the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Insights into tropical cloud chemistry in Réunion (Indian Ocean): results from the BIO-MAÏDO campaign

Pamela A. Dominutti

Pascal Renard

Mickaël Vaïtilingom

Angelica Bianco

Jean-Luc Baray

Agnès Borbon

Thierry Bourianne

Frédéric Burnet

Aurélie Colomb

Anne-Marie Delort

Valentin Duflot

Stephan Houdier

Jean-Luc Jaffrezo

Muriel Joly

Martin Leremboure

Jean-Marc Metzger

Jean-Marc Pichon

Mickaël Ribeiro

Manon Rocco

Pierre Tulet

Anthony Vella

Maud Leriche

Laurent Deguillaume

We present here the results obtained during an intensive field campaign conducted in the framework of the French “BIO-MAÏDO” (Bio-physico-chemistry of tropical clouds at Maïdo (Réunion Island): processes and impacts on secondary organic aerosols' formation) project. This study integrates an exhaustive chemical and microphysical characterization of cloud water obtained in March–April 2019 in Réunion (Indian Ocean). Fourteen cloud samples have been collected along the slope of this mountainous island. Comprehensive chemical characterization of these samples is performed, including inorganic ions, metals, oxidants, and organic matter (organic acids, sugars, amino acids, carbonyls, and low-solubility volatile organic compounds, VOCs). Cloud water presents high molecular complexity with elevated water-soluble organic matter content partly modulated by microphysical cloud properties.

As expected, our findings show the presence of compounds of marine origin in cloud water samples (e.g. chloride, sodium) demonstrating ocean–cloud exchanges. Indeed, Na+ and Cl− dominate the inorganic composition contributing to 30 % and 27 %, respectively, to the average total ion content. The strong correlations between these species (r2 = 0.87, p value: < 0.0001) suggest similar air mass origins. However, the average molar ratio (0.85) is lower than the sea-salt one, reflecting a chloride depletion possibly associated with strong acids such as HNO3 and H2SO4. Additionally, the non-sea-salt fraction of sulfate varies between 38 % and 91 %, indicating the presence of other sources. Also, the presence of amino acids and for the first time in cloud waters of sugars clearly indicates that biological activities contribute to the cloud water chemical composition.

A significant variability between events is observed in the dissolved organic content (25.5 ± 18.4 mg C L−1), with levels reaching up to 62 mg C L−1. This variability was not similar for all the measured compounds, suggesting the presence of dissimilar emission sources or production mechanisms. For that, a statistical analysis is performed based on back-trajectory calculations using the CAT (Computing Atmospheric Trajectory Tool) model associated with the land cover registry. These investigations reveal that air mass origins and microphysical variables do not fully explain the variability observed in cloud chemical composition, highlighting the complexity of emission sources, multiphasic transfer, and chemical processing in clouds.

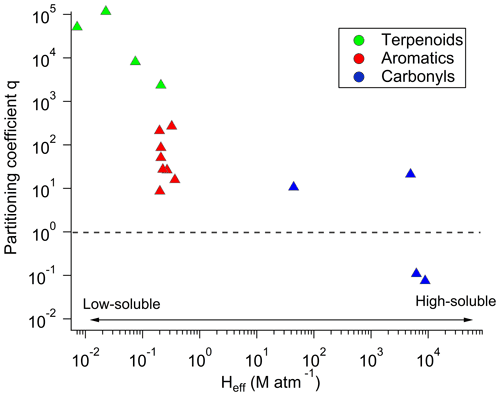

Even though a minor contribution of VOCs (oxygenated and low-solubility VOCs) to the total dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (0.62 % and 0.06 %, respectively) has been observed, significant levels of biogenic VOC (20 to 180 nmol L−1) were detected in the aqueous phase, indicating the cloud-terrestrial vegetation exchange. Cloud scavenging of VOCs is assessed by measurements obtained in both the gas and aqueous phases and deduced experimental gas-/aqueous-phase partitioning was compared with Henry's law equilibrium to evaluate potential supersaturation or unsaturation conditions. The evaluation reveals the supersaturation of low-solubility VOCs from both natural and anthropogenic sources. Our results depict even higher supersaturation of terpenoids, evidencing a deviation from thermodynamically expected partitioning in the aqueous-phase chemistry in this highly impacted tropical area.

- Article

(4668 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2993 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The chemical composition of the atmosphere modulates its impacts on the global climate, regional air pollution, human health, and ecosystems (Monks et al., 2009; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). Inorganic and organic compounds are abundant within the three atmospheric compartments: gases, aerosol particles, and clouds (liquid water and ice); they are emitted from a variety of natural and anthropogenic sources. When transported in the atmosphere, away from source regions, these compounds undergo numerous multiphasic chemical transformations. These include (i) homogeneous photochemical reactions in the gaseous phase, (ii) gas-to-particle conversion (nucleation, condensation on pre-existing particles), (iii) dissolution processes in the aqueous phase during cloud or fog events and subsequent aqueous-phase reactivity, possibly followed by a return to the atmosphere, and (iv) removal by wet deposition. Clouds are known to play an important role in atmospheric chemistry, affecting the heterogeneous gas-phase chemistry (McNeill, 2015). Indeed, cloud droplets can dissolve soluble gases and soluble parts of aerosol particles acting as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN). They represent aqueous chemical reactors where chemical and biological transformations occur, acting as sources or sinks of chemical species and altering their distribution among the various atmospheric phases (Herrmann et al., 2015). Clouds will consequently modify the physicochemical aerosol properties (oxidation state, chemical composition, hygroscopicity).

Since the late 1990s, substantial efforts have been made to further understand the chemical composition and reactivity of dissolved matter in cloud droplets through in situ measurements and laboratory investigations (Aleksic et al., 2009; Bianco et al., 2017; Brege et al., 2018; Brüggemann et al., 2005; Cini et al., 2002; Deguillaume et al., 2014; Fomba et al., 2015; Gilardoni et al., 2014; Gioda et al., 2013; Herckes et al., 2013, 2002; Hutchings et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020; van Pinxteren et al., 2016, 2020; Renard et al., 2020; Sorooshian et al., 2007; Stahl et al., 2021; Vaïtilingom et al., 2013; Viana et al., 2014). Some of these studies were focused on the role of clouds in the life cycle of inorganic compounds (i.e. ions, metals, and oxidants). The ionic composition of clouds is of substantial importance since, for example, (i) it controls the cloud water acidity (Pye et al., 2020), (ii) clouds represent the most important formation pathways for sulfate (Chin et al., 2000), and (iii) it helps to assign air mass origin (Renard et al., 2020). The characterization of strong oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide and transition metal ions, is also crucial since they participate in the oxidative capacity of the cloud water through the production of OH• radicals (Bianco et al., 2015).

Quantifying the organic matter mass distribution and composition in the different atmospheric compartments will improve the understanding and characterization of their impacts on air quality and climate. The organic carbon fraction of all atmospheric compartments comprises a large range of compounds and structures (Cook et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2013). The dissolved organic carbon (DOC) contributes not only to the hygroscopic properties of aerosols, but also to aqueous cloud chemistry (Herckes et al., 2013). In recent years, an increasing number of studies have approached the characterization of organic matter and DOC and its processing by fogs and clouds. It has been shown that fogs and clouds contain a significant amount of dissolved organic matter, ranging from 1 to as much as 200 mg C L−1 depending on the environmental conditions (Herckes et al., 2013). The highest values were observed near urban areas and in clouds impacted by biomass burning, while the lowest levels were observed in marine/remote environments (Herckes et al., 2013). However, most of these studies used a targeted analytical approach that focused on small-chain carboxylic acids, dicarboxylic acids, and carbonyls (Deguillaume et al., 2014; Löflund et al., 2002). These compounds have been selected for several distinct reasons, non-exhaustive, including that they are present in significant concentrations, they are representative of different sources (Rose et al., 2018), and they are likely to contribute to secondary organic aerosols in the cloud and humid aerosol (aqSOA) production by aqueous-phase reactivity (Ervens et al., 2011). However, a very large fraction of DOC in clouds remains uncharacterized despite the application of a variety of targeted analytical approaches (Bianco et al., 2016; Herckes et al., 2013). Recently, non-targeted approaches using high-resolution mass spectrometry have been deployed to fully characterize the organic matter present in cloud water (Bianco et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2017; Mazzoleni et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2013). These studies have revealed the complexity of the matrices, with thousands of different compounds resulting from biogenic or anthropogenic sources and secondary products from atmospheric reactivity (Bianco et al., 2019). However, these global characterizations are still not quantitative.

Given the complexity and the evolving nature of clouds, their measurement and chemical characterization represent a challenge and have resulted in significant uncertainties in our understanding of formation/evolution processes, chemical composition, fate, as well as potential impacts. Some well-established measurement observatories located at high altitudes have been carried out in numerous studies on cloud chemical composition, such as the Puy de Dôme (PUY) observatory in France (Bianco et al., 2017; Deguillaume et al., 2014; Renard et al., 2020; Vaïtilingom et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2020), the Schmücke Mountain in Germany (Brüggemann et al., 2005; Herrmann et al., 2005; van Pinxteren et al., 2005, 2016; Roth et al., 2016; Whalley et al., 2015), East Peak in Puerto Rico (Gioda et al., 2013), Mount Tai in China (Li et al., 2017; X. H. Liu et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2012), Whiteface Mountain in New York (Aleksic et al., 2009; Dukett et al., 2011; Lance et al., 2020), Great Dun Fell in England (Choularton et al., 1997), Kleiner Feldberg in Germany (Fuzzi et al., 1994; Wobrock et al., 1994), the Po Valley (Brege et al., 2018; Gilardoni et al., 2014), and Tai Mo Shan in Hong Kong SAR (Li et al., 2020). Nevertheless, most of the aforementioned observatories are located in the mid–northern latitudes with significant influence of continental emissions from natural and anthropogenic origins. A lack of measurements is observed in the Southern Hemisphere, at tropical latitudes, and in remote marine environments. This raises some questions on the chemical composition of clouds in these regions presenting highly different environmental conditions (temperature, sun irradiation, emission sources, etc.) and on the impacts that these conditions can have on the distribution and transformations of the DOC in cloud water.

