the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Diel variation in mercury stable isotope ratios records photoreduction of PM2.5-bound mercury

Qiang Huang

Weilin Huang

John R. Reinfelder

Pingqing Fu

Shengliu Yuan

Zhongwei Wang

Wei Yuan

Hongming Cai

Hong Ren

Li He

Mercury (Hg) bound to fine aerosols (PM2.5-Hg) may undergo photochemical reaction that causes isotopic fractionation and obscures the initial isotopic signatures. In this study, we quantified Hg isotopic compositions for 56 PM2.5 samples collected between 15 September and 16 October 2015 from Beijing, China, among which 26 were collected during daytime (between 08:00 and 18:30 LT) and 30 during night (between 19:00 and 07:30 LT). The results show that diel variation was statistically significant (p < 0.05) for Hg content, Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg, with Hg content during daytime (0.32±0.14 µg g−1) lower than at night (0.48±0.24 µg g−1) and Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg values during daytime (mean of 0.26 ‰±0.40 ‰ and 0.09 ‰±0.06 ‰, respectively) higher than during nighttime (0.04 ‰±0.22 ‰ and 0.06 ‰±0.05 ‰, respectively), whereas PM2.5 concentrations and δ202Hg values showed insignificant (p > 0.05) diel variation. Geochemical characteristics of the samples and the air mass backward trajectories (PM2.5 source related) suggest that diel variation in Δ199Hg values resulted primarily from the photochemical reduction of divalent PM2.5-Hg, rather than variations in emission sources. The importance of photoreduction is supported by the strong correlations between Δ199Hg and (i) Δ201Hg (positive, slope = 1.1), (ii) δ202Hg (positive, slope = 1.15), (iii) content of Hg in PM2.5 (negative), (iv) sunshine durations (positive) and (v) ozone concentration (positive) observed for consecutive day–night paired samples. Our results provide isotopic evidence that local, daily photochemical reduction of divalent Hg is of critical importance to the fate of PM2.5-Hg in urban atmospheres and that, in addition to variation in sources, photochemical reduction appears to be an important process that affects both the particle mass-specific abundance and isotopic composition of PM2.5-Hg.

- Article

(6087 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3379 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Atmospheric mercury (Hg) consists of three operationally defined forms including particle-bound Hg (PBM), gaseous oxidized Hg (GOM) and gaseous elemental Hg (GEM) (Selin, 2009). GEM is the most abundant (about 90 %) and chemically stable form (Selin, 2009) and is transported at regional and global scales. GOM has short residence times as it can readily be dissolved in rain droplets and adsorbed on particulate matter (PM), and it reacts rapidly within both gaseous and aqueous phases with or without PM. PBM contains mainly reactive Hg species such as Hg2+ and perhaps trace quantities of Hg0 and is transported at regional or local scales, thereby reflecting Hg pollution and cycling within short distances from emission sources (Selin, 2009; Subir et al., 2012). PBM has multiple sources and undergoes complex transport and transformation processes in the atmosphere (Subir et al., 2012).

This study aimed at characterizing the isotope compositions of PM2.5-Hg (particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 µm) to better understand the complex transformation processes of PBM. Hg has seven stable isotopes and is known to exhibit both mass-dependent (MDF, represented by δ202Hg) and mass-independent fractionation (MIF, including odd-mass-number isotopic MIF, odd-MIF, and even-mass-number isotopic MIF, even-MIF, represented by Δ199Hg, Δ201Hg, Δ200Hg and Δ204Hg) during Hg transformations under various environmental conditions (Hintelmann and Lu, 2003; Jackson et al., 2004; Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Jackson et al., 2008; Gratz et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Sherman et al., 2012). Prior studies have shown that MDF can be induced by several Hg transformation and transport processes (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Kritee et al., 2007; Estrade et al., 2009; Yang and Sturgeon, 2009; Sherman et al., 2010; Wiederhold et al., 2010; Ghosh et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015; Janssen et al., 2016), but large extents of odd-MIF mainly occurred during photochemical reactions including photoreduction (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2009; Sherman et al., 2010; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2010b; Rose et al., 2015), photodemethylation (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Rose et al., 2015) and photooxidation (Sun et al., 2016). Smaller but measurable degrees of odd-MIF were also reported for nonphotochemical abiotic reduction (Zheng and Hintelmann, 2010a) and evaporation of Hg0 (Estrade et al., 2009; Ghosh et al., 2013). Interestingly, the results of laboratory and field investigations suggest that specific Δ199Hg∕Δ201Hg ratios are associated with such transformation processes, with a ratio of about 1.0 for photoreduction of inorganic Hg2+ (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2009; Sherman et al., 2010; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2010b; Rose et al., 2015), about 1.3 for photodemethylation and 1.6 for Hg0 evaporation and photooxidation (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Estrade et al., 2009; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2010a; Ghosh et al., 2013; Rose et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016). Even-MIF of Hg isotope signatures were observed mostly in wet deposition, but the mechanism producing such fractionation remains unknown (Chen et al., 2012; Cai and Chen, 2016).

Prior studies have shown relatively constant Hg isotope compositions for GEM and very large variations in Hg isotope ratios for dissolved Hg2+ in wet precipitation (Gratz et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Rolison et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015). A few studies reported that the Hg isotope compositions of PBM also show large variations (Rolison et al., 2013; Das et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017). Among these limited studies, Rolison et al. (2013) reported δ202Hg (−1.61 ‰ to −0.12 ‰) and Δ199Hg values (0.36 ‰ to 1.36 ‰ ) for Hg bound on total suspended particulates, with Δ199Hg∕Δ201Hg ratios of approximately unity, a value typical of photoreduction of inorganic Hg2+. Das et al. (2016) found values of Δ199Hg varied between −0.31 ‰ and 0.33 ‰ for PM10 from Kolkata, eastern India. It was suggested that PBM with longer residence times may have undergone greater photoreduction and hence exhibited more positive MIF. Huang et al. (2016) investigated Hg isotope compositions for PM2.5 samples taken from Beijing, China, and attributed their observed seasonal variations in both MDF (δ202Hg from −2.18 ‰ to 0.51 ‰) and MIF (Δ199Hg from −0.53 ‰ to 0.57 ‰) to varied contributions from multiple sources of PM2.5-Hg, while the more positive Δ199Hg values were likely produced by extensive photochemical reduction during long-range transport. These prior results show that the Hg isotope approach can be employed for tracking sources and identifying possible transformation processes for airborne PM-Hg, and that PBM may undergo photochemical reactions that obscure its initial isotopic signature.

