the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Secondary organic aerosol (SOA) yields from NO3 radical + isoprene based on nighttime aircraft power plant plume transects

Steven S. Brown

Ann M. Middlebrook

Peter M. Edwards

Pedro Campuzano-Jost

Douglas A. Day

José L. Jimenez

Hannah M. Allen

Thomas B. Ryerson

Ilana Pollack

Martin Graus

Carsten Warneke

Joost A. de Gouw

Charles A. Brock

Jessica Gilman

Brian M. Lerner

William P. Dubé

Jin Liao

André Welti

Nighttime reaction of nitrate radicals (NO3) with biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC) has been proposed as a potentially important but also highly uncertain source of secondary organic aerosol (SOA). The southeastern United States has both high BVOC and nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, resulting in a large model-predicted NO3-BVOC source of SOA. Coal-fired power plants in this region constitute substantial NOx emissions point sources into a nighttime atmosphere characterized by high regionally widespread concentrations of isoprene. In this paper, we exploit nighttime aircraft observations of these power plant plumes, in which NO3 radicals rapidly remove isoprene, to obtain field-based estimates of the secondary organic aerosol yield from NO3 + isoprene. Observed in-plume increases in nitrate aerosol are consistent with organic nitrate aerosol production from NO3 + isoprene, and these are used to determine molar SOA yields, for which the average over nine plumes is 9 % (±5 %). Corresponding mass yields depend on the assumed molecular formula for isoprene-NO3-SOA, but the average over nine plumes is 27 % (±14 %), on average larger than those previously measured in chamber studies (12 %–14 % mass yield as ΔOA ∕ ΔVOC after oxidation of both double bonds). Yields are larger for longer plume ages. This suggests that ambient aging processes lead more effectively to condensable material than typical chamber conditions allow. We discuss potential mechanistic explanations for this difference, including longer ambient peroxy radical lifetimes and heterogeneous reactions of NO3-isoprene gas phase products. More in-depth studies are needed to better understand the aerosol yield and oxidation mechanism of NO3 radical + isoprene, a coupled anthropogenic–biogenic source of SOA that may be regionally significant.

- Article

(5050 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(4049 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Organic aerosol (OA) is increasingly recognized as a globally important component of the fine particulate matter that exerts a large but uncertain negative radiative forcing on Earth's climate (Myhre et al., 2013) and adversely affects human health around the world (Lelieveld et al., 2015). This global importance is complicated by large regional differences in OA concentrations relative to other sources of aerosol such as black carbon, sulfate, nitrate and sea salt. OA comprises 20 %–50 % of total fine aerosol mass at continental mid-latitudes, but more in urban environments and biomass burning plumes, and up to 90 % over tropical forests (Kanakidou et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2007). Outside of urban centers and fresh biomass burning plumes, the majority of this OA is secondary organic aerosol (SOA) (Jimenez et al., 2009), produced by oxidation of directly emitted volatile organic compounds followed by partitioning into the aerosol phase. Forests are strong biogenic VOC emitters, in the form of isoprene (C5H8), monoterpenes (C10H16), and sesquiterpenes (C15H24), all of which are readily oxidized by the three major atmospheric oxidants, OH, NO3 and O3. The total global source of biogenic SOA from such reactions remains highly uncertain, with a view estimating it at 90±90 TgC yr−1 (Hallquist et al., 2009), a large fraction of which may be anthropogenically controlled (Spracklen et al., 2011; Goldstein et al., 2009; Carlton et al., 2010; Hoyle et al., 2011). As most NO3 arises from anthropogenic emissions, OA production from NO3 + isoprene is one mechanism that could allow for the anthropogenic control of biogenic SOA mass loading.

Isoprene constitutes nearly half of all global VOC emissions to the atmosphere, with a flux of ∼ 600 Tg yr−1 (Guenther et al., 2006). As a result, accurate global biogenic SOA budgets depend strongly on yields from isoprene oxidation. Recent global modeling efforts find that isoprene SOA is produced at rates from 14 (Henze and Seinfeld, 2006; Hoyle et al., 2007) to 19 TgC yr−1 (Heald et al., 2008), which implies that it could constitute 27 % (Hoyle et al., 2007), 48 % (Henze and Seinfeld, 2006) or up to 78 % (Heald et al., 2008) of total SOA (based also on varying estimates of total SOA burden in each study). More recent observational constraints on SOA yield from isoprene find complex temperature-dependent mechanisms that could affect vertical distributions (Worton et al., 2013) and suggest that isoprene SOA constitutes from 17 % (Hu et al., 2015) to 40 % (Kim et al., 2015) and up to 48 % (Marais et al., 2016) of total OA in the southeastern United States (SEUS). This large significance comes despite isoprene's low SOA mass yields, two recent observational studies estimated the total isoprene SOA mass yield to be ∼ 3 % (Marais et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2015), and modeling studies typically estimate isoprene SOA yields to be 4 % to 10 %, depending on the oxidant, in contrast to monoterpenes' yields of 10 % to 20 % and sesquiterpenes' yields of > 40 % (Pye et al., 2010). Furthermore, laboratory studies of SOA mass yields may have a tendency to underestimate these yields, if they cannot access the longer timescales of later-generation chemistry, or are otherwise run under conditions that limit oxidative aging of first-generation products (Carlton et al., 2009).

Laboratory chamber studies of SOA mass yield at OA loadings of ∼ 10 µg m−3 from isoprene have typically found low yields from O3 (1 % Kleindienst et al., 2007) and OH (2 % at low NOx to 5 % at high NOx Kroll et al., 2006; Dommen et al., 2009; 1.3 % at low NOx and neutral seed aerosol pH but rising to 29 % in the presence of acidic sulfate seed aerosol due to reactive uptake of epoxydiols of isoprene IEPOX Surratt et al., 2010). One recent chamber study on OH-initiated isoprene SOA formation focused on the fate of second-generation RO2 radical found significantly higher yields, up to 15 % at low NOx (Liu et al., 2016), suggesting that omitting later-generation oxidation chemistry could be an important limitation of early chamber determinations of isoprene SOA yields. Another found an increase in SOA formed with increasing HO2 to RO2 ratios, suggesting that RO2 fate could also play a role in the variability of previously reported SOA yields (D'Ambro et al., 2017).

For NO3 oxidation of isoprene, early chamber experiments already pointed to higher yields (e.g., 12 % Ng et al., 2008) than for OH oxidation. Ng et al. (2008) also observed chemical regime differences: SOA yields were approximately two times larger when chamber conditions were tuned such that first-generation peroxy radical fate was RO2+RO2 dominated than when it was RO2+NO3 dominated. In addition, Rollins et al. (2009) observed a significantly higher SOA yield (14 %) from second-generation NO3 oxidation than that when only one double bond was oxidized (0.7 %). This points to the possibility that later-generation, RO2+RO2 dominated isoprene + NO3 chemistry may be an even more substantial source of SOA than what current chamber studies have captured. Schwantes et al. (2015) investigated the gas-phase products of NO3 + isoprene in the RO2+HO2 dominated regime and found the major product to be isoprene nitrooxy hydroperoxide (INP, 75 %–78 % molar yield), which can photochemically convert to isoprene nitrooxy hydroxyepoxide (INHE), a molecule that might contribute to SOA formation via heterogeneous uptake similar to IEPOX. Here again, multiple generations of chemistry are required to produce products that may contribute to SOA.

As the SOA yield appears to be highest for NO3 radical oxidation, and isoprene is such an abundantly emitted BVOC, oxidation of isoprene by NO3 may be an important source of OA in areas with regional NOx pollution. As the SOA yield with neutral aerosol seed appears to be an order of magnitude larger than that from other oxidants, even if only 10 % of isoprene is oxidized by NO3, it will produce comparable SOA to daytime photo-oxidation. For example, Brown et al. (2009) concluded that NO3 contributed more SOA from isoprene than OH over New England, where > 20 % of isoprene emitted during the previous day was available at sunset to undergo dark oxidation by either NO3 or O3. The corresponding contribution to total SOA mass loading was 1 %–17 % based on laboratory yields (Ng et al., 2017). Rollins et al. (2012) concluded that multi-generational NO3 oxidation of biogenic precursors was responsible for one-third of nighttime organic aerosol increases during the CalNex-2010 experiment in Bakersfield, CA. In an aircraft study near Houston, TX, Brown et al. (2013) observed elevated organic aerosol in the nighttime boundary layer, and correlated vertical profiles of organic and nitrate aerosol in regions with rapid surface level NO3 radical production and BVOC emissions. From these observations, the authors estimated an SOA source from NO3 + BVOCs within the nocturnal boundary layer of 0.05–1 µg m−3 h−1. Carlton et al. (2009) note the large scatter in chamber-measured SOA yields from isoprene photooxidation and point throughout their review of SOA formation from isoprene to the likely importance of poorly understood later generations of chemistry in explaining field observations. We suggest that similar differences in multi-generational chemistry could explain the variation among the (sparse) chamber and field observations of NO3 + isoprene yields described in the previous paragraph, and summarized in a recent review of NO3 + BVOC oxidation mechanisms and SOA formation (Ng et al., 2017).