Réunion's location in the tropics offers a unique context to analyse the kinetics and photochemical processing under cloudy conditions. Moreover, due to its geographic location, climate, and topography conditions, the island provides an excellent framework to study multiphasic chemical formation processes.

We present here the results obtained during an intense field campaign conducted in the framework of the French BIO-MAÏDO project. Our study evaluates the chemical composition and physical properties of 14 cloud events collected in Réunion in March–April 2019. A highly comprehensive chemical screening has been conducted in cloud water samples including ions, metals, oxidants, and organic matter (organic acids, sugars, amino acids, carbonyls, and low-solubility volatile organic compounds, VOCs). We address here the questions concerning the variability of the chemical composition and their sources from the data obtained in several episodes concerning the physicochemical and meteorological characteristics. Finally, cloud scavenging of volatile organic compounds is assessed and compared with Henry's law equilibrium to evaluate possible supersaturation or subsaturation conditions.

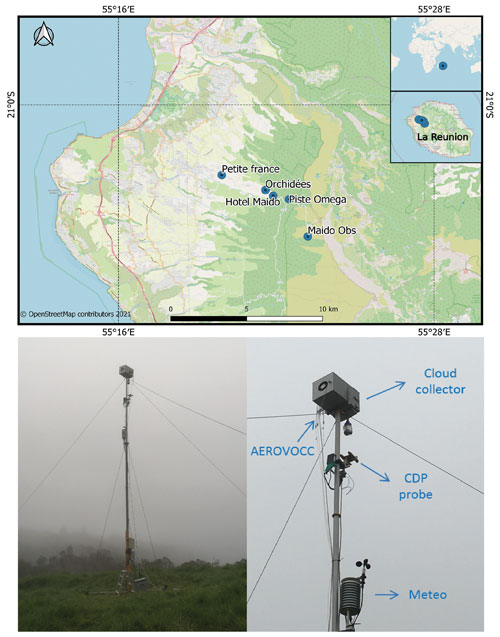

The BIO-MAÏDO field campaign was conducted between 14 March and 4 April 2019 in Réunion. During this period, several sites along the mountain slope of the Maïdo region were instrumented to evaluate chemically, physically, and biologically the different atmospheric phases and their processing (aerosol, gas, and clouds).

Réunion is a small volcanic tropical island located in the south-western Indian Ocean affected by south-easterly trade winds near the ground and westerlies in the free troposphere (Baray et al., 2013). The island encompasses 100 000 ha of native ecosystems, and it is located far from the impact of large anthropogenic emission sources (Duflot et al., 2019). Due to its abrupt topography, the collection of cloud water samples developing on the slope of the mountains can be conducted on a regular basis. The location of the island provides an original and unexplored setting to assess the combination of biogenic and marine sources and the potential interactions between both emissions.

Réunion is characterized by a complex atmospheric dynamic. During the night and early morning, air masses at sites at high altitudes are separated from local and regional sources of pollution due to the strengthening of the large-scale subtropical subsidence at night (Lesouëf et al., 2011, 2013). The cloud sampling point is located in the dry western region of the island and mainly surrounded by biogenic sources such as tropical forests characterized by the endemic tree species Acacia heterophylla (Fabaceae) and plantations of the coniferous species Cryptomeria japonica (Taxodiaceae); the Acacia heterophylla forest is locally called “Tamarinaie” (Duflot et al., 2019). The place was strategically selected as clouds develop daily on the slopes of the Maïdo region, with a well-established diurnal cycle (formation in the late morning, dissipation at the beginning of the night) (Baray et al., 2013; Lesouëf et al., 2011). Generally, these slope clouds over the Maïdo region are characterized by low vertical development and low water content. This characteristic is also conducive to the aqueous transformation of organic compounds: more UV radiation in the core of the cloud and low wet deposition by rainfall.

Figure 1Locations of Piste Omega and other instrumented sampling sites in Réunion. Photo of the mast (10 m height) deployed during the BIO-MAÏDO project integrating the cloud water collector, cloud droplet probe (“CDP”), meteorological station (“Meteo”), and gas-phase collection (“AEROVOCC”).

2.1 Sampling strategy

The sampling strategy was designed to study the chemical exchanges between the different atmospheric compartments and to evaluate the influence of sources and atmospheric dynamics on the atmosphere's composition.

Cloud sampling was performed at Piste Omega (21∘03′26′′ S, 55∘22′05′′ E) located at 1760 (above sea level) (Fig. 1). The sampling site is located in the western part of the island, along the road to the Maïdo peaks, around 5 km away from the Maïdo observatory (Baray et al., 2013). Cloud samples were obtained using a cloud collector (Deguillaume et al., 2014; Renard et al., 2020) which collects cloud droplets larger than 7 µm (estimated cut-off diameter) by impaction onto a rectangular aluminium plate (see more details in Sect. S1 in the Supplement). The cloud collector was installed at the top of a 10 m mast, and cloud water samples were obtained on an event basis. Before sampling, the cloud collector was rinsed thoroughly with Ultrapure-MiliQ water, and the aluminium plates, the funnel, and the container were autoclaved to avoid any chemical and biological contamination. Chemical and microbiological contaminations were tested at the beginning of the campaign by spreading sterilized MilliQ water on the clean cloud collector and analysing it with different approaches. Contaminant concentration was subtracted to sample concentration in the case of trace metal analysis, while it was considered to be negligible for the main inorganic and organic ions and microbial concentration. Once cloud samples were obtained, pH was determined, and the samples were filtered using a 0.20 µm nylon filter to eliminate microorganisms and micrometric particles. Cloud samples were aliquoted in vessels (plastic polypropylene, borosilicate glass) in vessels that are adapted to the chemical target and then refrigerated or frozen and stored until subsequent chemical analyses (see more details in Sect. S1).

In total, 14 cloud episodes (denoted R1 to R14) during 13 different days were collected between 14 March and 4 April 2019, with variable volumes ranging from 8 to 138 mL and an average volume of 59 ± 39 mL. For most of the samples, the volume was insufficient for all the planned targeted chemical analyses, especially for the organic characterization. Table S3 in the Supplement reports the physical and chemical characteristics of the cloud events, such as dates, sampling period, pH, liquid water content (LWC), mean effective diameter (Deff), temperature, and concentrations of chemical species: ions, oxidants (H2O2, Fe(II), Fe(III)), trace elements, sugars, monocarboxylic and dicarboxylic acids, amino acids, oxygenated VOCs (carbonyls), VOCs, and total carbon (TC), inorganic carbon (IC), and total organic carbon (TOC) concentrations.

2.2 Chemical analyses

The complete chemical screening was determined by the volume of the samples but included for most of the samples the identification and quantification of trace metals, ions, oxidants, and dissolved organic matter such as DOC, sugars, carbonyls, organic acids, low-solubility VOCs, and amino acids. Gaseous organic compounds were also measured during the cloud events to quantify the VOC partitioning between the gas and aqueous phases. Table S1 in the Supplement presents an overview of the analysis performed on each cloud water sample. A condensed summary of the analytical procedures used for the analysis is recalled below and more details about the protocols and uncertainty evaluation are given in the Supplement (Sect. S1). Limits of detection, limits of quantification, and uncertainties for each species are described in Table S2 in the Supplement.

2.2.1 Metals and oxidants in cloud water

Abundances of trace metals are analysed using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry instrument (ICP-MS, Agilent 7500). The cloud water collector being made of aluminium, this element is not quantified in the samples. More details about the instrument conditions and the analytical technique used can be found in Bianco et al. (2017).

Hydrogen peroxide and iron concentrations are analysed by UV-visible spectroscopy, applying derivatization techniques. Hydrogen peroxide in cloud water is quantified with a miniaturized Lazrus fluorimetric assay (Vaïtilingom et al., 2013; Wirgot et al., 2017).

Fe(II) concentration is quantified by UV-visible spectroscopy (λ = 562 nm), based on the rapid complexation of iron with ferrozine (Stookey, 1970). The total iron content (Fe(tot)) is detected after the reduction to Fe(II) by the addition of ascorbic acid. Fe(III) concentration is then determined by deducing the concentration of Fe(II) from Fe(tot) (Parazols et al., 2006).

TC and IC are measured with a Shimadzu TOC-L analyser. TOC quantification is then obtained by the difference between the measured TC and IC.

2.2.2 Major inorganic and organic ions in cloud water

Diluted cloud samples are analysed by ion chromatography, allowing the quantification of the major organic and inorganic ions (acetic, formic, and oxalic acids, Cl−, , , Na+, K+, , Mg2+ and Ca2+, and MSA and Br−). More details about the analytical method for ion chromatography analysis have been previously reported by Jaffrezo et al. (1998) and Bianco et al. (2018).