The goal of this study was to quantify short-term (diel) variations in the isotope composition of PM2.5-Hg in an effort to elucidate if photochemical processes could impact overall contents and isotope compositions of PM-bound Hg in an urban environment. Unlike prior studies in which PM samples were collected continuously over 24 h or longer, we collected two PM2.5 samples per 24 h with a daytime (D) sample between 08:00 and 18:30 LT and a nighttime (N) sample between 19:00 and 19:30 LT. The specific objectives of this study were to verify and quantify whether Hg isotope compositions of PM2.5 exhibit diel variations, and to elucidate whether photochemical transformation is the dominant process for such diel variations.

2.1 Field site, sampling method and preconcentration of PM2.5-Hg

Beijing was selected as the area of study because of its well-known air pollution issue (Zhang et al., 2007). Detailed information on the study site and PM2.5 sampling procedures were given elsewhere (Huang et al., 2016). During the sampling period between 15 September and 16 October 2015, the average outdoor temperatures were 22.1±3.0 ∘C and 18.5±2.7 ∘C, and the average relative humidity were 45±20 % and 59±19 %, for D and N, respectively. The PM2.5 samples were collected using a Tisch Environmental PM2.5 high volume air sampler, which collects particles at a flow rate of 1.0 m3 min−1 through a size-selective PM2.5 inlet on a pre-combusted (450 ∘C for 6 h) quartz fiber filter (Pallflex 2500 QAT-UP, 20 cm × 25 cm, Pallflex Products Co., USA). Quartz fiber filters were widely used to collect operationally defined PBM (Schleicher et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2017). A total of 61 samples including 30 D samples and 31 N samples were collected between 08:00 and 18:30 LT and 19:00 and 07:30 LT, respectively, along with two field blanks. They were wrapped with aluminum film, packed in plastic bags, and stored at −20 ∘C in the lab prior to analysis. Meteorological data, including temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), sunshine duration and daily average wind speed (WS) were acquired from China Meteorological Administration (http://data.cma.cn, last access: 7 June 2017), and the atmospheric ozone content ( was measured concurrently. These data are summarized in Table S1.

2.2 Hg content and stable isotope measurements

The mass of each PM2.5 sample was gravimetrically quantified. Hg bound on each PM2.5 sample was extracted and concentrated for analysis of Hg content and stable Hg isotopes using the method reported previously (Huang et al., 2015). The details of the procedures are also given in the Supplement.

Among the 61 PM2.5 samples, 56 (including 26 D and 30 N samples) had sufficient Hg mass (> 10 ng) and were further analyzed for Hg isotope compositions using a multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS, Nu Instruments Ltd., UK) equipped with a continuous flow cold vapor generation system. Detailed protocols for the Hg isotope analysis can be found in Huang et al. (2015) and also in SI. 196Hg and 204Hg were not measured due to their very low abundance. Instrumental mass bias was corrected using an internal standard (NIST SRM 997 Tl) and strict sample-standard bracketing with NIST SRM 3133 Hg standard. Delta (δ) notation is used to represent MDF in units of per mill ( ‰) as defined by the following equation (Blum and Bergquist, 2007):

where x=199, 200, 201 and 202. MIF is reported as the deviation of a measured delta value from the theoretically predicted MDF value according to the following equation:

where the mass-dependent scaling factor β is 0.252, 0.5024 and 0.752 for 199Hg, 200Hg and 201Hg, respectively (Blum and Bergquist, 2007).

For quality assurance and control, we used NIST SRM 3177 Hg as a secondary standard and analyzed repeatedly during sample analysis session. The collective measurements of the NIST 3177 standard yielded average δ202Hg, Δ199Hg, Δ200Hg and Δ201Hg values of ‰, ‰, 0.00 ‰±0.04 ‰ and ‰ (2 SD, n=17). We also regularly analyzed a well-known reference material UM-Almaden and a certified reference material (CRM) GBW07405, and the results showed average δ202Hg, Δ199Hg, Δ200Hg and Δ201Hg values of ‰, ‰, 0.01 ‰±0.04 ‰ and ‰ (2 SD, n=17) and of ‰, ‰, 0.00 ‰±0.04 ‰ and ‰ (2 SD, n=6), respectively. These values were consistent with previous results (Blum and Bergquist, 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2015, 2016). The uncertainties of PM2.5-Hg isotope ratios listed in Supplement Table S2 were calculated based on repetitive measurements. However, if uncertainty of the isotopic compositions for a given sample was smaller than the uncertainty of CRM GBW07405, the uncertainty associated with that sample was assigned 2 SD uncertainties (0.14 ‰, 0.06 ‰, 0.04 ‰ and 0.07 ‰ for δ202Hg, Δ199Hg, Δ200Hg and Δ201Hg) obtained for long-term measurement of the CRM GBW07405.

2.3 Air mass backward trajectories

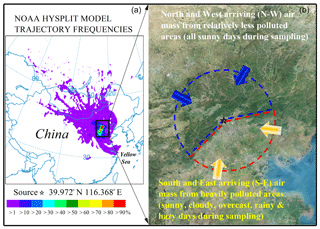

To identify possible pathways of PM2.5-Hg transport, backward HYSPLIT trajectories of air masses at a height of 500 m above ground level and air masses arriving at the sampling site were simulated. Backward trajectories for each D or N sample were calculated every 1 h using the internet-based HYSPLIT trajectory model and gridded meteorological data (Global Data Assimilation System, GDAS1) from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). The obtained average directions of arriving air masses for each sample are summarized in Table S1. The frequencies of backward trajectories were calculated for all the samples taken during 15 September to 16 October 2015 using the Internet-Based HYSPLIT Trajectory Model and the archived GDAS0p5, with an interval of 3 h. Each trajectory had a total run time of 72 h and a grid resolution of ∘ trajectory frequency. The simulation results showed the dominant air mass was arriving from southwest of the sampling site during the sampling period (see Fig. 1).