The initial products of NO3 + isoprene include organic nitrates, some of which will partially partition to the aerosol phase. Organic nitrates in the particle phase (pRONO2) are challenging to quantify with online methods, due to both interferences and their often overall low concentrations in ambient aerosol. Hence, field datasets to constrain modeled pRONO2 are sparse (Ng et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2016). One of the most used methods in recent studies, used also here, is quantification with the Aerodyne Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (AMS). Organic nitrates thermally decompose in the AMS vaporizer and different approaches have been used to apportion the organic fraction contributing to the total nitrate signal. Allan et al. (2004a) first proposed the use of nitrate peaks at m∕z 30 and 46 to distinguish various nitrate species with the AMS. Marcolli et al. (2006), in the first reported tentative assignment of aerosol organic nitrate using AMS data, used cluster analysis to analyze data from the 2002 New England Air Quality Study. In that study, cluster analysis identified two categories with high m∕z 30 contributions. One of these peaked in the morning when NOx was abundant and was more prevalent in plumes with the lowest photochemical ages, potentially from isoprene oxidation products. The second was observed throughout the diurnal cycle in both fresh and aged plumes, and contained substantial m∕z 44 contribution (highly oxidized OA). A subsequent AMS laboratory and field study discussed and further developed methods for separate quantification of organic nitrate (in contrast to inorganic nitrate) (Farmer et al., 2010). A refined version of one of these separation methods, based on the differing ∕ NO+ fragmentation ratio for organic vs. inorganic nitrate, was later employed to quantify organic nitrate aerosol at two forested rural field sites where strong biogenic VOC emissions and relatively low NOx combined to make substantial organic nitrate aerosol concentrations (Fry et al., 2013; Ayres et al., 2015). Most recently, Kiendler-Scharr et al. (2016) used a variant of this method to conclude that across Europe, organic nitrates comprise ∼ 40 % of submicron organic aerosol. Modeling analysis concluded that a substantial fraction of this organic nitrate aerosol is produced via NO3 radical initiated chemistry. Chamber studies have employed this fragmentation ratio method to quantify organic nitrates (Boyd et al., 2015; Bruns et al., 2010; Fry et al., 2009, 2011; Rollins et al., 2009), providing the beginnings of a database of typical organonitrate fragmentation ratios from various BVOC precursors.

Measurements conducted at the SOAS ground site in Centreville, Alabama in 2013 found evidence of significant organonitrate contribution to SOA mass loading. Xu et al. (2015) reported that organic nitrates constituted 5 % to 12 % of total organic aerosol mass from AMS data applying a variant of the ∕ NO+ ratio method. They identify a nighttime-peaking “LO-OOA” AMS factor, which they attribute to mostly NO3 oxidation of BVOC (in addition to O3 + BVOC). They estimated that the NO3 radical oxidizes 17 % of isoprene, 20 % of α-pinene, and 38 % of β-pinene in the nocturnal boundary layer at this site. However, applying laboratory-based SOA yields to model the predicted increase in OA, Xu et al. (2015) predict only 0.7 µg m−3 of SOA would be produced, substantially lower than the measured nighttime LO-OOA production of 1.7 µg m−3. The more recent analysis of Zhang et al. (2018) found a strong correlation of monoterpene SOA with the fraction of monoterpene oxidation attributed to NO3, even for non-nitrate containing aerosol, suggesting an influence of NO3 even in pathways that ultimately eliminate the nitrate functionality from the SOA, such as hydrolysis or NO2 regeneration. Ayres et al. (2015) used a correlation of overnight organonitrate aerosol buildup with calculated net NO3 + monoterpene and isoprene reactions to estimate an overall NO3 + monoterpene SOA mass yield of 40 %–80 %. The factor of two range in this analysis was based on two different measurements of aerosol-phase organic nitrates. These authors used similar correlations to identify specific CIMS-derived molecular formulae that are likely to be NO3 radical chemistry products of isoprene and monoterpenes, and found minimal contribution of identified first-generation NO3 + isoprene products to the aerosol phase (as expected based on their volatility). Lee et al. (2016) detected abundant highly functionalized particle-phase organic nitrates at the same site, with apparent origin both from isoprene and monoterpenes, and both daytime and nighttime oxidation, and estimated their average contribution to submicron organic aerosol mass to be between 3 %–8 %. For the same ground campaign, Romer et al. (2016) found evidence of rapid conversion from alkyl nitrates to HNO3, with total alkyl nitrates having an average daytime lifetime of 1.7 h.

Xie et al. (2013) used a model constrained by observed alkyl nitrate correlations with O3 from the INTEX-NA/ICARTT 2004 field campaign to determine a range of isoprene nitrate lifetimes between 4 and 6 h, with 40 %–50 % of isoprene nitrates formed by NO3 + isoprene reactions. Laboratory studies show that not all organic nitrates hydrolyze to HNO3 equally rapidly: primary and secondary organic nitrates were found to be less prone to aqueous hydrolysis than tertiary organic nitrates (Darer et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2016; Boyd et al., 2015). This suggests that field-based estimates of the contribution of organic nitrates to SOA formation could be a lower limit, if they are based on measurement of those aerosol-phase nitrates. This is because if hydrolysis is rapid, releasing HNO3 but leaving behind the organic fraction in the aerosol phase, then that organic mass would not be accurately accounted for as arising from nitrate chemistry. This was addressed in a recent modeling study of SOAS (Pye et al., 2015) in which modeled hydrolysis products of particulate organic nitrates of up to 0.8 µg m−3 additional aerosol mass loading in the southeastern U.S. were included in the estimate of change in OA due to changes in NOx. Another recent GEOS-Chem modeling study using gas- and particle-phase organic nitrates observed during the SEAC4RS and SOAS campaigns similarly found RONO2 to be a major sink of NOx across the SEUS region (Fisher et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016).

Complementing these SOAS ground site measurements, the NOAA-led SENEX (Southeast Nexus) aircraft campaign conducted 18 research flights focused in part on studying the interactions between biogenic and anthropogenic emissions that formed secondary pollutants between 3 June and 10 July 2013 (Warneke et al., 2016). Flight instrumentation focused on measurement of aerosol precursors and composition enable the present investigation of SOA yields using this aircraft data set. Edwards et al. (2017) used data from the SENEX night flights to evaluate the nighttime oxidation of BVOC, observing high nighttime isoprene mixing ratios in the residual layer that can undergo rapid NO3 oxidation when sufficient NOx is present. These authors suggest that past NOx reductions may have been uncoupled from OA trends due to NOx not having been the limiting chemical species for OA production, but that future reductions in NOx may decrease OA if NO3 oxidation of BVOC is a substantial regional SOA source. As isoprene is ubiquitous in the nighttime residual layer over the southeastern United States and the NO3 + isoprene reaction is rapid, NO3 reaction will be dominant relative to O3 in places with anthropogenic inputs of NOx (Edwards et al., 2017 conclude that when NO2 ∕ BVOC > 0.5, NO3 oxidation will be dominant). Hence, a modest NO3 + isoprene SOA yield may constitute a regionally important OA source.

Several modeling studies have investigated the effects of changing NOx on global and SEUS SOA. Hoyle et al. (2007) found an increase in global SOA production from 35 to 53 Tg yr−1 since preindustrial times, resulting in an increase in global annual mean SOA mass loading of 51 %, attributable in part to changing NOx emissions. Zheng et al. (2015) found only moderate SOA reductions from a 50 % reduction in NO emissions: 0.9 %–5.6 % for global NOx or 6.4 %–12.0 % for southeastern US NOx, which they attributed to buffering by alternate chemical pathways and offsetting tendencies in the biogenic vs. anthropogenic SOA components. In contrast, Pye et al. (2015) find a 9 % reduction in total organic aerosol in Centreville, AL for only 25 % reduction in NOx emissions. A simple limiting-reagent analysis of NO3 + monoterpene SOA from power plant plumes across the United States found that between 2008 and 2011, based on EPA-reported NOx emissions inventories, some American power plants shifted to the NOx-limited regime (from 3.5 % to 11 % of the power plants), and showed that these newly NOx-limited power plants were primarily in the southeastern United States (Fry et al., 2015). The effect of changing NOx on SOA burden is clearly still in need of further study.

Here, we present aircraft transects of spatially discrete NOx plumes from electric generating units (EGU), or power plants (PP), as a method to specifically isolate the influence of NO3 oxidation. These plumes are concentrated and highly enriched in NOx over a scale of only a few km (Brown et al., 2012), and have nitrate radical production rates (P(NO3)) 10–100 times greater than those of background air. The rapid shift in P(NO3) allows direct comparison of air masses with slow and rapid oxidation rates attributable to the nitrate radical, effectively isolating the influence of this single chemical pathway in producing SOA and other oxidation products. Changes in organic nitrate aerosol (pRONO2) concentration and accompanying isoprene titration enable a direct field determination of the SOA yield from NO3 + isoprene.

The Southeast Nexus (SENEX: http://esrl.noaa.gov/csd/projects/senex/, last access: 8 August 2018) campaign took place 3 June through 10 July 2013 as the NOAA WP-3D aircraft contribution to the larger Southeast Atmospheric Study (SAS: http://www.eol.ucar.edu/field_projects/sas/, last access: 8 August 2018), a large, coordinated research effort focused on understanding natural and anthropogenic emissions, oxidation chemistry and production of aerosol in the summertime atmosphere in the southeastern United States. The NOAA WP-3D aircraft operated 18 research flights out of Smyrna, Tennessee, carrying an instrument payload oriented towards elucidating emissions inventories and reactions of atmospheric trace gases, and aerosol composition and optical properties (Warneke et al., 2016). One of the major goals of the larger SAS study is to quantify the fraction of organic aerosol that is anthropogenically controlled, with a particular focus on understanding how OA may change in the future in response to changing anthropogenic emissions.