2.2.3 Organic matter in cloud water

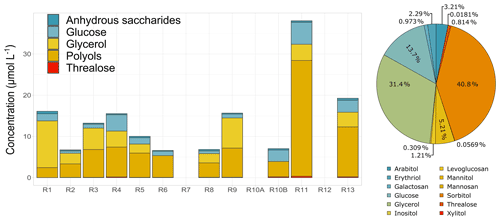

Anhydro sugars, sugar alcohols, and primary saccharides are analysed by HPLC with amperometric detection (PAD), allowing us to quantify anhydrous saccharides (levoglucosan, mannosan, galactosan), polyols (arabitol, sorbitol, mannitol, erythritol, and xylitol), glucose, and trehalose (Samaké et al., 2019b).

The analysis of a large array of organic acids (including pinic acid, phthalic acids, and 3-MBTCA, 3-methyl-1,2,3-butanetricarboxylic acid) is conducted using the same water extracts as for IC and HPLC-PAD analyses. This is performed by HPLC-MS with negative-mode electrospray ionization (Borlaza et al., 2021).

Carbonyl compounds are analysed after derivatization by fluorescent dansylacetamidooxyamine (DNSAOA), an oxyamino reagent that is specific to carbonyl compounds (Houdier et al., 2000). Derivatization reactions are performed in the presence of anilinium chloride (AnCl) as a catalyst (Houdier et al., 2018). This original approach, coupling both AnCl-catalysed derivatization and the use of HPLC-MS, allows us to quantify (i) single aldehydes (formaldehyde, F, and acetaldehyde, A), (ii) polyfunctional aldehydes (hydroxyacetaldehyde, HyA, glyoxal, GL, and methylglyoxal, MGL), and (iii) ketones (acetone, AC, and hydroxyacetone, HyAC). To the best of our knowledge, this work provides the first measurements of HyAc in environmental water samples.

A total of 15 amino acids (Ala, Arg, Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Gly, His, Lys, Met, Phe, Ser, Thr, Trp, Tyr) are quantified in 12 cloud samples (R1, R2, R3, R4, R5, R7, R8, R9, R10A, R10B, R11, R13) by UPLC-HRMS (ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry). As the standard addition method is used for the quantification, 12 samples ready for UPLC-HRMS analysis are prepared to contain the original cloud water added with 19 AAs at final concentrations set to 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 150, and 500 µg L−1. Chromatographic separation of the analytes is performed on a BEH Amide/HILIC column and the MS analysis with a Q Exactive™ Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer, and the Q-Exactive ion source is equipped with electrospray ionization (ESI+). More details on the analytical method, analytical curves, and quality control procedures can be found in Renard et al. (2021).

Hydrophobic VOCs are extracted by stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) and analysed by a thermal desorber gas chromatograph coupled to a mass spectrometer (SBSE-TD-GCMS), following the optimized procedure described in Wang et al. (2020). SBSE is used to extract the VOC from the aqueous phase thanks to 126 µL stir bars coated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Extraction efficiencies by SBSE vary between 22 % and 97 %. A total of 12 aromatics and terpenoids have been detected in Réunion cloud samples.

2.2.4 Gaseous organic matter

During the cloud collection, gaseous oxygenated VOCs (OVOCs) and VOCs were simultaneously sampled for a total of seven cloud events (Table S1) with the new AEROVOCC sampler (AtmosphERic Oxygenated/Volatile Organic Compounds in Cloud). AEROVOCC collects gaseous OVOCs/VOCs by deploying simultaneously two types of sorbent tubes: Tenax® TA sorbent tubes and PFBHA (pentafluorobenzyl hydroxylamine) pre-coated Tenax® TA sorbent tubes. Tenax® is chemical inert, highly hydrophobic, and widely used for VOC measurements of more than four carbon atoms (Ras et al., 2009; Schieweck et al., 2018). PFBHA and MTBSTFA are derivatization agents specific to –C=O and –OH/–COOH functional groups, respectively. Cloud sampling is performed simultaneously with the cloud collector presented above. Tenax® TA sorbent tubes are installed at the same altitude as the cloud collector with the inlet facing downward. The whole set of tubes is placed in a stainless-steel funnel. Each tube is connected to a Gilair Plus pump (Gilian) at ground level. The three pumps are placed in a waterproof Pelicase case and provide a controlled flow rate of 100 mL min−1 for a sampling duration of 40 min. Before sampling, sorbent tubes were pre-conditioned for 5 h at 320 ∘C under a nitrogen flow of 100 mL min−1. These conditions guarantee the presence of the target OVOCs/VOCs in the blank at levels lower than the detectable mass by the TD-GC-MS, which was used for the analysis of all the samples. More details on analytical conditions can be found in Dominutti et al. (2019) and Wang et al. (2020) for low-solubility VOCs. The preparation of the tubes and the analytical conditions for OVOCs are described in the Supplement and are adapted from Rossignol et al. (2012).

2.3 Physical parameters

Microphysical parameters were measured at the sampling point during the cloud sampling. Droplet size distribution measurements were performed by a cloud droplet probe (CDP, Droplet Measurement Technologies, DMT) which was attached to the mast just below the cloud water collector (Fig. 1).

The CDP, described in Lance et al. (2010), provides a 1 Hz cloud droplet size distribution on 30 bins from 2 to 50 µm in diameter. Originally designed to equip research aircraft, this probe has been adapted for use in a fixed point. A small fan fixed just to the rear of the laser beam creates an airflow of 5 m s−1 in the sampling section. This value has been empirically determined from comparison with reference instruments such as the Fog Monitor also manufactured by DMT. This system avoids the use of an inlet which usually introduces instrumental bias when the wind direction deviates from the inlet axis (Guyot et al., 2015; Spiegel et al., 2012). The LWC, that is, the mass of water droplets per unit of volume of air, is derived from the size distribution: , where Ni is the droplet number concentration in the bin size i, Di is the droplet diameter at the centre of the bin i, and ρw is the water density. The effective diameter is calculated as .

Ancillary data also include the measurements of meteorological variables at the sampling point. Air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed were measured every 10 s during the field campaign with a PT100, a Vaisala HMP110, and a Young 12102 three-cup anemometer, respectively.

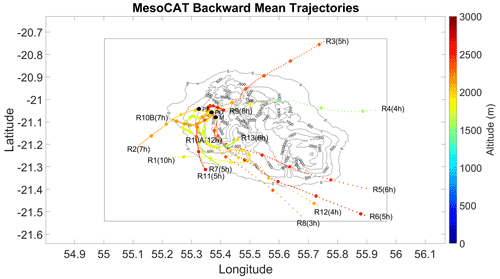

2.4 Dynamical analyses

Air mass backward trajectories are calculated with the CAT (Computing Atmospheric Trajectory Tool) model (Baray et al., 2020). A high-resolution version of CAT (MesoCAT) has been developed especially for the BIO-MAÏDO project (Rocco et al., 2021). MesoCAT assimilates wind and topography fields from the mesoscale non-hydrostatic model Meso-NH (Lac et al., 2018). For this work, we use Meso-NH 3D outputs every 1 h from a domain using a horizontal resolution of 100 m. Details of Meso-NH simulation are given in Rocco et al. (2021). In this work, backward trajectories from Piste Omega (the cloud sampling site) are computed with MesoCAT for each day when cloud samples were collected. Trajectories are calculated every 15 min from the beginning to the end of the sampling. The MesoCAT configuration includes 75 points of trajectories in a starting 3D domain of 100 m × 100 m × 50 m (latitude, longitude, altitude) around Piste Omega, and the temporal resolution and duration of back trajectories are 5 min and 12 h, respectively. The atmospheric water vapour and the cloud content parameters provided by Meso-NH are interpolated on each trajectory point. Our first insights into low-resolution back trajectories have shown that air masses are transported over the ocean and at high altitudes for almost all the cloud events (except for the R10A event). Almost all the back trajectories were over the ocean 12 h (or less) before the arrival at the sampling point (Piste Omega). We then prioritized a high-resolution approach over the island and over a short period to evaluate land–atmosphere interactions and potential effects on the cloud composition from local sources. Therefore, to estimate the influence of the soil type located under the trajectory points, an interpolation of the land zones was done using the Corinne Land Cover 2018 inventory (UE – SOeS, CORINE Land Cover, 2018, Geoportail, https://www.geoportail.gouv.fr/, last access: 10 January 2021). In total, 50 categories of land use are detailed in the land inventory. To evaluate the back trajectories during the cloud sampling, a merge of the land registry into four categories is proposed here: vegetation, urban area, coastal area, and farming area. Sensibility tests between 300 and 1000 m above ground/sea level are performed to select the maximum altitude of back trajectories. Only back-trajectory points lower than 500 m above sea or ground level are considered to be influenced by the surface and are then taken into account in the statistics to evaluate the potential contribution of emission sources to cloud chemical composition.

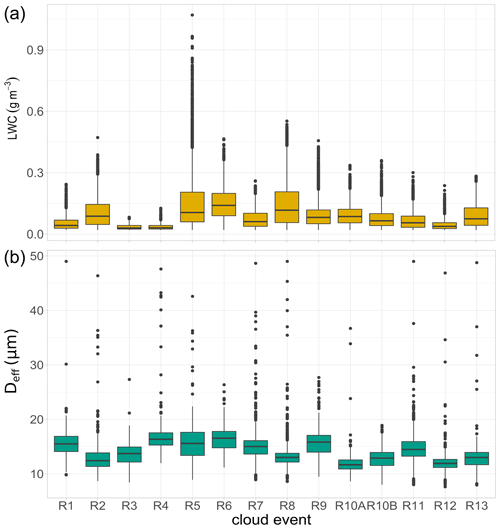

Figure 2Distribution of liquid water content (LWC) and effective diameter (Deff) of cloud droplets observed during each cloud event in Réunion. R1 to R13 refer to individual cloud samples. Lower and upper box boundaries represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; line inside box shows the median, and lower and upper error lines depict the 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively; filled black circles represent the data falling outside the 10th and 90th percentiles.