2.4 Statistical analysis

A t test was performed for uncertainty analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22. Both paired-sample t testing and independent-sample t tests were performed for diel variations in Hg content, δ202Hg, Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg, and their results are summarized in Table S3.

3.1 Diel variation in PM2.5-Hg

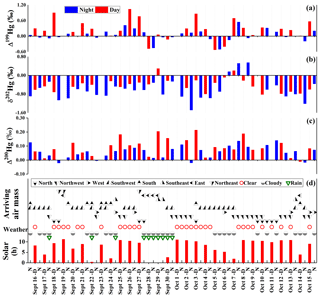

The chronological sequence of Hg stable isotope ratios, along with weather conditions for the 56 PM2.5 samples, are presented in Fig. 2 (see also Tables S1 and S2 for quantitative atmospheric data and Δ201Hg values). The major features of this dataset include (i) large variations in both MDF and odd-MIF of Hg isotopes, (ii) significant diel differences in Hg isotope ratios, (iii) correlations of weather conditions and air mass backward trajectories with Hg isotope signals, and (iv) detectable even-MIF.

Figure 2Chronological sequence of MIF (Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg) and MDF (δ202Hg) of the 56 samples collected during daytime (D, red) and nighttime (N, blue), along with selected weather data including cumulative hours of sunshine (Solar) and air mass backward-trajectory directions.

The volumetric PM2.5 concentrations ranged from 4 to 158 µg m−3 with an average value of 52±40 µg m−3 (1 SD, n=61) and the highest values (> 100 µg m−3) were detected during a severe haze event of 4–7 October. The mass-based Hg contents ranged from 0.08 to 1.22 µg g−1 with a mean value of 0.40±0.21 µg g−1 (1 SD, n=61).

Hg isotope analysis showed that δ202Hg values varied from −1.49 ‰ to 0.55 ‰ (mean ‰, 1 SD, n=56), with the lowest value found in sample Oct-2-N and the highest in Oct-8-N. Significant odd-MIF of Hg isotopes was found and the Δ199Hg values ranged from −0.53 ‰ to 1.04 ‰ (mean = 0.14 ‰±0.33 ‰) with the lowest (−0.53 ‰) Δ199Hg value on Oct-5-D during the severe haze event and the highest (1.04 ‰) Δ199Hg value on Sept-26-D during a sunny day (without cloud) (Fig. 2). All samples also displayed slight even-MIF, with Δ200Hg values ranging from −0.02 ‰ to 0.21 ‰ (average 0.07 ‰±0.06 ‰, 1 SD, n=56), which were significant compared to the detection precision of ±0.04 ‰. The overall variations in Hg isotope ratios for these 12 h D ∕ N PM2.5 samples are generally consistent with several prior reports for the 24 h PBM samples (Rolison et al., 2013; Das et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016).

The t test results (Table S3) showed that diel variation was statistically significant (p < 0.05) for Hg contents, Δ199Hg, and Δ200Hg values, as their p values are 0.005, 0.000 and 0.004 according to paired-sample t tests and are 0.003, 0.017 and 0.019 according to independent-sample t tests. For all samples, Hg contents for D samples (0.32±0.14 µg g−1) were lower than those for N samples (0.48±0.24 µg g−1), and Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg values for D samples (mean of 0.26 ‰±0.40 ‰ and 0.09 ‰±0.06 ‰, respectively) were higher than those for N samples ( and 0.06 ‰±0.05 ‰, respectively). However, PM2.5 concentrations and δ202Hg had statistically insignificant (p > 0.05) diel variation, as their p values are 0.887 and 0.052 according to paired-sample t tests and are 0.909 and 0.053 according to independent-sample t tests.

3.2 Diel variation in odd-MIF of PM2.5-Hg independent of air mass source

Many consecutive D–N sampling intervals had similar air mass backward trajectories (Table S1 and Fig. S1), suggesting that the dominant sources of PM2.5-Hg did not vary over each such 24 h sampling period. For example, pairs Sept-16-D and Sept-16-N, Sept-17-D and Sept-17-N, Sept-20-D and Sept-20-N, Sept-21-D and Sept-21-N, Oct-1-D and Oct-1-N, Oct-2-D and Oct-2-N, and Oct-4-D and Oct-4-N have similar air mass trajectories from the southwest, and pairs Oct-8-D and Oct-8-N, Oct-9-D and Oct-9-N, Oct-10-D and Oct-10-N, Oct-11-D and Oct-11-N, and Oct-12-D and Oct-12-N have similar air mass trajectories from the northwest and north (Fig. S1). It is reasonable to assume, therefore, that each of these D–N PM2.5 sample pairs had identical dominant sources of PM2.5-Hg and to expect that they would have very similar Hg isotope compositions. Instead, however, the data presented in Table S2 and Fig. 2 revealed a unique and consistent pattern of diel variation in Hg isotope ratios; specifically, each PM2.5 D sample had a statistically significantly higher positive Δ199Hg value (up to +1.04 ‰) than its consecutive PM2.5 N sample.

The more positive Δ199Hg values measured for the PM2.5 D samples are highly unlikely to be uncharacteristic of known emission sources of PM2.5-Hg. It is possible that PM2.5-Hg from different emission sources may have different Hg isotope compositions. However, prior studies showed that Δ199Hg values of the PBM from dominant anthropogenic emission sources are generally negative or close to zero. Schleicher et al. (2015) demonstrated that coal combustion is likely the major source of PM2.5-Hg in Beijing. Huang et al. (2016) reported that regional anthropogenic activities such as coal combustion (Δ199Hg values from −0.30 ‰ to 0.05 ‰), metal smelting (−0.20 ‰ to −0.05 ‰ ) and cement production (−0.25 ‰ to 0.05 ‰), as well as biomass burning (low to −0.53 ‰), were likely the dominant sources of PM2.5-Hg at this study site. As shown in Fig. 2 and Table S1, the PM2.5 D samples with high Δ199Hg values (> 0.60 ‰) each had very different air mass backward trajectories (Fig. S1). For instance, Sept-18-D (with Δ199Hg value +0.90 ‰), Sept-26-D (with Δ199Hg value +1.04 ‰) and Oct-3-D (with Δ199Hg value +0.86 ‰) were associated with north, southwest and north–south mixed air masses, respectively. A reasonable explanation of these observations is that high positive Δ199Hg values measured for D samples resulted from PM2.5-Hg transformation, specifically photoreduction, during atmospheric transport. Indeed, the diel variation in Δ199Hg for PM2.5 D–N sample pairs may well reflect strong (D) versus less or no (N) influences of photochemical reactions under time-variant local and regional weather conditions.