The subset of aircraft instrumentation employed for the present analysis of nighttime NO3 + isoprene initiated SOA production includes measurements used to determine NO3 radical production rate (P(NO3) = (T) [NO2] [O3]), isoprene and monoterpene concentrations, other trace gases for plume screening and identification, aerosol size distributions and aerosol composition. The details on the individual measurements and the overall aircraft deployment goals and strategy are described in Warneke et al. (2016). Briefly, NO2 was measured by UV photolysis and gas-phase chemiluminescence (P-CL) and by cavity ringdown spectroscopy, (CRDS), which agreed within 6 %. O3 was also measured by both gas-phase chemiluminescence and CRDS and agreed within 8 %, within the combined measurement uncertainties of the instruments. Various volatile organic compounds were measured with several techniques, including for the isoprene and monoterpenes of interest here, proton reaction transfer mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) and canister whole air samples and post-flight GC-MS analysis (iWAS/GCMS). A comparison of PTR-MS and iWAS/GCMS measurements of isoprene during SENEX has high scatter due to imperfect time alignment and isoprene's high variability in the boundary layer, but the slope of the intercomparison is 1.04 (Warneke et al., 2016); for more details on the VOC intercomparisons; see also Lerner et al. (2017). Acetonitrile from the PTRMS was used to screen for the influence of biomass burning. Sulfur dioxide (SO2) was used to identify emissions from coal-fired power plants. All gas-phase instruments used dedicated inlets, described in detail in the supplemental information for Warneke et al. (2016).

Aerosol particles were sampled downstream of a low turbulence inlet (Wilson et al., 2004), after which they were dried by ram heating, size-selected by an impactor with 1 µm aerodynamic diameter size cut-off, and measured by various aerosol instruments (Warneke et al., 2016). An ultra-high-sensitivity aerosol sizing spectrometer (UHSAS, Particle Metrics, Inc., Boulder, CO Brock et al., 2011; Cai et al., 2008) was used to measure the dry submicron aerosol size distribution down to about 70 nm. Data for the UHSAS are reported at 1 Hz whereas AMS data were recorded roughly every 10 s. The ambient (wet) surface areas were calculated according to the procedures described in Brock et al. (2016). A pressure-controlled inlet (Bahreini et al., 2008) was employed to ensure that a constant mass flow rate was sampled by a compact time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (C-ToF-AMS), which measured the non-refractory aerosol composition (Drewnick et al., 2005). The aerosol volume transmitted into the AMS was calculated by applying the measured AMS lens transmission curve (Bahreini et al., 2008) to the measured particle volume distributions from the UHSAS. For the entire SENEX study, the mean, calculated fraction of aerosol volume behind the 1 micron impactor that was transmitted through the lens into the AMS instrument was 97 % (with ±4 % standard deviation), indicating that most of the submicron aerosol volume measured by the sizing instruments was sampled by the AMS.

After applying calibrations and the composition-dependent collection efficiency following Middlebrook et al. (2012), the limits of detection for the flight analyzed here were 0.05 µg m−3 for nitrate, 0.26 µg m−3 for organic mass, 0.21 µg m−3 for ammonium, and 0.05 µg m−3 for sulfate, determined as three times the standard deviation of 10 s filtered air measurements obtained for 10 min during preflight and 10 min during postflight (110 datapoints). Note that the relative ionization efficiency for ammonium was 3.91 and 3.87 for the two bracketing calibrations and an average value of 3.9 was used for the flight analyzed here. An orthogonal distance regression (ODR-2) of the volume from composition data (AMS mass plus refractory black carbon) using a mass weighted density as described by Bahreini et al. (2009) vs. the volume based on the sizing instruments (after correcting for AMS lens transmission as above) had a slope of 1.06 for the entire SENEX study and 72 % of the data points were within the measurements' combined uncertainties of ±45 % (Bahreini et al., 2008). However, for the flight analyzed here, the same regression slope was 1.58, which is slightly higher than the combined uncertainties. It is unclear why the two types of volume measurements disagree more for this flight. This does not change the conclusions of this work because this has been incorporated into the error in aerosol organic nitrate, which still show positive enhancements in pRONO2 for these plumes (see Fig. 4 below). These complete error estimates are also used in Fig. 5 to clearly show the uncertainties in the yields. The volume comparison is discussed further in the Supplement and shown for the plumes of interest in Fig. S1.

The C-ToF-AMS is a unit mass resolution (UMR) instrument and the mass spectral signals that are characteristic of aerosol nitrate at m∕z30 and 46 (NO+ and ) often contain interferences from organic species such as CH2O+ and , respectively. Here, the m∕z 30 and 46 signals have been corrected for these interferences by using correlated organic signals at m∕z 29, 42, 43, and 45 that were derived from high-resolution AMS measurements during the NASA SEAC4RS campaign that took place in the same regions of the SE US shortly after SENEX (see and Fig. S2). The corrections were applied to the individual flight analyzed here from 2 July. All of the corrections were well correlated with each other for the SEAC4RS dataset and we used the organic peak at m∕z 29 (from CHO+) and the peak at m∕z 45 (from ), respectively, as those corrections were from peaks closest (in m∕z) to those being corrected. Once corrected, the nitrate mass concentrations in the final data archive for this flight were reduced by 0–0.24 µg sm−3, an average reduction of 0.11 µg sm−3 or 32 % from the initial nitrate mass concentrations. The organic interferences removed from the m∕z 30 and m∕z 46 signals are linearly correlated with the total organic mass concentrations, corresponding to an average 1.3 % increase in the total organic mass.

The ratio of the corrected ∕ NO+ signals was then used to calculate the fraction of aerosol nitrate that was organic (pRONO2) or inorganic (ammonium nitrate) based on the method described first in Fry et al. (2013). Here we used an organic ∕ NO+ ratio that was equal to the ammonium nitrate ∕ NO+ ratio from our calibrations divided by 2.8. This factor was determined from multiple datasets (see discussion in the Supplement). The ammonium nitrate ∕ NO+ ratio was obtained from the two calibrations on 30 June and 7 July that bracketed the flight on 2 July, which is analyzed here. It was 0.514 and 0.488, respectively, and for all of the data from both calibrations it averaged 0.490. Hence, the organic nitrate ∕ NO+ ratio was estimated to be 0.175. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that UMR measurements of aerosol nitrate have been corrected with HR correlations and used to apportion the corrected nitrate into inorganic or organic nitrate species.

The time since emission of intercepted power plant plumes was estimated from the slope of a plot of O3 against NO2. For nighttime emitted NOx plumes that consist primarily of NO (Peischl et al., 2010), O3 is negatively correlated with NO2 due to the rapid reaction of NO with O3 that produces NO2 in a 1 : 1 ratio:

Reaction (R1) goes rapidly (NO pseudo first order loss rate coefficient of 0.03 s−1 at 60 ppb O3) to completion, so that all NOx is present as NO2, as long as the plume NO does not exceed background O3 after initial mixing of the plume into background air. Subsequent oxidation of NO2 via Reaction (R2) leads to an increasingly negative slope of O3 vs. NO2:

Equation (1) then gives plume age subsequent to the completion of (R1) in terms of the observed slope, m, of O3 vs. NO2 (Brown et al., 2006).

Here S is a stoichiometric factor that is chosen for this analysis to be 1 based on agreement of plume age with elapsed time in a box model run initialized with SENEX flight conditions (see below); k1 is the temperature dependent bimolecular rate constant for NO2+O3 (Reaction R2) and is the average O3 within the plume.

We calculate plume ages using both a stoichiometric factor of 1 (loss of NO3 and N2O5 dominated by NO3 reactions) and 2 (loss dominated by N2O5 reactions), although we note that the chemical regime for NO3+N2O5 loss may change over the lifetime of the plume, progressing from 1 to 2 as the BVOC is consumed. We use S=1 values in the analysis that follows. As the more aged plumes are more likely to have S approach 2, this means that some of the older plumes may have overestimated ages. Figure S3 shows the plume age calculated by Eq. (1) using modeled NOx, NOy and O3 concentrations for S=1 and S=2, from nighttime simulations of plume evolution using an observationally constrained box model. This confirms that for nighttime plumes, S=1 plume ages match modeled elapsed time well. The model used for this calculation, and those used to assess peroxy radical lifetimes and fates in Sect. 4.3, was the Dynamically Simple Model of Atmospheric Chemical Complexity (DSMACC Emmerson and Evans, 2009) containing the Master Chemical Mechanism v3.3.1 chemistry scheme (Jenkin et al., 2015). More details on the model approach are provided in the Supplement.

There were three nighttime flights (takeoffs on the evenings of 19 June, 2 and 3 July 2013, Central Daylight Time) conducted during SENEX, of which one (2 July) surveyed regions surrounding Birmingham, Alabama, including multiple urban and power plant plume transects. As described in the introduction, these plume transects are the focus of the current analysis as they correspond to injections of concentrated NO (and subsequently high P(NO3)) into the regionally widespread residual layer isoprene. The nighttime flight on 3 July, over Missouri, Tennessee and Arkansas sampled air more heavily influenced by biomass burning than biogenic emissions. The 19 June night flight sampled earlier in the evening, in the few hours immediately after sunset, and sampled more diffuse urban plume transects that had less contrast with background air. Therefore, this paper uses data exclusively from the 2 July flight, in which nine transects of well-defined NOx plumes from power plants emitted during darkness can be analyzed to obtain independent yields measurements.