3.1 Physical parameters

Measurements of LWC and Deff were carried out during the cloud water sampling. To evaluate these microphysical parameters together with the chemical content of clouds, a “pre-treatment” was performed. To this end, CDP data were first filtered excluding the breaks effectuated during cloud sampling and considering a cut-off diameter of 7 µm of the cloud collector. Figure 2 shows the variability of LWC and Deff of droplets observed during each cloud event of this campaign. LWC exhibits a limited variation, with an average value of 0.07 ± 0.04 g m−3, ranging between 0.02 and 1.07 g m−3. The average values present lower LWC levels than those observed in previous campaigns under the marine influence: 0.19 ± 0.16 g m−3 (0.05–0.92 g m−3 for highly marine clouds) at PUY, 0.17 ± 0.13 (0.02–0.68) g m−3 at Puerto Rico, and 0.29 ± 0.10 (0.11–0.46) g m−3 at Cabo Verde (Gioda et al., 2013; Renard et al., 2020; Triesch et al., 2021). The lower LWC values observed could be related to the local atmospheric and geographical conditions, which affect the cloud formation processes over the island. The development of diurnal thermally induced circulations, combining downslope (catabatic winds) and land breezes at night and upslope (anabatic winds) and sea breezes during the day-time, causes a quasi-daily formation of clouds, which are usually weakly developed vertically with low water content (Duflot et al., 2019). Some small differences between cloud events can be noted, with particularly low LWC values observed during the R3, R4, and R12 episodes. The relationship between LWC and inorganic concentrations in cloud water has been previously addressed, showing the influence that an increase in LWC could have on the dilution of solutes in cloud water (Aleksic and Dukett, 2010). Nevertheless, this influence is not significantly observed in our study since no clear relationship was found between LWC and chemical concentrations such as total ion content (TIC, p value = 0.22) and total organic carbon (TOC, p value = 0.26). It is important to keep in mind the limited number of cloud samples collected in our study, which could not provide enough basis for drawing conclusions about LWC effects on cloud chemistry.

The effective diameter of cloud droplets was also measured. Average diameters of 13.7 ± 1.51 µm were observed, with slight variations within the cloud events. Despite the small variations in LWC and Deff between events, the time series of the microphysical parameters and cloud occurrence were strongly different among the episodes (Fig. S2 in the Supplement).

Correlations between TOC vs. LWC and Deff were investigated in order to explore the relationship between chemical content and microphysical conditions. No correlation between TOC and (r2 = 0.10 and −0.12, p values: 0.26 and 0.69, respectively) are observed from our measurements (Fig. S3 in the Supplement). This result suggests that microphysical parameters are not the main parameter regulating the organic content in cloud water, and other processes and sources are responsible for the observed levels of dissolved compounds. Further analysis of the air mass trajectories, physical variables, and chemical tracers will be discussed in Sect. 4.

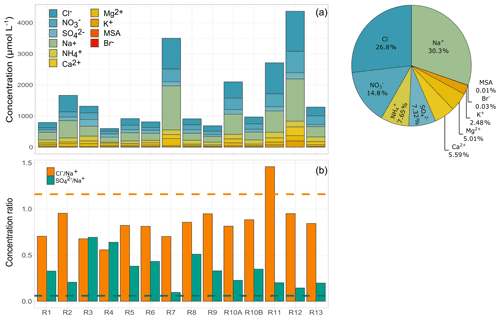

Figure 3(a) Ion concentrations observed for each cloud event and relative contribution of each species to the total average mass. R1 to R13 refer to individual cloud samples. (b) Concentration ratios of chloride to sodium and sulfate to sodium obtained in each cloud event. Dashed lines represent the reference values of seawater content (1.17, orange line, and 0.06, green line, respectively, Holland, 1978).

3.2 Inorganic chemical composition

3.2.1 Inorganic ions

Figure 3 reports the main inorganic ion concentrations (µmol L−1) and the relative contribution of all species for the 14 cloud events collected in Réunion. On average, the most abundant anions are Cl− (434 ± 370 µmol L−1) and (239 ± 168 µmol L−1), and the most abundant cations are Na+ (490 ± 399 µmol L−1) and (123 ± 43 µmol L−1). Naturally, the ionic composition of clouds in Réunion reflects the major marine influence due to the high concentrations of sea salt (Na+, Cl−) and the presence of other ions (such as ) that could also originate in the atmosphere from the marine surface. Na+ and Cl− dominate the inorganic composition, contributing 30 % and 27 %, respectively, to the average total ion content. Nitrate is the third-largest contributor (15 %), followed by ammonium (7.6 %) and sulfate (7.3 %). Chloride and sodium concentrations were similar to those reported in previous studies performed at marine sites such as in Puerto Rico (384–473 µmol L−1 for Cl− and 362–532 µmol L−1 for Na+) (Gioda et al., 2009, 2011; Reyes-Rodríguez et al., 2009) but lower sodium levels than those recently observed at Cabo Verde (870 ± 470 µmol L−1) (Triesch et al., 2021). Some mid-latitude remote sites such as the PUY observatory are regularly under the marine influence and can present elevated Cl− and Na+ concentrations, especially for air masses classified as “highly marine” in the study from Renard et al. (2020). However, the Cl− and Na+ concentrations in our study are on average, respectively, 2.6 and 2.5 times higher than those observed at PUY (for highly marine clouds). The difference could be mainly explained by the remoteness of PUY from the marine environment and/or the dilution effect at PUY (higher LWC and mean diameter, which modulate the concentrations of ions).

concentrations present higher average concentrations in Réunion than those reported in other cloud field campaigns under the marine influence. Nitrate levels are 8 to 20 times higher than those observed in cloud water at marine sites and 4 times higher than at PUY for “highly marine” clouds (Gioda et al., 2009; Renard et al., 2020; Reyes-Rodríguez et al., 2009). The detection of elevated nitrate concentrations in cloud water implies the influence of local anthropogenic sources; its contribution could be associated with the uptake of gaseous NOx/nitric acid and/or the dissolution of nitrate from aerosols (Benedict et al., 2012; Leriche et al., 2007). The observed concentrations of are lower than those observed in cloud water from polluted areas (Guo et al., 2012) but higher than or similar to those measured for remote sites in central America and Europe (Deguillaume et al., 2014; Gioda et al., 2013; van Pinxteren et al., 2016). This reflects the possible influence of terrestrial/agricultural sources (gaseous ammonia and ammonium present on aerosol). Sulfate can be emitted by marine sources and is frequently reported in cloud water observed in coastal studies (Benedict et al., 2012; Eckardt and Schemenauer, 1998; Gioda et al., 2011; Triesch et al., 2021). Average , concentrations observed in this study (118.5 ± 44.0 µmol L−1) are higher than those reported for highly marine clouds at PUY (France) and East Peak (Puerto Rico) by factors of 3.5 and 4.4, respectively (Gioda et al., 2011; Renard et al., 2020). Nevertheless, similar sulfate average concentrations were observed at a marine site in Cabo Verde (116 µmol L−1) and Tai Mo Shan in Hong Kong (152 µmol L−1) (Li et al., 2020; Triesch et al., 2021). It can be noted that non-sea-salt sulfate estimated in cloud events represents 76.2 ± 14.1 % of the total sulfate measured during our study. Thus, differences observed in sulfate levels with other marine sites could indicate the contribution of additional anthropogenic sources.

The correlation and the concentration ratios between ionic species are useful for understanding the air masses' origin and the atmospheric processes involved. The predominant species, Na+ and Cl−, present a strong correlation (r2 = 0.87, p value: < 0.0001), suggesting a similar air mass origin (Fig. S4). However, the average ratio (0.85) is lower than the sea-salt molar ratio (1.17, Holland, 1978, Fig. 3b). Ratios lower than 1 reflect chloride depletion possibly associated with the sea-salt reaction with strong acids such as HNO3 and H2SO4. This chloride depletion from sea-salt particles had already been observed and was associated with the presence of NOx and SO2 sources (Benedict et al., 2012; Gioda et al., 2009; Li et al., 2020). Regarding , exceedances of the standard sea-salt molar ratio are observed (0.06, Holland, 1978, by a factor of 2 to 8, Fig. 3b), confirming the influence of non-sea-salt sources. It is well known that the greater part of sulfate in the atmosphere (70 %) is formed in cloud droplets, and only a small portion is produced from the condensation of H2SO4 on particles or from formation in aqueous aerosol (Ervens et al., 2011; Textor et al., 2006). Thus, the sources of cloud water sulfate may include the uptake of gaseous SO2 followed by its later aqueous oxidation to H2SO4 in cloud droplets. SO2 sources include direct emissions from anthropogenic sources (shipping, vehicles, power plant emissions) and natural emissions (volcanoes and DMS oxidation) (Gondwe et al., 2003). SO2 emissions associated with volcanic eruptions have already been evaluated in Réunion. Foucart et al. (2018) have shown that SO2 levels can reach up to 500 ppb at the Maïdo observatory during volcanic activity. No volcanic eruptions were reported during our field campaign, and the observed SO2 average concentrations were 0.19 ± 0.24 ppb. Despite those low values, some higher concentrations (up to 1.2 ppb) were reported on days outside cloud sampling. Thus, the contribution of SO2 to the formation of sulfate can be neither affirmed nor ignored. The sulfate in clouds could also be associated with the scavenging of aerosol sulfate (frequently in the form of ammonium sulfate). Nevertheless, the ratio between nss- and presents average values of 1.73 ± 1.28 on a molar basis. This result corroborates the excess of sulfate in the aqueous phase, suggesting the contribution of other sources than aerosols to the clouds observed.