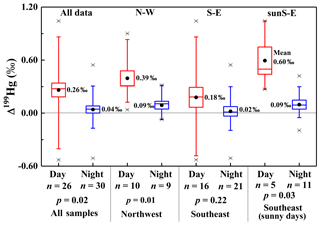

3.3 Photochemical reduction as a cause of odd-MIF in subset of daytime PM2.5 samples

To detail the effects of photochemical reactions on the variation in Hg isotope ratios for PM2.5-Hg, we regrouped our dataset into subsets corresponding to day and night. We further regrouped our results into two source-related subsets, southeast (S-E) and northwest (N-W), according to the air mass backward trajectories during each sampling event (Fig. 1), and two other subsets corresponding to sunny days within the S-E group (sunS-E) and all sunny days (Sun), which includes sunS-E and N-W as N-W consisted entirely of sunny days. The N-W subset of PM2.5 was associated with an air mass that tracked from the north, northeast, northwest and west, which are relatively less polluted areas, and is therefore representative of long-range transport and relatively constant sources of PM2.5 and Hg (Huang et al., 2016). The S-E subset was associated with an air mass that tracked from the south, southwest, southeast and east, which are heavily polluted and highly populated areas, and was characterized by relatively high contents of PM2.5, likely from industrial sources in the region (coal fired power plants, coking and steel industries). Unlike the N-W arriving air mass which corresponded to all sunny days during the entire sampling period, the S-E arriving air mass was associated with a range of weather conditions including hazy, cloudy, rainy and sunny days. According to our results (Table S2 and Fig. 2), PM2.5 concentrations of the N-W subset (23±19 µg m−3) were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than the S-E subset (69±40 µg m−3), which is consistent with the fact that the N-W areas of Beijing were less industrialized, less populated and less polluted than the S-E areas. However, regardless of whether their associated air masses originated from moderately or heavily polluted areas, both N-W and S-E subset samples showed diel variations in their Hg contents and isotope ratios (see Fig. 3 and discussion below). This, as discussed above, indicates that air mass source was not a dominant factor producing the diel variation in Hg isotope ratios in consecutive D–N PM2.5 samples.

Figure 3Diel variations in Δ199Hg for PM2.5-Hg for the entire dataset, the N-W subset, the S-E subset, and the S-E sunny days only subset. Note that all days included in the N-W subset were sunny. Diel differences within each subset were examined using the independent-sample t tests.

The observed diel difference in Δ199Hg values of PM2.5-Hg is even more prominent and statistically robust within subsets of PM2.5 samples regrouped according to their air mass trajectories (i.e., PM2.5 source related) and sunny days (with greater extent of photochemical reactions). As shown in Fig. 3, Δ199Hg values for N-W subset samples collected during the day had a higher range (0.04 ‰ to 0.90 ‰) and mean (0.39 ‰±0.27 ‰ SD, n=10) compared to those (−0.07 ‰ to 0.32 ‰, mean = 0.09 ‰±0.13 ‰ SD, n=9) for N samples (p=0.02). Similarly, analysis of the sunS-E subset revealed a significant difference in Δ199Hg values (p=0.03) between sunny days and nights, but not when the entire S-E sample set (p=0.22), which includes hazy, rainy and cloudy days, was considered. Since the N-W subset was associated with less polluted areas and the S-E subset was associated with heavily polluted and highly populated areas, the observation of significant diel variation in Δ199Hg in PM2.5-Hg within each subset (Fig. 3) is consistent with the above conclusion that such variation in PM2.5-Hg isotope ratios was not controlled by variation in Hg emission sources. The highly positive Δ199Hg values observed for daytime samples within the Sun subset (Fig. S2) further supports the conclusion that PM2.5-Hg was strongly affected by photochemical reactions on sunny days.

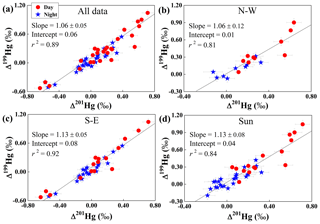

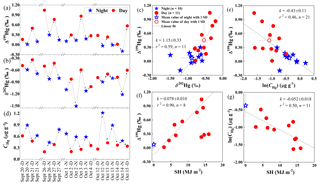

Linear correlations of Δ199Hg versus Δ201Hg for all 56 PM2.5 samples (Fig. 4a) and three subsets, N-W (Fig. 4b), S-E (Fig. 4c) and Sun (Fig. 4d), yielded slopes of 1.06±0.05 (1 SD, r2=0.89), 1.06±0.12 (r2=0.81), 1.13±0.05 (r2=0.92) and 1.13±0.08 (r2=0.84), respectively (Fig. 4). Such slopes are all indicative of photochemical reduction of Hg2+ according to prior studies (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2009). The photoreduction process is further evidenced by a progressive increase in Δ199Hg from zero or slightly negative values to positive values as the content of Hg in PM2.5 (CHg) decreased in D samples (Fig. S1a). This trend is statistically more significant (p < 0.05) for D samples within the N-W and Sun subsets (Fig. S1b and d). Similarly, for all sunny day samples, a positive correlation (p < 0.05) was also observed between Δ199Hg and δ202Hg (Fig. S3), consistent with prior experimental results (Bergquist and Blum, 2007; Zheng and Hintelmann, 2009). Collectively, the Hg isotope results suggest that photochemical reduction is an important process during the transport of PM2.5-Hg in the atmosphere.

Figure 4Correlations between Δ199Hg and Δ201Hg for different subsets of PM2.5 samples: (a) all data, (b) northwest (N-W), (c) southeast (S-E) and (d) all sunny days (Sun). The slope, intercept and r-square of the line from simple linear regression. Vertical and horizontal error bars correspond to 2 SD analytical precision.