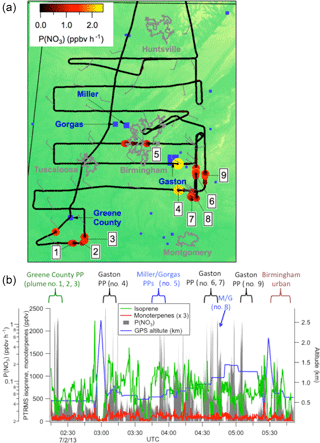

A map of the 2 July flight track is shown in Fig. 1a. After takeoff at 8:08 pm local Central Daylight Time on 2 July, 2013 (01:08 a.m. UTC 3 July 2016), the flight proceeded towards the southwest until due west of Montgomery, AL, after which it conducted a series of east-west running tracks while working successively north toward Birmingham, AL. Toward the east of Birmingham, the aircraft executed overlapping north-south tracks at six elevations to sample the E. C. Gaston power plant. During the course of the flight, concentrated NOx plumes from the Gaston, Gorgas, Miller and Greene City power plants were sampled. Around 01:30 and 02:30 a.m. Central Daylight Time (05:30 and 06:30 a.m. UTC), two transects of the Birmingham, AL urban plume were measured prior to returning to the Smyrna, TN airport base.

The flight track is shown colored by the nitrate radical production rate,P(NO3), to show the points of urban and/or power plant plume influence:

Here, k2 is again the temperature-dependent rate coefficient for reaction of NO2+O3 (Atkinson et al., 2004), and the square brackets indicate concentrations. Figure 1b further illustrates the selection of power plants plumes: sharp peaks in P(NO3) are indicative of power plant plume transects, during which isoprene mixing ratios also are observed to drop from the typical regional residual layer background values of ∼1 ppb, indicative of loss by NO3 oxidation (an individual transect is shown in more detail below in Fig. 2). Also shown in Fig. 1b are measured concentrations of isoprene and monoterpenes throughout the flight, showing substantial residual layer isoprene and supporting the assumption that effectively all NO3 reactivity is via isoprene (see calculation in next section). Residual layer concentrations of other VOCs that could produce SOA (e.g., aromatics) are always below 100 pptv, and their reaction rates with NO3 are slow. Edwards et al. (2017) have shown that NO3 and isoprene mixing ratios for this and other SENEX night flights exhibit a strong and characteristic anticorrelation that is consistent with nighttime residual layer oxidation chemistry.

Figure 1(a) Map of northern Alabama, showing the location of the flight track of the 2 July 2013 night flight used in the present analysis, with plume numbers labeled and wind direction shown. Although the wind direction changed throughout the night, these measurements enable us to attribute each plume to a power plant source (see labels in Fig. 1b and Table 2). Color scale shows P(NO3) based on aircraft-measured [NO2] and [O3], while power plants discussed in the text are indicated in blue squares with marker size scaled to annual NOx emissions for 2013 (scale not shown). Isoprene emissions are widespread in the region (Edwards et al., 2017). Panel (b) shows time series data from the same flight, with plume origins and numbers labeled, showing aircraft-measured isoprene and monoterpene concentrations, altitude, and P(NO3) determined according to Eq. (2) (log scale), showing that the isoprene was uniformly distributed (mixing ratios often in excess of 1 ppbv), while the more reactive monoterpenes were present at mixing ratios below 100 ppt except at the lowest few hundred meters above ground in the vertical profiles (not used in the present analysis). Figure 1b also shows that sharp peaks in nitrate radical production rate occur both at the lowest points of these vertical profiles, when the aircraft approached the surface, but also frequently during periods of level flight in the residual layer, which correspond to the power plant plume transects analyzed in this paper.

4.1 Selection of plumes

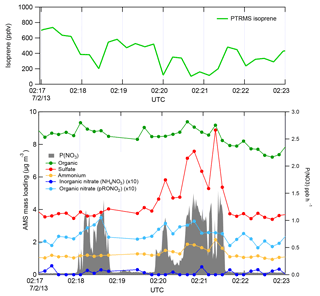

Figure 2 shows a subset of the 2 July flight time series data, illustrating three NOx plumes used for analysis. The large NO3 source and isoprene loss was accompanied by an increase in organic nitrate aerosol mass, which we attribute to the NO3 + isoprene reaction based on prior arguments. We observed each plume as a rapid and brief perturbation to background conditions, in the order of 10–50 s, or 1–5 km in spatial scale. Each plume's perturbed conditions can correspond to different plume ages, depending on how far downwind of the power plant the plume transect occurred.

Figure 2Three representative plume transect observations from the 2 July 2013 flight (plumes are identified by the peaks in P(NO3), listed in Table 1 at times 02:18, 02:20, and 02:21 UTC). Note the difference in sulfate enhancement in the three plumes, which is largest in the third plume, and is accompanied by increases in ammonium. In all three cases, the isoprene concentration drops in the plumes, accompanied by a clear increase in organic nitrate, no changes in the inorganic nitrate, and modest changes in organic aerosol mass concentrations.

Candidate plumes were initially identified by scanning the time series flight data for any period where the production rate of nitrate radical (P(NO3)) rose above 0.5 ppbv h−1. This threshold was chosen to be above background noise and large enough to isolate only true plumes (see Fig. 1a). The value is thus subjectively chosen, but was consistently applied across the dataset. For each such period, a first screening removed any of these candidate plumes that occurred during missed approaches or other periods where radar altitude above ground level (a.g.l.) was changing, because in the stratified nighttime boundary layer structure, variations in altitude may result in sampling different air-masses, rendering the adjacent out of plume background not necessarily comparable to in-plume conditions. A second criterion for rejection of a plume was missing isoprene or AMS data during brief plume intercepts. No selected plumes on 2 July showed enhanced acetonitrile or refractory black carbon, indicating no significant biomass burning influence. Finally, two plumes downwind of the Gaston power plant (at 03:10 and 03:14) were removed from the present analysis, because (03:10) the background isoprene was changing rapidly, preventing a good baseline measurement, and (03:14) there was no observed decrease in isoprene concentration in-plume (as well as no increase in nitrate aerosol). The 03:14 plume was apparently too recently emitted to have undergone significant nighttime reaction; its O3 ∕ NO2 slope was unity, within the combined measurement error of O3 and NO2 (Eq. 1). After this filtering, there are 9 individual plume observations for determination of NO3 + isoprene SOA yields (see Table 1). The rapid increases in P(NO3) appeared simultaneously with significant decreases in isoprene and increases in aerosol nitrate. The aerosol and isoprene measurements (taken at data acquisition rates < 1 Hz) were not exactly coincident in time, which leads to some uncertainty in the yield analysis below.

Derivation of SOA yields from observed changes in isoprene and aerosol mass in plumes depends on two conditions, and has several caveats that will be discussed in the text that follows (see Table 3 below for a summary of these caveats). The two conditions are (1) that the majority of VOC mass consumed by NO3 in plumes is isoprene (rather than monoterpenes or other VOC), and then that (2a) the change in aerosol organic mass concentration during these plumes is due to NO3 + isoprene reactions, and/or (2b) the change in aerosol nitrate mass concentration is due to NO3 + isoprene reactions. There are separate considerations for each of these conditions.

For the first condition, we note that the isoprene to monoterpenes ratio just outside each plume transect was always high (a factor of 10 to 70, on average 26). With the 298 K NO3 rate constants of cm3 molec−1 s−1 for monoterpenes and cm3 molec−1 s−1 for isoprene (Calvert et al., 2000), isoprene (∼2 ppb) will always react faster with nitrate than monoterpenes (∼0.04 ppbv). At these relative concentrations, even if all of the monoterpene is oxidized, the production rate of oxidation products will be much larger for isoprene. Contribution to aerosol by N2O5 uptake is also not important in these plumes. Edwards et al. (2017) calculated the sum of NO3 and N2O5 loss throughout this flight and showed that it is consistently NO3 + BVOC dominated (Fig. S4 of that paper). As isoprene depletes, N2O5 uptake will increasingly contribute to NO3 loss, but as shown below, we are able to rule out a substantial source of inorganic nitrate for most plumes. We also know that despite increased OH production in-plume, the isoprene loss is still overwhelming dominated by NO3 (Fig. S5 in Edwards, et al., 2017).

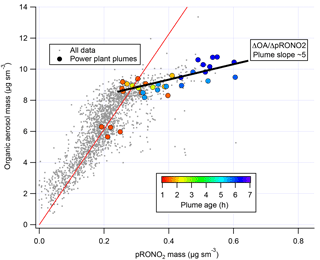

The second condition requires that we can find an aerosol signal that is attributable exclusively to NO3 + isoprene reaction products, whether it be organic aerosol (OA) or organic nitrate aerosol (pRONO2) mass loading, or both. We note that the ratio of in-plume aerosol organic mass increase to pRONO2 mass increase is noisy (see discussion below at Fig. 6), but indicates an average in-plume ΔOA to ΔpRONO2 ratio of about 5. The large variability is primarily due to the fact that the variability in organic aerosol mass between successive 10 s data points for the entire flight is quite large (of order 0.75 µg m−3) and comparable to many of the individual plume ΔOA increases, far exceeding the expected organonitrate driven increases in OA, which are roughly twice the pRONO2 mass increases. It is also possible that in these plumes, where total aerosol mass is elevated, semivolatile organic compounds may repartition to the aerosol phase, contributing a non-pRONO2 driven variability in ΔOA. For example, if some gas phase IEPOX is present in the residual layer, it may be taken up into the highly acidic aerosol from the power plants. Alternatively, very polar gas-phase compounds could partition further into the higher liquid water associated with the sulfate in the plume. Therefore, in-plume organic aerosol increases cannot be attributed clearly to NO3 + isoprene SOA production, so we do not use them in the SOA yield calculations.