Other ions present in our samples (Mg2+ and K+) correlate well with Na+ (r2 = 0.90 (p value:< 0.0001), 0.51 (p value: 0.004), respectively). Magnesium-to-sodium ratios present lower values (0.07) than those expected from seawater (0.23), suggesting the depletion of Mg2+ (Fig. S4). The K+ to Na+ show contrarily an enrichment of expected ratios (0.08 vs. 0.02); a possible explanation could be the influence of biomass burning on cloud water (Urban Cerasi et al., 2012) (Fig. S4). Bromide and MSA present elevated correlations with sodium (0.92 (p value: :< 0.0001) and 0.85 (p value: 0.001), respectively), indicating the relation of these ions to seawater sources. However, their concentrations are quite low, resulting in a small contribution to the average ion total mass. Similar results have been obtained in other studies near sea sources, where MSA did not display an important contribution between the ionic species (Benedict et al., 2012; van Pinxteren et al., 2020).

An enrichment of calcium relative to seawater is also observed (0.06 vs. 0.04) with lower correlation coefficients to sodium (r2 = 0.64, p value: 0.001). The excess of Ca2+ was already observed in cloud water (Benedict et al., 2012; Straub et al., 2007), which may be associated with the soil contribution.

pH is a central component in cloud aqueous-phase chemistry since it controls mass transfer and aqueous reactivity. pH measurements were performed for each cloud sample. The pH values obtained ranged from 4.7 to 5.5, with average values of 5.25. As can be noted, the pH values present a weak variability within cloud events. Uptake of gaseous carbon dioxide is a crucial factor governing cloud pH (Verhoeven et al., 1987), especially for an area far from anthropogenic sources (remote environment). Considering the mean atmospheric CO2 level at 298 K, the calculated droplet pH is around 5.6. Cloud samples in Réunion are therefore a little bit less acidic than predicted by CO2 level. Cloud pH is mainly controlled by sulfuric and nitric acids that are strong inorganic acids and by ammonia that is the most abundant base (Pye et al., 2020). Those compounds can be the results of several processes in cloud water (scavenging of particles, aqueous-phase production, uptake from the gas phase). Even if leads to a basification of the cloud water, the presence of inorganic and organic acids tends to weakly acidify cloud water. Other ions such as Cl−, Na+, Mg2+, K+, and Ca2+ modulate H+, and the presence of weak acids (such as formic acid) can also lead to acidity buffering (Tilgner et al., 2021); this highlights the complexity of a multiphasic physicochemical processes controlling cloud water acidity.

3.2.2 Trace metals

The trace metal concentrations observed are very low, with some species frequently below the limit of quantification. It is important to note that cloud samples were filtered using a 0.2 µm filter, removing the insoluble fraction of aerosols. Figure S5 in the Supplement reports the trace metal concentrations for each cloud sample separated by concentration range. Those compounds can originate from crustal dust or particles from marine or anthropogenic sources. Mg and Zn are the most concentrated elements, observed in all the samples, and ranged from 14.1 to 3.32 and from 1.85 to 0.07 µmol L−1, respectively. Despite their low concentrations Cu, Mn, Ni, Sr, Fe, and V are among the most abundant trace metals observed. Mg and Zn come mainly from natural origin such as soil dust or sea salt. Zn can particularly be enriched in sea salt during bubble bursting (Piotrowicz et al., 1979) and is dominant in marine environments (Fomba et al., 2013). Some studies investigated the level of trace metals for marine environments and reported low concentration values for clouds (Vong et al., 1997) and aerosol particles (Fomba et al., 2013, 2020). Similar levels and distributions of trace metals have also been reported at the PUY that is importantly influenced by marine emissions (Bianco et al., 2015). The low levels observed in this study also demonstrate the low inputs of trace metals from anthropogenic sources.

Iron speciation is also evaluated (Fig. S6 in the Supplement). Soluble iron comes from its dissolution from crustal aerosols (low solubility) and anthropogenic and marine aerosols (high solubility). Its main redox forms are Fe(II) and Fe(III). This compound interacts with HxOy compounds in cloud water through a complex redox cycle converting Fe(II) into Fe(III) and reciprocally (Deguillaume et al., 2005). This leads to HO• production in cloud waters through for example the photolysis of Fe(III) and the Fenton reaction between Fe(II) and H2O2. It is expected during daytime conditions that Fe(III) is converted into Fe(II) due to efficient photochemical processes producing HOx radicals reacting with Fe(III) and due to Fe(III) photolysis. This is not systematically observed in our samples, with, on average, an ratio equal to 52 ± 22 %. This suggests that the reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) is efficient (possibly due to for example the reaction with Cu) and possible complexation of Fe(III) with organic species, stabilizing iron under this redox form (Fomba et al., 2015; Parazols et al., 2006; Vinatier et al., 2016). Moreover, iron is not expected in those cloud samples to represent a significant source of HO• radicals due to low levels of concentration (less than 0.45 µmol L−1 on average) (Bianco et al., 2015).

3.3 Dissolved organic matter in cloud water

To characterize the organic matter dissolved in cloud water, several targeted analyses were performed. These analyses allow the identification and quantification of amino acids, sugars, carboxylic acids, carbonyl compounds, and low-solubility VOCs. Those compounds have been selected for several reasons. First, they are supposed to be present in significant concentrations in the aqueous phase, based on previous studies. Second, they are known to be representative of sources (biogenic, marine, anthropogenic) or processes (chemical reactivity, biological activity) occurring within the atmosphere. Third, since the cloud medium is multiphasic, VOCs will help to evaluate the partitioning of the organic matter among the gas and liquid phases.

3.3.1 Carboxylic acids

Both short-chain monocarboxylic and dicarboxylic acids have been quantified in all the cloud water sampled in Réunion (Fig. S7 in the Supplement). Those compounds in the atmospheric aqueous phase present different sources. They come from their dissolution from the gas and particulate phases or result from chemical transformations from organic precursors in the aqueous phase (Rose et al., 2018). For example, the oxidative processing of aldehydes leads to the formation of carboxylic acids (Ervens et al., 2013; Franco et al., 2021) that can contribute to “aqSOA”.

As expected, acetic and formic acids were the dominant species in all the cloud samples (average 63.9 ± 63.8 and 22.9 ± 10.8 µmol L−1, respectively). Lactic and oxalic acids (average 5.45 ± 8.07 and 0.79 ± 0.55 µmol L−1, respectively) are the other two main carboxylic acids. Oxalic acid is the smallest dicarboxylic acid with concentrations much lower than formic and acetic acids ranging from 0.27 to 1.78 µmol L−1. The contribution of light acids has also been observed in recent studies in marine environments, where those species dominate the organic contribution to TOC (Boris et al., 2018; Stahl et al., 2021). Finally, malonic, succinic, and malic acids account for ∼ 70 % of the less concentrated dicarboxylic acid fraction. Dicarboxylic acids represent on average 8.5 % of the total measured carboxylic acids.

Acetic and formic acids can be emitted directly by anthropogenic and biogenic sources in gas or particulate phases and then diluted into the aqueous phase (Chebbi and Carlier, 1996) or they can be a result of chemical processing from organic oxygenated precursors (Charbouillot et al., 2012). Several in situ studies demonstrated that the source by mass transfer from the gas phase into the aqueous phase is important (Leriche et al., 2007; Sanhueza et al., 1992).

In the present study, a weak correlation (r2 = 0.26, p value: 0.057) between formic and acetic acid is observed, indicating the contribution of different sources or formation pathways. The formic-to-acetic acid ratio () has been suggested as a useful indicator of direct emission sources or secondary chemical formation in the aqueous phase (Fornaro and Gutz, 2003; Wang et al., 2011). ratios lower than 1.0 indicate the contribution of primary anthropogenic emission, whereas photochemical oxidation of VOCs leads to higher concentrations of formic acid than acetic acid and, therefore, an increase in ratios (> 1.0) (Fornaro and Gutz, 2003). From our observations, a ratio lower than 1 was obtained in most of the cloud events, with the exception of events R2 and R3, where the concentrations of formic acid were most abundant. This result suggests that primary emissions could regulate the concentrations of both carboxylic acids in the aqueous phase for most of the sampled clouds. For these two events, formic acid could also be produced by the aqueous-phase oxidation of aqueous formaldehyde that strongly depends on its concentration in the gas phase. The average concentrations of acetic and formic acids observed in Réunion were much higher than those observed in previous studies performed at sites under the marine influence such as East Peak in Puerto Rico (by factors of 16.8 and 7.6 for marine clouds, respectively, Gioda et al., 2011) or the PUY observatory for clouds classified as “highly marine” (by a factor of 4.64 for acetic acid but similar levels of formic acid, Renard et al., 2020). Our values are also higher than measurements performed at the Schmücke Mountain in Germany (4.17 and 1.5 times higher for minimum average values, van Pinxteren et al., 2005) or the Tai Mo Shan in Hong Kong (by factors of 6.69 and 1.34, Li et al., 2020). These discrepancies when compared with other studies could be related to the influence of direct primary biogenic sources, such as vegetation and soil emissions (Talbot et al., 1990) and anthropogenic sources (biomass burning and/or vehicular emissions, Rosado-Reyes and Francisco, 2006; Talbot, 1995). Differences might also be related to the location of our sampling point in the tropical latitudes where photochemical processes of biogenic emissions could be enhanced, leading to formic production in the particle-aqueous phase (Y. Liu et al., 2012).