Among all D samples, Δ199Hg is only weakly correlated with sunshine duration (r2=0.20, p=0.02). However, Δ199Hg values for all D samples collected on days with sunshine durations >8 h are positive whereas half of the Δ199Hg values for samples collected on cloudy or hazy days with shorter sunshine durations are negative or near zero (Fig. S4). In addition, a significant positive linear correlation between Δ199Hg values and atmospheric ozone contents () (r2=0.517, p<0.01) for all but four daytime samples was obtained (Fig. S5). The four outliers (Sept-16-D, Sept-17-D, Oct-5-D and Oct-6-D) were collected on days with high ozone ( above 50 ppbv) and severe smog formation. Conversely, no significant correlation (p>0.05) between Δ199Hg and was found for the nighttime samples.

The increase in Δ199Hg of daytime PM2.5-Hg with sunlight duration and ozone concentration indicates that the physical and photochemical conditions of the atmosphere may affect the atmospheric transformation of PM2.5-Hg. A prior experimental study showed that GEM oxidation can produce negative Δ199Hg values in oxidized Hg2+ with Δ199Hg∕Δ201Hg ratios of 1.6 and 1.9 for Br and Cl radical initiated oxidations (Sun et al., 2016). We can exclude the possible contribution of Hg0 oxidation to PM2.5-Hg, given the fact that Δ199Hg∕Δ201Hg ratio was about 1.1 and most PM2.5-Hg samples collected during daytime when Br and Cl radicals could form had positive Δ199Hg values. Thus it is highly unlikely that oxidation would have caused the diel variation in Hg isotopes in PM2.5. However, the exception to the observed relationships between Δ199Hg with sunlight duration and ozone concentration show that in a highly oxidizing atmosphere (higher such as occurs during extreme smog events, the odd-MIF of Hg isotopes in PM2.5 may decrease or reverse. A possible explanation for this effect may be the increased production of GOM and its collection with PM2.5-Hg during such smog events. While PM2.5-Hg samples collected on quartz fiber filters may include some GOM (Lynam and Keeler, 2002), this contribution was likely small in most of our D and N samples due to the opposing diel trends in the concentrations of PBM and GOM in urban air (Engle et al., 2010). GOM would therefore not have had a major effect on the observed diel variations in Δ199Hg values for PM2.5-Hg and may have in fact masked an even larger MIF signature due to the photoreduction of PBM during the day.

Interestingly, negative Δ199Hg values in daytime PM2.5-Hg were only observed during a rainy day and an extreme smog event. Since the Hg emitted from local sources had close to zero and negative values of odd-MIF, higher humidity (such as during rainy days) and heavy pollution (the extreme smog) may enhance the effect of scavenging of locally produced gaseous or particulate Hg during rain or smog events, which may therefore have contributed to the reversal of the odd-MIF signature of Hg collected as PM2.5 at these times. In addition, the negative Δ199Hg values in PM2.5 may have resulted from the contribution of biomass burning with limited photoreduction effect during periods of less sunshine (Fig. 2 and Table S1) since plant foliage has negative Δ199Hg values (Yu et al., 2016) and more negative Δ199Hg values (down to −0.53 ‰) of PM2.5-Hg in Beijing were related to biomass burning, a source of PM2.5-Hg south of Beijing in autumn (Huang et al., 2016). This could further explain the relatively lower Δ199Hg values in the majority of the N samples (for example, Sept-28-N and Oct-5-N with Δ199Hg of −0.46 ‰ and −0.51 ‰), even in those collected under clear weather conditions. Indeed, each bulk sample collected during night time was a mixture of the leftover PM2.5 (with positive odd-MIF) from the previous daytime and the new PM2.5 input from various sources including industrial emissions (with close to zero Δ199Hg) and biomass burning (somewhat negative Δ199Hg) (Huang et al., 2016) during nighttime.

A possible explanation of the observed effects of diel variation in PM2.5-Hg would be the temperature-dependent gas–aerosol partitioning of GOM (Rutter and Schauer, 2007; Amos et al., 2012), which favors more adsorption of GOM on PM during nighttime when atmospheric temperature us relatively lower than daytime. However, the magnitude of such adsorption is also proportional to the GOM concentration in the atmosphere. An inverse calculation exercise (in the Supplement) shows that the higher PM2.5-Hg measured for our samples would require higher GOM concentrations during nighttime, which contradicts prior findings that GOM concentrations are significantly lower during nighttime than daytime as GOM is a product of photo-oxidation processes (Poissant et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2007; Amos et al., 2012). In addition, GOM gas–aerosol partitioning is considered a chemisorption and desorption process (Rutter and Schauer, 2007), which is unlikely to result in appreciable odd-MIF of Hg isotopes (Jiskra et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2015). Therefore, GOM partitioning would have little or no effect on the observed diel variations in Δ199Hg values for PM2.5-Hg.

Variation in atmosphere boundary layer height (ABLH) from 1000 to 1300 m during daytime to less than 200 to 300 m during nighttime may have contributed to the diel variation in Hg isotopic composition of PM2.5-Hg (Quan et al., 2013). With a high ABLH during daytime, relatively strong turbulence may help in mixing the PM2.5-Hg from the surface to the upper free troposphere, where photoreactions may be favored due to higher intensities of ultraviolet radiation on clear days. In contrast, a lower ABLH at night may weaken the vertical transport of PM2.5-Hg, but enhance the contribution from newly produced PM2.5-Hg, possibly resulting in higher concentrations of PM2.5-Hg with negative or close to zero Δ199Hg values from emission sources and/or GOM. However, vertically resolved, day–night measurements of Hg stable isotope ratios in PBM and GOM are needed to fully evaluate the effects of various physical processes on diel variation in the Hg isotopic compositions for the PM2.5.

While our results cannot exclude the effects of other possible processes, such as oxidation, adsorption (and desorption) or gas–aerosol partitioning, and precipitation, based on the limited previous studies (Jiskra et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016), these processes are not likely to be important to the diel variation in odd-MIF of Hg isotopes in PM2.5-Hg we observed.