This leaves consideration 2b, whether all increase in nitrate mass is due to NO3 + isoprene reactions. Here we must evaluate the possibility of inorganic nitrate aerosol production in these high-NOx plumes. Fine-mode aerosol inorganic nitrate can be formed by the (reversible) dissolution of HNO3(g) into aqueous aerosol. In dry aerosol samples, inorganic nitrate is typically in the form of ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3), when excess ammonium is available after neutralization of sulfate as (NH4)2SO4 and NH4(HSO4). Due to the greater stability of ammonium sulfate salt relative to ammonium nitrate, in high-sulfate plumes with limited ammonium, inorganic nitrate aerosol will typically evaporate as HNO3(g) (Guo et al., 2015) (Reaction R3):

Inorganic nitrate can also form when crustal dust (e.g., CaCO3) or sea salt (NaCl) are available. Uptake of HNO3 is rendered favorable by the higher stability of nitrate mineral salts, evaporating CO2 or HCl. Inorganic nitrate can also be produced by the heterogeneous uptake of N2O5 onto aqueous aerosol; Edwards et al. (2017) demonstrated that this process is negligible relative to NO3 + BVOC for the 2 July SENEX night flight considered here.

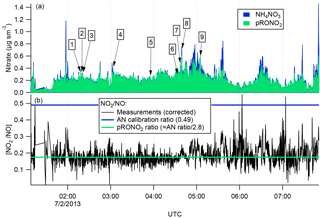

There are several lines of evidence that the observed nitrate aerosol is organic and not inorganic. First, examination of the ∕ NO+ (interference-corrected m∕z 46 : m∕z 30) ratio measured by the aircraft AMS (Fig. 3) shows a ratio throughout the 2 July flight, including the selected plumes, that is substantially lower than that from the bracketing ammonium nitrate calibrations. This lower AMS measured ∕ NO+ ratio has been observed for organic nitrates (Farmer et al., 2010), and some mineral nitrates (e.g., Ca(NO3)2 and NaNO3; Hayes et al., 2013 ), which are not important in this case because aerosol was dominantly submicron. As described above, we can separate the observed AMS nitrate signal into pRONO2 and inorganic nitrate contributions. These mass loadings are also shown in Fig. 3, indicating dominance of pRONO2 throughout the flight.

Figure 3For the flight under consideration, the estimated relative contributions of ammonium and organic nitrate to the total corrected nitrate signal (a) was calculated from the ratios of the corrected peaks at m∕z 30 and 46 (b). Each of the plumes is identified here by plume number. The ratios of ∕ NO+ (black data in b) from the corrected peaks at m∕z 46 and 30, respectively, are compared to the ratios expected for ammonium nitrate (AN Calibration Ratio, blue horizontal line at 0.49) or organic nitrate (pRONO2 Ratio, green horizontal line at 0.175), which is estimated from the AN calibration ratio using multiple data sets (see discussion in the Supplement). The measured ratio for most of the flight is more characteristic of organic nitrate than ammonium nitrate.

We can also employ the comparison of other AMS-measured aerosol components during the individual plumes to assess the possibility of an inorganic nitrate contribution to total measured nitrate. Figure S5a shows that the in-plume increases in sulfate are correlated with increases in ammonium with an R2 of 0.4. The observed slope of 5.4 is characteristic of primarily (NH4)HSO4, which indicates that the sulfate mass is not fully neutralized by ammonium. However, we note that if the largest observed aerosol nitrate increase is due solely to ammonium nitrate, the ammonium increase would be only 0.11 µg m−3, which would be difficult to discern from the NH4 variability of order 0.11 µg m−3. However, the slope is consistent with incomplete neutralization of the sulfate by ammonium, which would make HNO3(g) the more thermodynamically favorable form of inorganic nitrate. The ion balance for the ammonium nitrate calibration particles and the plume enhancements are shown in Fig. S5b. Complete neutralization of the calibration aerosols is nearly always within the gray 10 % uncertainty band for the relative ionization efficiency of ammonium (Bahreini et al., 2009). In contrast, many of the plume enhancements are near the 1 : 2 line (as primarily ammonium bisulfate) within the combined 10 % ammonium and 15 % sulfate uncertainty error bars or without ammonium (sulfuric acid). Thus, NH4NO3 is unlikely to be stable in the aerosol phase under the conditions of these plumes, consistent with the AMS observations.

A plot of the calculated plume enhancements from the derived apportionment into organic (pRONO2) and inorganic (ammonium) nitrate is shown in Fig. 4. The increases in aerosol nitrate for nearly all of the plumes appear to be mostly due to enhancements in pRONO2. Based on these considerations, we conclude that in-plume pRONO2 mass increases are a consequence (and thus a robust measure) of organic nitrate aerosol produced from NO3 + isoprene. As each isoprene molecule condensing will have one nitrate group, the ratio of these increases to isoprene loss is a direct measure of the molar organic aerosol yield from NO3-isoprene oxidation.

Figure 4The contribution of each species to the nitrate enhancements in each of the plumes, showing that the enhancements in most of the plumes are mainly due to enhancements in organic nitrate, with the exception of Plume 8, which had enhancements in both organic and ammonium nitrate. Error bars are estimated from the measurement variability, the UMR corrections to the nitrate signals, apportionment between organic and inorganic nitrate, and the total nitrate uncertainty (see Supplement).

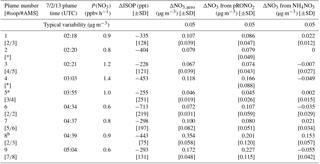

Table 1 shows the selected plumes to be used for yield analysis. Wherever possible, multiple points have been averaged for in-plume and background isoprene and nitrate aerosol concentrations; in each case the number of points used is indicated and the corresponding standard deviations are reported. In two cases (02:20 and 03:03 plumes), the plumes were so narrow that only a single point was measured in-plume at the 10 s time resolution of the PTR-MS and AMS; for these “single-point” plumes it is not possible to calculate error bars. Error bars were determined using the standard deviations calculated for in-plume and background isoprene and nitrate aerosol concentrations, accounting also for the additional uncertainty in the AMS measurement described in the caption to Fig. 4, and propagated through the yield formula detailed in the following section.

Table 1List of plumes used in this NO3 + isoprene SOA yield analysis. For each plume, the delta values listed indicate the difference between in-plume and outside-plume background in average observed concentration, and the standard deviations (SD) are the propagated error from this subtraction. (For ΔNO3 from pRONO2, the standard deviations also include error propagated as described in the caption for Fig. 4) After each plume number, the numbers of points averaged for isoprene (10 s resolution) and AMS (10 s resolution) are listed, respectively. As the isoprene data were reported at a lower frequency, these numbers are typically lower to cover the same period of time. Plume numbers annotated with * indicate brief plumes for which only single-point measurements of in-plume aerosol composition were possible. Additional AMS and auxiliary data from each plume is included in the Supplement, Table S3.

a Plume 5 has the smallest ΔNO3,aero and may be affected by background pRONO2 variability. b Plume 8 has a measurable increase in inorganic nitrate as well as organic.

4.2 SOA yield analysis

A molar SOA yield refers to the number of molecules of aerosol organic nitrate produced per molecule of isoprene consumed. In order to determine molar SOA yields from the data presented in Table 1, we convert the aerosol organic nitrate mass loading differences to mixing ratio differences (ppt) using the NO3 molecular weight of 62 g mol−1 (the AMS organic nitrate mass is the mass only of the −ONO2 portion of the organonitrate aerosol). At standard conditions of 273 K and 1 atm (all aerosol data are reported with this STP definition), 1000 ppt NO3 = 2.77 µg m−3, so each is multiplied by 361 ppt (µg m−3)−1 to determine this molar yield:

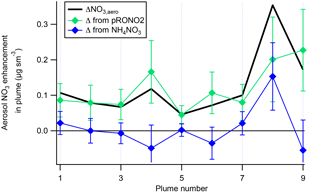

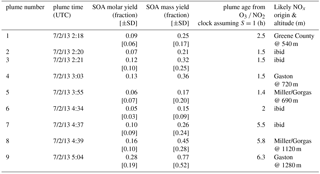

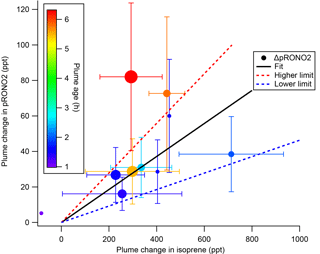

The SOA molar yields resulting from this calculation are shown in Table 2, spanning a range of 5 %–28 %, with uncertainties indicated based on the SDs in measured AMS and isoprene concentrations. In addition to this uncertainty based on measurement precision and ambient variability, there is an uncertainty of 50 % in the AMS derived-organic nitrate mass loadings (see Supplement) and 25 % in the PTR-MS isoprene concentrations (Warneke et al., 2016). The average molar pRONO2 yield across all plumes, with each point weighed by the inverse of its standard deviation, is 9 %. (As noted below, the yield appears to increase with plume age, so this average obscures that trend.) An alternate graphical analysis of molar SOA yield from all nine plumes plus one “null” plume (03:14, in which no isoprene had yet reacted and is thus not included in Tables 1 and 2) obtains the same average molar yield of 9 % (Fig. 5). Here, the molar yield is the slope of a plot of plume change in pRONO2 vs. plume change in isoprene. The slope is determined by a linear fit with points weighted by the square root of the number of AMS data points used to determine in-plume pRONO2 in each case. This slope error gives a rather narrow uncertainty range for the slope (0.0930±0.0011); to obtain an upper limit in the uncertainty of this molar yield we apply the combined instrumental uncertainties, based on adding in quadrature the PTR-MS uncertainty of 5 % and the AMS uncertainty of 50 %. This gives an overall uncertainty of 50.2 %, resulting in upper and lower limit slopes of 0.140 and 0.046, respectively; we use this maximum uncertainty estimate to report the average molar yield as 9 % (±5 %). We have not corrected the calculated yields for the possibility of NO3 heterogeneous uptake, which could add a nitrate functionality to existing aerosol. Such a process could be rapid if the uptake coefficient for NO3 were 0.1, a value characteristics of unsaturated substrates (Ng et al., 2017), but would not contribute measurably at more conventional NO3 uptake coefficients of 0.001 (Brown and Stutz, 2012).