Dicarboxylic acids such as oxalate result mainly from particle dissolution and aqueous-phase reactivity (Charbouillot et al., 2012; Perri et al., 2009; Renard et al., 2015). Oxalic acid can also be produced by oligomerization from biogenic products, such as terpenes and isoprene under deliquescent conditions (Renard et al., 2015). Oxalate displays lower average concentrations than formic and acetic acids (0.79 ± 0.56 µmol L−1). These values are consistent with a study from Gioda et al. (2011), who found concentrations for a marine site equal to 0.7 ± 0.3 µmol L−1. These concentrations are lower than those observed at mid-latitude mountain sites such as the PUY observatory (2.97 ± 2.61 µmol L−1 for highly marine clouds, Renard et al., 2020), at Mount Lu in South China (4.95 µmol L−1, Sun et al., 2016), and the Schmücke Mountain in Germany (1.7–2.1 µmol L−1 range, van Pinxteren et al., 2005). As discussed in the next sections, biogenic VOCs were observed in our study, suggesting the presence of freshly formed clouds, which could impact the oligomerization and secondary formation of oxalate in the liquid and condensate phases. However, since cloud measurements were performed close to the emission sources, probably there was not enough time to observe the oxidation effects of biogenic products on oxalic acid, also considering that the concentrations of H2O2 were quite low. Malonic and succinic acids can be produced by photooxidation in the aqueous phase (Charbouillot et al., 2012). Additionally, succinic acid can be produced in marine environments by photochemical degradation of fatty acids at the sea microlayer (Kerminen et al., 2000). Malonic and succinic acids present similar or higher average concentrations in our study (1.07 ± 0.54 and 0.94 ± 0.34 µmol L−1, respectively) than at PUY (0.59 and 0.66 µmol L−1, Renard et al., 2020) and at the Schmücke Mountain (0.3–0.4, 0.3–0.5 µmol L−1, van Pinxteren et al., 2005). Future investigations using explicit cloud chemistry models could help to better understand the formation pathways of monocarboxylic and dicarboxylic acids in this tropical environment and to evaluate the contribution of aqueous-phase reactivity to the chemical budget of carboxylic acids and carbonyls (Mouchel-Vallon et al., 2017).

3.3.2 Amino acids

In recent years, several studies have been carried out to analyse free or combined amino acids (AAs) in the atmosphere for various environmental sites. Their atmospheric interest relies on the fact that AAs play a potential role in cloud formation processes (Kristensson et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013) as well as on atmospheric chemistry by reacting with atmospheric oxidants (Bianco et al., 2016). AAs also significantly contribute to organic nitrogen and carbon in atmospheric depositions and are sources of nutrients to various ecosystems. They are also known to be chemical tracers of different sources (terrestrial, biogenic, etc.) (Barbaro et al., 2011). AAs have been characterized in different atmospheric matrices such as aerosols (Mashayekhy Rad et al., 2019; Matos et al., 2016; Ruiz-Jimenez et al., 2021; Scalabrin et al., 2012), rainwaters (Xu et al., 2019), fogs (Zhang and Anastasio, 2003), and more recently cloud waters (Bianco et al., 2016; Renard et al., 2021; Triesch et al., 2021). However, due to the challenges related to cloud water sampling, little is known about the distribution and concentrations of AAs in contrasting environments.

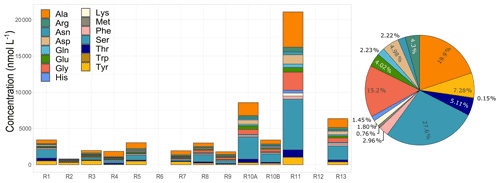

Figure 4Amino acid concentrations and total average relative contributions observed in cloud waters. R1 to R13 refer to individual cloud samples.

Here we discuss the results of 15 AAs detected in the 12 cloud events in Réunion. The AA concentrations measured are represented in Fig. 4. Significant variability in the total AA concentrations (TCAA) is observed between the cloud events, ranging from 0.81 to 21.09 µmol L−1 (66.93 to 947.6 µg C L−1). A similar range of concentrations has been observed at PUY (remote site under marine influence, France) by Bianco et al. (2016) (TCAA of 1.30 to 6.25 µmol L−1, 211 ± 12 µg C L−1) and by Renard et al. (2021) (TCAA of 1.06 to 7.86 µmol L−1, 123.97 ± 98.77 µg C L−1). In addition, a characterization of AAs was performed in cloud water samples collected at a marine site in Cabo Verde (Triesch et al., 2021). These results also showed a remarkable variability of concentrations, with values varying from 17 to 757 µg C L−1. The differences in AA concentrations between our study and those performed at PUY and Cabo Verde could be associated with the locations of the sampling points. Although all sites were remote and under the influence of marine sources, our sampling site was surrounded by biogenic sources.

Regarding the AA distribution, Ser, Ala, and Gly dominate the total average concentration in our observations by 25 %, 18 %, and 13.6 %, respectively (Fig. 4). The same three AAs, together with Asn and Ile/Leu, were also dominant in cloud water samples collected at PUY (Renard et al., 2021) and were highly present in those collected at Cabo Verde (Triesch et al., 2021). This can be explained by their lower reactivity with HO• radicals, O3, and 1O2 in atmospheric waters leading to higher mean lifetimes as described from theoretical calculations (Jaber et al., 2021a; McGregor and Anastasio, 2001; Triesch et al., 2021) and higher atmospheric concentrations. In addition, experimental work performed in microcosms mimicking cloud environments showed that the biodegradation and photodegradation rates of Ser were low; Gly could also be bio- and photo-produced under these conditions (Jaber et al., 2021b). Previous studies on aerosols have associated Gly and Ala with long-range marine aerosol transport (Barbaro et al., 2015; Mashayekhy Rad et al., 2019; Scalabrin et al., 2012) and Ser with terrestrial and marine aerosols (Mashayekhy Rad et al., 2019) and primary marine production (Scalabrin et al., 2012). However, their relative contribution is not constant throughout the field campaign. Ser and Ala are highly present all along with the campaign, reaching up to 60 % of the total AA contribution, potentially suggesting the strong influence of long-range and local transport of marine aerosols. Gly represents a considerable AA fraction (up to 15 %), but it is only observed during six cloud events, mostly observed in the last days of the campaign. A large concentration variability was also observed for Gly and Ser in clouds collected at PUY (Renard et al., 2021) and for Ala at Cabo Verde (Triesch et al., 2021). Tyr presents an opposite trend with a maximum contribution (up to 39 %) mostly during the first days. A similar pattern is also observed for Trp but with a lower concentration. Met and Trp have the lowest concentrations, similarly to clouds at PUY (Renard et al., 2021) and Cabo Verde (Triesch et al., 2021); these low concentrations are consistent with their short residence time calculated from their high reactivity with HO•, O3, and 1O2 (Jaber et al., 2021b; McGregor and Anastasio, 2001; Triesch et al., 2021). The case of Tyr is more complex as its relative concentration is higher than those of Trp and Met. Although theoretical calculations predict that Tyr is highly reactive with atmospheric oxidants and should be in very low concentrations, experimental work shows a relatively slow photo- and bio-degradation of these AAs. Tyr has been found and associated with terrestrial aerosols, indicating a combination of various sources such as plants, bacteria, and pollen (Scalabrin et al., 2012). High variability among the samples in the AA distribution was also observed in other studies at PUY and Cabo Verde. Nevertheless, globally major AAs reported by the literature agree with our observations (Renard et al., 2021; Triesch et al., 2021). A complementary analysis of AA sources is discussed in Sect. 4.2.