Figure 5Hg isotope ratios and contents in four subgroups of consecutive pairs of day–night samples collected during periods of relatively constant atmospheric conditions. Linear correlations between Δ199Hg and δ202Hg (c), CHg (e) and the total cumulative daily solar radiation on a horizontal surface (SH, MJ m−2) (f), and between CHg and SH (g) were displayed. The uncertainty values for measurement of Δ199Hg and δ202Hg of PM2.5 samples were 0.06 ‰ and 0.12 ‰ in 2 SD, respectively.

3.4 Photochemical reduction as a cause of diel variation in odd-MIF in day–night sample pairs of PM2.5

To explore the possible causes of diel variation in odd-MIF of Beijing PM2.5-Hg further, we examined four subgroups of PM2.5 samples, each of which included two to four consecutive pairs of D–N samples that were collected during time periods of relatively constant atmospheric conditions (i.e., not being hazy, rainy or windy or having extremely high ozone – above 50 ppbv). Within each of the four subgroups, Δ199Hg and δ202Hg values were lower at night than during the previous or following day (Fig. 5a and b). As shown in Figure 5c, there is a significant positive correlation (p<0.01) between Δ199Hg and δ202Hg values for all samples in these four subgroups, with average values for both day and night falling right on the best fit line. The slope of this line is 1.15±0.33, which is consistent with the reported value of 1.15±0.07 for photochemical reduction of Hg2+ in aqueous solution (Bergquist and Blum, 2007). Coincidently, the contents of Hg in PM2.5 (CHg) were higher in N samples than in immediately preceding or following D samples (Fig. 5d), indicating a negative linear relationship between Δ199Hg values and CHg (Fig. 5e). Moreover, 8 of the total 11 daytime samples among the four subgroups showed a positive linear correlation between Δ199Hg and the total cumulative daily solar radiation on a horizontal surface (SH) (Fig. 5f). These 11 samples also showed a negative correlation between the logarithmic values of CHg and SH (Fig. 5g). These correlations are consistent with the photochemical reduction of divalent Hg observed under laboratory conditions and thus strongly support the hypothesis that photochemical reduction is an important process controlling the fate of ambient atmospheric PM2.5-Hg. Given its diel trend and relatively large range, the MIF of odd Hg isotopes in Beijing PM2.5 we observed was most likely due to the magnetic isotope effect (MIE), which has been invoked to explain MIF during the photochemical reduction of aqueous Hg2+ (Zheng and Hintelmann, 2010b).

3.5 Even-isotope MIF

Diel variation in Δ200Hg signatures was also observed in PM2.5-Hg. Prior studies reported mainly positive Δ200Hg values for wet precipitation (up to 1.24 ‰) (Gratz et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015) and aerosols (−0.05 ‰ to 0.28 ‰) (Rolison et al., 2013; Das et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016). Even-Hg-isotope MIF has been attributed to complex redox processes occurring in the upper atmosphere, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear (Mead et al., 2013; Eiler et al., 2014). Thus, the even-MIF signatures may suggest a small proportion of PM2.5-Hg likely originated from the upper atmosphere, through for example long-term transport and/or ABLH increasing during daytime. Given the fact that all samples displayed only slightly positive Δ200Hg (average 0.07 ‰±0.06 ‰, 1 SD), this contribution may be very limited. In addition, Δ200Hg values are weakly but significantly correlated with Δ199Hg (r2=0.13, p<0.01) (Fig. S6) and δ202Hg (r2=0.27, p<0.01) (Fig. S7). No mechanistic explanation is available yet for such observations, however.

This study showed significant diel variations in Hg isotopic compositions for ambient PM2.5-Hg collected in the city of Beijing. The Hg isotope signatures featured a large range of MDF (δ202Hg value from −1.49 ‰ to 0.55 ‰, mean of ) and significant (p<0.05) MIF with more positive Δ199Hg values in daytime samples (0.26 ‰±0.40 ‰) than at night (0.04 ‰±0.22 ‰). The results clearly indicated that the Hg isotope compositions of PM2.5-Hg are impacted variously by both weather conditions (such as sunlight duration), which may promote the photochemical reaction, and directions of air mass trajectories, which are related to possible sources of PM2.5. D–N paired samples that have similar air mass backward trajectories and hence similar sources exhibited strong positive correlations between Δ199Hg and Δ201Hg with a slope of 1.1 and Δ199Hg and δ202Hg with a slope of 1.15, and a decrease in the content of Hg in PM2.5 as Δ199Hg increased. These results provide isotopic evidence that local daytime photochemical reduction of divalent Hg is of critical importance to the fate of PM2.5-Hg in urban atmosphere. Although the specific reactions and mechanisms that control Hg isotope fractionation (MDF and MIF) in Beijing PM2.5 could not be explicitly determined from this field study, our result illustrated that, in addition to variation in sources, photochemical reduction appears to be an important process that affects both the content and isotopic composition of PM2.5-Hg. Further systematic study is thus needed to better quantify the photoreduction of PM2.5-Hg to estimate the percentage of reduced Hg it produces and its impact on the global biogeochemical cycling of Hg.

Meteorological data are available from the China Meteorological Administration (http://data.cma.cn/data/cdcdetail/dataCode/A.0029.0001.html, last access: 7 June 2017). The internet-based HYSPLIT trajectory model and gridded meteorological data (Global Data Assimilation System, GDAS1) are available from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (http://ready.arl.noaa.gov, last access: 21 October 2018). All data in this study are freely available upon request to the first author via email (huangqiang@vip.gyig.ac.cn).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-315-2019-supplement.

QH, JC and PF conceived and designed this study. HR, PF and YS collected the particulate samples and supported the field observation in Beijing. SY, ZW, WY, HC and LH participated in sample treatment and measurements. QH carried out the Hg pre-concentration and measurements, data analysis and interpretation, and paper writing. WH, JRR and JC processed data analysis and interpretation and contributed to paper revision. All authors reviewed the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and

suggestions. This study was supported financially by the National Key

Research and Development Program of China (no. 2017YFC0212702), Natural

Science Foundation of China (no. 41701268, 41625012, 41273023), Guizhou

Scientific Research Program (no. 20161158) and State Key Laboratory of

Organic Geochemistry (OGL-201501).