Table 2SOA Yields for each plume observation, estimated plume age, and likely origin. See text for description of uncertainty estimates. For the mass yields, the calculated SOA mass increase includes both the organic and (organo)nitrate aerosol mass; the measurements for OA increases shown in Fig. 6 do not include the nitrate mass.

Figure 5SOA molar yield can be determined as the slope of ΔpRONO2 vs. Δ isoprene, both in mixing ratio units. The linear fit is weighted by square root of number of points used to determine each in-plume pRONO2, with intercept held at zero. The slope coefficient ± one standard deviation is 0.0930±0.0011. Larger “outside” high and low limits of the slope (shown as dashed red and blue lines) are obtained by adding and subtracting from this slope the combined instrumental uncertainties, based on adding in quadrature the PTR-MS uncertainty of 5 % and the AMS uncertainty of 50 %. This gives an overall uncertainty of 50.2 %, resulting in upper and lower limit slopes of 0.140 and 0.046, respectively. Points are colored by plume age, and size scaled by square root of number of points (the point weight used in linear fit). This plot and fit includes the nine plumes listed in Tables 1 and 2, as well as the 03:14 “unreacted” plume (at Δ isoprene = −84 ppt). Error bars on isoprene are the propagated standard deviations of the (in plume–out plume) differences, for plumes in which multi-point averages were possible. Error bars on pRONO2 are the same as in Fig. 4, converted to ppt. The points without error bars are single-point plumes.

To estimate SOA mass yields, we need to make some assumption about the mass of the organic molecules containing the nitrate groups that lead to the observed nitrate aerosol mass increase. The observed changes in organic aerosol are too variable to be simply interpreted as the organic portion of the aerosol organic nitrate molecules. We conservatively assume the organic mass to be approximately double the nitrate mass (62 g mol−1), based on an “average” molecular structure of an isoprene nitrate with three additional oxygens: e.g., a tri-hydroxynitrate (with organic portion of formula C5H11O3, 119 g mol−1), consistent with 2nd-generation oxidation product structures suggested in Schwantes et al. (2015). Based on this assumed organic to nitrate ratio, all plumes' expected organic mass increases would be less than the typical variability in organic of 0.75 µg m−3. This assumed structure is consistent with oxidation of both double bonds, which appears to be necessary for substantial condensation of isoprene products, and which structures would have calculated vapor pressures sufficiently low to partition to the aerosol phase (Rollins et al., 2009). Another possible route to low vapor pressure products is intramolecular H rearrangement reactions, discussed below in Sect. 4.3, which would not require oxidant reactions at both double bonds. In the case of oxidant reactions at both double bonds, it is difficult to understand how the second double bond would be oxidized unless by another nitrate radical, which would halve these assumed organic to nitrate ratios (assuming the nitrate is retained in the molecules). In contrast, any organic nitrate aerosol may lose NO3 moieties, increasing the organic to nitrate ratio. Given these uncertainties in both directions, we use the assumed “average” structure above to guess an associated organic mass of double the nitrate mass. Thus, to estimate SOA mass yield, we multiply the increase in organic nitrate aerosol mass concentration by three (i.e., ), and divide by the observed decrease in isoprene, converted to µg m−3 by multiplying by 329 ppt (µg m, the conversion factor based on isoprene's molecular weight of 68.12 g mol−1.

Note that the SOA mass yield reported here is based on the (assumed) mass of organic aerosol plus the (organo)nitrate aerosol formed in each plume. If instead the yield were calculated using only the assumed increase in organic mass (i.e., instead of , which would be consistent with the method used in Rollins, et al. (2009) and Brown et al. (2009), the mass yields would be two-thirds of the values reported here. However, as SOA mass yield is typically defined based on the total increase in aerosol mass, we use the definition with the sum of the organic and nitrate mass here. This results in an average SOA mass yield of 27 %, with propagated instrumental errors (see caption to Fig. 5) giving a range of 27 %±14 %.

We note also that correlation of in-plume increases in OA with pRONO2 (Fig. 6) point to a substantially larger 5 : 1 organic-to-nitrate ratio; if this were interpreted as indicating that the average molecular formula of the condensing organic nitrate has 5 times the organic mass as nitrate, this would increase the SOA mass yields reported here. However, due to the aforementioned possibility of additional sources of co-condensing organic aerosol, which led us to avoid using ΔOA in determining SOA yields, we do not consider this to be a direct indication of the molecular formula of the condensing organic nitrate. Including OA in the SOA yield determination, based on this 5 : 1 slope rather than the assumed 2 : 1 OA : pRONO2, would give 2.5 times larger SOA mass yields than reported here.

Figure 6Correlation of organic aerosol mass concentration with pRONO2 mass concentration for the full 2 July flight (grey points and red fit line, fitted slope and thus average OA ∕ pRONO2 mass ratio of ∼30) and for the points during the selected plumes (colored points, colored by plume age, average OA ∕ pRONO2 mass ratio of ∼5).

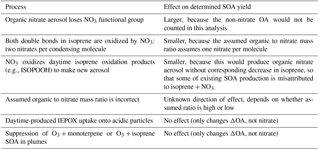

Table 3Several caveats to the present SOA yields analysis are listed below, alongside the expected direction each would adjust the estimated yields. As we do not know whether or how much each process may have occurred in the studied plumes, we cannot quantitatively assess the resulting uncertainties, so we simply list them here. See text above for more detailed discussion.

Finally, the large range in observed yields can be interpreted by examining the relationship to estimated plume age. Using the slope of O3 to NO2 (Eq. 1) to estimate plume age as described above, a weak positive correlation is observed (Table 2, Fig. S4), suggesting that as the plume ages, later-generation chemistry results in greater partitioning to the condensed phase of NO3 + isoprene organonitrate aerosol products. This is consistent with the observation by Rollins et al. (2009) that second-generation oxidation produced substantially higher SOA yields than the oxidation of the first double bond alone, but we note that these mass yields (averaging 27 %, would be 18 % using the organic mass only) are higher than even the largest yield found in that chamber study (14 %, used organic mass only).

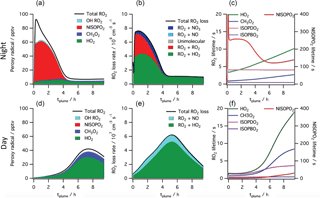

Figure 7Simulated peroxy radical concentration (a, d), loss rates (b, e), and lifetime (c, f), using the MCM v3.3.1 chemical mechanism, for conditions typical of a nighttime intercepted power plant plume (a–c) and the same plume initial conditions run for daytime simulation (d–f, local noon occurs at 5 h). Included are total peroxy radical concentration and losses, as well as the highlighted subclasses HO2, CH3O2, total nitrooxy-isoprene-RO2 and the total hydroxy-isoprene-RO2 produced from OH oxidation. The righthand panels show HO2, CH3O2 and the dominant hydroxy-isoprene-RO2 ISOPBO2 and ISOPDO2 (β-hydroxy-peroxy radicals from OH attack at carbons 1 and 4, respectively) lifetime on the left axis and nitrooxy-isoprene-RO2 on the right axis, showing nighttime lifetimes an order of magnitude longer than daytime for this NO3 + isoprene derived RO2 radical (NISOPO2).

We observe increasing SOA yield, from a molar yield of around 10 % at 1.5 h up to 30 % at 6 h of aging. The lowest yields observed are found in the most recently emitted plumes, suggesting the interpretation of the higher yields as a consequence of longer aging timescales in the atmosphere.