3.3.3 Anhydrous sugars, polyols, and saccharides

The speciation of anhydrous sugars, sugar alcohols (polyols), and primary saccharides is analysed in this study. This is the first time to our knowledge that such cloud water sugar composition has been investigated. The last two families are ubiquitous in the water-soluble fraction of atmospheric aerosols (Gosselin et al., 2016) and come from biologically derived sources (Verma et al., 2018). Some studies used those compounds as marker species to characterize and apportion primary biogenic organic aerosols (PBOAs) in the atmospheric particulate fraction (Samaké et al., 2019b, a). PBOAs integrate bacterial and fungal cells or spores, viruses, or microbial fragments such as endotoxins and mycotoxins as well as pollens and plant debris (Amato et al., 2017; Deguillaume et al., 2008). Anhydro sugars are specific tracers of different sources: levoglucosan and its isomers are indicators of biomass burning (Simoneit et al., 1999). Glucose is representative of plant material (pollens, plant debris) (Pietrogrande et al., 2014), arabitol and mannitol are sugar alcohols associated with fungi emissions (Gosselin et al., 2016), and trehalose is a metabolite of microorganisms and is suggested to be an indicator of the soil microflora (Jia et al., 2010). However, the full processes and sources associated with the presence of sugars in the atmosphere are still not fully known. Figure 5 reports the sugar concentrations identified in each cloud event and the average relative contribution for the whole campaign. Sorbitol, glycerol, glucose, and mannitol were the most abundant species observed in the cloud samples. Globally, similar total sugar concentrations were found in the cloud events, with the exception of R11, which presented higher total concentrations by a factor of 2 (Fig. 5). Even though sugars and polyols can be produced in the atmosphere because of microorganisms' activity in the aqueous phase (production and consumption), their presence in cloud water can also result from their transfer from the aerosol phase. The concentrations of total sugars in our cloud events ranged from 10.30 to 66.50 µmol L−1 (average of 22.18 ± 15.40 µmol L−1, 121.3 ± 69.56 ng m−3). These total concentrations are higher than those obtained for aerosol studies performed on the island of Chichijima (46.7 ± 49.5 ng m−3; Verma et al., 2018) and in Okinawa (62.0 ± 54.9 ng m−3; Zhu et al., 2015), both located in the western North Pacific. The higher ambient concentrations could be related to the presence of more biogenic sources in Réunion. Regarding the contribution of sugar species to the total average, we found that polyols (sugar alcohols) present the higher contribution (52 %) followed by glycerol (31 %) and glucose (13.7 %). Sorbitol presents the highest fraction, followed by glycerol, glucose, and mannitol. The study of Boris et al. (2018) has also analysed some sugar species in fog samples measured on the southern Californian coast. However, fewer sugar species have been detected, with levoglucosan being the highest contributor (0.04 µmol L−1; Boris et al., 2018). The profile observed in cloud water in Réunion is quite dissimilar to that observed in aerosol measurements, where glucose, mannitol, and arabitol present the most abundant concentrations in France (Samaké et al., 2019b), in Chichijima (Verma et al., 2018), and Okinawa (Zhu et al., 2015). Thus, this result suggests the presence of additional sources rather than aerosols in the cloud water, but their characterization needs to be further investigated.

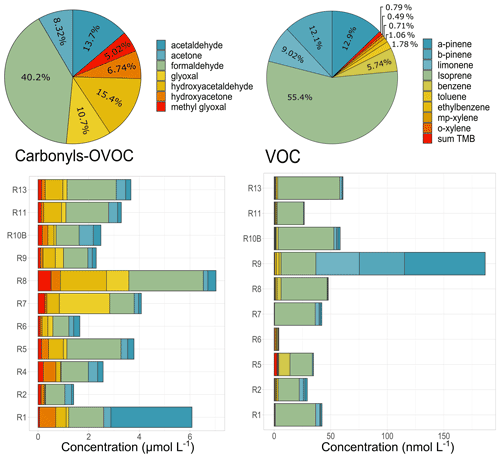

Figure 6Concentrations and total relative contributions of carbonyls (µmol L−1) and low-solubility VOC (nmol L−1) species observed in cloud waters. Sum TMB represents the sum of 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene, 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene, and 1,2,3-trimethylbenzene concentrations. R1 to R13 refer to individual cloud samples.

3.3.4 Carbonyls (OVOCs) and low-solubility VOCs

Concentrations of seven carbonyl compounds are obtained for 11 cloud samples. Total average carbonyl concentrations observed in cloud events ranged from 30.64 to 146.1 µg C L−1 (Fig. 6). Globally, formaldehyde (F, 1.40 ± 0.68 µmol L−1) presents the highest average concentrations, followed by hydroxyacetaldehyde (HyAC, 0.54 ± 0.46 µmol L−1), acetaldehyde (A, 0.48 ± 0.87 µmol L−1), and glyoxal (GL, 0.37 ± 0.56 µmol L−1). The average carbonyl concentration (75.2 ± 36.2 µg C L−1, 3.5 ± 1.7 µmol L−1) is similar to that observed for highly marine clouds at the PUY station, France (67 µg C L−1, Deguillaume et al., 2014). These values differ from the previous observations under various environmental conditions: in the Great Lakes region (12.3 µmol L−1 median concentrations, Li et al., 2008), Schmücke, Germany (3.8–10.3 µmol L−1, van Pinxteren et al., 2005), Hong Kong, China (19.4–74 µmol L−1, Li et al., 2020), and Whistler, Canada (12–25 µmol L−1, Ervens et al., 2013). For all those studies, average carbonyl concentrations are higher. These dissimilar levels could be associated with the differences in carbonyl precursors and the availability of oxidants at different locations. The tropospheric removal processes for carbonyl compounds in the gas phase are photolysis and reaction with the HO• radicals (Atkinson, 2000), but wet scavenging is also an important sink of carbonyls in the atmosphere. Indeed, carbonyls in cloud water are predominantly an outcome of their gas-phase dissolution into the aqueous phase as a result of their Henry's law constants (Deguillaume et al., 2014; Matsumoto et al., 2005). Levels of carbonyls in the aqueous phase will therefore strongly depend on their levels in the gaseous phase and on the solubility in the cloud water. Henry's law constants are quite dissimilar between carbonyl compounds, ranging from 3.2 × 103 to 9.9 × 105 for F and GL, respectively, being H(GL) > H(HyAC) > H(F) > H(AC). The discussion about the sources of carbonyls in cloud water is further given in Sect. 4.1.

As observed with other organic species, a relevant variability in terms of total concentration and speciation is observed between the cloud waters. To go further, the formaldehyde acetaldehyde ratio () has been evaluated since it is widely used as an indicator to investigate the potential sources of carbonyls. A higher ratio (up to 10) is usually observed in rural or near-forest areas because biogenic VOCs (such as isoprene) produce more formaldehyde than acetaldehyde through photochemical reactions (Shepson et al., 1991). In contrast, the ratios in areas under the influence of anthropogenic emissions are much lower (generally lower than 2), attributed to a large number of anthropogenic hydrocarbons being released (Shepson et al., 1991). In our study, the average ratio obtained for all the cloud samples was 6.7 ± 3.3, suggesting the contribution from vegetation emissions and similar to this observed in previous studies near rural areas (Yang et al., 2017). Even though most of the samples show a ratio ranging from 2.62 to 11.6, event R1 presents a dissimilar ratio of 0.43 suggesting a plausible contribution of anthropogenic emissions for this specific case.

Only a few studies have reported the presence of low-solubility VOCs in cloud water or fog droplets (effective Henry's law constant between 1.82 × 10−1 and 4.76 × 10−3 ). The compounds are from biogenic (mainly terpenoids and isoprene) and anthropogenic (mainly aromatics) sources. Even though these compounds present low concentrations in cloud waters, they have been targeted because (1) they are representative of distinct sources and (2) they present potential health and environmental effects and are transferred to the ground by rain, potentially impacting other ecosystems. For instance, measurements performed at the remote Gibbs Peak (USA) in cloud waters have shown average concentrations of ethylbenzene, o-xylene, and toluene (∼ 1.6, 4.2, and 6.5 nmol L−1, Aneja, 1993). Similarly, aromatic compounds (toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes) were detected in clouds obtained in northern Arizona. Average concentrations were 1.02, 1.08, 1.20, and 0.54 µg L−1 for toluene, ethylbenzene, m+p-xylene, and o-xylene, respectively, contributing less than 1 % to the dissolved organic carbon (Hutchings et al., 2009). A recent work reports the concentration of these compounds at PUY, presenting similar average values to those observed at Gibbs Peak (1.88–4.7 nmol L−1, Wang et al., 2020). In this study, nine different volatile organic compounds were identified in the cloud samples by applying the technique developed at PUY by Wang and co-workers (2020). They are mostly terpenoids (α-pinene, β-pinene, and limonene) and isoprene, which are released by terrestrial vegetation like conifers and deciduous trees (Fuentes et al., 2000). They are also primary aromatics (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes) usually related to fossil fuel combustion and evaporation emissions as well as solvent-use-related activities (Borbon et al., 2018). These compounds are known to be present in the gas phase and then dissolved into the aqueous phase.

Isoprene, α-pinene, and β-pinene depict the higher concentrations, with average values of 19.3 ± 6.75, 7.99 ± 21.2, and 7.45 ± 14.5 nmol L−1, respectively. Aromatics present lower concentrations, ranging between 0.29 ± 0.21 and 2.15 ± 2.02 nmol L−1. Concentrations of biogenic compounds surpass the PUY concentrations by factors of 2 to 10. Concentrations of aromatics are lower than those observed at PUY by factors of 36 for toluene, 16 for o-xylene, and 3 for benzene.

As depicted in Fig. 6, biogenic compounds dominate the VOC fraction in Réunion, suggesting the influence of emission from vegetation due to the presence of the nearby endogenous “tamarin forest”. A recent study has shown that cloud processing of isoprene products is responsible for the 20 % of the total biogenic SOA burden (Lamkaddam et al., 2021). These results raise the question about the role of terpenoids and their oxidation products in the aqSOA formation and should be further investigated.

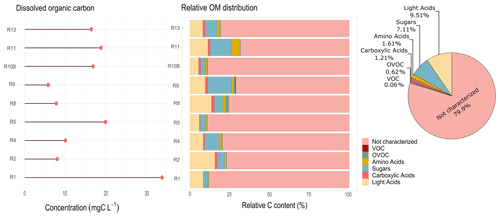

Figure 7Total dissolved organic carbon and relative contribution of organic compounds to the total organic content, observed for each cloud event and the relative average of total contributions during the field campaign in Réunion. Light acids represent the sum of major light organic acids (acetate, formate, oxalate, and lactate). R1 to R13 refer to individual cloud samples.