Edited by:

Evangelos Gerasopoulos

Reviewed by: two anonymous referees

Amos, H. M., Jacob, D. J., Holmes, C. D., Fisher, J. A., Wang, Q., Yantosca, R. M., Corbitt, E. S., Galarneau, E., Rutter, A. P., Gustin, M. S., Steffen, A., Schauer, J. J., Graydon, J. A., Louis, V. L. St., Talbot, R. W., Edgerton, E. S., Zhang, Y., and Sunderland, E. M.: Gas-particle partitioning of atmospheric Hg(II) and its effect on global mercury deposition, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 12, 591–603, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-12-591-2012, 2012.

Bergquist, B. A. and Blum, J. D.: Mass-dependent and -independent fractionation of Hg isotopes by photoreduction in aquatic systems, Science, 318, 417–420, 2007.

Blum, J. D. and Bergquist, B. A.: Reporting of variations in the natural isotopic composition of mercury, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 388, 353–359, 2007.

Cai, H. and Chen, J.: Mass-independent fractionation of even mercury isotopes, Sci. Bull., 61, 116–124, 10.1007/s11434-015-0968-8, 2016.

Chen, J. B., Hintelmann, H., and Dimock, B.: Chromatographic pre-concentration of Hg from dilute aqueous solutions for isotopic measurement by MC-ICP-MS, J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom., 25, 1402–1409, 2010.

Chen, J. B., Hintelmann, H., Feng, X. B., and Dimock, B.: Unusual fractionation of both odd and even mercury isotopes in precipitation from Peterborough, ON, Canada, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 90, 33–46, 2012.

Das, R., Wang, X., Khezri, B., Webster, R. D., Sikdar, P. K., and Datta, S.: Mercury isotopes of atmospheric particle bound mercury for source apportionment study in urban Kolkata, India, Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 4, 000098, https://doi.org/10.12952/journal.elementa.000098, 2016.

Eiler, J. M., Bergquist, B., Bourg, I., Cartigny, P., Farquhar, J., Gagnon, A., Guo, W., Halevy, I., Hofmann, A., Larson, T. E., Levin, N., Schauble, E. A., and Stolper, D.: Frontiers of stable isotope geoscience, Chem. Geol., 372, 119–143, 2014.

Engle, M. A., Tate, M. T., Krabbenhoft, D. P., Schauer, J. J., Kolker, A., Shanley, J. B., and Bothner, M. H.: Comparison of atmospheric mercury speciation and deposition at nine sites across central and eastern North America, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 115, D18306, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD014064, 2010.

Estrade, N., Carignan, J., Sonke, J. E., and Donard, O. F. X.: Mercury isotope fractionation during liquid-vapor evaporation experiments, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 73, 2693–2711, 2009.

Ghosh, S., Schauble, E. A., Lacrampe Couloume, G., Blum, J. D., and Bergquist, B. A.: Estimation of nuclear volume dependent fractionation of mercury isotopes in equilibrium liquid–vapor evaporation experiments, Chem. Geol., 336, 5–12, 2013.

Gratz, L. E., Keeler, G. J., Blum, J. D., and Sherman, L. S.: Isotopic composition and fractionation of mercury in Great Lakes precipitation and ambient air, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 7764–7770, 2010.

Hintelmann, H. and Lu, S. Y.: High precision isotope ratio measurements of mercury isotopes in cinnabar ores using multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, Analyst, 128, 635–639, 2003.

Huang, Q., Liu, Y. L., Chen, J. B., Feng, X. B., Huang, W. L., Yuan, S. L., Cai, H. M., and Fu, X. W.: An improved dual-stage protocol to pre-concentrate mercury from airborne particles for precise isotopic measurement, J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom., 30, 957–966, 2015.

Huang, Q., Chen, J., Huang, W., Fu, P., Guinot, B., Feng, X., Shang, L., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Yuan, S., Cai, H., Wei, L., and Yu, B.: Isotopic composition for source identification of mercury in atmospheric fine particles, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 11773–11786, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-11773-2016, 2016.

Jackson, T. A., Muir, D. C. G., and Vincent, W. F.: Historical variations in the stable isotope composition of mercury in Arctic Lake sediments, Environ. Sci. Technol., 38, 2813–2821, 2004.

Jackson, T. A., Whittle, D. M., Evans, M. S., and Muir, D. C. G.: Evidence for mass-independent and mass-dependent fractionation of the stable isotopes of mercury by natural processes in aquatic ecosystems, Appl. Geochem., 23, 547–571, 2008.

Janssen, S. E., Schaefer, J. K., Barkay, T., and Reinfelder, J. R.: Fractionation of mercury stable isotopes during microbial methylmercury production by iron- and sulfate-reducing bacteria, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 8077–8083, 2016.

Jiskra, M., Wiederhold, J. G., Bourdon, B., and Kretzschmar, R.: Solution speciation controls mercury isotope fractionation of Hg(II) sorption to goethite, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 6654–6662, 2012.

Kritee, K., Blum, J. D., Johnson, M. W., Bergquist, B. A., and Barkay, T.: Mercury stable isotope fractionation during reduction of Hg(II) to Hg(0) by mercury resistant microorganisms, Environ. Sci. Technol., 41, 1889–1895, 2007.

Liu, B., Keeler, G. J., Dvonch, J. T., Barres, J. A., Lynam, M. M., Marsik, F. J., and Morgan, J. T.: Temporal variability of mercury speciation in urban air, Atmos. Environ., 41, 1911–1923, 2007.

Lynam, M. M. and Keeler, G. J.: Comparison of methods for particulate phase mercury analysis: Sampling and analysis, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 374, 1009–1014, 2002.

Mead, C., Lyons, J. R., Johnson, T. M., and Anbar, A. D.: Unique Hg stable isotope signatures of compact fluorescent lamp-sourced Hg, Environ. Sci. Technol., 47, 2542–2547, 2013.

Poissant, L., Pilote, M., Beauvais, C., Constant, P., and Zhang, H. H.: A year of continuous measurements of three atmospheric mercury species (GEM, RGM and Hg-p) in southern Quebec, Canada, Atmos. Environ., 39, 1275–1287, 2005.