4.3 Mechanistic considerations

These larger SOA mass yields from field determinations (average 27 %) relative to chamber work (12 %–14 %; see introduction) may arise for several reasons. We first assess the volatility of assumed first- and second-generation products using group contribution theory in order to predict partitioning. After a single oxidation step, with a representative product assumed to be a C5 hydroperoxynitrate, the saturation vapor pressure estimated by group contribution theory (Pankow and Asher, 2008) at 283 K would be Torr (saturation mass concentration µg m−3 for MW = 147 g mol−1), while a double-oxidized isoprene molecule (assuming a C5 dihydroxy dinitrate) has an estimated vapor pressure of Torr ( µg m−3 for MW = 226 g mol−1). This supports the conclusion that while the first oxidation step produces compounds too volatile to contribute appreciably to aerosol formation, oxidizing both double bonds of the isoprene molecule is sufficient to produce substantial partitioning, consistent with Rollins et al. (2009). This is also true if the second double bond is not oxidized by nitrate (group contribution estimate Pvap for a C5 tri-hydroxy nitrate is Torr, µg m−3 for MW = 181 g mol−1). These C* saturation concentration values suggest that no dimer formation or oligomerization is required to produce low-enough volatility products to condense to the aerosol phase; however, such oligomerization would result in more efficient condensation. The fact that Rollins et al. (Rollins et al., 2009) did not observe larger mass yields may indicate that it takes longer than a typical chamber experiment timescale to reach equilibrium, or that this absorptive partitioning model did not accurately capture those experiments, or that substantial loss of semivolatiles to the chamber walls (e.g., Krechmer et al., 2016) suppressed apparent yields.

Determination of yields from ambient atmospheric data differs from chamber determinations in several additional respects. First, ambient measurements do not suffer from wall loss effects, such that no corrections are necessary for loss of aerosol or semi-volatile gases (Matsunaga and Ziemann, 2010; Krechmer et al., 2016). Second, ambient measurements take place on the aging time scale of the atmosphere rather than a time scale imposed by the characteristics of the chamber or the choice of oxidant addition. Third, the typical lifetime of the initially produced nitrooxy-isoprene-RO2 radical is more representative of the ambient atmosphere rather than a chamber. The unique conditions of a high NOx power plant plume affect lifetime and fates of peroxy radicals, as described below.

To help interpret these in-plume peroxy radical lifetimes, a box model calculation using the MCM v3.3.1 chemistry scheme was run (see details in the Supplement). This box model shows substantially longer peroxy radical lifetimes during nighttime than daytime, initializing with identical plume-observed conditions. These long peroxy radical lifetimes may have consequences for comparison to chamber experiments: for example, in Schwantes et al.'s (2015) chamber experiment on the NO3 + isoprene reaction mechanism, the HO2-limited nitrooxy-RO2 lifetime was at maximum 30 s. In the plumes investigated in this study, peroxy radical lifetimes are predicted to be substantially longer (> 200 s early in the night; see Fig. 7), allowing for the possibility of different bimolecular fates, or of unimolecular transformations of the peroxy radicals that may result in lower-volatility products (e.g., auto-oxidation to form highly oxidized molecules Ehn et al., 2014).

The typically assumed major fate of nighttime RO2 in the atmosphere is reaction with HO2 to yield a hydroperoxide, NO3-ROOH. This is shown in the model output above as the green reaction, and is responsible for half of early RO2 losses in the MCM modeled plume. Schwantes et al. (2015) proposed reaction of these nighttime derived hydroperoxides with OH during the following day as a route to epoxides, which in turn can form SOA via reaction with acidic aerosol. Reaction of hydroperoxides with nighttime generated OH may similarly provide a route to SOA through epoxides, albeit more slowly than that due to photochemically generated OH.

The predicted longer nighttime peroxy radical lifetimes may enable unique chemistry. For example, if nitrooxy-isoprene-RO2 self-reactions are substantially faster than assumed in the MCM, as suggested by Schwantes et al. (2015), RO2+RO2 reactions may compete with the HO2 reaction even more than shown in Fig. 7, and dimer formation may be favored at night, yielding lower volatility products. The 5 : 1 AMS organic to nitrate ratio observed in the SOA formed in Rollins et al. (2009), and consistent with aggregated observations reported here, may suggest that in some isoprene units the nitrate is rereleased as NO2 in such oligomerization reactions. We note that this larger organic to nitrate ratio would mean higher SOA mass yields than estimated in Table 2.

Alternatively, longer nighttime peroxy radical lifetimes may allow sufficient time for intramolecular reactions to produce condensable products. This unimolecular isomerization (auto-oxidation) of initially formed peroxy radicals is a potentially efficient route to low-volatility, highly functionalized products that could result in high aerosol yields. For OH-initiated oxidation of isoprene, laboratory relative rate experiments found the fastest 1,6-H-shift isomerization reaction to occur for the hydroxy-isoprene-RO2 radical at a rate of 0.002 s−1 (Crounse et al., 2011), meaning that peroxy radicals must have an ambient lifetime of > 500 s for this process to be dominant. As shown in Fig. 7, the simulated power plant plume peroxy radical lifetimes are long (> 200 s), so an isomerization reaction at this rate may play a significant role. However, a recent study has demonstrated that OH-initiated and NO3-initiated RO2 radicals from the same precursor VOC can have very different unimolecular reactive fates due to highly structurally sensitive varying rates of reactions of different product channels (Kurtén et al., 2017). A similar theoretical study on the rate of unimolecular autooxidation reactions of nitrooxy-isoprene-RO2 radicals would be valuable to help determine under what conditions such reactions might occur, and this knowledge could be applied to comparing chamber and field SOA yields.

4.4 Atmospheric implications and needs for future work

As this paper proposes higher SOA yield for the NO3 + isoprene reaction than measured in chamber studies, we conclude with some discussion of the implications for regional aerosol burdens, and further needs for investigation in the NO3 + isoprene system.

Using an isoprene + NO3 yield parameterization that gave a 12 % SOA mass yield at 10 µg m−3, Pye et al. (2010) found that adding the NO3 + isoprene oxidation pathway increased isoprene SOA mass concentrations in the southeastern United States by about 30 %, increases of 0.4 to 0.6 µg m−3. The larger NO3 + isoprene SOA mass yields suggested in this paper, with average value of 30 %, could double this expected NO3 radical enhancement of SOA production. Edwards et al. (2017) concluded that the southeastern US is currently in transition between NOx-independent and NOx-controlled nighttime BVOC oxidation regime. If NO3-isoprene oxidation is a larger aerosol source than currently understood, and if future NOx reductions lead to a stronger sensitivity in nighttime BVOC oxidation rates, regional SOA loadings could decrease by a substantial fraction from the typical regional summertime OA loadings of 5±3 µg m−3 (Saha et al., 2017).

Analysis of the degree of oxidation and chemical composition of NO3 + isoprene SOA would help to elucidate mechanistic reasons for the different field and lab SOA yields. For example, the potential contribution of the uptake of morning-after OH + NISOPOOH produced epoxides, discussed above in Sect. 4.3, onto existing (acidic) aerosol could be quantified by measurement of these intermediates or their products in the aerosol phase. Assessment of degree of oxidation could help determine whether auto-oxidation mechanisms are active. Future similar field studies would benefit from the co-deployment of the complementary tool of a Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometer (CIMS) to detect NO3 + isoprene products such as organic nitrates (Slade et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2016). Due to the potentially large effect on predicted SOA loading in regions of high isoprene emissions, a better mechanistic understanding of these observed yields is crucial.

All data is available at: https://esrl.noaa.gov/csd/groups/csd7/measurements/2013senex/P3/DataDownload/ (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2018).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-11663-2018-supplement.

JLF, SSB, and AMM conducted data analysis and wrote the paper. PME contributed modeling and writing. DAD, PCJ, and JLJ contributed data analysis and writing. Other co-authors contributed data.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Juliane L. Fry gratefully acknowledges funding from the EPA STAR Program (no.

RD-83539901) and from the Fulbright US Scholars Program in the

Netherlands. Pedro Campuzano-Jost, Douglas A. Day and José L. Jimenez were partially supported by EPA STAR

83587701-0 and DOE (BER/ASR) DE-SC0016559. This paper has not been formally

reviewed by the EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of

the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the EPA. The EPA does not

endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication.

Edited by: Jason Surratt

Reviewed by: Thomas Mentel and two anonymous referees

Allan, J. D., Bower, K. N., Coe, H., Boudries, H., Jayne, J. T., Canagaratna, M. R., Millet, D. B., Goldstein, A. H., Quinn, P. K., Weber, R. J., and Worsnop, D. R.: Submicron aerosol composition at Trinidad Head, California, during ITCT 2K2: Its relationship with gas phase volatile organic carbon and assessment of instrument performance, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 109, D23S24, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JD004208, 2004a.

Atkinson, R., Baulch, D. L., Cox, R. A., Crowley, J. N., Hampson, R. F., Hynes, R. G., Jenkin, M. E., Rossi, M. J., and Troe, J.: Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume I – gas phase reactions of Ox, HOx, NOx and SOx species, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 4, 1461–1738, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-4-1461-2004, 2004.

Ayres, B. R., Allen, H. M., Draper, D. C., Brown, S. S., Wild, R. J., Jimenez, J. L., Day, D. A., Campuzano-Jost, P., Hu, W., de Gouw, J., Koss, A., Cohen, R. C., Duffey, K. C., Romer, P., Baumann, K., Edgerton, E., Takahama, S., Thornton, J. A., Lee, B. H., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Mohr, C., Wennberg, P. O., Nguyen, T. B., Teng, A., Goldstein, A. H., Olson, K., and Fry, J. L.: Organic nitrate aerosol formation via NO3 + biogenic volatile organic compounds in the southeastern United States, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 13377–13392, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-13377-2015, 2015.

Bahreini, R., Dunlea, E. J., Matthew, B. M., Simons, C., Docherty, K. S., DeCarlo, P. F., Jimenez, J. L., Brock, C. A., and Middlebrook, A. M.: Design and Operation of a Pressure-Controlled Inlet for Airborne Sampling with an Aerodynamic Aerosol Lens, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 42, 465–471, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820802178514, 2008.