3.3.5 Characterization of DOC from targeted organic analyses

Figure 7a shows the total DOC observed in cloud water samples. A significant variability between events can be observed, ranging from 5.82 to 62.0 mg C L−1, with average values of 25.5 ± 19.2 mg C L−1. Herckes et al. (2013) reported in their review the various sites where TOC and DOC were measured all over the world. The TOC levels in this study are significantly higher (by a factor of 5) than those observed at PUY for highly marine clouds (Deguillaume et al., 2014). The study by Benedict et al. (2012) performed for marine cloud waters sampled in the southern Pacific Ocean shows DOC concentrations ranging from 1.32 to 3.48 mg C L−1. Even lower TOC concentrations were reported in Puerto Rico for marine clouds, which ranged from 0.15 to 0.66 mg C L−1 (Reyes-Rodríguez et al., 2009). Also, a recent airborne study by Stahl et al. (2021) in South Asia has shown TOC concentrations ranging from 0.018 to 13.66 mg C L−1. The DOC levels observed in Réunion are surprisingly high for a site under a marine influence, suggesting the contribution of important sources of DOC other than sea-related ones.

Figure 7b reports the relative characterized organic fraction associated with the DOC measured for each cloud event. Only the samples with full targeted analysis were considered here. As expected, the total characterized organic fraction is strongly variable since it depends on the dissolved organic carbon in cloud waters. On average, 20 % of the organic composition is identified during our campaign, reaching up to 35 % in some cases. Organic acids (carboxylic + light acids) and sugars depicted the maximum contribution, representing 10.72 % and 7.11 %, respectively. Carboxylic acids were also dominant contributors in the TOC concentrations obtained during the CAMP2Ex campaign in South-east Asia, where acetate, formate, and oxalate accounted for 23 % of the TOC measured (Stahl et al., 2021).

Amino acids only represent a 1.61 % contribution on average. Previous studies have shown a higher contribution of AAs to the TOC, reaching up to 10 % in marine clouds (Bianco et al., 2016). This difference could be explained by the heavier dominant AA species measured in Bianco et al. (2016) (Trp, Phe, Ile) compared with our study (Ala, Gly, and Ser) and by the lowest TOC amount at PUY for this specific study. Carbonyls and low-solubility VOCs represent the lower fraction of the total dissolved organic carbon, reaching up to 1 % for OVOCs and 0.35 % for VOCs to the total. Even though an extensive analysis of the dissolved organic matter is evaluated here, our results show that there is still a considerable fraction of OM not characterized. Further non-targeted analysis (future work) might be useful to better understand the sources and processes involved in the contribution of organic carbon in tropical-marine cloud water.

4.1 Gas-/aqueous-phase partitioning of OVOCs and low-solubility VOCs

During the BIO-MAÏDO campaign, OVOCs and low-solubility VOCs were simultaneously captured on a Tenax tube during the cloud sampling (see Sect. 2 on the AEROVOCC gaseous sampler), and the gaseous concentrations were evaluated by TD-GC-MS analysis. A recent study has shown the potentiality of the on-sorbent pre-coated PFBHA tube method (Rossignol et al., 2012). However, our tests described in the Supplement raised the critical issues associated with breakthrough volume for light OVOCs. Since the breakthrough volume limits the observed gaseous concentrations, our calculation is semi-quantitative, and the OVOC levels discussed here should be considered a lower limit (and an upper limit for partition calculations). Only a few previous studies have analysed the partitioning of these compounds between gas and aqueous phases. Thus, despite the technique's limitations for OVOCs, we have included their analysis as they could be key compounds to better understand the multiphasic cloud chemistry.

OVOC and VOC concentrations obtained are presented in Table S7 in the Supplement. This allows the evaluation of their partitioning between different atmospheric phases.

The most abundant gas-phase OVOCs are F, AC, methacrolein, butanal, and hexanal (90 %), while MGL (0.6 %) and GL (0.7 %) are the minor species. F represents between 38 % and 93 % of the total detected carbonyls, with values ranging between 0.73 and 13.6 ppb. Similarly, F dominates the carbonyl concentrations in the cloud phase. The lower concentrations of gaseous GL and MGL compared with those of formaldehyde could be associated with the oxidation yields of VOC precursors such as aromatics and terpenes or with its primary emissions (Friedfeld et al., 2002; Wolfe et al., 2016). Previous studies in Réunion have shown that gaseous formaldehyde is mainly associated with secondary biogenic products (37 %) and primary anthropogenic emissions (14 %) (Duflot et al., 2019; Rocco et al., 2020).

Low-solubility volatile compounds that have been quantified in the gas phase are from both biogenic and anthropogenic sources. Isoprene is the most abundant biogenic species, with an average mixing ratio of 109.2 ± 77.63 ppt during cloud events. Other biogenic compounds (pinenes and limonene) present lower concentrations between 4.93 and 35.8 ppt. Duflot et al. (2019) investigated the isoprene concentration over several sites in Réunion. An average concentration of 95 ppt was observed, which shows the same order of magnitude as our study (109.2 ppt, Table S7). In the Amazon forest, the concentration level of isoprene (< 500 ppt) is found to be higher, probably due to the higher emission by the vegetation (Yáñez-Serrano et al., 2015). They have also observed pinenes and limonene. The sum of concentration levels of these compounds is less than 600 ppt. This is almost twice as high as the sum of pinenes and limonene concentrations during BIO-MAÏDO. Aromatic compounds have also been detected in the gas phase during the cloud events, with benzene and toluene presenting the highest levels (233.6 ± 223.4 and 220.2 ± 129.3 ppt, respectively). These concentrations are rather low and are representative of a remote environment (Wang et al., 2020).

To investigate the partitioning of those compounds detected in parallel in both the gas and aqueous phases, q factors have been calculated for each cloud event and for each compound following Wang et al. (2020). The q factor represents the deviation from the theoretical Henry's law equilibrium of the aqueous-phase concentration of chemical species. The q factors above 1 reveal supersaturation in the aqueous phase and reciprocally. Many factors can explain these deviations, such as sampling artifacts, chemical reactivity in both phases, and kinetic limitations through the air/droplet surface. The evaluation of q factors requires the liquid water content (LWC in vol of water vol of air), the temperature, and the effective Henry's law constants at the measured temperature. q is calculated for each compound (Audiffren et al., 1998). All those data and the calculations are presented in Tables S7 and S8 in the Supplement.

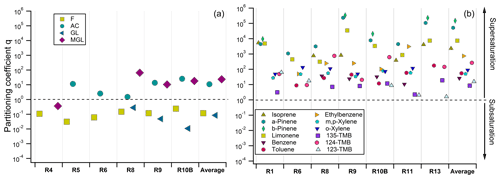

Figure 8Partitioning coefficient q factors calculated for individual cloud samples and individual OVOCs (a) and low-solubility VOCs (b), considering the average temperature and LWC measured during the sampling of each cloud event. Average corresponds to the average q factors for the cloud events. Partition coefficients are calculated when measurements in both the aqueous and gas phases were available and validated. R1 to R13 refer to individual cloud samples. More details about the samples can be found in Tables S1 and S6.

Results highlight small deviations from the equilibrium considering the Henry's law constant for OVOCs (Fig. 8). Due to the breakthrough volume issue, the reader should be aware that all the q partitioning coefficients are overestimated and have to be considered with caution. Formaldehyde is slightly unsaturated in the aqueous phase (average q factor around 0.12). Previous in situ studies emphasized that formaldehyde partitioning is governed by Henry's law equilibrium (Li et al., 2008; van Pinxteren et al., 2005) or is slightly unsaturated (Ricci et al., 1998). One explanation is relative to kinetic transport limitations through the surface of the cloud droplets that can lead to small subsaturation of species coming only from their dissolution from the gas to aqueous phases (Ervens, 2015). This can also be a reason leading to the small subsaturation of glyoxal in the aqueous phase (average q factor around 0.08) that is highly soluble (Heff between 8.0 and 9.9 × 105 M atm−1, depending on the temperature). By contrast, methylglyoxal and acetone partitioning exhibits small supersaturation (average q factor equal to 23 and 10, respectively). Supersaturations of these two compounds were also observed by van Pinxteren et al. (2005) during the FEBUKO campaign in Germany. Low-solubility biogenic and anthropogenic VOCs present much higher supersaturation in the aqueous phase, as already observed at PUY by Wang et al. (2020). We observed supersaturations in the aqueous phase of those compounds with q factors varying between 2.63 × 101 and 1.16 × 105 (Fig. 8).

Figure 9OVOC/VOC q factors averaged for all the cloud events and classified as a function of their effective Henry's law constants. Each colour represents a group of compounds, namely terpenoids (green), aromatics (red), and carbonyls (OVOCs, blue).

Figure 9 represents the mean q factors for all the studied VOCs classified as a function of their effective Henry's law constant. We observe that this factor becomes higher when the VOC solubility becomes lower. Previous studies had already reported some deviations for the expected phase-partitioning equilibrium for carboxylic acids (Facchini et al., 1992; Winiwarter et al., 1994). The supersaturation for hydrophobic compounds has been reported by Wang et al. (2020) and by Hutchings et al. (2009) in cloud water and by Glotfelty et al. (1987) and Valsaraj et al. (1993) in fog water. Many reasons have been highlighted to explain this statement, such as the possible interactions with dissolved or colloidal matter or adsorption of organic species at the air–water interface (Valsaraj et al., 1993; Wang et al., 2020). This could be possibly important in this context with the elevated level of TOC in the cloud samples. However, the reasons for the observed deviations are not fully clear and can result from both physical and chemical effects.

4.2 Environmental variability