Quan, J. N., Gao, Y., Zhang, Q., Tie, X. X., Cao, J. J., Han, S. Q., Meng, J. W., Chen, P. F., and Zhao, D. L.: Evolution of planetary boundary layer under different weather conditions, and its impact on aerosol concentrations, Particuology, 11, 34–40, 2013.

Rolison, J. M., Landing, W. M., Luke, W., Cohen, M., and Salters, V. J. M.: Isotopic composition of species-specific atmospheric Hg in a coastal environment, Chem. Geol., 336, 37–49, 2013.

Rose, C. H., Ghosh, S., Blum, J. D., and Bergquist, B. A.: Effects of ultraviolet radiation on mercury isotope fractionation during photo-reduction for inorganic and organic mercury species, Chem. Geol., 405, 102–111, 2015.

Rutter, A. P. and Schauer, J. J.: The effect of temperature on the gas–particle partitioning of reactive mercury in atmospheric aerosols, Atmos. Environ., 41, 8647–8657, 2007.

Schleicher, N. J., Schäfer, J., Blanc, G., Chen, Y., Chai, F., Cen, K., and Norra, S.: Atmospheric particulate mercury in the megacity Beijing: Spatio-temporal variations and source apportionment, Atmos. Environ., 109, 251–261, 2015.

Selin, N. E.: Global biogeochemical cycling of mercury: A review, Annu. Rev. Env. Resour., 34, 43–63, 2009.

Sherman, L. S., Blum, J. D., Johnson, K. P., Keeler, G. J., Barres, J. A., and Douglas, T. A.: Mass-independent fractionation of mercury isotopes in Arctic snow driven by sunlight, Nat. Geosci., 3, 173–177, 2010.

Sherman, L. S., Blum, J. D., Keeler, G. J., Demers, J. D., and Dvonch, J. T.: Investigation of local mercury deposition from a coal-fired power plant using mercury isotopes, Environ. Sci. Technol., 46, 382–390, 2012.

Smith, R. S., Wiederhold, J. G., and Kretzschmar, R.: Mercury isotope fractionation during precipitation of metacinnabar (β-HgS) and montroydite (HgO), Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 4325–4334, 2015.

Subir, M., Ariya, P. A., and Dastoor, A. P.: A review of the sources of uncertainties in atmospheric mercury modeling II. Mercury surface and heterogeneous chemistry – A missing link, Atmos. Environ., 46, 1–10, 2012.

Sun, G., Sommar, J., Feng, X., Lin, C.-J., Ge, M., Wang, W., Yin, R., Fu, X., and Shang, L.: Mass-dependent and -independent fractionation of mercury isotope during gas-phase oxidation of elemental mercury vapor by atomic Cl and Br, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 9232–9241, 2016.

Wang, Z., Chen, J., Feng, X., Hintelmann, H., Yuan, S., Cai, H., Huang, Q., Wang, S., and Wang, F.: Mass-dependent and mass-independent fractionation of mercury isotopes in precipitation from Guiyang, SW China, C. R. Geosci., 347, 358–367, 2015.

Wiederhold, J. G., Cramer, C. J., Daniel, K., Infante, I., Bourdon, B., and Kretzschmar, R.: Equilibrium mercury isotope fractionation between dissolved Hg(II) species and thiol-bound Hg, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 4191–4197, 2010.

Xu, H., Sonke, J. E., Guinot, B., Fu, X., Sun, R., Lanzanova, A., Candaudap, F., Shen, Z., and Cao, J.: Seasonal and annual variations in atmospheric Hg and Pb isotopes in Xi'an, China, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 3759–3766, 2017.

Yang, L. and Sturgeon, R.: Isotopic fractionation of mercury induced by reduction and ethylation, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 393, 377–385, 2009.

Yu, B., Fu, X., Yin, R., Zhang, H., Wang, X., Lin, C.-J., Wu, C., Zhang, Y., He, N., Fu, P., Wang, Z., Shang, L., Sommar, J., Sonke, J. E., Maurice, L., Guinot, B., and Feng, X.: Isotopic composition of atmospheric mercury in China: New evidence for sources and transformation processes in air and in vegetation, Environ. Sci. Technol., 50, 9262–9269, 2016.

Yuan, S., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Kang, S., Zhang, J., Feng, X., Cai, H., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., and Huang, Q.: Large variation of mercury isotope composition during a single precipitation event at Lhasa city, Tibetan Plateau, China, Proced. Earth Plan. Sc., 13, 282–286, 2015.

Zhang, L., Wang, S. X., Wang, L., Wu, Y., Duan, L., Wu, Q. R., Wang, F. Y., Yang, M., Yang, H., Hao, J. M., and Liu, X.: Updated emission inventories for speciated atmospheric mercury from anthropogenic sources in China, Environ. Sci. Technol., 49, 3185–3194, 2015.

Zhang, Q., Jimenez, J. L., Canagaratna, M. R., Allan, J. D., Coe, H., Ulbrich, I., Alfarra, M. R., Takami, A., Middlebrook, A. M., Sun, Y. L., Dzepina, K., Dunlea, E., Docherty, K., DeCarlo, P. F., Salcedo, D., Onasch, T., Jayne, J. T., Miyoshi, T., Shimono, A., Hatakeyama, S., Takegawa, N., Kondo, Y., Schneider, J., Drewnick, F., Borrmann, S., Weimer, S., Demerjian, K., Williams, P., Bower, K., Bahreini, R., Cottrell, L., Griffin, R. J., Rautiainen, J., Sun, J. Y., Zhang, Y. M., and Worsnop, D. R.: Ubiquity and dominance of oxygenated species in organic aerosols in anthropogenically-influenced Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L13801, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL029979, 2007.

Zheng, W. and Hintelmann, H.: Mercury isotope fractionation during photoreduction in natural water is controlled by its Hg ∕ DOC ratio, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 73, 6704–6715, 2009.

Zheng, W. and Hintelmann, H.: Nuclear field shift effect in isotope fractionation of mercury during abiotic reduction in the absence of light, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 4238–4245, 2010a.

Zheng, W. and Hintelmann, H.: Isotope fractionation of mercury during its photochemical reduction by low-molecular-weight organic compounds, J. Phys. Chem. A, 114, 4246–4253, 2010b.