journal papers receive a new DOI, reflecting the journal (in the format “journal-year-firstpage”). The preprint and the previous interactive discussions are linked to the final journal publication and are accessible both via the EGUsphere and journal websites.