Bahreini, R., Ervens, B., Middlebrook, A. M., Warneke, C., de Gouw, J. A., DeCarlo, P. F., Jimenez, J. L., Brock, C. A., Neuman, J. A., Ryerson, T. B., Stark, H., Atlas, E., Brioude, J., Fried, A., Holloway, J. S., Peischl, J., Richter, D., Walega, J., Weibring, P., Wollny, A. G., and Fehsenfeld, F. C.: Organic aerosol formation in urban and industrial plumes near Houston and Dallas, Texas, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 114, D00F16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD011493, 2009.

Boyd, C. M., Sanchez, J., Xu, L., Eugene, A. J., Nah, T., Tuet, W. Y., Guzman, M. I., and Ng, N. L.: Secondary organic aerosol formation from the β-pinene + NO3 system: effect of humidity and peroxy radical fate, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 15, 7497–7522, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-15-7497-2015, 2015.

Brock, C. A., Cozic, J., Bahreini, R., Froyd, K. D., Middlebrook, A. M., McComiskey, A., Brioude, J., Cooper, O. R., Stohl, A., Aikin, K. C., de Gouw, J. A., Fahey, D. W., Ferrare, R. A., Gao, R.-S., Gore, W., Holloway, J. S., Hübler, G., Jefferson, A., Lack, D. A., Lance, S., Moore, R. H., Murphy, D. M., Nenes, A., Novelli, P. C., Nowak, J. B., Ogren, J. A., Peischl, J., Pierce, R. B., Pilewskie, P., Quinn, P. K., Ryerson, T. B., Schmidt, K. S., Schwarz, J. P., Sodemann, H., Spackman, J. R., Stark, H., Thomson, D. S., Thornberry, T., Veres, P., Watts, L. A., Warneke, C., and Wollny, A. G.: Characteristics, sources, and transport of aerosols measured in spring 2008 during the aerosol, radiation, and cloud processes affecting Arctic Climate (ARCPAC) Project, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 2423–2453, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-2423-2011, 2011.

Brock, C. A., Wagner, N. L., Anderson, B. E., Attwood, A. R., Beyersdorf, A., Campuzano-Jost, P., Carlton, A. G., Day, D. A., Diskin, G. S., Gordon, T. D., Jimenez, J. L., Lack, D. A., Liao, J., Markovic, M. Z., Middlebrook, A. M., Ng, N. L., Perring, A. E., Richardson, M. S., Schwarz, J. P., Washenfelder, R. A., Welti, A., Xu, L., Ziemba, L. D., and Murphy, D. M.: Aerosol optical properties in the southeastern United States in summer – Part 1: Hygroscopic growth, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 4987–5007, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-16-4987-2016, 2016.

Brown, S. S., Neuman, J. A., Ryerson, T. B., Trainer, M., Dubé, W. P., Holloway, J. S., Warneke, C., de Gouw, J. A., Donnelly, S. G., Atlas, E., Matthew, B., Middlebrook, A. M., Peltier, R., Weber, R. J., Stohl, A., Meagher, J. F., Fehsenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Nocturnal odd-oxygen budget and its implications for ozone loss in the lower troposphere, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L08801, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL025900, 2006.

Brown, S. S., deGouw, J. A., Warneke, C., Ryerson, T. B., Dubé, W. P., Atlas, E., Weber, R. J., Peltier, R. E., Neuman, J. A., Roberts, J. M., Swanson, A., Flocke, F., McKeen, S. A., Brioude, J., Sommariva, R., Trainer, M., Fehsenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Nocturnal isoprene oxidation over the Northeast United States in summer and its impact on reactive nitrogen partitioning and secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 3027–3042, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-3027-2009, 2009.

Brown, S. S., Dubé, W. P., Karamchandani, P., Yarwood, G., Peischl, J., Ryerson, T. B., Neuman, J. A., Nowak, J. B., Holloway, J. S., Washenfelder, R. A., Brock, C. A., Frost, G. J., Trainer, M., Parrish, D. D., Fehsenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Effects of NOxcontrol and plume mixing on nighttime chemical processing of plumes from coal-fired power plants, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 117, D07304, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016954, 2012.

Brown, S. S. and Stutz, J.: Nighttime radical observations and chemistry, Chemical Soc. Rev., 41, 6405–6447, https://doi.org/10.1039/C2CS35181A, 2012.

Brown, S. S., Dubé, W. P., Bahreini, R., Middlebrook, A. M., Brock, C. A., Warneke, C., de Gouw, J. A., Washenfelder, R. A., Atlas, E., Peischl, J., Ryerson, T. B., Holloway, J. S., Schwarz, J. P., Spackman, R., Trainer, M., Parrish, D. D., Fehshenfeld, F. C., and Ravishankara, A. R.: Biogenic VOC oxidation and organic aerosol formation in an urban nocturnal boundary layer: aircraft vertical profiles in Houston, TX, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13, 11317–11337, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-11317-2013, 2013.

Bruns, E. A., Perraud, V., Zelenyuk, A., Ezell, M. J., Johnson, S. N., Yu, Y., Imre, D., Finlayson-Pitts, B. J., and Alexander, M. L.: Comparison of FTIR and Particle Mass Spectrometry for the Measurement of Particulate Organic Nitrates, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 1056–1061, 2010.

Cai, Y., C. Montague, D., Mooiweer-Bryan, W., and Deshler, T.: Performance characteristics of the ultra high sensitivity aerosol spectrometer for particles between 55 and 800 nm: Laboratory and field studies, J. Aerosol Sci., 39, 759–769, 2008.

Calvert, J. G., Atkinson, J. A., Kerr, J. A., Madronich, S., Moortgat, G. K., Wallington, T. J., and Yarwood, G.: Mechanisms of the atmospheric oxidation of the alkenes, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2000.

Carlton, A. G., Wiedinmyer, C., and Kroll, J. H.: A review of Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) formation from isoprene, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 9, 4987–5005, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-9-4987-2009, 2009.

Carlton, A. G., Pinder, R. W., Bhave, P. V., and Pouliot, G. A.: To What Extent Can Biogenic SOA be Controlled?, Environ. Sci. Technol., 44, 3376–3380, https://doi.org/10.1021/es903506b, 2010.

Crounse, J. D., Paulot, F., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Wennberg, P. O.: Peroxy radical isomerization in the oxidation of isoprene, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 13, 13607–13613, https://doi.org/10.1039/C1CP21330J, 2011.

D'Ambro, E. L., Møller, K. H., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D., Schobesberger, S., Liu, J., Shilling, J. E., Lee, B. H., Kjaergaard, H. G., and Thornton, J. A.: Isomerization of Second-Generation Isoprene Peroxy Radicals: Epoxide Formation and Implications for Secondary Organic Aerosol Yields, Environ. Sci. Technol., 51, 4978-4987, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00460, 2017.

Darer, A. I., Cole-Filipiak, N. C., O'Connor, A. E., and Elrod, M. J.: Formation and Stability of Atmospherically Relevant Isoprene-Derived Organosulfates and Organonitrates, Environ. Sci. Technol., 45, 45, 1895–1902, https://doi.org/10.1021/es103797z, 2011.

Dommen, J., Hellén, H., Saurer, M., Jaeggi, M., Siegwolf, R., Metzger, A., Duplissy, J., Fierz, M., and Baltensperger, U.: Determination of the Aerosol Yield of Isoprene in the Presence of an Organic Seed with Carbon Isotope Analysis, Environ. Sci. Technol., 43, 6697–6702, https://doi.org/10.1021/es9006959, 2009.

Drewnick, F., Hings, S. S., DeCarlo, P., Jayne, J. T., Gonin, M., Fuhrer, K., Weimer, S., Jimenez, J. L., Demerjian, K. L., Borrmann, S., and Worsnop, D. R.: A New Time-of-Flight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (TOF-AMS) – Instrument Description and First Field Deployment, Aerosol Sci. Tech., 39, 637–658, https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820500182040, 2005.

Edwards, P. M., Aikin, K. C., Dube, W. P., Fry, J. L., Gilman, J. B., de Gouw, J. A., Graus, M. G., Hanisco, T. F., Holloway, J., Hubler, G., Kaiser, J., Keutsch, F. N., Lerner, B. M., Neuman, J. A., Parrish, D. D., Peischl, J., Pollack, I. B., Ravishankara, A. R., Roberts, J. M., Ryerson, T. B., Trainer, M., Veres, P. R., Wolfe, G. M., Warneke, C., and Brown, S. S.: Transition from high- to low-NOx control of night-time oxidation in the southeastern US, Nat. Geosci., 10, 490–495, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2976, 2017.

Ehn, M., Thornton, J. A., Kleist, E., Sipila, M., Junninen, H., Pullinen, I., Springer, M., Rubach, F., Tillmann, R., Lee, B., Lopez-Hilfiker, F., Andres, S., Acir, I.-H., Rissanen, M., Jokinen, T., Schobesberger, S., Kangasluoma, J., Kontkanen, J., Nieminen, T., Kurten, T., Nielsen, L. B., Jorgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G., Canagaratna, M., Maso, M. D., Berndt, T., Petaja, T., Wahner, A., Kerminen, V.-M., Kulmala, M., Worsnop, D. R., Wildt, J., and Mentel, T. F.: A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol, aerosol, Nature, 506, 476–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13032, 2014.